Abstract

Because of the remarkable interest in preserving the architectural heritage of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia and the emergence of multiple models of adaptively reused heritage buildings in the historic Jeddah area, it is necessary to ensure their correct usage, periodic evaluation, and sustainability. This study develops a model for evaluating the adaptive reuse of historical buildings to preserve their integrity and originality. It adopts a qualitative approach and analyzes references and charters, as well as classifications and methodologies associated with the adaptive use of heritage buildings. The model consists of two main axes. The first includes the basic information on the building, and the second includes elements and criteria for reuse, restoration, and repair, as well as intangible elements of the cultural heritage that can improve people’s livelihoods. It was judged by five architectural heritage specialists in the region to ensure comprehensiveness. This study will draw the attention of those responsible for preserving heritage buildings toward the need for the periodic evaluation of buildings, which can be done through use of the model, to ensure the authenticity and sustainability of historical buildings during reuse and determine if activities should continue or be halted.

1. Introduction

The Kingdom of Saudi Arabia pays great attention to preserving cultural heritage of all kinds. It has registered a number of tangible and intangible heritage sites in the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization. One such site is historic Jeddah [1], which became a tourist destination for visitors and an avenue to learn about the region’s cultural heritage, lifestyle, customs, and traditions, making tourism investment one of the pillars of the Kingdom’s vision for 2030 [2].

With heritage buildings considered an area of investment, investors and building owners began taking advantage of the adaptive reuse of heritage buildings in line with state directions, and multiple models for reused buildings have emerged in Jeddah. As for the concept of adaptive reuse in Saudi Arabia, we find that there are no plans and policies to develop and implement reuse. The concept suffers from randomness and marginalization [3]. So, this study aims to develop a model for evaluating the adaptive reuse of heritage buildings and improve preservation methods.

The study question is, what are the axes for evaluating the adaptive reuse of heritage buildings? This study will aid in the periodic evaluation of reused buildings by officials and interested parties, and the proposed model has related parts that can support university students in their architectural heritage projects to ensure the effectiveness and excellence of designs that contribute to preserving the integrity and authenticity of historical buildings.

1.1. Adaptive Reuse of Buildings

Heritage buildings are a witness to previous civilizations and are an important element in transmitting cultural identity through generations. Since these buildings cannot be used for their original purpose, proposing a new function is necessary to ensure their preservation [4]. This process, which is called adaptive reuse, involves modifying and adapting old buildings for new uses while preserving their historical value [4,5]. Most of the old buildings have had a change in function to suit contemporary social needs [6]. This happens when a stable building is given a unique architectural character through a new function, provided that the impact of the new function on the building is minimal, so as not to lose its originality [5,7]. Snyder [8] argues that the reused building does not have to be an important piece of architecture for the process to be successful, but it is necessary to respect the building’s history and structure when a new function is introduced. Successful adaptive reuse respects the heritage values of a building while pursuing the development of a modern appearance that does not affect its originality [7]. This is important to pass on the authentic heritage to future generations without distortion [4]. Others confirm that when new elements are added to the building, it must first be restored to its original condition before adding them [9,10].

Tam and Hao [11] showed four methods of adaptive reuse. The first entails modification to the facade while retaining the interior design, as long as the internal structures are in good condition. The second method involves adding new interior design elements while keeping the old exterior. This is the most common method used in heritage sites, as it allows for modern needs and improves the internal systems of the building. The third method includes additions to the existing external and internal structures to meet the needs of users. The last method of adaptive reuse keeps the building unchanged, while additions to its interior are installed to preserve the building’s qualities and values [1]. Rehabilitation and adaptive reuse are the policies followed in the Historic District of Jeddah, and they deal with the rehabilitation of buildings that are being given new functions. This policy is flexible, as it allows for the redesign of interior spaces while keeping the building facade unchanged [11].

Advantages of Reuse

The adaptive reuse of heritage buildings is a preservation method used to protect buildings from deterioration and to sustain their value [12,13,14,15]. In addition to extending the lifecycle of the building [5,7], it is also an incentive for creating and sustaining environmental, social, and economic values [5], which contributes to a stronger identity [13]. It is considered one of the most important strategies when dealing with heritage buildings and works to achieve a balance between preserving a building and enhancing its role in the urban environment [16]. In terms of environmental benefits, adaptive reuse saves energy and costs over new buildings, making it more sustainable [7,8,17]. It requires less energy and waste [18,19,20], protects buildings from destruction due to uncontrolled development [14], reduces construction, maintenance time, and costs [18], and reduces land consumption and urban degradation [21].

Some studies report that adaptive reuse increases tolerance and social cohesion among the surrounding communities [18]. Through accessibility and usability [7], the heritage buildings are appreciated locally and externally by current and future generations and by tourists. A building that accommodates modern needs and activities is better than one being unused [14]. Adaptive reuse revitalizes the building’s heritage features, giving them a new lease of life [19]. In addition to making use of community facilities, adaptive reuse enhances the usable facilities in the neighborhood [18], reviving the building’s values and enhancing its sense of belonging [16,22].

As an economic advantage, the reuse of heritage buildings opens up opportunities for new residential and commercial real estate [7], creating new opportunities for the surrounding population [22]. Snyder [8] asserts that if the structure of a building is well adapted to its new function, the economic advantages will come from the reduced cost of land purchase and construction, as well as the completion time of new construction. It also enhances the aesthetic appearance of the built environment, increases the demand for buildings [20], and improves local economic structures by expanding, integrating, and managing economic resources [18], thereby resulting in economic growth and effective cost management [21]. Figure 1 summarizes the advantages of reuse, as stated in previous literature and its benefits to individuals, society, and the environment.

Figure 1.

Advantages of adaptive reuse.

1.2. References and Charters for the Adaptive use of Buildings

References on adaptive reuse vary internationally, regionally, and locally, in the form of conferences or symposia. There are international references approved by the International Council on Antiquities and Sites that focus on the policies and requirements of the intervention. A number of principles and foundations are agreed upon and circulated at an international level or on a specific scale and region. For regional and local references, heritage preservation bodies issue and agree upon the policies of intervention in their respective determinants that are adopted and circulated according to the specifics of each state or region.

1.2.1. International Charters and Statements

Conservation policies for heritage buildings and antiquities vary. Some require preserving and protecting the buildings as they are, without any interference, while some require modifications. Among the intervention policies are conservation, restoration, rehabilitation, maintenance, air conditioning, and others. A number of international references emphasize the principles and policies of implementing these interventions, interspersed with a number of charters, such as the Athens Charter of 1931 AD, the Venice Charter of 1964 AD, and the Dubai Charter of 2004 AD (the first charter in the Arabic language for heritage buildings) [23]. The researchers focus on eliciting points that serve the concept of adaptive reuse, and the charters include various focal points. one of which is the end goal of intervention policies—to preserve buildings—as they are considered economic resources that contribute to meeting the needs of society and strengthening the identity and sustainability of cultural heritage. The researchers summarize the main points of the charters, and they propose to divide them into two axes: preservation and authenticity, and society and economy (see Figure 2).

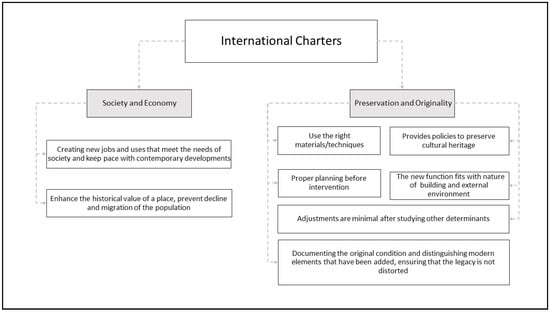

Figure 2.

Summary of international charters.

1.2.2. Mechanisms for Classifying Heritage Buildings

Requirements for reuse were confirmed in different countries. Hussein’s study divided the heritage buildings into three main types and permitted the modifications for each, according to their heritage importance, as stated in Law No. 144 on regulating the demolition of buildings and structures that are not dilapidated and preserving architectural heritage in Egypt. Category A buildings are not allowed to be modified except for restoration, and only minor changes are allowed. Category B buildings are allowed some internal modifications to make them suitable for reuse. Category C buildings are allowed to be radically modified inside, including the complete demolition of the building if needed, but the preservation of some or all of its external features may be necessary [15].

The Jeddah Municipality divided the classification of heritage buildings into three types, according to the role they played locally and regionally: first-class, second-class, and third-class buildings. The classification determines the proposed use of the building and the architectural treatments allowed for its exterior and interior design. Determining the proposed use should not contradict the choice of the function with the nature and privacy of the building, as the optimal function is determined on the basis of the general plan. The function selection for first-class buildings is based on a specific scope represented by governmental, administrative, educational, or cultural buildings. For the second and third-class buildings, function selection is according to a scope represented in an office, residential, hotel, or commercial building. The optimal choice in all classifications is subject to the authorities specifying permissible percentages [16].

Ali divided the techniques of reusing buildings into two grades. The first, known as Grade A, is the use of a building without any modifications or changes while keeping the spaces of the building as they are, and adapting them to suit its new use, or leaving the building as it is, a tourist shelter in its original condition. The second, Grade B, makes modifications to adapt the building to its new use. These are modifications of two types: external changes done to the outside of the building by adding, concealing, or modifying as needed, and internal alterations done to the inside of the building by addition or replacement, and so on [22].

The Saudi Commission for Tourism and Antiquities and the Ministry of Tourism currently classify all urban heritage sites and buildings and their areas into three grades: Category (A) for buildings and sites of high importance, Category (B) for buildings and sites of medium importance, and Category (C) for buildings and sites of little importance. These classifications include the building or site, antiquities and movable parts within (such as paint, windows, doors, and others), urban areas comprising several buildings, villages, cities, neighborhoods, all surrounding buildings and areas whose presence is included in the protection of the building, and, finally, the surrounding natural areas [24]. This classification was also approved according to the Antiquities, Museums, and Urban Heritage System by a royal decree that is in effect at the time of writing this [25].

1.2.3. Adaptive Reuse Methodologies

Choosing a new function for a building is difficult. This decision requires an analytical and scientific approach because random actions could harm the building’s originality and sustainability [4]. Pintossi et al. [26] suggested that the novel challenges identified hampering the adaptive reuse of cultural heritage are: The absence of participatory processes, implementation of participatory processes, lack of guidance for the adaptive reuse of cultural heritage, limitation of capacity, diversity of strategy documents, long operational phase, deficiency for financial resources, loss of knowledge and traditional skills, lack of integration among sources of information and population migration [26]. Therefore, this poses a major challenge to architects, civil engineers, and conservation professionals [6]. At the same time, it is considered a catalyst for innovation and creativity by designers, architects, and engineers to find unique solutions that combine originality with contemporary elements [7]. User participation in decision making is one of the most important issues in adaptive reuse projects [4]. However, the criteria for preserving heritage buildings are still not clear, because each building has its own conditions, making the methods of preservation different from other buildings [27]. Numerous studies have contributed to clarifying strategies and proposals for the evaluation and management of such sites. Moreover, the cultural heritage management criteria were developed based on axes of the cultural heritage context of sustainable tourism and its economic, urban, natural, and cultural–social environments [28].

Misirlisoy and Gunce [4] mentioned that there is a lack of appropriate plans and strategies in the management of sustainable heritage, as the buildings must achieve financial returns that cover their future maintenance and rehabilitation. The main objective is to preserve the originality of the building. However, the building’s economic sustainability is also important to the future of its heritage. The decision-making process goes through five steps: (1) organize the active parties in the reuse process; (2) analyze the building and its physical characteristics, its original use, and the needs of the region; (3) determine the interventions applicable to the reuse of the building; (4) determine the characteristics and possibilities of the building’s adaptive use; and (5) decide from three options whether to retain the original function of the building or mix its use by retaining its original function with the addition of new functions to ensure the continuity of the building or provide it with a new use that is completely different from the original. One of the biggest mistakes in the adaptive reuse of heritage buildings is the maintenance of the entire building and the identification of the new function resulting in unnecessary interventions and inappropriate additions [4].

Conejos et al. [29] confirmed the challenges facing adaptive reuse projects, particularly regarding compliance with laws, regulations, and design requirements in the current era. Seven principles are followed when adapting buildings: (1) identifying and understanding the importance of the heritage fabric; (2) determining the appropriateness, importance, and compatibility of the new function with the building; (3) determining the change that has the least impact on the importance of the place; (4) ensuring that the principle of reflection of its origin is applied to preserve the place in the future; (5) preserving the link between the place and the opinions that contribute to its importance; (6) establishing a sustainable management of the place and its feasibility, including funding and heritage agreements to preserve the buildings; and (7) publishing and translating the importance of a heritage place is important when implementing a building adaptation project [29].

Another determining factor to the extent of the success or failure of the re-employment schemes of heritage buildings at the end of the process is their ability to achieve four main requirements: (1) to preserve the building’s architectural and symbolic values represented by architectural details, decorations, interior design, and distribution of spaces; (2) to preserve the general heritage atmosphere; (3) to provide the building with a new function that matches its heritage value; and (4) to ensure that modern requirements are met. This is achieved by good design of the interior spaces and the study of the site and its social environment [15]. From the literature, the elements of adaptive reuse assessment can be categorized into several elements, as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Classification of adaptive reuse assessment items.

2. Materials and Methods

This study followed a qualitative approach, which is defined as describing and collecting information and facts about a specific event, phenomenon, or thing, in addition to reporting its status as it is in reality [30]. It was conducted on three levels:

- First level: Data were collected through a literature survey and content analysis to produce a general model to serve as the concept of reuse internationally and locally, such as in the Athens Charter of 1931, the Venice Charter of 1964, the Declaration of Amsterdam of 1975, the Burra Charter of 1981, the Tlaxcala Declaration of 1982, the Appleton Charter of 1983, the Washington Charter of 1987, the Charter for the Protection and Management of the Archaeological Heritage of 1990, Principles for the Preservation of Historic Timber Structures of 1999, the Zimbabwe Charter of 2003, the New Zealand Charter for the Conservation of Places of Cultural Heritage Value of 2010, the Valletta Principles for the Safeguarding and Management of Historic Cities, Towns, and Urban Areas of 2011, and the Salalah Guidelines for the Management of Public Archaeological Sites of 2017.

- Second level: The general model will be linked to the determinants of the historical Jeddah region to extract its evaluation model.

- Third level: The model will be presented to a number of specialists in architecture and design in the historical Jeddah area to assess the appropriateness and comprehensiveness of the proposed model.

This study was conducted in historic Jeddah, the Makkah Al Mukarramah region, in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, during 2020–2021 AD.

2.1. Study Sample

Five specialists, including architects and designers, participated in the study in the historical area of Jeddah, according to the following criteria:

- At least five years of experience in the field of architectural heritage;

- Sufficient diversity among the academics and practitioners in the field of architecture and design for heritage buildings;

- Their area of specialization in heritage buildings was in the Jeddah region (as each region has its own determinants and its own style of construction).

2.2. Case Study (Historic Jeddah District)

Introduction to the City of Jeddah

Historic Jeddah is considered a cultural and architectural heritage that is part of the identity of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia [1]. With the passage of time, the importance of Jeddah increased, and it became one of the largest cities in the Kingdom. Historic Jeddah was inscribed on the World Heritage List on 21 June 2014, with its architectural features adding to its historical value, such as the use of prospective stone and wood in the construction of the bearing walls, and the old buildings’ innovative and artistic solutions to adapt to the harsh climatic conditions of the region (see Figure 4) [1]. For example, the roofs perform many functions at the same time: providing privacy, purifying the air, and providing thermal comfort. The high rises of these buildings face the north and west winds. The aesthetic element that decorates the facades and architectural design is characterized by open spaces and zigzag structures that offer protection from sunlight [16]. The uses of these buildings over time varied; however, over time their use was subjected to many changes that led to unplanned technical repairs and restoration operations. It is necessary to study their future use to propose appropriate repair and restoration solutions that will help restore prosperity to the area and buildings without repeating previous mistakes [31].

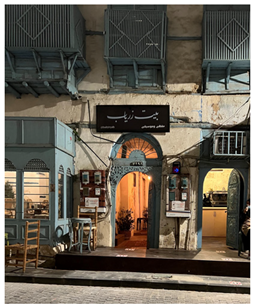

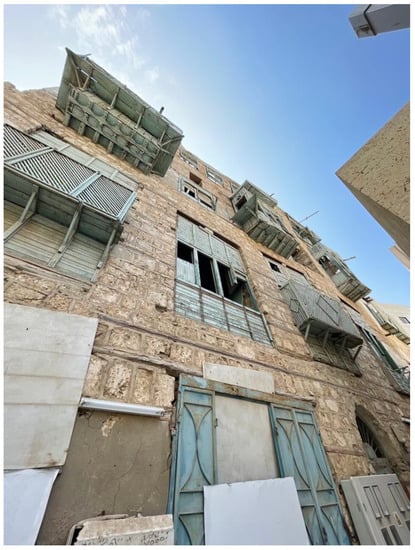

Figure 4.

Facade of one of Jeddah’s historic houses.

The urban fabric in the historical area of Jeddah is characterized by the density of interconnected architectural blocks interspersed with narrow and winding roads and alleys, which provide shade for pedestrians and mitigate the severity of the weather [32]. The heights of the buildings vary due to their multiple floors [32], with some reaching 30 m [33]. The facades are characterized by the abundance and width of the openings on the outside, covered with Rowshan that is made of wood and decorated [16,32]. The construction relied on local materials, such as coral limestone extracted from Lake Al-Arbaeen and modified using hand tools to be placed in the appropriate locations according to size. The use of wooden supports or spacers prevents wall cracks that could result from the uneven subsidence of the building as a result of weak soil bearing and high surface water levels [32]. The ceilings are made of wooden panels resting on squares of wood, with a layer of coral limestone placed on top, followed by a layer of sand. The external walls of the dwellings are covered with a layer of lime plaster (to protect the building stones from erosion due to high humidity) and are painted with a layer of white or light-colored (such as sky blue) paint. The rafters were installed around the openings, and the wooden screens are on the openings of the dwelling and around the roof walls [30,34]. In one of Muhammad Al-Batonuni’s trips, he found that Jeddah owns about 3500 houses built of water stone. This stone is characterized by lightness, durability and flammability [34].

The heritage buildings in historic Jeddah were categorized according to the Matthew classification followed by the area [16] (see Figure 5). This classification is based on the role the building played at the local and regional levels, the events it experienced, and the uniqueness of its architecture. Six categories of heritage buildings were identified: Categories A, B, and C require restoration, while buildings of Categories D, E, and F are allowed reconstruction [16]. This means that adaptive reuse will be applied to the following three categories:

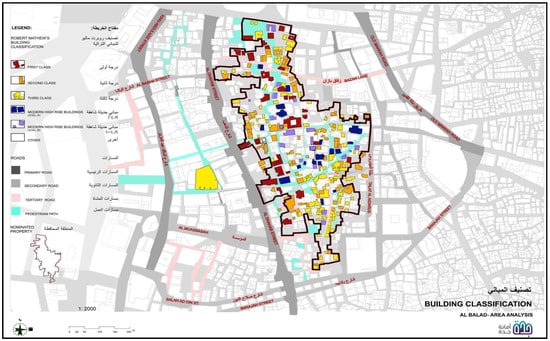

Figure 5.

Matthew classification used in the historical area of Jeddah [16].

- Category A: There are no structural or superficial damages to the building.

- Category B: There are objective structural and non-structural damages, but the building is stable, and its structure needs to be maintained and restored sufficiently to ensure stability.

- Category C: There are serious structural damages that affect the integrity of the building but do not prevent its restoration and rehabilitation to avoid its collapse.

As for adaptive reuse in Jeddah, there are already some buildings that have been reused (Table 1).

Table 1.

Examples of some reuse projects in Jeddah.

Through the above, a model was created to assess the quality of the adaptive reuse of historical buildings and ensure that the buildings’ integrity and originality are preserved over time. Permits are needed for the reuse process, but if the building is not periodically reviewed following correct standards, it may lose its originality, which defeats the purpose of employment. By analyzing the literature on standards and charters for reuse and requirements related to buildings in the historical Jeddah region, according to the technical guide for restoration and the Jeddah Municipality’s requirements, the model was built on the following two axes:

- The first axis: Basic information about the building to identify its background—this consists of seven basic elements.

- The second axis: Elements and criteria for reuse, restoration, and repair, consisting of seven basic elements: suitability of the new function, architectural design (facades, openings, Rowshan (i.e., raised wood covering for windows and external openings), and building and finishing materials), interior design (internal distribution, furniture, lighting, ventilation, and aesthetic and decorative aspects), security and safety, legal aspects, economic aspects, and repair and restoration as per the technical guide for restoration and the Jeddah Municipality.

3. Results

To ensure the effectiveness of the model, it was presented to five experienced arbitrators in heritage buildings in the historic Jeddah region. The participants were coded to preserve their confidentiality. They have at least eight years of experience in the field of heritage and restoration in the historical region.

3.1. The First Axis: Basic Information of the Building

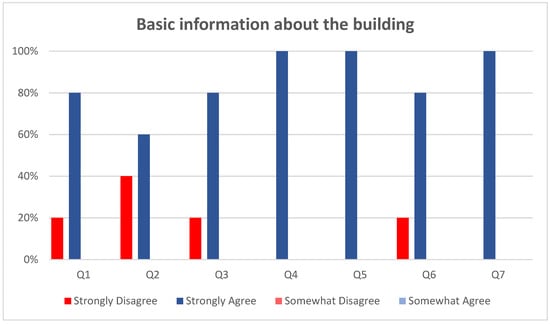

Participants’ answers were coded as strongly agree (+2), somewhat agree (+1), strongly disagree (−2), and somewhat disagree (−1) for easy reading of the results. The first axis consists of basic information related to the building in terms of ownership, function, age, location, and classification from the competent authorities, as shown in Table 2. The results are shown in Figure 6.

Table 2.

Building basic information questions.

Figure 6.

Results of basic information about the building.

In the previous table, the percentage of participants’ agreement with the inclusion of basic information was high, as they agreed 100% on Questions 4, 5, and 7. As for Questions 1, 3, and 6, three out of five participants agreed on the importance of having this information. For Question 2, mutual agreement was only at 60%. Participant A1 proposed adding the following questions: Is the building occupied or abandoned? Has the building been reused, and for what purpose? Has the building been professionally repaired? Participant A3 suggested adding the age of the building, title deed information, building permit information, plan information, dimensions, neighbors, and area. Participant A5 proposed adding the number of floors and the total area.

3.2. Second Axis: Elements and Criteria for Reuse, Restoration, and Repair

This axis includes seven elements: function adequacy and architectural design, interior environment, application of security and safety standards, legal aspects, economic aspects, and non-material aspects related to achieving the goals of repair and restoration of heritage buildings.

3.2.1. The First Element: Suitability of the New Function

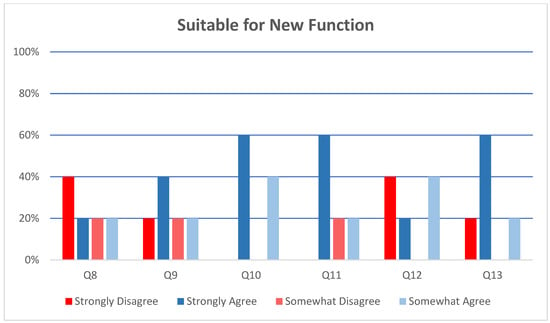

This element consists of a set of questions related to the function chosen for the building, with respect to the building’s history, durability, and accessibility, as shown in Table 3. The results are shown in Figure 7.

Table 3.

Questions related to the suitability of the new function.

Figure 7.

Results of suitable for new function.

The agreement of the participants with the questions in this element ranged from complete agreement to agreement to some extent. The participants saw a need to add or reformulate the questions. Question 8 caused confusion, and 40% of the participants did not agree with it. One participant thought the evaluation was for heritage buildings only and did not include modern buildings. This caused the participants to propose reformulating the question. Participant A1 suggested rephrasing it to “Is the building included in the list of heritage buildings of the Municipality/Ministry of Culture?” Participant A2 also suggested reformulation because he thought that the erected buildings in the heritage area were heritage buildings only. Meanwhile, participant A4 suggested, “The classification of heritage buildings was mentioned in the previous axis, so the question can be dispensed with or replaced with this question: Is the building modern?”

In addition, participant A5 proposed this question: “Is the building site located within the commercial hubs?” This would mean that the site is suitable for commercial activity. The rest emphasized the paraphrasing of the questions, such as the suggestion of participant A1 regarding Question 9: “Is the building classified as a category of buildings (A, B, C) according to the Jeddah Municipality guide for heritage buildings?” While some participants suggested dividing Question 12 into two questions, participant A4 proposed “Is the new function suitable for urban planning?” and “Is it easy to access the site?” of the building. For Question 13, participant A2 suggested that the external paths must be separated from the internal movement.

3.2.2. The Second Element: Architectural Design (Facades, Openings, Rowshan, Building and Finishing Materials)

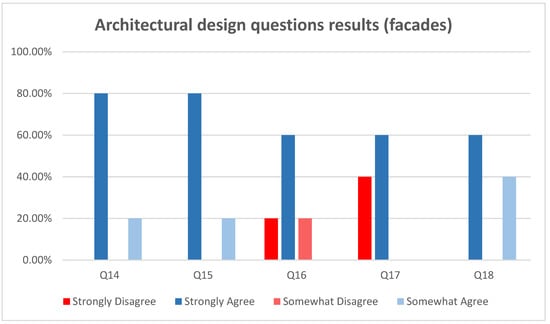

This element consists of sub-elements related to building facades, openings, and materials used in construction and finishing. It investigated whether the properties of the materials used were compatible with those of the original materials of the building [10], if the new element was distinct from the old, and if the new function was suitable for the building’s structural durability [9,10]. The questions related to the facade investigated additions made to it and its possible effects on the buildings and its external surroundings, as shown in Table 4. The results are shown in Figure 8.

Table 4.

Architectural design questions (facades).

Figure 8.

Results of the questions on facades.

The majority of participants agreed with the questions of this axis: For Questions 14 and 15, 80% strongly agreed and 20% agreed, and for Questions 16–18, the majority strongly agreed. Participant A2 agreed with the questions, but suggested reformulating them, adding, “Note that the change in the facades is not allowed in the classified heritage buildings, but some internal changes are allowed”. For Questions 15 and 16, the participants suggested including the availability of documents, especially for comparison in the event of changes to the building. Participant A3 added that it is preferable to attach the documents to make the differences clear. In Question 17, the percentage of disagreement was at 40%, less than half the total responses, and therefore the proposal to cancel it was not appropriate.

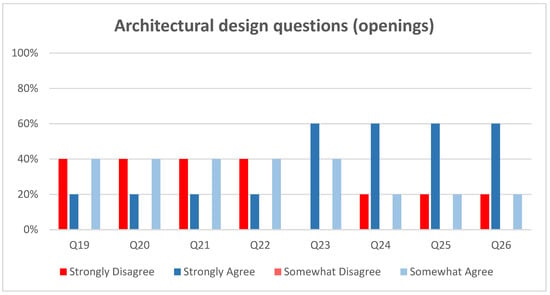

The sub-element that deals with the openings is shown in Table 5. The results are shown in Figure 9, which consists of the changes related to the openings in terms of design, area, material, color, or new additions.

Table 5.

Architectural design questions (openings).

Figure 9.

Results of the questions on openings.

For Questions 19–22, there is an equal percentage of those who strongly disagreed and those who somewhat agreed. For Questions 23–26, 60% strongly agreed. However, there remained some who strongly disagreed. The formulation of the questions may have led to a lack of clarity for the person conducting the assessment. As for the questions dealing with changes to openings, doors, and arches, the opinion of participant A2 was that “No changes should be made to heritage buildings”. This supports the importance of including these questions in the checklist to ensure the authenticity of the building.

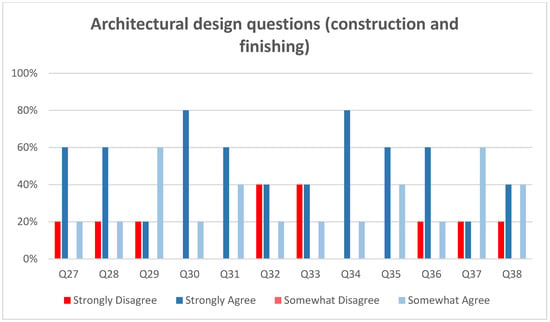

The third sub-component deals with building and finishing materials and their relationship with the strength and safety of the building and their suitability to the original materials, as shown in Table 6. The results are shown in Figure 10.

Table 6.

Architectural design questions (construction and finishing).

Figure 10.

Results of the questions on construction and finishing.

The majority of the participants agreed with the questions. Those who strongly agreed had the highest percentage, 80%, with regard to protecting the wood used in Rowshan with insulating materials and additives that would not affect the originality of the building. Those who agreed with Questions 35 and 36 totaled 60%. As for Questions 28 and 31, participant A2 commented, “The building materials in heritage buildings are known and should not be touched. It must be clarified in the question that what is meant by materials are building repair materials, which should be addressed by evaluation”. For Question 29, participant A2 said that the question includes two elements that must be separated into two for the evaluation to be accurate. A total of 80% agreed with Question 38. Participant A5 suggested adding “except for wooden beams”, which must not be touched. Meanwhile, 60% agreed with Questions 32 and 33. The lowest percentage for the strongly agree option was 20% for Question 37, but 60% agreed to some extent that this may be because some thought that the current legislative body responsible for material permits is not the Municipality, but an entity linked to the Ministry of Culture and Heritage Management. Therefore, the question should be reformulated.

3.2.3. The Third Element: Interior Design

Interior design includes several sub-elements: internal distribution, furniture, lighting, ventilation, and aesthetics and decoration.

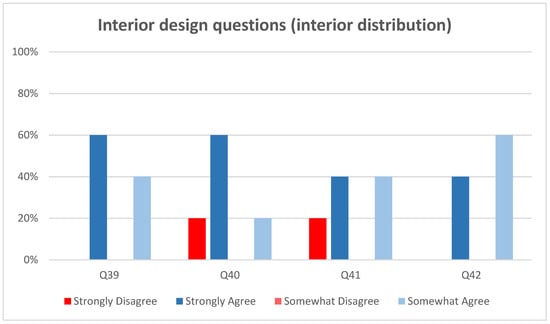

Internal distribution deals with the correct method of using internal spaces and paths of movement, as well as making additions that do not affect the originality and durability of the building. The modifications made to the interior design should be minimal to preserve the originality of the building [15] and propose the functional use of spatial planning [17,21], as well as for aesthetic and symbolic values [15]. The results are shown in Table 7 and Figure 11.

Table 7.

Interior design questions (interior distribution).

Figure 11.

Results of the questions on interior distribution.

It is evident that between 80% and 100% of the participants agreed with the questions. Some participants, however, considered it necessary to reformulate a question or suggested adding a note to a question to provide more detail. The 20% strongly disagree option was chosen by participant A2. Since Question 40 asks if the original spaces have been divided, participant A2 suggested eliminating Question 41, probably due to its wording. There must be no additions to the original spaces, and the possible extent of the original partition of the building should be considered so that the modification is within the partition boundary of the vacuum itself without any additions. One participant, A4, also suggested wording the same question as, “Have new spaces been added that have affected the construction elements of the building?”

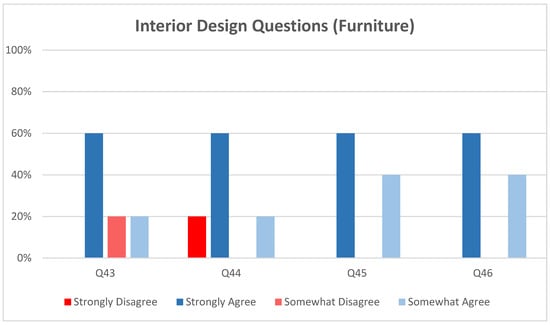

The furniture element addressed compatibility with the basic nature and structure of the building, factoring in its design and the combination of authenticity and contemporary style. The interior design questions related to furniture are shown in Table 8 and Figure 12.

Table 8.

Interior design questions (furniture).

Figure 12.

Results of the questions on furniture.

In Questions 45–46, 60% of participants strongly agreed, and 40% somewhat agreed. For Questions 43 and 44, there was an equal percentage between those who strongly disagreed and those who somewhat disagreed. Participants agreed with the questions but suggested adding a note or reformulating the question. For example, participant A4 considered reformulating Question 46 to “Has the quality of furniture led to construction problems for the building?” Participant A1 disagreed to some extent with Questions 43 and 44, stating, “This item does not fall within the criteria for evaluating the reuse of historical buildings”. However, the researchers believe that their presence must be considered with the design of the building, as it considers the historical aspect of the building and its nature, in addition to its relevance to the new activity to preserve the originality and continuity of the building.

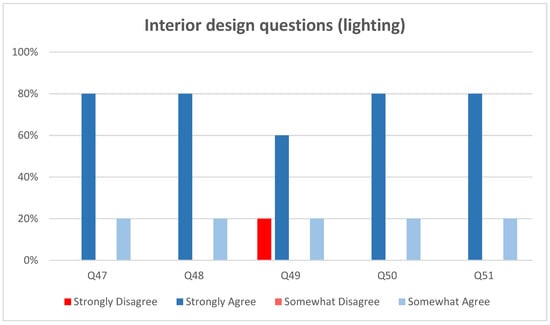

Looking at lighting, the element includes items based on the extent to which the lighting and its quantity are proportional to the nature and current activity of the building, and the impact of its extensions on the security and safety of the building, as shown in Table 9 with the results listed in Figure 13.

Table 9.

Interior design questions (lighting).

Figure 13.

Results for the questions on lighting.

Most participants agreed that lighting is an important element. Question 49 was the only one to receive a “strongly disagree” response, which came from participant A1, who said, “It is not necessary for this item to be included in the criteria for reuse of heritage buildings”. Participant A5 also proposed for Question 48 to ask, “Is there natural light and a balance between nature and industry, considering the trends of the building and the movement of the sun?” and “Have the distinction of extensions been taken into account so as to make it easier to distinguish them?”

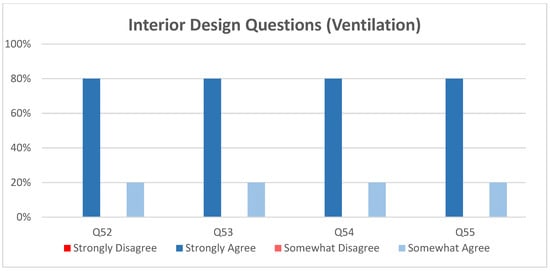

Ventilation covers the relevance of natural and industrial ventilation to new activity and the extent to which it affects the authenticity and tolerance of the building, as shown in Table 10. The results are shown in Figure 14.

Table 10.

Interior design questions (ventilation).

Figure 14.

Results for the questions on ventilation.

The majority agreed with all ventilation-related questions, with 80% strongly agreeing and 20% somewhat agreeing. Arbitrator A3 somewhat agreed, suggesting that a detail box be added to each question.

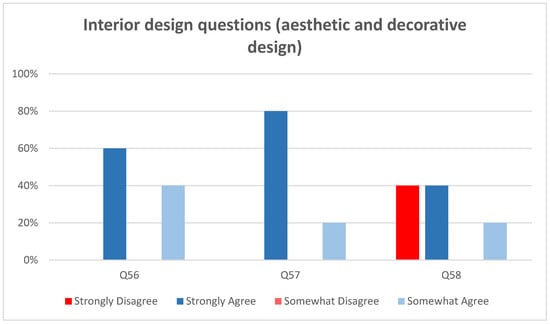

The aesthetic and decorative aspect was also addressed, as shown in Table 11 and Figure 15. The items included the decoration and materials used and investigated if these affected the originality of the building.

Table 11.

Interior design questions (aesthetic and decorative design).

Figure 15.

Results for the questions on aesthetics and decorations.

The majority of the participants strongly agreed with Question 56, with participant A3 suggesting adding a box with further detail. For Question 57, 80% strongly agreed and 20% somewhat agreed, which was participant A3′s choice, for the same reason as the previous question. The lowest percentage of agreement was for Question 58 at 60%, and 40% did not agree with the question at all. Participant A3 had the same reason, citing the addition of a box for detail. Participant A1 justified this choice of not agreeing at all by saying, “It is not necessary to enter this item in the process of evaluating the reuse of heritage buildings”.

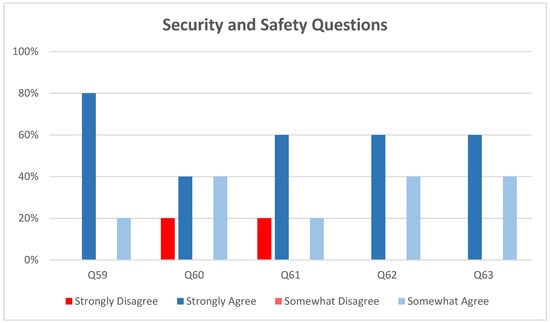

3.2.4. The Fourth Element: Security and Safety

This element included items related to security and safety, as shown in Table 12 and Figure 16, such as the application of the requirements of the authorities concerned with the security and safety of buildings, appropriate paths for emergency evacuation, and the presence of fire extinguishers and emergency exits.

Table 12.

Security and safety questions.

Figure 16.

Results of the questions on security and safety.

The majority of participants strongly agreed with Question 59, with 20% choosing the somewhat agree option. For Question 62, participant A2 suggested that the question should be, “Is there a system for detection, alarm, and fire extinguishing?” The researchers agreed with the proposed wording—the item must include the entire system of extinguishing, detecting, and others. Participant A5 also suggested adding the question, “Are the tools for the fire system kept in a suitable place that does not affect the originality and heritage of the building?” This confirms what the researchers discussed, which was that any addition to the building cannot affect its originality and value.

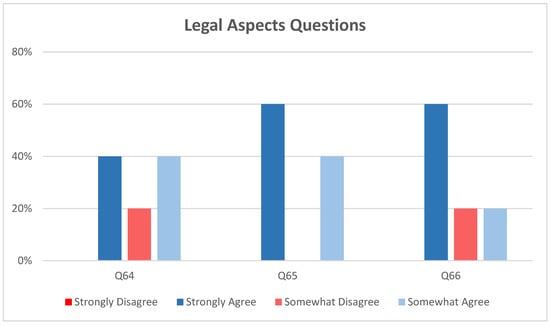

3.2.5. The Fifth Element: Legal Aspects

This element includes the legal aspects related to the functional proposals for the reused building, according to the proposals of the responsible authorities. This is to ensure that the evidence (in the Technical Guide to Jeddah Historic District) for preserving and restoring heritage buildings is followed and that the suitability of the proposed use abides by the proposals of the Jeddah Municipality [16], as shown in Table 13 and Figure 17.

Table 13.

Legal aspects questions.

Figure 17.

Results for the questions on legal aspects.

There are clear differences in opinions on these questions, as 80% agreed with Question 64. The “somewhat agree” choice may be attributed to participant A2, who noted that it needs to be reformulated, and to participant A3, who suggested adding a box for detail and allowing for answers other than yes or no. Participant A4 also believed that “there may be an updated classification of buildings and their uses”. For Question 65, all participants agreed, with participant A3 only somewhat agreeing due to his suggestion to add details to the question, as previously noted. Participant A4 suggested replacing the municipality with the current responsible or legislative body, because the municipality no longer has all the power over the historical area. For Question 66, 60% strongly agreed, 20% somewhat agreed, and 20% somewhat disagreed. The guide should be regularly updated, as there may be new requirements and evidence issued by the Ministry of Culture.

3.2.6. The Sixth Element: Economic Aspects

Economic feasibility and self-financing are some of the objectives of the adaptive reuse of buildings [15]. The sixth element includes achieving economic feasibility and stimulating commercial traffic, as shown in Table 14 and Figure 18.

Table 14.

Economic aspects questions.

Figure 18.

Results for the questions on economic aspects.

Results show that the participants agreed with all questions by 80%. Participant A1 strongly disagreed, saying for Question 67, “This item belongs to the investor and is not included under the architectural evaluation”. For Question 68, participant A1 stated, “It is difficult to evaluate this item because it requires a comprehensive demographic and economic study at the level of the region”. For Question 69, participant A1 noted, “The outcome of this question cannot be predicted and there may be other influences on the project that are not related to the architectural components”. For Question 70, participant A1 asked, “How is this evaluation conducted?” This may be because the assessment of adaptive reuse is predominantly architectural. However, researchers consider that the evaluation process is based on the knowledge that all material and non-material aspects of the project should be included as a precise model.

3.2.7. The Seventh Element: Repair and Restoration of Heritage Buildings

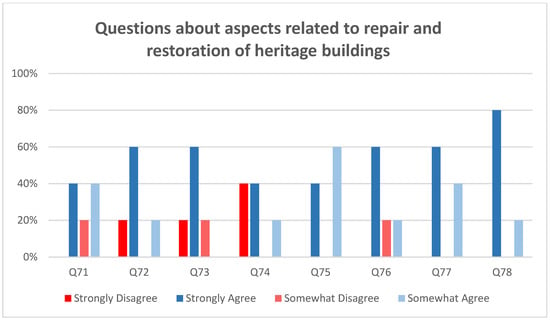

This element touched on the non-physical aspects of heritage in addition to improving the environmental conditions of the area and the suitability of the proposed new functions to the requirements and needs of the times. It included questions on the balance between tradition and modernity, the requirements of the current generation [15], the compatibility of the proposed use with the beliefs, values, and interests of the community, and the promotion of community awareness and cohesion [17]. This is presented in Table 15 and Figure 19.

Table 15.

Questions about aspects related to repair and restoration of heritage buildings.

Figure 19.

Results for the questions on repair and restoration of heritage buildings.

The diversity of the “strongly agree” responses was between 60% and 80% for these questions. For Question 71, arbitrators noted that the question was subjective. Participant A1 believed that Question 73 was unrealistic, and participant A2 believed Question 74 should be eliminated.

4. Discussion

The data from the arbitration of specialists on the proposed model for the evaluation of heritage buildings in historic Jeddah show that the results were positive for most of the questions, especially those related to the physical aspects of the building. Participants felt that the elements could be measured and identified through the model when the building is periodically evaluated by specialists and stakeholders, and therefore the model would be an integral part of the detailed measurable documentation of the building. It would also be useful in determining defective aspects contained in the model. To make it easier for the evaluator to know the location of the defect in a particular element, it is suggested that a special field for notes be added for each element. The specialists suggested that some elements be reformulated for clarity, and elements be added and clarified in the final model.

In the first axis relating to the basic information of the building, the percentage of agreement was high, with suggestions to add choices for the building’s new function. For the second axis relating to criteria for reuse, restoration, and repair, the specialists agreed with the first element on the suitability of the new function, with a proposed reformulation of some questions and the revision of Question 8, as this evaluation is for heritage buildings only and not for new buildings. In addition, there were some proposals to delete certain questions because of their inappropriateness. The rest of the proposals were about reformulating and separating some of the questions into parts, such as those related to ease of access, urban planning, and internal and external movement paths.

The second element covers the external features of the building (facades, openings, Rowshan, materials, and finishing). The proposed additions of some participants for changing the facades are not allowed in the classified heritage buildings, as only some internal changes are permitted. However, the researchers elected to keep this question, as the model was developed to ensure that the project does not affect the facade of the building. Question 17 was deleted because it was not suitable. It is clear in the element regarding openings (doorways) that the questions were all appropriate—it is not necessary to change the openings, doors, and arches, because they represent originality. With regard to the finishing materials, most of the participants agreed with the questions posed in the form, also proposing additional items, such as switching building materials in heritage buildings to repair materials. Moreover, except for the takalil “wooden beam between the row of stones and the other, in the wall to distribute the loads in the building” in Question 38, it was recommended by the participants not to touch wooden beams when applying plaster to the facade.

The interior design covers internal distribution, furniture, lighting, ventilation, and the aesthetic and decorative design. As for the internal distribution, the participants recommended to reformulate the questions while preserving the meaning. For the furniture component, one of the participants mentioned that the item does not fall within the criteria for evaluating the reuse of historical buildings. However, the researchers believe that it should be included in the list, as the size and shape of the pieces of furniture can have a positive or negative impact on the building. Regarding the lighting element, the majority of the participants agreed with the items, although some suggested a reformulation of the questions and clarification of some points, such as factoring in the direction of the building, the movement of the sun, or the amount of natural lighting in Question 48. Some also suggested adding questions, such as whether a balance was achieved between the use of natural and artificial lighting, and whether it is easy to distinguish the extensions. The new elements in the heritage buildings must be distinguishable, as confirmed by international conventions on preserving heritage buildings. As for the ventilation component, all participants agreed with the questions without any suggestions for wording, although a question was added on distinguishing extensions, as is the case in lighting. The researchers see the necessity of the question here, as the item needs to be included in the evaluation process. As for the decorative and aesthetic aspect, the majority of arbitrators agreed with the questions; however, two out of five participants did not agree with Question 58 on combining originality and contemporary design, with one of them justifying that it is not necessary to address this item in the process of evaluating the reuse of buildings. The researchers, however, see the necessity of the question, as reuse is based on meeting contemporary needs while being careful not to prejudice the originality of the building.

As for the security and safety component, most participants agreed with the questions, but some suggested that they should be reformulated while retaining their meaning.

When we asked about the legal aspect, the participants agreed with the questions, but some suggested reformulating them and adding a box for detail, with the option for an answer other than yes or no. One of them stressed the need to verify the proposed classifications of existing buildings, as there may be updated classifications, at which point the researchers communicated that this current classification is currently in effect. The Ministry of Culture is updating it, but this is yet to be completed.

For the economic aspect, the majority of participants agreed with the questions, but one believed that they should not be included in the architectural assessment process, as they are difficult to measure. However, the researchers believe these should be included, as the economic feasibility of a project is one of the objectives of adaptive reuse, and the evaluation process is based on knowledge of various architectural and non-architectural aspects to ensure the preservation and authenticity of these buildings, which is what the study sought to achieve.

Finally, for the non-material aspects of the evaluation, there were some proposals to amend or delete some of the questions, which may be due to the difficulty of evaluating the non-material aspects by a non-specialist. The researchers see the necessity of its existence; thus, the evaluator must be experienced in the field of heritage and architecture and with the materials and other aspects when writing their opinion in a specialized and accurate manner, based on certain criteria, for the model to achieve its objectives effectively. Table 16 shows the finalized model.

Table 16.

Final model for evaluation of the adaptive reuse of historical buildings.

Through this table, the researchers see that the model can be used in evaluating other heritage buildings while modifying it in line with the nature of the building. The researchers will apply this model to the historical buildings of Jeddah in future studies. However, this study was sufficient to generalize results on a larger level.

5. Conclusions

Heritage buildings have physical and moral value, and their authenticity and identity must not be compromised. The intervention policies for these buildings vary, one of which, the adaptive reuse of buildings, was the focus of this study. Adapting the building for new use must be in accordance with certain regulations and requirements that must be considered in the decision-making process before choosing a function for a heritage building. There are also some standards and requirements that must be observed throughout the period of use of the building to ensure that its originality and sustainability are not compromised. There must be periodic evaluations that are included in the heritage management process of the building by the concerned authorities. This is the goal of developing an evaluation model for heritage buildings: to contribute to the periodic evaluation process for reused buildings, to ensure the commitment of stakeholders, from designers to contractors or owners of the reused project, and to ensure the application of international and local standards in accordance with the proposed model. The researchers suggest that the work of specialized studies be in accordance with each region, with the possibility of generalizing the main axes of the model and the general criteria it includes, such as the element of basic information for the building, aesthetic and decorative aspects, economic aspects, and interior design. The legal aspects and architectural design are governed by many determinants of the region itself, from the requirements of restoration to the use proposed by the concerned authorities for the same area. Therefore, the model can be developed to conform to a specific area outside historic Jeddah, should the authorities desire to apply it. In addition, the updated evidence of the region, if any, should be taken into consideration and reviewed periodically to ensure the comprehensiveness and effectiveness of the model.

This study recommends that the person in charge of the evaluation process be a specialist in architecture, design, and heritage.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.A.A. and A.A.A.; methodology, R.A.A. and A.A.A.; validation, R.A.A., A.A.A. and N.A.G.; formal analysis, R.A.A., A.A.A. and N.A.G.; investigation, R.A.A.; resources, R.A.A.; data curation, R.A.A.; writing—original draft preparation, R.A.A.; writing—review and editing, A.A.A. and N.A.G.; visualization, R.A.A.; supervision, A.A.A. and N.A.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- UNESCO. Historic Jeddah, the Gate to Makkah. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/1361/ (accessed on 4 September 2021).

- Ministry of Tourism. Tourism Investment. Available online: https://mt.gov.sa/TourismInvestment/Pages/TourismInvestment.aspx (accessed on 4 September 2021).

- Al-Ghamdi, S.A. Building to Subsist: The Concept of Adaptive Reuse of Buildings in Saudi Arabia. 2011. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/11969898/ (accessed on 18 March 2022).

- Misirlisoy, D.; Gunce, K. Adaptive reuse strategies for heritage buildings: A holistic approach. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2016, 26, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Othman, A.A.E.; Heba, E. Adaptive reuse: An innovative approach for generating sustainable values for historic buildings in developing countries. Organ. Technol. Manag. Constr. Int. J. 2018, 10, 1704–1718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lečić, N.; Vasilevska, L. Adaptive reuse in the function of cultural heritage revitalization. In Proceedings of the National Heritage Foundation Conference, Niš, Serbia, 30 August–1 September 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Environment and Heritage (DEH). Adaptive Reuse: Preserving Our Past, Building Our Future. Available online: https://www.environment.gov.au/system/files/resources/3845f27a-ad2c-4d40-8827-18c643c7adcd/files/adaptive-reuse.pdf (accessed on 4 September 2021).

- Snyder, G.H. Sustainability through Adaptive Reuse: The Conversion of Industrial Building. Master’s Thesis, University of Cincinnati, Cincinnati, OH, USA, March 2005. [Google Scholar]

- ICOMOS. Burra Charter Archival Documents: Australia ICOMOS. Available online: https://australia.icomos.org/publications/burra-charter-practice-notes/burra-charter-archival-documents/#BCOLDER (accessed on 15 September 2021).

- ICOMOS. Principles for the Analysis, Conservation and Structural Restoration of Architectural Heritage (Zimbabwe Charter). Available online: https://www.icomos.org/charters/structures_e.pdf (accessed on 30 September 2021).

- Tam, V.W.; Hao, J.J. Adaptive reuse in sustainable development. Int. J. Constr. Manag. 2019, 19, 509–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazdani Mehr, S.; Wilkinson, S.A. Model for assessing adaptability in heritage building. Int. J. Conserv. Sci. 2021, 12, 87–104. [Google Scholar]

- Djebbour, I.; Biara, R.W. The challenge of adaptive reuse towards the sustainability of heritage buildings. Int. J. Conserv. Sci. 2020, 11, 519–530. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, Z.M.; Zawawi, R.; Myeda, N.E.; Mohamad, N. Adaptive reuse of historical buildings: Service quality measurement of Kuala Lumpur museums. Int. J. Build. Pathol. 2019, 37, 54–68. [Google Scholar]

- Hussein, F.A.M. Design criteria for adaptive reuse of heritage buildings to achieve the principle of sustainability (Al Ghouri Group Case Study). J. Archit. Arts Humanist. Sci. 2019, 4, 312–335. [Google Scholar]

- Jeddah Municipality. Guide to the Requirements and Construction System of Historic Jeddah. Available online: https://www.jeddah.gov.sa/Business/LocalPlanning/HistoricalJeddah/index.php (accessed on 30 September 2021).

- Shady, A. Rehabilitation of heritage buildings and their effects on the sustainability of conservation operations, a case study of the cities of (Fowa and Al-Qusayr). J. Al Azhar Univ. Eng. Sect. 2016, 11, 687–697. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C.S.; Chiu, Y.H.; Tsai, L. Evaluating the adaptive reuse of historic buildings through multicriteria decision-making. Habitat Int. 2018, 81, 12–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conejos, S.; Langston, C.; Smith, J. Improving the implementation of adaptive reuse strategies for historic buildings. In Proceedings of the International Forum of Studies Titled SAVE HERITAGE: Safeguard Architectural, Visual, Environmental Heritage, Capri, Italy, 9–11 June 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Bullen, P.A. Adaptive reuse and sustainability of commercial buildings. Facilities 2007, 25, 20–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulameer, Z.A.; Abbas, S.S. Adaptive reuse as an approach to sustainability. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2020, 881, 012010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A. Evaluation of Alternatives in Relation to Data in the Reuse of Archaeological Buildings: A Scientific Evaluation Study in Restoration and Maintenance, Applied to One of the Archaeological Buildings in Cairo. Master’s Thesis, Cairo University, Cairo, Egypt, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Dihnah, A. Foundations and Controls for the Rehabilitation of Historical Buildings in the Old City of Aleppo. Master’s Thesis, University of Aleppo, Aleppo, Syria, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- The General Authority for Tourism and Antiquities. Antiquities, Museums and Urban Heritage System. Available online: https://mt.gov.sa/ebooks/Documents/Others/P14/AntiqMuesHeirRegulation/AntiqMuesHeirRegulation.pdf (accessed on 7 October 2021).

- Experts Committee in the Council of Ministers. Antiquities, Museums and Urban Heritage Law. Available online: https://laws.boe.gov.sa/BoeLaws/Laws/LawDetails/a7d4493b-7c03-4c2d-b3c6-a9a700f275cd/1 (accessed on 7 October 2021).

- Pintossi, N.; Ikiz Kaya, D.; Pereira Roders, A. Assessing cultural heritage adaptive reuse practices: Multi-scale challenges and solutions in Rijeka. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robles, L.G. A methodological approach towards conservation. Conserv. Manag. Archaeol. Sites 2010, 12, 146–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awaad Gomaa Awaad, A. Cultural heritage management and sustainable tourism in historical cities (Case study: Durrat Al Nil Park, Station square and the old tourist market in the historical Aswan City—Egypt). Eng. Res. J.-Fac. Eng. 2022, 51, 138–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conejos, S.; Langston, C.; Chan, E.H.; Chew, M.Y. Governance of heritage buildings: Australian regulatory barriers to adaptive reuse. Build. Res. Inf. 2016, 44, 507–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almahmoudi, M. Research Methodology; Dar Alkootob: Sana’a, Yemen, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Adas, A. Technical Guide for the Restoration of Heritage Buildings in Historic Jeddah; Jeddah Municipality: Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, 2009.

- Bahamam, A. Architectural and urban characteristics of traditional dwellings in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. In Proceedings of the First Scientific Conference (Mud Architecture at the Gate of the Twenty-First Century), Seiyun, Yemen, 1 January 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Jeddah Municipality. Jeddah Historically. Available online: https://www.jeddah.gov.sa/Jeddah/HistoricalPlaces/index.php (accessed on 30 September 2021).

- Abu Zaid, A. Architects in Old Jeddah; King Fahd National Library: Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, 2013.

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).