The Protection of Cultural Heritage in Poland in the Process of Enhancing the Energy Performance of Historic Buildings: An Analysis of Recent Strategic Policy Documents of the European Union and Poland (2005–2025)

Abstract

1. Introduction

“An immovable or movable object, or a group thereof, being a work of human activity or related to human action, constituting evidence of a bygone era or event, the preservation of which is in the public interest due to its historical, artistic, or scientific value”[7]

2. Materials and Methods

- In 2005, Poland, as a new member of the European Union, became obligated to implement EU energy and climate regulations;

- The year 2025 marks the planning horizon for current national and EU strategies and policy frameworks in the field of building renovation.

2.1. Source Materials

- EU-funded research and demonstration projects on heritage energy efficiency: Climate for Culture [12], EFFESUS—Energy Efficiency for EU Historic Districts’ Sustainability [13], RIBuild—Robust Internal Thermal Insulation of Historic Buildings [14], Protection of Cultural Heritage Objects with Multifunctional Advanced Materials (Nano-Heritage, 282992) [15], Climate2Preserv [16];

- Polish strategic documents: The Energy Policy of Poland until 2030 and 2040 (Polityka Energetyczna Polski do 2030 roku (PEP2030) [19], Polityka Energetyczna Polski do 2040 roku (PEP2040) [11]), the National Energy and Climate Plan (Krajowy plan na rzecz Energii i Klimatu na lata 2021–2030 (KPEiK 2019)) [10], Long-Term Building Renovation Strategy (Długoterminowa Strategia Renowacji Budynków (DSRB 2022)) [20], National Energy Efficiency Action Plan (Krajowy Plan Działań dotyczący efektywności energetycznej (KPDEE 2017)) [21], the National Programme for the Protection of Monuments (Krajowy Program Ochrony Zabytków (KPOZ)) [22], and the Guidelines of the General Conservator of Monuments (Wytyczne Generalnego Konserwatora Zabytków (WGKZt, WGKZf)) (2020) [23,24];

- Scientific and institutional literature: Academic articles and critical studies on the thermal modernisation of historic buildings, climate adaptation, and sustainable renovation methods; institutional reports from the National Heritage Board of Poland (Narodowy Instytut Dziedzictwa (NID)), the Supreme Audit Office (Najwyższa Izba Kontroli (NIK)), and reports of the European Commission and non-governmental organisations such as Europa Nostra.

2.2. Classification Criteria

- Level of regulation: European vs. national;

- Nature of the document: legally binding acts (directives, laws, resolutions) vs. soft-law strategic or advisory documents;

- Scope of impact on heritage: general regulations (applicable to all buildings) vs. heritage-specific measures;

- Implementation instruments: financial programmes, operational plans, and conservation guidelines.

2.3. Analytical Methodology

- Critical content analysis—identifying provisions addressing heritage protection, energy efficiency, and their interrelations;

- Comparative analysis—juxtaposing EU and Polish strategic documents in tabular form, examining objectives, interconnections, and implementation mechanisms;

- Case studies—analysing selected examples of good and poor practices from Poland and other EU Member States (e.g., adaptive reuse projects implemented under the Renovation Wave and the effects of Poland’s Clean Air Programme (Program Czyste Powietrze) [25].

2.4. Research Approach and Limitations

- The National Heritage Board of Poland (NID)—number of heritage buildings subject to renovation and modernisation;

- The General Conservator of Monuments (Generalny Konserwator Zabytków (GKZ))—number of conservations preservation permits and recommendations issued for energy retrofitting projects;

- The National Fund for Environmental Protection and Water Management (Narodowy Fundusz Ochrony Środowiska i Gospodarki Wodnej (NFOŚiGW))—data on projects financed under programmes such as Clean Air (Czyste Powietrze), Thermomodernisation Plus (Termomodernizacja Plus), and other initiatives supporting energy performance improvement.

- The National Heritage Board of Poland (Narodowy Instytut Dziedzictwa (NID))—open database of protected monuments and conservation programmes;

- The Ministry of Culture and National Heritage (Ministerstwo Kultury i Dziedzictwa Narodowego (MKiDN))—publicly accessible policy and legal documents through the ISAP and Dziennik Ustaw systems;

- The National Fund for Environmental Protection and Water Management (Narodowy Fundusz Ochrony Środowiska i Gospodarki Wodnej (NFOŚiGW)—open database of funded energy-efficiency projects and climate programmes;

- Supplementary EU-level data were obtained from EUR-Lex, Eurostat, and European Commission policy databases.

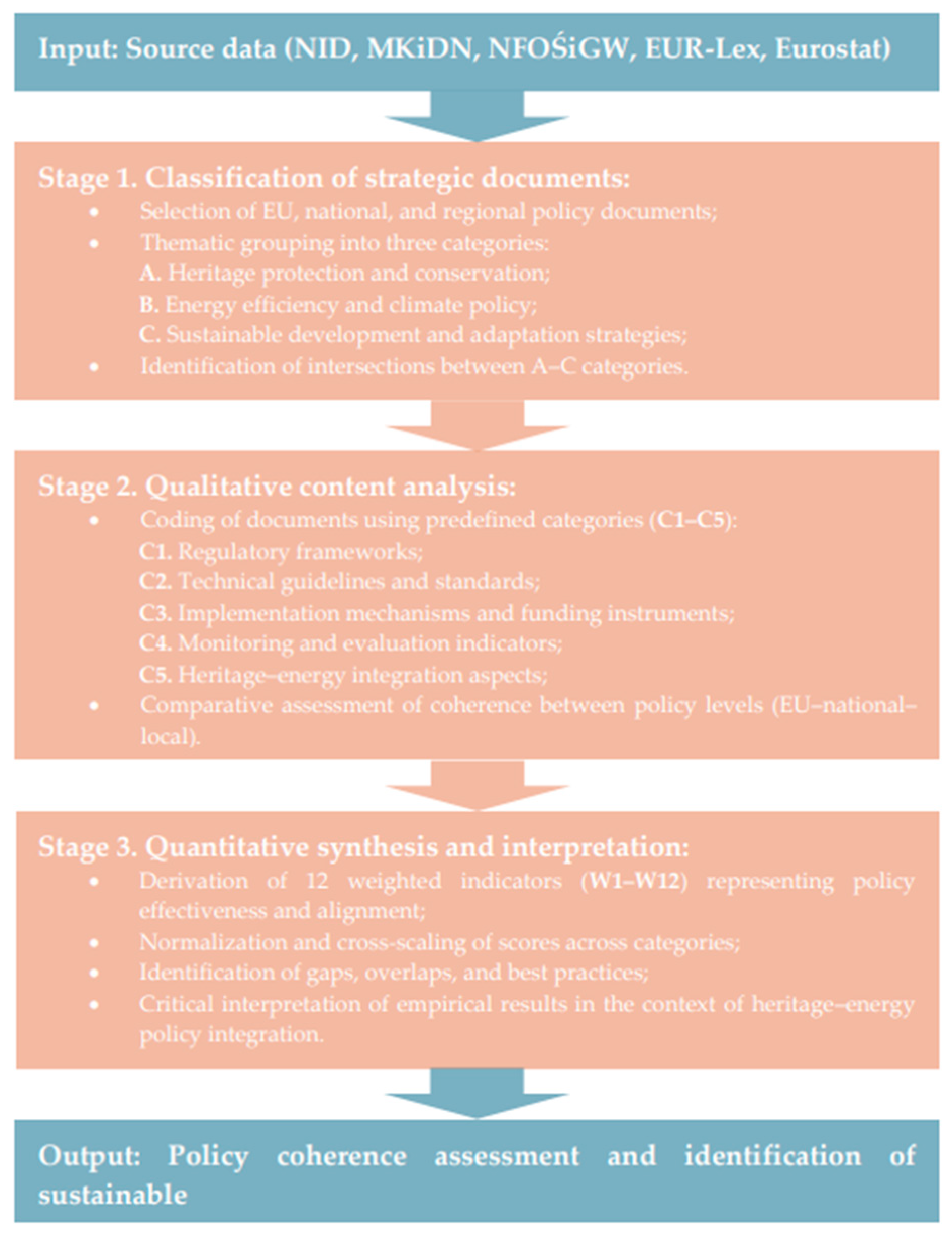

- Stage 1. The classification of strategic documents (EU, national, regional) according to thematic relevance (A. Heritage protection; B. Energy efficiency; C. Sustainable development);

- Stage 2. The qualitative content analysis using predefined categories and coding schemes (C1–C5) reflecting regulatory and implementation dimensions;

- Stage 3. The quantitative synthesis through comparative scoring of indicators (W1–W12), followed by critical interpretation in relation to the identified policy gaps.

3. EU-Funded Research and Demonstration Projects on the Energy Efficiency of Historic Buildings

3.1. Climate for Culture (CfC)

- Key contribution: combination of climate projections with indoor environment and material risk parameters; strong scientific foundation, broad consortium;

- Limitations: emphasis on risk and adaptation (climatic conditions, microclimate management) rather than hard indicators of energy efficiency improvements at the building level;

- Policy relevance: support for EU adaptation policies and heritage resource resilience strategies.

3.2. EFFESUS—Energy Efficiency for EU Historic Districts’ Sustainability

- Advantage: transfer of assessment from individual buildings to urban complexes, integration of technical, energy and conservation criteria;

- Limitations: DSS requires local calibration (data on resources, climate, management practices), and the comparability of results between cities is sometimes limited by contextual differences;

- Policy relevance: direct support for the Renovation Wave and EPBD (planning the sequence of interventions in the historic fabric).

3.3. RIBuild—Robust Internal Thermal Insulation of Historic Buildings

- Advantage: strong operationalisation of condensation and degradation risks for internal insulation solutions, which translates into practical design decisions;

- Limitations: recommendations require accurate material data and in situ verification; transfer to buildings with unusual structures may be limited;

- Policy relevance: substantive support for the implementation of the EPBD and national standards for protected buildings.

3.4. Protection of Cultural Heritage Objects with Multifunctional Advanced Materials (Nano-Heritage HEROMAT)

- Advantage: material progress (functional surfaces with protective properties) that can indirectly support the durability of building envelope elements in energy modernisation projects;

- Limitations: emphasis on material protection rather than energy balance; need for long-term in situ ageing assessment;

- Policy relevance: synergy with EU policy on safe and sustainable building materials (SSbD) and energy-efficient conservation.

3.5. Climate2Preserv

- Advantage: pragmatic, process-oriented nature (how to make decisions within real constraints);

- Limitations: stronger roots in the museum/institutional sector than in historic residential buildings;

- Policy relevance: support for the implementation of energy saving and adaptation plans in the cultural sector, consistent with the Green Deal and efficiency targets.

3.6. A Critical Synthesis of Projects

- The assessment of risk and resilience (Climate for Culture)– adaptation tools and risk mapping for heritage;

- Integrated Intervention Planning (EFFESUS)—multi-criteria DSS for historic districts, combining energy efficiency with conservation values;

- The technical validation of critical solutions (RIBuild, HEROMAT materials)—procedures for assessing internal insulation and material durability, minimising the risk of damage.

3.7. Current Global Validation of the HAM Models (Heat, Air and Humidity)

- Dang, Janssen and Roels provide a comprehensive benchmark dataset for validating HAM models of building components (data and verification protocols) [48];

- Dang et al. conducted a multi-centre, empirical round-robin validation of HAM models. The objective of this study was to assess the robustness and reliability of these models in predicting 1D hygrothermal response [49].

4. Results

4.1. European Union Strategic Documents on Improving the Energy Performance of Buildings (Since 2005)

4.2. Polish Strategic Documents on Improving the Energy Performance of Buildings (Since 2005)

- EU legislation mandating the development of long-term renovation plans;

- Growing public debate on air pollution and the energy performance of older, often historic buildings;

- The Ministry of Culture’s recognition of the need to establish guidelines reconciling conservation requirements with climate goals.

4.3. Polish Strategic Documents (Post-2005) on Building Energy Efficiency and Heritage Protection

4.4. Summary of Results

4.4.1. Implementing Bodies

4.4.2. Linkages

4.4.3. Impact

4.5. Comparative Analysis of EU and Polish Policies

4.5.1. Scope and Approach

4.5.2. Hierarchical Linkages

4.5.3. Differences in Priorities

4.5.4. Implementation Instruments

4.5.5. Impact on Practice and Critical Observations

- Insufficient dissemination of knowledge—many owners are unaware of new opportunities or fear bureaucracy;

- Economic barriers—even with grants, heritage modernisation is costlier, and not all owners qualify;

- Regulatory gaps—GKZ guidelines lack the status of a regulation, and the Heritage Protection Act still does not reference climate protection or energy efficiency. Researchers also underline the need for monitoring and evaluation of outcomes (whether heritage values have been preserved and energy savings achieved).

4.6. Empirical Research on the Energy Modernisation of Heritage Buildings in Poland (2015–2025)

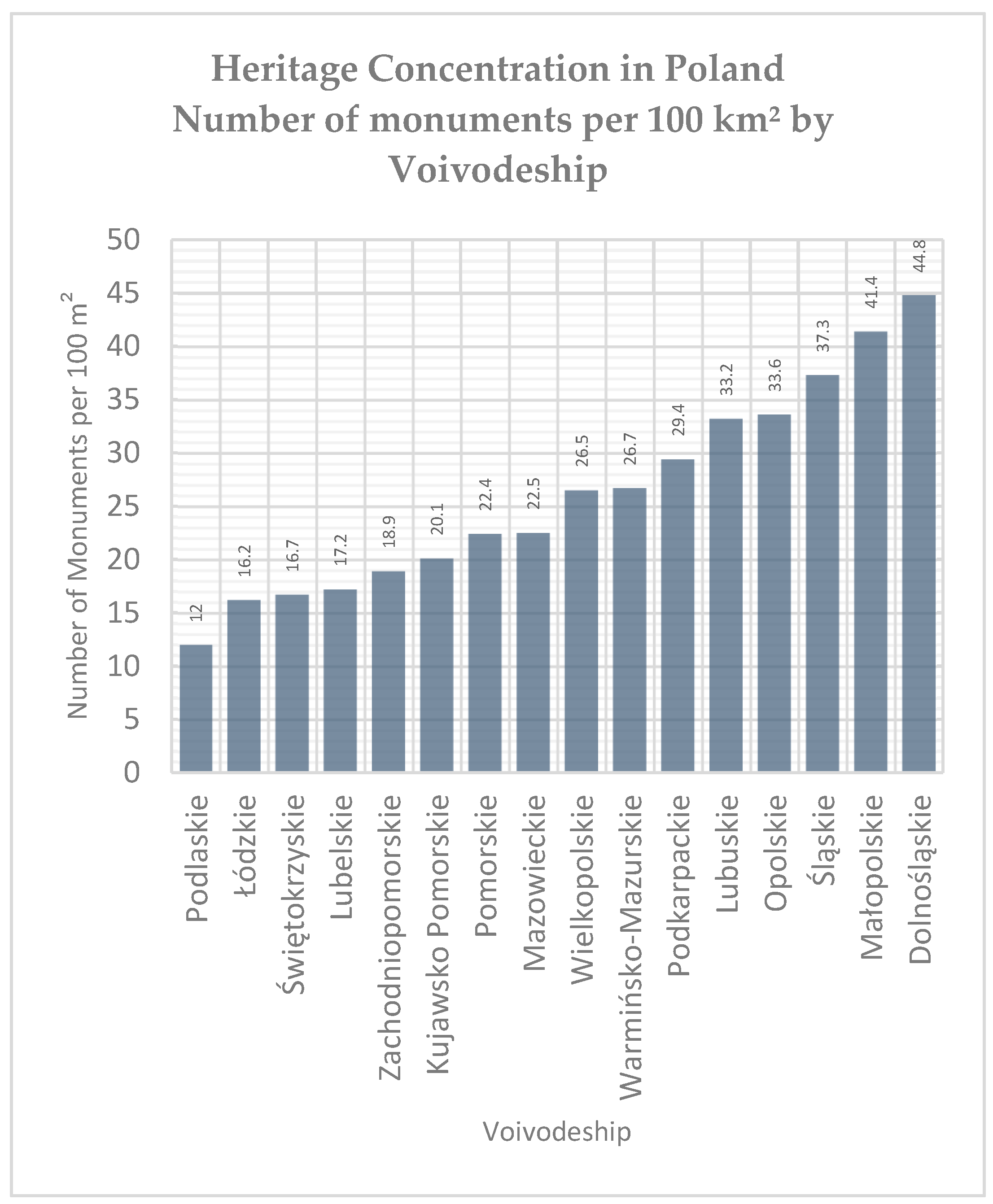

- The number of heritage assets by administrative division (voivodeships and counties;

- Typology (sacral, residential, public utility, post-industrial, defensive, etc.);

- Spatial distribution of buildings nationwide (geographical coordinates).

- Delineating a map of heritage concentration—by calculating the number of assets per unit area (e.g., per 100 km2) in each voivodeship;

- A spatial comparison with data on modernisation projects is enabled, thereby allowing for the juxtaposition of the number of monuments with the number of energy retrofit investments (e.g., Clean Air, ROP, or MKiDN programmes);

- Identifying potential conservation–energy conflict areas—by analysing the overlap of high heritage concentration with regions of intense modernisation activity.

- Heritage density index—number of monuments per 100 km2 (Figure 2);

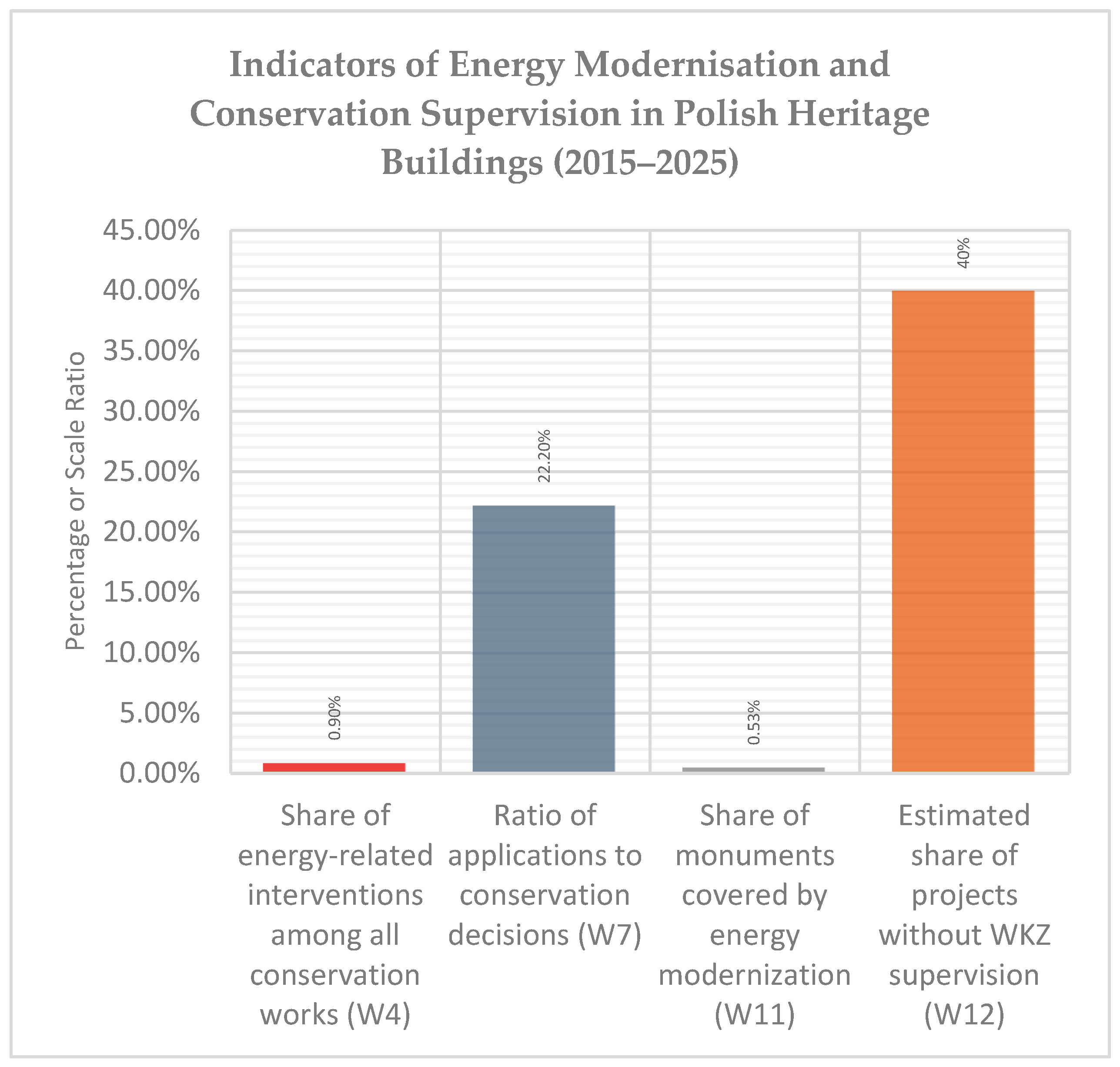

- Modernisation-to-heritage ratio—number of modernisation projects per 100 monuments (Figure 3);

- Conservation risk coefficient—the relationship between the intensity of modernisation and the formal supervision of the Regional Heritage Conservator (WKZ) (Figure 3).

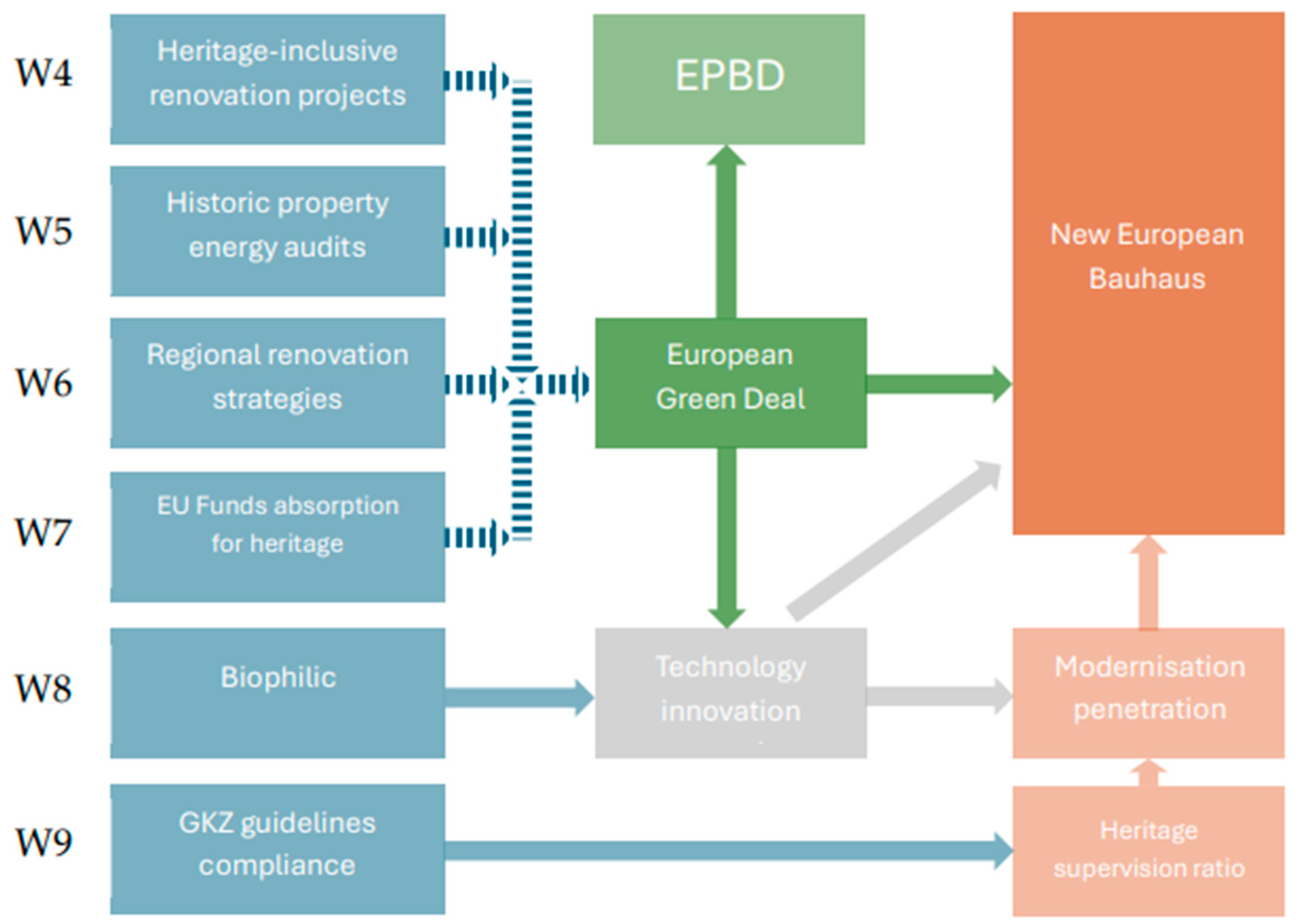

- Modernisation measures must respect the character, materiality, and authenticity of heritage buildings;

- National and regional renovation plans are required to include historic buildings within long-term strategies, in line with EPBD Recitals 12 and 13;

- EU funding instruments (e.g., FEnIKS, LIFE, Horizon Europe) should prioritise projects that combine energy efficiency with heritage conservation, supporting design approaches that are sustainable, reversible, and culturally sensitive.

5. Discussion

5.1. Definitional and Practical Collisions

5.2. The Regulatory Gap and Divergent National Approaches

5.3. Innovative Solutions in the Energy Modernisation of Historic Buildings

- Internal insulation systems using capillary-active, vapour-permeable materials (e.g., calcium silicate, aerogel plasters), which regulate moisture while improving thermal comfort;

- Thin-layer reflective coatings and transparent thermal insulations, applied to preserve historic façades without visual impact;

- Energy-efficient window retrofits, such as replacing glazing with vacuum or low-emissivity panes while retaining original wooden frames;

- Adaptive HVAC systems and heat recovery ventilation integrated discreetly into existing structures, ensuring both comfort and material preservation;

- Renewable energy integration through reversible solutions, such as ground-source heat pumps or low-visibility photovoltaic systems (BIPV), designed to respect heritage silhouettes.

- Villetta Serra is a historic 19th-century villa located in the centre of Genoa. The building is currently under the supervision of the Archaeology, Art and Landscape Superintendency, as it has been recognised as an architectural monument (registered entry). The owner, in collaboration with the Polytechnic University of Genoa, initiated an innovative project in 2016–2023 to modernise the villa, aiming to harmonise conservation measures with the achievement of a nearly zero-energy building (nZEB) standard. After consultation with the conservator, it was decided that the insulation of the external walls on the façade side must not interfere with the historical appearance of the building. Therefore, the installation of standard thick insulation on the outside (mineral wool, polystyrene) was abandoned. Instead, where technically possible, the internal walls were insulated with materials with high water vapour permeability, which prevents moisture from accumulating in the structure. Additionally, the ceiling above the basement and the flat roof were insulated.The old, leaky window frames (last replaced in 1978) were replaced with contemporary wooden windows that are both aesthetically pleasing and energy efficient, with a very low U-value of ~0.7 W/m2K. This upgrade enhances thermal insulation while maintaining the historic window layout. In terms of the installation systems, a contemporary HVAC system was installed in the villa. The provision of central heating and cooling is facilitated by a ground source heat pump with vertical probes, which are connected to low-temperature underfloor heating. This system has the capacity to function as a surface cooling mechanism during the summer months. Mechanical ventilation with heat recovery was also incorporated into the design, with ventilation devices being discreetly integrated into the existing structure. This was achieved by utilising existing recesses in the walls, created during previous renovations, and the shafts of the newly installed lift, thereby avoiding the need for chiselling new channels in the historic walls. This is complemented by an intelligent building energy management system, which utilises sensors to continuously monitor temperature, humidity, air quality and energy consumption. This optimises the operation of the heat pump and ventilation.It was decided to obtain renewable energy on site—photovoltaic panels with an area of ~20 m2 were installed on the roof (terrace) of the villa, hidden behind the parapet and invisible from the outside. These panels are part of a structure that conceals the existing infrastructure (GSM antennas), so they do not affect the aesthetics of the building.Results: The analyses conducted have demonstrated that the implementation of the aforementioned measures has resulted in a reduction of over 60% in the energy demand of the villa. This represents a substantial accomplishment, particularly in light of the constraints typically associated with historic buildings. The parameters have been brought closer to the nZEB standard applicable to new buildings, as confirmed by insulation calculations: the predicted U-value of the walls is approximately 0.30 W/m2K (previously it exceeded 1.3), the roof has been insulated to U ≈ 0.19 W/m2K, and the new windows have U ~ 0.8 W/m2K. These values meet or exceed the legal requirements for modern buildings in this region. The restoration of the villa was executed in a manner that ensured the preservation of its historic character. The exterior of the building was meticulously maintained, with facades that were meticulously restored in accordance with the original colour scheme. The interior layout was largely preserved, with the majority of new installations discreetly integrated into existing partitions. All additional elements, such as an internal lift or installations, were designed to be reversible and did not compromise the integrity of the original structure. This case exemplifies a harmonious integration of conservation and energy efficiency, underscoring the efficacy of an interdisciplinary approach in achieving substantial energy savings in a historic building while preserving its authenticity and cultural significance [76].

- Another example of good practice is the modernisation of the primary school in Olbersdorf, Saxony. This extensive complex, built in 1927–1928, is listed in the state’s register of historical monuments as an example of Weimar Republic-era school architecture. Before the modernisation, the building struggled with low insulation (walls U ≈ 1.25 W/m2K, roof U ≈ 1.52), significant heat loss, and high gas consumption for heating (~765 MWh per year, equivalent to 174.2 kWh/m2 of primary energy). In summer, classrooms experienced overheating (lack of shade from the east and in the attic) and a lack of daylight (students often had to rely on artificial lighting during the day). The aim of the modernisation was to simultaneously improve learning conditions (thermal comfort in winter and summer, fresh air, better lighting, acoustics) and drastically reduce energy consumption—the aim was to achieve the 3-Litre-Haus standard, i.e., a building consuming the equivalent of 3 L of heating oil per m2 per year (~34 kWh/m2). The design assumptions necessitated the implementation of innovative solutions, given that the conservator permitted only minimal insulation of the façade (maximum thickness of +6 cm). The proposal to install insulation from the interior was dismissed on the grounds of the consequential loss of valuable space and the issue of thermal bridges at the junctures between the walls and ceilings. The decision was taken to utilise a thermal insulation system on the exterior of the façade wall, employing an ultra-thin vacuum panel (VIP) system. The 2 mm-thick VIP panels (λ = 0.008 W/mK) were covered with a 3 mm layer of polyurethane foam (λ = 0.035) for protection and to level the substrate. The entirety of the structure was overlaid with a thin layer of plaster that matched the appearance of the original, historic plaster. Prior to the implementation of this solution, laboratory tests were conducted at the Bauhaus-Universität Weimar, and preliminary trials were undertaken on a section of the building’s wall. However, complications were encountered during the execution of the work. Specifically, the adhesive designed for the purpose of adhering the insulation layers to the foam failed to provide adequate adhesion, resulting in the delamination of the foam from the VIP panels. Consequently, due to technical safety imperatives, a proportion of the installed VIP panels were dismantled and substituted with an alternative material exhibiting a marginally lower lambda value.Notwithstanding the challenges posed by the technology employed, the project’s innovative character was maintained. It was demonstrated that even stringent conservation constraints can be satisfied through the implementation of innovative thermal insulation methods. Another significant element was the enhancement of window frames and ventilation systems. New wooden box windows (in keeping with the original form) were installed with triple thermal insulation glazing and integrated external air vents. The design of the incorporates specific apertures that facilitate the influx of fresh air-Zuluftkastenfenster. The air, initially entering the space between the outer and inner window sashes, is preheated by the incoming airflow. Subsequently, the air passes through the upper apertures in the inner sash frame, thereby entering the interior space. The integration of this solution with mechanical air extraction (exhaust fans in ventilation ducts) and a central heat recovery unit has resulted in the development of a hybrid ventilation system tailored to specific local conditions. Carbon dioxide (CO2) sensors, installed within the building’s control system, are responsible for regulating the intensity of ventilation. In the event of an increase in concentration, the automated system initiates the activation of supplementary exhaust fans. During the summer months, this system is utilised for the purpose of night-time cooling of the building: the windows open automatically within a safe range, and fans are employed to remove heated air with efficiency, thereby enabling the interior temperature to be reduced without the need for air conditioning. Furthermore, in order to mitigate the effects of solar radiation, electrochromic windows have been installed in critical rooms. These windows are capable of darkening on demand (or automatically), thereby limiting the amount of sunlight that enters the building. In addition, slatted blinds have been installed between the window sashes, serving as an additional sun barrier. The interior lighting has been replaced with energy-efficient light-emitting diodes (LEDs) emitting a colour similar to daylight. The heat source was also replaced: the old gas boilers were replaced with a modern condensing boiler with higher efficiency (due to the existing infrastructure, it was decided to stick with gas heating, but its use was significantly reduced thanks to better insulation and heat recovery) (Figure 6).Results: The modernisation of the building has resulted in a multitude of benefits. The anticipated increase in energy efficiency has been demonstrated, with calculations indicating that the heat demand has been reduced to 34 kWh/m2/year (for heating and ventilation), representing an approximate 80% decrease compared to the initial state. The school has been transformed into one of the most energy-efficient historic public buildings in the region. The findings reveal a substantial enhancement in thermal comfort levels. During winter, a consistent temperature is maintained in all classrooms, leading to reduced gas consumption. In summer, the implementation of shading and night-time cooling mechanisms ensures that the classrooms do not overheat. The indoor air quality has also been found to be improved by the hybrid system, which maintains adequate levels of fresh air.

5.3.1. Thin-Layer Thermal Insulation Coatings

5.3.2. Reversible HVAC Systems

5.3.3. Capillary-Active and Microporous Insulations

5.3.4. Microconductive and Bioactive Plasters

5.3.5. Phase Change Materials (PCM) and Intelligent Energy Management

5.3.6. Synthesis

- Preservation of material authenticity;

- Reversibility with minimal intervention;

- Alignment with sustainability principles.

5.4. Integration of Conservation and Sustainable Development

- An example of good practice is the thermal modernisation carried out during the reconstruction of the historic House of the Riflemen’s Brotherhood in Świdwin [83]. This historic building had been stripped of its architectural decoration in previous decades. However, a high stone plinth remained. To preserve this historic element, the decision was made to insulate of the building from the inside (Figure 7).

- The revitalisation of the Kwasowo Palace demonstrates how energy efficiency measures can be successfully integrated into the conservation of historic buildings through participatory governance and EU-funded regional programmes [84,85]. The project illustrates the potential of combining technical renovation with social activation, showing that heritage preservation and climate objectives can be mutually reinforcing when local authorities, residents, and community organisations collaborate within a shared framework of sustainable development (Table 8; Figure 8).

- Another example of good practice is the comprehensive thermal modernisation carried out in a 16th-century palace in Bukowiec [86,87,88]. A pre-investment energy audit revealed an EP (primary energy) index of ~650 kWh/m2 per year. Thanks to the comprehensive thermal modernisation, which included replacing windows and doors, insulating the roof and external walls, and modernising the heating system, the EP index was reduced by nearly 90% to approximately 74.3 kWh/m2 per year. To further improve efficiency, modern, ecological solutions were implemented. The facade of the palace was finished with a 3 cm thick thermally insulating gel plaster. A 26.4 kWp photovoltaic system was installed (panels were placed on the ground and roof of the extension), along with a 13.6 kWh energy storage system and a BMS system for intelligent energy management. A 110 kW ground-source heat pump, working with 16 geothermal probes, was used to heat the building. The renovated Bukowiec Palace has become energy-efficient and environmentally friendly, while retaining its historic character. The investment is a prime example of combining modern technologies (such as heat pumps, photovoltaics, and energy storage) with care for the building’s historic heritage (Table 8; Figure 9).

5.5. Implementation Challenges and the Role of Heritage Authorities

- The absence of a common methodology for assessing the outcomes of heritage modernisations, including a lack of measurable Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) under the EPBD;

- The conflict between authenticity and energy efficiency, which often leads to the rejection of innovative technical solutions;

- Limited access to dedicated funding, as mainstream programmes such as Clean Air do not account for the specific requirements of protected buildings;

- Insufficient collaboration between conservators and energy engineers, which hampers the development of integrated, sustainable design concepts;

- The lack of climate-risk assessment tools for heritage assets, restricting long-term adaptation planning.

- Harmonise definitions and eligibility criteria for heritage assets in modernisation funds;

- Introduce a heritage-energy audit as a standard assessment tool;

- Promote low-invasive technologies, such as thin-layer thermal coatings, reversible HVAC systems, and intelligent microclimate control;

- Incorporate educational and awareness-raising components, in line with the values of the New European Bauhaus.

5.6. Directions for Further Research

- Evaluating the effectiveness of various types of energy interventions in heritage buildings, taking into account their impact on indoor microclimate, material durability, and authenticity;

- Developing energy efficiency indicators integrated with conservation criteria, which could be incorporated into European renovation strategies;

- Expanding empirical databases (e.g., NID, GKZ, NFOŚiGW) to enable statistical analysis of modernisation outcomes at the regional level;

- Modelling cost–benefit scenarios for heritage building modernisation toward 2050, based on data concerning material lifespan, carbon footprint, and operational efficiency;

- Investigating social and perceptual aspects—how modernisation affects local identity, the aesthetic quality of historic spaces, and user well-being.

6. Conclusions

- Evolution of legal and policy frameworks.The shift from exclusionary conservation clauses to integrated objectives of protection and efficiency has led to the emergence of a new heritage management model. Responding to EU policy shifts, Poland has developed strategic documents (PEP2040, DSRB, KPEiK) that for the first time explicitly included historic buildings in national renovation planning;

- Empirical component—the modernisation gap.The analysis of indicators W1–W12 shows that heritage assets constitute only about 0.3–0.5% of all energy efficiency and retrofit projects. Despite the existence of regulatory and financial frameworks, practical implementation remains limited, with a persistent lack of dedicated funding instruments and monitoring systems for the heritage sector;

- Growing importance of conservation guidelines and soft instruments.The Guidelines of the General Conservator of Monuments (2020) and initiatives such as the New European Bauhaus have begun introducing cultural values into energy policy discourse. However, their influence remains constrained due to the absence of legally binding status;

- Need for methodological integration and a conservation–energy audit.The lack of standardised efficiency indicators for heritage buildings hinders data comparability. It is recommended to develop integrated assessment tools combining energy performance metrics with evaluations of authenticity, materiality, and microclimate;

- The concept of “heritage-inclusive renovation strategies.”Implementing sustainable development principles in heritage conservation requires an approach that acknowledges the historical identity, aesthetic, and social dimensions of buildings. Only by integrating heritage assets into long-term renovation strategies—supported by EU funding instruments such as FEnIKS, LIFE, and Horizon Europe—can coherence between cultural and climate goals be achieved.

- Integrate low-impact materials and reversible solutions into Polish technical standards and heritage guidelines.Insights from EU projects such as RIBuild and HEROMAT show that capillary-active, vapour-open, mineral and reversible insulation materials enhance hygrothermal safety while reducing the environmental footprint of retrofits. Their formal inclusion in national standards would facilitate the adoption of solutions consistent with conservation principles and sustainable renovation goals;

- Establish cross-sectoral training programmes for conservators, engineers and policymakers.Effective energy retrofitting of heritage buildings requires close collaboration among building physicists, conservation specialists, architects, and public authorities. Training programmes—modelled on initiatives like Climate2Preserv—should strengthen shared understanding of hygrothermal risks, EU regulatory frameworks, and methods for assessing material durability in historic envelopes;

- Encourage cross-border participation in EU research projects to fill empirical data gaps.Current knowledge gaps—such as limited datasets for hygrothermal modelling, insufficient validation of internal insulation systems under diverse climates, and a lack of long-term monitoring—can be effectively addressed through active involvement of Polish institutions in EU-funded research. Participation in initiatives like empirical HAM round-robin validations would support methodological robustness and improve national retrofit strategies.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BMS | Building Management Systems |

| DSRB 2022 | Long-Term Building Renovation Strategy (Długoterminowa Strategia Renowacji Budynków) |

| EED | Energy Efficiency Directive |

| EPBD | Energy Performance of Buildings Directive |

| FEnIKS 2021–2027 | European Funds for Infrastructure, Climate and Environment 2021–2027 (Fundusze Europejskie na Infrastrukturę, Klimat, Środowisko 2021–2027) |

| GKZ | General Conservator of Monuments (Generalny Konserwator Zabytków) |

| HVAC | Heating, ventilation, and air conditioning system |

| KPDEE 2017 | National Energy Efficiency Action Plan (Krajowy Plan Działań dotyczący efektywności energetycznej) |

| KPEiK 2019 | National Energy and Climate Plan (Krajowy plan na rzecz Energii i Klimatu na lata 2021–2030) |

| KPO | Krajowy Plan Odbudowy i Zwiększania Odporności |

| KPOZ | National Programme for the Protection of Monuments (Krajowy Program Ochrony Zabytków) |

| LIFE | Program Działań na Rzecz Środowiska i Klimat |

| NEB | New European Bauhaus |

| NFOŚiGW | The National Fund for Environmental Protection and Water Management (Narodowy Fundusz Ochrony Środowiska i Gospodarki Wodnej) |

| NID | National Heritage Board of Poland (Narodowy Instytut Dziedzictwa) |

| NIK | Supreme Audit Office (Najwyższa Izba Kontroli) |

| OPI&E | Operational Programme “Infrastructure and Environment 2014–2020 |

| PCM | Phase Change Materials |

| PEP2030 | Energy Policy of Poland until 2030 and 2040 (Polityka Energetyczna Polski do 2030 roku) |

| PEP2040 | Energy Policy of Poland until 2030 and 2040 (Polityka Energetyczna Polski do 2040 roku) |

| RPO | Regionalny Program Operacyjny |

| POIiŚ | Program Operacyjny Infrastruktura i Środowisko |

| WGKZf | Wytyczne Generalnego Konserwatora Zabytków. Instalacje fotowoltaiczne w obiektach zabytkowych |

| WGKZt | Wytyczne Generalnego Konserwatora Zabytków. Termomodernizacja obiektów zabytkowych |

| WKZ | Regional Heritage Conservator (Wojewódzki Urząd Ochrony Zabytków) |

| TEU | Treaty on European Union |

References

- European Union. Treaty on European Union; EU: Lisbon, Portugal, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Council of Europe. European Cultural Convention (ETS No. 018); EU: Paris, France, 1954. [Google Scholar]

- Council of Europe. Framework Convention on the Value of Cultural Heritage for Society (Faro Convention) (CETS No. 199); EU: Faro, Portugal, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. The New EU Strategy on Climate Change Adaptation—Communication COM/2021/82 Final; EU: Brussels, Belgium, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. A Renovation Wave for Europe—Greening Our Buildings, Creating Jobs, Improving Lives COM/2020/662 Final; EU: Brussels, Belgium, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- European Union. Directive 2010/31/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 19 May 2010 on the Energy Performance of Buildings (Recast), OJ L 153, 18.6.2010 (EPBD); EU: Brussels, Belgium, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Sejm Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej. Ustawa z Dnia 23 Lipca 2003 r. o Ochronie Zabytków i Opiece nad Zabytkami (Dz.U. 2022, Poz. 840 z Późn. zm.); Dziennik Ustaw: Warszawa, Poland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. The European Green Deal COM (2019) 640 Final; EU: Brussels, Belgium, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Fit for 55; EU: Brussels, Belgium, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Ministerstwo Aktywów Państwowych. Krajowy Plan na Rzecz Energii i Klimatu na Lata 2021–2030 (KPEiK). Założenia i Cele Oraz Polityki i Działania; MAP: Warszawa, Poland, 2019.

- Ministerstwo Klimatu i Środowiska. Polityka Energetyczna Polski do 2040 r. (PEP2040); MKiŚ: Warszawa, Poland, 2021.

- Climate for Culture. Available online: https://www.climateforculture.eu (accessed on 14 November 2025).

- EFFESUS—Energy Efficiency for EU Historic Districts’ Sustainability. Available online: https://cordis.europa.eu/project/id/314678 (accessed on 14 November 2025).

- RIBuild—Robust Internal Thermal Insulation of Historic Buildings. Available online: https://www.ribuild.eu/home (accessed on 14 November 2025).

- Protection of Cultural Heritage Objects with Multifunctional Advanced Materials (Nano-Heritage, 282992). Available online: https://cordis.europa.eu/project/id/282992 (accessed on 14 November 2025).

- Climate2Preserv. Sustainable Climate Management Strategy to Preserve Federal Collections. Available online: https://www.climate2preserv.be/ (accessed on 14 November 2025).

- European Union. Directive (EU) 2023/1791 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 13 September 2023 on Energy Efficiency and Amending Regulation (EU) 2023/955 (Recast), OJ L 231, 20.9.2023 (EED); EU: Brussels, Belgium, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. New European Bauhaus. Beautiful, Sustainable, Together COM (2021) 573 Final; EU: Brussels, Belgium, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Ministerstwo Gospodarki. Polityka Energetyczna Polski do 2030 Roku (PEP2030); MG: Warszawa, Poland, 2009.

- Ministerstwo Rozwoju i Technologii. Długoterminowa Strategia Renowacji Budynków. Wspieranie Renowacji Krajowego Zasobu Budowlanego (DSRB); MRiT: Warszawa, Poland, 2022.

- Ministerstwo Energii. Krajowy Plan Działań Dotyczący Efektywności Energetycznej (KPDEE); ME: Warszawa, Poland, 2017.

- Ministerstwo Kultury i Dziedzictwa Narodowego (MKiDN). Krajowy Program Ochrony Zabytków i Opieki nad Zabytkami 2019-2022 (KPOZ); MKiDN: Warszawa, Poland, 2018.

- Ministerstwo Kultury i Dziedzictwa Narodowego (MKiDN). Wytyczne Generalnego Konserwatora Zabytków. Termomodernizacja Obiektów Zabytkowych (DOZ.070.2.2020) (WGKZt); MKiDN: Warszawa, Poland, 2020.

- Ministerstwo Kultury i Dziedzictwa Narodowego (MKiDN). Wytyczne Generalnego Konserwatora Zabytków. Instalacje Fotowoltaiczne w Obiektach Zabytkowych (DOZKiNK.6521.27.2020) (WGKZf); MKiDN: Warszawa, Poland, 2020.

- Narodowy Fundusz Ochrony Środowiska i Gospodarki Wodnej (NFOŚiGW). Program Priorytetowy Czyste Powietrze; NFOŚiGW: Warszawa, Poland, 2025.

- Otwarte Dane. Rejestr Zabytków Nieruchomych. Available online: https://dane.gov.pl/pl/dataset/1130,rejestr-zabytkow-nieruchomych (accessed on 18 October 2025).

- BIP Wielkopolski Wojewódzki Konserwator Zabytków—Wojewódzki Urząd Ochrony Zabytków w Poznaniu. Available online: https://www.poznan.wuoz.gov.pl/ (accessed on 18 October 2025).

- BIP Mazowiecki Wojewódzki Konserwator Zabytków—Wojewódzki Urząd Ochrony Zabytków w Warszawie. Available online: https://bip.mwkz.pl/ (accessed on 18 October 2025).

- BIP Małopolski Wojewódzki Konserwator Zabytków—Wojewódzki Urząd Ochrony Zabytków w Krakowie. Available online: https://www.wuoz.malopolska.pl/ (accessed on 18 October 2025).

- BIP Warmińsko—Mazurski Wojewódzki Konserwator Zabytków—Wojewódzki Urząd Ochrony Zabytków w Olsztynie. Available online: https://www.wuoz.olsztyn.pl/ (accessed on 18 October 2025).

- BIP Lubelski Wojewódzki Konserwator Zabytków—Wojewódzki Urząd Ochrony Zabytków w Lublinie. Available online: http://www.wkz.lublin.pl/ (accessed on 18 October 2025).

- BIP Dolnośląski Wojewódzki Konserwator Zabytków—Wojewódzki Urząd Ochrony Zabytków we Wrocławiu. Available online: https://wosoz.ibip.wroc.pl/public/ (accessed on 18 October 2025).

- BIP Śląski Wojewódzki Konserwator Zabytków—Wojewódzki Urząd Ochrony Zabytków w Katowicach. Available online: http://bip.wkz.katowice.pl/ (accessed on 18 October 2025).

- BIP Łódzki Wojewódzki Konserwator Zabytków—Wojewódzki Urząd Ochrony Zabytków w Łodzi. Available online: https://www.wuoz-lodz.pl/ (accessed on 18 October 2025).

- BIP Podlaski Wojewódzki Konserwator Zabytków—Wojewódzki Urząd Ochrony Zabytków w Białymstoku. Available online: https://www.gov.pl/web/wuoz-bialystok (accessed on 18 October 2025).

- BIP Podkarpacki Wojewódzki Konserwator Zabytków—Wojewódzki Urząd Ochrony Zabytków w Przemyślu. Available online: https://wuozprzemysl.pl/ (accessed on 18 October 2025).

- BIP Lubuski Wojewódzki Konserwator Zabytków—Wojewódzki Urząd Ochrony Zabytków w Zielonej Górze. Available online: https://lwkz.pl/ (accessed on 18 October 2025).

- BIP Pomorski Wojewódzki Konserwator Zabytków—Wojewódzki Urząd Ochrony Zabytków w Gdańsku. Available online: https://ochronazabytkow.gda.pl/ (accessed on 18 October 2025).

- BIP Opolski Wojewódzki Konserwator Zabytków—Wojewódzki Urząd Ochrony Zabytków w Opolu. Available online: https://wuozopole.pl/ (accessed on 18 October 2025).

- BIP Kujawsko—Pomorski Wojewódzki Konserwator Zabytków—Wojewódzki Urząd Ochrony Zabytków w Toruniu. Available online: https://www.torun.wkz.gov.pl/ (accessed on 18 October 2025).

- BIP Świętokrzyski Wojewódzki Konserwator Zabytków—Wojewódzki Urząd Ochrony Zabytków w Kielcach. Available online: https://www.gov.pl/web/wuoz-w-kielcach/ (accessed on 18 October 2025).

- BIP Zachodniopomorski Wojewódzki Konserwator Zabytków—Wojewódzki Urząd Ochrony Zabytków w Szczecinie. Available online: https://wkz.szczecin.pl/ (accessed on 18 October 2025).

- Mapa Dotacji UE. Available online: https://mapadotacji.gov.pl/ (accessed on 18 October 2025).

- Ministerstwo Kultury i Dziedzictwa Narodowego. Available online: https://www.gov.pl/web/kultura (accessed on 18 October 2025).

- Narodowy Fundusz Ochrony Środowiska i Gospodarki Wodnej (NFOŚiGW). Available online: https://www.gov.pl/web/nfosigw/podstawowe-informacje (accessed on 18 October 2025).

- BIP Główny Urząd Nadzoru Budowlanego. Available online: https://www.gov.pl/web/gunb (accessed on 18 October 2025).

- Kultura i Dziedzictwo Narodowe w 2021 r. Culture and National Heritage in 2021. Główny Urząd Statystyczny. Analizy Statystyczne Statistical Analyses; GUS: Warszawa, Poland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Dang, X.; Janssen, H.; Roels, S. A comprehensive benchmark dataset for the validation of building component heat, air, and moisture (HAM) models. Build. Simul. 2024, 17, 1893–1907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, X.; Guimarães, A.S.; Sarkany, A.; Laukkarinen, A.; Xu, B.; Vanderschelden, B.; Roels, S. A state-of-the-art empirical round robin validation of heat, air and moisture (HAM) models. Build. Environ. 2025, 276, 112867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Union. Directive 2012/27/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 25 October 2012 on Energy Efficiency, Amending Directives 2009/125/EC and 2010/30/EU and Repealing Directives 2004/8/EC and 2006/32/EC; EU: Brussels, Belgium, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- European Union. Directive (EU) 2018/844 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 30 May 2018 Amending Directive 2010/31/EU on the Energy Performance of Buildings and Directive 2012/27/EU on Energy Efficiency; EU: Brussels, Belgium, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- European Union. Directive 2002/91/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 16 December 2002 on the Energy Performance of Buildings, OJ L 1, 4.1.2003; EU: Brussels, Belgium, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Lidelöw, S.; Örn, T.; Luciani, A.; Rizzo, A. Energy-efficiency measures for heritage buildings: A literature review. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2019, 45, 231–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leijonhufvud, G.; Eriksson, P.; Broström, T. Energy efficiency in historic buildings. In Energy Efficiency in Historic Buildings Routledge, 1st ed.; Fouseki, K., Cassar, M., Dreyfuss, G., Ang Kah Eng, K., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2022; pp. 290–304. [Google Scholar]

- Webb, A.L. Energy retrofits in historic and traditional buildings: A review of problems and methods. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 77, 748–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pałubska, K.; Zalasińska, K. Najnowsze dokumenty strategiczne określające zmiany w podejściu do modernizacji zabytków w Polsce. Ochr. Dziedzictwa Kult. 2021, 11, 127–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schatt-Babińska, K. Zabytek przyjazny środowisku—możliwości stosowania proekologicznych rozwiązań w teorii i praktyce. TECHNE Ser. Nowa 2022, 14, 161–180. [Google Scholar]

- Lucchi, E. Energy Efficiency of Historic Buildings. Buildings 2022, 12, 200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schatt-Babińska, K. Zabytek przyjaznego środowiska–możliwości stosowania proekologicznych w teorii i praktyce. Zarys problemu. TECHNA Ser. Nowa 2022, 10, 61–180. [Google Scholar]

- Włodarczyk, M.; Włodarczyk, M. Doktryny konserwatorskie a paneuropejska idea Nowego Europejskiego Bauhausu i Europejskiego Zielonego Ładu. Ochr. Dziedzictwa Kult. 2021, 12, 35–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buda, A.; de Place Hansen, E.J.; Rieser, A.; Giancola, E.; Pracchi, V.N.; Mauri, S.; Herrera-Avellanosa, D. Conservation-Compatible Retrofit Solutions in Historic Buildings: An Integrated Approach. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potts, A. European Cultural Heritage Green Paper; Europa Nostra: Hague, The Netherlands; Brussels, Belgium, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- European Committee for Standardization. The European standard EN 16883:2017 Conservation of cultural heritage. Guidelines for improving the energy performance of historic buildings; European Committee for Standardization: Brussels, Belgium, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Leissner, J.; Grady, A.; Maraña, M.; Baeke, F.; van Cutsem, A. Strengthening Cultural Heritage Resilience for Climate Change. Where the European Green Deal meets Cultural Heritage-Report; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Sejm Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej. Ustawa z Dnia 9 Października 2015 r. o Rewitalizacji (Dz.U. 2015 poz. 1777); Dziennik Ustaw: Warszawa, Poland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, H.; Tan, H.; Tzempelikos, A. The effect of reflective coatings on building surface temperatures, indoor environment and energy consumption—An experimental study. Energy Build. 2011, 43, 573–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tariq, L.R.; Jafaar, A.M. A Review of Nanotechnology in Self-Healing of Ancient and Heritage Buildings: Heritage Buildings, Nanomaterial, Nano Architecture, Nanotechnology in Construction. Int. J. Nanoelectron. Mater. (IJNeaM) 2024, 17, 153–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacheco-Torgal, F.; Cabeza, L.F.; Labrincha, J.; Giuntini de Magalhaes, A. Eco-Efficient Construction and Building Materials Life Cycle Assessment (LCA), Eco-Labelling and Case Studies, 1st ed.; Woodhead Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- De Vita, M.; Duronio, F.; De Vita, A.; De Berardinis, P. Adaptive Retrofit for Adaptive Reuse: Converting an Industrial Chimney into a Ventilation Duct to Improve Internal Comfort in a Historic Environment. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastian, Z.; Spiekman, M.; Troi, A. Energy retrofit of historic buildings: The 3ENCULT Project. REHVA J. 2014, 3, 24–27. [Google Scholar]

- Kozłowska, I. Historical earth architecture in terms of climate change in the temperature climate area (Central Europe). IOP IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2018, 471, 102030. [Google Scholar]

- Council of Europe. Convention for the Protection of the Architectural Heritage of Europe (Granada Convention); EU: Strasbourg, France, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Cultural Heritage and Activities and Tourism (Italy). The Operational Guidelines for Energy Efficiency Improvement of the Cultural Heritage; Ministry of Cultural Heritage and Activities and Tourism (Italy): Rome, Italy, 2015.

- DuMo: A Calculation Model to Map Sustainability in Combination with the Building Historic Value. Available online: https://www.interregeurope.eu/good-practices/dumo-a-calculation-model-to-map-sustainability-in-combination-with-the-building-historic-value (accessed on 18 October 2025).

- Kulturarvsstyrelsen (2011) SAVE—Kortlægning og Registrering af Bymiljøers og Bygningers Bevaringsværdi. Kulturministeriet. Available online: https://slks.dk/fileadmin/user_upload/kulturarv/fysisk_planlaegning/dokumenter/SAVE_vejledning.pdf (accessed on 18 October 2025).

- Franco, G.; Mauri, S. Reconciling Heritage Buildings’ Preservation with Energy Transition Goals: Insights from an Italian Case Study. Sustainability 2024, 16, 712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BMWi-Begleitforschung Energieeffiziente Schulen (EnEff:Schule). Demonstrationsobjekte. 3-Liter-Haus-Schulen in Olbersdorf. Available online: https://www.eneff-schule.de/index.php/demonstrationsobjekte/3-liter-haus-schulen/olbersdorf.html (accessed on 14 November 2025).

- Friedrich-Fröbel-Schule Olbersdorf. Available online: https://amper.ped.muni.cz/pasiv/regenerace/pamatkove_vakuove/Endbericht_Olbersdorf.pdf (accessed on 14 November 2025).

- Vereecken, E.; Roels, S. Capillary Active Interior Insulation: A Discussion. Energy Effic. Comf. Hist. Build. 2016, 191–197. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, J.; Grunewald, J.; Ruisinger, U.; Feng, S. Evaluation of capillary-active mineral insulation systems for interior retrofit solution. Build. Environ. 2017, 115, 215–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroderus, S.; Kuurola, P.; Kempe, M.; Fedorik, F.; Leivo, V.; Haverinen-Shaughnessy, U. Impacts of building energy retrofits on energy consumption, indoor environment, and hygrothermal performance in future climate scenarios. Energy Build. 2025, 347, 116413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, R.; Shan, L.; Wu, Y.; Cai, Y.; Huang, R.; Ma, H.; Tang, K.; Liu, K. Phase-change materials for intelligent temperature regulation. Mater. Today Energy 2022, 23, 100888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Świdwin (woj. Zachodniopomorskie)—Budynkowi Dawnego Domu Strzeleckiego Przywrócono Wygląd Zbliżony do Historycznego. Available online: https://rekonstrukcjeiodbudowy.pl/swidwin-woj-zachodniopomorskie-budynkowi-dawnego-domu-strzeleckiego-przywrocono-wyglad-zblizony-do-historycznego/ (accessed on 14 November 2025).

- Katalog Polskich Zamków, Pałaców i Dworów. Kwasowo. Available online: https://www.polskiezabytki.pl/m/obiekt/7364/Kwasowo/ (accessed on 14 November 2025).

- 2020 —Zrewitalizowano Pałac w Kwasowie. Available online: https://gminaslawno.pl/cms/8922/2020__zrewitalizowano_palac_w_kwasowie (accessed on 14 November 2025).

- Katalog Polskich Zamków, Pałaców i Dworów. Bukowiec. Available online: https://www.polskiezabytki.pl/m/obiekt/36/Bukowiec/ (accessed on 14 November 2025).

- Niezwykła Rewitalizacja Dolnośląskiego Pałacu. Available online: https://www.propertydesign.pl/architektura/104/niezwykla_rewitalizacja_dolnoslaskiego_palacu_tak_teraz_wyglada_zdjecia,50686.html (accessed on 14 November 2025).

- Bryła. Termomodernizacja z Historią w tle. Rewitalizacja Pałacu w Bukowcu na Dolnym Śląsku. Available online: https://www.bryla.pl/rewitalizacja-palacu-w-bukowcu-na-dolnym-slasku-odzyskal-dawny-blask (accessed on 14 November 2025).

| Indicator Code | Indicator Name | Description and Calculation Method | Data Source (Public) | Type of Analysis |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| W1 | Number of immovable monuments | Total number of properties listed in the Register of Immovable Monuments in a given year (or as of the end of the 2015–2025 period). | National Heritage Board of Poland (NID)—Open Data (otwartedane.nid.pl) [26] | Reference stock analysis |

| W2 | Number of conservation interventions | Number of decisions issued by Regional Monument Conservators regarding works on monuments (repairs, conservation, modernisation). | Public Information Bulletins (BIP) of Regional Monument Conservators [27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42] | Analysis of conservation activity |

| W3 | Number of projects financed with public funds | Number of modernisation or renovation projects concerning heritage buildings co-financed by EU funds, NFOŚiGW, or the Ministry of Culture and National Heritage (MKiDN). | mapadotacji.gov.pl [43]; MKiDN [44]; NFOŚiGW [45] | Financial analysis |

| W4 | Share of energy-related projects in total conservation interventions | (Number of projects with an energy-efficiency component/total number of conservation projects) × 100% | MKiDN [44]; NFOŚiGW [45]; BIP WKZ [27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42] | Structural analysis |

| W5 | Average value of financial support for energy projects | Average amount of funding for projects including energy-efficiency improvements in heritage buildings. | NFOŚiGW [45]; mapadotacji.gov.pl [43] | Economic analysis |

| W6 | Share of voivodeships with high thermomodernisation intensity | (Number of Clean Air programme applications/number of monuments in the voivodeship) × 1000 | NFOŚiGW [45]; NID [26] | Spatial density analysis (heat map) |

| W7 | Ratio of programme applications to conservation decisions | (Number of Clean Air programme applications/number of WKZ decisions)—an indicator of potential interventions conducted without conservation supervision. | NFOŚiGW [45]; BIP WKZ [27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42] | Conservation risk analysis |

| W8 | Dynamics of MKiDN funding for heritage protection | Year-to-year change in the total amount of conservation grants during the 2015–2025 period. | MKiDN (otwartedane.gov.pl) [44] | Trend analysis |

| W9 | Number of energy performance certificates for pre-1945 buildings | Number of historic buildings registered in the CHEB database (GUNB), disaggregated by voivodeship. | GUNB—CHEB Register [46] | Comparative analysis of energy performance |

| W10 | Share of renovation projects using modern low-impact technologies (e.g., thin-film coatings) | Number of projects employing minimally invasive technologies to improve energy efficiency (based on project descriptions in the funding database). | mapadotacji.gov.pl [43]; technical reports—MKiDN | Qualitative innovation analysis |

| W11 | Ratio of monuments to energy retrofit projects (modernisation penetration index) | (Number of monuments subjected to energy modernisation/total number of monuments) × 100% | NFOŚiGW [45]; NID [26]; MKiDN [44] | Estimation based on public databases (mapadotacji.gov.pl, MKiDN, NFOŚiGW); requires further verification of projects’ “energy component.” |

| W12 | Regional conservation–energy conflict coefficient | (Number of energy projects implemented without WKZ approval/total number of energy projects) × 100% | NFOŚiGW [45]; BIP WKZ [27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42] | Conflict and compliance analysis |

| Document (Year) | Issuing Body | Main Assumptions Regarding Cultural Heritage and/or Energy Efficiency |

|---|---|---|

| Directive 2010/31/EU on the Energy Performance of Buildings (EPBD Recast, 2010) [6] | European Parliament and Council of the EU | Established minimum energy efficiency requirements for buildings. Allowed Member States to exempt heritage buildings from these obligations (Art. 4(2a)) to preserve their architectural and historical value. Introduced energy performance certificates, excluding protected monuments. |

| Directive 2012/27/EU on Energy Efficiency (EED, 2012) [50] | European Parliament and Council of the EU | Set binding energy-saving targets, including the obligation to renovate 3% of central government buildings annually. Allowed exemptions for historically valuable buildings (Art. 5(2)), recognising the need to respect their specific character. |

| Directive (EU) 2018/844 amending EPBD and EED (2018) [51] | European Parliament and Council of the EU | Introduced long-term renovation strategies (up to 2050) covering the entire building stock, including heritage buildings. Emphasised “deep renovation” towards nearly zero-energy buildings (nZEB) while preserving historic value and authenticity. |

| European Green Deal (2019) [8] | European Commission | Comprehensive EU strategy for achieving climate neutrality by 2050. Envisioned a large-scale building renovation initiative (Renovation Wave). Initially focused on energy transition and job creation, with cultural heritage integrated later through initiatives such as the New European Bauhaus. |

| Renovation Wave—Communication COM (2020) 662 (2020) [5] | European Commission | Aimed to double the renovation rate across the EU and remove investment barriers (~35 million renovations by 2030). Recognised the need for specific approaches to historic buildings and encouraged the exchange of best practices and the use of traditional, sustainable materials. |

| New EU Strategy on Adaptation to Climate Change (2021) [4] | European Commission | Focused on enhancing climate resilience of infrastructure and communities. Cultural heritage was mentioned only marginally, with general references to the need to protect valuable assets from climate impacts. No specific instruments were introduced. |

| New European Bauhaus Initiative (2020–2021) [18] | European Commission | A cultural and design initiative complementing the Green Deal, promoting the fusion of aesthetics, sustainability, and inclusiveness in the built environment. Encouraged innovative renovation of heritage buildings by combining energy efficiency with preservation of historic character (e.g., adaptive reuse with ecological materials). |

| Document (Year) | Issuing Body | Main Provisions Regarding Cultural Heritage and/or Energy Efficiency | Links to Other Documents and Implementation Programmes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Polish Energy Policy to 2030 (2009) [19] | Ministry of Economy (Council of Ministers Resolution) | Comprehensive national energy strategy to 2030—no direct reference to heritage. Focused on energy security, development of renewables, and general energy efficiency improvements. Issues related to historic buildings were not addressed. | Linked to the EU “3 × 20” targets for 2020; served as the basis for the National Energy Efficiency Action Plans (2011, 2014). Implemented through programmes such as Thermomodernisation Fund (BGK) for residential buildings—without specific provisions for heritage assets. Renovation of monuments was financed separately (via MKiDN and EU 2007–2013 funds) without integrating energy goals. |

| National Energy Efficiency Action Plan (e.g., 2014, 2017) [21] | Ministry of Economy/Energy | Detailed implementation plans for achieving national energy-saving targets. Recognised the specificity of heritage buildings, noting that technical and cultural constraints may prevent the application of standard retrofitting measures. The 2014 Plan states: Heritage-listed buildings form a separate group… not all interventions or technical solutions can be applied. Required by the EED Directive; consistent with the national energy policy. Later versions introduced references to heritage renovation (mainly diagnostic). | Implemented through NFOŚiGW programmes for the public sector (e.g., subsidies for energy audits). Some municipalities established special revitalisation zones combining heritage renovation with energy upgrades (funded via Regional Operational Programmes). |

| Polish Energy Policy to 2040 (PEP2040, 2021) [11] | Ministry of Climate and Environment (Council of Ministers Resolution) | Long-term strategy to 2040 aligned with EU climate goals (CO2 reduction, RES development). Mentions the need for energy retrofits of buildings with respect for heritage values, though vaguely. Focuses on replacing coal boilers and thermomodernising residential stock, without a dedicated heritage section. | Connected to the European Green Deal and National Energy and Climate Plan (KPEiK). Channelled national and EU funds (Cohesion Policy 2021–2027) to programmes such as Clean Air, Stop Smog, and Thermomodernisation Bonus. No separate heritage programme, though PEP2040 informed Poland’s Recovery Plan, including renovation of historic public buildings. |

| National Energy and Climate Plan 2021–2030 (KPEiK, 2019) [10] | Ministry of Energy/Committee for European Affairs | Implemented EU 2030 goals (emissions, RES, efficiency). Addressed heritage mainly through the lens of post-industrial transformation, calling for protection and adaptive reuse of mining heritage. Recognised legal and technical barriers in heritage energy retrofits. | Required under EU Regulation 2018/1999 (Energy Union Governance). Complementary to PEP2040. Implemented through sectoral policies (construction and climate). Synergistic with the National Urban Policy and revitalisation programmes, referencing air-quality improvement in historic city centres. |

| Long-Term Building Renovation Strategy (DSRB, draft 2020; final 2022) [20] | Ministry of Development and Technology | Developed under EPBD/EED requirements; outlines deep renovation of the national building stock to 2050. The 2020 draft proposed deep retrofits even for heritage buildings, criticised for excluding conservators. The final 2022 version, after consultation, added annexes on historic building renovation aligned with conservation guidelines. Promotes energy upgrades that respect authenticity (e.g., window sealing, HVAC modernisation). | Required by EPBD/EED, linked to PEP2040 and KPEiK. Consulted with MKiDN, incorporating the General Heritage Conservator’s Guidelines as an annex—an example of cross-ministerial cooperation. Implemented through an Action Plan to 2030 (EU and national funds, including NFOŚiGW programmes and tax incentives). |

| National Programme for the Protection of Monuments and the Care of Monuments 2019–2022 (adopted 2018) [22] | Ministry of Culture and National Heritage (MKiDN) | National conservation programme defining state priorities. For the first time, addressed energy and climate issues—including guidelines for installing PV systems and thermally upgrading historic buildings. Emphasised balancing heritage protection with user comfort and sustainability. | Based on Art. 87 of the Heritage Protection Act (updated every 4 years). Linked to the European Year of Cultural Heritage 2018. Implemented via National Heritage Board (NID) projects (e.g., development of technical standards for PV and thermal retrofits, training for conservators). Partly funded by EU Cultural and Infrastructure & Environment Programmes. |

| Guidelines of the General Heritage Conservator: Thermomodernisation of Historic Buildings (2020) [23] | General Heritage Conservator/MKiDN | Technical guidelines defining permissible methods of improving energy performance in heritage buildings. Recommend interior insulation (if exterior not possible), use of traditional/reversible materials, window restoration, and improved ventilation. Require energy audits approved by conservators to demonstrate achievable savings without damage. | Linked to the National Heritage Programme 2019–2022 (fulfilling one of its goals). Complementary to GKZ guidelines on moisture and ventilation. Circulated to regional conservators and applied in project evaluations and permit procedures. |

| Guidelines of the General Heritage Conservator: Photovoltaic Installations in Historic Buildings (2020) [24] | General Heritage Conservator/MKiDN | Detailed rules for PV installation on or near heritage buildings. Prioritise preserving visual integrity—recommend locating panels on less visible roof slopes or on the ground, prohibiting installation on valuable historic coverings (e.g., shingles, ceramic tiles). Require a visual impact assessment before approval. | Issued alongside the 2020 Thermomodernisation Guidelines as part of the GKZ climate-heritage adaptation package. Distributed to conservators with evaluation templates. Aligned with NFOŚiGW funding schemes, which require heritage-compliant opinions for PV projects. |

| Document (Year) | Impact on Heritage Conservation Practice and Evaluation |

|---|---|

| Directive 2010/31/EU on the Energy Performance of Buildings (EPBD, recast 2010) [6] | Initially, the exemption of heritage buildings helped protect their historic fabric from inappropriate retrofitting, but it also slowed efforts to improve their energy performance. Many listed buildings in both the EU and Poland remained outside energy-efficiency standards. Critics argue that excluding this category entirely represented a missed opportunity to reduce energy consumption, calling instead for a more balanced approach rather than blanket exemptions. |

| Directive 2012/27/EU on Energy Efficiency (EED, 2012) [50] | Encouraged Member States to establish support mechanisms for renovation; however, in practice, the renovation of heritage buildings progressed more slowly. Public institutions often relied on exemption clauses, postponing upgrades to historic structures. Scholarly analyses emphasise the need to balance efficiency requirements with the protection of artistic and cultural values, noting the insufficient pace of improvement in the energy performance of historic buildings compared with other sectors. |

| Directive 2018/844/EU amending the EPBD and EED (2018) [51] | Broadened the scope of building modernisation and stimulated discussion on the appropriate ways to renovate heritage properties. In Poland and other Member States, this prompted heritage authorities to participate in drafting long-term renovation strategies. However, experts noted that Poland’s initial draft of the strategy ignored conservation guidelines and focused mainly on deep retrofits, which provoked criticism. |

| European Green Deal (2019) [8] | Provided a strong political impetus for the energy renovation of buildings, including heritage assets, by mobilising funding and research initiatives. Nevertheless, the absence of explicit heritage references in the core document drew criticism from NGOs. Europa Nostra’s European Cultural Heritage Green Paper [62] highlighted how cultural heritage could actively support Green Deal objectives. It advocated for renovations that enhance energy efficiency while protecting cultural values—an approach increasingly reflected in subsequent EU initiatives. |

| Renovation Wave—European Commission Communication (COM, 2020) [5] | Directed governmental attention to the need for modernisation in the heritage sector. However, experts warned of potential risks: the European Commission Expert Group on Cultural Heritage and Climate Change (2020) cautioned that uncontrolled implementation of new energy technologies in historic structures could damage their authenticity more severely than climate impacts themselves. This led to the development of specialised guidance (e.g., EN 16883 standard [63]) and targeted funding mechanisms for heritage renovation (e.g., NFOŚiGW/FEnIKS programmes in Poland). Overall, the initiative was assessed positively as a catalyst for debate on “green” heritage revitalisation. |

| EU Strategy on Adaptation to Climate Change—European Commission Communication (2021) [4] | Linked to the European Green Deal and the Paris Agreement, complementing emission-reduction policies with an adaptation component. Implementation occurs via national adaptation plans and financial mechanisms (e.g., Climate Fund). From a cultural perspective, it refers to UNESCO and Council of Europe frameworks (e.g., Strategy 21 on Cultural Heritage) but lacks concrete instruments. Evaluation: Scholars and heritage experts criticised the omission of cultural aspects in adaptation planning, noting that the absence of heritage-specific guidelines weakens resilience to climate threats (e.g., extreme weather). In response, the EU Member States’ OMC Working Group produced the 2022 report Strengthening Cultural Heritage Resilience for Climate Change, recommending the inclusion of heritage in adaptation strategies and the development of risk assessment methodologies [64]. |

| New European Bauhaus (initiative, 2020–2021) [18] | Increased awareness that cultural heritage can serve as a valuable resource in the green transition, inspiring numerous revitalisation projects of historic spaces aligned with sustainable development principles. In Poland, adaptive reuse of post-industrial buildings and the renewal of historic housing estates received support as “NEB beacons.” Critics, however, emphasised that the initiative remains “soft”—it lacks regulatory force—so its success depends largely on adoption by national and local authorities. |

| Document (Year) | Impact on Heritage Conservation Practice and Evaluation |

|---|---|

| Polish Energy Policy to 2030 (2009) [19] | Impact: The policy set the direction for national energy legislation and programmes (e.g., the Energy Efficiency Act of 2011) but remained neutral regarding heritage protection. The omission of historic buildings was later criticised as a policy gap—between 2010 and 2015, heritage structures were not prioritised for energy upgrades, which perpetuated their poor energy performance. |

| National Energy Efficiency Action Plans (2014, 2017) [22] | Impact: These implementation plans formally acknowledged the specific character of heritage buildings, noting that cultural and technical constraints may prevent the use of standard modernisation methods. For example, the 2014 Plan states that: heritage-listed buildings form a distinct group… not all interventions or technical solutions can be applied. While aligned with the EED Directive and national energy policy, their practical influence was limited by the absence of dedicated funding tools. Some municipalities established revitalisation zones linking heritage renovation with energy efficiency (funded through Regional Operational Programmes). Scholars highlight that more detailed guidelines were needed—a gap addressed only after 2018. |

| Polish Energy Policy to 2040 (PEP2040, 2021) [11] | Evaluation: Both governmental and independent analyses pointed out that PEP2040 did not give sufficient attention to historic buildings. In practice, the responsibility for detailed regulation was transferred to the Long-Term Renovation Strategy and the Ministry of Culture. Experts noted that the lack of proactive, heritage-focused measures may hinder energy-efficiency goals, as this building group constitutes a significant portion of urban housing stock in historic city centres. |

| National Energy and Climate Plan 2021–2030 (KPEiK, 2019) [10] | Impact: Introduced the issue of post-industrial heritage as part of the energy transition, resulting in inventories and protection efforts for historic industrial sites (e.g., mines). Concerning building efficiency, it mainly described the challenges without proposing concrete solutions. Nonetheless, it served as a starting point for the development of the renovation strategy and raised awareness of heritage-related issues among other ministries. |

| Long-Term Building Renovation Strategy (DSRB, draft 2020; final 2022) [20] | Impact and Evaluation: The DSRB is the first Polish document to systemically address the thermal modernisation of heritage buildings. Its final version was positively evaluated by the conservation community for integrating their recommendations. However, the strategy’s ambitious goals for deep renovation were seen as difficult to achieve without additional funding and expertise. Pałubska and Zalasińska noted that the strategy enforces a new standard of collaboration between conservators and energy specialists—an improvement that still requires innovation to ensure authenticity-preserving modernisation [56]. |

| National Programme for the Protection of Monuments and the Care of Monuments 2019–2022 (adopted 2018) [22] | Impact: Marked a turning point by officially incorporating climate and energy themes into heritage policy. It produced key conservation guidelines (discussed below) that are now used by regional heritage authorities. Academic assessments are positive, noting that Poland was among the first countries in the region to develop comprehensive standards for “green” investments in heritage. The challenge remains continuity—future editions should broaden the scope of these initiatives. |

| Guidelines of the General Heritage Conservator: Thermomodernisation of Historic Buildings (2020) [23] | Practical Impact: Standardised conservation practice nationwide—previously, decisions were highly discretionary. Public investors (e.g., municipalities, parishes) now rely on these guidelines to prepare energy retrofit projects for heritage assets. Scholars regard them as a step forward, though their non-binding nature limits their enforcement. Further extensions are recommended, such as guidance on improving heating-system efficiency in addition to insulation. |

| Guidelines of the General Heritage Conservator: Photovoltaic Installations in Historic Buildings (2020) [24] | Impact: Significantly streamlined administrative practice—previously, decisions on PV systems in heritage sites varied by region. The guidelines now provide clarity for investors and a framework for conservators to reject harmful designs while approving well-integrated ones. In 2020, applications for PV systems on heritage buildings rose sharply (812 applications, over half approved), suggesting that the guidelines facilitated the legal implementation of properly designed projects. The literature recommends continued monitoring of these installations and periodic updates to reflect technological advances. |

| Code | Indicator Name | Calculation/Source | Result (2025) | Interpretation/Conclusions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| W1 | Number of immovable monuments | Based on NID database (2024): approx. 78,550 objects | 78,550 | The number of protected buildings in Poland has remained stable since 2015, with a slight increase (~2%) due to registry updates. |

| W2 | Number of conservation interventions | Estimate based on WKZ public reports and MKiDN annual statements—approx. 4800 per year, 40% involving construction works | ~48,000 (2015–2025) | The growing number of conservation interventions indicates increased renovation activity, though only part relates to energy measures. |

| W3 | Number of publicly funded projects | mapadotacji.gov.pl—2320 projects (2015–2025), about 18% involving heritage assets | 420 projects | Around 420 projects targeting heritage sites were identified within POIiŚ, ROP, KPO and NFOŚiGW programmes. |

| W4 | Share of energy projects among all conservation interventions | (420/48,000) × 100 | 0.9% | The very low share of energy-related projects among conservation works highlights the limited implementation of climate-oriented modernisations. |

| W5 | Average funding per energy project | Based on NFOŚiGW and ROP data: PLN 1.42 billion/420 projects | PLN 3.38 million | Energy projects in heritage buildings are relatively expensive due to technological and conservation requirements. |

| W6 | Share of regions with high intensity of thermal retrofits | (Number of Clean Air applications/number of monuments per voivodeship) × 1000 | avg. 13.6; max: Mazowieckie 21.4; min: Opolskie 7.9 | Regions with many heritage buildings also show high modernisation activity, increasing the risk of conservation conflicts. |

| W7 | Ratio of applications to conservation permits | (1,067,838/48,000) ≈ 22:1 | 22.2 | Only a small fraction of potentially relevant investments undergoes formal WKZ supervision. |

| W8 | Dynamics of heritage funding by MKiDN | Total grants increased: PLN 94 million (2015)→PLN 183 million (2024) | +95% | Although conservation funding nearly doubled, it did not translate into a proportional rise in energy retrofits. |

| W9 | Number of energy performance certificates for pre-1945 buildings | GUNB 2025 data: 62,000 certificates (~8% of total registry) | 62,000 | Low representation of historic buildings in the energy certificate registry confirms the limited uptake of energy audits. |

| W10 | Share of projects using innovative technologies (e.g., thermal coatings) | Qualitative review 2020–2025: ~25 EU pilot projects, 3 in Poland | 0.1% | Innovative technologies are used very rarely despite their high potential [63,64,65,66,67,68]. |

| W11 | Modernisation penetration rate | (420 energy projects/78,550 monuments) × 100 | ≈0.5% | Only half a percent of heritage buildings underwent energy modernisation—an indication of a major retrofit gap. |

| W12 | Regional conservation–energy conflict coefficient | (Projects without WKZ approval/all energy projects) × 100 | ≈40% | An estimated four in ten projects may have proceeded without full conservation oversight—posing a serious risk to authenticity. |

| Facility (Location) | Protection Status | Scope of Modernisation and Technologies | Results and Effects |

|---|---|---|---|

| Villetta Serra, Genoa (Italy) [76] | The building is listed in the register of monuments (local conservator) | Thermal modernisation ‘from the inside’: insulation of walls from the inside (while preserving the original façade); insulation of the ceiling above the basement and the roof; replacement of leaky windows from the 1970s with windows with a very low U-value (0.7–0.8 W/m2K); modernisation of the HVAC system—installation of a heat pump (ground source) with vertical probes and underfloor heating/cooling; optional mechanical ventilation system with heat recovery. Photovoltaic panels (hidden behind the parapet) have been discreetly integrated into the terrace to provide additional renewable energy. | The comprehensive modernisation will reduce the building’s energy demand by approx. 70–80%, bringing it closer to the nZEB standard. Simulations indicate that the walls will achieve a U-value of approx. 0.30 W/m2K (previously ~1.3) and that the strict insulation requirements for the roof and windows will be met. All work was carried out in consultation with the conservator—no changes were made to the historic façade, and new installations were placed non-invasively, using existing recesses and windows (e.g., free spaces near the staircase). This example proves that it is possible to reconcile the preservation of authenticity with the achievement of high energy efficiency. |