Thermal Data Optimization Through Uncertainty Reduction in Fatigue Limits Estimation: A TCM–ANN Framework for C45 Steel

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

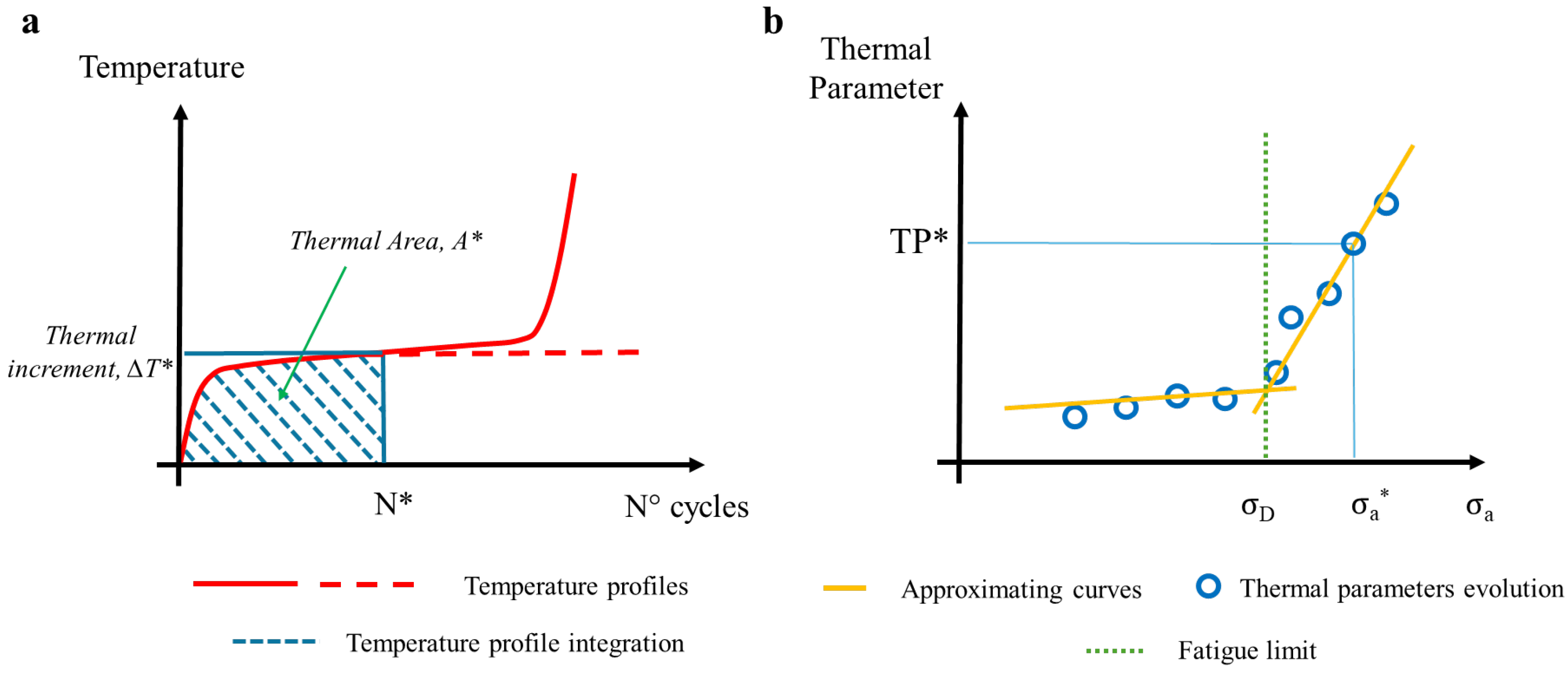

2.1. Thermographic Method

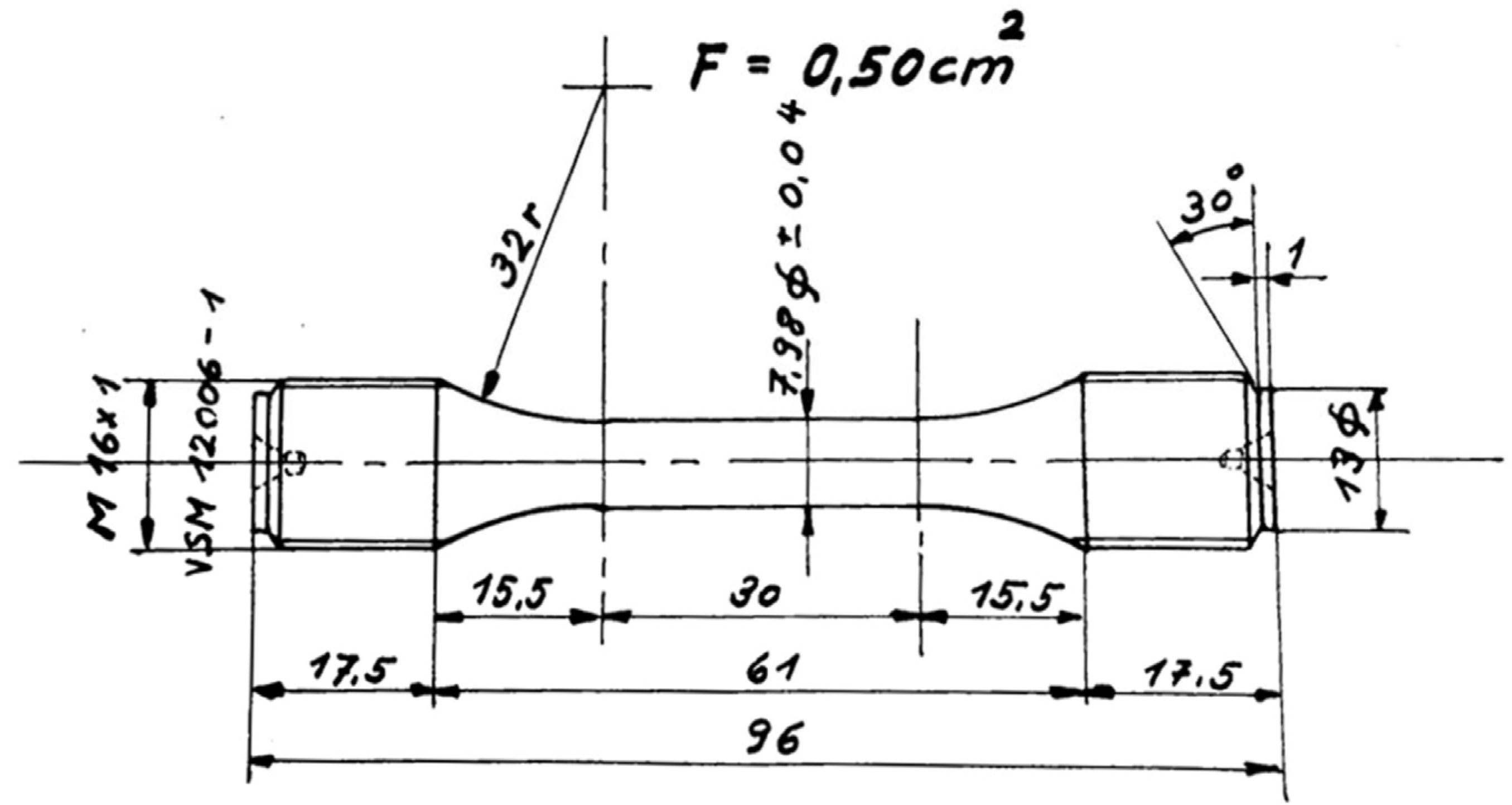

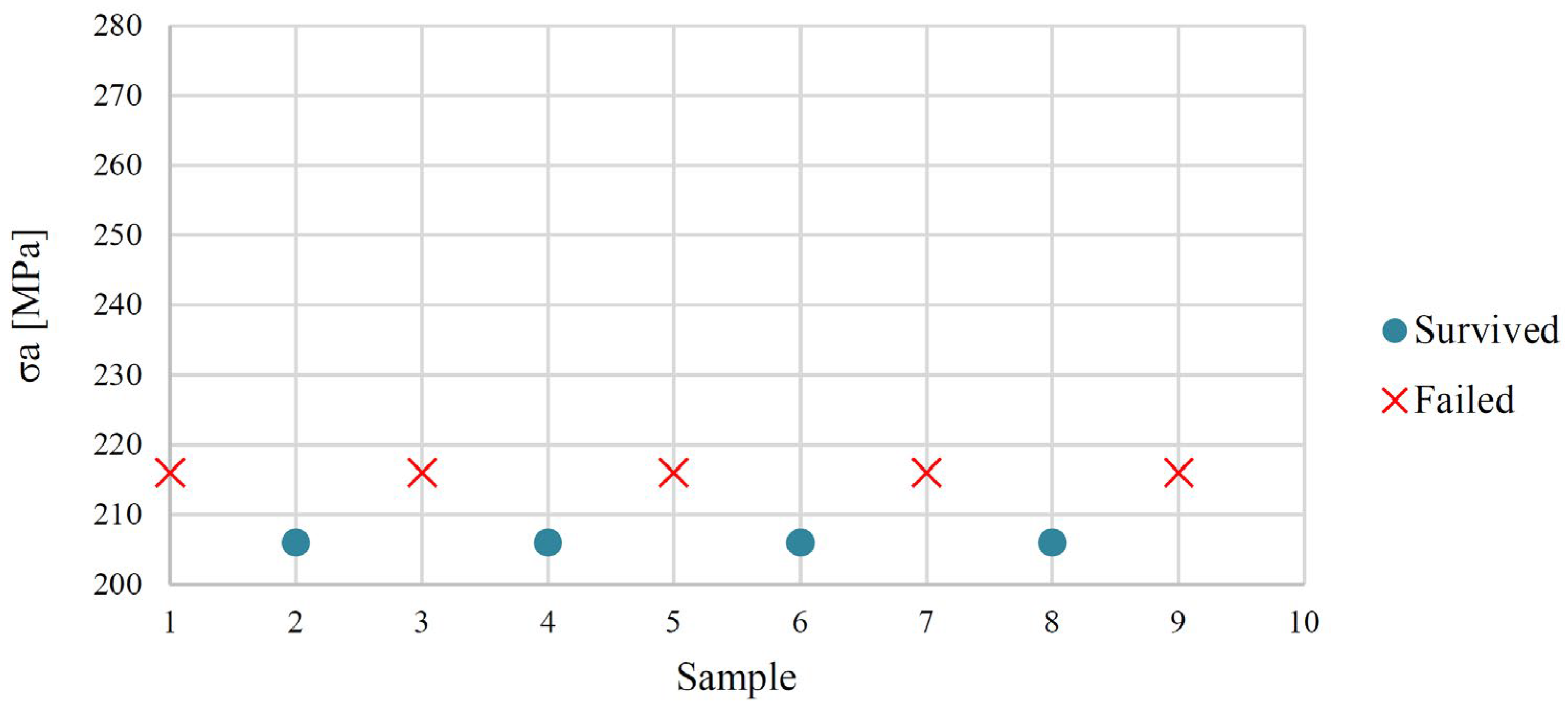

2.2. Experimental Procedure

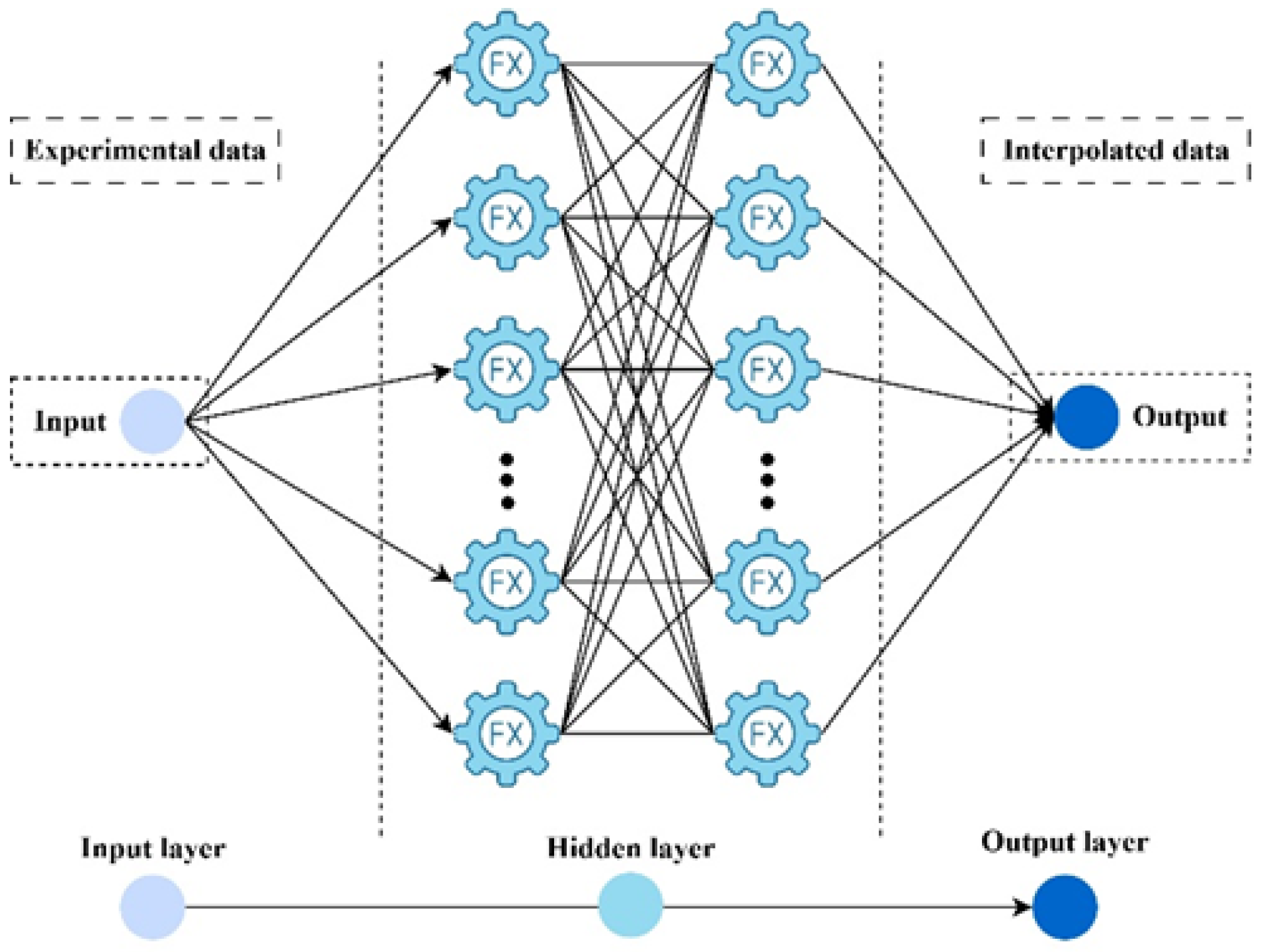

2.3. Artificial Neural Network (ANN)

2.4. Accuracy Metrics

2.5. Cross-Validation Strategy

2.6. Uncertainty Reduction

- (1)

- Campaign mean (central estimate):

- (2)

- Range between campaigns (transparent dispersion indicator):

- (3)

- Sample standard deviation (Type A dispersion):

- (4)

- Type A standard uncertainty of the mean (repeatability of the estimated mean):

- (5)

- Degrees of freedom (reported for completeness):

- (6)

- Deviation from staircase reference (accuracy vs. SC):

- (7)

- Uncertainty reduction index (relative to baseline Case 0):

2.7. Case Studies

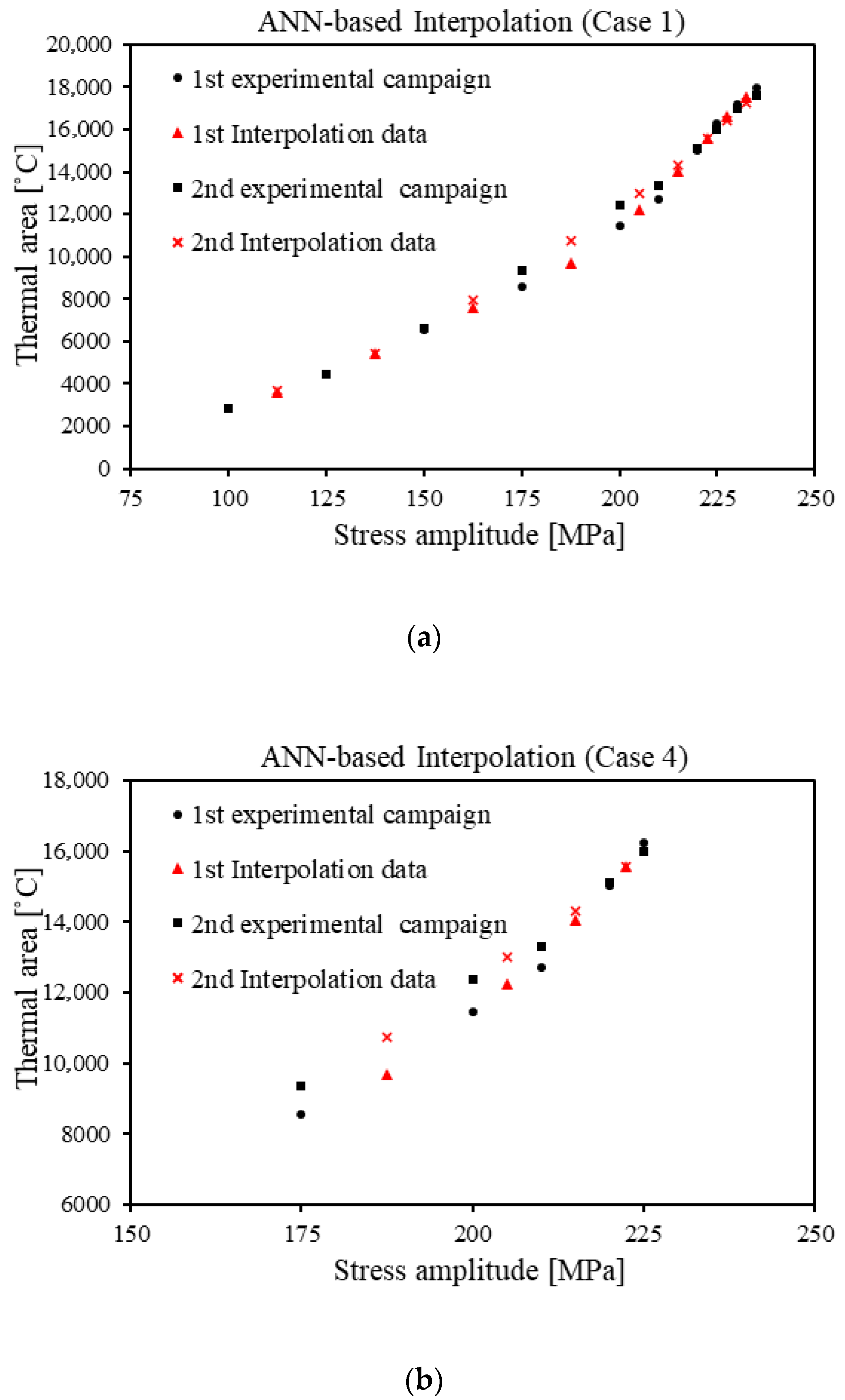

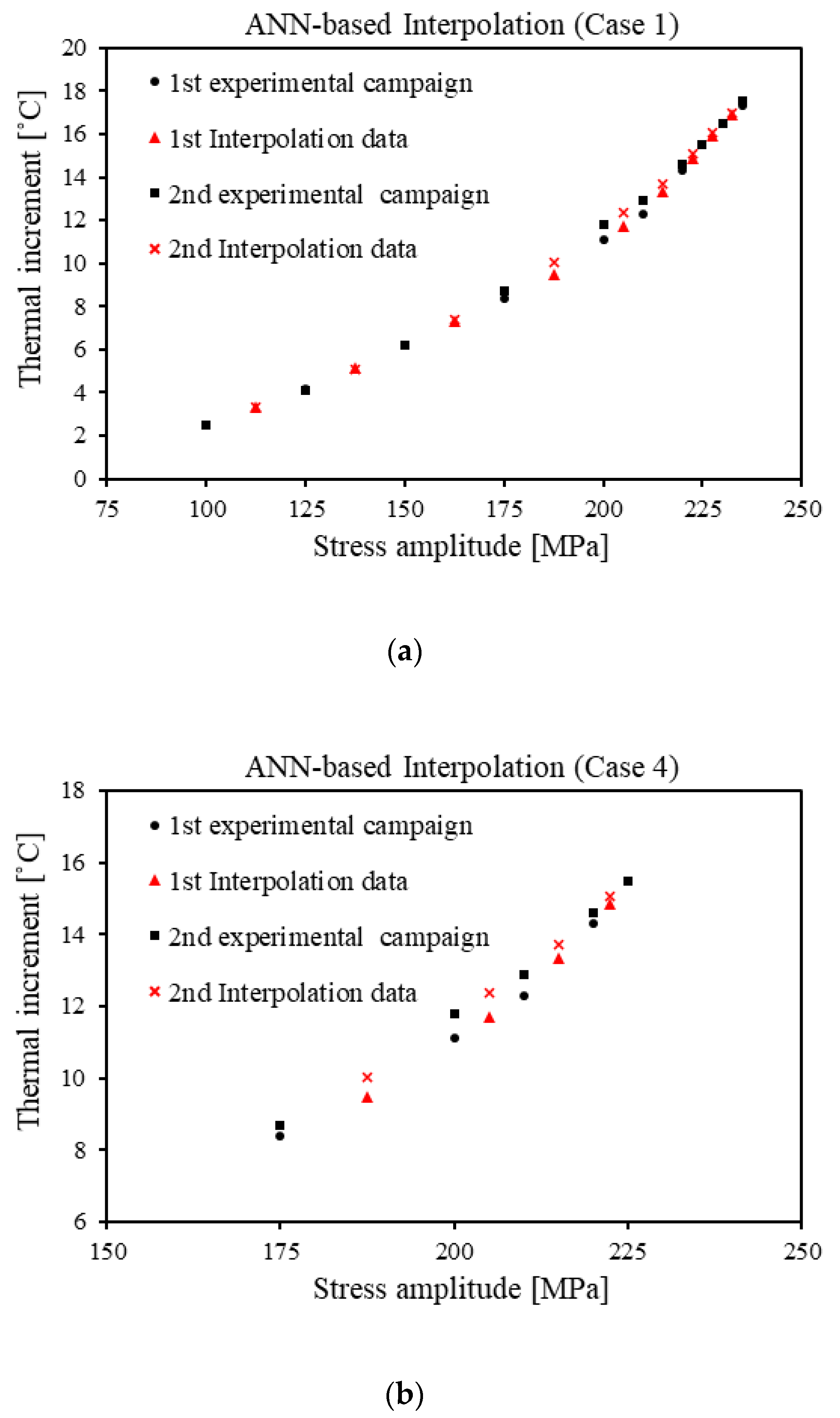

- Case 1 (10 points for the entire original dataset—19 points for the optimised dataset after the augmentation): the first possibility used the entire original dataset (Case 0) as the starting point for the augmentation.

- Case 2 (5 points for the entire original dataset—9 points for the optimised dataset after the augmentation): the second possibility considered for the augmentation only half (5 points) of the original dataset (Case 0).

- Case 3 (6 points for the original dataset—11 points for the optimised dataset after the augmentation): the first case of the second optimisation strategy involved the selection of only six central points from the original dataset (Case 0) as the starting point.

- Case 4 (5 points for the original dataset—9 points for the optimised dataset after the augmentation): in the second case, only five central points were considered as the starting point for the augmentation.

- Case 5 (optimised dataset composed of 14 points, 5 external points from the original dataset and 9 central points from the result of Case 4): an optimised dataset composed of an augmented central part (more specifically, the Case 4) was located inside the original dataset (Case 0).

3. Results

3.1. ANN-Based Interpolation Accuracy

3.2. Residual Analysis

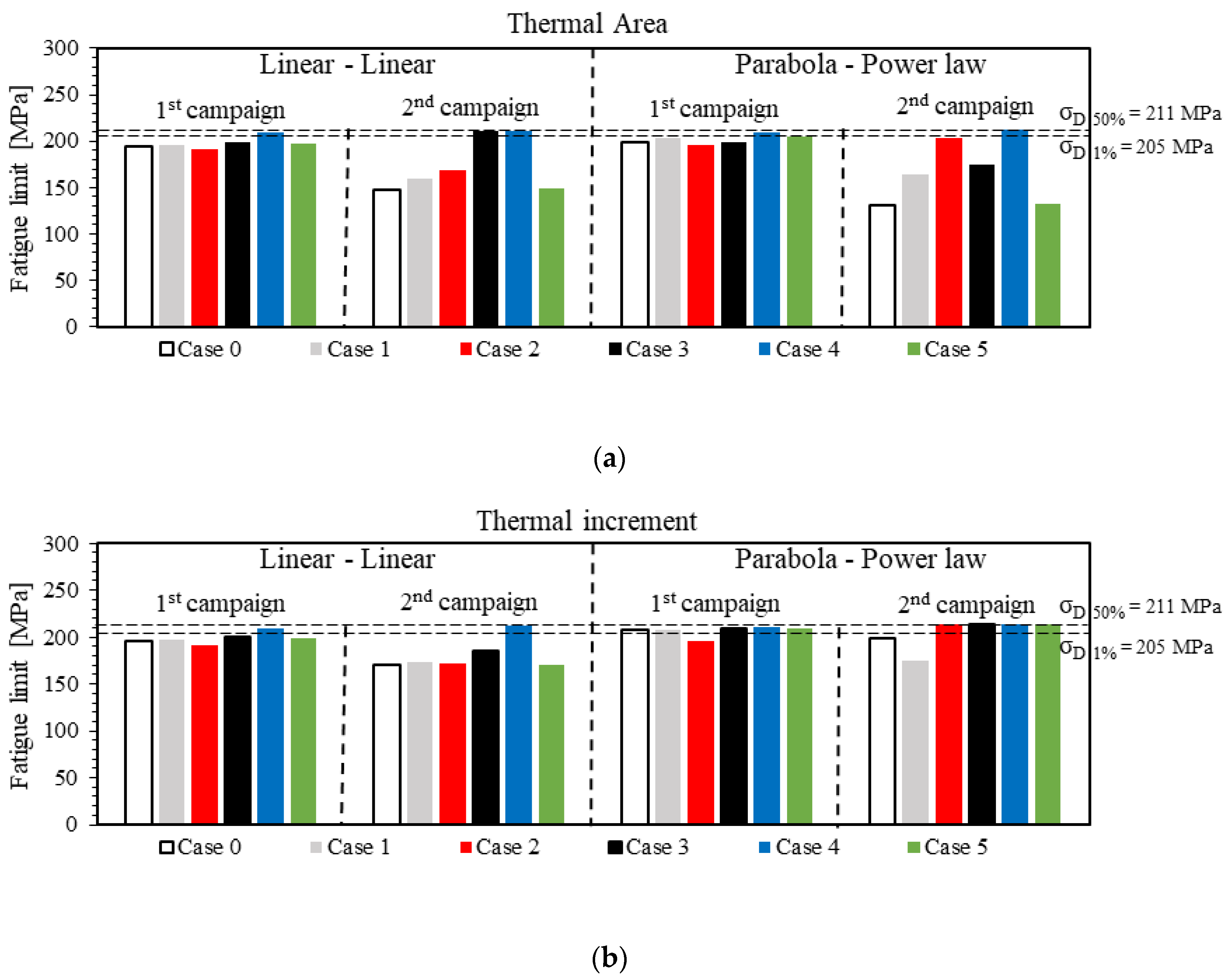

3.3. TCM Using ANN-Augmented Datasets

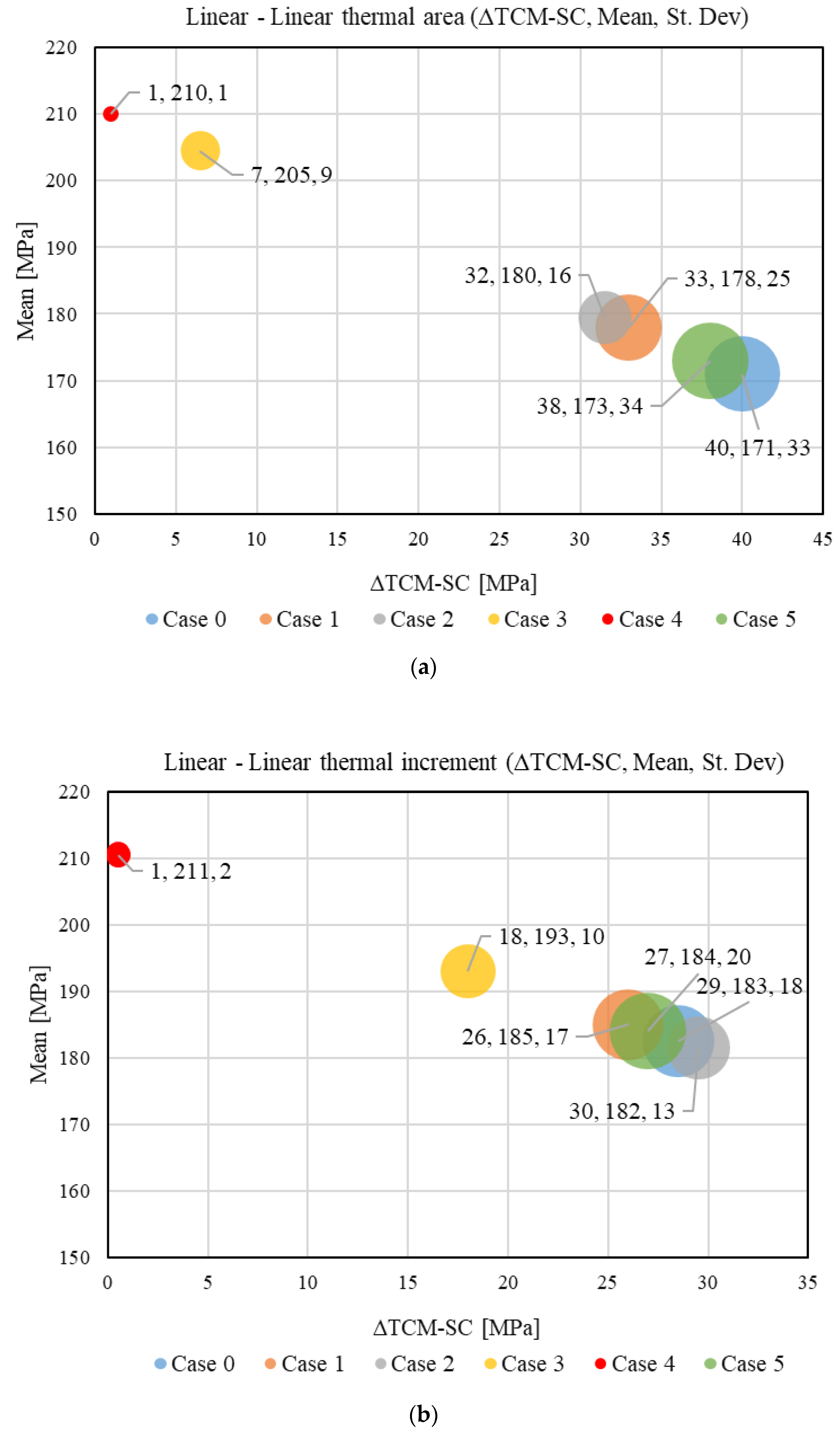

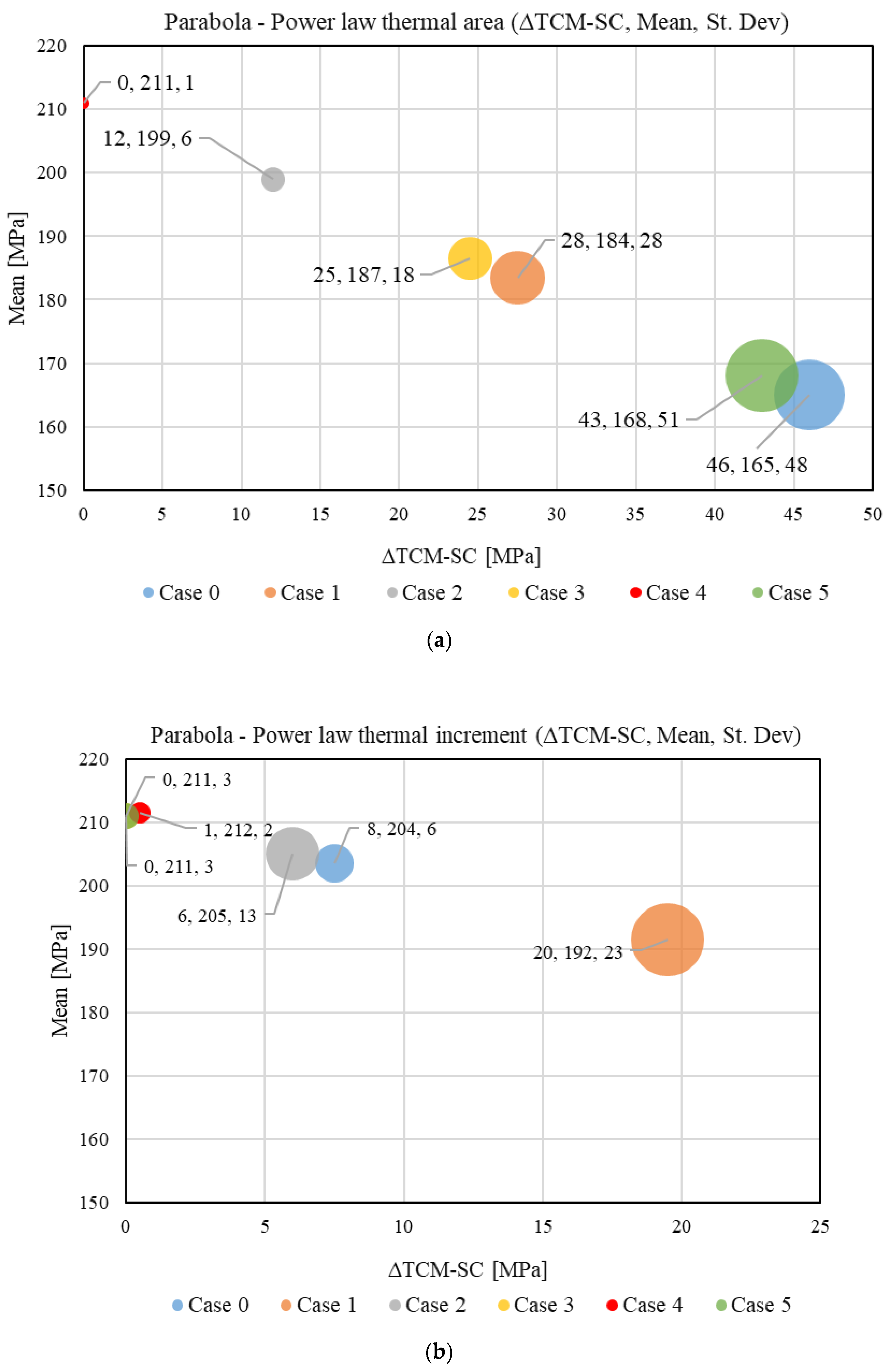

3.4. Uncertainty-Reduction Results

3.5. Case Comparison

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Maldague, X. Nondestructive evaluation of materials by infrared thermography. NDT E Int. 1996, 6, 396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doshvarpassand, S.; Wu, C.; Wang, X. An overview of corrosion defect characterization using active infrared thermography. Infrared Phys. Technol. 2019, 96, 366–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attermo, R.; Östberg, G. Measurements of the temperature rise ahead of a fatigue crack. Int. J. Fract. Mech. 1971, 7, 122–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luong, M.P. Infrared thermographic scanning of fatigue in metals. Nucl. Eng. Des. 1995, 158, 363–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curti, G.; Geraci, A.; Risitano, A. Un nuovo metodo per la determinazione rapida del limite di fatica. ATA 1989, 10, 634–636. [Google Scholar]

- BS ISO 12107:2003; Metallic Materials: Fatigue Testing: Statistical Planning and Analysis of Data. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2003.

- La Rosa, G.; Risitano, A. Thermographic methodology for rapid determination of the fatigue limit of materials and mechanical components. Int. J. Fatigue 2000, 22, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fargione, G.; Geraci, A.; La Rosa, G.; Risitano, A. Rapid determination of the fatigue curve by the thermographic method. Int. J. Fatigue 2002, 24, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curà, F.; Curti, G.; Sesana, R. A new iteration method for the thermographic determination of fatigue limit in steels. Int. J. Fatigue 2005, 27, 453–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curà, F.; Gallinatti, A.E.; Sesana, R. Dissipative aspects in thermographic methods. Fatigue Fract. Eng. Mater. Struct. 2012, 35, 1133–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoudi, A.; Khonsari, M.M. Rapid evaluation of fatigue limit using energy dissipation. Fatigue Fract. Eng. Mater. Struct. 2023, 46, 2156–2167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stergiou, K.; Ntakolia, C.; Varytis, P.; Koumoulos, E.; Karlsson, P.; Moustakidis, S. Enhancing property prediction and process optimization in building materials through machine learning: A review. Comput. Mater. Sci. 2023, 220, 112031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basheer, I.A.; Hajmeer, M. Artificial neural networks: Fundamentals, computing, design, and application. J. Microbiol. Methods 2000, 43, 3–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opěla, P.; Schindler, I.; Kawulok, P.; Kawulok, R.; Rusz, S.; Navrátil, H. On various multi-layer perceptron and radial basis function based artificial neural networks in the process of a hot flow curve description. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2021, 14, 1837–1847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tize Mha, P.; Dhondapure, P.; Jahazi, M.; Tongne, A.; Pantalé, O. Interpolation and Extrapolation Performance Measurement of Analytical and ANN-Based Flow Laws for Hot Deformation Behavior of Medium Carbon Steel. Metals 2023, 13, 633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kebede, H.; Demissie, Z.; Tadesse, H.; Eshetu, A. Spatial interpolation techniques comparison and evaluation: The case of ground-based gravity and elevation datasets of the central Main Ethiopian rift. Heliyon 2024, 10, e32806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.; Yu, H.; Guo, C.; Chen, X.; Zhong, S.; Zhou, L.; Osman, A.; Lu, J. Review on Fatigue of Additive Manufactured Metallic Alloys: Microstructure, Performance, Enhancement, and Assessment Methods. Adv. Mater. 2024, 36, 2306570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, C.; Saha, S.; Guo, J.; Zhang, H.; Xie, X.; Bessa, M.A.; Qian, D.; Chen, W.; Wanger, G.J.; Cao, J.; et al. Unifying machine learning and interpolation theory via interpolating neural networks. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 8753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bučar, T.; Nagode, M.; Fajdiga, M. A neural network approach to describing the scatter of S–N curves. Int. J. Fatigue 2006, 28, 311–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marković, E.; Marohnić, T.; Basan, R. A Surrogate Artificial Neural Network Model for Estimating the Fatigue Life of Steel Components Based on Finite Element Simulations. Materials 2025, 18, 2756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivasan, D.V.; Moradi, M.; Komninos, P.; Zarouchas, D.; Vassilopoulos, A.P. A generalized machine learning framework to estimate fatigue life across materials with minimal data. Mater. Des. 2024, 246, 113355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, K.; Peng, S.; Sun, Z. An artificial neural network model for fatigue damage analysis of wide-band non-Gaussian random processes. Appl. Ocean Res. 2024, 144, 103896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández, J.; Chiachío, M.; Chiachío, J.; Muñoz, R.; Herrera, F. Uncertainty quantification in Neural Networks by Approximate Bayesian Computation: Application to fatigue in composite materials. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2022, 107, 104511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corsaro, L. Passive and Active Thermography for Surface Treatments Characterization in Spur Gears; Politecnico di Torino: Torino, Italy, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Qian, H.; Zheng, J.; Wang, Y.; Jiang, D. Fatigue Life Prediction Method of Ceramic Matrix Composites Based on Artificial Neural Network. Appl. Compos. Mater. 2023, 30, 1251–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corsaro, L.; Dehghanpour Abyaneh, M.; Curà, F.; Sesana, R. Thermographic and Machine Learning approaches for a rapid estimation of gears bending fatigue strength. Forsch. Im Ingenieurwesen 2025, 89, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehteshamfar, M.V.; Javadi, M.S.; Adibi, H. Surface modification of prototypes in fused deposition modelling using lapping process. Rapid Prototyp. J. 2022, 28, 1382–1393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehghanpour Abyaneh, M.; Narimani, P.; Javadi, M.S.; Golabchi, M.; Attarsharghi, S.; Hadad, M. Predicting Surface Roughness and Grinding Forces in UNS S34700 Steel Grinding: A Machine Learning and Genetic Algorithm Approach to Coolant Effects. Physchem 2024, 4, 495–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javadi, M.S.; Ehteshamfar, M.V.; Adibi, H. A comprehensive analysis and prediction of the effect of groove shape and volume fraction of multi-walled carbon nanotubes on the polymer 3D-printed parts in the friction stir welding process. Polym. Test. 2023, 117, 107844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodson, T.O. Root-mean-square error (RMSE) or mean absolute error (MAE): When to use them or not. Geosci. Model Dev. 2022, 15, 5481–5487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azarafza, M.; Hajialilue Bonab, M.; Derakhshani, R. A Deep Learning Method for the Prediction of the Index Mechanical Properties and Strength Parameters of Marlstone. Materials 2022, 15, 6899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, T.; Draxler, R.R. Root mean square error (RMSE) or mean absolute error (MAE)?—Arguments against avoiding RMSE in the literature. Geosci. Model Dev. 2014, 7, 1247–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H.; Garrick, D.J.; Fernando, R.L. Efficient strategies for leave-one-out cross validation for genomic best linear unbiased prediction. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 2017, 8, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, J.; Dekkers, J.C.M.; Fernando, R.L. Cross-validation of best linear unbiased predictions of breeding values using an efficient leave-one-out strategy. J. Anim. Breed. Genet. 2021, 138, 519–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geroldinger, A.; Lusa, L.; Nold, M.; Heinze, G. Leave-one-out cross-validation, penalization, and differential bias of some prediction model performance measures—A simulation study. Diagn. Progn. Res. 2023, 7, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartlett, J.W.; Frost, C. Reliability, repeatability and reproducibility: Analysis of measurement errors in continuous variables. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2008, 31, 466–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jcgm, J. Evaluation of measurement data—Guide to the expression of uncertainty in measurement. Int. Organ. Stand. Geneva ISBN 2008, 50, 134. [Google Scholar]

- De Bièvre, P. The 2007 International Vocabulary of Metrology (VIM), JCGM 200: 2008 [ISO/IEC Guide 99]: Meeting the need for intercontinentally understood concepts and their associated intercontinentally agreed terms. Clin. Biochem. 2009, 42, 246–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hastie, T.; Tibshirani, R.; Friedman, J. The Elements of Statistical Learning; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- James, G.; Witten, D.; Hastie, T.; Tibshirani, R. Linear Model Selection and Regularization. In An Introduction to Statistical Learning: With Applications in R; James, G., Witten, D., Hastie, T., Tibshirani, R., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 225–288. [Google Scholar]

| Ref. | Material | Model | Domain/Dataset | Interpolation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [18] | Methodology | INN | Method theory | Yes |

| [19] | Metals | MLP | S-N datasets/Experiments | Yes |

| [20] | Steel | ANN | Fatigue life/FE-generated | In range 1 |

| [21] | Polymers and AM | ML | Fatigue life/Experiments | No |

| [22] | Metals | ANN | Non-Gaussian loading/Experiments | No |

| [23] | Composites | BNN | Fatigue life/Experiments (UQ) | No |

| This study | C45 steel | ANN | Thermal parameters/Experiments | Yes |

| Staircase Method | PT Approach (TCM) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 50% probability | 1% probability | Approximating curves | Thermal parameters | 1st experimental campaign | 2nd experimental campaign |

[MPa] | [MPa] | σDTCM-1 [MPa] | σDTCM-2 [MPa] | ||

| 211 | 205 | Parabola–power law | ΔT | 208 | 199 |

| A | 199 | 131 | |||

| Linear–linear | ΔT | 195 | 170 | ||

| A | 194 | 148 | |||

| Parameter | Range | Value |

|---|---|---|

| Hidden layers | (16), (32), (64), (32, 16), (64, 32), (128, 64) | (128, 64) |

| Alpha (L2) | 1 × 10−2, 3 × 10−3, 1 × 10−3, 3 × 10−4, 1 × 10−4, 1 × 10−5, 1 × 10−6 | 0.0001 |

| Activation | - | ReLU |

| Solver | - | Adam |

| Learning rate (init) | - | 0.01 |

| Thermal Parameters | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A [°C] | 162,181.46 | 402.71 | 0.99 | 330.48 |

| ΔT [°C] | 108,034.41 | 328.68 | 0.99 | 265.12 |

| Stress Amplitude [MPa] | 1st Campaign | ANN Fit | Residual | Relative Error [%] | 2nd Campaign | ANN Fit | Residual | Relative Error [%] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 100 | 2,846.9 | 2,846.8 | 0.096 | 0.003 | 2,856.8 | 2,849.09 | 7.710 | 0.269 |

| 125 | 4,458 | 4,458.23 | −0.227 | 0.005 | 4,482.8 | 4,489.58 | −6.776 | 0.151 |

| 150 | 6,564 | 6,563.93 | 0.072 | 0.001 | 6,626.8 | 6,626.27 | 0.527 | 0.007 |

| 175 | 8,573.1 | 8,573.15 | −0.053 | 0.000 | 9,361.7 | 9,357.39 | 4.311 | 0.046 |

| 200 | 11,452.9 | 11,452.8 | 0.140 | 0.001 | 12,397.3 | 12,395.7 | 1.570 | 0.012 |

| 210 | 12,712.6 | 13,091.8 | −379.200 | 2.983 | 13,314.9 | 13,560.1 | −245.150 | 1.841 |

| 220 | 15,037 | 15,038.5 | −1.490 | 0.009 | 15,111.4 | 15,157.4 | −45.970 | 0.304 |

| 225 | 16,244.1 | 16,101.2 | 142.930 | 0.879 | 15,987.7 | 16,012.8 | −25.120 | 0.157 |

| 230 | 17,165.9 | 17,163.8 | 2.070 | 0.0120 | 16,990.3 | 16,868.2 | 122.110 | 0.718 |

| 235 | 17,927.9 | 17,928.5 | −0.590 | 0.003 | 17,590.4 | 17,664.6 | −74.240 | 0.422 |

| Stress Amplitude [MPa] | 1st Campaign | ANN Fit | Residual | Relative Error [%] | 2nd Campaign | ANN Fit | Residual | Relative Error [%] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 100 | 2.5 | 2.465 | 0.035 | 1.400 | 2.5 | 2.477 | 0.022 | 0.883 |

| 125 | 4.2 | 4.242 | −0.042 | 1.005 | 4.1 | 4.137 | −0.037 | 0.919 |

| 150 | 6.2 | 6.181 | 0.018 | 0.305 | 6.2 | 6.178 | 0.021 | 0.353 |

| 175 | 8.4 | 8.399 | 0.000 | 0.005 | 8.7 | 8.699 | 0.000 | 0.002 |

| 200 | 11.1 | 11.095 | 0.004 | 0.040 | 11.8 | 11.790 | 0.009 | 0.082 |

| 210 | 12.3 | 12.421 | −0.121 | 0.987 | 12.9 | 13.002 | −0.102 | 0.792 |

| 220 | 14.3 | 14.338 | −0.038 | 0.268 | 14.6 | 14.591 | 0.008 | 0.056 |

| 225 | 15.5 | 15.372 | 0.127 | 0.824 | 15.5 | 15.553 | −0.053 | 0.342 |

| 230 | 16.5 | 16.406 | 0.094 | 0.569 | 16.5 | 16.514 | −0.014 | 0.088 |

| 235 | 17.3 | 17.375 | −0.075 | 0.434 | 17.5 | 17.476 | 0.023 | 0.136 |

| TCM Methods | Experimental Campaign | Case 0 | Case 1 | Case 2 | Case 3 | Case 4 | Case 5 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Approximating Curves | ΔT | A | ΔT | A | ΔT | A | ΔT | A | ΔT | A | ΔT | A | |

| Linear–linear | 1st | 195 | 194 | 197 | 196 | 191 | 191 | 200 | 198 | 209 | 209 | 198 | 197 |

| 2nd | 170 | 148 | 173 | 160 | 172 | 168 | 186 | 211 | 212 | 211 | 170 | 149 | |

| Mean | 183 | 171 | 185 | 178 | 182 | 180 | 193 | 205 | 211 | 210 | 184 | 173 | |

| St. Dev | 18 | 33 | 17 | 25 | 13 | 16 | 10 | 9 | 2 | 1 | 20 | 34 | |

| ∆TCM-SC | 29 | 40 | 26 | 33 | 30 | 32 | 18 | 7 | 1 | 1 | 27 | 38 | |

| Parabola–power law | 1st | 208 | 199 | 208 | 203 | 196 | 195 | 209 | 199 | 210 | 210 | 209 | 204 |

| 2nd | 199 | 131 | 175 | 164 | 214 | 203 | 213 | 174 | 213 | 212 | 213 | 132 | |

| Mean | 204 | 165 | 192 | 184 | 205 | 199 | 211 | 187 | 212 | 211 | 211 | 168 | |

| St. Dev | 6 | 48 | 23 | 28 | 13 | 6 | 3 | 18 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 51 | |

| ∆TCM-SC | 8 | 46 | 20 | 28 | 6 | 12 | 0 | 25 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 43 | |

| Thermal Area (A) | Thermal Increment (ΔT) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Approximating Curves | Case | UR vs. Case 0 | UR vs. Case 0 | ||||||

| Linear–linear | Case 0 | 46 | 32.53 | 23.0 | 0.00% | 25 | 17.68 | 12.5 | 0.00% |

| Case 1 | 36 | 25.46 | 18.0 | 21.74% | 24 | 16.97 | 12.0 | 4.00% | |

| Case 2 | 23 | 16.26 | 11.5 | 50.00% | 19 | 13.44 | 9.5 | 24.00% | |

| Case 3 | 13 | 9.19 | 6.5 | 71.74% | 14 | 9.90 | 7.0 | 44.00% | |

| Case 4 | 2 | 1.41 | 1.0 | 95.65% | 3 | 2.12 | 1.5 | 88.00% | |

| Case 5 | 48 | 33.94 | 24.0 | −4.35% | 28 | 19.80 | 14.0 | −12.00% | |

| Parabola–power law | Case 0 | 68 | 48.08 | 34.0 | 0.00% | 9 | 6.36 | 4.5 | 0.00% |

| Case 1 | 39 | 27.58 | 19.5 | 42.65% | 33 | 23.33 | 16.5 | −266.67% | |

| Case 2 | 8 | 5.66 | 4.0 | 88.24% | 18 | 12.73 | 9.0 | −100.00% | |

| Case 3 | 25 | 17.68 | 12.5 | 63.24% | 4 | 2.83 | 2.0 | 55.56% | |

| Case 4 | 2 | 1.41 | 1.0 | 97.06% | 3 | 2.12 | 1.5 | 66.67% | |

| Case 5 | 72 | 50.91 | 36.0 | −5.88% | 4 | 2.83 | 2.0 | 55.56% | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Corsaro, L.; Abyaneh, M.D.; Javadi, M.S.; Curà, F.; Sesana, R. Thermal Data Optimization Through Uncertainty Reduction in Fatigue Limits Estimation: A TCM–ANN Framework for C45 Steel. Metals 2026, 16, 42. https://doi.org/10.3390/met16010042

Corsaro L, Abyaneh MD, Javadi MS, Curà F, Sesana R. Thermal Data Optimization Through Uncertainty Reduction in Fatigue Limits Estimation: A TCM–ANN Framework for C45 Steel. Metals. 2026; 16(1):42. https://doi.org/10.3390/met16010042

Chicago/Turabian StyleCorsaro, Luca, Mohsen Dehghanpour Abyaneh, Mohammad Sadegh Javadi, Francesca Curà, and Raffaella Sesana. 2026. "Thermal Data Optimization Through Uncertainty Reduction in Fatigue Limits Estimation: A TCM–ANN Framework for C45 Steel" Metals 16, no. 1: 42. https://doi.org/10.3390/met16010042

APA StyleCorsaro, L., Abyaneh, M. D., Javadi, M. S., Curà, F., & Sesana, R. (2026). Thermal Data Optimization Through Uncertainty Reduction in Fatigue Limits Estimation: A TCM–ANN Framework for C45 Steel. Metals, 16(1), 42. https://doi.org/10.3390/met16010042