Abstract

Cr8 steel should be Steel containing ~8 wt.% of chromium is widely used in demanding die applications due to its excellent wear resistance; however, conventional shot peening, while enhancing strength, inevitably increases surface roughness, thereby compromising overall performance. To address this limitation, this study systematically investigates the influence of ultrasonic surface rolling (USR) step size—comparing 0.06 mm and 0.12 mm—on mitigating surface degradation and improving surface integrity. Friction wear and electrochemical corrosion tests demonstrate that USR effectively reduces surface roughness and enhances microhardness. The 0.06 mm step size achieves superior results, yielding the lowest surface roughness (0.8317 μm), highest microhardness (647.47 HV), lowest friction coefficient (0.655), and optimal corrosion resistance (minimum corrosion rate reduction: 3.472 µA·cm−2, corresponding to an inhibition efficiency of 37.05%). These performance improvements are attributed to the synergistic effects of surface smoothing and work hardening, resulting from more uniform processing achieved under a smaller step size. Consequently, a 0.06 mm step size is determined to be optimal, establishing the integrated shot peening–USR process as a highly effective strategy for enhancing surface properties and extending the service life of critical Cr8 steel components in industrial applications.

1. Introduction

Cr8 steel is widely used in the manufacture of various cold-working dies, including punching and blanking dies for electronic components and household appliance parts, drawing dies for tableware and enclosures, and forming dies for cold extrusion and bending. It is also commonly employed in critical tooling applications such as cold heading dies for screws and bolts, thread rolling dies, and powder metallurgy pressing dies [1]. A key advantage of Cr8 steel lies in its exceptional wear resistance. After quenching and low-temperature tempering, its microstructure features a fine dispersion of carbide hard phases, achieving a hardness range of HRC 58–62 [2]. This high hardness effectively resists abrasive wear during stamping and drawing operations, thereby significantly extending die service life [3]. Furthermore, due to its optimized chromium content, Cr8 steel exhibits excellent hardenability, ensuring uniform hardness distribution even in large cross-sectional components, which contributes to consistent performance across the entire part [4].

To further enhance surface performance and prolong service life, mechanical shot peening is frequently applied to Cr8 steel. This process involves high-velocity impacts of spherical media that generate a plastically deformed layer and introduce compressive residual stresses [5], thereby improving both wear resistance and high-cycle fatigue performance. For example, Zhang et al. [6] demonstrated that shot peening a Cr-Ni-Mo high-strength steel increased surface roughness, which promoted lubricant retention and simultaneously reduced the friction coefficient and wear rate. Wagner [7] showed that introducing compressive residual stresses via shot peening into Al 7075-T73 and Ti-6Al-4V alloys effectively retarded fatigue-crack initiation and propagation while significantly enhancing high-cycle fatigue strength. Similarly, Duan [8] observed severe surface plastic deformation in shot-peened 7B50 aluminum alloy, accompanied by dislocation multiplication and grain refinement, resulting in a 28% increase in surface hardness.

However, improper peening parameters can degrade surface quality. Gao [9] reported that shot peening introduced surface pits on 7B50-T7751 aluminum, and excessive coverage led to folds and micro-cracks that acted as stress concentrators and facilitated fatigue-crack nucleation. Therefore, a secondary surface treatment capable of mitigating surface defects while preserving the beneficial subsurface microstructure is essential to further improve overall performance and reliability.

USR has recently emerged as a promising finishing technique that combines static force with ultrasonic vibration [10]. This process enhances surface integrity through simultaneous reduction in surface roughness, refinement of the microstructure, and introduction of beneficial compressive residual stress fields [11]. For instance, Zhang et al. [12] reported that USR treatment of 45 carbon steel resulted in increased surface hardness, improved wear resistance, lower surface roughness, and enhanced grain refinement. Similarly, Ye et al. [13] observed that USR induced severe plastic deformation in AZ31B Mg alloy, producing dense dislocations and nanoscale grains, leading to significantly enhanced hardness. In the case of uranium, Liu et al. [14] found that USR improved corrosion resistance by forming a compact and continuous protective oxide film that effectively hindered oxygen diffusion. Moreover, Yang et al. [15] demonstrated that the compressive residual stresses induced by USR in GH419 superalloy significantly improved its high-cycle fatigue performance. Collectively, these studies confirm the remarkable capability of USR in enhancing surface integrity. Owing to its simplicity, cost-effectiveness, and high efficiency, USR holds broad potential for industrial applications.

The integration of shot peening and USR represents a synergistic strategy to overcome the limitations of each individual process. Zhang et al. [16] applied this hybrid approach to 17Cr2Ni2MoVNb steel and demonstrated that the pre-existing compressive layer and deformation zone induced by shot peening amplified the effectiveness of subsequent USR, leading to further improvements in wear resistance. Similarly, Duan et al. [17] applied sequential shot peening and USR to AISI 52100 bearing steel, showing that the combined process yielded a finer grain structure and higher surface hardness than either method alone.

USR is a multi-parameter process whose outcomes are governed by the synergistic interaction of variables such as static force, amplitude, and number of rolling passes. While the effects of these parameters have been extensively studied, a critical yet underexplored factor—step distance—directly influences track overlap, surface coverage, and ultimately, the uniformity of plastic deformation. A comprehensive review of existing USR literature reveals a significant methodological gap: step distance is often held constant (e.g., [13,15]), arbitrarily selected without justification, or coupled with other parameters in experimental designs, thereby obscuring its independent and quantitative contribution to surface integrity [18,19]. This omission is nontrivial, as it hinders the development of predictive, quantitative relationships between step distance and key performance indicators such as surface roughness (Ra), microhardness gradient (ΔHV), and corrosion rate reduction (icorr). Consequently, for composite processes like “shot peening + USR”—where the pre-deformed substrate presents a unique initial state—there remains no validated processing window or mechanistic model to guide the rational selection of step distance for simultaneously optimizing tribological performance and corrosion resistance. To address this critical knowledge gap, the present study systematically evaluates the influence of USR step distance (0.06 mm vs. 0.12 mm) on shot-peened Cr8 steel. By isolating this parameter, we aim to (i) elucidate its individual effect on wear and corrosion behavior, (ii) establish robust quantitative correlations between step distance and surface characteristics, and (iii) clarify the underlying synergistic mechanisms in the integrated strengthening process. The results are expected to provide a foundational, data-driven framework for fabricating gradient-strengthened surfaces with balanced mechanical strength and enhanced electrochemical durability.

2. Experimental Details

2.1. Sample Preparation

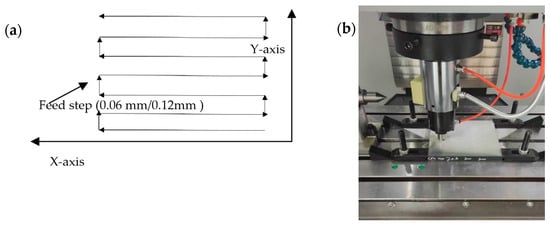

Cr8 steel plates, with the chemical composition listed in Table 1, were initially ground and then subjected to shot peening using the parameters specified in Table 2. Subsequently, USR was performed using a Huayun HYAFM-850 (Huayun New Material Co., Ltd., Binzhou, China) megasonic device equipped with a hardened tungsten carbide-cobalt (WC-Co) spherical tool tip having a 3 mm radius. The static force, a critical process parameter, was precisely calibrated to 250 N using an in-line piezoelectric sensor (Huayun New Material Co., Ltd., Binzhou, China) and maintained constant throughout the operation via regulated air pressure (0.2 MPa). The remaining USR parameters were set as follows: vibration frequency of 28 kHz and traverse speed of 600 mm·min−1. A single rolling pass was applied under each condition. The treated area on each sample measured 30 mm × 30 mm and was fully covered by a zigzag scanning path with a fixed step-over distance of either 0.06 mm or 0.12 mm [20], ensuring complete and uniform surface coverage. The corresponding tool path schematic and an operational photograph are shown in Figure 1a and Figure 1b, respectively.

Table 1.

Composition of chromium steel plate.

Table 2.

Constant Parameters of the Shot Peening Process.

Figure 1.

Schematic and experimental setup of USR. (a) Schematic of the USR scanning path, illustrating the tool trajectory and the step-over distance (b) USR apparatus.

Test specimens measuring 10 mm × 10 mm × 10 mm were prepared by wire electrical discharge machining. These specimens were then sequentially ground with SiC abrasive papers of 800, 1000, and 2000 grit, followed by final polishing on a velvet cloth using a 2.5 μm diamond suspension.

2.2. Surface Roughness

The surface roughness of the treated Cr8 steel plates was measured using a handheld roughness tester (SJ210, Mitutoyo Corporation, Kanagawa, Japan) to evaluate the influence of USR parameters on surface morphology. For each parameter set, measurements were conducted along both the rolling direction and its perpendicular direction. In each orientation, ten readings were taken at 5 mm intervals, and the average value was calculated to represent the surface roughness in that specific direction.

2.3. Mechanical Properties

Microhardness measurements were conducted using an HXD-1000TMJC micro-Vickers hardness tester (Shanghai TaiMing Optical Instrument Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China) with a load of 4.903 N (500 gf) and a dwell time of 15 s.

Dry sliding wear tests were performed at ambient temperature using a TBT-M5000 reciprocating ball-on-flat tribometer (Beijing TBT Tribology Test Equipment Co., Ltd., Beijing, China). A zirconia (ZrO2) ball with a diameter of 10 mm was used as the counterbody. The tests were carried out in linear reciprocating motion under the following conditions: a normal load of 30 N, a frequency of 2 Hz, and a duration of 60 min. The resulting wear scars were then analyzed using a Zeiss Smartproof 5 white-light confocal microscope (Carl Zeiss AG, Oberkochen, Germany) to measure their width, depth, and volume.

2.4. Electrochemical Measurements

Corrosion behavior was evaluated using a Metrohm Autolab PGSTAT302N potentiostat (Metrohm AG, Herisau, Switzerland). The samples were electrically connected and cold-mounted in epoxy resin to expose a square surface area of 10 mm × 10 mm. A conventional three-electrode electrochemical cell was employed, with the sample serving as the working electrode, a platinum foil as the counter electrode, and a saturated calomel electrode (SCE, filled with saturated KCl solution) as the reference electrode. The electrolyte was a 3.5 wt% NaCl solution maintained at ambient temperature. After stabilizing the open-circuit potential (OCP) for 30 min, potentiodynamic polarization curves were recorded from −0.2 V to +0.7 V relative to OCP at a scan rate of 1 mV·s−1. Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) measurements were conducted at the OCP over a frequency range of 105 to 10−2 Hz with a 10 mV sinusoidal perturbation, using a frequency sweep rate of 0.05 octaves per decade. All experiments were performed at a controlled temperature of 25 °C. Polarization and impedance data were analyzed using Nova 2.1 software, and the EIS spectra (Metrohm AG, Herisau, Switzerland) were fitted to an appropriate equivalent circuit model using ZView 3.1.

2.5. Residual Stress and EBSD Testing

To quantitatively evaluate the effect of USR on surface mechanical properties, surface residual stress measurements were conducted on samples under different processing conditions using a Huayun HK21B (Huayun New Material Co., Ltd., Binzhou, China) residual stress tester. Each sample was measured three times, and the average value was calculated to enhance data reliability.

To investigate the grain refinement phenomenon, the samples were characterized using electron backscatter diffraction (EBSD) in conjunction with a scanning electron microscope operated at low acceleration voltage and short working distance, supplemented by a high-sensitivity backscattered electron detector to improve signal resolution and orientation indexing accuracy.

3. Experimental Results

3.1. Surface Integrity Characterization

3.1.1. Surface Quality Parameters

As shown in Table 3, the sample hardness gradually increases with decreasing processing step-over distance, while surface roughness correspondingly decreases. Specifically, the unprocessed sample exhibits surface roughness values of 2.6472 µm and 0.83158 µm in the X and Y directions, respectively, with an average hardness of 611.04 HV. When the step-over distance is reduced to 0.12 mm, the surface roughness decreases to 1.6621 µm (X direction) and 0.47245 µm (Y direction), and the average hardness increases to 629.93 HV. Further reducing the step-over distance to 0.06 mm leads to additional reductions in surface roughness to 0.8317 µm (X direction) and 0.30207 µm (Y direction), along with an increase in average hardness to 647.47 HV.

Table 3.

Surface roughness and microhardness of shot-peened Cr8 steel after USR treatment with different step distances.

3.1.2. Residual Stress

As shown in Table 4, the absolute value of residual compressive stress increases as the processing step decreases. Specifically, the residual compressive stress in the unprocessed sample is −195 ± 35 MPa, which increases to −926 ± 43 MPa at a processing step size of 0.12 mm, and further rises to −1208.3 ± 56 MPa at a step size of 0.06 mm.

Table 4.

Residual stress in samples subjected to different step distances.

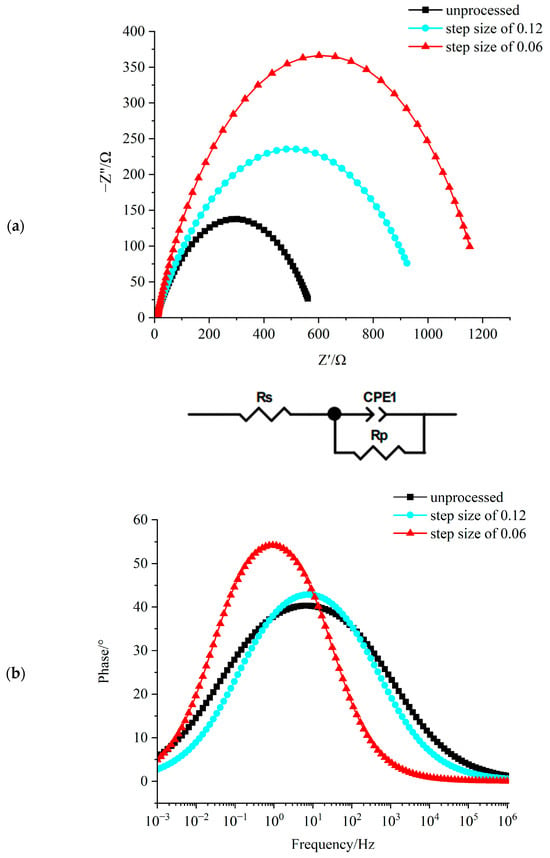

3.1.3. EBSD

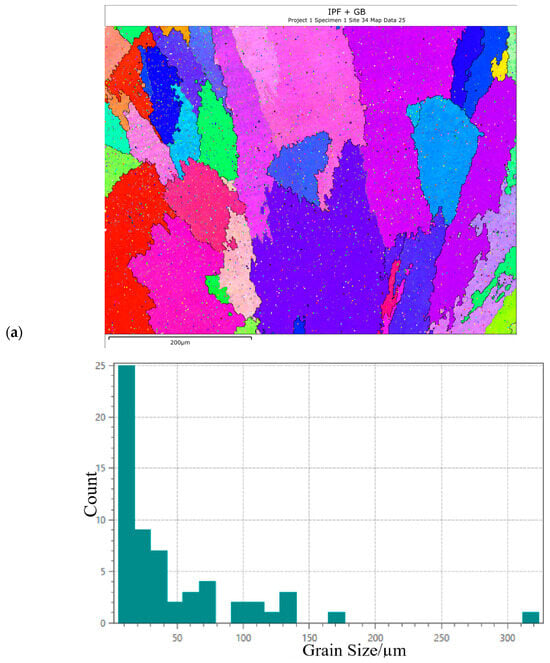

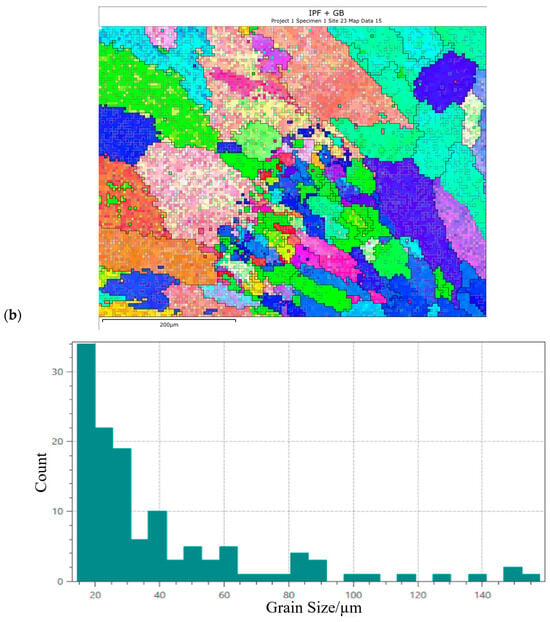

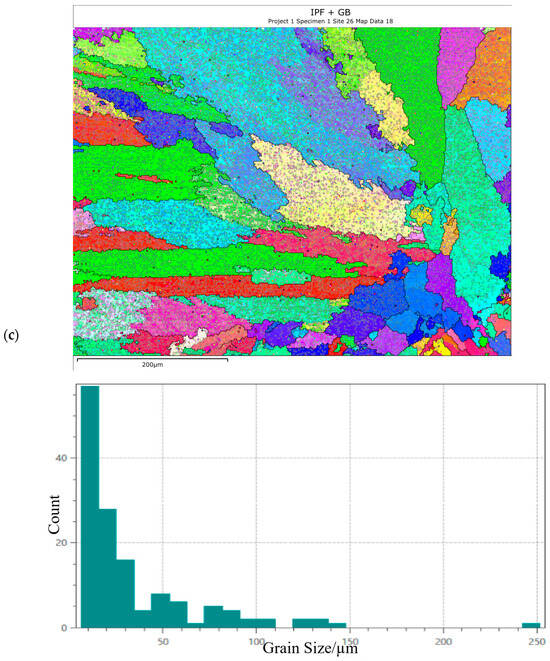

EBSD measurements were conducted on the samples using a scanning electron microscope (Hitachi High-Technologies Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) operated at low acceleration voltage and short working distance, in combination with a high-sensitivity backscattered electron detector. As illustrated in Figure 2, the grain size progressively refined with decreasing processing step distance: the untreated sample exhibited an average grain size of 44.3 μm; when the step distance was 0.12 mm, the average grain size decreased to 39.4 μm; when reducing the step distance to 0.06 mm led to additional grain refinement, achieving an average grain size of 32.3 μm.

Figure 2.

EBSD micrographs and grain size distribution maps under different step distances: (a) unprocessed, (b) step size of 0.12 mm, (c) step size of 0.06 mm.

3.2. Friction and Wear Testing

3.2.1. Friction Coefficient

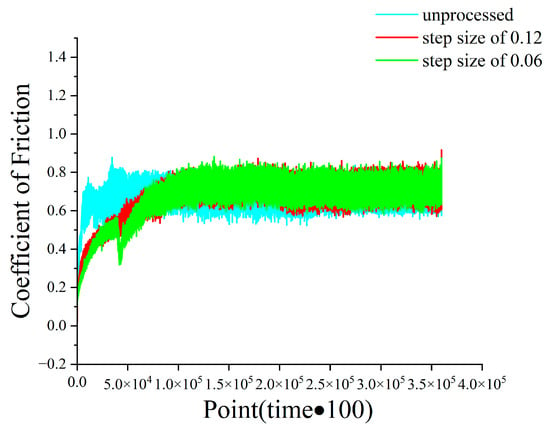

Figure 3 presents the evolution of the friction coefficient for Cr8 steel specimens subjected to USR at different step-over distances. All curves exhibit a rapid initial increase, followed by minor fluctuations before eventually reaching a stable state. Three distinct stages can be clearly identified: the initial stage, the running-in stage, and the steady-state stage.

Figure 3.

Friction coefficient of samples subjected to frictional wear under different step distances (Unprocessed, step 0.12 mm, step 0.06 mm, 30 N, 2 Hz, 60 min).

The unprocessed state is achieved after 500 s for the unprocessed sample, 1000 s for the sample treated with a 0.12 mm step-over distance, and 1200 s for the sample treated with a 0.06 mm step-over distance. The corresponding stabilized friction coefficients are 0.672, 0.663, and 0.655, respectively. Notably, the sample processed with the 0.06 mm step-over distance exhibits the smallest fluctuation amplitude during the steady state, indicating superior sliding stability.

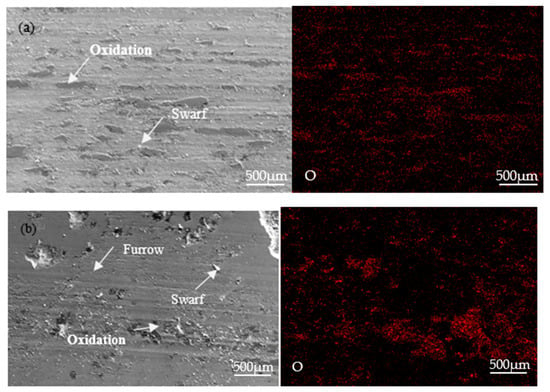

3.2.2. Microscopic Wear Scars

Figure 4 shows the worn surface morphology and corresponding oxygen distribution of Cr8 steel after wear testing. As shown in Figure 4a, the unprocessed sample tested under a 30 N load exhibits a widespread white oxide layer within the wear track, indicating severe oxidative wear. Figure 4b,c present the results for step-over distances of 0.12 mm and 0.06 mm, respectively. With decreasing step-over distance, the oxide layer becomes progressively thinner and more discontinuous. At the 0.06 mm step-over condition, oxidative wear is significantly reduced.

Figure 4.

SEM and EDS images of the wear surface morphology of specimens under a 30 N load under different step distances: (a) unprocessed, (b) step size of 0.12 mm, (c) step size of 0.06 mm.

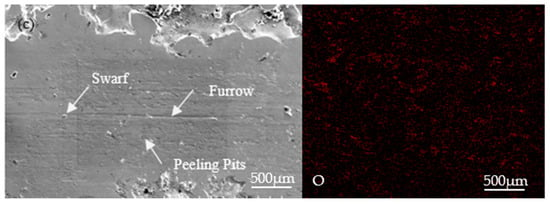

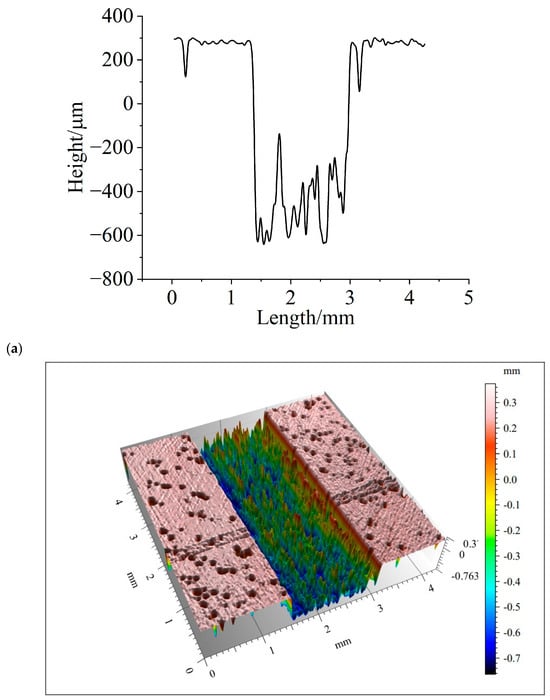

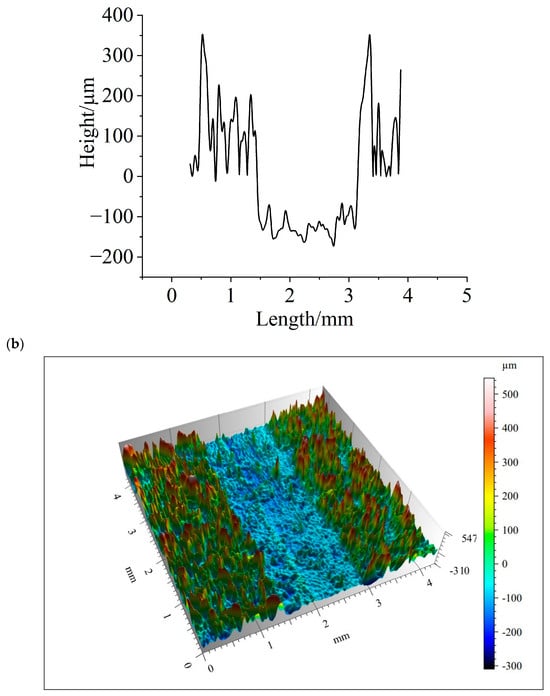

3.2.3. Three-Dimensional Topography and Wear Volume

Figure 5 displays the cross-sectional profiles and corresponding morphologies of the wear scars. The unprocessed sample exhibits a wear scar width of 600 μm, whereas the samples treated with step-over distances of 0.12 mm and 0.06 mm show widths of approximately 171 μm and 136 μm, respectively. The specimen processed with the 0.06 mm step-over distance exhibits a significantly shallower wear scar, reflecting its superior wear resistance.

Figure 5.

Three-dimensional surface topography and cross-sectional wear profiles of materials following friction and wear testing under different step distances: (a) unprocessed, (b) step size of 0.12 mm, (c) step size of 0.06 mm.

Wear volume serves as a key parameter for evaluating wear performance [21,22]. In this study, the wear volume was determined through integration of the cross-sectional profiles using Origin software (Version 2022b, OriginLab Corporation, Northampton, MA, USA), in accordance with the following formula:

where a1, a2, a3, b1, b2, b3, c1, c2, c3 represent the integrated data obtained from individual cross-sectional curves using Origin software, and d denotes the reciprocating friction length. Wear volume and wear rate were calculated using the appropriate formulas. Statistical analysis (one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s HSD post hoc test, α = 0.05) confirmed that the differences among the three conditions (Unprocessed, Step 0.12 mm, and Step 0.06 mm) were statistically significant for both wear volume and wear rate (p < 0.05 in all pairwise comparisons). Specifically, the untreated sample exhibited the highest wear volume (5.72 × 10−2 mm3), followed by the 0.12 mm step-over sample (5.483 × 10−2 mm3), while the 0.06 mm step-over sample showed the lowest wear volume (5.469 × 10−2 mm3). In terms of wear rate, the untreated sample displayed the highest value (2.407 × 10−5 mm3/(N·m)), followed by the 0.12 mm step-over sample (2.308 × 10−5 mm3/(N·m)), whereas the 0.06 mm step-over sample exhibited the lowest wear rate (2.302 × 10−5 mm3/(N·m)), indicating enhanced wear resistance. Although the absolute differences are small (on the order of 10−3 mm3), the statistical significance supports a consistent and reproducible trend of improved wear resistance with decreasing step-over distance.

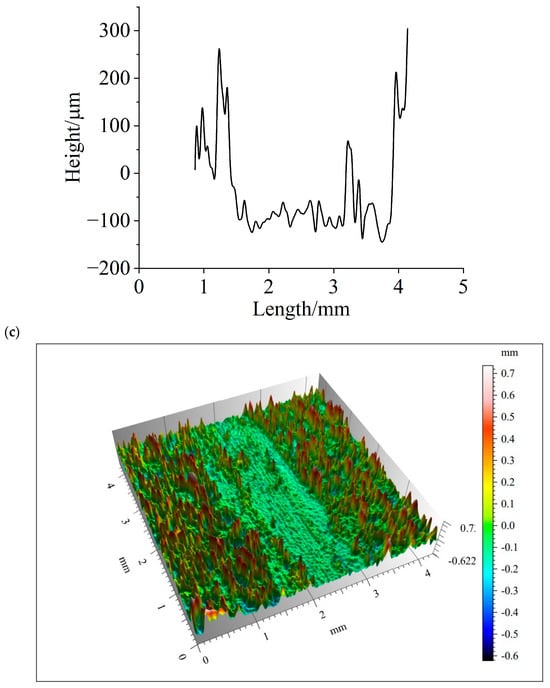

3.3. Electrochemical Analysis

3.3.1. Potentiodynamic Polarization

Figure 6 presents the potentiodynamic polarization curves obtained from electrochemical measurements. Table 5 lists polarization curve fitting parameters for the material under different step distances, the polarization resistance values for the unprocessed sample, the sample processed with a 0.12 mm step-over distance, and the sample processed with a 0.06 mm step-over distance are 301.03 Ω, 326.67 Ω, and 478.22 Ω, respectively. The corresponding corrosion current densities are 5.515 µA·cm−2, 4.083 µA·cm−2, and 3.472 µA·cm−2, indicating a progressive improvement in corrosion resistance with decreasing step-over distance. As shown in Figure 6, Polarization curves of the material under different process conditions exhibit a similar trend: the corrosion current initially decreases to a minimum before increasing with further increases in corrosion potential. By integrating the data presented in Figure 5 and Figure 6, it can be concluded that the sample processed with a step size of 0.06 exhibits the lowest corrosion rate reduction.

Figure 6.

Polarization curves of the material under different step distances.

Table 5.

Polarization curve fitting parameters of the material under different step distances.

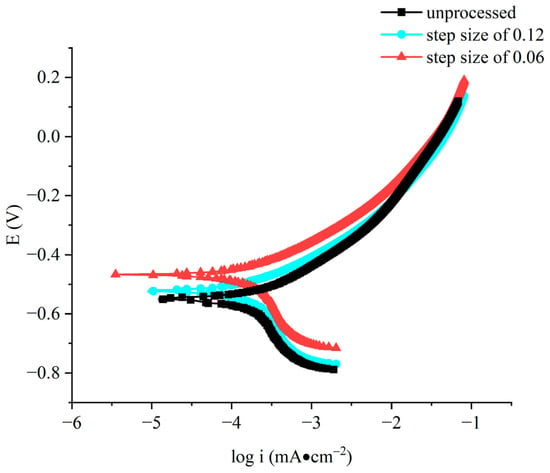

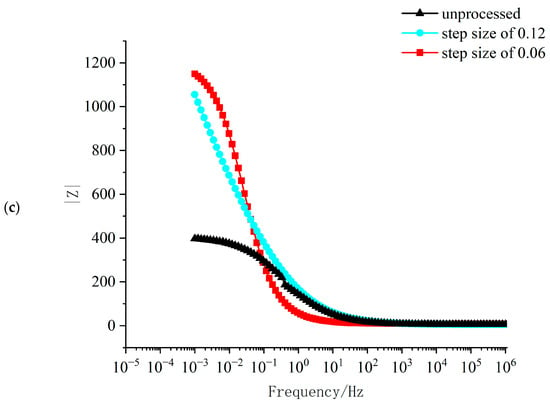

3.3.2. Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy

To gain deeper insight into the interfacial processes and the protective characteristics of the surface, electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) was performed. The Nyquist plots (Figure 7a) exhibit a single, depressed capacitive arc for all samples, with a significant increase in arc diameter following USR treatment. The largest arc diameter was observed for the sample processed with a 0.06 mm step distance, indicating the highest charge-transfer resistance. In the phase angle plot (Figure 7b), the low-frequency region (below 10 Hz)—which corresponds to the charge-transfer process at the metal/electrolyte interface—shows an increase in the maximum phase angle from 35° for the unprocessed sample to about 40° for the 0.12 mm step sample, exceeding 50° for the 0.06 mm step sample. A higher phase angle at low frequencies is typically indicative of a more capacitive and effectively protective interface. This trend is further confirmed by the impedance modulus plot (Figure 7c), where the low-frequency impedance |Z|0.001 Hz increases in the order: unprocessed < 0.12 mm step < 0.06 mm step.

Figure 7.

Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy analysis of materials prepared under different step distances: (a) Nyquist plots and corresponding equivalent circuits, (b) Bode phase angle plots, (c) Bode magnitude plots.

The experimental EIS data were fitted using the equivalent circuit model (ECM) shown in the inset of Figure 7a, in which Rs represents the solution resistance, CPE1 and CPE2 are constant phase elements accounting for the capacitance behavior of the passive film and interface, and Rp denotes the polarization resistance. The fitted parameters are summarized in Table 5. The polarization resistance Rp obtained from ECM fitting follows the same trend as that derived from potentiodynamic polarization, increasing from 587.2 Ω for the unprocessed sample to 991.2 Ω and 1207 Ω for the 0.12 mm and 0.06 mm step samples, respectively. This provides quantitative evidence of the enhanced barrier properties induced by USR, particularly with optimized step distance.

3.3.3. Corrosion Inhibition Efficiency

The corrosion inhibition efficiency can be calculated using the following formula, which is derived from the polarization resistance and corrosion rate reduction:

ηR reflects the overall barrier performance of the surface protective layer (e.g., a dense passive film) under steady-state conditions, whereas ηI represents the inhibitory capacity against corrosion reactions during dynamic degradation processes. As shown in Table 5 and Table 6, the corrosion inhibition efficiency (η), calculated based on corrosion rate reduction (Icorr) and polarization resistance (Rp), consistently demonstrates that the material’s corrosion resistance improves systematically with decreasing ultrasonic rolling step-over distance. Specifically, the sample processed with a 0.06 mm step-over distance exhibits the highest corrosion inhibition efficiency (ηI ≈ 37.05%, ηR > 50%), followed by the 0.12 mm step-over sample (ηI ≈ 25.97%, ηR ≈ 40.7%), both showing significantly enhanced corrosion protection compared to the unprocessed sample. Although the inhibition efficiency derived from Icorr is moderate in absolute value, the substantial increase in Rp clearly indicates a fundamental improvement in the surface’s protective characteristics.

Table 6.

EIS fitting parameters under different step distances in 3.5 wt.% NaCl solution.

4. Discussion

The experimental results demonstrate that USR step distance is a critical parameter governing the surface integrity and functional performance of shot-peened Cr8 steel. The 0.06 mm step consistently yielded the best tribological and corrosion properties, which can be attributed to the synergistic interplay between surface topography refinement and subsurface microstructural evolution.

4.1. Synergistic Role of Step Distance and Integration with Composite Processing

The paramount finding of this study is that the USR step distance serves as a pivotal parameter governing the homogeneity of plastic deformation, thereby determining the effectiveness of the entire shot peening–USR composite process. Unlike intrinsic material properties, step distance is an extrinsic and controllable variable that directly regulates the overlap between deformation tracks, and consequently, the uniformity of the resulting surface integrity.

Criticality of Step Distance for Deformation Uniformity: The selection of step distance directly governs track overlap and the homogeneity of plastic deformation. A 0.06 mm step ensures optimal, near-complete overlap, enabling uniform plastic deformation across the entire surface. This uniformity is essential for eliminating localized weak zones and achieving consistent topographical smoothing and microstructural refinement. In contrast, a 0.12 mm step leads to insufficient overlap, resulting in a heterogeneous surface characterized by alternating regions of high and low deformation. This non-uniform deformation restricts the full realization of performance improvements, as evidenced by the intermediate values observed in hardness, surface roughness, and corrosion resistance.

Synergy with Shot Peening Pre-treatment: The effectiveness of USR is profoundly dependent on the initial microstructural state established by shot peening. The pre-existing work-hardened layer and compressive residual stress field [5,6] create a “pre-strained” microstructure with high dislocation density. Subsequent USR, particularly with an optimized fine step (0.06 mm), further refines and homogenizes this deformed structure. It promotes the transformation of dislocation cells into sub-grains and facilitates a more uniform redistribution of residual stresses. This sequential processing—where shot peening generates a deep compressive zone and USR precisely modifies the topmost surface layer—produces a superior gradient architecture that cannot be achieved by either technique individually, a result consistent with findings reported for other alloy systems [23]. Consequently, the step distance emerges as a critical factor in maximizing the synergistic benefits of this hybrid process on a uniquely pre-conditioned surface.

4.2. Mechanisms of Tribological Enhancement

Building upon the uniform surface architecture achieved with a 0.06 mm step distance, the tribological improvements are realized through a dual mechanism involving synergistic surface topography refinement and subsurface microstructural strengthening.

Surface Topography Effects: Reducing the step distance from 0.12 mm to 0.06 mm significantly decreased surface roughness. The resulting smoother surface reduces mechanical interlocking between asperities during sliding contact, thereby contributing to a lower and more stable coefficient of friction [24]. Additionally, the reduced surface roughness enhances the retention of wear debris, which can act as a solid lubricant, and promotes the formation of a more stable tribo-oxidative layer. As a result, the dominant wear mechanism shifts from severe oxidative-abrasive wear—observed in the unprocessed sample—to mild abrasive wear. This is in excellent agreement with the tribological principle established by Leban M B et al. [25], which directly correlates surface finish with friction and wear behavior.

Subsurface Microstructural Strengthening: In addition to surface smoothing, USR induces severe plastic deformation in the near-surface region. The combination of high-frequency impacts and static pressure promotes grain refinement, dislocation multiplication, and work hardening, as evidenced by the increased surface microhardness (Table 3). This hardened subsurface layer enhances resistance to plastic deformation and abrasive penetration during sliding wear. In addition to grain refinement and work hardening, the exceptionally high compressive residual stress plays a pivotal role in enhancing surface durability. This residual stress field functions as a pre-stressed protective layer, effectively imposing a substantial compressive bias within the near-surface region. During sliding contact, it significantly counteracts the tensile components of the applied contact stresses, thereby suppressing both the initiation and propagation of subsurface micro-cracks and delaying the onset of fatigue-driven delamination wear.

4.3. Mechanisms Underlying Corrosion Performance

The Cr8 die steel employed in this study did not exhibit a typical passivation plateau in its anodic polarization curve (Figure 6), as commonly observed in austenitic or ferritic stainless steels. This behavior is primarily attributed to the intrinsic characteristics of its material system. As a high-carbon, high-chromium tool steel, Cr8 is specifically designed to achieve exceptional wear resistance through the formation of a large volume fraction of hard carbides, rather than to provide superior corrosion resistance. Following heat treatment, the majority of chromium is incorporated into carbide phases—such as Cr7C3 and Cr23C6—thereby significantly depleting the matrix of dissolved chromium. Consequently, the effective chromium concentration in the solid-solution matrix falls below the threshold required to form a continuous and stable Cr2O3 passive film [26].

The electrochemical results demonstrate that ultrasonic surface rolling USR, particularly with a 0.06 mm step distance, significantly enhances the corrosion resistance of shot-peened Cr8 steel in a 3.5 wt.% NaCl solution. This improvement is mechanistically attributed to the enhancement of physical barrier effect and interfacial mechanical stability and a kinetics-dominated inhibition process.

Enhanced Physical Barrier Effect: USR-treated samples exhibit a marked increase in polarization resistance and an expanded capacitive arc diameter in the Nyquist plots, indicating the formation of a more protective surface interface. Furthermore, the elevated phase angle in the low-frequency region of the Bode plot—exceeding 50° for the 0.06 mm sample—reflects a more capacitive, less defective interface, a high-impedance charge-transfer process [27]. These improvements are primarily driven by three key microstructural modifications induced by fine-step USR: (i) a substantial reduction in surface roughness, which minimizes the effective surface area exposed to the electrolyte and reduces potential active sites for pitting initiation and aggressive ion adsorption [28]; and (ii) refinement of the near-surface grain structure. As reported by Lin et al. [29], grain refinement increases grain boundary density, which promotes the rapid formation of a more uniform, dense, and strongly adherent passive film, thereby enhancing resistance to chloride ion penetration. (iii) Smaller-step ultrasonic rolling introduces high levels of residual compressive stress, which significantly enhances corrosion resistance. This compressive stress densifies the surface lattice, thereby reducing the density of micro-defects that can act as initiation sites for pitting corrosion. Consequently, the improved corrosion resistance arises from the synergistic interaction between an enhanced surface physical barrier (attributed to reduced roughness and refined grains) and increased interfacial mechanical stability (induced by high residual compressive stress).

Kinetic Mechanism of Electrochemical Behavior: A notable observation is the positive shift in corrosion potential (Ecorr) concurrent with a significant decrease in corrosion rate reduction (Icorr). This apparent decoupling between thermodynamic tendency and actual corrosion rate is well explained by mixed-potential theory [30]. The surface modifications induced by USR—particularly surface smoothing and grain refinement—likely impose a stronger inhibitory effect on cathodic reactions (e.g., oxygen reduction) by severely impeding mass transport (e.g., oxygen diffusion) to the electrode surface. In contrast, the suppression of the anodic reaction (metal dissolution) is comparatively weaker. This asymmetric kinetic inhibition leads to a positive shift in the mixed potential (Ecorr) while simultaneously reducing the overall corrosion current (Icorr). Thus, the enhancement in corrosion resistance is fundamentally governed by kinetic factors, underscoring the superior practical relevance of Icorr and Rp over Ecorr as performance indicators.

The corrosion inhibition mechanism elucidated above—whereby refined surface topography and microstructure lead to increased polarization resistance and reduced corrosion current—finds a compelling parallel in surface engineering strategies for other metal systems. A representative study on anodized aluminum for solar absorbers demonstrated that the formation of a dense, adherent oxide layer (e.g., blackened anodized Al) significantly enhances corrosion resistance in 3.5 wt.% NaCl solution, primarily through the establishment of a robust physical barrier [31]. Although the specific techniques differ fundamentally—mechanical severe plastic deformation for steel versus electrochemical conversion coating for aluminum—the underlying principle remains consistent: deliberate modification of the surface state to suppress electrochemical reactions constitutes a universal strategy for corrosion mitigation. Our work extends this paradigm by establishing a quantitative and causal relationship between a specific mechanical processing parameter (USR step distance) and key electrochemical performance metrics (e.g., a 37.05% inhibition efficiency achieved at a 0.06 mm step).

4.4. Limitations and Research Gaps

While this study quantitatively demonstrates the advantages of reducing the USR step distance, several limitations must be acknowledged to clearly delineate the scope of our conclusions. First, the experiments were conducted using fixed values for other USR parameters (static force, amplitude, frequency) and a single rolling pass. The potential interactions between step distance and these parameters, as well as the influence of multiple passes, remain unexplored and could lead to more complex optimization pathways. Second, corrosion evaluation was limited to static immersion in a neutral chloride solution; performance under dynamic flow conditions, cyclic mechanical loading, or in acidic and industrially relevant environments—common in practical die applications—may differ significantly. Finally, the time and economic costs associated with implementing a 0.06 mm step distance in large-scale industrial production require further techno-economic assessment to evaluate its practical feasibility relative to the achieved performance improvements.

5. Conclusions

This study systematically investigates the influence of USRstep distance on the surface integrity and functional performance of shot-peened Cr8 steel. The main conclusions are as follows:

- The USR step distance is a critical process parameter governing surface modification effectiveness. A step distance of 0.06 mm yields the smoothest surface topography and the highest surface hardness, significantly outperforming both the 0.12 mm step condition and the untreated state.

- The optimized step distance (0.06 mm) promotes uniform plastic deformation, transforming the dominant wear mechanism from severe oxidative-abrasive wear to mild abrasive wear. This transition results in the lowest friction coefficient, wear volume, and wear rate, thereby demonstrating superior wear resistance.

- These same processing parameters synergistically enhance corrosion resistance through reduced surface roughness and refined near-surface grain structure, as evidenced by the highest polarization resistance and the lowest corrosion rate reduction.

In summary, applying USR with a 0.06 mm step distance after shot peening represents an optimized and efficient strategy to simultaneously enhance wear resistance and achieve corrosion inhibition in Cr8 steel. This study provides a clear, data-driven methodology for selecting the optimal USR step distance in composite surface strengthening processes. Future research should focus on extending this approach by exploring multi-pass USR treatments and integrating USR with other surface engineering techniques to further improve performance limits for critical industrial components.

Author Contributions

C.L.: Conceptualization; methodology; software; formal analysis; investigation; data curation; writing—original draft preparation; visualization. H.Y.: software; validation; investigation; data curation; visualization. Y.Y.: software; validation; investigation; data curation; writing—review and editing. H.H.: validation; resources; writing—review and editing; funding acquisition. L.L.: Conceptualization; resources; supervision. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by 2023 Three-Year Action Plan for Capacity Building of Local Universities in Shanghai, grant number 23010500800.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Yujing Yin was employed by the company Shougang Qian’an Iron & Steel Co., Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Chen, X.; Liu, B.; Zhang, B.; Sun, J.; Yang, Z.; Zhou, X.; Huang, T.; Yin, D. Modeling of Dynamic Recrystallization Evolution for Cr8 Alloy Steel and Its Application in FEM. Materials 2022, 15, 6830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.; Kang, J.Y.; Son, D.; Lee, T.H.; Cho, K.M. Evolution of carbides in cold-work tool steels. Mater. Charact. 2015, 107, 376–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Antonov, M.; Berglund, T.; Pampori, T.H.; Maurya, H.S.; Viljus, M. Wear mechanisms of PM-HIP tool steels under low and high-stress abrasion: Role of carbide type and content. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2025, 36, 7016–7025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.; Nyo, T.; Kaijalainen, A.; Hannula, J.; Porter, D.; Kömi, J. Influence of Chromium Content on the Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of Thermomechanically Hot-Rolled Low-Carbon Bainitic Steels Containing Niobium. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovacı, H.; Bozkurt, Y.; Yetim, A.; Aslan, M.; Çelik, A. The effect of surface plastic deformation produced by shot peening on corrosion behavior of a low-alloy steel. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2019, 360, 78–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wu, L.; He, X.; Wang, Z.; Qu, S.; Qin, H. Effect of Shot Peening on Friction and Wear Behaviors of Cr-Ni-Mo High Strength Steel. Tribology 2023, 43, 1072–1082. [Google Scholar]

- Wagner, L.; Mhaede, M.; Wollmann, M.; Altenberger, I.; Sano, Y. Surface layer properties and fatigue behavior in Al 7075-T73 and Ti-6Al-4V. Int. J. Struct. Integr. 2011, 2, 185–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, S.; Wang, A.; Zhang, W.; Li, F.; Yu, Q.; Jin, P.; Zhang, K.; Jiang, Z. Effect of Shot Peening Coverage on the Surface Integrity of a 7b50-T7751 Aluminum Alloy. SSRN 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, G.; Chen, J.; Xue, H.; Duan, S.; Wang, A.; Zhang, W. Surface Morphology Evolution Together with Its Effect on Fatigue Properties in Shot Peening of Aluminum Alloy 7B50-T7751. China Surf. Eng. 2022, 35, 187–195. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, R.; Xu, S.; Xu, C.; Sun, K.; Ju, X.; Yang, X.; Pan, Y.; Li, J.; Ren, G.; Wang, L. Study on the effect of ultrasonic rolling on the microstructure and fatigue properties of A03600 aluminum alloy. J. Alloys Compd. 2025, 1010, 178124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Xu, S.; Xue, X.; Zhao, X.; Pan, Y.; Li, J.; Zheng, W. Effect of Multi-pass Ultrasonic Surface Rolling Process on Surface Properties and Microstructure of GCr15 Steel. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2024, 34, 17354–17366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Zhao, Y. Influence of Ultrasonic Surface Rolling Processing on Tribological Performance of 45 Steel and Its Mechanism. Mater. Mech. Eng. 2017, 41, 44–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, H.; Sun, X.; Liu, Y.; Rao, X.X.; Gu, Q. Effect of ultrasonic surface rolling process on mechanical properties and corrosion resistance of AZ31B Mg alloy. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2019, 372, 288–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Chen, D.; Su, B.; Chen, D.; Ren, Z.; Zou, D.; Liu, K. Effects of ultrasonic surface rolling processing on the corrosion properties of uranium metal. J. Nucl. Mater. 2021, 556, 153239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Liu, D.; Ren, Z.; Zhi, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, R.; Liu, D.; Xu, X.; Fan, K.; Liu, C.; et al. Grain growth and fatigue behaviors of GH4169 superalloy subjected to excessive ultrasonic surface rolling process. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2022, 839, 142875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Qu, S.; Lu, F.; Lai, F.; Ji, V.; Liu, H.; Li, X. Microstructures and rolling contact fatigue behaviors of 17Cr2Ni2MoVNb steel under combined ultrasonic surface rolling and shot peening. Int. J. Fatigue 2020, 141, 105867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, C.; Qu, S.; Hu, X.; Jia, S.; Li, X. Evaluation of the influencing factors of combined surface modification on the rolling contact fatigue performance and crack growth of AISI 52100 steel. Wear 2022, 494–495, 204252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Zhang, Q.; Sun, M.; Wei, X.; Zhu, Y. Microstructure and corrosion resistance of laser clad coatings with rare earth elements. Corros. Sci. 2001, 43, 255–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, N.; Yu, L.; Xu, S.; Tian, Q.; Ding, C.; Su, L.; Wang, H. Study on the Morphology, Wear Resistance, and Corrosion Resistance of CuSn12 Alloys Subjected to Machine Hammer Peening. Metals 2025, 15, 444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Zha, Y.; Zhang, T.; Shi, H.; Zhang, X.; Cao, C.; Huang, D.; Sun, J.; Zhang, B.; Zhao, J. Construction of a Gradient Nanostructure for Enhanced Surface Properties in 38CrMoAl Steel via Ultrasonic Severe Surface Rolling. Materials 2025, 18, 5308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, C.R.Á., Jr.; Pintaude, G. Uncertainty analysis on the wear coefficient of Archard model. Tribol. Int. 2008, 41, 473–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; S, R.; Wang, Y.; Cheng, Y.; Gao, L. Effect of ultrasonic surface rolling process on corrosion resistance of 304 stainless steel. Heat Treat. Met. 2024, 49, 268–274. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Xia, Y.; Wu, L.; Shi, D.; Liu, L.; Qu, S.; He, X. Friction and Wear Properties of Cr-Ni-Mo High Strength Steel Treated by Shot Peening Combined with Ultrasonic Rolling. Surf. Technol. 2025, 54, 173–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, B.; Song, R.; Li, H.; Li, X.; Chen, Z. EIS analysis of stress corrosion cracks propagation in 7003 aluminum alloy. Chin. J. Nonferrous Met. 2016, 26, 1832–1842. [Google Scholar]

- Leban, M.B.; Mikyška, Č.; Kosec, T.; Markoli, B.; Kovač, J. The Effect of Surface Roughness on the Corrosion Properties of Type AISI 304 Stainless Steel in Diluted NaCl and Urban Rain Solution. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2014, 23, 1695–1702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amini, K.; Akhbarizadeh, A.; Javadpour, S. Effect of Carbide Distribution on Corrosion Behavior of the Deep Cryogenically Treated 1.2080 Steel. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2016, 25, 365–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, R.; Wang, B.; Yan, Z.; Wang, Z.; Dong, L. Effect of Surface Topography Parameters on Friction and Wear of Random Rough Surface. Materials 2019, 12, 2762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Xu, J.; Yu, S.; Xu, G.; Tang, C. Unraveling microstructure evolution induced mechanical and corrosion resistance responses in extruded titanium alloy subjected to varied Cu regulation. J. Alloys Compd. 2024, 1009, 176981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.; Duh, J. Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) study on corrosion performance of CrAlSiN coated steels in 3.5wt.% NaCl solution. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2009, 204, 784–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walczak, M.; Szala, M.; Okuniewski, W. Assessment of Corrosion Resistance and Hardness of Shot Peened X5CrNi18-10 Steel. Materials 2022, 15, 9000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlShamaileh, E.; Altwaiq, A.M.; Esaifan, M.; Al-Fayyad, H.; Shraideh, Z.; Moosa, I.S.; Hamadneh, I. Study of the Microstructure, Corrosion and Optical Properties of Anodized Aluminum for Solar Heating Applications. Metals 2022, 12, 1635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.