Abstract

The anomalous flow behavior of the γ′-Ni3Al phase at high temperature is closely related to a cross-slip of super-partial dislocations. The acceleration of cross-slips induced by the addition of rhenium (Re) is known as Re-effects. In this work, by means of a series of lattice transitions, a hybrid model including a preexisting anti-phase boundary was constructed to assess the difficulty of cross-slips of super-partial dislocations from planes to planes in the γ′-Ni3Al phases, and the impact of the addition of Re on these dislocation mediated creep resistances was reinvestigated by first-principles calculations. The results showed that the addition of Re at preferential Al sublattice sites was indeed beneficial for the cross-slip of the first leading super-partial dislocations, and the existence of could promote cross-slip of second leading super-partial dislocations. A detailed calculation of stacking fault energies demonstrated that an obvious Suzuki segregation of Re existed at and , and Re preferentially occupied Ni sublattice sites. It is found Re-segregations at were disadvantageous for the cross-slip of new super-partial dislocations, but the formation of more Kear-Wilsdorf dislocation locks could benefit from Re-segregations at .

1. Introduction

Ni-based single crystal (SC) superalloys, consisting of a large number of γ′ precipitates with L12 structures embedded coherently in fcc γ matrix, are widely used in turbine blades for modern aero-engines and industrial gas turbines due to their exceptional mechanical properties and high-temperature creep resistance [1,2,3]. Their excellent performance is primarily attributed to their anomalous flow behavior at high temperature [4] and the presence of significant amounts of refractory strengthening elements, such as Re, W, Mo, Ta, Ti, Cr, and Ru [5,6,7]. Previous investigations have shown that refractory elements play an important role in the movement of dislocations in the γ’ phase, among which the reinforcement of creep resistance caused by the addition of Re is known as Re-effect [8,9]. Re not only can reduce intrinsic stacking fault energies in the γ matrix and raise anti-phase boundary (APB) energies in the γ′ phase but also can slow down the coarsening kinetics of γ′ precipitates and dislocation climb rates in the γ matrix due to its slow diffusion coefficient [10], and even facilitates modifications of the misfit between the γ matrix and γ′ precipitates and further lead to the interfacial dislocation networks to be enriched [11]. However, an excessive addition of Re easily leads to the precipitation of a topologically close-packed (TCP) phase, which can in turn accelerate alloy failure [12]. Previous investigations [13,14] have confirmed that when a part of Re is replaced by W, the mechanical properties of Ni-based SC superalloys remain virtually unchanged, which indicates that the addition of W has similar strengthening effects to that of Re.

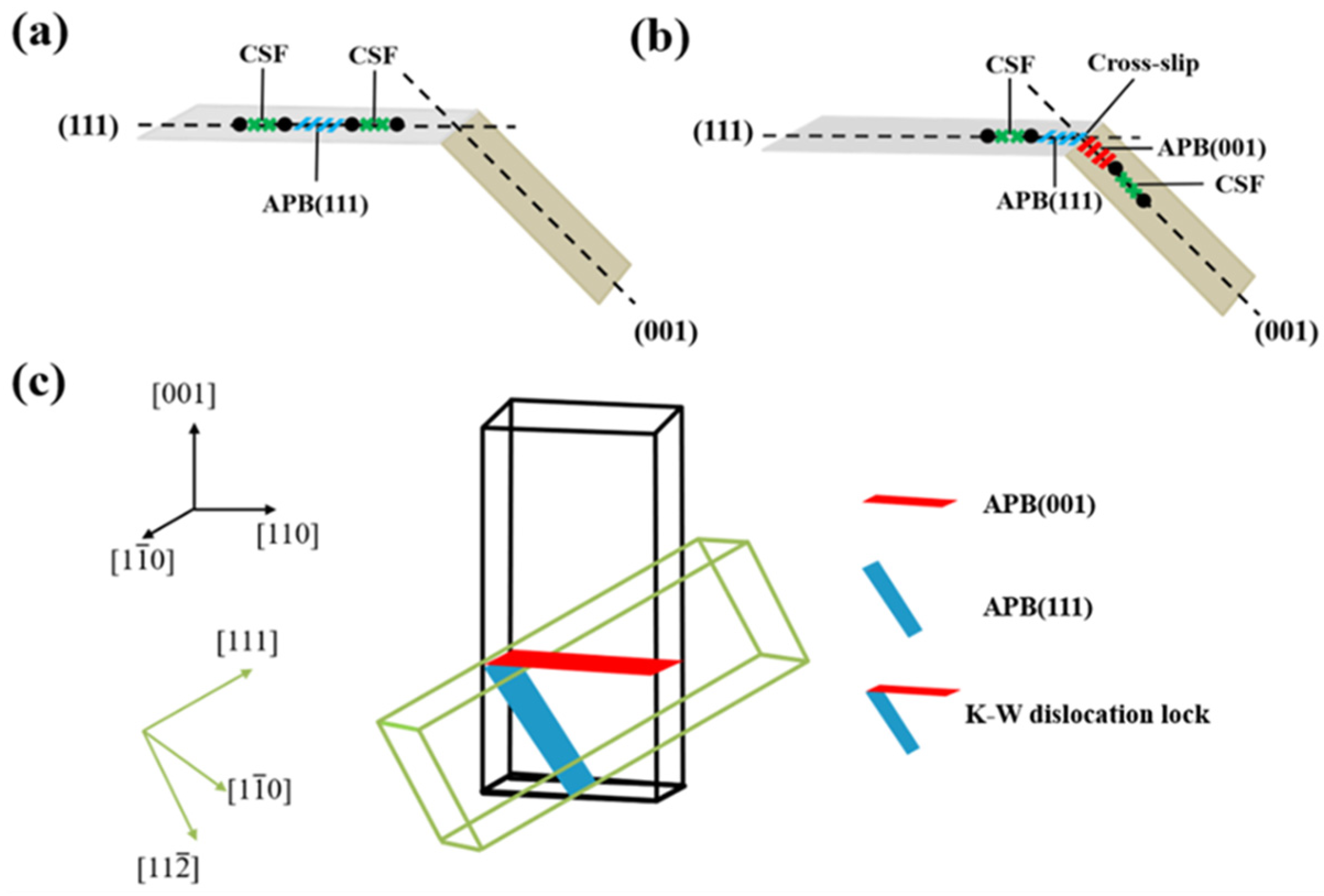

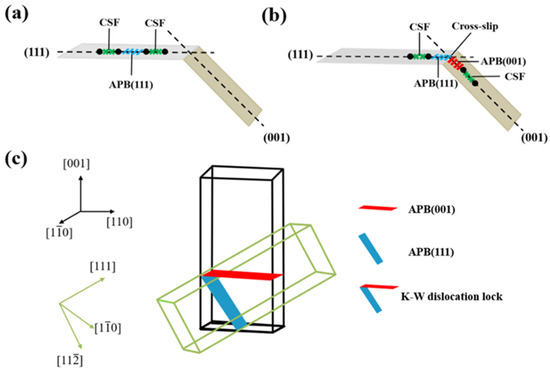

The anomalous flow behavior of the γ′ phase at high temperature, i.e., an increase in yield strengths with increasing temperature [15], can be attributed to the obstacle of Kear-Wilsdorf (K-W) dislocation lock [4] of the movement of subsequent dislocations. At the early stages of creep, a dislocation is first activated in the γ channels. With the increase in dislocation densities in the γ phase, a dislocation network is formed at the γ/γ′ interface, and some pairs can combine to form super dislocations. Once inside the γ′ phase, these super locations will be separated to super-partial dislocation pairs connected by an anti-phase boundary (APB), i.e., [16]. Then, the two super-partial dislocations will further separate into Shockley partial dislocations separated by a complex stacking fault (CSF), i.e., , referred to Figure 1. That is to say, the decomposed super dislocation consists of four Shockley dislocations separated by two CSFs and one APB. Since Shockley partials connected by the CSF cannot undergo a cross slip from the planes to the planes, a temporary recombination of Shockley partials to form a dislocation is required. As is well known, a high CSF energy means a narrow CSF region, and thus, a high level of CSF energy will be beneficial for the recombination of Shockley partials into dislocations. After two dislocations have formed by recombination, their elastic interactions can provide the driving force for a cross-slip of the leading super-partial dislocation from the {111} plane to the {001} plane. And a high anti-phase boundary energy in the {111} plane relative to in the {001} planes is more favorable for the cross-slip of super-partial dislocations [17]. In this case, a K-W dislocation lock can be formed after the cross slips of the leading super-partial dislocation. As a result, the subsequent movement of the trailing Shockley partials dislocation pair will be restricted, leading to an improvement in the creep resistance of the γ′ phase. Therefore, it is widely accepted that this cross-slip of screw dislocations should be responsible for the anomalous flow behavior of the γ′ phase at high temperature.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of stacking faults (a) before cross-slip and (b) after cross-slip of super-partial dislocations and (c) K-W dislocation lock.

Since the anomalous flow behavior of the γ′ phase was first reported in 1957 [18], and Kear et al. [19] pointed out that this anomalous flow behavior can be attributed to the cross-slips of super-partial dislocations, K-W dislocation locks have been widely discovered in nickel-based superalloys [20,21,22,23]. To evaluate the tendency of cross-slips of the abovementioned dislocations in L12 ordered alloys, a Paidar-Pope-Vitek (PPV) model was proposed in 1984 [24,25], in which the cross-slip of super-partial dislocations could take place only if an APB anisotropy ratio = > . By the PPV model, Yu et al. [26] found that the addition of Re can promote the cross-slip of super-partial dislocations in the γ′ phase, and extra addition of Re seems to be more favorable [13]. It was revealed that the accelerated cross-slips mainly originated from an enlarged lattice misfit and an upraised APB energy [27,28]. Moreover, Zhao et al. [29] found that a large number of Re and W atoms can even stabilize K-W dislocation locks in the γ′ phase and further impede the movement of subsequent dislocations. Obviously, Re and W play an important role in the cross-slip of super-partial dislocations in the γ′ phase. However, previous calculations [13,24,25,26] for APB anisotropy ratio = were merely done using two separate models, in which the cross-slip of super-partial dislocations was separated into two irrelevant stages. In fact, the cross-slip of dislocations from to planes is a sequential and interrelated process. In the second stage of across-slips, there are some influences of the generated in the first stage on the subsequent movement of dislocations in the planes. In this case, for the reconstruction of surface slab models, the impact of preexisting on the anti-phase boundary energy of must be taken into account.

In this work, several hybrid slab models including of L12-Ni3Al(X) crystals with X = Re and W were first constructed to revisit the Re-effect in the dislocation slip mediated creep of the γ′-Ni3Al phase. And then, a Suzuki segregation tendency of Re and W in and and their preferential sites in Suzuki segregations were examined by and . Finally, the effect of Re-segregation on the cross-slip of super-partial dislocations was investigated.

2. Calculation Method

2.1. Reconstruction of Cross-Slip Models

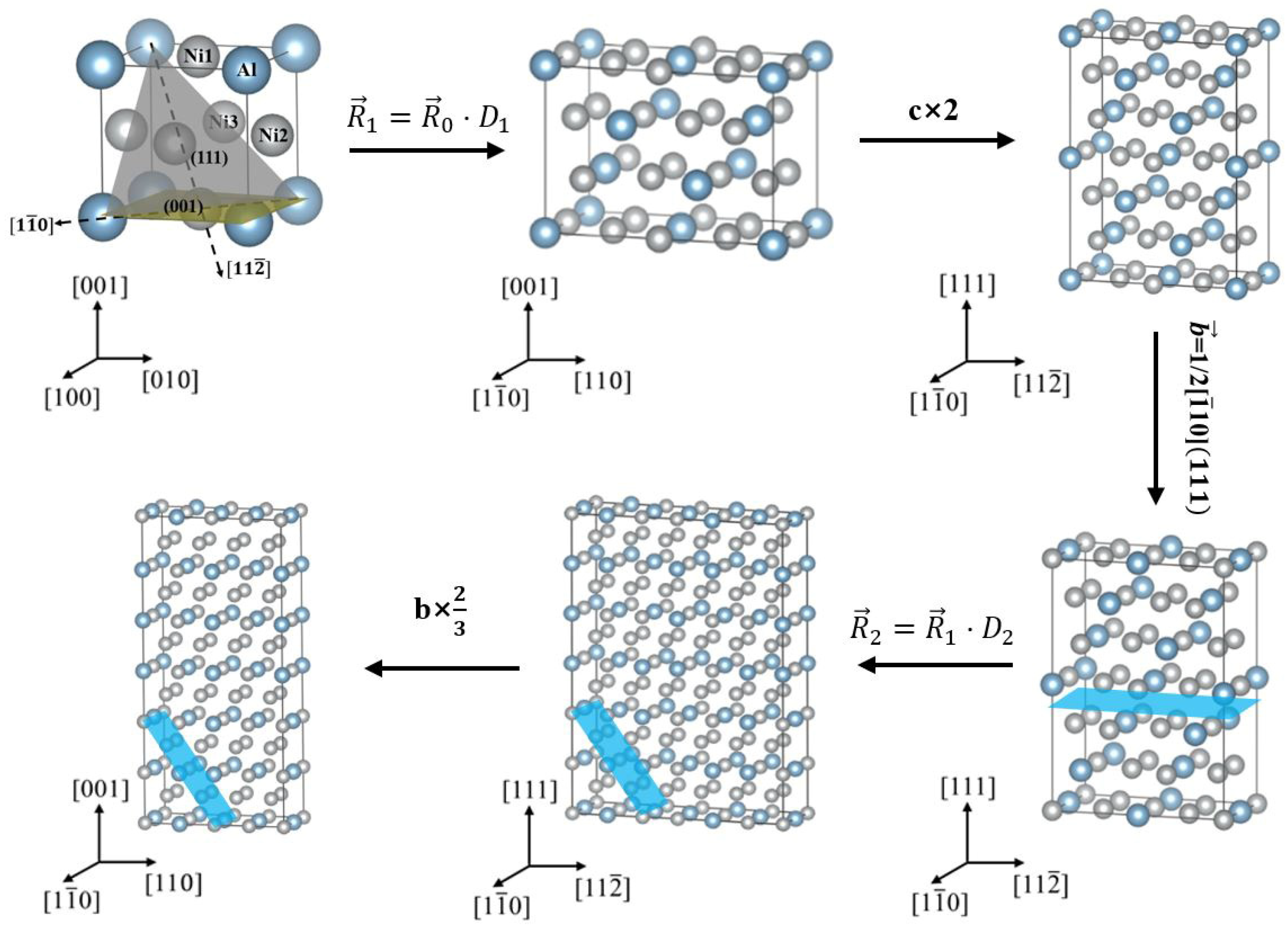

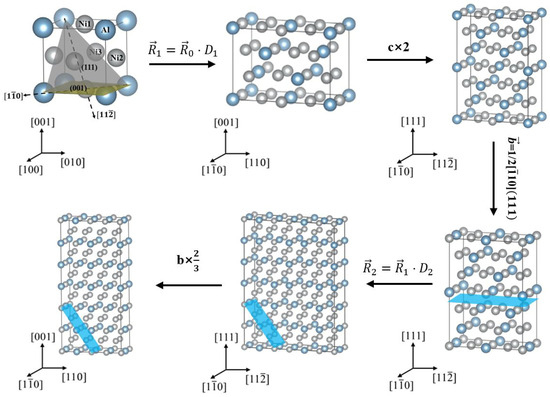

A slab model was first built using a redefined lattice method with rotation matrix . Here, the shear direction and the slip plane were rotated to be parallel to lattice vector and normal to lattice vector , as proposed by Roundy et al. and Ogata et al. [30,31]. In our calculation of the generalized stacking fault energies (Γ-surfaces), the atoms over the designated slip planes moved along the direction. As a result of shearing in the direction, an anti-phase boundary could be generated in the slab model, named slab model (refer to Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Schematic diagram of supercells reconstructed by matrix transformation. The gray, brown and blue shadows denote slipping planes, slipping planes, and , respectively.

In view of the preexistence of an on plane before the leading super-partial dislocation cross-slips from the plane to the plane, a hybrid slab model with was reconstructed. In this case, an slab model of 48 atoms composed of 6 atomic layers was taken as the first cell, and then a hybrid slab model of 144 atoms and 12 atomic layers was created by a redefined lattice method with rotation matrix . Herein, redefined lattice vectors and related to the slab model and hybrid slab model could be obtained by and , respectively, where represents the unit cell lattice vector. Their expressions are:

and the corresponding matrixes and are:

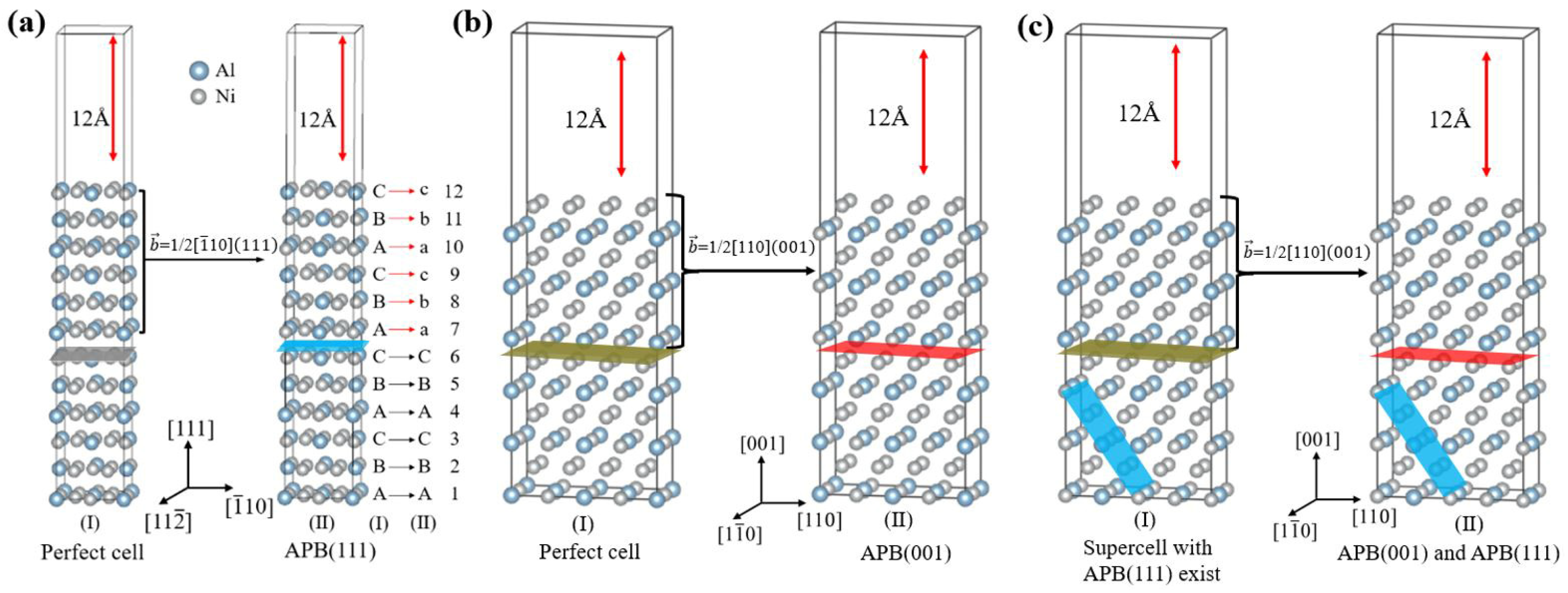

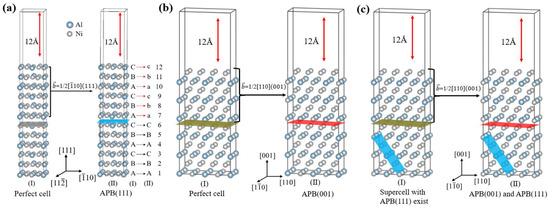

To compare the Γ-surfaces in the and surface models, this hybrid slab model of 144 atoms was stripped into the same 96 atoms as in the surface slab models along the plane, and a 12 Å vacuum region was added in the direction perpendicular to the slip plane to avoid interactions among faults in the two neighbor slabs. As atoms over the slip plane having been moved () in the direction, a new anti-phase boundary, i.e., , could be generated. Thus, a hybrid slab model of and associated with K-W dislocation lock, could be constructed, referred to Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Schematic diagrams of (a) in a simple model, (b) in a simple model, and (c) in a hybrid model for the calculation of Γ-surfaces. The gray and blue spares are Ni and Al atoms, respectively. The gray and brown shadows denote the and slipping planes, respectively. The blue and red shadows represent and , respectively.

2.2. Calculation Detail

First-principles calculations were performed using the Vienna ab initio simulation package (VASP) [32] based on density functional theory (DFT), in which a plane-wave basis set with a projector augmented wave (PAW) [33] is employed to describe the ion-electron interaction. For self-consistent field (SCF) calculation, the cutoff energy of plane wave functions was set at 400 eV, and the sampling of irreducible wedges of Brillouin zones was carried out with 7 × 5 × 1 regular Monkhorst–Pack grids of special k-points, corresponding to the 96-atom supercells. A conjugate gradient method [34] was utilized to optimize the geometry, and all atomic positions in the supercell were relaxed until the force on each atom was less than 0.009 eV/Å. The calculation of total energies and electronic structures was followed by cell optimization with an SCF tolerance of 1 × 10−5 eV under GGA-PBE potential [35].

Based on the different atomic environments around Al and Ni on the (001) and (111) surface models in the γ′-Ni3Al phase, the site doped with Re or W was marked as , , and (X = Re or W), corresponding to four non-equivalent sites, i.e., Al, Ni1, Ni2 and Ni3, in the Ni3Al unit cell, as shown in Figure 2. As for the segregation of Re or W at Al, Ni1, Ni2 and Ni3 sublattice sites in and , the same surface slab models of 96 atoms as that in the calculation of Γ-surfaces of perfect L12-Ni3Al crystals were named , , and models, respectively.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. A Comparison of Simple and Hybrid Models

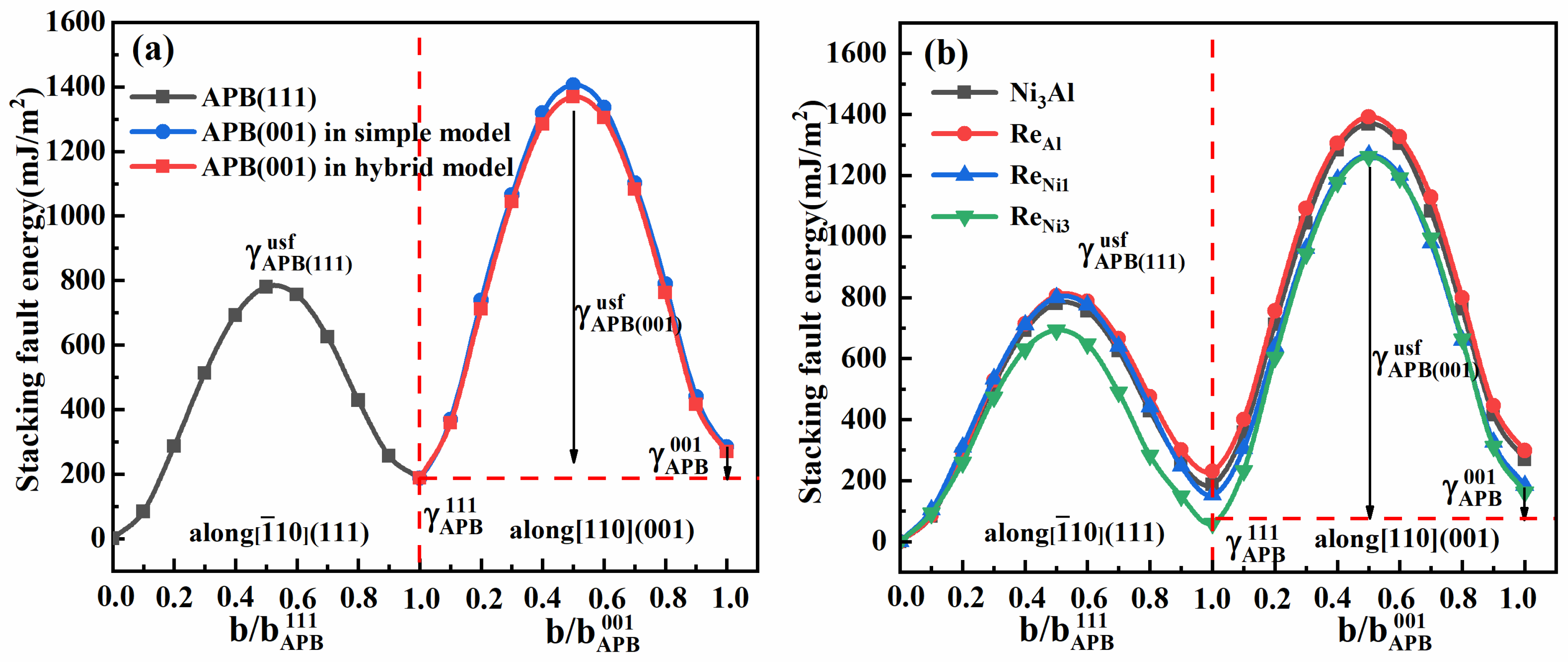

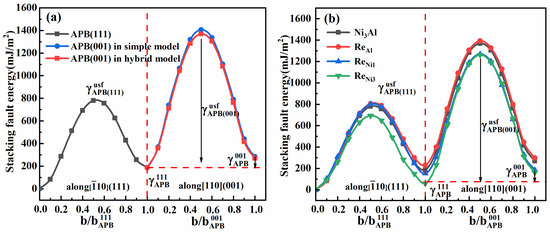

Generalized planar fault energy curves (i.e., Γ-surfaces) along the lowest energy path can provide a great deal of information on the nucleation and movement of dislocations. Since the anomalous flow behavior of the γ′-Ni3Al phase in Ni-based SC superalloys at high temperature is closely related to the cross-slip of super-partial dislocations, the Γ-surfaces associated with the cross-slip of super-partial dislocations from to slipping planes were first calculated using two simple models, as shown in Figure 3a,b. The results are illustrated in Figure 4a and further listed in Table 1. One can see that APB energy in the (111) planes and in (001) planes was mJ/m2 and mJ/m2, respectively. Obviously, is far higher than , which means that the cross-slip of super-partial dislocations was energetically favorable. However, it was observed that unstable stacking fault energies in the direction and in the direction were mJ/m2 and mJ/m2, respectively. As a measure of the energy release rate for dislocation nucleation relevant to the ductile response of a material, the unstable stacking fault energy represents an intrinsic energy barrier for activated stacking faults [36]. A high means that dislocations in plane are difficult to nucleate compared with super partials in planes. As is well known [17], strongly affects the cross-slip of super-partial dislocations. As being high, the tangential force component generated by the interaction of super-partial dislocations may significantly accelerate the cross-slip rate. In the PPV model [24,25], cross-slip can take place only if , and a large means that super-partial dislocations have a higher driving force from the to the planes. The present calculated was , which demonstrated that the cross-slip of super-partial dislocations from to planes can occur in γ′ phase, as reported in previous literature [3,13,37,38,39,40].

Figure 4.

The Γ-surfaces of cross-slips of super-partial dislocations from to planes in (a) Re-free and (b) Re-addition models.

Table 1.

APB energies , unstable stacking fault energies and APB anisotropy ratios = in Re-free models.

Further, the Γ-surface of the leading super-partial dislocations in the slipping planes were also calculated using the hybrid model including as shown in Figure 3c. The results are also illustrated in Figure 4 and listed in Table 1. From Figure 4a and Table 1, one can see that the and in the hybrid model decreased by mJ/m2 and mJ/m2, respectively, relative to the corresponding simple model, indicating that the existence of is conducive to the formation of and can accelerate the K-W dislocation lock to be formed. Also, this tendency can be deduced by increase in from 1.91 to 2.28. Since the anomalous flow stress of the γ′-Ni3Al phase at high temperature mainly arises from the restriction of K-W dislocation locks to the movement of the trailing super-partial dislocation, the present hybrid model, which accurately describes the cross-slip of leading super-partial dislocations, is undoubtedly more reasonable than the previous simple model. In the simple separated model, the cross-slip of super-partial dislocations is likely to be underestimated owing to a lack of interplay between and dislocations.

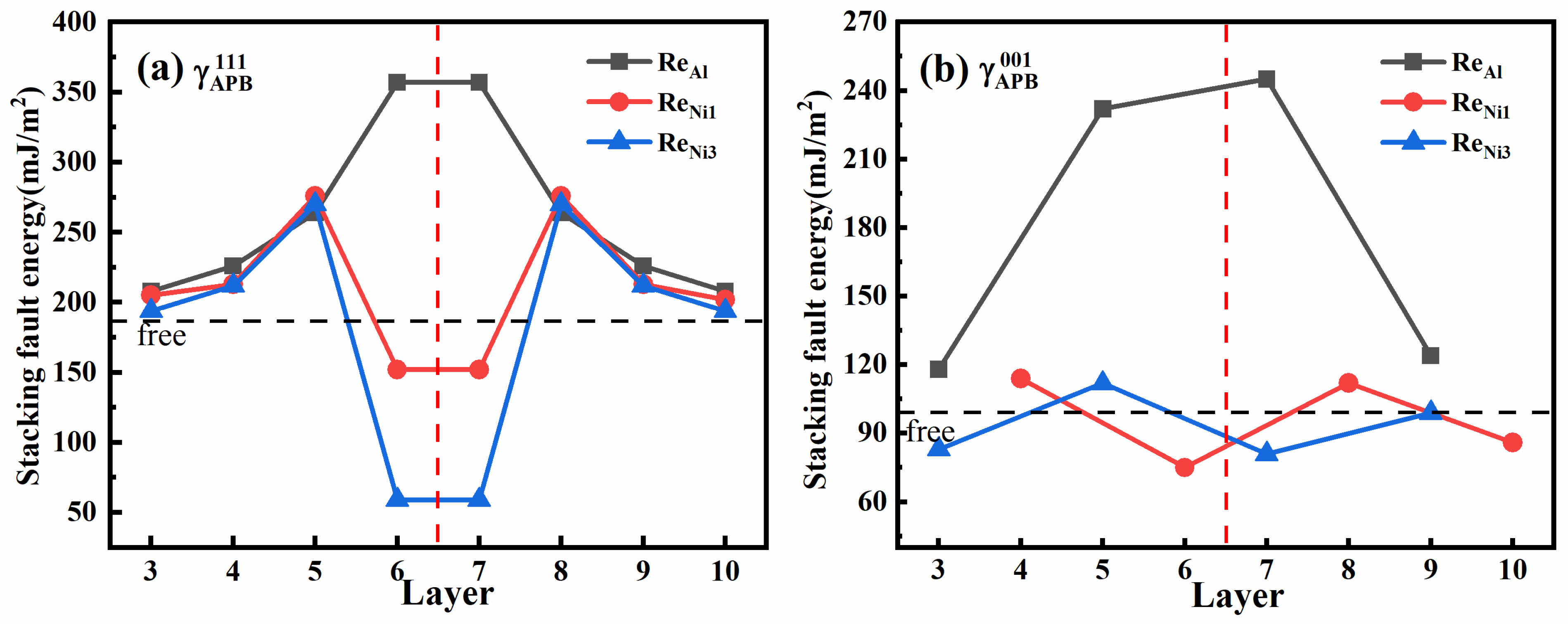

3.2. Suzuki Segregation of Re at APB(111) and APB(001)

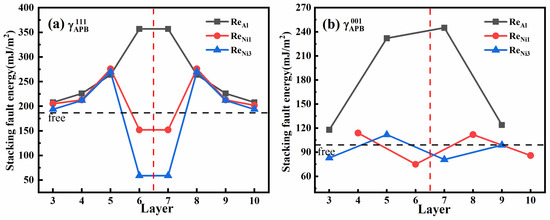

As an important strengthening element, Re mainly partitions in the γ phase, but some of them are able to enter the γ′ phase and preferentially occupy Al sublattice sites [41,42,43]. However, the question of whether Suzuki segregation occurs at stacking faults remains open. Smith et al. [44] first observed the enrichment of Re and W at superlattice extrinsic stacking fault (SESF) sites, with a depletion of Ni and Al in Ni-based SC superalloys. Later, a similar segregation of Re along superlattice intrinsic stacking fault (SISF) was discovered in CMSX-4 specimens [45,46]. But it is still unclear which sublattice site is substituted by Re at stacking faults. In order to explore the favorable site of Re in , the stacking fault energies of were calculated by a series of substitutions of Re for Ni or Al at various sublattice sites in different atomic layers. The results are illustrated in Figure 5a. Relative to the Re-free model, a low APB energy at the adjacent atom layer of in Re-addition models indicated that Suzuki segregation of Re at is energetically favorable. But, different from the preferential occupation of Re at Al sublattice sites in perfect Ni3Al crystals [47], only Ni sublattice sites were energetically permissive. The order of is < < Re-free < , and the influence of the addition of Re on is gradually weakened when the atomic layer is distant from the . These results clearly indicate that Re tends to segregate to and preferentially occupies Ni sublattice sites, especially at Ni3 sublattice sites.

Figure 5.

The variation of anti-phase boundary energies (a) and (b) with sublattice sites substituted by Re in different atomic layers. The red dotted line represents the fault plane of or .

Further, the segregation tendency and preferential sites of Re in were also investigated. The stacking fault energies of , which are dependent on the substitution of Re for Ni or Al in different atomic layers, are shown in Figure 5b. Similar to the segregation of Re in , Figure 5b shows that the in the adjacent atomic layer of in the Re-addition model was lower than that in the Re-free model, indicating that Suzuki segregation of Re existed also in , and that only the substitution of Re for Ni was energetically permissive. The optimal segregation sites were merely Ni1 sublattice sites, rather than Ni3 sublattice sites.

In view of the fact that the partial replacement of Re by W scarcely influence the mechanical properties of nickel-based SC superalloys [14,48], the segregation tendency and preferential sites of W at and were also investigated. A similar Suzuki segregation of W to Re occurred in and . For , the preferential site of W-segregation was as same as that of Re-segregation, but its optimal site changed to Ni3 sublattice sites in .

3.3. Re-Effects at Preferential Al Sublattice Sites

Previous investigations [13,26] have demonstrated that the addition of Re at preferential Al sublattice sites promotes the cross-slip of leading super-partial dislocations. As a revisiting, the effects of the addition of Re at preferential Al sublattice sites on the cross-slip of super-partial dislocations were studied firstly by previous simple models. The results are illustrated in Figure 4b and further tabulated in Table 2. In Figure 4b and Table 2, one can see that APB energy and and their ratio in the model increased by mJ/m2, mJ/m2 and 0.07 relative to those values for a perfect Ni3Al crystal, respectively. This upraised indicates the leading super-partial dislocations cross-slips from to planes to be accelerated [17], although their nucleation may have been restricted owing to an increase of mJ/m2 in . In this case, the K-W lock is easier to be formed. Consequently, the addition of Re at preferential Al sublattice sites are profitable for the improvement of creep strength of the L12-γ′ phase [13].

Table 2.

APB energies , unstable stacking fault energies and APB anisotropy ratios = in Re-addition and W-addition models.

Further, the above-mentioned Re-effect at preferential Al sublattice sites was also investigated using a hybrid model, as shown in Figure 3c. The result is illustrated in Figure 4b and further listed in Table 2. From Table 2, one can see that the and in the model dropped by mJ/m2 and mJ/m2, respectively, relative to those values for the perfect Ni3Al crystal, and the increased by 1.1, indicating that the addition of Re at preferential Al sublattice sites is indeed beneficial for the cross-slip of leading super-partial dislocations. Compared with the values obtained using simple models, the and decreased by mJ/m2 and mJ/m2, respectively, and the value increased to 3.38 from 1.98, which indicates that the existence of can facilitate the formation of K-W locks. Since an interplay between anti-phase boundary and point defect was taken into account in the hybrid model, it is speculated the present results should be more accurate and reasonable for the assessment of cross-slips of super-partial dislocations in the γ′ phase at high temperature.

3.4. Effect of Re-Segregation on the Cross-Slip of Dislocations

As confirmed in Section 3.2, a Suzuki segregation of Re at and took place along with the cross-slip of leading super-partial dislocations. In order to investigate the influence of Re-segregation on the cross-slips of another super-partial dislocation on the adjacent plane of previous slipping planes, several extra generalized planar fault energy curves were investigated on the basis of the optimal substitution of Re for Ni at and . In the simple models, Figure 4b and Table 2 show that for Re-segregation at Ni sublattice sites from its preferential Al sublattice sites the dropped by mJ/m2 and mJ/m2 in the and models, respectively, leading to a reduction in to 0.73 and 1.53 from 1.98, respectively. Since Re preferentially segregates to Ni3 sublattice sites in , a much smaller than in the model revealed that the Re-segregation in was undoubtedly harmful for the cross-slip of new super-partial dislocations. However, it was noticed that relative to the preferential substitution of Re for Al, Re-segregation in caused to be lowered, resulting in an increase in the in and models by 1.08 and 0.82, respectively. In this case, an upraised seemed to imply that Re-segregation in was favorable for the thickening of and the formation of more K-W locks.

Further, the effects of Re-segregation in and on the cross-slip of new super-partial dislocations were also investigated using a reconstructed hybrid model. Compared with the simple models, Table 2 shows the decreases in by mJ/m2 and mJ/m2, respectively, corresponding to Re-segregation at Ni3 sublattice sites in and at Ni1 sublattice sites in . As a result, a slight increase in from 0.52 to 0.59 in the model and an obvious elevation from 3.06 to 4.67 in the model was observed. These results clearly indicate that an interplay between point defect and anti-phase boundary may change the cross-slip rate of super-partial dislocations. In the case of the former, a new K-W lock could not be formed, whereas more K-W locks would be generated in the latter. As for the W-segregation, a similar impact of Re-segregation on the cross-slip of super-partial dislocations was observed. That is, different from the deleterious effect of Re-segregation on , W-segregation at was shown to promote the formation of K-W locks on new adjacent planes.

4. Conclusions

By means of lattice transition, a hybrid surface slab model including was reconstructed to assess the cross-slip of super-partial dislocations in the γ′-Ni3Al phase, and the impact of the addition of Re on the dislocation slipping mediated creep of the γ′-Ni3Al phase at high temperature was revisited. We demonstrated that the preferential substitution of Re at Al sublattice sites is indeed favorable for cross-slips of super-partial dislocations. In the hybrid model, it was revealed that the cross-slip rate could be accelerated by preexisting . A detailed calculation of stacking fault energies demonstrated that an obvious Suzuki segregation of Re existed in and and Re preferentially occupied Ni sublattice sites. In this case, Re-segregation in was found to be harmful for the cross-slip of new super-partial dislocations, whereas Re-segregation at promoted the formation of more K-W dislocation locks, leading to the creep resistance of the γ′ phase to be improved. Moreover, a similar impact on the creep resistance of the γ′-Ni3Al phase at high temperature following Re-segregation was observed in the case of W-segregation in and .

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.P.; methodology, Z.K., J.L. and P.P.; validation, J.L.; investigation, Z.K., J.L. and Y.X.; data curation, Z.K. and J.L.; writing—original draft preparation, Z.K.; writing—review and editing, J.L., Y.X. and P.P.; supervision, P.P.; funding acquisition, P.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, grant number [52071136].

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Long, H.; Mao, S.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, Z. Han, Microstructural and compositional design of Ni-based single crystalline superalloys―A review. J. Alloys Compd. 2018, 743, 203–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, W.; Zhao, X.; Yue, L.; Zhang, Z. A review of composition evolution in Ni-based single crystal superalloys. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2020, 44, 76–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, K.; Lu, H.; Gu, J. Atomistic simulations of the nanoindentation-induced incipient plasticity in Ni3Al crystal. Comput. Mater. Sci. 2016, 115, 214–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirsch, P. A model of the anomalous yield stress for (111) slip in L12 alloys. Prog. Mater. Sci. 1992, 36, 63–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Mao, Z.; Noebe, R.D.; Seidman, D.N. The effects of refractory elements on Ni-excesses and Ni-depletions at γ (fcc)/γ′(L12) interfaces in model Ni-based superalloys: Atom-probe tomographic experiments and first-principles calculations. Acta Mater. 2016, 121, 288–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.G.; Wang, C.Y.; Yu, T. Effect of Re on dislocation nucleation from crack tip in Ni by atomistic simulation. Comput. Mater. Sci. 2015, 97, 127–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Wang, C.; Yu, T. Effects of Re, W and Co on dislocation nucleation at the crack tip in the γ-phase of Ni-based single-crystal superalloys by atomistic simulation. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2019, 6, 190441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, R.; Yin, Q.; Wang, J.; Mao, Q.; Zhang, X.; Wen, Z. Effect of Re on mechanical properties of single crystal Ni-based superalloys: Insights from first-principle and molecular dynamics. J. Alloys Compd. 2021, 862, 158643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Makineni, S.K.; Liebscher, C.H.; Dehm, G.; Mianroodi, J.R.; Shanthraj, P.; Svendsen, B.; Bürger, D.; Eggeler, G.; Raabe, D. Unveiling the Re effect in Ni-based single crystal superalloys. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Jin, T.; Liu, J.; Sun, X.; Guan, H.; Hu, Z. Role of Re and Co on microstructures and γ′ coarsening in single crystal superalloys. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2008, 479, 148–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, T.; Wang, C.Y.; Gan, Y. Effect of Re in γ phase, γ′ phase and γ/γ′ interface of Ni-based single-crystal superalloys. Acta materialia 2010, 58, 2045–2055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, J.; Withey, P.A. Precipitation of topologically closed packed phases during the heat-treatment of Rhenium containing single crystal Ni-based superalloys. Crystals 2023, 13, 519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; XU, Y.L.; Ping, P.; Chen, J.H. Impact of replacement of Re by W on dislocation slip mediated creeps of γ′-Ni3Al phases. Trans. Nonferrous Met. Soc. China 2021, 31, 2013–2023. [Google Scholar]

- Gong, W.; Zhao, W.; Miao, N.; Zhou, J.; Sun, Z.; Li, S.; Gong, S. Strengthening effects of alloying elements W and Re on Ni3Al: A first-principles study. Comput. Mater. Sci. 2018, 144, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang-Koh, Y. Understanding the yield behaviour of L12-ordered alloys. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2017, 33, 934–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Tian, S.; Tian, N.; Zhu, X.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, S. Stacking fault energy and creep mechanism of a single-crystal nickel-based superalloy. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2023, 39, 1393–1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodaran, M.; Ettefagh, A.H.; Guo, S.; Khonsari, M.; Meng, W.; Shamsaei, N.; Shao, S. Effect of alloying elements on the γ′ antiphase boundary energy in Ni-base superalloys. Intermetallics 2020, 117, 106670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westbrook, J. Temperature dependence of the hardness of secondary phases common in turbine bucket alloys. JOM 1957, 9, 898–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kear, B.; Wilsdorf, H. Dislocation configurations in plastically deformed polycrystalline Cu3Au alloys. Trans Met. Soc. AIME 1962, 224, 382–386. [Google Scholar]

- Jing, L.; Li, Q.; Cui, J.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Yang, T.; Zhao, Y. Segregation-assisted yield anomaly in a Co-rich chemically complex intermetallic alloy at high temperatures. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2024, 223, 163–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, S.; Zhao, X.; Xia, W.; Fan, Y.; Qiao, L.; Cheng, Y.; Liu, H.; Yue, Q.; Gu, Y.; Zhang, Z. Effect of temperature on the tensile deformation mechanisms of a fourth nickel-based single crystal superalloys. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2024, 30, 6254–6264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parsa, A.B.; Sirrenberg, M.; Bürger, D.; Mills, M.J.; Dlouhy, A.; Eggeler, G. Yield stress anomaly and creep of single crystal Ni-base superalloys–Role of particle size. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2024, 899, 146403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, C.; Kumar, P. Analyzing dynamic strain aging and yield strength anomaly in IN740H, a nickel-based superalloy comprising low volume fraction of γ′. Materialia 2024, 33, 102028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paidar, V.; Pope, D.; Vitek, V. A theory of the anomalous yield behavior in L12 ordered alloys. Acta Metall. 1984, 32, 435–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, M. On the theory of anomalous yield behavior of Ni3Al-Effect of elastic anisotropy. Scr. Metall. 1986, 20, 915–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.X.; Wang, C.Y. Effect of alloying element on dislocation cross-slip in γ′-Ni3Al: A first-principles study. Philos. Mag. 2012, 92, 4028–4039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Wang, C.; Yan, P.; Yu, T. The effect of Ta, W, and Re additions on the tensile-deformation behavior of model Ni-based single-crystal superalloys at intermediate temperature. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2022, 850, 143594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Meng, J.; Liu, J.; Zou, M.; Zhang, H.; Sun, X.; Zhou, Y. Influences of Re on low-cycle fatigue behaviors of single crystal superalloys at intermediate temperature. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2019, 35, 1917–1924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, G.; Tian, S.; Shu, D.; Tian, N.; Yan, H.; Wang, G.; Liu, L. Influence of Ru on creep behaviour and concentration distribution of Re-containing Ni-based single crystal superalloy at high temperature. Mater. Res. Express 2020, 7, 066507. [Google Scholar]

- Roundy, D.; Krenn, C.; Cohen, M.L.; Morris, J. Ideal shear strengths of fcc aluminum and copper. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1999, 82, 2713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogata, S.; Li, J.; Yip, S. Ideal pure shear strength of aluminum and copper. Science 2002, 298, 807–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kresse, G.; Hafner, J. Ab initio molecular dynamics for liquid metals. Phys. Rev. B 1993, 47, 558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kresse, G.; Joubert, D. From ultrasoft pseudopotentials to the projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 1999, 59, 1758–1775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Futamura, Y.; Yano, T.; Imakura, A.; Sakurai, T. A real-valued block conjugate gradient type method for solving complex symmetric linear systems with multiple right-hand sides. Appl. Math. 2017, 62, 333–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perdew, J.P.; Burke, K.; Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1996, 77, 3865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rice, J.R. Dislocation nucleation from a crack tip: An analysis based on the Peierls concept. J. Mech. Phys. Solids 1992, 40, 239–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, S.L.; Shimanek, J.; Qin, S.; Wang, Y.; Beese, A.M.; Liu, Z.K. Unveiling dislocation characteristics in Ni3Al from stacking fault energy and ideal strength: A first-principles study via pure alias shear deformation. Phys. Rev. B 2020, 101, 024102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruml, T.; Conforto, E.; Piccolo, B.L.; Caillard, D.; Martin, J. From dislocation cores to strength and work-hardening: A study of binary Ni3Al. Acta Mater. 2002, 50, 5091–5101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manga, V.R.; Shang, S.L.; Wang, W.Y.; Wang, Y.; Liang, J.; Crespi, V.H.; Liu, Z.K. Anomalous phonon stiffening associated with the (111) antiphase boundary in L12 Ni3Al. Acta Mater. 2015, 82, 287–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karnthaler, H.; Mühlbacher, E.T.; Rentenberger, C. The influence of the fault energies on the anomalous mechanical behaviour of Ni3Al alloys. Acta Mater. 1996, 44, 547–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagot, P.A.; Silk, O.; Douglas, J.; Pedrazzini, S.; Crudden, D.; Martin, T.; Hardy, M.; Moody, M.P.; Reed, R.C. An Atom Probe Tomography study of site preference and partitioning in a nickel-based superalloy. Acta Mater. 2017, 125, 156–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Liu, C.; Liu, W.; Zhang, X.; Yan, P.; Wang, C. Investigation of the elemental partitioning behaviour and site preference in ternary model nickel-based superalloys by atom probe tomography and first-principles calculations. Philos. Mag. 2016, 96, 2204–2218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Zhang, L.; Li, J.; Xiao, X.; Cao, X.; Jia, G.; Shen, Z. Relationship between Ti/Al ratio and stress-rupture properties in nickel-based superalloy. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2012, 544, 48–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, T.M.; Esser, B.D.; Antolin, N.; Viswanathan, G.B.; Hanlon, T.; Wessman, A.; Mourer, D.; Windl, W.; McComb, D.W.; Mills, M.J. Segregation and η phase formation along stacking faults during creep at intermediate temperatures in a Ni-based superalloy. Acta Mater. 2015, 100, 19–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viswanathan, G.B.; Shi, R.; Genc, A.; Vorontsov, V.A.; Kovarik, L.; Rae, C.M.F.; Mills, M.J. Segregation at stacking faults within the γ′ phase of two Ni-base superalloys following intermediate temperature creep. Scr. Mater. 2015, 94, 5–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, T.M.; Esser, B.D.; Good, B.; Hooshmand, M.; Viswanathan, G.B.; Rae, C.M.F.; Ghazisaeidi, M.; McComb, D.W.; Mills, M.J. Segregation and phase transformations along superlattice intrinsic stacking faults in Ni-based superalloys. Metall. Mater. Trans. A 2018, 49, 4186–4198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; He, S.; Yi, Z.; Peng, P. A synergistic reinforcement of Re and W for ideal shear strengths of γ′-Ni3Al phases. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 2019, 131, 34–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wöllmer, S.; Mack, T.; Glatzel, U. Influence of tungsten and rhenium concentration on creep properties of a second generation superalloy. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2001, 319, 792–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).