Abstract

Cu and Cr are the essential alloying elements for low-Ni stainless steels. An effective and economical method has been developed for the direct production of Cu-Cr-Fe master alloys through the synergistic reduction of chromite and copper smelting slag. The smelting conditions for synergy reduction were systematically investigated by combining thermodynamic calculations and high-temperature experiments. The results indicate that synergistic reduction drives the reactions of Cr2O3, FeO, and Cu2O with carbon in a positive direction, which can increase their recovery and decrease the flux and fuel costs. The optimum slag composition was identified to control the (CaO + MgO)/(SiO2 + Al2O3) ratio between 0.62 and 0.72, where the slag is fully liquid, resulting in an efficient separation of the alloy from the slag. At 1550 °C, with 50 wt% chromite and 50 wt% copper smelting slag as raw materials, a Cu-Cr-Fe alloy containing 5.2 wt% Cu, 28.6 wt% Cr and 57.9 wt% Fe was produced, while the contents of FeO, Cu2O, and Cr2O3 in the final slag were 0.057 wt%, 0.059 wt%, and 0.23 wt%, respectively.

1. Introduction

The global production of stainless steel, which is widely used in aerospace engineering, naval architecture, the automotive industry, and infrastructure construction, has reached 58.4 million tons in 2023 [1], thanks to its excellent corrosion resistance [2,3,4,5]. Low-cost AISI 200-series stainless steels containing Cu have been widely applied, due to low nickel additions in the backdrop of high nickel prices [6]. Stainless steel production includes master alloy preparation in a submerged arc furnace [7], alloy composition adjustment in an electric arc furnace [8], and alloy refining in an argon–oxygen decarburization converter [9]. Ferrochromium, an important master alloy for the production of stainless steel, is generally produced by reducing chromite with carbon in a submerged arc furnace [10]. Due to the high melting point characteristics of Cr2O3-containing slags and Cr-containing alloys, the production of ferrochromium requires high temperatures exceeding 1700 °C, as well as a large amount of silica, to decrease the liquidus temperature of the slag [11,12,13,14,15]. Furthermore, in the production of ferrochromium, the recovery rate of chromium is usually below 90 wt% [16,17]. The Cr-containing slag has a risk of polluting the soil and water [18,19,20].

To reduce the production cost of ferrochromium and increase the recovery rate of chromite, the co-smelting of chromite with other minerals/wastes has become a new trend. These minerals/wastes provide not only valuable components (such as Fe, Cu, or Ni) but also flux for ferrochromium production, thereby reducing the production cost of stainless steel. Zhu et al. [21] studied the reduction of chromite and magnetite in the blast furnace process. The introduction of magnetite reduces the Cr content in the Cr-Fe alloy, which lowers the liquidus temperature of the alloy while satisfying the requirement of Cr in stainless steel production. Nonetheless, the gangue composition of chromite is similar to that of magnetite, and no synergistic effects of gangue can be harnessed, which leads to a high liquidus temperature for slag containing 3 wt% FeO and 5 wt% Cr2O3. Co-smelting of chromite and nickel laterite has been reported to produce Fe-Cr-Ni master alloys for stainless steel production. The slag after reduction, mainly composed of MgO, Al2O3, and SiO2, has a high liquidus temperature. Consequently, this process requires either a high smelting temperature or a large amount of SiO2 flux to achieve effective separation of the alloy from the slag [22]. Tian et al. [23] and Laranjo et al. [24] have reported that the synergistic reduction of chromite, nickel laterite, and manganese ore produces an Fe-Cr-Ni-Mn master alloy. The difference between their studies is that Tian et al. used a pre-reduction followed by a smelting process and Laranjo et al. used a direct smelting process. The advantage is that valuable elements in chromite, nickel laterite, and manganese ore have been effectively recovered in a single alloy. Specifically, for the Fe-Cr-Ni-Mn master alloy, Fe is provided by the chromite, nickel laterite, and manganese ore. The Cr, Ni, and Mn in the alloy are provided by the chromite, nickel laterite, and manganese ore, respectively. Nonetheless, due to the limitations of gangue content in the ores and the composition requirements of stainless steel, it is difficult to simultaneously meet both the target composition of the master alloy and a low liquidus temperature of the slag. A smelting temperature of 1600 °C was required to efficiently separate alloy from slag. The key point of the synergy reduction for production of the master alloy of stainless steel is to find a mineral or secondary resource that can simultaneously provide valuable components for the master alloy and flux for the slag. Copper smelting slag is a potential material for synergistic reduction with chromite to produce a master alloy for stainless steel. Copper smelting slag mainly consists of FeO, SiO2, and Cu2O, which can provide SiO2 as a flux for chromite smelting after the reduction of Cu2O and FeO [25,26]. Xu et al. investigated the production of an Fe-Cr-Cu alloy from chromite and copper slag in a two-step process. They used briquettes prepared at 1050 °C for the smelting experiments. The investigated the effects of a temperature between 1500 and 1650 °C, a smelting duration between 20 and 80 min, a CaO/SiO2 ratio between 0.2 and 1.0, and a dosage of coke between 2% and 12%. The recovery rates of Fe, Cr, and Cu were 98.9 wt%, 96.2 wt%, and 95.6 wt%, respectively [27]. The two-step process, including pre-reduction and smelting, significantly increases the capital cost, production costs, and CO2 emissions.

In this study, a single smelting process is proposed at a lower temperature for the production of Cu-Cr-Fe master alloys, using chromite and copper smelting slag. The effects of carbon, smelting temperature, slag composition, and the ratio of chromite to copper smelting slag are investigated through thermodynamic calculations and high-temperature experiments.

2. Raw Materials and Methods

The chemical compositions of the chromite and copper smelting slag used in this study are presented in Table 1. Fe, Cr, Zn, and Cu in the chromite and copper smelting slag are valuable elements that can be recovered during the smelting process. The gangue components in the raw materials form liquid slag.

Table 1.

The chemical compositions of chromite and copper smelting slag (wt%).

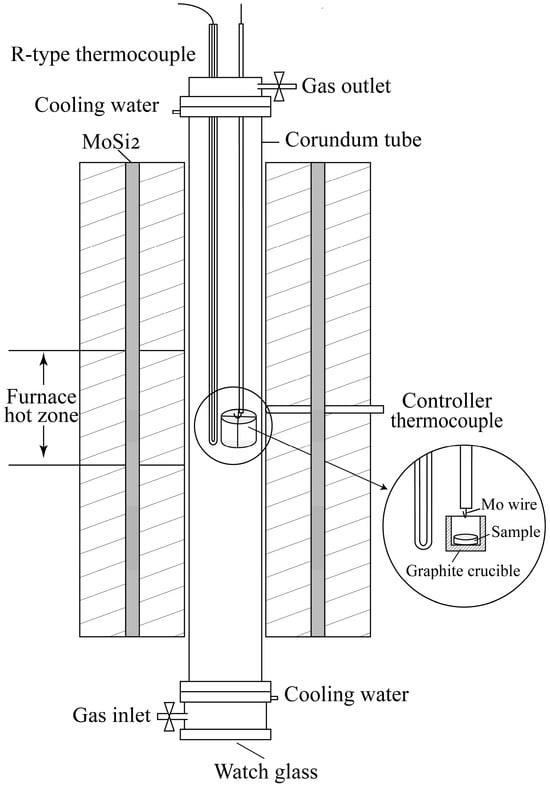

The vertical tube furnace (OTF-1700X, Hefei Kejing Materials Technology Co., Ltd., Hefei, China) employed for the reduction experiments is illustrated in Figure 1. A Pt/Pt-13 wt% Rh thermocouple was placed in the furnace’s hot zone to monitor the reduction temperature. Chromite, copper smelting slag, fluxes, and graphite powders were accurately weighed and mixed using an agate mortar and pestle. The mixture was pelletized and placed in a graphite crucible, which was suspended in the furnace’s hot zone with molybdenum wire. The sample was reacted at the target temperature for a certain time under an inert atmosphere (99.99 wt% Ar). Detailed experimental conditions are shown in Table 2. After the reduction was completed, the graphite crucible was rapidly lowered to the bottom end of the furnace to quickly cool the sample. The Fe, Cr, and Cu contents in the slag and alloy were analyzed using ICP-OES. The carbon and sulfur contents in the alloy were determined by using a carbon–sulfur analyzer. The gangue composition of the slag was analyzed by XRF. The microstructure and phase compositions of the quenched samples were examined by using an EPMA (electron probe microanalyzer, JXA-iSP100, JEOL, Tokyo, Japan).

Figure 1.

Schematic of vertical tube furnace for high-temperature experiments.

Table 2.

The detailed experimental conditions.

The Equilib module in FactSage 8.4 was used to predict the reduction sequence of the valuable components and the liquidus temperature of the slag after reduction. The databases “FactPS”, “FToxid”, and “FTmisc” were selected for the calculations. The solution phases selected for the calculations included “FTmisc-FeLQ”, “FTmisc-CuLQ”, “FTmisc-MATT”, “FTmisc-SPHA”, “FTmisc-WURT”, “FToxid-SLAGA”, “FToxid-SPINA”, “FToxid-MeO_A”, “FToxid-cPyrA”, “FToxid-oPyrA”, “FToxid-pPyrA”, “FToxid-LcPy”, “FToxid-WOLLA”, “FToxid-Bred”, “FToxid-bC2SA”, “FToxid-aC2SA”, “FToxid-Mel_A”, “FToxid-OlivA”, “FToxid-Cord”, “FToxid-Mull”, “FToxid-CORU”, “FToxid-CaSp”, “FToxid-ZNIT”, and “FToxid-WILL”.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Thermodynamic Calculations

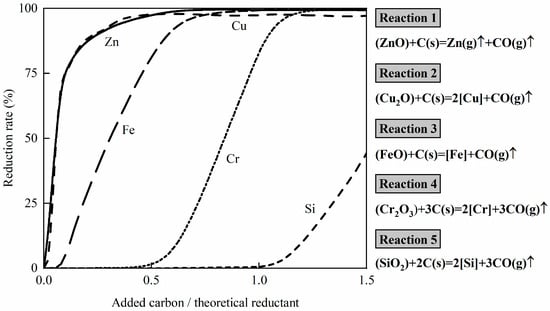

The reduction sequence of FeO, Cr2O3, Cu2O, ZnO, and SiO2 is shown in Figure 2, which was calculated using FactSage 8.4 at 1550 °C. The reactants are 100 g of (50 wt% chromite and 50 wt% copper smelting) with 10 g fluxes (50 wt% CaO and 50 wt% SiO2). The theoretical reductant is the carbon required to fully reduce FeO, Cr2O3, Cu2O, and ZnO, according to Reactions (1)–(4), as follows.

(FeO) + C(s) = [Fe] + CO(g)↑

(Cr2O3) + 3C(s) = 2[Cr] + 3CO(g)↑

(Cu2O) + C(s) = 2[Cu] + CO(g)↑

(ZnO) + C(s) = Zn(g)↑ + CO(g)↑

(SiO2) + 2C(s) = 2[Si] + 3CO(g)↑

Figure 2.

Reduction sequence of FeO, Cr2O3, Cu2O, ZnO, and SiO2 by carbon at 1550 °C, calculated by FactSage 8.4. The reactants are 100 g of 50 wt% chromite and 50 wt% copper smelting ratio, with 10 g fluxes (50 wt% CaO and 50 wt% SiO2).

As observed in Figure 2, ZnO and Cu2O react with carbon first, followed by FeO, Cr2O3, and SiO2. FeO, Cr2O3, and Cu2O are reduced by carbon, forming an Fe-Cr-Cu-C master alloy. ZnO reacts with carbon to produce Zn(g), which can be recovered in the dust. SiO2 in the slag may be reduced to Si by carbon, according to Reaction (5), which dissolved in the Fe-Cr-Cu-C master alloy. Reduction of SiO2 by carbon in the slag changed the composition and liquidus temperature of the slag.

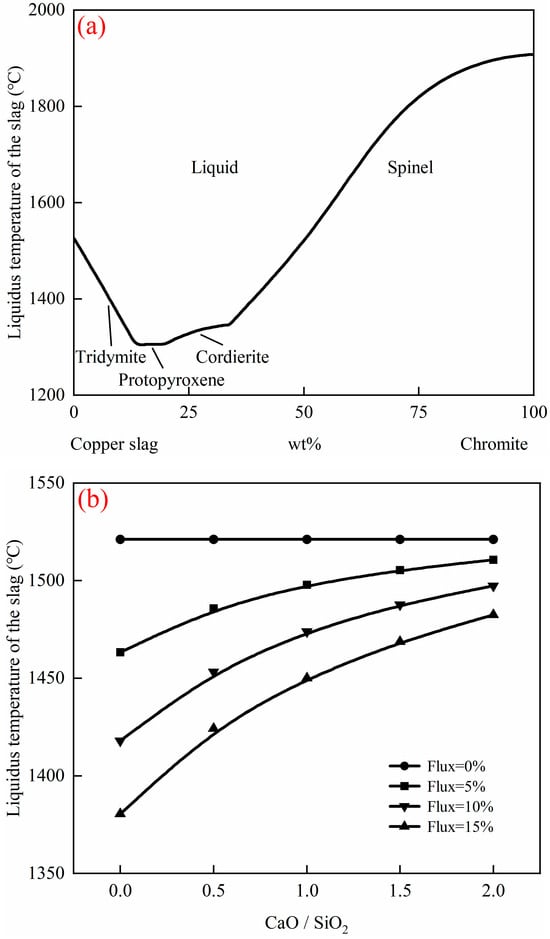

Figure 3 illustrates the effects of the chromite to copper slag ratio in raw materials, fluxes, and the CaO/SiO2 ratio in the flux on the liquidus temperature of the slag, based on the assumption that all Fe, Cu, and Cr have been reduced. As shown in Figure 3a, the liquidus temperature of the slag after reduction is 1525 °C if only copper smelting slag is used, and 1907 °C if only chromite is used. With an increase in the copper smelting slag proportion, the liquidus temperature of the slag decreases in the spinel and cordierite primary phase fields but increases in the tridymite primary phase field. The minimum liquidus temperature of the slag can be reduced to 1304 °C. This confirms that the co-smelting of the chromite and copper smelting slag effectively lowers the liquidus temperature of slag, thereby reducing the smelting temperature and the required flux. The Cr/Cu ratio in the alloy is also a vital factor to consider in co-smelting. The ratio of chromite to copper smelting slag in the feedstock decides the Cr/Cu ratio in the alloy. Taking the composition of type 304 Cu-bearing stainless steel as an example, its Cr/Cu ratio ranges from 4.2 to 6.3 [28,29]. This means that the proportion of copper smelting slag in the feedstock should be controlled between 43 wt% and 53 wt%, with a corresponding liquidus temperature of 1485 °C to 1611 °C. Due to the limitation of the Cr/Cu ratio in the alloy and the high liquidus temperature of Cr2O3-bearing slag, flux (CaO + SiO2) is necessary to add to decrease the liquidus temperature of the slag [30]. Figure 3b presents the effects of fluxes and the CaO/SiO2 ratio in the flux on the liquidus temperature of the slag at a fixed 100 g of 50 wt% chromite and 50 wt% copper smelting slag ratio, calculated by FactSage 8.4. It shows that the liquidus temperature of slag after reduction decreases with fluxes. Specifically, the liquidus temperature of slag after reduction can be decreased to 1380 °C at a fixed 15 wt% flux (with a CaO/SiO2 ratio of 0). As the CaO/SiO2 ratio in the flux increases, the liquidus temperature of the slag after reduction increases correspondingly. This indicates that a higher CaO content in slag raises the liquidus temperature of slag. Although CaO increases the liquidus temperature of slag, it can reduce the sulfur content in the alloy and consequently lowers the alloy’s refining cost.

Figure 3.

Liquidus temperature of the slag after reduction as a function of (a) chromite to copper slag ratio in raw materials and (b) CaO/SiO2 ratio in the flux, calculated by FactSage 8.4, based on 100 g (chromite + copper slag).

3.2. Effect of Carbon

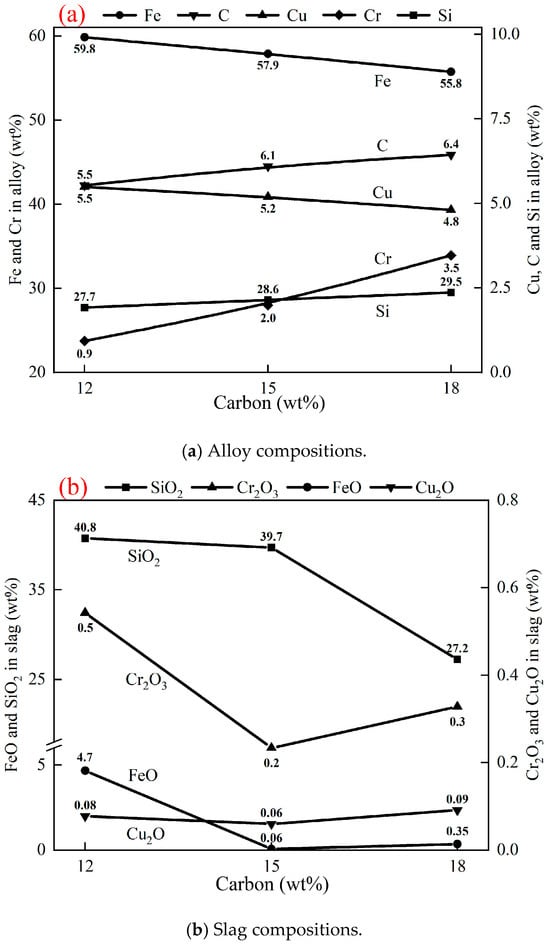

Compositions of slags and alloys after reduction in Exp. 1 to Exp. 3 are shown in Table 3. As shown in Figure 4a, the Fe and Cu contents in the alloy decrease from 59.8 wt% and 5.5 wt% to 55.8 wt% and 4.8 wt%, with a carbon increase from 12 wt% to 18 wt%, respectively. In contrast, the Cr, Si, and C contents increase from 27.7 wt%, 0.9 wt%, and 5.5 wt% to 29.5 wt%, 3.5 wt%, and 6.4 wt%, respectively. This indicates that higher carbon leads to a deeper reduction of Cr2O3 and SiO2 from the slag.

Table 3.

Compositions of slags and alloys after reduction in Exp. 1 to Exp. 3 (wt%).

Figure 4.

Effect of carbon on compositions of alloy and slag after reduction at 1550 °C for 1 h, 20 g of (50 wt% chromite + 50 wt% copper smelting slag), and 2 g fluxes (50 wt% CaO + 50 wt% SiO2).

Figure 4b shows the effect of carbon on the contents of FeO, Cr2O3, and Cu2O in the slag. Increasing carbon from 12 wt% to 15 wt% reduces their contents from 4.7 wt%, 0.5 wt%, and 0.08 wt% to 0.06 wt%, 0.2 wt%, and 0.06 wt%, respectively. However, at 18 wt% carbon, the contents of FeO, Cr2O3, and Cu2O in the slag increase to 0.35 wt%, 0.3 wt%, and 0.09 wt%, respectively, which is the result of SiO2 reduction. Reduction of SiO2 by carbon changed the composition and properties of the slag, resulting in difficulty in completely separating the alloy from the slag.

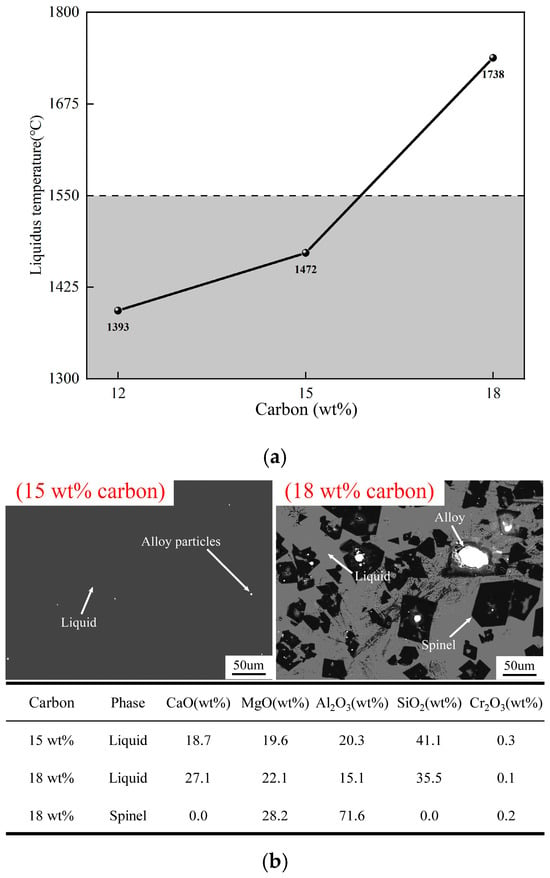

Figure 5a shows the effect of carbon on the liquidus temperature of slag after reduction. The liquidus temperature of the slag after reduction was calculated by using FactSage 8.4, based on the slag compositions determined by ICP-OES and XRF. As the carbon increases from 12 wt% to 18 wt%, the liquidus temperature of the slag rises from 1393 °C to 1738 °C. The reaction between SiO2 and carbon results in a significant increase in the liquidus temperature of slag after reduction. Figure 5b illustrates the microstructure of the quenched sample at fixed 15 wt% and 18 wt% carbons, respectively. Figure 5b shows that when the SiO2 content in the slag is 41.1 wt%, the slag is a pure liquid without a solid phase, indicating that the liquidus temperature of slag is lower than the smelting temperature of 1550 °C. The slag and alloy are completely separated. The small pieces of alloy are formed upon cooling. On the contrary, a large amount of spinel phase (MgO·Al2O3) and large-sized alloy particles are present in the slag. The existence of spinel phase in slag significantly increases the slag’s bulk viscosity, resulting in incomplete separation of the alloy from the slag.

Figure 5.

Effect of carbon on (a) liquidus temperature of the slag after reduction, calculated by FactSage 8.4 and (b) microstructures and phase compositions of the samples after reduction with 15 wt% and 18 wt% carbon.

3.3. Effect of Smelting Temperature

Temperature affects the reduction in chromite and copper smelting slag in two aspects: one is the reduction extent, and the other is the viscosity of the slag. Table 4 shows compositions of slags and alloys in Exp. 4 and Exp. 5. Figure 6 illustrates the effect of the smelting temperature on the compositions of the slag and alloy.

Table 4.

Compositions of slags and alloys after reduction in Exp. 4 and Exp. 5 (wt%).

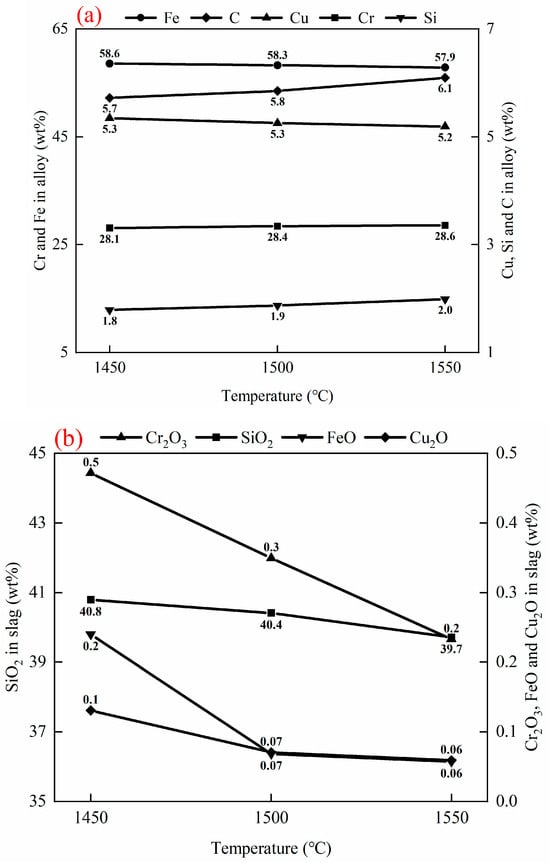

Figure 6.

Effect of smelting temperature on compositions of alloy and slag after reduction, 20 g of (50 wt% chromite + 50 wt% copper smelting slag), 2 g fluxes (50 wt% CaO + 50 wt% SiO2), and 3 g carbon. (a) Alloy compositions. (b) Slag compositions.

As can be seen from Figure 6a, the Fe/Cu ratio in the alloy remains constant as the smelting temperature increases, indicating that nearly all Cu2O and FeO have reacted with carbon above 1450 °C. When the temperature increases from 1450 °C to 1550 °C, the Cr and Si content in the alloy increases from 28.1 wt% and 1.8 wt% to 28.6 wt% and 2.0 wt%, indicating that more Cr2O3 and SiO2 are reduced at a higher temperature. This is also confirmed by the Cr2O3 and SiO2 contents in the slag, which decrease from 0.5 wt% and 40.8 wt% to 0.2 wt% and 39.7 wt%, respectively, as the smelting temperature increases from 1450 °C to 1550 °C. In addition, more carbon is dissolved in the alloy as the smelting temperature rises.

3.4. Effect of (CaO + MgO)/(Al2O3 + SiO2) in Slag

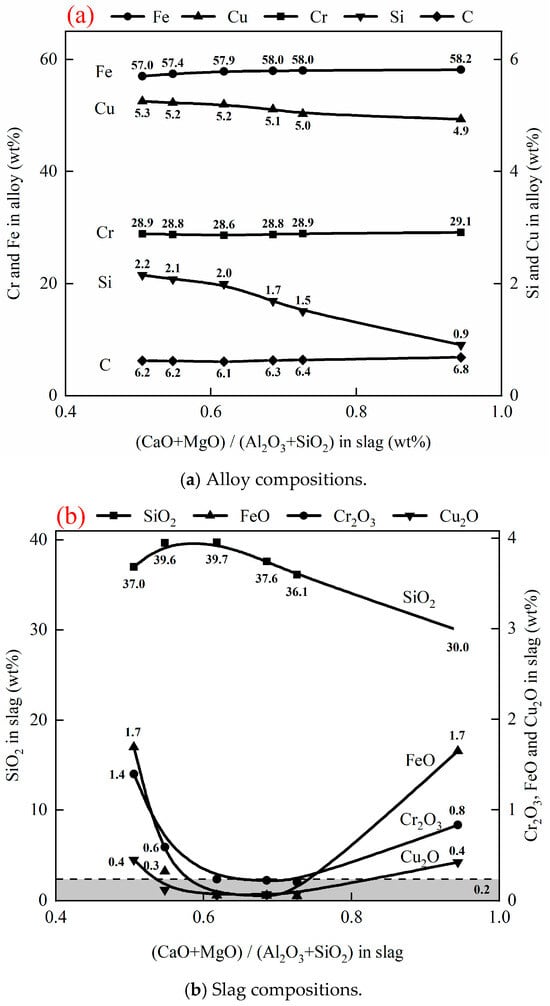

Quaternary basicity (CaO + MgO)/(Al2O3 + SiO2) is commonly used to characterize the slag property. Table 5 shows compositions of slags and alloys in Exp. 6 to Exp. 10 after reduction. Figure 7 shows the effect of slag basicity on the compositions of slag and alloy at 1500 °C, fixed 20 g of 50 wt% chromite and 50 wt% copper smelting slag ratio, 3 g of carbon, and 1 h. As can be seen from Figure 7a, the Fe, Cr, and C contents in the alloy increase, while the Cu and Si contents decrease, increasing the (CaO + MgO)/(Al2O3 + SiO2) ratio in the slag. A higher (CaO + MgO)/(Al2O3 + SiO2) ratio in the slag increases the activities of Cr2O3 and FeO, resulting in more Cr2O3 and FeO being reduced. The reduction of Cu2O by carbon is much easier than that of Fe2O3 and Cr2O3. Therefore, nearly all Cu2O in the slag is reduced to Cu at an early stage of the reaction. The increased Fe, C, and Cr contents in the alloy dilute the Cu content in the alloy. With an increase in the (CaO + MgO)/(Al2O3 + SiO2) ratio, the activity of SiO2 in the slag decreases and less SiO2 is reduced by carbon. As can be seen from Figure 7b, the contents of Cr2O3, FeO, and Cu2O first decrease and then increase with an increase in (CaO + MgO)/(Al2O3 + SiO2). This phenomenon can be explained by the extent of separation between the slag and alloy.

Table 5.

Compositions of slags and alloys after reduction in Exp. 6 to Exp. 10 (wt%).

Figure 7.

Effect of quaternary basicity on compositions of alloy and slag after reduction at 1500 °C for 1 h, with 20 g of (50 wt% chromite + 50 wt% copper smelting slag), and 3 g carbon.

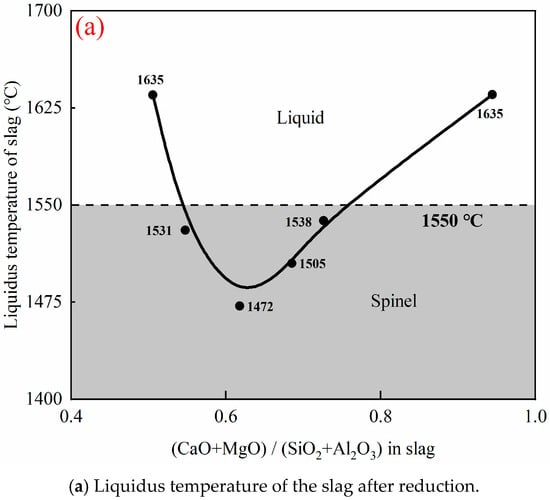

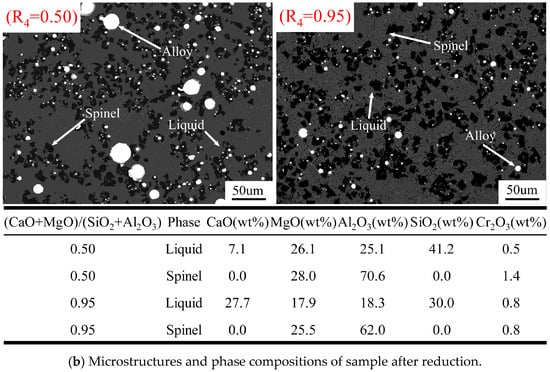

Figure 8a shows the effect of quaternary basicity on the liquidus temperature of slag after reduction. The liquidus temperature of the slag after reduction was calculated using FactSage 8.4, based on the slag compositions. As shown in Figure 8a, when the quaternary basicity is too low or too high, the liquidus temperature of the slag exceeds the smelting temperature. The presence of a solid phase at the smelting temperature significantly increases the bulk viscosity of the slag and influences the separation of the alloy from the slag. The microstructure of a quenched slag with a (CaO + MgO)/(SiO2 + Al2O3) ratio of 0.5 confirmed that many alloy droplets are entrained in the slag, together with the spinel particles. Therefore, it is important to ensure that the smelting temperature is higher than the liquidus temperature of the slag. Once the solid phase appears in the slag, its bulk viscosity increases sharply, causing a difficult settlement of the alloy in the slag. This indicates that the alloy cannot be effectively separated from the slag when the (CaO + MgO)/(SiO2 + Al2O3) ratio in the slag is either too high or too low.

Figure 8.

Effect of quaternary basicity on (a) liquidus temperature of the slag after reduction, calculated by FactSage 8.4 and (b) microstructures and phase compositions of the quenched sample with 0.50 and 0.95 (CaO + MgO)/(SiO2 + Al2O3) in slag after reduction.

3.5. Effect of Chromite to Copper Slag Ratio in Raw Materials

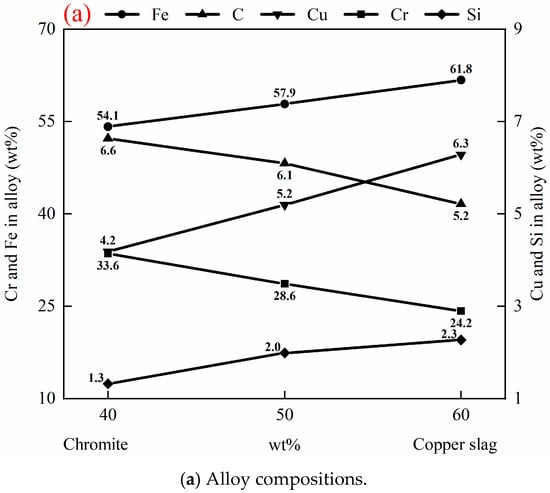

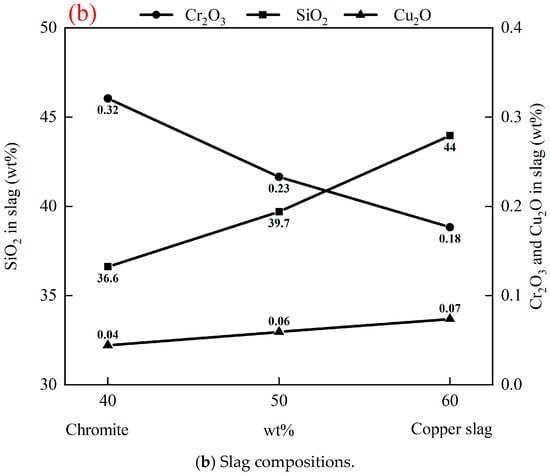

The chromite to copper slag ratio in raw materials determines the Fe, Cr, and Cu contents in the alloy. Figure 9 illustrates the effect of the chromite to copper slag ratio in raw materials on the compositions of the alloy and slag after reduction, at 1550 °C, with 20 g of (chromite and copper smelting slag), 3 g carbon, 2 g fluxes (50 wt% CaO and 50 wt% SiO2), and 1 h. Table 6 shows compositions of slags and alloys after reduction in Exp. 11 and Exp. 12. As shown in Figure 9a, the Fe, Cu, and Si contents in the alloy increase with an increase in the proportion of copper smelting slag. This is because the Fe, Cu, and Si contents are higher in copper smelting slag than those in chromite. Conversely, the Cr content in the alloy decreases as the proportion of copper smelting slag increases, due to decreased Cr2O3 in the raw material. Decreased carbon content in the alloy is attributed to a decrease in the Cr content and an increase in the Si content in the alloy. As depicted in Figure 9b, with an increased proportion of copper smelting slag, the Cu2O content increases and Cr2O3 content decreases in the slag. A lower Cu2O or Cr2O3 content in the slag means higher recovery of these elements in the alloy. This observation confirms the advantage of the synergistic reduction of copper smelting slag and chromite. The addition of copper smelting slag into chromite increases the recovery of Cr. On the other hand, addition of chromite into copper smelting slag increases the recovery of Cu.

Figure 9.

Effect of chromite to copper slag ratio in raw materials on compositions of alloy and slag after reduction, at 1550 °C for 1 h, with 20 g of (chromite + copper smelting slag), 3 g carbon, and 2 g fluxes (50 wt% CaO + 50 wt% SiO2).

Table 6.

Compositions of slag and alloy in Exp. 11 and Exp. 12 (wt%).

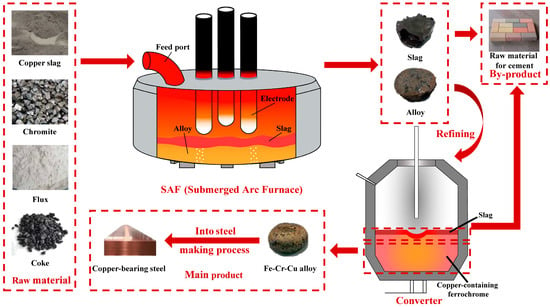

3.6. Production Flowsheet of Master Alloy

Based on the research concepts and experimental findings of this study, a novel technological process for the co-smelting of chromite and copper smelting slag has been established, as illustrated in Figure 10. This process consists of smelting and refining stages. In the smelting stage, chromite and copper smelting slag react with carbon in an electric arc furnace to produce an Fe-Cr-Cu alloy and a CaO-SiO2-MgO-Al2O3 slag. As shown in Table 3, the (CaO + MgO)/(SiO2 + Al2O3) is 0.62 in the slag. The Fe, Cu, and Cr recoveries are 99.9 wt%, 99.2 wt%, and 99.6 wt%, respectively. The slag after reduction can be sold as a raw material for cement production. The alloy containing sulfur must be refined in a standard process and the desulfurized Fe-Cr-Cu alloy can be used as a raw material for the production of Cu-containing stainless steel. Using a calcium-containing alloy as the desulfurizer and a CaO-Al2O3 system as the refining slag, the sulfur content in the Fe-Cr-Cu alloy can be reduced from 0.2 wt% to 0.002 wt%.

Figure 10.

Flowsheet for production of Fe-Cr-Cu alloy using chromite and copper smelting slag.

4. Conclusions

An innovative process is proposed for producing stainless steel master alloys through synergistic reduction in chromite and copper smelting slag. The effects of carbon addition, the smelting temperature, quaternary basicity in slag, and the ratio of chromite to copper smelting slag on synergistic reduction have been investigated.

- (1)

- An Fe-Cr-Cu alloy containing 57.9 wt% Fe, 28.6 wt% Cr, and 5.2 wt% Cu was produced at 1550 °C, fixed 3 g carbon, 20 g of 50 wt% chromite and 50 wt% copper smelting slag, 2 g fluxes (50 wt% CaO and 50 wt% SiO2), and 1 h. The recovery rates of Fe, Cr, and Cu reached 99.9 wt%, 99.2 wt%, and 99.6 wt%, respectively, while the contents of FeO, Cu2O, and Cr2O3 in the slag were reduced to 0.057 wt%, 0.059 wt%, and 0.23 wt%, respectively.

- (2)

- Increasing the smelting temperature and carbon promotes the reduction reactions of FeO, Cr2O3, Cu2O, and SiO2. The liquidus temperature of the slag rises with the reduction of SiO2, and the slag viscosity increases significantly once solid phases appear, resulting in less effective separation between the slag and alloy.

- (3)

- The effect of the slag composition on synergy reduction is sufficiently expressed via quaternary basicity. The suitable range of quaternary basicity is between 0.62 and 0.72. If the quaternary basicity is lower than 0.62 or higher than 0.72, a significant increase in the apparent viscosity of the slag occurs due to the appearance of a solid phase, which in turn results in less effective separation between the slag and alloy.

- (4)

- Through the synergistic reduction of chromite and copper smelting slag, the Cr and Cu contents in the alloy are decreased, which promotes the reduction of Cr2O3 and Cu2O and decreases the contents of Cr2O3 and Cu2O in the slag.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.Z. and S.X.; Methodology, Y.X. and Y.Q.; Software, B.Z.; Validation, S.X. and Y.Q.; Formal analysis, J.L.; Investigation, Y.X. and Y.Q.; Resources, B.Z.; Data curation, Y.X.; Writing—original draft, Y.X.; Writing—review and editing, S.X., B.Z. and J.L.; Visualization, Y.X. and Y.Q.; Supervision, S.X. and J.L.; Project administration, S.X. and B.Z.; Funding acquisition, S.X. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by The Jiangxi Province Training Program for Young Science-Technology Talents in Early Career (No. 20252BEJ730224).

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Yi Qu was employed by Jinxin Copper Branch of Tongling Nonferrous Metals Group Co., Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Cao, S.Y.; Du, C.M.; Wang, Z.J. High temperature co-processing of stainless-steel slag and red mud: Towards a selective Cr immobilization and harmless treatment. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 500, 156956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mushtaq, M.; Ramesh, B. A novel investigation on effect of process parameters on surface roughness while drilling normalized and annealed SAE 304 stainless steel and comparing the outputs with untreated stainless steel. Mater. Today Proc. 2024, 69, 980–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, P.; Åkerfeldt, P.; Svahn, F.; Nilsson, E.; Forouzan, F.; Antti, M.L. Microstructural characterization and mechanical properties of additively manufactured 21-6-9 stainless steel for aerospace applications. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2023, 25, 1483–1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozturk, M.C.; Coghlan, L.; Zimina, M.; Akid, R.; Martin, T.L.; Larrosa, N.O. Corrosion behaviour of 316L stainless steel under stress in artificial seawater droplet exposure at elevated temperature and humidity. Corros. Sci. 2025, 254, 113039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.F.; Cashell, K.A.; Angelakopoulos, H.; Huang, S.S. Assessment of fire-induced spalling in stainless steel reinforced concrete with recycled steel tyre microfibres. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 485, 141803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charles, J.; Mithieux, J.D.; Krautschick, J.; Suutala, N.; Antonio, J.; Van, B.; Pauly, T. A new European 200 series standard to substitute 304 austenitics. Metall. Res. Technol. 2009, 106, 90–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.K.; Wu, S.W.; Yu, J.; Zhang, Y.L. Optimizing chromite reduction through carbon and hydrogen synergy. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 73, 566–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.Z.; Hu, H.; Yang, S.; Wang, S.; Chen, F.; Guo, Y.F. Life cycle carbon footprint of electric arc furnace steelmaking processes under different smelting modes in China. Sustain. Mater. Technol. 2023, 35, e00564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.W.; Zhuang, C.L.; Liu, J.H.; Shen, S.B.; Ji, Y.L.; Han, Z.B. Smelting and casting technologies of Fe-25Mn-3Al-3Si twinning induced plasticity steel for automobiles. J. Iron Steel Res. Int. 2015, 22, 75–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.; Patra, S.K.; Tripathy, S.K.; Sahu, N. Efficient utilization of nickel rich Chromite Ore Processing Tailings by carbothermic smelting. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 315, 128046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berryman, E.J.; Paktunc, D.; Kingston, D.; Beukes, J.P. Composition and Cr- and Fe-speciation of dust generated during ferrochrome production in a DC arc furnace. Clean. Eng. Technol. 2022, 6, 100386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamuyuni, J.; Johto, H.; Bunjaku, A.; Vatanen, S.; Pajula, T.; Mäkelä, P.; Lindgren, M. Simulation-based life cycle assessment of ferrochrome smelting technologies to determine environmental impacts. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 295, 126503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, F.; Zhao, Z.; Zhang, Y.L.; Wu, T. Effect of Al2O3 content on the viscosity and structure of CaO-SiO2-Cr2O3-Al2O3 slags. Int. J. Miner. Met. Mater. 2022, 29, 1522–1531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Li, B.K.; Liu, Z.Q.; Qi, F.S.; Liu, C.J.; Rong, W.J.; Kuang, S.B. Analysis of Electrical Energy Consumption in a Novel Direct Current Submerged Arc Furnace for Ferrochrome Production. Met. Mater. Trans. B 2023, 54, 2370–2382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.H.; Li, L.L.; Li, M.M.; Bao, W.W.; Song, Y.H.; Gan, S.C.; Zhou, H.F.; Xu, X.C. Hydrothermal synthesis and luminescent properties of NaLa(MoO4)2: Eu3+,Tb3+ phosphors. J. Alloys Compd. 2013, 550, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdem, M.; Altundoğan, H.S.; Turan, M.D.; Tümen, F. Hexavalent chromium removal by ferrochromium slag. J. Hazard. Mater. 2005, 126, 176–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, F.Q.; Zhang, Y.B.; Su, Z.J.; Tu, Y.K.; Liu, S.; Jiang, T. Recovery of chromium from chromium-bearing slags produced in the stainless-steel smelting: A review. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 296, 126467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Lv, X.; Xu, J.; Zhang, S.; Bai, C. Preparation of stainless steel master alloy by direct smelting reduction of Fe-Ni-Cr Sinter at 1600 °C. Ironmak. Steelmak. 2016, 43, 600–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spooren, J.; Kim, E.; Horckmans, L.; Broos, K.; Nielsen, P.; Quaghebeur, M. In-situ chromium and vanadium recovery of landfilled ferrochromium and stainless steel slags. Chem. Eng. J. 2016, 303, 359–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, J.; Schewel, L.; Graedel, T.E. The Contemporary Anthropogenic Chromium Cycle. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2006, 40, 7060–7069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, D.Q.; Yang, C.C.; Pan, J.; Lu, L.M.; Guo, Z.Q.; Liu, X.Q. An integrated approach for production of stainless steel master alloy from a low grade chromite concentrate. Powder Technol. 2018, 335, 103–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, I.H.; Decterov, S.A.; Pelton, A.D. Critical thermodynamic evaluation and optimization of the MgO-Al2O3, CaO-MgO-Al2O3, and MgO-Al2O3-SiO2 Systems. J. Phase Equilibria Diffus. 2024, 25, 329–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, H.Y.; Chu, M.S.; Pan, J.; Zhu, D.Q.; Yang, C.C.; Tang, J. Smelting characteristics of nickel-chromium-manganese bearing prereduced pellets for the preparation of nickel saving austenite stainless steel master alloys. Powder Technol. 2024, 441, 119862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laranjo, R.D.; Anacleto, N.M. Direct smelting process for stainless steel crude alloy recovery from mixed low-grade chromite, nickel laterite and manganese ores. J. Iron Steel Res. Int. 2018, 25, 515–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, Y.; Tan, K.Q.; Zhao, B.J.; Xie, S. Recovery of Cu-Fe Alloy from Copper Smelting Slag. Metals 2023, 13, 271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, Y. Basic Study on the Preparation of Fe-Cr-Cu Intermediate Alloy by Synergistic Reduction of Copper Slag and Chromite ore. Master’s Thesis, Jiangxi University of Science and Technology, Ganzhou, China, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Z.; Guo, Z.Q.; Xu, X.Q.; Yan, B.K.; Zhu, D.Q.; Pan, J.; Yang, C.C.; Li, S.W.; Huang, X.Z. Green production of Fe-Cr-Cu master alloys via electric smelting of pre-reduced briquettes prepared from copper slag and chromite. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2025, 37, 1822–1833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, L.; Nan, L.; Yang, K. Study of copper precipitation behavior in a Cu-bearing austenitic antibacterial stainless steel. Mater. Des. 2011, 32, 2374–2379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.J.; Nan, L.; Xu, D.K.; Ren, G.G.; Yang, K. Antibacterial Performance of a Cu-bearing Stainless Steel against Microorganisms in Tap Water. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2015, 31, 243–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, J.F.; Zhao, B.J. Effects of Al2O3 and “Cr2O3” on phase equilibria of the system “FeO”-MgO-SiO2 at iron saturation. Calphad 2021, 75, 102343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.