A Statistical-Based Model of Roll Force During Commercial Hot Rolling of Steel

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Previous Models

2.1. Models of Laboratory-Scale Experiments

2.2. Finite Element Analysis Models

2.3. Statistical Modeling and Machine Learning Approaches

2.3.1. Regression-Based Models

2.3.2. Neural Network Models

2.3.3. Advanced Machine Learning Approaches

2.4. Synthesis and Research Gap

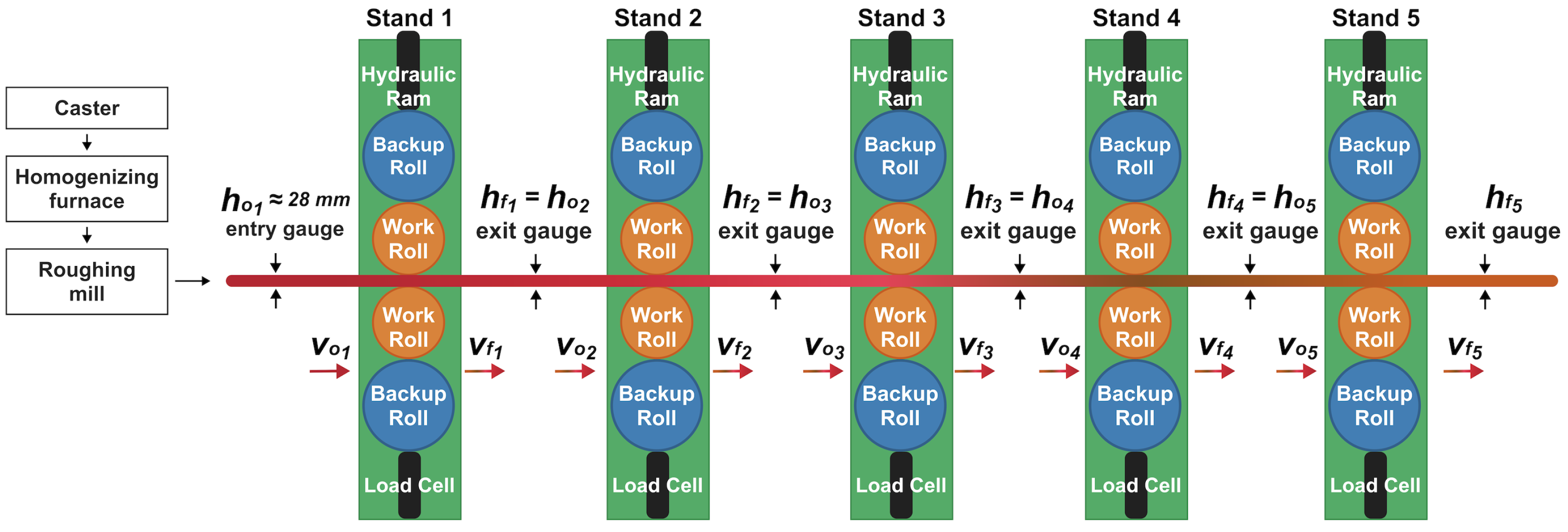

3. Hot Rolling Process and Nucor Decatur Facility

3.1. Process Description and Facility Configuration

3.2. Force Measurement and Control System

3.3. Plant Measurements

3.4. Steel Grades Investigated

4. Fundamental Rolling Model Equations

4.1. Von Karman Equations

4.2. Rolling Mechanics

4.3. Geometric and Kinematic Relationships

4.4. Material Behavior During Hot Rolling

4.5. Final Roll Force Physical Model

- Material properties through , n, and

- Temperature effects through the Arrhenius term

- Strain rate effects through

- Strain hardening through

- Geometric factors through width w and contact length ℓ

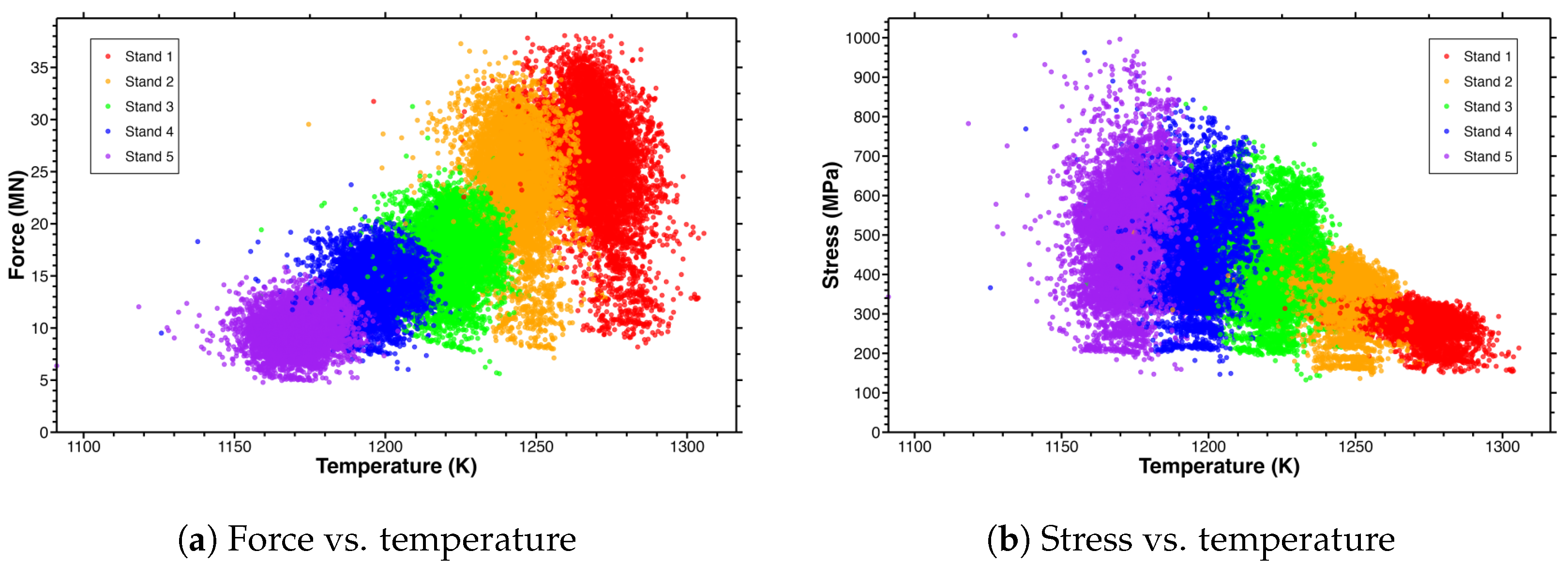

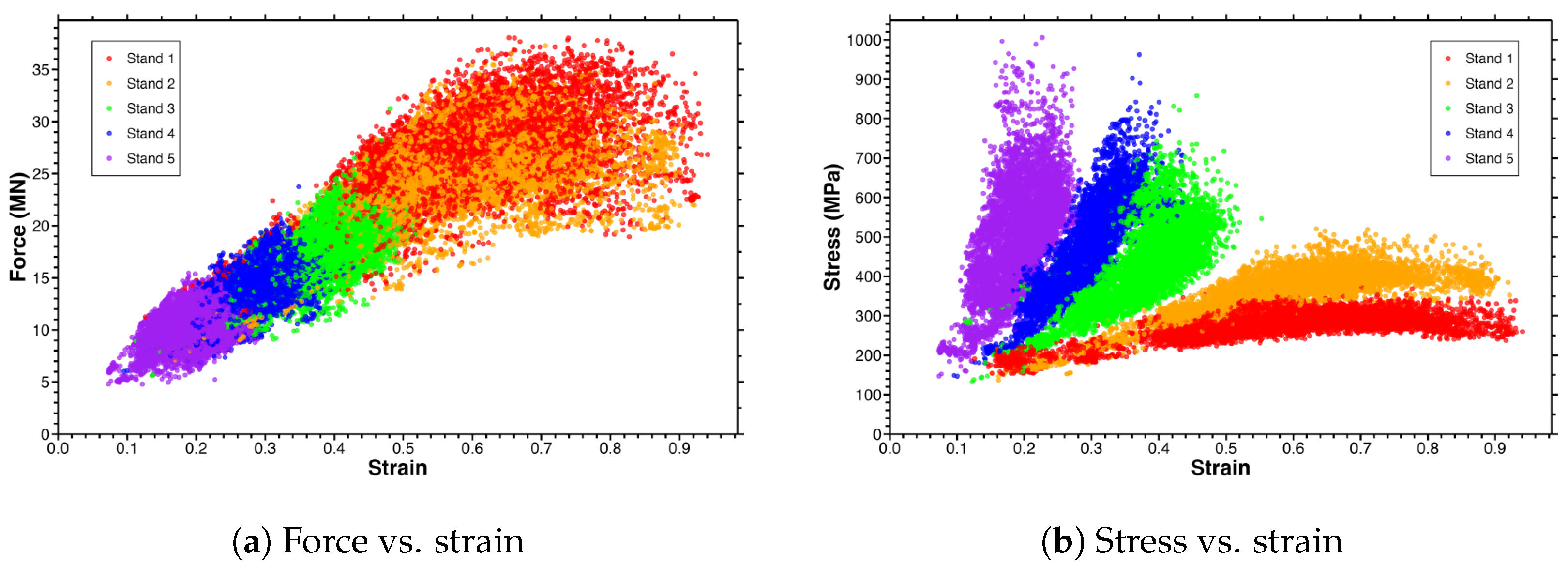

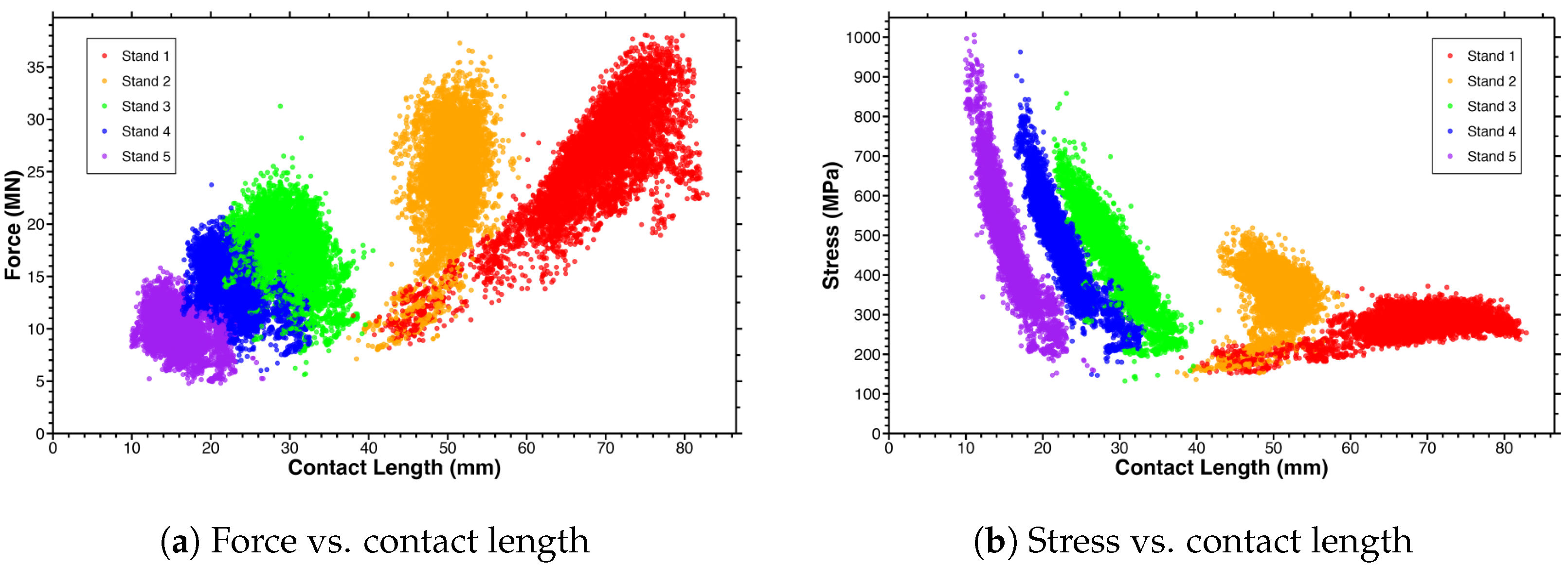

5. Visualization of Process Variable Relationships

5.1. Force and Stress vs. Temperature

5.2. Force and Stress vs. Strain

5.3. Force and Stress vs. Contact Length

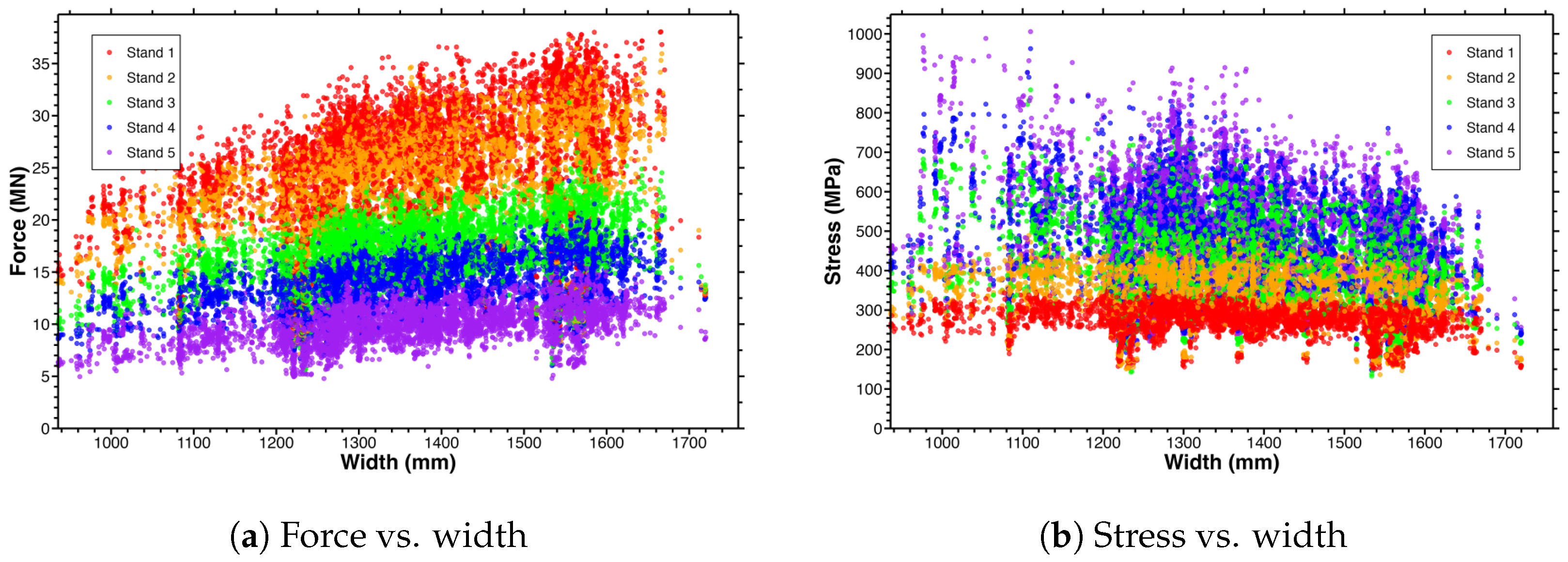

5.4. Force and Stress vs. Width

5.5. Force and Stress vs. Strain Rate

5.6. Key Insights from Visualization

6. Regression Model Formulation

7. Combined Models

7.1. Model M1: Temperature-Dependent Strain Rate Model

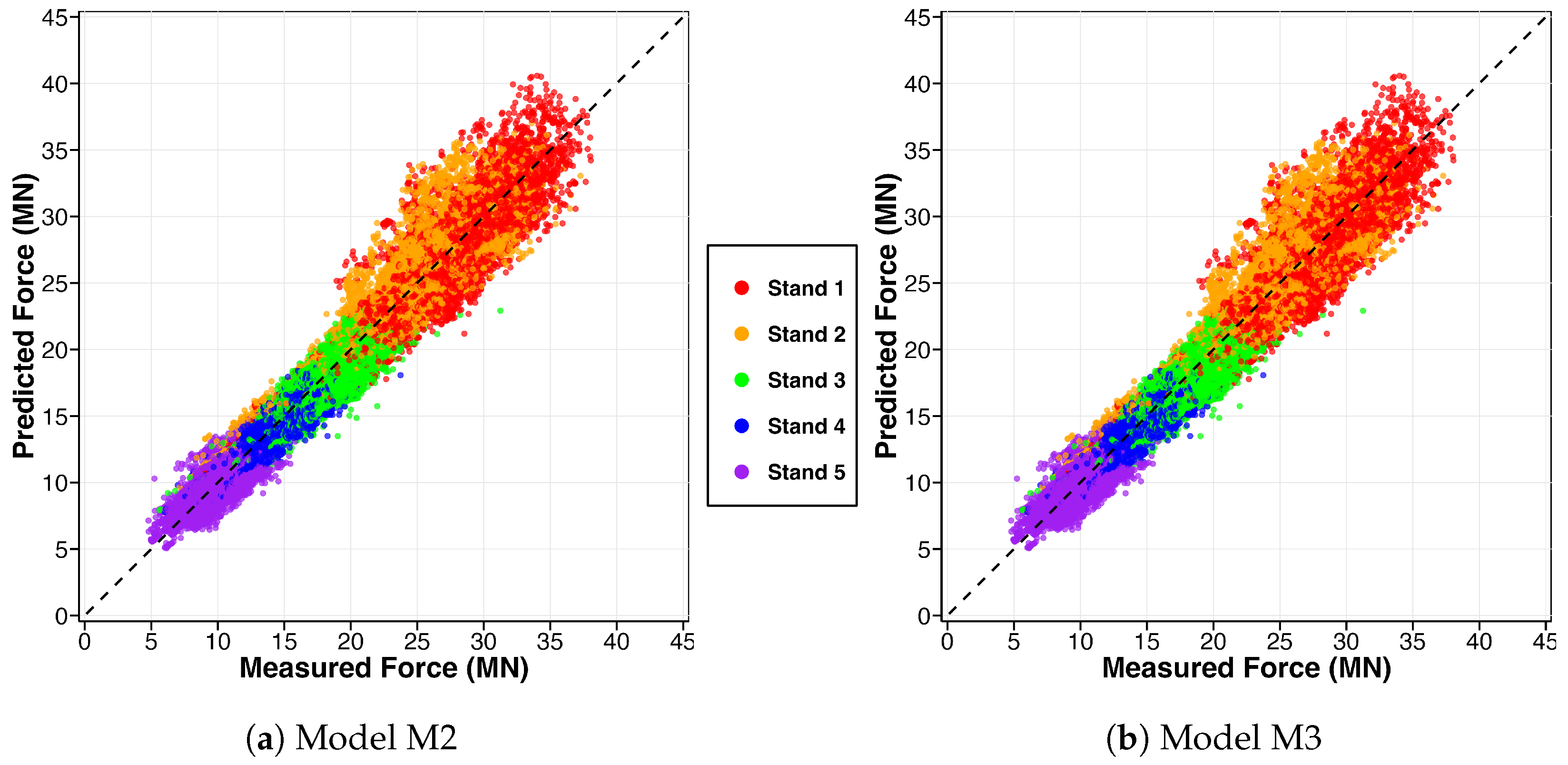

7.2. Model M2: Strain Rate Model

7.3. Model M3: Simplified Strain Rate Model

7.4. Train–Test Split Model Validation

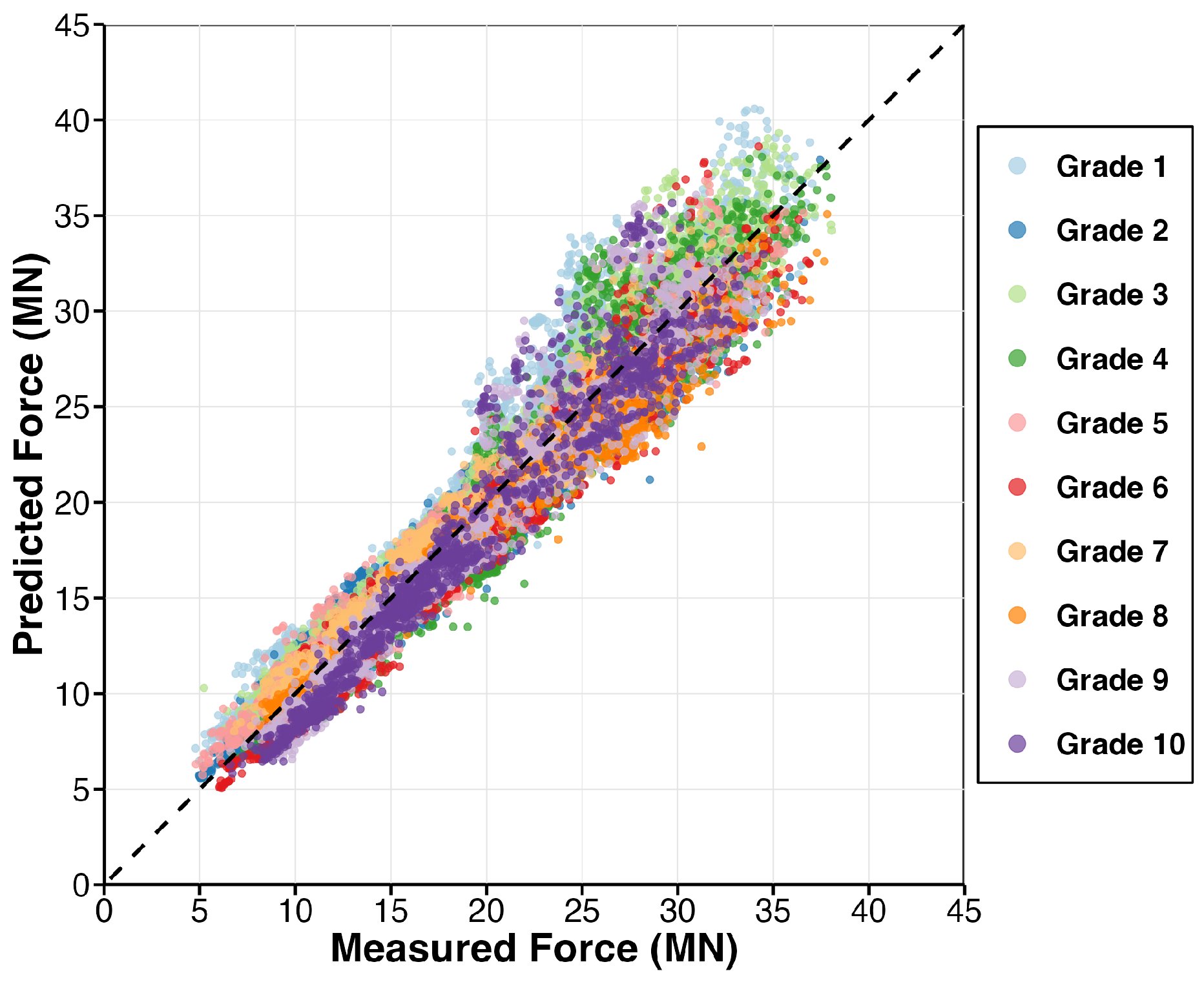

8. Grade-Specific Models

9. Discussion

9.1. Model Selection

9.2. Comparison with Previous Literature

9.3. Practical Implications

10. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Roberts, W.L. Hot Rolling of Steel; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalpakjian, S.; Schmid, S.R. Manufacturing Engineering and Technology, 7th ed.; Pearson: London, UK, 2014; Chapter 13. [Google Scholar]

- Alexander, J.M. On the Theory of Rolling. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. A 1972, 326, 535–563. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, R.M. Recent Advances on Rolling Force Model—Solutions of von Karman Rolling Equations. In Proceedings of the METEC 2015, Düsseldorf, Germany, 15–19 June 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Servín-Castañeda, R.; Nahuat Arreguín, J.J.; Domínguez Lugo, A.J.; Vega Lebrun, C.A.; Pérez Alcolea, R.; Espinosa Freyre, D. Making and Application of a Mathematical Model for the Hot Strip Rolling Process. In Proceedings of the 1st International Congress on Instrumentation and Applied Sciences, Cancun, Mexico, 26–29 October 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, X.; Zhu, G.; Yue, B.; Qiao, S.; Gao, X.; Guo, N.; Xu, M. Research on cast-rolling force in twin-roll continuous strip casting based on uncertainty analysis. Mater. Today Commun. 2020, 24, 101100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Tong, C.; Lin, F. Rolling Force Prediction Based on Wavelet Multiple-RBF Neural Network. In Proceedings of the 2012 IEEE International Conference on Information and Automation, Shenyang, China, 6–8 June 2012; pp. 941–944. [Google Scholar]

- Greivel, G.; Bandyopadhyay, S.; Newman, A.M.; Thomas, B.G. Multiple Regression with Transformations and Variable Selection at the Industrial Scale. J. Stat. Data Sci. Educ. 2025, 33, 285–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sellars, C.M.; McTegart, W.J. On the mechanism of hot deformation. Acta Metall. 1966, 14, 1136–1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, S.; Somani, M.C.; Setman, D.; Mula, S. Hot Deformation Characteristic and Strain Dependent Constitutive Flow Stress Modelling of Ti+Nb Stabilized Interstitial Free Steel. Met. Mater. Int. 2021, 27, 2481–2498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonas, J.J.; Sellars, C.M.; Tegart, W.J.M. Strength and structure under hot-working conditions. Int. Metall. Rev. 1969, 14, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.; Lee, Y.; Hodgson, P.D. A comparative study of microstructures and mechanical properties obtained by bar and plate rolling. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2002, 124, 329–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhinwal, S.S.; Toth, L.S.; Lapovok, R.; Hodgson, P.D. Tailoring one-pass asymmetric rolling of extra low carbon steel for shear texture and recrystallization. Materials 2019, 12, 1935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, E.L.; DeArdo, A.J. On the origin of equiaxed austenite grains that result from the hot rolling of steel. Metall. Trans. A 1981, 12, 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, S.J.; Li, W.G.; Liu, X.H.; Du, F.S.; Shi, L.L.; Shi, Z.P. Multi-Objective Load Distribution Optimization for Hot Strip Mills. J. Iron Steel Res. Int. 2013, 20, 27–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, D.; Stachowiak, R.; Samarasekera, I.; Brimacombe, J. Mathematical Modelling of Deformation During Hot Rolling. In Conference Proceedings; CONF-9410290–3; The Centre for Metallurgical Process Engineering, UBC: Vancouver, BC, Canada, 1994. Available online: https://www.osti.gov/servlets/purl/34420-xHJJdH/webviewable/ (accessed on 13 November 2025).

- Devadas, C.; Samarasekera, I.V.; Hawbolt, E.B. The thermal and metallurgical state of steel strip during hot rolling: Part I. Characterization of heat transfer. Metall. Trans. A 1991, 22, 307–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Rath, S.; Kumar, M. Simulation of Plate Rolling Process Using Finite Element Method. Mater. Today Proc. 2021, 42, 650–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagheripoor, M.; Bisadi, H. An Investigation on the Roll Force and Torque Fluctuations During Hot Strip Rolling Process. Prod. Manuf. Res. 2014, 2, 128–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poliak, E.; Shim, M.; Kim, G.; Choo, W. Application of linear regression analysis in accuracy assessment of rolling force calculations. Met. Mater. 1998, 4, 1047–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, A.A.d.; Barbosa, J.V. Calculation of Rolling Force in the Hot Strip Finishing Mill Using an Empirical Model. Tecnol. Metal. Mater. Mineração 2020, 17, 149–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.G.; Liu, C.; Liu, B.; Yan, B.K.; Liu, X.H. Modeling friction coefficient for roll force calculation during hot strip rolling. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2017, 92, 597–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portmann, N.F.; Lindhoff, D.; Sorgel, G.; Gramckow, O. Application of neural networks in rolling mill automation. Iron Steel Eng. 1995, 72, 33–36. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, J.; Che, H.; Xu, Y.; Dou, F. Application of Adaptable Neural Networks for Rolling Force Set-Up in Optimization of Rolling Schedules. In Advances in Neural Networks – ISNN 2006; Wang, J., Yi, Z., Zurada, J.M., Lu, B.-L., Yin, H., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2006; pp. 864–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.; Lee, Y. Application of Neural-Network for Improving Accuracy of Roll-Force Model in Hot-Rolling Mill. Control Eng. Pract. 2002, 10, 473–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pican, N.; Alexandre, F.; Bresson, P. Artificial Neural Networks for the Presetting of a Steel Temper Mill. IEEE Expert 1996, 11, 22–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, J.S.; Lee, D.M.; Kim, I.S.; Choi, S.G. A Study on On-Line Learning Neural Network for Prediction for Rolling Force in Hot-Rolling Mill. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2005, 164–165, 1612–1617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakur, S.K.; Das, A.K.; Jha, B.K. Application of Machine Learning Methods for the Prediction of Roll Force and Torque During Plate Rolling of Micro-Alloyed Steel. J. Alloys Metall. Syst. 2023, 4, 100044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrios, J.A.; Torres-Alvarado, M.; Cavazos, A.; Leduc, L. Neural and Neural Gray-Box Modeling for Entry Temperature Prediction in a Hot Strip Mill. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2011, 20, 1128–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beynon, J.H.; Sellars, C.M. Modelling microstructure and its effects during multipass hot rolling. ISIJ Int. 1992, 32, 359–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Wang, Z.; Guo, Y. A Novel Analytical Model for Prediction of Rolling Force in Hot Strip Rolling Based on Tangent Velocity Field and MY Criterion. J. Manuf. Processes 2019, 47, 202–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavaliere, M.A.; Goldschmit, M.B.; Dvorkin, E. Finite Element Analysis of Steel Rolling Processes. Comput. Struct. 2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soulami, A.; Lavender, C.A.; Paxton, D.M.; Burkes, D.E. Rolling Process Modeling Report: Finite-Element Prediction of Roll-Separating Force and Rolling Defects; PNNL-23313; Pacific Northwest National Lab. (PNNL): Richland, WA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Kutner, M.H.; Nachtsheim, C.J.; Neter, J.; Li, W. Applied Linear Statistical Models, 5th ed.; McGraw-Hill/Irwin: Boston, MA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery, D.C.; Peck, E.A.; Vining, G.G. Introduction to Linear Regression Analysis, 5th ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Bhadeshia, H.K.D.H.; Honeycombe, R. Steels: Microstructure and Properties, 4th ed.; Butterworth-Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Karman, T.V. On the Theory of Rolling. Z. Angew. Math. Mech 1925, 5, 130–141. [Google Scholar]

- Li, S.; Wang, Z.; Liu, C.; Ruan, J.; Xu, Z. A Simplified Method to Calculate the Rolling Force in Hot Rolling. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2017, 88, 2053–2059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sims, R.B. The calculation of roll force and torque in hot rolling mills. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. 1954, 168, 191–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dieter, G.E.; Bacon, D. Mechanical Metallurgy; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Abbaschian, R.; Abbaschian, L.; Reed-Hill, R.E. Physical Metallurgy Principles, 4th ed.; Cengage Learning: Boston, MA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Sellars, C.M.; Tegart, W.J.M. Hot Workability. Int. Metall. Rev. 1972, 17, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zener, C.; Hollomon, J.H. Effect of Strain Rate upon Plastic Flow of Steel. J. Appl. Phys. 1944, 15, 22–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faraway, J.J. Linear Models with R, 2nd ed.; Chapman and Hall/CRC: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Greene, W.H. Econometric Analysis, 8th ed.; Pearson: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 56–57. [Google Scholar]

- Medina, S.F.; Hernandez, C.A. Modelling of the dynamic recrystallization of austenite in low alloy and microalloyed steels. Acta Mater. 1996, 44, 165–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mecking, H.; Kocks, U. Kinetics of flow and strain-hardening. Acta Metall. 1981, 29, 1865–1875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gladman, T. The Physical Metallurgy of Microalloyed Steels; Institute of Materials: London, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Jonas, J.; Weiss, I. Effect of precipitation on recrystallization in microalloyed steels. Met. Sci. 1979, 13, 238–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yılmaz, F.; Güvenç, M.A.; Mıstıkoğlu, S. Prediction of rolling force and spread in hot rolling process by artificial neural network and multiple linear regression. Int. Adv. Res. Eng. J. 2025, 9, 26–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Symbol | Range | Units |

|---|---|---|---|

| Entry gauge | 1.87–35.6 | mm | |

| Exit gauge | 1.51–27.83 | mm | |

| Roll radius | r | 295–401 | mm |

| Strip width | w | 936–1720 | mm |

| Strip temperature | T | 1091–1306 | K |

| Roll force | F | 4.8–38.1 | MN |

| Symbol | Definition | Units |

|---|---|---|

| Material Properties and Stress Parameters | ||

| Instantaneous flow stress | [MPa] | |

| Mean flow stress | [MPa] | |

| K | Strength coefficient (depends on grade, temperature, strain, and strain rate) | [MPa] |

| n | Strain hardening exponent | [-] |

| True strain | [mm/mm] | |

| Activation energy | [MPa·mm3/mol] | |

| R | Universal gas constant () | [MPa·mm3/(mol·K)] |

| T | Temperature | [K] |

| Geometric and Force Parameters | ||

| F | Roll separating force | [MPa·mm2 = N] |

| [MPa·m2 = MN] | ||

| w | Strip width | [mm] |

| ℓ | Contact length | [mm] |

| r | Roll radius | [mm] |

| Entry gauge | [mm] | |

| Exit gauge | [mm] | |

| Entry gauge of coil at roll Stand 1 | [mm] | |

| Process Parameters | ||

| Contact time | [s] | |

| v | Exit velocity | [mm/s] |

| Estimated mean entry velocity at Stand 1 | [mm/s] | |

| Strain rate | [s−1] | |

| Strain rate exponent | [-] | |

| Model-Specific Parameters | ||

| Z | Zener–Hollomon parameter | [s−1] |

| A | Pre-exponential factor | [MPa] |

| Strain-rate-adjusted pre-exponential factor | [MPa] | |

| Pre-exponential factor for Model (Mi), | [MPa] |

| Variable | Stand 1 | Stand 2 | Stand 3 | Stand 4 | Stand 5 | Overall |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measured Variables | ||||||

| Entry gauge [mm] | 25.8 ± 2.1 | 18.2 ± 2.0 | 12.4 ± 1.8 | 8.5 ± 1.5 | 5.8 ± 1.2 | 14.1 ± 7.4 |

| Exit gauge [mm] | 18.2 ± 2.0 | 12.4 ± 1.8 | 8.5 ± 1.5 | 5.8 ± 1.2 | 4.0 ± 0.9 | 9.8 ± 5.6 |

| Roll diameter [mm] | 775 ± 45 | 760 ± 42 | 745 ± 40 | 730 ± 38 | 715 ± 35 | 745 ± 44 |

| Width [mm] | 1285 ± 185 | 1285 ± 185 | 1285 ± 185 | 1285 ± 185 | 1285 ± 185 | 1285 ± 185 |

| Temperature [K] | 1265 ± 18 | 1242 ± 17 | 1220 ± 16 | 1198 ± 16 | 1176 ± 15 | 1220 ± 38 |

| Roll Force [MN] | 24.2 ± 3.8 | 20.5 ± 3.2 | 17.1 ± 2.8 | 14.2 ± 2.4 | 11.8 ± 2.1 | 17.6 ± 5.4 |

| Calculated Variables | ||||||

| Entry velocity [mm/s] | 1096 | 1670 ± 185 | 2450 ± 350 | 3570 ± 520 | 5240 ± 780 | 2822 ± 1480 |

| Exit velocity [mm/s] | 1670 ± 185 | 2450 ± 350 | 3570 ± 520 | 5240 ± 780 | 7590 ± 1120 | 4104 ± 2150 |

| Contact length [mm] | 22.5 ± 2.8 | 18.2 ± 2.3 | 14.8 ± 2.0 | 11.5 ± 1.6 | 8.9 ± 1.3 | 15.2 ± 5.3 |

| Contact time [s] | 0.015 ± 0.004 | 0.008 ± 0.002 | 0.004 ± 0.001 | 0.002 ± 0.001 | 0.001 ± 0.0004 | 0.006 ± 0.005 |

| Strain [mm/mm] | 0.35 ± 0.06 | 0.38 ± 0.05 | 0.42 ± 0.05 | 0.45 ± 0.05 | 0.48 ± 0.06 | 0.42 ± 0.08 |

| Strain rate [s−1] | 35 ± 12 | 68 ± 22 | 142 ± 48 | 285 ± 95 | 520 ± 180 | 210 ± 195 |

| Stress [MPa] | 135 ± 22 | 162 ± 26 | 185 ± 30 | 208 ± 34 | 235 ± 38 | 185 ± 45 |

| Model | Root Mean Square Error (MN) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Combined Grade) | Training Data | Testing Data | Training Data | Testing Data |

| M1 | 0.949 | 0.948 | 1.61 | 1.60 |

| M2 | 0.947 | 0.946 | 1.65 | 1.64 |

| M3 | 0.945 | 0.945 | 1.66 | 1.65 |

| Grade | # of Coils | Data Points | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2254 | 11,270 | 91.61 | 0.322 | 0.991 | 1.055 | 0.967 |

| 2 | 1543 | 7710 | 213.56 | 0.356 | 0.880 | 1.032 | 0.972 |

| 3 | 1182 | 5910 | 154.36 | 0.303 | 0.947 | 1.027 | 0.974 |

| 4 | 760 | 3800 | 208.50 | 0.267 | 1.017 | 0.864 | 0.965 |

| 5 | 392 | 1960 | 107.70 | 0.395 | 0.916 | 1.107 | 0.972 |

| 6 | 372 | 1860 | 81.53 | 0.290 | 1.131 | 0.872 | 0.977 |

| 7 | 335 | 1675 | 621.49 | 0.294 | 0.759 | 1.028 | 0.978 |

| 8 | 333 | 1665 | 113.84 | 0.325 | 0.982 | 1.043 | 0.983 |

| 9 | 320 | 1600 | 1247.30 | 0.216 | 0.827 | 0.799 | 0.954 |

| 10 | 306 | 1530 | 665.27 | 0.215 | 0.926 | 0.780 | 0.967 |

| Total | 7797 | 38,980 |

| Grade | # of Coils | Data Points | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2254 | 11,270 | 117.6 | 0.291 | 0.958 |

| 2 | 1543 | 7710 | 103.6 | 0.346 | 0.970 |

| 3 | 1182 | 5910 | 122.6 | 0.288 | 0.967 |

| 4 | 760 | 3800 | 108.2 | 0.342 | 0.938 |

| 5 | 392 | 1960 | 94.9 | 0.362 | 0.971 |

| 6 | 372 | 1860 | 102.2 | 0.364 | 0.958 |

| 7 | 335 | 1675 | 123.1 | 0.285 | 0.969 |

| 8 | 333 | 1665 | 130.3 | 0.295 | 0.976 |

| 9 | 320 | 1600 | 103.8 | 0.344 | 0.907 |

| 10 | 306 | 1530 | 102.6 | 0.353 | 0.912 |

| Total | 7797 | 38,980 |

| Grade | M1 | M2 | M3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Combined Models | |||

| - | 0.948 | 0.947 | 0.946 |

| Grade-Specific Models | |||

| 1 | 0.972 | 0.967 | 0.963 |

| 2 | 0.972 | 0.972 | 0.970 |

| 3 | 0.977 | 0.974 | 0.971 |

| 4 | 0.966 | 0.965 | 0.961 |

| 5 | 0.973 | 0.972 | 0.970 |

| 6 | 0.977 | 0.977 | 0.974 |

| 7 | 0.978 | 0.978 | 0.975 |

| 8 | 0.983 | 0.983 | 0.981 |

| 9 | 0.961 | 0.954 | 0.948 |

| 10 | 0.970 | 0.967 | 0.962 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Udofia, E.; Messer, L.; Greivel, G.; Newman, A.; Thomas, B.G. A Statistical-Based Model of Roll Force During Commercial Hot Rolling of Steel. Metals 2025, 15, 1346. https://doi.org/10.3390/met15121346

Udofia E, Messer L, Greivel G, Newman A, Thomas BG. A Statistical-Based Model of Roll Force During Commercial Hot Rolling of Steel. Metals. 2025; 15(12):1346. https://doi.org/10.3390/met15121346

Chicago/Turabian StyleUdofia, Edikan, Luke Messer, Gus Greivel, Alexandra Newman, and Brian G. Thomas. 2025. "A Statistical-Based Model of Roll Force During Commercial Hot Rolling of Steel" Metals 15, no. 12: 1346. https://doi.org/10.3390/met15121346

APA StyleUdofia, E., Messer, L., Greivel, G., Newman, A., & Thomas, B. G. (2025). A Statistical-Based Model of Roll Force During Commercial Hot Rolling of Steel. Metals, 15(12), 1346. https://doi.org/10.3390/met15121346