Abstract

The breakup process of molten metal is the most critical stage in atomization powder production. Conducting systematic research on the breakup process of molten metal during gas atomization is highly significant for understanding the formation mechanism of droplets. In this study, a mathematical model suitable for investigating the breakup mechanism of molten aluminum in high-speed gas atomization was developed by coupling large eddy simulation (LES) with the volume of fluid (VOF) model, incorporating adaptive mesh refinement technology and periodic boundary conditions. Furthermore, the breakup behavior of molten aluminum in two close-coupled atomizers with distinct delivery tube end geometric (non-expanded type and expanded type, abbreviated as ET atomizer and NET atomizer) were compared. The development of surface waves, as well as the formation mechanisms of liquid cores, liquid ligaments, and liquid droplets during gas atomization, were systematically analyzed. The results indicated that Kelvin–Helmholtz instability was the predominant factor contributing to the primary breakup of molten metals. For the NET atomizer, the recirculation zone predominantly governed the primary breakup of molten metal, whereas the nitrogen main jet primarily controlled the secondary breakup. In the case of ET atomizer, under the influence of atomizing gas, a “conical” liquid core gradually formed, and numerous primary liquid droplets separated from the liquid core before undergoing secondary breakup. Compared to the ET atomizer, the NET atomizer produced droplets with a smaller average size.

1. Introduction

Metal powder, serving as a critical foundational material in modern industry, has been extensively utilized in core domains such as mechanical manufacturing, medical implants, aerospace, and additive manufacturing [1,2]. In light of the sustained growth in market demand, gas atomization technology has emerged as the predominant method for industrial-scale production of metal powders, attributed to its advantages including low cost, high production efficiency, and superior powder sphericity [3,4]. With the steady rise in annual metal powder consumption, enhancing atomization efficiency and fine powder yield has become a focal point of research attention. As the central component of gas atomization technology, the structural parameters of the atomizer significantly influence particle size distribution, powder sphericity, atomization efficiency, and energy consumption. For the close-coupled atomizer system, the geometric configuration of the nozzle and delivery tube constitutes the primary design variables. Among these, the delivery tube’s structure plays a pivotal role in improving atomization performance by affecting melt flow stability, atomized particle size distribution, and gas flow field dynamics [5,6]. This strong correlation between structural design and performance outcomes underscores the importance of optimizing the delivery tube structure as a key approach to overcoming existing atomization technology bottlenecks. Thus, investigating the influence mechanism of the delivery tube structure on the gas atomization process holds substantial significance.

Many scholars have conducted in-depth research on the influence of the delivery tube structure on the gas atomization process [7,8,9]. Huang et al. [10] investigated the influence of delivery tube position on the tip pressure of the delivery tube by adjusting the relative distance between the delivery tube and the nozzle outlet surface. Motama et al. [11] examined the impact of the geometry of the delivery tube tip on gas flow behavior within a close-coupled atomizer. Zhang et al. [12] analyzed the effect of tip modifications (sawtooth shape vs. unmodified) of the delivery tube in a close-coupled atomizer on the gas flow field during atomization. The results demonstrated that the sawtooth modification induced flow vortices, which subsequently led to localized variations in the density, velocity, and temperature of the atomizing gas near the tip of the delivery tube. These studies indirectly analyzed the potential impact of the delivery tube structure on the atomization process and powder particle size by investigating the influence of the structural parameters of the delivery tube on the flow field characteristics of the atomizing gas. However, studying only the single-phase flow behavior during the gas atomization process was insufficient to clearly elucidate the effect of the delivery tube’s structural parameters on the droplet size distribution in the gas atomization process, or to reveal the breakup mechanism of molten metal. The breakup process of molten metal is the most critical stage in atomization powder production. Investigating the breakup mechanism of molten metal during gas atomization is essential for effectively controlling droplet formation. Wang et al. [13,14] conducted numerical simulations to examine the effects of the extension length and diameter of the delivery tube on nozzle clogging. They employed the volume of fluid (VOF) and large eddy simulation model to visualize the primary breakup process of molten metal. However, their study was limited to a two-dimensional numerical analysis focusing solely on the primary breakup process of gas atomization. Zeoli et al. [15,16] performed multiple three-dimensional gas–liquid two-phase simulations to elucidate the primary breakup mechanism of the molten metal. It is evident that these studies predominantly concentrated on the early phase of the atomization process, focusing merely on the analysis of phenomena such as the initial deformation of the liquid column and the detachment of large droplets from the continuous phase. However, few scholars have conducted a systematic investigation into the detailed atomization mechanisms in the gas atomization process, including surface waves, liquid cores, liquid films, liquid ligaments, and droplets. This will constitute the focal point of this paper.

This study investigated the breakup mechanism of molten aluminum by coupling the large eddy simulation (LES) and volume of fluid (VOF) model. To achieve a more accurate representation of the breakup details during the gas atomization process while minimizing computational resources, adaptive mesh refinement (AMR) technology and periodic boundary conditions were implemented for the computational domain. A mathematical model tailored for analyzing the breakup mechanism of molten metal in the gas atomization process was developed in this work. The breakup behavior of molten aluminum in two close-coupled atomizers with distinct delivery tube end geometry configurations (non-expanded type and expanded type) was comprehensively examined. Additionally, the formation mechanisms of surface waves, liquid cores, liquid films, liquid ligaments, and liquid droplets during the gas atomization process were thoroughly analyzed.

2. Model Descriptions

2.1. Basic Assumptions

In this paper, the commercial CFD software Fluent 2020 R2 was utilized to simulate the gas atomization process of molten aluminum. To enable real-time observation of gas–liquid interaction, a combination of the LES model and VOF model was employed for calculating the two-phase flow of nitrogen and molten aluminum during gas atomization. To simplify the physics and conserve computational resources, several assumptions were made:

- (1)

- Nitrogen was treated as an incompressible fluid;

- (2)

- Molten aluminum and nitrogen were considered immiscible;

- (3)

- The heat transfer and solidification in the atomization process were disregarded.

2.2. Governing Equations

2.2.1. Turbulence Model

Presently, for the investigation of the two-phase flow during the atomization process, nitrogen was commonly regarded as an incompressible fluid. Consequently, the continuity equation and momentum conservation equation for fluid flow were described by Equations (1) and (2):

where u was the fluid velocity vector, m/s; was the fluid pressure, Pa; was the fluid density, kg/m3; was the acceleration of gravity, m/s2; μ was the fluid viscosity, Pa·s; was the surface tension, N.

The continuous surface force (CSF) model was utilized to solve for the surface curvature and surface tension at the phase interface. This model incorporated surface tension as a volume force in the fluid momentum equation, as described by Equation (3) [17]:

where was the surface tension coefficient, N/m; was the curvature, m−1; and was the surface normal.

2.2.2. LES and Sub-Grid Stress Model

The gas–liquid two-phase flow in the atomization process involved interaction between the phases, and the turbulent pulsation of the gas phase had a significant impact on that of the liquid phase [18]. Therefore, accurately predicting the turbulent motion of the atomization flow field was crucial. The LES method provided a more precise capture of turbulent pulsation information. To better comprehend the turbulent structure during atomization, this paper employed LES to calculate fluid turbulence throughout the process.

The fundamental concept of large eddy simulation was as follows [19,20]: turbulence in fluid motion was considered to be comprised of vortices with varying scales. Mass, momentum, energy, and other passive scalars in turbulent motion were primarily transported by the larger-scale vortices, while the smaller-scale vortices exhibited less dependence on geometry and tended to be isotropic. Consequently, the turbulent flow was decomposed into large-scale and small-scale vortices through a filtering method. The large-scale vortices were directly solved based on the N-S equation, whereas the small-scale vortices were addressed using a subgrid-scale model.

The gas–liquid phases involved in the current atomization process were considered incompressible and immiscible fluids. The LES governing equations were derived through a filtering process to the incompressible N-S equations:

where the variables denoted by “~” in Equations (4) and (5) represented the large-scale flow field variables generated by the spatial filtering, namely, , , , , which correspond to the filtered velocity, filtered pressure, filtered gravity, and filtered surface tension, respectively; was the sub-grid scale stresses.

The sub-grid scale stress resulting from the filtering operation was unknown. To close the equation, it was necessary to model the sub-grid stress term, and thus a sub-grid stress model was introduced to simulate this term. Based on the Boussinesq hypothesis [21], the sub-grid stress can be calculated using Equation (6).

where was the isotropic part of the sub-grid scale stresses that did not need to be modeled but were added to the filtered static pressure term; was the Kronecker symbol; and was the sub-grid scale turbulent viscosity, which was solved by the Smagorinsky–Lilly model, defined as [22]:

where CS was the Smagorinsky constant, which took the value of 0.1; was the local grid-scale calculated from the volume of the calculation cell that was expressed as ; and was the rate-of-strain tensor for the solved scale, which was defined by Equation (8):

where and were the filtered velocities of the fluid in direction i and j, respectively.

2.2.3. Multiphase Flow

In this paper, the VOF method [23] was used to achieve the transient tracking of the phase interface and the phase distribution of the nitrogen/molten aluminum in the two phases during the atomization process. The VOF model simulated the two phases of the nitrogen/aluminum and the phase interface by solving a single set of momentum equations and describing the fluid phase by tracking the volume function γ for each fluid in the grid cells in the computational domain.

The tracking of the two-phase interface was achieved by solving the fluid volume function. The fluid volume function transport equation was shown in Equation (9):

The grid cells at the phase interface existed in both gas and liquid phases with γ values between 0 and 1. For nitrogen, which was considered as the primary phase, the volume fraction was calculated based on the following constraint:

where and were the volume fraction of nitrogen and molten aluminum, respectively; n was the number of phases, which was two in this paper (phase 1 was nitrogen while phase 2 was molten aluminum). The density and the viscosity of the fluid in each cell were calculated from the weighted values of the volume fraction γ of each phase as shown in Equations (11) and (12):

2.3. Model Building and Parameters

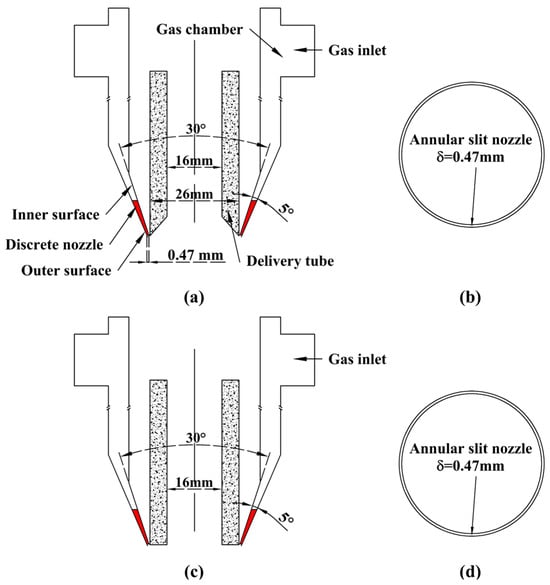

In this study, two annular slit atomizers with different end geometries of delivery tubes were modeled to investigate the breakup mechanism of molten aluminum during gas atomization. The schematic diagram of the atomizers structure was presented in Figure 1. For ease of subsequent analysis, the atomizers with the delivery tube characterized bt the expanded end and non-expanded end were referred to as the ET atomizer and the NET atomizer, respectively.

Figure 1.

Structure diagram of atomizers: (a,b) ET atomizer; (c,d) NET atomizer.

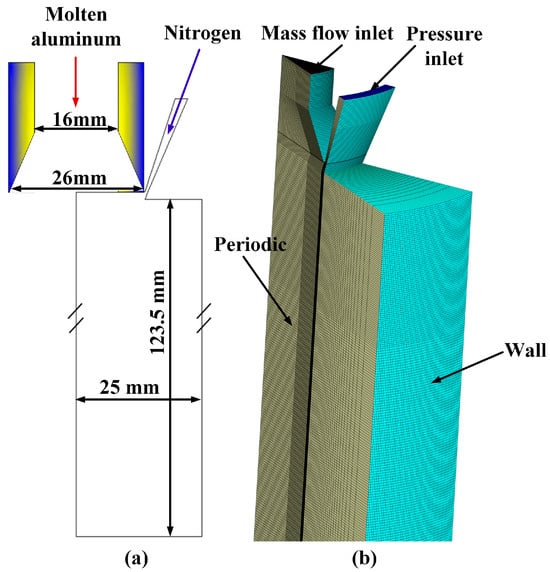

The simulation of the gas atomization process of molten aluminum necessitated the utilization of extremely fine meshes to accurately capture the droplets generated during atomization. Constructing a complete three-dimensional computational domain would require tens or even hundreds of millions of grids. Considering the constraints imposed by computing resources and the cylindrical geometry of the atomizers, this paper established a 30° three-dimensional periodic mesh (as depicted in Figure 2b). Periodic boundary conditions effectively suppress the accumulation of unphysical disturbances (e.g., spurious diffusion induced by random turbulence fluctuations), enhancing computational stability and significantly conserving computational resources. Furthermore, local mesh refinement techniques were employed near both the atomizer nozzle and its exit. To optimize computing resources, an axial length and radial length for the atomizing chamber within the calculation domain were selected at approximately 120 mm and 25 mm respectively (as shown in Figure 2a), which adequately accommodated simultaneous calculations for both primary and secondary atomization processes of molten aluminum. A computational domain comprising approximately 1.7 million structural meshes was created, with mesh sizes ranging from 50 to 600 μm.

Figure 2.

Schematic diagram of calculational domain size (a) and mesh division (b).

Due to the multi-scale characteristics of atomization phenomenon, in order to allocate more computational resources for simulating the gas atomization process and accurately capturing the interaction of the gas–liquid interface and breakup details of molten aluminum within the computational domain, the adaptive mesh refinement (AMR) method was employed to refine the mesh at the gas–liquid interface to track the two-phase interface accurately. Considering the computational cost, secondary grade refinement approach was utilized where each 3D mesh meeting the refinement criteria can be split into eight meshes. Upon completion of the calculations, the number of meshes for the computational domain increased from the initial 1.7 million to approximately 3.25 million. Considering the periodic boundary condition, this model corresponded to a complete computational domain model consisting of 39 million meshes; such grid resolution adequately captured molten aluminum droplets during gas atomization.

2.4. Initial and Boundary Conditions

The physical properties of molten aluminum and nitrogen were presented in Table 1. Considering nitrogen as an incompressible fluid for the purpose of this study, its density and viscosity were assumed to be constant.

Table 1.

Physical properties of molten aluminum and nitrogen.

The nitrogen inlet in the computational domain adopted the pressure inlet boundary condition, with an atomizing gas pressure of 3 MPa. The molten aluminum inlet in the computational domain was subjected to the mass flow inlet boundary condition, with a molten aluminum flow rate of 0.014 kg/s. At the outlet of the computational domain, the pressure outlet boundary condition was applied, ensuring the normal gradient for all variables of zero. Non-slipping wall was present on both the atomizer and atomizing chamber walls. Additionally, the periodic boundary condition was implemented on the periodic surface of the computational domain, which exhibited complete computational domain representation through rotational symmetry.

The governing equations were solved using a pressure-based solver. The N-S equation was solved employing the SIMPLE algorithm. The gradient, pressure, momentum, and volume fraction were discretized using the Least Squares Cell-Based method, PRESTO method, Bounded Central Differencing method, and Geo-Reconstruction method, respectively. The relaxation factors for pressure, density, volume force, and momentum were set to 0.3, 1, 0.5, and 0.3, respectively. The convergence criterion was based on the residuals of all aforementioned variables with a threshold value less than 0.001. To ensure stability in the solution process, the Courant number was maintained below 1 by setting a time step of 10 ns. Considering grid size and available computing resources constraints, all simulations were completed within a physical time of 0.35 ms.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Global Atomization Process Evolution

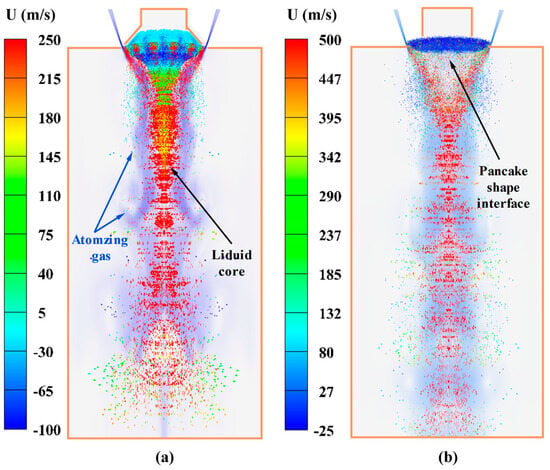

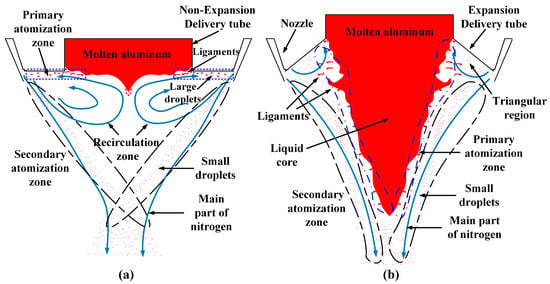

Figure 3 illustrated the global atomization processes of the ET atomizer and the NET atomizer. In the figure, the gas–liquid interface was represented by an isosurface with a volume fraction of molten aluminum of 0.1, where the color of the interface indicated axial velocity and the light blue mist area represented atomizing gas. It can be observed that for the ET atomizer, the nitrogen jet emitted from the nozzle rapidly interacted with the molten aluminum, resulting in the gradual formation of a “conical” liquid core structure, while nitrogen was distributed around this central liquid core. As the gas moved downstream, the liquid core continued to develop and generated numerous short liquid ligament structures on its surface due to the influence of the gas vortex, which was subsequently broken into droplets. In close proximity to the liquid core, and downstream within the computational domain, collisions and coalescence occurred between liquid ligaments and droplets, leading to the formation of new liquid ligaments and droplets, thereby complicating atomization. The NET atomizer exhibited the formation of a gas–liquid interface with a distinctive “pancake-shape” near the exit of the delivery tube, accompanied by a nitrogen recirculation zone below this interface. Under the influence of the recirculation zone, this “pancake-shape” interface underwent stretching and curling, initiating radial development. During this stage, intricate liquid ligament structures and large droplets were generated at various locations along the leading edge of the “pancake-shape” interface due to its interaction with nitrogen. These liquid structures were subsequently transported towards the nozzle area in a radial direction by the recirculation zone, where they underwent further breakup by the main nitrogen jet and were carried downstream within the computational domain. During this process, droplets may collide and coalesce, leading to the formation of new droplets. Comparing the gas atomization process of the two atomizers, in the case of the ET atomizer, the gas–liquid interface was distributed between the main nitrogen stream, with droplets present near the liquid core and downstream computational domain. On the other hand, for the NET atomizer, most of the gas–liquid interface existed at the exit of the delivery tube, while droplets were located within the calculation domain traversed by the main nitrogen jet. It can be observed that delivery tube’s end geometry exerted a significant influence on the gas atomization process.

Figure 3.

Global gas atomization process of ET atomizers (a) and NET atomizers (b).

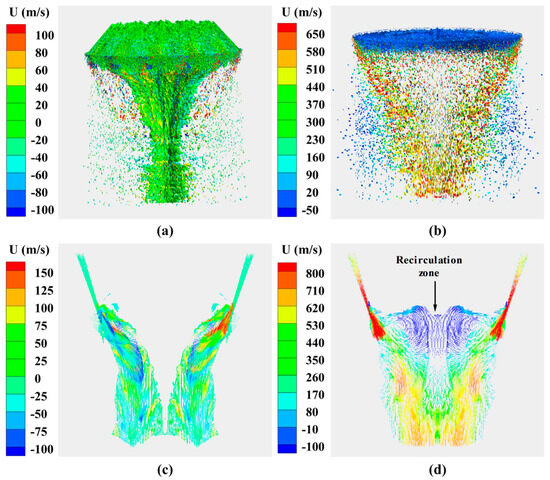

In order to enhance the clarity of observing the molten aluminum breakup process corresponding to the two atomizers, the upstream region of the calculation domain was selected for analysis. Figure 4 illustrated the gas–liquid interface and velocity vector in relation to both atomizers at the upper reaches of the calculation domain. Among them, Figure 4a,b depicted the gas–liquid interface corresponding to the ET atomizer and tje NET atomizer, respectively, while Figure 4c,d displayed the velocity vector corresponding to the ET atomizer and the NET atomizer, respectively. From Figure 4a,b, it can be observed that the gas–liquid interface of the ET atomizer takes on a “conical” shape with a large area, facilitating extensive interaction between the gas and the interface. Numerous short liquid ligament structures were present on this interface, along with a high concentration of droplets distributed around it; moreover, droplet size was smaller at distant positions from this conical interface. In contrast, the NET atomizer exhibited a “pancake-shaped” gas–liquid interface located at its delivery tube exit, where atomized droplets existed below this “pancake-shaped” gas–liquid interface. Compared with the ET atomizer, the atomization process of the NET atomizer possessed a significantly smaller gas–liquid interface area resulting in fewer primary droplets produced within the same time frame. The flow field distribution of the fluid in the atomization process was depicted in Figure 4c,d. In the case of the ET atomizer, the gas flow was predominantly distributed on both sides of the conical interface, with minimal presence within the conical interface. This observation suggested that upon exiting the nozzle, the gas directly impacted the molten aluminum, thereby establishing the main nitrogen jet as the dominant factor in both primary and secondary atomization of molten aluminum. The gas flow field of the NET atomizer was distributed downstream of the delivery tube exit within the calculation domain. Within this region, a recirculation zone existed between the “pancake” gas–liquid interface and the collision point of the main nitrogen jet. The recirculation zone exerted pressure on the molten aluminum at the delivery tube outlet, resulting in the formation of a stretched “pancake” gas–liquid interface along its radial direction. This process separated liquid structures such as liquid ligaments and large droplets from the interface, representing an initial stage in atomization for the NET atomizer. The primary droplets underwent secondary atomization as the main nitrogen jet from the nozzle, when transferring the liquid ligaments and large droplets to the nozzle exit. By comparing the atomizing gas velocities of the two atomizers, it was evident that the ET atomizer exhibited a significantly lower gas velocity. This phenomenon can be attributed to the larger “conical” gas-liquid interface, which absorbed more kinetic energy. Conversely, the gas–liquid interface below the exit of the delivery tube for the NET atomizer absorbed less kinetic energy. As a result, the nitrogen jet for the NET atomizer was able to maintain a higher velocity, enabling it to more thoroughly perform secondary breakup of the primary droplets.

Figure 4.

Gas–liquid interface and velocity vector of the two atomizers in upper reaches of calculation domain: (a) gas–liquid interface of ET atomizer; (b) gas–liquid interface of NET atomizer; (c) velocity vector of ET atomizer; (d) velocity vector of NET atomizer.

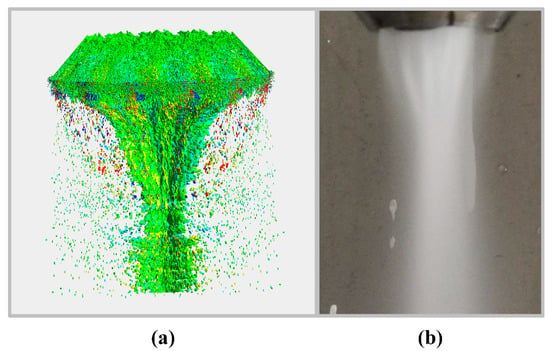

A preliminary water model experiment was conducted to validate the liquid breakup process during gas atomization. However, due to absence of a physical NET atomizer prototype, the experimental investigation was limited to the ET atomizer. The comparison between the numerical simulation result and the water simulation result of the ET atomizer atomization process was illustrated in Figure 5. It can be observed that a “cone interface” structure existed in the water atomization process of the ET atomizer, accompanied by numerous small droplets surrounding this interface. Furthermore, downstream from the conical interface, a new relatively continuous gas–liquid interface formed after collision and coalescence of the liquid structure, diffusing downstream at a certain angle with respect to the axis, which aligned well with the numerical simulation result.

Figure 5.

Comparison between numerical simulation (a) and water simulation experiment (b) for the ET atomizer.

3.2. Main Gas–Liquid Interface Development

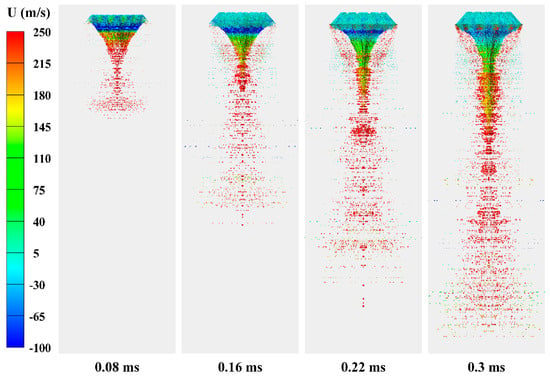

The evolution of the gas atomization process of the molten aluminum for the ET atomizer was depicted in Figure 6. It can be observed that the atomization process of molten aluminum progressed rapidly with the ET atomizer. The liquid ligaments at the leading edge of the “conical” gas–liquid interface were on the verge of convergence at 0.08 ms, with large droplets detaching from the leading edge and small droplets being generated downstream. At 0.16 ms, the liquid ligaments at the leading edge of the “conical” gas–liquid interface closed, and the gas–liquid interface continued to develop downstream. Due to stronger gas–liquid interaction near the nozzle outlet, numerous small droplets were generated at this location and moved downstream with nitrogen. By 0.3 ms, the “conical” gas–liquid interface had evolved into a “conical” liquid core with many short liquid ligament structures present on it; additionally, there were many small droplets between these liquid ligaments and in radial directions throughout the calculation domain.

Figure 6.

Evolution of the gas atomization process of molten aluminum for ET atomizer.

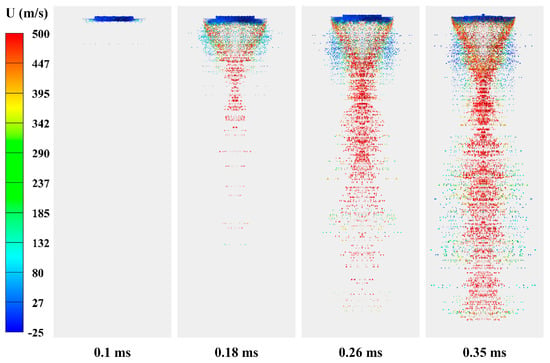

The evolution of the gas atomization process of molten aluminum for the NET atomizer was illustrated in Figure 7. It can be observed that compared to the ET atomizer, the gas atomization process of molten aluminum in the NET atomizer exhibited a slower development rate. At 0.1 ms, a “pancake shape” gas–liquid interface was formed, and due to the influence of the recirculation zone, liquid ligaments and large droplets detached from the interface and were transported towards the nozzle outlet along the radial direction. This stage represented the primary atomization phase of molten aluminum for the NET atomizer. At 0.2 ms, under the effect of the main nitrogen jet, larger droplets underwent further breakup into smaller ones with reduced particle size. As time progressed, newly generated primary atomized droplets advanced towards the nozzle outlet where they experience secondary breakup by the main nitrogen jet, while early secondary atomized droplets have already moved downstream within the computational domain region. By 0.35 ms, droplets formed during earlier stages reached the computational domain outlet.

Figure 7.

Evolution of the gas atomization process of molten aluminum for NET atomizer.

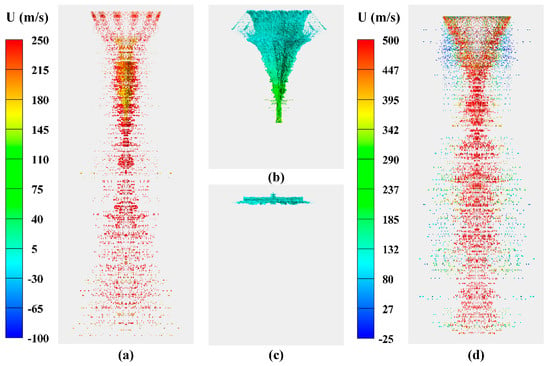

The main body of the gas–liquid interface in the gas atomization process for the ET atomizer and the NET atomizer was depicted in Figure 8b,c. The different end geometries of the diversion tube led to distinct flow fields of nitrogen between these two types of atomizers in the atomization chamber, resulting in a conical shape for the gas–liquid interface in the ET atomizer and a pancake shape for the NET atomizer. Figure 8a,d illustrated the droplet distribution during gas atomization with both the ET and NET atomizers. It can be observed that in the gas atomization process using an ET atomizer, droplets were sparsely distributed in both the upper and lower regions within the calculation domain, while they were concentrated around the middle region. Conversely, droplets from an NET atomizer were evenly distributed throughout the calculation domain traversed by the primary nitrogen jet during atomization. Based on Figure 4, it can be inferred that differences in gas flow field during gas atomization caused variations in droplet distribution between these two types of atomizers during their respective processes. Table 2 compared the size and number characteristics of droplets produced by both types of atomizers (droplet distributions shown in Figure 8a,d). The mean droplet size defined in this study was the ratio of the total volume of all droplets to the total surface area of all droplets within the atomized droplet region. The calculation of the average droplet size was based on the methodologies established in previous work [24]. The results indicated that the average particle size of aluminum droplets generated by the ET atomizer was larger, with a smaller quantity, whereas the average particle size of aluminum droplets produced by the NET atomizer was smaller, with a greater quantity. This phenomenon can be attributed to the fundamental differences between the two atomizers in terms of energy utilization and breakup mechanisms. In ET atomizers, both primary and secondary atomization occurred near the liquid core, where the enlarged surface area dissipates significant kinetic energy from the atomizing gas, thereby weakening aerodynamic forces for secondary droplet breakup. Additionally, the high-density atomization zone surrounding the liquid core promoted droplet collisions, further increasing droplet size. Conversely, in NET atomizers, molten aluminum underwent primary atomization via shear forces in the recirculation zone, followed by secondary break up driven directly by the main nitrogen jet. This configuration concentrated most of the jet kinetic energy on droplet break up, while eliminating the collision-prone liquid core region, resulting in smaller droplet diameters.

Figure 8.

Comparison of main gas-liquid interface (b,c) and droplet distribution (a,d) between ET atomizer and NET atomizer.

Table 2.

Size and number characteristics of droplets produced by both types of atomizers.

The mechanism diagram of molten aluminum’s gas atomization for the NET and ET atomizers was illustrated in Figure 9. In the case of the NET atomizer, nitrogen was injected into the atomization chamber at a specific angle, resulting in its division into two parts: the recirculation zone and the main nitrogen jet. The primary atomization of molten aluminum occurred due to the interaction between the nitrogen flow in the recirculation zone and the molten aluminum at the exit of the delivery tube. Under both shear forces within the recirculation zone and surface tension at the gas–liquid interface, stretching and curling along radial directions took place on the interface, leading to separation of complex liquid structures as well as large droplets from the main body of molten aluminum. These primary breakup liquid structures were then transported towards the region near the nozzle outlet by recirculation zone. Secondary atomization took place within an area flowing through the main nitrogen jet inside an atomization chamber, where primary droplets undergo further decomposition under high-speed impact from the jet, thus forming new smaller droplets more abundantly. Throughout this entire process, primary atomization was primarily governed by nitrogen flow within the recirculation zone, while secondary atomization was dominated by the main nitrogen jets instead. For the ET atomizer, the nitrogen from the nozzle impacted the molten aluminum at a specific angle, resulting in the gradual formation of a “conical” liquid core through continuous outflow and gas–liquid interaction. Unlike the NET atomizer, the primary atomization area for the ET atomizer was located near the interface of the “conical” liquid core, where numerous short liquid ligament structures were generated at the interface and primary atomized liquid structures were separated. This can be observed in Figure 9b by referring to the blue virtual curve marking this area. The secondary atomization zone, marked by a black virtual curve near the primary atomization zone in Figure 9b, encompassed both surrounding areas and downstream regions of the “conical” liquid core.

Figure 9.

Schematic diagram of gas atomization mechanism of molten aluminum in NET atomizer (a) and ET atomizer (b).

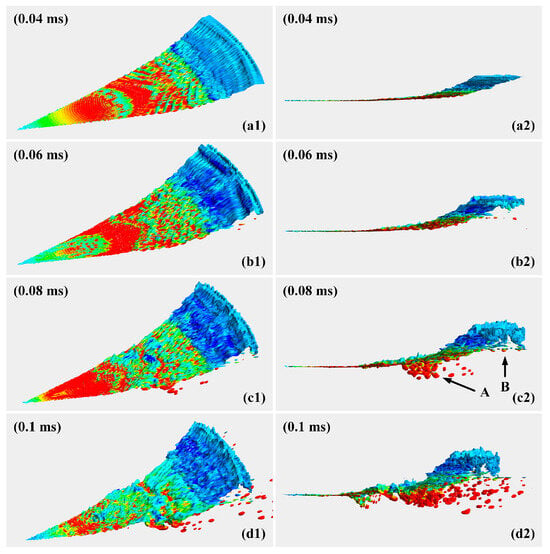

3.3. Surface Wave Initiation and Development

The formation process of surface waves and droplets on the gas–liquid interface at the outlet of the NET atomizer was illustrated in Figure 10. To provide a clearer observation of the surface waves and droplet formation beneath the interface, the evolution of the gas–liquid interface over time was presented from two perspectives. As depicted in Figure 10, radial unstable surface waves were observed at each stage on the gas–liquid interface due to velocity differences, known as Kelvin–Helmholtz unstable waves. At the initial stage of atomization (0.04 ms), surface waves appeared on the interface; however, no distinct liquid structures such as liquid ligaments or large droplets have separated from it yet. Over time, the recirculation zone gradually formed beneath the interface, leading to an increase in gas–liquid relative velocity in that region. Consequently, fluctuations intensified on the interface while both wavelength and amplitude progressively increased. During unstable wave development stages, stretching actions within recirculation regions caused the gradual elongation of surface wave wavelengths. This resulted in short liquid ligament structures forming within trough regions, which quickly detached from and striped off from interfaces to form primary atomized droplets below them (as shown in Figure 10(b2)–(d2)). Additionally, Figure 10 revealed that regions A and B exhibited longer wavelengths and higher amplitudes on their respective sections, along with variations related to the locations of recirculation zone centers. In surface wave theory, there existed another circumferential unstable surface wave known as the Rayleigh–Taylor wave. It was widely accepted that density differences cause Rayleigh–Taylor instability waves, which are mostly present during rotating jet atomization processes. However, for the close-coupled gas atomization process examined in this study, it can be inferred that Kelvin–Helmholtz instability waves dominated the formation and development of initial droplets due to the very low nitrogen gas velocity in the circumference direction.

Figure 10.

Temporal evolution of surface waves at the gas–liquid interface near the exit of NET atomizer delivery tube: (a1,a2) 0.04 ms; (b1,b2) 0.06 ms; (c1,c2) 0.08 ms; (d1,d2) 0.1 ms (Labels 1 and 2 represent the gas-liquid interface observed simultaneously from two distinct viewing angles).

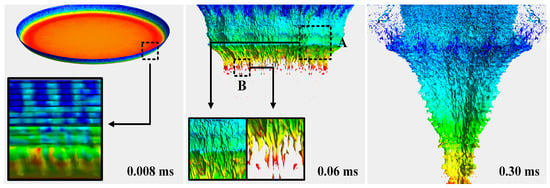

The evolution of surface waves at the gas–liquid interface during the formation of the liquid core for the ET atomizer was illustrated in Figure 11. It can be observed that gas/liquid interaction occurred very early for the ET atomizer. The gas–liquid interface exhibited small surface waves at 0.008 ms, which arose from the velocity disparity at this interface. This surface wave propagated along the axial direction and can be attributed to the Kelvin–Helmholtz instability phenomenon. As time progressed, the liquid core extended downstream along its axial direction and stretched out the surface wave on its interface, resulting in a significant increase in wavelength compared to its initial stage. When reaching a certain size, both the liquid ligaments (as shown in area B in the figure) and droplets separated from this surface wave at 0.06 ms, as depicted in Figure 11. Eventually, the liquid core underwent closure and transformed into a “conical” shape with the development of a gas–liquid interface along the axis.

Figure 11.

Formation and development of surface waves during gas atomization for ET atomizer.

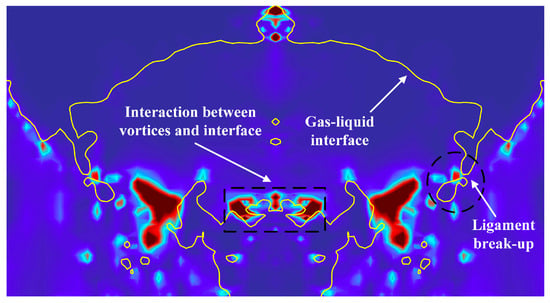

The vorticity contour of a specific plane at the leading edge of the gas–liquid interface during the initial stage of atomization for the ET atomizer was illustrated in Figure 12. Here, the yellow solid line represented the gas–liquid interface, while the color gradient on the contour map indicated varying levels of vorticity (deep red denoting strong vorticity and purple indicating weak vorticity). It can be observed that predominantly strong vortices were present in the “trough” area along the gas–liquid boundary. The presence of these intense vortices suggested the gas in this region exhibited significant rotational motion, resulting in substantial shear forces acting upon the gas–liquid interface. Additionally, a distinct zone with high vorticity was also observed within the “trough” region of the liquid ligament. Over time, these liquid ligaments gradually thinned until they eventually ruptured.

Figure 12.

Vorticity contour of a special plane of the interface front.

3.4. Ligament and Droplet Formation

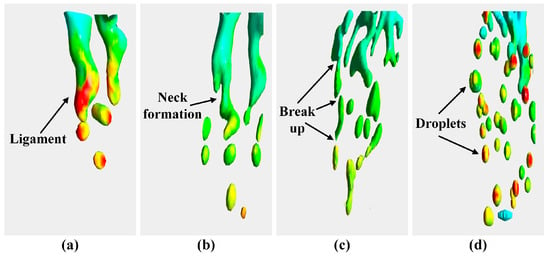

After the formation of liquid ligaments in the initial stage of gas atomization in ET atomizer, these ligaments underwent further breakup to form droplet structures. As depicted in Figure 13a, due to the stretching effect caused by axial airflow and the instability of local flow field, the liquid ligaments exhibited an irregular shape, while surface tension hindered its stretching and deformation at the interface. Under the influence of local turbulent exerted by gas, the cross-sectional diameter of the liquid ligaments varied. As the liquid ligaments progressed downstream, it gradually elongated into multiple liquid neck structures as illustrated in Figure 13b. It was worth noting that during the formation process of a liquid neck structure, apart from being influenced by local gas vortex structure, surface tension caused inward shrinkage of the liquid neck which promoted its formation and subsequent breakup. As shown in Figure 13c,d, after breakup occurred at the necks of a given liquid ligament, the two ends of several ligaments gradually contracted under the influence of surface tension, resulting in near-spherical droplet structures with different sizes.

Figure 13.

Process of droplet formation by the breakup of liquid ligament for liquid film front during early stage of gas atomization: (a) ligament formation; (b) neck formation; (c) ligament break up; (d) droplets formation.

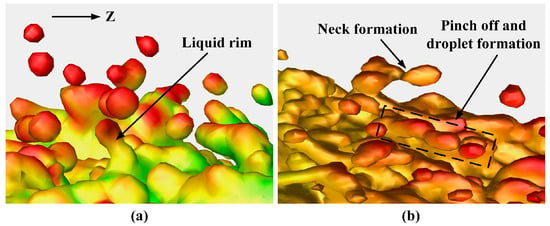

In the atomization process of the ET atomizer, a majority of droplets were generated at the surface of the liquid core. As depicted in Figure 14a, under the influence of axial air flow, the liquid core progressed downstream and formed liquid rim structures on its surface due to local vortex structures. The liquid rim structure gradually elongated with aerodynamic force, resulting in narrow liquid neck structure, as shown in Figure 14b. As mentioned earlier, the shear action from vortex structures caused thinning of the liquid neck position on the liquid rim structure while surface tension promoted separation at its front end. Eventually, with the rupture of the neck structure, droplets detached from the liquid rim structure and progressively assumed a spherical shape through surface tension effects, forming discrete droplets as indicated by the section marked within the black dashed box in Figure 14b.

Figure 14.

Formation process of droplets on the liquid core surface during gas atomization: (a) liquid rim formation; (b) formation of neck and droplet.

4. Conclusions

In this study, the gas atomization processes of two atomizers with distinct delivery tube end geometries were investigated by coupling LES with the VOF model. Adaptive mesh refinement technology and periodic boundary conditions were employed to enhance the accuracy and efficiency of the simulations. The formation and evolution of surface waves, liquid cores, liquid ligaments, and droplets during the gas atomization process were systematically analyzed. The key findings were summarized as follows:

- (1)

- For the NET atomizer, the recirculation zone primarily governed the primary breakup of molten metal. Subsequently, primary droplets were further broken into secondary droplets under the influence of the main nitrogen jet. In contrast, for the ET atomizer, the “conical” liquid core formed gradually due to the action of the atomizing gas, numerous primary droplets were separated from the liquid core, which were subsequently broken up by the gas. Compared to the ET atomizers, the NET atomizers produced droplets with a smaller average size.

- (2)

- The Kelvin–Helmholtz instability was identified as the dominant mechanism responsible for the primary breakup of the molten metal. For the ET atomizer, primary droplets were predominantly formed through the fracture of the liquid ligaments at the leading edge of the liquid film and the tensile rupture at the interface of the liquid core. For the NET atomizer, the shear-induced stretching effect within the recirculation zone caused the detachment of liquid ribbons and droplets from the “pancake-shaped” interface at the delivery tube exit.

Author Contributions

Y.W.: methodology; software; validation; formal analysis; investigation; writing—original draft preparation, B.W.: resources; writing—review and editing, J.Z.: conceptualization; resources, C.C.: data curation; writing—review and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their gratitude for the numerical calculation support by High-Performance Computing Center of Wuhan University of Science and Technology.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| LES | large eddy simulation |

| VOF | volume of fluid |

| AMR | adaptive mesh refinement |

References

- Srivastava, M.; Rathee, S. Additive manufacturing: Recent trends, applications and future outlooks. Prog. Addit. Manuf. 2022, 7, 261–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatia, A.; Sehgal, A.K. Additive manufacturing materials, methods and applications: A review. Mater. Today Proc. 2023, 81, 1060–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bałasz, B.; Bielecki, M.; Gulbiński, W.; Słoboda, Ł. Comparison of ultrasonic and other atomization methods in metal powder production. J. Achiev. Mater. Manuf. Eng. 2023, 116, 11–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.-X.; Chen, C.-Y.; Shen, L.-Y.; Xuan, W.-D.; Li, X.-G.; Shuai, S.-S.; Li, X.; Hu, T.; Li, C.-J.; Yu, J.-B.; et al. Atomization mechanism and powder morphology in laminar flow gas atomization. Acta Phys. Sin. 2021, 70, 128–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, Q. Research advances in close-coupled atomizer flow and atomizing mechanisms. Sov. Powder Metall. Met. Ceram. 2023, 62, 400–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urionabarrenetxea, E.; Martín, J.M.; Avello, A.; Rivas, A. Simulation and validation of the gas flow in close-coupled gas atomisation process: Influence of the inlet gas pressure and the throat width of the supersonic gas nozzle. Powder Technol. 2022, 407, 117688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prashanth, W.; Thotarath, S.L.; Sarkar, S.; Anand, T.; Bakshi, S. Experimental investigation on the effect of melt delivery tube position on liquid metal atomization. Adv. Powder Technol. 2021, 32, 693–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aksoy, A.; Ünal, R. Effects of gas pressure and protrusion length of melt delivery tube on powder size and powder morphology of nitrogen gas atomised tin powders. Powder Metall. 2006, 49, 349–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Wang, P.; Li, X.; Zhang, J. Effects of delivery tube configuration regarding the gas atomization for preparing Fe-based amorphous powders: Numerical and experimental investigation. Powder Metall. 2024, 67, 181–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Yu, Q.; Yu, W.; Wang, L. Investigation of the influence of the delivery tube position on liquid aluminum atomization. Ferroelectrics 2024, 618, 2355–2367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motaman, S.; Mullis, A.M.; Cochrane, R.F.; Borman, D.J. Numerical and experimental investigations of the effect of melt delivery nozzle design on the open- to closed-wake transition in closed-coupled gas atomization. Metall. Mater. Trans. B 2015, 46, 1990–2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y. Research About the Effect of Atomization on Modification at the End of Delivery Tube with Close-Coupled Atomizer. Master’s Thesis, North University of China, Taiyuan, China, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Xia, M.; Wu, J.; Ge, C. Nozzle clogging in vacuum induction melting gas atomization: Influence of the delivery-tube and nozzle coupling. Arch. Metall. Mater. 2022, 67, 1359–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Xia, M.; Wu, J.; Ge, C. Nozzle clogging in vacuum induction melting gas atomisation: Influence of gas pressure and melt orifice diameter coupling. Powder Metall. 2023, 66, 281–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeoli, N.; Tabbara, H.; Gu, S. Three-dimensional simulation of primary break-up in a close-coupled atomizer. Appl. Phys. A 2012, 108, 783–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeoli, N.; Tabbara, H.; Gu, S. CFD modeling of primary breakup during metal powder atomization. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2011, 66, 6498–6504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brackbill, J.; Kothe, D.; Zemach, C. A continuum method for modeling surface tension. J. Comput. Phys. 1992, 100, 335–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, L.; Wang, G.; Qu, X. Review on the recent numerical studies of liquid atomization. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 4928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, P.J. Large-eddy simulation: A critical review of the technique. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 1994, 120, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Bou-Zeid, E. Contrasts between momentum and scalar transport over very rough surfaces. J. Fluid Mech. 2019, 880, 32–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, S.J. Turbulence. An introduction to its mechanism and theory. Science 1960, 131, 1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lilly, D.K. A proposed modification of the Germano subgrid-scale closure method. Phys. Fluids A Fluid Dyn. 1992, 4, 633–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirt, C.W.; Nichols, B.D. Volume of fluid (VOF) method for the dynamics of free boundaries. J. Comput. Phys. 1981, 39, 201–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Dang, Y.-C.; Chen, X.-Q.; Wang, B.; Liu, Z.-Q.; Zhou, J.-A.; Chen, C.-Y. Numerical simulation of effect of various parameters on atomization in an annular slit atomizer. J. Iron Steel Res. Int. 2023, 30, 1128–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.