Abstract

Migrant construction workers make up a significant portion of the workforce in many countries and play a crucial role in alleviating the skilled labor shortage. Although vocational education and training (VET) is essential for equipping these workers with the skills needed to enhance workforce quality and bridge the skills gap, their intentions to attend VET (IAVET) remain relatively low. Drawing on the theory of planned behavior (TPB), this study investigates the antecedents of IAVET among migrant construction workers and explores the moderating role of work pressure. A questionnaire survey was conducted among 547 construction workers in China, followed by exploratory factor analysis, confirmatory factor analysis, and structural equation modeling. The results show that social support has a significant positive correlation with IAVET. Moreover, the three planned behavioral factors mediate the relationship between social support and IAVET, with the mediating effects varying depending on the level of work pressure experienced by workers. Notably, subjective norms (SN) emerge as the strongest mediator, while work pressure (WP) significantly moderates both the direct and indirect pathways, highlighting their critical roles in shaping VET participation intentions. These findings provide valuable insights into the mechanisms through which social support influences migrant construction workers’ IAVET, offering practical implications for improving workforce skills and addressing the skilled labor shortage in the construction sector and similar industries worldwide. Overall, the study strengthens the theoretical explanatory power of the extended TPB framework and offers actionable guidance for policymakers and construction enterprises to enhance migrant workers’ engagement in VET.

1. Introduction

The construction industry, as a major driver of the global economy and provider of extensive employment opportunities, faces a critical shortage of skilled labor worldwide [1,2]. In the United States, 80% of general contractors report difficulties in recruiting skilled craft workers [3], and in the UK, 36% of construction vacancies are due to skill shortages [4]. This shortage is particularly acute in China, where the sector, contributing approximately 7% to the nation’s GDP, faces a deficit of over 2 million skilled workers [5]. Such shortages hinder construction quality and productivity [6] and may delay urban development and economic growth [7]. Moreover, in China, over 53 million construction workers are migrant workers who relocate from rural areas to urban centers within the country for work [8]. These workers typically possess limited formal education and skills, making them particularly vulnerable to the challenges posed by technological advancements (e.g., digitization and human–robot collaboration) in the industry [9,10]. The underskilled nature of the migrant workers exacerbates the inconsistency in construction quality and safety issues, as many workers may not possess the specialized skills needed to meet modern construction standards and technological demands [8,11]. Therefore, enhancing the skill levels of migrant workers is paramount to relieving the skilled labor shortage in China.

Vocational education and training (VET), designed to equip individuals with the necessary skills, knowledge, and competencies for specific trades [12], is widely recognized as an effective approach to enhancing labor skills. Many developed countries have constructed mature VET systems, including Germany’s “dual system,” which combines classroom education with on-the-job training in partnership with private companies; the UK’s ‘apprenticeship system,’ which offers government-funded training programs tailored to industry needs; and the United States’ ‘registered apprenticeship system,’ which provides structured training pathways and certification for skilled trades [13]. These systems effectively integrate training and certification mechanisms across diverse entities, including governments, enterprises, and social organizations, with the purpose of enhancing the skills of construction workers [14]. China has introduced a wide range of national VET initiatives, such as vocational high school expansion, large-scale upskilling subsidies, enterprise apprenticeship pilots, and international cooperation programs, to improve workforce skills [15]. However, despite this policy momentum, implementation remains uneven. Migrant construction workers frequently report restricted training access, inconsistent employer participation, and fragmented governance across agencies and firms [16]. These persistent institutional and organizational challenges influence how workers perceive the feasibility and value of participation. Limited funding support and irregular employer involvement can undermine workers’ confidence that training is encouraged or beneficial. In addition, decentralized arrangements and inflexible schedules often conflict with long working hours and unstable employment conditions, making participation difficult in practice. The absence of visible role models or successful training cases in many construction enterprises further reduces positive expectations surrounding VET. As a result, despite national programs, many migrant construction workers still show low motivation to participate in formal training. This disconnect between policy design and workers’ lived experiences underscores the need for a theoretically grounded examination of the individual, social, and workplace factors that shape migrant workers’ intentions to participate in VET. In China’s collectivist and relationship-oriented work environment, these intentions are strongly influenced by workers’ attitudes toward training, their perceptions of social expectations, and their sense of control over their own behavior. These influences align closely with the three core components of the TPB, making TPB a particularly suitable framework for understanding migrant construction workers’ VET participation in the Chinese context.

Existing studies have investigated specific factors inhibiting construction workers’ intentions to attend vocational education and training (IAVET) (e.g., [2,17]). Johari and Jha [2] found that the lack of social support (SS) is a key contributing factor to an individual’s insufficient training motivation. Moreover, Zhang et al. [18] identified work pressure (WP) as a pivotal factor influencing construction workers’ IAVET. Nevertheless, the underlying mechanisms linking SS and WP to IAVET, particularly among Chinese migrant construction workers, remain underexplored within the theory of planned behavior (TPB). First, SS is deeply embedded in Chinese society and its construction sector, manifesting through collectivist and Confucian values, strong family structures, and government initiatives [19]. This is especially relevant for migrant construction workers who often face harsh work conditions and the instability of temporary, project-based employment. Second, although TPB has been widely applied to explain individual intentions and behaviors in fields such as manufacturing, tourism, and project management [20,21], prior TPB–VET studies have largely focused on internal cognitive determinants such as attitudes, social norms, and perceived behavioral control. These studies typically assume stable, well-resourced environments with clear organizational responsibilities and therefore rarely consider how external social environments or high-pressure work contexts systematically shape TPB constructs. As a result, existing TPB–VET research offers limited explanatory power for vulnerable and resource-constrained labor groups such as migrant construction workers, who often experience substantial work stress, institutional ambiguity, and inadequate access to support systems [22]. Third, the extremely tight schedules and long working hours in the Chinese construction sector subject migrant workers to severe work pressure, physical exhaustion, and mental stress, significantly impacting their capacity and willingness to engage in VET [23]. Recent evidence also indicates that prolonged physical and psychological strain can reduce workers’ available energy and cognitive resources for additional training activities, thereby lowering their readiness to participate in VET [24]. Moreover, migrant workers’ perception of occupational risks, including chemical and environmental hazards, has been found to influence their engagement in safety programs and training-related behaviors, as high perceived risks may heighten stress levels or shift attention away from skill development opportunities [25]. Understanding the moderating role of WP on the relationship between SS and IAVET may enable the development of tailored interventions that address the specific needs of migrant workers, thereby enhancing their willingness to participate in VET.

To fill the research gap, this study aims to investigate the relationship between social support and migrant construction workers’ intention to participate in vocational education and training, based on TPB. To achieve this research aim, three research objectives (ROs) are proposed:

RO1: investigate the relationship between SS and IAVET among Chinese migrant construction workers;

RO2: evaluate the mediating role of the three PBFs in this relationship;

RO3: analyze the moderating effect of WP on the relationship between SS and IAVET.

2. Theoretical Framework and Hypothesis Development

2.1. Theory of Planned Behavior

Originating from social psychology, TPB has been widely applied across fields, including nursing, behavioral science, and management, providing a crucial framework for understanding the mechanisms of individual behavior formation [21,26,27]. According to TPB, behavioral intention is shaped by attitudes (ATT), subjective norms (SN), and perceived behavioral control (PBC) [28]. ATT refers to individuals’ positive or negative evaluations of a specific behavior [29], and SN pertains to individuals’ perceptions of and responses to others’ viewpoints and societal expectations regarding a specific behavior [30], while PBC reflects individuals’ beliefs in their ability (e.g., time, money, energy, and self-confidence) to engage in a particular behavior [31]. These dimensions collectively provide a comprehensive framework for examining behavioral intentions, making TPB particularly suitable for understanding the migrant construction workers’ IAVET.

In construction studies, TPB has been primarily used to explain work-related behaviors. For instance, Zheng et al. [21] adopted TPB to examine factors influencing senior managers’ relational behavior in participating organizations within megaprojects and identified PBC as a critical factor. Similarly, Yuan et al. [20] explored factors motivating project managers’ waste reduction intentions through TPB and found that ATT plays the most significant role in predicting their intentions. More recently, Zhao et al. [32] conducted an empirical study using an extended TPB framework and found that PBFs mediate the relationship between job satisfaction and professionalization behavior among new-generation migrant construction workers. Following previous studies, this study adopts an extended TPB framework to explore the formation mechanisms of migrant construction workers’ IAVET within the Chinese construction industry.

2.2. Hypotheses and Research Model

2.2.1. SS, PBFs, and Migrant Construction Workers’ IAVET

SS, encompassing both tangible (e.g., financial assistance, material resources) and intangible (e.g., emotional support, informational guidance) assistance from family, community, and organizations, plays a crucial role in helping individuals tackle challenges or stressful situations [33]. For migrant construction workers, who often face long working hours, insecure employment, and social isolation, SS is particularly important in enabling access to learning and development opportunities [23]. Prior studies indicate that supportive environments increase migrant workers’ willingness to participate in training by reducing practical and motivational barriers [2,34]. However, a critical gap in the literature lies in understanding how SS influences IAVET within the TPB framework. This study proposes that SS influences IAVET through its impact on PBFs. Specifically, inadequate government and corporate support for VET can adversely affect migrant workers’ attitudes toward training, leading them to perceive it as non-remunerative and irrelevant to career development, thus decreasing their IAVET [35]. Additionally, given that migrant construction workers often operate within close-knit social groups [22], SN plays a significant role since support from colleagues, supervisors, and organizations can create a social environment that values VET, thereby increasing IAVET [36,37]. Furthermore, SS can increase PBC by providing resources and encouragement that enhance self-efficacy, confidence, and motivation [38]. This is particularly important for migrant workers who face financial and time constraints, helping them overcome these barriers and feel more capable of engaging in VET [22].

Based on the literature review results, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H1.

SS has a positive impact on the IAVET of migrant construction workers.

H2.

SS positively impacts the three PBFs of migrant construction workers.

H2a.

SS has a positive impact on the ATT of migrant construction workers.

H2b.

SS has a positive impact on the SN of migrant construction workers.

H2c.

SS has a positive impact on the PBC of migrant construction workers.

2.2.2. PBFs and Migrant Construction Workers’ IAVET

The TPB posits that intention is directly predicted by three PBFs, namely ATT, SN, and PBC. ATT reflects migrant construction workers’ positive or negative perceptions of participating in VET. As a core TPB component, ATT has been consistently identified as a significant predictor of behavioral intentions across various domains [39,40]. Individuals holding positive attitudes toward a behavior are more likely to engage in it [20]. In the context of VET, this suggests that migrant workers who perceive training as valuable for their career advancement, skill enhancement, or personal development will be more inclined to participate. This aligns with research on learning goal orientation, which demonstrates that individuals with strong self-improvement motives exhibit higher willingness to learn [41] and are more likely to engage in employee development activities [42].

In addition, previous research has consistently found a positive correlation between SN and individuals’ behavioral intentions [43,44]. This is supported by organizational behavior theory, which emphasizes how the external environment shapes individual behavior, as people tend to align their behavior with social norms to gain social acceptance and approval [45]. For migrant construction workers, the opinions and support of their social networks can significantly influence their IAVET. If VET is perceived as valued and encouraged by these groups, workers are more likely to engage in it.

According to the TPB, higher levels of PBC lead to stronger behavioral intentions [46]. For migrant construction workers, PBC encompasses their perceived ability to access and complete training programs, often constrained by long working hours, financial limitations, and limited training availability. While government initiatives encourage enterprises to support migrant worker training [47], practical constraints such as schedule conflicts and concerns about lost income during training continue to hinder participation [2]. Therefore, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H3.

PBFs positively impact the IAVET of migrant construction workers.

H3a.

The ATT of migrant construction workers positively influences their IAVET.

H3b.

The SN of migrant construction workers positively influences their IAVET.

H3c.

The PBC of migrant construction workers positively influences their IAVET.

Additionally, drawing upon the established links between SS and PBFs (as discussed in Section 2.2.1) and the influence of PBFs on IAVET, this study proposes that PBFs mediate the relationship between SS and IAVET. Thus, the following hypotheses are established:

H4.

PBFs play a mediating role between SS and the IAVET of migrant construction workers.

H4a.

ATT plays a mediating role between SS and the IAVET of migrant construction workers.

H4b.

SN plays a mediating role between SS and the IAVET of migrant construction workers.

H4c.

PBC plays a mediating role between SS and the IAVET of migrant construction workers.

2.2.3. The Moderating Role of WP

WP refers to workplace stress that surpasses an individual’s coping capacity, encompassing physical, psychological, and social pressures, which negatively impacts individuals’ overall health and mental well-being [48]. The resource conservation theory [49] provides a theoretical framework for understanding how stress affects individuals’ resource allocation. This theory suggests that when individuals experience stress and perceive a risk of resource loss, they become more vulnerable to further resource depletion. The construction industry is widely recognized as a high-pressure sector, characterized by long hours, demanding tasks, and hazardous working environments [34,50]. These conditions place significant strain on construction workers, particularly migrant workers who often face additional challenges such as social isolation, precarious employment, and limited access to support systems. Under such conditions, engaging in VET could be perceived as an additional burden, further straining already limited resources. Therefore, the positive influence of SS on IAVET is likely to weaken under high WP. Therefore, we propose the following hypothesis:

H5a.

WP negatively moderates the direct effects of SS.

Additionally, WP moderates the indirect effects of SS on IAVET through PBFs. Regarding ATT, the labor-intensive and physically demanding nature of construction work places migrant workers at a higher risk of physical fatigue, potentially reducing their capacity to engage in activities beyond their immediate job responsibilities [51,52]. Therefore, while they may recognize the value of VET, high WP can hinder the translation of positive attitudes into actual participation, weakening the effect of ATT on IAVET.

For SN, high WP elevates cognitive load and narrows workers’ attention to immediate work tasks [53], making them less responsive to peer expectations or organizational encouragement. It also increases turnover intention and psychological detachment [54], thereby reducing the extent to which SS can strengthen SN and, in turn, IAVET. High WP also undermines PBC by increasing mental stress and making it difficult to balance work and personal responsibilities [55]. Zhang et al. [18] reported that Chinese migrant construction workers often face frequent night shifts, inflexible schedules, and unpredictable job demands, leaving them too overwhelmed to pursue VET. Therefore, the positive effect of SS on PBC and IAVET may weaken under high WP. Conversely, in low WP situations, individuals are more likely to act in accordance with their beliefs and values, strengthening the positive impact of PBC on intentions [56]. Thus, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H5b.

WP negatively moderates the mediating effect of ATT.

H5c.

WP negatively moderates the mediating effect of SN.

H5d.

WP negatively moderates the mediating effect of PBC.

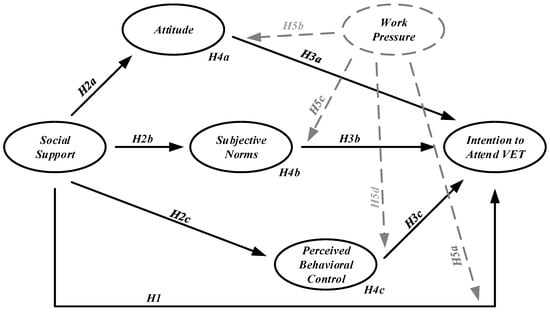

Figure 1 presents the hypothesized model of migrant construction workers’ IAVET, which extends the TPB model by incorporating SS and WP. The proposed model consists of PBFs (i.e., ATT, SN, and PBC) as mediating factors and two new factors (i.e., SS and WP) as extrinsic factors.

Figure 1.

Hypothetical model.

3. Research Methods

3.1. Data Collection

3.1.1. Questionnaire Development

A questionnaire survey approach was adopted to test the proposed hypotheses and model. A systematic literature review supported the development of the questionnaire, which was further modified based on the Chinese construction industry context through semi-structured interviews and a pilot study.

(1) Literature review: The measurement items for the six variables were adapted from established literature, as summarized in Table 1. A four-item scale was developed to measure SS, drawing on the studies of Chandrasekaran and Ganeshprabhu [57] and Gopalakrishnan and Brindha [58]. The PBFs and IAVET were assessed using a thirteen-item scale, adapted from Cammarata et al. [59] and Wang et al. [60]. Additionally, WP was measured using a three-item scale, based on the research of Zhang et al. [61] and Kamardeen and Sunindijo [62]. These scales were selected to ensure the reliability and validity of the constructs in the context of migrant construction workers.

Table 1.

Measurement items and sources (source: authors’ own work).

(2) Semi-structured interviews: To ensure the questionnaire’s structure, relevance, and data collection effectiveness, semi-structured interviews were conducted with five experts, each possessing at least ten years of construction experience. The panel comprised three project managers, who represented diverse project types and company sizes; one industry administrator, responsible for workforce development standards and best practices; and one academic researcher, who possessed extensive research experience in construction management, vocational training, and migrant worker issues. The interviews explored several key areas to enhance the questionnaire’s applicability to migrant construction workers, each lasting between 30 and 60 min. Based on experts’ feedback, the clarity and comprehensiveness of the questions, their relevance to Chinese migrant construction workers, and the potential influence of cultural and linguistic differences on questionnaire interpretation were enhanced.

(3) Pilot study: A pilot study was conducted at two construction sites in Nantong to uncover potential errors and ambiguities, as well as evaluate the wording and the estimated duration of the questionnaire. A total of 30 questionnaires were distributed in person for the pilot study, of which 25 were completed and returned. Participants were approached during their break times and provided with a brief explanation of the research purpose. They were assured of anonymity and confidentiality. The average completion time for the questionnaire was 12 min, which is notably longer than the typical response time. In addition, most workers completed the questionnaire with the help of verbal explanations from the researchers, suggesting significant complexity of the questionnaire and high cognitive load suffered by the workers. For comparison, Yeo et al. [63] reported an average completion time of 20–25 min for questionnaires with more than three times the number of items used in this study. This longer completion time, coupled with feedback from participants, suggested that migrant workers encountered difficulties understanding the original wording of certain questions due to their relatively low educational levels. Therefore, some statements of questions were modified for clarity in the formal survey. For example, “Will the presence of co-workers affect your intention to improve your skills?” was revised to “If my colleagues around me are attending skill training, I would also choose to join them.” Similarly, “The appropriateness of workload” was modified to “The amount of work I have to complete each day is appropriate.” Personal pronouns in the measurement items were also revised to first- or second-person perspectives for better accessibility (see Table 1).

The finalized questionnaire comprises two sections. Section 1 aimed to gather demographic information from respondents, including age, gender, residence status, educational background, and skill certificate level. Section 2 measured the type of SS they prefer (four items), the degree of agreement on ATT (three items), SN (three items), and PBC (three items), as well as the level of IAVET (four items) and WP (three items). A five-point Likert scale was employed in Section 2, in which 1 = strongly disagree, 3 = neutral, and 5 = strongly agree.

3.1.2. Research Sampling

The finalized questionnaire was distributed in Nantong, Jiangsu Province, a city with a substantial construction sector in China. In 2023, Nantong had 1508 qualified general contractors and a construction industry output exceeding RMB1.2 trillion [64], making it a representative location for studying migrant construction workers. Moreover, Nantong is one of the major labor-importing cities in the Yangtze River Delta, attracting a large influx of migrant workers from various provinces. This demographic structure closely mirrors the broader composition of China’s construction workforce, providing a suitable context for examining migrant workers’ VET-related intentions. The questionnaire was distributed across seven ongoing construction sites, selected to encompass diverse project types and scales. Site inspections were first conducted, with permissions obtained from project managers to proceed with the survey. Within each site, approximately 60–120 migrant workers were systematically and randomly sampled to mitigate potential clustering effects. A total of 552 questionnaires were collected, of which 547 were deemed valid after manually excluding those with incomplete or conflicting responses, yielding a valid response rate of 88.2%.

A sample size of 547 is considered adequate, as SEM studies commonly adopt minimum sample sizes of 100–200 cases to ensure stable estimation and sufficient statistical power [65]. Moreover, more recent guidelines for multivariate behavioral research classify samples of around 500 as “very good,” indicating that such sizes typically support robust parameter estimation in complex SEM models [66]. Accordingly, the final valid sample of 547 respondents not only exceeds the widely cited minimum thresholds but also meets the higher benchmarks recommended for high-quality SEM analysis, thereby providing a solid empirical foundation for model estimation and statistical reliability.

3.2. Data Analysis

3.2.1. Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA)

As a useful tool to explore latent factors for developing a new theory, EFA is first performed to explore the underlying constructs in this study [67]. Before conducting EFA, the data suitability was checked for normal distribution and sample adequacy, using Bartlett’s test and the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) measure [68,69]. The factor loadings of variables with a minimum threshold of 0.40 were considered [70]. Internal consistency was assessed using Cronbach’s alpha, with values above 0.6 deemed acceptable [71].

3.2.2. Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA)

CFA is conducted to examine the consistency between each factor and its corresponding measurement item, thereby gauging the validity of the theoretical framework. Additionally, CFA evaluates the degree to which the factor structure obtained from the EFA accurately represents the observed data [72]. To provide a comprehensive assessment of model fit, it is recommended to report multiple fit indices, including those suggested by Durdyev et al. [73].

3.2.3. Structural Equation Modeling (SEM)

SEM integrates measurement and analysis and is useful for handling latent variables that cannot be directly measured [74]. It can simultaneously estimate multiple factors, including complex relationships between measurement indicators and dependent, independent, and mediating variables [75]. Given the difficulty in directly observing variables such as attitudes and intentions and the large sample size, this study primarily used SEM to analyze the data.

3.2.4. Multiple Mediation Models

The multiple mediation model examines how an independent variable influences a dependent variable through multiple mediator variables [76]. It focuses not only on the total indirect effect but also on specific indirect effects. The process involves assessing the total effect, determining whether it is a complete or partial mediation effect, and evaluating the mediating effects of each path sequentially. The significance of mediation effects is determined by critical ratios (Z) and Bootstrap 95% confidence intervals (CIs), where a Z score greater than 1.96 and a confidence interval not including 0 indicates a significant mediation effect [77].

3.2.5. The Moderation Model

A moderation model evaluates how a moderator variable influences the relationship between other variables [78]. In this study, the data were categorized into two groups based on WP levels (i.e., high and low), and a multi-group SEM approach was employed to compare these groups. The analysis aims to determine whether the paths from SS to IAVET, both directly and indirectly through the PBF mediators, varied across different WP levels. The significance of the moderated mediation effects is assessed using the same methods, as illustrated in Section 3.2.4.

4. Research Results

4.1. Descriptive Analysis

Table 2 presents the demographic information of the respondents. Among the 547 valid responses, 501 were from male migrant construction workers and 46 from female migrant construction workers, suggesting the dominance of male employees in the construction industry. Most participants were from rural areas (94.9%) and aged 31–50 years (49.2%). In addition, 83.7% of the respondents had an education level of primary school or below, and their daily salaries were mostly in the range of RMB 250-450 (71.0%). Notably, 72.6% of the respondents reported lacking relevant skill certificates, revealing a substantial qualification gap within the workforce. This emphasizes an urgent need for effective and targeted vocational education and training mechanisms in the Chinese construction industry.

Table 2.

Respondents’ demographic characteristics (N = 547) (source: authors’ own work).

4.2. Results of EFA

Bartlett’s test of sphericity (Chi-square = 3490.104, df = 120, p < 0.001) supported the assumption of normal distribution. The KMO value of 0.869 indicated good sampling adequacy for factor analysis. The result suggested retaining five factors. One item (SS3) was removed from the 17 total items due to a factor loading below the cutoff value of 0.4. The internal consistency of these constructs ranged from 0.7 to 0.9, indicating adequate reliability for further analysis (see Table 3).

Table 3.

Results of EFA (source: authors’ own work).

The results of Harman’s one-factor test revealed that the unrotated exploratory factor analysis extracted five factors with eigenvalues greater than 1. The first factor explained 36.890% of the total variance, which is below the threshold of 40%. This suggests that there is no significant common method bias in this study [79].

4.3. Results of CFA

Table 3 provides a summary of the CA, CR, and AVE results. The values for CA, CR, and AVE exceeded the necessary thresholds of 0.7, 0.7, and 0.5, respectively. This demonstrates satisfactory internal consistency, reliability, and convergence for all constructs [73,80,81].

The data presented in Table 4 indicated that the CFA fit indices for the five primary latent constructs were acceptable (RMSEA = 0.054; RMR = 0.030; AGFI = 0.924; GFI = 0.949; IFI = 0.958; TLI = 0.944; CFI = 0.957; χ2/df = 2.600 < 3) [82].

Table 4.

Model fitting index for the mediation and moderation effects (source: authors’ own work).

Table 5 presents the AVEs and binary Spearman correlation analysis results. The significant correlations among ATT, SN, PBC, SS, and IAVET support the initial hypotheses. Additionally, the square root of the AVEs for each latent variable exceeds its correlation coefficients with other variables, indicating good discriminant validity of the measurements [83].

Table 5.

Means, standard deviations, and intercorrelations between study variables and standardized factor loadings (source: authors’ own work).

4.4. Hypothesis Testing

4.4.1. Overall SEM Results

Similar to the CFA results, the goodness of fit for the SEM model was assessed using the metrics provided in Table 4. The χ2/df is 2.992, and the value of RMSEA is 0.06, indicating that the SEM model is reasonable and not influenced by sample size.

Table 6 provides information on point estimate values, standard errors (S.E.), critical ratios (C.R.), and one-tailed significance of P for seven hypotheses in SEM. Findings show that H1, H2a, H2b, H2c, H3a, H3b, and H3c are all accepted, as a significant direct relationship is established between the latent variables with a C.R. greater than 1.96 and one-tailed significance of p < 0.05 [84].

Table 6.

Path relation test results of SEM (source: authors’ own work).

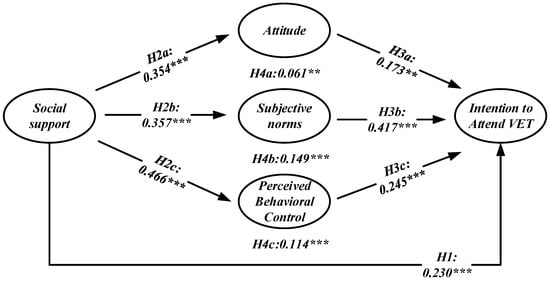

As shown in Figure 2, SS (β = 0.230) has a significant effect on migrant construction workers’ IAVET. This can be explained by real-world scenarios where migrant workers, living in a tight-knit worker community and relying heavily on peer networks, are more likely to engage in training when they receive encouragement and resources from colleagues and supervisors. Additionally, SS significantly influences ATT (β = 0.354), SN (β = 0.357), and PBC (β = 0.466) of migrant construction workers, with PBC demonstrating the strongest positive correlation with SS. In contrast, ATT (β = 0.173), SN (β = 0.417), and PBC (β = 0.245) are positively correlated with IAVET, with SN having the most significant impact. This aligns with the collectivist culture prevalent in the Chinese construction industry, where social expectations and peer influence play a pivotal role in migrant workers’ decision-making [19]. A mediation effect test was conducted to ascertain the relationships among ATT, SN, PBC, SS, and IAVET.

Figure 2.

Path analysis of mediating effects. Note: *** and ** indicate statistical significance at the 0.001 and 0.01 levels (two-tailed), respectively, supporting the presence of strong correlations among the variables.

As shown in Table 7, statistical significance is determined by Z-values above 1.96 and bootstrapped confidence intervals that do not include zero. The total effect of the model is significant, suggesting a mediating effect of PBFs on the relationship between SS and IAVET. The direct and indirect effects are also significant, indicating a partial mediation model. Therefore, H4 is verified. The mediating influence level of the PBFs is 58.5%. The point estimates for the total, direct, and indirect effects are 0.554, 0.230, and 0.324, respectively.

Table 7.

Results of the bootstrapping mediation analysis (source: authors’ own work).

In addition to examining the total indirect effect, specific indirect effects were also examined. As shown in Table 7, the specific indirect effects are ATT, SN, and PBC. All three mediation paths are significant, with corresponding estimates of ATT (0.061), SN (0.149), and PBC (0.114). Among them, SN exerts the strongest effect, supporting H4a, H4b, and H4c.

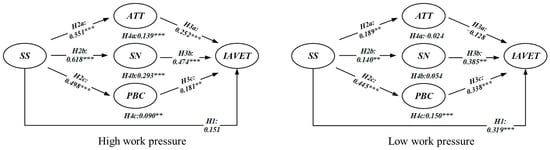

4.4.2. SEM Results Under High and Low WP Levels

Based on the categorization of WP, the model was further divided into two groups: those with low and high WP levels. These groups were then added to the model as moderating variables. The goodness-of-fit measurement results for the model, as shown in Table 4, demonstrated that the SEM fit indexes of the five main latent constructs were acceptable.

As shown in Table 8, effects are considered significant when Z-values exceed 1.96, and the bootstrapped confidence intervals do not include zero. Based on these criteria, the mediating effects differ noticeably between high and low WP levels. Under high-pressure levels, the results show significant total moderated mediation effects. Although SS exhibits no direct effect on IAVET, they are indirectly correlated with IAVET, with PBFs demonstrating a complete mediating effect. Under low pressure levels, total and direct effects were significant, with Z values of 4.116 and 2.874, respectively. Therefore, H5a is supported.

Table 8.

Moderated mediating effects of different work pressure (source: authors’ own work).

The mediating effects of ATT, SN, and PBC under different pressure levels were further examined. Under high WP, the mediating effects of ATT, SN, and PBC are all significant. This aligns with real-world observations where construction workers, often perceiving themselves as under-skilled, are more likely to seek training under high WP to improve their efficiency. Additionally, the typical collective living arrangements of Chinese migrant workers facilitate the reception of encouragement from colleagues and supervisors, thereby amplifying the influence of SS on PBFs under high-pressure conditions. In contrast, under low WP, the mediating effects of ATT and SN are not significant, whereas only the mediating effect of PBC remains significant. In practice, when WP is low, workers rarely take the initiative to enhance their skills unless they feel they have sufficient time, resources, and confidence (i.e., PBC) to engage in training. This comparison indicates that WP positively moderates the mediating effect of ATT and SN on the relationship between SS and IAVET, so both H5b and H5c are rejected. However, PBC plays a significant mediating role under both high and low WP levels, thus H5d is partially supported. These results are summarized and presented in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

SEM models under high and low work pressure. Note: *** and ** indicate statistical significance at the 0.001 and 0.01 levels (two-tailed), respectively, supporting the presence of strong correlations among the variables.

5. Discussion

5.1. Path Analysis of SS, PBFs, and the IAVET

The path analysis reveals that SS influences migrant construction workers’ IAVET both directly and indirectly by impacting the three PBFs (i.e., ATT, SN, and PBC). While previous research on adolescents’ entrepreneurial intentions also noted the direct influence of SS [85], this study extends existing knowledge by identifying the critical mediating roles of ATT, SN, and PBC:

- Among them, PBC demonstrates the strongest positive correlation with SS, suggesting the critical path of SS→PBC. This aligns with Costin et al. [86], who found that psychological support, including emotional encouragement from families and colleagues, can facilitate employees’ cognitive confidence in their abilities to access resources for behavior engagement.

- Besides, this research further uncovers the significant mediating roles of SN and ATT, which have been underexplored in the context of migrant construction workers. This addresses a critical gap in the literature by demonstrating how SS operates through multiple psychological pathways to shape training intentions. In the context of the Chinese construction industry, characterized by high work pressure and exacerbated by COVID-19 lockdown policies, migrant workers often experience significant work-family conflicts [87,88].

These findings underscore the importance of implementing effective psychological support systems. Such systems may include open communication channels, encouragement from family members and supervisors, improved working conditions, and mental health awareness programs. Together, these measures help mitigate work–family conflicts and enhance workers’ PBFs [89]. Beyond these mechanisms, the findings also point to a possible cultural pattern. Migrant construction workers often originate from rural communities where interpersonal obligations, deference to authority, and kinship-based social structures strongly influence daily decisions [90]. Such cultural tendencies, rooted in collectivistic norms, may amplify the salience of subjective norms and heighten workers’ responsiveness to socially endorsed expectations. Consequently, the prominence of the SN pathway in this study may not only reflect general psychological processes but also culturally embedded relational orientations. Recognizing this potential cultural bias is essential for interpreting the results, as the strength of SN may be less pronounced in more individualistic contexts. For future research, it would be valuable to explore the effectiveness of these psychological support systems in different cultural and organizational contexts. Additionally, future studies could investigate how technological interventions, such as digital platforms for mental health support or virtual training programs, might enhance the accessibility and impact of SS on migrant workers’ IAVET.

In addition, the path analysis reveals that SN exerts the most significant influence on migrant construction workers’ IAVET (SN→IAVET), indicating that their motivation for training engagement is substantially shaped by the influence of colleagues and supervisors (i.e., their opinions). This finding contradicts the traditional TPB, which typically regards SN as a weak predictor of behavioral intention [39,40]. The discrepancy can be elucidated through the lens of conformity psychology, where migrant construction workers tend to be group-oriented and collective in their workplace dynamics, leading to a tendency to align their beliefs and behaviors within a specific group [91]. When they observe their colleagues participating in skill improvement programs and benefiting from incentives provided by enterprises and the government, they are more inclined to attend VET and vice versa [92]. Moreover, the previously identified low qualifications of migrant construction workers in China can also explain this finding. Most of them come from rural areas and exhibit limited educational backgrounds and cognitive abilities, which may hinder their understanding of the benefits associated with skill development, such as career advancement and safety awareness [93]. This impediment results in a lack of motivation and confidence when it comes to enhancing their skills. Therefore, enhancing workers’ awareness of the benefits of vocational education and training is crucial for stimulating their IAVET. This can be achieved by introducing on-site counseling programs, providing adaptable training timetables, and encouraging site supervisors to act as mentors to guide workers at workplaces [93]. This finding fills a gap in the literature by highlighting the unique role of SN in shaping training intentions within collectivist cultures, particularly among low-skilled migrant workers who rely heavily on social validation.

5.2. Mediating Role of PBFs

The SEM analysis results reveal that PBFs mediate the relationship between SS and migrant construction workers’ IAVET, with SN exerting a predominant effect. This suggests the critical path of SS→SN→IAVET, indicating that the perceived support from others can instill a robust social expectation among migrant construction workers to engage in training activities actively. While this pattern aligns with prior studies showing the strong explanatory power of SN among Chinese groups [94,95,96], the dominance of SN should not be interpreted as a universal psychological mechanism. Instead, it likely reflects the influence of cultural factors, as in many Chinese settings, individuals tend to value group harmony, align with collective expectations, and monitor their behavior to maintain positive relationships. These tendencies may heighten workers’ sensitivity to normative pressures, making social approval more influential than personal ATT or PBC. Therefore, while SS helps create a supportive social environment for training participation, the strong effect of SN observed in this study may reflect culturally specific norms rather than general behavioral mechanisms. Future research should examine whether the predominance of SN persists in less collectivist contexts or among migrant workers with different cultural backgrounds to avoid overgeneralizing culturally contingent findings.

Moreover, the mediating effects of PBC and ATT on the relationship between SS and IAVET are also found to be significant. Prior research conducted in European training contexts, such as Froehlich et al. [97], has shown that SS can cultivate positive attitudes toward learning and promote engagement in new behaviors. Building on these findings, the present study further demonstrates that SS enhances both ATT and PBC, which together influence IAVET in the Chinese construction sector. For instance, practical interventions such as health and safety meetings and peer success stories can foster positive attitudes among workers [98], while supportive environments can enhance PBC, positively affecting career-related decision-making [99,100]. These insights provide a more comprehensive understanding of the mechanisms through which SS influences training intentions, addressing a gap in the literature by integrating multiple psychological pathways into the TPB framework.

5.3. Moderating Effects of WP

As shown in Table 8, the group comparison results reveal that under high WP, SS does not directly correlate with IAVET, but the mediating effect of PBFs remains significant. This finding supports the results of Laranjeira [101], who found that migrant construction workers prioritize task completion and coping mechanisms in high-pressure environments rather than seeking or accepting external social support. Zhang et al. [18] further noted that as part of traditional Chinese culture, migrant construction workers often keep mental health issues concealed and try to rely on personal coping strategies driven by a fear of losing face. This reliance on intrinsic motivations (i.e., PBFs) to manage stress and workload may increase cognitive load, making it challenging to engage in training through social support channels. However, this contradicts the findings of Pooladvand and Hasanzadeh [53], who pointed out that individuals tend to pay more attention to external support and question their internal beliefs under high pressure.

Conversely, in low WP scenarios, SS exerts both direct and indirect (i.e., with the mediation of PBFs) influence on migrant construction workers’ IAVET. Moreover, it is observed that SS exerts a more substantial direct impact (64%) on IAVET, compared to its indirect effects (36%) mediated by PBFs. This phenomenon may be attributed to the increased opportunity for migrant construction workers to engage in social interactions, such as communicating with family members and colleagues, when faced with lighter workloads and reduced stress levels. This finding contradicts the results of Lazarus [56], who suggested that individuals rely more on their own beliefs and values in low-pressure situations.

These findings provide a nuanced understanding of how WP shapes the mechanisms through which SS influences IAVET, addressing a critical gap in the literature by demonstrating the moderating role of WP in the SS-IAVET relationship. They also offer valuable directions for future research to further explore this area. For instance, future research could examine how different types of WP influence the role of SS in shaping IAVET. These types may include physical stress, mental stress, and environmental stressors. Investigating these distinctions would help refine interventions and develop strategies that address the specific needs of workers in high-pressure environments. Additionally, comparative studies across different industries or regions could also help identify universal and context-specific factors influencing IAVET, further advancing the theoretical and practical understanding of this critical issue.

5.4. Theoretical Implications

This research significantly extends the literature on SS and VET by addressing a critical yet under-researched segment of the global construction workforce—Chinese migrant construction workers. By uncovering the underlying mechanisms influencing their willingness to engage in training, this study provides a robust theoretical foundation for developing targeted interventions tailored to this significant employee population. Furthermore, the study advances the application of the TPB in the VET field. Previous TPB-based studies in construction and training contexts, such as Zhao et al. [32], mainly investigated how internal psychological states, including job satisfaction and behavioral beliefs, influence workers’ professionalization behaviors within relatively stable and supportive organizational settings. Other applications of TPB in management and project environments, represented by Yuan et al. [20] and Zheng et al. [21], likewise concentrated on individual cognitive determinants, while paying limited attention to the broader social environment and structural constraints faced by migrant labor groups. In contrast, this study advances the TPB by integrating SS and WP as critical contextual factors, thereby extending the traditional TPB framework to better explain the behavioral intentions of migrant workers. This extension not only enriches the theoretical understanding of how intrinsic (e.g., attitudes, perceived behavioral control) and extrinsic (e.g., SS, WP) factors interact to shape training intentions but also provides a novel perspective on addressing ineffective VET and the skilled labor shortage in the construction industry. The extended TPB offers a more comprehensive theoretical framework for future research to explore and enhance individuals’ training intentions in similar contexts, addressing global challenges in workforce development.

5.5. Practical Implications

The findings reported in this paper have significant practical implications. First, the results highlighted the need for new interventions to enhance SS. This includes tailoring VET incentive mechanisms to provide tangible rewards to participants based on their training duration and effectiveness, and promoting a diversified qualification system to enable enterprises to conduct qualification verification for career progression and salary adjustments across a broader segment of the construction workforce. Second, SN plays a crucial role in the mediation model, highlighting the need to implement targeted strategies to cultivate a robust workplace training culture and environment. Both government and social media should intensify efforts to promote and educate migrant construction workers on skills training, fostering a cultural environment that values not only VET but also the construction workforce itself. To enhance the PBC, construction enterprises should offer flexible scheduling for migrant construction workers and provide diverse VET sources, such as videos, online courses, and VR-based training activities, to facilitate their training processes [17]. Moreover, ATT also demonstrates a mediating role, indicating that enterprises should effectively communicate their benefits and integrate training objectives into career development plans to improve migrant construction workers’ attitudes towards VET. Third, WP was identified as a critical moderator for influencing VET participation through SS activities. Hence, for migrant construction workers under high stress levels, particularly during periods of accelerated schedules, the emphasis should shift from skills training and education to mental health support. This approach can alleviate stress and, in turn, indirectly enhance VET participation by ensuring that migrant workers are better prepared to engage in training programs.

6. Conclusions and Limitations

Existing research has identified critical factors influencing migrant construction workers’ intention to attend vocational education and training. However, the underlying mechanisms linking social support, planned behavioral factors, and work pressures to migrant construction workers’ IAVET remain underexplored, particularly within the context of the Chinese construction industry. Through a questionnaire survey of 547 migrant construction workers in the Chinese construction industry, together with descriptive and SEM analyses, this research establishes a multiple mediation model of migrant construction workers’ IAVET based on TPB. The key findings are as follows: (1) SS significantly influences migrant construction workers’ IAVET; (2) the three PBFs exhibit significant mediating effects on the correlation between SS and IAVET, with SN playing the most pivotal role; and (3) WP moderates the mediating effect of PBFs on the relationship between SS and IAVET. In high-pressure scenarios, SS does not significantly directly correlate with IAVET but exerts its influence through the mediating effect of PBFs. Conversely, in low-pressure contexts, SS significantly influences IAVET, irrespective of the involvement of PBFs in the mediation process.

These findings offer several policy implications for improving VET systems. First, the strong SS → SN → IAVET pathway suggests that governmental agencies and enterprises should actively cultivate supportive social norms around VET participation. This can be achieved by publicizing successful training cases, strengthening peer advocacy, and incorporating VET engagement into team-level evaluations. Second, because PBC significantly shapes participation intentions, policymakers and organizations should reduce structural barriers such as time constraints and financial burdens through flexible training schedules, subsidized programs, and targeted financial support. Third, considering that WP weakens the positive effects of SS and PBFs, project-level management should adopt workload optimization, shift planning, and psychosocial support interventions to ensure that workers have sufficient resources to engage in VET. Collectively, these strategies can enhance migrant workers’ training motivation and strengthen the overall effectiveness of VET systems in the construction industry. Despite the contributions, this study has some limitations. First, while the sample was drawn from Nantong, a city with a diverse migrant construction workforce, and several measures were implemented to enhance sample representativeness (e.g., systematic sampling across diverse project types and scales), the findings may not fully generalize to other countries with different cultural, economic, and social contexts. This limitation indicates that the external validity of the conclusions should be interpreted with caution, and future research is encouraged to examine migrant construction workers in other regions or countries to assess cross-cultural applicability. Second, while this study incorporated WP and SS as two primary factors influencing workers’ IAVET, other contextual factors may play a role in different environments. Future studies should, based on the specific contexts of individuals, organizations, or countries, integrate necessary factors (e.g., job autonomy, leadership styles, and regulatory framework) to provide a more comprehensive understanding of the mechanisms driving IAVET. Third, the reliance on cross-sectional data limits the ability to capture dynamic changes over time. A longitudinal approach, utilizing repeated measures or panel data, is recommended to examine the long-term effects of SS and WP on IAVET and to identify causal relationships.

In summary, this study makes an original contribution by focusing on an overlooked yet critically important labor group—migrant construction workers. It further advances current knowledge by revealing how SS and WP jointly shape their intentions to participate in VET. By integrating these contextual factors into the TPB, the study extends the conventional TPB framework beyond individual cognition to incorporate the broader social and structural conditions influencing behavioral intentions in resource-constrained environments. This theoretically enriched model offers a more comprehensive explanation of VET participation among vulnerable labor groups and provides a foundation for future research seeking to refine TPB in similar contexts.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, investigation M.C. and L.Z. (Lili Zhang); investigation, data curation, writing—original draft, J.D.; resources, data curation, S.L. and M.S.; writing—review and editing, L.Z. (Lilin Zhao) and J.C.; visualization, J.C.; supervision, L.Z. (Lilin Zhao) All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Jiangsu Provincial University Philosophy and Social Science Research Project 2023SJYB1681, Postgraduate Research & Practice Innovation Program of Jiangsu Province KYCX243631, and Jiangsu Provincial University Philosophy and Social Science Research Project 20245T320731.

Data Availability Statement

Some or all data, models, or code generated or used during the study are available from the corresponding authors by request.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their sincere gratitude to the participants for sharing their experiences and insights in this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| VET | Vocational education and training |

| IAVET | Intentions to attend VET |

| TPB | Theory of planned behavior |

| SS | Social support |

| WP | Work pressure |

| PBFs | Perceived behavioral factors |

| ROs | Research objectives |

| ATT | Attitudes |

| SN | Subjective norms |

| PBC | perceived behavioral control |

| EFA | Exploratory factor analysis |

| KMO | Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin |

| CFA | Confirmatory factor analysis |

| SEM | Structural equation modeling |

| Z | Critical ratios |

| CI | Confidence interval |

| CA | Composite reliability |

| CR | Cronbach’s alpha |

| AVE | Average variance extracted |

| RMSEA | Root mean square error of approximation |

| RMR | Root mean square residual |

| AGFI | Adjusted goodness-of-fit index |

| GFI | Goodness-of-fit index |

| IFI | Incremental fit index |

| TLI | Tucker–Lewis index |

| CFI | Comparative fit index |

| S.E. | Standard error |

| C.R. | Critical ratio |

References

- Juricic, B.B.; Galic, M.; Marenjak, S. Review of the construction and shortages in the EU. Buildings 2021, 11, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johari, S.; Jha, K.N. Challenges of attracting construction workers to skill development and training programmes. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2020, 27, 321–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Association of General Contractors of America. Eighty Percent of Contractors Report Difficulty Finding Qualified Craft Workers to Hire as Association Calls for Measures to Rebuild Workforce. 2018. Available online: https://www.agc.org/news/2018/08/29/eighty-percent-contractors-report-difficulty-finding-qualified-craft-workers-hire (accessed on 23 February 2025).

- Winterbotham, M.; Vivian, D.; Kik, G.; Hewitt, J.H.; Tweddle, M.; Downing, C.; Thomson, D.; Morrice, N.; Stroud, S. Employer Skills Survey 2017; IFF Research Ltd.: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Du, Q.; Zhou, J.; Pan, T.; Sun, Q.; Wu, M. Relationship of carbon emissions and economic growth in China’s construction industry. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 220, 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Chang, S.; Castro-Lacouture, D. Dynamic modeling for analyzing impacts of skilled labor shortage on construction project management. J. Manag. Eng. 2020, 36, 04019035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalejaiye, P.O. Addressing shortage of skilled technical workers in the USA: A glimpse for training service providers. Future Bus. J. 2023, 9, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, Y.; Bian, J. Systematic training to improve the transformation of migrant workers into industrial workers within the construction sector in China. Buildings 2023, 13, 1948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Ye, J.; Zhong, Y.; Chen, Z. Digital transformation in the Chinese construction industry: Status, barriers, and impact. Buildings 2023, 13, 1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yap, J.B.H.; Chow, I.N.; Shavarebi, K. Criticality of construction industry problems in developing countries: Analyzing Malaysian projects. J. Manag. Eng. 2019, 35, 04019020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, S.; Hon, C.K.; Chan, A.P.; Jiang, X.; Skitmore, M. Critical factors affecting the safety communication of ethnic minority construction workers. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2023, 149, 04022173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, F.; Contreras, M.; Nussbaum, M.; Paredes, R.; Gelerstein, D.; Alvares, D.; Chiuminatto, P. Developing critical thinking in technical and vocational education and training. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chankseliani, M.; Keep, E.; Wilde, S. People and Policy: A Comparative Study of Apprenticeship Across Eight National Contexts; WISE Research: Doha, Qatar, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Pilz, M. Typologies in comparative vocational education: Existing models and a new approach. Vocat. Learn. 2016, 9, 295–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Schmidtke, C.; Jin, X. Chinese technical and vocational education and training, skill formation, and national development: A systematic review of educational policies. Vocat. Technol. Educ. 2024, 1, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wang, X.; Huang, Y. Chinese construction worker reluctance toward vocational skill training. J. Eng. Des. Technol. 2019, 17, 155–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, X.; Li, T.; Zhou, Y. Virtual reality’s influence on construction workers’ willingness to participate in safety education and training in China. J. Manag. Eng. 2022, 38, 04021095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Sunindijo, R.Y.; Frimpong, S.; Su, Z. Work stressors, coping strategies, and poor mental health in the Chinese construction industry. Saf. Sci. 2023, 159, 106039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haiyan, G.; Peng, W.; Tam, T. Chinese social value change and its relevant factors: An age-period-cohort effect analysis. J. Chin. Sociol. 2024, 11, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, H.; Wu, H.; Zuo, J. Understanding factors influencing project managers’ behavioral intentions to reduce waste in construction projects. J. Manag. Eng. 2018, 34, 04018031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Lu, Y.; Le, Y.; Li, Y.; Fang, J. Formation of interorganizational relational behavior in megaprojects: Perspective of the extended theory of planned behavior. J. Manag. Eng. 2018, 34, 04017052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irfan, M.; Thaheem, M.J.; Gabriel, H.F.; Malik, M.S.A.; Nasir, A.R. Effect of stakeholder’s conflicts on project constraints: A tale of the construction industry. Int. J. Confl. Manag. 2019, 30, 538–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Murphy, L.A.; Fang, D.; Caban-Martinez, A.J. Influence of fatigue on construction workers’ physical and cognitive function. Occup. Med. 2015, 65, 245–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tobia, L.; Muselli, M.; Mastrangeli, G.; Cofini, V.; Di Marcello, G.; Necozione, S.; Fabiani, L. Assessing the physical and psychological well-being of construction workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: A prospective study in Italy. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2024, 66, 242–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mastrantonio, R.; Cofini, V.; Tobia, L.; Mastrangeli, G.; Guerriero, P.; Cipollone, C.; Fabiani, L. Assessing Occupational Chemical Risk Perception in Construction Workers: A Cross-Sectional Study. Sustainability 2025, 17, 3332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhlman, S.T.W.; Walch, E.; Bauer, K.N.; Glenn, A.D. Intention to enact and enactment of gatekeeper behaviors for suicide prevention: An application of the theory of planned behavior. Prev. Sci. 2017, 18, 704–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyndt, E.; Baert, H. Antecedents of employees’ involvement in work-related learning: A systematic review. Rev. Educ. Res. 2013, 83, 273–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. Perceived behavioural control, self-efficacy, locus of control, and the theory of planned behaviour. J. Appl. Psychol. 2002, 32, 665–683. [Google Scholar]

- Vamvaka, V.; Stoforos, C.; Palaskas, T.; Botsaris, C. Attitude toward entrepreneurship, perceived behavioral control, and entrepreneurial intention: Dimensionality, structural relationships, and gender differences. J. Innov. Entrep. 2020, 9, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, C.; Yi, T.; Naumann, S.E.; Dong, J. The influence of subjective norms and science identity on academic career intentions. High. Educ. 2023, 87, 1937–1956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galván-Mendoza, O. Environmental knowledge, perceived behavioral control, and employee green behavior in female employees of small and medium enterprises in Ensenada. Baja Calif. Environ. Psychol. 2022, 13, 1082306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, W.; Peng, P.; Liu, H.; Wang, S.; Liu, W. How job satisfaction affects professionalization behavior of new-generation construction workers: A model based on theory of planned behavior. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2025, 32, 2672–2696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S.; Wills, T.A. Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychol. Bull. 1985, 98, 310–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palaniappan, K.; Natarajan, R.; Dasgupta, C. Prevalence and risk factors for depression, anxiety and stress among foreign construction workers in Singapore–A cross-sectional study. Int. J. Constr. Manag. 2023, 23, 2479–2487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carley, L.A.; Haas, C.T.; Borcherding, J.G.; Goodrum, P.M. Experiences with multiskilling among non-union craft workers in US industrial construction projects. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2003, 10, 374–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooq, M.S. Modelling the significance of social support and entrepreneurial skills for determining entrepreneurial behaviour of individuals: A structural equation modelling approach. World J. Entrep. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2018, 14, 242–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pruett, M.; Shinnar, R.; Toney, B.; Llopis, F.; Fox, J. Explaining entrepreneurial intentions of university students: A cross-cultural study. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2009, 15, 571–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thoits, P.A. Mechanisms linking social ties and support to physical and mental health. J. Health Soc. Behav. 2011, 52, 145–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armitage, C.J.; Conner, M. Efficacy of the theory of planned behaviour: A meta-analytic review. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 2001, 40, 471–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doll, J.; Ajzen, I. Accessibility and stability of predictors in the theory of planned behavior. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1992, 63, 754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, W.; Jacobs, R.L. Influences of formal learning, personal learning orientation, and supportive learning environment on informal learning. Hum. Resour. Dev. Q. 2011, 22, 239–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurtz, G.M.; Williams, K.J. Attitudinal and motivational antecedents of participation in voluntary employee development activities. J. Appl. Psychol. 2009, 94, 635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, M.F.; Tung, P.J. Developing an extended theory of planned behavior model to predict consumers’ intention to visit green hotels. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2014, 36, 221–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Hsu, L.T.J.; Sheu, C. Application of the theory of planned behavior to green hotel choice: Testing the effect of environmental friendly activities. Tour. Manag. 2010, 31, 325–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Si, H.; Shi, J.; Tang, D.; Wu, G.; Lan, J. Understanding intention and behavior toward sustainable usage of bike sharing by extending the theory of planned behavior. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2020, 152, 104513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Lamb, S. International Comparisons of China’s Technical and Vocational Education and Training System; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Kurniawaty, K.; Ramly, M.; Ramlawati, R. The effect of work environment, stress, and job satisfaction on employee turnover intention. Manag. Sci. Lett. 2019, 9, 877–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S.E. Conservation of resources: A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. Am. Psychol. 1989, 44, 513–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saleem, M.S.; Isha, A.S.N.B.; Benson, C.; Awan, M.I.; Naji, G.M.A.; Yusop, Y.B. Analyzing the impact of psychological capital and work pressure on employee job engagement and safety behavior. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 1086843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Umer, W.; Yu, Y.; Afari, A.M.F. Quantifying the effect of mental stress on physical stress for construction tasks. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2022, 148, 04021204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Techera, U.; Hallowell, M.; Littlejohn, R.; Rajendran, S. Measuring and predicting fatigue in construction: Empirical field study. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2018, 144, 04018062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pooladvand, S.; Hasanzadeh, S. Neurophysiological evaluation of workers’ decision dynamics under time pressure and increased mental demand. Autom. Constr. 2022, 141, 104437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodanwala, T.C.; Santoso, D.S. The mediating role of job stress on the relationship between job satisfaction facets and turnover intention of the construction professionals. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2022, 29, 1777–1796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holden, S.; Sunindijo, R.Y. Technology, long work hours, and stress worsen work-life balance in the construction industry. Int. J. Integr. Eng. 2018, 10, 13–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarus, R.S. Psychological stress in the workplace. In Occupational Stress; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2020; pp. 3–14. [Google Scholar]

- Chandrasekaran, P.; Ganeshprabhu, P. A study on employee welfare measurement in construction industry in India. Int. J. Sci. Technol. Res. 2020, 9, 990–997. [Google Scholar]

- Gopalakrishnan, G.; Brindha, G. A study on employee welfare in construction industry. Int. J. Civ. Eng. Technol. 2017, 8, 7–12. [Google Scholar]

- Cammarata, M.; Scuderi, A.; Timpanaro, G.; Cascone, G. Factors influencing farmers’ intention to participate in the voluntary carbon market: An extended theory of planned behavior. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 369, 122367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, B.; Tang, T.; Kaspar, E.; Li, Y. Explaining citizens’ plastic reduction behavior with an extended theory of planned behavior model: An empirical study in Switzerland. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 358, 120869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Sunindijo, R.Y.; Loosemore, M. The influence of personal and workplace characteristics on the job stressors of design professionals in the Chinese construction industry. J. Manag. Eng. 2023, 39, 05023006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamardeen, I.; Sunindijo, R.Y. Personal characteristics moderate work stress in construction professionals. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2017, 143, 04017072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeo, D.; Ha, Y. Job satisfaction among blood center nurses based on the job crafting model: A mixed methods study. Asian Nurs. Res. 2024, 19, 96–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nantong Municipal Government. Nantong’s Construction Output Value Remained the Highest in the Province in 2023. 2024. Available online: https://www.nantong.gov.cn/ntsrmzf/tjsj3/content/c8ffaaf9-4af2-4b49-8d96-e4deda7b6dc5.html (accessed on 1 April 2025).

- Fan, Y.; Chen, J.; Shirkey, G.; John, R.; Wu, S.R.; Park, H.; Shao, C. Applications of structural equation modeling (SEM) in ecological studies: An updated review. Ecol. Process. 2016, 5, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chomeya, R.; Tayraukham, S.; Tongkhambanchong, S.; Saravitee, N. Sample size determination techniques for multivariate behavioral sciences research emphasizing SEM. J. Educ. Innov. 2024, 26, 438–447. [Google Scholar]

- Taherdoost, H.; Sahibuddin, S.; Jalaliyoon, N. Exploratory factor analysis; concepts and theory. Adv. Appl. Pure Math. 2022, 27, 375–382. [Google Scholar]

- Goni, M.D.; Naing, N.N.; Hasan, H.; Wan-Arfah, N.; Deris, Z.Z.; Arifin, W.N.; Hussin, T.M.A.R.; Abdulrahman, A.S.; Baaba, A.A.; Arshad, M.R. Development and validation of knowledge, attitude and practice questionnaire for prevention of respiratory tract infections among Malaysian Hajj pilgrims. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, N. Factor analysis as a tool for survey analysis. Am. J. Appl. Math. Stat. 2021, 9, 4–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigudla, J.; Maritz, J.E. Exploratory factor analysis of constructs used for investigating research uptake for public healthcare practice and policy in a resource-limited setting, South Africa. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2023, 23, 1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J. Multivariate Data Analysis; Pearson Education, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Marsh, H.W.; Guo, J.; Dicke, T.; Parker, P.D.; Craven, R.G. Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), exploratory structural equation modeling (ESEM), and Set-ESEM: Optimal balance between goodness of fit and parsimony. Multivar. Behav. Res. 2020, 55, 102–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Durdyev, S.; Mbachu, J. Key constraints to labour productivity in residential building projects: Evidence from Cambodia. Int. J. Constr. Manag. 2017, 18, 385–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Bowen, N.K.; Guo, S. Structural Equation Modeling; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Agler, R.; De Boeck, P. On the interpretation and use of mediation: Multiple perspectives on mediation analysis. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 293306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tibbe, T.D.; Montoya, A.K. Correcting the bias correction for the bootstrap confidence interval in mediation analysis. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 810258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dawson, J.F. Moderation in management research: What, why, when, and how. J. Bus. Psychol. 2014, 29, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguirre-Urreta, M.I.; Hu, J. Detecting common method bias: Performance of the Harman’s single-factor test. Data Base Adv. Inf. Syst. 2019, 50, 45–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, G.W.; Cooper-Thomas, H.D.; Lau, R.S.; Wang, L.C. Reporting reliability, convergent and discriminant validity with structural equation modeling: A review and best-practice recommendations. Asia Pac. J. Manag. 2023, 41, 745–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharif, S.P.; Mostafiz, I.; Guptan, V. A systematic review of structural equation modelling in nursing research. Nurse Res. 2023, 26, 28–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iacobucci, D. Structural equations modeling: Fit indices, sample size, and advanced topics. J. Consum. Psychol. 2010, 20, 90–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, G.W.; Wang, C. Current Approaches for Assessing Convergent and Discriminant Validity with SEM: Issues and Solutions; Academy of Management Proceedings: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Xiong, B.M.; Skitmore, B.; Xia, M.A.; Masrom, M.A.; Ye, K.; Bridge, A. Examining the influence of participant performance factors on contractor satisfaction: A structural equation model. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2014, 32, 482–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khayru, R.; Nichen, K.N.; Chairunnas, A.; Safaruddin, S.; Tahir, M. Study on the relationship between social support and entrepreneurship intention experienced by adolescents. J. Soc. Sci. Stud. JOS3 2021, 1, 47–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costin, A.; Roman, A.F.; Balica, R.S. Remote work burnout, professional job stress, and employee emotional exhaustion during the COVID-19 pandemic. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1193854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deep, S.; Sonkar, N.; Yadav, P.; Vishnoi, S.; Bhoola, V.; Kumar, A. Factors influencing the mental health of White-Collar construction workers in developing economies: Analytical study during the COVID-19 pandemic in India. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2024, 150, 04024058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Wang, Q.; Wu, G.; Zheng, J.; Li, L. How family-supportive supervisor affect Chinese construction workers’ work-family conflict and turnover intention: Investigating the moderating role of work and family identity salience. Constr. Manag. Econ. 2020, 38, 807–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Salgado, C.; Camacho-Vega, J.C.; Gómez-Salgado, J.; García-Iglesias, J.J.; Fagundo-Rivera, J.; Allande-Cussó, R.; Pereira-Martin, J.; Ruiz-Frutos, C. Stress, fear, and anxiety among construction workers: A systematic review. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1226914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Q.; Palmer, N.A. Migrant workers’ community in China: Relationships among social networks, life satisfaction and political participation. Psychosoc. Interv. 2011, 20, 281–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, F.Y.Y.; Dulaimi, M.F.; Chua, M. Strategies for managing migrant construction workers from China, India, and the Philippines. J. Prof. Issues Eng. Educ. Pract. 2013, 139, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, M.Y.; Liang, Q.; Olomolaiye, P. Impact of job stressors and stress on the safety behavior and accidents of construction workers. J. Manag. Eng. 2016, 32, 04015019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Ren, T.; Liu, T. Training, skill-upgrading and settlement intention of migrants: Evidence from China. Urban Stud. 2019, 56, 2779–2801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, P.K.H.; Mak, W.W.S. Help-seeking for mental health problems among Chinese: The application and extension of the theory of planned behavior. Soc. Psychiat. Epidemiol. 2009, 44, 675–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Yang, S.; Lehto, X. Adoption of mobile technologies for Chinese consumers. J. Electron. Commer. Res. 2007, 8, 196–206. [Google Scholar]

- Mao, E.; Palvia, P. Testing an extended model of IT acceptance in the Chinese cultural context. SIGMIS Database 2006, 37, 20–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Froehlich, D.E.; Raemdonck, I.; Beausaert, S. Resources to increase older workers’ motivation and intention to learn. Vocat. Learn. 2023, 16, 47–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]