Abstract

As a vital cradle of Chinese civilization, the Yangtze River Basin possesses a wealth of ancient architectural heritage that serves as a material record of civilizational evolution. This study takes 688 nationally protected ancient architectural sites within the 11 provincial-level administrative regions along the main stream of the Yangtze River as its research objects. Utilizing GIS platforms and methods including the Nearest Neighbor Index, Kernel Density Estimation, Standard Deviational Ellipse, and Imbalance Index, we systematically analyze their spatio-temporal distribution characteristics. The results indicate the following: (1) Spatially, the ancient architecture exhibits a pattern of “multi-center agglomeration and axial diffusion,” with an overall clustered distribution, forming a dual-core structure with the Jiangsu–Anhui region in the lower reaches as the primary core and the Sichuan Basin in the upper reaches as the secondary core. (2) A quantitative temporal profile of the extant heritage was established, revealing a pronounced pyramid-shaped structure dominated by Ming–Qing (74.56%) and Song-Yuan (18.60%) remnants. Beyond merely reflecting material durability, this profile is shown to be a legacy of historical construction peaks driven by technological standardization and macro-economic shifts, which fundamentally preconditioned the spatial patterns analyzed. (3) The spatio-temporal evolutionary trajectory follows a path from “marginal aggregation” during the Sui, Tang, and Five Dynasties, to the establishment of a “dual-core structure” in the Song–Yuan periods, and finally to “axial diffusion” in the Ming–Qing periods. This study constructs a geographic analysis framework for cultural heritage at the basin scale, and its findings can inform the planning of heritage corridors and provide a reference for regional conservation strategies.

1. Introduction

Cultural heritage is a treasure bequeathed to humanity by history, playing a pivotal role in the transmission of historical knowledge [1]. As a vital component of cultural heritage, ancient architecture not only encapsulates rich historical information but also exemplifies the architectural techniques and artistic styles of various periods [2]. These structures possess immense historical and cultural significance, making their study essential for the preservation of global cultural heritage [3]. Through such research, people can better understand, safeguard, and ensure the inheritance of these invaluable cultural assets.

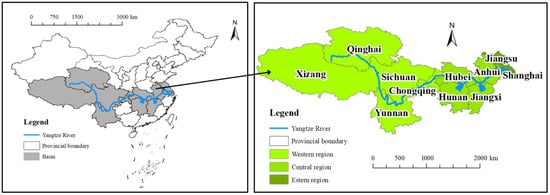

As a vital cradle of Chinese civilization, the Yangtze River Basin possesses an exceptionally rich repository of natural and cultural heritage. Its physical geography is complex and diverse, traversing China’s three major topographic steps. The Qinghai–Tibet Plateau in the upper reaches, the hilly basins in the middle reaches, and the alluvial plains in the lower reaches have collectively shaped a variety of local cultural patterns and settlement models. The basin serves not only as a crucial ecological barrier but also as the birthplace of distinctive regional cultures, such as Ba–Shu, Jing-Chu, and Wu-Yue. This study focuses on the 11 provincial-level administrative regions (Qinghai, Xizang, Sichuan, Yunnan, Chongqing, Hubei, Hunan, Jiangxi, Anhui, Jiangsu, and Shanghai) through which the main stream of the Yangtze River flows, constituting the primary axial belt of the entire basin (Figure 1). The river basin was chosen as the research scale because it represents an ideal geographical unit for understanding human–land interactions, civilizational evolution, and spatial diffusion.

Figure 1.

Yangtze River Basin.

The ancient architectural heritage under investigation in this study forms the core component of the cultural heritage within this basin and serves as a vivid manifestation of the “diversity in unity” of Chinese architectural culture. These structures are not only outstanding representatives of traditional Chinese construction techniques but also bear the material memory and cultural DNA of civilizational evolution [4]. Ranging from the magnificence of Tibetan watchtowers and Buddhist monasteries in the upper reaches, through the elegance and fluidity of ancestral temples in the Jing-Chu region of the middle reaches, to the exquisite refinement of Jiangnan gardens and Huizhou vernacular dwellings in the lower reaches, these buildings are the material crystallization and spatial testimony to the interplay between regional social institutions, religious beliefs, economic activities, and the natural environment. Current research on cultural heritage has shifted from singular structural conservation to multidimensional value exploration, with the analysis of their spatiotemporal distribution characteristics providing critical insights into cultural dissemination pathways, socioeconomic development patterns, and human-environment interactions [5,6,7].

However, these precious architectural heritage sites face severe contemporary challenges. Rapid urbanization and infrastructure construction continuously erode the historical context and setting of these structures. Climate change-induced extreme weather events (e.g., floods, humidity) pose a long-term threat to the preservation of wooden buildings. While tourism development brings economic benefits, it can also lead to over-commercialization and the loss of authenticity. Furthermore, effectively achieving adaptive reuse and the living conservation of the vast number of lower-tier historical buildings not designated as Major Historical and Cultural Sites Protected at the National Level remains a pressing practical difficulty.

Therefore, within this regional context, systematically revealing the spatiotemporal distribution patterns of ancient architecture is not only a fundamental task in historical geography but also an urgent prerequisite for scientifically addressing the aforementioned conservation and management challenges and for formulating sustainable regional strategies. This study aims to provide a macro-historical geographical perspective and data support for understanding and addressing these complex issues through spatiotemporal analysis.

Existing studies on ancient architecture primarily focus on digitalization, materials, and structures, offering technical support for preservation and restoration efforts [8,9,10]. However, understanding the spatial and temporal distribution characteristics is equally important, as it can reveal distribution patterns, historical evolution, and cultural dissemination pathways [11]. In this context, Geographic Information Systems (GIS) and spatial statistical methods have seen extensive application. GIS, a technology for capturing, storing, managing, analyzing, and displaying geographic data, was first conceptualized by R. Tomlinson in 1963 [12,13]. Initially confined to geography itself, GIS was rapidly adopted into cultural heritage research due to its technical capabilities, the proliferation of desktop software like ArcGIS, and advances in spatial statistics. It facilitates the analysis of spatial relationships, density hotspots, and distribution direction of heritage sites, provides precise geolocation, aids in assessing natural and anthropogenic threats, and assists in digital documentation and management [13,14,15,16,17]. Since the 21st century, the application of GIS in cultural heritage studies has grown significantly, with notable periods of explosive growth between 2015–2018 and 2019–2022 [12]. This has yielded macro-scale distribution studies on World Cultural Heritage [18,19,20], transnational cultural routes [21], and industrial heritage [22], effectively revealing the correlations between heritage distribution and natural and socio-economic factors.

Consequently, employing GIS and spatial statistics has become a well-established paradigm in international heritage conservation and historical geography, with numerous successful applications worldwide. In China, this approach has been effectively applied to ancient architecture. For instance, Jiang et al. [23] examined the spatio-temporal distribution and evolution of ancient architectural heritage in southeastern Zhejiang, providing references for its coordinated development and systematic revitalization. Xu et al. [24] demonstrated the combined influence of natural and cultural factors—such as topography, water systems, and traditional cosmographical concepts (e.g., “the Center of Heaven and Earth”)—on the distribution of historical buildings in the Songshan region. Gao et al. [25] explored the geographical distribution characteristics and determinants of heritage buildings in South China, informing their management. Wei et al. [26] analyzed the spatial and temporal aggregation of heritage buildings in Yangzhou and the factors shaping these patterns, discussing implications for tourism development.

At the river basin scale in China, such methods have been applied to regions like the Yellow River Basin and the Beijing-Hangzhou Grand Canal cultural belt. For instance, Chen et al. [27] analyzed the intangible cultural heritage in the Beijing-Hangzhou Grand Canal basin, while Wang et al. [28] and Wang et al. [29] investigated the spatial distribution characteristics and influencing factors of intangible cultural heritage in the Yangtze and Yellow River Basins, respectively. These studies have deepened our understanding of the spatial logic of cultural heritage at a national scale.

However, despite the river basin being an ideal unit for understanding human–land interactions and civilizational evolution, existing studies often focus on describing static distribution characteristics and analyzing influencing factors. A significant research gap remains concerning the spatio-temporal distribution characteristics of ancient architecture in the Yangtze River Basin, particularly regarding its dynamic coupling mechanisms with physical geography and historical processes. Furthermore, there is a lack of systematic revelation of the dynamic, mechanistic evolutionary pathways through which the heritage pattern within the basin responds to and records grand historical processes, such as the southward shift of the economic center, technological diffusion, and social change. This constitutes the key breakthrough that this study aims to achieve in terms of methodological and applied depth.

This study aims to fill this gap. The spatial analysis methods we employ—including the Nearest Neighbor Index [30,31,32], Kernel Density Estimation [33], Geographic Concentration Index [34,35], and Imbalance Index [36]—have been repeatedly validated for their effectiveness in cultural heritage spatial analysis. These methods can respectively reveal the distribution type, density hotspots, directional orientation, and distributional equity of heritage sites, providing reliable technical tools for interpreting the spatial narrative of heritage from macro to micro scales. Building upon this methodological foundation, this research constructs a comprehensive geographical analysis framework specifically for the ancient architectural heritage of the Yangtze River Basin.

Specifically, using ArcGIS 10.8 software, the present study analyzes the spatiotemporal distribution of ancient architecture in the Yangtze River Basin based on geographic data. The study focuses on the 11 provincial administrative units (Qinghai, Xizang, Sichuan, Yunnan, Chongqing, Hubei, Hunan, Jiangxi, Anhui, Jiangsu, and Shanghai) through which the main stream of the Yangtze River flows, as shown in Figure 1. By integrating multisource geospatial data and historical documents and employing methods such as kernel density estimation and standard deviation ellipse analysis, this research systematically reveals the spatiotemporal distribution patterns of ancient architectural heritage. The study also examines these characteristics by dividing China’s historical evolution into five distinct stages.

The findings indicate that ancient architecture in the Yangtze River Basin exhibits a “multi-center agglomeration and axial diffusion” spatial pattern: the lower reaches form the primary core, centered on Jiangsu and Anhui provinces; the middle reaches act as a transitional corridor; and the upper reaches feature a secondary core in the Sichuan Basin. Temporally, the number of architectural remnants shows a distinct “temporal pyramid” structure, with the vast majority dating to the Ming–Qing and Song–Yuan periods, reflecting the southward shift of China’s economic center and the evolution of building technologies.

In summary, this study analyzes the spatial and temporal distribution characteristics of ancient architecture in the Yangtze River Basin, contributing not only to the protection and transmission of cultural heritage but also providing a valuable reference for the study of ancient architecture in other regions. The academic value of this research lies in constructing a geographic analysis framework for cultural heritage at the basin scale, revealing the spatial logic of the “diversity in unity” evolution of Yangtze River civilization. Practically, the results can provide a scientific reference for heritage corridor planning and regional protection policies, particularly in addressing heritage vulnerability caused by climate change and urban expansion. Future research should further integrate methods from architectural archaeology and environmental history to explore the long-term relationship between architectural form evolution and watershed ecosystem services.

2. Data Sources and Research Methods

2.1. Data Sources

This study focuses on the architectural cultural heritage within the Yangtze River Basin in China. The relevant data was primarily sourced from the official website of China’s National Cultural Heritage Administration. As of 2025, the State Council of the People’s Republic of China has officially announced eight batches of Major Historical and Cultural Sites Protected at the National Level, totalling 5058 sites; among these, ancient architecture accounts for 2162 sites. This study selected ancient architectural sites located within the Yangtze River Basin as Points of Interest (POI), resulting in a sample size of 688. The coordinate data for these POIs were obtained using Google Earth. The administrative boundary data required for defining the river basin area were acquired from the National Earth System Science Data Sharing Infrastructure (http://www.geodata.cn/, accessed on 13 October 2025). The geospatial locations of all reported cultural preservation units were processed and matched using ArcGIS 10.8 software (developed by the Environmental Systems Research Institute of the United States, with its headquarters located in California).

It is important to acknowledge that the dataset of nationally protected sites, while authoritative, is inherently shaped by modern preservation policies and priorities. This means the spatial patterns identified in this study reflect the distribution of heritage that has been recognized and designated as having the highest level of significance in the contemporary era. While this provides an unparalleled window into the geography of China’s most valued ancient architectural heritage, it may not capture the complete historical footprint of all construction activities. This study therefore explicitly focuses on interpreting the spatio-temporal patterns of this nationally significant heritage stock.

2.2. Research Methods

2.2.1. Nearest Neighbor Index

To evaluate the distribution types of ancient architecture in the Yangtze River Basin, present study used the Nearest Neighbor Index (NNI), which can reflect the overall spatial pattern of these structures in the respective regions [30,31,32]. NNI is the ratio of the actual nearest neighbor average distance of the POIs to the theoretical average distance of the random distribution model [37]. The equations are as follows:

where is the actual mean nearest neighbor distance; is the expected average distance; is the distance between the corresponding POIs; is the number of POIs; is the total area of the study area, which is the sum of the area of 11 provincial administrative units flowing through the main stream of the Yangtze River.

Generally, is a clustered distribution, is a dispersed distribution, is a clustered–random distribution, is a random distribution, and is a random-dispersed distribution [38].

Z-test is used to verify the significance. When , it indicates that the significance test is not passed.

2.2.2. Kernel Density Estimation

The Kernel Density Estimation (KDE) is a non-parametric estimation method for analyzing the density of geographic features in interested areas [33]. Because of its ability to handle multimodal distributions effectively without requiring prior assumptions about data distribution, KDE was employed to assess the density [39,40,41,42]. Using KDE, identifies hotspots of ancient architecture could be identified. The equation is as follows:

where is the kernel function, is the bandwidth, is the number of POIs of ancient architectures, and is the distance from the estimated point to POI .

2.2.3. Geographic Concentration Index

The Geographic Concentration Index is an efficient quantitative tool for spatial equilibrium analysis, particularly suitable for macro-scale distribution studies. It evaluates spatial agglomeration by comparing observed distributions with theoretical uniform patterns [34,35]. Its strength lies in computational simplicity and compatibility with complementary analytical methods. The formula is expressed as

where denotes the geographic concentration index of ancient architectures in the Yangtze River Basin, represents the number of ancient architectures in the i-th province, is the total quantity of ancient architectures, and indicates the number of provincial-level administrative units. The index ranges 0–100, with higher values signifying stronger spatial concentration and lower values reflecting more balanced distributions. Assuming represents the theoretical benchmark value under a perfectly uniform distribution, a calculated indicates a concentrated distribution pattern of ancient architecture. Conversely, a suggests a more dispersed distribution.

2.2.4. Imbalance Index

The Imbalance Index quantifies distributional inequality by measuring deviations between actual spatial patterns and ideal uniformity, often visualized through Lorenz curves [36]. Its value ranges 0–1, where indicates perfectly equal distribution across provinces, while denotes complete concentration in a single province. The calculation formula is

where is the cumulative percentage of the top i units in the descending order of the ratio of ancient architectures quantities in each province to their total number and is the total number of provincial units.

2.2.5. Standard Deviational Ellipse (SDE)

The Standard Deviational Ellipse is a fundamental geospatial analysis method that characterizes spatiotemporal distribution patterns through ellipse centroid, axes, and orientation parameters [43,44,45]. Key parameters are derived as follows:

The centre of the ellipse could be calculated as follows:

The equation for the orientation of the ellipse is as follows:

The equations for the axis standard deviations are as follows:

where and are spatial coordinates of ancient architectures; and are arithmetic mean center; is the total number of ancient architectures; is the rotation angle; and are the difference between the arithmetic mean centre and the xy coordinates.

2.2.6. Historical Document Analysis and Spatial Pattern Corroboration

To deeply interpret the spatial distribution patterns of ancient architecture revealed by quantitative spatial metrics and their underlying causes, this study systematically employs Historical Document Analysis. This method aims to achieve a mutual verification between spatial patterns and historical processes. Its core principle is to treat the spatial distribution characteristics of ancient architecture (e.g., agglomeration, directionality, centroid shift) as material outcomes of historical processes, and to provide explanatory logic and driving mechanisms from the historical context by analyzing historical documents.

Through this methodology, this study moves beyond mere spatial description to achieve the excavation of historical causes and the analysis of humanistic driving mechanisms behind the spatiotemporal distribution patterns of ancient architecture in the Yangtze River Basin, thereby establishing a solid bridge between “data patterns” and “historical logic”.

3. Results and Discussions

3.1. Distribution Clustering Types

3.1.1. Overall Distribution Pattern

This section comprehensively utilizes three methods—Nearest Neighbor Index (NNI), Geographic Concentration Index, and Kernel Density Estimation (KDE)—to analyze the spatial distribution and clustering characteristics of ancient architecture in the Yangtze River Basin. According to the division of China’s economic zones by the National Bureau of Statistics, the 11 provincial-level administrative regions along the main stream of the Yangtze River are categorized into three regions for analysis: the Western region (Qinghai, Xizang, Sichuan, Yunnan, Chongqing), the Central region (Hubei, Hunan, Jiangxi, Anhui), and the Eastern region (Jiangsu, Shanghai). The specific results for NNI and the Geographic Concentration Index are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Parameters of distribution types.

All Z-test results are significant. The NNI value for the entire basin is 0.381, indicating that the ancient architecture overall exhibits a clustered distribution pattern. Further sub-regional analysis shows that the ancient architecture in the Western region also displays a clustered distribution, while the Central and Eastern regions exhibit a clustered–random transitional distribution. From the perspective of the Geographic Concentration Index, the values for the entire basin and all sub-regions are greater than the theoretical value under a uniform distribution, further confirming the trend of spatial concentration of ancient architecture.

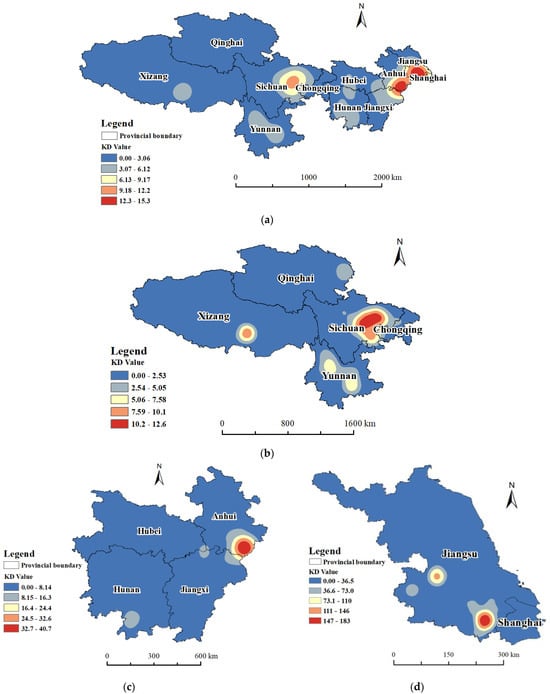

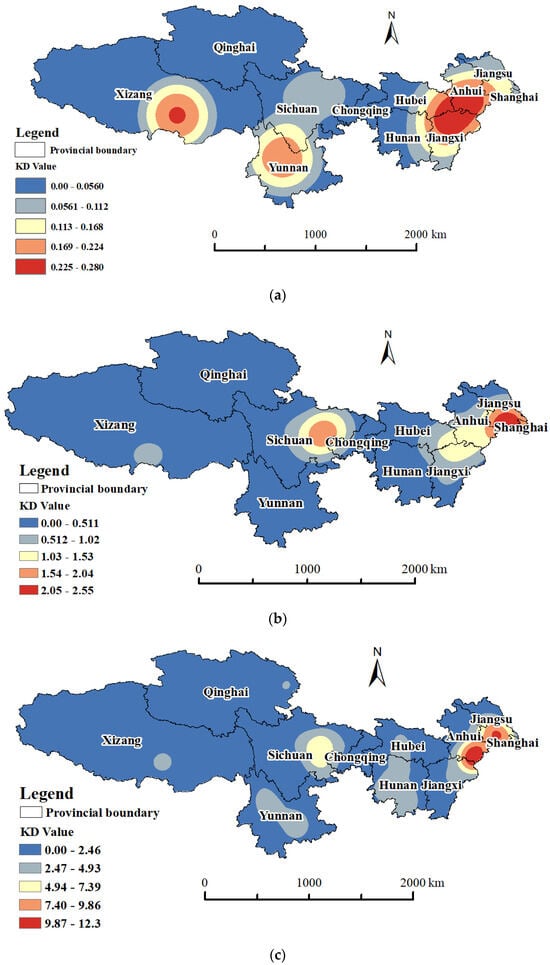

The kernel density analysis results (Figure 2) reveal that the ancient architecture in the Yangtze River Basin generally presents a pattern of “small-scale aggregation within large-scale dispersion” spatially. High-density areas are unevenly distributed, forming multiple local hotspots.

Figure 2.

KDE of Yangtze River Basin. (a) KDE of whole basin; (b) KDE of western region; (c) KDE of central region; (d) KDE of eastern region.

The discussion by region is as follows:

Entire Basin (Figure 2a): High-density areas are primarily concentrated in the eastern and east-central parts, particularly in Jiangsu and Anhui, with the Sichuan Basin also being a secondary high-density area. The NNI is 0.381, and the Z-value is −31.074, indicating a highly clustered heritage distribution; the value is 35.69, which is higher than (30.15), further supporting this conclusion.

Western Region (Figure 2b): The overall heritage density is low, but significant clustering exists in the Sichuan Basin. The NNI is 0.411, and the Z-value is −19.42, still indicating a clustered pattern; the value is 56.88, higher than (44.72), showing that although the total quantity is relatively small, the distribution remains quite concentrated.

Central Region (Figure 2c): The heritage density is moderate, with a significant high-density core in southern Anhui. The NNI is 0.555, and the Z-value is −14.23, belonging to a clustered–random transitional mode; the value is 51.14, slightly higher than (50.00), indicating a relatively even distribution but with slight clustering.

Eastern Region (Figure 2d): The heritage density is the highest, with some parts of Jiangsu forming a pronounced core. The NNI is 0.511, and the Z-value is −9.86, also falling into the clustered–random transitional mode; the value is 95.60, significantly higher than (70.71), reflecting that while the overall distribution is relatively uniform, local clustering characteristics remain quite evident.

The kernel density analysis and spatial statistical indicators jointly reveal the multi-scale differentiation patterns in the distribution of ancient architectural heritage in the Yangtze River Basin. At the basin-wide scale, the NNI and Geographic Concentration Index confirm a significantly clustered distribution of heritage. Spatial hotspots are concentrated in the Central-Lower Yangtze Plain and the Sichuan Basin, forming a “bipolar pattern” with the Jiangsu–Anhui region as the core and the Sichuan Basin as the secondary center. The formation of this distribution pattern results from the profound interaction between the natural geographical foundation and the millennia-long historical processes of Chinese civilization.

3.1.2. Historical Drivers of the Bipolar Structure

From a basin-wide perspective, the formation of the “bipolar pattern” stems from the historical southward shift of China’s economic and cultural center and differences in regional development models.

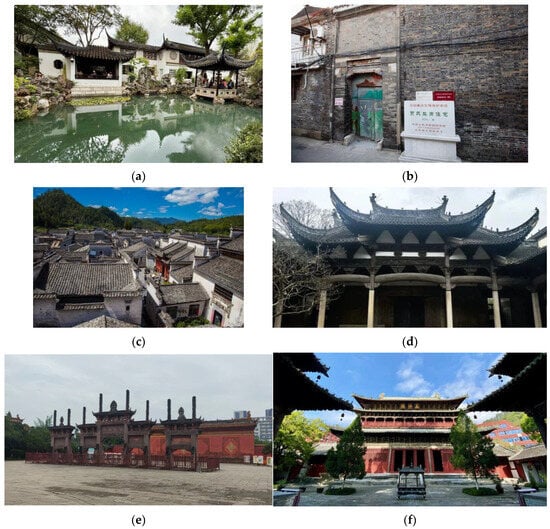

The prosperity of the lower reaches core was fundamentally the product of the interaction between “macro-state narratives” and “endogenous regional dynamics”. Firstly, state-level factors “Southward Migration of the Gentry” and the tribute grain transport economy established the developmental framework. Beginning in the Wei, Jin, and Northern and Southern Dynasties periods, to escape warfare in the north, aristocratic families from the Central Plains migrated south on a large scale (the Book of Jin · Biography of Wang Dao records: “Six or seven out of ten men and women from the Central States fled the chaos for the Jiangzuo region” [46]). This migration not only brought advanced construction techniques but also deeply embedded the ritual culture and clan concepts of the Central Plains into this region. After the Sui and Tang dynasties, with the improvement of the Grand Canal system, the lower Yangtze region, serving as the core area for the collection and northward transport of tribute grain, saw its economic status elevated unprecedentedly, as suggested by the phrase “Nowadays, nine-tenths of the tax revenue collected across the nation comes from the Jiangnan region.” from the Preface to Seeing Off Lu to Shezhou [47]. The high-density heritage in Jiangsu is represented by salt merchant residences (e.g., the Lu Family and Jia Family Salt Merchant Residences), gardens (e.g., the Humble Administrator’s Garden and the Lingering Garden), temple pagodas (e.g., the Yunyan Temple Pagoda and the Haiqing Temple Pagoda), and tribute grain transport facilities (e.g., the Yucheng Postal Stop). Anhui’s heritage centers on Huizhou-style vernacular dwellings (e.g., the Ancient Architectural Complex of Xidi Village and the Ancient Architectural Complex of Hongcun), ancestral halls (e.g., the Luo Dongshu Ancestral Hall and the Hu Family Ancestral Hall), and memorial archway clusters (e.g., the Tangyue Memorial Archway Group), reflecting the profound shaping of regional society by clan organizations and Huizhou merchant capital. Secondly, while state-level factors like the tribute grain transport system and the southward migration of the gentry established the developmental framework, it was the powerful regional forces that truly filled this framework and refined its spatial form. This is epitomized by the rise of merchant capital (e.g., from Huizhou merchants) and its deep synergy with gentry culture. Huizhou merchants not only invested their wealth in constructing residences and gardens but also profoundly shaped the local cultural landscape and spatial structure through the building of ancestral halls, memorial archways, and academies. This model of ‘gentry-merchant collaboration’ was the key mechanism that translated the advantage of being a national economic lifeline into dense, high-value architectural heritage clusters.”

The persistent strength of the Sichuan Basin as a secondary core cannot be explained solely by the southward shift of the macroeconomic center; on the contrary, its vitality stemmed from its endogenous developmental resilience as a relatively independent geographical unit. The agricultural superiority of the “Land of Abundance”, supported by systems like the Dujiangyan irrigation, fostered an endogenous, self-sustaining cycle of socioeconomic and cultural development. The exceptionally favorable natural conditions within the basin (e.g., after Li Bing built the Dujiangyan irrigation system, it was said that “Floods and droughts are subject to human control, and people do not know famine,” as recorded in the Records of the Grand Historian · Treatise on Rivers and Canals [48]) supported sustained population aggregation and regional cultural prosperity, forming a heritage cluster characterized by Confucian Temples (e.g., the Fushun Confucian Temple and the Deyang Confucian Temple) and religious buildings (e.g., the Pingwu Bao’en Temple and the Baoguang Temple). Although the overall density of its heritage is lower than that of the lower reaches, it still exhibits a high degree of clustering around the Chengdu Plain. This inherent stability allowed it to buffer against the full impact of shifts in the national economic center. Therefore, the formation of the Sichuan Basin core documents not a simple response to national economic trends, but a unique path whereby a regional civilization maintained its prosperity and accumulated material heritage based on its own foundations within the grand historical process.

A part of the above-mentioned architectural heritage is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Respective architectural heritage of the dual-core structure. (a) Lingering Garden in Jiangsu; (b) Jia Family Salt Merchant Residences in Jiangsu; (c) Ancient Architectural Complex of Xidi Village in Anhui; (d) Hu Family Ancestral Hall; (e) Deyang Confucian Temple in Sichuan; (f) Pingwu Bao’en Temple in Sichuan. P.S. The Chinese characters in image (b) read “贾氏盐商住宅”, a surviving architectural structure from the Qing Dynasty. In March 2013, it was listed as part of the seventh batch of Major National Historical and Cultural Sites by the State Council of the People’s Republic of China. This stone monument was erected by the People’s Government of Jiangsu Province. The Chinese characters in image (f) read “万佛阁” (Ten Thousand Buddha Pavilion), which is the name of a representative structure within Pingwu Bao’en Temple.

3.1.3. Mechanisms of Regional Differentiation

From a local perspective, the internal differentiation within the basin reflects the adaptive responses of regional societies to specific historical contexts.

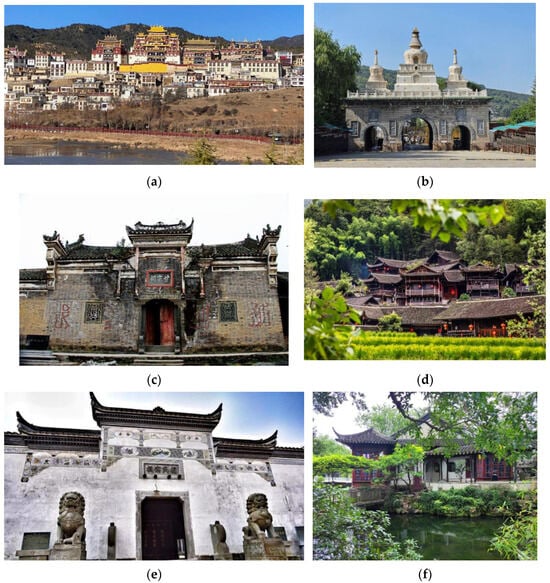

Within the core lower reaches area, the heritage distribution shows a high degree of orientation along canals and major water systems, which directly corroborates the developmental logic of “producing through craftsmanship and distributing through commerce” found in the Records of the Grand Historian · Biographies of Merchants [49]. The combination of commercial capital and gentry culture was the dominant force shaping this spatial pattern. In the central region, the “clustered–random” transitional mode of heritage and its corridor-like distribution are rooted in its essence as a “transition zone” for cultural convergence. This region lies at the transition between China’s second and third topographic steps; the Yangtze River and its tributaries form natural corridors, while mountain ranges act as barriers and guides for cultural diffusion. This led to the collision and integration of cultures such as Chu culture, Central Plains culture, Huxiang culture, and the Jiangxi lineage culture here. Consequently, the architectural heritage exhibits characteristics of multi-cultural layering and linear distribution along waterways, surpassing explanatory frameworks based solely on migration history. In contrast, the heritage in the western part of the upper reaches exhibits strong “environmental adaptability” and “cultural landmark” clustering. The spatial layout of structures like towering watchtowers and Tibetan fortified villages primarily served defensive and survival needs (an early form is documented in the Book of the Later Han · Biography of the Ethnic Minority Groups in Southern and Southwestern China as “dwelling by the mountains, building houses with piled stones” [50]). Meanwhile, the distribution of grand Tibetan Buddhist monasteries (e.g., the Potala Palace, Kumbum Monastery, and Ganden Sumtseling Monastery) completely follows an internal logic of constructing sacred geographical space, profoundly reflecting how local knowledge responded to both the harsh natural environment and the spiritual world. This formed a unique heritage cluster, distinct from the Central Plains civilization, tightly embedded within the local mountains and rivers.

In summary, the spatial pattern of ancient architecture in the Yangtze River Basin is the material crystallization of the superposition and collision of national historical dynamics (e.g., the tribute grain transport system, migration movements) and regional social adaptations (e.g., cultural integration, environmental response, construction of sacred order) across different geographical units. The core lower reaches area represents the spatial projection of the national economic lifeline and mainstream cultural norms, while the secondary center in the upper reaches and the central corridor record the survival strategies and cultural creations of regional societies within the grand historical process. Together, they constitute the material testimony of the “diversity within unity” pattern of Chinese civilization within the Yangtze River Basin.

Some of the architectural heritage in different geographical units within the basin are shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Respective architectural heritage across the basin. (a) Ganden Sumtseling Monastery in Yunnan; (b) Kumbum Monastery in Qinghai; (c) Gan Family Ancestral Hall in Hubei; (d) Ancient architectural complex of Pengjiazhai in Hunan; (e) Longxi Zhu Family Ancestral Hall in Jiangxi; (f) Humble Administrator’s Garden in Jiangsu. P.S. The Chinese characters in image (c) read “甘宗祠”, the Chinese name for the Gan Family Ancestral Hall in Hubei. The Chinese characters in image (e) read “祝氏宗祠”, the Chinese name for the Longxi Zhu Family Ancestral Hall in Jiangxi.

3.2. Distribution Evenness

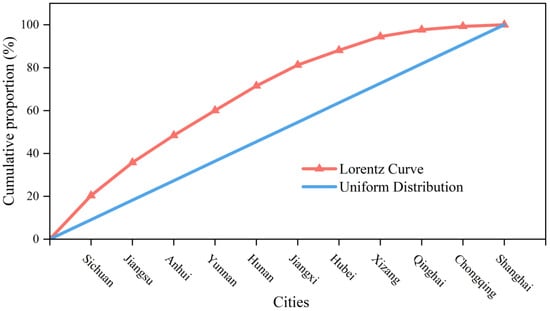

This study employed the Imbalance Index and the Lorenz curve to quantitatively assess the distribution evenness of ancient architecture in the Yangtze River Basin. The calculated Imbalance Index for the entire basin is 0.393. This value, situated between 0 (perfectly even) and 1 (perfectly concentrated), indicates that the heritage distribution within the basin is neither highly concentrated nor nearly uniform, but rather exhibits a significant, multi-tiered unevenness. This conclusion is strongly supported by the Lorenz curve (Figure 5), which deviates from the line of perfect equality and shows a distinct convex shape, visually revealing the spatial agglomeration of the heritage.

Figure 5.

Lorentz curve of the distribution of ancient architectural heritage in the Yangtze River Basin.

Specifically, the three provinces of Sichuan, Jiangsu, and Anhui collectively account for 48.30% of the total number of ancient buildings in the entire basin, forming the core area of heritage distribution. In stark contrast, Qinghai, Chongqing, and Shanghai together contribute only 5.52%, placing them in the peripheral zone. This substantial disparity is the inevitable result of the combined effects of multiple factors, including natural geographical conditions, historical development processes, cultural influence, and the size of modern administrative divisions.

The high proportion in the core area reflects the “bipolar pattern” identified in the previous analysis. Sichuan benefits from the agricultural foundation of the Chengdu Plain, known as the “Land of Abundance,” and its relatively enclosed and secure geographical environment, which made it a sustained economic and cultural center historically, resulting in a vast stock of heritage. Jiangsu and Anhui, as the core recipients of the southward shift of China’s economic and cultural center, flourished with the tribute grain transport system, salt industry, and imperial examination culture. A powerful gentry class and substantial commercial capital led to the creation of dense clusters of architectural heritage, such as gardens, ancestral halls, and market towns. Their high share aligns with historical logic.

The low proportion in the peripheral areas requires a comprehensive understanding based on differences in civilization types and the scale of administrative divisions. Qinghai, located on the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau, has its development of agricultural civilization constrained by the high-altitude, cold environment. Its heritage consists predominantly of Tibetan Buddhist monasteries, reflecting a distribution logic of “point-like grandeur” rather than “areal density,” where the value lies more in the scale and religious significance of individual sites than in absolute quantity. The low shares of Chongqing and Shanghai are primarily influenced by their relatively small modern administrative areas. Historically and culturally, Chongqing is an integral part of the Sichuan Basin, and its heritage belongs organically to the Bashu cultural system. Shanghai is a city that developed predominantly in the modern era; in ancient times, it was long under the jurisdiction of Songjiang Prefecture, and its heritage is essentially a peripheral extension of the Wuyue cultural sphere. The small provincial-level area of these two municipalities means that macro-level statistics struggle to reflect their actual cultural affiliations and heritage density accurately.

In summary, the distribution of ancient architecture in the Yangtze River Basin exhibits significant spatial unevenness. This is the result of the overlapping effects of multiple factors: natural geographical conditions, historical development processes, differences in civilization types, and modern administrative divisions. The findings deepen the understanding of the formation mechanisms of cultural heritage spatial patterns and provide an important basis for formulating differentiated regional heritage conservation strategies.

3.3. Historical Formation and Evolution of Spatial Patterns

3.3.1. Temporal Distribution Characteristics

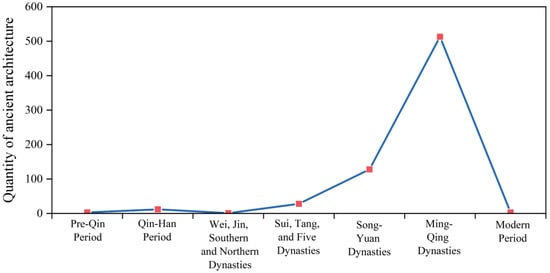

The temporal distribution of ancient architectural heritage in the Yangtze River Basin exhibits significant non-equilibrium, presenting a typical “A-shaped” pattern (Figure 6) characterized by a distinct phenomenon of “more from recent periods, fewer from ancient times.” Statistical data show that structures from the Song–Yuan (960–1368 AD) and Ming–Qing (1368–1912 AD) periods constitute the main body of the temporal sequence, accounting for 18.60% and 74.56% of the extant heritage, respectively. In contrast, those from the Sui, Tang, and Five Dynasties period (581–960 AD) account for only 4.07%, with all other periods combined totaling just 2.76%. This pronounced chronological skew results from the combined effects of architectural technological evolution, economic development levels, and the inherent characteristics of heritage preservation.

Figure 6.

Quantity of ancient architecture in different historical periods.

Firstly, the physical properties of wood and the climatic environment of the Yangtze River Basin jointly constrained the survival timeframe of early structures. Traditional Chinese architecture is centered on a timber frame system. Wood, as an organic material, has its durability naturally limited by risks such as decay, insect infestation, and fire. This was particularly true in the Yangtze River Basin, where the warm and humid climate, while favorable for agriculture, accelerated the decay of wooden components. This made timber structures predating the Yuan Dynasty highly susceptible to natural demise unless they underwent repeated renovations throughout history. Compounded by destruction from warfare and upheavals (e.g., the Song–Yuan transition, the late Yuan turmoil), surviving timber relics from the Tang Dynasty and earlier are exceptionally rare.

Secondly, the promulgation of the Northern Song dynasty’s Treatise on Architectural Methods (Yingzao Fashi) [51] marked a standardization revolution in building techniques, significantly enhancing the quality and durability of structures from the Song and Yuan periods. This officially sanctioned compendium, compiled in 1103 AD (the 2nd year of the Chongning era) by Li Jie, not only systematically summarized past experiences but, crucially, established a modular design system centered on the “cai-fen” system. The first chapter begins by defining the standard dimensions of the cai (materials) module: “All rules for constructing buildings take the materials as the fundamental basis.” This standardization optimized construction methods at key joints and led to more scientific use of materials, institutionally guaranteeing the structural integrity and stability of buildings and thereby significantly extending their physical lifespan.

It is noteworthy that a significant number of outstanding modern buildings, due to their relatively recent construction, have not yet been included in the statistical scope. Architectural heritage from the late Qing to the Republican period accounts for only 1.2% of the total.

3.3.2. Period-Based Spatial Evolution

To systematically reveal the spatial distribution patterns of ancient architectural heritage in the Yangtze River Basin, this study employed the Nearest Neighbor Index (NNI) and Kernel Density Estimation (KDE) methods to conduct a quantitative analysis of its spatial patterns across different historical periods. The calculation results are shown in Figure 7 and Table 2. The results indicate that the distribution of ancient architecture within the basin possesses significant spatio-temporal heterogeneity and dynamic evolutionary characteristics.

Figure 7.

KDE of different periods in Yangtze River Basin. (a) KDE of Sui, Tang, and Five Dynasties; (b) KDE of Song–Yuan Dynasties; (c) KDE of Ming–Qing Dynasties.

Table 2.

Parameters of distribution types in different historical periods.

The Sui, Tang, and Five Dynasties period exhibited a unique “peripheral aggregation” mode. The NNI was 0.584 (Z = −4.213), G = 40.31 (slightly larger than G0 = 37.80), indicating a clustered–random mixed distribution of heritage from this period. KDE results showed that density peaks were unusually located in peripheral areas such as the western fringe of the basin (Xizang, Yunnan) as well as southern Anhui and northern Jiangxi, reflecting the spatial characteristic that the core areas of the basin were still underdeveloped at that time, while religious propagation and local political power activities were more active in frontier regions. During the Song and Yuan periods, the spatial pattern of heritage underwent significant reorganization. The NNI decreased to 0.498 (Z = −10.873), G = 38.58 (larger than G0 = 30.15), showing a clear clustered distribution pattern. KDE analysis clearly demonstrated the rapid emergence of the Sichuan Basin and the lower Yangtze region as new high-density heritage areas, with the Yangtze River Delta in particular forming a distinct density core, marking the preliminary establishment of the basin’s “dual-core structure.” By the Ming and Qing periods, the spatial agglomeration effect further intensified, with the NNI dropping further to 0.408 (Z = −25.660), G = 35.87 (larger than G0 = 30.15). The highest density core formed around Jiangsu and southern Anhui, with the Sichuan Basin as a stable secondary core, presenting a typical “dual-core agglomeration” structure. Unlike the Song–Yuan period, KDE results indicated a trend of spatial diffusion from the core areas to the periphery during the Ming–Qing period. The distribution of ancient architecture became more extensive and continuous across the entire basin, with the coverage area significantly expanded.

The evolutionary trajectory of the spatial pattern of ancient architecture in the Yangtze River Basin—from “peripheral aggregation” to “dual-core structure” and then to “axial diffusion”—profoundly reflects the macroscopic processes of economic restructuring, population migration, and technology dissemination in Chinese history. The “peripheral aggregation” during the Sui and Tang periods was closely related to the frontier management and religious propagation of the Central Plains dynasties. As recorded in the Records of the Grand Historian · Biographies of Merchants, “The Jiangnan region is low-lying and humid, and people often died prematurely [49]” indicating that most parts of the Yangtze River Basin were not fully developed. Meanwhile, the rise of the Tibetan Empire on the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau (e.g., the construction of the Jokhang Temple and the Samye Monastery) and the rule of the Nanzhao Kingdom in Yunnan (e.g., the Three Pagodas of Chongsheng Temple) led to religious buildings and military fortresses being mostly distributed in the peripheral zones of political power, creating a spatial anomaly where “When rituals are lost in the court, seek them in the countryside [52].” The formation of the “dual-core structure” during the Song and Yuan periods directly stemmed from the southward shift of China’s economic center. After the fall of the Northern Song, the “Southward Migration of the Gentry” caused the population and economic strength of the south to surpass the north for the first time. The saying from the Gazetteer of Wu Prefecture (Wu Jun Zhi), “When Suzhou and Huzhou have a good harvest, the whole land has plenty [53].” signified that the lower Yangtze had become the nation’s economic lifeline. Simultaneously, the Song Dynasty conducted multiple large-scale renovations of the Dujiangyan irrigation system (the History of Song · Biography of Zhao Buyou: “Each year, the Yongkang Commandery maintained the Dujiang Weir. They used bamboo cages filled with stones to dam the river and block the water, thereby irrigating farmlands across several prefectures [54].”), allowing the agricultural potential of the Chengdu Plain to be fully realized. Coupled with the importance of Sichuan salt, tea, and other goods, this period saw Sichuan not only become a regional economic center but also accumulate a considerable number of architectural heritage sites such as temples and monasteries. Furthermore, both core areas accumulated substantial material foundations, and the technological standardization brought about by the implementation of the Yingzao Fashi significantly enhanced the durability of timber structures, providing structural assurance for the preservation of these heritage clusters. The “axial diffusion” pattern in the Ming and Qing periods was directly linked to the unprecedented development of the commodity economy and the improvement of the water transport network. Market towns flourished along the Yangtze River, and merchant capital (e.g., from Huizhou and Shanxi merchants) was heavily invested in the construction of residences, ancestral halls, and guildhalls. The proverb “No town is complete without a Huizhou merchant” accurately depicts the reality of architectural heritage diffusion along the river during this period. This evolution essentially represents the spatial epic of the Yangtze River Basin’s transition from the periphery of Chinese civilization to the national economic and cultural core, ultimately achieving integration across the entire region through internal networking.

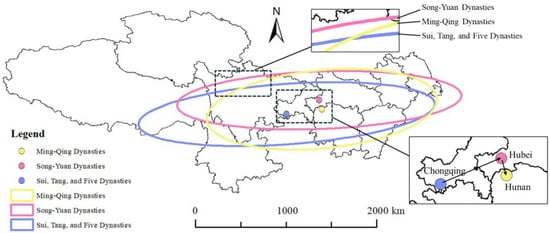

3.3.3. Directional Shift and Centroid Movement

Utilizing ArcGIS 10.8 software, the spatial evolution of ancient architectural heritage in the Yangtze River Basin was quantitatively analyzed using the Standard Deviational Ellipse (SDE) method (Figure 8), which clearly reveals the directional characteristics of its spatial distribution and the trajectory of its center of gravity shift. The major axis of the SDE represents the primary direction of the heritage distribution, while the minor axis reflects the degree of spatial concentration. A longer major axis indicates a wider distribution range, and a shorter minor axis signifies stronger agglomeration in the perpendicular direction.

Figure 8.

Historical Evolution of the Standard Deviational Ellipse and Mean Center.

The analysis results show significant differences in the shape and orientation of the ellipses across the three historical periods. During the Sui, Tang, and Five Dynasties period, the major semi-axis of the SDE was relatively long and exhibited a distinct east–west orientation, indicating that the heritage during this period was primarily distributed extensively along the east–west direction; the shorter minor semi-axis reflects a relatively concentrated distribution in the north–south direction. This pattern aligns with the spatial characteristics of the Sui-Tang period, where the Yangtze River Basin was not yet fully developed, and heritage sites were mainly scattered across several relatively independent local cultural centers. By the Song–Yuan period, the lengths of the major and minor semi-axes changed little, but the direction of the major axis shifted slightly towards the northeast-southwest, and the distribution center of gravity also moved northeastward. This subtle yet important shift indicates that the heritage distribution began to be influenced by the development of the eastern coastal regions, echoing the macro-trends of the southward shift of the economic center, the improvement of the canal system, and the rise of maritime trade after the Song Dynasty. It marks the initial emergence of the lower Yangtze’s status in the national economic landscape. In the Ming–Qing period, the ellipse morphology changed significantly: the major semi-axis shortened noticeably, while the minor semi-axis lengthened correspondingly. This morphological transformation indicates a reduced dispersion of heritage distribution in the primary direction and an increased spread in the perpendicular direction, resulting in a more balanced overall spatial pattern. Concurrently, the distribution center of gravity moved further southeastward, which corresponds perfectly with the historical processes of the highly prosperous commodity economy in the Jiangnan region, the dense network of market towns, and the comprehensive development of the central Yangtze region during the Ming and Qing periods. This signifies that economic development and heritage distribution within the Yangtze River Basin reached a new state of spatial integration.

The analysis of the evolutionary path of the Standard Deviational Ellipse, from a spatial econometric perspective, confirms the evolutionary trajectory of the ancient architectural heritage distribution in the Yangtze River Basin from “peripheral aggregation” to “basin-wide diffusion.” It profoundly reveals the spatial response mechanism to the underlying shifts in the economic center and regional development processes.

4. Conclusions

Based on the comprehensive analysis of the spatial and temporal distribution of ancient architecture in the Yangtze River Basin using ArcGIS and spatial statistical methods, the following conclusions can be drawn:

- (1)

- The spatial distribution exhibits a significant “multi-center agglomeration and axial diffusion” pattern. At the whole-basin scale, ancient architecture shows a clustered distribution (NNI = 0.381), forming a dual-core structure with the Jiangsu–Anhui region in the lower reaches as the primary core and the Sichuan Basin as the secondary core. The central region displays a transitional clustered–random state, while the western region, though sparsely populated, also shows local clustering, collectively reflecting a pattern of local concentration within global dispersion.

- (2)

- The study establishes a critical quantitative baseline for the heritage stock, confirming a temporal pyramid dominated by Ming–Qing (74.56%) and Song–Yuan (18.60%) structures. While this trend aligns with the expected survival bias for wooden architecture, our analysis delves deeper to explicate its specific drivers: the technological leap from the Yingzao Fashi that enhanced Song–Yuan preservation, and the unprecedented construction boom during the Ming–Qing era fueled by economic center migration. This temporal characterization is not trivial, as it provides the essential context for interpreting the spatial patterns; the identified “dual-core structure” is primarily a phenomenon of these most-represented periods.

- (3)

- The spatio-temporal evolution follows a trajectory from “marginal aggregation” to “dual-core structure” and finally to “axial diffusion.” This evolution is deeply rooted in macroscopic historical processes. The southward migration of the economic center, the development of the water transport network, and the standardization of building techniques provided the foundational momentum. At a regional level, diverse social adaptations—such as the integration of merchant capital with gentry culture in the east, cultural convergence in the central transition zone, and responses to the natural environment and sacred spatial order in the west—collectively shaped this distinctive evolutionary path.

- (4)

- The spatial equilibrium analysis reveals a significant imbalance, influenced by both historical processes and modern administrative divisions. The Gini coefficient of 0.393 and the distinct Lorenz curve confirm the unevenness of the distribution. The core areas (Sichuan, Jiangsu, Anhui) are concentrated in historically developed agricultural civilization zones, while the apparent scarcity in the peripheral areas (e.g., Qinghai, Chongqing, Shanghai) is not solely due to a lack of heritage but is also related to factors such as different civilizational forms (e.g., pastoralism in Qinghai) and the small areal extent of modern administrative divisions, which can obscure the true cultural geography.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.L., K.R. and X.X.; methodology, C.L. and K.R.; software, C.L., H.Y. and K.K.; validation, C.L., X.X., K.K. and H.Y.; formal analysis, C.L., K.R. and X.X.; investigation, K.R., X.X. and H.Y.; resources, X.X. and J.F.I.L.; data curation, C.L. and K.K.; writing—original draft preparation, C.L.; writing—review and editing, C.L. and X.X.; visualization, C.L. and K.K.; supervision, X.X. and J.F.I.L.; project administration, X.X. and J.F.I.L.; funding acquisition, X.X. and J.F.I.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the MOE Project of Key Research Institute of Humanities and Social Sciences at Universities (Grant No. 22JJD850009), Research project funded by Macao Polytechnic University (RP/ESCHS-02/2021), the Postgraduate Scientific Research Fund Project of Guizhou Province (2024YJSKYJJ063), and Plan for Enhancing the Capacity of Scientific Research and Service in Local Economic and Social Development Strategies funded by Xianda College of Economics & Humanities Shanghai International Studies University (Z30001.25.802).

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used Grammarly for the purpose of grammar checking, spelling correction, and language polishing. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Wang, B.; Dai, L.; Liao, B. System Architecture Design of a Multimedia Platform to Increase Awareness of Cultural Heritage: A Case Study of Sustainable Cultural Heritage. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, D. Analysis of spatio-temporal distriburion characteristics of ancient architecture heritage in China. J. Arid Land Resour. Environ. 2018, 32, 194–200. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C. A comprehensive review of deep learning applications in ancient architecture preservation and analysis. In Proceedings of the 5th International Scientific and Practical Conference “Problems of Science Development in the Context of Global Transformations”, Zagreb, Croatia, 1–4 October 2024; p. 230. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C.; Zhao, W.; Xia, Y.; Gu, Q.; Li, H.; Cao, X.; Zhao, Y.; Liang, C.; Zhang, X. Holocene climatic transition in the Yangtze River region and its impact on prehistoric civilizations. Catena 2024, 238, 107886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, N.; Zhao, X.; Liang, X.; Liu, J.; Yang, P.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y. Field model-based cultural diffusion patterns and GIS spatial analysis study on the spatial diffusion patterns of Qijia Culture in China. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 1422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, J.; Mao, H. Study on the spatiotemporal distribution patterns and influencing factors of cultural heritage: A case study of Fujian Province. Herit. Sci. 2024, 12, 324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, M.; Bai, Q.; Lyu, H.; Zhang, L. Spatiotemporal evolution and human-environment relationships of early cultural sites from the Longshan to Xia-Shang periods in Henan Province, China. Npj Herit. Sci. 2025, 13, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Dong, Y. Ontology Construction of Digitization Domain for Ancient Architecture. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 7651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, K.; Teri, G.; Cheng, C.; Tian, Y.; Huang, D.; Ge, M.; Fu, P.; Luo, Y.; Li, Y. Evaluation of commonly used reinforcement materials for color paintings on ancient wooden architecture in China. Herit. Sci. 2024, 12, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Guo, M.; Zhou, J.; Liang, X. Analysis of static stiffness properties of column-architrave structures of ancient buildings under long term load-natural aging coupling. Structures 2024, 59, 105688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, X.; Ma, M.; Ji, J.; Zheng, L. The spatial distribution of traditional intangible cultural heritage medicine of China and its influencing factors. Herit. Sci. 2023, 11, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Wu, C.; Xu, W.; Shen, Y.; Tang, F. Emerging trends in GIS application on cultural heritage conservation: A review. Herit. Sci. 2024, 12, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, L.; Wang, X.; Guo, H.; Lasaponara, R.; Shi, P.; Bachagha, N.; Li, L.; Yao, Y.; Masini, N.; Chen, F.; et al. Google Earth as a Powerful Tool for Archaeological and Cultural Heritage Applications: A Review. Remote Sens. 2018, 10, 1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, B.; Gonçalves, J.; Almeida, P.G.; Martins-Nepomuceno, A.M.T. GIS-based inventory for safeguarding and promoting Portuguese glazed tiles cultural heritage. Herit. Sci. 2023, 11, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrighi, C.; Ballio, F.; Simonelli, T. A GIS-based flood damage index for cultural heritage. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2023, 90, 103654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaddi, R.; Cacace, C.; Di Menno Di Bucchianico, A. The risk assessment of surface recession damage for architectural buildings in Italy. J. Cult. Herit. 2022, 57, 118–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y. Bibliometric analysis of GIS applications in heritage studies based on Web of Science from 1994 to 2023. Herit. Sci. 2024, 12, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhang, J.; Cenci, J.; Becue, V. Spatial distribution characteristics and influencing factors of the world architectural heritage. Heritage 2021, 4, 2942–2959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Yang, R.; Wang, P.; Yang, A.; Chen, G. A quantitative description of the spatial–temporal distribution and evolution pattern of world cultural heritage. Herit. Sci. 2021, 9, 80. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, Y.; Han, Q.; Zhang, Z.; Sun, Z.; Dai, J. Spatiotemporal Distribution and Evolution of Global World Cultural Heritage, 1972–2024. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2025, 14, 190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsarenko, S. Modeling the paths of ethno-political traditions and building cultural routes by means of ethnodesign and GIS. Cult. Contemp. 2024, 26, 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Sun, H.; Xu, S.; Aoki, N. Analysis of the Spatial and Temporal Distribution and Reuse of Urban Industrial Heritage: The Case of Tianjin, China. Land 2022, 11, 2273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Cai, J. Research on the spatial and temporal distribution and evolution characteristics of ancient architectural heritage in Southeastern Zhejiang. Sustainability 2023, 15, 16618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Tian, G.; Wei, K.; Ma, Y.; Zhang, S.; Huang, Y.; Yao, X. The influence of environment on the distribution characteristics of historical buildings in the Songshan Region. Land 2022, 11, 2094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, H.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Huang, J.; Yue, X.; Chen, F. Spatial distribution and typological classification of heritage buildings in Southern China. Buildings 2023, 13, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, K.; Jiang, X.; Zhu, R.; Duan, X.; Yang, J. Spatial and Temporal Distribution Characteristics of Heritage Buildings in Yangzhou and Influencing Factors and Tourism Development Strategies. Buildings 2025, 15, 1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Wang, J.; Sun, J.; Ye, F.; Zhang, H. Spatio-temporal distribution characteristics of intangible cultural heritage and tourism response in the Beijing–Hangzhou Grand Canal basin in China. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Chen, M.; Zhang, H.; Ye, F. Intangible Cultural Heritage in the Yangtze River Basin: Its Spatial Distribution Characteristics and Influencing Factors. Sustainability 2023, 15, 7960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhang, T.; Duan, L.; Liritzis, I.; Li, J. Spatial distribution characteristics and influencing factors of intangible cultural heritage in the Yellow River Basin. J. Cult. Herit. 2024, 66, 254–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, B.; Bai, K.; Sun, X.; Wang, M.; Liu, Y. Spatial distribution and tourism competition of intangible cultural heritage: Take Guizhou, China as an example. Herit. Sci. 2023, 11, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.; Liu, W.; Jia, Y.; Jin, Y. Characterization of Territorial Spatial Agglomeration Based on POI Data: A Case Study of Ningbo City, China. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Xiang, H.; Liu, R. Spatial pattern and influencing factors of intangible cultural heritage of music in Xiangxi, central China. Herit. Sci. 2022, 10, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Cenci, J.; Becue, V.; Koutra, S. Analysis of spatial structure and influencing factors of the distribution of national industrial heritage sites in China based on mathematical calculations. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 27124–27139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ju, X.; Yang, C.; Zhao, M.; Xu, Y.; Zhou, D.; Zhang, Y. Spatial distribution characteristics and influencing factors of traditional villages in Zhejiang, Anhui, Shaanxi, Yunnan Provinces. Econ. Geogr. 2022, 42, 222–230. [Google Scholar]

- Bian, J.; Chen, W.; Zeng, J. Spatial Distribution Characteristics and Influencing Factors of Traditional Villages in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 4627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hai, T. Spatial distributive characteristics and its influencing factors of traditional villages in Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei Region. Econ. Geogr. 2020, 40, 143–149. [Google Scholar]

- Pommerening, A.; Szmyt, J.; Zhang, G. A new nearest-neighbour index for monitoring spatial size diversity: The hyperbolic tangent index. Ecol. Model. 2020, 435, 109232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.; Xu, P.; Ma, P. Temporal and spatial distribution of intangible cultural heritage and its influencing factors in Jiangsu Province. Sci. Geogr. Sin. 2021, 41, 1598–1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, D.; Huang, C.; Lin, F. Spatio-temporal evolution characteristics of cultural heritage sites and their relationship with natural and cultural environment in the northern Fujian, China. Herit. Sci. 2024, 12, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Cui, Z.; Fan, T.; Ruan, S.; Wu, J. Spatial distribution of intangible cultural heritage resources in China and its influencing factors. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 4960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Qian, Y.; Li, Z.; Tong, T. Identifying factors influencing the spatial distribution of minority cultural heritage in Southwest China. Herit. Sci. 2024, 12, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stief, A.; Baranowski, J. Fault diagnosis using Interpolated Kernel Density Estimate. Measurement 2021, 176, 109230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Wu, Q.; Wei, P.; Zhao, H.; Zhang, X.; Pang, C. Explore the Mitigation Mechanism of Urban Thermal Environment by Integrating Geographic Detector and Standard Deviation Ellipse (SDE). Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 3411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefever, D.W. Measuring geographic concentration by means of the standard deviational ellipse. Am. J. Sociol. 1926, 32, 88–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, G.; Chen, H.H.; Li, J.; Wu, D.; Xu, X.L. Exploring the spatiotemporal evolution and risk factors for total factor energy productivity in Guangdong Province, China. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 373, 123395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, X. The Book of Jin; Shanghai Hanfen Pavilion Photocopying: Shanghai, China, 646; Volume 64. [Google Scholar]

- Han, Y. Preface to the Tang Dynasty Han Changli Corpus; The Commercial Press: Shanghai, China, 1934; Volume 19, ISBN 10186-686. [Google Scholar]

- Sima, Q. Volume 29: Treatise on Rivers and Canals. In The Records of the Grand Historian (Shiji); Zhonghua Book Company: Beijing, China, 2019; Volume 29, ISBN 9787101142365. [Google Scholar]

- Sima, Q. Volume 129: Biographies of Merchants. In The Records of the Grand Historian (Shiji); Zhonghua Book Company: Beijing, China, 2019; Volume 129, ISBN 9787101142365. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, Y. The Book of the Later Han; Zhonghua Book Company: Beijing, China, 2016; Volume 86, ISBN 9787101113594. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J. Yingzao Fashi; Chongqing Publishing House: Chongqing, China, 2018; ISBN 9787229136130. [Google Scholar]

- Dai, S. The Book of Rites (Li Ji); Zhonghua Book Company: Beijing, China, 2017; ISBN 9787101128567. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, C. Gazetteer of Wu Prefecture (Wu Jun Zhi); Jiangsu Ancient Books Publishing House: Nanjing, China, 1998; Volume 50, ISBN 9787806430972. [Google Scholar]

- Tuo, T. History of Song; Zhonghua Book Company: Beijing, China, 1985; Volume 247, ISBN 9787101003239. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).