Abstract

This study aims to investigate a chronological review of the term museum, defined by the International Council of Museums (“ICOM”) and Korean laws, and explore how the museum definitions have been revised historically. Then, it argues how the museum architecture has been spatially changed and explores whether the revised social roles and ethical responsibilities would impact the restructuring of the spatial changes. To this end, it scrutinized new ideas, significant issues, orders of words, and implicit intentions of the museum definitions over time. It analyzed the data of spatial change projects, which were collected through web crawling of the Korean National e-Procurement System. Then, the spatial changes were categorized regarding functions and characteristics. Through an in-depth investigation of a literature review and case studies, the findings suggest that museums had been understood as a place for collecting, exhibiting, and enjoying materials. However, they have been required to play diverse roles, such as collecting, conserving, exhibiting, researching, and communicating heritage for education, reflection, and sharing knowledge over time. However, the issue of cultural enjoyment has come into focus in Korean laws after 2007, and, as a result, spatial changes (e.g., creating immersive experience center, renovating exhibition spaces, and improving convenience spaces) have taken place exclusively in national museums. Thus, it is clear that national museums are aware of the need to actively think about their role with regard to the public and how architecture corresponds to this.

1. Introduction

1.1. Background and Purpose of the Study

As of 2023, the National Museum of Korea operates fourteen regional national museums, marking an expansion of its role as a regional cultural facility. To this end, it has been transforming its spaces in various ways since its opening. This should be understood in terms of increased operational efficiency, improvements to the exhibition environment, and the demand for diverse cultural experiences such as education, enjoyment, and knowledge sharing. In other words, the typically defined museum roles have shifted from storing and exhibiting artifacts within spatial layouts to strengthening the ties between museums and local communities [1,2,3]. These changes are clearly described by the International Council of Museums (ICOM) and Korea’s Museum and Art Gallery Promotion Act, emphasizing the importance of interpreting collections, fostering local community participation, and providing opportunities for education, enjoyment, and reflection for visitors. As a result, they have led to inevitable spatial changes at the National Museum of Korea, along with a policy shift. To highlight some examples of these changes, annex buildings have been added to address educational needs, architectural extensions have been made to solve the problem of over-crowded storage spaces, a part of the spatial layout has been transformed to improve environmental amenities, and advanced exhibition techniques have been used to create contemporary interpretations [4].

Of course, many studies have been conducted in order to identify in what way museums have been developed. For example, Foley and McPherson (2000) mentioned that museums are shifting from an education facility towards an accommodation of leisure markets because exhibitions attract touristic attention and create particular lifestyles associated with touristic behavior [5]. Kim (2010) goes further to suggest that the social and cultural demands for education and leisure play an active role in reconstructing spatial layouts [6].

Brown and Mairesse (2018) argue that today, museums should focus on the social role rather than the value of the collections, and they consider it essential for them to become a “complex hybrid” in order to encompass different points of view, to respect the “commonalities within our differences”, and to reflect many issues “facing the human race beyond its boundaries” [7] (p. 536). In addition, Mairesse (2019) investigated how the term museums has been discussed historically, which aspects would not be reflected within the definitions, and in what way museums have been understood across the world. He then points out that the values of the museum are partially linked to their collections, but mostly to ethical concerns such as authenticity, independence, or truthfulness, since these considerations make the museum work [8]. Babić (2025) presents practical examples of aspects to consider in museum operations in response to recent conceptual changes and role expansions in museums, as well as socio-cultural shifts. This study offers an international and multicultural perspective on the significance of operating and managing museums considering recent changes [9]. Therefore, it can be said that the original conception of the museum has become a cultural hybrid, and it should remain a place of reflecting social, ethical, cultural, and educational issues.

Compared with those studies that are focused on looking into the meanings and values of the term museums, others have paid attention to exploring how the spatial layouts have morphologically changed. For example, Lee and Choi (2008) found out that although major spaces have been envisaged along with their entry point, in order to increase spectator convenience, it is hard for visitors to comprehend the entire spatial structure. This is because museums’ roles are not limited to the exhibiting purpose but expand to serve as educational institutions and cultural infrastructure [10]. Regarding the major spaces, Park et al. (2005) also evaluate how successful the morphological transition of the British Museum and Tate Britain would be, and they conclude that the expansions (e.g., re-structuring the rotunda, adding a courtyard, planning a major space, and zoning in accordance with different functions) have been thought of as a good example of addressing corresponding social and educational demands [11]. Zhao, Xiaolong, and Lee (2021) also clarify four different types of expansions in museum architecture: horizontal expansion, vertical expansion, hybrid expansion, and revitalization. However, one of the reasons why such expansions have been carried out in museum architecture is the fact that experiential space has become important [12]. This means that museums are considered one of the most significant educational institutions, and this is why museum architecture develops spatial extensions.

Regarding museums’ spatial changes, the space syntax community scrutinized how spatial morphology would correspond to the museum’s narratives or intentions, in what way the building layout would be interrelated to its display function, and to what degree the morphological characteristics would be transformed over time. Based on those theoretical questions, Lee (2019) analyzed the narratives of the Natural History Museum in London, which are strongly related to spatial compositions, knowledge-transferring methods, exhibition techniques, and circulation patterns. In particular, he reveals that the spatial layout has been modified as old narratives have been replaced with new ones [13]. Psarra and Grajewski questioned how visitors comprehend museum buildings through their walking sequence, and they revealed that experiencing museum buildings involves the levels of understanding the architectural sequence and the conceptual structure as well [14]. Considering the idea of understanding, Brawne stressed the importance of intelligibility, meaning the clarity of the order of the spatial layout, because spatial experiences in museum architecture tend to be strongly determined by viewing images in sequence [15].

Seo and Lee (2009) suggest that the national museums in South Korea can be categorized into three generations regarding their main conceptions and roles: the first generation of museums, from 1971 to 1985, was designed for exclusively collecting, exhibiting, and managing artifacts; the second generation was understood as where museums were seen as social institutions, meaning that a focus on their educational role has played a significant part in transforming their spatial layout until 1995; and the third generation has turned to focus on the issue of cultural experience, bringing us to the present day [16].

Meanwhile, van Aalst and Boogaarts (2002) examine the ways in which the two museum areas in Amsterdam and Berlin have been developed over time and argue that museums have evolved from “buildings devoted primarily to educational and cultural presentations” to “public spaces where the visitor reigns” [17]. With the increase in competition and a rise in the number of museums, they are spatially concentrated in an area because a museum cluster enhances the visibility of individual museums and effectively positions the clusters in the tourism market. Another reason for why museums are clustered is that the role of museums has grown into them being seen as institutions “expected to engage with multifaceted societal issues in exchange for their municipal, state, and government grants” [18] and, as a result, they focus on boosting visitor numbers and securing financial support for exhibitions, programs, and educational activities. Museums invest in working with external entrepreneurs, developing temporary exhibitions, producing educational programs, and expanding gift shops due to increased financial concerns. As one of the effective means of securing and propelling visitors’ attention, museums, as Pilegaard points out, should take a step toward a material museum space. This means that museum architecture needs to be in active correspondence with exhibition design because this integrational approach enables the capture of immersive museum experiences, highlights multisensory perception, and emphasizes the materiality of objects [19].

From these studies, it is quite clear that museums are strongly related to narratives, collections, preservations, exhibitions, education, and leisure. Also, it is assured that they are associated with social, ethical, cultural, and educational issues, and they focus on actively responding to the contemporary markets. This is the reason that the term museum has been restructured and developed throughout history. Therefore, these conceptions form an understanding of museum architecture and the socially agreed roles and responsibilities that impact the structuring and characterization of spatial layouts.

However, those studies hardly answer the theoretical questions of how the term museum has been defined so far; in what way the definition of the museum has been revised over time; why museum’s conceptions need to be revised; and, most importantly, how these definitions affect the museum architecture. Therefore, this study aims to investigate a chronological review of the term museum proposed by ICOM and Korean laws and explore how museum definitions have been changed globally and locally. Based on these theoretical foundations, it argues how the museum architecture in South Korea has been spatially changed and explores whether the revised social roles and ethical responsibilities would impact the restructuring of the spatial changes or not.

Although this study concentrates on reviewing the definitions and spatial changes in a chronological way, it sheds light on a theoretical perspective of museum architecture and it provides a comprehensive framework for how museums may develop in the future. Also, we expect that this study will help us to better understand how museums work, and in what way museums change spatially.

It would be difficult to draw a conclusion from the examination of the national museums within one country, but this study can be considered as one piece of valuable literature in museum studies that can be used to build an understanding museums in other countries.

1.2. Scope of the Study

This study examines the transformation of museums’ social roles over time in response to the needs of each era and comprehensively analyzes changes in space in relation to the functions that have influenced these changes. Therefore, the scope of this study is divided into two key areas: changes in the museum’s role and changes in its operations and facilities.

The changing roles of museums are analyzed by comparing the evolution of key concepts proposed by the ICOM and Korean laws, including the Social Education Act: The First Definition of Museums, Museum Act, and Museum and Art Gallery Support Act. This comparison aims to clarify how the definition of “museum” and its social purposes have evolved over time. Specifically, the study compares the processes of change in the ICOM and Korean laws to explore the relationship between the two.

Furthermore, changes in operations and facilities are analyzed to determine how the changing role of museums over time is reflected in their practices and facilities.

To identify these changes in the context of the National Museum of Korea, we will examine literature published by the museum itself, the Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism, and the National Regional Museums, including annual reports, mid- to long-term development plans, and master plans for establishment. Furthermore, we will list the operational and facility plans in chronological order to identify trends and directions. Relevant literature was gathered from sources such as the National Library of Korea, Library of the National Museum of Korea, National Archives of Korea, policy research management system of Korea, and other sources.

Facilities are classified into project types, including new constructions (“NEW”), building annex construction (“ANX”), making extension (“EXT”), changing spatial layout (“SPL”), environmental renovation (“ENV”), and exhibition renewal (“EXH”). Data on these projects, ordered by year, are collected and analyzed using the government’s e-procurement system to confirm actual changes to the facilities. By analyzing and visualizing changes in functional areas and spaces over time along with their characteristics, changes in the role of museums and the corresponding changes in space are identified. Furthermore, it highlights the quantitative changes in space and the introduction of new functions, enabling the identification of key trends.

The temporal scope of this study was limited to the data collected from May 1995 to June 2023, which is the earliest available data from the National e-Procurement System, and only collected data from clients that are the National Museum of Korea. The research focused on projects involving the building annex construction (“ANX”), making extensions (“EXT”), and changing spatial layout (“SPL”), all of which result in actual changes to space. New constructions (“NEW”, new construction and relocation) involving the complete transformation of museum spaces, were excluded from the study, as they are not considered changes to existing facilities.

2. Research Methodology

2.1. Overview

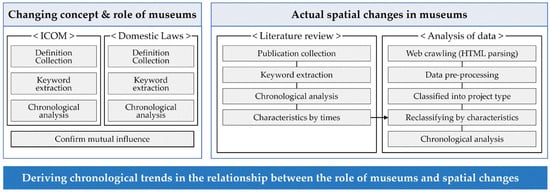

This study aims to identify the relationship between the expansion of museums’ role and trends in spatial changes through analysis. The characteristics of the collected literature and data appropriately combined quantitative and qualitative research methodologies which continuously inform each other: (ⅰ) to clarify the changing concept and expanding role of museums, keywords are selected from the definitions of museums in ICOM and South Korean laws by year, and trends in the change are derived; (ⅱ) to identify actual spatial changes in museums, the changes in facilities and operational plans published by the National Museum of Korea were chronologically examined and trends in museum spatial changes over time were identified based on quantitative trends in procured projects. The detailed composition can be found in Figure 1 and the description below.

Figure 1.

Research methodology.

2.2. Analysis of Museum Definitions

The role of museum’s is analyzed chronologically based on qualitative research methodologies, focusing on changes in the definition of museums by ICOM and South Korean laws, including the Social Education Act: The First Definition of Museums, Museum Act, and Museum and Art Gallery Support Act.

Keyword changes are extracted from the Museum Definition for each year. Based on the extracted keywords, the conceptual changes in museums are identified. Each concept is analyzed from the perspectives of collection, operation, responsibility and role, and target to examine changes over time. The overall conceptual changes and expansion of museums’ roles are then confirmed.

The similarities in the trends of changes at the national (South Korea) and international (ICOM) levels are identified to clarify the influence between them.

2.3. Literature Review

Literature related to changes in the facilities and operations of the museum, published by the museum itself, the Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism, and the National Museum of Korea, including annual reports, mid- to long-term development plans, and master plans for establishment, are systematically collected from a selected database: Ministry of the Interior and Safety PRISM, National Library of Korea, National Museum of Korea Library.

The project characteristics outlined in the publications were understood based on their purpose. Keywords were selected from the planning guidelines and operational program plans for each functional facility, and detailed information related to the project was extracted.

By categorizing these into facilities and operations and analyzing them chronologically, this study confirmed how the expansion of museum roles, as defined in the museum definition, is being applied to the National Museum of Korea.

2.4. Analysis of the Number of Spatial Change Projects

Bidding data were collected through web crawling of the National e-Procurement System, a government electronic procurement system in South Korea, targeting bids that specified the National Museum of Korea or national regional museums as customers. Data were collected from May 1999, when the first museum project was confirmed to have started bidding through the National Marketplace, to June 2023. Museum projects that involve spatial changes are characterized by their multi-layered nature, spanning from planning studies to construction. Therefore, this study focused on a single representative project, such as an architectural project, rather than multiple projects.

The methodology for collecting detailed data involved structural analysis of the URL addresses of the bid information on the National e-Procurement System’s website. This analysis confirmed that each bid information page is structured based on the date and customer information. This process was automated using R’s httr package and for loops. The XML package collected XPaths from each page (parsing HTML content). The collected data were then processed into a data frame using the dplyr package and Microsoft Excel and pre-processed into a format suitable for research.

The data are classified into project types, including new construction (“NEW”), building annex construction (“ANX”), making extension (“EXT”), changing spatial layout (“SPL”), environmental renovation (“ENV”), and exhibition renewal (“EXH”). The research focused on projects involving the building annex construction (“ANX”), making extensions (“EXT”), and changing spatial layout (“SPL”), all of which result in actual changes to space. New constructions (“NEW”, new construction and relocation), involving the complete transformation of museum spaces, were excluded from the study, as they are not considered changes to existing facilities.

Each project was then reclassified into one of four types based on the characteristics of changes in the role of museums and spatial changes over time, as derived from previous literature reviews: storage and exhibition functions, educational functions, convenience functions, complex cultural space. By analyzing and visualizing changes in functional areas and spaces over time along with their characteristics, changes in the role of museums and the corresponding changes in space are identified. Furthermore, it highlights the quantitative changes in space and the introduction of new functions, enabling the identification of key trends.

3. Theoretical Review

3.1. Expansion and Specialization of the National Museum of Korea

The National Museum of Korea traces its origins to the Joseon Imperial Museum, established in November 1901. Following Korea’s liberation, the National Museum was established by taking over the Joseon Government-General Museum in Gyeongbokgung Palace, along with two branch museums and three museums previously owned by influential local landowners.

From that point onward, the National Museum of Korea expanded by introducing local museums centered on the historic capital such as Gyeongju, Gongju, and Buyeo. In June 1990, the Ministry of Culture’s 10-Year Plan for Cultural Development Report proposed expanding the National Museum of Korea and local museums, increasing their number while ensuring regional equity (Figure 2) [20].

Figure 2.

Overview of the National Museum of Korea.

Previously, the National Museum covered the history of the Korean Peninsula, from prehistoric times to the Joseon Dynasty. That was presented as a continuous narrative, resulting in minimal differences in the content across individual museums.

Yang (2001) published a “Study on the Mid-and Long-Term Development Plan for National Regional Museums” in 2001. This study advocated for existing national and regional museums to develop unique and individual identities to strengthen their role as community-based cultural facilities. Consequently, this approach laid the foundation for the development of current regional-based content for the national regional museum [21,22].

The exhibitions of National Regional Museums were reorganized and remodeled according to this plan until 2008. Drawing on the “Study on the Creation of a Museum Complex” published by the Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism and the National Museum of Korea, the projects “Mid- to Long-Term Promotion Plan for Specialization” and the “National Museum Brand Project” were carried out in 2016, 2018, and 2023, respectively. These efforts have played a key role in shaping the museum into its current form.

3.2. Classification of the Museum Spaces

The literature on the architecture of major museums presents few criteria for museum spaces, where most are understood on the level of security, facilities, and functions.

First, in Japan, the analysis of museums proposed by Shigenobu Hanzawa in Museum Architecture in 1991 groups their parts into introduction area, exhibition area, storage area, research–study–information area, education-dissemination area, and management-common area [23]. In addition, the “Art Museum: A Collection of Examples of Architectural Design Data”, translated by the Architectural Data Research Association in the same year, divided museum regions into public areas (introduction, exhibition, education, and dissemination) and private areas (storage, research, and management) [24].

In the West, the Four-Zone Diagram proposed by Barry Load in 1992 in The Manual of Museum Planning is used; in this scheme, the four zones are classified by the degree of public access (visitor access) and collections. The access of the public (visitors) affects the level of the finish (environment), and the nature of the collections affects the level of security and the facilities [25]. In 1993, Joan Darragh and James S. Snyder described a division between public areas (free spaces and paid spaces) and non-public areas (art-related and non-art-related spaces) in Museum Design; these are divided in relation to their accessibility to the public, whether admission is charged, and their access to collections [26].

In Korea, the classification by functional area is the most commonly used, and most classification criteria are based on zones and areas in the Study on the Master Plan of the National Museum of Korea, published in 1995. This document was influenced by Barry Load’s classification criteria, which categorize public, functional, and collection-related spaces. In particular, functional classification groups areas into seven categories: visitor convenience areas, exhibition areas, education areas, storage areas, research and management areas, maintenance areas, and additional facilities [27].

Recently, the National Museums of Korea have begun to use a standardized area classification in publishing the Museum Annals. Here, there are six area categories: storage areas, exhibition areas, visitor convenience areas, office and research areas, other public areas, and additional facilities such as an official residence. However, no classification criteria have been presented for the specific rooms [28].

The policy literature indicates that the National Museum of Korea has strengthened its role as a community-based cultural facility by establishing and characterizing its contents and operations. This shows that its roles are changing and expanding. Nevertheless, security standards, access permissions, equipment, and functional characteristics are the main factors that determine spatial changes in museums. This leads to many restrictions on its use as an evaluation indicator for the comprehensive analysis of spatial changes in museums, which are increasingly required as they come to play more complex roles. Therefore, the primary purpose of this study is to examine how museums’ roles are changing and to systematically understand the actual spatial changes related to the results.

4. Examining the Changing Concept and Definition of Museums

4.1. The Changing Definition of Museums by the ICOM

The role of museums has expanded according to the ICOM’s definition of it, prompting an examination of the historical process of changing museums’ international definition.

The ICOM first defined the museum in 1946, and this definition has continued to evolve, with new definitions announced in 1974, 2007, and 2022. In 2019, discussions of alternative definitions took additional depth from new concepts of new museology and the demands of the times, such as Environmental, Social and Corporate Governance (ESG) and social inclusion. Research and discussion on the concept and role of museums are ongoing. Furthermore, many museums, related organizations, and researchers worldwide are participating directly in discussions to define the concept of a museum, making this a representative source of time-series data concerning conceptual changes in museums. The definition of a museum has evolved to encompass various elements over time:

- The first definition, proposed in 1946, defines a museum as a zoo or botanical garden, most of whose collections are open to the public. This definition is significant in that it stipulates that museums have a public nature. “The word ‘museum’ includes all collections, open to the public, of artistic, technical, scientific, historical or archeological material, including zoos and botanical gardens, but excluding libraries, except in so far as they maintain permanent exhibition rooms” (ICOM, 1946) [29].

- The 1974 definition held that a museum is a non-profit, permanent institution with a public nature, aiming to contribute to society and its development. This definition also included the museum’s value of a place of education and leisure, presenting its purpose as rooted in research, education, and enjoyment. A museum is defined as fulfilling its purpose by collecting, preserving, researching, communicating, and exhibiting material evidence related to humanity. “A museum is a non-profit making, permanent institution in the service of the society and its development, and open to the public, which acquires, conserves, researches, communicates, and exhibits, for purposes of study, education and enjoyment, material evidence of man and his environment” (ICOM, 1974) [29].

- In the ICOM’s 2007 definition, the target of museum collections was changed to be humanity, clarifying what museums should collect. At the same time, a conceptual expansion was seen that included material things, intangible values, and assets. Education was noted first in the statement of the museum’s purpose, confirming its higher priority. “A museum is a non-profit, permanent institution in the service of society and its development, open to the public, which acquires, conserves, researches, communicates and exhibits the tangible and intangible heritage of humanity and its environment for the purposes of education, study and enjoyment” (ICOM, 2007) [29].

- The alternative definition listed in 2019 has not yet been announced. However, the detailed content that is intended to be included in the 2022 definition can be identified. The concepts that are meaningful in their alternative definitions emphasize that the past should be preserved for future generations, that everyone should be guaranteed fair access to and use of museum assets, and that all museum activities should be performed for the benefit of humanity, including the museum’s local community. “Museums are democratizing, inclusive and polyphonic spaces for critical dialog about the past and the future. Acknowledging and addressing the conflicts and challenges of the present, they hold artifacts and specimens in trust for society, safeguard diverse memories for future generations and guarantee equal rights and equal access to heritage for all people. Museums are not for profit. They are participatory and transparent and work in active partnership with and for diverse communities to collect, preserve, research, interpret, exhibit, and enhance understandings of the world, aiming to contribute to human dignity and social justice, global equality and planetary wellbeing” (ICOM, 2019) [29].

- The 2022 definition places greater importance on interpretation (rather than on simple communication) as part of the role and function of museums and, therefore, it places more importance on the study of tangible and intangible assets than on the collection of simple heritage. It likewise states that the latest international trends in ESG, diversity, sustainability, and ethics form the main goals of museum operations and management. It provides various experiences, such as participation, education, enjoyment, reflection, and knowledge sharing in communities with activities at the museum. In addition, it centers the value of reasoning for cultural enjoyment and for the transmission of knowledge (information). “A museum is a not-for-profit, permanent institution serving society that researches, collects, conserves, interprets and exhibits tangible and intangible heritage. Open to the public, accessible and inclusive, museums foster diversity and sustainability. They operate and communicate ethically, professionally and with the participation of communities, offering varied experiences for education, enjoyment, reflection and knowledge sharing” (ICOM, 2022) [30].

The definitions for each year are summarised in Table 1. Clearly, the concept of a museum has changed from 1946 to 2022, moving from being centered on its simple role of collecting and exhibiting to including tangible and intangible assets related to humanity, emphasizing the provision of equal educational opportunities and community engagement, as well as foregrounding the value of the museum as a cultural hub. In the 2022 definition, the museum must emphasize the research, interpretation, and understanding of human assets, thereby pursuing diversity and sustainability, which are the common values of humanity in the museum.

Table 1.

Significant keyword change in museum definition in ICOM.

4.2. Changes in the Definition of Museums in South Korean Laws and Regulations

In South Korea, the Social Education Act (enacted in 1983 and subsequently revised to the Lifelong Education Act in 1990), Museum Act (1984), and Museum and Art Gallery Support Act (1991) were examined to determine how museums are defined within the country:

- The first definition of the role of museums in South Korea is found in the Social Education Act, defining museums as organized social education facilities for national lifelong education [31]. This definition differs from the primary functions and roles proposed by the ICOM, which recognizes museums as educational facilities primarily focused on social education.

- The Museum Act, enacted in 1984, aligns more closely with the original functions and roles of museums outlined in the ICOM’s 1974 proposal (with the exception of enjoyment) rather than the unidimensional focus of social education proposed in the Social Education Act. Therefore, this concept of museums has been firmly established since the enactment of the Museum Act in 1984. “The term ‘museum’ means a facility established to collect, preserve, and exhibit materials related to the human race, history, archeology, folklore, arts, natural science, and industries, and other things, to contribute to social education of the general public by examining and researching these materials. Among these facilities, local governments, corporation established by the Civil Act or the other corporations established by Presidential Decree, and registered under this Act” (Museum Act, 1984) [32].

- The Museum Act emphasized the need for museums to register at the national level to manage their establishment and operations. However, this law was later revised into the Museum and Art Gallery Support Act in 1991, which laid the policy foundation for relaxing regulations, such as lifting museums’ registration requirements and expanding the number of museums and art galleries across the country. As a result, the concept of the museum has also evolved. Notable changes include the term “natural science” in the Museum Act being subdivided to include “animals, plants, minerals, science, and technology” and the revision of “social education” to “development of culture and arts, academic development, and cultural education for the general public”, emphasizing the role of cultural facilities over those of social education. “The term ‘museum’ means a facility established to collect, preserve, exhibit, survey and research material related to the human race, history, archeology, folklore, arts, fauna and flora, minerals, science, technology, industries, etc., in order to contribute to developing culture, arts, and learning; enhancing the general public’s education of culture” (Museum and Art Gallery Support Act, 1991) [33].

- The concept and role of the museum evolved with the following four amendments. For example, the Museum and Art Gallery Support Act, which was amended in 1999, revised the primary role of the museum from contributing to the cultural education of the general public to promoting “cultural appreciation”. Additionally, the concept and role of material management began to emerge, prioritizing historical and archeological materials. “The term ‘museum’ means a facility established to collect, manage, preserve, survey, research and exhibit material related to history, archeology, human race, folklore, arts, fauna and flora, minerals, science, technology, industries, etc., in order to contribute to developing culture, arts, and learning; enhancing the general public’s enjoyment of culture” (Museum and Art Gallery Support Act, 1999) [34].

- In the 2007 amendment of the act, the idea of cultural appreciation was replaced with cultural enjoyment. This indicates that visitors passively received cultural benefits from the museum until 2007, but from then on, they can actively choose and enjoy cultural benefits. Therefore, it can be assumed that museum architecture needs to be altered in order to respond to the conception of enjoying museum culture. “The term ‘museum’ means a facility established to collect, manage, preserve, survey, research and exhibit material related to history, archeology, human race, folklore, arts, fauna and flora, minerals, science, technology, industries, etc., in order to contribute to developing culture, arts, and learning; enhancing the general public’s enjoyment of culture” (Museum and Art Gallery Support Act, 2007a) [35].

- Additional amendments in 2007 modified certain sections of the content and included the function of education. ”The term ‘museum’ means a facility established to collect, manage, preserve, survey, research, exhibit, and educate material related to history, archeology, human race, folklore, arts, fauna and flora, minerals, science, technology, industries, etc., in order to contribute to developing culture, arts, and learning; enhancing the general public’s enjoyment of culture” (Museum and Art Gallery Support Act, 2007b) [36].

- In the partial amendment of 2016, the phrase “lifelong education” was included, thereby expanding the role of community-based social education institutions. This resulted in a revival of the role of facilities for social education activities in the 2016 revision of the Lifelong Education Act, although the fundamental meaning of the amendment differed from that of the original text. “The term ‘museum’ means a facility established to collect, manage, preserve, survey, research, exhibit, and educate material related to history, archeology, human race, folklore, arts, fauna and flora, minerals, science, technology, industries, etc., in order to contribute to developing culture, arts, and learning; enhancing the general public’s enjoyment of culture; and facilitating lifelong education” (the Museum and Art Gallery Support Act, 2016) [37].

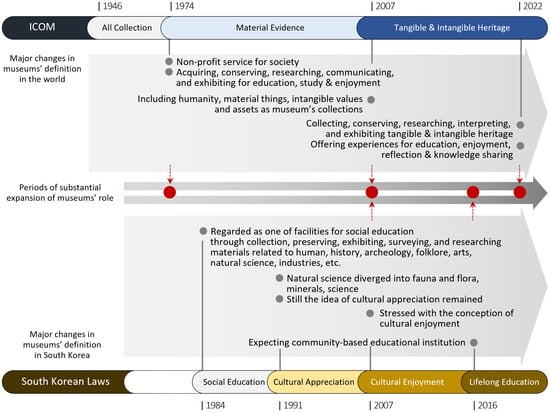

The definitions for each year are summarized in Table 2. From looking into the South Korean laws related to museums, it can be argued that the museum’s role is very similar to that outlined by the ICOM (Figure 3). However, a significant shift occurred with the concept of cultural enjoyment, which was emphasized by the ICOM in 1974. It should be noted that regarding these specifications, South Korean laws related to museums only began to incorporate this aspect in 2007, which was more than 30 years later than the ICOM. While Korean museums previously focused on conveying the meaning of their materials or cultural benefits to as many visitors as possible to promote cultural appreciation, they have taken the idea of enjoyment seriously since 2007. Consequently, Korean national museums are now perceived as cultural infrastructure, where visitors themselves can actively discover and enjoy cultural benefits relative to cultural enjoyment.

Table 2.

Significant keyword change in museum definition in laws of South Korea.

Figure 3.

Chronological change in the museum’s definition in International Council of Museums and South Korean Laws. (Red dots represent significant museums’ role expansion).

Simultaneously, they were initially only required to play a limited role as social education facilities. However, in 1991, they were required to function as cultural education facilities. By 2016, their role had expanded to serving as cultural infrastructure in local communities and promoting lifelong education.

4.3. Summary of Changes in the Concept and Definition of Museums

The definition of a museum as presented by a representative overseas institution related to museums and as described in South Korean laws and regulations were examined to determine the changes and expansion of museums’ roles. The concept of a museum in South Korea appears to align closely with the definition presented by the ICOM.

Despite this, there exists a slight difference between the definitions provided by the ICOM and those defined in South Korean laws. First, the concept of a museum, as defined by the ICOM, has evolved beyond its initial focus on collecting, preserving, and exhibiting materials, moving toward a more complex concept, including the preservation of the value of human heritage, understanding of regional characteristics, and provision of cultural activities promoting education, enjoyment, reflection, and knowledge sharing. Furthermore, it emphasizes the need for museums to adopt a role that promotes sustainability.

Conversely, South Korean laws have generally adopted the concept of a museum as outlined by the ICOM. However, these laws primarily emphasize the role of museums in relation to cultural producers and communicators, focusing on cultural appreciation, education, and enjoyment. It was not until 2007 that the relationship between museums and visitors was recognized as involving cultural production and consumption, marking an evolution in the perception of the concept of museums.

Examining the expansion of museums’ roles in the changing definition of museums has confirmed that museums are gradually being used as everyday spaces. This is an important consideration in projects to plan new museums or remodel existing ones. Such considerations should include domestic and international aspects, aiming to strengthen museums’ publicity.

5. Spatial Changes, as Shown in the Publications of the National Museum of Korea

5.1. Overview of Publications

Operation-related publications were examined to identify the plans that affect spatial changes. These publications focused on vision or mid- to long-term operations, development plans, and research reports published by the National Museum of Korea and National Regional Museums from 1985 to 2022. This study examined how the proposed plans were reflected in museum spaces. In particular, the study focused on the master plan research publications from 1985 to 2022. The primary considerations were based on changing or strengthening functions.

5.2. Major Changes in Operations-Related Publications

For the period of this study, namely from 1985 to 2022, eleven relevant operations-related documents published by the National Museums of Korea were identified (Table 3). Of these, the seven that contained the most important information were examined. For more details, please refer to Appendix A.1

Table 3.

Operation-related publications reviewed in this study.

A review of mid- to long-term operation and development plans is provided as follows. The plans in 2001 emphasized the establishment of a social education center to enhance regional specialization, as well as the role of social education. Plans in 2006 mentioned the expansion of the concept of cultural enjoyment to describe the importance of social and cultural art education. In 2012, plans were created to expand and reorganize the Children’s Museum. Later proposals focused on constructing building annexes for each museum to enhance its particular characteristics, representative contents, and educational functions, and many proposals focused on strengthening storage and conservation science.

5.3. Major Changes in Facility-Related Publications

From 1985 to 2022, a total of sixteen museum master plans were published that are relevant to this study (Table 4). This study was undertaken to examine changes in the role of museums and the corresponding changes in spaces. Moreover, publications related to the expansion of particular facilities, such as the renovation of the exhibition rooms of the National Museum of Korea Children’s Museum or plans to build new regional shared storage facilities, were excluded. This study thus examined twelve master plan research reports. For more details, please refer to Appendix A.2.

Table 4.

Facility-related publications reviewed in this study.

In the case of reports for the Chuncheon National Museum, published in 1994 and 1996, and the National Museum of Korea, published in 1995, the role of the museum as a social education facility emphasizing the creation of historical and cultural spaces and educational activities in the region was foregrounded, and its role as a visitor-friendly cultural space was made clear through the integration of sufficient rest areas and the expansion of the museum shop (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

The process of spatial changes at the National Museum of Korea: (a) the exhibition room of the Jinju National Museum (1984) [38] (p. 9); (b) the exhibition room of the National Museum of Korea Children’s Museum in 2010 in ref. [28] (p. 228); (c) immersive contents in the main hall of the Chuncheon National Museum (2023); (d) Silla Millennium Archive in the Gyeongju National Museum (2023).

The Jeonju National Museum published a case study in 2012, and the Iksan National Museum published another in 2015, which emphasized the use of public leisure facilities, the expansion of opportunities for cultural enjoyment, and the creation of complex cultural spaces offering various experiences and events as lifelong education facilities.

In a Museum Complex study published in 2016, which describes the future architectural direction of National Regional Museums, museums should be expanded as regional hub facilities for the enrichment of regional culture with the introduction of open spaces, expansion of contents, and improvement of cultural services.

From this, the case of the Chungju National Museum, published in 2020, and the basic plans of the Jinju National Museum and the Buyeo National Museum, published in 2021, describe Chungju/Jungwon culture, the connections of these institutions with the Jinju regional community, and future directions for the establishment of a specialized educational facility centered on the Baekje culture in Buyeo. They also call on museums, as content producers, to serve as cultural complexes that can satisfy the various needs of visitors.

5.4. Summary of Review of the National Museum of Korea’s Publication

From the review of the publications regarding museum operations and facilities, it was confirmed that the concepts of education and cultural enjoyment emphasized and expanded across all aspects of museum operations and facilities. Thereafter, shifts in museum operations and spaces took place in response to social requirements not explicitly mentioned in South Korean laws or international definitions, such as social contribution, community participation, and contribution to the value of reason.

This indicates that museums initiated changes in their operations and facilities before responding to domestic and international definitions. In other words, although the cases examined in this study are limited to a few museums in South Korea, the changes observed in these museums can be understood as leading international trends. Furthermore, similar changes can be predicted to occur in national museums of comparable status in other countries.

These changes are influencing the definition of museums and impacting their transformation worldwide. The cases examined in this study and those of national museums can be evaluated as valuable reference materials for constructing new museums or transforming existing ones.

6. Analysis of Spatial Change-Related Projects

6.1. Data Collection and Analysis Regarding Spatial Change-In Related Projects

Spatial changes were examined using the bidding information related to the National Museum of Korea and National Regional Museums on the National e-Procurement System to establish whether actual changes in space were made based on the findings of the mid- to long-term operations and development plans as well as the master plan study. The database of bidding information was gathered with R using web crawling techniques. It included the main tasks, bid announcement numbers, re-bids, announcement names, demand agencies, opening times, number of participants, winning bidders, price, price rate, notes, and web links for projects from May 1995 to June 2023. The same project frequently failed, so the decision to rebid was also considered.

The completed database included all bidding information on the National Museum of Korea as the demand institution, and Microsoft Excel was used for preprocessing data into a uniform format. A single spatial change manifests as a multi-layered project from planning to construction and operation based on the researcher’s judgment and representative projects were identified to prevent the double-counting of a single spatial change.

Furthermore, the project types were classified into new construction (“NEW”), building annex construction (“ANX”), making extension (“EXT”), changing spatial layout (“SPL”), environmental renovation (“ENV”), and exhibition renewal (“EXH”) by checking detailed announcements and the attached materials, such as guidelines, task instructions, and breakdowns. Here, the NEW refers to the construction of a museum that did not exist previously or the relocation of an existing museum to a different location. ANX refers to the construction of an annex building on museum sites. Additionally, the combination of a new building with an existing one, while having a different name, was also considered an annex.

EXT is defined as the expansion of an existing building’s area by enlarging its space or utilizing a previously existing space that was not legally recognized for use. Spatial change, on the other hand, is defined as the reallocation or modification of functional areas (storage, exhibition, education, visitor convenience, office/research, other public use, etc.) without a corresponding change in the total gross floor area.

The ENV refers to the refurbishment of a building due to its deterioration. By contrast, exhibition renewal refers to changes made in the exhibition space without a corresponding change in the gross floor area or the area of the functional areas. This study focused on spatial changes; therefore, NEW, ENV, or EXH without a quantitative change in space was included in this study.

Due to separate bids for each stage, one project was divided into several projects, including design services, construction (including machinery), electrification, communication, firefighting, and storage facility installation. Thus, only construction projects were selected as target projects in this study.

6.2. Number of Projects by Type and Year

Table 5 presents the project status for ANX, EXT, and SPL that occurred at the National Museums of Korea in the study period. A total of one hundred and four projects were carried out over the course of twenty-nine years; categorizing them by type of project, there were thirty-two projects for the construction of building annexes, fourteen for extensions, and fifty-eight for changing spatial layouts.

Table 5.

Number of projects for building annex construction (“ANX”), making extension (“EXT”), and changing spatial layout (“SPL”) from 1995 to 2023.

By period, nine ANX projects were carried out from 2001 to 2005 (excluding the 1997 expansion of the exhibition and storage facilities at the Gyeongju National Museum) and sixteen ANX projects were carried out from 2015 to 2023. In particular, eight took place from 2020 to 2022.

Projects carried out from 2001 to 2005, including the construction of employee housing, outdoor restrooms, information centers at the main gate, and employee cafeterias, were performed separately. The largest number of projects during this period was the construction of social education centers, with four projects (Cheongju in 2002, Gwangju, Gimhae, and Daegu in 2004).

The construction of warehouses, outdoor restrooms, workplace daycare centers, convenience facilities and waiting rooms for security guards continued after 2007. This period’s representative projects include the construction of five multi-cultural centers, multi-cultural halls, or pottery cultural centers (Buyeo 2009, Chuncheon 2017, Jeju 2018, Naju and Gwangju 2022). In addition, one experiential learning room (Chuncheon 2013), two storage rooms (Gyeongju 2015, Gongju 2018), one children’s museum (Chuncheon 2020), one realistic content experience center (Jeju 2020), and one cultural heritage science center (Central 2023) were established. In addition, only one media wall was installed in other public spaces (Chuncheon 2020).

Thus, the types of representative projects can be related to the timing of the ANX. Before 2005, the Social Education Center was built (2003–2004), and after 2006, the Experience-oriented Complex Culture Center was built in a building annex (from 2009 to 2018). More recently, the Digital-Oriented Complex Culture Center and the Porcelain Culture Center have emerged as elements having a specific theme.

Examining the status of EXT projects by year, four cases have been seen of the expansion of the conservation room, including the storage room (Cheongju 2001, Buyeo 2004, Jinju 2011, Chuncheon 2020). Five exhibition halls were renovated and expanded (Gyeongju 2004, Gimhae 2005, Gwangju 2009, Cheongju 2010, Gongju 2018). Two education halls and children’s cultural centers were renovated (Gwangju 2017, Chuncheon 2018) and three other facilities, including restaurants and cafes, were constructed (Jeonju 2009, Gongju 2016, Daegu 2019).

Unlike the ANX, EXT projects are concentrated on educational facilities for children or on preservation and exhibition facilities for cultural assets. In addition, EXT projects are equally distributed regionally, and the lack of space for certain core functions of museums, such as storage, exhibition, and education, is being addressed through expansions.

Five cultural experience rooms or experiential learning spaces were constructed (including outdoor spaces) (Buyeo 2003, Chuncheon 2005, Jinju 2006, Gongju 2007, and Naju 2013). Five children’s museums and related playgrounds were constructed (National 2019, Naju and Iksan 2021, Central and Cheongju 2022). Eight immersive content experience centers (Central, Gwangju, Daegu, and Cheongju in 2019, Gimhae, Gongju, Chuncheon, and Buyeo in 2020) and four public space media walls (Central in 2008, Chuncheon, Gwangju, and Iksan in 2021) were built. Three multistory storage facilities were built (Chuncheon 2014, Naju 2017, Central 2019).

Seven projects related to facility renovation involving the SPL were carried out (Cheongju Conservation Science Lab 2005, Gyeongju Saebyeol Hall 2008, Buyeo Social Education Center 2010, Gyeongju Archaeological Museum 2012, Buyeo Museum 2013, Jeonju Main Building Lobby 2015, Iksan Social Education Center 2020).

In addition, twenty-six projects were carried out, including the construction of rest areas and relaxation spaces, the expansion of parking lots, the remodeling of information desks, the enhancement of facilities for people with disabilities, the renovation of cafes and museum shops, the installation of a promotion center, the renewal of lobbies, the remodeling of airlocks and connecting corridors, the installation of security inspection equipment, the construction of outdoor fountains or the demolition of outdoor facilities, the construction of auditorium performers’ waiting rooms, and the installation of broadcasting equipment.

Before 2013, projects to promote cultural experiences or learning centers were frequently seen among projects of SPL; since 2019, however, projects to construct immersive experience centers are more common. In addition, immersive content is not only experienced in a single space but also actively changes the museum environment through the installation of media walls in video cafes, public spaces, or children’s museums (as in the cases of the Chuncheon, Gwangju, and Iksan museums) to expand the digital technology-infused cultural and cultural experience within the museum.

6.3. Annual Project Status by Major Function Type

The number of projects for ANX, EXT, and SPL has been examined by year. Among ANX projects, the construction of social education centers including children’s museums and education spaces was frequent in the early 2000s. Since 2006, a complex cultural space (including educational experiences) with a specific theme has been constructed. EXT projects are particularly notable in preservation facilities for cultural assets and educational facilities for children. Regarding SPL projects, the focus was on creating an immersive experience center, renovating exhibition spaces, and improving visitor convenience facilities and spaces.

However, it is challenging to determine which facilities appear repeatedly or are concentrated in a certain period by project type. Thus, this section will examine the type of facility or space by year.

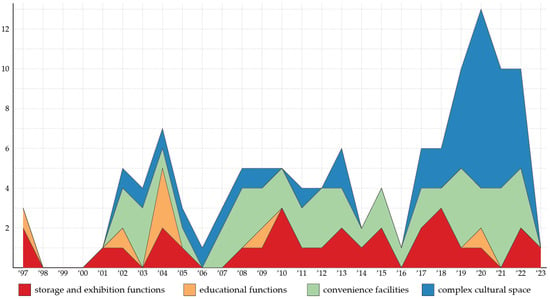

For this purpose, this analysis was used to classify the four categories to strengthen the storage and exhibition functions, educational functions, convenience facilities, and complex cultural spaces. Each project was assigned to one to four categories based on the purpose and scope of implementation and the occurrence frequency of each category was measured. Figure 5 organizes the collected data into four categories.

Figure 5.

Number of projects by category of major functional type from 1995 to 2023.

The strengthening of storage and exhibition functions can be understood as the enhancement of museums’ traditional role, as seen in 30 cases. In particular, an average of 1.12 projects were performed each year, meaning that the projects were implemented steadily across all periods. Thus, the museum’s traditional role of exhibition and storage is consistently being enhanced.

A total of seven projects were undertaken to enhance the educational function of museums, with the frequency of occurrences being infrequent, except in 2004, when three cases were concentrated. More specifically, social education centers were ANX projects (four cases) from 2002 to 2004. From 2005 to 2020, spaces related to educational functions were created through one EXT extension project and two SPL modifications. Educational functions are thus strengthened through changes and adjustments to interior spaces rather than the construction of new buildings.

There were forty-two cases related to the strengthening of convenience facilities, making it the largest category of changes. Excluding the period in 2006, when no such projects were recorded, an average of 1.56 projects were carried out from 2002 to 2022. Thirty cases specifically involved convenience facilities, while the remaining twelve cases were conducted together with other categories.

The strengthening of the cultural complex space occurred in forty-one cases. In particular, a social education center including a children’s museum and a cultural experience room was constructed from 2002 to 2004 (with five ANX and one SPL). From 2005 to 2017, projects were implemented to install cultural experience rooms in existing facilities (one EXT and six SPL). For this, projects were carried out to build a cultural complex space ANX in museums that did not have a social education facility (two cases) and were characterized by focusing on spaces for physical activities and experiences based on the five senses. From 2018 to 2022, this project featured the installation of spaces to experience immersive digital contents (six cases of ANX and thirteen SPL).

7. Analysis of the Expansion of the Role of Museums and Spatial Changes

Changes in the definition of a museum at the national (South Korean) and international levels were analyzed, and the direction of the changes taking place was confirmed through operational and facility-related plans proposed by the National Museum of Korea. As a result, it was found that museums could expand from their simple role of collecting, conserving, and exhibiting historical relics to that of being cultural and leisure facilities that provide enjoyment, reflection, and knowledge sharing through the collection, conservation, interpretation, exhibition, and education of human heritage and values. Moreover, the museum has been transformed into a local community hub and a facility that supports diversity and sustainability. It has also adapted to changing trends by implementing detailed action plans, strengthening its facilities, and continuing to transform itself.

This trend in changing spatial layouts has followed a consistent direction and appears to have preceded formal changes in the definition of museums at the international and South Korean level. These changes largely took place between 2005 and 2019, when change trends themselves altered, influencing the changes in the definition of museums in 2007 and 2022.

In particular, the project to strengthen the storage and exhibition functions throughout the study period indicated that certain changes to spatial layouts occur at a certain frequency and in part as an aspect of maintaining and supplementing the museum’s traditional role.

Before 2005, spatial changes related mainly to the strengthening of social education facilities the construction of social education centers, which could be understood as a result of the emphasized aspects of social education, as defined by the Social Education Act, the Museum Act, and cultural education, as defined by the Museum and Art Gallery Support Act. The Report on the 10-Year Plan for Cultural Development noted the consideration of equity between regions, and the Study on the Mid- to Long-term Development Plan for National Local Museums mentioned strengthening the role of museums as regional cultural centers; hence, these projects can be judged to be of the nature of facility enhancements.

Between 2005 and 2023, spatial changes were seen in the museum’s transformation into a cultural complex space, along with the enhancement of its convenience facilities. It can be understood as changing from simply providing content and building spaces with functions to focusing on the visitor experience in the museum space. This is the result of the emphasized aspect of cultural enjoyment in the international definition and South Korean laws, and it can be interpreted as a change in the direction of emphasizing experience rather than education. The same aspect can be observed in the plans related to the operations and facilities of the National Museum of Korea.

Different tendencies can also be seen in the same period, according to year. From 2005 to 2018, the number of convenient facilities such as rest, food and beverage, and cultural complex spaces including children’s museums and traditional experience spaces continued to grow. Since 2019, however, these spaces’ formats and keywords have shifted toward the digital, and the active use of immersive content has become apparent. This is an example of how the operation and function of a museum have changed in response to visitors’ needs along with the development of technology.

Furthermore, the changing interest in archives, such as the Silla Historical Document Archive (Silla Millennium Library) at the Gyeongju National Museum in 2021 and the National Museum of Korea in 2021 and 2022, could be identified. By reviewing the studies on the archive center, the future of the museum’s visitor experience and changing spatial layouts can be expected to be realized through the archive.

8. Conclusions

This study explored how museums have been understood by looking into the International Council of Museum and the Museum and Art Gallery Support Act in South Korea and focused explicitly on scrutinizing new ideas, significant issues, orders of words, and implicit intentions through a chronological review of the definitions. Based on these historical reviews, the study examined how museum architecture has been modified until now. In particular, it aimed to identify whether the museum’s roles suggested by the Korean government would be different from the ones outlined by the ICOM or not. By comparing them, it is interesting to note that they are quite similar to each other. In 2007, both of them aimed to acquire, conserve, research, communicate, and exhibit tangible and intangible heritage for education, study, and cultural enjoyment; from 2016, as community-based educational institutions, they both tried to offer diverse experiences and to share knowledge.

Korean national museums took a slightly disparate strategy until 2007, in that they had concentrated on promoting cultural appreciation; in other words, they were understood as cultural places for visitors to enjoy. Nevertheless, this strategy was replaced with the idea of facilitating enjoyment. This shift decisively led to the transformation of museum architecture, such as enhancing visitor convenience facilities (e.g., museum shop, cafeteria, resting area), enlarging educational spaces, and offering variant experiences (e.g., immersive digital contents, trailing archive centers, or workspaces). Since then, these architectural transformations (e.g., constructing annexes, making extensions, or changing spatial layouts) have been happening. Therefore, the shift from appreciation to enjoyment is an architecturally significant element in understanding Korean national museums.

This study also revealed that museums actively respond to cultural, educational, and curatorial demands before stipulating their definition. This means that architectural transformations and spatial changes took place first, and then the definition was updated. Therefore, it can be said that national museums are aware of actively thinking about what to do for the public and how the architecture corresponds to it.

Naturally, this study has limitations. Firstly, it only explored a theoretical relationship between the museums’ definitions and the projects of constructing annexes, making extensions, and changing spatial layouts. It is unclear how the museum architecture has been morphologically modified, so this should be examined in the future. Next, this study focused only on the cases of the national museum. This means that we need to explore diverse museums, such as private museums, specialty museums, and art galleries. By investigating different museum types, we can draw a clear picture of the museum architecture and anticipate which direction it will take in the future.

In this study, changes in museums’ functional spaces were analyzed chronologically based on various plans and data. The fact that this study does not include an analysis of actual changes in spatial structure can be recognized as one of its limitations. However, the methodology used in this study for deriving the patterns of spatial changes from the cases enables us to identify the globally consistent role extensions beyond trends of change. Also, it investigates architectural changes such as restructuring different functions, recomposing spatial structures, and improving museum architecture. These findings could be used as a cornerstone for future research works in museum studies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.-Y.H. and J.H.L.; methodology, J.-Y.H.; validation, J.H.L.; formal analysis, J.-Y.H. and J.H.L.; investigation, J.-Y.H.; resources, J.-Y.H.; data curation, J.-Y.H.; writing—original draft preparation, J.-Y.H.; writing—review and editing, J.-Y.H. and J.H.L.; visualization, J.-Y.H.; supervision, J.H.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ICOM | International Council of Museums |

| NEW | New construction |

| ANX | Building annex construction |

| EXT | Making extension |

| SPL | Changing spatial layout |

| EBV | Environmental renovation |

| EXH | Exhibition renewal |

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. Operation-Related Publications Reviewed in This Study

This study selected and analyzed seven reports published by the National Museum of Korea that contain the most important information related to its operations.

The mid- to long-term operations and development plan reports provide directions for the operations of and changes in the museum for the following five years (or another specified period), based on the year of publication. The reports provide an understanding of the goals differentiating the National Museums of Korea from traditional museums and present a vision showing how space should be changed. The main reports in this study can be characterized as follows:

- Published in 2001, the Study on the Mid- and Long-Term Development Plan of the National Museum of Korea suggested the establishment of a national heritage center, expanding advanced equipment and facilities and operating a research collection reading room to manage the museum’s collection. It also describes the importance of social education through the operation of the Children’s Museum [21].

- Published in 2001, the Study on the Mid- and Long-Term Development Plan of National Regional Museums proposes measures to specialize exhibitions, expand the role of social education through the construction of a social education center, and establish a regional traditional culture reference room to support research. It also describes the strengthening of conservation science capabilities through securing storage space according to different material and expanding conservation treatment equipment and facilities. This can be understood as moving in a clear direction including responding to local cultural enjoyment and increasing the value as a leisure space through strengthening the role of National Regional Museums [22].

- Published in 2006, the report National Museum Vision 2020: A Museum Where the Breath of History and the Power of Culture Come to Life called for the National Museum of Korea’s main role to be expanded beyond lifelong education to reach cultural enjoyment. Following that direction, the establishment of a museum education center for social and cultural education was proposed [39].

- Published in 2012, the report Study on the Mid- to Long-Term Development Plan of the National Museum of Korea proposed significant tasks be undertaken, such as expanding and renovating the Children’s Museum, expanding storage space, and building regional storage facilities to strengthen conservation capacity. It also noted the expansion of diverse, convenient facilities, such as museum shops, to improve visitor satisfaction [40].

- In 2017, the Gyeongju National Museum presented a detailed plan based on the 2012 mid- to long-term development plan. First, it noted the reflection of the nature of the historical sites and relics, as well as the use of storytelling techniques in the permanent exhibition. Furthermore, a new exhibition hall was declared necessary for the effective preservation and display of the Divine Bell of King Seongdeok (unified Shilla, 771) in the museum’s collection. In addition to relocating the Children’s Museum to increase efficiency, the plan to would expand research functions by establishing the Silla Studies Research Center, building a library and study space; the creation of an open archive using the existing exhibition Hall is also proposed. For the public space, the report suggests the need to expand convenient facilities over a long-term perspective and plan a specialized space to intensively cover the entire area by placing information and convenient facilities in the lobby. In particular, the report describes the need to build a connecting exhibition hall to connect the Special Exhibition Hall and the Silla Art Museum to improve viewing flow [41].

- Published in 2020, the Gimhae National Museum’s mid- to long-term development plan report presents the establishment and operation of the Gaya Heritage Storage Center and the Gaya Research Institute as key tasks and also proposes to enhance the efficiency of space and operations with a transfer of functions between buildings. The plan proposes the creation of an experience space, related to the public space, where people will want to spend time, through expanding or relocating convenient rest areas and transforming existing lobby space into an open rest area integrating information, cafes, and convenient facilities [42].

- Finally, published in 2020, The National Museum of Korea: A New Era, 2030 Strategy for Opening the Future presents the following as key strategic tasks: strengthening educational functions through the establishment of a separate children’s museum, selecting representative content and interpreting it in a future-oriented way, establishing a cultural heritage science center to construct a smart museum environment, and expanding the operations of the museum’s reading room. This further emphasizes the concept of cultural enjoyment and calls for the role of cultural infrastructure to be more closely integrated into our lives. In public spaces, the main task is to improve the environment and provide cultural inspiration, relaxation, and healing to visitors and residents as lifestyle infrastructure [43].

Appendix A.2. Facility-Related Publications Reviewed in This Study

This study selected and analyzed twelve reports published by the National Museum of Korea that contain the most relevant to this study, related to its facilities.

First, the study examined the goals, roles, functions, and key characteristics of the museums as described in the publications. Furthermore, the study investigated the areas of storage, exhibition, education, visitor convenience, and office/research, which can be defined as museums’ unique functions, and identified the changes that are being sought in these areas and how these changes differentiate the anticipated museums from existing ones. The detailed analysis results are as follows:

- Published in 1994, the Master Plan for Establishment of the Chuncheon National Museum aims to preserve local cultural and historical assets while fostering balanced development across the country. It also seeks to enhance historical and cultural spaces in the region by establishing educational and promotional facilities. Accordingly, it emphasizes that the museum should be developed into complexes with educational functions that promote learning through exhibitions and related activities or programs. The primary aim of land use is to design a layout that aligns with the terrain and cultural facilities based on rest. This approach is consistent with the current context, where the role of museums is expanding to include social education facilities [44].

- Published in 1995, The Master Plan for Relocation of the National Museum of Korea proposed the social education function as the primary function of museums. For this purpose, it suggests the introduction of a resting area, a museum environment designed as a cultural complex, and a museum shop as key components. In particular, museum shops and bookstores can offer public services and function as spaces for cultural enjoyment, providing reference materials and information rather than solely focusing on profits. This direction in the master plan can be seen as an effort to integrate museums into people’s everyday lives [45].

- Published in 1996, the Basic Exhibition Plan of the Chuncheon National Museum outlines a study on exhibition materials, objects, classification, content, and directions based on the planned architecture. This foregrounds the museum as a facility that plays a role in the social education of the region, suggesting that the museum include a rest area within the exhibition flow to provide convenience and relief from fatigue. It also proposes engaging in profit-making activities by utilizing the circular patio, installing a cafeteria, and specializing the museum shop. This suggests that the Chuncheon National Museum is not only a museum that collects, preserves, and exhibits but is also a visitor-friendly space, planned in accordance with collections, rather than a space that is adapted to the collections [46].

- In 2012, the Establishment of the Master Plan for the Renovation of the Jeonju National Museum mentioned the role of the museum as a place for leisure, a comprehensive cultural and artistic space, and an educational institution. Therefore, it emphasized the need for a shift in perception toward “developing programs for social contribution” and creating “a complex cultural space where various experiences and events can be held.” It presents the lobby as a complex space where visitors can have various experiences by building a rest area, a museum shop, and an archive space [47].

- Published in 2015, the Study on the Master Plan for the Establishment of the Iksan National Museum proposes “expanding opportunities for people to enjoy culture by overcoming existing limitations of exhibition halls and becoming a lifelong education facility and a complex cultural space, in line with the trends of modern museums” and “becoming a museum that provides specialized experiences for children (students).” This report proposed the renovation of the existing Miraksaji Temple Heritage Exhibition Hall to serve as a lifelong education and cultural complex, with a new main building focused on exhibitions. This direction aimed to implement programs aligned with the life cycle, reflecting the growing importance of lifelong education and leisure use of museums [48].

- Published in 2015, the Master Plan for the Establishment of Complex Cultural Building indicates the need for facility expansion, mentioning the justification for establishing a complex cultural center, including a children’s museum. This can be seen as an attempt to include and streamline new functional spaces, in line with various spatial issues that have arisen since the initial establishment, changes in visitor characteristics, expansion of the museum’s role, and changes in environment [49].

- Published in 2016, The Master Plan Study for Establishment of Museum Complex at National Regional Museums proposes a facility complex idea that suggests the combination of various types of cultural infrastructure facilities using the site, expanded exchanges with other museums through content expansion and enhanced operations. Detailed plans for pilot regional museums (Chuncheon, Daegu, Jeonju) were established to present the concept of a complex museum with different content, roles, and functions according to regional characteristics and needs [50].

- Published in 2020, the Study on the Master Plan for the Establishment of the Chungju National Museum examines the concepts of regionality, tourism, and cultural enjoyment, along with the topic of infectious diseases (among the most aspects of 2020). It proposes a flexible spatial plan that can accommodate changes in museum facilities and spaces, minimizing the crowding of visitors using connecting spaces, such as corridor spaces and small halls. This shows that changes are taking place in response to the conditions of the times [51].