Abstract

Urban neighborhoods experiencing socio-spatial pressures increasingly struggle with sustainability, especially in contexts where top-down redevelopment models dominate. In Turkey, the commonly used “demolish-and-rebuild” approach is often criticized for neglecting urban identity and the continuity of local communities. This study examines the Kükürtlü Neighborhood in Bursa, a “double-aged” area characterized by both an elderly population and aging housing stock. Using a mixed-method approach, the study integrates the EcoDistricts framework with participatory spatial analysis and Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis (IPA) to assess sustainability across three priority areas: place, health and wellbeing, and connectivity. Results reveal that while the neighborhood faces structural limitations and underutilized public spaces, it benefits from strong social sustainability rooted in cultural continuity and intergenerational bonds, especially among long-term residents. Conversely, newcomers demonstrate weaker place attachment. These findings inform a set of inclusive, aging-in-place strategies aimed at balancing physical renewal with community preservation. Building on these insights, the study proposes a context-sensitive and potentially adaptable framework to guide sustainability efforts in similar aging urban contexts. The research contributes to international discussions on urban transformation by emphasizing the importance of integrating local lived experiences with spatial planning tools, offering a model for navigating demographic and physical aging in mid-sized cities.

1. Introduction

Currently, half of the world’s population resides in urban areas, and this proportion is projected to reach two-thirds by 2050 [1]. However, the physical expansion of cities often outpaces population growth, negatively affecting sustainability [2]. In China, economic reforms and industrialization in the late 1970s triggered rural-to-urban migration and the rise of megacities [3], accompanied by farmland loss, air and water pollution, and increased resource consumption [4,5,6,7]. In the United States, post-Depression and post-World War II suburbanization—supported by credit policies and highway investments—aimed to address housing needs and stimulate employment [8,9,10,11,12]. Yet, these policies resulted in fragmented urban form, high energy use, emissions, and inner-city decline [10,12,13,14]. In Europe, post war suburban development reduced investment in city centers and shaped low-income settlement patterns [15,16]. Since the 1960s, gentrification—reinforced by heritage conservation and housing finance policies—has further contributed to social inequality [16,17]. Although regional dynamics vary, industrial growth, changing lifestyle-related spatial demands, exposure to natural hazards, and recent demographic shifts—particularly population aging—have become major forces shaping contemporary cities [18].

Turkey experienced rapid industrialization in the second half of the 20th century, leading to significant changes in traditional urban housing stock to accommodate increased density from rural-to-urban migration. By the late 20th century, major earthquakes in the Marmara Region exposed structural vulnerabilities and prompted new regulations for urban transformation. However, the prevailing focus on earthquake resilience prioritized rapid reconstruction, often through large-scale demolition and rebuilding [19]. These ongoing renewal processes [20] have raised significant sustainability concerns, including the loss of cultural and spatial identity [21,22,23], spatial segregation, degradation of natural resources [24] and disruption of urban continuity [25]. Moreover, many neighborhoods in Turkey often face redevelopment pressures before fully experiencing demographic and physical aging. The inability to maintain double-aging conditions undermines social ties, increases displacement risks, and limits opportunities for aging in place.

Globally, urban challenges have been a key concern for the United Nations. Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 11 (2015–2030) aims to ensure urban areas are sustainable, resilient, inclusive, and safe [2]. In Turkey, the “Integrated Urban Development Strategy and Action Plan (KENTGES, 2010–2023)” provides principles, strategies, and implementation tools for sustainable development [26]. At the building scale, national assessment systems such as the “National Green Certificate” (YeS-TR) and “Ecological and Sustainable Design” (B.E.S.T) have been introduced [27,28]. The “Sustainable Building Assessment System” (SEEB-TR) and its neighborhood-scale version, SEEB-TR Neighborhood, offer performance-based tools to evaluate projects using urban design and regulatory frameworks [29]. Despite these efforts, most assessments are applied after project completion, highlighting the need for participatory, process-based tools that guide transformation from early planning stages.

Understanding sustainability within its local context and integrating key challenges into planning have shaped sustainability assessment approaches [30,31,32,33,34,35]. These assessments support decision-making by identifying actions that promote sustainable outcomes [32]. While early studies focused on city and regional scales [36,37], neighborhood-scale assessment has gained importance for capturing urban sustainability more comprehensively [38]. Since the early 2000s, neighborhood assessments have gained prominence by offering manageable opportunities to address sustainability through vision, governance, design, and technical strategies [39,40,41,42,43,44]. Alongside product-based approaches that emphasize measurable performance, process-based approaches—highlighting inclusive decision-making and stakeholder engagement—have gained value [45,46]. Rather than relying solely on fixed categories, these approaches involve local communities to develop more context-sensitive and resilient solutions [46,47].

Various sustainability assessment tools were examined in order to select the most appropriate tool for the study area Kükürtlü District, Bursa, Turkey. As an existing neighborhood under transformation pressure, the selected tool needed to support decision-making and adopt a process-based framework. Flexibility in adapting criteria to different geographies and local contexts was therefore essential.

Kükürtlü District was originally developed as a summer retreat, characterized by historic mansions, baths, and a green landscape dating back Byzantine times—some of which remain today. In the 1960s, with rising industrialization in Bursa, it gradually transformed into a high-income residential area, replacing traditional houses with modern apartment blocks. Due to its low density and quality living environment, it remained one of the city’s distinctive neighborhoods until the early 2000s. Today, however, the neighborhood faces double aging—of both population and housing stock are aging. Its location in an earthquake-prone zone has further increased pressure for redevelopment, while local authorities often fail to reflect the area’s specific needs and character in their decision-making processes. A comprehensive sustainability assessment is therefore urgently needed.

Within the scope of this study, the EcoDistricts sustainability assessment tool was used to guide decision-making through a participatory approach. The aim is to evaluate sustainability in an aging neighborhood and develop action proposals for its future development. While many existing tools prioritize measurable indicators, they tend to overlook lived experiences and socio-spatial dynamics. Responding to this gap, the study combines process-oriented evaluation with insights from an aging population and aging housing stock—dual challenges increasingly relevant in cities worldwide. To support planning, it also offers a context-sensitive framework that, while based on the Kükürtlü case, may inform strategies in similar ‘double-aging’ neighborhoods.

The list of abbreviations used throughout the article is provided at the end for the reader’s reference.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Urban Transformation and Double Aging: A Sustainability Perspective

Urban areas worldwide are undergoing rapid transformation under the pressure of population growth, which reached 8.2 billion in 2024 and is expected to exceed 10.3 billion by the mid-2080s [1]. This expansion has encouraged strategies of demolition and reconstruction, often disregarding existing urban values and contributing to the loss of local identity, social networks and spatial integrity [20,48]. These practices not only disrupt the socio-economic balance of neighborhoods but also lead to environmental and cultural degradation [49,50]. In contrast, the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goal 11 advocates for safe, inclusive and resilient urban development, emphasizing disaster risk reduction (11.5), cultural continuity (11.4) and equitable access to services and green spaces (11.3, 11.7) [2,51].

In this context, population aging has emerged as a major demographic force shaping urban planning. By 2050, individuals aged 65 and over are expected to constitute 16% of the global population, exceeding 25% in some countries [18]. In contrast, the World Health Organization defines age-friendly cities as environments that support active aging through inclusiveness and accessibility [52]. Aging in place strategies, such as housing modifications for accessibility [53], and age-friendly public spaces [52,54], have been highlighted as approaches that promote autonomy, continuity, and psychological wellbeing for older adults [54]. In recent urban studies, the term “double aging” has been used to describe the simultaneous occurrence of two parallel processes: the demographic aging of the population and the physical aging of facilities and the built environment [55,56]. Neighborhoods experiencing double aging face multifaceted spatial, social, and environmental vulnerabilities, including accessibility challenges for older adults, a deteriorating housing stock, and the erosion of architectural identity and memory. Despite their importance, urban renewal processes often overlook the spatial and social needs of populations, exacerbating the trauma and social fragmentation associated with displacement [57,58].

Therefore, the literature increasingly supports the need for integrated frameworks that address these issues holistically. Participatory urban renewal strategies that involve residents in decision-making have been shown to preserve neighborhood fabric and promote socio-cultural continuity [59,60,61]. These approaches are considered in conjunction with sustainability assessment tools that help identify spatial strengths and weaknesses while enabling stakeholder participation [30,62].

The literature review reveals discussions on bottom-up strategies and participatory practices [60,61], studies emphasizing the social and economic aspects of urban renewal [50,63], and studies addressing the issue through aging-in-place interventions [64]. These three approaches are generally characterized by their focus on the social dimensions of urban renewal processes. In the literature focusing on the old built environment, studies have largely focused on issues such as physical and spatial rehabilitation strategies [55] and the legal and organizational mechanisms associated with the repair of old building stock [65]. While there are successful studies on spatial transformation and rehabilitation strategies, they have lacked a simultaneous examination of the social dimension of rehabilitation. While there are more integrated studies addressing the sustainability of the old built environment and incorporating assessment tools into decision-making processes [65], research assessing double aging from a holistic sustainability perspective is quite limited.

Given these complex challenges, evaluating transformation decisions from a sustainability perspective is becoming increasingly important. In the transformation of double aging neighborhoods, sustainability assessment is crucial for determining the sustainability values of the place and ensuring community participation. This assessment enables the development of a holistic approach that integrates physical rehabilitation with community-based resilience planning.

2.2. Approaching Sustainability from a Neighborhood Scale

While various initiatives have promoted urban sustainability, addressing systems at the neighborhood scale has become essential. As the city’s basic unit, the neighborhood is a multidimensional system that includes physical elements (built environment), social aspects (demographics, interaction, sense of place), and environmental factors (topography, landscape, air and water quality) [66].

Its scale is suitable for analysis, as it allows for the testing of innovative planning and design strategies at a manageable size, while also linking to broader urban systems [67,68]. Moreover, the neighborhood is well-suited for implementing sustainability goals in line with the New Urban Agenda and the SDGs, as it supports social interaction and encourages local actor participation in decision-making [67,69].

2.3. Neighborhood Sustainability Assessment

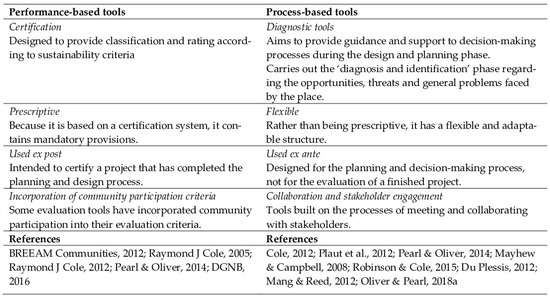

Neighborhood Sustainability Assessment (NSA) tools evaluate how well a neighborhood meets sustainability goals by analyzing various themes and current conditions [39]. These tools fall into two main categories [70,71]. The first, adapted from building certification systems, includes “spin-off”, “performance-based”, or “product-based” tools [72]. The second category, shaped by past experiences and integrated into planning, includes “plan-embedded”, “process-based”, or “design-support” tools [70,72].

Performance-based tools focus on technical criteria, while process-based ones embed assessment in planning, covering aspects like social cohesion, urban form, biodiversity, and disaster resilience [72]. This second group also emphasizes governance models based on stakeholder participation.

This study primarily aims to assess the sustainability of an aging neighborhood with unique values within the city and to provide guidance for decision-making processes that promote sustainable development. Its applicability to other neighborhoods with similar characteristics is particularly relevant to achieving SDG 11. In this context, the study prioritizes selecting an assessment tool that (1) enables the identification and definition of place-specific sustainability conditions, (2) actively involves users in the process, and (3) is supported by current academic research and accessible to all.

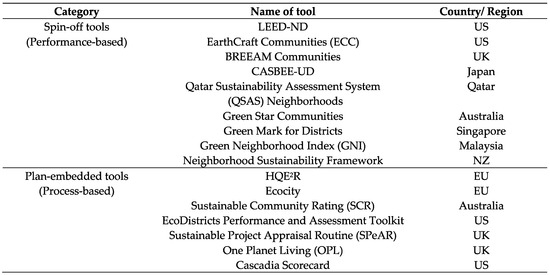

The most widely recognized NSA tools are presented in Figure 1, categorized into spin-off and plan-embedded tools. Process-based tools aid early decision-making, while performance-based tools focus on completed projects, often relying on rigid criteria. Both encourage user involvement, but process-based tools integrate it throughout, while performance-based tools limit it to scoring (Appendix A). Given the study’s focus, process-based tools are preferred for their flexibility and process orientation. Sharifi and Murayama identify HQE2R, Ecocity, and SCR as key spin-off tools, evaluated by technical strength, scope, and accessibility [39]. HQE2R and the EcoDistricts Toolkit are also linked to urban regeneration [36,44]. This study analyzes all four tools for their contextual relevance.

Figure 1.

Some of the well-known neighborhood sustainability assessment (NSA) tools (adapted from [39,72]).

HQE2R, a 30-month EU-supported project conducted in seven countries, was led by CSTB in France [36]. It introduced three main tools: Indicators Impact Model (INDI), Environmental Impact (ENVI), and Assessment of Shared Global Cost and Externalities (ASCOT). The framework addresses heritage preservation, environmental quality, diversity, and social integration through four stages: problem definition, sustainability analysis, scenario development, and action planning [73]. Ecocity, under the EU’s Fifth Framework Programme, focused on integrating transportation with urban form and developing a collaborative design model encompassing climatic and socio-cultural variations [74]. The Australian-originated SCR tool, developed by VicUrban, aims to integrate economic, environmental, and social sustainability. It offers models for three settlement types (Master Planned, Urban Renewal, Provincial Community) and addresses housing access, environmental leadership, social welfare, and commercial viability [37,75].

The EcoDistricts Framework, initiated through pilot projects in Portland in 2010 and institutionalized nationwide in 2012, became formalized under the Portland Sustainability Institute [76]. The EcoDistricts Protocol, published in 2016, supports neighborhood-level sustainability, focusing on urban regeneration through three core principles—equity, resilience, and climate protection—and six additional priorities [77]. The protocol’s application follows three stages: formation, roadmap, and performance [44]. Since 2015, EcoDistricts has used a case-based, process-oriented certification model, distinct from traditional scoring-based systems [76].

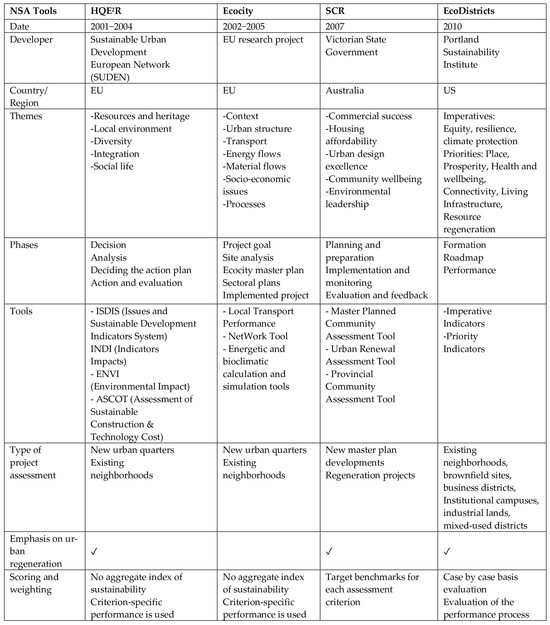

All compared assessment tools emphasize stakeholder participation and collaboration. Thematically, the Ecocity tool focuses on transportation and integrated planning, making it unsuitable for assessing the existing neighborhood fabric in Bursa. In contrast, HQE2R, SCR, and EcoDistricts center on urban renewal. However, SCR’s specific structure and Australian origin limit its applicability to the local context, and it was not selected (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Comparison of HQE2R, Ecocity, SCR and EcoDistricts (compiled by author from [44,73,75,78]).

The EcoDistricts tool was considered as the most relevant reference due to its focus on urban renewal, participatory and process-oriented approach, and flexible structure that allows adaptation to local values. Rather than using the EcoDistricts model as-is, this study creates a new framework that draws from its principles but is adjusted to suit the challenges of the selected aging neighborhood.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Theoretical Framework: EcoDistricts Neighborhood Assessment

EcoDistricts Protocol provides a holistic framework for neighborhood-scale sustainability, supported by collaboration among public, private, and civil actors through inclusive governance. While enhancing local sustainability, it also functions as a hybrid tool and certification system to assess protocol compliance [72]. The updated Version 1.3 (2018) defines three core principles—equity, resilience, and climate protection—along with six priority areas and three implementation phases [77]. These guide urban regeneration by integrating economic, social, and environmental sustainability.

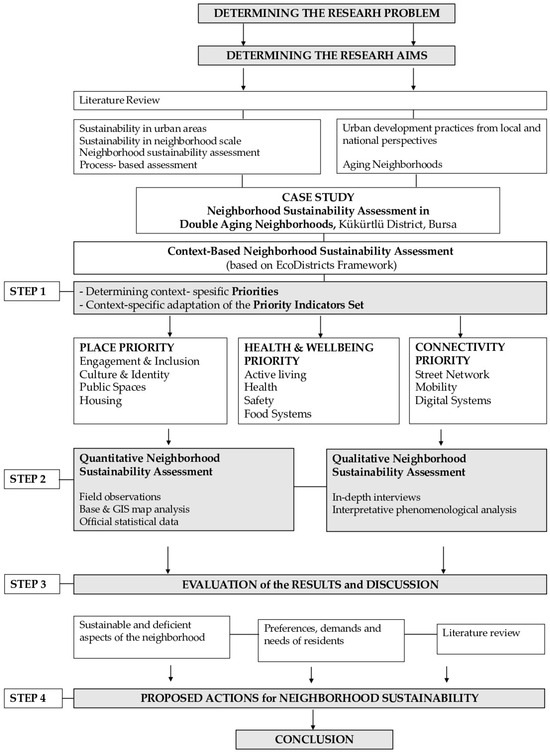

The EcoDistricts (v2018) framework includes six thematic areas—place, prosperity, health & wellbeing, connectivity, living infrastructure, and resource regeneration—designed to support sustainable local development. “Place” promotes inclusive, vibrant communities through cultural identity, public spaces, and affordable housing. “Prosperity” emphasizes education, economic opportunity, and innovation. “Health & wellbeing” addresses active living, healthcare, safety, and food systems. “Connectivity” covers transport, street networks, and digital access. “Living infrastructure” enhances human-nature connections, while “resource regeneration” supports sustainability in energy, water, and waste [44] (Figure 3).

The protocol’s implementation has three stages: formation, roadmap, and performance. Formation focuses on building collaborative governance. Roadmap involves assessing the current situation and planning actions. Performance evaluates goal achievement and reports outcomes transparently [44]. This framework served as the conceptual basis for the context-specific model developed in this study.

Figure 3.

Imperatives and priorities in EcoDistricts protocol (adapted from [44]).

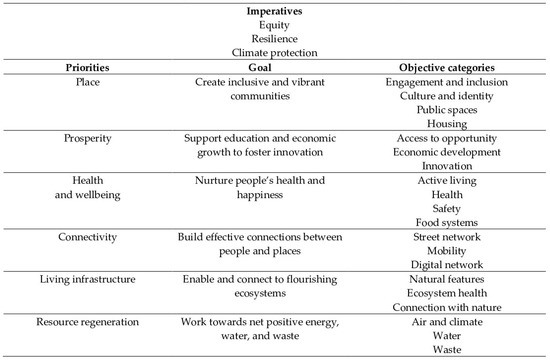

3.2. The Aim and Steps of the Study

The main aim of this research is to assess the sustainability of a neighborhood under the threat of transformation through a participatory, process-based approach and to develop place-based strategies for future action. The methodology is built on: (a) assessing sustainability using a context-sensitive framework informed by the EcoDistricts model, and (b) developing locally grounded strategies that respond to the needs of aging neighborhoods (Figure 4). This study focuses on a neighborhood experiencing “double aging”, referring to both its population and physical environment. Rather than applying an existing tool, the study introduces a new model—Context-Based Neighborhood Sustainability Assessment (CB-NSA)—inspired by EcoDistricts but shaped for the local context.

While most studies assess neighborhood sustainability based on outcomes, this article adopts a process-oriented approach to guide decision-making. Although aging-in-place literature often centers on housing, health, and mobility [79,80,81,82], few studies examine these issues holistically at the neighborhood scale. This study addresses that gap through a comprehensive, place-based sustainability model.

Figure 4.

Methodology and steps of the research.

3.3. Step 1: Determining Priorities

CB-NSA model draws on the EcoDistricts Protocol Version 1.3 to identify relevant sustainability priorities for the selected neighborhood [44]. Considering the characteristics of the aging context, three priority areas were selected: ‘place’, ‘health and wellbeing’, and ‘connectivity’. Other priorities—‘prosperity’, ‘living infrastructure’, and ‘resource regeneration’—were excluded as the area consists solely of existing residential units. The Priority Indicator Set provided in the EcoDistricts Protocol [44] was adapted to align with local dynamics for the context-based assessment model (Supplementary File S2).

The study proposes the following hypothesis:

H1.

The three EcoDistricts priorities—Place, Health & Wellbeing, and Connectivity—when locally adapted, provide an appropriate basis for assessing sustainability in double-aging neighborhoods.

3.4. Step 2: Context-Based Neighborhood Sustainability Assessment

To examine this hypothesis, the study adopts a mixed-methods approach, combining both quantitative and qualitative methods. In the sustainability assessment, alongside quantitative data, residents’ perspectives enable a more comprehensive analysis by allowing both data types to complement each other [83,84].

Data were collected through field observation, local authority base maps, GIS maps, and official statistics. AutoCAD 2021.3 was used for data calculations, and Adobe Photoshop 2021 for visualizing the data. Since the model follows a process-based approach rather than a score-based, the evaluation identified both sustainable and deficient aspects, with sustainability categorized as low, medium, or high.

In the qualitative research, due to the predominantly elderly population in the area, surveys were not considered appropriate. Instead, in-depth interviews were conducted. A total of 24 participants were purposively selected based on age and length of residence. Since IPA focuses on depth rather than breadth, this small sample allowed for idiographic, in-depth exploration [85]. Participants were reached through the snowball technique among volunteers matching the demographic criteria.

Prior to the interviews, ethical approval was obtained from the Research and Publication Ethics Committee of Bursa Uludağ University, Faculty of Science and Engineering, in the session dated 30 June 2025, with session number 2025-06, decision number 12. Informed consent was obtained, and interviews were conducted between 5 July and 5 August 2025, following ethical guidelines. The total duration was 24 h, with each session lasting 50–70 min. Interviews were audio recorded or, when not permitted, carefully noted. All data were transcribed and coded for advanced analysis.

3.4.1. In-Depth-Interview Structure

Thematic areas were defined based on three priorities and their 11 sub-categories: ‘place’, ‘health and wellbeing’, and ‘connectivity’. A total of 18 open-ended questions were asked during in-depth interviews (by category: general (2), place (8), health and wellbeing (5), connectivity (3)) (Supplementary File S2). The interview questions were broad and open-ended, encouraging participants to describe their experiences in their own terms. They opened discussion around key domains without imposing predetermined themes. This analytical tool is based on an approach that promotes the inclusion of the local community in sustainability assessments, aims to enhance the continuity and improvement of place and communities, supports co-creation in knowledge production, and enables residents to identify both sustainable and deficient aspects of their living environment [44,85,86,87].

3.4.2. Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis

To assess residents’ experiences related to neighborhood sustainability, Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis (IPA) was used. IPA focuses on understanding how individuals make sense of their lived experiences and the meanings they attach to them. Rooted in phenomenology, hermeneutics, and idiography, IPA enables an in-depth exploration of participants’ subjective experiences in specific contexts [85]. IPA is widely regarded as a qualitative research approach that places the participant’s perspective at the center of the research process [88].

The thematic analysis process followed Braun and Clarke’s six-phase model of familiarization, coding, theme development, review, definition and write-up, which enabled systematic interpretation of experiential narratives within a policy-relevant sustainability context [89]. Interview transcripts were reviewed line by line, and initial codes were developed based on meaning units extracted from participants’ expressions. These codes were then grouped to form broader themes that captured the experiential patterns of neighborhood life. The process involved iterative reading, constant comparison, and analytical memoing. The analysis is grounded in the idea that place gains meaning through people’s perceptions and experiences [90], and that research becomes a mutual learning process through community participation [86].

These patterns were then categorized under three key sustainability priorities—Place, Health & Wellbeing, and Connectivity—adapted from the EcoDistricts framework and contextualized for double-aging neighborhoods. The resulting themes structured the qualitative dimension of the Double Aging Sustainability Assessment Framework and informed the formulation of proposed actions in alignment with quantitative findings.

3.4.3. National and Local Urban Development Context of the Study Area

Urban development in Turkey has been heavily shaped by industrialization-induced migration since the 1950s, leading to rapid and often unplanned urbanization. Early legislative responses included the Land Development Law (1957) and the Property Ownership Act (1965), the latter triggering the transformation of low-rise housing into apartment blocks, though often neglecting green space and social infrastructure, resulting in long-term sustainability concerns [76,91].

From the 1980s onwards, neoliberal policies prompted urban expansion toward the peripheries, producing new settlements and infrastructure but also exacerbating environmental degradation. The 1999 Marmara Earthquake led to the National Earthquake Strategy and Action Plan (2012), which positioned urban renewal as a critical strategy [92]. As concrete building stock aged, the construction sector became central to economic development strategies [92]. The enactment of Law No. 6306 in 2012 accelerated transformation, aiming to renew risky structures. However, it drew criticism for favoring profit-oriented redevelopment over comprehensive sustainability principles [48,93,94].

The KENTGES Strategy Document (2010) addresses unplanned growth, migration, infrastructure gaps, disaster risk, climate change, and sustainable urban form [26]. Since 2007, the Turkish Green Building Council has promoted sustainable urban transformation, energy efficiency, and green building practices [28]. The SEEB-TR and SEEB-TR Neighborhood systems evaluate energy, water, materials, transport, and community, linking these to urban design and legislation through performance-based metrics [29]. While these efforts support sustainable development, there remains a need for tools that aid decision-making at the neighborhood scale during urban change.

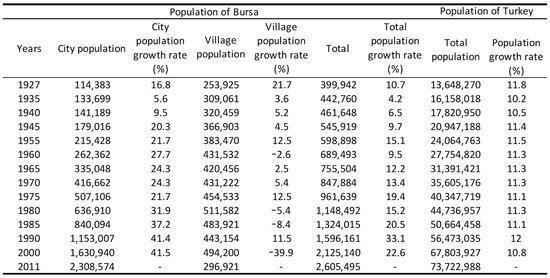

Bursa followed a similar trajectory. The establishment of Turkey’s first organized industrial zone in 1961 catalyzed rural-to-urban migration (Figure 5) [95,96]. Subsequent laws—such as the 1969 Cooperatives Law)—facilitated cooperative housing in the 1970s and 1980s, many of which later became targets under Law No. 6306 (Figure 6) [97,98], further supported by the 2013 Mortgage Law.

This growth, however, has often undermined environmental integrity, urban identity, and social cohesion by prioritizing the built environment over social sustainability [21,99]. Yet, neighborhoods like Kükürtlü in Bursa’s city center still retain sustainable qualities, though increasing structural vulnerability puts them under significant transformation pressure.

Figure 5.

Population change in Bursa and Turkey by year (adapted from [100]).

Figure 6.

Housing production statistics by district in Bursa (adapted from [101]).

3.4.4. Study Area

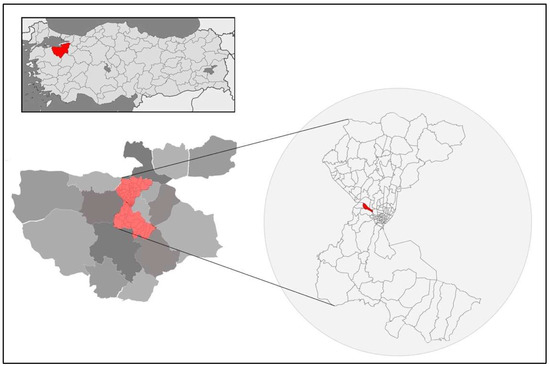

The study area is Kükürtlü District, located in the Osmangazi district of Bursa, the fourth largest city in Turkey (Figure 7). It has a population of 11,217 [102] and is situated 5 km from the city center.

Bursa lies within an active seismic zone, and frequent spatial changes have occurred due to legal regulations encouraging the transformation of risky buildings. Despite this rapid urban transformation, Kükürtlü has maintained its identity as one of the city’s first upper-income residential areas. However, due to the aging population and building stock, the neighborhood is under increasing pressure for redevelopment. For this reason, Kükürtlü, where the phenomenon of “double aging” (aging population and aging housing stock) is observed, was selected to assess sustainability in urban transformation processes.

Located near the city center, Kükürtlü District has historical roots dating back to the Byzantine era, known for its tombs, baths, and vineyard houses. Once a summer retreat, it became a prestigious residential area with detached houses and gardens from the 1940s, attracting upper-income groups [95,103].

Figure 7.

Location of the Kükürtlü District in Osmangazi Province, Bursa, Turkey (The image was taken from Bursa Metropolitan Municipality and elaborated by the authors).

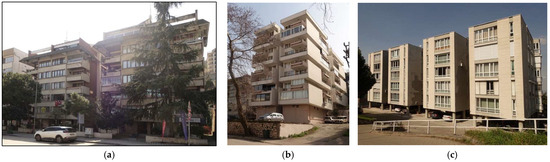

After the 1960s, industrialization led to the replacement of these homes with modern apartment blocks, shaping today’s high-quality residential character [104,105]. The current housing stock mainly consists of low-density apartments built between 1970–1985 (Figure 8), alongside historic structures, green spaces, and proximity to the 40-hectare Kültür Park (Figure 9).

Figure 8.

Existing housing fabric in Kükürtlü District (a) Hünkar Apartment (b) Aker Dublex Apartment (c) Urgancıoğlu Apartment.

Demographically, the neighborhood is defined by a rapidly aging population. The 65+ group dominates, and the 60–64 group is also sizable, indicating continued aging in coming years. Middle-aged residents (40–49) also maintain a moderate share (Figure 10) [102].

Figure 9.

Historical elements and green urban fabric in Kükürtlü District (a) Historical mausoleum and park (b) Historical mansion.

The neighborhood also experiences aging housing stock. Structurally, most buildings were built under the 1975 earthquake legislation and fall short of the updated 2018 regulation, requiring structural reinforcement [106]. Under Law No. 6306 on the Transformation of Areas Under Disaster Risk (2012), local authorities developed redevelopment plans favoring demolish-rebuild strategies, offering increased height and improved public spaces. To date, around 5% of the residential area has undergone parcel-based renewal following voluntary structural risk assessments.

Figure 10.

Kükürtlü District population distribution by age (adapted from [102]).

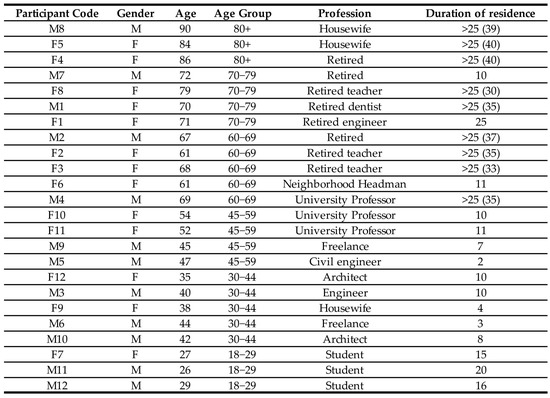

3.4.5. Study Sample and Respondents’ Profile

The sample was planned in line with qualitative and phenomenological research conventions. Phenomenological studies typically include 2–25 participants [88], and IPA also recommends working with relatively small and reasonably homogeneous samples to allow close examination of similarities and differences [85].

A target of 24 provided enough room to represent all major adult age groups while maintaining gender balance. Participants were drawn from the adult population; individuals under 18 were not included. The neighborhood’s age structure [102] (Figure 10) informed an initial proportional distribution across four groups (18–29, 30–44, 45–59, 60+), corresponding to roughly 3 people in the youngest group and around 7 in each of the others. Following international demographic practice, including the UN’s classification of individuals aged 60 and over as older persons [107], this threshold was used for the older cohort. Given the study’s focus on double-aging, older residents (60–69, 70–79, 80+), particularly those with at least ten years of residence, were intentionally oversampled to capture long-term, place-based experience. Data collection continued until no new themes emerged, and saturation indicated that 24 participants (n = 24) were sufficient. The final distribution is shown in Figure 11. Interviews were conducted within the neighborhood, at locations and times chosen by the participants.

Figure 11.

Respondent’s profile (processed by the authors).

3.5. Step 3: Evaluation Through Data Integration

To ensure a more robust and holistic sustainability assessment, this study integrated quantitative spatial analysis with qualitative insights from in-depth interviews. Rather than evaluating these data sources separately, a cross-comparison was conducted to identify where objective environmental indicators aligned or diverged from residents’ subjective experiences. The findings were synthesized under three priority areas—Place, Health & Wellbeing, and Connectivity—resulting in actionable strategies.

3.6. Step 4: Proposed Actions for Neighborhood Sustainability

Based on the evaluation, key action proposals have been outlined to guide the sustainable development of Kükürtlü District.

4. Results

4.1. Place Priority

In the model, the “Engagement and Inclusion” category promotes civic participation and inclusive decision-making (informed by EcoDistricts [44]). Voter turnout is high in both local (75%) and general (95%) elections (Table 1). Long-term residing participants (25+ years) report strong neighborly ties and frequent social interaction, often engaging in shared decisions on neighborhood matters (Supplementary Files S3 and S4—Table S1). In contrast, short-term residing participants (less than 5 years) have limited neighborly interaction (Supplementary File S4—Table S1).

Table 1.

Place priority—quantitative data assessment.

The “Culture and Identity” category focuses on preserving culturally significant areas and encouraging cultural participation [44]. Kükürtlü Neighborhood hosts 12 cultural heritage sites—nearly double that of Osmangazi—and has largely retained its cultural character (Table 1). It is mostly considered historic buildings and green areas key to neighborhood identity and emphasize the preservation (Supplementary File S3) (50%). One noted the irreplaceable value of wooden mansions and gardens, while another expressed concern that newcomers overlook local aesthetics and materials, weakening architectural identity (Supplementary Files S3 and S4—Table S2). Newer residing participants (less than 5 years) appear less informed about cultural values; one cited location, affordability, and safety as main reasons for choosing the area (Supplementary File S3 and S4—Table S2) (12%).

The “Public Space” category promotes accessible, inclusive, high-quality spaces for all [44]. All residences have access to at least one public space within 0.25 miles (100%) (Table 1). However, all participants—regardless of age or residency length—found these spaces inadequate (Supplementary File S3). Public spaces consist mainly of small parks and eateries, yet they are neither well-designed nor appealing, particularly for older adults. The neighborhood head noted long-term underinvestment, and an elderly participant highlighted that green front yards are unusable due to poor landscaping and lack of amenities (Supplementary Files S3 and S4—Table S3).

The “Housing” category aims to ensure that dwellings are affordable, well-maintained, and able to meet various living needs [44]. According to quantitative data, housing and transportation costs in the neighborhood are at an affordable level (35%) [108], and the housing occupancy rate is high (98%) [109].

Half of the dwellings allow residents to meet their daily needs within walking distance. However, the housing stock is predominantly composed of apartment-type buildings, and housing diversity is limited [110] (Table 1).

Regarding housing condition, most dwellings were built between 1970–1985 in accordance with the 1975 Earthquake Regulation. However, with the stricter criteria introduced by the 1998, 2007, and 2018 regulations, the buildings in this area do not comply with current regulations, and all require structural reinforcement [44,106].

Participants were asked whether they found their dwellings suitable for today’s conditions. They generally acknowledged that their homes were physically old but found their spatial qualities sufficient (76%). Newly built high-rise, small, and gardenless housing typologies were found incompatible with their lifestyles. Some participants stated that their buildings had architectural value and should be preserved (20%), while older participants did not want to relocate due to emotional attachment. Young participants with long-term residency were satisfied with their homes but also emphasized the need for improvements against earthquake risk. A new residing participant who purchased multiple homes for investment purposes supported transformation due to high maintenance costs and earthquake risk (Supplementary File S4—Table S4) (4%).

Although access to daily services around the dwellings was generally found adequate, some participants stated that service diversity was limited (Supplementary S4—Table S4) (56%).

4.2. Health and Wellbeing Priority

The “Active Living” category aims to enhance walkability and access to recreational spaces [44]. The neighborhood has a strong pedestrian infrastructure with a high Walk Score (91%) [111] and sidewalk ratio (90.35%) (Table 2). However, the variety of accessible public spaces is limited (Table 2), and recreational areas that do not fully meet user needs restrict active living according to some participants (Supplementary Files S3 and S4—Table S4) (Figure 12) (50%).

The “Health” category aims to ensure access to quality health services and support healthy environments [44]. Access to health services in the neighborhood is easy, and pedestrian and public transportation options are high (Table 2) (Figure 12); participants also confirm the ease of access (Supplementary Files S3 and S4—Table S5) (100%). Life expectancy meets the lower threshold (79.8 years) [112]. Air quality is good [113], and there are no brownfield sites in the area (Table 2).

Table 2.

Health and wellbeing priority—quantitative data assessment.

Table 2.

Health and wellbeing priority—quantitative data assessment.

| Indicators | Quantitative Data | Comments | Data | Sustainability Assessment ϒ | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L | M | H | ||||

| Active Living Category | ||||||

| Number of public indoor or outdoor recreation space in 0.25 mile (0.4 km) walk to dwelling units | 4 | Kiosk, local restaurant & café, children’s park, museum | Field observations, GIS and satellite maps | ✗ | ||

| Percentage of street length in the district with sidewalks on both sides | 90.35% | Field observations, municipal base maps | ✗ | |||

| The district’s Walk Score (Walk Score is an online platform that promotes walkable neighborhoods by assessing accessibility to nearby amenities, transport options, and distances.) | 91% | It classifies neighborhoods based on walkability as follows: 90–100 (Walker’s Paradise), 70–89 (Very Walkable), 50–69 (Somewhat Walkable), 25–49 (Car-dependent), and 0–24 (Car-dependent Walker’s Paradise Level: No car is needed for daily activities | [111] | ✗ | ||

| Health Category | ||||||

| Walk and Transit Scores of health facility locations (Transit Score is a patented tool for measuring a spot’s connection to public transit. The score works by evaluating the worth of accessible routes, prioritizing factors like service frequency, transit type, and the distance to stops [111]) | Bus stops (17) (serving 10–14 routes), taxi stands (10), minibus stops (5) Pharmacies (9), supermarkets (3), parks (2), food-beverage (25) in 400 m. | GIS and satellite maps | ✗ | |||

| Average life expectancy | 79.8 | (2023) min value: 79.7 EU average value: 84 | [112] | ✗ | ||

| Annual average air quality value * | SO2: 5 < 20 O3: 51 < 120 NO2: 37 < 40 | The limit values valid in Turkey and EU member states are taken as basis. | [113] | ✗ | ||

| Percentage of population living near an unrehabilitated brownfield or contaminated site | 0% | Field observations, municipal base maps | ✗ | |||

| Safety Category | ||||||

| Percentage of public space frontages visible from a street | 57% | Field observations, municipal base maps | ✗ | |||

| Annual composite index score of crimes against persons and property | Data not available in district scale | |||||

| Food Systems Category | ||||||

| Percentage of residential units within 0.5 mile (0.8 km) of fresh food outlets | 82% | GIS—satellite maps, municipal base maps | ✗ | |||

Note. *: SO2: Sulfur dioxide gas O3: Ozone gas NO2: Nitrogen dioxide gas. ϒ: Sustainability assessment levels L: Low M: Medium H: High.

4.3. Connectivity Priority

In the “Street Network” category, an inclusive circulation system supporting all transport modes is targeted [44]. Intersection density (Intersection density refers to the number of road intersections or junctions within a specific area. The higher the intersection density, the more route options it offers for pedestrians, cyclists, and drivers [114]) (106) meets the lower threshold. Signalized pedestrian crossings on main roads reach 75%, partially fulfilling the criteria. There is no regulation on bike sharing (Table 3). Participants generally find the street network adequate (92%). Elderly participants noted that crossings on main roads are limited and may pose risks (Supplementary File S4—Table S6).

The “Mobility” category targets safe, efficient, and multimodal transport [44]. There are six first/last mile options, though no bike or car sharing stations (Table 3). Participants noted that modal diversity supports daily mobility (Supplementary Files S3 and S4—Table S6) (100%).

The “Digital Network” category ensures public access to local government data [44]. Free internet is available in 45% of public spaces, and the area ranks V3 in digital governance [115]. A local tech hub offers internet to low-income users (Table 3). Most of the participants say there is no internet or they don’t know if it’s available in public spaces (63%); some report limited access only in one park and library (37%) [116].

Table 3.

Connectivity priority—quantitative data assessment.

Table 3.

Connectivity priority—quantitative data assessment.

| Indicators | Quantitative Data | Comments | Data | Sustainability Assessment ϒ | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L | M | H | ||||

| Street Network Category | ||||||

| Intersection density > 100 | 106 | Municipal base maps | ✗ | |||

| Percentage of arterial intersections with traffic-controlled crosswalks | 75% | Municipal base maps | ✗ | |||

| Percentage of total street length with bicycle sharing | 0% | GIS and satellite maps | ✗ | |||

| Mobility Category | ||||||

| Number of first and last mile (‘First and last mile’ options refer to how easily travelers access public transit stops and reach their final destinations, highlighting the need for convenient connections at both ends of a journey) options at major transit stops | 6 | Minibus (dolmuş) Bus Taxi Pedestrian path Scooter Bicycle | Field observations, GIS and satellite maps | ✗ | ||

| Number of bike and car share stations | 0 | GIS and satellite maps | ✗ | |||

| Digital Systems Category | ||||||

| Percentage of public spaces with free Wi-Fi | 45% | Parks (3), bus stop (1) | Field observations, municipal base maps [116] | ✗ | ||

| Regional e-government development | V3 | Country-based performance measurement (Turkey) (2024) Rating class: Very High EGDI ψ (VH, V3, V2, V1) High EGDI, Middle EGDI, Low EGDI | [115] | ✗ | ||

| Number of technology hubs for low-income residents to access the Internet | 1 | Urban park library (1) | GIS—satellite maps Municipal base maps | ✗ | ||

Note. ϒ: Sustainability assessment levels L: Low M: Medium H: High; ψ: EGDI: E-Government Development Index.

Figure 12.

Maps showing land use in Kükürtlü District (The image was taken from Bursa Metropolitan Municipality and elaborated by the authors).

5. Discussion

5.1. Place Priority

In the “Engagement and Inclusion” category, despite the quantitative findings indicating high participation in collective decision-making processes, the insights reveal that long-term residents develop strong neighborly ties and shared decision-making tendencies, whereas newcomers remain socially detached. Although participation and inclusiveness improve over time, sustainable efforts are needed to ensure social cohesion for all users. Individuals who feel a sense of belonging and community tend to have higher quality of life [117], better physical and mental health, and stronger social relationships [117,118].

“Cultural identity” in Kükürtlü is shaped by both spatial elements and social belonging. Historical and cultural heritage assets strengthen the sense of place and livability. For long-term residents, childhood memories and family experiences foster emotional attachment and long-term place dependence [118].

However, participants noted that newer residents often disregard the architectural identity, creating a disconnect between the physical and social structure. Lewicka [119] shows that newcomers’ limited familiarity with local cultural memory reduces their motivation to preserve neighborhood identity, which supports the findings of this study. Preserving architectural character contributes to neighborhood sustainability [119,120]. Some newcomers form only temporary, functional ties to the area, which may weaken collective identity. To support cultural continuity, community-generated initiatives—such as local memory maps or cultural walking routes highlighting heritage buildings and stories—could help strengthen awareness and identity [119].

In the “Public Space” category, GIS analysis showed that 100% of residential units are located within 400 m of public green spaces, and the neighborhood also has a high concentration of park areas. However, the lack of accessible and socially engaging spaces for older adults poses a risk of exclusion. Access to nearby green areas plays a key role in both psychological wellbeing and social integration for elderly residents [119]. Inadequate quality and relevance of social spaces also lead younger users to seek alternatives elsewhere, weakening their spatial attachment. As highlighted in Gehl’s seminal work, the effectiveness of public spaces depends not on their numerical abundance but on their capacity to support everyday encounters and social interaction, which aligns with these findings [121].

In the “Housing” category, the existing housing stock does not meet current earthquake standards, indicating a lack of structural resilience—a key aspect of sustainable housing [122]. While quantitative assessment flagged most buildings as structurally outdated, strong emotional and cultural ties foster spatial attachment that outweighs structural concerns. Standardized housing models are seen as incompatible with local lifestyles, underlining the need to consider socio-cultural patterns alongside physical design [123]. Although current demand for transformation is low, a small but growing group of newcomers—relocating for affordable housing or investment—view redevelopment positively. Unlike long-term residents, these users tend to form weaker emotional ties to the neighborhood, instead approaching the area with pragmatic intentions. While their numbers remain limited, they signal early signs of potential gentrification. As indicated in Moes and Boreas, newcomers in transitional neighborhoods may disregard or unintentionally erode architectural identity, which is consistent with this study’s findings [124].

The housing fabric retains architectural identity, but structural weaknesses call for in situ renovation—combining retrofitting and refurbishment—rather than demolition. EU policy trends similarly prioritize renovation-based strategies, especially in Eastern Europe, where mid-20th-century housing is commonly renewed through renovation [125]. These approaches address structural upgrading and environmental sustainability [126,127].

Given the high proportion of elderly residents, in-place renovation is vital to maintain social ties and community continuity. The World Health Organization (WHO)’s “age-friendly cities” model and the aging-in-place approach advocate for improved housing accessibility, safety, and quality [52,53,81]. Thus, local housing should support sustainable aging in place. In Eastern Europe, where new construction is limited, in situ renovation aligned with social and cultural continuity is prioritized [128], which parallels this study’s finding that residents prefer staying in place due to strong social ties and a desire to preserve neighborhood cultural values. Many cities in Europe and East Asian countries such as Japan have already integrated age-friendly principles into urban design due to demographic shifts [129,130,131].

Despite physical decline, strong social cohesion and spatial attachment indicate high social sustainability in an area. Therefore, housing strategies should integrate physical interventions with efforts to preserve the existing social fabric.

5.2. Health and Wellbeing Priority

In the Active Living scope, according to the quantitative data, the neighborhood shows very high walkability, with a Walk Score of 91 and 90.35% of streets having sidewalks on both sides. The qualitative findings similarly indicate that residents generally perceive the area as walkable. At the same time, the lack of well-designed spaces for social and daily activities is perceived to negatively affect walkability, as residents report that these deficiencies limit opportunities for active, everyday mobility. Spatial improvements are needed to support active aging and foster belonging among youth.

In terms of “Health”, quantitative indicators show high walk and transit scores, moderate life expectancy, and high air quality. Consistently, qualitative themes highlight good access to healthcare, noting that proximity to health services supports routine check-ups, social interaction, and continuity in daily life. Environments encouraging physical activity and social ties can improve life expectancy [132,133,134].

For “Safety”, the quantitative data show that the visibility of public spaces from streets is moderate (57%), whereas qualitative themes indicate that the neighborhood is generally perceived as highly safe, with only a few vacant houses posing localized safety risks. This perception is strongly supported by recent literature emphasizing the detrimental effects of neglected properties on both neighborhood safety and mental health [135]. The reactivation of these vacant units could help rebuild social ties and safety.

“Food systems” quantitative data show that 82% of residential units have accessible fresh food outlets, whereas qualitative themes reveal that shopping from local fresh food outlets is mostly a habit among older residents, alongside small-scale home gardening practices observed in the neighborhood. Urban gardening can foster intergenerational interaction and support community-based food production [136,137,138].

The neighborhood supports daily life continuity through access to healthcare, food, and safety. Spatial strategies that promote active lifestyles and social engagement can further strengthen overall wellbeing.

5.3. Connectivity Priority

In terms of the “Street Network”, quantitative data indicate that 75% of crossings are traffic-controlled and that the intersection density (106) approaches the threshold value, whereas qualitative themes highlight the walking difficulties experienced by older residents. Elderly pedestrian access should be enhanced, and youth engagement encouraged via bike-sharing systems. For “Mobility”, the quantitative data show a wide variety of first- and last-mile options, and the qualitative themes similarly emphasize the availability of diverse transportation choices in the neighborhood. Multimodal transport increases comfort, supports physical activity, and reduces car dependency by improving access to opportunities [139]. Despite the strong digital infrastructure indicated in the quantitative data, gaps in both awareness and the use of digital systems persist—particularly among older adults. Their inclusion should be promoted alongside the design of age-inclusive public spaces. Connectivity-oriented approaches boost comfort, social interaction, and urban integration [140]. Ensuring accessibility across all demographics is key to fostering participation and social cohesion.

Kükürtlü District has strong social ties and cultural identity, indicating high potential for social sustainability. However, limited structural resilience and public spaces call for multi-dimensional interventions. In-place improvement, age-in-place, and cultural continuity are key to long-term resilience and inclusivity. These findings not only inform Kükürtlü’s future but also resonate with challenges faced by aging urban areas in Eastern Europe, southern Germany, and East and Southeast Asia [128,130,131,141].

The findings support the hypothesis that the EcoDistricts priorities—place, health and wellbeing, and connectivity—are relevant for assessing sustainability in double-aging neighborhoods and reflect residents’ lived experiences. Qualitative and quantitative data confirm these priorities as core dimensions for a context-sensitive sustainability framework.

To enhance transparency and demonstrate how a holistic interpretation was developed by integrating spatial indicators with residents’ lived experiences, a comparative matrix was constructed (Figure 13). This matrix allows readers to trace how sustainability priorities and resulting strategies were informed by both objective data and experiential insights.

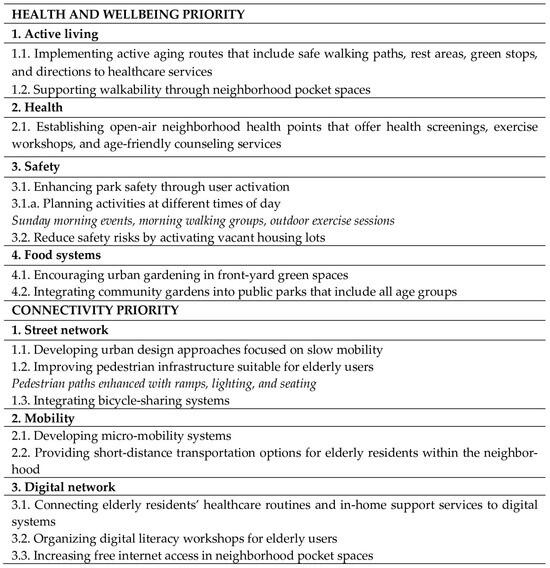

Following the strategic insights gained from the sustainability assessment matrix, specific actions were formulated for the Kükürtlü District’s sustainable development. These proposed actions are presented in Figure 14.

Figure 13.

Integrated Sustainability Assessment Matrix: Cross-comparison of quantitative indicators, qualitative themes, and resulting strategies.

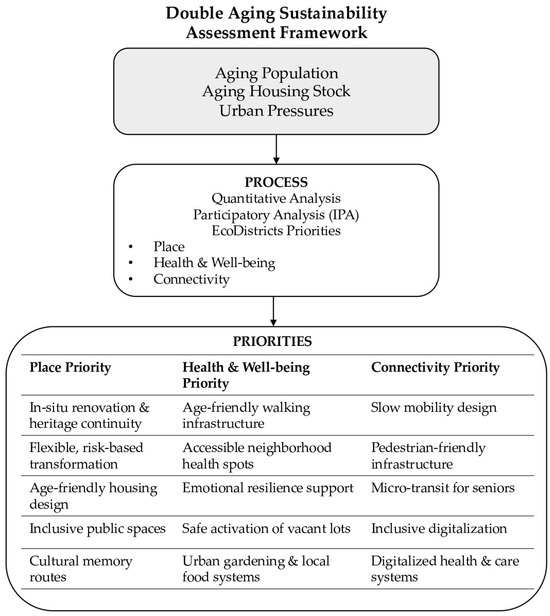

Although grounded in the specific context of Kükürtlü, the framework proposed in this study (Figure 15) provides strategic guidance for sustainability assessment in similarly aging neighborhoods in Eastern Europe as well as East and Southeast Asian countries facing double-aging challenges.

Figure 14.

Proposed actions for Kükürtlü District’s sustainability development.

Recent studies further support the global relevance of the double-aging concept. For instance, urban neighborhoods in Beijing have been analyzed using big data techniques to identify aging populations and outdated housing stocks for targeted retrofitting [56]. In Tokyo, high-rise residential buildings present dual challenges of physical decay and demographic shift [55]. Similarly, Hong Kong’s ‘double smart’ approach suggests integrated smart aging and smart city solutions to mitigate double-aging effects [142]. Moreover, in Eastern Europe, depopulation and elderly institutionalization in shrinking towns illustrate similar structural and demographic vulnerabilities [143]. These cases illustrate that the CB-NSA framework’s priorities—especially place-based strategies, active aging, intergenerational participation and local governance—hold relevance across varied socio-spatial settings.

5.4. Study Limitations

This study presents several limitations. The qualitative data is based on self-reported perceptions, which may be influenced by memory bias or personal subjectivity. The spatial analysis relies on municipal datasets, which may not reflect recent or real-time changes in infrastructure and services. Quantitative assessments could be further expanded through a broader, large-scale study.

The interview sample consisted of 24 participants, selected through purposive sampling, with a greater proportion of elderly and long-term residents to reflect the double-aging neighborhood context. However, this may not fully represent the diversity of the area, particularly newer residents.

Figure 15.

Double Aging Sustainability Assessment Framework.

The results and proposed strategies are context-specific and may not be directly transferable to other urban settings without adaptation. Nevertheless, the framework offers valuable insights for developing localized strategies in similar double-aging neighborhoods and contributes by providing a context-based approach that may inform adaptations in different urban settings, depending on local priorities.

Finally, the study captures a specific moment in time and does not account for evolving dynamics such as migration trends, demographic shifts, or policy changes.

6. Conclusions

As cities evolve under socio-economic pressures, some approaches focus on enhancing existing structures, while others adopt demolition–rebuild strategies that risk identity loss and urban discontinuity. This has increased interest in fabric-sensitive strategies and sustainability assessment tools.

The evaluation of a double-aging neighborhood reveals that sustainable development requires both physical improvements and preservation of social and cultural sustainability. Thus, development should be guided by inclusive and age-in-place approaches. This study develops a context-based sustainability assessment model, inspired by the EcoDistricts framework, to support informed decision-making in neighborhood transformation. It identifies place-based priorities and allows flexible criteria adaptation to local conditions, making it applicable in various geographies and contexts.

By integrating qualitative methods, the framework encourages learning from lived experiences and participation throughout the assessment process, offering a more holistic perspective. The study emphasizes the need for balanced attention to physical renewal, community continuity, and socio-cultural sustainability. The place-based proposals aim to guide strategy and roadmap development, encouraging collaboration with local governments and stakeholders under to promote inclusive, resilient urban development aligned with SDG 11.

In practical terms, the findings can inform housing policy reforms, guide local governments in regeneration projects, and support elderly residents’ wellbeing through age-sensitive design strategies. Additionally, while the CB-NSA model is context-based, future studies could explore its potential for scalability and adaptation in other double-aging neighborhoods across different global settings. This would allow testing its adaptability beyond Kükürtlü’s specific conditions—seismic-related structural vulnerabilities and the need for aging in place—and support its broader application.

Although the CB-NSA model was developed in the specific context of Kükürtlü, shaped by Turkey’s urban regulations and seismic risks, its structure and core priorities show potential for adaptation to other geographies facing double aging challenges. Neighborhoods in Eastern Europe and East and South East Asia, for instance, share similar challenges in terms of aging populations, vulnerable mid-20th century housing stock, seismic concerns, cultural continuity, and social fragmentation.

The model’s three priorities—Place, Health & Wellbeing, and Connectivity—within the EcoDistrict-based model—align with global sustainability objectives such as WHO’s Age-Friendly Cities initiative and SDG 11. Strategies like in situ retrofitting, walkability improvements, and participatory governance can be recalibrated for diverse legal, economic, and cultural settings.

Moreover, the CB-NSA framework offers insights not only for spatial planning but also for housing policy reforms (e.g., aging-in-place incentives), public health interventions (e.g., community clinics), and community-based governance platforms. Future research should explore its applicability across different governance systems and scales.

Place priority was found to be most strongly connected to residents’ experiences, suggesting future studies should further detail this dimension for a more comprehensive sustainability assessment.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/buildings15234357/s1, Supplementary File S1: Priority indicators set; Supplementary File S2: In-depth-interview questionnaire; Supplementary File S3: In-depth-interviews; Supplementary File S4: Selected quotes from interviews—Table S1: Engagement-inclusion; Table S2: Culture-identity; Table S3: Public spaces; Table S4: Housing; Table S5: Active living, health, safety and food systems; Table S6: Street network, mobility.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.T. and T.V.A.; methodology, H.T.; validation, H.T. and T.V.A.; formal analysis, H.T.; investigation, H.T. and T.V.A.; resources, H.T. and T.V.A.; data curation, H.T. and T.V.A.; writing—original draft preparation, H.T.; writing—review and editing, H.T. and T.V.A.; visualization, H.T.; supervision, T.V.A.; project administration, T.V.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

All subjects provided their informed consent for inclusion before they participated in this study. This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and the protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Bursa Uludağ University Research and Publication (30 June 2025, Session Number 2025-06, Decision Number-12).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available within the article. No supplementary datasets were generated or analyzed.

Acknowledgments

The authors used AI-assisted tools (such as ChatGPT 4o) to improve the language structure of this manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| KENTGES | Urban Development Strategy and Action Plan |

| SEEB-TR | Sustainable Building Assessment System |

| YeS-TR | National Green Certificate System |

| B.E.S.T | Ecological and Sustainable Design |

| SDG | Sustainable Development Goal |

| BREEAM | Building Research Establishment Environmental Assessment Method |

| CASBEE-UD | Comprehensive Assessment for Building Environmental Efficiency in Urban Districts |

| UNIDO | United Nations Industrial Development Organization |

| NSA | Neighborhood Sustainability Assessment |

| LEED-ND | Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design-Neighborhood |

| ECC | Earth Craft Communities |

| QSAS | Qatar Sustainability Assessment System |

| GNI | Green Neighborhood Index |

| HQE2R | High Environmental Quality for Urban District Rehabilitation |

| US | United States |

| UK | United Kingdom |

| EU | European Union |

| SCR | Sustainable Community Rating |

| SPeAR | Sustainable Project Appraisal Routine |

| OPL | One Planet Living |

| INDI | Indicators impact model |

| ENVI | Environment model |

| ASCOT | Assessment of Sustainable Construction & Technology Cost |

| VicUrban | Victorian Urban Development Authority |

| IPA | Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis |

| CNT | Center for Neighborhood Technology |

| GIS | Geographical Information Systems |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| CB-NSA | Context-Based Neighborhood Sustainability Assessment |

Appendix A

Figure A1.

Comparison of the NSA tools (modified from [42,43,44,45,46,47,72]).

References

- United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs—Population Division. World Population Prospects 2024: Summary of Results; United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs—Population Division: New York, NY, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. Sustainable Development Goals 11 Make Cities and Human Settlements Inclusive, Safe, Resilient and Sustainable. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/goals/goal11#targets_and_indicators%0D%0A (accessed on 2 August 2025).

- Yeh, A.G.-O.; Chen, Z. From Cities to Super Mega City Regions in China in a New Wave of Urbanisation and Economic Transition: Issues and Challenges. Urban Stud. 2020, 57, 636–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kala, K.; Bolia, N.B. Sushil Effects of Socio-Economic Factors on Quantity and Type of Municipal Solid Waste. Manag. Environ. Qual. An Int. J. 2020, 31, 877–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, K.; Huo, H.; Zhang, Q. Urban Air Pollution in China: Current Status, Characteristics, and Progress. Annu. Rev. Energy Environ. 2002, 27, 397–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, R.; Li, B.; Zhou, T.; Wanatowski, D.; Piroozfar, P. An Empirical Study of Perceptions towards Construction and Demolition Waste Recycling and Reuse in China. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2017, 126, 86–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.L.; Zhao, B.; Ding, L.L.; Miao, Z. Government Intervention, Market Development, and Pollution Emission Efficiency: Evidence from China. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 757, 143738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thorns, D.C. Suburbia (Sociology and the Modern World); MacGibbon and Kee: London, UK, 1972; ISBN 9780261632615. [Google Scholar]

- Palen, J.J. The Suburbs; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1995; ISBN 0070481288/9780070481282. [Google Scholar]

- Beauregard, R.A. Voices of Decline: The Postwar Fate of U.S. Cities; Routledge: London, UK, 2003; ISBN 9780415932387. [Google Scholar]

- Bourne, L.S. Reinventing the Suburbs: Old Myths and New Realities. Prog. Plann. 1996, 46, 163–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S. A Comparative Study of Suburbanization in United States and China. J. Geogr. Geol. 2014, 6, 132–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pallagst, K.M. Shrinking Cities in the United States of America. In The Future of Shrinking Cities: Problems, Patterns and Strategies of Urban Transformation in a Global Context; Institute of Urban and Regional Development: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2009; pp. 81–88. [Google Scholar]

- Arellano Ramos, B.; Roca Cladera, J. The Urban Sprawl: A Planetary Growth Process?: An Overview of USA, Mexico and Spain. In Proceedings of the 06to. Congreso Internacional Ciudad y Territorio, Virtual, 5–7 October 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitt, J. Gentrification in Islington; Barnsbury Peoples Forum: London, UK, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter, J.; Lees, L. Gentrification in New York, London and Paris: An International Comparison. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 1995, 19, 286–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rérat, P.; Söderström, O.; Piguet, E. Guest Editorial New Forms of Gentrification: Issues and Debates. Popul. Space Place 2010, 16, 335–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. World Population Ageing 2019: Highlights; United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Şisman, A.; Kibaroğlu, D. Dünyada ve Türkiye’de Kentsel Dönüşüm Uygulamaları (Urban Transformation Practices in the World and in Turkey). In Proceedings of the TMMOB Chamber of Surveying and Cadastre Engineers 12th Turkish Scientific and Technical Congress on Mapping, Ankara, Turkey, 11–15 May 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Görgülü, Z. Kentsel Dönüşüm ve Ülkemiz (Urban Transformation and Our Country). In Proceedings of the TMMOB İzmir Urban Symposium, Izmir, Turkey, 8–10 January 2009; pp. 767–780. [Google Scholar]

- Keşoğlu, M. Kentsel Kimlik Bağlaminda Fikirtepe Kentsel Dönüşüm Projesinin Analizi (Analysis of the Fikirtepe Urban Transformation Project in the Context of Urban Identity). Master’s Thesis, Beykent University, Istanbul, Turkey, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Ulu, A.; Karakoç, İ. The Impact of Urban Change on Urban Identity. Planlama 2004, 3, 59–66. [Google Scholar]

- Heidari, N. The Challenge of Changing Identity in Urban Transformation Process: Kagithane Case. Master’s Thesis, Istanbul Technical University, Istanbul, Turkey, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Keles, R. The Quality of Life and the Environment. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2012, 35, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Tekeli, İ. Modernleşme Sürecinde Kent Planlamasının Işlevi (The Function of Urban Planning in the Modernization Process). Planlama 2000, 3–14. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Public Works and Settlement. KENTGES Bütünleşik Kentsel Gelişme Stratejisi ve Eylem Planı 2010–2023 (KENTGES Integrated Urban Development Strategy and Action Plan 2010–2023); Ministry of Public Works and Settlement: Ankara, Turkey, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- YeS-TR Sertifikası Türkiye’nin Yeşil Bina Sistemi (YeS-TR Certificate Turkey’s Green Building System). Available online: https://www.yes-tr.com/ (accessed on 11 August 2025).

- Turkish Green Building Council. ÇEDBİK. Available online: https://www.cedbik.org/kurumsal (accessed on 24 July 2025).

- Ergönül, S.; Olgun, İ.; Tekin, Ç. (Eds.) Kentsel Mekana Yeşil Yaklaşımlar (Green Approaches to Urban Space); Mimar Sinan Güzel Sanatlar University: Istanbul, Turkey, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Devuyst, D.; Hens, L.; de Lannoy, W. How Green Is the City?: Sustainability Assessment and the Management of Urban Environments; Columbia University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2001; ISBN 9780231118033. [Google Scholar]

- Gibson, B.; Hassan, S.; Tansey, J. Sustainability Assessment—Criteria and Processes; Routledge: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Ness, B.; Urbel-Piirsalu, E.; Anderberg, S.; Olsson, L. Categorising Tools for Sustainability Assessment. Ecol. Econ. 2007, 60, 498–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pope, J. What’s so Special about Sustainability Assessment? J. Environ. Assess. Policy Manag. 2006, 8, 5–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bond, A.; Morrison-Saunders, A.; Howitt, R. (Eds.) Sustainability Assessment: Pluralism, Practice and Progress; Routledge: London, UK, 2013; ISBN 0415598486. [Google Scholar]

- Waas, T.; Hugé, J.; Verbruggen, A.; Wright, T. Sustainable Development: A Bird’s Eye View. Sustainability 2011, 3, 1637–1661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blum, A. HQE2R-Research and Demonstration for Assessing Sustainable Neighbourhood Development. In Sustainable Urban Development Volume 2: The Environmental Assessment Methods; Routledge: London, UK, 2007; p. 412. [Google Scholar]

- Hurley, J.; Horne, R. Review and Analysis of Tools for the Implementation and Assessment of Sustainable Urban Development. In Proceedings of the 2006 Environmental Institute of Australia and New Zealand Conference, Adelaide, Australia, 17–20 September 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Choguill, C.L. Developing Sustainable Neighbourhoods. Habitat Int. 2008, 32, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharifi, A.; Murayama, A. A Critical Review of Seven Selected Neighborhood Sustainability Assessment Tools. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2013, 38, 73–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blum, A. HQE2R-Sustainable Renovation of Buildings for Sustsianable Neighborhoods-Global Methodology. In Proceedings of the Sustainable Building Conference 2002 (SB 2002), Oslo, Norway, 23–25 September 2002. [Google Scholar]

- LEED v4 Reference Guide for Neighborhood Development. Available online: http://www.usgbc.org/guide/nd (accessed on 10 August 2025).

- BRE Global. BREEAM Communities Techincal Manual; BRE Global: Bricket Wood, UK, 2009; pp. 1–354. [Google Scholar]

- Institute for Building and Energy Conservaiton (IBEC). CASBEE for Urban Development (2007 Edition); Institute for Building and Energy Conservaiton (IBEC): Tokyo, Japan, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- EcoDistricts. EcoDistricts Protocol, Version 1.3; The Standard for Urban and Community Development: Portland, OR, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Cole, R.J. Building Environmental Assessment Methods: Redefining Intentions and Roles. Build. Res. Inf. 2005, 33, 455–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, A.; Pearl, D.S. Rethinking Sustainability Frameworks in Neighbourhood Projects: A Process-Based Approach. Build. Res. Inf. 2018, 46, 513–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, J.; Cole, R.J. Theoretical Underpinnings of Regenerative Sustainability. Build. Res. Inf. 2015, 43, 133–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutlu Kılıç, E. Urban Regeneration under Neoliberal Policy in Turkey and the Meaning of Oral History of Urban Space: The Case of İzmir-Kadifekale Urban Renewal Project. Ph.D. Thesis, Dokuz Eylül University, Izmir, Turkey, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Akkar, Z.M. Kentsel Dönüșüm Üzerine Batı’daki Kavramlar, Tanımlar, Süreçler ve Türkiye (Concepts, Definitions, Processes on Urban Transformation in the West and Türkiye). J. Plan. 2020, 36, 29–38. [Google Scholar]

- Power, A. Does Demolition or Refurbishment of Old and Inefficient Homes Help to Increase Our Environmental, Social and Economic Viability? Energy Policy 2008, 36, 4487–4501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tweed, C.; Sutherland, M. Built Cultural Heritage and Sustainable Urban Development. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2007, 83, 62–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Global Age-Friendly Cities: A Guide; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2007; ISBN 9241547308. [Google Scholar]

- Qian, Q.K.; Ho, W.K.O.; Jayantha, W.M.; Chan, E.H.W.; Xu, Y. Aging-in-Place and Home Modifications for Urban Regeneration. Land 2022, 11, 1956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Hoof, J.; Dikken, J.; Buttiġieġ, S.C.; van den Hoven, R.F.M.; Kroon, E.; Marston, H.R. Age-Friendly Cities in the Netherlands: An Explorative Study of Facilitators and Hindrances in the Built Environment and Ageism in Design. Indoor Built Environ. 2020, 29, 417–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirai, T. “Double Ageing” in the High-Rise Residential Buildings of Tokyo. Urban Plan. 2022, 7, 313–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, F.; Zheng, H.; Qin, B. Using Multi-Source Big Data to Identify “Double-Aging” Neighborhoods for Urban Retrofitting: A Case Study of Beijing. Appl. Geogr. 2025, 180, 103658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fullilove, M.T. Root Shock How Tearing Up City Neighborhoods Hurts America, and What We Can Do About It; New Village Press: New York, NY, USA, 2016; ISBN 9781613320204. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, C. The Effect of Urban Renewal on Fragmented Social and Political Engagement in Urban Environments. J. Urban Aff. 2018, 41, 503–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehanna, W.A.E.-H.; Mehanna, W.A.E.-H. Urban Renewal for Traditional Commercial Streets at the Historical Centers of Cities. Alexandria Eng. J. 2019, 58, 1127–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Asmar, J.-P.; Ebohon, J.O.; Taki, A. Bottom-up Approach to Sustainable Urban Development in Lebanon: The Case of Zouk Mosbeh. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2012, 2, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwok, A.H.; Paton, D.; Becker, J.; Hudson-Doyle, E.E.; Johnston, D. A Bottom-up Approach to Developing a Neighbourhood-Based Resilience Measurement Framework. Disaster Prev. Manag. An Int. J. 2018, 27, 255–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomson, C.S.; El-Haram, M.A.; Hardcastle, C. Managing Knowledge of Urban Sustainability Assessment. Proc. Inst. Civ. Eng.—Eng. Sustain. 2009, 162, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, L. There Goes the Hood: Views of Gentrification from the Ground Up; Temple University Press: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2006; ISBN 978-1592134373. [Google Scholar]

- Sixsmith, A.; Sixsmith, J. Ageing in Place in the United Kingdom. Ageing Int. 2008, 32, 219–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pipa, H.; de Brito, J.; Oliveira Cruz, C. Sustainable Rehabilitation of Historical Urban Areas: Portuguese Case of the Urban Rehabilitation Societies. J. Urban Plan. Dev. 2017, 143, 05016011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galster, G. On the Nature of Neighbourhood. Urban Stud. 2001, 38, 2111–2124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sala Benites, H.; Osmond, P.; Rossi, A.M.G. Developing Low-Carbon Communities with LEED-ND and Climate Tools and Policies in São Paulo, Brazil. J. Urban Plan. Dev. 2020, 146, 04019025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sparshott, P.J.; Darchen, S.; Stjohn, D. Do Sustainability Rating Tools Deliver the Best Outcomes in Master Planned Urban Infill Projects? City to the Lake Experience. Aust. Plan. 2018, 55, 84–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]