Abstract

Conventional anticorrosive coatings suffer from limitations of low solid content and rigorous surface pretreatment, posing environmental and cost challenges in field applications. In this study, a novel high-solid-content (>95%) epoxy-polysiloxane (Ep-PSA) ceramic metal coating was prepared that enables low-surface-treatment application. The originality lies in the synergistic combination of nano-sized ceramic powders, high-strength metallic powders, polysiloxane resin (PSA), and solvent-free epoxy resin (Ep), which polymerize through an organic–inorganic interpenetrating network to form a dense shielding layer. The as-prepared Ep-PSA coating system chemically bonds with indigenous metal substrate via Zn3(PO4)2 and resin functionalities during curing, forming a conversion layer that reduces surface preparation requirements. Differentiating from existing high-solid coatings, this approach achieves superior long-term barrier properties, evidenced by |Z|0.01Hz value of 9.64 × 108 Ω·cm2, after 6000 h salt spray exposure—four orders of magnitude higher than commercial 60% epoxy zinc-rich coatings (2.26 × 104 Ω·cm2, 3000 h salt spray exposure). The coating exhibits excellent adhesion (14.28 MPa) to standard sandblasted steel plates. This environmentally friendly, durable, and easily applicable composite coating demonstrates significant field application value for large-scale energy infrastructure.

1. Introduction

Due to its exceptional mechanical properties, metallic substrates have emerged as indispensable and pivotal components in various industries [1]. Metallic materials frequently encounter diverse and intricate environmental conditions, wherein they undergo chemical interactions with ambient corrosive media [2]. Corrosion issues have become one of the major challenges in industrial development and marine economic development [3]. Every year, 10% to 20% of metals are consumed due to corrosion, and one ton of metal is corroded every 90 s. The economic loss caused by corrosion in China amounts to CNY 2.1 trillion annually [4]. Therefore, the development of efficient metal anti-corrosion technologies holds significant economic and strategic importance [5]. To reduce the loss caused by corrosion, many methods have been developed, such as material selection [6], surface modification [7,8,9], sacrificial anode protection [10,11], cathodic protection [12,13], environmental treatment [14,15], photoelectrochemical approach [16], and so on. Among them, surface coating protection is the most effective and practical measure [17]. Attributed to its cost-effectiveness, simple and efficient construction process, and ability to provide long-lasting corrosion protection.

Conventional coating materials include epoxy resin coating [18,19], polyurethane resin coating [20,21], fluorocarbon resin coating [22,23], and so on, which can coat the target metal and inhibit corrosion through shielding effects. However, most existing anti-corrosion coatings are solvent-based, with an organic solvent content as high as 50%. During application, a large amount of toxic and harmful organic solvents are emitted, causing significant harm to both human health and the environment [24]. Moreover, the release of organic solvents creates numerous pores in the coating, providing pathways for corrosive media such as oxygen, water, chloride ions, and hydrogen ions [25]. This reduces the barrier performance of the coating. In addition, the traditional anti-corrosion coatings have strict requirements for rust removal of metal substrates. The metal substrate must be ground until no loosely attached substances such as scale, rust, or old paint coatings remain on the surface, and the exposed part of the substrate should exhibit a metallic luster. However, this requirement is difficult to meet during the actual anti-corrosion maintenance construction, especially for high-altitude operations [26]. Consequently, many high-performance new anti-corrosion materials fail to deliver their expected anti-corrosion effect due to inadequate base material treatment that does not comply with specifications. Therefore, the design and fabrication of high-solid-content (HSC) and low-surface-treatment (LST) anti-corrosion coatings have become a research focus in the field.

The term “High-solid-content” refers to the coating that has a solid content exceeding 70% (per ASTM D2697) [27]. The concept of “low surface treatment” refers to a substrate preparation strategy that eliminates the need for rigorous rust removal (St2 grade as specified in ISO 8501-1) [28] and only requires minimal treatment to ensure the substrate surface is free of loose contaminants that may hinder coating adhesion. In recent years, some efforts have been devoted to developing high-solid-content and low-surface-treatment anti-corrosion coatings. For HSC coatings, the core challenge lies in reducing resin viscosity while maintaining sufficient cross-linking density to ensure coating integrity. Existing strategies primarily involve adjusting resin molecular weight or introducing reactive diluents [29]. However, reactive diluents often compromise coating mechanical properties, and simply reducing molecular weight tends to decrease cross-linking density, leading to reduced barrier performance [25]. For LST coatings, two key requirements must be satisfied: excellent penetration to infiltrate loose rust layers and form continuous seals, and sufficient reactivity to passivate harmful iron compounds in rust into stable fillers [30]. Epoxy resin-based coatings have good mechanical properties, chemical reactivity, adjustable molecular weight, and strong adhesion to various substrates, and are ideal candidates for high-solid-content and low-surface-treatment anti-corrosion coating system. But epoxy resins suffer from high rigidity [31,32], which easily causes film cracking during formation and service, resulting in anti-corrosion failure.

To address the rigidity issue of epoxy resins, researchers have attempted to blend them with flexible polymers. Polysiloxane (PSA) resin, with its inorganic Si-O-Si backbone and organic functional groups, exhibits excellent flexibility and chemical resistance [33]. Wu et al. [34] demonstrated that PSA could effectively improve the flexibility of polystyrene–acrylate polymers, but their work focused on conventional solvent-based coatings and did not involve LST or HSC design. In terms of enhancing cross-linking density of HSC coatings, Tian et al. [25] reported that adding nano-SiO2 and TiO2 could form a highly cross-linked long-chain structure, improving barrier performance; moreover, their coating system can be applied in conditions with water, rust, and oil. However, their coating system has poor corrosion resistance. After 28 days of salt spray treatment, the impedance value at the lowest frequency was only at the level of 103 Ω·cm2.

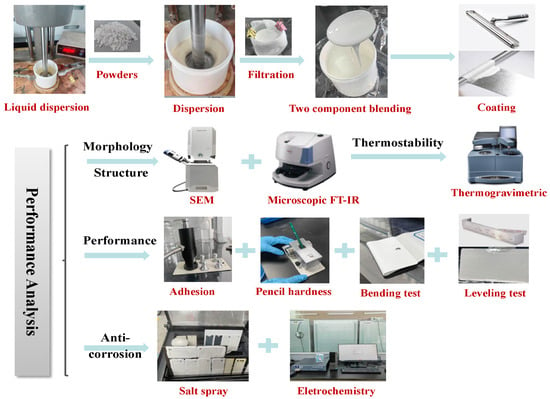

To address these gaps, this study constructs a high-solid-content and low-surface-treatment anti-corrosion coating system using epoxy resin as the main molecular network and PSA as the guest molecule, with cross-linking density regulated by ceramic nanoparticles and high-strength metallic particles. Compared with reported systems, this work offers three distinct advantages: first, the synergistic integration of epoxy-polysiloxane organic–inorganic hybridization with ceramic/metallic particles not only overcomes epoxy rigidity but also enhances cross-linking density and mechanical robustness, surpassing nano-oxide-only reinforced systems; second, the coating exhibits superior adaptability to low-surface-treatment conditions, capable of being applied to rusty substrates, which compensates for the sensitivity of traditional low-surface-treatment coatings to construction environment; third, it balances high solid content with excellent resistance to extreme media (concentrated acids, alkalis, and salts), addressing the limitation of conventional high-solid-content coatings in harsh chemical environments. As illustrated in Scheme 1, the performance of the coating on rusty surfaces was studied by characterizing the surface morphology of the coating on corroded carbon steel. The solid content, hardness, bending resistance, impact resistance, and leveling performance were tested to evaluate mechanical properties. The adhesion of the coating on different substrates was investigated to assess its applicability across various materials. Acid, alkali, and salt resistance were tested by immersing coated carbon steel specimens in 10% NaOH, 10% HCl, and 5% NaCl solutions, respectively, to demonstrate adaptability in different scenarios. Corrosion resistance was evaluated via salt spray tests and electrochemical measurements.

Scheme 1.

The coating preparation and performance analysis workflow diagram of this work.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

828 Ep resin, PSA resin, and defoaming agent were obtained from Evonik Industries AG (Hanau, Germany). The nano ceramic powders of sericite, silica fume (1250 mesh), and SiO2 (800 mesh) were obtained from Haiyang Powder Technology Co., Ltd. (Shenzhen, China). The inert diluent NX-2020 and phenolic amide (LITE 3070) were obtained from Cardale Chemical Co., Ltd. (Zhuhai, China). The high-strength metal powders of TiO2 (400 mesh), BaSO4 (1250 mesh), and Zn3(PO4)2 were obtained from Sichuan Longmang Group Co., Ltd. (Chengdu, China) and Guangxi Lianzhuang Technology Co., Ltd. (Laibin, China), respectively. The polyamide wax anti-sediment agent, flatting agent, and wetting dispersant were obtained from Arkema Chemical Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). The coated test-grade tinplate plates (C: 0.15%, Si: 0.03%, Mn: 1.00%, P: 0.20%, S: 0.03, Al: 0.20%, Cu: 0.20%, Ni: 0.25%, Cr: 0.10%, Mo: 0.05%, Fe: excess. Tin plating weight 22 g/m2) with size of 120 mm × 50 mm × 0.3 mm, Q235B carbon steel plates (C: 0.20%, Si: 0.35%, Mn: 0.55%, S: 0.04%, S: 0.04%, Fe: excess) with size of 120 mm × 70 mm × 1 mm, and sandblasted steel plates (C: 0.20%, Si: 0.35%, Mn: 0.55%, S: 0.04%, S: 0.04%, Fe: excess) with sizes of 120 mm × 70 mm × 1 mm were obtained from Honghong Coating Test Board Manufacturer (Guangzhou, China). The 5083 aluminum alloy sheets (Si: 0.30%, Fe: 0.25%, Cu: 0.08%, Mg: 4.6%, Cr: 0.12%, Zn: 0.18%, Ti: 0.07%, Al: excess) with size of 70 mm × 50 mm × 2 mm were obtained from Okonink (Qinhuangdao) Aluminum Industry Co., Ltd. (Qinhuangdao, China). The 316L stainless steel sheets (C: 0.02%, Cr: 18%, Ni: 12%, Mo: 2.5%, Si: 1.0%, Mn: 1.5%, P: 0.04%, S: 0.03%, N: 0.08%, Fe: excess) with size of 70 mm × 50 mm × 3 mm were obtained from Xiangwei Standard Corrosion Test Specimen Manufacturer (Yangzhou, China). Analytical-grade NaCl, H2SO4, and NaOH were obtained from Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd. (Ningbo, China).

2.2. Preparation of the Composite Coating

Firstly, 90 g Ep resin, 10.00 g inert diluent, 2.00 g polyamide wax, 1.60 g wetting dispersant, 4.00 g Ep resin toughening agent, and 1.20 g defoaming agent were mixed and dispersed thoroughly at 1000–1500 r/min for 5–10 min in a multi-paint shaker. Then, the high-strength metal powders and nano ceramic powders of TiO2 (24.00 g), BaSO4 (16.00 g), sericite (10.00 g), silica fume (5.60 g), SiO2 (2.00 g), and Zn3(PO4)2 (5.00 g) were added carefully at a rotational speed of 500–800 r/min. After that, the resulting mixture was stirred at 1200 r/min for 15 min, after which the 60.00 g of PSA resin and leveling agent were added, and then the mixture was dispersed for 5 min at a rotational speed of 500 r/min and passed through a 200-mesh filter cloth to remove large particles. The main component of the high-solid-content and low-surface-treatment polysiloxane coating was obtained, named component A. For application, components A and B (phenolic amide curing agent) were mixed in a certain proportion. The coatings in this work were applied to grade tinplate (Tin), rusty carbon steel (RCS), aluminum alloy (AA), and stainless steel (SS), as well as standard sandblasted steel plates (SSS), and its results were compared with those of the commercial 60% epoxy zinc-rich (Ep-Zn) coating. A dedicated coating applicator was applied to control the coatings (as-prepared coating and the commercial 60% Ep-Zn) thickness to 100 μm.

2.3. Characterization of the Surface Morphologies and Thermostability

The surface morphologies and elemental composition of the coatings on grade Tin, RCS, and SS were observed using a field emission scanning electron microscopy (Apreo 2C, Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA USA) equipped with an ULTIM Max65 energy-dispersive X-ray spectrometer (EDS) detector. The working distances (WDs) of the FESEM images were 8.2 mm. The thermal stability of the as-prepared coating was evaluated by thermogravimetric analysis (TGA, HITACHI STA 200, TGA Instrument, New Castle, DE, USA) under the protection of a nitrogen atmosphere. The measurement temperature range was from room temperature to 1200 °C, and the heating rate was 10 °C/min. The microscopic infrared spectroscopy (Micro-IR) of the as-prepared Ep-PSA coating was carried out with a Nicolet iN10 Micro-IR spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA).

2.4. Coating Performance Testing

The solid content of the as-prepared coating was tested according to Chinese national standard GB/T 1725-2007 [35]. The hardness of the coating film was tested according to GB/T 6739-2022 [36] of China using the QHQ-A film hardness tester (Jingkelian Material Testing Machine Co., Ltd., Tianjin, China), expressed as the hardness of the hardest pencil that does not produce defects in the coating film. Flexibility of the coating film was examined according to GB/T 1731-2020 and characterized as the minimum diameter of the shaft rod that does not damage the coating film after bending [37]. The leveling property of coatings was tested according to ASTM D2801-1994 [38] using a leveling test scraper with several different depth gaps to scrape the coating into several pairs of parallel strips of different thicknesses. The number of strips that completely and partially flow together is observed and compared with the standard pattern. It is represented by 0 to 10 levels. Level 10 indicates complete leveling, while level 0 indicates the poorest leveling property. The adhesion of the coating was tested using the pull-off method according to GB/T 5210-2006 [39]. The test column is directly bonded to the coating surface using adhesive. The bonded test combination is pulled apart using a tensile testing machine. The force required to separate the coating and the substrate is measured. The failure strength is determined using the force divided by the area of the test column and is expressed in MPa as the test result. According to GB/T 30648.1-2014, the media resistance performance of the coating is tested by immersing the coated sample completely or partially in 10% H2SO4, 10% NaOH, and 5% NaCl solutions under controlled temperature and time conditions and observing the physical and chemical changes of the coating [40]. All the performance tests were conducted in three parallel trials.

2.5. Salt Spray Test

Neutral salt spray test was carried out according to GB/T 1771-2007 to evaluate the corrosion resistance of the as-prepared coatings [41]. First, the coating was applied onto different types of metal plates and allowed to cure for 48 h. Then, the samples were fixed on the test chamber’s sample rack. Next, a 5% NaCl solution was atomized and sprayed into the chamber, maintaining the temperature at 35 °C ± 2 °C. The solution was continuously sprayed, and the samples were regularly inspected to record any changes in appearance and the degree of corrosion. Meanwhile, scratching treatment was applied to the coating on different metal substrates, and a 168 h salt spray test was conducted to examine the spread of the rust layer after the coating was damaged.

2.6. Electrochemical Test

The corrosion resistance performance of the coating composites was also evaluated using electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) by applying a low-amplitude AC potential wave on an electrochemical workstation (VersaSTAT 4A, Princeton Applied Research (Ametek), Princeton, NJ, USA). EIS evaluation was conducted in a classic three-electrode cell consisting of a platinum rod as the counter electrode, a saturated calomel electrode as the reference electrode, and a coated steel substrate (1 cm × 1 cm) as the working electrode. The coatings were kept in 3.5 wt% NaCl solution for 30 min to acquire a stable open-circuit potential. AC impedance measurements were conducted at the OCP with a frequency range of 10−2 Hz to 105 Hz and an amplitude voltage of 10 mV.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Morphology and EDS Analysis of the Coating

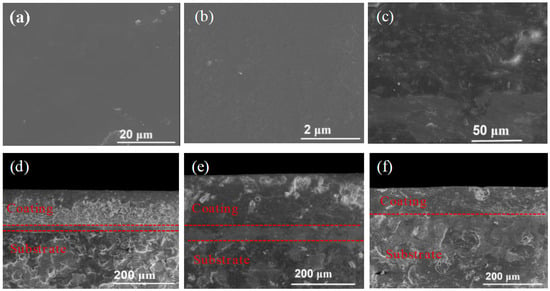

The surface and cross-sectional morphology, as well as EDS element mapping of the composite coatings on Tin, RCS, and SS, were characterized. As shown in Figure 1a,b, the surface profiles of the cured composite coatings all exhibit smooth and clear features, without any obvious defects. They can effectively prevent external corrosive media from entering the interior of the coatings, thereby providing effective anti-corrosion protection for the metal substrate. Since no solvents were used in the coating preparation process, no holes caused by solvent evaporation were observed on the surface of the coating. A small amount of particles and sheet-like substances can be found on the surface of the coating, which can be attributed to the metallic and inorganic particle fillers present in the coating. No cracks were observed near these particle and sheet-like fillers, indicating that the fillers have achieved good integration with the resin system. This is attributed to the organic–inorganic property and flexibility of the PSA resin. As can be seen from the cross-sectional image of the EP-PSA composite coating (Figure 1c), the structure of the coating is very dense, which provides effective barrier capability for preventing the invasion of corrosive media. Many filler particles can be observed from the cross-sectional image of the coating. These particles are evenly dispersed in the coating structure and form a “labyrinth effect.” When the coating is damaged, it can effectively delay the arrival of corrosive media at the metal substrate, further enhancing the protective performance of the coating.

Figure 1.

(a,b) Surface morphology of the composite coatings; (c) cross-sectional morphology of the composite coatings; (d–f) the cross-sectional morphology of the coating on Tin, RCS, and SS substrates.

The cross-sectional images of the EP-PSA composite coating on Tin, RCS, and SS substrates are illustrated in Figure 1d–f. A three-layer structure can be seen in Figure 1d, corresponding to the coating layer, the tin coating (which is part of the tin plate), and the iron layer, respectively. A three-layer structure can also be seen in Figure 1e, corresponding to the coating layer, the rusty layer, and the carbon steel layer, respectively. An obvious two-layer structure was observed in Figure 1f, corresponding to the coating layer and the stainless steel substrate. The coating exhibited excellent adhesion to all substrates (Tin, RCS, and SS), without any gaps or holes being found, suggesting that the coating can be applied to protect these metal substrates without any complex surface treatment process.

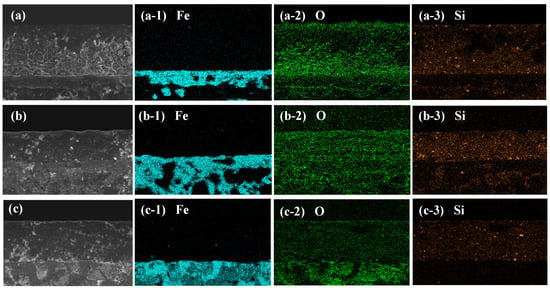

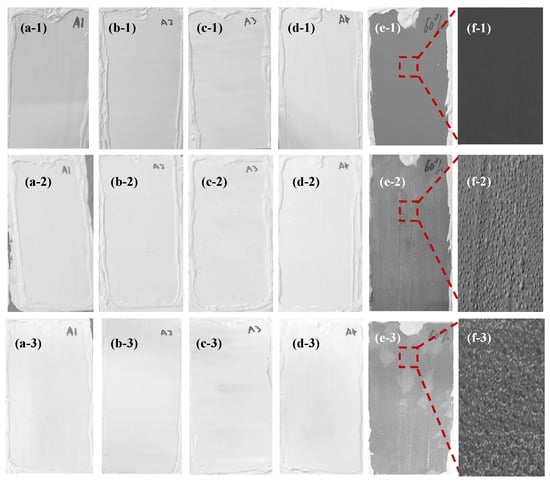

The high-resolution EDS element mapping of the coating applied to the Tin, RCS, and SS substrates is shown in Figure 2. The element mapping of Fe in Figure 2(a-1–c-1) shows that Fe elements from the substrates are basically not distributed in the coating, indicating that the coating has excellent tightness, the metal substrate is not exposed, and the rust layer does not spread. The element mapping of O in Figure 2(a-2–c-2) and element mapping of Si in Figure 2(a-3–c-3) show that these elements are uniformly distributed on the surface of the coating, and the coating has good adhesion to the substrate without any gaps. In particular, as can be seen in the element mapping of Fe in Figure 2(b-1), the rust layer of carbon steel exhibits a loose and porous structure, the O element is evenly distributed throughout the coating layer and the substrate layer, with no obvious boundary (Figure 2(b-2)), and a significant amount of Si element can be seen in the rusty layer. These results show that the coating has penetrated into the rust layer, sealing it and preventing its further spread, which provides direct evidence for the application of the coating on rusty surfaces.

Figure 2.

The cross-sectional morphology of the coating on (a) Tin, (b) RCS, and (c) SS substrates, and the comprehensive element mapping of (a-1–c-1) Fe, (a-2–c-2) O, and (a-3–c-3) Si elements, respectively.

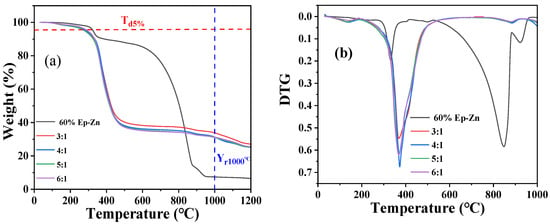

3.2. Thermal Performance Analysis of the Coating Composite

Thermogravimetric analysis (TG) is an effective method to characterize the dynamic thermomechanical properties of a coating [1,42]. The TG (Figure 3a) and DTG (Figure 3b) variation curves of the as-prepared Ep-PSA coatings with component ratios of A:B from 3:1 to 6:1 were recorded under N2 flow to evaluate the thermal stability and the variation in the crystalline phase composition. Meanwhile, the TG and DTG variation curves of the commercially available 60% epoxy zinc-rich coating (60% EP-Zn) were recorded for comparison. The 60% EP-Zn coating exhibits two main mass loss stages, 0~300 °C and 300~800 °C, corresponding to the decomposition of epoxy resin and zinc powders, respectively. Surprisingly, in the temperature range of 0~300 °C, the mass loss is less than 10%. This means that most of the epoxy resin has not decomposed, which may be due to the high zinc content (60%), in which case most of the epoxy resin is encapsulated within the zinc powder. As the temperature increases from 300 °C to 800 °C, more than 93% of the mass loss occurs. The TG and DTG curves of epoxy-polysiloxane coatings with component ratios of A:B from 3:1 to 6:1 can be divided into one main mass loss stage: 0~480 °C. In this stage, more than 60% of the mass loss occurs, which may be due to the decomposition of the resins, curing agent, and auxiliary materials. A residual mass of 30%~40% remains, which may be attributed to the high temperature tolerance character of nano ceramic particles and high-strength metal powders (TiO2 and BaSO4).

Figure 3.

(a) TG and (b) DTG curves of Ep-PSA coatings with component ratios of A:B from 3:1 to 6:1 and the commercially available 60% Ep-Zn.

The temperature at which the mass loss is 5% (Td5%) is one of the key parameters for measuring the thermal stability of the coating [1,43]. Td5% for the 60% EP-Zn coating is 325 °C, while those for Ep-PSA coatings with component ratios of A:B from 3:1 to 6:1 are 277 °C~295 °C. The Td5% temperatures for Ep-PSA coatings are much lower than that of the 60% EP-Zn coating, which may be due to the fact that the addition of PSA resin increases the length of the flexible siloxane segment, and the rigid segment structure loses its dominant position in thermodynamic stability. It is worth mentioning that there are two resins (epoxy and polysiloxane) in the Ep-PSA coatings, while only one mass loss stage can be seen, indicating that the PSA resin and the Ep resin have formed an integrated entity through the interpenetration of their networks. The residual yield at the temperature of 1000 °C (Yr1000°C) of Ep-PSA coatings is higher than that of the 60% EP-Zn coating, which possibly results from the higher decomposition temperature of nano ceramic particles and high-strength metal powders (TiO2 and BaSO4) compared with Zn powder.

3.3. Composite Coating Performance

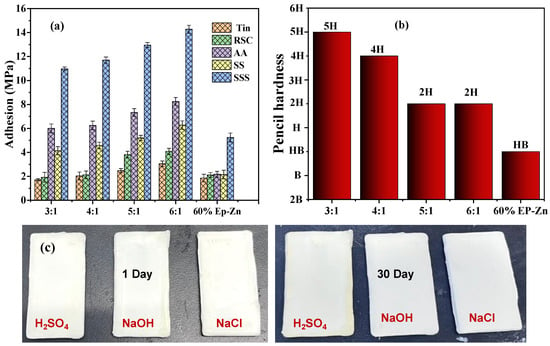

The adhesion strength of the coating to the metal substrates has a very important influence on its anti-corrosion protection. Therefore, the adhesion strength of Ep-PSA coatings with component ratios of A:B from 3:1 to 6:1 and 60% Ep-Zn coating on metal substrates of Tin, RCS, SS, and AA was measured using the pull-off method. As it can be seen from Figure 4, when the proportion of curing agent increases from 6:1 to 3:1, the adhesion gradually decreases. This might be because the high concentration of the curing agent leads to high cross-linking density of the resin, restricting the movement of molecular chains. When subjected to external forces, micro-cracks are prone to form, and stress concentration leads to a decrease in adhesion. At the same time, excessive curing agent will consume the active groups (such as hydroxyl groups) on the resin, reducing the polar points that can form hydrogen bonds or chemical bonds with the substrate and weakening the bonding force between the coating and the substrate. The adhesion strength of Ep-PSA coatings with component ratios of A:B from 4:1 to 6:1 on SSS plates is 10.97~14.28 MPa, while that for the 60% Ep-Zn coating is 7.24 MPa. The adhesion strength of Ep-PSA coatings is much higher than that of 60% Ep-Zn coatings. The corresponding adhesion strengths of the as-prepared coatings on Tin, RCS, AA, and SS are in the ranges of 1.72~3.05 MPa, 1.92~4.09 MPa, 6.00~8.25 MPa, and 4.14~6.28 MPa, respectively. These results indicate that the as-prepared Ep-PSA coating exhibits good adhesion ability on the above metal substrates with low surface treatment.

Figure 4.

(a) Adhesion strength for the Ep-PSA coatings with the A:B component ratio from 3:1 to 6:1, and 60% EP-Zn coating on different types of metal substrates; (b) pencil hardness for the Ep-PSA coatings with the A:B component ratio from 3:1 to 6:1, and 60% EP-Zn coating; (c) images of carbon steel sheets coated with the as-prepared coating after being immersed in different solutions for one month (A:B = 4:1).

Through the hardness test, it can be found that the hardness of epoxy-polysiloxane coatings with component ratios of A:B from 3:1 to 6:1 is 5H–2H, and the hardness shows a decreasing trend (Figure 4b). The hardness of the 60% EP-Zn coating is HB. The hardness of the as prepared EP-PSA coating is higher than that of 60% EP-Zn coating, which can be attributed to its high-strength nano-ceramic particles and metal powder fillers. The acid, alkali, and salt resistance properties of the as-prepared coating were tested by immersing carbon steel sheets coated with the as-prepared coating in 10% H2SO4 and NaOH solutions, as well as 5% NaCl solution for one month. Components A and B were mixed in a ratio of 3:1 and then applied onto the carbon steel sheet. After 48 h of curing, the test pieces were immersed to evaluate their chemical resistance. The experimental results (Figure 4c) show that after being immersed in different solutions for one month, no obvious defects such as whitening or holes occurred on the coating surface, and it still maintained a high glossiness. This indicates that the as-prepared coating has excellent resistance to strong acids, strong alkalis, and high-salt environments and has potential application in harsh industrial and marine environments.

Moreover, the properties of solid content, surface drying time, full drying time, leveling performance, impact resistance, and the bending performance for the EP-PSA coating were tested, and results are displayed in Table 1. As shown in Table 1, when the component ratio of A:B is between 3:1 and 6:1, the solid content is all above 95%, and the leveling performance of the coating is all at level 10. All samples can pass the impact resistance test of 50 kgf·cm. This indicates that under different ratios, the as-prepared anti-corrosion coating has high solid content, good leveling performance, and impact resistance. As the content of the curing agent decreases from 3:1 to 6:1, the surface drying time increases from 2 h to 4 h; the full drying time increases from 24 h to 48 h; and the bending performance (flexibility) improves from the bending degree of a 3 mm diameter cylindrical shaft to that of a 2 mm diameter cylindrical shaft. During application, the ratio of components A and B can be adjusted according to the actual application scenario.

Table 1.

Coating properties with different ratios of components A and B.

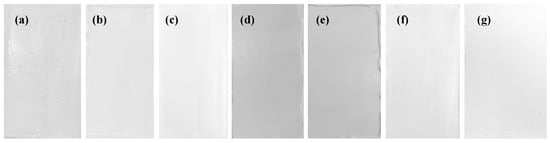

3.4. Salt Spray Test

The corrosion resistance of the as-prepared coatings with different ratios was evaluated by neutral salt spray test [44,45]. Figure 5 shows digital images of the as-prepared coatings (A:B = 3:1–6:1) and the 60% Ep-Zn coating after 0 h, 1000 h, and 3000 h salt spray treatment. As shown in Figure 5(a-1–f-1), all the coatings used for the experiments have smooth surfaces. After 1000 h and 3000 h salt spray treatment, the as-prepared Ep-PSA coatings remained smooth (Figure 5(a-2–d-2,a-3–d-3)), and no blistering or peeling was observed. For the Ep-Zn coating, after 1000 h salt spray treatment, obvious blistering was observed (Figure 5(e-2–f-2)), and after 3000 h salt spray treatment, a large number of cracks appeared on the surface of the coating, which means that the coating has lost its shielding effect against corrosive media.

Figure 5.

The as-prepared Ep-PSA coatings (A:B = 3:1~6:1) and the 60% Ep-Zn coating after 0 h (a-1–f-1), 1000 h (a-2–f-2), and 3000 h (a-3–f-3) salt spray treatment.

Meanwhile, components A and B of the coating were mixed in a ratio of 4:1 and then applied to RCS sheets for a 6000 h salt spray test (Figure 6a–f). The results show that after 6000 h of salt spray treatment, the surface of the coating remained smooth and flat, and no obvious blistering or cracking was observed. These results indicate the excellent corrosion resistance of the as-prepared EP-PSA coating.

Figure 6.

The as-prepared coating applied to rusty carbon steel sheets for (a) 0, (b) 1000, (c) 2000, (d) 3000, (e) 4000, (f) 5000, and (g) 6000 h of salt spray exposure.

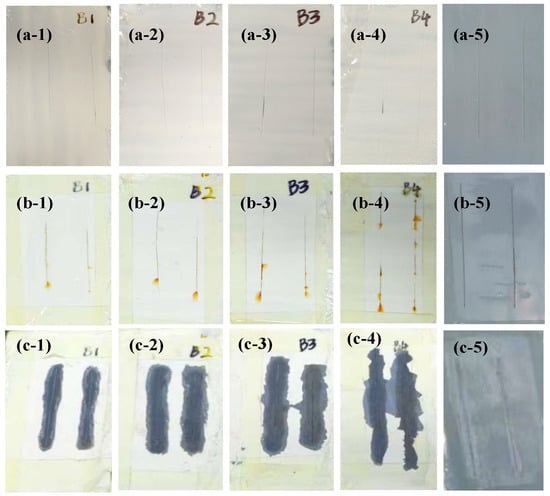

Also, the salt spray experiment was carried out after the as-prepared Ep-PSA coatings (A:B = 3:1~6:1) and the 60% Ep-Zn coating were scratched (Figure 7(a-1–a-5)), then placed in the salt spray chamber for 7 days to simulate the spread of rust after the coating was damaged. After a 7-day salt spray treatment, some reddish-brown rust stains were observed around the scratches (Figure 7(b-1–b-5)), indicating that the metal at the scratched area had undergone corrosion. The coating near the scratch was removed to observe the spread of the rust layer (Figure 7(c-1–c-5)). The results show that the rust on the metal base surface did not spread beneath the coating. This indicates that even if the coating is partially damaged, the undamaged coating can still effectively prevent the spread of corrosion. This can be attributed to the excellent adhesion between the coating and the metal substrate.

Figure 7.

Scratches on the as-prepared Ep-PSA coatings (A:B = 3:1~6:1) and the 60% Ep-Zn coating (a-1–a5) before and (b-1–b-5) after a 7-day salt spray treatment; (c-1–c-5) the coating near the scratch was removed to observe the spread of the rust layer.

3.5. Electrochemical Corrosion Resistance Test

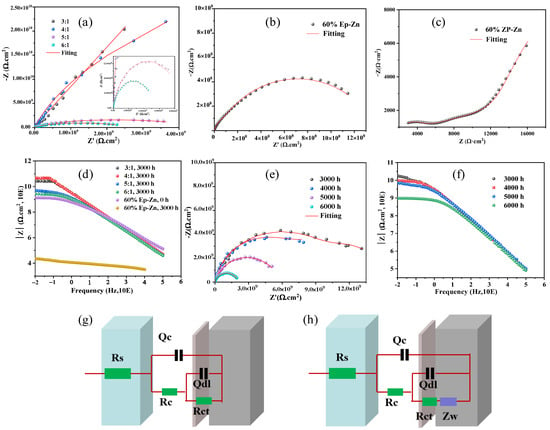

The corrosion protection properties of the as-prepared EP-PSA coating with component ratios of A:B from 3:1 to 6:1 and the commercially available 60% EP-Zn coating on Tin substrates were assessed using EIS measurements [19,44]. Figure 8a illustrates the Nyquist curves of EP-PSA coatings with component ratios of A:B from 3:1 to 6:1 after 3000 h salt spray exposure in a 3.5 wt% NaCl solution (pH = 7). In Nyquist curves, the larger capacitive loop indicates the superior corrosion protection ability of the coating composite [25]. After 3000 h salt spray, the radius of the capacitive loop of the as-prepared EP-PSA coatings from large to small is: 4:1 > 3:1 > 5:1 > 6:1. Generally, the impedance modulus at 0.01 Hz diagram (|Z|0.01Hz) is regarded as a reliable indicator of coating barrier properties [25,45]. As it can be seen from the Bode diagram in Figure 8d, the |Z|0.01Hz values for the EP-PSA coating with component ratios of A:B from 3:1 to 6:1 are 2.61 × 1010, 4.61 × 1010, 4.91 × 109, and 2.64 × 109 Ω·cm2, respectively. According to the above results, the EP-PSA coating composite with an A:B ratio of 4:1 has the optimum corrosion resistance compared with the other three coatings, suggesting that excessive or insufficient curing agent will significantly weaken the anti-corrosion performance. Excessive curing agent causes the resin to undergo excessive cross-linking reaction, resulting in a dense but rigid three-dimensional network structure. This leads to a decrease in adhesion to the metal substrate, thereby reducing its anti-corrosion performance. When the curing agent is insufficient, the cross-linking process is incomplete, resulting in insufficient coating strength, a loose microstructure, and a decline in shielding performance.

Figure 8.

(a) Nyquist curves of the Ep-PSA coating in A,B component ratio range of 3:1~6:1 after 3000 h salt spray treatment on the Tin substrate, the 60% Ep-Zn coating after (b) 0 h and (c) 3000 h salt spray treatment on the Tin substrate, (d) and their corresponding Bode diagram. (e) Nyquist curves of the EP-PSA coating in A,B component ratio range of 4:1 after 3000~6000 h salt spray treatment on the RCS substrate, (f) and their corresponding Bode diagram. (g,h) Equivalent circuit models.

Nyquist curves and Bode diagrams of the commercially available 60% EP-Zn coating before and after 3000 h salt spray treatment were recorded. Before salt spray treatment (Figure 8b), the capacitive loop was 1.19 ×109 Ω·cm2, which was much smaller than that of the as-prepared EP-PSA coatings. After being subjected to salt spray treatment for 3000 h (Figure 8c), the coating began to deteriorate, and its capacitive loop radius rapidly decreased by five orders of magnitude. This indicates that the coating has lost its protective effect on the metal substrate. The |Z|0.01Hz values for 60% EP-Zn coating with 0 and 3000 h salt spray treatment were 1.31 × 109 and 2.26 × 104 Ω·cm2, respectively (Figure 8d). It should be mentioned that, before the salt spray treatment for 3000 h, the as-prepared EP-PSA coating was unable to obtain electrochemical impedance data due to its excessively high resistance. The experiment results show that the coating prepared in this study has a much better anti-corrosion performance than the commercially available 60% EP-Zn coating.

Furthermore, the corrosion protection properties of the as-prepared EP-PSA coating with a component ratio of A:B = 4:1 on RCS substrates were assessed by EIS measurements after salt spray treatment for 3000, 4000, 5000, and 6000 h. As can be seen from Figure 8e, after 3000 h, 4000 h, 5000 h, and 6000 h of salt spray tests, the impedance radius of the coating gradually decreased, indicating that the corrosion resistance of the coating was gradually declining. Based on the corresponding Bode diagram in Figure 8f, the |Z|0.01Hz values for 3000 h, 4000 h, 5000 h, and 6000 h of salt spray tests are 3.34 × 1010, 9.48 × 109, 9.07 × 109, and 9.64 × 108 Ω·cm2, respectively. It can be seen that despite undergoing the 6000 h salt spray test, its |Z|0.01Hz value remained close to 109 Ω·cm2, indicating that it still had excellent shielding performance and could effectively prevent the corrosive medium from contacting the substrate. Experimental results showed that the rust layer did not affect the overall anti-corrosion performance of the coating, which can be ascribed to a chemical reaction that occurred between the coating and the rust layer, causing the metal oxides to be encapsulated within the coating and serve as a type of filler. The as-prepared EP-PSA anti-corrosion coating meets the requirement of low surface treatment while providing excellent anti-corrosion effects.

Further, to better understand the corrosion process, the Nyquist and Bode plots of the as-prepared EP-PSA coatings were fitted by suitable equivalent electrical circuits (Figure 8g,h). The relevant electrochemical parameters Rs, Rc, and Rct are represented as solution resistance, coating resistance and charge transfer resistance, respectively. A constant phase element (Qc) was used instead of the ideal capacitance due to the “scattering effect” caused by the uneven surface of the coating [17]. Qdl is the double layer capacitance between electrode and the rusty layer on the carbon steel or the tin coating on the surface of tin plate. The equivalent circuits used in the fitting process for the 60% EP-Zn coating after 3000 h salt spray treatment are shown in Figure 8h. In Figure 8h, Warburg impedance element (Zw) was also employed due to the diffusion of electrolytes through the coatings after 3000 h salt spray treatment.

3.6. Corrosion Protection Mechanisms

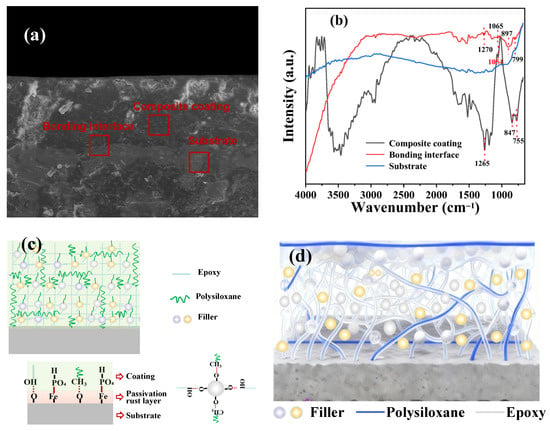

In order to find out the binding mechanism of the EP-PSA coating to the carbon steel substrate, the micro-IR spectroscopy of the binding interface, composite coating, and the substate were carried out (Figure 9a,b). As it can be seen from Figure 9b, the carbon steel substrate almost has no infrared absorption peaks. The EP-PSA composite coating exhibits strong infrared absorption peaks, and the characteristic bands at 1265 cm−1, 1054 cm−1, 847 cm−1, and 755 cm−1 can correspond to P=O, P-O, C-OH, and P-OH, respectively [46,47], while those functional groups show weak infrared absorption bands in the binding interface of 1270 cm−1, 1065 cm−1, 897 cm−1, and 799 cm−1, respectively. The infrared absorption redshift of the P=O, P-O, C-OH, and P-OH implies the phosphating reaction and hydrogen bond interaction between the EP-PSA composite coating and the metal substrate. Based on the above results and investigation, the corrosion protection mechanism of the as-prepared EP-PSA coating composite is proposed in Figure 9c,d. Firstly, the Zn3(PO4)2 component in the coating can undergo a phosphating reaction with the metal surface oxides [48,49]:

Figure 9.

(a,b): Micro-IR characteristics of the coating, bonding interface and metal substrate of coatings; (c,d): anti-corrosion mechanism diagram of the as-prepared EP-PSA coating.

- (1)

- Zn3(PO4)2 + 2H+ → 2HPO42− + 3Zn2+.

- (2)

- Fe2+ + 2HPO42− → FeHPO4 ↓ + H2PO4−.

- (3)

- FeHPO4 + H2O → Fe3(PO4)2 ↓ + H3PO4.

This phosphating reaction forms a dense oxide film on the metal surface. At the same time, the solvent-free epoxy resin has excellent permeability and can seal the rust layer as a filler of the coating, reducing the requirements for surface treatment of the metal during construction. On the other hand, through this phosphating reaction, an organic–inorganic hybridization between the coating and the metal substrate is achieved, significantly enhancing the adhesion of the coating. Meanwhile, the EP resin and the PSA resin also enhance the adhesion between the coating and the substrate through hydrogen bonds formed with the oxide substances on the metal surface. Through the synergistic effect of phosphating reaction and hydrogen bonding, the coating is endowed with excellent adhesion, ensuring that the coating will not bubble or peel off during its service period (Figure 9c).

Secondly, an interpenetrating polymer network (IPN) was constructed by employing EP resin as the main molecular network and PSA as the guest molecule, and the interfacial chemistry is regulated by nano ceramic powder and high-strength metal powder (Figure 9d) [50]. The IPN structure is formed by EP and PSA resin through optimization of physical penetration and non-bonding interactions [50]. The nano ceramic powder and high-strength metal powder interact with the epoxy resin and polysiloxane resin through hydrogen bonds, forming a more complex and dense interpenetrating network, which effectively prevents the corrosive medium from invading the metal substrate. Thirdly, the main chain of Si-O-Si in the PSA component is significantly flexible [29,46], which can effectively regulate the rigidity of epoxy resins and prevent the coating from cracking due to deformation caused by force or temperature changes during use. In summary, the excellent adhesion of the coating enables good bonding between the coating and the substrate, ensuring that it will not bubble or peel off during its service period. The complex and dense interpenetrating network can effectively prevent the corrosive medium from invading the metal substrate. The flexibility can effectively prevent the coating from cracking. The synergy of the above three characteristics has endowed the coating with excellent anti-corrosion performance.

4. Conclusions

In summary, this work introduces an original EP-PSA ceramic metal coating that uniquely combines >95% solid content with low-surface-treatment applicability, addressing the long-standing trade-off between environmental compliance and field practicality in large-scale anti-corrosion engineering. Experimental results confirm that the EP-PSA coating exhibits intact surface morphology without cracks or holes and achieves good adhesion to rust layers and various metal substrates (maximum adhesion of 14.28 MPa on standard steel plates). Notably, it maintains excellent acid, alkali, and salt resistance, with no bubbling or detachment observed after 6000 h of salt spray treatment and an impedance modulus at 0.01 Hz remaining close to 109 Ω·cm2. In sharp contrast, the commercial 60% EP-Zn coating blisters after 3000 h of salt spray, and its impedance modulus at 0.01 Hz plummets from 109 Ω·cm2 to 104 Ω·cm2 after 3000 h. The outstanding anti-corrosion performance of the EP-PSA coating is mainly attributed to the synergistic effect of its robust adhesion, good flexibility, and unique IPN structure. This study provides a new technical approach for the development of high-performance, eco-friendly, and easy-to-apply anti-corrosion coatings, laying a foundation for their practical application in harsh industrial environments. Despite the significant progress achieved, this study still has certain limitations that need to be addressed in future research: The viscosity of the prepared high-solid-content coating needs to be further reduced. Future research will focus on addressing the core limitation of the current study, breaking the inherent trade-off between solid content and viscosity of high-solid-content coatings.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.L., L.F., Q.J. and B.H.; methodology, X.L., M.Z. and B.H.; software, Q.J. and S.H.; validation, X.L., C.S. and J.L.; formal analysis, L.F., M.Z., C.S. and B.H.; investigation, X.L.; resources, Q.J., L.F. and J.L.; data curation, X.L. and S.H.; writing—original draft preparation, X.L. and C.S.; writing—review and editing, L.F., J.L., C.S. and B.H.; visualization, X.L., Q.J., S.H. and M.Z.; supervision, J.L. and B.H.; project administration, X.L., Q.J. and S.H.; funding acquisition, X.L., Q.J. and M.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This project was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Guangxi province (2025GXNSFBA069320), the Guangxi Provincial Central Guidance Local Science and Technology Development Project (Guike ZY24212001), and the Science and Technology Program of Guangxi Province (Guike JF2503980019).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Songqiang Huang was employed by the company Liuzhou Bureau, EHV Power Transmission Company, China Southern Power Grid Co., Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Wang, K.; Wang, C.; Dong, Q.; Wang, K.; Qian, J.; Liu, Z.; Huang, F. Enhancing corrosion and abrasion resistances simultaneously of epoxy resin coatings by novel hyperbranched amino-polysiloxanes. Prog. Org. Coat. 2024, 196, 108680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Z.; Zhang, C.; Shan, J.; Ying, F.; Lu, K.; Hao, Q.; Xia, M.; Xia, X.; Lei, W. Active anti-corrosion and fluorescence self-detection coatings with mussel-inspired hexagonal boron nitride-based multifunctional nanocontainers. Prog. Org. Coat. 2026, 210, 109733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Song, Y.; Ma, J.; Yang, J.; Chen, D.; Gong, H.; Li, G.L. Intrinsic self-healing polymer coatings with autonomous corrosion protection based on synergistic healing mechanisms. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2025, 709, 163641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Ren, C.; Wang, J.; Liu, T.; Yang, H.; Wang, Y.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, D. Self-reporting coatings for autonomous detection of coating damage and metal corrosion: A review. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 421, 127854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amune, U.O.; Solomon, M.M.; Hu, D.; He, J.; Tesema, F.B.; Umoren, S.A.; Gerengi, H. A comprehensive review of stimulus-based smart self-healing coatings for substrate protection. Prog. Org. Coat. 2026, 210, 109669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen Gupta, S.; Baksi, A.; Subramanian, V.; Pradeep, T. Cooking-Induced Corrosion of Metals. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2016, 4, 4781–4787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Wang, J.; Chen, Z. A dual-responsive self-healing coating utilizing Ti3C2TxMXene with pH and NIR sensitivity for metal corrosion protection. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2025, 727, 138134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, C.; Chen, K.; Wang, X.; Wang, X.; Wu, C.; Gao, G.; Kong, X. Sprayed dual-layer epoxy coatings with enhanced superhydrophobic stability, corrosion resistance, and mechanical robustness for industrial metal protection. Mater. Today Commun. 2025, 49, 114227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, K.; Zhang, J.; Zhou, J.; Ye, Y.; Wu, J.; Zhong, M.; Yan, X.; Zhang, B. Self-Powered Metal Corrosion Protection System Based on Bi2Ti2O7 Nanoparticle/Poly(vinyl chloride) Composite Film. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2025, 8, 3862–3875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nwanonenyi, S.C.; Daniyan, A.A.; Idris, M.B.; Ige, O.O. Corrosion control through sacrificial anodes: A review of aluminium alloys in oil and gas applications. Hybrid Adv. 2025, 11, 100571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang Bui, H.; Hai Tan, K. Optimising zinc sacrificial anode configurations for corrosion protection in patch-repaired reinforced concrete Slabs: Experimental insights and underlying electrochemical mechanisms. J. Build. Eng. 2025, 108, 112915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budiman, F.; Rahmawati, D.; Aulia, D.; Sukma, V.F.; Ter, T.P.; Masood, J.A.I.S.; P.S., R.; Nurhidayat, A.; Mbarep, D.P.P.; Sasto, I.H.S.; et al. Integrating IoT-enabled automated impressed current cathodic protection systems with metal potential monitoring: A digital technology approach to address corrosion for promoting environmental ecosystem conservation. Measurement 2026, 258, 119167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; Luo, N.; Liu, Y.; Li, H.; Wang, D. A New Self-Healing Triboelectric Nanogenerator Based on Polyurethane Coating and Its Application for Self-Powered Cathodic Protection. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2022, 14, 10498–10507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, X.; Ma, L.; Wang, X.; Shi, B.; Fu, Z.; Liu, D.; Zhao, J.; Lu, L.; Zhang, D. Revealing the atomic-scale mechanism of organic corrosion inhibitors in suppressing anodic dissolution of metals via ab initio molecular dynamics and metadynamics simulations: A case study of sorbitol on aluminum. Corros. Sci. 2025, 257, 113326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, L.; Zhao, R.; Yue, H.; Liu, H.; Li, B.; Xie, F.; Tian, X.; Shang, W.; Jiang, J.; et al. Extraction of lignin from lignocellulosic biomass (bagasse) as a green corrosion inhibitor and its potential application of composite metal framework organics in the field of metal corrosion protection. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 293, 139271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.; Kim, K.Y.; Choi, W. Photoelectrochemical Approach for Metal Corrosion Prevention Using a Semiconductor Photoanode. J. Phys. Chem. B 2002, 106, 4775–4781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Lei, Y.; Zeng, Q.; Li, C.; Sun, G.; You, B.; Ren, W. Hydrogenated castor oil modified graphene oxide as self-thixotropic nanofiller in high solid polyaspartic coatings for enhanced anti-corrosion performance. Prog. Org. Coat. 2022, 167, 106836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, C.; Li, Z.; Bi, H.; Dam-Johansen, K. Towards sustainable steel corrosion protection: Expanding the applicability of natural hydrolyzable tannin in epoxy coatings via metal complexation. Electrochim. Acta 2024, 497, 144546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, M.; Mehtab, S.; Zaidi, M.G.H.; Shukla, V.K.; Kumar, P.; Rai, A.K. Enhanced Corrosion Protection of Mild Steel with Ferrocene-Fortified Graphite Epoxy Coatings. ACS Appl. Eng. Mater. 2025, 3, 4037–4049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Zhou, C.; Xiong, W.; Peng, J.; Luo, X.; Pan, X.; Liu, Y. Long-lasting anti-corrosion direct-to-metal polyurethane NP-GLIDE coatings based on the coordination effect and dual cross-linking of polyphenol. J. Colloid. Interface. Sci. 2025, 678, 742–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabzehmeidani, M.M.; Kazemzad, M. Insight into the microstructural characteristics and corrosion properties of AZ31 Mg alloy coated with polyurethane containing nanostructures of copper metal organic frameworks. Mater. Lett. 2023, 341, 134294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Wang, Q.; Wang, G.; Liang, J.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, S.; Liu, Y.; Chen, Q.; Zhao, G.; Liu, Y. Impressive reinforcement on the anti-corrosion ability of the commercial fluorocarbon paint via nitrogen-doped super-easily-dispersed graphene. Diam. Relat. Mat. 2023, 136, 109923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, F.; Zhou, C.; Wu, J.; Zhao, N.; Zhao, C.; Yuan, J.; Pan, Z.; Pan, M. CTFE ternary copolymerization confined in waterborne polyurethane for enhanced mechanical and anti-corrosion performances of fluorocarbon coatings. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 509, 161476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Zhang, S.; Song, Y.; Qin, H.; Xiong, C.; Wang, S.; Yang, Q.; Xie, D.; Fan, R.; Chen, D. A novel and green 3-amino-1,2,4-triazole modified graphene oxide nanomaterial for enhancing anti-corrosion performance of water-borne epoxy coatings on mild steel. Prog. Org. Coat. 2024, 187, 108106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Q.; Huang, S.; Tang, D.; Li, H.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, Z.; Hu, H.; Gan, T. High-solid and water-based epoxy resin anti-corrosion coatings for complex construction environments: Synergistic effect of inorganic-organic hybrid and grafted long chain structure. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2025, 687, 162299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, Y.; Li, Z.; Chen, L.; Wang, Y.; Gao, Y. Treatment of the Rust Layer by Different Pyridine Derivatives and Its Effect on the Epoxy-Polyvinylbutyral Coating Directly Painted onto the Rust Mild Steel. Int. J. Electrochem. Sci. 2017, 12, 11728–11741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM D2697-23; Standard Test Method for Volume Nonvolatile Matter in Clear or Pigmented Coatings. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2023.

- ISO 8501-1:2007; Preparation of Steel Substrates Before Application of Paints and Related Products—Visual Assessment of Surface Cleanliness—Part 1: Rust Grades and Preparation Grades of Uncoated Steel Substrates and of Steel Substrates After Overall Removal of Previous Coatings. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2007.

- Ni, H.; Daum, J.L.; Thiltgen, P.R.; Soucek, M.D.; Simonsick, W.J.; Zhong, W.; Skaja, A.D. Cycloaliphatic polyester-based high-solids polyurethane coatings: II. The effect of difunctional acid. Prog. Org. Coat. 2002, 45, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Ma, Y.; Zhang, B.; Lei, B.; Li, Y. Enhancement the Adhesion between Epoxy Coating and Rusted Structural Steel by Tannic Acid Treatment. Acta Metall. Sin. Engl. Lett. 2014, 27, 1105–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Li, M.; Huang, Y.; Hu, M.; Li, L. Facile preparation of magnolol-based epoxy resin with intrinsic flame retardancy, high rigidity and hydrophobicity. Ind. Crops Prod. 2023, 192, 116124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Li, Y.; Huan, D.; Zhang, H.; Zhu, C. Introducing rigid-flexible integrated structure and constructing sacrificial bonds to achieve mechanically robust and malleable epoxy resin. Mater. Today Commun. 2024, 40, 109688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Li, M.; Hou, D.; Yin, B.; Chen, B.; Li, Z. Topologically optimized polystyrene acrylate-polysiloxane copolymer coatings toward superior durability of cementitious materials. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 427, 136106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Hou, D.; Wang, P.; Li, M.; Xu, H.; Han, S. Investigation of polysiloxane coatings with two-components for synergistic improved corrosion resistance of cementitious materials. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 449, 138142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB/T 1725-2007; Paints, Varnishes And Plastics—Determination Of Non-Volatile Matter Content. General Administration Of Quality Supervision: Beijing, China, 2007.

- GB/T6739-2022; Paints and Varnishes—Determination of Film Hardness by Pencil Test. National Technical Committee on Paints and Pigments of Standardization Administration of China (SAC/TC 5): Beijing, China, 2023.

- GB/T 1731-2020; Determination of Flexibility of Coating and Putty Films. The State Administration for Market Regulation: Beijing, China, 2020.

- ASTM D2801-1994; International Standard ASTM D2801-1994 Flow Leveling Tester for Panit and Coatin—AliExpress 1420. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 1994.

- GB/T 5210-2006; Paints and Varnishes—Pull-Off Test for Adhesion. General Administration of Quality Supervision Inspection and Quarantine: Beijing, China, 2006.

- GB/T 30648.1-2014; Paints and Varnishes—Determination of Resistance to Liquids—Part 1: Immersion in Liquids Other Than Water. The State Administration For Quality Supervision: Beijing, China, 2014.

- GB/T 1771-2007; Paints and Varnishes—Determination of Resistance to Neutral Salt Spray (Fog). The State Administration For Quality Supervision: Beijing, China, 2007.

- Wang, J.; Zhang, L.; Li, C. Superhydrophobic and mechanically robust polysiloxane composite coatings containing modified silica nanoparticles and PS-grafted halloysite nanotubes. Chin. J. Chem. Eng. 2022, 52, 56–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Liang, J.; Yang, Y.; Liu, B.; Cheng, C.; Hu, C. An anticorrosive coating based on polysiloxane with good chemical stability and long-term corrosion resistance. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2024, 325, 129717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.; Xu, F.; Meng, L.; Yu, C.; Fu, D.; Chang, Y.; Sun, Y.; Wang, H. A versatile thin polysiloxane composite coating targeting for threads endowed with properties of anti-corrosion and friction reduction. Prog. Org. Coat. 2022, 172, 107131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Liu, L.; Li, J.; Zhao, J.; Gu, C.; Liu, B.; Wang, D.; Zhang, S.; Jian, X.; Weng, Z. Engineering polyaryl ether coatings bearing phthalazinone moiety resistant to salt spray corrosion. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2025, 686, 162148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, J.; Liao, X.; Li, W.; Lin, X.; Hu, H.; Zhang, Y.; Gan, T.; Huang, Z. Preparation of pH sensitive P-doped carbon dots-loaded starch/polyvinyl alcohol packaging film for real-time monitoring freshness of pork. Food Biosci. 2024, 61, 104654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, X.; Chen, Y.; Fan, L.; Chen, J.; Tian, Q.; Jiang, Q.; Lai, J.; Sun, C.; Hou, B. “Off-on” fluorescence sensor based on phytic acid carbon dots for OH−/H+ detection in metal corrosion. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2025, 682, 161680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aswathy, S.P.; Vaisakh, S.S.; Archana, S.R.; Dilimon, V.S.; Kumar, A.S.; Shibli, S.M.A. pH-controlled shape selective synthesis of lanthanum phosphate nanoparticles for enhanced NIR reflectance and thermal shielding in tunable zinc phosphate coatings. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 503, 144546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barsana, S.A.; Magesan, P.; Jayamoorthy, K.; Umapathy, M.J. Improved corrosion resistance of mild steel with poly (vinyl pyrrolidone) incorporated zinc phosphate coating. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 2026, 178, 106363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Hou, D.; Yin, B.; Chen, B.; Li, Z. A polystyrene acrylate-polysiloxane multicomponent protective coating with interpenetrating polymer network structure for cementitious materials. Prog. Org. Coat. 2024, 195, 108640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.