Abstract

This article interrogates the theoretical articulations of the body–space nexus through the formulation of an alternative methodological framework. It advances the premise that body and space cannot be reduced to physical parameters or representational models; rather, they are continually reconstituted through experience, perception, cultural contexts, and relational processes. Against the backdrop of fragmented spatial, phenomenological, and socio-political readings of space, Joseph Kosuth’s “One and Three Chairs” [1965] is posited as a conceptual compass, while semiotic instruments are mobilized as analytical devices. Within this constellation, the body–space relation is examined through a trialectical configuration that couples three relational modalities—distance, togetherness, and plurality—with three representational dimensions: object, image, and definition. The analysis shows how each modality delineates a distinct regime of bodily–spatial interaction and exposes the ways in which these regimes become manifest within architectural experience, social production, and conceptual potential. Within this framework, the notion of the flesh of space is advanced to describe space as a relational field in which bodies, materials, images, and definitions become mutually entangled. The principal contribution of this study lies in advancing a methodological orientation that transcends normative metrics and reductionist representational paradigms, thereby enabling body–space relations to be apprehended through relational dynamics and multilayered processes of signification. In doing so, this article provides a critical ground for rethinking architectural epistemology from a more flexible, experiential, and plural perspective, and proposes a transferable analytical scaffold for future case-based and design-oriented research.

1. Introduction

1.1. Body–Space in Architectural Discourse: Literature Overview

In architectural discourse, approaches to the relationship between body and space have been conceptualized along four main dimensions: spatial [measure, proportion, form], perceptual [sensation, atmosphere, image], phenomenological [body, lived experience, ontology], and social [practice, power, representation]. In the absence of a shared frame of reference, this diversity makes it difficult to trace transitions between concepts or conduct comparable readings and creates ambiguity about which problematics and principles should orient the discussion. This article responds to this situation by proposing an integrative analytical framework that brings these dimensions together within a single context and aligns them with semiotic levels of analysis. The point of departure is to render these qualities visible in relation to one another through explicit principles and to prepare the ground for the trialectic model developed in the following section, which seeks to gather fragmented readings of the body–space relation into a more coherent framework.

Historically, the relationship between body and space in architectural discourse has been repeatedly reconfigured through successive epistemological ruptures and shifting theoretical orientations. In antiquity, space was primarily conceived as a fixed and geometric entity, while the body functioned as the measure that endowed such order with proportion. Vitruvius’ principles of “proportion” in “De Architectura” demonstrate how architectural space was constructed through the geometrical criteria of the human body [1]. This Vitruvian paradigm was revisualized during the Renaissance in Leonardo da Vinci’s “Vitruvian Man”, where the human figure came to embody the universal model of architectural design. In this epistemic constellation, the body emerged not merely as a biological entity but as the idealized measure of spatial order.

The modern period extended this anthropometric trajectory through Le Corbusier’s Modulor system, which codified the human body as a universal metric and redefined space in terms of standardization and functional rationality. Within this formulation, the body was positioned as the source of proportion, while space was famously articulated as a machine for living in [2]. Yet such a conception subordinated the singularity of bodily experience, reducing space to an abstract and functionalized framework. The reconceptualization of architecture as a mechanistic system, rather than as a multisensory domain of experience, became a central point of critique directed at modernism. By the mid-twentieth century, as challenges to the modernist paradigm intensified, Colomina’s “Privacy and Publicity” revealed how modernist architecture systematically marginalized the body, situating the subject simultaneously as surveillant and surveilled within a regime of vision [3]. In canonical examples such as the Farnsworth House or the “Unité d’Habitation”, spatial order was constructed through ideals of transparency and regularity, while the sensory presence of the body was displaced. This underscored how modernist architecture privileged representation over lived experience.

Phenomenology constituted one of the most decisive theoretical interventions against these reductionist tendencies. For Husserl [4], space is not merely a geometric object but something continuously reconstituted through experience. It appears within perception, in the orientations we establish with our bodies, and in our habitual patterns of movement and use [4]. Merleau-Ponty’s definition of the body as both perceiving and perceived is likewise crucial [5]. For him, the body relates to space less through measure than through touching, seeing, hearing, and moving, that is, through sensory–motor practices, such that space emerges not as a fixed form but as an order continually reconstructed in and through action. Heidegger translates this line of thought into everyday life. Space gains meaning through tools, tasks, and practices of dwelling; relations become legible not at the level of representation or abstract measure, but in performances embedded in use [6]. As a result, space appears as a field of experience organized by bodily perception and action, repeatedly constituted within patterns of use. Norberg-Schulz extended phenomenology into architectural theory with the concept of “genius loci”, conceiving space not as a neutral backdrop but as the ontological medium through which human beings find rootedness, belonging, and existential orientation [7]. Architecture, in this light, provides not only physical shelter but also grounds for existential dwelling. In a similar trajectory, Pallasmaa’s “The Eyes of the Skin” mounted a critique of the ocularcentrism of modern architecture, insisting on the multisensory nature of architectural experience. For Pallasmaa, space attains significance through the interplay of touch, smell, hearing, and bodily orientation, whereby the body functions as the constitutive agent of architecture rather than as a passive occupant [8]. Leatherbarrow’s “Surface Architecture” complements this view by arguing that space affects the body not only through volumetric presence but also through the continuity of surfaces, their interaction with light, and their perceptual density [9]. Phenomenology, therefore, grounds architecture in an embodied and multisensory mode, reconfiguring space as an inseparable dimension of lived experience rather than an abstract formal order.

The trajectory opened by phenomenology was further deepened by social and political readings. In “The Production of Space”, Lefebvre conceptualized space not merely as a physical form or geometric configuration but as a domain in which social relations are produced and continuously redefined [10]. His triadic schema of perceived–conceived–lived space shows that space is constituted simultaneously through everyday bodily movements and practices and through social images, representations, and regulatory mechanisms of power. In this sense, the body is not a passive inhabitant of space but an active agent that transforms space within its social context. Lefebvre’s intervention was subsequently expanded by Soja, who advanced the notion of Thirdspace as a hybrid, plural, and contradictory assemblage of spatial experiences beyond binary oppositions [11]. Space thus emerges as a dynamic field at the intersection of physical, mental, and experiential dimensions.

Foucault further intervened in this discourse through his notion of heterotopia, showing how space is shaped by social power relations and how different bodies are positioned within such regulatory regimes [12]. Heterotopic sites such as hospitals, prisons, and cemeteries operate as counter-spaces that function outside normative orders while remaining in constant tension with them. These examples demonstrate that space is not a neutral container but a concrete milieu where power and disciplinary practices are made manifest. Rajchman advanced the discussion with his conception of topological space, which displaces the emphasis on fixed forms and foregrounds relations, foldings, and continuities [13]. Similarly, Anderson and Harrison, in “Taking-Place: Non-Representational Theories”, argued that space cannot be accounted for through representational schemas but must be understood as an inherently mobile, fluid, and performative process, ceaselessly constituted through emergence and encounters [14]. From phenomenology to social and political theory, these readings show that space is not a stable entity of representation but is continually produced through practices, encounters, power relations, and plural experiences.

In late modernity, the proliferation of speed, information flows, and representations radically reconfigured the body–space relation. Virilio’s concept of the overexposed city revealed how technological acceleration fragmented urban experience; the saturation of visual information and technological mediation weakened the body’s capacity for direct spatial experience, reducing space to an accumulation of surfaces subjected to perpetual exposure and consumption [15]. Harvey’s notion of time–space compression demonstrated how capitalist processes of production and circulation reorganize spatial experience by privileging the contraction of time and the annihilation of distance [16]. Bauman, through the concept of liquid modernity, extended this condition to the sphere of social life, arguing that body and space are no longer apprehended through stable forms but through fluidities that incessantly dissolve and reconfigure [17]. Baudrillard’s theory of simulacra and simulation further shifted the debate, positing that space is no longer anchored in material reality but is reproduced through representational systems, generating a condition of hyperreality in which spatial experience is determined less by material presence than by images and symbolic constructions [18]. Collectively, these readings suggest that, in the postmodern condition, space is experienced less through continuity than through transformation, less through stability than through flux, and less through material reality than through proliferating representational regimes.

At the intersection of body–space research, cognitive science, and environmental psychology, the literature converges on a view of space as an action and experience-oriented field rather than a static container. Drawing on the ecological notion of affordances, the environment is understood as a landscape of legible action possibilities: steps, door handles, buttons, and wayfinding devices appear not merely as objects but as invitations to move, grasp, and orient oneself in specific ways [19,20]. Cognition is thereby recast as a dynamic process emerging from the continuous coupling of body and environment, in which oriented actions and spatial cues provide the scaffolding that sustains perceptual continuity; the body reads space even as space configures and guides bodily conduct [21,22,23]. Atmospheric and enactive approaches extend this line of thought by emphasizing, on the one hand, that light, material, proportion, sound, and detail form a relational composition that shapes modes of being in space [24,25], and, on the other hand, that space itself is a dynamic field of becoming co-constituted through bodily participation, where meaning is continuously produced through being there, moving, orienting, and acting with others; enactive architectural interventions thus seek to transform space from a static and objectified environment into a mutable process animated by embodied existence [26]. Within the domain of digital culture, these dynamics are further intensified, as contemporary visual and representational environments, exemplified by platforms such as Instagram, reconfigure spatial perception and show that the body–space relation is simultaneously reconstituted across temporal, representational, and performative dimensions; through digital representations, space acquires a plural reality generated by images, aesthetic preferences, and the circulation of experiential fragments across social media, and is reproduced beyond its material presence as a second-order construct within visual culture and digital networks [27].

Contemporary studies thus demonstrate that the body–space relation can no longer be explained by static measures or reductionist representations; rather, it is continuously reconstituted across experience, perception, cultural practices, power relations, digital representations, and cognitive processes. Taken together, however, the literature presents a powerful yet fragmented picture, which points to a distinct research gap. Although readings of body–space proceed along certain axes, these axes are not consistently brought together within a single, coherent context. Because it remains unclear under which conditions transitions between these axes are to be considered valid and on what forms of evidence they should rest, comparisons fail to gain traceability. As a result, digitally mediated plural layers of meaning cannot be systematically articulated to existing frameworks. The outcome is the absence of an integrative mode of reading that operates with a shared reference system, common terminology, and explicit principles. This gap indicates the need for a framework with clearly articulated principles that can activate multiple lines of reading within the same context, one that does not rely solely on form/proportion or isolated phenomenological accounts but instead mobilizes semiotic levels simultaneously and can be translated into an operational method in the subsequent section. Building on this multilayered literature [Table 1], the next section sets out the trialectic and semiotic analytical model in procedural terms, outlining how it will be used to examine the relational dynamics of body–space.

Table 1.

Classification of key references on concept of body and space.

1.2. Research Aims and Questions

The primary aim of this research is to extend spatial theory and to reframe the relationality of body and space within contemporary theoretical debates by reconsidering it through multilayered representational dimensions. This aim responds to the gap that arises from the fact that, within architectural discourse, space has been conceptualized in a fragmented manner across spatial, perceptual, phenomenological, and social dimensions. In this respect, the study links the selected literature to its methodological framework by rendering the spatial, perceptual, formal, phenomenological, and social qualities of the body–space relation visible and explicitly framed. The body–space relation is read along three relational modalities [distance, togetherness, plurality], at three representational dimensions [object, image, definition], and through the triadic distinction of semiotics [syntactic, semantic, pragmatic]. Through these trialectic frameworks, fragmented accounts become comparable within a single context; historical continuities and ruptures can be traced, and contemporary plural theories can be analyzed within a shared frame of reference. The multilayered framework thus advanced aims both to reinterpret historical and theoretical accounts and to foreground the experiential and relational dimensions that are operative within contemporary design and research practices.

The central research questions and hypotheses can be formulated as follows:

- ▪

- How can the relationship between body and space be reframed through the simultaneous reading of different representational dimensions, when historical continuities and epistemological ruptures are taken into account?

Throughout history, space has either been reduced to geometry or defined as an object independent of the body. Such reductionist approaches prove insufficient to explain the experiential and cultural dimensions of embodiment today. An approach that considers the objective, experiential, and conceptual dimensions together enables a departure from one-dimensional accounts of body–space and instead offers a multilayered interpretive framework. This framework is instrumental both for understanding historical ruptures in discourse and for elucidating contemporary plural theories.

- ▪

- What methodological contributions are made possible by reframing the concepts of body and space for architectural research and design practice?

Existing research is often limited either to historical and theoretical analyses or to experimental design practices, and no method has yet been developed to read body–space relationality in a multilayered manner. A method grounded in multiple representational dimensions enriches the tools of critical analysis in architectural research, while enabling the development of experience-centered, participatory, and transformative approaches in design practice. In this way, a more relational and dynamic methodology can be established across both academic discourse and design processes.

1.3. Scope of Research

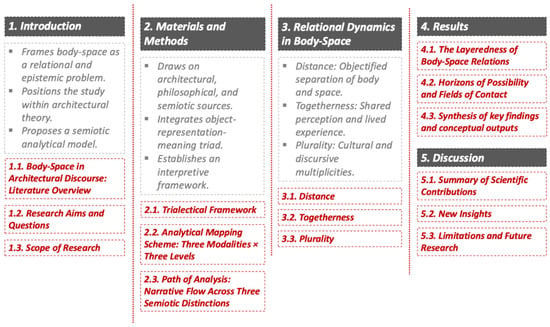

This article is structured into six main sections: Section 1—Introduction, Section 2—Materials and Methods, Section 3—Relational Dynamics in Body–Space, Section 4—Results, Section 5—Discussion and Section 6—Conclusion [Figure 1]. Section 1 outlines the historical and theoretical background of the body–space relation, makes visible the fragmented approaches in the literature, and sets out the research aims, questions, and hypotheses that guide the study. Section 2 presents a threefold analytical framework. This framework aligns Kosuth’s triad of object–image–definition with the syntactic–semantic–pragmatic levels of semiotics and with three relational modalities of the body–space relation [distance, togetherness, plurality]. This trialectic scheme is operationalized through an analytical mapping diagram and a narrative reading path that follow these three semiotic levels.

Figure 1.

Visual diagram outlining the research process.

Section 3 constitutes the theoretical core of the study and examines these three modalities as interconnected yet distinguishable axes for interpreting bodily–spatial encounters. It unfolds as three subsections, distance–togetherness–plurality, that trace shifts from geometric and normative separations to experiential co-presence and, finally, to social, cultural, and digital multiplicities. In doing so, it demonstrates how the proposed framework reconfigures dispersed debates on body–space into a comparative set of relational configurations. Section 4 presents the findings generated by correlating the modalities of distance–togetherness–plurality with Kosuth’s triadic model of representation. Methodologically, this section makes visible the multilayered structure of body–space relations, while theoretically it elaborates the concept of the flesh of space as the article’s original contribution.

Section 5 situates these findings within architectural epistemology, arguing that architecture cannot be reduced to a geometric, phenomenological, or representational domain, but should instead be understood as a dynamic discursive field in which relational, experiential, and plural processes of meaning-making are continuously produced. The section further evaluates the potential of the proposed analytical framework to enrich critical tools in architectural research while enabling experience-centered, participatory, and transformative methods in design practice. This article concludes by outlining its limitations and indicating directions for future research, particularly in relation to digital regimes of representation, embodied experience technologies, and the study of plural spatialities in diverse cultural contexts. Finally, Section 6 synthesizes the main findings and implications of the study.

2. Materials and Methods

The methodological approach of this study is grounded in a multilayered framework that enables the body–space relation to be examined not only as a physical arrangement or a set of spatial representations, but also as a conceptual, experiential, and relational field. This study adopts a qualitative, theoretically grounded research design. Rather than producing empirical measurements or user-based data, it develops a conceptual framework to reframe the body–space relation through a trialectical and semiotic lens. The approach is closer to conceptual and hermeneutic inquiry than to hypothesis-testing research: it constructs an interpretive model and uses it to reorganize and re-read existing architectural and philosophical discourses on body and space. In this sense, the paper proposes a methodological tool for analysis instead of a case-based evaluation of built environments.

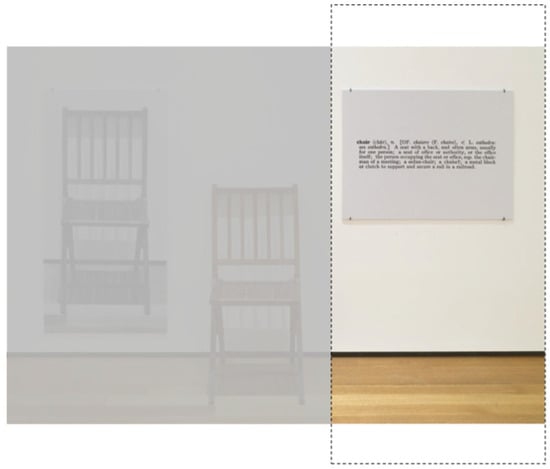

At the center of this axis lies the representational plurality exemplified in Kosuth’s “One and Three Chairs” [Figure 2]. The installation presents a chair in three distinct modalities: the chair itself [object], its photograph [visual image], and the dictionary definition of the word chair [linguistic representation]. This triadic structure renders visible the different modes of existence of a single entity across multiple layers, opening a space for interrogating their interrelations. Building upon this, the present study employs “One and Three Chairs” as a conceptual compass for analyzing the body–space relation across the dimensions of object, image, and definition. The physical presence of the chair is aligned with the material and measurable character of space; its photograph corresponds to the perceptual dimension of space; and its linguistic definition is related to experiential, social, cultural, and discursive contexts. Through this analogy, both body and space are re-envisioned not as fixed categories but as relational fields in which meanings are continuously constituted, transformed, and proliferated.

Figure 2.

“One and Three Chairs”, by Joseph Kosuth, 1965.

The study draws on the potentials of the representational structure proposed by Kosuth, while also employing semiotic tools to grasp the relations established between these layers. At this point, the tripartite distinction offered by semiotic theory enters as a set of conceptual instruments that support the analytical infrastructure. Semiotics is thus not deployed here as an autonomous method, but rather as a perspective that facilitates analytical reasoning in the examination of the body–space relation. In this way, this study reinterprets the body–space relation under three main headings and organizes them into a coherent narrative. The following subsections elaborate this framework by, first, setting out the triadic structures that organize the method; second, presenting the analytical mapping scheme that brings them into relation; and third, describing the narrative path of analysis through which the material is read across these intersecting levels.

The data of this research consist of canonical texts and concepts in architectural theory and related fields that explicitly address body–space relations. This set of texts was constructed through purposive sampling based on three main criteria: explicit discussion of the embodied subject and spatial experience, relevance to the epistemological ruptures, and their capacity to exemplify one of the three analytical axes of the model [distance, togetherness, plurality]. In addition to architectural theory, this set also includes selected works from philosophy, semiotics, and art theory in order to anchor the discussion of Kosuth’s “One and Three Chairs” within a broader interpretive field.

2.1. Trialectical Frameworks

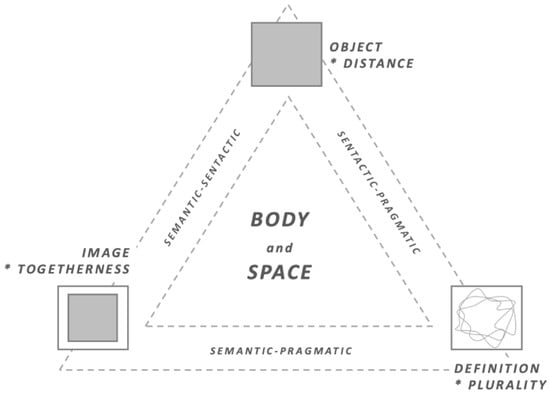

This study conceptualizes the body–space relation through three parallel triadic frameworks [Figure 3]:

Figure 3.

Trialectical frameworks.

- Representational dimensions [object–image–definition]: enables a single entity to appear simultaneously in three different modes of representation [material object, visual image, linguistic definition], thereby opening a plural field of reading that moves back and forth between these planes.

- Semiotic distinction [syntactic–semantic–pragmatic]: divides the process of meaning formation into three lines of reading: the syntactic level, which focuses on form and configuration; the semantic level, which foregrounds perception and processes of meaning-making; and the pragmatic level, which points to use, context, and performative consequences.

- Relational modalities [distance–togetherness–plurality]: organizes bodily–spatial encounters along three interpretive axes: distance, which emphasizes separation grounded in measure and form; togetherness, which describes perceptual and affective proximity; and plurality, which indicates relational patterns that proliferate through practices and discourses.

These triadic frameworks are aligned with one another in the analytical mapping scheme, which structures the study’s path of analysis.

2.2. Analytical Mapping Scheme: Three Modalities × Three Levels

In the second step, the triadic frameworks are operationalized through an analytical mapping scheme. This scheme aligns, on the one hand, the relational modalities [distance–togetherness–plurality] and, on the other, the semiotic distinction [syntactic–semantic–pragmatic] and the order of representation [object–image–definition]. In doing so, it renders the body–space relation readable through a single representational dispositif, across three modalities of relationality and three levels of meaning.

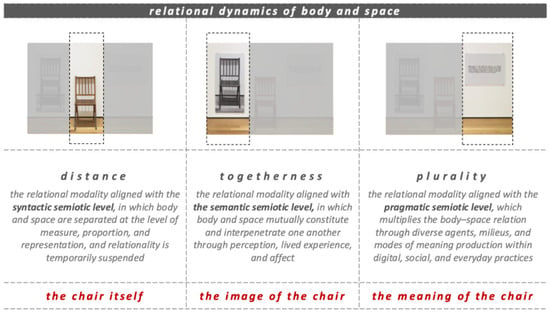

Although the proposed three modalities × three levels formula may at first suggest a matrix, the scheme does not aim to produce exhaustive cross-combinations; rather, it makes visible three triadic alignments placed side by side. Each triad pairs one relational modality with one semiotic level and one representational dimension from Kosuth’s “One and Three Chairs” [Figure 4]:

Figure 4.

Body–space relation through trialectical categories.

- ▪

- Distance—syntactic level—object [the chair itself];

- ▪

- Togetherness—semantic level—image [the photograph of the chair];

- ▪

- Plurality—pragmatic level—definition [the linguistic description of the chair].

The intention is that each triad should, in itself, offer a consistent line of reading of the body–space relation. This analytical mapping scheme provides the structural backbone for the path of analysis outlined in the next subsection.

2.3. Path of Analysis: Narrative Flow Across Three Semiotic Distinctions

Building on the mapping scheme outlined above, the trialectical–semiotic model was operationalized in three steps: grouping key discourses on body–space along the axes of distance, togetherness, and plurality; aligning these groups with the syntactic, semantic, and pragmatic levels; and constructing a narrative–interpretive reading by moving across this matrix. The study’s path of analysis is designed as a narrative reading that proceeds across the three semiotic levels. At the same time, the analysis is not conceived as a rigid linear scheme; rather, it is constructed as a qualitative reading woven with theoretical references, allowing for returns, overlaps, and cross-references. In this way, both the internal logic of the triadic frameworks and their transformation into narrative within the body of the text are made explicit. The narrative follows the sequence proposed by the analytical mapping scheme and unfolds in three successive strands, each corresponding to one relational modality:

- Syntactic level—Distance strand: in the first step, the body–space relation is read through measure, proportion, formal composition, axiality, constructed distance, and techniques of representation. The focus here is primarily on “the chair itself”, that is, on the objectified and distanced condition of space; in this configuration, the body appears mostly as an external reference point that observes, measures, and positions. From a semiotic perspective, this strand corresponds to the syntactic level, where what comes to the fore is not what the signs mean but the formal relations, ordering principles, and logic of configuration between them.

- Semantic level—Togetherness strand: in the second step, the analysis shifts toward perception, atmosphere, affect, association, and processes of meaning-making. Here, body and space are approached as a jointly constituted field of experience in which they coexist; through “the image of the chair”, the study traces how modes of representation are articulated to lived experience, memory, and cultural codes. This strand overlaps with the semantic level in semiotics, moving beyond formal arrangement to examine how images and spatial associations are interpreted by the body and gain experiential intensity.

- Pragmatic level—Plurality strand: in the final step, the body–space relation is examined in its multiple and negotiated manifestations within practices of use, institutional settings, digital interfaces, social discourses, and everyday habits. “The definition of the chair” is read here as a field of meaning that circulates among different actors and contexts, is rewritten, and proliferates. Semiotically, this strand corresponds to the pragmatic level; meaning is understood not as the property of a fixed sign system, but as a process that is continually reconstructed and negotiated through action, use, and discourse in varying contexts.

2.4. Methodological Evaluation and Limitations

As a conceptual and semiotic inquiry, this method has certain limitations that need to be acknowledged. First, the analysis is based on interpretive readings of selected texts rather than on empirical observations; this means that the findings remain at the level of re-organizing and re-articulating existing discourses. Second, although the trialectical–semiotic model operates as an explicit coding scheme, it remains open to different mappings and readings; other researchers may prefer to position the same authors or examples at different intersection points of the matrix. Finally, the paper does not apply the model to concrete architectural case studies; instead, it lays the groundwork for such applications. These limitations are consistent with the scope of the present study, yet they also point to clear directions for future empirical and design-oriented research.

3. Relational Dynamics in Body–Space

The relationship between body and space does not unfold on a fixed, singular, or static ground; it emerges within a layered, dynamic, and encounter-oriented field. This interactive domain is not confined to physical contact alone; it is equally interwoven with intellectual, sensory, and cultural dimensions [Figure 5]. The three subsections that follow enable a reconsideration of body–space relations both within the historical and theoretical contexts of architecture and through the lens of contemporary regimes of representation and experience. While each heading foregrounds a distinct aspect of spatial encounters, together they illuminate the permeability between the formal, perceptual, and discursive layers of architecture. In this regard, architecture is not solely the production of objective forms but also operates as a communicative act.

Figure 5.

Trialectical perspective in the relationality of body–space.

3.1. Distance

This section addresses an epistemological framework in which body and space are conceived as independent entities, or in which their relation is reduced solely to measures and proportions. Distance here signifies not only physical separation but also the mental, perceptual, and representational gaps between subject and space. In this mode, body and space encounter one another within a normative domain governed by rules, judgments, and regimes of representation. Within semiotic analysis, this context corresponds most directly to the syntactic level. The syntactic level concerns itself with the spatial, formal, and structural arrangement of signs; the positioning, order, and material relations among signs form its basis. The geometric organization of space, its role within a structural system, and its orientation of the body correspond precisely to the operations of the syntactic level [28]. Hence, the spatial organizations discussed under the category of distance may be analyzed through the syntactic ordering of signs.

In Kosuth’s conceptual installation “One and Three Chairs”, the chair is represented in its objective form [Figure 6]. By presenting a folding chair alongside its definition and photograph, the work stabilizes the triad of object–image–definition into a fixed structure of representation. Kosuth’s placement of the chair as object foregrounds its physical reality and spatial arrangement, thereby exemplifying a syntactic relation. Through its material presence, the object constitutes the first layer of the semiotic order: the physical and tangible [29]. Within this framework, body and space are likewise treated as fixed categories. Everything is transparent, determinate, and admits no other possibility. The chair is wooden, foldable, four-legged, without armrests; its characteristics are fully disclosed. Similarly, body and space are defined solely by their physical attributes and confined to a plane of standardization and uniformity. The syntactic level, with its focus on formal organization, finds its architectural parallel in the measurable, geometric comprehension of space, where the body functions as a unit of proportion and space as a static object, as in classical and modern paradigms.

Figure 6.

“One and Three Chairs”, by Joseph Kosuth, 1965 [The Chair Itself].

Behind this representational mode lies an understanding in which the body’s relation to space is constructed exclusively through proportion, geometry, and form. In architecture, this manifests as the arrangement of spatial components, analogous to the syntactic concatenation of signs. Sennett, in “The Body and the City”, observes that while in ancient Athens the body was associated with the aesthetics of nudity, in Roman culture this relation gave way to proportional, geometric, and representational models [30]. The Pantheon exemplifies this conception: its interior is symmetrically ordered, its geometric axes imposing a discipline over the body and producing a space of “see and obey”. This epistemic chain became institutionalized through Vitruvius’ proportional conception of space grounded in the human body. His famous schema in “De Architectura”, the “Vitruvian Man”, argued that space could be produced according to geometric norms by inscribing the human figure within a square and a circle. This normative framework gained prominence in the Renaissance through figures such as Francesco di Giorgio and Leonardo da Vinci [1,31]. For Boudon, the confinement of space to proportions and geometrical rules reduces architectural knowledge to a narrow and reductionist frame. He insists that architectural epistemology must apprehend space through experiential and cultural relations with the body, since space is not merely formal order but a medium through which knowledge and meaning are produced [32].

With Enlightenment and modernity, this representational paradigm shifted further, mechanizing the historical worlds of meaning of the body and reducing it to the measurable principles of biomechanics, anatomy, and physics. The body was thus redefined as a component of a functioning machine, severed from its autonomous experiential wholeness. In performance arts, this was reflected in Schlemmer’s Bauhaus stage designs, in which the body was choreographed with space as though within a mechanical order. In cinema, Lang’s “Metropolis” offered iconic images of mechanized bodies and spaces, both visualizing and critiquing this mentality [33]. In architecture, through his Modulor system, Le Corbusier universalized a Western, male-centered body as an absolute norm, imposing its measurements as a standard for spatial organization. As Şentürk notes, this system, by merging geometric transcendence, the golden ratio, and proportional norms, advanced a claim to universality while simultaneously suppressing the singularity of both body and space. Spaces thus produced were stripped of their experiential dimensions and reduced to visual objects for representation [34]. As de Botton emphasizes, however, space possesses not only functional but also emotional and experiential dimensions, layers largely neglected in modernist architecture [35]. Hence, works such as Le Corbusier’s Villa Savoye function less as responses to everyday needs and more as objects of representation and idealized visuality. One of the most incisive counter-critiques is found in Matta-Clark’s characterization of modernist architecture as a machine not to live in, radically questioning a paradigm that excludes human experience.

Within this syntactic regime, the body is no longer a creative subject that directs the impulses of design, but a unit of measure that adapts to design, regulates it, and defines its boundaries. Architectural production, akin to regulated systems that determine the arrangement of signs, constructs space through structural codes and compositional norms, reducing its existence to the visual expression of order. This perspective parallels Saussure’s classical semiotic conception, in which the signifier–signified relation is restricted to the external and formal level. Here, body and space are stripped of deeper meaning and function merely as elements in a syntactic chain [36]. In this mode of representation, form eclipses content. The tension between signifier and signified is reduced in favor of the former. Consequently, space is rendered as the orderly and harmonious composition of building elements, while the body is reduced to a measurable, standardized, and quantifiable entity.

In sum, the body–space relation established within the axis of distance and the syntactic level produces a regime of representation in which formal arrangement is privileged while experiential and semantic dimensions are excluded. As Kosuth’s installation demonstrates, such a regime reduces the body to a measurable and standardizable unit and space to a fixed and normative object of composition. Architectural discourse thereby displaces subjective experience and multilayered perception, anchoring itself instead within an epistemological framework dominated by order, proportion, and formal norms.

3.2. Togetherness

This axis addresses the relationality of body and space not as confined to physical or structural order, but as situated within a plane where meaning is produced, embodied, and integrated with perception. Togetherness here designates the moment of encounter, the condition of co-presence, and the co-construction of meaning. Body and space are no longer conceived as separate, stable entities but as mutually oriented, mutually constituted, and open to plural interpretations.

Within semiotic analysis, this corresponds to the semantic level, which discloses that signs are not exhausted by their formal arrangement but are also charged with contextual, perceptual, and experiential layers shaped according to the position of the subject. In Kosuth’s “One and Three Chairs”, the photographic image of the chair represents this dimension [Figure 7]. The photograph is not merely a visual depiction but a carrier of interpretive layers shaped by the photographer’s gaze, the play of light, and the framing of the image. Barthes’ notion of polysemy is operative here: the photograph is not only a chair but also the product of a gaze, a choice, a representation [37].

Figure 7.

“One and Three Chairs”, by Joseph Kosuth, 1965 [The Image of the Chair].

Semantic depth reveals that the body–space relation cannot be confined to physical arrangements but is shaped through bodily intentionality, perception, and lived experience. This intersects directly with phenomenology, wherein space is apprehended not merely as something measured or constructed but as something perceived, lived, and imbued with meaning through the presence of the body. Husserl’s method of phenomenological reduction posits that the essence of a phenomenon can be disclosed only through the orientation of the subject [38]. Accordingly, space is not an external object but a phenomenon constituted through the body’s directedness toward it. An architectural exemplar that materializes such bodily intentionality and perceptual intensity is Zumthor’s Therme Vals. Here, architecture does not merely consist of form and material but creates an atmosphere through warmth, stone texture, moisture, light, and silence that envelops the body. The relation is not one of measurement but of tactile and sensory co-presence. Likewise, Holl’s Chapel of St. Ignatius demonstrates how shifting light conditions do not simply orient the body but also endow spatial experience with layers of meaning. In this case, light is not merely a tool of architecture but an active participant in meaning-making, modulated by the subject’s positioning.

Merleau-Ponty’s concept of flesh deepens this dimension. For him, the body is not only perceiving but also perceived. The body’s experience of itself as touchable implies a reversibility: the toucher and the touched coincide within the same being. This reversibility reveals that the body is not only situated within space but also constituted as part of space. Likewise, space is not simply a stage upon which the body is placed but a relational entity that comes into being through movement, orientation, and sensation [5]. This co-presence is crystallized in Merleau-Ponty’s proposition that the world and the body are made of the same flesh. Flesh, simultaneously subjective and objective, inner and outer, material and incorporeal, discloses the ontological depth of the body–space relation [39].

Architectural thinkers such as Pallasmaa expand upon this sensorial ontology. For Pallasmaa, space first touches the skin before it reaches the intellect: to experience space is not merely to perceive it visually but to encounter it through touch, smell, hearing, and even taste, woven into a multilayered sensory fabric. Space thus ceases to be an abstract geometry or representational form and becomes a lived reality coextensive with the body. Exemplary in this regard are Kuma’s Asakusa Cultural Center, where the scent of wood, the play of shadows, and compressive ceiling heights configure a sensory field, and Ando’s Water Temple, where light, water, and silence create a meditative atmosphere. In these works, space is no longer an object but a living entity co-constituted by bodily sensation.

Thus, the axis of togetherness moves beyond the normative representations and formal orders discussed under distance and instead foregrounds a domain where meaning is generated, perception layered, and the body actively constitutes space. Here, the body functions not as a measurer but as a meaning-maker, and space exists not as a form but as an experienced, sensed presence. Architecture is thereby apprehended not as proportion and geometry alone, but as a series of events interpreted through the body’s sensory engagement. The semantic level thus discloses architecture not as a mere formal arrangement of signs but as charged with contextual, phenomenological, and experiential depth, highlighting the meaning-bearing nature of signs. Kosuth’s photographic chair image exemplifies this dimension: it not only depicts but also contextualizes, layering meaning through gaze, light, and framing. Hence, the semantic level reveals that the meaning of the body–space relation arises not from formal order alone but from bodily experience, perceptual intensity, and contextual processes of signification.

3.3. Plurality

Following the modalities of distance and togetherness, this section investigates the third dimension of the body–space relation, namely plurality, articulated at the pragmatic level. From a semiotic perspective, the pragmatic level concerns how signs function within contexts of use, how they affect subjects, and how they engage with social codes. In the analytical mapping scheme, plurality is aligned with the pragmatic level and the definition layer of Kosuth’s triad, shifting attention from built form and perception to the discursive, regulatory, and digital operations through which space is named, coded, and circulated. In this article, plurality denotes the pragmatic dimension of the body–space relation. It describes the ways in which spatial meanings are multiplied, debated, negotiated, and redistributed through practices of use, institutional codes, discourses, and digital representations. Unlike distance, which privileges formal order, and togetherness, which focuses on embodied perception, plurality foregrounds those interpretive shifts that occur when space is spoken about, regulated, shared, and recirculated across social and digital contexts.

Within this axis, the dictionary definition of the word chair in Kosuth’s “One and Three Chairs” points beyond the object’s physical or visual representation toward its potential semantic multiplicities within language, its uses, positions, authorities, historical resonances, and cultural contexts [Figure 8]. Such plurality also characterizes architecture, wherein space is not exhausted by formal organization or perceptual experience but is constituted through linguistic, social, and discursive practices. After foregrounding fixed representations under distance and layers of perception under togetherness, the axis of plurality turns toward the functions of speech, language, social rituals, digital interactions, and the cultural performances embedded in built form. Here, body and space cease to exist as stable objects, instead unfolding within an interactive field in which subject and object continually exchange roles.

Figure 8.

“One and Three Chairs”, by Joseph Kosuth, 1965 [The Definition of the Chair].

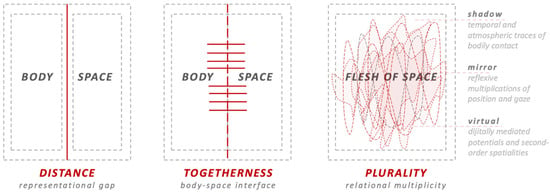

At this juncture, Deleuze’s concept of becoming comes into play [40]. Plurality is not the expression of fixed meanings or completed identities but of continuously differentiating, transitional, and dynamic processes. Becoming emphasizes that body and space never achieve a final identity but acquire meaning through shifting networks of relations. Thus, body and space emerge not only as coexisting entities but as co-becomings. Within this framework, the metaphor of the flesh of space is advanced to articulate the spatial counterpart of bodily experiential depth. The ontological resonance of Merleau-Ponty’s notion of flesh, elaborated in the discussion of togetherness, is now transposed onto space itself, which becomes perceptible, pluralized, generative, and transformative. In analytical terms, the flesh of space designates the interface at which perception, practice, and language intersect, making the pragmatic operations of space—coding, regulation, circulation—readable as extensions of embodied experience rather than as purely abstract constructs.

The alignment of this modality with the pragmatic level allows architecture to be conceived not as a closed object offering fixed meanings but, in Eco’s terms, as an open work, a surface upon which meaning is continuously produced through social interaction [41]. At this stage, architectural meaning arises not solely from the designer’s intention, nor exclusively from perception or experience, but through the collaboration of user interpretation, environmental conditions, historical memory, and digital codes. From this standpoint, the text expands from the word “chair” toward a constellation of concepts, virtual–shadow–mirror, each of which illuminates the fluid and continuously shifting multilayeredness of the body–space relation.

- Virtual—“Not physically existing as such but made to appear so; existing in essence though not in actual fact”.

The virtual is a domain neither fully material nor entirely abstract, intangible yet perceptible, comprising unrealized but effective possibilities. Deleuze defines the virtual as the real force of what has not yet actualized [42]: it is not a lack but a multiplicity of potentialities, with actuality as the realization of one among them. Thus, the boundary between the virtual and the real is not oppositional but interwoven and constantly redefined. As Žižek notes, the critical issue is not virtual reality but the reality of the virtual [43], its effects, and its consequences. Contemporary digital technologies, such as VR and AR tools, enable bodily and perceptual engagement with spaces not yet constructed [44]. Virtual spaces therefore frame architecture not as fixed structures but as continuously reproducible fields of becoming, where different bodies engender different meanings. In this sense, the virtual exemplifies plurality at the pragmatic level by showing how spatial meaning is continuously reconfigured through digitally mediated practices of viewing, sharing, and inhabiting.

- Shadow—“A dark area or shape produced by a body coming between rays of light and a surface”.

A shadow is not merely an optical trace but a temporal record of the body’s contact with space. As Zumthor highlights in “Atmospheres”, shadows shape the texture and spirit of space [24]. Pallasmaa similarly underscores that light–shadow dynamics are inseparable from bodily perception [8]. Shadows render visible the ambiguous, fluid, and temporal dimensions of this relation. In Tadao Ando’s Church of the Light, for instance, the sharp incision of light creating shadow defines the spiritual essence of the worship space, orienting the body’s axis and gestures not only visually but also corporeally. In this sense, shadows pluralize the body–space relation at the pragmatic level by inscribing temporal and atmospheric differences into the same spatial setting, allowing for multiple readings of the same architectural situation.

- Mirror—“A polished or smooth surface that forms images by reflection”.

Conceptually, the mirror symbolizes space’s capacity to represent and reproduce itself. The mirrored image is both real and illusory, revealing the reflexive dimension of body–space. Foucault’s theorization of heterotopia invokes the mirror as a placeless place that both exists and does not [45]. Architecturally, the mirror functions not merely to reflect but to multiply and disrupt perception; Philip Johnson’s Glass House embodies this principle, as transparency and reflection allow the body to be simultaneously inside and outside, producing plural readings. The mirror thus materializes plurality at the pragmatic level by multiplying viewpoints and destabilizing any single, authoritative image of space, making reflexive and conflicting readings part of the spatial experience itself.

Taken together, these conceptual articulations demonstrate that meaning at the pragmatic level is never fixed but continually renegotiated. Both body and space are constituted through invisible yet operative relations within a semiotic field. This is neither pure representation nor mere experience, but the process of meaning in becoming. Space thereby emerges not as a transcendental object but as a surface of becoming. Body and space become components of a shared flow that transforms and destabilizes boundaries. As Braidotti notes, nomadism does not mean the absence of limits but the non-fixity of limits [46]. Likewise, neither body nor space can be stabilized; they are experienced, altered, and multiplied together. This fluidity becomes manifest in projects such as Rahm’s Meteorological House, where architecture is constituted not by form but by perceptible variables such as heat, humidity, and airflow. Meaning here is shaped not by geometry or function but by plural bodily perceptions; what is welcoming to one user may be repulsive to another. Similarly, Scofidio + Renfro’s Blur Building dissolves architecture into a cloud of water vapor, a surface without form that only comes into being through bodily presence. Both examples reveal architecture as constituted not by fixed boundaries but by atmospheric, sensory, and corporeal flows, producing space as a domain of continuous becoming and plurality.

In conclusion, plurality marks both an epistemological and an ontological shift: architecture is reframed less as a domain of objectified knowledge and more as a field of meaning, less as form-production and more as a nexus of linguistic and social practices. The body here emerges not merely as an experiencer but as a speaking, coding, and rewriting subject. Kosuth’s triadic regime of object–image–definition is thus extended into architecture as a regime in which body and space intersect physically, perceptually, and discursively, generating meaning as a plural process of becoming. Methodologically, this axis clarifies when analyses of body–space move from formal or experiential readings into the domain of codes, practices, and representations, indicating the conditions under which pragmatic interpretations remain legitimate.

4. Results

4.1. The Layeredness of Body–Space Relations

The central finding of this study is that the relation between body and space cannot be grasped through single or reductionist planes. Instead, it can be systematically articulated through three modalities:

- Distance, which corresponds to the syntactic level, where the body is defined through measures and proportions and space is stabilized through normative arrangements.

- Togetherness, which corresponds to the semantic level, where bodily perception, phenomenological intensity, and sensory experience establish body and space as co-constructors of meaning.

- Plurality, which corresponds to the pragmatic level, where social, cultural, and linguistic codes generate horizons of meaning that are unstable, non-fixed, and continuously reproduced.

These three modalities were analyzed through Kosuth’s triad of object–image–definition, aligned with the semiotic distinctions of syntactic, semantic, and pragmatic levels, thereby forming a conceptual compass for the study. Consequently, body–space relations are interpreted not as linear sequences but as multilayered, dynamic, and transformable configurations.

4.2. Horizons of Possibility and Fields of Contact

This study also demonstrates that bodily–spatial encounters extend beyond physical and perceptual dimensions to encompass plural potentials articulated through concepts such as virtual, shadow, and mirror. These concepts disclose how space is continually re-produced across experiential, temporal, reflexive, and cultural dimensions.

Within this framework, the proposed notion of the flesh of space signifies not separate entities but an immanent field in which body and space exist through reciprocal orientation and contact. The flesh of space renders visible the permeability between subject and object and the simultaneity of divergent possibilities. Architecture thus appears not as constructed form or representational order but as a living, continuously transforming domain constituted through bodily experience, cultural practice, and semiotic multiplicity.

4.3. Synthesis of Key Findings and Conceptual Outputs

The original contribution of the findings can be summarized in three interrelated outputs. First, the trialectical framework reorganizes the body–space relation along the axes of distance, togetherness, and plurality and correlates these modalities with syntactic, semantic, and pragmatic levels of analysis. This configuration provides a single ordered field in which different theories and historical moments can be examined comparatively rather than as separate or incommensurable strands. Second, the analytical alignment of the three modalities with Kosuth’s triad of object, image, and definition introduces a concrete reading protocol. Instead of isolating architectural artifacts, spatial experiences, and discursive operations, the model positions them as corresponding layers within one relational structure, making it possible to trace how a shift in one level affects the others. Third, the study advances the notion of the “flesh of space” as a relational stratum in which bodily perception, spatial practice, and meaning production intersect. By naming this intermediate layer between body and space, the article specifies the locus at which different epistemological and phenomenological accounts converge, thereby delineating its distinctive conceptual output.

5. Discussion

This study reopens the question of the body–space relation within architectural epistemology, advancing an analytical framework that transcends normative criteria and reductionist representational regimes. The findings demonstrate that body and space are not merely measurable categories but relational dynamics continuously reconstituted through experience, perception, cultural practice, digital representation, and social context.

5.1. Summary of Scientific Contributions

The proposed approach offers scientific contributions by responding to specific gaps in the literature and by opening up usable tools for further research and design practice.

- Theoretical contribution: The study addresses the long-standing fragmentation between phenomenological, semiotic, and epistemological accounts of space. By situating distance–togetherness–plurality within a trialectical structure, it enables theories that typically speak in different registers, formal, experiential, and discursive, to be read within a shared scheme. This makes it possible to compare how different traditions conceptualize the body–space relation without reducing them to a single vocabulary.

- Methodological contribution: The model offers a structured procedure for reading architectural cases and texts through the combined lenses of modality [distance–togetherness–plurality], semiotic level [syntactic–semantic–pragmatic], and Kosuth’s object–image–definition relation. Researchers can employ this alignment as a step-by-step guide: identifying how a given work or discourse positions the body, how it frames space, and how these positions shift when analyzed through different levels of representation and meaning. In this sense, the framework functions as a transferable analytical scaffold that can be adapted to diverse typologies, media, and contexts.

- Practical contribution: For designers and practice-oriented researchers, the approach foregrounds how spatial configurations, atmospheres, and representational strategies co-produce bodily experience and plural meanings. By working with the articulated layers of the model, design processes can deliberately experiment with distancing and intensifying relations, with different modes of togetherness, or with multiple forms of plurality in digital and everyday environments. This opens a pathway for research-by-design and experience-centered inquiry that treats body–space relations not as a background assumption but as a central design problem.

5.2. New Insights

This study offers new insights into the body–space relation on three levels. First, the proposed trialectical framework shows that body and space cannot be understood on a single geometric, phenomenological, or social plane; rather, they must be read as a multilayered and comparable field of relationality by systematically aligning the modalities of distance–togetherness–plurality with the syntactic–semantic–pragmatic levels of analysis. In this way, formal, experiential, and discursive approaches, often positioned in the literature as mutually exclusive or incompatible, can be brought together within a shared order of representation and meaning. Second, the analysis reveals that these three modalities do not operate as isolated categories, but as tensioned and partially overlapping configurations between formal coherence and experiential diversity, perceptual togetherness and discursive/practical proliferation, and local context and digital circulation. Finally, at the intersection of these tensions, the proposed notion of the flesh of space does not reduce space either to phenomenological depth or to a purely discursive construct; instead, it defines a shared interface in which perception, practice, and language fold into one another, offering a new interpretive unit that enables architecture to be reconsidered beyond the production of objects and representations, in terms of relational multiplicity, experiential stratification, and semiotic density.

5.3. Limitations and Future Research

The insights developed in this study are, however, shaped by several limitations that also point to directions for future research. First, this study is based on a selected set of theoretical texts rather than empirical data; second, the model is not yet tested on concrete architectural cases. Nevertheless, this study offers new insights by showing that the body–space relation is more productively understood as a stratified and dynamic configuration than as a single, stable category. The framework demonstrates how formal differentiation, lived experience, and discursive production are intertwined rather than sequential; each modality of distance, togetherness, and plurality is always already inflected by syntactic, semantic, and pragmatic operations. This perspective reveals tensions that are often overlooked in architectural discourse: between formal coherence and experiential diversity, between sensory perception and institutional or technological codes, and between situated spatial practices and their circulation in digital and mediated environments. By drawing attention to these tensions, this article shifts the analytical focus from isolated objects or purely phenomenological accounts toward relational multiplicity and semiotic density as defining features of contemporary spatialities. Within this configuration, the notion of the flesh of space designates a shared interface where perception, practice, and language fold into one another. Treating this interface as the primary site of inquiry encourages future studies to investigate how specific spatial arrangements, narrative framings, and media ecologies shape the ways in which bodies inhabit, interpret, and transform space.

6. Conclusions

This paper set out to reframe the body–space relation in architecture through a trialectical and semiotic framework. By intersecting the axes of distance, togetherness, and plurality with syntactic, semantic, and pragmatic levels, this study proposes a model that makes visible how different architectural discourses construct, negotiate, and transform embodied spatial relations.

The analysis suggests four main conclusions. First, traditional geometric and object-centered approaches largely operate within the axis of distance and at the syntactic level, treating the body as a measurable unit and space as a neutral container. Second, phenomenological and experiential accounts move the focus towards togetherness and the semantic level, where body and space become mutually constitutive through perception and lived experience. Third, contemporary plural and more than human perspectives push the discussion towards the axis of plurality and the pragmatic level, where bodies, environments, and technologies form open ended assemblages rather than stable pairs. Fourth, Kosuth’s “One and Three Chairs” provides a model that allows these shifts between axes and levels to be read as systematic reconfigurations of object, image, and definition.

Conceptually, the main contribution of the paper is to articulate the body–space relation as a multilayered and transformative field rather than as a fixed binary of subject and object. Methodologically, the trialectical–semiotic model offers a reusable analytical tool that can be applied to different corpora of texts, drawings, or built environments, enabling researchers to map how particular practices or discourses move across axes and semiotic levels. For architectural and urban design practice, the framework foregrounds the importance of designing for relational, culturally situated, and evolving body–space configurations instead of merely optimizing geometric fit or functional efficiency.

Finally, the study’s limitations also point to concrete directions for future work. The framework can be further developed through detailed case studies of built projects in different cultural contexts, user-centered qualitative research on spatial experience, and experimental design investigations, including digital and mixed-reality environments. By translating the conceptual model into such empirical and design-oriented inquiries, the trialectical approach proposed here can evolve from a primarily interpretive tool into a generative protocol for both research and practice.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, investigation, resources, data curation, writing—original draft preparation, writing—review and editing, visualization, R.K.Y.; validation, formal analysis, supervision, project administration, funding acquisition, S.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

This article is derived from the master’s thesis conducted by the authors at Yıldız Technical University, and the framework developed there is here further expanded and elaborated on in relation to broader contexts.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Vitruvius. The Ten Books on Architecture; Morgan, M.H., Translator; Dover Publications: New York, NY, USA, 1960. [Google Scholar]

- Corbusier, L. Le Modulor; Éditions de l’Architecture d’Aujourd’hui: Paris, France, 1948. [Google Scholar]

- Colomina, B. Privacy and Publicity: Modern Architecture as Mass Media; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Husserl, E. The Crisis of European Sciences and Transcendental Phenomenology; Northwestern University Press: Evanston, IL, USA, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Merleau-Ponty, M. Phenomenology of Perception; Routledge: London, UK, 1962. [Google Scholar]

- Heidegger, M. Building, Dwelling, Thinking, in Poetry, Language, Thought; Harper & Row: New York, NY, USA, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Norberg-Schulz, C. Genius Loci: Towards a Phenomenology of Architecture; Rizzoli: New York, NY, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Pallasmaa, J. The Eyes of the Skin: Architecture and the Senses; Wiley: Chichester, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Leatherbarrow, D. Surface Architecture; Princeton Architectural Press: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Lefebvre, H. The Production of Space; Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Soja, E. Thirdspace: Journeys to Los Angeles and Other Real-and-Imagined Places; Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Foucault, M. Of Other Spaces. Diacritics 1986, 16, 22–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajchman, J. Constructions; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, B.; Harrison, P. (Eds.) Taking-Place: Non-Representational Theories and Geography; Ashgate: Aldershot, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Virilio, P. The Lost Dimension; Semiotext(e): New York, NY, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey, D. The Condition of Postmodernity; Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Bauman, Z. Liquid Modernity; Polity Press: Cambridge, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Baudrillard, J. Simulacra and Simulation; University of Michigan Press: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Gibson, J.J. The Ecological Approach to Visual Perception; Houghton Mifflin: Boston, MA, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Norman, D.A. The Psychology of Everyday Things; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Varela, F.; Thompson, E.; Rosch, E. The Embodied Mind: Cognitive Science and Human Experience; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Noë, A. Action in Perception; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher, S. How the Body Shapes the Mind; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Zumthor, P. Atmospheres: Architectural Environments—Surrounding Objects; Birkhäuser: Basel, Switzerland, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Böhme, G. Atmosphere: Essays on the New Aesthetics; Routledge: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Arteaga, A. An Enactive Approach to Architecture as Intervention. Dimens. J. Archit. Knowl. 2024, 4, 179–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagiri, F.; Wijaya, D.C.; Sitindjak, R.H.I. Embodied Spaces in Digital Times: Exploring the Role of Instagram in Shaping Temporal Dimensions and Perceptions of Architecture. Architecture 2024, 4, 948–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, C. Foundations of the Theory of Signs; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1938. [Google Scholar]

- Kosuth, J. Art After Philosophy and After: Collected Writings 1966–1990; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Sennett, R. Flesh and Stone: The Body and the City in Western Civilization; W.W. Norton: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Wittkower, R. Architectural Principles in the Age of Humanism; Academy Editions: London, UK, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Boudon, P. Sur L’espace Architectural: Essai D’épistémologie de L’architecture; Dunod: Paris, France, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Schlemmer, O. The Theatre of the Bauhaus; The Johns Hopkins University Press: Baltimore, MA, USA, 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Şentürk, L. Le Corbusier: Oransal Izgara’dan Modulor’a. Eskişeh. Osman. Üniv. Mühendis. Mimar. Fak. Derg. 2008, 21, 101–108. [Google Scholar]

- De Botton, A. The Architecture of Happiness; Pantheon Books: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- De Saussure, F. Course in General Linguistics; Philosophical Library: New York, NY, USA, 1916. [Google Scholar]

- Barthes, R. Image, Music, Text; Hill and Wang: New York, NY, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Husserl, E. Ideas Pertaining to a Pure Phenomenology and to a Phenomenological Philosophy; Martinus Nijhoff: Hague, The Netherlands, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Merleau-Ponty, M. The Visible and the Invisible; Northwestern University Press: Evanston, IL, USA, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Deleuze, G. Difference and Repetition; Columbia University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Eco, U. The Open Work; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Deleuze, G. Bergsonism; Zone Books: New York, NY, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Žižek, S. Organs Without Bodies: On Deleuze and Consequences; Routledge: London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Wagiri, K.; Zhao, Y.; Singh, M.K.; Tanaka, H. Virtual and Augmented Reality in Architectural Design: Bodily Experience and Spatial Perception. J. Archit. Comput. 2024, 32, 55–72. [Google Scholar]

- Foucault, M. Of Other Spaces: Heterotopias. In Architecture/Mouvement/Continuité; Société Française des Architects: Paris, France, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Braidotti, R. Nomadic Subjects: Embodiment and Sexual Difference in Contemporary Feminist Theory; Columbia University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).