Deformation Behavior of Sintered Cu-10wt%Mo Composite in the Hot Extrusion Process

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results and Discussion

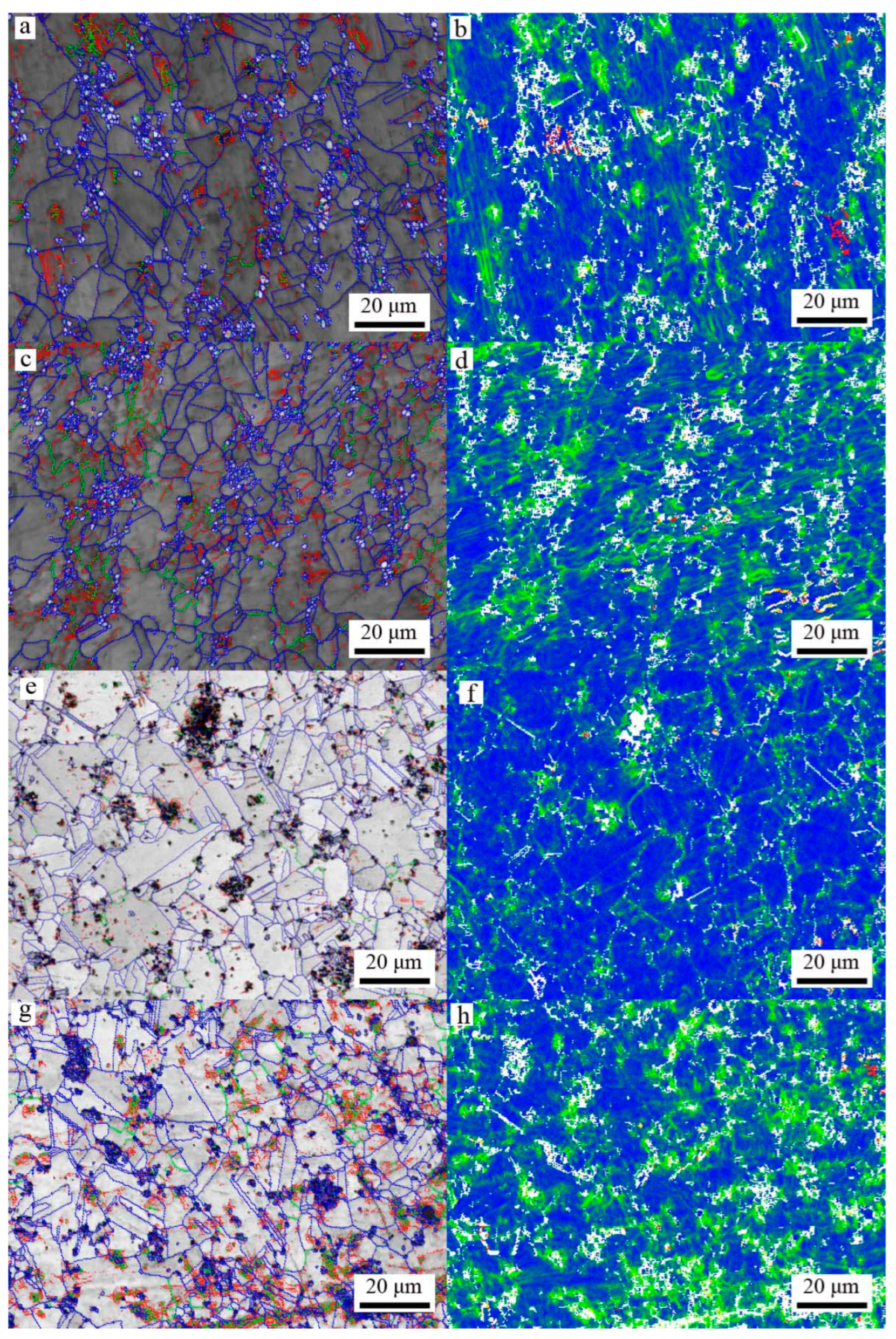

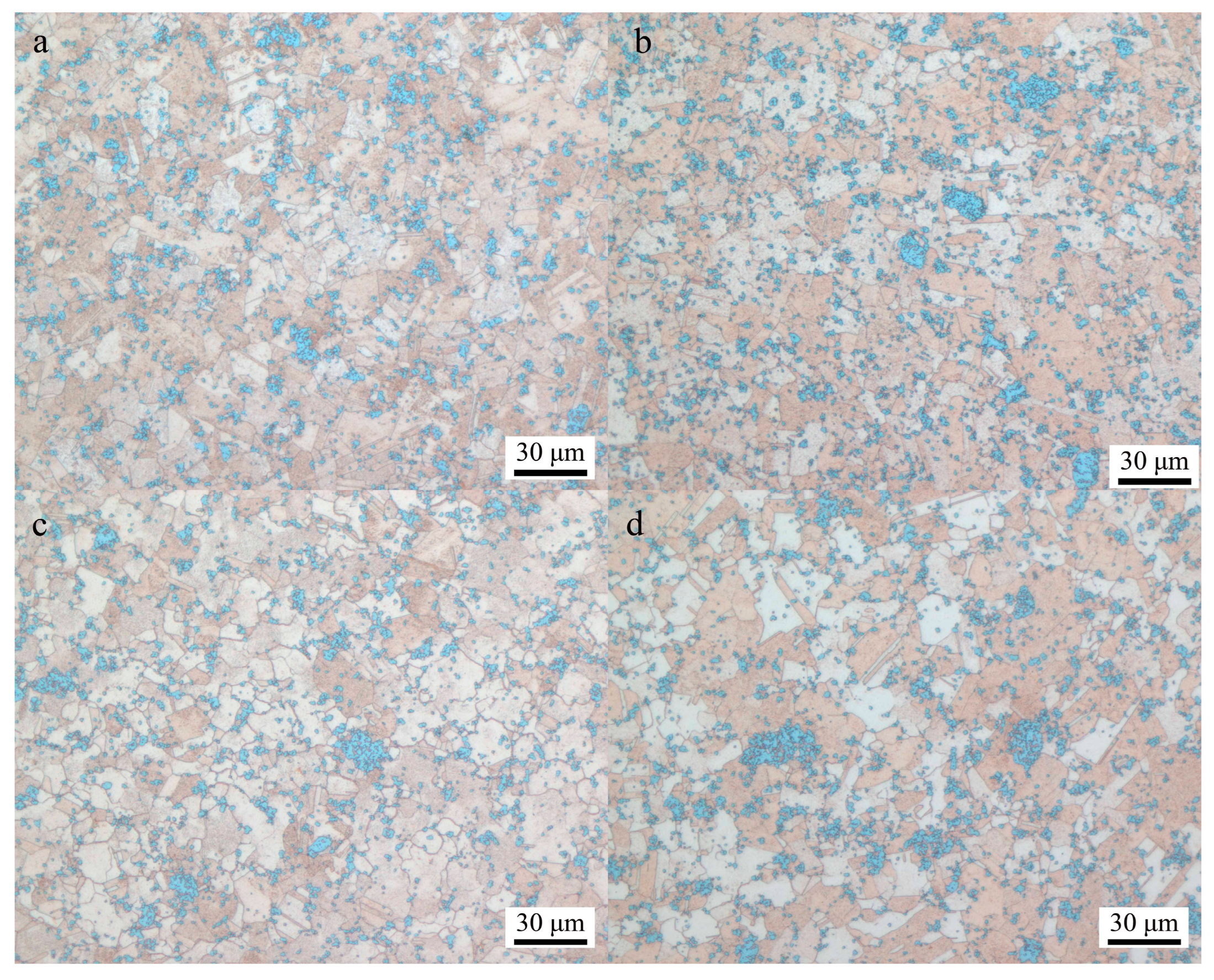

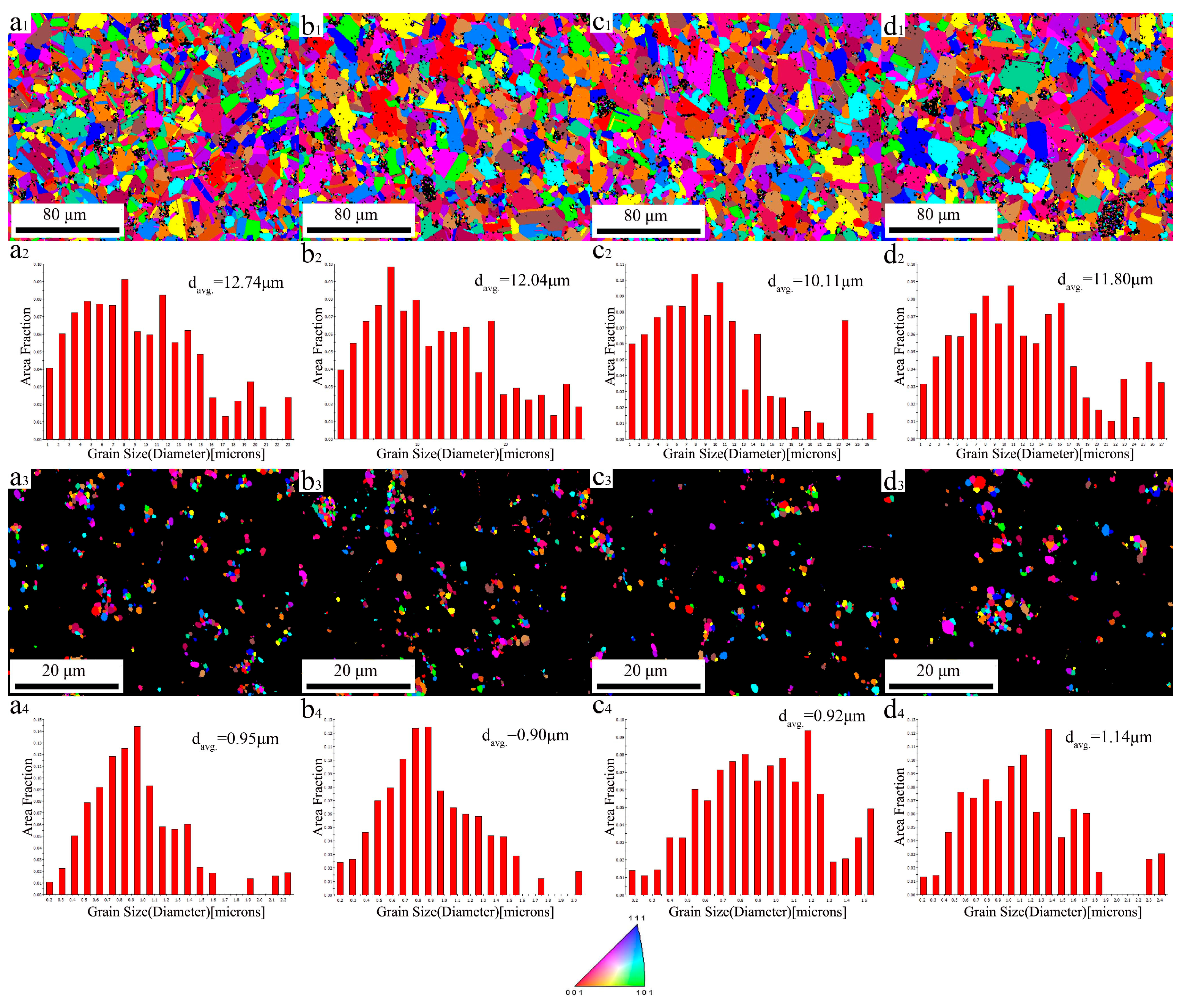

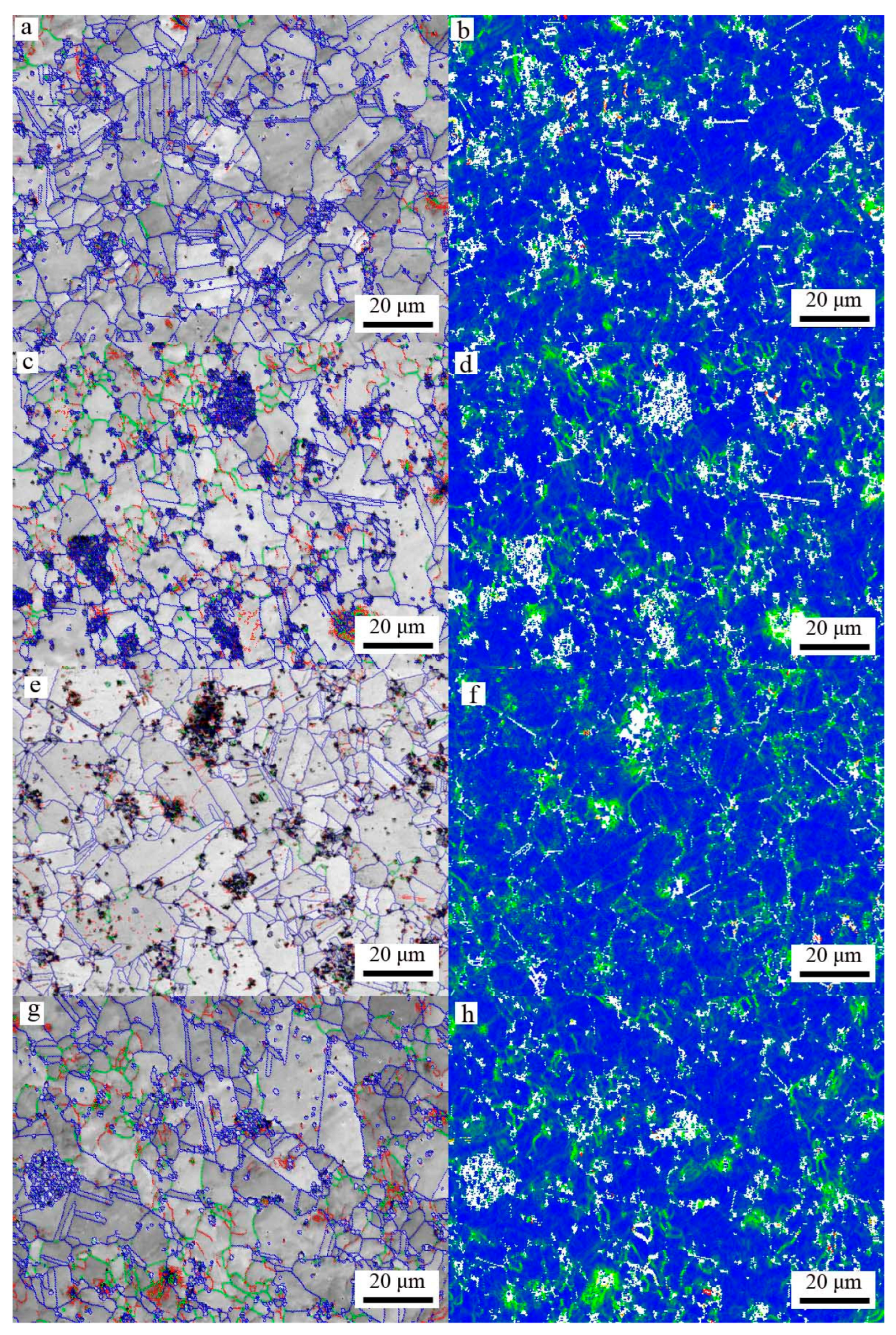

3.1. Microstructure Evolution

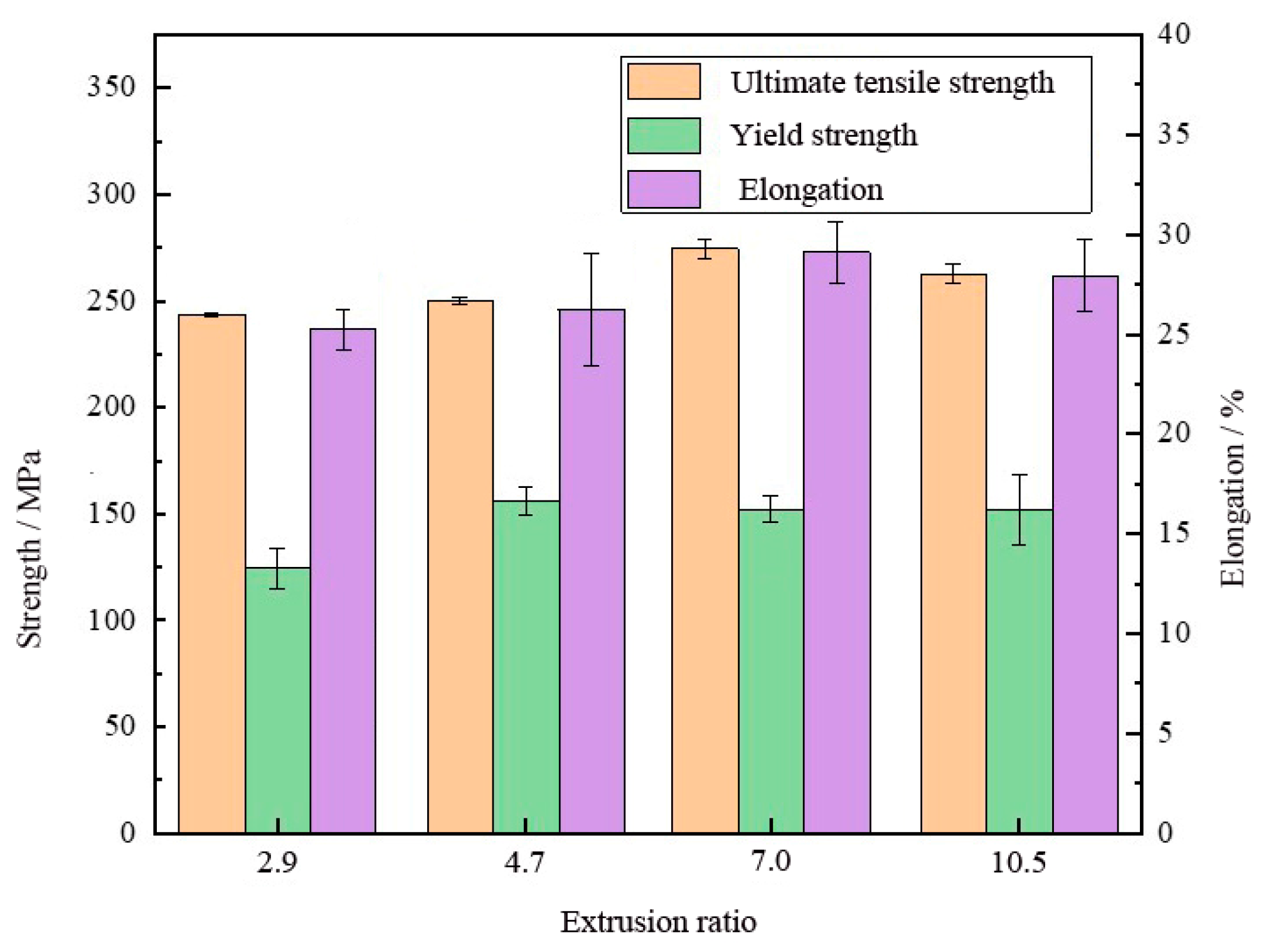

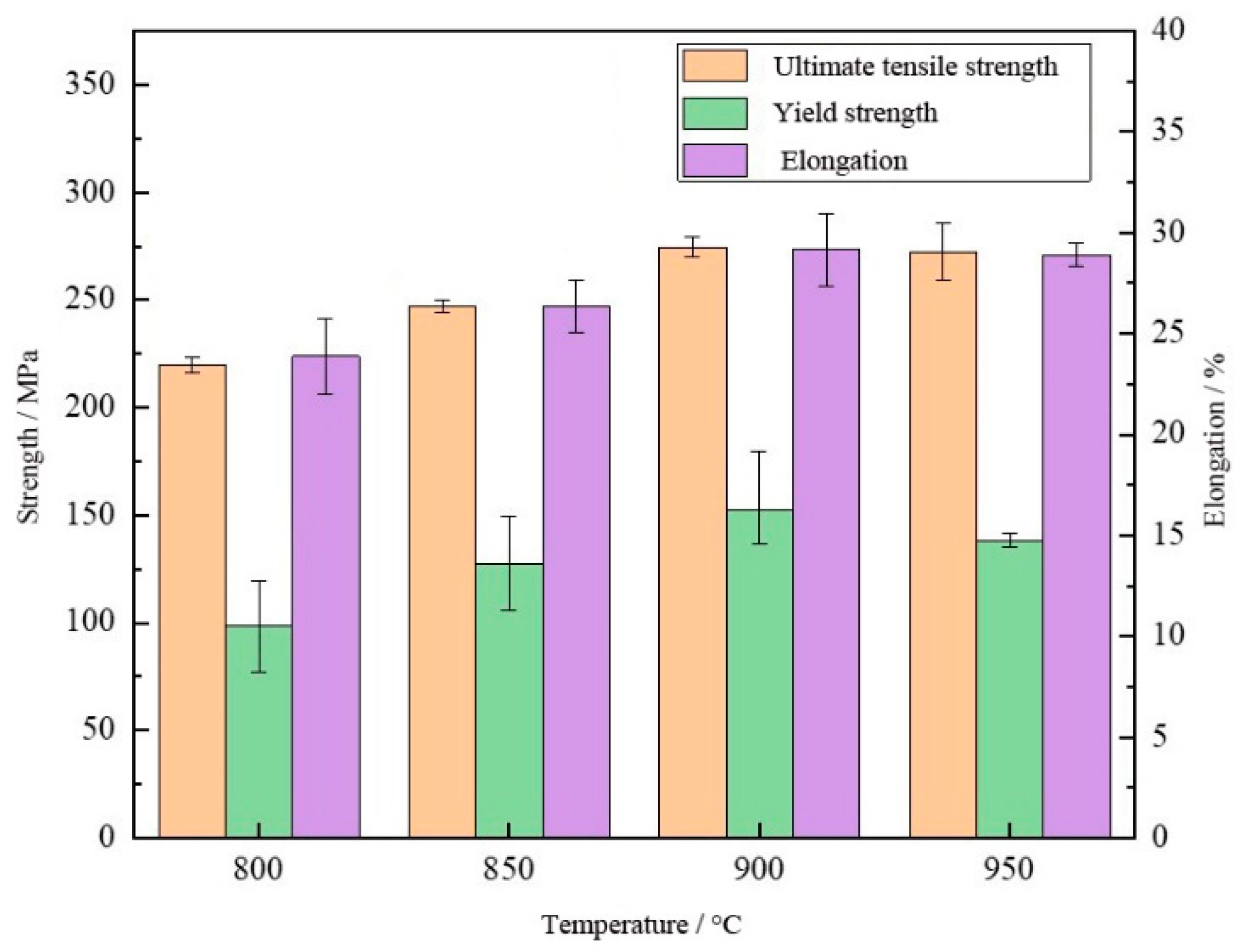

3.2. Tensile Mechanical Properties

3.3. Thermal Conductivity

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| EMAX | Energy-Dispersive X-ray Microanalysis System |

References

- Ji, X.P.; Cao, W.C.; Bu, C.Y.; He, K.; Wu, Y.D.; Zhang, G.H. A new route for preparing Mo-10wt.%Cu composite compacts. Int. J. Refract. Met. Hard Mater. 2019, 81, 196–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Li, Z.D.; Xie, H.F.; Peng, L.J.; Mi, X.J. Microscopic formation mechanism and physical properties of Mo/Cu composites with high densification. Mater. Sci. Forum. 2023, 1094, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Hu, H.; Lai, R.M.; Xie, Q.C.; Zhi, Y. Cyclic warm rolling: A path to superior properties in Mo-Cu composites. Int. J. Refract. Met. Hard Mater. 2025, 126, 106926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.X.; Ren, X.J.; Jin, K.J.; Tan, H.; Zhu, S.Y.; Cheng, J.; Guo, J.; Yang, J. Current-carrying tribological properties and wear mechanisms of Mo-containing Cu alloy coatings produced by laser cladding. Tribol. Int. 2024, 200, 110107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, W.Q.; Wei, L.F.; Li, Y.C.; Zhang, W.; Ma, Z.Q.; Liu, C.X.; Liu, Y.C. Phase interface engineering: A new route towards ultrastrong yet ductile Mo alloy. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2024, 889, 145867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.Z.; Chen, D.D.; Yang, Y.H.; Sun, A.K. Interface of Mo-Cu laminated composites by solid-state bonding. Int. J. Refract. Met. Hard Mater. 2015, 51, 239–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, F.; Zhou, Y.Y.; Yang, W. Temperature dependent tensile and fracture behaviors of Mo-10 wt.% Cu composite. Int. J. Refract. Met. Hard Mater. 2014, 42, 120–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Z.L.; Li, P.P.; Zheng, B.; Xiao, D.D. The structure and properties of electroless Ni-Mo-Cr-P coatings on copper alloy. Mater. Corros. 2013, 64, 341–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paola, A.B.; Benjamin, S.; Rodrigo, H.P. Liquid phase sintering of mechanically alloyed Mo-Cu powders. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2017, 701, 237–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minasyan, T.; Kirakosyan, H.; Aydinyan, S.; Liu, L.; Kharatyan, S.; Hussainova, I. Mo-Cu pseudoalloys by combustion synthesis and spark plasma sintering. J. Mater. Sci. 2018, 53, 16598–16608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, L.; Tian, N.; Zhang, C.; Guan, J.; Wan, H.; Guan, Q. Surface Alloying on Cu with Mo by High-Current Pulsed Electron Beam Irradiation. Chin. J. Vac. Sci. Technol. 2024, 44, 258–265. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Y.; Wang, S.; Gao, Y.; You, L.; Pang, X.; Lu, H.; Song, C.; Zhang, Y. Improving the mechanical and tribological properties of Cu matrix composites by doping a Mo2BC ceramic. J. Alloys Compd. 2024, 1009, 177003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Yoon, H.W.; Moon, K.I.; Lee, C.S. Mechanical and friction behavior of sputtered Mo-Cu-(N) coatings under various N2 gas flow using a multicomponent single alloy target. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2021, 412, 127060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.Y.; Liu, X.W.; Cao, J.; Feng, X.Y.; Li, S.K.; Liu, J.X. Amorphous interlayer assisted ductility of Mo-Cu alloy. Mater. Des. 2023, 231, 112010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, J.L.; Huang, Y.; Xiao, C.; Liu, Y.C. Building metallurgical bonding interfaces in an immiscible Mo/Cu system by irradiation damage alloying (IDA). J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2018, 34, 689–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.M.; Zhang, M.; Li, G.; Bai, W.W.; Huang, Y.D. Extrusion temperature dependence of microstructure and mechanical behavior for a lightweight Mg-7Li-3Al-0.3Si-0.3Mn dual-phase alloy. J. Alloys Compd. 2025, 1046, 184946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, X.B.; Jia, C.Y.; Yang, Q.; Dai, C.; Feng, W.Z.; Wu, W.Q. Multi-objective optimization design and verification of extrusion die structure for TC4 titanium alloy Y-section profile. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2025, 39, 1585–1598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagliuk, G.A.; Kyryliuk, S.F. Evolution of the stress-strain state of porous workpieces in hot extrusion forging to produce axisymmetric parts with an axial hole. Powder Metall. Met. Ceram. 2023, 61, 504–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB/T 228.1-2021; Metallic Materials-Tensile Testing—Part 1: Method of Test at Room Temperature. Standards Press of China: Beijing, China, 2021.

- GB/T 22588-2008; Determination of Thermal Diffusivity or Thermal Conductivity by the Flash Method. Standards Press of China: Beijing, China, 2008.

- Yako, S.; Park, M.; Tsuji, N. Quantitative evaluation of local strain distribution induced by deformation twins and triggering effect of deformation twinning on neighboring grains in polycrystalline AZ31 magnesium alloys. Scr. Mater. 2025, 255, 116388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.K.; Zhang, J.Y.; Liu, G.; Sun, J. Sequentially-activated multiple deformation mechanisms enable a hierarchically duplex titanium alloy with high strength-ductility synergy. Acta Mater. 2025, 301, 121546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field, D.P.; Trivedi, P.B.; Wright, S.I.; Kumar, M. Analysis of local orientation gradients in deformed single crystals. Ultramicroscopy 2005, 103, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.W.; Yin, D.D.; Wan, Y.F.; Ni, R.; Zhou, H.; Zhang, J.; Wang, Q.D. Slip system activation and plastic strain heterogeneity in compressed Mg-10Gd-3Y-0.5Zr alloy. Trans. Nonferrous Met. Soc. China. 2023, 33, 79–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, H.; Shi, Q.; Dan, C.; You, X.; Zong, S.; Zhong, S.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, H.; Chen, Z. Resolving localized geometrically necessary dislocation densities in Al-Mg polycrystal via in situ EBSD. Acta Mater. 2024, 279, 120290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- German, R.M. A model for the thermal properties of liquid-phase sintered composites. Metall. Mater. Trans. A 1993, 24, 1746–1752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, S.X.; Feng, K.Q.; Zhou, H.L.; Shui, Y. Phase evolution of Mo-W-Cu alloy rapid prepared by spark plasma sintering. J. Alloys Compd. 2019, 775, 784–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azemian, S.; Fanchini, G. Electron-phonon interaction and lattice thermal conductivity from metals to 2D Dirac crystals: A review. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 2025, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, A.; Sheng, Y.F.; Bao, H. Recent advances in thermal transport theory of metals. Acta Phys. Sin. 2024, 73, 037201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lepeshkin, A.R.; Vaganov, P.A. Investigations of thermal conductivity of metals in the field of centrifugal and vibration accelerations. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2016, 774, 012022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Y.L.; Zhang, X.Y.; Wang, A.; Sheng, Y.F.; Xie, H.; Bao, H. Critical factors influencing electron and phonon thermal conductivity in metallic materials using first-principles calculations. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 2024, 37, 055701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herzog, M.; Reppert, A.; Pudell, J.; Henkel, C.; Kronseder, M.; Back, C.H.; Maznev, A.A.; Bargheer, M. Phonon-dominated energy transport in purely metallic heterostructures. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2022, 32, 055701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.; Deskins, W.R.; Braga, M.H.; El-Azab, A. Effect of electron-phonon coupling on thermal transport in metals: A Monte Carlo approach for solving the coupled electron-phonon Boltzmann transport equations. AIP Adv. 2025, 15, 025108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karna, P.; Giri, A. Electron-electron scattering limits thermal conductivity of metals under extremely high electron temperatures. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 2024, 36, 185701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, X.B.; He, Z.H.; Pan, B.C. The thermal conductivity of defected copper at finite temperatures. J. Mater. Sci. 2019, 55, 4453–4463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, G.; Zhang, S.; Chen, K.Y.; Zhang, W.; Li, L.; Zhang, Y.J.; Peng, H.R.; Kan, D.X.; Wang, L.H.; Zhang, H.L.; et al. Achieving excellent thermal transport in diamond/Cu composites by breaking bonding strength-heat transfer trade-off dilemma at the interface. Compos. B Eng. 2025, 289, 111925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Extrusion ratio | 2.9 | 4.7 | 7.0 | 10.5 |

| Thermal conductivity value (W/(m·K)) | 349 | 354 | 369 | 358 |

| Extrusion temperature | 800 °C | 850 °C | 900 °C | 950 °C |

| Thermal conductivity value (W/(m·K)) | 346 | 353 | 369 | 368 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Li, Q.; Li, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Hui, S. Deformation Behavior of Sintered Cu-10wt%Mo Composite in the Hot Extrusion Process. Metals 2026, 16, 44. https://doi.org/10.3390/met16010044

Li Q, Li Z, Zhang Z, Hui S. Deformation Behavior of Sintered Cu-10wt%Mo Composite in the Hot Extrusion Process. Metals. 2026; 16(1):44. https://doi.org/10.3390/met16010044

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Qing, Zengde Li, Zhanning Zhang, and Songxiao Hui. 2026. "Deformation Behavior of Sintered Cu-10wt%Mo Composite in the Hot Extrusion Process" Metals 16, no. 1: 44. https://doi.org/10.3390/met16010044

APA StyleLi, Q., Li, Z., Zhang, Z., & Hui, S. (2026). Deformation Behavior of Sintered Cu-10wt%Mo Composite in the Hot Extrusion Process. Metals, 16(1), 44. https://doi.org/10.3390/met16010044