Abstract

This study identifies and refines the dimensions of cultural inheritance and innovative practices in industrial heritage-themed districts and develops a corresponding questionnaire scale. Based on the ABC model of attitudes, a conceptual model is constructed to examine the impact of cultural inheritance and innovation on tourist behavior, which is then empirically tested using Structural Equation Modeling (SEM). The findings reveal that the influence and mechanism of cultural inheritance and innovative practices on tourist behavior follow a continuous process in the sequence of cognition–affect–behavior tendency. All four dimensions of cultural inheritance and innovation exert a significant positive effect on tourist loyalty. Moreover, the affective component serves as a mediating factor within the chain reaction. This study constructs a new theoretical framework to explore how cultural inheritance and innovation jointly influence the formation of tourist loyalty and the underlying mechanisms, enriching the theoretical system of industrial heritage tourism and cultural management. It also provides practical theoretical support for district planning, design, and management.

1. Introduction

As China’s urban development shifts from “incremental expansion” to “stock optimization”, urban land use is gradually transitioning from a quantity-driven approach to a focus on high-quality development. The orderly renewal of stock land has become a crucial path to unlocking institutional dividends and stimulating urban vitality []. In this context, decaying industrial heritage spaces, as an essential component of urban renewal, are receiving increasing policy support and market attention. Industrial heritage-themed districts have rapidly emerged under the dual goals of “urban organic renewal” and “cultural heritage protection”, becoming new spatial forms that connect historical memory with contemporary life. Particularly in recent years, with the booming experience economy and the continuous upgrading of urban residents’ tourism and consumption needs, industrial heritage-themed districts, with their unique historical built environments and cultural context narratives, have gained increasing public favor and have gradually become important cultural tourism destinations in cities []. A number of iconic projects have emerged, such as Beijing’s Shougang Park, located at the venue for the 2022 Beijing Winter Olympics, which reinterprets the “steel memory” by transforming original industrial relics like blast furnaces, pipe corridors, and cooling towers into experiential and narrative cultural scenes. The park has also introduced extreme sports, art performances, and creative markets, achieving a complex multifunctionality and cultural value reconstruction []. The Shenyang 1905 Cultural and Creative Park uses old factory buildings as carriers, hosting cultural performances, art exhibitions, and market activities to rejuvenate the space, not only becoming a new landmark for Shenyang’s cultural tourism consumption but also being selected as part of the third batch of national-level night cultural and tourism consumption gathering areas in Liaoning Province []. In recent years, the Hangzhou Steel Factory site has followed the concept of “low-carbon” and “lifestyle aesthetics” to create a new urban cultural space, “Hangzhou Creative Town—Heart of Steel”, integrating industrial memory, ecological landscapes, and cultural consumption. This space attracts large numbers of young tourists to visit, consume, and participate in community activities []. Similar cases continue to emerge, reflecting the trend of industrial heritage tourism moving from “protective use” to “creative transformation”. To better meet tourists’ increasingly diverse cultural and affective needs, more and more industrial heritage-themed districts are actively seeking to carry out cultural innovation activities to create more distinctive experiential environments.

However, cultural heritage, as an important value resource that carries the historical memory and cultural identity of nations and regions, formed over a long time span, is fragile, scarce, and difficult to regenerate []. Compared to general themed districts, industrial heritage-themed districts have an inherent requirement for cultural inheritance, meaning that while they create opportunities for profit in urban environments, they must also provide high-quality experiences for visitors and minimize the negative impact on cultural inheritance of industrial heritage. In this process, conflicts are easily generated between cultural inheritance and innovative practices. If the cultural inheritance of heritage sites lacks long-term and effective planning, it will inevitably be destroyed by capital-driven innovation and renovation activities aimed at extracting profit. In such cases, the interdependence between cultural inheritance and innovation is often overlooked [], leading to the damage or even extinction of heritage value. Therefore, addressing the dialectical relationship between cultural inheritance and innovative practices in the development of industrial heritage-themed districts becomes a critical issue that must be faced for the sustainable development of these districts.

Moreover, it is important to clarify that the sustainable development of industrial heritage-themed districts has both market and social dual attributes []. A few scholars have already pointed out that the social value of heritage is a significant factor influencing heritage protection and value co-creation, and they emphasize the importance of integrating social aspects into destination management and planning []. Tourists, as an essential force influencing cultural consumption, tourism development, and social participation at destinations, play a key role in the long-term development of cultural inheritance and innovative practices in industrial heritage-themed districts. Therefore, how to dialectically handle the relationship between cultural inheritance and innovation to stimulate tourist loyalty requires urgent attention.

Currently, existing research lacks in-depth theoretical discussions on the relationship between cultural inheritance and innovative practices in industrial heritage-themed districts, particularly in terms of how these practices influence tourist loyalty. There is a lack of systematic structural measurement and quantitative analysis regarding the mechanisms through which cultural inheritance and innovation impact tourist loyalty. While existing literature addresses various aspects of cultural heritage conservation and innovative practices, most studies focus on the conservation aspect of cultural heritage, with less attention given to how cultural inheritance and innovation influence tourist behavior, especially in terms of their practical effects and pathways in shaping tourist loyalty, a key behavioral indicator. Therefore, this study aims to fill this academic gap by exploring how cultural inheritance and innovative practices jointly impact tourist loyalty in industrial heritage-themed districts, revealing the underlying mechanisms at play. Through this research, we will provide a new theoretical framework for industrial heritage-themed districts, clarifying the specific pathways of cultural inheritance and innovation in the formation of tourist loyalty and their interactive relationships. The significance of this study lies not only in enriching the theoretical system of industrial heritage tourism and cultural management but also in providing practical theoretical support for district planning, design, and management in practice.

2. Theoretical Introduction and Research Design

Effective cultural innovation practices have become an important pathway for enhancing the cultural capital of districts []. Due to their irreplaceable role in upgrading tourist experiences and shaping brand value, cultural innovation is gradually becoming the strategic core for the cultural sustainable development of industrial heritage-themed districts. This also reveals the dual characteristics of the sustainable development of industrial heritage-themed districts: on the one hand, it is necessary to adhere to cultural inheritance to preserve historical memory and spiritual core; on the other hand, cultural innovation must be promoted to continuously adapt to contemporary societal contexts and market demands, meeting the public’s expectations for diverse cultural experiences [,]. It can be said that there exists a dialectical relationship of unity and opposition between cultural inheritance and cultural innovation: cultural inheritance reflects the cultural foundation of the district, implicitly maintained through cultural content, distinctive features, historical atmosphere, and spiritual values [], whereas cultural innovation is expressed as proactive external reinterpretation, with its core elements including product marketing, spatial planning, design creativity, and business operations []. In this collaborative practice of inheritance and innovation, tourists, as active agents of cultural reception and reproduction, play a crucial role in connecting district cultural expression with sustainable development through their value recognition, behavioral preferences, and affective identification. Therefore, how to effectively stimulate tourists’ sense of place identity through cultural practices, encouraging their participation in co-creating cultural values, not only affects the short-term vitality of district operations but is also the core path to achieving long-term development and fulfilling the cultural mission of the district.

To further explore the impact and path of tourists’ cognitive understanding of cultural inheritance and innovative practices in industrial heritage-themed districts on their behavior, this study introduces the ABC Attitude Model theory as an explanatory framework. The ABC Attitude Model, originating in social psychology, is one of the most classic attitude models in the field, proposed by scholars such as Rosenberg, M.J. and Hovland, C. I. in 1960 []. In the ABC Attitude Model, attitude is regarded as a composite made up of three components: Cognitive, Affective, and Behavioral Tendencies, with the acronym “ABC” representing these three core elements. The model suggests that attitudes are not unidimensional but multidimensional, reflecting an individual’s comprehensive psychological response and behavioral orientation when facing something. The cognitive component refers to an individual’s knowledge, beliefs, and views about an object, or in other words, their understanding and evaluation of it. It involves people’s analysis of things; the affective component refers to an individual’s affective response, attitude, and feelings towards an object, including liking, disliking, or expressing some affective tone. The affective component primarily stems from the individual’s affective experience in a particular situation, often being spontaneous, intuitive, and not fully driven by rational analysis; the behavioral component refers to an individual’s behavioral tendencies or intentions towards an object, referring to actual actions or behavioral responses based on their attitudes in a specific context. Behavioral tendencies more directly reflect an individual’s “actual attitude”, representing the most direct manifestation of their attitude.

Over more than half a century of development, the application of the ABC Attitude Model has expanded across multiple fields, especially in recent years, where it has been widely used in the analysis and prediction of tourist and consumer behavior []. For example, Cui, Z.J. et al. (2025) applied the ABC Attitude Model to study the path of the impact of destination environment restorative cognition on tourist behavior []; Xiao, S.L. et al. (2022) based their research on the network presentation of tourism destination image using the ABC Attitude Model to analyze tourist behavior characteristics in Guizhou Province []; Dar, H. et al. (2025) discussed and validated the relationship between medical tourists’ satisfaction, attitudes, and loyalty through the application of the attitude model theory []; Chen, D.X. et al. (2025) applied the ABC Attitude Model to analyze tourist consumption willingness []. These studies demonstrate the rationality and effectiveness of the ABC Attitude Model in analyzing and predicting tourist behavior.

In this study, visitor experience in industrial heritage-themed districts is a highly affective process. Visitors’ attitudes are not only based on their knowledge and information but are also influenced by affective reactions, such as satisfaction [,]. Additionally, the perception of a tourism destination’s image is a multi-dimensional and multi-level complex concept, involving various levels of visitor responses including cognition, affect, and behavior []. The ABC model, by integrating these three aspects, offers a systematic perspective that helps comprehensively explain the formation and transformation of visitors’ attitudes during their visits to industrial heritage-themed districts. This aligns well with the objectives and needs of the present study.

This paper will adopt a two-phase research process to achieve its research objectives. First, by reviewing existing research and combining field research, the structural dimensions and measurement items related to visitors’ cognition, affect, and behavior regarding cultural inheritance and innovative practices in industrial heritage-themed districts will be refined and summarized to generate the corresponding measurement scale. Second, based on the ABC attitude model theory, hypotheses regarding the impact of cultural inheritance and innovative practices in industrial heritage-themed districts on visitors’ cognition, affect, and behavior will be proposed. Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) will be employed for empirical testing, and the results will be analyzed and summarized.

3. Scale Design

3.1. Indicator Dimensions and Conceptual Features

3.1.1. Cognitive Dimension Indicators and Conceptual Features

Under the framework of the ABC Attitude Model, tourists’ cognition of industrial heritage-themed districts’ cultural inheritance and innovative practices refers to their preliminary understanding and evaluation of the district’s cultural inheritance and innovative practices. This cognitive dimension represents tourists’ psychological responses to external cultural heritage preservation, innovative activities, and their interactive displays. It combines external stimuli (such as material heritage entities, environmental elements, cultural activities, etc.) with tourists’ internal needs (such as interest in history, cultural identity, etc.). Tourists’ cognition reflects not only their understanding of the knowledge and information related to cultural heritage and innovative practices but also their evaluation of the value, significance, and feasibility of these activities. This cognitive process forms the basis for tourists’ affective responses and behavioral tendencies, serving as an important starting point in influencing their attitudes and behavior.

Cultural inheritance practices mainly refer to the inheritance and preservation of both tangible and intangible cultural heritage in industrial heritage-themed districts. According to the UNESCO definition, tangible cultural heritage generally refers to physical heritage of historical, artistic, scientific, or social value, including buildings, sites, structures, and environmental elements such as “historical sites, buildings, cultural landscapes, and tangible heritage associated with a particular culture or ethnicity”. Intangible cultural heritage refers to cultural heritage centered on human spiritual activities, including performing arts, social customs, festivals, craftsmanship, and other cultural practices that lack a fixed physical form but are maintained through practices, transmission, and expressions [,]. Based on the disciplinary attributes of industrial heritage-themed district research and existing research, this paper defines tangible cultural heritage inheritance as the protection and continuation of physical heritage in industrial heritage, including historical buildings, industrial facilities, sites, and landscapes. The primary goal is to preserve and restore heritage with historical, cultural, and artistic value to ensure that it is not damaged or lost over time, maintaining its original structure, appearance, and function, thus providing future generations with direct historical experiences and cultural memories. According to relevant literature and field research, tangible cultural inheritance can be divided into five variables: architectural features, structural characteristics, spatial layout, buildings, and environmental elements []. Intangible cultural heritage inheritance refers to the protection and transmission of intangible cultural elements inherent in industrial heritage, such as craftsmanship, historical events, social memories, and cultural customs. Through exhibitions, promotion, artistic expressions, and cultural activities, these intangible cultural contents are passed down, enhancing social recognition and affective belonging, allowing them to be revived and represented in contemporary society and maintaining their vitality and continuity of inheritance []. It can mainly be divided into three variables: dynamic cultural display, cultural memory continuity, and interactive cultural display.

Cultural innovation refers to the process and outcome of innovating cultural products and services by altering cultural elements or content [,]. Considering the current characteristics of the research objects and drawing from existing research, this paper divides the cultural innovation practices in industrial heritage-themed districts into two major categories: cultural innovation design and cultural innovation transformation. Cultural innovation design refers to the modification of non-core parts of the heritage through innovative design techniques, ensuring that the structure, function, and aesthetics meet the needs of contemporary society without damaging the core values of industrial heritage. This design focuses not only on heritage protection and restoration but also on integrating modern culture, social functions, and aesthetic demands. Cultural innovation design can update the heritage’s external interfaces, optimize spatial layouts, and improve landscape designs, thus breathing new life into industrial heritage while maintaining its historical authenticity and cultural connotation. This design approach enhances the functionality of the heritage while improving its usability and sustainability in the modern urban context, providing visitors with a richer and more diverse cultural experience []. It can be divided into three variables: heritage interface updating, spatial atmosphere creation, and cultural landscape design []. Cultural innovation transformation refers to the extraction and recreation of core cultural elements based on industrial heritage cultural resources, expanding and developing them to create new cultural products and services in line with modern societal needs. This process includes the reinterpretation and innovative application of traditional heritage culture by transforming cultural elements, creating interactive experiences, and designing special activities to tightly connect heritage culture with contemporary life. The goal of cultural innovation transformation is to merge traditional industrial heritage with modern cultural consumption demands, promoting the vitality of heritage and increasing its market appeal and social value. It facilitates the transmission and recognition of industrial heritage in contemporary society. The main variables include cultural element transformation, cultural display interaction, special cultural activities, and cultural theme creation [,,].

3.1.2. Affective Dimension Indicators and Conceptual Features

According to the ABC attitude theory model, the formation of tourist destination behavior is a continuous process in the cognition–affect–behavior sequence. Affect, as a mediating variable between cognition and behavior, refers to the affective responses formed by tourists based on their cognition of the cultural inheritance and innovative practices in industrial heritage-themed districts. These affective responses include pleasure, satisfaction, a sense of belonging, and other affective factors that play a bridging role in the formation of attitudes. In this study, satisfaction, a widely adopted comprehensive indicator, is selected to represent the affective aspect [,].

Satisfaction theory is an important theory in consumer behavior, tourism management, and other fields. One of the classic theories in satisfaction research is the Expectancy Disconfirmation Theory, proposed by Oliver, R. L. (1980) []. The theory suggests that customer satisfaction results from the comparison between customers’ expectations and actual experiences. When actual experiences exceed expectations, customers feel satisfied; when actual experiences fall short of expectations, customers are dissatisfied. Expectancy Disconfirmation Theory emphasizes that customer satisfaction is not only influenced by expectations but also by the quality of the actual experience and the performance of the service provider. Additionally, there is the Affective Response Theory proposed by Keng K.A. et al. (2004) [], which suggests that customer or tourist satisfaction is an affective response to a product or service based on cognitive evaluations. It represents the feelings of pleasure or fulfillment formed during the experience. Satisfaction theory is widely used to study the relationship between tourists’ or consumers’ evaluations of products or services and their behavioral intentions [,,]. Based on the related theoretical content and existing research, this study selects three variables as the observation variables for the satisfaction dimension: overall experience satisfaction, satisfaction compared to expectations, and satisfaction compared to similar attractions.

3.1.3. Behavioral Dimension Indicators and Conceptual Features

Tourist behavior research is a core subject in the field of tourism, aiming to understand the decision-making process, behavior patterns, and motivations of tourists, which provides the basis for destination operational decisions. The theoretical framework of tourist behavior research covers various psychological, sociological, and marketing theories, such as motivation theory, attitude theory, and social exchange theory [,]. Among these, the ABC attitude theory is most widely applied in tourist behavior research, which suggests that tourist behavior is the final behavioral response based on cognition and affect. In the description of tourist behavior, the concept of tourist loyalty, proposed by Dick and Basu (1994), is regarded as one of the most important and comprehensive research indicators in tourist behavior []. In this study, tourist loyalty is also selected as the comprehensive indicator for tourist behavior. Based on relevant theories and existing research, this study selects three variables as the observation variables for the tourist loyalty dimension: intention to revisit, intention to recommend, and intention to maintain.

In summary, this study ultimately forms the structure and measurement index system of the three dimensions of “cognition–affect–behavior” (see Table 1) and provides definitions and descriptions for the corresponding measurement indicators (see Table 2).

Table 1.

Measurement indicator system and references.

Table 2.

Definitions of observed variables.

3.2. Selection of Sample Subjects

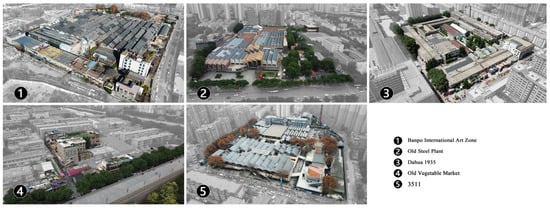

In line with the thematic requirements of this study, five representative industrial heritage-themed districts in Xi’an were selected as research samples: Banpo International Art Zone, Old Steel Plant, Dahua 1935, Old Vegetable Market, and 3511 (see Figure 1). These districts are characterized by distinct heritage themes and prominent spatial features. Spanning multiple phases of China’s development, they encompass various aspects of Xi’an’s modern and contemporary urban evolution and social life. Their historical environments, spatial configurations, and architectural styles each bear distinctive characteristics and reflect strong imprints of their respective eras. These features collectively reveal the industrial development trajectory of the city and demonstrate significant historical and social value, thus meeting the preliminary requirements of this study. Additionally, the selected districts possess favorable sampling conditions, such as substantial spatial scale, stable operational status, high visitor traffic, and spatially non-contiguous distribution, all of which align with the objective criteria for sample selection.

Figure 1.

Aerial view of the current status of research cases.

3.3. Structure of the Measurement Scale

The design of the measurement scale in this study adheres to the general principles of clarity of purpose, structural coherence, and simplicity. Following the principle of progressive communication and drawing on the theoretical model and research framework, the questionnaire is divided into two main sections. The first section collects basic demographic information about the respondents, including gender, age, and occupation, based on the needs of this study. The second section measures respondents’ cognition, affect, and behavior tendency regarding cultural inheritance and innovative practices in industrial heritage-themed districts. All variables are measured using a five-point Likert scale, where 1 indicates “strongly disagree” and 5 indicates “strongly agree”.

3.4. Data Collection and Sample Characteristics

From April 2024 to December 2024, the author conducted six rounds of field-based survey research in five industrial heritage-themed districts, distributing a total of 280 questionnaires. The research adopted a one-on-one interview-style questionnaire survey, where researchers or trained assistants engaged in face-to-face communication with visitors in the districts, guiding them in completing the questionnaires and collecting them on-site. The questionnaire distribution was conducted within the districts, effectively ensuring that the survey subjects were actual visitors who participated in the district experiences, thus ensuring the relevance and representativeness of the sample while avoiding interference variables caused by online distribution or sampling from outside the district. Additionally, the one-on-one interview approach allowed for the timely explanation of professional terms or unclear questions to respondents, reducing errors or omissions and significantly improving the validity and reliability of the questionnaire data. After excluding invalid questionnaires, a total of 269 valid questionnaires were collected from the 6 rounds of field surveys, resulting in a 96% valid recovery rate. Among the valid samples, the gender distribution showed a slight majority of females, with 141 females and 128 males. The age structure of the respondents was primarily between 20 and 60 years old, with 127 valid samples from the 21–30 age group, 95 valid samples from the 31–60 age group, and 47 valid samples from other age ranges. In terms of educational background, 29 respondents had a high school or lower level of education, 203 respondents held a bachelor’s degree, and 37 respondents had a master’s degree or higher. The professional distribution was notably dominated by company employees, with 56 respondents, while the rest of the categories were more dispersed.

4. Model Construction and Analysis

This study systematically collects firsthand cognitive and behavioral response data from tourists in industrial heritage-themed districts through field survey questionnaires, laying the data foundation for achieving the research objectives. Exploring tourists’ perceptions of cultural inheritance and innovative practices in industrial heritage-themed districts and how these perceptions influence tourist satisfaction and behavioral intentions is one of the core research tasks of this study. During the research process, how to integrate the semantic information of various measurement indicators, quantify the interactive relationships between different variables, and clarify the weight distribution between the paths are key challenges in data analysis. It is particularly important to note that the core variables involved in this study are latent variables that cannot be directly observed, which makes it difficult for traditional statistical methods—such as multiple linear regression and path analysis—to effectively handle the co-existence of latent and observed variables and the complex interactions between variables. Therefore, in order to more scientifically construct and test the mechanism of tourist behavior formation, this study introduces Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) as the core analytical tool.

SEM combines the advantages of traditional multivariate statistical methods such as factor analysis and path analysis, establishing an organic linkage between the measurement model and the structural model. It can achieve indirect measurement of abstract latent variables and reveal the complex causal path relationships between variables. Compared to traditional methods, SEM has significant advantages in handling multiple latent variables, multiple observed indicators, and multi-path interaction structures, especially suitable for the cognition–affect–behavior theoretical model constructed in this study. Additionally, SEM demonstrates powerful functionality in testing and estimating mediation effects, allowing for the simultaneous examination of both direct and indirect path influences within the overall model framework, providing a more precise and systematic analysis of the mediation mechanism. Compared with traditional stepwise regression methods, SEM not only improves estimation accuracy by controlling for measurement errors but also visually presents the mediation paths between variables, helping to better understand the underlying logic of how tourists’ perceptions influence their behavior decisions. Furthermore, SEM provides a systematic model fitting evaluation mechanism, which can test the goodness of fit between the model structure and actual data, further enhancing the explanatory power of the model and theoretical support.

4.1. Model Hypotheses

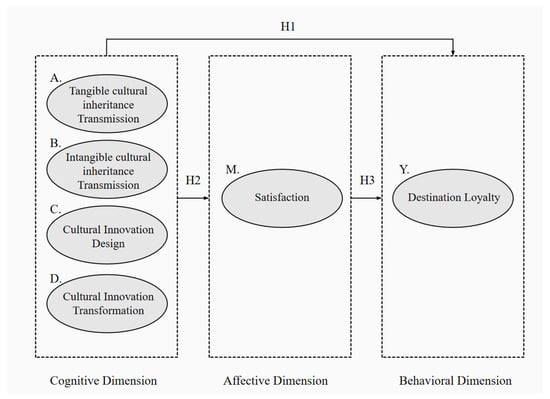

Based on the hypothesis of the ABC attitude theory model and the analysis of the path relationships between cognition, affect, and behavior discussed above, this study is based on the following hypotheses:

H1.

Cultural inheritance and innovative practices in industrial heritage-themed districts positively affect tourist loyalty.

H2.

Satisfaction plays a positive mediating role between cognition of cultural inheritance and innovative practices in industrial heritage-themed districts and tourist loyalty.

H3.

Satisfaction has a significant positive effect on tourist loyalty to the destination.

Based on the attitude model and the analysis above, a hypothetical structural relationship model is constructed for the influence of cultural inheritance and innovative practices in industrial heritage-themed districts on tourist loyalty (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Hypothetical structural model.

4.2. Indicator Dimensions and Conceptual Characteristics

To ensure the scientific rigor and reliability of the research results, and to determine whether the sample data are suitable for further factor analysis, it is necessary to conduct systematic reliability and validity tests on the questionnaire data. Reliability and validity analysis is not only an important means of evaluating the quality of the scale but also a fundamental basis for ensuring the validity of data analysis and the reliability of research conclusions. For reliability testing, this study uses Cronbach’s alpha coefficient to evaluate the internal consistency of the scale. Generally, when Cronbach’s α value is greater than 0.6, the scale has good internal reliability and can reflect a high level of consistency between the items []. For validity testing, this study employs the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) test and Bartlett’s sphericity test to perform a preliminary analysis of the structural adequacy of the data and the correlations between variables. When the KMO value is greater than 0.5 and Bartlett’s sphericity test achieves a significant level (Sig. < 0.05), it indicates that there is a correlation between the variables, and the data is suitable for further factor analysis []. The relevant value standards are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Standards for Cronbach’s alpha and KMO values.

In the specific process, this study used the reliability and validity analysis module of SPSS 26.0 software to test the scale. The results show that the Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for all dimensions are above 0.7, indicating that the scale has good internal consistency. The KMO values are all greater than 0.5, and the Bartlett’s test of sphericity reaches a significant level, indicating that the data are suitable for factor analysis (see Table 4). Overall, the scale demonstrates good reliability and validity, meeting the prerequisite conditions for subsequent factor analysis.

Table 4.

Reliability and validity testing of the questionnaire.

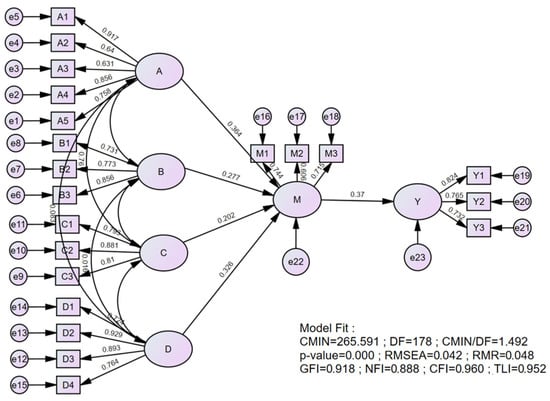

To further clarify the relationships between the factors in the model, this study introduces AMOS 24.0 software to construct the model (see Figure 3) and to examine the rationality of its structural relationships and model fit. A confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was performed on all constructs, and the results showed that all factor loadings were between 0.65 and 0.95 and were significant (p < 0.05). The composite reliability (CR) ranged from 0.8 to 0.9, and the average variance extracted (AVE) was greater than 0.5, meeting the standards proposed by Hair, J. F. (2010) and others [,]. Furthermore, the model fit indices were examined, and the results showed that the goodness-of-fit index (GFI = 0.918), root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA = 0.042), and incremental fit index (IFI = 0.960), along with other key indicators, were within the acceptable range (see Table 5) [,,], indicating that the model demonstrated a good fit and could be used to output results.

Figure 3.

Structural relationships and model parameters.

Table 5.

Model fit indices and evaluation results.

4.3. Model Results Output

To more intuitively demonstrate the mutual influence between latent variables and the observed variables within these latent variables in the structural equation model, we used AMOS 24.0 software to perform standardized parameter estimation of the model path coefficients. The results show that all paths exhibit significant positive effects (p < 0.05), indicating that the hypothesized relationships between the variables are statistically supported and the correlations are significant and reliable (see Table 6).

Table 6.

Path coefficient estimates of the structural model.

Specifically, the dimension of material cultural inheritance (A→M, path coefficient 0.364) has the strongest influence on the mediating variable of satisfaction, indicating that this dimension plays a significant role in enhancing tourist satisfaction. From the perspective of effect size, the material heritage cultural inheritance dimension is a key driver in the cognition–affect–behavior chain of tourists. Secondly, the dimension of cultural innovation transformation (D→M, path coefficient 0.326) also shows a strong influence, indicating that innovative practices are equally important in enhancing satisfaction. Other path coefficients, such as those for intangible cultural heritage inheritance (B→M, path coefficient 0.277) and cultural innovation design (C→M, path coefficient 0.202), are relatively smaller but still show statistically significant positive effects, indicating that these dimensions collectively contribute to the formation of tourist satisfaction. Furthermore, the influence of satisfaction on tourist loyalty (M→Y, path coefficient 0.370) is significant and strong, demonstrating that satisfaction plays a key and significant role in promoting tourist loyalty.

To further validate the mediating role of tourist satisfaction in the influence mechanism from tourists’ cognition to their loyalty, this study employs the bootstrap method to test the significance and effect strength of each mediation path. The mediation effect is an important pathway mechanism to explore how independent variables indirectly affect dependent variables through mediating variables, and it plays a crucial role in revealing the internal transmission mechanisms between variables. In the “cognition–affect–behavior” theoretical framework constructed in this study, satisfaction is set as the key mediating variable to measure how tourists’ evaluation of cultural cognition content is further transformed into behavioral intentions (such as tourist loyalty).

In the analysis of the mediation effect, traditional causal step methods (e.g., the Baron and Kenny method) have certain limitations when handling multiple paths and latent variable relationships, especially when the sample size is limited or the distribution deviates from normality. In contrast, the bootstrap method, as a non-parametric resampling-based test, does not rely on the normal distribution assumption and can more robustly assess the significance of mediation effects and confidence intervals. It has been widely applied in mediation analysis within structural equation models. This study uses repeated sampling to construct 95% confidence intervals and evaluates the statistical significance of each mediation path using the bias-corrected percentile method [].

The results show that the mediating effect values for all mediating paths are statistically significant (p < 0.05), and the bootstrap confidence intervals do not include 0, indicating that the mediating effect is valid. Tourist satisfaction plays a substantial role in multiple paths (see Table 7). Specifically, the mediating effect value for path A_M_Y is 0.142 (p < 0.01), with a direct effect value of 0.250 (p < 0.001), and the mediating effect accounts for 36.22% of the total effect. The mediating effect value for path B_M_Y is 0.083 (p < 0.05), with a direct effect value of 0.183 (p < 0.001), and the mediating effect accounts for 31.56%. The mediating effect value for path C_M_Y is 0.067 (p < 0.01), with a direct effect value of 0.210 (p < 0.001), and the mediating effect accounts for 24.19%. For path D_M_Y, the mediating effect value is 0.132 (p < 0.05), with a direct effect value of 0.190 (p < 0.001), and the mediating effect accounts for 40.99%. The bootstrap confidence intervals for all paths do not include 0, further validating the significance and robustness of the mediating effect.

Table 7.

Mediating effect analysis.

To illustrate using path A_M_Y, for every 1-unit increase in tourists’ positive cognition of industrial heritage-themed districts’ material cultural inheritance practices, tourist loyalty increases by 0.142 units through an enhancement of tourist satisfaction. In this path, the mediating effect accounts for 36.22%, indicating that satisfaction plays a significant bridging role in the effect of this cognitive variable on tourist loyalty. This means that tourists’ positive cognition of industrial heritage-themed districts’ cultural inheritance practices not only directly stimulates their behavioral intention but also indirectly amplifies the effect of tourist loyalty by enhancing their subjective satisfaction.

In these four paths, the mediating variable plays a significant mediating role in each path, with the mediating effect proportion ranging from 24.19% to 40.99%, showing that the mediating variable plays an important role in different cognition dimensions’ behavioral impact paths. It also reflects that the impact paths of various cognitive factors on tourist behavior are not equivalent but rather exhibit differences in intensity and structure. Among these, the mediating effect proportion in path D_M_Y is the highest at 40.99%, suggesting that the cognition of cultural innovation transformation in improving tourist loyalty more heavily relies on the affective transmission mechanism of satisfaction. In other words, the more positively tourists perceive the cultural innovation practices in aspects like cultural content, thematic activities, and interactive experiences in industrial heritage-themed districts, the greater the potential for enhancing their subjective satisfaction, which in turn significantly promotes their tourist loyalty. This means that optimizing and enhancing tourists’ experience and affective engagement in the cultural innovation transformation dimension will yield considerable benefits.

This result empirically supports the “cognition–affect–behavior” theoretical logic chain, demonstrating that tourists’ cognition of the district’s cultural inheritance and innovative practices does not directly translate into tourist loyalty but rather requires an intermediary step of subjective satisfaction, which in turn triggers corresponding behavioral responses.

Theoretically, the higher proportion of mediating effects strengthens the central role of the affective variable in the conversion between cognition and behavior, providing a more explanatory model for the attitude–behavior formation mechanism. From a practical perspective, the result highlights the operability and intervention value of satisfaction as a key influencing factor, suggesting that during district operations, enhancing the overall satisfaction of tourists by optimizing their experience and affective engagement pathways will effectively strengthen their loyalty behaviors, such as revisiting, recommending, and maintaining the district.

4.4. Results Analysis

In summary, the research results support initial hypotheses H1, H2, and H3, verifying that tourists’ cognition of cultural inheritance and innovative practices in industrial heritage-themed districts significantly affects their loyalty behavior through the mediating role of satisfaction in the theoretical model.

The overall analysis results indicate that there are differences in the influence of cultural inheritance and innovative practices on tourist behavior. Specifically, the two paths of cultural inheritance (A_M_Y, B_M_Y) have a higher impact coefficient on tourist satisfaction and loyalty than the paths of cultural innovation practices (C_M_Y, D_M_Y). Among them, the practice of material heritage cultural inheritance has a more significant impact on enhancing tourist satisfaction compared to non-material heritage cultural inheritance. Additionally, its mediation effect and its proportion of the total effect are higher than those of the non-material cultural inheritance dimension. This suggests that the protection and display of material cultural heritage plays a core role in enhancing tourists’ emotional identification and behavioral tendencies, especially in promoting tourist loyalty.

In detail, tourists’ cognition and reception of material cultural elements in the district—such as physical entities, spatial forms, and architectural features—are more direct and can be experienced through tactile, visual, and other sensory perceptions. These material cultural elements form the foundation of tourists’ cultural identity and emotional connection with the district, and by increasing their satisfaction, further enhance their loyalty. This direct cultural experience and emotional investment make material heritage cultural inheritance a key factor in enhancing tourist loyalty. In contrast, the role of non-material heritage cultural inheritance practices in influencing tourist behavior is relatively weaker. Although non-material cultural elements can spark tourists’ interest in some aspects, due to their abstract nature and reliance on activities, performances, and interactive forms of expression, tourists’ direct perception of them is weaker, leading to a relatively weaker impact on tourist satisfaction and loyalty.

Regarding cultural innovation practices, the analysis results show that the cultural innovation design dimension has a greater impact on tourist satisfaction and loyalty than the cultural innovation transformation dimension. Specifically, cultural innovation design focuses on the reinterpretation of cultural content and artistic expression. It attracts tourists’ attention through innovative design approaches and enhances their cultural cognition and emotional resonance. However, although cultural innovation design can somewhat increase tourist satisfaction, its mediation effect and its proportion of the total effect are noticeably lower than those of the cultural innovation transformation dimension. This phenomenon indicates that the cultural innovation transformation dimension is more effective in indirectly enhancing tourist loyalty through improving satisfaction compared to the cultural innovation design dimension. Cultural innovation transformation not only involves innovation in cultural forms but also includes specific experiential projects and activity arrangements. These experiential activities directly interact with tourists’ emotions and behaviors, increasing their sense of participation, interaction, and immersion. Therefore, this dimension is more effective in enhancing tourist loyalty by indirectly improving satisfaction. This suggests that, in the future optimization and upgrading of industrial heritage-themed districts, more experiential and interactive projects, such as cultural performances and immersive experiences, should be included in the cultural innovation transformation dimension to strengthen tourists’ emotional investment, improve their overall experience quality, and ultimately achieve higher satisfaction.

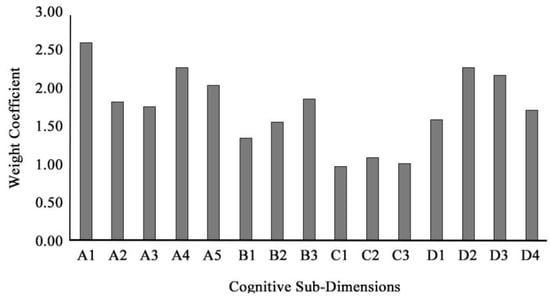

Furthermore, to further analyze the strength of the influence of different constructs on behavioral variables, we normalized the data for the observed variables of each construct and set the minimum load factor for each indicator to 1 to achieve cross-comparative analysis (see Figure 4). The results show that some sub-dimensions oriented toward participatory experiences, such as interactive experiences (D2), distinctive cultural activities (D3), and cultural performances (B3), exhibit high load factors. These sub-items are often new activity mechanisms introduced into the district’s cultural expression and spatial operation, characterized by strong immersion and interactivity, which can effectively stimulate tourists’ emotional investment and sense of participation, significantly enhancing overall satisfaction and subsequent behavioral intentions.

Figure 4.

Analysis of the influence weights of cognitive sub-dimensions.

Overall, the factors influencing tourist loyalty include not only the cognitive recognition of effective cultural heritage preservation and innovative practices in Industrial Heritage-Themed Districts, but also the perceived quality of experience during the actual participation process. Particularly in the context of contemporary cultural consumption and urban renewal, cultural inheritance and innovative practices are no longer static displays but emphasize dynamic interaction with tourists. Therefore, districts should enhance material heritage protection while further enriching experiential scenarios and activities, improving tourists’ emotional satisfaction and behavioral engagement and achieving the dual goals of cultural value dissemination and sustainable operation.

5. Conclusions and Implications

5.1. Research Conclusions

- (1)

- The influence of cultural inheritance and innovative practices in industrial heritage-themed districts on tourist behavior aligns with the classic attitude chain mechanism, presenting a continuous and ordered process of cognition–affect–behavior. In this process, the inheritance of heritage culture and innovative expression in the district act as driving forces, laying the foundation for the formation of tourist attitudes and behavioral transformation.

- (2)

- Both cultural inheritance and innovative practices have a significant positive impact on tourist loyalty, effectively stimulating tourists’ active loyalty behavior regarding heritage protection and value co-creation. Overall, the influence of cultural inheritance is significantly stronger than that of cultural innovation, especially in terms of material heritage, where cultural inheritance practices have the most significant impact, while the effect of cultural innovation design practices is relatively weak.

- (3)

- The results further indicate that the cognitive component of tourist attitudes influences the behavioral component through the affective component, forming an internal transmission mechanism for tourist loyalty in industrial heritage-themed districts. In this, satisfaction within the affective component plays a key mediating role as a bridge and link to promote the conversion from cognition to behavior.

5.2. Research Implications and Significance

5.2.1. Research Implications

- (1)

- Constructing a “Genetic Variation” Collaborative Evolution Double Helix Structure: This study reveals the dialectical relationship between cultural inheritance and innovation in industrial heritage-themed districts, suggesting the establishment of a “genetic variation” collaborative evolution double helix structure. Cultural inheritance should serve as the “genetic” dimension to ensure the stability of the district’s history and collective memory, while cultural innovation, as the “variation” dimension, should create new meanings suited to modern society. This structure helps balance the conflicts between cultural inheritance and innovation, avoiding excessive deconstruction or stagnation of cultural values and spatial features. It is important to be cautious of excessive cultural layering, which may result in the loss of historical authenticity and fragmented identity recognition.

- (2)

- Shifting from “Space Display” to “Behavior Programming” as an Activation Path: The cultural revitalization of the district should not only showcase heritage but also encourage tourist participation. High-involvement interactive experience design transforms tourists from “bystanders” to “co-creators”, further enhancing their affective investment and loyalty. This sense of participation can generate viral word-of-mouth through social sharing, contributing to the long-term vitality of the district and the construction of tourist loyalty. Therefore, the district should incorporate more elements such as production activity experiences, digital interaction, and cultural theme activities in the process of cultural innovation conversion, guiding tourists’ affective and behavioral engagement. This design will enable industrial heritage-themed districts to not only preserve historical authenticity but also activate their contemporary vitality as “social scenes”.

5.2.2. Theoretical Contributions and Limitations

This study constructs a theoretical model for the influence path of tourist loyalty in industrial heritage-themed districts and empirically tests it. The study delves into the components and roles of cognition, affect, and behavior in the path, particularly validating the mediating effect, proving that satisfaction plays a significant mediating role in the path. This finding provides theoretical guidance for the operation and upgrading of the district.

In response to the widespread issue of destructive development under the guise of “cultural innovation” in industrial heritage-themed districts, this paper proposes a universally applicable and transferable theoretical method. This method is not only applicable to the Xi’an area but can also be effectively applied to other regions. Through the development of this method and the output of research results, district managers can clearly identify the focus of development and optimization while uncovering the underlying logical relationships, thus avoiding irreversible damage to heritage values caused by blind development.

However, we must also acknowledge that the findings of this study have certain limitations. On a global scale, the conclusions drawn in this study may not be applicable to all industrial heritage-themed districts, as regional differences may lead to variations in tourist demands and behavioral patterns. This presents a direction for further research expansion. These regional differences may manifest in the following ways: in some areas, tourists may place more emphasis on experience-based consumption and interactive experiences, making the cultural innovation conversion dimension potentially more influential, while in other areas, tourists may focus more on historical sentiment and cultural identity, which would require different approaches for district development and optimization. These differences likely reflect the specific regional background and social needs. Therefore, when addressing different regional characteristics, it is recommended to conduct new data collection and validation based on the research methods used in this paper to ensure that the research results and conclusions are appropriate for specific regions.

Author Contributions

Q.T.: investigation, software, data curation, conceptualization, methodology, writing—original draft; J.W.: resources, validation, supervision, writing—review, funding acquisition; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Yu, B.; Hu, Y.; Zhou, X. Can administrative division adjustment improve urban land use efficiency? Evidence from “Revoke County to Urban District” in China. Environ. Plan. B Urban Anal. City Sci. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J. Research on Landscape Renewal of Urban Historical and Cultural Themed Commercial Districts from the Perspective of Experience Economy. Master’s Thesis, Shenyang Jianzhu University, Shenyang, China, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Yue, X.; Cai, F.; Zhao, M. Research on Industrial Heritage Tourism Development Strategies Based on Cultural Memory: A Case Study of Beijing Shougang Park. Sino-Foreign Cult. Exch. 2025, 128–130. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X. Research on the Development Strategies of Industrial Heritage Tourism in Liaoning Province. North. Econ. Trade 2024, 4–7. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, S.; Wu, Y.; He, Y. Discussion on the Strategy of Cultural Memory Valuation and Place Regeneration under the Context of Public Heritage: A Case Study of the Industrial Heritage Conservation Practice of Hangzhou Steel Plant. Archit. Herit. 2025, 33–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, G. Cultural tourism: A review of recent research and trends. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2018, 36, 12–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fei, G. Research on Value Evaluation of the Chinese Eastern Railway Industrial Heritages from Perspective of Heritage Corridor. Ph.D. Thesis, Shenyang Jianzhu University, Shenyang, China, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Santa, D.; Tiatco, A. Tourism, heritage and cultural performance: Developing a modality of heritage tourism. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2019, 31, 301–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pai, C.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Li, K.; Shang, Y. Current challenges and opportunities in cultural heritage preservation through sustainable tourism practices. Curr. Issues Tour. 2025, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S. From Cultural Heritage to Creative Cities: The Extension of Cultural Heritage Protection System. Urban Archit. 2013, 21–24. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, H.; Zhang, H.; Feng, Y. Inheritance or Reshaping? Research on the Activation Mode and Mechanism of Local Time honored Brands: Based on the Perspective of Brand Authenticity and Value Transfer. Manag. World 2018, 34, 146–161. [Google Scholar]

- Tao, R.; Nobuo, A. From Criticism to Dialogue and Construction: Local Re cognition of the Critical Heritage Research Paradigm. Chin. Cult. Herit. 2023, 4–11. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, S.N.; Li, Y.Q.; Liu, C.H.; Ruan, W.Q. A study on China’s time-honored catering brands: Achieving new inheritance of traditional brands. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 58, 102290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trunfio, M.; Campana, S. Drivers and emerging innovations in knowledge-based destinations: Towards a research agenda. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2019, 14, 100370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hovland, C.I.; Rosenberg, M.J.; McGuire, W.J. Attitude Organization and Change: An Analysis of Consistency Among Attitude Components; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, X.; Xi, L.; Esther Kou, I.; Su, X. Macau residents’attitude towards the free independent travellers (FIT) policy: An analysis from the perspective of the ABC model and group comparison. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2021, 26, 935–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, C. Research on the Influence Mechanism of Destination Environmental Restorative Perception on Hot Spring Tourists’ Loyalty. Master’s Thesis, Shandong University, Jinan, China, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, X.; He, Y.; Min, Z. Research on the Network Presentation of Tourism Scenic Spot Image Based on ABC Attitude Model—Taking 5A and 4A Level Scenic Spots in Guizhou Province as an Example. Resour. Dev. Mark. 2022, 38, 650–656. [Google Scholar]

- Dar, H.; Kashyap, K. Structural equation modeling (SEM) approach for envisaging the connotation among medical tourists’ satisfaction, attitude and loyalty: A case of Delhi-NCR, India. Int. J. Spa Wellness 2025, 246–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, C.; Wang, Y.; Deng, Q. Research on the Factors Influencing the Tourism Consumption Willingness of Chongqing Space Capsule Rural Homestays. Adv. Soc. Sci. 2025, 14, 121. [Google Scholar]

- Inés, K.; Natalia, V. A netnographic study to understand the determinants of experiential tourism destinations. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2024, 11, 862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnould, E.J.; Price, L.L. River magic: Extraordinary experience and the extended service encounter. J. Consum. Res. 1993, 20, 24–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Zhang, Y. Research on the Perception of Nanjing City’s Tourism Destination Image Based on User-Generated Content—Taking Tripadvisor Reviews by Japanese Tourists as an Example. Geogr. Sci. Res. 2023, 12, 683. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.Y. “The Future on the Ruins: UNESCO, World Heritage and the Dream of Peace”: Reflecting on World Heritage from its Origins, Mechanism, and Practice. China Cult. Herit. 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, J. An Analysis of the Integrity of Modern Industrial Heritage: Analysis on the Integrity of Modern Industrial Heritage: Perspectives from the Nizhny Tagil Charter and Dublin Principles. New Archit. 2019, 92–95. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Industry and Information Technology of the People’s Republic of China. Management Measures for National Industrial Heritage; Ministry of Industry and Information Technology Political and Legal Affairs: Beijing, China, 2023; Volume 24. [Google Scholar]

- WW/T0091-2018; Norms for the Protection and Utilization of Cultural Relics—Industrial Heritage. Relevant Laws and Regulations of the National Cultural Heritage Administration. National Cultural Heritage Administration of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2018.

- Khan, J.; Mir, A. Ambidextrous culture, contextual ambidexterity and new product innovations: The role of organizational slack and environmental factors. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2019, 28, 652–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. The 2009 UNESCO Framework for Cultural Statistics (FCS); UNESCO Institute for Statistics: Montreal, QC, Canada, 2009; pp. 18–31. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Sui, Q.; Lv, Y. Preliminary exploration of industrial heritage value standards and suitability reuse models. Archit. J. 2010, 29–32. [Google Scholar]

- Gong, K.; Ji, Y. Investigation and Research on the Renovation of Industrial Architectural Heritage in Nanjing: A Case Study of 1865 Creative Industry Park. Archit. J. 2010, 29–32. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Tweed, C. Research on the Renewal of Industrial Heritage from the Perspective of Industrial Protection and Inheritance: A Case Study of the United Kingdom. Archit. J. 2019, 94–98. [Google Scholar]

- Jing, W.; Hao, L.; Hui, W. Protection and Renewal of Urban Industrial Heritage: An Important Approach to Building Creative Cities. Urban Plan. Int. 2012, 27, 60–64. [Google Scholar]

- Zhi, Q. Value Chain Reconstruction and Landscape Revitalization of Industrial Heritage: A Case Study of the Renovation of Banpo International Art Park in Northwest China’s First Printing and Dyeing Factory. Chin. Landsc. Archit. 2017, 33, 96–100. [Google Scholar]

- Tahir, A.H.; Adnan, M.; Saeed, Z. The impact of brand image on customer satisfaction and brand loyalty: A systematic literature review. Heliyon 2024, 10, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeithaml, V.A.; Berry, L.L.; Parasuraman, A. The behavioral consequences of service quality. J. Mark. 1996, 60, 31–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, R.L. A cognitive model of the antecedents and consequences of satisfaction decisions. J. Mark. Res. 1980, 17, 460–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keng, K.A.; Huang, T.H.; Zheng, L.X. Consumer emotions in service encounters: The influence of the service provider. J. Serv. Mark. 2004, 18, 414–428. [Google Scholar]

- Maki, F.; Sano, K.; Sun, H. How Do International and Domestic Tourists Perceive the Service Quality of Japanese Ryokans? A Cross-Cultural Perspective. J. Qual. Assur. Hosp. Tour. 2025, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Q.; Sun, M.; Shi, W.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, W.; Jing, Y. Perceptions of Destination Image Among Japanese Tourists Toward the Hong Kong and Macau Regions of China: An Analysis Based on Online Reviews. Res. Sq. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Z.; Qi, W. Study on Tourists’ Perception of Authenticity, Satisfaction, and Revisit Intention in Antique Town-Type Tourism Scenic Areas—A Case Study of Taihu Ancient Town in Huzhou, Zhejiang. Tour. Res. 2024, 16, 45–55. [Google Scholar]

- Vujičić, M.D.; Kennell, J.; Morrison, A.; Filimonau, V.; Štajner Papuga, I.; Stankov, U.; Vasiljević, D.A. Fuzzy modelling of tourist motivation: An age-related model for sustainable, multi-attraction, urban destinations. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muler González, V.M.; Galí, N.; Coromina, L. Residents’ Perceptions of Tourism Social Exchange Relations: A Case Study in a Small Heritage Town. Investig. Tur. 2023, 100–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dick, A.S.; Basu, K. Customer loyalty: Toward an integrated conceptual framework. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1994, 22, 99–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cronbach, L. Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika 1951, 16, 297–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, H.F. An index of factorial simplicity. Psychometrika 1974, 39, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis, 7th ed.; Pearson Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jöreskog, K.G.; Sörbom, D. LISREL 7: A Guide to the Program and Applications; SPSS Inc.: Chicago, IL, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Browne, M.W.; Cudeck, R. Alternative ways of assessing model fit. In Testing Structural Equation Models; Bollen, K.A., Long, J.S., Eds.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1993; pp. 136–162. [Google Scholar]

- Bollen, K.A. Structural Equations with Latent Variables; Wiley-Interscience: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Han, Z.; Fei, K. Bootstrap based multiple mediation analysis method. Stat. Decis. Mak. 2016, 75–78. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).