Abstract

This paper presents the dynamic characteristics and seismic performance of the Chen Xiang Pavilion in Xi’an and the influence of the lower stylobate on the dynamic response of the upper wooden structure. An in situ dynamic test was conducted under ambient vibration to detect the natural frequencies and vibration modes of the structure. Three numerical models, including the upper wooden structure, the lower stylobate, and the whole structure (wooden structure and stylobate), were established. Dynamic characteristic and seismic response analyses were performed on the calculated models to investigate the influence of the lower stylobate on the dynamic response of the upper wooden structure. The simulation results indicated that the lower stylobate significantly affected the dynamic characteristics of the upper wooden structure above the third order. The seismic responses of the upper wooden structure were amplified because of the lower stylobate. Under different excitations, the displacement response of the whole structure was up to 1.99 times relative to the upper wooden structure, and the structural shear forces were increased by 15.3%. The dynamic amplification coefficient was magnified from 0.742~0.948 to 1.024~1.776. The Chen Xiang Pavilion has a good energy dissipation capacity, but the lower stylobate is unfavorable for its earthquake resistance.

1. Introduction

As a cultural carrier, ancient architecture has become a historical symbol in various urban regions after a thousand years of development and inheritance, representing an invaluable legacy of human civilization [1]. Among the ancient structures preserved, wooden structures are some of the primary structural forms, including timber palaces, temples, and pagodas, which account for more than 50%. In contrast to the structural forms in modern architecture consisting of integral casting, bolting, or welding, the beams and columns in traditional wooden structures are connected by wood-to-wood connections such as mortise–tenon joints and Dougong brackets, which have been widely discussed and studied by scholars at home and abroad because of their unique structural characteristics and superior seismic performance [2,3].

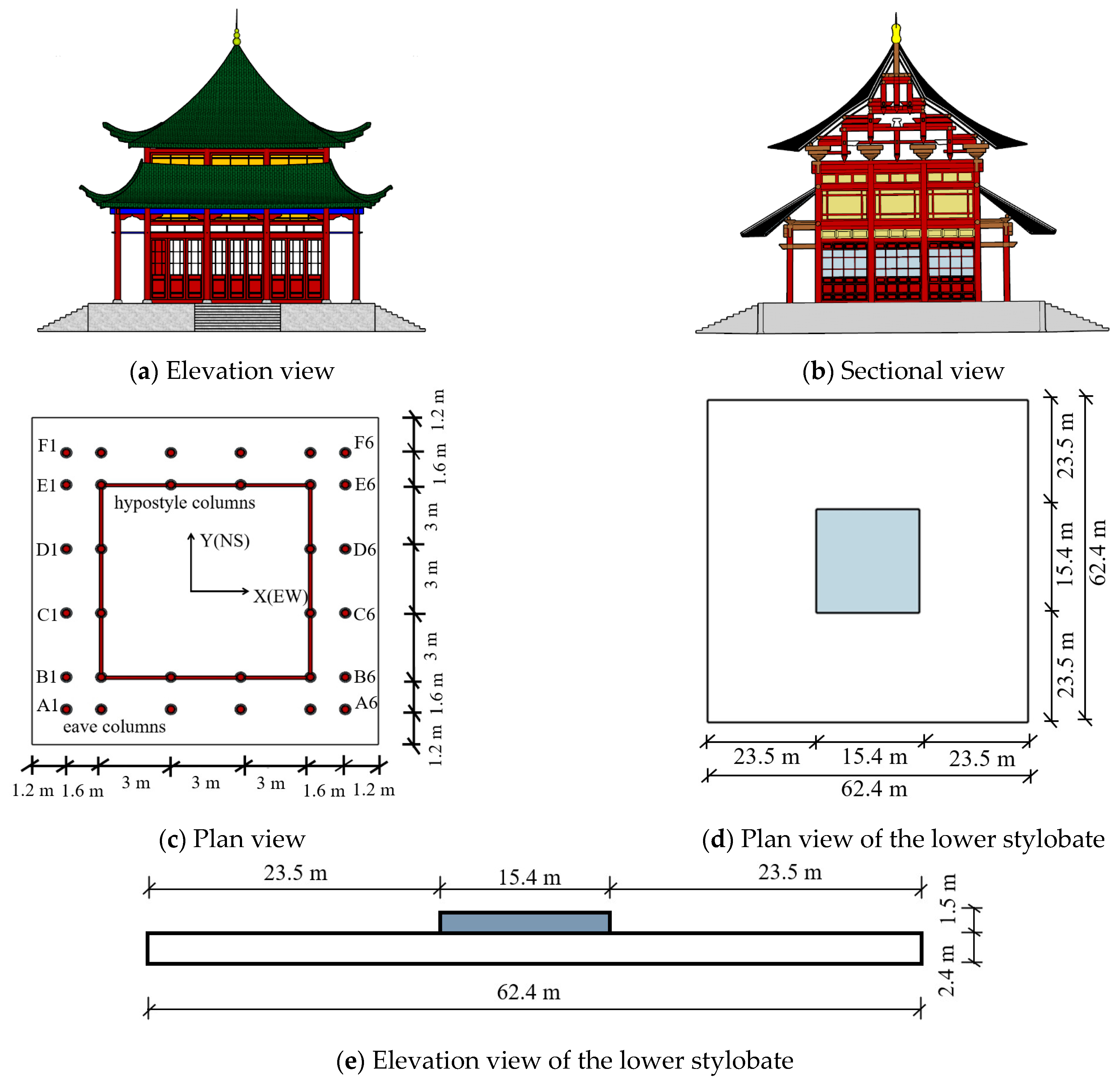

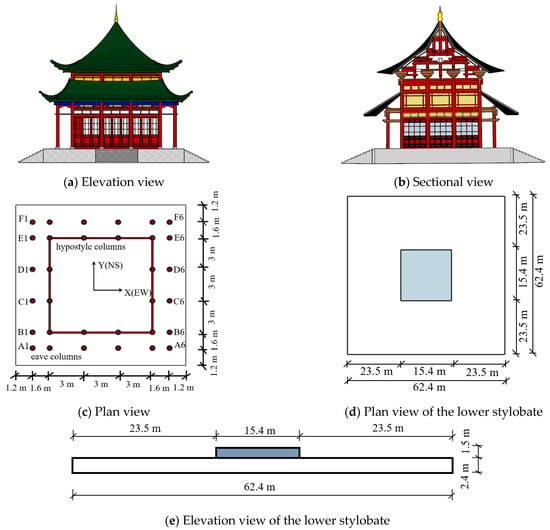

With the reduction in vandalism over the past few years, natural disasters have been the most important cause of damage to ancient wooden structures, such as earthquakes, typhoons, and floods, as well as other major factors like traffic [4]. As a result, it is crucial to examine the structural performance of ancient wooden structures, especially their dynamic characteristics, to provide a fundamental basis for their structural appraisal and strengthening. As a historical and cultural city, Xi’an is rich in ancient architecture. However, destructive earthquakes occur frequently in this region. The Chen Xiang Pavilion is one of the most iconic wooden structures in the Xi’an Xing Qing Palace, rebuilt in 1958 (Figure 1); it is composed of an upper wooden structure and a lower stylobate. The structural dimensions are shown in Figure 2. The upper wooden structure is symmetrical, including a column frame layer, beam frame layer, and roof, whose length, width, and height are 13 m,13 m, and 14.79 m, respectively. The eave columns are 4.4 m in height, and that of the hypostyle columns is 7.3 m (Figure 2a,b). The widths between each component are shown in Figure 2c. The specific sizes of the lower stylobate are shown in Figure 2d,e. Accordingly, dynamic characteristic and seismic response analyses of this complicated structure should be performed in order to protect it from natural disasters; this is indispensable for the maintenance and longevity of the Chen Xiang Pavilion.

Figure 1.

Photo of Chen Xiang Pavilion in Xi’an.

Figure 2.

Elevation, sectional, and plan views of Chen Xiang Pavilion.

In general, three methods, namely the shake-table test, in situ dynamic test, and finite element numerical simulation analysis, are adopted by researchers to study the dynamic characteristics and seismic responses of wooden structures. The shake-table test using full-scale or reduced-scale models is the most direct method used to study the structural seismic response, dynamic characteristics, and damage mechanism in the laboratory, so it has received favor among scholars [5,6,7,8]. However, compared with the former, owing to its convenience and reduced expense, the in situ dynamic test is chosen extensively as a vital detection method to identify the relevant dynamic characteristics of wooden structures [9,10,11,12,13]. In this method, natural pulsation and artificial excitation can be selected according to the test’s purpose. However, to achieve non-destructive testing, health monitoring studies are often based on natural pulsation excitation, aiming to detect useful dynamic features of ancient wooden structures. The weak vibration signals of the structure, caused by the random excitation of the external environment, are collected, and the actual dynamic characteristics are obtained through the corresponding parameter identification methods [14,15,16]. Furthermore, as for the method of finite element numerical simulation analysis, using the known material characteristics and component dimensions, numerical models are established for analysis with finite element software. This is also widely used to study the dynamic characteristics and seismic responses of ancient wooden structures [17,18,19]. In addition, some experts have measured the seismic responses and dynamic characteristics of ancient wooden structures through environmental excitation, and, based on the finite element analysis, specific repair plans addressing apparent defects and structural damage in the measured ancient timber building are put forward, which provide a reference for the protection of ancient buildings [20,21].

In recent years, the influence of the lower stylobate on the dynamic characteristics and seismic responses of wooden structures has become a research hotspot among scholars [22,23,24]. According to Yingzao Fashi, the traditional lower stylobate is composed of rammed earth with various heights and shapes. Research on the influence of different lower stylobates on the upper wooden structure is performed with different methods. Recent studies have shown that the dynamic characteristics of the upper wooden structure are changed due to the participation of the lower stylobate in the common vibration. Furthermore, the lower stylobate enlarges the seismic response of the upper wooden structure, which is not conducive to the seismic resistance of structures. Moreover, in the existing research on ancient buildings with lower stylobates, the upper wooden structures are mostly single-eave buildings, and there is relatively little research on double-eave ancient buildings. Therefore, the lower stylobate must also be considered in the model calculations [25,26]. However, the current research only focuses on the significant effects of the lower stylobate on the dynamic characteristics and seismic responses of the upper timber structure, and it fails to clarify the change rules of the peak displacement response, peak shear force, dynamic magnification factor, and other parameters of the upper timber structure when the lower stylobate exists. It is not possible to quantitatively reflect the energy dissipation capacity and vibration isolation performance of the structure.

In this work, the Chen Xiang Pavilion was chosen to study its overall dynamic characteristics and seismic response and analyze the impact of the lower stylobate on the upper wooden structure. For these purposes, an in situ dynamic test was conducted based on ambient vibration. Moreover, finite element models were established to perform dynamic characteristic and seismic response analyses. In this work, based on the finite element method, the natural frequencies, vibration modes, displacement response, acceleration response, inter-structural layer drift angle, and shear force of layers were compared and analyzed. The effect of the lower stylobate on the dynamic characteristics and seismic response was quantitatively analyzed. Additionally, the upper wooden structures were ancient eave buildings, and the lower stylobate was also considered in the model calculations. These research results will provide theoretical support for the seismic protection and repair of the structure.

2. In Situ Dynamic Test

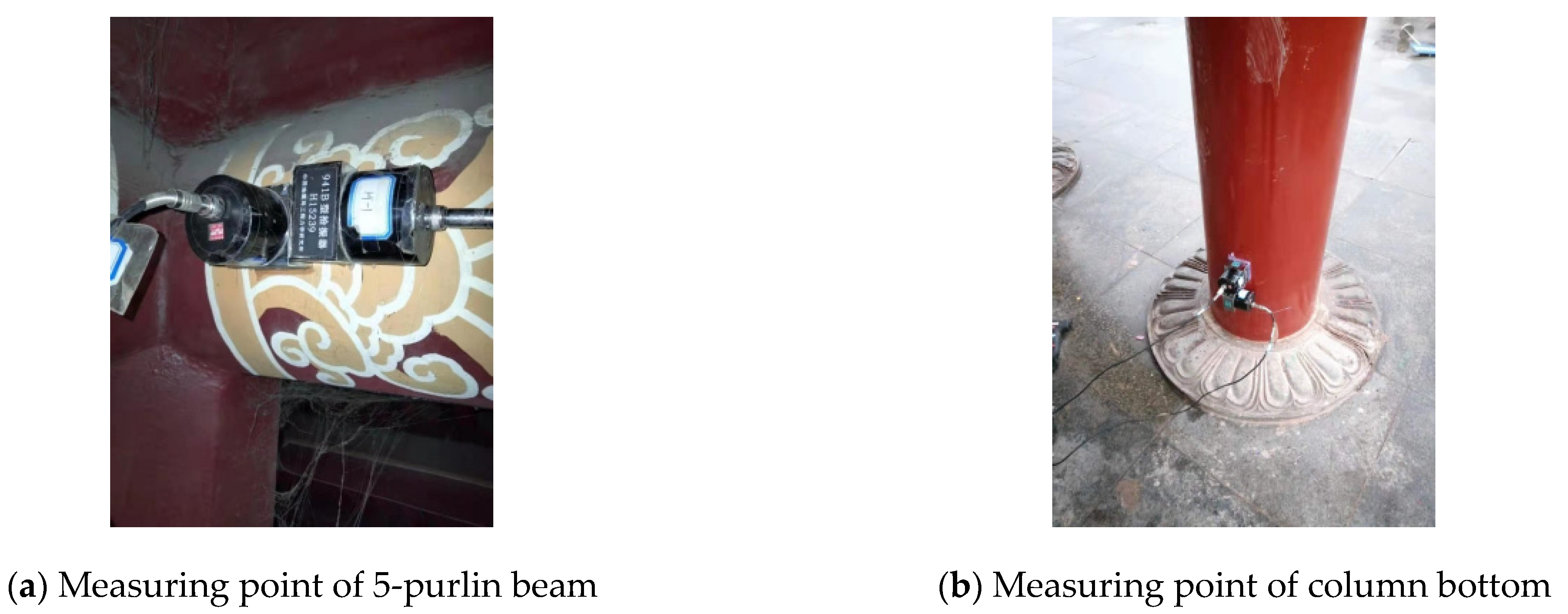

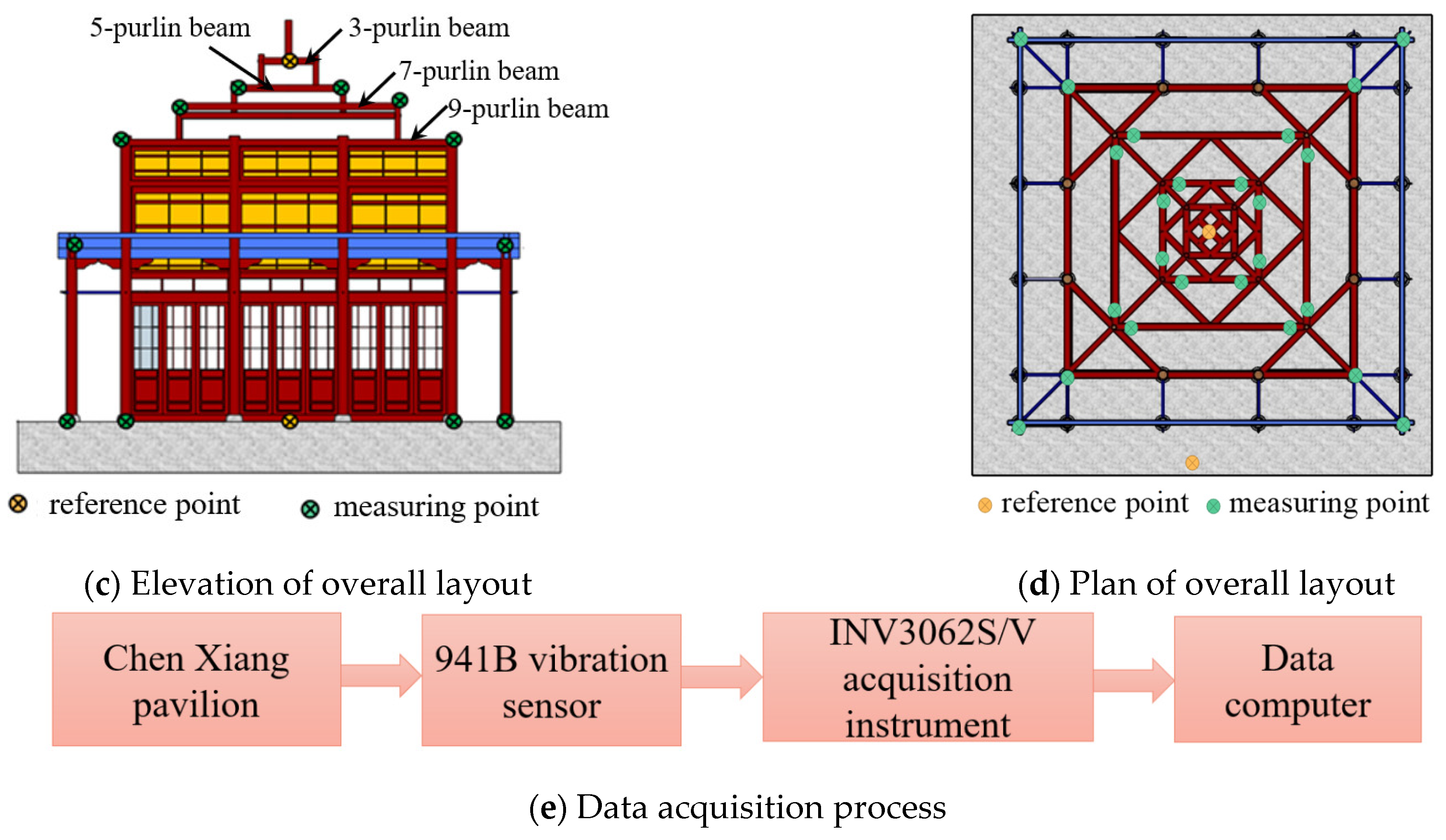

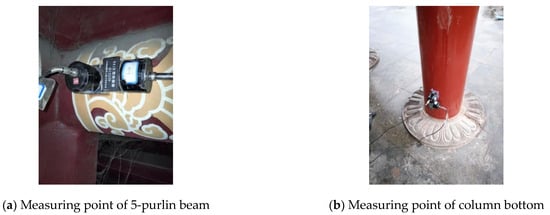

2.1. Layout of Measuring Points

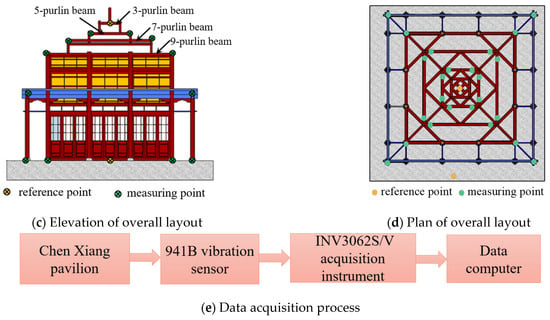

To obtain the dynamic characteristics and evaluate the seismic performance of the Chen Xiang Pavilion, the INV3062S/V network distributed acquisition instrument and the 941B ultra-low-frequency vibration sensor were used in the in situ dynamic test. The speed gear of the 941B vibration sensor was selected to collect vibration response signals based on ambient vibration when considering the size, quality, and material of the structure. According to the “Technical Code for Preventing Industrial Vibration of Ancient Buildings” (GB/T 50452-2008) [27], two horizontal vibration sensors were arranged at each measuring point to collect vibration response signals in the north–south direction (NS) and east–west direction (EW), respectively. Meanwhile, owing to the litter of the 941B vibration sensors, the test was conducted in batches, with the vibration sensors fixed as the reference point at the ground and three purlins. The vibration sensors were arranged at the foot and top of the corner columns. The layout of the measuring points is shown in Figure 3a. Both ends of the 5-purlin beam and the 9-purlin beam were chosen as the main measuring points due to the small height difference between the 7-purlin beam and the 9-purlin beam. The vibration sensor arrangement in the beam frame is shown in Figure 3b. The layouts of the measurement points for the overall structure are shown in Figure 3c,d. Through the INV3062S/V network distributed acquisition instrument, the data collected by the vibration sensor were transmitted to the data acquisition computer. The vibration sensor, data acquisition instrument, and computer were connected to receive signals, as shown in Figure 3e.

Figure 3.

Flow chart of data acquisition.

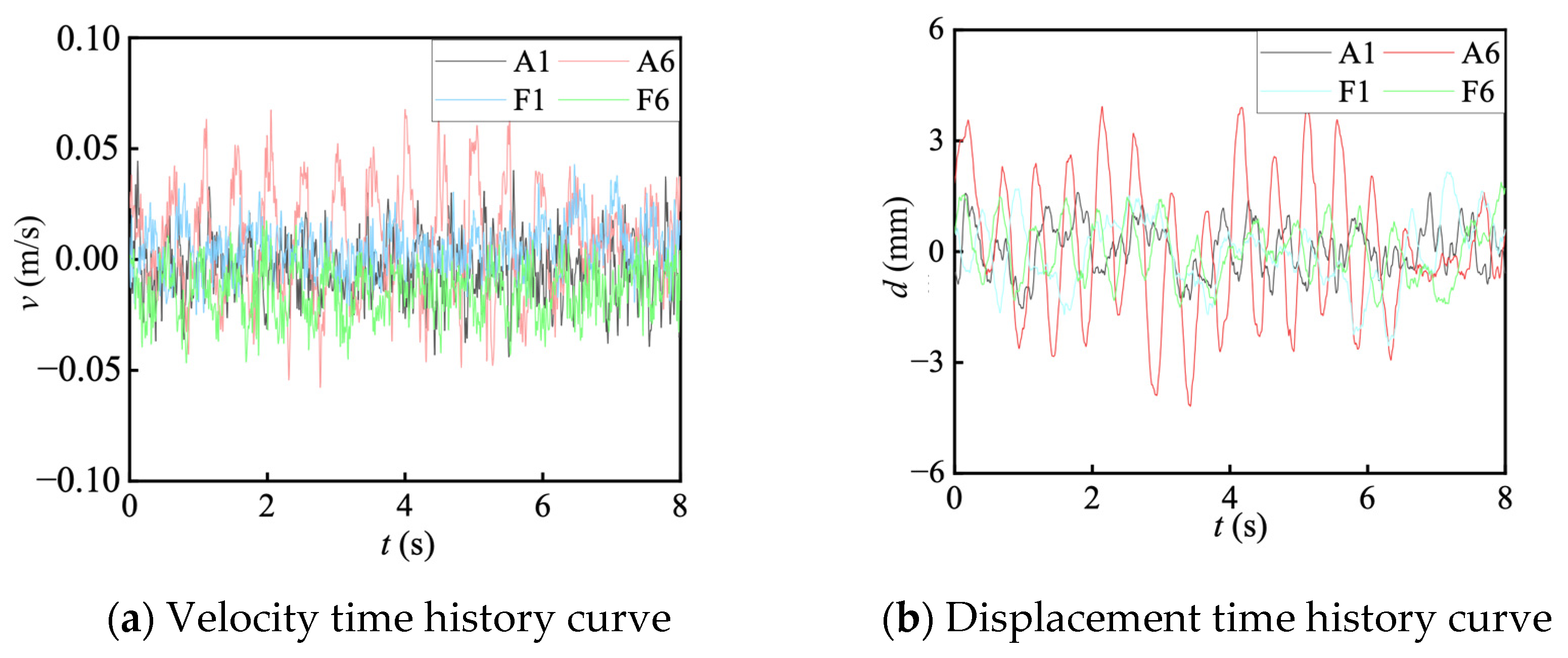

2.2. Data Acquisition

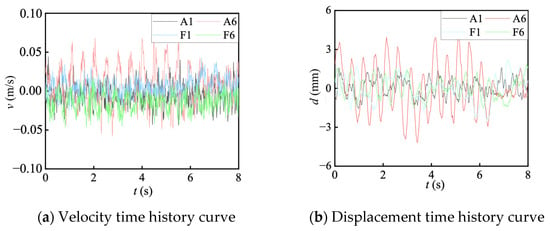

During the test, the sampling frequency and time were, respectively, set to 102.4 Hz and 200 s. The start mode was configured to be freely triggered. After the settings were completed, the sampling began when the waveform was stable. In Figure 4, Figure 4a is the signal waveform collected by the velocity sensor in the EW direction at the top of the eave columns, where v is the velocity at the top of the eave columns. The time history curve of the displacement d was obtained by integration, as shown in Figure 4b. A1, A6, F1, and F6 were corner columns, where the responses of the measuring points under the excitation were huge, as shown in Figure 2c.

Figure 4.

Time history response curve of eave column top in EW direction.

2.3. Test Results

2.3.1. Natural Frequencies of the Test Results

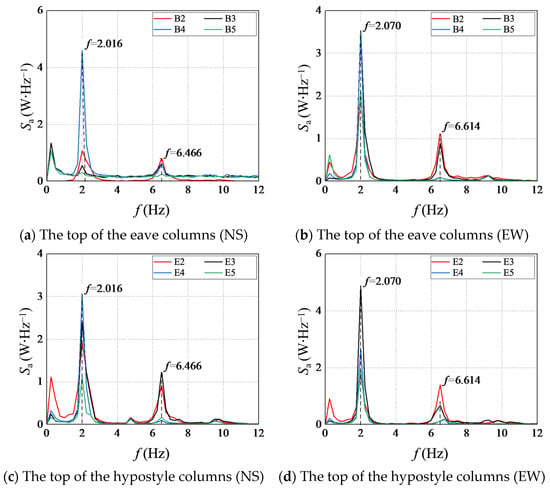

The existing modal parameter identification methods can be broadly classified into time- and frequency-domain methods. The auto-cross power spectrum method was adopted as the most simple and convenient frequency-domain method; it identifies the modal parameters of the structure through the auto-power spectrum analysis of the measurement points and cross-power spectrum analysis between the measuring and reference points. The auto-cross power spectrum analysis was conducted by Dasp during data processing. The mutual-power spectrum amplitude, phase, coherence function, and transferring rates could be output via the responses of the reference points of the 3-purlin beams and the responses of each measurement point. The self-power spectral amplitude could be output via the measurement point’s response itself. The above calculations were combined to identify the modal parameters of the structure.

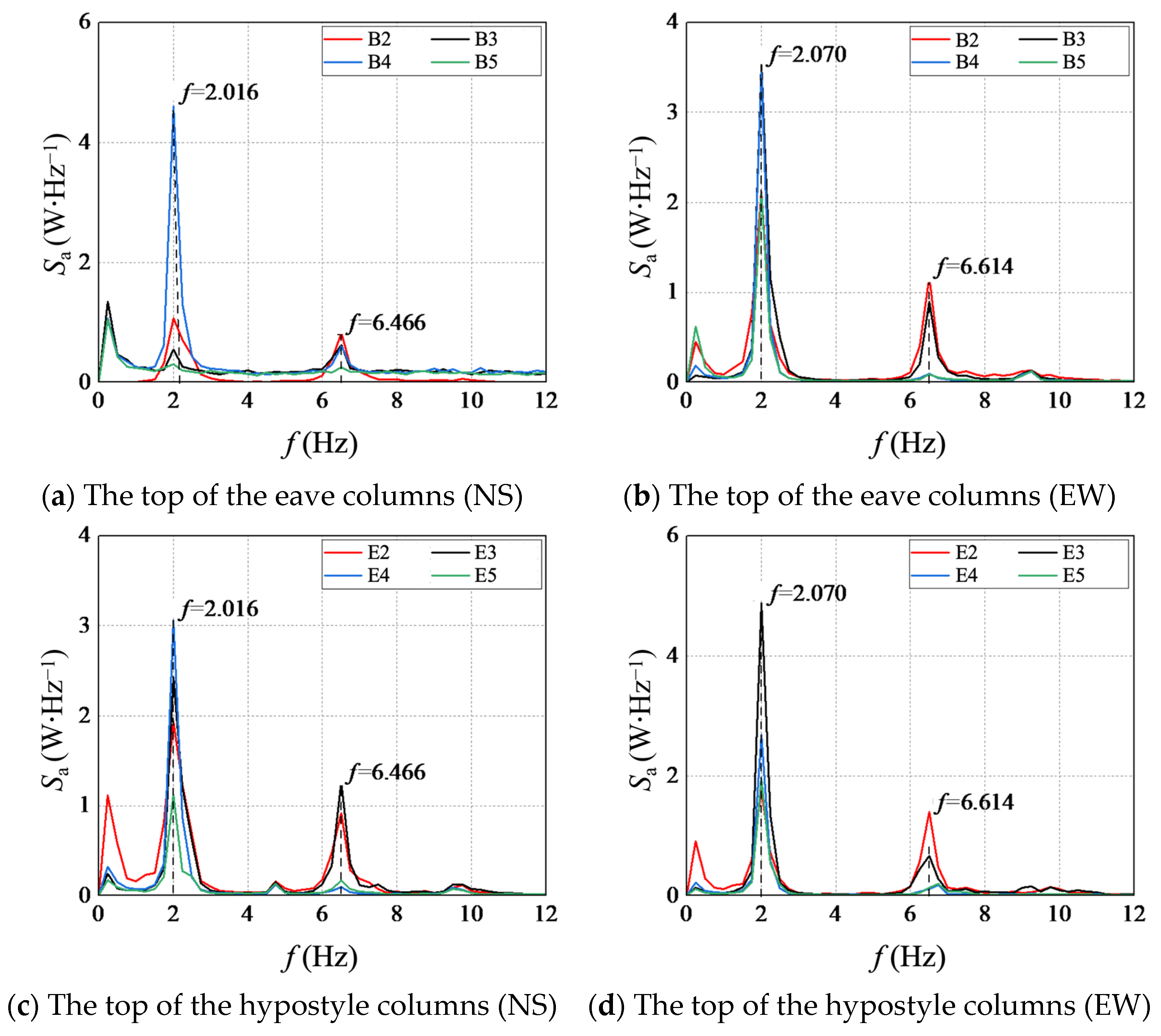

To reduce the interference of alternating current and noise, frequencies that were about four times greater than the highest analysis frequency were filtered out by a low-pass filter to avoid frequency aliasing. Meanwhile, the spectrum line number of the FFT was taken as 4096, and the Hanning window was selected. The phase spectrum and coherence function obtained from the cross-power spectrum analysis were evaluated to exclude spurious modes. If the phase value of a wave peak was at the degrees of 0 or 180 nearby and the coherence coefficient reached more than 90%, the frequency corresponding to the wave peak could be judged to be the natural frequency. Figure 5 shows the auto-power spectrum curves of the measuring points at the top of the hypostyle column, as well as the cross-power spectrum curves, coherence function curve, and phase spectrum curves between the measurement points at the top of the hypostyle column and the inactive reference point in the 3-purlin beam. Here, Sa stands for the power spectral density, and f stands for the frequency. B2, B3, B4, and B5 are hypostyle columns. The natural frequencies of the structure were obtained by auto-cross power spectrum analysis. The average values of 2.016 Hz and 6.466 Hz were regarded as the first and second natural frequencies in the NS direction, while 2.070 Hz and 6.614 Hz were the values in the EW direction, as shown in Table 1.

Figure 5.

Power spectral density–frequency curves of the tops of the columns in the NS and EW directions.

Table 1.

Natural frequencies of the in situ dynamic test of the upper wooden structure.

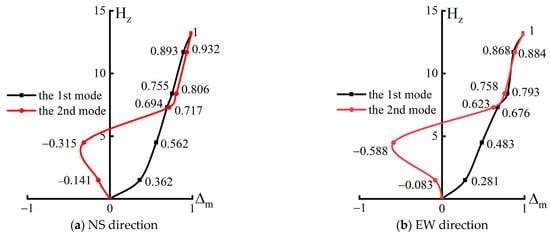

2.3.2. Vibration Modes of the Test Results

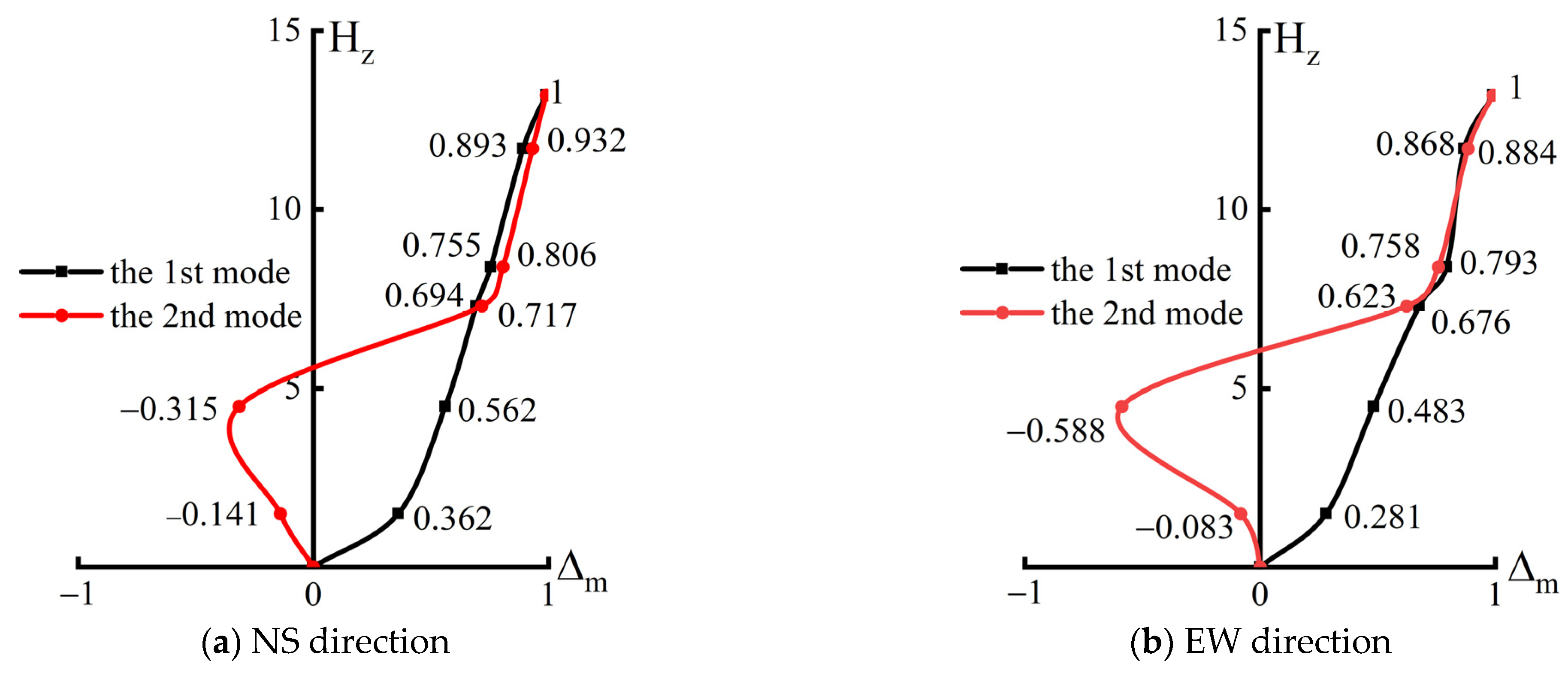

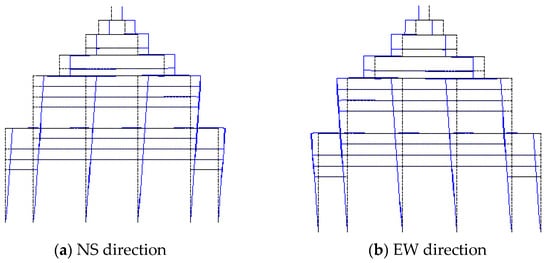

Taking the average vibration response value of the 3-purlin beam as a reference, the ratio of the mean vibration response values of the top and foot of the column, 9-purlin beam, and 5-purlin beam and that of the 3-purlin beam was used to determine the vibration mode coefficient of the structure. The displacement symbol was related to the orientation of the sensor. East and north were regarded as positive directions. As shown in Figure 6, the first and second vibration modes of the structure were translation motions. The first vibration modes of the NS and EW directions revealed that the overall structure was translated in the horizontal direction. The second vibration modes of the NS and EW directions showed that the eave columns swung in the opposite direction relative to the whole. Hz is the height of the measuring point, and Δm is the mode coefficient. Comparing the translation modes in the EW and NS directions, it can be found that the pattern is basically the same in both directions, and, for the first mode, the mode coefficients increase with increasing height; for the second mode, the coefficients all mutate at the height of the top of the outer eave column, which suggests that these columns sway inversely in both directions. The mode coefficients in the NS direction are slightly larger than the values in the EW direction.

Figure 6.

First two translation modes of the upper wooden structure in the NS and EW directions.

3. Dynamic Characteristic Analysis

3.1. Establishment of FE Models

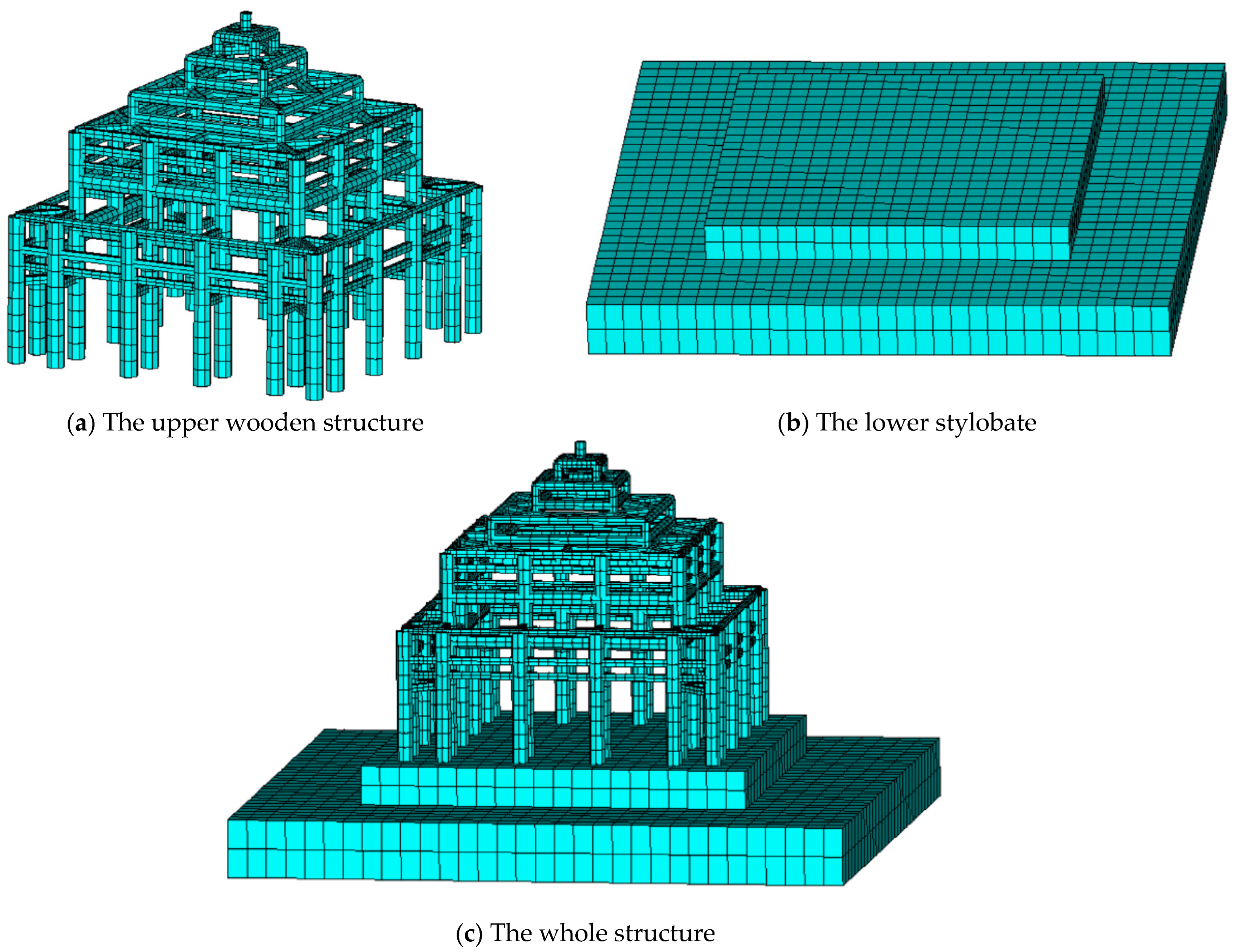

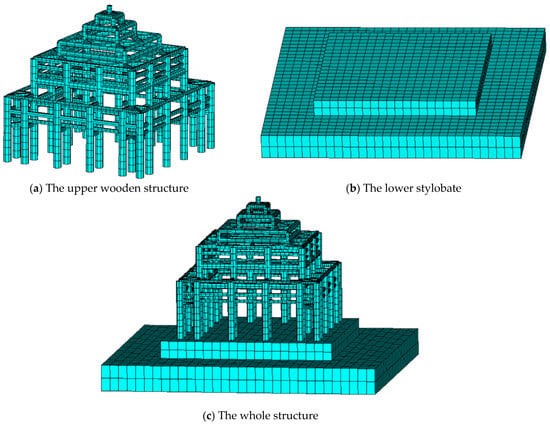

As shown in Figure 7, three finite element models were established through ANSYS to perform the dynamic characteristic analysis. As for the upper wooden structure, the column frame layer consisted of eave and hypostyle columns, which were connected by architraves, Pingban–Fang, and penetrating ties with different section sizes. Rectangular wooden doors and windows were installed around these. The beam frame layer included purlin beams, short posts, corner beams, and straining beams. The dimensions of the main wooden structural members are shown in Table 2. The material properties are shown in Table 3 [28,29], and the wood density was 346 kg/m3. Therefore, the BEAM188 linear finite strain beam element was adopted to simulate these wooden components, as shown in Figure 7a. BEAM188 is a 3D linear finite-strain beam element that is suitable for the analysis of slender to moderately slender members and capable of simulating the effects of bending, shear, and torsion deformation. The pyramid roof with blue-glazed tile cover comprised wooden purlins, rafters, watch bricks, and tubular tiles, which acted on the tops of the hypostyle columns and short posts in the form of a concentrated mass through the MASS21 unit. Mortise–tenon and Dougong brackets were simulated by the COMBIN39 spring element, and the spring stiffness coefficients were obtained through the calculation model in the literature [30,31,32], as shown in Table 4 and Table 5. There were two overlapping end nodes at the intersection of each beam and column. Six COMBIN39 spring elements with zero length and no coupling were set between the two to simulate the mortise–tenon joints with 6 degrees of freedom. The column base constraint condition was hinged because the columns were simply placed on top of the plinth [33]. In the actual structure, the timber column foot floats on the top of the foundation stone, there is no fixed constraint, and it only relies on horizontal friction to transfer the seismic shear force. The lower stylobate is a “Xumizuo” stylobate with two layers, mainly composed of rammed earth and covered with cement blocks of 500 mm × 500 mm × 50 mm on the surface; this was simulated by SOLID45 with eight nodes, as shown in Figure 7b. When establishing the whole structure, the partial size of the first base was taken, and the first floor was fixedly connected to the ground, as shown in Figure 7c. The specific parameter values of the lower stylobate material are shown in Table 6.

Figure 7.

Finite element models of the upper wooden structure, the lower stylobate, and the whole structure.

Table 2.

Dimensions of the main members of the upper wooden structure.

Table 3.

Physical properties of wood.

Table 4.

Parameters of the spring elements of the mortise–tenon joints.

Table 5.

Parameters of the spring elements of the Dougong brackets.

Table 6.

Physical properties of rammed earth.

3.2. Model Validation

With the method of BlockLanczos, the first-order natural frequencies and vibration modes in the NS and EW directions of the upper wooden structure were obtained. The results were then compared with the test results to verify the correctness of the finite element model. During the analysis, the X axis was in the EW direction, and the Y axis was in the NS direction. The errors between the simulated values and the experimental values of the natural vibration frequencies are shown in Table 7.

Table 7.

Comparison between experimental and simulated values of the upper wooden structure.

It can be seen from Table 7 that the first-order natural frequency in the NS and EW directions of the upper wooden structure model was 1.860 Hz and 1.861 Hz. The corresponding errors were 7.74% and 10.10% regarding the experimental values, which were within an acceptable range. This error was derived from an oversight regarding the lateral stiffness of the wall between the columns. There were more walls in the EW direction than in the NS direction, so the relative error was greater. Two vibration modes in the orthogonal directions of the upper wooden structure are shown in Figure 8, which can be described as a translation of the structure in NS and EW, respectively. It indicates that the corresponding vibration modes in each direction are basically consistent with the experimental results. The results above verify the correctness of the numerical model.

Figure 8.

First vibration modes of the calculation model in the NS and EW directions.

3.3. Comparative Analysis of Dynamic Characteristics

3.3.1. Natural Frequencies

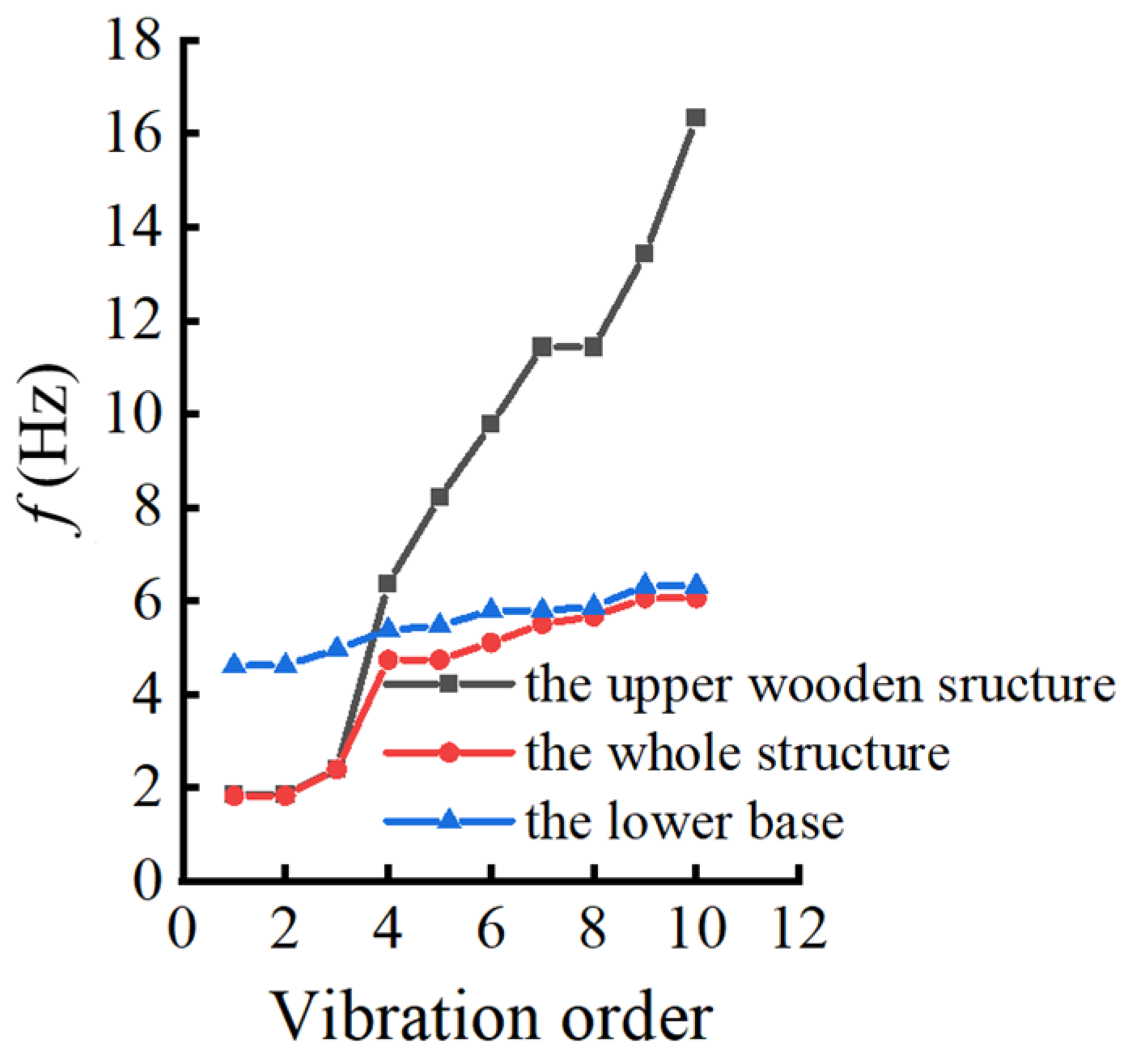

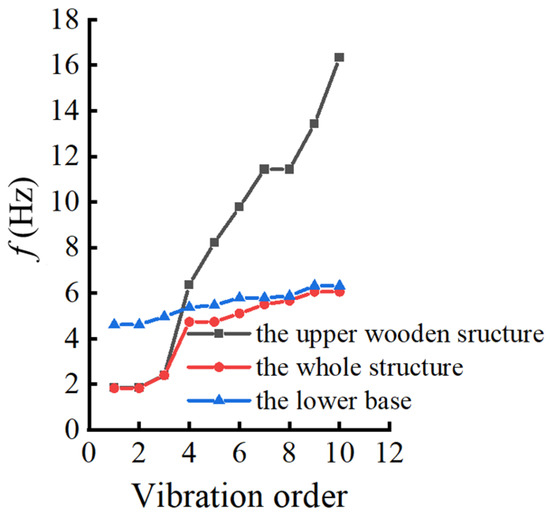

To study the influence of the lower stylobate on the dynamic characteristics of the upper wooden structure, the first ten-order natural frequencies and vibration modes of the three models are analyzed.

As shown in Figure 9, the natural frequencies of the upper wooden structure increase rapidly, especially after the third order. The frequency variation ranges from 1.860 Hz to 16.329 Hz and it is relatively scattered. As for the lower stylobate, the first ten-order natural frequencies vary little as a whole, with a range of 4.613 Hz to 6.320 Hz, which reveals that they are relatively stable. The reason is that, as an important part of the ancient architecture, the lower stylobate has a heavy structure, large volume, and relatively stable physical characteristics. This makes the frequency distribution of the lower stylobate more dense, and the adjacent frequencies are similar, showing stable vibration characteristics. The first ten-order natural frequencies of the whole structure relative to the upper wooden structure are smaller, ranging between 1.821 and 6.054 Hz. The changing amplitude is significantly smaller than that of the upper wooden structure, indicating that the lower stylobate reduces the frequencies of the whole structure. Meanwhile, the first three-order natural frequencies of the whole structure are similar to those of the upper wooden structure, which shows that the lower stylobate does not participate in vibration with the whole structure. Starting from the fourth order, the natural frequencies of the whole structure are close to those of the lower stylobate, which indicates that the lower stylobate begins to participate in the common vibration of the upper wooden structure. This is mainly because the lower stylobate has a great mass and stiffness, which have a significant impact on the vibration characteristics of the whole structure. The above conclusions are consistent with the research results in references [22,23,24], which confirms the reliability of the research conclusions obtained in this work.

Figure 9.

First ten-order natural frequencies of three models.

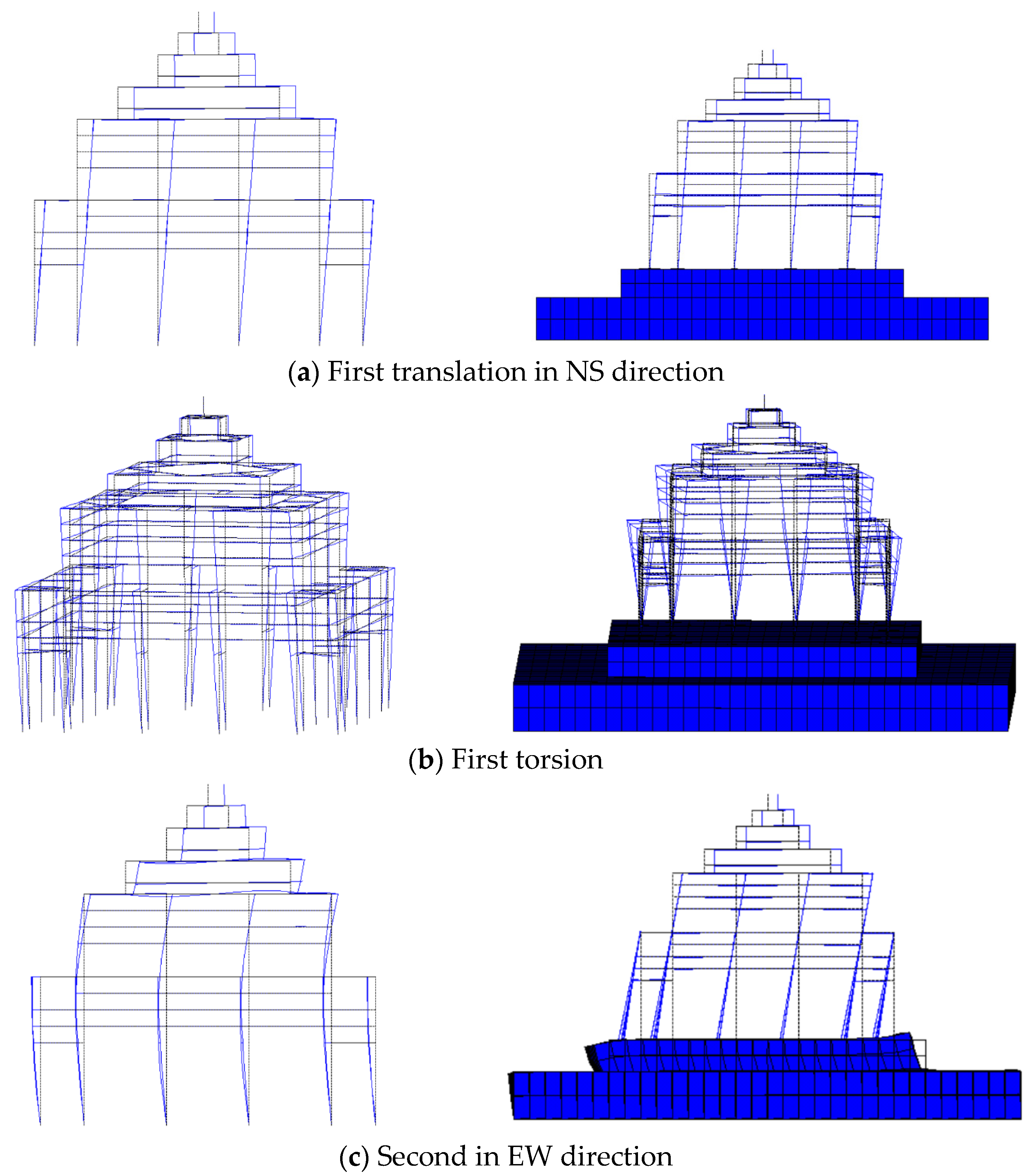

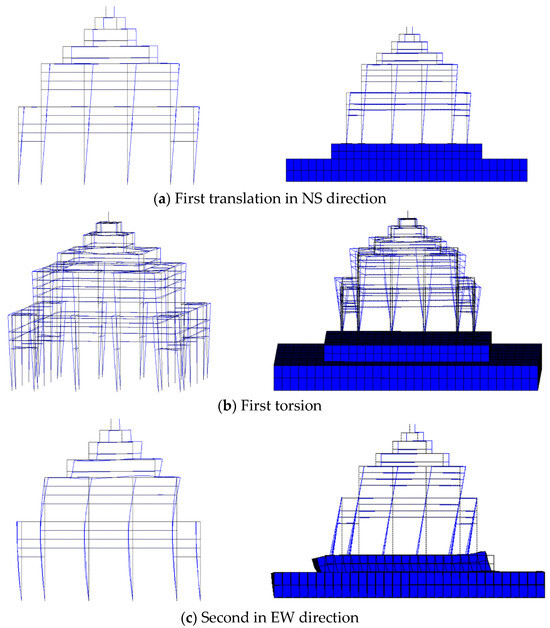

3.3.2. Vibration Modes

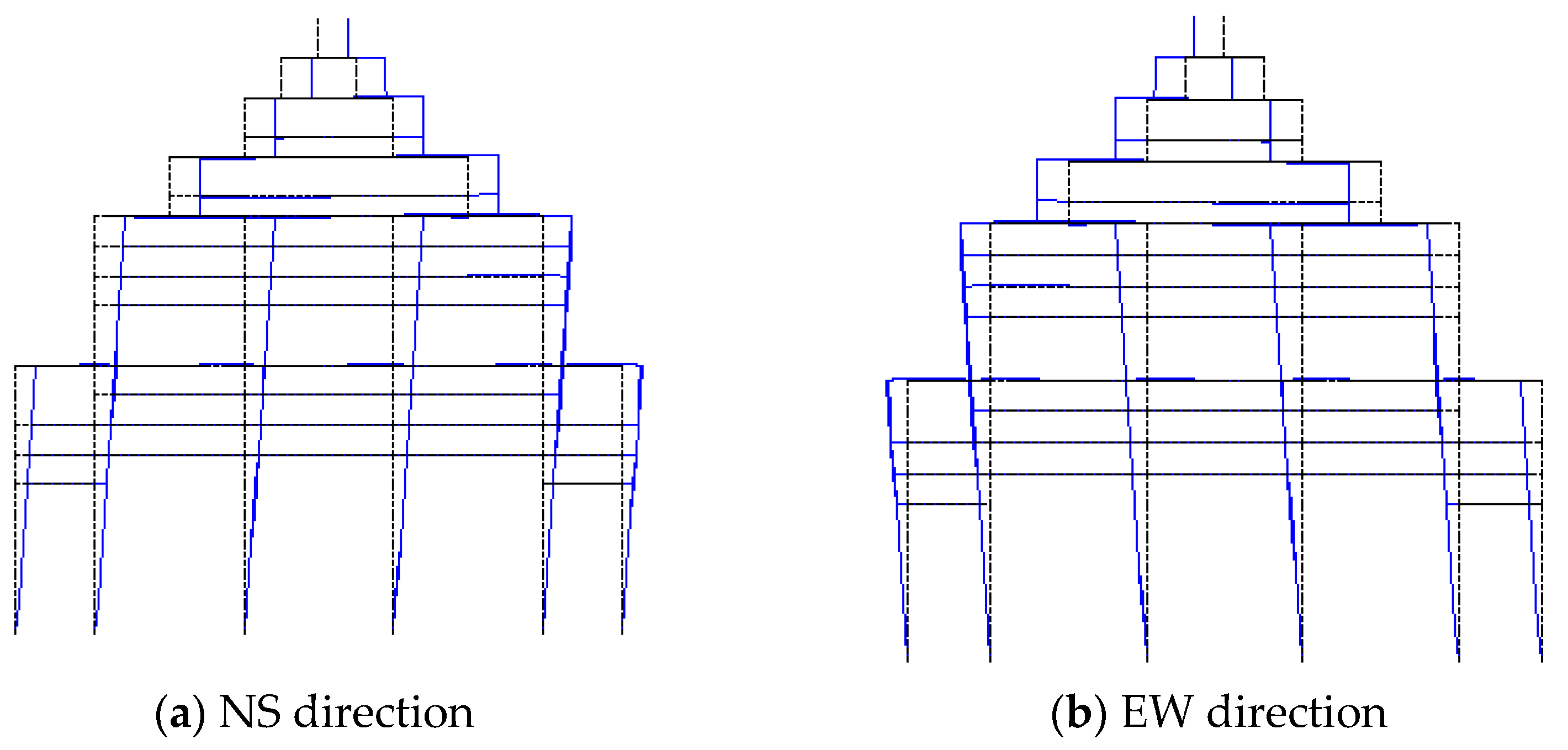

Different natural frequencies correspond to different structural vibration modes, so the lower stylobate affects not only the natural frequencies but also the corresponding vibration modes to a certain extent. Figure 10 shows several vibration modes of the upper wooden structure and the whole structure. For the upper wooden structure, the first two vibration modes of the upper wooden structure model are horizontal vibrations in the main axis direction, and the third vibration mode is torsion. However, the first three vibration modes of the whole structure are dominated by the upper wooden structure. The reason is that the stylobate does not participate in the structural vibration. After the third order, the corresponding vibration modes change. The lower stylobate vibrates together with the upper wooden structure.

Figure 10.

Several vibration modes of the upper wooden structure and the whole structure.

The modal participation mass coefficient was adopted to measure the contribution of each vibration mode to the response of the structure, and those of the upper wood structure and the whole structure were calculated, respectively. As shown in Table 8, the modal participation mass coefficient of the upper wooden structure of the first two orders is 0.918 in each direction, which indicates that the first two-order vibration modes of the calculation models contribute significantly. Table 9 shows the modal participation mass coefficient of the whole structure. It shows that the first three vibration modes in the NS direction of the whole structure contribute little to the response, while the modal participation mass coefficient of the fourth vibration mode is 0.8951, and the contribution of the first four vibration modes to the response reaches 92.45%. However, the modal participation mass coefficient of the first four modes in the EW direction is minimal, and that of the fifth mode is 0.8951. The contribution of the first five modes to the response is up to 92.78%. When considering the common work of the lower stylobate, the first five-order vibration modes contribute significantly to the response for the whole structure, and the lower stylobate vibrates from the fourth order.

Table 8.

Modal participation mass coefficient of the upper wooden structure.

Table 9.

Modal participation mass coefficient of the whole structure.

4. Seismic Response Analysis

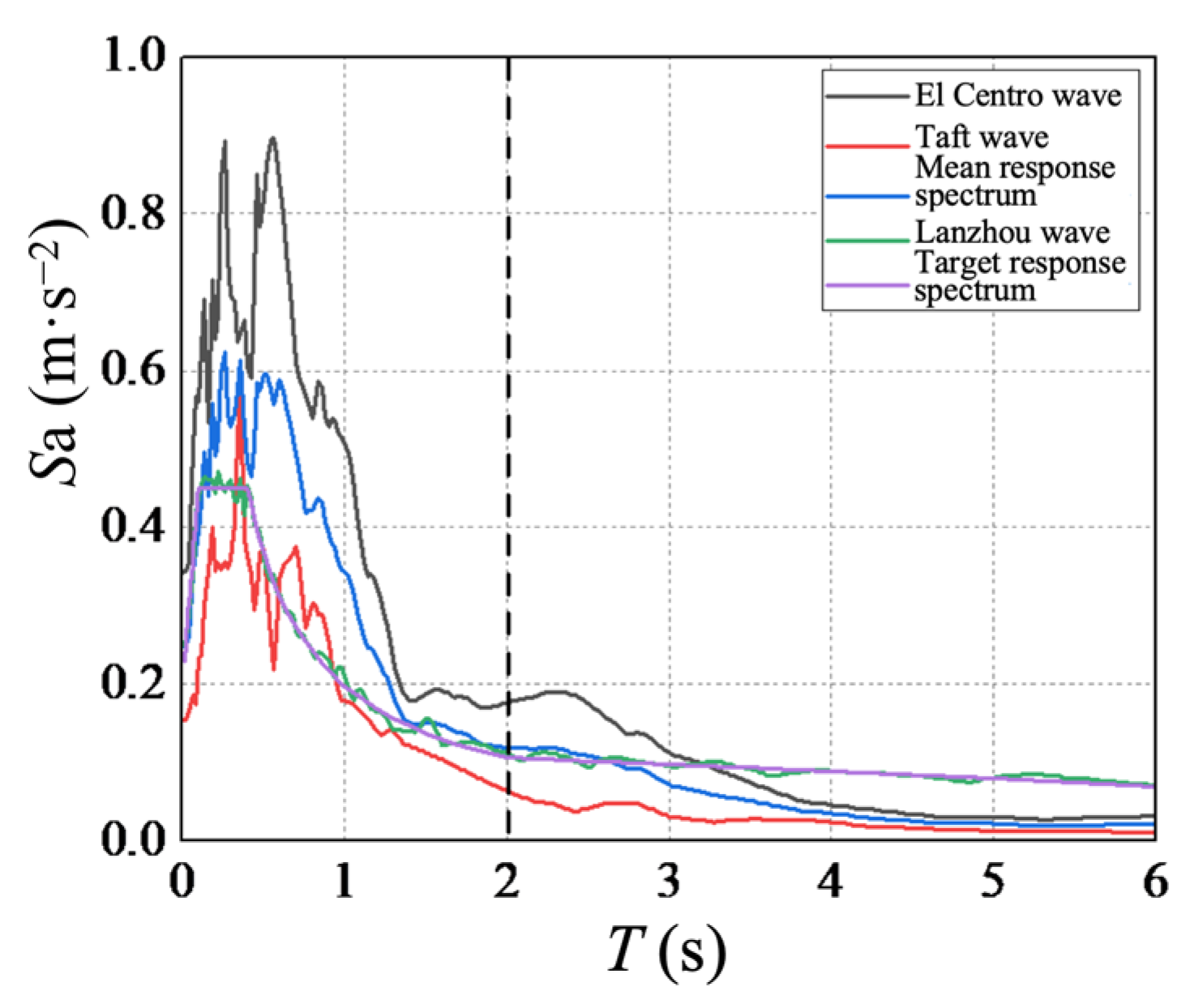

4.1. Seismic Wave Selection

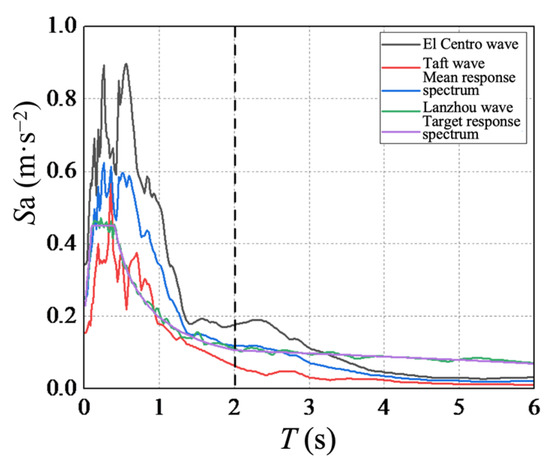

The Chen Xiang Pavilion is located in the eight-degree seismic fortification zone with the designated basic seismic acceleration value of 0.2 g. The site category is classified as II, and the designated earthquake group is the second group. In terms of the “Code for Seismic Design of Buildings” (GB 50011-2010) [34], the El Centro wave, Taft wave, and Lanzhou artificial wave, suitable for class II sites, were selected as structural seismic excitations. A comparison between the seismic response spectrum and design response spectrum is shown in Figure 11, where Sa represents the spectral acceleration, and T represents the natural vibration period of the structure. Furthermore, amplitude modulation was carried out based on the seismic intensity. The peak accelerations were adjusted to 70 cm/s2 (frequent earthquake), 200 cm/s2 (fortification earthquake), and 400 cm/s2 (rare earthquake). Considering that the peak seismic accelerations occurred in the first 20 s, the time history records of the first 20 s of the three seismic waves were chosen as the seismic wave input [35,36].

Figure 11.

Comparison between seismic response spectrum and target response spectrum.

The assumption of Rayleigh proportional damping was used to facilitate the mathematical calculations. It was assumed that the damping matrix was a linear combination of the mass matrix [M] and the stiffness matrix [K], and the damping matrix [C] was given as

where α and β are the mass damping coefficient and the stiffness damping coefficient, respectively.

According to the structural dynamics, the r-th modal damping ratio ξr can be expressed as

where Cr stands for the damping coefficient of the system, and ωr is the natural angular frequency.

The natural angular frequency ωr was calculated as follows:

From Equations (2) and (3), the modal damping ratio ξr was obtained as follows:

In Equation (4), α and β are given as

where the corresponding natural angular frequencies ωi and ωj with the most significant contribution to the structure are selected; ξi and ξj are the damping ratios of the corresponding vibration modes.

From Section 3.3.2, it is clear that ωi and ωj are the first- and second-order natural angular frequencies of the upper wooden structure. However, for the whole structure, ωi and ωj are the first- and fourth-order natural angular frequencies because the lower stylobate participates in the vibration starting at the fourth order. According to Zhang’s research [37], the damping ratios were 3.2%, 3.5%, and 3.9%, corresponding to the seismic excitation with peak acceleration of 100 cm/s2, 200 cm/s2, and 400 cm/s2.

4.2. Comparative Analysis of Seismic Response

4.2.1. Displacement Response

Seismic waves of different peak accelerations apg were applied to the upper wooden structure and whole structure models. Then, the influence of the lower stylobate on the seismic response of the Chen Xiang Pavilion was analyzed. Since the Chen Xiang Pavilion is symmetrical and the layout is regular, the X axis was the main excitation direction selected for the seismic wave input. At the same time, taking the top of the hypostyle column as the research object, the maximum displacement response Δmax, the maximum acceleration response amax, and the maximum inter-structural layer drift angle θmax in different working conditions were obtained, as shown in Table 10. Here, θmax is obtained by dividing the maximum displacement response Δmax of the hypostyle column top by the column height.

Table 10.

Peak displacement response, inter-structural layer drift angle, and acceleration response in hypostyle column tops of two models.

It can be seen from Table 10 that the displacement response in the two models was the smallest under the Lanzhou wave compared with the El Centro wave and the Taft wave. This is because the frequency spectrum characteristics and durations of different waves are different, which leads to differences in the seismic responses. With an increment in the seismic excitation, the displacement responses of the two models showed an increasing trend. Meanwhile, it is worth noting that the displacement responses of the whole structure were larger than those of the upper wooden structure under the same intensity of seismic excitation. For instance, under the action of the Taft wave with the peak acceleration of 200 cm/s2, the displacement response of the whole structure was up to 1.99 times larger relative to that of the upper wooden structure, indicating that the lower stylobate had a significantly enlarged effect on the displacement response of the upper wooden structure. Therefore, the existence of the lower stylobate changed the structural form and height of the upper wooden structure, which increased the displacement response of the upper wooden structure.

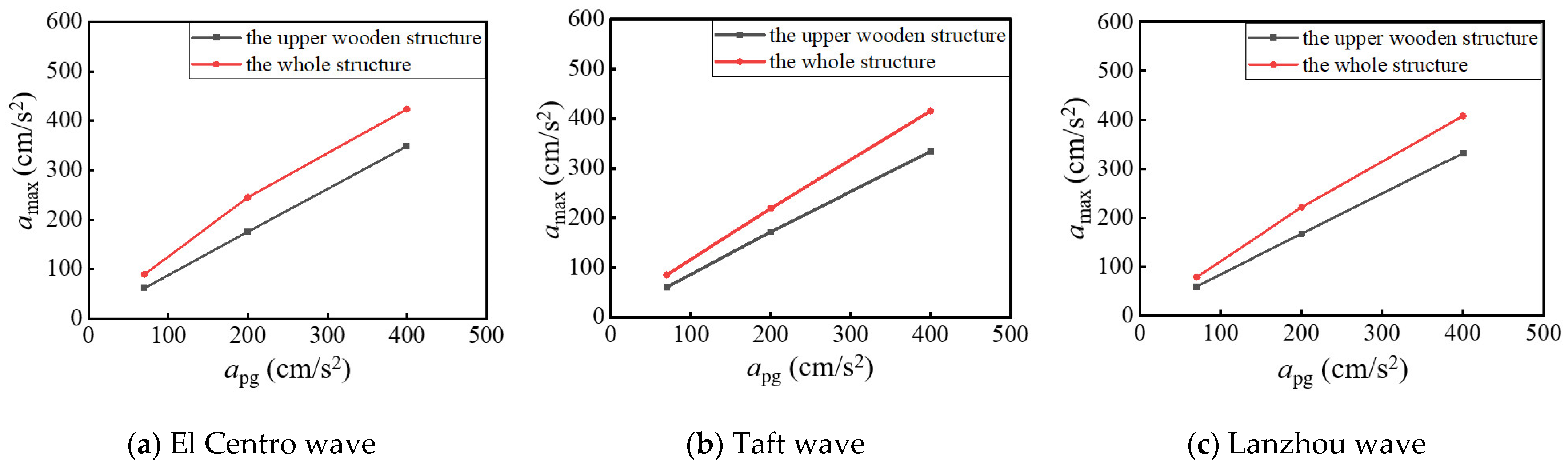

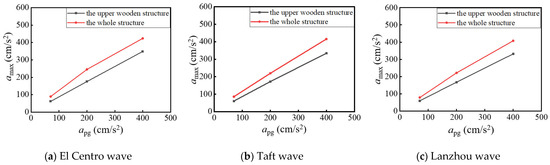

4.2.2. Acceleration Response

Figure 12 shows the maximum acceleration response amax of the hypostyle columns of the two models when different seismic excitations are applied. It reveals that the maximum acceleration response presents an increasing trend with the increase in the seismic excitation intensity. In addition, the maximum acceleration responses of the upper wooden structure are smaller than those of the whole structure under different seismic excitations with the same peak acceleration.

Figure 12.

Peak acceleration response.

The dynamic amplification coefficient β was adopted to analyze the change rule of the maximum acceleration response of each position. It can be expressed as the ratio of the maximum acceleration to the input acceleration amplitude. When β is less than 1, it indicates that the structure has a decay effect on the acceleration. The smaller the value of β, the more pronounced the decay effect. When β is more than 1, it means that the structure has an amplification effect on the acceleration. The larger the value of β, the stronger the amplification effect. Table 11 presents the dynamic amplification coefficients of the two models in different positions. The dynamic amplification coefficient β of the wooden structure ranged from 0.742 to 0.948 and generally decreased with the seismic intensity because the flexible Dougong brackets and mortise–tenon joints could effectively dissipate the energy. However, the dynamic amplification coefficient β of the whole structure was larger than that of the upper wooden structure, with a range of 1.024 to 1.776. This phenomenon could be explained by the lower stylobate amplifying the dynamic response of the upper wooden structure, proving that the lower stylobate is unfavorable to the seismic resistance of the structure. Furthermore, the dynamic amplification coefficients of the two models tended to decrease with the seismic intensity, which reflects the good vibration isolation and energy consumption of the Chen Xiang Pavilion.

Table 11.

Dynamic amplification coefficients of the two models.

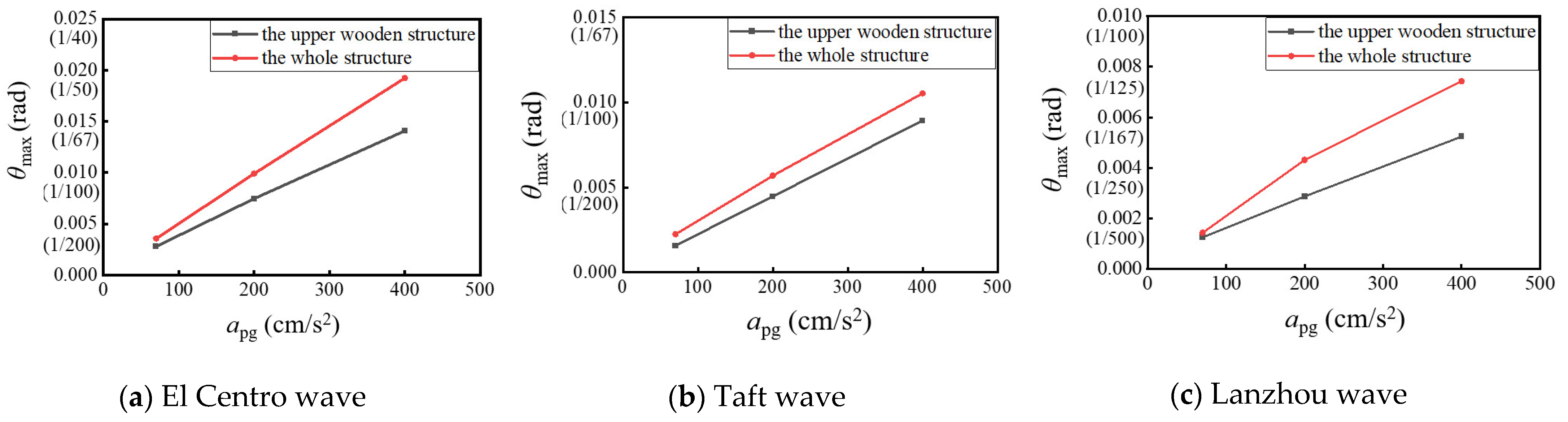

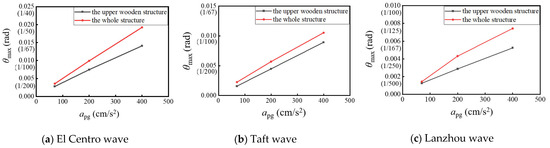

4.2.3. Inter-Structural Layer Drift Angle

To further determine the influence of the lower stylobate on the upper wooden structure, the structural layer drift angles of the two models were obtained. As shown in Table 10 and Figure 13, with the increase in the intensity of the seismic waves, the inter-structural layer drift angles of both the upper wooden structure and the whole structure increase. Meanwhile, the inter-structural layer drift angle of the whole structure is larger than that of the upper wooden structure, and the increments are larger than 15.1%, indicating that the lower stylobate amplifies the inter-structural layer drift angle of the upper wooden structure. From Table 10, the inter-structural layer drift angle is the largest at 1/52 rad (0.019 rad) under rare earthquakes, which does not exceed the maximum structural drift angle θmax of 0.033 rad as required in the Technical Standard for the Maintenance and Enhancement of Wood Structures of Ancient Buildings [38]. It can be concluded that the Chen Xiang Pavilion has good deformation and collapse resistance. Furthermore, it is found that the inter-structural layer drift angles of the two models under the El Centro wave are the largest, and the angles under the Lanzhou wave are the smallest.

Figure 13.

Maximum inter-structural drift angle.

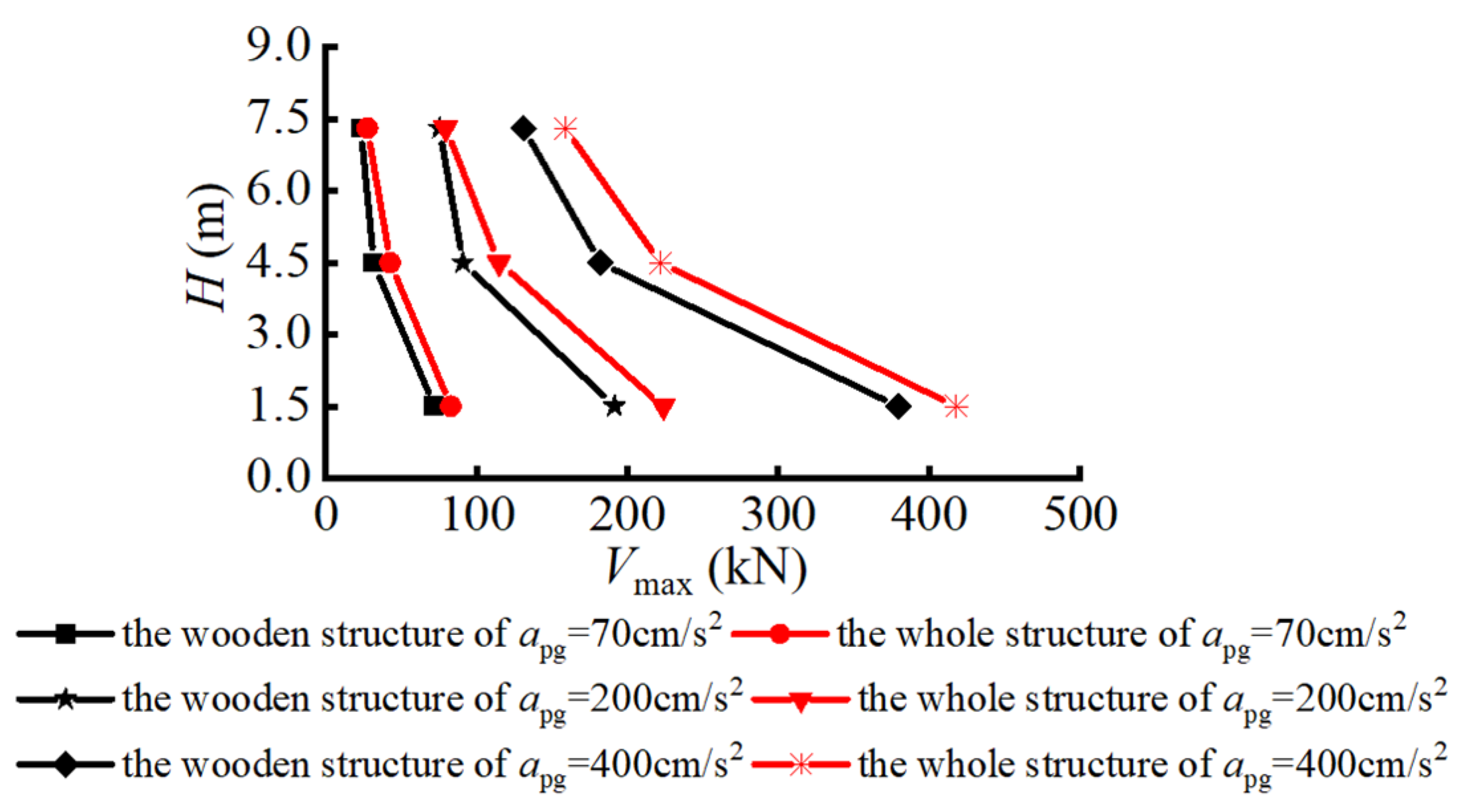

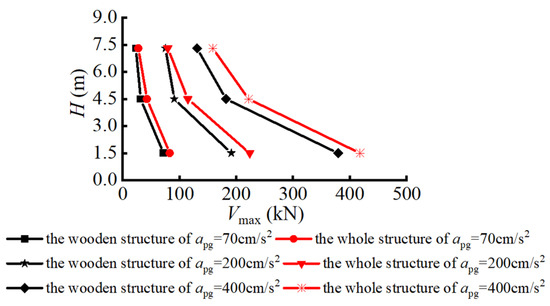

4.2.4. Shear Force of Layer

The maximum shear force Vmax of the layer was also calculated by summarizing the maximum shear values of all columns and short posts at the top or foot under different seismic wave conditions, as shown in Table 12. The maximum shear force of the layer in two models under the El Centro wave was the largest, as shown in Figure 14.

Table 12.

Maximum shear force of layer in two models.

Figure 14.

Maximum shear force of layer under El Centro wave.

As seen from Table 12 and Figure 14, the maximum shear force of the layer in the upper wooden structure and the whole structure decreases gradually from top to bottom under the different seismic wave conditions. With an increment in the seismic excitation intensity, the maximum shear force of the layer in the two models also increases. Moreover, it is concluded that the maximum shear force of the layer in the whole structure model is greater than that in the wooden structure model. This shows that the lower stylobate magnifies the maximum shear force of the layer in the upper wooden structure and affects the lateral resistance of the structure.

The shear increment is defined to analyze the influence of the lower stylobate on the structural shear force. The calculation results regarding the structural shear increment are listed in Table 13, where it can be seen that the structural shear force was magnified to a certain extent under different seismic wave excitations. Under the excitation of the El Centro wave, the increment in the structural shear force was between 15.3% and 20.4%; Under the excitation of the Taft wave, the increment in the structural shear force was between 18.9% and 21.3%. Meanwhile, under the excitation of the Lanzhou wave, the increment in the structural shear force was the largest, with a range of 24.8~34.7%. The results indicate that the structural shear force was significantly magnified, up to 34.7%, which resulted from the change in the structure’s form and the height of the upper wooden structure caused by the lower stylobate. An existing case study reached a similar conclusion [39].

Table 13.

Maximum shear force of layer in two models.

5. Conclusions

In situ dynamic tests and finite element analysis were conducted to study the influence of the lower stylobate on the dynamic characteristics and dynamic response of an upper wooden structure. The conclusions are summarized as follows.

- (1)

- The in situ dynamic test on the Xi’an Chen Xiang Pavilion showed that the first and second frequencies of the upper wooden structure in the NS direction were 2.016 Hz and 6.466 Hz, while they were 2.07 Hz and 6.614 Hz in the EW direction.

- (2)

- The first ten-order natural frequencies of the upper wooden structure, the lower stylobate, and the whole structure ranged from 1.860 Hz to 16.329 Hz, 4.613 Hz to 6.320 Hz, and 1.821 and 6.054 Hz, respectively. The first three-order natural frequencies of the whole structure are similar to those of the wooden structure and close to those of the lower stylobate from the fourth order. The lower stylobate significantly affects the dynamic characteristics of the upper wooden structure after the third order. This research conclusion is similar to those of previous research.

- (3)

- The lower stylobate amplifies the seismic response of the upper wooden structure. The displacement response of the whole structure is up to 1.99 times larger relative to that of the upper wooden structure. The inter-structural layer drift angle was increased by more than 15.1%. The largest inter-structural layer drift angle of the whole structure was 1/52 when the El Centro wave with the peak acceleration of 400 cm/s2 was applied, which did not exceed the limit of 1/30.

- (4)

- The dynamic amplification coefficient of the upper wooden structure ranged from 0.742 to 0.948, while that of the whole structure was between 1.024 and 1.776. The lower stylobate is unfavorable to the seismic resistance of the structure, even though the energy dissipation capacity of the Chen Xiang Pavilion increases with the excitation strength.

- (5)

- The shear force of the whole structure is magnified by more than 15.3% compared with the upper wooden structure. Therefore, it is unsafe to perform the seismic assessment of the structure without considering the impact of the lower stylobate.

The limitation of this work is that the FE modeling method needs to be further optimized. The column foot connection was simplified as a hinge connection, without considering the swinging motion. In addition, the material properties of the rammed soil in the base of the lower stylobate were adopted from the literature, derived from the parameters of similar structures, and further experiments are needed to obtain accurate material properties.

Author Contributions

Writing—original draft preparation, K.L.; software and formal analysis, H.L.; data curation, B.X.; supervision and writing—reviewing and editing, C.W.; conceptualization, methodology, resources, project administration and funding acquisition, J.X.; investigation and validation, D.S.; visualization, H.X. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 52308328, 52278317, 51908454), the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (No. 2023M732748), and the Preventive Conservation and Inheritance of Ancient Architecture “Scientist + Engineer” Teams (No. 2024QCY-KXJ-169).

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Notation List

| v | velocity of the eave column top | d1, d2 | yielding and ultimate displacement |

| d | displacement of the eave column top | K3, Kθ3 | elastic stiffness of tension spring and rotating spring of Dougong brackets |

| t | time history | K4, Kθ4 | stiffness in strengthening stage of tension spring and rotating spring of Dougong brackets |

| Sa | power spectral density | γ | modal participation mass coefficient |

| f | frequency | r | mode contribution |

| NS | north–south direction | T | natural vibration period |

| EW | east–west direction | [M], [K], [C] | mass matrix, stiffness matrix, damping matrix |

| Hz | height of the measuring point | α, β | mass and stiffness damping coefficient |

| Δm | mode coefficient | ξ | damping ratio |

| D, H, W | diameter, height, and width of components | Cr | damping coefficient |

| E, μ, G, ρ | elastic modulus, shear modulus, Poisson’s ratio, and density of wood | ωr | natural angular frequency |

| L, R, T | longitudinal, radial, and tangential directions of wood | apg | peak acceleration |

| θ1, θ2 | yielding and ultimate rotation | Δmax, Vmax, amax, θmax | maximum displacement, shear force, acceleration, and inter-structural layer drift angle |

| K1, Kθ1 | elastic stiffness of tension spring and rotating spring of mortise–tenon joints | β | dynamic amplification coefficient |

| K2, Kθ2 | stiffness in strengthening stage of tension spring and rotating spring of mortise–tenon joints | η | shear force increment |

| U, ROT | translational and rotating degrees of freedom |

References

- Qiao, E.M.; Ding, Q.; Shang, D.W.; Hou, Z.G. Analysis and interpretation of the protection of ancient buildings in urban design. Front. Soc. Sci. Technol. 2020, 2, 59–61. [Google Scholar]

- Sui, Y.; Zhao, H.T.; Xue, J.Y.; Xie, Q.F.; Wu, L. Experimental study of the seismicity of dougong and wooden frame in Chinese historic buildings. China Civ. Eng. J. 2011, 44, 50–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.X.; Du, J.D.; Zhang, H.M.; He, H.J.; Bao, C.; Liu, Y. Mechanical properties of multi-bolted glulam connection with slotted-in steel plates. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 433, 136608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wei, G.Q.; Lv, X.M.; Meng, Z.B. Dynamic testing and finite element model adjustment of the ancient wooden structure under traffic excitation. Buildings 2024, 14, 3527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.J.; Song, X.B.; Gu, X.L.; Luo, L. Dynamic performance of a multi-story traditional timber pagoda. Eng. Struct. 2018, 159, 277–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Q.F.; Xu, D.F.; Zhang, Y.; Yu, Y.W.; Hao, W.M. Shaking table testing and numerical simulation of the seismic response of a typical China ancient masonry tower. Bull. Earthq. Eng. 2020, 18, 331–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.C.; Xue, J.Y.; Zhao, H.T.; Sui, Y. Experimental study on Chinese ancient timber-frame building by shaking table test. Struct. Eng. Mech. 2011, 40, 453–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, J.Y.; Wu, Z.J.; Zhang, F.L.; Zhao, H.T. Seismic damage evaluation model of Chinese ancient timber buildings. Adv. Struct. Eng. 2015, 18, 1671–1683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.A.; Yang, Q.S.; Wang, J.; Qin, J.W. Dynamic performance of the ancient architecture of Feiyun pavilion under the condition of environmental excitation. J. Vib. Shock. 2015, 34, 144–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Yang, N.; Bai, F.; Cheng, P. Research on the dynamic characteristics of Tibetan ancient city wall based on ambient excitation. China Civ. Eng. J. 2021, 54, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.W.; Xue, J.Y.; Zhou, S.Q.; Zhang, F.L. Seismic performance evaluation for a traditional Chinese timber-frame structure. Int. J. Archit. Herit. 2021, 15, 1842–1856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, J.Y.; Wu, C.W.; Zhai, L.; Wang, R.P. Ma, L.L. Finite element analysis on seismic response of Yingxian Wooden Tower by considering the effect of the stylobate. J. Civ. Environ. Eng. 2022, 44, 22–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.Y.; Wei, J.W.; Zhang, S.Y.; Li, S.W. Experiment and analysis of vibration characteristics of Yingxian wooden tower. Eng. Mech. 2005, 22, 141–146. [Google Scholar]

- Che, A.L.; He, Y.; Ge, X.R.; Iwatate, T.; Qda, Y. Study on the dynamic structural characteristics of an ancient timber: Yingxian Wooden Pagoda. Soil Rock Behav. Model. 2006, 390–398. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, Y.; Yi, D.H.; Chen, J.; An, R.B. Analysis on dynamic characteristics and seismic response of Lingguan deity hall in Qingcheng Mountain by considering effects of wall. J. Build. Struct. 2022, 43, 95–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foti, D.; Diaferio, M.; Giannoccaro, N.I.; Mongelli, M. Ambient vibration testing, dynamic identification and model updating of a historic tower. NDT E Int. 2012, 47, 88–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, X.C.; Meng, Z.B.; Wang, X.; Gao, F.F.; Zhang, T. Analysis on dynamic characteristics and seismic response of wooden structure of South Gate Building in Jiangzhang Town. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2022, 2148, 012046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, D.F.; Li, W.; Ding, X.J.; Cao, P.N. Analysis on structural property and seismic performance of the P’ai-Lou gateways in Xi’an Great Mosque. Adv. Mater. Res. 2011, 295, 1441–1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.X.; Zhao, S.C.; Pan, Y.; Yan, Y.J. Seismic analysis and research of gate tower of Shangqing Temple on Qingcheng Mountain. J. Sichuan Univ. (Eng. Sci. Ed.) 2010, 42, 292–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Hu, J.X.; Zhang, B.J.; Sun, M.; Wang, S.L. Dynamic characteristics analysis and finite element simulation of an ancient timber building under environmental excitation. Buildings 2024, 14, 771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakkar, A.R.; Elyamani, A.; EI-Attar, A.G.; Bompa, D.V.; Elghazouli, A.Y.; Mourad, S.A. Dynamic characterisation of a heritage structure with limited accessibility using ambient vibrations. Buildings 2023, 13, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.T.; Ma, H.; Xue, J.Y.; Zhang, F.L.; Zhang, X.C. Analysis of dynamic characteristics and seismic response of the ancient timber building on high-platform base. J. Earthq. Eng. Eng. Vib. 2011, 31, 115–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.; Yan, W.M.; Zhou, X.Y.; Jin, J.B. Study on dynamical character and seismic response of Shen-Wu Gate in the Forbidden City. Earthq. Resist. Eng. Retrofit. 2009, 31, 90–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, J.Y.; Wu, C.W.; Hao, F.H.; Ma, L.L. In situ experiment and finite element analysis on dynamic characteristics of Yingxian Wooden Tower. J. Build. Struct. 2022, 43, 85–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, Y.W.; Chun, Q.; Guo, H.Y. Modified structural computing model of ancient city gate tower with method of structural dynamical characteristic test-a case study of Nanjing Drum Tower. J. Basic Sci. Eng. 2020, 28, 407–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; He, J.X.; Yang, N.; Yang, Q.S. Study on a seismic characteristic of Tibetan ancient timber structure. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2017, 2017, 8186768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB/T 50452-2008; Technical Code for Preventing Industrial Vibration of Ancient Buildings. China Architecture and Building Press: Beijing, China, 2008. (In Chinese)

- Fang, D.P.; Iwasaki, S.; Yu, M.H.; Shen, Q.P.; Miyamoto, Y.; Hikosaka, H. Ancient Chinese timber architecture. I: Experimental study. J. Struct. Eng. 2001, 127, 1348–1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB 50005-2017; Standard of Design of Timber Structures. China Building Industry Press: Beijing, China, 2017. (In Chinese)

- Xie, Q.F.; Du, B.; Xiang, W.; Zheng, P.J.; Cui, Y.Z.; Zhang, F.L. Experimental study on seismic behavior and size effect of dovetail mortise-tenon joints of ancient timber buildings. J. Build. Struct. 2015, 36, 112–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, X.Y.; Guo, R. Research on mechanical model of dovetail joint for Chinese ancient timber structures. J. Build. Struct. 2021, 42, 151–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; An, R.B.; Wang, X.Y.; Guo, R. Study on mechanical model of through-tenon joints in ancient timber structures. China Civ. Eng. J. 2020, 53, 61–70+82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; He, J.X.; Yang, Q.S.; Yang, N. Study on mechanical behaviors of column foot joint in traditional timber structure. Struct. Eng. Mech. 2018, 66, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB 50011-2010; Code for Seismic Design of Buildings. China Architecture and Building Press: Beijing, China, 2010. (In Chinese)

- Forcellini, D.; Tanganelli, M.; Viti, S. Response site analyses of 3D homogeneous soil models. Emerg. Sci. J. 2018, 2, 238–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradley, B.A. A generalized conditional intensity measure approach and holistic ground-motion selection. Earthq. Eng. Struct. D 2010, 39, 1321–1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.C.; Ma, H.; Zhao, Y.L.; Zhao, H.T. Dynamic responses on traditional Chinese timber multi-story building with high platform base under earthquake excitations. Earthq. Struct. 2020, 19, 331–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB/T 50165-2020; Technical Standard for Maintenance and Strengthening of Ancient Timber Buildings. China Architecture and Building Press: Beijing, China, 2020. (In Chinese)

- Xue, J.Y.; Wu, C.W.; Zhou, S.Q.; Zhang, F.L. Analysis on dynamic characteristics and seismic response of the Anding Gate Tower in Xi’an considering high stylobate. J. Build. Struct. 2021, 42, 12–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).