Abstract

Lithium has emerged as a critical energy metal due to its indispensable role in batteries, aerospace applications, new energy vehicles, and large-scale energy storage systems. The accelerated growth of electric mobility and renewable energy storage has led to a substantial increase in lithium demand, thereby exacerbating the prevailing global supply–demand imbalance. To address this challenge, it is imperative to diversify lithium resources and to advance extraction technologies that are both efficient and sustainable. In comparison with conventional hard-rock deposits, liquid resources such as salt lake brines, oilfield brines, and deep-well brines are gaining attention owing to their broad distribution, abundant reserves, and advantages of reduced land use, lower water consumption, and lower carbon emissions. This work presents a critical review of current lithium recovery strategies from brines, including precipitation, solvent extraction, adsorption, nanofiltration/electrodialysis, and electrochemical methods. Each approach is critically evaluated in terms of Li/Mg selectivity, extraction efficiency, operational stability, and environmental compatibility. Precipitation processes offer simplicity but suffer from low Li recovery and high chemical consumption; solvent extraction achieves high selectivity but faces phase and reagent loss; adsorption using Mn-based sieves yields high capacity with good regeneration stability, whereas membrane and electrochemical systems enable continuous lithium recovery with reduced energy input. Distinct advantages and existing gaps are systematically summarized to provide quantitative insights into performance trade-offs among these pathways. Key findings highlight that organophosphorus–FeCl3 systems and Mn-based lithium-ion sieves show the best trade-off between selectivity and regeneration stability, whereas emerging membrane–electrochemical hybrids demonstrate promise for low-energy, continuous lithium recovery. The prospects for future development highlight highly selective functional materials, integrated multi-technology processes, and greener, low-energy extraction pathways.

1. Introduction

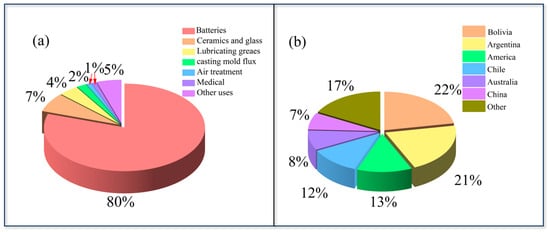

Lithium is recognized as a pivotal energy metal [,]. It exhibits a series of remarkable physicochemical properties, including low density (0.534 g·cm−3), a highly negative standard electrode potential (–3.04 V), and a high specific heat capacity (3.58 kJ·kg−1·K−1). According to the latest statistics released by the United States Geological Survey (USGS, 2023) [], lithium and its compounds are of considerable technological importance in various industries. As demonstrated in Figure 1a, the applications of these materials are diverse, encompassing lithium-ion batteries [], specialty glass and ceramics, continuous casting mold powders, air treatment, high-temperature lubricants, and even psychiatric medications [,]. The accelerated growth of the new energy vehicle industry and large-scale energy storage deployment has led to a marked increase in global lithium carbonate consumption []. In order to meet the targets outlined in the Paris Agreement, it is estimated that the supply gap will exceed 538,000 tons by 2030 []. Furthermore, the International Energy Agency has predicted that global lithium demand will increase by a factor of 42 between 2020 and 2040, emphasizing the pressing need for diversified resources and advanced extraction technologies.

Figure 1.

(a) Distribution of lithium-ion and its compounds of application; (b) the global lithium resource distribution.

Lithium resources are generally categorized into two major types: hard-rock deposits and brine deposits []. The former mainly include clay minerals, lithium-bearing montmorillonite, and pegmatites, while the latter consist of salt lake brines, geothermal brines, oilfield brines, and deep-well brines. According to data from the United States Geological Survey (USGS, 2023) [], the global identified lithium resources are estimated at approximately 98 million tons, with their distribution illustrated in Figure 1b. China holds approximately 6.8 million tons, which is approximately 7% of the global total. Globally, lithium resources are mainly distributed in brines (about 58%) and hard rocks (about 26%), whereas in China, hard-rock resources constitute roughly 15% of the total and the majority (around 80%) occur in salt lake brines. It should be noted that, on a global scale, most lithium brine resources are concentrated in South America, particularly in Chile, Argentina, and Bolivia, known as the “Lithium Triangle,” where the lithium concentrations often exceed 500 mg·L−1. In contrast, China’s brine resources are primarily distributed in the Qinghai and Tibet regions, representing important domestic reserves. From an economic standpoint, the extraction of brine resources typically incurs a cost that is 30–50% lower than that of hard-rock mining []. The lithium-ion concentrations in these brines are typically above 300 mg·L−1, which is considered commercially feasible for industrial lithium extraction. Brine extraction offers distinct advantages, including reduced land occupation, lower water consumption, and reduced carbon emissions []. Furthermore, the reinjection of lithium-depleted brines back into the strata enables a coordinated balance between resource utilization and environmental protection [].

Brine-based lithium extraction technologies can generally be classified by mechanism into precipitation [,], solvent extraction [,], adsorption [,], membrane separation/electrodialysis [], and electrochemical methods []. The precipitation method is relatively mature and cost-effective, yet its long processing cycle, operational complexity, and strong dependence on the Mg/Li ratio limit its application []. Solvent extraction is a process that offers separation efficiency, high selectivity, and reduced processing times []. However, challenges such as extractant loss and the use of strong acids and bases can be problematic, including reagent degradation and equipment corrosion. The process of adsorption is distinguished by its operational simplicity and high recovery efficiency. However, significant drawbacks remain in the form of adsorbent dissolution and poor recyclability. Membrane separation and electrodialysis achieve high selectivity; their efficiency is constrained by membrane fouling and relatively low separation performance []. Electrochemical methods are regarded as both efficient and environmentally friendly, though high energy consumption and low technological maturity hinder large-scale deployment [].

In brine systems, particularly those with high Mg/Li ratios and multiple coexisting ions (Na+, K+, Ca2+, Mg2+), lithium extraction faces considerable technical challenges. The similar ionic radii and hydration energies of Li+ and Mg2+ lead to strong competitive coordination, reducing Li/Mg selectivity and complicating purification. Climatic conditions and impurity variability across different salt lakes further impact process stability and efficiency. Currently, industrial-scale lithium extraction mainly relies on adsorption using Mn-based lithium-ion sieves and solvent extraction with organophosphorus reagents, which provide high selectivity and capacity but still encounter issues of regeneration, reagent stability, and cost. These challenges underscore the need to optimize both material design and process integration for sustainable lithium recovery.

In order to address the escalating global demand for lithium and its derivatives while at the same time aligning with sustainability objectives, there is an imperative for the integration and synergistic development of multiple extraction technologies. This review provides an in-depth assessment of the major extraction approaches for lithium recovery from brines, examining their current applications, existing challenges, and potential future directions. The objective is to offer theoretical insights and technical references for the advancement of efficient, green, and sustainable brine-based lithium extraction.

2. Brine Characteristics

Brines represent highly diverse natural resources that vary significantly in chemical composition and physical properties depending on their geological origins []. These differences profoundly influence the selection and performance of solvent extraction systems. Generally, lithium-rich brines can be classified into three main types: salt lake brines, oilfield brines, and geothermal brines []. Salt lake brines are typically characterized by high salinity and complex ionic compositions, with Mg/Li ratios ranging from a few dozen to over several hundred []. The high concentration of Mg2+ and Ca2+ leads to strong competition with Li+ during extraction, posing major selectivity challenges []. The anion composition also varies widely (Cl−, SO42−, or CO32−), influencing complex formation and phase equilibrium in extraction processes. Oilfield brines usually contain higher concentrations of Ca2+ and Na+ and may exhibit elevated pH values or distinct buffering capacities due to carbonate equilibria. Their relatively high density and viscosity can affect mass transfer kinetics and phase disengagement during extraction []. Oilfield brines are generally cooler (40–90 °C) than geothermal brines and thus do not exhibit the severe silica polymerisation or metal scaling behavior typically observed in high-temperature geothermal fluids [].

In contrast, Although geothermal brines are a rich source of lithium-ions (Li+), they also contain high concentrations of other substances, such as Fe2+, Mn2+, and silica, and organically complexed metals, many of which are thermodynamically unstable under the high-temperature conditions of geothermal reservoirs (>150–250 °C). These species readily undergo hydrolysis, oxidation, or polymerisation, forming dense mineral scaling layers on extraction interfaces []. Among these impurities, silica and Fe2+ are particularly problematic. Silica exhibits strong temperature-dependent polymerisation; upon cooling, monomeric Si(OH)4 rapidly forms colloidal silica or amorphous SiO2 precipitates, which foul membranes, adsorbents, and electrochemical electrodes and significantly hinder interfacial mass transfer []. These interfering components are typically removed through pretreatment processes such as aeration–oxidation coupled with Fe/Mn precipitation, silica softening via pH adjustment and magnesium dosing, alum coagulation, barite precipitation for Ba2+ removal, and subsequent solid–liquid separation steps including ultrafiltration []. Such pretreatment is essential for geothermal brines because their elevated temperatures significantly accelerate scaling reactions, reduce the stability of extraction materials, and alter phase equilibria. High temperatures (typically 120–300 °C at production wells) also decrease viscosity and increase reaction kinetics, which may enhance lithium mobilization but simultaneously intensify precipitation, corrosion, and fouling phenomena.

Consequently, geothermal brines pose considerably greater challenges for lithium extraction than oilfield brines, requiring more rigorous pretreatment and carefully engineered extraction systems to ensure stable and efficient operation.

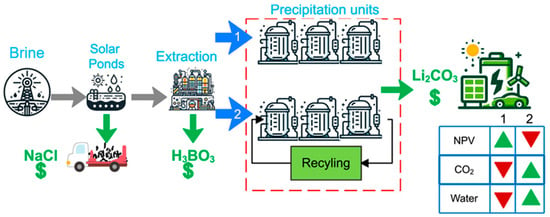

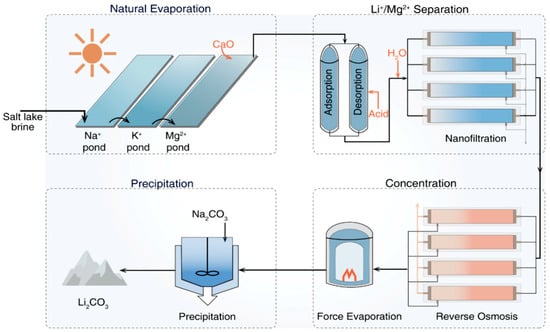

3. Precipitation Method

The precipitation method, predicated on the principle of stepwise crystallization, is among the earliest and most well-established technologies for lithium recovery from brines. The core process of the facility in question depends on solar evaporation to concentrate brines and sequentially separate impurities. The method offers certain advantages, including ease of operation, technological maturity, and relatively low production costs. A typical process, illustrated in Figure 2, involves evaporative concentration of brine, during which sodium chloride, potassium chloride, and carnallite crystallize sequentially until the Li+ concentration reaches approximately 6% (w/w). Subsequently, hydrochloric acid is introduced to remove boron, resulting in the generation of boric acid as a by-product. Subsequent additions of CaO and Na2CO3 precipitate Mg2+ and Ca2+, respectively. Li+ is then recovered as Li2CO3 via Na2CO3 precipitation, achieving a purity of 99% []. In addition to conventional carbonate-based precipitation routes, aluminum-based precipitation has emerged as an alternative strategy for lithium recovery from brines. In this method, Al3+ reacts with Mg2+ to preferentially form Mg–Al layered double hydroxides (LDHs), thereby selectively eliminating magnesium without inducing substantial lithium loss []. Owing to its strong affinity toward Mg2+, the aluminum-based precipitation route has demonstrated high Mg2+ removal efficiencies and improved lithium retention, particularly in brines with elevated Mg/Li ratios where traditional precipitation methods exhibit limited applicability.

Figure 2.

The classical process of lithium recovery by precipitation method. Adapted from ref. [].

Despite the aforementioned advantages, large-scale industrial implementation of the precipitation method is constrained by several drawbacks. These include a protracted processing cycle, elevated consumption of alkaline precipitants, and an overall lithium recovery rate frequently below 50%. Furthermore, it has been demonstrated that the method is only applicable to brines with low Mg/Li ratios (<10) [].

In order to address these limitations, researchers have explored the use of novel precipitants and have optimized process parameters. As reported by Zhang et al. [], sodium metasilicate nonahydrate, utilized as a novel precipitant in simulated brines with a Mg/Li ratio of 30, attained a lithium recovery rate of 86.73%. The reagent demonstrated a preference for the precipitation of Mg2+, exhibiting a removal efficiency of 99.94%, while ensuring that lithium losses during magnesium removal remained below 5%. This observation signifies the reagent’s efficacy in terms of selectivity and suggests a promising avenue for future applications. Battaglia et al. [] proposed an alternative LiCl–NaOH–CO2 precipitation route that enabled the separation and purification of lithium from low-concentration brines, with a Li+ concentration much lower than that typically required for Na2CO3 precipitation. At a high temperature of 80 °C, the alkalinity of the brine was adjusted using NaOH. This was followed by CO2 injection and ethanol washing. The result was an 80% recovery of lithium with a final Li2CO3 purity of 99%. These studies demonstrate that, by carefully selecting precipitants and refining process steps, it is possible to mitigate the detrimental effects of magnesium interference and enhance overall recovery efficiency.

Looking ahead, the precipitation method is expected to evolve in several directions: the design of precipitants with enhanced multifunctional selectivity; the incorporation of dynamic process control strategies, such as real-time monitoring of pH and ionic strength, which can enable intelligent dosing and precise endpoint determination; and the advancement of intelligent large-scale application scenarios through the establishment of predictive models that link brine composition to process parameters, thereby accelerating process optimization.

4. Solvent Extraction Technology

The physicochemical characteristics of brines—such as ion ratios, salinity, and anion composition—strongly affect the performance and selectivity of extraction systems. Building on this understanding, solvent extraction has been shown to offer several advantages in recovering lithium from brines. These include high selectivity, high extraction efficiency, simplified process flow, and the potential for continuous operation and large-scale industrial application. Consequently, it is widely regarded as one of the most promising technologies for brine-based lithium production. Currently, the most commonly used extractant systems include organophosphorus compounds [,], alcohol-ketone compounds [], crown ethers and their derivatives [,], and ionic liquids [,].

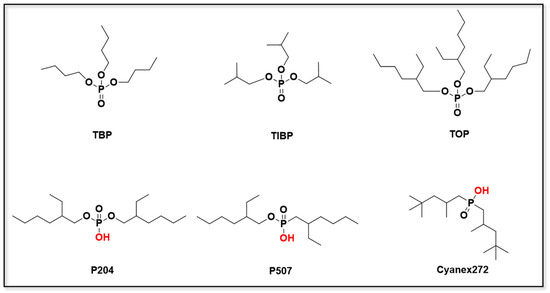

4.1. Organophosphorus Extraction Systems

Organophosphorus extractants selectively separate metal ions through chelation or coordination between phosphoryl oxygen (P=O) and the target ions. Based on their molecular structure, they can be broadly categorized as either neutral or acidic, with representative examples shown in Figure 3. The selectivity of neutral organophosphorus extractants towards Li+ arises mainly from coordination between the phosphoryl oxygen and the cation. This is modulated by the electron density of the P=O bond and steric hindrance effects. In this revised version, the figures illustrating the coordination mechanisms have been redrawn to improve clarity. Additional comparative discussion has been added to highlight the differences in Li/Mg selectivity and regeneration behavior between neutral and acidic extractants. This interaction is further explained by the Hard and Soft Acids and Bases (HSAB) principle, which states that Li+, as a hard acid, preferentially coordinates with hard bases such as the oxygen atom in phosphoryl groups. The electron density on the phosphoryl oxygen, as well as the steric hindrance effects, significantly influences the strength and stability of the coordination complex. This HSAB principle helps explain the higher selectivity of organophosphorus extractants for Li+ over softer cations. In contrast, acidic organophosphorus extractants operate through cation exchange mechanisms, and their extraction behavior is highly pH-dependent, typically showing superior performance under alkaline conditions []. Notably, acidic organophosphorus extractants generally exhibit extraction affinities for divalent cations that are two orders of magnitude greater than for Li+. This is because the cation exchange mechanism is more favorable for divalent ions, which are softer acids compared to Li+ [].

Figure 3.

The molecular structures of commonly used neutral and acidic organophosphorus extractants.

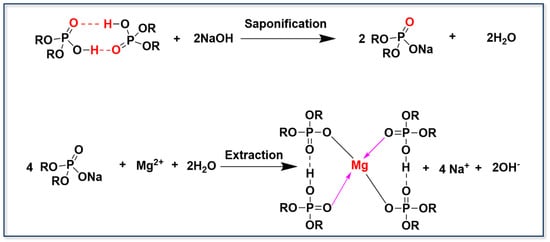

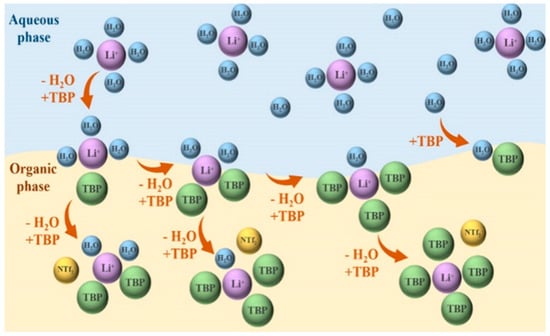

Tributyl phosphate (TBP), a neutral organophosphorus extractant, has been successfully used with FeCl3 as a synergist for lithium extraction from high-magnesium chloride-type salt lake brines. Zhou et al. [] used TBP as the extractant and FeCl3, ZnCl2, and CrCl3 as synergists, and compared the influence of different diluents—kerosene, methyl isobutyl ketone (MIBK) and, 2-octanol—on extraction performance. The results showed that, with the same diluent, FeCl3 resulted in a significantly higher lithium extraction efficiency than the other two synergists. When FeCl3 served as the synergist, the order of extraction efficiency among the diluents was MIBK > kerosene > 2-octanol. This indicates that solvent polarity and molecular structure have a significant impact on lithium separation behavior. Highly polar diluents, such as MIBK, can stabilize polar intermediates and enhance the coordination interaction between TBP and FeCl3, thereby promoting the extraction of Li+. In contrast, low-polarity solvents, such as kerosene, or protic solvents containing hydroxyl groups, may hinder complex formation or compete for coordination sites. Interestingly, when CrCl3 was used as the synergist, the system performed better in 2-octanol, which is more polar; this was attributed to the distinctive coordination chemistry of Cr3+. Therefore, the polarity and donor characteristics of the diluent influence both the solvation environment of extractant molecules and the stability and formation kinetics of metal–extractant complexes. These findings emphasize the importance of considering the compatibility of diluents and synergists, as well as the behavior of metal ions in coordination, when designing solvent extraction systems. In the TBP–FeCl3 system for separating and purifying Li+ from brines, the reaction mechanism is described by Equations (1)–(3).

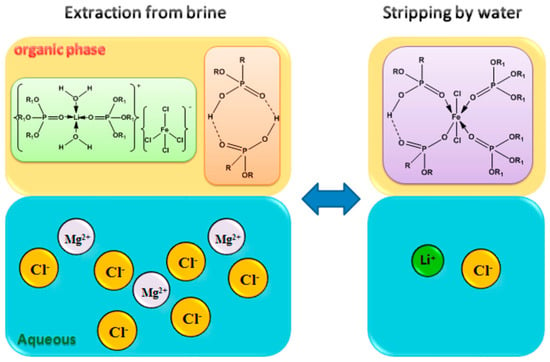

At low chloride concentrations, the weak complexing interaction between Fe3+ and Cl− inhibits the formation of LiFeCl4, thereby preventing the selective extraction of Li+ by TBP []. Therefore, a sufficiently high Cl− concentration in the brine is essential to stabilize the complex. For stripping, 6 mol·L−1 HCl is commonly used to keep Fe3+ in the [FeCl4]− form in the organic phase. Regeneration of the organic phase then requires alkaline treatment. To mitigate corrosion of equipment caused by strong acids and bases, researchers have introduced two extractants into the extraction system: 2-ethylhexylphosphonic acid mono-2-ethylhexyl ester (P507) and di-(2-ethylhexyl) phosphoric acid (P204) into the extraction system. This allows the use of pure water instead of concentrated HCl as the stripping agent. Su et al. [] developed a TBP–P507–FeCl3 ternary extraction system for separating and purifying Li+ from brines with a high Mg-to-Li ratio. Under optimized conditions, they achieved a single-stage lithium extraction efficiency of 84.5%, while limiting the co-extraction of Mg2+ to 2.6%. After three stages of countercurrent washing and stripping, the Li+ concentration increased to 20.9 g·L−1, while the Mg2+ concentration decreased to ~2.2 g·L−1. In this system, lithium was effectively recovered using pure water as the stripping agent, with the stripping efficiencies of up to 85%. Meanwhile, Fe3+ remained stable in the organic phase, eliminating the need for regeneration and allowing direct reuse of the organic phase. As shown in Figure 4, reversible transformations occurred between [Li(TBP)2][FeCl4] and FeCl2L·(HL)2·2TBP when aqueous phases containing different concentrations of MgCl2 contacted the organic phase, as described by Equation (4):

where HL represents P507. Duan et al. [] elucidated the synergistic mechanism of the TBP–P204–FeCl3 system. In this case, TBP coordinates with the Li+–FeCl3 complex, thereby achieving lithium selectivity. At lower chloride concentrations (<4 mol·L−1), Fe3+ preferentially chelates with P204 to form stable organometallic complexes. As the Cl− concentration increases beyond a critical threshold, Cl− gradually displaces the P204, forming [FeCl4]− and thereby restoring the system’s extraction capability for Li+.

Figure 4.

The mechanism of lithium extraction and stripping by the TBP–P507–FeCl3. Reprinted from ref. [].

Acidic organophosphorus extractants have long been crucial reagents in the separation of metal ions. Their extraction mechanism is generally governed by an interfacial cation exchange mechanism, which enables the selective transfer of divalent cations. The extraction kinetics are influenced by both the solution pH and the hydration energy of the target metal ions. Yu et al. [] used P204 as an extractant to selectively separate Mg2+ from other metal ions and demonstrated that two P204 molecules coordinate with a single Mg2+ ion to form a stable complex (see Figure 5). Shi et al. [] further investigated the extraction behavior of P204 towards Ca2+, Mg2+, and Li+, revealing the following selectivity order: H+ > Ca2+ > Mg2+ > Li+ > Na+. This finding indicates that P204 preferentially forms complexes with protons over other metal ions. In systems containing multiple cations, particularly Ca2+ and Mg2+, which have a higher charge density and a lower hydration radius, the behavior of these competing ions has a strong influence on the extraction of Li+. Their preferential coordination with organophosphorus ligands or proton substitution can significantly suppress the transfer of Li+ into the organic phase. Consequently, the presence of high concentrations of Ca2+ and Mg2+ in brine reduces the extraction efficiency of Li+ and alters the equilibrium distribution and interfacial reaction dynamics. Following saponification with NaOH, P204 is converted to its sodium salt, significantly enhancing the selectivity of the extraction system. Using a three-stage counter-current extraction process, Ca2+ and Mg2+ were efficiently removed with removal efficiencies of 99.05% and 98.48%, respectively. Residual Li+ entrapped in the organic phase was minimized by washing with dilute hydrochloric acid to reduce the loss of lithium. Subsequent adjustment of the HCl concentration enabled the effective stripping and recovery of Ca2+ and Mg2+.

Figure 5.

The extraction mechanism of acidic organophosphorus extractants.

The TBP–FeCl3 system has been applied for the extraction of lithium from salt lake brines with high Mg/Li ratios due to its low cost, operational simplicity, and suitability for continuous processing. However, the extraction of Li+ by neutral phosphate esters primarily relies on solvation, resulting in reduced extraction efficiency in systems with low lithium concentrations or high impurity levels. Additionally, emulsification often occurs during extraction, complicating downstream separation. In contrast, the extraction performance of acidic organophosphorus extractants depends heavily on pH control and usually requires pre-saponification with NaOH. While the saponified extractant exhibits significantly enhanced selectivity for divalent cations, it can also induce the co-extraction of Li+, resulting in lithium loss. Future progress in this field is likely to be driven by theoretical calculations and rational molecular design, aiming to enhance extractant selectivity and stability through functional modification. Concurrently, efforts should be made to develop novel composite extraction systems and environmentally benign solvents that combine efficiency with economic feasibility, thereby guiding the separation of lithium from brines towards high-efficiency, low-carbon, and sustainable practices.

4.2. Alcohol–Ketone Extractants

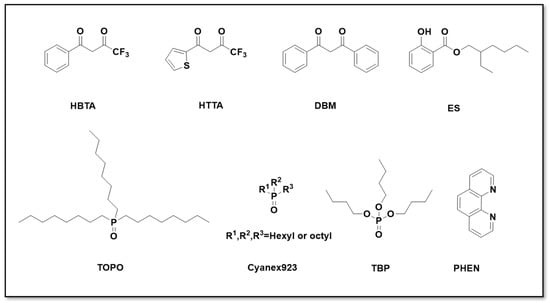

Commonly used alcohol–ketone extractants include benzoyltrifluoroacetone (HBTA), thenoyltrifluoroacetone (HTTA), dibenzoylmethane (DBM), and 2-hydroxybenzoic acid-2-ethylhexyl ester (ES). Their chemical structures are shown in Figure 6. Lithium extraction with these reagents predominantly proceeds via a cation exchange mechanism. Due to its small hydration radius, the Li+ ion can coordinate with the enolic tautomer of the extractant through sp3 hybrid orbitals while exchanging with the active hydrogen of the enolic group (see Figure 7). The presence of hydrophobic synergistic extractants, such as trioctylphosphine oxide (TOPO), mixed trialkylphosphine oxides (Cyanex 923), tributyl phosphate (TBP), and 1,10-phenanthroline (PHEN), results in the formation of stable lithium complexes that are efficiently transferred into the organic phase. Their chemical structures are shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Chemical structures of commonly used alcohol–ketone extractants and neutral organophosphorus co-extractants.

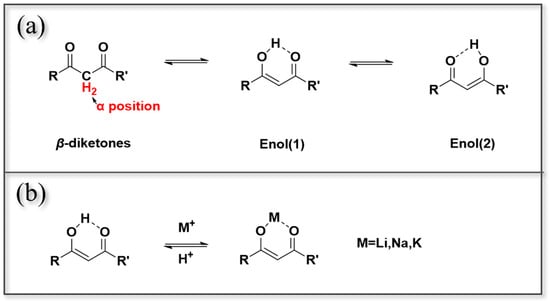

Figure 7.

(a) Chemical structures of alcohol–ketone extractants ketone and enol; (b) mechanism of interaction between alcohol–ketone extractants and alkali metal ions.

According to the Hard and Soft Acids and Bases (HSAB) principle, Li+ behaves as a typical hard acid with a small ionic radius and high charge density, and therefore preferentially interacts with hard bases containing oxygen donor atoms. In alcohol–ketone extractants, the enolic oxygen (–OH···O=) acts as a hard base site, facilitating strong Li–O coordination and stabilizing the Li–ligand complex. This coordination involves the replacement of the enolic proton by Li+, forming a chelated Li–O ring structure. However, divalent cations such as Mg2+ and Ca2+, which are slightly softer acids with lower hydration energies, display stronger interactions with the same ligands, leading to preferential extraction under certain conditions. This intrinsic acid–base hardness difference provides a fundamental explanation for the limited Li+ selectivity observed in many β-diketone systems and underscores the importance of matching extractant basicity with Li+ hard-acid nature when designing extraction reagents.

Zhang et al. [] used a synergistic extraction system consisting of dodecylbenzylmethyl-β-diketone (Lix54) and Cyanex923 to extract Li+ from mother liquor following the precipitation of lithium carbonate. With Lix54 at a concentration of 0.50 mol·L−1 and Cyanex923 at 0.25 mol·L−1, the aqueous phase reached equilibrium at pH 11.5. Here, lithium existed in the organic phase as the complex Li·Lix54·Cyanex923. McCabe–Thiele analysis showed that lithium extraction exceeded 99% under the four-stage counter-current conditions. Zhao et al. [] optimized a DBM/TBP synergistic extraction system for the effective separation of Li+ from sodium rich mother liquors. The extraction mechanism is summarized in Reactions (5)–(7):

It is revealed that TBP participates directly in lithium complexation, thereby enhancing Li+ selectivity, suppressing Na+ extraction, and markedly improving the Li/Na separation factor. TBP also acts as a diluent, reducing phase separation time to 30 s—a significant improvement on conventional alkylphosphine oxides (e.g., TOPO, TRPO, and Cyanex923). Under optimized conditions, the single-stage lithium extraction efficiency reached 99.96%, with a Li/Na separation factor exceeding 160,000. Niu et al. [] used ES, which is structurally analogous to β-diketones, alongside trialkylphosphine oxide (TRPO) as a synergist and sulfonated kerosene as a diluent, to efficiently separate Li+ from alkaline, sodium-rich solutions. Spectroscopic characterization (UV–Vis, fluorescence, 1H-NMR, and FT-IR) revealed that the keto–enol tautomerization of the ES compound drives the coordination mechanism, while the TRPO compound lowers the energy barrier for lithium complex formation. This enhances both the extraction rate and selectivity. This observation further supports the HSAB-based interpretation that the strengthened Li–O interaction underlies the enhanced extraction efficiency.

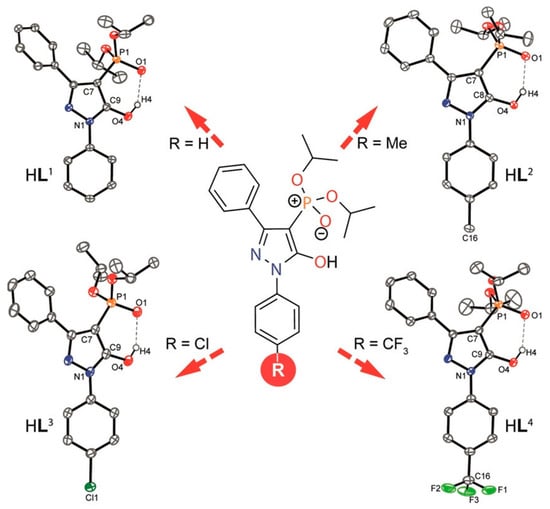

Zhang et al. [] synthesized a series of novel 4-phosphorylpyrazolone extractants that demonstrated pronounced lithium recognition and extraction capabilities. Single-crystal X-ray diffraction revealed that bimetallic lithium complexes were formed in the presence of TBP, TBPO, or acetonitrile, whereas a unique trinuclear lithium complex with a tetrahedral [Li3O] core was obtained in the TOPO system. NMR and mass spectrometry confirmed the existence of multinuclear complexes in the organic phase and revealed dynamic aggregation–dissociation behavior. Building on this work, Zhang et al. [] modified the 4-phosphorylpyrazolone framework by introducing electron-donating, electron-withdrawing, or neutral substituents at the para-position of the benzene ring (see Figure 8). Experimental results showed that electron-withdrawing groups increased the acidity of the extractant, weakened the O–H bond, and thereby enhanced lithium extraction. Competitive extraction experiments at varying pH values revealed sequential extraction behavior: at pH = 2, Ca2+ was preferentially extracted with minor Mg2+ extraction; at pH = 3, Mg2+ extraction predominated with limited Li+ uptake; and as the pH increased from 5 to 6, lithium extraction rose from 77% to 94%, while Na+ and K+ remained largely unextracted. This stepwise separation strategy offers a promising pathway for lithium recovery from acidic brines and leachates of spent lithium-ion batteries.

Figure 8.

Molecular structures of the ligands. Reprinted from ref. [].

Despite their potential, alcohol–ketone extractants generally exhibit high pKa values, requiring strongly alkaline conditions for effective dissociation. Under prolonged recycling, they are prone to hydrolysis, leading to reagent loss, environmental concerns, and increased operational costs. Moreover, their binding constants for Ca2+ and Mg2+ exceed those for Li+, resulting in preferential extraction of divalent cations and limiting applicability in Ca2+/Mg2+ rich brines. High reagent cost further constrains industrial-scale deployment. Future research should focus on structural modification of alcohol–ketone extractants by introducing electron-donating groups or multidentate coordination sites into the molecular backbone, thereby improving both Li+ selectivity and chemical stability. Development of novel extractants capable of efficient lithium recovery under mildly alkaline or near-neutral conditions would reduce acid–base reagent consumption, mitigate environmental burden, and enhance the recyclability and economic viability of the extraction system.

4.3. Crown Ethers

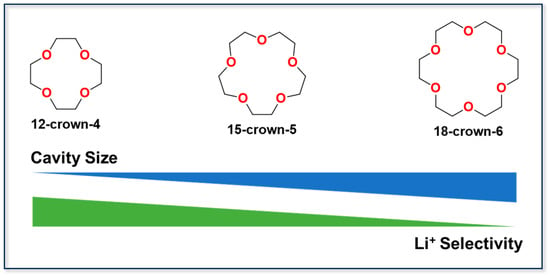

Crown ether compounds (as illustrated in Figure 9) are a class of macrocyclic molecules that contain heteroatoms. Due to their remarkable molecular recognition capability, they are used extensively in lithium isotope separation and the selective extraction of alkali metals. Their selectivity towards Li+ primarily arises from the so-called “size-matching effect”, which enables preferential complexation. Both experimental investigations and theoretical calculations confirm their exceptional lithium selectivity []. Fritz et al. [] reported a novel porous organic polymer, naphthalene-based poly(tetraoxacrown-8-ene) (NpTOC), whose polymeric backbone incorporates multiple polycyclic crown ether units to generate an abundant porous framework. This material exhibits high selectivity for Li+ ions in the presence of competing ions, such as Na+, Ca2+, and Mg2+. The lithium adsorption capacity exceeded 120 mg·g−1, demonstrating the effectiveness of supramolecular pre-design strategies in the construction of functional materials and opening new avenues for the application of porous polymers in the fields of energy and the environment. Torrejos et al. [] developed a series of dihydroxy crown ethers via an efficient intermolecular cyclisation reaction between bulky bicyclic epoxides and catechol. The incorporation of sterically demanding substituents, such as tetramethyl or bicyclopentyl groups, into the diol framework enhances the rigidity and size selectivity of the crown ethers. When larger cations such as Na+, K+, or Cs+ coordinated with these crown ethers, significant structural distortion occurred, diminishing the stability of the complexes. Xiong et al. [] reported on the preparation of a functionalized crown ether extractant via ion-imprinting technology (IIT), namely dibenzo-14-crown-4 ether with a C16 alkyl substituent (DB14C4-C16). Density functional theory (DFT) calculations revealed that DB14C4-C16 forms the most stable complex with Li+. Under optimized extraction conditions, the separation factors for this extractant were 68.09, 24.53, 16.32, and 3.99 for Li+/Ca2+, Li+/K+, Li+/Na+, and Li+/Mg2+, respectively.

Figure 9.

Typical crown ethers and their size-dependent Li+ selectivity.

Despite their advantageous features, including strong size-matching capability, tunable structures, high affinity, and stable complexation, crown ether extractants are constrained by significant limitations. These include poor Li+/Mg2+ selectivity, limited extraction capacity, insufficient chemical stability, and high production costs. Together, these factors hinder large-scale industrial deployment. Consequently, future research on crown ether-based extractants should prioritize the optimization of the molecular structure and making functional modifications to enhance extraction capacity and cycling stability. Such improvements are expected to enable the efficient, economical, and environmentally sustainable separation of lithium from complex brine systems.

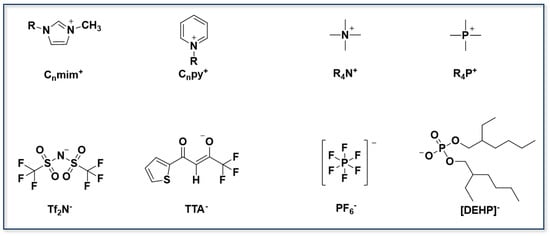

4.4. Ionic Liquids

Ionic liquids (ILs) have attracted considerable attention due to their low melting points, negligible vapor pressures, excellent solvation ability, high thermal stability, and intrinsic non-flammability. As illustrated in Figure 10, the most commonly used ionic liquid cations are imidazolium (Cnmim+), pyridinium (Cnpy+), quaternary ammonium (R4N+), and quaternary phosphonium (R4P+). Their structural tunability renders ILs an ideal medium within the concept of “green solvent engineering”. In solvent extraction, ILs can act as extractants, co-extractants, or diluents. When functioning directly as extractants, the anionic moieties and functional groups of ILs can selectively coordinate with metal cations to achieve efficient separation. As co-extractants, ILs can participate in forming metal–ligand complexes or maintaining charge balance via ion-exchange processes. When used as diluents, ILs can replace the volatile and toxic organic solvents that are traditionally used in extraction systems, thereby reducing environmental risks.

Figure 10.

The cations and anions commonly used in ionic liquids.

The advantages of ILs in metal ion extraction are most evident in their high selectivity, environmental compatibility, applicability in high-salinity media, and recyclability. These properties highlight their significant potential in green separation technologies. Zheng et al. [] investigated the TBP–[Bmim][Nf2T] extraction system, focusing on changes in the water content of the organic phase during lithium extraction. They found that TBP and water form a 1:1 complex, and slope analysis revealed three potential coordination species with Li+: Li·2TBP·2H2O, Li·3TBP·H2O, and Li·4TBP. Molecular dynamics simulations confirmed that, during extraction, TBP gradually replaces water molecules in the Li+ hydration shell. The stability of the resulting complexes depends on the involvement of the IL anion [Nf2T]− (see Figure 11). Li et al. [] synthesized a functionalized IL, [Hmim][BTA], from 4,4,4-trifluoro-1-phenyl-1,3-butanedione (HBTA) and 1-hexyl-3-methylimidazolium chloride ([Hmim]Cl). The results showed that extending the cationic side chain effectively suppressed cation exchange into the aqueous phase, thus improving system stability and recyclability. Zhao et al. [] synthesized a functionalized IL comprising the tetrabutylphosphonium cation ([P4444]+) and deprotonated 2-thiophenoyltrifluoropropanone (TTA−). By immobilizing this IL within a three-dimensional mesoporous silica framework, leaching of the extractant was effectively prevented. The resulting composite exhibited excellent lithium selectivity across a wide pH range, achieving a lithium removal rate of 98.32% within 20 min. Table 1 summarizes commonly used IL-based extraction systems.

Figure 11.

The schematic diagram of the lithium-ion extraction mechanism of the TBP–[Bmim] [Nf2T] mixed system. Reprinted from ref. [].

Table 1.

Commonly used ionic liquid extraction system.

In summary, the structural tunability, high efficiency, and ability to replace conventional TBP–FeCl3 systems while reducing reliance on concentrated HCl make ILs a leading area of research for novel lithium extractants. However, the path towards their industrial deployment is still fraught with challenges, including complex synthesis routes, high costs, underdeveloped regeneration and recycling technologies, and the risk of cation leakage to the aqueous phase during ion exchange, which could have unforeseen environmental consequences. Future research should therefore leverage computational chemistry to design IL structures that have an enhanced affinity for Li+ and greater selectivity, thereby opening new pathways for the efficient and sustainable utilization of lithium from brine resources.

5. Adsorption Method

The adsorption method involves the enrichment of target ions (e.g., Li+) from aqueous solutions onto the solid phase at the solid–liquid interface through processes such as physical or chemical adsorption, or cation exchange. In the development of lithium resources from salt lake brines, the adsorption process typically comprises four fundamental steps: adsorption, washing, desorption, and acid treatment. Commonly used adsorbents include modified natural minerals, titanium-based lithium adsorbents, manganese-based lithium adsorbents, aluminum-based lithium adsorbents, antimonate-based adsorbents, and organic adsorbents []. Titanium-, manganese-, and aluminum-based lithium adsorbents have attracted the most attention in research and practical applications due to their structural and performance advantages []. Titanium- and manganese-based adsorbents are generally prepared using similar methods, whereby lithium salts and the relevant metal compounds are mixed at defined molar ratios and processed via co-precipitation, solid-state, or sol–gel methods to produce lithium-doped metal oxide precursors. Subsequent high-temperature calcination yields lithium-inserted composite oxides, after which the embedded lithium-ions are selectively leached using inorganic acids to generate vacant sites with strong affinity for Li+. However, this mechanism is not applicable to aluminum-based adsorbents. Aluminum-based lithium adsorbents—including Li/Al layered double hydroxides (LDHs)—do not rely on lithium insertion and acid leaching to create adsorption sites. Instead, their lithium selectivity originates from anion-exchange processes associated with the layered hydroxide structure. The LDH framework remains intact during synthesis, and lithium uptake occurs through ion exchange within the interlayer rather than through lattice extraction and reconstruction.

Titanium-, manganese-, and aluminum-based lithium adsorbents are collectively referred to as LIS. These materials are characterized by their high selectivity towards lithium-ions, excellent regeneration capability, and environmental compatibility, rendering them promising candidates for industrial applications []. However, their functional mechanisms differ depending on the host structure and composition. For manganese- and titanium-based ion sieves, the lithium recovery process typically proceeds via a proton exchange mechanism []. This distinction arises from the different framework structures and charge compensation behaviors of the metal–oxygen lattice. The performance of LIS adsorbents are the ion-sieving effect and selective coordination. For titanium-based LIS, lithium adsorption similarly follows a reversible proton exchange reaction within the Ti–O framework:

Using manganese-based spinel-type λ-MnO2 as an example, the process of removing lithium generates a large number of vacancies within the material’s lattice. These vacancies possess size-selective characteristics that enable the specific recognition of Li+, facilitating efficient adsorption. Lithium-ions diffuse into the material’s structural channels and undergo ion exchange with lattice cations, as described by the following typical reaction:

In contrast, aluminum-based LDH-type ion sieves operate through a chloride-mediated anion exchange mechanism, which can be expressed as:

This process is driven by crystal field stabilization energy (CFSE), whereby lithium-ions (Li+) exhibit high compatibility with octahedral oxygen vacancies. Importantly, the high Li+ selectivity of LIS is not solely governed by ionic size exclusion. While LIS materials can effectively reject most impurity cations such as Na+, K+, and Ca2+ through steric hindrance and framework-size matching, Mg2+ represents a notable exception where the separation mechanism fundamentally differs. Although Mg2+ has a smaller ionic radius than Li+, the decisive factor lies in the sharp contrast in their hydration enthalpies. Li+ possesses a much lower hydration enthalpy, enabling easier dehydration and rapid insertion into the lattice, whereas Mg2+ remains strongly hydrated, cannot shed its hydration shell, and is therefore energetically excluded from adsorption sites. This combined mechanism—size-based exclusion for monovalent/divalent cations and hydration-enthalpy–dominated selectivity for Mg2+—underpins the unique Li/Mg discrimination behavior of LIS materials [].

Despite their advantages, conventional LIS materials still suffer from structural instability and partial dissolution during cyclic operation. The causes of instability differ among various ion sieves. In manganese-based materials, lattice collapse often occurs due to Jahn–Teller distortion and Mn dissolution during redox cycling. For titanium-based sieves, the Ti–O framework is prone to hydrolysis under acidic desorption conditions, leading to the release of Ti4+. In aluminum-based systems, repeated chloride swing operations can result in partial reconstruction of the layered double hydroxide (LDH) structure or loss of chloride ions. These phenomena reduce the number of active sites and weaken the mechanical integrity of the adsorbent, thereby diminishing performance over time.

To overcome these limitations, a variety of optimization strategies have been suggested. Ma et al. used a solid-state reaction method to incorporate different metal dopants into titanium-based LIS and examined their impact on the performance of the material. The results showed that doping with W, Zr, and Ce significantly suppressed Ti dissolution. In particular, doping with W conferred remarkable improvements in both structural stability and lithium adsorption capacity, whereas doping with Fe and Mo tended to aggravate dissolution. Zhang et al. [] introduced boron into spinel-type Li1.6Mn1.6O4 (LMO) to promote preferential growth of the (100) crystal plane and suppress formation of the (110) plane. This modification enhanced structural stability, reduced Mn dissolution, and increased the lithium adsorption capacity to 42.6 mg·g−1. Wu et al. [] developed an inorganic carbon-supported H2TiO3 adsorbent via an in situ polymerization–synchronous transformation approach. In this process, Li2CO3 and TiO2 were polymerized in a resorcinol–formaldehyde system, followed by calcination at 973.15 K to form a low-disorder carbon support with dispersed active adsorption phases.

For titanium-based sieves, the most widely studied stoichiometries include layered Li2TiO3 and Li4Ti5O12, which after acid treatment yield H2TiO3 or H4Ti5O12 with abundant exchangeable H+ sites. Alternative forms such as TiO(OH)2-derived titanates and doped variants (e.g., W-, Zr-, or Ce-modified titanates) have also been reported to improve structural integrity and mitigate Ti4+ dissolution under regeneration conditions. Zhao et al. prepared Li/Al layered double hydroxide (LDH)-based composite hydrogels using a chitosan binder, which exhibited a lithium saturation capacity of 12.5 mg·g−1 at pH 6.5 and excellent regeneration and mechanical strength. The adsorption–desorption process in this system followed a chloride exchange mechanism, confirming the distinct behavior of aluminum-based ion sieves. In another study, Zhao et al. [] synthesized a cobalt-doped Li2TiO3 adsorbent through calcination, which was then integrated with a polysulfone matrix via electrospinning to produce fibrous composite adsorbents. Under optimized conditions, the material achieved a maximum lithium adsorption capacity of 60.79 mg·g−1. Following six consecutive adsorption–desorption cycles, the lithium desorption efficiency remained at 90.56%, with Ti dissolution maintained below 0.43%.

Lithium recovery from LIS adsorbents is typically achieved through an acid leaching or ion-exchange desorption process, in which protons or competing monovalent cations replace the inserted Li+ in the host lattice. According to the existing literature, mild inorganic acids such as HCl, H2SO4, or organic acids are commonly used to extract Li+ while minimizing dissolution of the host framework. For manganese-based and titanium-based ion sieves, the reversible H+/Li+ exchange mechanism enables efficient lithium stripping, whereas for aluminum-based LDH adsorbents, chloride-mediated anion exchange dominates the desorption process []. These distinct regeneration pathways determine cycle stability and strongly influence material degradation behavior.

The development of LIS adsorbents requires optimization across the “material–particle–system” hierarchy. At the material level, the crystal structure must be engineered to ensure high lithium selectivity and structural robustness. At the particle level, morphology control should balance mechanical strength and hydrodynamic performance. At the system level, process integration must reconcile efficiency with economic and environmental sustainability. A deeper understanding of the relationship between structure and function—as well as the mechanisms underlying instability—will be essential for guiding the rational design of next-generation ion-sieve adsorbents for lithium extraction.

6. Nanofiltration/Electrodialysis

The application of membrane separation technologies for lithium recovery from brines is a relatively recent development, representing a novel separation strategy. Initially developed for water softening and reducing total dissolved solids, nanofiltration (NF) membranes typically possess pore sizes of 0.5–5 nm [,], which lie between the pore sizes of ultrafiltration and reverse osmosis membranes. Due to their negatively charged surfaces and tunable material properties, NF membranes offer a balance of high water permeability and moderate operating pressures []. They exhibit preferential permeability towards monovalent ions while retaining divalent and multivalent ions, and they exhibit rejection exceeding 90%. In brine lithium extraction, NF enables the efficient separation of Li+ from coexisting ions, which is primarily governed by steric hindrance, Donnan exclusion, and dielectric effects. Steric hindrance occurs when the size of hydrated ions approaches that of the membrane pores, whereas Donnan exclusion arises from electrochemical potential differences caused by an unequal distribution of ions at the membrane–solution interface. The dielectric effect, associated with the lower dielectric constant within the membrane phase, increases the energy barrier to dehydration for multivalent ions, thereby effectively rejecting Mg2+ and enabling the selective separation of Li+ and Mg2+. In practical operations, NF is often combined with reverse osmosis to process brines with a high Mg/Li ratio (see Figure 12). The workflow typically involves solar evaporation to precipitate Na+ and K+, achieving preliminary lithium enrichment, followed by NF to remove Ca2+ and Mg2+, then reverse osmosis to further concentrate lithium, and finally the precipitation of lithium carbonate upon the addition of Na2CO3 []. Recently, hybrid processes such as membrane–adsorption coupling and nanofiltration systems incorporating 2D nanomaterials (e.g., graphene oxide or MXene-based layers) have attracted attention for their improved fouling resistance, tunable selectivity, and enhanced Li+ flux, offering promising directions for industrial application.

Figure 12.

Nanofiltration (NF)-reverse osmosis (RO) integrated treatment train for Li+ extraction from salt lake brine. Reprinted from ref. [].

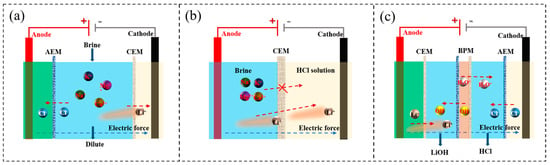

Electrodialysis (ED) relies on an applied electric field and alternately arranged cation exchange membranes (CEMs) and anion exchange membranes (AEMs) to drive directional ion migration (Figure 13a) []. Under an electric field, cations migrate through CEMs towards the cathode, while anions migrate through AEMs towards the anode, thus achieving selective ion separation. Two approaches are typically employed in lithium recovery. The first uses Li+-selective CEMs (see Figure 13b), which allow only Li+ to pass through to the concentrate compartment while retaining Mg2+ and Ca2+ in the diluate []. The second approach incorporates bipolar membranes (BPMs), which are composed of an anion-exchange layer, a cation-exchange layer and a hydrophilic polymer interface (Figure 13c). BPMs catalyze water dissociation into H+ and OH− under an electric field, enabling the in situ generation of lithium hydroxide within the enrichment compartment [].

Figure 13.

(a) Electrodialysis system; (b) Li+-selective membrane electrodialysis system; (c) bipolar membrane electrodialysis system.

NF and ED are progressing from laboratory studies towards industrial deployment as green and efficient technologies. However, there are still some key challenges to overcome, including ensuring membrane stability, reducing energy demand, controlling costs, and integrating processes. Future research should focus on developing graphene oxide, ion-imprinted, and covalent organic framework (COF)-based membranes with improved mechanical durability and anti-fouling performance, as well as exploring process integration with adsorption or electrochemical modules for hybrid lithium recovery. In addition, techno-economic analysis and lifecycle assessment are needed to evaluate scalability and sustainability in real brine environments [].

7. Electrochemical Method

Electrochemical lithium extraction involves applying electrochemical principles to drive the selective migration, adsorption, and release of lithium-ions between functional electrodes using an external electric field. This process achieves the separation and enrichment of lithium-ions from coexisting ions. This method offers several advantages, such as short reaction times, low energy consumption, environmental compatibility, and high adaptability to different conditions. These features make it a promising method for brine-based lithium recovery. This approach has already been validated in several salt lake brine systems [].

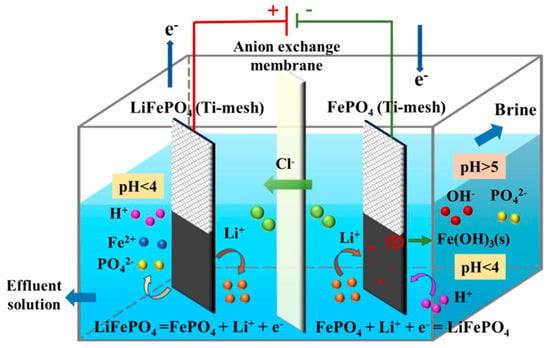

As shown in Figure 14, the core mechanism involves the selective adsorption/desorption or intercalation/deintercalation of Li+ by electrode materials. This process is primarily driven by the electrochemical potential difference and the specific interactions between the electrode and the lithium-ions []. A detailed discussion of electrochemical cell configurations is necessary to fully understand the efficiency of this method. Common configurations include single-compartment cells, two-compartment cells, and flow-through systems. In single-compartment cells, lithium-ions are exchanged directly between the electrodes in a single chamber, while two-compartment systems separate the cathode and anode with a conductive membrane. Flow-through cells involve the continuous circulation of electrolyte through an electrode bed, enhancing contact between lithium-ions and electrode materials. The electrochemical swing process, a key feature of this method, involves the alternating cycles of lithium-ion insertion and removal in response to applied electric fields. In this process, lithium-ions are initially intercalated into the electrode material under a positive bias and later released during the reverse cycle, when the bias is switched. This back-and-forth movement is highly dependent on the design of the electrodes and the applied voltage, with the potential difference driving the migration of lithium-ions into and out of the material’s structure.

Figure 14.

Schematic diagram of lithium extraction mechanism by electrochemical method (electrode LiFePO4/FePO4). Reprinted from ref. [].

Depending on the interaction mechanism between the electrode materials and Li+, the process of electrochemical lithium extraction can be broadly classified into four categories. Intercalation-type electrodes operate through reversible insertion reactions, enabling the uptake and release of lithium-ions. Representative materials include layered oxides (e.g., LiCoO2), spinel structures (e.g., Li4TiO12), olivine structures (e.g., LiFePO4), and Prussian blue analogs [,]. Ion-sieve electrodes exploit crystal lattice selectivity towards Li+ based on size and charge discrimination. Representative materials include LiMn2O4, λ-MnO2, and H1.6Mn1.6O4 [,]. Electrical double-layer capacitive electrodes primarily achieve lithium enrichment via electrostatic adsorption, using materials such as activated carbon, graphene, and carbon nanotubes. In contrast, pseudocapacitive electrodes rely on Faradaic redox processes for efficient lithium storage and release. Typical examples include conducting polymers such as polypyrrole and polyaniline [,].

In practice, a wide range of anode–cathode combinations have been adopted depending on the extraction mechanism. For intercalation-based systems, lithium-selective materials such as LiFePO4, λ-MnO2, or H2TiO3 typically serve as the cathode, while inert conductors such as platinum foil, graphite plates, activated carbon felt, or titanium mesh act as the anode [,]. In ion-sieving systems, proton-rich phases (e.g., H1.6Mn1.6O4 or H2TiO3) function as the active lithium-uptake cathode, paired with counter electrodes including Pt, carbon fabric, or RuO2-coated Ti. For capacitive and pseudocapacitive systems, carbon-based electrodes (e.g., activated carbon cloth, graphene composites, carbon nanotube mats) serve as either the anode or cathode depending on the direction of ion movement. Redox-active polymer electrodes (e.g., polypyrrole, polyaniline) may also be used on either side to enhance charge storage and lithium recovery efficiency [,]. These diverse electrode pairings enable flexible optimization of selectivity, stability, and energy consumption across different electrochemical lithium extraction architectures.

Despite substantial progress at the laboratory scale, there are still several challenges to overcome before electrochemical lithium extraction can be implemented on an industrial scale. One of the main challenges is the degradation of electrode materials under high-salinity brine conditions, which leads to a loss of activity and selectivity over time. Furthermore, the fabrication of high-performance electrodes often involves energy-intensive or complex processes, such as high-temperature sintering or chemical deposition, limiting their scalability. In addition, achieving high lithium recovery efficiencies requires maintaining relatively large potential differences, which inevitably leads to increased energy consumption. Therefore, balancing high selectivity and recovery efficiency with minimized energy demand is a critical challenge in advancing the industrial application of electrochemical lithium extraction.

8. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

In recent years, significant progress has been made in the extraction of lithium from brines through solvent extraction, adsorption, membrane separation, electrodialysis, and electrochemical methods. However, large-scale industrial implementation still faces considerable technological challenges. Among the existing approaches, solvent extraction and adsorption have reached pilot and semi-industrial stages, whereas membrane and electrochemical technologies are still in early demonstration phases with limited large-scale validation. Key bottlenecks such as reagent cost, membrane fouling, brine variability, and secondary waste generation continue to hinder industrial deployment. Therefore, future development must focus not only on scientific innovation but also on techno-economic feasibility and environmental sustainability.

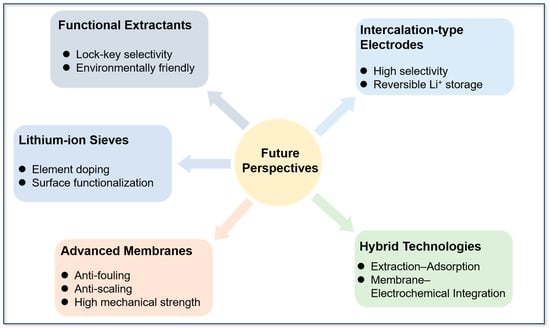

Future research directions may be as follows (see Figure 15): Firstly, the rational design and development of new functional extractants with specific identification ability, controllable cost, and environmental friendliness should be prioritized. Particular focus should be placed on developing highly selective extractants with a ‘lock-key’ effect for Li+, such as hydrophobic diketo extractants, deep eutectic solvents, functionalized ionic liquids, coronoid ether derivatives, and polydentate ligands. Secondly, element doping (e.g., W, Zr, Ce, Co, and B) and surface functionalization should be employed to reinforce the structural stability, anti-deactivation capacity, and Li+ selectivity of lithium-ion sieves under high salinity conditions, thereby enabling their efficient cyclic use. Thirdly, developing advanced membranes that have superior anti-fouling and anti-scaling properties, an extended lifetime, and high mechanical strength is essential to enhance the separation efficiency of nanofiltration and electrodialysis in complex brine systems and facilitate their integration into scalable processes. Fourthly, designing novel intercalation-type electrode materials that exhibit high selectivity, structural durability, and reversible Li+ storage capacity will be crucial for improving electrochemical methods.

Figure 15.

Future perspectives for lithium extraction from brines.

To better guide practical deployment, priority should be given to hybrid technologies with higher technology readiness levels (TRL), such as extraction–adsorption coupling and membrane–electrochemical integration, which show near-term scalability and reduced environmental footprint. Future work should also address key R&D gaps, including reagent regeneration, long-term system stability, and process automation for continuous operation. Furthermore, future efforts should actively explore synergistic strategies, such as extraction–adsorption coupling, membrane–extraction integration, or membrane concentration combined with electrochemical separation. These could be further complemented by lithium recovery assisted by pretreatment with the simultaneous valorization of by-products from post-lithium brines. This would enable the cascade utilization of brine resources. Continued breakthroughs in this area will foster the efficient, clean, and sustainable development of lithium resources, while also providing a solid technological foundation for mitigating global imbalances in lithium supply and demand, and advancing the transition towards a green energy future.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.W. and T.D.; methodology, H.W.; software, H.W.; validation, H.W. and Z.Z.; formal analysis, H.W.; investigation, H.W.; resources, Y.C.; data curation, Y.C.; writing—original draft preparation, H.W.; writing—review and editing, T.D.; visualization, Z.Z.; supervision, Y.C.; project administration, Y.C.; funding acquisition, Y.C. and T.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Education Department of Jiangxi Province, China [grant number GJJ2401705, GJJ190892 and GJJ201719].

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

All authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as potential conflicts of interest.

References

- Tang, X.; Chen, G.; Mo, Z.; Ma, D.; Wang, S.; Wen, J.; Gong, L.; Zhao, L.; Huang, J.; Huang, T.; et al. Controllable two-dimensional movement and redistribution of lithium ions in metal oxides. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 2888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, S.; Wang, Y.; Pan, H.; He, P.; Zhou, H. Lithium extraction from low-quality brines. Nature 2024, 636, 309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Geological Survey. Mineral Commodity Summaries; U.S. Geological Survey: Reston, VA, USA, 2023.

- Ettehadi, A.; Chuprin, M.; Mokhtari, M.; Gang, D.N.; Wortman, P.; Heydari, E. Geological Insights into Exploration and Extraction of Lithium from Oilfield Produced-Water in the USA: A Review. Energy Fuels 2024, 38, 10517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Wang, Q.; Wang, Y.H.; Yun, R.P.; Xiang, X. Recent advances in magnesium/lithium separation and lithium extraction technologies from salt lake brine. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2021, 256, 117807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, A.; Benson, S.M.; Chueh, W.C. Critically assessing sodium-ion technology roadmaps and scenarios for techno-economic competitiveness against lithium-ion batteries. Nat. Energy 2025, 10, 404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, A.L.; Fuchs, E.R.H.; Karplus, V.J.; Michalek, J.J. Electric vehicle battery chemistry affects supply chain disruption vulnerabilities. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 2143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrew, Z.; Haddad, L.H. Bilen Akuzum, Garrett Pohlman, Jean-François Magnan & Robert Kostecki, How to make lithium extraction cleaner, faster and cheaper—In six steps. Nature 2023, 616, 245. [Google Scholar]

- Neukampf, J.; Ellis, B.S. Lithium loss from pegmatites controlled by country rock temperature. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazir, M.K.; Dyer, L.; Tadesse, B.; Albijanic, B.; Kashif, N. Effect of calcination on coarse gangue rejection of hard rock lithium ores. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 12963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Chen, M.; Fang, X.; Wu, L. Fabrication and application of inorganic hollow spheres. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2011, 40, 5472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ooi, K.; Sonoda, A.; Makita, Y.; Chitrakar, R.; Tasaki-Handa, Y.; Nakazato, T. Recovery of lithium from salt-brine eluates by direct crystallization as lithium sulfate. Hydrometallurgy 2017, 174, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Hu, Y.H.; Sun, N.; Khoso, S.A.; Wang, L.; Sun, W. A novel precipitant for separating lithium from magnesium in high Mg/Li ratio brine. Hydrometallurgy 2019, 187, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.J.; Wang, Y.Y.; Duan, W.J.; Du, C.C.; Tian, S.C.; Ren, Z.Q.; Zhou, Z.Y. Selective extraction of lithium ions from salt lake brines using a tributyl phosphate-sodium tetraphenyl boron-phenethyl isobutyrate system. Desalination 2023, 555, 116543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Duan, W.; Li, R.; Zhang, F.; Tian, S.; Ren, Z.; Zhou, Z. One-step synthesis of heteropolyacid ionic liquid as co-extraction agent for recovery of lithium from aqueous solution with high magnesium/lithium ratio. Desalination 2023, 548, 116261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.Q.; Zhang, X.J.; Liu, K.Y.; Liu, X.; Gong, Y.F.; Peng, H.; Qi, W. Convenient synthesis of granulated Li/Al-layered double hydroxides/chitosan composite adsorbents for lithium extraction from simulated brine with a high Mg/Li ratio. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 501, 157780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Yang, M.; Xu, C.; Wang, Q.; He, C.; Liu, C.; Lai, B. Insight into the synergistic mechanism of Co and N doped titanium-based adsorbents for liquid lithium extraction. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 480, 147631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afsar, N.U.; Shehzad, M.A.; Irfan, M.; Emmanuel, K.; Sheng, F.; Xu, T.; Ren, X.; Ge, L.; Xu, T. Cation exchange membrane integrated with cationic and anionic layers for selective ion separation via electrodialysis. Desalination 2019, 458, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhao, X.; Li, Y.; Li, X.L.; Wang, J.; Yang, H.Y. Restraining Lattice Distortion of LiMn2O4 Facilitates Fluidic Electrochemical Lithium Extraction from Seawater. Nano Lett. 2025, 25, 995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mojid, M.R.; Lee, K.J.; You, J. A review on advances in direct lithium extraction from continental brines: Ion-sieve adsorption and electrochemical methods for varied Mg/Li ratios. Sustain. Mater. Technol. 2024, 40, e00923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleem, U.; Wilhelms, A.; Sottmann, J.; Knuutila, H.K.; Bandyopadhyay, S. Direct lithium extraction (DLE) methods and their potential in Li-ion battery recycling. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 361, 131315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Neek-Amal, M.; Sun, C. Advances in Two-Dimensional Ion-Selective Membranes: Bridging Nanoscale Insights to Industrial-Scale Salinity Gradient Energy Harvesting. ACS Nano 2024, 18, 12610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Li, Q.; Lu, C.; Tan, L.; Xia, D.; Dong, L.; Zhou, C. Separation and Recovery of Cathode Materials from Spent Lithium Iron Phosphate Batteries for Sustainability: A Comprehensive Review. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2024, 63, 13945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papale, M.; Lo Giudice, A.; Conte, A.; Rizzo, C.; Rappazzo, A.C.; Maimone, G.; Caruso, G.; La Ferla, R.; Azzaro, M.; Gugliandolo, C.; et al. Microbial Assemblages in Pressurized Antarctic Brine Pockets (Tarn Flat, Northern Victoria Land): A Hotspot of Biodiversity and Activity. Microorganisms 2019, 7, 333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Tang, X.; Qing, D.; Li, J.; Wang, H. Research progress of technology of lithium extraction. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 359, 130561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siekierka, A.; Bryjak, M.; Razmjou, A.; Kujawski, W.; Nikoloski, A.N.; Dumee, L.F. Electro-Driven Materials and Processes for Lithium Recovery—A Review. Membranes 2022, 12, 343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yong, M.; Yang, Y.; Sun, L.; Tang, M.; Wang, Z.; Xing, C.; Hou, J.; Zheng, M.; Chui, T.F.M.; Li, Z.; et al. Nanofiltration Membranes for Efficient Lithium Extraction from Salt-Lake Brine: A Critical Review. ACS Env. Au 2025, 5, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knapik, E.; Rotko, G.; Marszałek, M. Recovery of Lithium from Oilfield Brines—Current Achievements and Future Perspectives: A Mini Review. Energies 2023, 16, 6628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baudino, L.; Santos, C.; Pirri, C.F.; La Mantia, F.; Lamberti, A. Recent Advances in the Lithium Recovery from Water Resources: From Passive to Electrochemical Methods. Adv. Sci. 2022, 9, e2201380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hano, T.; Matsumoto, M.; Ohtake, T.; Egashir, N.; Hori, F. Recovery Of Lithium from Geothermal Water by Solvent Extraction Technique. Solvent Extr. Ion Exch. 1992, 10, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crusciol, C.A.C.; de Arruda, D.P.; Fernandes, A.M.; Antonangelo, J.A.; Alleoni, L.R.F.; Nascimento, C.; Rossato, O.B.; McCray, J.M. Methods and extractants to evaluate silicon availability for sugarcane. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertin, P.N.; Crognale, S.; Plewniak, F.; Battaglia-Brunet, F.; Rossetti, S.; Mench, M. Water and soil contaminated by arsenic: The use of microorganisms and plants in bioremediation. Env. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2022, 29, 9462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikkhah, H.; Di Maria, A.; Granata, G.; Beykal, B. Sustainable process design for lithium recovery from geothermal brines using chemical precipitation. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2025, 212, 107980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, C.; Zheng, M.; Zhang, Y.; Xing, E.; Gui, B. Adsorption performance and mechanism of Li+ from brines using lithium/aluminum layered double hydroxides-SiO2 bauxite composite adsorbents. Front. Chem. 2023, 11, 1265290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, L.; Zhang, C.; Kim, S.; Hatton, T.A.; Mo, H.; Waite, T.D. Lithium recovery using electrochemical technologies: Advances and challenges. Water Res. 2022, 221, 118822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Battaglia, G.; Berkemeyer, L.; Cipollina, A.; Cortina, J.L.; Fernandez de Labastida, M.; Lopez Rodriguez, J.; Winter, D. Recovery of Lithium Carbonate from Dilute Li-Rich Brine via Homogenous and Heterogeneous Precipitation. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2022, 61, 13589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.F.; Geng, X.; Deng, H.N.; Jiang, Z.J.; Xia, B.Z.; Yang, L.R.; Li, Z. Comparative Study of Four Acidic Extractants as Modifiers in the TBP/FeCl3 Solvent Extraction System for Lithium and Magnesium Separation. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2024, 63, 4897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, C.; Liu, C.; Wang, J.; Khan, A.; Zhong, H.; He, Z. Selective separation of lithium from the hydrochloric acid leachate of lithium ores via the extraction system containing TBP-FeCl3. Desalination 2024, 583, 117677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Xing, H.; Rong, M.; Li, Z.; Wei, X.; Chen, C.; Liu, H.; Yang, L. Quantum chemical calculation assisted efficient lithium extraction from unconventional oil and gas field brine by β-diketone synergic system. Desalination 2023, 565, 116890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, J.Y.; Yang, F.D.; He, J.T.; Du, J.H.; Dong, B.; Ma, X.H.; Li, J.X. A highly efficient ternary extraction system with tributyl phosphate/crown ether/NaNTf2 for the recovery of Li+ from low-grade salt lakes. Desalination 2024, 583, 117702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, J.; He, J.; Pei, H.; Du, J.; Ma, X.; Li, J. A remarkable improved Li+/Mg2+ selectivity and Li+ recovery simultaneously by adding crown ether to tributyl phosphate-ionic liquid extraction system as co-extractant. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2024, 335, 126162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, G.Q.; Zhang, X.H.; Hubach, T.; Chen, B.H.; Held, C. Highly efficient lithium extraction from magnesium-rich brines with ionic liquid-based collaborative extractants: Thermodynamics and molecular insights. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2024, 286, 119682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Numedahl, N.; Jiang, C. Direct lithium extraction from Canadian oil and gas produced water using functional ionic liquids—A preliminary study. Appl. Geochem. 2024, 172, 106126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Binnemans, K. Opposite selectivities of tri-n-butyl phosphate and Cyanex 923 in solvent extraction of lithium and magnesium. AIChE J. 2021, 67, e17219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Qin, W.; Liu, Y.; Fei, W. Extraction Equilibria of Lithium with Tributyl Phosphate in Kerosene and FeCl3. J. Chem. Eng. Data 2011, 57, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, H.; Li, Z.; Zhang, J.; Liu, W.S.; Zhu, Z.W.; Wang, L.N.; Qi, T. Combining Selective Extraction and Easy Stripping of Lithium Using a Ternary Synergistic Solvent Extraction System through Regulation of Fe Coordination. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2020, 8, 1971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, W.; Wang, Y.; Li, R.; Ren, Z.; Zhou, Z. Selective extraction of lithium from high magnesium/lithium ratio brines with a TBP–FeCl3–P204–kerosene extraction system. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2024, 328, 125066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.P.; Cui, J.J.; Liu, C.L.; Yuan, F.; Guo, Y.F.; Deng, T.L. Separation of magnesium from high Mg/Li ratio brine by extraction with an organic system containing ionic liquid. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2021, 229, 116019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, D.; Cui, B.; Li, L.J.; Xu, M.; Zhang, Y.Z.; Peng, X.W.; Zhang, L.C.; Song, F.G.; Ji, L.M. Removal of calcium and magnesium from lithium concentrated solution by solvent extraction method using D2EHPA. Desalination 2020, 479, 114306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.K.; Zhang, J.; Su, H.; Qi, T.; Wang, L.N. Recovery of Lithium from the Mother Solution of Lithium Precipitation in Lithium Ore Processing. Chin. J. Rare Met. 2020, 46, 67. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, J.X.; Chen, H.; Yu, J.G. Selective lithium recovery from lithium precipitation mother liquor by using a diketone-based solvent. Desalination 2024, 591, 117999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, Z.H.; Xu, T.S.; Zhang, L.C.; Ji, L.M.; Li, L.J. Mechanism and process study of lithium extraction by 2-ethylhexyl salicylate extraction system. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 446, 141351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Wenzel, M.; Steup, J.; Schaper, G.; Hennersdorf, F.; Du, H.; Zheng, S.; Lindoy, L.F.; Weigand, J.J. 4-Phosphoryl Pyrazolones for Highly Selective Lithium Separation from Alkali Metal Ions. Chemistry 2022, 28, e202103640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Tanjedrew, N.; Wenzel, M.; Royla, P.; Du, H.; Kiatisevi, S.; Lindoy, L.F.; Weigand, J.J. Selective Separation of Lithium, Magnesium and Calcium using 4-Phosphoryl Pyrazolones as pH-Regulated Receptors. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2023, 62, e202216011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Rong, M.; Sun, L.-B.; Zhao, Y.; Xing, H.; Yang, L. Benzo-12-crown-4 and β-diketone bi-functionalized ionic liquids for highly selective lithium extraction from alkaline solution. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 497, 154341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fritz, P.W.; Ashirov, T.; Coskun, A. Porous organic polymers with heterocyclic crown ethers for selective lithium-ion capture. Chem 2024, 10, 2207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torrejos, R.E.C.; Nisola, G.M.; Song, H.S.; Limjuco, L.A.; Lawagon, C.P.; Parohinog, K.J.; Koo, S.; Han, J.W.; Chung, W.J. Design of lithium selective crown ethers: Synthesis, extraction and theoretical binding studies. Chem. Eng. J. 2017, 326, 921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Y.; Ge, T.; Xu, L.; Wang, L.; He, J.; Zhou, X.; Tian, Y.; Zhao, Z. A fundamental study on selective extraction of Li+ with dibenzo-14-crown-4 ether: Toward new technology development for lithium recovery from brines. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 310, 114705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, T.Y.; Mao, L.J.; Li, X.; Ye, C.S.; Zhang, P.R.; Sun, W.; Sun, J.H. Elucidating the Mechanism of Lithium Ion Extraction in a Tributyl Phosphate-Ionic Liquid Mixed System from the Perspective of Water Coordination. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2024, 12, 18373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.J.; Wang, Y.Y.; Chen, L.L.; Duan, W.J.; Ren, Z.Q.; Zhou, Z.Y. Ionic liquid for selective extraction of lithium ions from Tibetan salt lake brine with high Na/Li ratio. Desalination 2024, 574, 117274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Xing, H.; Zhang, J.; Liu, Q.; Wu, H.; Chen, C.; Liu, H.; Yang, L. β-diketone-based mesoporous ionogel for high-efficiency lithium adsorption. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 352, 128065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, C.L.; Jia, Y.Z.; Zhang, C.; Liu, H.; Jing, Y. Extraction of lithium from salt lake brine using room temperature ionic liquid in tributyl phosphate. Fusion Eng. Des. 2015, 90, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, C.L.; Jing, Y.; Xiao, J.; Wang, X.Q.; Yao, Y.; Jia, Y.Z. Solvent extraction of lithium from aqueous solution using non-fluorinated functionalized ionic liquids as extraction agents. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2017, 172, 473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, C.L.; Jing, Y.; Xiao, J.; Wang, X.Q.; Jia, Y.Z. Liquid-liquid extraction of lithium using novel phosphonium ionic liquid as an extractant. Hydrometallurgy 2017, 169, 314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.C.; Liu, G.W.; Wang, J.F.; Cui, L.; Chen, Y.M. Recovery of lithium from alkaline brine by solvent extraction with functionalized ionic liquid. Fluid Phase Equilibria 2019, 493, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.F.; Yang, S.C.; Zhang, X.F.; Wang, Y.L.; Wang, D.G.; Li, W.C.; Ashraf, M.A.; Park, A.H.A.; Li, X.C. Extraction Mechanism of Lithium from the Alkali Solution with Diketonate-Based Ionic Liquid Extractants. Energy Fuels 2020, 34, 11581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, J.Y.; Ma, X.H.; Ji, W.H.; Li, Q.; He, B.Q.; Cui, Z.Y.; Liang, X.P.; Yan, F.; Li, J.X. Unveiling the mechanism of liquid-liquid extraction separation of Li/Mg using tributyl phosphate/ionic liquid mixed solvents. J. Mol. Liq. 2022, 365, 120080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Lu, H.; Fei, P.; Yang, L. Development Trend of Global Research in the Field of Lithium Extraction from Salt Lake Brine. J. Salt Lake Res. 2025, 32, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marthi, R.A.H.; Gadikota, G.; Smith, Y.R. On the Structure and Lithium Adsorption Mechanism of Layered H2TiO3. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13, 8361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, G.; Wang, M.; Hill, G.T.; Zou, S.; Liu, C. Defining the challenges of Li extraction with olivine host: The roles of competitor and spectator ions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2022, 119, e2200751119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Xing, H.; Meng, Q.; Liu, Q.; Liu, H.; Yang, L. Facets regulation of Li1.6Mn1.6O4 by B-doping to enable high stability and adsorption capacity for lithium extraction. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2024, 348, 127739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]