Abstract

This study presents the effects of using pyrite aggregate in field concretes on the mechanical, surface performance, and algal growth tendency of concrete. The substitution of pyrite influences the process of hydration, as the gradual release of its iron- and sulfur-bearing components shifts the reaction mechanism, leading to differences in phase formation and some modification in the pore structure of the cement matrix. Three different concrete mixes (PB0, PB2.5%, and PB7.5%) were designed by replacing 0%, 2.5%, and 7.5% of the total weight of sand and crushed sand with ground pyrite as a fine aggregate. Prismatic specimens of 80 × 100 × 200 mm were produced from these mixtures and mechanical properties such as flexural, splitting tensile, and abrasion were investigated after 28 days of curing. Then, to determine the effect of pyrite on concrete surface properties, pyrite was substituted on the surface of three concrete specimens produced in 50 × 240 × 500 mm dimensions at rates of 0, 1, and 3 kg/m2. These specimens were divided into two groups: one group was exposed to clean water drops at a constant flow rate in a closed environment, and the other group was exposed to dirty water in an open environment, and observed for 2 months. At the end of the process, sections of 50 × 80 × 200 cm3 were taken from the specimens and friction, abrasion and flexural tests were carried out. The results of the study demonstrate that a 7.5% pyrite substitution improves both flexural and shear strength by 38%. At the same time, pyrite substitution prevented algal growth on the surface of field concrete under clean water and delayed its formation in those under contaminated water. Finally, it was observed that pyrite, when used in concrete mix and surface applications, optimizes mechanical performance and environmental durability.

1. Introduction

As urban populations grow, the need for communal spaces such as roadways, parks, and gardens rises, leading to a frequent prevalence of concrete applications in these social places [1,2,3]. Concrete is a preferred construction material in field pavements thanks to its advantages, such as creating a high-strength surface, covering large and wide areas quickly and economically, and providing long-term use with the right materials and workmanship [4,5,6]. Although it is a durable material, concrete surfaces are exposed to surface abrasion due to the use of vehicles and pedestrians in some cases, deterioration mechanisms due to the freeze–thaw effect of air, deterioration mechanisms such as algal growth on the surface, especially in humid environments, and damage caused by the crystallization of salt solutions in the porous structure of concrete [7,8,9,10]. Over time, polishing and algal growth on concrete surfaces due to the effects of physical, chemical, and biological factors can cause injuries and fatalities to people or vehicles using this area as the surface becomes very slippery [11,12]. Therefore, it is of great importance to understand the socio-economic impacts, causes of, and potential solutions to the damage caused to vehicles and people due to polishing and algal growth on concrete on such sites [13]. Algae, which form over time as a result of physical and chemical reactions within the structure, can expand and contract in response to wetness and drying, forming enormous volumes of slime that can cause the concrete surface to peel. These slime layers can create a slippery surface on site concrete and pose a safety risk [14,15,16,17]. This can have a large impact, especially when large quantities of field concrete are involved. This is because these structural components, which have mass concrete properties, can be further compromised due to biological layers forming on their surface or moisture-related deterioration. Therefore, to maintain performance in mass concrete applications, it is necessary to manage the algal growth and slime deposits on the surface. Mass concrete is defined as a monolithic structural element with dimensions that require the management of thermo-mechanical stresses and the associated volumetric deformations resulting from the exothermic reactions of cement hydration [18]. Field concrete, which is a mass concrete, has a wide range of applications and is used in pavements, industrial floors, marine environments, airports, and many other places where large volumes of concrete are required [19,20,21]. The long-term performance of such concretes may vary depending on many parameters such as exposure to environmental factors, loading conditions, and maintenance processes. In the design of mass concretes, techniques such as low-temperature cement types, appropriate mix proportions and cooling systems are used for crack control and minimization of internal stresses [22,23,24,25,26]. The techniques mentioned require a comprehensive evaluation of mineralogical elements that may affect the internal structure of concrete. This is because the hydration process, heat formation, and service performance can be affected by the physical and chemical properties of minerals added to the mixture or directly present in the aggregate. Therefore, the performance of mass concrete is particularly shaped by the minerals it contains, and these minerals must be thoroughly investigated.

Pyrite is one of the most common iron sulfide minerals found on the earth’s crust. Pyrite minerals can be found in the geologic structure of tortuous, metamorphic, or magmatic rocks, or in the content of other sulfate compounds. When the chemical composition of pyrite is examined, it is found to contain high concentrations of sulfur and iron, while gold, copper, and nickel may also be present in lower concentrations [27]. When pyrite waste is exposed to air or rainwater, it can easily oxidize and produce potentially hazardous compounds [28]. Therefore, converting pyrite or its waste into harmless substances or using it in certain mixtures can render it harmless [29,30]. For example, Mârșolea et al. (2023) [30] stated that increasing the pyrite usage rate in polyurethane foam mixtures positively affected the pressure resistance.

In this study, the effect of ground pyrite aggregate in retarding and preventing algae growth in field concretes, as well as its use as a surface hardener on concrete surfaces was investigated. In similar studies in the literature, Alum et al. [31] tested several biocide formulations containing class F fly ash, silica fume, zinc oxide, copper slag, ammonium chloride, sodium bromide and cetyl-methyl-ammonium bromide to reduce algae growth on concrete surfaces and measured the effectiveness of zinc oxide and ammonium bromide used in a mortar mix to reduce algae growth on concrete walls of water storage and handling facilities. Song et al. [32] conducted various experiments by adding nano-TiO2 and hydrophobic materials to the concrete mix to control algae growth on coral aggregate concrete surfaces and showed that these materials can inhibit the growth of algae on concrete surfaces. Martinez et al. [33] measured that cement mortars modified with photocatalytic and water-repellent materials significantly slowed the rate of algae growth. Jayakumar et al. [34] conducted EDAX analyses on samples taken from concrete cubes immersed in normal water and concrete surfaces with green algae attached under natural and laboratory-simulated conditions to investigate the metabolic activity of algae on concrete surfaces and found that calcium levels increased significantly in both environments.

Surface hardening is a frequently used method to increase the durability and wear resistance of concrete surfaces. In the literature, there are many studies in which various materials are applied to concrete surfaces for this purpose and performance improvements are achieved. For instance, Ustabas et al. [35] showed in his study that pyrite improved the surface abrasion resistance of concrete pavements when applied at a ratio of 0.10-0.20-0.30-0.40 according to its mass. In the study of Ustabas et al. [36] it was found that including chromite-, magnetite-, and quartz-based fine aggregates in the surface coating of concrete pavements increased abrasion resistance; the unpolished slip resistance values of pavements with quartz-based surface-hardener additives were notably higher than both unadulterated pavements and concrete pavements with chromite and magnetite additives, and quartz-based concrete pavements with 40% magnetite had the highest surface abrasion resistance. Padilha et al. [37] investigated the effect of surface hardeners on mechanical properties and surface hardness in concretes produced with different water/cement ratios, curing times, and cement types and found that the hardeners improved the surface quality in all mixtures and this improvement was more pronounced with cementitious hardener and a high water/cement ratio (0.6).

A review of the literature shows that there are many studies on improving the mechanical properties and surface performance of concrete. However, there is limited research on the use of pyrite aggregate as a surface hardener to make concrete surfaces resistant to biological deterioration such as algae growth. The purpose of this study is to address the knowledge gap regarding the utilization of fine aggregates with pyrite to mitigate the algal growth-induced degradation of concrete surfaces. In this study, ground pyrite mineral was used in concrete mix and surface coatings to investigate its effects on surface hardness, abrasion resistance, and resistance to biological deterioration. Specifically, the flexural, splitting tensile, and abrasion strengths of specimens containing different ratios of pyrite were investigated, and the behavior of concrete surfaces under environmental influences was evaluated by SEM (Scanning Electron Microscopy) and XRD (X-Ray Diffractometer) analysis. This study aims to contribute to the development of new approaches to make concrete surfaces a long-lasting, durable, and low-maintenance building material.

2. Materials and Methods

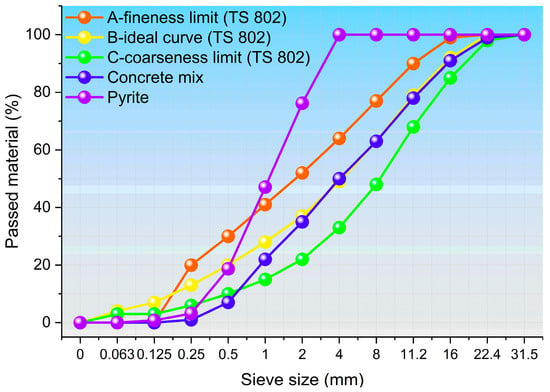

CEM I 42.5 R-type cement was used in the study and aggregates and admixtures were obtained from a concrete plant in Rize province. Pyrite rocks, which are the basic material of the study, were taken from a copper mine, processed in a jaw crusher, and sieved through a 4 mm mesh-opening sieve to obtain pyrite fine aggregate. The obtained pyrite material was pulverized in a ball mill in the laboratory environment. Sand (0/4), crushed sand (0/4), coarse aggregate (4/16), coarse aggregate (16/32), and fine aggregate with pyrite (0/4) had specific gravity values of 2.31, 2.48, 2.62, 2.69, and 4.74, respectively [38]. The quantities of the materials used in the concrete mixtures are presented in Table 1, and a granulometric distribution curve showing the conformity of the aggregate mixture with TS 802 (2016) standards is presented in Figure 1 [39].

Table 1.

Material quantities for 1 m3 pyrite concrete mix (kg).

Figure 1.

Granulometry curve of the designed concrete.

In this study, the effects of pyrite fine aggregate on the mechanical and surface properties of concrete were evaluated using a two-stage experimental approach. In the first stage of the study, three different concrete designs, namely PB0, PB2.5, and PB7.5 were prepared using ground pyrite fine aggregate instead of 0%, 2.5%, and 7.5% of the total weight of sand and crushed sand. A total of six specimens of 80 × 100 × 200 mm in size, including two specimens from each group, were produced from concretes with PB0, PB2.5, and PB7.5 designs, and flexural strength, tensile strength in splitting, shear and friction resistance, and abrasion resistance were evaluated on these specimens in accordance with the standards. The results of all mechanical tests were based on the average values of specimens cured for 28 days [40,41,42,43,44,45,46].

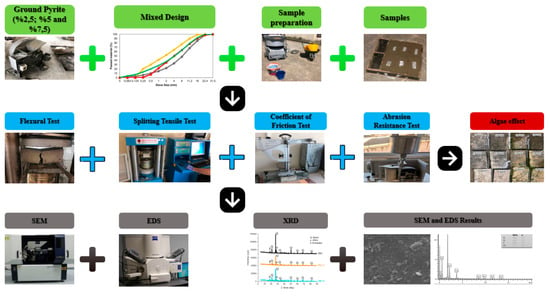

In the second stage of the study, to comprehensively investigate the effect of pyrite on concrete surface properties, three concrete specimens with dimensions of 50 × 240 × 500 mm were prepared and pyrite was applied to the surfaces of these specimens at rates of 0 kg/m2, 1 kg/m2, and 3 kg/m2 respectively. The specimens were tested in two different environments; in the first group, the specimens were exposed to clean water drops at constant flow rate for 2 months in a controlled, closed environment, while in the second group, the specimens were observed in a channel system containing dirty water under open-environment conditions for the same period of time. To expose these specimens to an equal amount of clean water at constant flow rate, water from a 200 L water tank was dripped onto the specimens. The experimental setup and samples are presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Process of the experimental study.

Algae growth on the concretes was determined by eye and under the microscope. The tap water used in these experiments was selected in accordance with the TS EN 1008 standards [47]. At the end of the experimental process, six specimens of 50 × 80 × 200 mm each were cut from both groups and friction, abrasion, and flexural strength tests were carried out; the relevant standards were followed during all tests and the results obtained were analyzed by comparing the average values.

The specimens were designed with concrete class C 40/50, water/cement ratio of 0.45, and slump class S1 (40 mm), and concrete production was carried out. Sand, crushed sand, coarse aggregate (4/16), and coarse aggregate (16/32) were added to the concrete mix at 23%, 37%, 28%, and 12%, respectively. The mixture was prepared with a pan mixer and 80 × 100 × 200 mm prismatic and 100 × 100 × 100 mm cube specimens were produced for various tests. In addition, algal growth observations were made in plywood molds of 50 × 240 × 500 mm. The specimens were cured in lime-saturated water for 28 days at a temperature of 20 ± 2 °C. Figure 3 illustrates the experimental setup.

Figure 3.

50 × 240 × 500 mm specimens: (a) mass concrete; (b) 1 kg/m2 pyrite-treated specimen; (c) 3 kg/m2 pyrite-treated specimen; (d) test setup.

In addition to these analyses, a microstructure analysis of the samples was performed using SEM (Scanning Electron Microscopy), XRD (X-Ray Diffraction), and FTIR (Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy).

XRD analysis was performed using a PW1830 model X-ray diffractometer with a wavelength of λCu-K-beta. The structural properties and phase distributions of the powder materials collected from the sample surfaces were determined by scanning in the 4–90° 2θ° angle range.

In SEM (Scanning Electron Microscope) analysis, the samples were examined at 1000× magnification and the changes in the surface properties of the pyrite-containing aggregates and their interactions with the concrete matrix were determined. EDS (Energy-Dispersive Spectroscopy) analysis was performed, integrated with SEM to determine the chemical composition of the admixed pyrite–concrete samples.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Mechanical and Physical Properties of Concrete Produced with Pyrite Fine Aggregate

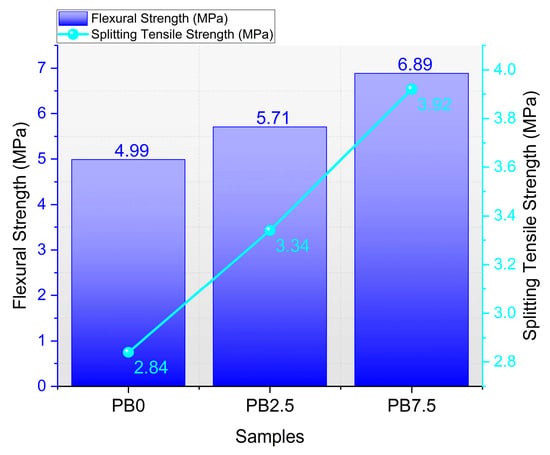

Table 2 presents the 28th-day flexural and splitting tensile strength values of PB0, PB2.5, and PB7.5 specimens with 80 × 100 × 200 mm dimensions. The flexural and splitting tensile strengths of the concretes increased slightly with an increase in pyrite fine aggregate content.

Table 2.

Flexural and splitting tensile strengths of PB0, PB2.5, and PB7.5 specimens.

The friction coefficients, vertical wear lengths, and mass loss values of concrete specimens containing PB0, PB2.5, and PB7.5 pyrite are presented in Table 3. It was observed that the addition of pyrite fine aggregate decreased the vertical wear length and increased the surface wear resistance of the concretes.

Table 3.

Friction, wear, and mass loss values for PB0, PB2.5, and PB7.5 specimens.

Table 4 shows the coefficient of friction, weight loss, and flexural strength values measured from the specimens poured into molds with dimensions of 50 × 240 × 500 mm and cut to 50 × 80 × 200 mm with a concrete cutting machine. In the specimens produced by sprinkling pyrite fine aggregate on the surface, a decrease in mass loss due to vertical abrasion was observed with increasing pyrite content.

Table 4.

Friction mass loss and flexural strength of 50 × 80 × 200 mm specimens obtained by cutting from 50 × 240 × 500 mm specimens.

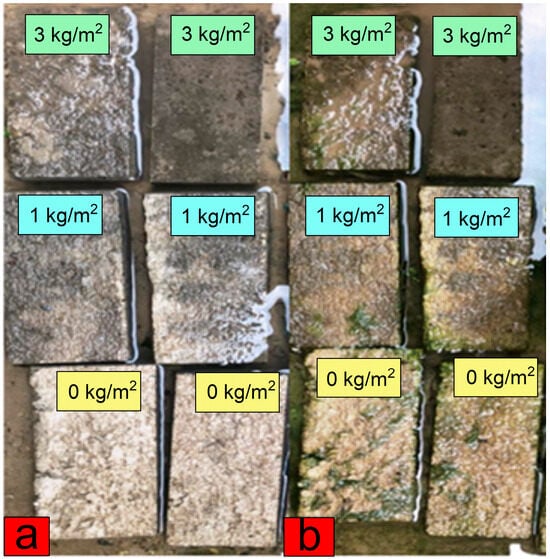

Figure 3 shows the results of the experiments performed with a fixed flow rate of clean water. In Figure 3a, it is observed that after two months in the concrete sample without pyrite, darkening occurs in the area where the concrete and water first come into contact. In Figure 3b, it is seen that in the concrete sample with 1 kg/m2 pyrite applied, there is a small amount of darkening in the areas without the pyrite coating, but there is no color change in the areas with pyrite. In Figure 3c, no color change was observed in the concrete treated with 3 kg/m2 pyrite. In Figure 4, the initial and two-months-later condition of the specimens without pyrite and with 1 kg/m2 and 3 kg/m2 pyrite surface are presented in dirty water for comparison.

Figure 4.

Images of the 50 × 80 × 200 samples obtained by cutting from 50 × 240 × 500 samples in the dirty water: (a) image on the first day; (b) image after 2 months.

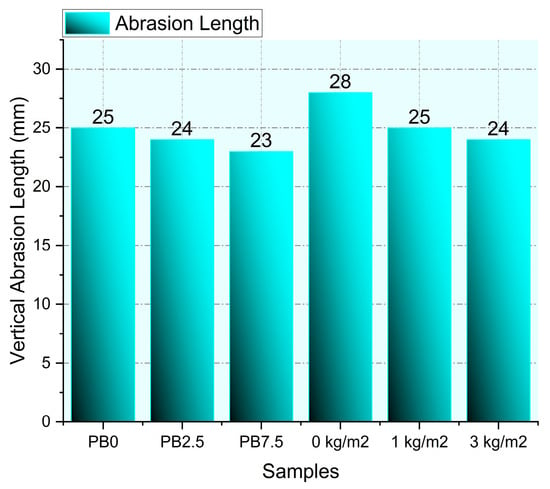

Figure 5 displays the abrasion lengths of the surfaces tested with a vertical abrasion device in two different concrete groups of 50 × 80 × 200 mm, produced by substituting 0%, 2.5%, and 7.5% of fine aggregate in PB0, PB2.5%, and PB7.5% concretes in prismatic specimens with dimensions of 80 × 100 × 200 mm and sprinkling pyrite fine aggregate on their surfaces at a rate of 1 kg/m2 and 3 kg/m2. It was found that the vertical abrasion length of the concrete surface decreased as the addition of pyrite aggregate in the concrete increased and the surface abrasion resistance increased significantly with the addition of 7.5% pyrite fine aggregate; the PB7.5 specimen showed an 8% reduction in abrasion length compared to the PB0 specimen.

Figure 5.

Vertical abrasion lengths of PB0, PB2.5, and PB7.5 specimens and 0 kg/m2, 1 kg/m2, and 3 kg/m2 (50 × 80 × 200 mm3) specimens.

Figure 6 presents the flexural and splitting tensile strengths of 80 × 100 × 200 mm PB0, PB2.5, and PB7.5 specimens. The increase in the amount of pyrite fine aggregate in the mixture increased the flexural and splitting tensile strengths. In the study conducted by Ustabas [35], average tensile strengths of 4.0 MPa for concrete with 10% pyrite, 4.1 MPa for concrete with 20% pyrite, and 4.8 MPa for concrete with 30% pyrite were measured. Espindola-Flores et al. (2024) [48] investigated the mechanical and electrical properties of structural concretes using 2.5%, 5%, and 10% polyethylene terephthalate as the fine aggregate. In terms of flexural strength, they reported 4.5 MPa strength at 28 days in the control group and 4.3 MPa in the 2.5% replacement samples. Comparing these values with the current study, the obtained flexural strengths are consistent with the literature, and the flexural strength performance of pyrite is 32.7% higher than that of polyethylene terephthalate aggregate. Huang et al. (2024) [5] examined the effects of substituting different percentages of natural aggregate with recycled aggregates obtained from concrete crushing on mechanical properties. When examining flexural strength, the control group achieved a strength of 7 MPa, while the other substitution groups achieved an average strength of approximately 6.80 MPa. Furthermore, some studies in the literature indicate that recycled concrete aggregates negatively affect flexural strength compared to the control group, while the use of pyrite as a fine aggregate improves the flexural strength of the control group by 38%.

Figure 6.

Flexural and splitting tensile strength graphs of 80 × 100 × 200 mm pyrite specimens.

As can be seen in the images of the specimens with different ratios of pyrite applied to the surface after being kept under clean and dirty water in Figure 7, as the amount of pyrite used on the surface of specimens exposed to dirty water increases, the amount of algal growth visibly decreases. These observations reveal that the use of pyrite on concrete surfaces has a reducing effect on algae growth.

Figure 7.

Samples with pyrite substitutions at rates of 0 kg/m2, 1 kg/m2, and 3 kg/m2 (50 × 80 × 200): (a) samples exposed to clean water for 2 months; (b) samples exposed to dirty water for 2 months.

3.2. SEM (Scanning Electron Microscopy) and EDS (Energy-Dispersive Spectroscopy) Analysis

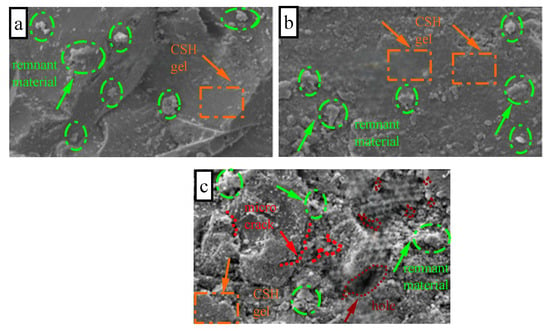

Figure 8 presents the 1000× magnified images obtained from SEM analyses. Figure 8a demonstrates a C-S-H structure and a low proportion of unreacted parts on the surface of the control sample. Figure 8b shows that a large number of particles did not fully associate with the C-S-H structure. Also, Figure 8c highlights the structure is porous and reveals the presence of microcracks on the surface of the PB7.5 sample [49].

Figure 8.

Images of Sem-analyzed samples enlarged up to 1000 times: (a) PB0; (b) PB 2.5; (c) PB 7.5.

However, gel formation was also observed in the PB7.5 sample. Furthermore, the portlandite phase found in the XRD analysis indicated that hydration reactions were continuing and that gel structures were forming as portlandite was consumed. Additionally, we can explain this situation in more detail with the secondary filling phenomenon. Increase the proportion of pyrite replacement created a secondary filling effect and, as the Portlandite in the matrix was consumed, it combined with the SiO2 present in the environment to form additional gel structures. This situation creates a stronger ITZ (Interaction Transition Zone), a lower void ratio, and an improved mechanical structure [50].

Flexural and splitting tensile strengths increase depending on the pyrite substitution rate (See Table 2). Sem graphs show that unreacted material, cracks, and voids intensify as the pyrite substitution rate increases. Some amount of void ratio was observed under the effect of flexural loading, which was reflected in the mechanical values. In other words, it is understood from the mechanical test results that although the void ratios are expected to decrease the strength at the beginning, the strength increases with the addition of unreacted materials to the reaction over time.

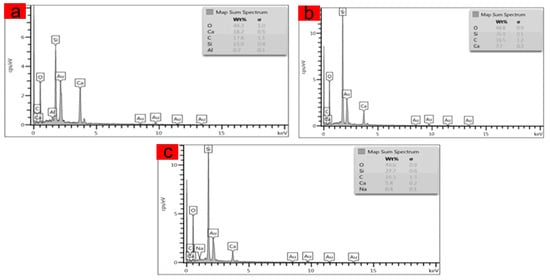

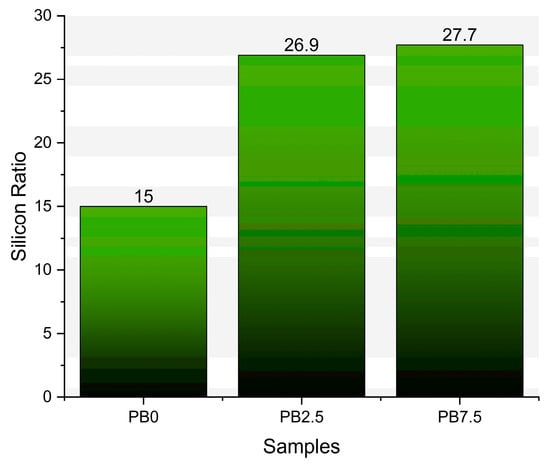

The EDS spectra presented in Figure 9 clearly demonstrate the elemental composition of the samples. According to the analysis results, the highest silicon (Si) content was found in sample PB7.50, with 27.7%, and the sodium (Na) content in this sample was measured as 0.4%.

Figure 9.

EDS graph of (a) PB0, (b) PB2.5, and (c) PB7.5 (80 × 100 × 200) samples.

Figure 10 demonstrates the EDS graphs of PB0, PB2.5, and PB7.5 samples with dimensions of 80 × 100 × 200 mm. According to the analysis results, the lowest silicon (Si) content was observed in the PB0 control sample, with 15%. According to the EDS analysis, an increase in Si content was associated with a decrease in algal coverage. Similar tendencies have been reported in some studies; however, the literature also indicates that such effects can vary considerably depending on the experimental constraints and conditions [51]. In fact, Yavasi measured the SiO2 ratio in the chemical composition of pyrite as 56.9% [52]. Similarly, in a study conducted by Tuntachon et al. [53], while examining the algal growth resistance of TiO2-containing fly ash on geopolymer, it was determined that the amount of SiO2 increased and algal growth decreased in direct proportion to the increase in the amount of TiO2.

Figure 10.

EDS graph of PB0, PB2.5, and PB7.5 (80 × 100 × 200) samples.

Jayakumar and Saravanane [34] conducted EDAX on samples obtained from concrete cubes immersed in normal water and a concrete surface with Ulva fasciata attached under natural and laboratory-simulated conditions to determine the metabolic activity of algae on concrete and found that the calcium level increased significantly during the natural simulation and laboratory simulation. In the present study, in line with the literature, as shown in Figure 9, the calcium content in the PB0 sample without the pyrite additive, where the highest algal growth was observed, was determined as 18.20%. This ratio decreased with the increase in pyrite content and was measured as 7.70% in sample PB2.50 and 5.80% in sample PB7.50. Several studies indicate that calcium depletion can influence algal growth; for example, in certain microalgae, such as Chlorella, the absence of Ca2+ has been shown to interrupt the cell cycle and consequently limit proliferation. However, these findings are derived from highly specific and controlled experimental systems, and therefore do not provide a sufficiently broad basis to establish a generalizable conclusion [54].

3.3. XRD Analysis

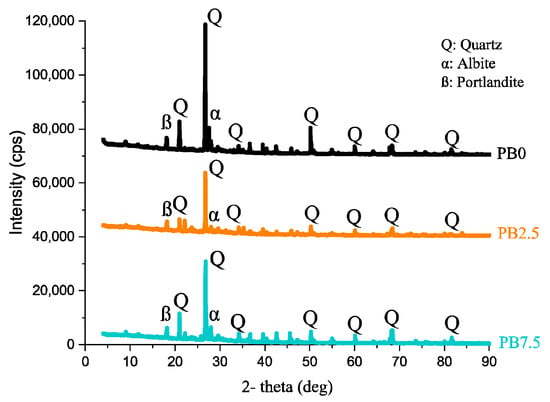

To investigate the changes in material characterization caused by pyrite admixture on concrete surfaces, powder materials taken from the sample surfaces were analyzed at Recep Tayyip Erdogan University Central Research Laboratory. A Philips PW1830 model device with wavelength λCu-K-beta was used for the X-Ray diffractometric powder method (XRD). Powder samples were scanned in the angle range of 4–90° 2ϴ° and 2-theta (deg) and densities were determined. The Qualx program was used to determine the phase changes indicating the mineralogical content of the samples [55]. The resulting XRD spectrum is presented in Figure 11. The main reaction phases of the concrete samples were Portlandite (18.20 2ϴ), Albite (27.94 2ϴ), and Quartz (21.04, 26.78, 34.28; 36.70, 50.26, 60.08, 68.24, and 81.64 2ϴ).

Figure 11.

XRD graph for PB0, PB2.50, and PB7.50 samples.

XRD analysis revealed portlandite peaks, and a decrease in SiO2 peaks in the XRD pattern was observed with pyrite substitution. Additionally, EDS analysis showed a significant increase in the Si element in the PB2.5 and PB7.5 samples. This could be attributed to the C-S-H gel formed by the secondary filling effect. Furthermore, XRD analysis revealed albite peaks. Albite peaks, with the chemical formula NaAlSi3O8, decrease in the XRD pattern as pyrite substitution increases. This situation could also be related to the results of the EDS analysis, which shows that the control sample contains Al but this is not present in the elemental composition with pyrite substitution [56,57].

4. Conclusions

In this study, the effects of pyrite on field concretes were experimentally investigated in terms of mechanical properties (flexural and splitting tensile strengths), surface resistance (wear length, friction, and mass loss), and algal growth. Based on all the mechanical and microstructural tests, the following findings were obtained:

- -

- When pyrite was used as fine aggregate in the concrete mix, an increase in flexural strength and tensile strength at splitting was observed with increasing pyrite content.

- -

- The use of pyrite on the concrete surface resulted in an increase in the coefficient of friction and a decrease in wear values.

- -

- Under natural water, pyrite inhibited changes in the surface, while when exposed to polluted water, it reduced and delayed the process of algae growth.

- -

- The findings revealed that pyrite aggregate positively contributes to the mechanical and surface properties of concrete.

The results of this study indicate that pyrite can positively improve physical parameters such as mechanical strength and surface abrasion resistance in field concretes. The increasing population and the increasing number of people living in cities have increased the need for infrastructure work on surface concretes in shared-use areas such as parks and recreational areas, and it is anticipated that this will further increase in the future. Therefore, improving the mechanical properties of the materials used in such areas to benefit the circular economy and increasing their resistance to the physical deterioration, such as moss growth, that may occur during long-term use is essential for a sustainable future. This study addresses a knowledge gap in the literature, provides data that can form the basis for future studies, and aims to provide insights into the use of limited raw materials for social benefit.

5. Limitations and Future Recommendations

This study focuses on the mechanical strength, surface abrasion and mass loss, and surface algae formation parameters when pyrite is used as a fine aggregate in field concrete. Mechanical strengths were determined using only pyrite as a fine aggregate, and the substitution rates were kept constant. The algal growth was determined from field observations and did not include detailed biological measurements. Pyrite has the potential to cause long-term negative effects, such as oxidation, gypsum formation, and harmful expansion due to sulfate attack, as well as corrosion. Therefore, future studies could investigate the long-term durability properties (e.g., expansion, sulfate attack, and corrosion) of concrete, mortar, and pastes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.M.O.; Methodology, Z.K., M.E.A., K.M.O. and C.I.U.; Formal analysis, M.E.A. and C.I.U.; Investigation, Z.K. and M.E.A.; Resources, I.U. and C.I.U.; Writing—original draft, Z.K. and K.M.O.; Writing—review and editing, Z.K., I.U. and C.I.U.; Visualization, M.E.A. and K.M.O.; Supervision, I.U. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Stępczak, M.; Kazimierczak, M.; Roszak, M.; Kurzawa, A.; Jamroziak, K. Microstructural and Impact Resistance Optimization of Concrete Composites with Waste-Based Aggregate Substitutions. Polymers 2025, 17, 2574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fakharian, P.; Bazrgary, R.; Ghorbani, A.; Tavakoli, D.; Nouri, Y. Compressive Strength Prediction of Green Concrete with Recycled Glass-Fiber-Reinforced Polymers Using a Machine Learning Approach. Polymers 2025, 17, 2731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghorbankhani, A.H.; Nili, M. Experimental and numerical assessment of thermal properties of self-compacting mass concrete at early ages. Eur. J. Environ. Civ. Eng. 2022, 26, 8194–8211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Shen, Y.; Yi, M.; Li, Q. Research on the expansion properties of concrete with waste granite aggregate during a high temperature process. J. Build. Eng. 2025, 113, 114199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Yu, R.; Sun, J.; Liu, Y.; Luo, S.; Li, S. Optimization of All-Desert Sand Concrete Aggregate Based on Dinger–Funk Equation. Buildings 2024, 14, 2332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.; Jiao, Y.; Xiao, M.; Yang, H.; Wang, C. Effect of Composition Characteristics on Mechanical Properties of UHPMC Based on Response Surface Methodology and Acoustic Emission Monitoring. Materials 2024, 17, 2714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, D.; Li, J.; Xiao, H.; Yang, W.; Liu, R. Research on the surface abrasion resistance performance of basalt fiber reinforced concrete. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 88, 109125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ting, M.Z.Y.; Wong, K.S.; Rahman, M.E.; Meheron, S.J. Deterioration of marine concrete exposed to wetting-drying action. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 278, 123383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thaulow, N.; Sahu, S. Mechanism of concrete deterioration due to salt crystallization. Mater. Charact. 2004, 53, 123–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, A.; Castro-Fresno, D.; Polanco, J.A.; Thomas, C. Abrasive wear evolution in concrete pavements. Road Mater. Pavement Des. 2012, 13, 534–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, U.R.; Ali, A.; Raheem, A.; Naseer, A.; Wright, K.; Bhatti, J. Injury hazard assessment in schools: Findings from a pilot study in Karachi, Pakistan. Injury 2023, 54, 110666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowicka-Krawczyk, P.; Komar, M.; Gutarowska, B. Towards understanding the link between the deterioration of building materials and the nature of aerophytic green algae. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 802, 149856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richhariya, V.; Tripathy, A.; Carvalho, O.; Nine, J.; Losic, D.; Silva, F.S. Unravelling the physics and mechanisms behind slips and falls on icy surfaces: A comprehensive review and nature-inspired solutions. Mater. Des. 2023, 234, 112335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eklund, J.A. Biological Growth on Masonry: Identification & Understanding; Historic Scotland: Edinburgh, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Waluś, K.J.; Łukasz, W.; Wieczorek, B.; Krawiec, P. Slip risk analysis on the surface of floors in public utility buildings. J. Build. Eng. 2022, 54, 104643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcelino, A.P.; Calixto, J.M.; Gumieri, A.G.; Ferreira, M.C.; Caldeira, C.L.; Silva, M.V.; Costa, A.L. Evaluation of pyrite and pyrrhotite in concretes. Rev. Ibracon Estrut. E Mater. 2016, 9, 484–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobbs, D.W.; Taylor, M.G. Nature of the thaumasite sulfate attack mechanism in field concrete. Cem. Concr. Res. 2000, 30, 529–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, I.; Lee, Y.; Amin, M.N.; Jang, B.S.; Kim, J.K. Application of a thermal stress device for the prediction of stresses due to hydration heat in mass concrete structure. Constr. Build. Mater. 2013, 45, 192–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Hao, G.; Du, H.; Fu, T.; Liu, D.; Huang, Y.; Ji, Y. Composite Fiber Wrapping Techniques for Enhanced Concrete Mechanics. Polymers 2024, 16, 2820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ustabas, I.; Deşik, F. Transition coefficients between compressive strengths of samples with different shape and size in mass concrete and use of weight maturity method in dam construction. Struct. Concr. 2021, 22, E696–E709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Yu, Z.; Wu, J.; Ding, Q.; Xu, W.; Huang, S. The application of heat-shrinkable fibers and internal curing aggregates in the field of crack resistance of high-strength marine structural mass concrete: A review and prospects. Polymers 2023, 15, 3884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, C.; Mao, Y.; Zhang, C.; Song, X. Effect and mechanism of phase change lightweight aggregate on temperature control and crack resistance in high-strength mass concrete. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 97, 110498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, J.; Jung, Y.S.; Cho, Y. Thermal crack control in mass concrete structure using an automated curing system. Autom. Constr. 2014, 45, 16–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohini, I.; Padmapriya, R. Properties of bacterial copper slag concrete. Buildings 2023, 13, 290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, T.S.; Kim, S.S.; Lim, C.K. Experimental study on hydration heat control of mass concrete by vertical pipe cooling method. J. Asian Archit. Build. Eng. 2015, 14, 657–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Ruan, S.; Qian, K.; Gu, X.; Qian, X. Will wind always boost early--age shrinkage of cement paste? J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2022, 105, 2832–2846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobrovolski, M.E.; Munhoz, G.S.; Pereira, E.; Medeiros-Junior, R.A. Effect of crystalline admixture and polypropylene microfiber on the internal sulfate attack in Portland cement composites due to pyrite oxidation. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 308, 125018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dos Santos, E.C.; de Mendonça Silva, J.C.; Duarte, H.A. Pyrite oxidation mechanism by oxygen in aqueous medium. J. Phys. Chem. C 2016, 120, 2760–2768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, L.P.; Müller, T.G.; Cargnin, M.; De Oliveira, C.M.; Peterson, M. Valorization of waste from coal mining pyrite beneficiation. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 105759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mârșolea, A.C.; Orbeci, C.; Rusen, E.; Stanescu, P.O.; Brincoveanu, O.; Irodia, R.; Pîrvu, C.; Dinescu, A.; Bobirica, C.; Mocanu, A. Design of polyurethane composites obtained from industrial plastic wastes, pyrite and red mud. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 405, 133319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alum, A.; Rashid, A.; Mobasher, B.; Abbaszadegan, M. Cement-based biocide coatings for controlling algal growth in water distribution canals. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2008, 30, 839–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, P.; Zhou, Y.; Guan, Q.; Wang, J.; Xia, J.; Huang, J.; Zhang, P. Prevention and control of chlorella for C30 concrete surface with coral aggregate, Journal of Wuhan University of Technology-Mater. Sci. Ed. 2022, 37, 628–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, T.; Bertron, A.; Escadeillas, G.; Ringot, E. Algal growth inhibition on cement mortar: Efficiency of water repellent and photocatalytic treatments under UV/VIS illumination. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 2014, 89, 115–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayakumar, S.; Saravanane, R. Biodeterioration of coastal concrete structures by marine green algae. Int. J. Civ. Eng. 2010, 8, 352–361. [Google Scholar]

- Ustabas, I.; Erdogdu, S.; Akyuz, C.; Kurt, Z.; Cakmak, T. Heavy aggregate and different admixtures effect on pavings: Pyrite, corundum and water-retaining polymer. Rev. La Construcción 2024, 23, 31–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ustabas, I.; Erdogdu, S.; Ucok, M.; Kurt, Z.; Cakmak, T. Heavy aggregate and different admixtures effect on parquets: Chrome, magnetite, and quartz-based surface hardener. Rev. La Construcción 2024, 23, 230–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padilha, F.; Lemos, G.V.B.; Silva, C.V.D. Effects of surface hardeners on the performance of concrete floors prepared with different mixture proportions. REM-Int. Eng. J. 2023, 76, 147–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EN, TS, 1097–6; Tests for Mechanical and Physical Properties of Aggregates-Part 6: Determination of Particle Density and Water Absorption. Turkish Standards Institute: Ankara, Turkey, 2022.

- EN, TS, 802; Design Concrete Mixes. Turkish Standards Institute: Ankara, Turkey, 2016.

- EN, TS, 12390–12392; Testing Hardened Concrete-Part 2: Making and Curing Specimens for Strength Tests. Turkish Standards Institute: Ankara, Turkey, 2019.

- EN, TS, 12390–12395; Testing Hardened Concrete-Part 5: Flexural Strength of Test Specimens. Turkish Standards Institute: Ankara, Turkey, 2019.

- EN, TS, 12390–12396; Testing Hardened Concrete-Part 6: Tensile Splitting Strength for Test Specimens. Turkish Standards Institute: Ankara, Turkey, 2010.

- EN, TS, 1341; Slabs of Natural Stone for External Paving–Requirements and Test Methods. Turkish Standards Institute: Ankara, Turkey, 2014.

- EN, TS, 1342; Setts of Natural Stone for External Paving-Requirements and Test Methods. Turkish Standards Institute: Ankara, Turkey, 2014.

- EN, TS, 1097–1098; Tests for Mechanical and Physical Properties of Aggregates-Part 8: Determination of the Polished Stone Value. Turkish Standards Institute: Ankara, Turkey, 2010.

- EN, TS, 1338; Concrete Paving Blocks-Requirements and Test Methods. Turkish Standards Institute: Ankara, Turkey, 2005.

- TS EN 1008; Mixing Water for Concrete-Spesifications for Sampling, Testing, and Assessing the Suitability of Water, Including Water Recovered from Processes in the Concrete Industry, as Mixing Water for Concrete. Turkish Standards Institution: Ankara, Turkey.

- Espindola-Flores, A.C.; Luna-Jimenez, M.A.; Onofre-Bustamante, E.; Morales-Cepeda, A.B. Study of the Mechanical and Electrochemical Performance of Structural Concrete Incorporating Recycled Polyethylene Terephthalate as a Partial Fine Aggregate Replacement. Recycling 2024, 9, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, H.; Ge, Z.; Sun, R.; Xu, X.; Lu, Y.; Ling, Y.; Zhang, H. Drying shrinkage, durability and microstructure of foamed concrete containing high volume lime mud-fly ash. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 327, 126990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, B.; Su, Y.; Hu, X.; Chen, Z.; Chen, Y.; Ding, X. Strength behavior and microscopic mechanisms of geopolymer-stabilized waste clays considering clay mineralogy. J. Clean. Prod. 2025, 530, 146877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, C.; Zhang, Y.; Guo, J.; Han, B.; Yang, X.; Yuan, J. Effects of silica nanoparticles on growth and photosynthetic pigment contents of Scenedesmus obliquus. J. Environ. Sci. 2010, 22, 155–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yavasi, H. The Determination of the Mechanical and Radiation Absorption Properties of Mortars Supplemented with Granulated Pyrite, Chromium and Magnetic. Master’s Thesis, Recep Tayyip Erdogan University, Rize, Turkey, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Tuntachon, S.; Kamwilaisak, K.; Somdee, T.; Mongkoltanaruk, W.; Sata, V.; Boonserm, K.; Chindaprasirt, P. Resistance to algae and fungi formation of high calcium fly ash geopolymer paste containing TiO2. J. Build. Eng. 2019, 25, 100817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, S.; Cho, S.; Jeong, D.; Kim, U.; Kim, J.; Lee, S.; Jung, Y. The Impact of Calcium Depletion on Proliferation of Chlorella sorokiniana Strain DSCG150. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2024, 34, 1425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altomare, A.; Corriero, N.; Cuocci, C.; Falcicchio, A.; Moliterni, A.; Rizzi, R. QUALX2.0: A qualitative phase analysis software using the freely available database POW_COD. J. Appl. Cryst. 2015, 48, 598–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Zheng, M.; Zhang, W.; Jing, H.; Ou, Z. Multicomponent cementitious materials optimization, characteristics investigation and reinforcement mechanism analysis of high-performance concrete with full aeolian sand. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 84, 108562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Chen, B.; Liu, N.; Jiang, Z. Utilization of waste phosphogypsum in high-strength geopolymer concrete: Performance optimization and mechanistic exploration. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 98, 111253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).