Abstract

The efficient recovery of rare earth elements (REEs) from low-concentration mine tailwater is crucial for resource sustainability. In this study, a novel composite adsorbent, sesame stalk biochar-supported zirconium phosphate (sBC/ZrP), was synthesized for the selective adsorption and recovery of La3+ as a representative REE. The material was characterized using SEM-EDS, BET, XRD, FTIR, and XPS. Batch adsorption experiments were conducted to evaluate the effects of pH, coexisting ions, and the adsorption kinetics and thermodynamics. The results showed that sBC/ZrP exhibited a high adsorption capacity (up to 185.83 mg/g at 35 °C for 4 h) and strong selectivity for La3+, particularly in the presence of common competing cations, although Al3+ demonstrated significant interference. The adsorption process followed pseudo-second-order kinetics and the Langmuir isotherm model, indicating monolayer chemisorption, and was determined to be spontaneous and endothermic. The material maintained over 90% adsorption efficiency after five consecutive adsorption–desorption cycles. The mechanism primarily involved complexation of La3+ with the P-OH and Zr-O groups on the composite. This work demonstrates that sBC/ZrP is a highly efficient, stable, and reusable adsorbent with significant potential for the recovery of REEs from mining tailwater.

1. Introduction

Rare earth elements (REEs), encompassing the fifteen lanthanides alongside scandium and yttrium, constitute a unique group of metallic elements with exceptional physicochemical properties. The unparalleled significance of REEs stems from their critical role in modern high-technology and green-energy applications. They are indispensable components in high-strength permanent magnets, phosphors for lighting and displays, catalysts for petroleum refining and automotive exhaust systems, and advanced ceramics. Furthermore, they are pivotal to the clean energy transition, as they are essential for manufacturing wind turbines, electric vehicle motors, and other energy-efficient technologies [1,2]. China is a major global producer and consumer of rare earth resources, which are distributed with distinctive regional characteristics. In northern China, light rare earths are primarily found in mineral form. In contrast, southern China is rich in ion-adsorption rare earth ores (IAREO) that contain medium and heavy rare earths, which are urgently needed for the development of high-tech and new materials [3,4,5].

At present, IAREO mining employs in situ leaching, which avoids soil erosion caused by the destruction of mountain vegetation by early pool leaching and heap leaching processes [6,7]. However, the in situ leaching process is generally closed when the rare earth concentration of the mother liquor is less than 100 mg/L to reduce costs, given the large injection volume of the leaching fluid and the long trailing time. The ore body will still produce a large amount of acidic (pH = 3–6) and low-concentration tailwater containing REEs (<100 mg/L) due to rainwater leaching over a long period of time [8,9]. If the tailwater is directly discharged, it will result in significant waste of rare earth resources and surrounding environmental pollution [10]. Therefore, the development of efficient enrichment and recovery technologies for rare earths from rare earth production wastewater contributes to the efficient utilization of rare earth resources and environmental protection.

Many separation technologies have been used to recover REEs from aqueous solutions, including chemical precipitation, solvent extraction, membrane separation, ion exchange, and adsorption [11]. Adsorption offers simple operation, low cost, and high efficiency, making it well-suited to the recovery of rare-earth resources from low-concentration tailwater. Adsorbents are the core of adsorption methods and must meet the requirements of high adsorption capacity, high selectivity, and reusability [12,13]. Zirconium phosphate (ZrP), as an inorganic ion-exchange material, exhibits properties such as a simple synthesis process, strong ion-exchange performance, high chemical stability, and good biological compatibility [14,15,16]. The theoretical cation exchange capacity of ZrP is 4–12 times that of clay minerals. ZrP has been widely used to remove radionuclides (e.g., Cs+, Sr2+) and heavy metal ions from wastewater, exhibiting excellent adsorption capacity [17,18,19]. However, in practical applications, ZrP nanoparticles are prone to agglomeration, reducing their specific surface area and limiting the full utilization of their adsorption properties. Loading ZrP onto substrates such as Fe3O4, montmorillonite, ion-exchange resin, silicon oxide, and other materials is a viable solution [20,21,22]. Biochar is a porous carbon-rich material obtained by pyrolysis and transformation of biomass under hypoxic or anaerobic conditions. It has a high specific surface area, a well-developed pore structure, a rich composition of surface functional groups, and stability, and is widely used in wastewater treatment [23]. The aforementioned characteristic structure of biochar facilitates the embedding and fixation of ZrP components, making biochar a suitable ZrP adsorbent carrier.

In this study, sesame stem biochar was selected as the substrate skeleton, and zirconium phosphate was uniformly loaded into its pores and on its surface. A new type of BC/ZrP composite material was prepared, which effectively reduced the agglomeration of zirconium phosphate powder and improved the adsorption performance for rare earth ions. Through structural and elemental characterization of the structure of BC/ZrP, adsorption isothermal, adsorption dynamics test, pH and impurity ion influence test, and cyclic adsorption–desorption test, the adsorption and enrichment characteristics of the material on the rare earth lanthanum ion in water were evaluated. The research results provide a scientific basis for the enrichment and recovery of rare earth elements in the tailwater of ionic rare earth mines.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals

All chemicals used in this experiment were of analytical grade. Zirconium oxychloride (ZrOCl2·8H2O) and arsenazo III (C22H18(As2)N4O14S2) were purchased from Aladdin Reagents (Shanghai) Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). Concentrated phosphoric acid (H3PO4), concentrated hydrochloric acid (HCl), sodium hydroxide (NaOH), sodium chloride (NaCl), potassium chloride (KCl), ammonium chloride (NH4Cl), anhydrous calcium chloride (CaCl2), magnesium chloride hexahydrate (MgCl2·6H2O), aluminum chloride hexahydrate (AlCl3·6H2O), anhydrous acetic acid (CH3COOH), anhydrous sodium acetate (CH3COONa) were purchased from Xilong Chemical Co., Ltd. (Shantou, China). Lanthanum nitrate hexahydrate (La(NO3)3·6H2O) was purchased from Jining Tianyi New Materials Co. (Jining, China). Sesame stems were obtained from a farm in Ganzhou City, Jiangxi Province, China. Deionized water was used in all experiments.

2.2. Preparation of Adsorbents

The cleaned and dried sesame stems were cut into 1 cm sections and loaded into a graphite crucible. Then, the crucible was filled with nitrogen for 3 min and transferred to the muffle furnace. The muffle furnace was heated to 600 °C at a heating rate of 5 °C/min, held for 0.5 h, and then cooled to room temperature. The biochars were washed 3 times with deionized water, then dried in an oven at 80 °C for 12 h, and finally mashed through a 60-mesh sieve, denoted as sBC.

In a 100 mL beaker, 0.3 g of biochar was added to 20 mL of a 10 wt% aqueous solution of ZrOCl2·8H2O and magnetically stirred for 0.5 h at 60 °C. Under stirring conditions, 20 mL of 20 vol% H3PO4 solution was added dropwise and stirred for 2 h. After the materials were collected, they were washed with deionized water 4 times, and dried in an oven at 60 °C for 12 h, denoted as sBC/ZrP.

2.3. Characterization of Adsorbents

The instruments used to measure the properties of the prepared adsorbents were as follows: scanning electron microscope (SEM, TESCAN MIRA LMS, Brno, Czech Republic), Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET, Beishide 3H-2000PS1/2, Beijing, China), X-ray diffraction (XRD, PANalytical Empyream, Almelo, The Netherlands), X-ray photoelectron spectrometer (XPS, PHI 5000 VersaProbe, Chanhassen, MN, USA), and Fourier transform infrared (FT-IR, Shimadzu IRSpirit, Kyoto, Japan). The concentrations of REEs in the aqueous solution were determined by an inductively coupled plasmaoptical emission spectrometer (ICP-OES, Agilent 5900, Santa Clara, CA, USA).

2.4. Adsorption Experiments

Batch adsorption experiments were conducted to investigate the adsorption behavior of sBC/ZrP materials for the rare earth element La3+. Typically, 20 mg sBC/ZrP was added to 20 mL La3+ aqueous solution in a 50 mL conical flask. The conical flask was shaken at 25 °C for 4 h. The 1 mL supernatant obtained after passing through a 0.22 μm filter was used to determine the La3+ concentration by Arsenazo III spectrophotometry at 655 nm (UV-5100 spectrophotometer, Metash, Shanghai, China). The adsorption capacity Qe (mg/g) was calculated using Formula (1)

where C0 and Ce (mg/L) were the initial and equilibrium ion concentration of the solution, respectively; V (mL) was the volume of the solution; m (mg) was the mass of the adsorbent.

The adsorption experiment parameters were 2–8 for initial pH, 1 min–4 h for contact time, 30–600 mg/L for initial La3+ concentration, and 35–55 °C for adsorption temperature. The pH of the adsorption solution was adjusted with 0.1 M HCl or NaOH aqueous solutions. The impurity ions (Al3+, Mg2+, Ca2+ and Na+) commonly found in actual tailwater were selected to investigate the adsorption selectivity of sBC/ZrP for La3+ at different molar concentration ratios (La:X = 1:0.2, 1:0.4, 1:0.6, 1:0.8 and 1:1; X denotes Al, Mg, Ca, Na), with the La3+ concentration fixed at 100 mg/L and the pH fixed at 5.

Pseudo-first-order (PFO) [24], pseudo-second-order (PSO) [25], and Elovich models [26] were used to determine the adsorption kinetics of sBC/ZrP by fitting the adsorption capacities with varying contact times. The Langmuir and Freundlich models [27,28] were used to determine the adsorption isotherm characteristics by fitting adsorption capacities at varying La3+ concentrations. The thermodynamic parameters, such as Gibbs free energy (ΔG), enthalpy (ΔH), and entropy (ΔS), were obtained from the Van’t Hoff equation by fitting the adsorption capacities at varying temperatures [29].

2.5. Reusability of Adsorbents

The reusability of the sBC/ZrP adsorbents (40 mg) was studied by repeated adsorption–desorption cycles in a batch mode. The adsorption solution was 40 mL of a 100 mg/L La3+ solution at pH 5.0. Elution was performed with 40 mL of 0.1 M HCl. Altogether, five cycles were performed. The La3+ adsorption capacity for each cycle was calculated.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Characterization of sBC/ZrP

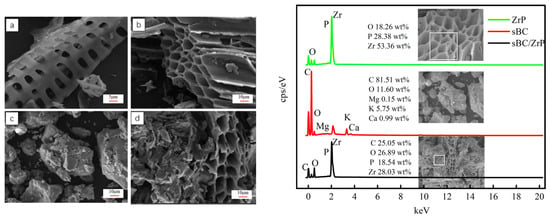

The SEM images of sBC, ZrP, and sBC/ZrP are shown in Figure 1. sBC had a large number of honeycomb pore structures, which can provide favorable space for the load of ZrP; ZrP exhibited an irregular agglomeration form; in sBC/ZrP composite materials, ZrP particles were loaded on the pore wall of sBC. According to the results of EDS elemental analysis, ZrP contained three elements: Zr, P, and O, of which Zr and P accounted for 53.36 wt% and 28.38 wt%, respectively. sBC contained C (81.51 wt%), O (11.60 wt%), Mg (0.15 wt%), Ca (0.99 wt%), K (5.75 wt%), and other elements. In contrast, sBC/ZrP contained four elements, which were Zr (28.03 wt%), P (18.54 wt%), O (26.89 wt%), and C (25.05 wt%), respectively, but the Mg, K, and Ca elements, which initially existed in biochar, completely disappeared. It may be that the minerals containing Mg, K, and Ca in the sBC were dissolved, resulting in the release of these elements in the strong-acid environment during the preparation process of sBC/ZrP. The presence of Zr and P in sBC/ZrP indicated that ZrP was successfully attached to the biochar skeleton of sBC.

Figure 1.

SEM images and EDS elemental analysis of (a,b) sBC, (c) ZrP, and (d) sBC/ZrP. The sampling areas of the EDS spectrum are the white squares or dots in the SEM illustration.

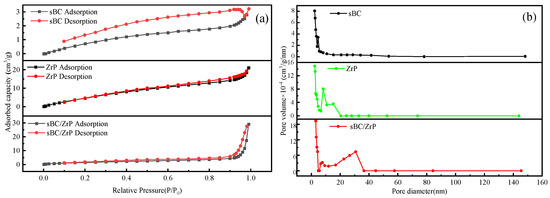

The N2 adsorption and desorption curves and pore size distribution of sBC, ZrP, and sBC/ZrP are shown in Figure 2. According to the IUPAC classification, the N2 adsorption and desorption isothermal curves of the three materials were all type III isotherms and H3 hysteresis rings. The appearance of H3 hysteresis rings usually indicated a mesoporous structure [30,31]. The measured specific surface areas (SSA) of sBC, ZrP, and sBC/ZrP were 26.492, 6.854, and 6.226 m2/g, respectively; the BJH pore volumes were 0.028, 0.004, and 0.044 mL/g, and the BJH pore sizes were 3.059, 3.052, and 3.058 nm, respectively. In addition, sBC/ZrP exhibited a broad peak in pore size distribution centered at approximately 40 nm. Although some pores of the sBC were clogged by ZrP particles during sBC/ZrP preparation, reducing the SSA of sBC/ZrP, the overall pore structure was optimized, providing an effective channel for La3+ adsorption.

Figure 2.

BET-BJH analysis of sBC, ZrP, and sBC/ZrP. (a) N2 adsorption–desorption isotherms; (b) pore size distribution.

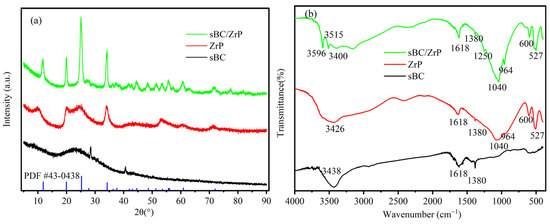

The XRD patterns of sBC, ZrP, and sBC/ZrP are shown in Figure 3a. The XRD pattern of sBC exhibited a broad diffraction pattern, indicating an amorphous structure. Although the XRD pattern of ZrP showed a wide range of diffraction peaks, the characteristic peaks of XRD appeared at 2θ of 11.82°, 19.94°, 25.21°, and 34.19°, consistent with zirconium phosphate with the chemical structural formula ZrO2·0.8P2O5·1.6H2O (PDF card number: 43-0438). The P/Zr molar ratio in this structural formula was consistent with the EDS results of ZrP, both of which were 1.6:1. The characteristic diffraction peaks of sBC/ZrP at these angles have been strengthened, indicating that the biochar could promote the crystallization growth of ZrP when ZrP was loaded on biochar sBC.

Figure 3.

XRD patterns (a) and FTIR spectra (b) of sBC, ZrP, and sBC/ZrP.

The FTIR spectra of sBC, ZrP, and sBC/ZrP are shown in Figure 3b. Among the three materials, the bands around 3400 were attributed to the stretching vibration of water molecules and surface -OH, and the bands at 1618 cm−1 were attributed to the bending vibration of water molecules and surface -OH. For sBC, the band at 1618 cm−1 was strong and may correspond to the C=O vibration in addition to the bending vibration of the OH group. The band at 1380 cm−1 was attributed to C-H and β type -OH vibrations [32,33]. For ZrP and sBC/ZrP, the broad bands around 3515 and 3596 cm−1 were actually an envelope of peaks due to P-OH stretching vibration of various P-OH types [34]. The bands around 1040 cm−1 were due to the vibration of P-O in the PO43− groups. The bands at 1250 and 964 cm−1 corresponded to the in- and out-of-plane vibrations of P-OH, respectively [35]. The vibration of the Zr-O bonds was located at 600 and 527 cm−1 [36]. In summary, sBC/ZrP mainly exhibited the absorption bands of the characteristic functional groups of ZrP, and the adsorption properties for the rare earth La3+ were primarily affected by the components of ZrP.

3.2. Adsorption Behaviors of La3+ by sBC/ZrP

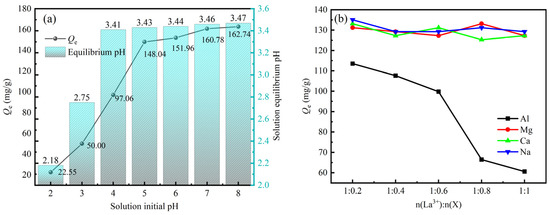

The form of rare earth ions in solution and the nature of functional groups on the adsorbent surface are affected by the initial solution pH. As shown in Figure 4a, at the initial pH of 2, the adsorption capacity of sBC/ZrP for La3+ was only 22.55 mg/g, indicating a low adsorption affinity. This occurred because H+ was adsorbed onto the adsorbent surface under strongly acidic conditions, competing with La3+ for adsorption sites. This protonation of the adsorbent surface generated positive charges that repelled La3+ ions in solution, thereby impairing La3+ adsorption [37]. As the initial pH increased from 2 to 4, protons were released from the adsorbent surface, thereby increasing its negative charge and enhancing its adsorption capacity for La3+. Furthermore, La3+ was converted to hydrated ions [La(OH)2+] as pH increased [38]. Under the combined influence of these two effects, the La3+ adsorption capacity increased from 22.55 mg/g to 97.06 mg/g. At initial solution pH values of 4–8, the active adsorption sites on the adsorbent surface gradually saturated, stabilizing the La3+ adsorption capacity at 148.04–162.74 mg/g. This demonstrated that sBC/ZrP can stably adsorb La3+ in weakly acidic environments. The equilibrium pH of the solution after adsorption was also measured (Figure 4a), which decreased as the initial pH increased from 2 to 8, then stabilized between 3.41 and 3.47. The decrease in pH was due to ion exchange between H+ from the -OH groups of the phosphate groups of sBC/ZrP and the solution La3+ [39], and the hydrolysis of La3+ to La(OH)2+, which consumed OH− ions [40].

Figure 4.

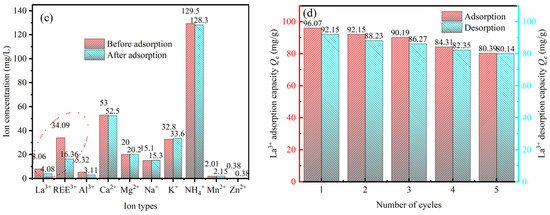

Adsorption behavior of La3+ by sBC/ZrP under the influence of the initial pH (a), the coexisting impurity ions (b), the actual tailwater (c), and the number of adsorption–desorption cycles (d).

The adsorption capacities of La3+ onto sBC/ZrP in the presence of coexisting impurity ions are shown in Figure 4b. At different molar concentration ratios of La3+ and impurity ions, the three impurity ions, Ca2+, Mg2+, and Na+, exerted a relatively minor influence on La3+ adsorption capacity, with adsorption capacity remaining around 130 mg/g. Conversely, Al3+ significantly impacted La3+ adsorption capacity, with the adsorption capacity for La3+ decreasing to only 60.59 mg/g at a La/Al molar concentration ratio of 1:1. Similar results were obtained by Zhang et al., who used synthetic zeolites for adsorbing REEs from mining tailwater [41]. Their findings indicated that Al3+ significantly hindered REE adsorption, whereas monovalent and divalent ions exhibited negligible interference. They claimed that the higher charge density of trivalent ions strengthened their interaction with adsorption sites on the zeolite surface. Moreover, compared with REE ions, Al3+ has a smaller ionic radius and higher charge density, thereby enhancing its adsorption selectivity. In our previous study, density functional theory (DFT) calculations were employed to analyze the adsorption behavior of Al3+, La3+, and NH4+ on zirconium phosphate [38]. The results revealed adsorption energies of −2149.5, −375.7, and −22.8 kJ·mol−1, and charge transfers of 1.770, 1.416, and 0.098 e for Al3+, La3+, and NH4+, respectively. The average bond lengths of Al–O and La–O were 1.900 Å and 2.517 Å. These data provided a theoretical explanation at the microscopic level for the observed adsorption selectivity order: Al3+ > La3+ > NH4+.

The actual IAREO tailwater was used to evaluate the selective adsorption effect of sBC/ZrP on La3+ and total rare earth ions REE3+ (Figure 4c). It can be seen that the primary ions in the tailwater were rare earth REE3+ (24.09 mg/L, of which the concentration of La3+ is 8.06 mg/L) and Al3+ (5.32 mg/L), Ca2+ (53.00 mg/L), Mg2+ (20.00 mg/L), Na+ (15.10 mg/L), K+ (32.8 mg/L) and NH4+ (129.50 mg/L), as well as heavy metals Mn2+ (2.01 mg/L) and Zn2+ (0.38 mg/L). The impurity ions were primarily alkali and alkaline earth metals, with a small amount of aluminum. The concentration of heavy metal ions (such as Mn2+ and Zn2+) was low, whereas that of ammonium ions was high because ammonium sulfate was used as a leaching agent during mining. The concentration of La3+ decreased from 8.06 mg/L to 4.08 mg/L after adsorption, and the total REE3+ decreased from 34.09 mg/L to 16.36 mg/L. Except for Al3+, the concentration of other impurity ions has hardly changed, indicating that sBC/ZrP had a high selectivity for the enrichment of REE3+ in the actual tailwater.

The desorption and reusability performance of the adsorbent are key indicators for assessing its practical engineering application. Five adsorption–desorption cycle experiments were carried out using 0.1 mol/L HCl solution as the desorbent, as shown in Figure 4d. With increasing cycle number, the adsorption capacity of sBC/ZrP for La3+ decreased slightly, but it still maintained a good adsorption effect. After 5 cycles, the adsorption of La3+ by sBC/ZrP decreased from 96.07 mg/g to 80.39 mg/g, and the adsorption rate decreased by 10.7% when compared with the first use. The reason may be that partial loss of the adsorbent and loss of surface-active functional groups during the cycle slightly weakened the adsorption performance. The results show that sBC/ZrP can be used as an efficient, reusable adsorbent material with strong potential for practical IAREO tailwater treatment.

Compared with most adsorbents, sBC/ZrP exhibited advantages, including high capacity (Table 1), rapid adsorption, and excellent reusability for La3+ adsorption. Its outstanding selective adsorption capability further made it the preferred material for REE recovery from tailwater.

Table 1.

Comparison of REEs adsorption performance between sBC/ZrP and other adsorbents.

3.3. Adsorption Kinetics

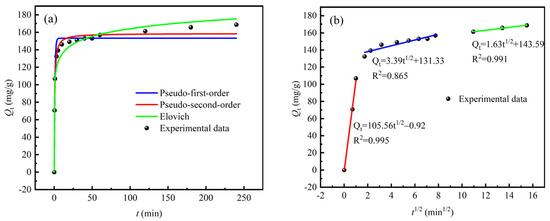

The adsorption capacity of La3+ by sBC/ZrP as a function of contact time at room temperature is shown in Figure 5. The adsorption process of the adsorbent can be divided into two stages: in the initial stage (within 0–10 min), the adsorption rate was high, then it gradually slowed down and stabilized. This is because in the initial stage of adsorption, there were a large number of unoccupied active sites on the surface of sBC/ZrP. At the same time, the La3+ concentration in the solution was high, and the mass-transfer driving force was strong, so adsorption proceeded rapidly [52]. As the adsorption reaction progressed (after 10 min), La3+ gradually occupied the active sites, and the La3+ concentration in the solution decreased, thereby reducing the mass-transfer driving force and the adsorption rate. Ultimately, when the surface-active sites were saturated (after 30 min), the adsorbent reached kinetic equilibrium, and the adsorption process stabilized, with a maximum adsorption capacity of 169.75 mg/g.

Figure 5.

Adsorption kinetics of La3+ by sBC/ZrP (C0 = 200 mg/L, T = 25 °C). (a) Adsorption kinetics models; (b) Internal diffusion model.

To investigate the adsorption kinetics of La3+ by sBC/ZrP, the data were fitted using the following models: pseudo-first-order, pseudo-second-order, and the Elovich model, with the corresponding fitting parameters shown in Table 1. The correlation coefficient (R2 = 0.987) of the pseudo-second-order model is higher than that of the pseudo-first-order model (R2 = 0.961) and the Elovich model (R2 = 0.949), and the equilibrium adsorption capacity obtained by the pseudo-second-order model was closer to the experimental value. The results show that the pseudo-second-order model better described the adsorption of La3+ by sBC/ZrP and that the adsorption process was primarily driven by chemical adsorption [53].

According to the internal diffusion model [54], the adsorption of La3+ onto sBC/ZrP can be divided into three stages: liquid-membrane diffusion, intra-particle diffusion, and equilibrium adsorption. The results show that intra-particle diffusion was a significant rate-limiting step. In the first stage, La3+ was rapidly adsorbed by a large number of unoccupied active sites on the outer surface of sBC/ZrP, resulting in a rapid increase in adsorption capacity in a short period of time; in the second stage, as the outer surface of sBC/ZrP was heavily occupied, the adsorption rate was controlled by the diffusion process of La3+ inside sBC/ZrP, which slowed down significantly; in the third stage, when the adsorption was close to equilibrium, La3+ can still slowly enter the deeper pores of sBC/ZrP, so that the adsorption capacity could be slightly increased.

3.4. Adsorption Thermodynamics

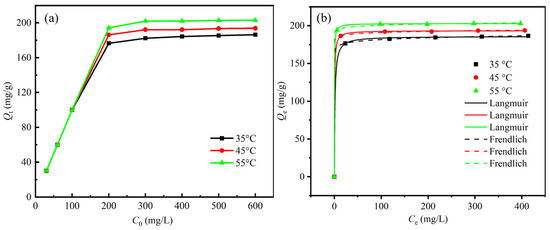

Figure 6a illustrates the influence of La3+ initial concentration on sBC/ZrP adsorption under varying temperature conditions, while Table 2 presents the Langmuir and the Freundlich isotherm model fitting results. The adsorption capacity of sBC/ZrP for La3+ increased linearly with increasing initial La3+ concentration below 200 mg/L across all temperatures. Then the adsorption capacity of sBC/ZrP towards La3+ approached saturation, with maximum adsorption capacities of 182.35 mg/g, 192.16 mg/g, and 201.96 mg/g at 35 °C, 45 °C, and 55 °C, respectively.

Figure 6.

Effect of La3+ initial concentration and solution temperature on the adsorption of La3+ by sBC/ZrP. (a) Adsorption capacity versus initial concentration; (b) Adsorption isotherm model fitting.

Table 2.

Fitting parameters of the adsorption kinetics of La3+ by sBC/ZrP.

As shown in the Langmuir isotherm fit (Figure 6b), the adsorption of La3+ by sBC/ZrP increased with increasing equilibrium concentration, Ce, and ultimately approached saturation. The high goodness of fit of the Langmuir model (R2 > 0.99) indicated that the adsorption of La3+ on the surface of sBC/ZrP conformed to the single-molecule-layer-coverage mechanism [55]. In addition, the Freundlich model fit (Figure 6b) exhibited the expected behavior, and the adsorption intensity parameter (n) exceeded 1 at all three temperatures. It showed a strong interaction between the surface-active site of sBC/ZrP and La3+, which facilitated adsorption. Taken together, the adsorbent sBC/ZrP had a strong adsorption affinity for La3+.

From Table 3, the negative value of ΔG at all test temperatures indicated that the adsorption reaction was carried out spontaneously within the experimental temperature range (35–55 °C); the positive enthalpy change ΔH suggested that the adsorption process was an endothermic reaction, which was entirely consistent with the phenomenon that the adsorption capacity observed in the experiment increased with the increase in temperature. It also showed that the high-temperature environment was more conducive to adsorption. The negative entropy change ΔS reflected the decrease in the chaos of the system during the adsorption process, which was in line with the orderly phenomenon that La3+ was fixed to the surface of the adsorbent in a state of free movement from the solution. It showed that the adsorption process was a typical feature of the transfer of adsorbent molecules from the solution phase to the solid phase. Together, these thermodynamic parameters confirmed that the adsorption of La3+ by sBC/ZrP was thermodynamically spontaneous.

Table 3.

Adsorption isotherm model parameters and thermodynamic parameters of La3+ by sBC/ZrP.

3.5. Adsorption Mechanism

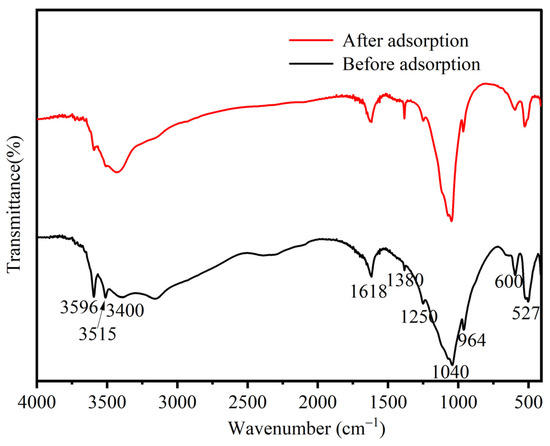

The FTIR and XPS spectra before and after La3+ adsorption on BC/ZrP were compared and analyzed to elucidate the adsorption mechanism of La3+. From the FTIR spectra (Figure 7), the bands at 3515 and 3596 cm−1 in the high-frequency region, which were attributed to the stretching vibration of P-OH, were significantly weakened after the adsorption, and in the low-frequency region, the bands at 527 and 600 cm−1 corresponding to the vibration of Zr-O were also weakened considerably. The observed band changes indicated that the P-OH and Zr-O groups of sBC/ZrP were involved in the adsorption of La3+.

Figure 7.

FTIR spectra of sBC/ZrP before and after La3+ adsorption.

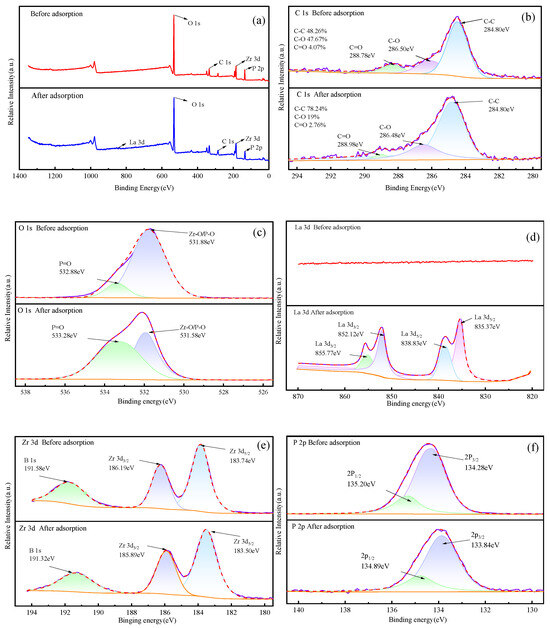

The XPS full spectra of sBC/ZrP before and after adsorption of La3+ are shown in Figure 8a. The full spectrum contained C, O, Zr, and P before adsorption, whereas the La 3d peak appeared after adsorption, with a content of 2.5 at%, indicating that La3+ was adsorbed onto sBC/ZrP. For the fine spectra of C 1s (Figure 8b), the relative content of C-O decreased from 47.67% to 19%, and the relative content of C=O decreased from 4.07% to 2.76% after adsorption. It was speculated that La3+ had a complex reaction with the oxygen-containing functional group on sBC/ZrP [56], and the aromatic skeleton C-C/C=C of the biochar did not participate in the adsorption process, with the relative content rising from 48.26% to 78.24%. For the fine spectra of O 1s (Figure 8c), the binding energy of the P-O/Zr-O bond decreased from 531.88 eV to 531.58 eV, and the binding energy of the P=O bond rose from 532.88 eV to 533.28 eV after adsorption. It was speculated that La3+ interacted with surface O atoms to form a surface complex on sBC/ZrP [57], consistent with the FTIR results. For the fine spectra of La 3d (Figure 8d), La 3d5/2 and La 3d3/2 appear after adsorption, further indicating the adsorption of La3+ on the surface of sBC/ZrP. For the fine spectra of Zr 3d (Figure 8e), the binding energy at 183.74 eV and 186.19 eV before adsorption corresponds to the peaks of Zr 3d5/2 and Zr 3d3/2, respectively. These two peaks were typical of Zr4+, indicating that most of the Zr in sBC/ZrP was octahedrally coordinated to O in the form of the tetravalent oxidation state (Zr4+) [58,59]. The binding energies of Zr 3d5/2 and Zr 3d3/2 after adsorption decreased to 183.50 eV and 185.89 eV, respectively, indicating that the Zr-O in sBC/ZrP reacted with La3+ to form a complex in the form of Zr-O-La, which was consistent with the O 1s energy spectrum peak and the FTIR analysis results. For the fine spectra of P 2p (Figure 8f), the binding energies at 134.28 eV and 135.20 eV before adsorption corresponded to the peaks of 2p3/2 and 2p1/2 of the H2PO4− group, respectively [60]. The peaks of P 2p were around 133.38 eV, indicating that the P existed in the form of a pentavalent oxidation state (P5+). The binding energy of La 2p3/2 and 2p1/2 decreased to 133.84 eV and 134.89 eV after adsorption, respectively, indicating that La3+ exchanged with the H+ of the phosphate group to generate a complex in the form of P-O-La [61], which was consistent with the adsorption experiment results and FTIR analysis results.

Figure 8.

XPS spectra of sBC/ZrP before and after La3+ adsorption. (a) full spectrum, (b) C 1s, (c) O 1s, (d) La 3d, (e) Zr 3d, (f) P 2p.

4. Conclusions

Sesame stalk biochar-loaded zirconium phosphate (sBC/ZrP) was synthesized, and its structural properties were analyzed to investigate its adsorption characteristics and mechanism for La3+. After composite modification, the overall pore structure of sBC/ZrP was optimized, and the pore volume increased. The optimal pH range for La3+ adsorption by sBC/ZrP was 5–8. The presence of trivalent Al3+ exhibited significantly greater inhibition than that of monovalent or divalent impurity ions. The material demonstrated high selectivity for REE3+ enrichment in actual tailings water, maintaining an adsorption rate exceeding 90% after five adsorption–desorption cycles. La3+ adsorption on sBC/ZrP reached equilibrium after 30 min. At 35 °C, the theoretical maximum adsorption capacity was 185.83 mg/g. The adsorption process followed pseudo-second-order kinetics and the Langmuir isotherm model, characterized as spontaneous, endothermic, and entropy-increasing. The adsorption mechanism of BC/ZrP for La3+ involves Zr-O groups forming complexes with La3+, P-OH groups reacting with La3+ to form P-O-La complexes while releasing H+, and C-O and C=O groups undergoing complexation reactions with La3+. In summary, sBC/ZrP exhibited excellent structural properties, high selectivity, high adsorption capacity, and outstanding cycling stability, demonstrating significant application potential in the adsorption and recovery of La3+ from mining tailings.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.P.; methodology, N.Z. and Y.Y.; software, N.Z.; validation, W.K.; formal analysis, X.Z.; investigation, N.Z. and Y.Y.; resources, W.K.; data curation, N.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, N.Z.; writing—review and editing, X.Z.; visualization, X.Z.; supervision, C.P.; project administration, C.P.; funding acquisition, C.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of China [Grant No. 52564030]; Natural Science Foundation of Jiangxi Province of China [Grant No. 20252BAC240381], Anhui Engineering Research Center for Coal Clean Processing and Carbon Reduction [Grant No. CCCE-2024002]; the Program of Qingjiang Excellent Young Talents, Jiangxi University of Science and Technology [Grant No. JXUSTQJYX2020009].

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

We sincerely thank the editorial staff and reviewers for their valuable time, efforts, and insightful comments devoted to this manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Weichang Kong was employed by the company China Rare Earth (Fujian) Mining Co., Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Goodenough, K.M.; Wall, F.; Merriman, D. The rare earth elements: Demand, global resources, and challenges for resourcing future generations. Nat. Resour. Res. 2018, 27, 201–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massari, S.; Ruberti, M. Rare earth elements as critical raw materials: Focus on international markets and future strategies. Resour. Policy 2013, 38, 36–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Xiao, Y.; Feng, X.; Wang, J.; Ma, Z.; Yao, R.; Zhai, Y.; Tian, L. Leaching of ion adsorption rare earths and the role of bioleaching in the process: A review. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 468, 143067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Shao, S.; Yu, X.; Huang, M.; Qiu, G.; Chen, Z.; Zhao, H.; Shen, L. Evaluation of microbial metabolites in the bioleaching of rare earth elements from ion-adsorption type rare earth ore. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2025, 13, 117851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, G.; Chen, H.; Feng, Y.; Wu, C.; Li, S.; Zhang, Y.; Lai, C.K. Are South China granites special in forming ion-adsorption REE deposits? Gondwana Res. 2024, 125, 82–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Wang, G.; Xu, J.; Kang, S.; Zhu, J.; Liang, X.; Yang, Y.; Wei, J.; He, H. Recovery of rare earth elements from ion-adsorption deposits using electro kinetic technology: A comparative study on leaching agents. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 499, 156094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Sha, A.; He, Z.; Wu, C.; Xu, Y.; Hu, J.; Xu, Z.; Ruan, C. Leaching kinetics and permeability of polyethyleneimine added ammonium sulfate on weathered crust elution-deposited rare earth ores. J. Rare Earths 2023, 42, 1610–1619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Xianping, L.; Dan, Z.; Chen, W.; Qihai, T.; Lu, H. Adsorption Characteristics of Biochar to Ammonia Nitrogen in Rare Earth Ionic Mine Waste. J. Chin. Soc. Rare Earths 2021, 39, 916–926. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, X.; Zhou, H.; Peng, C.; Wang, G.; Luo, J. Improved adsorption of rare earth La3+ by monovalent salts (Na, K, and NH4) modified titanium phosphate (TiP) materials. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2025, 13, 119940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, T.; Zheng, X.; Ji, B.; Xu, Z.; Bao, S.; Zhang, X.; Li, G.; Mei, J.; Li, Z. Green recovery of rare earth elements under sustainability and low carbon: A review of current challenges and opportunities. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2024, 330, 125501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omoniyi, P.; Chris, B.A.; Olanrewaju, F.; Katri, L.; Leslie, P. Rare earth elements removal techniques from water/wastewater: A review. Desalination Water Treat. 2018, 130, 71–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogata, T.; Narita, H.; Tanaka, M. Adsorption behavior of rare earth elements on silica gel modified with diglycol amic acid. Hydrometallurgy 2015, 152, 178–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Liu, S.; Li, L.; Zhang, K. Research Progress on Enrichment of Rare Earth from Low Concentration Rare Earth Solution. Hydrometall. China 2025, 44, 283–293. [Google Scholar]

- Arshid, B.; Sozia, A.; Ahmad, M.L.; Aaliya, Q.; Taniya, M.; Nabi, D.G.; Hussain, P.A. Revisiting the Old and Golden Inorganic Material, Zirconium Phosphate: Synthesis, Intercalation, Surface Functionalization, and Metal Ion Uptake. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2020, 59, 22353–22397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos-Garcés, M.V.; González-Villegas, J.; López-Cubero, A.; Colón, J.L. New Applications of Zirconium Phosphate Nanomaterials. Acc. Mater. Res. 2021, 2, 793–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pica, M. Treatment of Wastewaters with Zirconium Phosphate Based Materials: A Review on Efficient Systems for the Removal of Heavy Metal and Dye Water Pollutants. Molecules 2021, 26, 2392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Vivas, E.L.; Suh, Y.J.; Cho, K. Highly efficient and selective removal of Sr2+ from aqueous solutions using ammoniated zirconium phosphate. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2022, 10, 107333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, P.; Pan, B.; Pan, B.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, Q. A comparative study on lead sorption by amorphous and crystalline zirconium phosphates. Colloid. Surface. A 2008, 322, 108–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mrad, O.; Abdul-Hadi, A.; Arsan, H. Preparation and characterization of three different phases of zirconium phosphate: Study of the sorption of 234Th, 238U, and 134Cs. J. Radioanal. Nucl. Chem. 2010, 287, 177–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Fu, M.; Li, J.; Niu, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Sun, Q. New insight into polystyrene ion exchange resin for efficient cesium sequestration: The synergistic role of confined zirconium phosphate nanocrystalline. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2024, 35, 108442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Dong, X.; Yang, H. Montmorillonite-mediated electron distribution of zirconium phosphate for accelerating remediation of cadmium-contaminated water and soil. Appl. Clay Sci. 2023, 236, 106883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahamad, T.; Naushad, M.; Al-Maswari, B.M.; Ahmed, J.; Alothman, Z.A.; Alshehri, S.M.; Alqadami, A.A. Synthesis of a recyclable mesoporous nanocomposite for efficient removal of toxic Hg2+ from aqueous medium. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2017, 53, 268–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, J.; Dai, Y.; Nie, Q.; Liao, Z.; Peng, L.; Sun, D. Research progress in the adsorption of heavy metal ions from wastewater by modified biochar. Chin. J. Biotechnol. 2024, 40, 4467–4479. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, F.; Zhao, J.; Pan, F. Adsorption Properties toward Trivalent Rare Earths by Alginate Beads Doping with Silica. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2013, 52, 3453–3461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khamizov, R.K. A Pseudo-Second Order Kinetic Equation for Sorption Processes. Russ. J. Phys. Chem. A Focus Chem. 2020, 94, 171–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenda, G.T.; Tchuifon, D.R.T.; Bopda, A.; Dongmo, M.; Tiotsop, I.H.K.; Nguena, K.L.T.; Fotsop, C.G.; Angwafor, N.G.N.; Basavarajaiah, S.M.; Bandegharaei, A.H. Investigating the adsorption of acid blue 90 onto porous MIL53(Fe) and Cu-BTC sorbents: An examination of process parameters, isotherm modelling, and kinetic studies. Results Chem. 2025, 17, 102615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazhar, K.; Fardioui, M.; Bensalah, J.; Houmia, I.; Kaibous, N.; Guedira, T. Adsorption performance of heavy metals Co2+, Cu2+ and Zn2+ contained in aqueous solutions by two types of clay: A kinetic study, mathematical and thermodynamic modelling. J. Indian Chem. Soc. 2025, 102, 102241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Que, Z.G.; Margalli, K.S.L.; Saltijeral, J.M.U.; Pavón, A.A.S.; García, H.M.; Alamilla, P.G.; Pérez, G.E.C.; Pérez, J.C.A.; Torres, J.G.T. Activated carbon synthesised from lignocellulosic cocoa pod husk via alkaline and acid treatment for methylene blue adsorption: Optimisation by response surface methodology, kinetics, and isotherm modelling. RSC Adv. 2025, 15, 47231–47254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, L.; Zhang, M. Adsorption of Methylene Blue on Chestnut Shell-Based Activated Carbon: Calculation of Thermodynamic Parameters for Solid–Liquid Interface Adsorption. Catalysts 2022, 12, 813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Li, Z.; Xi, H. Research progress of gas-solid adsorption isotherms. Ion Exch. Adsorpt. 2004, 20, 376–384. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Ji, J.; Tang, R.; Lu, C.; Yu, S.; Li, D.; Tong, Z.; Zhang, H.; He, M. Preparation of dual organic modified magnetic bentonite for Cu(II) and Zn(II) adsorption. J. Chem. Eng. Chin. Univ. 2022, 36, 276–286. [Google Scholar]

- Muratore, N.; Lascari, D.; Cataldo, S.; Raccuia, S.G.M.; Lando, G.; Meo, P.L.; Chiodo, V.; Maisano, S.; Urbani, F.; Pettignano, A. Recovery of rare earth elements by adsorption on biochar of dead Posidonia oceanica leaves. J. Rare Earths 2025, 43, 2551–2561. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.Y.; Li, P.Q.; Li, X.C.; Sun, P.; Zhao, X.Y.; Li, J.; Xin, Z.R. Effect of Enteromorpha prolifera Biochar on the Adsorption Characteristics and Adsorption Mechanisms of Ammonia Nitrogen in Rainfall Runoff. Environ. Sci. 2021, 42, 274–282. [Google Scholar]

- Hajipour, A.R.; Karimi, H. Synthesis and characterization of hexagonal zirconium phosphate nanoparticles. Mater. Lett. 2014, 116, 356–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Wang, A.; Wang, Z.; Chen, M.; Wang, W.; Sun, L.; Liu, X. Titanium functionalized α-zirconium phosphate single layer nanosheets for photocatalyst applications. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 93969–93978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Peng, C.; Wang, G.; Qin, L.; Yang, Y. Preparation of magnetic Fe3O4@ZrP composites and its La3+ adsorption performance. Fine Chem. 2025, 42, 2425–2435. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z.; Wang, L.; Meng, J.; Liu, X.; Xu, J.; Wang, F. Brookes, Zeolite-supported nanoscale zero-valent iron: New findings on simultaneous adsorption of Cd(II), Pb(II), and As(III) in aqueous solution and soil. J. Hazard. Mater. 2018, 344, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, C.; Zhu, X.; Peng, C.; Guo, C. Adsorption of Rare Earth La3+ by α- zirconium phosphate:An Experimental and Density Functional Theory Study. J. Mol. Liq. 2022, 368, 120668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- José, G.; Lorena, M.; Fernando, V.; Carlos, B. Recovery of lanthanum, praseodymium and samarium by adsorption using magnetic nanoparticles functionalized with a phosphonic group. Hydrometallurgy 2021, 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentouhami, E.; Bouet, G.M.; Meullemeestre, J.; Vierling, F.; Khan, M.A. Physicochemical study of the hydrolysis of Rare-Earth elements (III) and thorium (IV). Comptes Rendus-Chim. 2004, 7, 537–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Cheng, J.; Xu, G.; Hou, X.; Yu, Z.; Liu, W.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, J.; Yang, J.; Wu, M.; et al. Selective recovery of rare earth elements from mine wastewater using the magnetic zeolite prepared by rare earth tailings. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 511, 161871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Gao, C.; Duan, X.; Chen, Y.; Shen, K.; Peng, J.; Yang, Z.; An, S.; Chen, Z.; Qiao, C. Magnetic NaA Zeolites Synthesized from Dual Solid Wastes Enables Selective Efficient Recovery of Rare Earth Ions from Neodymium Iron Boron Electroplating Wastewater. Langmuir ACS J. Surf. Colloids 2025, 41, 33951–33965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, M.; Xia, S.; Liu, S.; Jin, C.; Deng, S.; Xiao, W.; Ding, S.; Chen, C. Two novel nitrogen-rich metal-organic nanotubes: Syntheses, structures and selective adsorption toward rare earth ions. Dalton Trans. 2023, 52, 17846–17853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Zhou, C.; Yang, K.; Wang, F.; Liu, G. Robust EDTA-Functionalized MIL-101(Cr)-NH2 for Affinity-Enhanced Rare-Earth Ion Capture: Mechanistic Evaluation and Density Functional Theory Insights. Langmuir ACS J. Surf. Colloids 2025, 41, 20709–20722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, G.; Zhou, C.; Li, X.; Cao, Z.; Jiao, F.; Zhong, H.; Ma, X.; Wang, S. Structural Modification of Polyacrylic Resin by Hydroxamic acid to Increase the Adsorption Performance for rare Earth ions. J. Polym. Environ. 2024, 33, 1006–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Ju, P.; Yuan, W.; Zhou, C.; Zheng, Z.; Sun, J.; Shi, S. Adsorption of rare earth ions from highly saline media by a pyridine-modified activated carbon sorbent. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2024, 12, 114438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, L.; Yu, X.; Zhou, H.; Wang, J.; Zhao, H.; Qiu, G.; Chen, Z. Optimization and mechanism studies for the biosorption of rare earth ions by Yarrowia lipolytica. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2024, 31, 52118–52131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Wang, J.; Yang, B.; Liu, Y.; Qiu, G. Selective Separation of Rare Earth Ions from Mine Wastewater Using Synthetic Hematite Nanoparticles from Natural Pyrite. Minerals 2024, 14, 464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusrini, E.; Usman, A.; Sani, F.A.; Wilson, L.D.; Abdullah, M.A.A. Simultaneous adsorption of lanthanum and yttrium from aqueous solution by durian rind biosorbent. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2019, 191, 488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zheng, X.; Bian, T.; Zhang, Y.; Mei, J.; Li, Z. Phosphorylated-CNC/MWCNT thin films-toward efficient adsorption of rare earth La (III). Cellulose 2020, 27, 3379–3390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Yan, C.; Zhou, S.; Liang, T.; Wen, X. Preparation of montmorillonite grafted polyacrylic acid composite and study on its adsorption properties of lanthanum ions from aqueous solution. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2019, 26, 9861–9875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobri, N.A.M.; Harun, N.; Yunus, M.Y.M. A review of the ion exchange leaching method for extracting rare earth elements from ion adsorption clay. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 2024, 208, 94–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Liang, C.; Liao, X.; Ren, S. Study on Adsorption Performance of Spirulian Biosorbent for Y3+ in Rare Earth Wastewater. Chin. Rare Earths 2023, 44, 62–73. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Guo, X. Rethinking of the intraparticle diffusion adsorption kinetics model: Interpretation, solving methods and applications. Chemosphere 2022, 309, 136732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majeed, M.D.; Roushani, M. A novel synthesis of ZIF-9-Mel/GO/SA aerogel nanocomposite and its highly efficient removal of U(VI) from aqueous solution. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2025, 176, 114261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Zhang, L.; Ning, K.; Yang, W. Biochar with nanoparticle incorporation and pore engineering enables enhanced heavy metals removal. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2023, 11, 111056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, X.; Peng, C.; Wang, G.; Qin, L.; Zhu, X.; Liu, C. Adsorption of Rare Earth La3+ by Magnetic Nano-Titanium Phosphate Fe3O4@TiP. J. Chin. Soc. Rare Earths 2025, 43, 1108–1120. [Google Scholar]

- Miao, Z.; Li, Z.; Liang, M.; Meng, J.; Zhao, Y.; Xu, L.; Mu, J.; Zhou, J.; Zhuo, S.; Si, W. Ordered mesoporous titanium phosphate material: A highly efficient, robust and reusable solid acid catalyst for acetalization of glycerol. Chem. Eng. J. 2020, 381, 122594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, K.; Nandi, M.; Bhaumik, A. Enhancement in microporosity and catalytic activity on grafting silica and organosilica moieties in lamellar titanium phosphate framework. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 2008, 343, 55–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Zhong, L.; Sun, J.; Shen, J. A Facile Layer-by-Layer Adsorption and Reaction Method to the Preparation of Titanium Phosphate Ultrathin Films. Chem. Mater. 2005, 17, 3563–3569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, K.; Pan, B.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, W.; Jiang, P.; Hong, C.; Pan, B.; Zhang, Q. Adsorption of Pb2+, Zn2+, and Cd2+ from waters by amorphous titanium phosphate. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2008, 318, 160–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.