Temperature Prediction of Mass Concrete During the Construction with a Deeply Optimized Intelligent Model

Abstract

1. Introduction

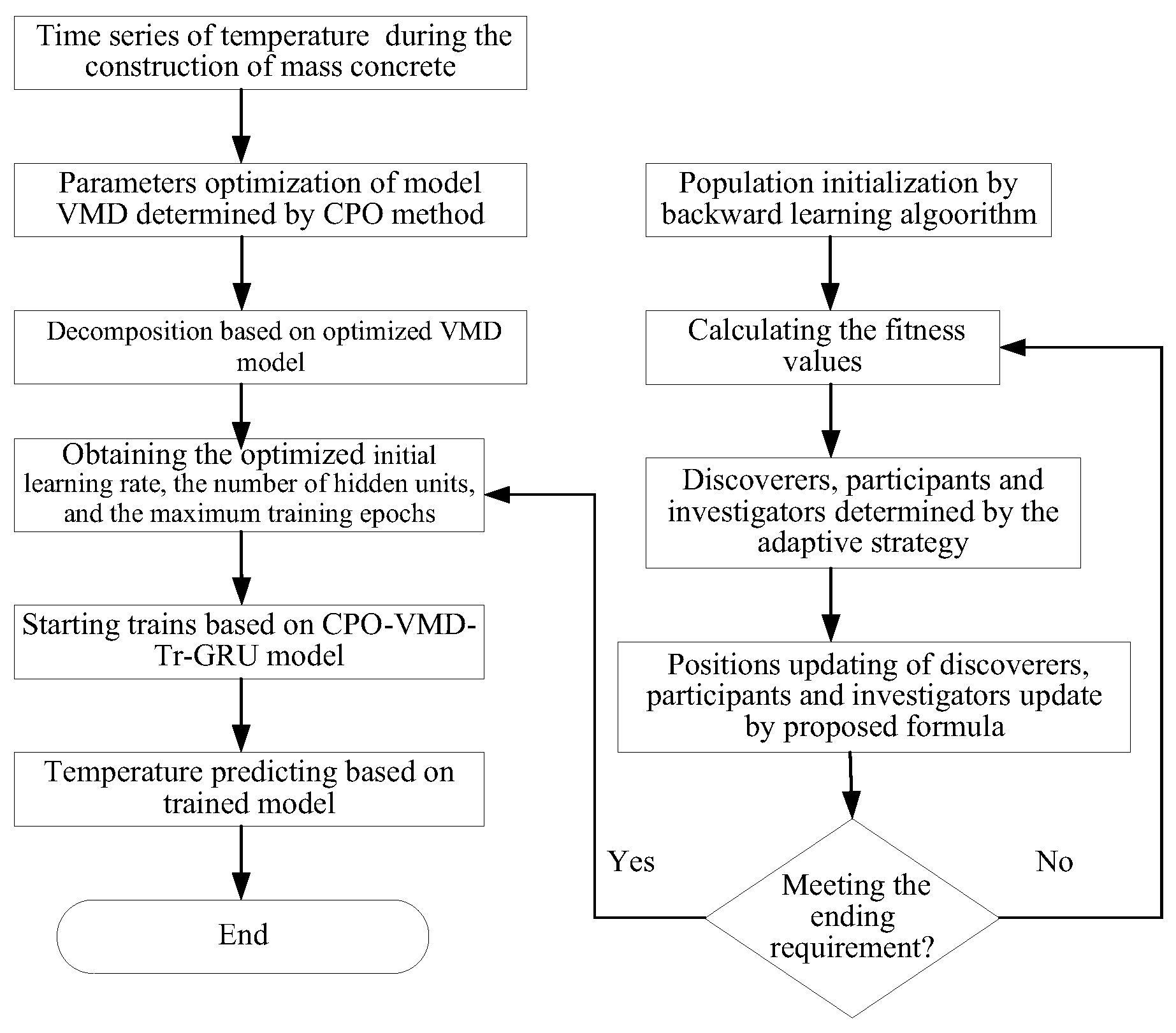

2. Construction of the Deeply Optimized CPO-VMD-SSA-Tr-GRU Model

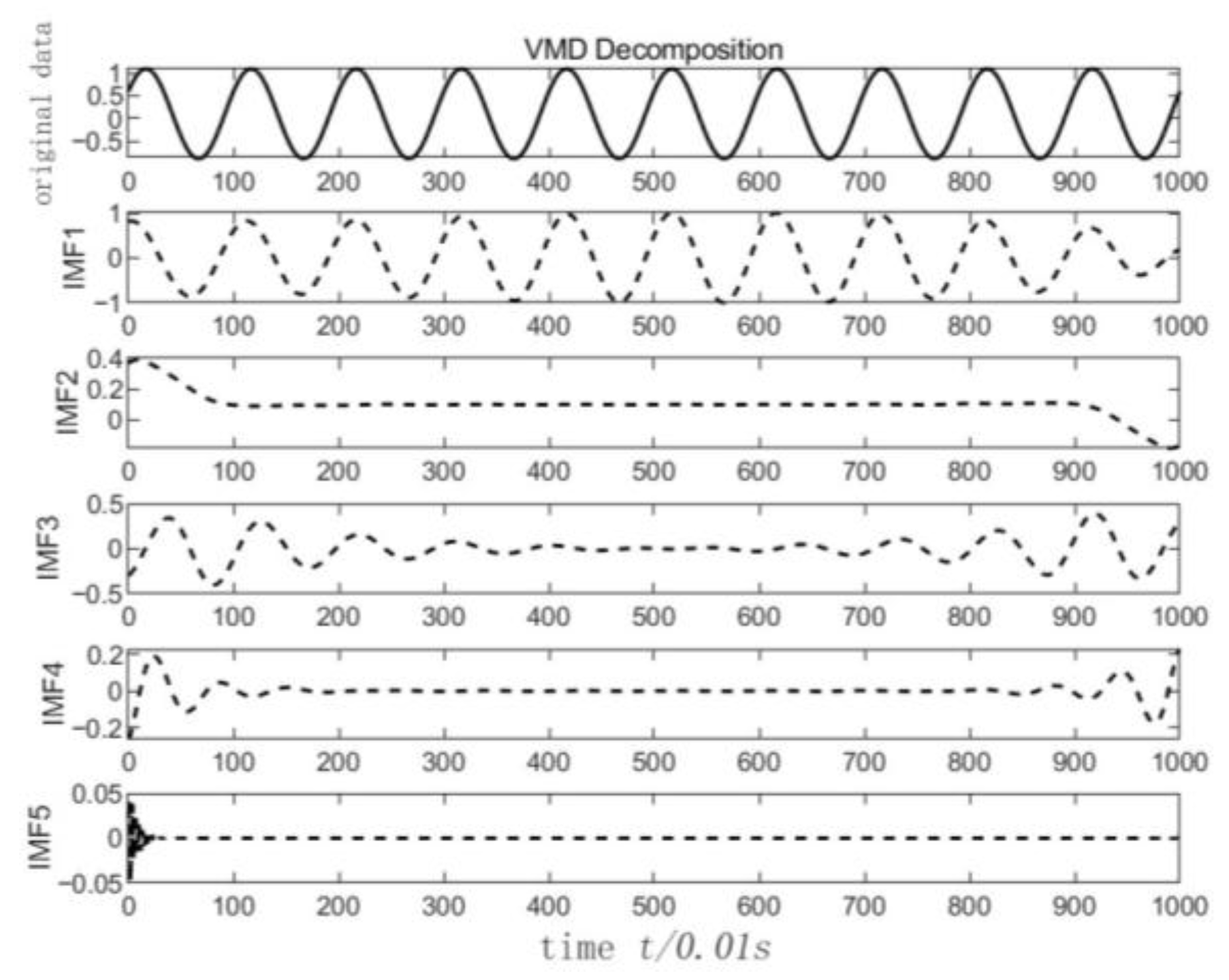

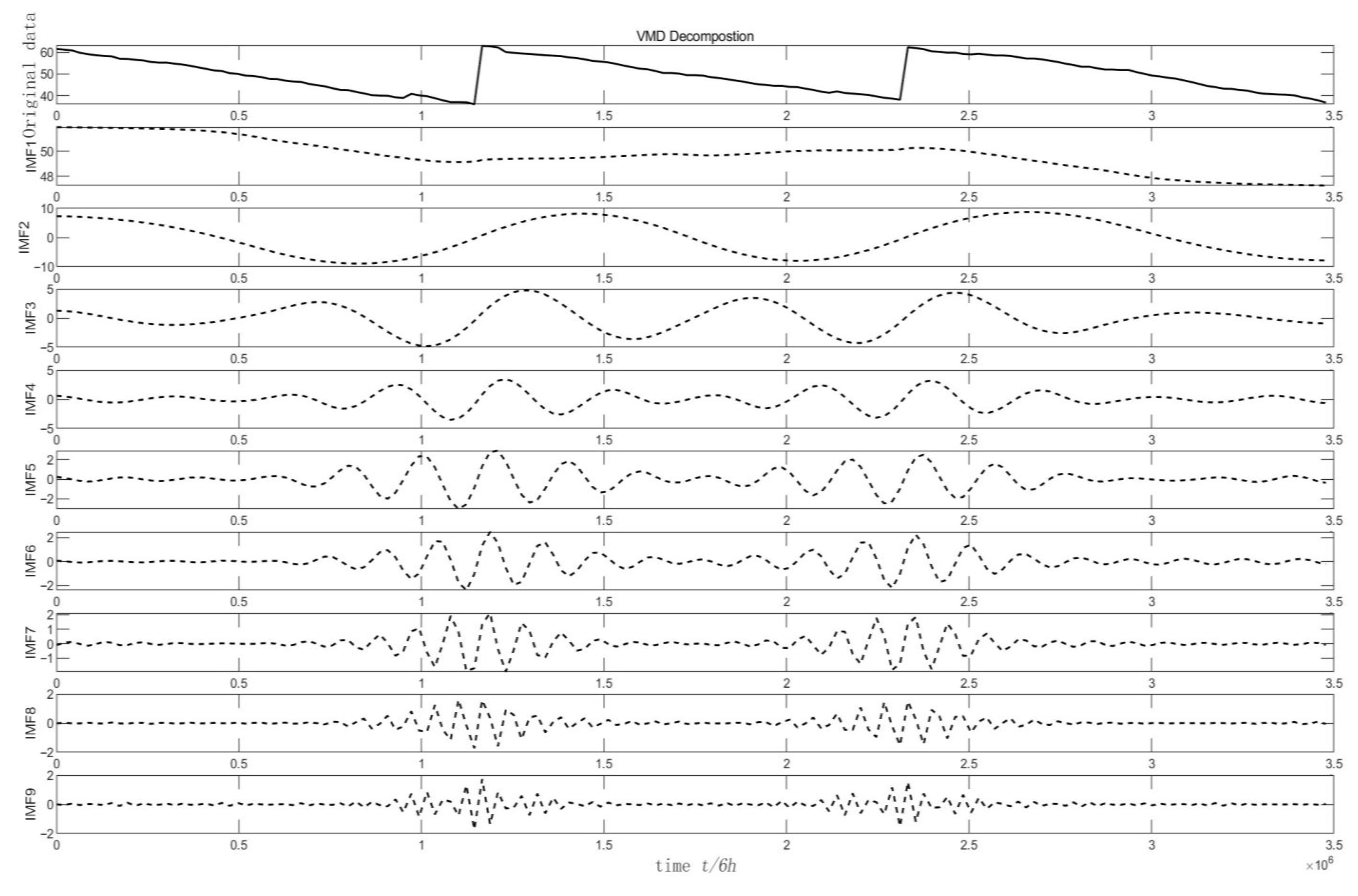

2.1. CPO-Optimized VMD for Time Series Data Processing

- (1)

- Construct the variational constraint model:

- (2)

- Initialize the parameters and search range of the Crested Porcupine Optimizer (CPO) and set the initial number of IMF components , the quadratic penalty factor , and the maximum number of iterations.

- (3)

- Update the population positions based on the four defense strategies in the Crested Porcupine Optimizer (CPO) to effectively explore the search space.

- (4)

- Perform iterative optimization until the optimal number of IMF components and the optimal quadratic penalty factor are obtained, thereby establishing the CPO optimized VMD modal.

2.2. Transformer Network Structure

2.3. GRU Network

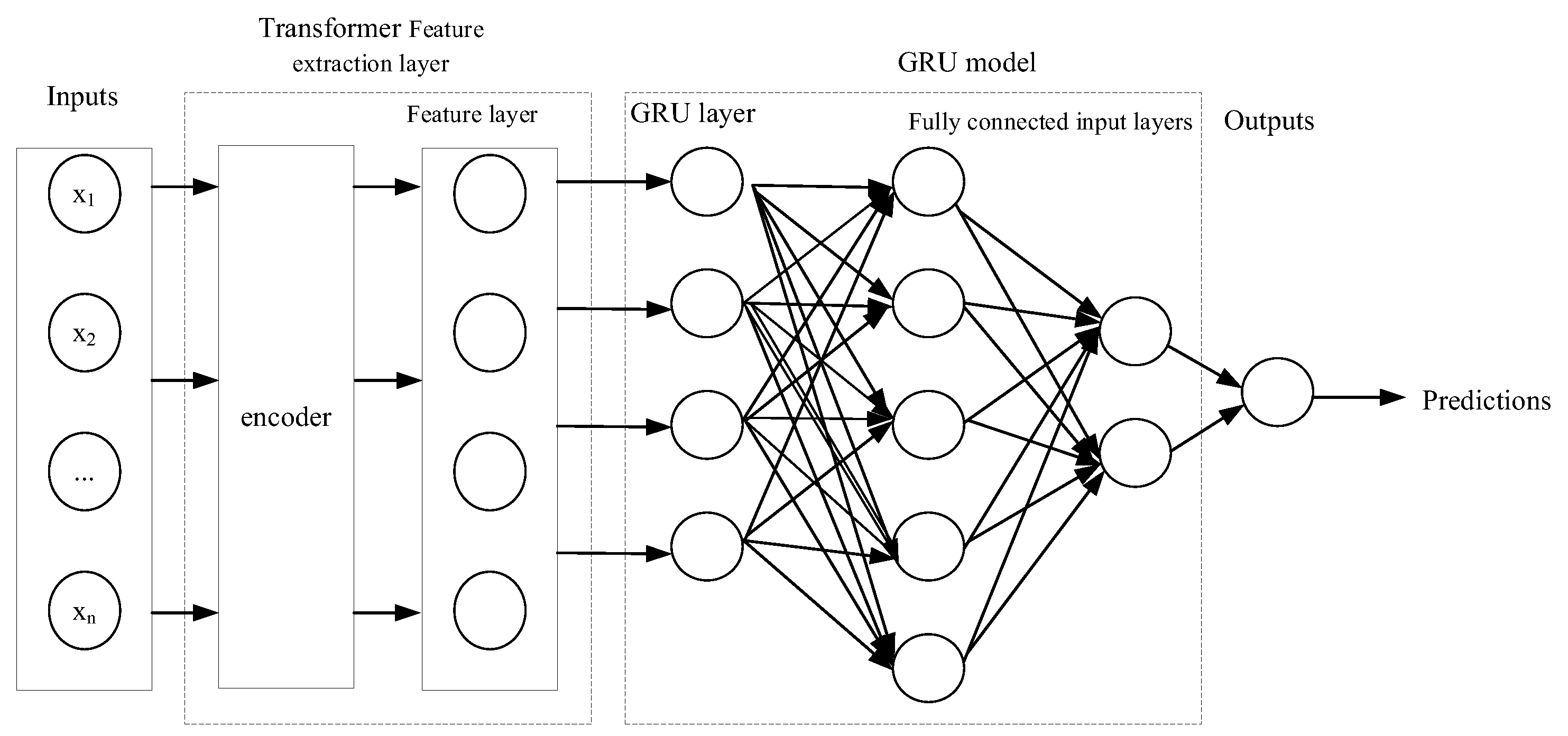

2.4. Transformer-GRU Model Structure

- (1)

- Input layer: Normalize the temperature time series and apply it in the model inputs. Assume the length of the data is , and describe as .

- (2)

- Transformer feature extraction layer: Consists of position encoding, multi-head attention mechanism, and feedforward neural network. Position information is labeled for each normalized data, representing different semantic information:

- (3)

- GRU model: The temperature series after extraction by the Transformer is applied as the input. The layer consists of fully connected input layers and fully connected GRU level output layers. The input fully connected layer is:

2.5. The Sparrow Search Algorithm

2.6. Construction of Deeply Optimized VMD-Transformer-GRU Model

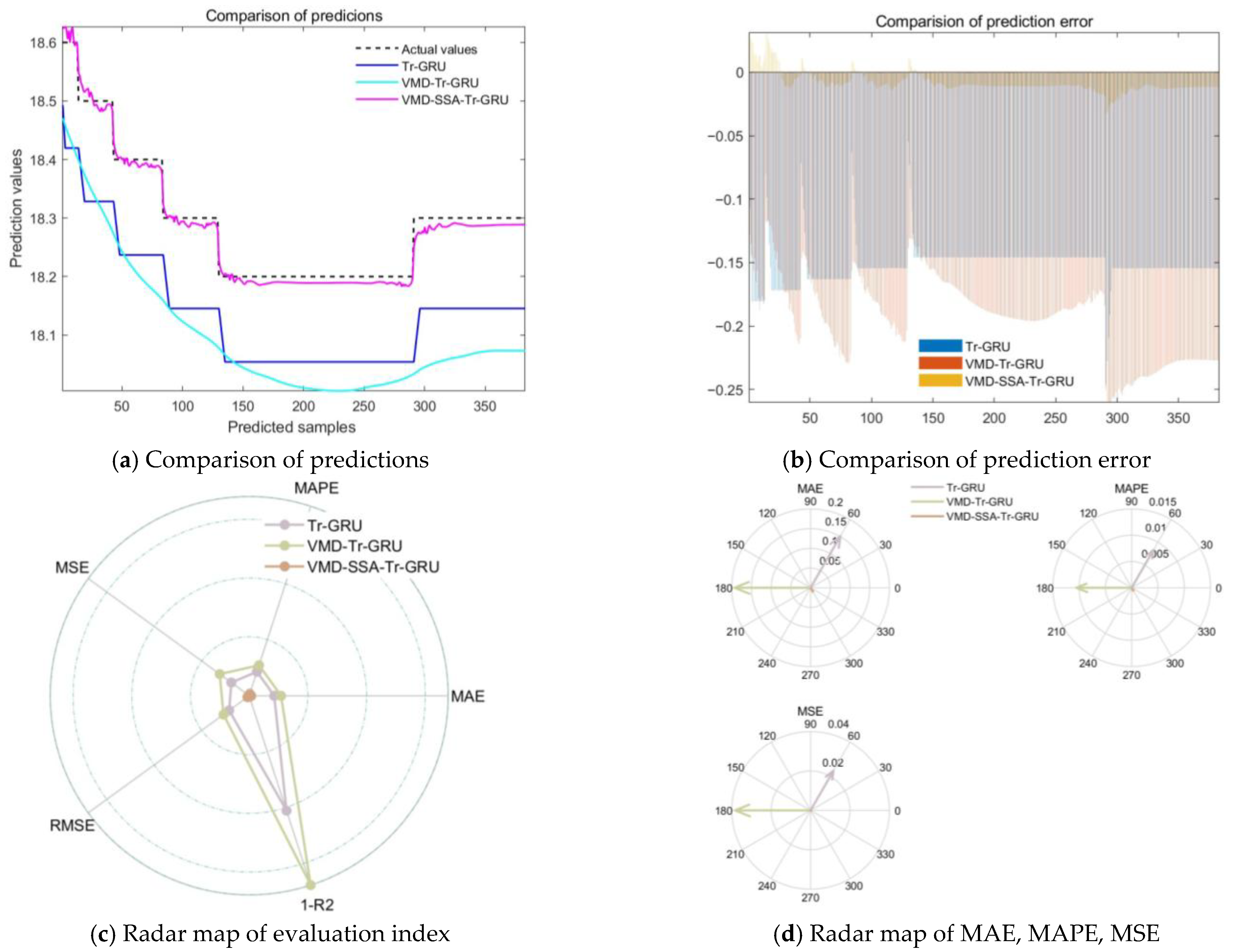

3. Verification and Assessment of the Deeply Optimized VMD-Transformer-GRU Model

4. Study on Temperature Prediction of Mass Concrete Based on a Deeply Optimized VMD-SSA-GRU Model

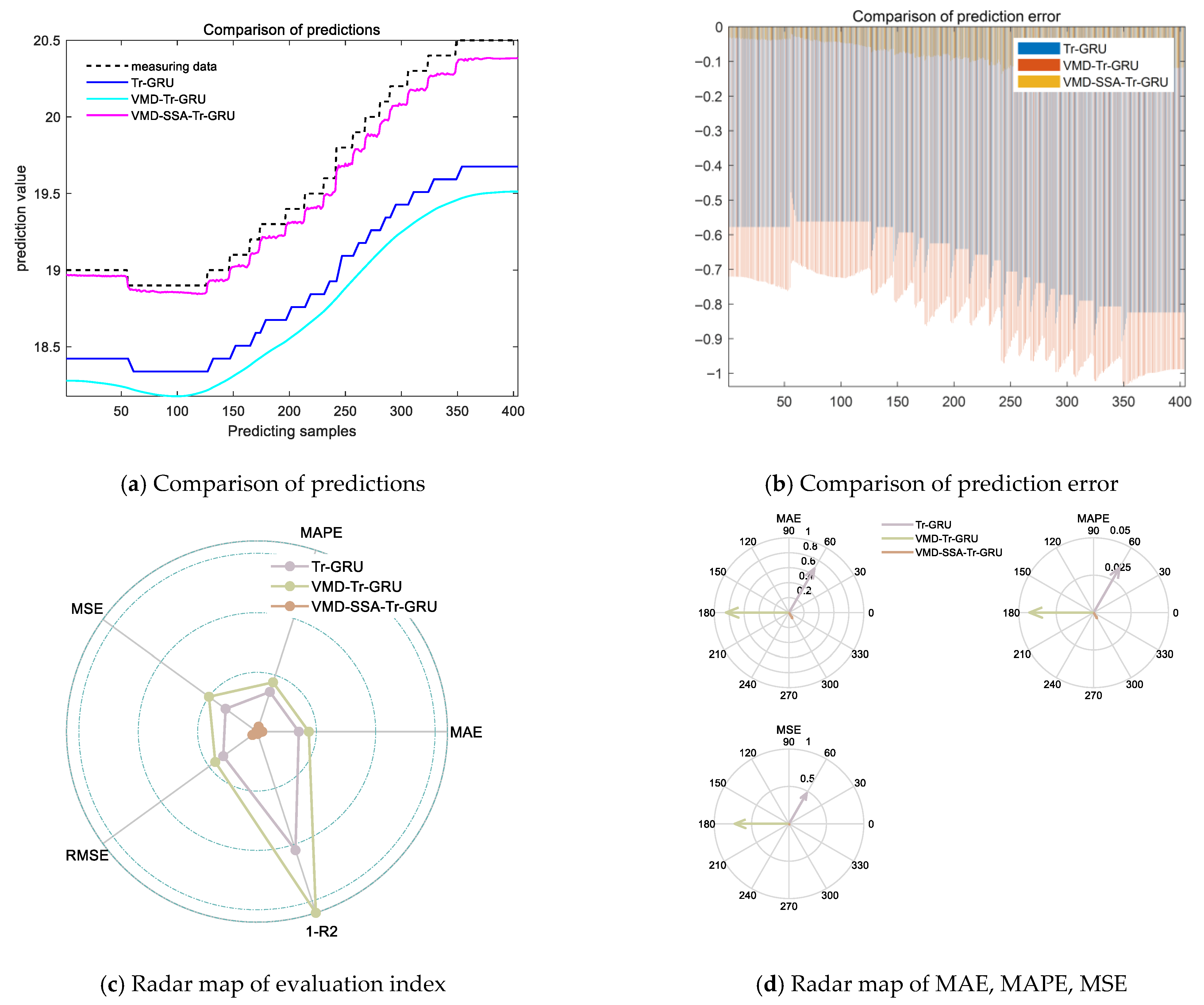

4.1. Temperature Prediction with Single Time Series for Lab Construction

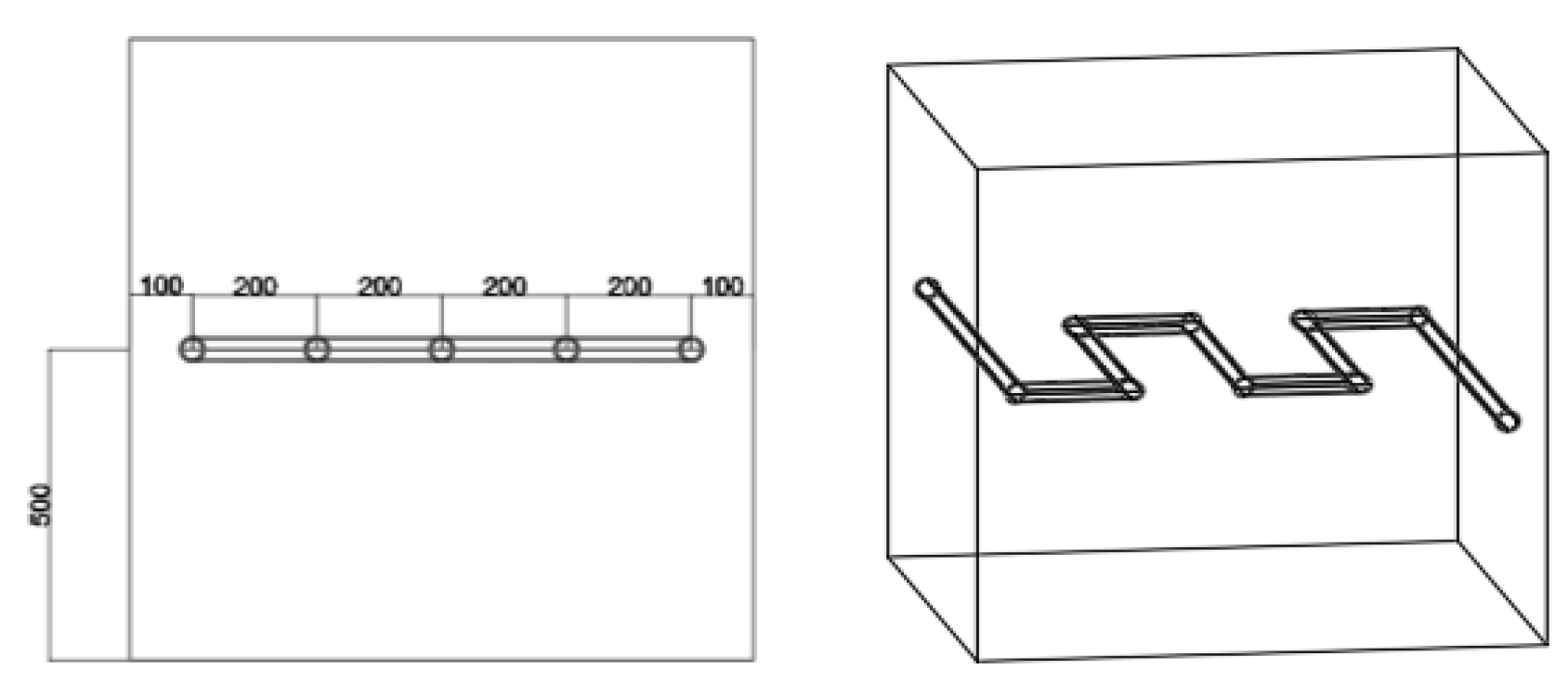

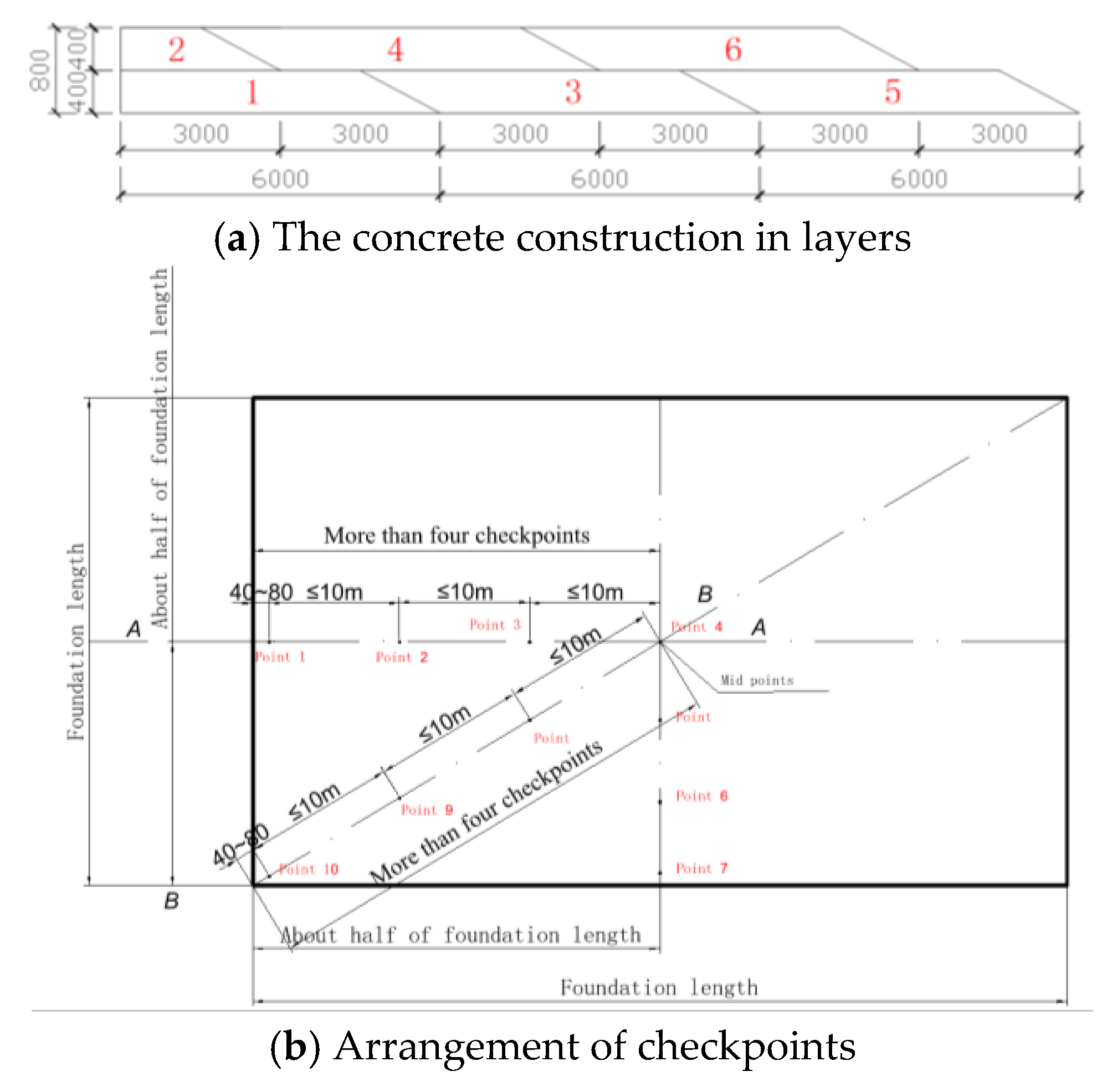

4.1.1. Test Design

4.1.2. Layout of the Cooling Pipes

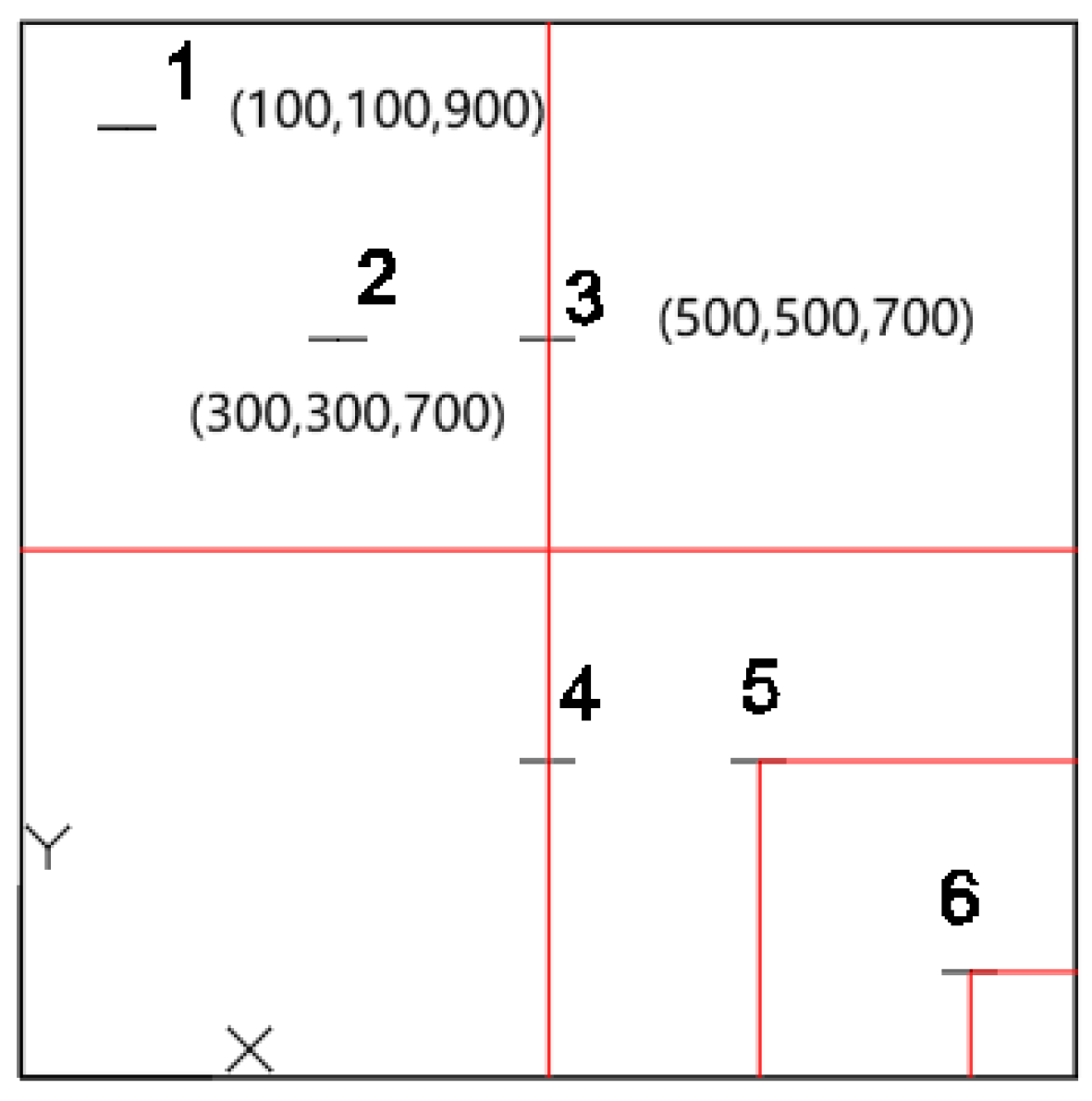

4.1.3. Placement of Temperature Measurement Points

4.1.4. Temperature Time Series Prediction Based on Lab Tests

4.2. Field Temperature Prediction Based on Multivariate CPO-VMD-SSA-Tr-GRU Model

4.2.1. Project Overview

4.2.2. Temperature Prediction Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- China Electric Power Development Report 2024; National Energy Administration Electric Power Planning and Design Institute: Beijing, China, 2024. Available online: https://www.nea.gov.cn/2024-07/19/c_1310782066.htm (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- Li, L.; Wang, S.; Ma, M. Finite Element Analysis of Large-volume Concrete Temperature Field Under the Conditions of Sequence Method. Constr. Technol. 2019, 48, 89–92. [Google Scholar]

- GB50496-2018; National Standard of the People’s Republic of China. Code for Construction of Mass Concrete. Architecture & Building Press: Beijing, China, 2018.

- GBT51028-2015; National Standard of the People’s Republic of China. Technical Specification for Temperature Measurement and Control of Mass Concrete. Architecture & Building Press: Beijing, China, 2015.

- Zheng, W.; Yuan, Z.; Qiao, H.; Song, P.; Zhu, Z. Analysis of Temperature Field of Mass Concrete Considering the Effect of Hydration Degree. Mater. Rep. 2024, 38 (S1), 262–268. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, D.; Chen, R.; Yang, R.; Zhang, Y. Analysis of Time-Varying Temperature Effect of Hydration Heat of Ultra-High Strength Mass Concrete. Ind. Constr. 2025, 55, 246–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klemczak, B.; Bąba, D.; Siddique, R. Machine Learning-Based Prediction of Heat Transfer and Hydration-Induced Temperature Rise in Mass Concrete. Energies 2025, 18, 4673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabir, H.; Wu, J.; Dahal, S.; Joo, T.; Garg, N. Automated estimation of cementitious sorptivity via computer vision. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 9935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, W. Simulation Analysis of Temperature Stress During the Construction Period of Concrete Pouring Blocks on Rock Foundation. Water Conserv. Plan. Des. 2022, 2, 88–93. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, B.; Huang, Y.; Fu, X.; Zhou, J.; Tang, T. Concrete Pouring Block’s Highest Temperature Prediction Model andIt’s Application Based on Uniform Design. Water Resour. Power 2014, 32, 90. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, S.; Lin, L.; Mao, W.; Wang, Y.; Liu, J.; Yuan, Y. A Hybrid RBF-PSO Framework for Real-Time Temperature Field Prediction and Hydration Heat Parameter Inversion in Mass Concrete Structures. Buildings 2025, 15, 2236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Fan, S.; Fang, C.; Huang, Y.; Liu, F. Internal Maximum Temperature Prediction of Concrete Pouring Block Based on Random Forest Algorithm. Water Resour. Power 2024, 42, 84–87. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, K.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, J.; He, X.; Cai, C.; Huang, S. Prediction of Concrete Box-Girder Maximum Temperature Gradient Based on BP Neural Network. J. Railw. Sci. Eng. 2024, 21, 837–850. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, S.; Zhou, S. Study on Temperature Evolution Rule and Prediction Method of Mass Concrete under Natural Condition. Water Resour. Hydropower Eng. 2018, 49, 188–196. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, C.; Tan, C.; Wang, X.; Huang, J.; Wang, Y.; Zhai, C. Prediction of Concrete Temperature in Temperature Rising Stage for High Arch Dam Based on LSTM Neural Network. Water Resour. Power 2022, 40, 101–104. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, J.; Kong, C.; Zou, K. Temperature Field Prediction During Concrete Construction Period of Pump and Sluice Project Based on LSTM. Adv. Sci. Technol. Water Resour. 2023, 43, 76–81. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z.; Liu, H. Combining Global and Sequential Patterns for Multivariate Time Series Forecasting. Chin. J. Comput. 2023, 46, 70–84. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Wang, Q.; Wu, T. A Novel Hybrid Model for Water Quality Prediction Based on VMD and I-GOA Optimized for LSTM. Front. Environ. Sci. Eng. 2023, 17, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, F.; Song, X.; Wang, Y.; Qin, C. A New Combined Prediction Model for Ultra-Short-Term Wind Power Based on Variational Mode Decomposition and Gradient Boosting Regression Tree. Sustainability 2023, 15, 11026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Dai, W.; Li, D.; Wu, Q. Short-Term Wind Power Prediction Based on a Variational Mode Decomposition-BiTCN-Psformer Hybrid Model. Energies 2024, 17, 4089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galassi, A.; Lippi, M.; Torroni, P. Attention in Natural Language Processing. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2020, 32, 4291–4308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Xu, J.; Wang, J.; Long, M. Autoformer: Decomposition Transformers with Auto Correlation for Long Term Series Forecasting. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2021, 34, 22419–22430. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, W.; Zheng, K.; Gao, L.; Zhang, L.; Lan, R.; Xu, L.; Yu, J. GRU-Transformer: A Novel Hybrid Model for Predicting Soil Moisture Content in Root Zones. Agronomy 2024, 14, 432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Jiang, D.; Sahli, H. Transformer Encoder with Multi-Modal Multi-Head Attention for Continuous Affect Recognition. IEEE Trans. Multimed. 2020, 23, 4171–4183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Liu, K.; Cheng, T.; Zhu, Y.; Xiong, M.; Zhao, C.; Peng, M. Intelligent Prediction Model for Deformation Induced by Excavation of Harbor Foundation Pit Based on Temporal Fusion Transformer. J. Basic Sci. Eng. 2025, 33, 1287–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, Z.; Li, W.; Wu, J.; Zhang, S.; Hu, S. A Novel Deep Learning Model for Mining Nonlinear Dynamics in Lake Surface Water Temperature Prediction. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Gao, B. Short-Term PV Power Forecasting Based on Improved VMD and SAS-Attention-GRU. Acta Energiae Solaris Sin. 2023, 44, 292–300. [Google Scholar]

- Zou, Z.; Wu, T.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, Z. Short-term Load Forecast Based on Bayesian Optimized CNN-BiGRU Hybrid Neural Networks. High Volt. Eng. 2022, 48, 3935–3945. [Google Scholar]

- Dai, Z.; Shi, K.; Zhu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Luo, Y. Intelligent Prediction of Transformer Loss for Low Voltage Recovery in Distribution Network with Unbalanced Load. Energies 2023, 16, 4432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Basset, M.; Mohamed, R.; Abouhawwash, M. Crested Porcupine Optimizer: A new nature-inspired metaheuristic. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2024, 284, 111257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Models Type | Mean Absolute Error (MAE) | Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE) | Mean Squared Error (MSE) | Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE) | Coefficient of Determination (R2) | Optimized Number of Hidden Units | Optimized Maximum Training Epochs | Optimized Initial Learning Rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tr-GRU (65%) | 0.098616 | 0.56336 | 0.012012 | 0.1096 | 0.9732 | |||

| VMD-Tr-GRU (65%) | 0.10277 | 0.7167 | 0.013282 | 0.11525 | 0.97037 | |||

| CPO-VMD-SSA-Tr-GRU (65%) | 0.06747 | 0.53725 | 0.005306 | 0.072839 | 0.98816 | 189 | 276 | 0.001 |

| Tr-GRU (80%) | 0.12107 | 0.45884 | 0.013775 | 0.11737 | 0.97154 | |||

| VMD-Tr-GRU (80%) | 0.27802 | 0.71633 | 0.018572 | 0.13628 | 0.96163 | |||

| CPO-VMD-SSA-Tr-GRU (80%) | 0.077425 | 0.50335 | 0.006795 | 0.08243 | 0.98596 | 81 | 72 | 0.01 |

| Tr-GRU (90%) | 0.071149 | 0.20958 | 0.006526 | 0.080781 | 0.98391 | |||

| VMD-Tr-GRU (90%) | 0.11331 | 0.48885 | 0.01676 | 0.12946 | 0.95867 | |||

| CPO-VMD-SSA-Tr-GRU (90%) | 0.032486 | 0.15236 | 0.001123 | 0.033505 | 0.99723 | 173 | 300 | 0.001 |

| Theoretical Values | Tr-GRU | VMD-Tr-GRU | CPO-VMD-SSA-Tr-GRU |

|---|---|---|---|

| −0.74438 | −0.63768 | −0.54035 | −0.71126 |

| −0.75424 | −0.64419 | −0.55027 | −0.72158 |

| −0.76316 | −0.64973 | −0.55933 | −0.73072 |

| −0.77113 | −0.65466 | −0.56754 | −0.7389 |

| −0.77815 | −0.65879 | −0.57487 | −0.74619 |

| −0.70032 | −0.65063 | −0.52141 | −0.68849 |

| −0.6862 | −0.64517 | −0.50911 | −0.67512 |

| −0.67121 | −0.63904 | −0.49598 | −0.66085 |

| −0.65536 | −0.63012 | −0.48203 | −0.6457 |

| −0.63867 | −0.61818 | −0.46727 | −0.62947 |

| 0.366769 | 0.254163 | 0.455529 | 0.380002 |

| 0.397657 | 0.282355 | 0.483981 | 0.410418 |

| 0.428351 | 0.31043 | 0.512218 | 0.440727 |

| 0.458819 | 0.33836 | 0.540204 | 0.471013 |

| 0.489032 | 0.366116 | 0.56791 | 0.50064 |

| 0.99653 | 0.845004 | 1.011617 | 0.96932 |

| 1.015128 | 0.863365 | 1.024764 | 0.983131 |

| 1.032921 | 0.881051 | 1.035954 | 0.995928 |

| 1.049893 | 0.898045 | 1.045545 | 1.007117 |

| 1.066025 | 0.914332 | 1.053257 | 1.016754 |

| Materials | Cement | Sand | Rock | Water | Fly Ash | Citric Acid |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mix proportion/(kg/m3) | 255 | 792 | 1047 | 160 | 76.5 | 0.5 |

| Parameters | Thermal Conductivity | Density | Thermal Expansion Coefficient | Outer Diameter | Wall Thickness |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| W·(m2·K) | g·cm−3 | (1/°C) | mm | mm | |

| Values | 0.15 | 1.35 | 7.0 × 10−5 | 10 | 2 |

| Model (90%) | Mean Absolute Error (MAE) | Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE) | Mean Squared Error (MSE) | Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE) | Coefficient of Determination (R2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tr-GRU | 0.26985 | 0.014994 | 0.074717 | 0.27334 | 0.33159 |

| VMD-Tr-GRU | 0.18487 | 0.010216 | 0.041103 | 0.20274 | 0.6323 |

| CPO-VMD-SSA-Tr-GRU | 0.033736 | 0.0018812 | 0.001305 | 0.036127 | 0.98832 |

| Model (90%) | Mean Absolute Error (MAE) | Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE) | Mean Squared Error (MSE) | Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE) | Coefficient of Determination (R2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tr-GRU | 0.11977 | 0.0065454 | 0.014632 | 0.12096 | −0.29235 |

| VMD-Tr-GRU | 0.10629 | 0.0058106 | 0.012472 | 0.11168 | −0.10157 |

| CPO-VMD-SSA-Tr-GRU | 0.016725 | 0.00091304 | 0.000365 | 0.019114 | 0.96773 |

| Time | Temperature in Checkpoint 1 | Tr-GRU | VMD-Tr-GRU | CPO-VMD-SSA-Tr-GRU |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 March 2025 08:37:29 | 17.7 | 17.509176 | 17.53813 | 17.702385 |

| 2 March 2025 08:39:29 | 17.7 | 17.509176 | 17.535011 | 17.700686 |

| 2 March 2025 08:41:29 | 17.7 | 17.509176 | 17.531834 | 17.703773 |

| 2 March 2025 08:43:29 | 17.7 | 17.509176 | 17.528616 | 17.69643 |

| 2 March 2025 08:45:29 | 17.6 | 17.509176 | 17.525337 | 17.640261 |

| ....... | ....... | |||

| 2 March 2025 11:57:29 | 17.5 | 17.326246 | 17.415298 | 17.495182 |

| 2 March 2025 11:59:29 | 17.5 | 17.326246 | 17.417297 | 17.496754 |

| 2 March 2025 12:01:29 | 17.5 | 17.326246 | 17.419388 | 17.497347 |

| 2 March 2025 12:03:29 | 17.5 | 17.326246 | 17.421614 | 17.497026 |

| 2 March 2025 12:05:29 | 17.5 | 17.326246 | 17.424023 | 17.502207 |

| 2 March 2025 12:07:29 | 17.5 | 17.326246 | 17.426636 | 17.509899 |

| ....... | ....... | |||

| 2 March 2025 14:27:29 | 18 | 17.600578 | 17.667452 | 17.918709 |

| 2 March 2025 14:29:29 | 18 | 17.637152 | 17.673679 | 17.94673 |

| 2 March 2025 14:31:29 | 18 | 17.673702 | 17.68005 | 17.960423 |

| 2 March 2025 14:33:29 | 18 | 17.710236 | 17.686457 | 17.953716 |

| 2 March 2025 14:35:29 | 18 | 17.74675 | 17.692862 | 17.963177 |

| ....... | ....... | |||

| 2 March 2025 21:13:29 | 18.2 | 17.965757 | 17.969032 | 18.217176 |

| 2 March 2025 21:15:29 | 18.2 | 17.965757 | 17.968611 | 18.224201 |

| 2 March 2025 21:17:29 | 18.2 | 17.965757 | 17.968224 | 18.231836 |

| 2 March 2025 21:19:29 | 18.2 | 17.965757 | 17.967867 | 18.224049 |

| 2 March 2025 21:21:29 | 18.2 | 17.965757 | 17.967585 | 18.219481 |

| Time | Temperature in Checkpoint 2 | Tr-GRU | VMD-Tr-GRU | CPO-VMD-SSA-Tr-GRU |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 March 2025 08:37:29 | 18.6 | 18.438955 | 18.591953 | 18.655531 |

| 2 March 2025 08:39:29 | 18.6 | 18.402805 | 18.585485 | 18.653751 |

| 2 March 2025 08:41:29 | 18.6 | 18.366646 | 18.579208 | 18.656033 |

| 2 March 2025 08:43:29 | 18.6 | 18.366646 | 18.573275 | 18.65411 |

| 2 March 2025 08:45:29 | 18.6 | 18.366646 | 18.567556 | 18.636728 |

| ....... | ||||

| 2 March 2025 18:07:29 | 18.2 | 18.095301 | 18.193825 | 18.254673 |

| 2 March 2025 18:09:29 | 18.2 | 18.077196 | 18.191532 | 18.242689 |

| 2 March 2025 18:11:29 | 18.2 | 18.059097 | 18.189159 | 18.235815 |

| 2 March 2025 18:13:29 | 18.2 | 18.040998 | 18.186775 | 18.23225 |

| 2 March 2025 18:15:29 | 18.2 | 18.0229 | 18.184435 | 18.2293 |

| ....... | ||||

| 2 March 2025 21:13:29 | 18.3 | 18.095301 | 18.187534 | 18.315294 |

| 2 March 2025 21:15:29 | 18.3 | 18.095301 | 18.187517 | 18.315332 |

| 2 March 2025 21:17:29 | 18.3 | 18.095301 | 18.187502 | 18.315245 |

| 2 March 2025 21:19:29 | 18.3 | 18.095301 | 18.18749 | 18.315292 |

| 2 March 2025 21:21:29 | 18.3 | 18.095301 | 18.187479 | 18.315359 |

| Model (90%) | Mean Absolute Error (MAE) | Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE) | Mean Squared Error (MSE) | Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE) | Coefficient of Determination (R2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tr-GRU | 0.68044 | 0.034632 | 0.47444 | 0.6888 | −0.25914 |

| VMD-Tr-GRU | 0.84392 | 0.042979 | 0.72543 | 0.85172 | −0.92526 |

| CPO-VMD-SSA-Tr-GRU | 0.086023 | 0.004347 | 0.0087186 | 0.093374 | 0.97686 |

| No. | Air Temperature | Temperature in Point 1 |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 27 | 61.5 |

| 2 | 29 | 61.2 |

| 3 | 35 | 60.8 |

| 4 | 30 | 59.7 |

| 5 | 25 | 59.1 |

| 6 | 24 | 58.6 |

| 7 | 33 | 58.3 |

| 8 | 26 | 58.1 |

| 9 | 24.5 | 57 |

| 10 | 23.5 | 56.9 |

| 11 | 33 | 56.5 |

| 12 | 24 | 56.2 |

| ....... | ||

| 155 | 29 | 40.7 |

| 156 | 23.5 | 40.5 |

| 157 | 21 | 40.4 |

| 158 | 20.5 | 40.1 |

| 159 | 26 | 39.2 |

| 160 | 23 | 38.6 |

| 161 | 19.5 | 37.8 |

| 162 | 19 | 36.8 |

| Model (90%) | Mean Absolute Error (MAE) | Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE) | Mean Squared Error (MSE) | Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE) | Coefficient of Determination (R2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tr-GRU | 3.0803 | 0.074958 | 10.04 | 3.1686 | −0.35282 |

| VMD-Tr-GRU | 1.9667 | 0.047363 | 4.0716 | 2.0178 | 0.45136 |

| CPO-VMD-SSA-Tr-GRU | 0.56293 | 0.013677 | 0.34035 | 0.58339 | 0.95414 |

| Actual Temperature in Point 1 | Tr-GRU | VMD-Tr-GRU | CPO-VMD-SSA-Tr-GRU |

|---|---|---|---|

| 47 | 48.998734 | 48.496426 | 47.413113 |

| 46.2 | 48.129364 | 47.932735 | 46.654602 |

| 45.3 | 47.373768 | 47.168629 | 45.828285 |

| 44.4 | 47.313866 | 46.59811 | 44.816147 |

| 43.9 | 46.617676 | 46.036911 | 44.310432 |

| 43.2 | 45.771885 | 45.418903 | 43.722919 |

| 43.1 | 45.075943 | 44.689621 | 43.50808 |

| 42.6 | 45.1549 | 44.154358 | 43.091953 |

| 42.3 | 44.761082 | 43.633194 | 42.700665 |

| 41.5 | 44.24445 | 43.097313 | 42.002522 |

| 40.9 | 43.835213 | 42.524963 | 41.471081 |

| 40.7 | 44.286972 | 42.286591 | 41.33123 |

| 40.5 | 43.759117 | 41.922653 | 41.030804 |

| 40.4 | 42.908455 | 41.520748 | 40.916813 |

| 40.1 | 42.51244 | 40.93829 | 40.453896 |

| 39.2 | 42.76593 | 40.625797 | 39.809101 |

| 38.6 | 42.542824 | 40.3825 | 39.277225 |

| 37.8 | 41.927334 | 40.073124 | 38.56871 |

| 36.8 | 41.40247 | 39.710876 | 37.821724 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zheng, F.; Xia, S.; Chen, J.; Li, D.; Lu, Q.; Hu, L.; Liu, X.; Song, Y.; Dai, Y. Temperature Prediction of Mass Concrete During the Construction with a Deeply Optimized Intelligent Model. Buildings 2025, 15, 4392. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15234392

Zheng F, Xia S, Chen J, Li D, Lu Q, Hu L, Liu X, Song Y, Dai Y. Temperature Prediction of Mass Concrete During the Construction with a Deeply Optimized Intelligent Model. Buildings. 2025; 15(23):4392. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15234392

Chicago/Turabian StyleZheng, Fuwen, Shiyu Xia, Jin Chen, Dijia Li, Qinfeng Lu, Lijin Hu, Xianshan Liu, Yulin Song, and Yuhang Dai. 2025. "Temperature Prediction of Mass Concrete During the Construction with a Deeply Optimized Intelligent Model" Buildings 15, no. 23: 4392. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15234392

APA StyleZheng, F., Xia, S., Chen, J., Li, D., Lu, Q., Hu, L., Liu, X., Song, Y., & Dai, Y. (2025). Temperature Prediction of Mass Concrete During the Construction with a Deeply Optimized Intelligent Model. Buildings, 15(23), 4392. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15234392