Abstract

Additive manufacturing (AM) offers significant potential but faces challenges in controlling rapid solidification processes due to thermal conditions. The application of magnetic fields provides a promising path to influence liquid metal behavior during solidification. Thermoelectromagnetic convection (TEMC) is one of the mechanisms by which an applied static magnetic field can induce melt flow, where thermal gradients at the solid–liquid interface generate thermoelectric currents, and in the presence of an external magnetic field induce Lorentz force that drives liquid convection, leading to enhanced heat transfer. This study investigates the impact of moderate static magnetic fields on the laser melting process of a Sn-10%wt.Pb alloy. It is found that applying a magnetic field significantly widens and deepens laser weld beads. Bead depth and width under different field strengths and orientations are measured. Numerical models are developed to calculate the TEMC current distribution and flow in the melt pool.

1. Introduction

Metal additive manufacturing (AM) is a rapidly growing industry with great potential. Already in several industries, this technology is changing the way production is organized and supply chains work. The rapid solidification process in AM is difficult to control. Although there is a wide range of different metal alloys and their applications, only a fraction of them is suitable for production using additive manufacturing methods. High thermal gradient and rapid solidification during AM can lead to defects in the microstructure, such as pores, oriented dendrite growth, and cracks [1,2,3]. These defects subsequently compromise the mechanical properties of the manufactured parts. The most common metal AM approaches are using a wire or powder as feedstock [4]. In most of these metal additive methods, the feedstock and base metal are melted using an electric arc or laser and then solidify in the desired location. The liquid metal pool exists for a very short time and typically, solidification takes place in a few milliseconds with a cooling rate of 104–106 K/s [5]. Such rapid solidification has some problems because diffusion processes cannot take place in such a short time leading to hot cracking, trapped gas, shrinkage pores, and unfavorable microstructure formation due to oriented heat flux [6,7]. Because of these problems, only certain metal alloys are suitable for additive manufacturing, while many commonly used alloys remain only machinable and castable, or the approaches to producing them with AM are not feasible yet. AM is a widely investigated area with new methods and approaches to manage the heat input methods or pretreat the materials to overcome the problems associated with the high cooling rate [8]. One of the typical examples is that the whole range of the highest-strength Al alloy series 2XXX and 7XXX are very susceptible to hot cracking during laser metallurgy and fusion welding processes. AA7075 alloy is especially prone to this problem, which has significantly limited its widespread use in AM [9,10]. AA7075 is a common high-strength aluminum widely used in automotive and aircraft industries, but it cannot be laser welded or produced with any AM methods [11]. Special alloys suitable for AM and new methods for processing existing materials using AM are being developed [12]. Several recent studies have investigated parameter optimization methods for AM of various metals, but a unified formula to evaluate the materials suitability for specific additive manufacturing methods has yet to be established and many studies are limited to empirical evaluations of the material and AM methods [13,14].

Heat and mass transfer in the liquid melt pool during solidification are important factors in determining the solidified material microstructure and properties. In AM, this process is difficult to control, because the cooling rate and thermal gradient defining the process outcome only depend on material properties [15]. The liquid metal melt pool can be affected by electromagnetic forces, created by applied magnetic and electric fields [16]. The impact of magnetic fields on liquid metal during solidification has been widely studied using directional solidification experiments, and it is shown that there are several mechanisms in which magnetic fields influence heat and mass transfer leading to modified microstructure and segregation [17,18]. An alternating magnetic field leads to grain refinement and improves the homogeneity of the composition [19]. Even the solidification interface shape can be significantly influenced by applying a magnetic field [20]. The static magnetic field has a dual impact on liquid metal solidification. Firstly, the static magnetic field introduces the damping of liquid motion perpendicular to the magnetic field lines [21]. Thermoelectric magnetohydrodynamics (TEMHD) studies the metal flow caused by the interaction between electric currents generated by the thermal gradient at the solid–liquid interface in the presence of an external magnetic field [22]. The impact of a moderate static magnetic field on the directional solidification of Al-5%wt.Cu alloy shows significant differences in grain morphology [23].

Thermoelectric magnetohydrodynamics could be particularly relevant in this case, because during AM, an extremely high thermal gradient is usually present, which leads to large thermoelectric current density and Lorentz force if a magnetic field is present [24]. TEMHD in actual AM arises from the large volume force, which is present in melt pools typically of a few hundred micrometers. Even with moderate magnetic fields, thermoelectric force can become a dominant force acting on liquid metal. Experiments with a synchrotron observation of the flow show that a modulated static magnetic field can lead to variations in the melt pool depth and width in laser AM process [25]. Direct observation methods are limited because of the fast process, small size and high temperatures. TEMHD processes have been studied in scale model experiments aimed at understanding the characteristics of the molten metal flow and using scaling analysis and low melting temperature metals to estimate the significance of TEMC in realistic AM cases [26,27]. To quantify the effect of the applied magnetic field, the segregation and microstructure in directional solidification of Sn-Pb alloys have been studied, showing that significant segregation takes place and that the main mechanism is TEMC. Using a room temperature GaInSn model, the TEMC velocity dependence on the magnetic field orientation and strength has been directly observed [28,29]. Macrosegregation and the magnetic field impact on natural convection have been studied in an AFRODITE experiment showing that even a weak magnetic field can change the heat and mass transfer and solidified microstructure, as convection prevents large, oriented grain growth [30].

2. Methodology

In this work we use a Sn-10%wt.Pb alloy to study the bead morphology changes caused by the application of a moderate static magnetic field up to 0.4 T. The Sn-10%wt.Pb alloy is a well-known material, used as a low-temperature model material to study the solidification of metallic alloys under electromagnetic fields. For many alloys, especially at high temperatures, the thermoelectric properties for metal alloys are unknown. The Seebeck coefficient is as electron transport property which changes abruptly between the solid and liquid phases at the melting temperature. For Sn-Pb alloys, thermoelectric properties have been measured in a wide temperature range for both solid and liquid states, and the differential Seebeck coefficient between the solid and liquid phases is therefore known [31]. The physical properties of Sn-10%wt.Pb used in numerical models and calculations of this work are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Physical properties of Sn-10%wt.Pb alloy at melting temperature.

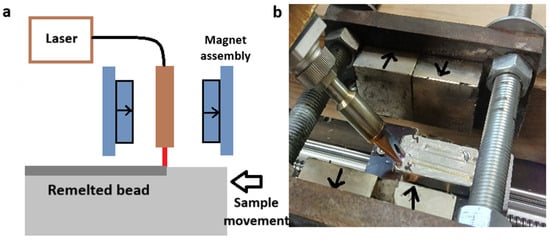

The experimental procedure of this work is performed using a Stahlwerk WCD-1500 laser (STAHLWERK, Meitingen, Germany). This handheld laser with a wavelength of 1080 nm is intended for welding and cutting metals up to 4 mm thick. The laser power can be adjusted from 0 to 1500 W, while beam width can be set between 0.5 mm and 2 mm. In this work we use a beam width of 1 mm and scan velocities of 2 mm/s and 4 mm/s. A laser power of 250 W is used in the experiments to produce a bead with comparable depth and width. The magnetic field is created by a permanent magnet assembly. Four 50 × 50 × 25 mm magnets are placed on 20 mm thick iron plates held together by iron rods acting as a magnetic yoke (Figure 1b). The magnetic field can be changed by varying the distance between the magnets. Sn-10%wt.Pb alloy is prepared from 99.9% pure Sn and Pb and is then cast into 10 × 30 × 70 mm graphite molds. After cooling, these blocks are placed inside the experimental setup, as shown in Figure 1a. Sn-Pb block is moved with CNC-controlled linear rail, while laser and magnetic systems remain stationary. The bead was oriented along the longest edge of the block, and two beads were formed on a single block, with a 10 mm gap between them. These experiments are performed in air atmosphere since liquid tin does not oxidize too rapidly. In addition, the oxide film can also help to mitigate the Marangoni surface force effects. The melt pool is precisely located in the middle of the magnetic system. The magnetic field is measured with Hirst GM08 gaussmeter (Hirst Magnetic Instruments Ltd., Falmouth, UK). The magnetic field orientation can be changed by rotating the magnet system. In our experiments we used various magnetic field orientations, but of particular interest is the magnetic field application along the welding direction, because it is expected to create the largest heat transfer in the perpendicular direction. After the solidification samples are cut, they are polished and chemically etched with nitric acid solution to reveal the microstructure and bead shape and size. Micrographs are analyzed by measuring bead width and depth using an Olympus BM53 metallographic microscope (Olympus Corporation, Tokyo, Japan). The principal scheme and a photo of the experimental setup is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

(a) The principal scheme of the experimental setup. Magnetization direction of magnets are indicated with arrows; (b) photo of the experimental setup.

The melt pool size is 1–2 mm in this case, and it is elongated in the scanning direction roughly two times. A typical temperature gradient in this case is around 500 K/mm. The thermoelectric current density can be estimated by Ohm’s law: . We can estimate that j is around 106 A/m2. The applied magnetic field interacts with this current creating Lorentz force and molten metal flow in the melt pool. This flow contributes to the heat transfer and can change the melt pool size and solidified microstructure.

3. Results and Analysis

3.1. Experimental Results

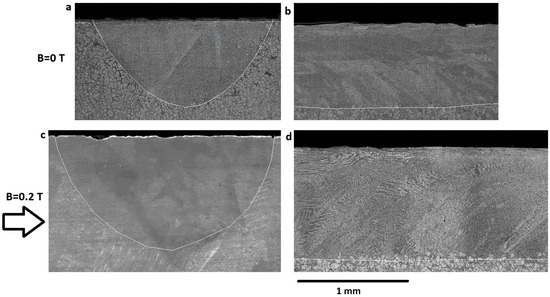

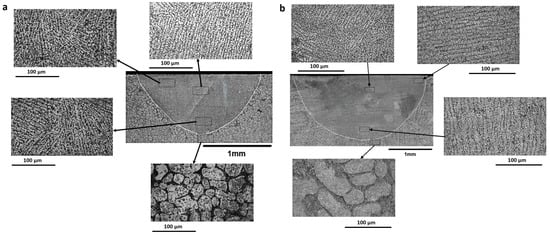

Solidified beads perpendicular to the cross section of the samples without a magnetic field were compared with those under a 0.2 T magnetic field applied perpendicular to the welding direction and are shown in Figure 2. Note that the scale for all figures is the same. Without a magnetic field, the bead is smaller (width = 1.58 mm, depth = 0.79 mm). With the applied static magnetic field perpendicular to the weld direction, the bead size increases (width = 1.92 mm, depth = 0.91 mm). The cross sections from side (Figure 2b,d) show that the depth of the bead is relatively constant.

Figure 2.

Bead morphology of laser-welded Sn-10%wt.Pb. Velocity is 2 mm/s, laser beam width is 1 mm: (a,b) perpendicular and longitudinal cross sections without magnetic field; (c,d) perpendicular and longitudinal cross sections with B = 0.2 T magnetic field perpendicular to welding direction.

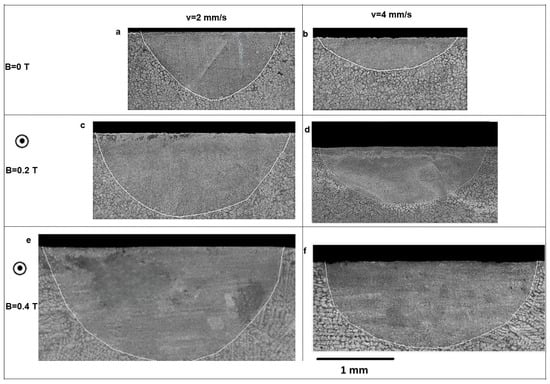

Experimental results with an applied magnetic field along the scanning direction are shown in Figure 3. If the laser moves slower, the bead is deeper and wider. Results show that, at both velocities, increasing the magnetic field leads to an increase in the bead’s width and depth. With a laser speed of 4 mm/s, the bead is shallower because of smaller total heat deposited in the bead.

Figure 3.

Bead morphology of laser-welded Sn-10%wt.Pb. Laser width is 1 mm: (a,b) perpendicular cross sections with v = 2 mm/s and 4 mm/s without a magnetic field; (c,d) perpendicular cross sections with v = 2 mm/s and 4 mm/s with B = 0.2 T; (e,f) perpendicular cross sections with v = 2 mm/s and 4 mm/s with B = 0.4 T.

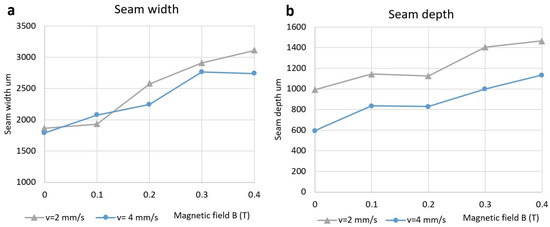

The bead width and depth for different magnetic field strengths with the magnetic field applied along the scanning direction are shown in Figure 4. Results show that the size of the bead increases with the magnetic field. The increase can be attributed to the additional molten metal flow created by the applied magnetic field. The depth and the width increase by about 60% between 0 and 0.4 T, meaning that the melt pool volume has increased by 2–3 times.

Figure 4.

The dependence of the bead size on the strength of the applied magnetic field along the welding direction. Bead width (a) and depth (b).

The microstructure of the Sn-10%wt.Pb alloy is analyzed at the various places in the bead. A comparison of the cases without a magnetic field and with a 0.4 T magnetic field is shown in Figure 5. The bead consists of a much finer grain structure than the base metal. The grain size is primarily defined by the cooling rate, but it is also influenced by the flow of the molten metal. From the results, we may find the grain sizes by using the Intercept Procedure [34] for both the diagonal and vertical and horizontal lines through the center. The initial material has a grain size of approximately 40 µm. After remelting with a laser, the average grain size of the bead is 6.8 µm in the absence of a magnetic field and 8.9 µm under a 0.4 T field. The fine grain structure indicates that the solidification occurs more rapidly inside the bead. It is visible in micrographs that the grains are oriented outward along the main heat flow.

Figure 5.

Comparison of beads and microstructure of Sn-10%wt.Pb. Velocity v = 2 mm/s, laser width d = 1 mm, power p = 250 W: (a) B = 0 (a,b) B = 0.4 T along the scan direction.

3.2. Numerical Model

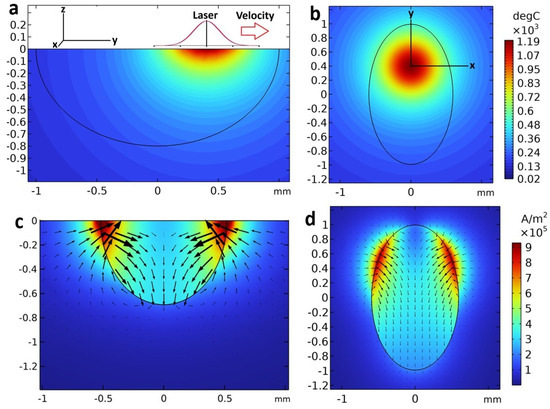

Experimental results are supported by numerical models developed in COMSOL Multiphysics 6.0. In this case, stationary models are used, including temperature, electromagnetism and fluid flow modules. The whole experimental specimen (10 × 30 × 70 mm) is implemented in the numerical model plus the order of magnitude bigger air domain around it. The melt pool is defined as a liquid phase with a typical size of 2 mm in length, 1.2 mm in width, and 0.8 mm in depth. The liquid phase mesh contains around 70,000 tetrahedral elements. Based on sample temperature measurements, approximately 60% of the laser power is reflected. The numerical model calculates the temperature distribution assuming that 40% of the laser power is absorbed by the sample. The laser heating is introduced in the model as Gaussian-shaped inward heat flux. Numerical models consider the thermal radiation from the surface, which turns out to be important and limits the maximum temperature at the middle of the laser spot. The calculated temperature distribution is shown in Figure 6a,b. Numerical models show that a temperature of 1200 °C is reached in the laser spot but it drops rapidly with the distance. Following the temperature distribution analysis, an electromagnetism model is applied to calculate the thermoelectric current distribution. A thermoelectric voltage is generated at the interface in the case when there is a thermal gradient component along it according to the following formula V = ΔS·ΔT. The voltage drop causes current flow according to the Ohm’s law. Figure 6c,d shows the thermoelectric current distribution. As can be seen, the thermoelectric current reaches its maximum value of 1 A/mm2 near the solid/liquid interface, where the temperature gradient is highest, while the average current in the liquid domain along the xz plane is 0.3 A/mm2.

Figure 6.

Numerical simulation results: (a,b) temperature field, (c,d) thermoelectric current distribution.

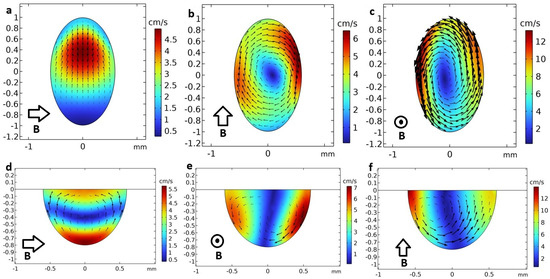

The fluid dynamics model considers the viscous force as well as the forces caused by the applied magnetic field: the thermoelectric force and the MHD damping force. The thermoelectric force is calculated as a cross product of current density and the applied magnetic field, while MHD damping force is σB·u × B. The flow in the melt pool is calculated for three orientations of magnetic field orientations where B = 0.2 T. Results are shown in Figure 7. Results show that velocity up to 12 cm/s can be reached in the given melt pool due to TEMC. Different magnetic field orientations create rather different flow patterns, which indicates that by choosing the magnetic field direction and magnitude, it is possible to alter the fluid flow in the melt pool. The magnetic field along the z axis mainly creates rotation, while the magnetic field along the y axis creates slightly larger flow velocity than if B is along the x axis. This agrees well with the analysis of the TEMC flows caused by various field orientations in model experiment [27]. In this work it is shown that this approach of numerical simulation agrees well with experimental surface flow measurements.

Figure 7.

Thermoelectromagnetic convection velocities with 0.2 T magnetic fields of various orientations. Cross section of xy and xz planes: (a,d) Bx, (b,e) By, (c,f) Bz.

3.3. Analysis

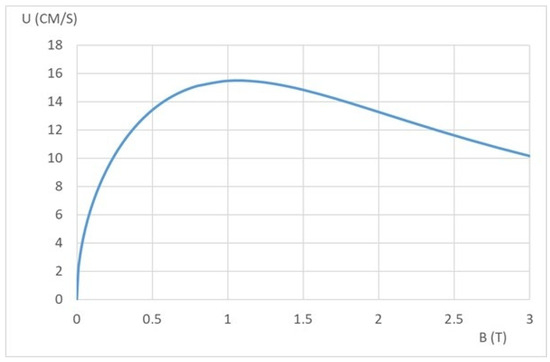

Numerical models give an indication of TEMC velocity in the melt pool. In several studies it is demonstrated that as the magnetic field increases, both forces associated with it also increase. The thermoelectric force term is proportional to B, while the MHD damping term is proportional to B2. The thermoelectric force creates a flow, while damping always acts opposite to the velocity. This means that as the magnetic field increases, the motion of the melt is slowed down. It is shown that in each case, there exists a critical magnetic field at which the maximum velocity is reached. It is shown that in each case, there are critical magnetic fields where the maximum velocity is reached [23,27]. The velocity dependence on the magnetic field can be determined by solving the Navier–Stokes equation (Equation (1)). The current flow is described by Ohms law (Equation (2)). The velocity’s order of magnitude of velocity can be estimated by combining these equations and solving the simplified Navier–Stokes equation (Equation (3)). For a given set of parameters, the results are shown in Figure 8. It should be noted that the exact force distribution and aspect ratio of the geometry are ignored in this approach. Therefore, the results provide only an indication of the velocity magnitude, but the dependence on the magnetic field is captured quite accurately. As can be seen, that velocity in the region from 0 to 0.4 T increases, reaching more than 10 cm/s velocity.

Figure 8.

Order of magnitude velocity estimate for TEMC velocity in Sn = 10%wt.Pb melt pool.

The ratio between the electromagnetic and inertial forces is described by the Stuart number N (Equation (4)). To characterize the significance of the thermoelectromagnetic term, we may find the ratio Te (Equation (5)) between the thermoelectric term and the MHD damping terms in a similar way by dividing the force densities from Equation (3).

Calculating these parameters using B = 0.4 T, L = 2 mm, u = 0.1 m/s, we achieve N = 1 and Te = 10. These numbers indicate that TEMC, inertia and MHD damping are forces with comparable magnitudes and can become dominant under certain conditions or if some of the parameters are changed.

The experimental laser remelting results of this work are summarized in Figure 2, Figure 3 and Figure 5. The bead width and depth increase under an applied magnetic field is summarized in Figure 4, showing that the bead size increases when a magnetic field is applied, for the laser remelting speeds of 2 mm/s and 4 mm/s. The applied magnetic field creates a melt flow which increases with increasing magnetic field strength within the given range; thus, the bead size increase could be the consequence of TEMC. Convective heat transfer speeds up the heat transport from the hot laser spot; thus, the heat is spread more uniformly across the bead and melting a larger amount of material, resulting in an increased bead size.

4. Conclusions

This study investigates the effect of a static magnetic field on the laser-melted section of a Sn-Pb alloy. This work demonstrates that the thermoelectric magnetohydrodynamics effect can generate a significant liquid metal flow in the melt pool of Sn-10%wt.Pb alloy during laser scanning. A moderate magnetic field of 0.1–0.4 T can induce a liquid phase convection, which enhances the heat transfer from the laser hot spot more evenly across the molten domain. As a result, the bead widens and deepens. Applying a 0.4 T magnetic field along the laser scanning direction increased the bead’s linear size by over 60%. Numerical models indicate that TEMC can be the main mechanism responsible for increased forced convection in the melt pool under an external magnetic field.

These results provide a basis for predicting the potential impact of magnetic fields on various laser metal additive manufacturing processes where a melt pool forms and the Seebeck coefficient differs between the solid and liquid phases. The application of a static magnetic field can potentially be used in metal additive manufacturing as a tool for better solidification control, enabling the modification of the molten zone’s size. The creation of a heat flux asymmetry compensates for the oriented heat flow, which may occur due to the asymmetric thermal conditions when the melt pool is surrounded by solid metal from one side and air from the other. In this case, the field needs to be changed depending on the melt pool location; thus, an electromagnet would be a better solution than permanent magnet assembly. Numerical models and an analytical order of magnitude estimate indicate that with given material and set of parameters, the maximum flow intensity is reached at B = 0.1 T, but a 0.4 T field is sufficient to reach more than 60% of the maximum TEMC velocity.

Author Contributions

This research is performed in the University of Latvia as cooperation between Institute of Physics and Institute of Numerical Modeling. A.K. is a student at the University of Latvia, VF is student at Greenwich University. Conceptualization, I.K.; methodology, I.K. and A.K.; numerical simulations, V.F. and V.D.; Experimental work and image processing, A.K.; formal analysis, I.K.; original draft preparation, I.K.; supervision and project administration, I.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors are grateful for the financial support to ERDF project No. 1.1.1.3/1/24/A/116 “Magnetohydrodynamics methods for improved metal additive manufacturing”. Work is supported by the University of Latvia development program with big impact project ‘‘Improved control of metal 3D printing by thermoelectric magnetohydrodynamics’’.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Pai, K.R.; Vijayan, V.; Prabhu, K.N. Recent challenges and advances in metal additive manufacturing: A review. Mater. Today Proc. 2024, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuncer, N.; Bose, A. Solid-State Metal Additive Manufacturing: A Review. JOM 2020, 72, 3090–3111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vafadar, A.; Guzzomi, F.; Rassau, A.; Hayward, K. Advances in Metal Additive Manufacturing: A Review of Common Processes, Industrial Applications, and Current Challenges. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brueckner, F.; Riede, M.; Marquardt, F.; Willner, R.; Seidel, A.; Thieme, S.; Leyens, C.; Beyer, E. Process characteristics in high-precision laser metal deposition using wire and powder. J. Laser Appl. 2017, 29, 022301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.; Mullin, K.M.; Kumar, V.; Wander, O.; Pollock, T.M.; Zhu, Y. Resolving thermal gradients and solidification velocities during laser melting of a refractory alloy. Addit. Manuf. 2025, 105, 104750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, N.; Lei, Z.; Hu, K.; Yu, X.; Li, P.; Bi, J.; Wu, S.; Chen, Y. Hot cracking behavior and mechanism of a third-generation Ni-based single-crystal superalloy during directed energy deposition. Addit. Manuf. 2020, 34, 101228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Lei, Z.; Li, B.; Liang, J.; Chen, Y. Hot cracking evolution and formation mechanism in 2195 Al-Li alloy printed by laser powder bed fusion. Addit. Manuf. 2022, 54, 102762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biserova-Tahchieva, A.; Biezma-Moraleda, M.V.; Llorca-Isern, N.; Gonzalez-Lavin, J.; Linhardt, P. Additive Manufacturing Processes in Selected Corrosion Resistant Materials: A State of Knowledge Review. Materials 2023, 16, 1893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, J.; Yahata, B.; Hundley, J.; Mayer, J.A.; Schaedler, T.A.; Pollock, T.M. 3D printing of high-strength aluminium alloys. Nature 2017, 549, 365–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboulkhair, N.; Simonelli, M.; Parry, L.; Ashcroft, I.; Tuck, C.; Hague, R. 3D printing of Aluminium alloys: Additive Manufacturing of Aluminium alloys using selective laser melting. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2019, 106, 100578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Retraint, D.; Xue, H.; Gao, T.; Sun, Z. Fatigue properties and cracking mechanisms of a 7075 aluminum alloy under axial and torsional loadings. Procedia Struct. Integr. 2019, 19, 637–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murugan, P.D.; Vijayananth, S.; Natarajan, M.P.; Jayabalakrishnan, D.; Arul, K.; Jayaseelan, V.; Elanchezhian, J. A current state of metal additive manufacturing methods: A review. Mater. Today Proc. 2022, 59 Pt 2, 1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandyopadhyay, A.; Zhang, Y.; Bose, S. Recent developments in metal additive manufacturing. Curr. Opin. Chem. Eng. 2020, 28, 96–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, S.; Liu, Y.; Siddique, Z.; Ghamarian, I. Metal additive manufacturing: Principles and applications. J. Manuf. Process. 2024, 131, 1179–1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Guo, W.; Li, L. Numerical modelling of heat transfer, mass transport and microstructure formation in a high deposition rate laser directed energy deposition process. Addit. Manuf. 2020, 33, 101175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, C.; Xue, J.; Jia, Y.; Luo, S.; Huang, F.; Liu, X.; Du, Y. A review of additive manufacturing of metallic materials assisted by electromagnetic field technology. J. Manuf. Process. 2024, 131, 920–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganapathysubramanian, B.; Zabaras, N. On the control of solidification using magnetic fields and magnetic field gradients. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2005, 48, 4174–4189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Lu, Z.; Fautrelle, Y.; Gagnoud, A.; Moreau, R.; Ren, Z. Effect of a weak transverse magnetic field on the microstructure in directionally solidified peritectic alloys. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 37872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hainke, M.; Friedrich, J.; Müller, G. Numerical study on directional solidification of AlSi alloys with rotating magnetic fields under microgravity conditions. J. Mater. Sci. 2004, 39, 2011–2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thieme, N.; Keil, M.; Meier, D.; Bönisch, P.; Dadzis, K.; Pätzold, O.; Stelter, M.; Büttner, L.; Czarske, J. Directional solidification of gallium under time-dependent magnetic fields with in situ measurements of the melt flow and the solid-liquid interface. J. Cryst. Growth 2019, 522, 221–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, D.; Haley, J.C.; Dong, A.; Fautrelle, Y.; Shu, D.; Zhu, G.; Li, X.; Sun, B.; Lavernia, E.J. Lavernia. Influence of static magnetic field on microstructure and mechanical behavior of selective laser melted AlSi10Mg alloy. Mater. Des. 2019, 181, 107923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shercliff, J.A. Thermoelectric magnetohydrodynamics. J. Fluid Mech. 1979, 91, 231–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Fautrelle, Y.; Ren, Z. Influence of thermoelectric effects on the solid–liquid interface shape and cellular morphology in the mushy zone during the directional solidification of Al–Cu alloys under a magnetic field. Acta Mater. 2007, 55, 3803–3813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, B.; Kao, A.; Boller, E.; Magdysyuk, O.V.; Atwood, R.C.; Vo, N.T.; Pericleous, K.; Lee, P.D. Revealing the mechanisms by which magneto-hydrodynamics disrupts solidification microstructures. Acta Mater. 2020, 196, 200–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.; Fleming, T.G.; Rees, D.T.; Huang, Y.; Marussi, S.; Leung, C.L.A.; Atwood, R.C.; Kao, A.; Lee, P.D. Thermoelectric magnetohydrodynamic control of melt pool flow during laser directed energy deposition additive manufacturing. Addit. Manuf. 2023, 71, 103587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaldre, I.; Felcis, V. Investigation of thermoelectromagnetic effect at metal wire arc additive manufacturing. Magnetohydrodynamics 2023, 59, 357–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaldre, I.; Felcis, V.; Krastins, I.; Soar, P.; Tonry, C.; Kao, A. Model Experiment for the Investigation of Thermoelectric Magnetohydrodynamics in Metal Additive Manufacturing. JOM 2025, 77, 6038–6049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaldre, I.; Fautrelle, Y.; Etay, J.; Bojarevics, A.; Buligins, L. Influence on the macrosegregation of binary metallic alloys by thermoelectromagnetic convection and electromagnetic stirring combination. J. Cryst. Growth 2014, 402, 230–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaldre, I.; Fautrelle, Y.; Etay, J.; Bojarevics, A.; Buligins, L. Investigation of liquid phase motion generated by the thermoelectric current and magnetic field interaction. Magnetohydrodynamics 2010, 46, 317–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Hachani, L.; Fautrelle, Y.; Delannoy, Y.; Wang, E.; Wang, X.; Budenkova, O. Numerical modeling of a benchmark experiment on equiaxed solidification of a Sn–Pb alloy with electromagnetic stirring and natural convection. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2020, 151, 119414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaldre, I.; Fautrelle, Y.; Etay, J.; Bojarevics, A.; Buligins, L. Absolite thermoelectric power of Pb-Sn alloys. Mod. Phys. Lett. B 2011, 25, 731–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, D.W.G. The surface tensions of Pb, Sn, and Pb-Sn alloys. Met. Trans. 1971, 2, 3067–3071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panfilovich, K.B.; Sagadeev, V.V.; Golubeva, I.L. Thermal Radiation of Binary Alloys of Tin, Lead, and Bismuth. High Temp. 2003, 42, 720–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Standard Test Methods for Determining Average Grain Size, ASTM E112-13. 2021. Available online: https://store.astm.org/e0112-13r21.html (accessed on 27 November 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).