Abstract

Aiming at the drawbacks of the classic CoCrFeNi high-entropy alloy (HEA)—low room-temperature strength and softening above 600 °C, which fail to meet strict material requirements in high-end fields like aerospace—this study used the vacuum hot-pressing sintering process to prepare CoCrFeNiTax HEAs (x = 0, 0.5, 1.0, 1.5, 2.0 atom, designated as H4, Ta0.5, Ta1.0, Ta1.5, Ta2.0, respectively). This process effectively inhibits Ta segregation (a key issue in casting) and facilitates the presence uniform microstructures with relative density ≥ 96%, while this study systematically investigates a broader Ta content range (x = 0–2.0 atom) to quantify phase–property evolution, differing from prior works focusing on limited Ta content or casting/spark plasma sintering (SPS). Via X-ray diffraction (XRD), scanning electron microscopy–energy-dispersive spectroscopy (SEM-EDS), microhardness testing, and room-temperature compression experiments, Ta’s regulatory effect on the alloy’s microstructure and mechanical properties was systematically explored. Results show all alloys have a relative density ≥ 96%, verifying the preparation process’s effectiveness. H4 exhibits a single face-centered cubic (FCC) phase. Ta addition transforms it into a “FCC + hexagonal close-packed (HCP) Laves phase” dual-phase system. Mechanically, the alloy’s inner hardness (reflecting the intrinsic property of the material) increases from 280 HV to 1080 HV, the yield strength from 760 MPa to 1750 MPa, and maximum fracture strength reaches 2280 MPa, while plasticity drops to 12%. Its strengthening mainly comes from the combined action of Ta’s solid-solution strengthening (via lattice distortion hindering dislocation motion) and the Laves phase’s second-phase strengthening (further inhibiting dislocation slip).

1. Introduction

In high-end fields such as aerospace engines, nuclear reactors, and deep-sea exploration equipment, structural materials are required to sustain complex service loads (including high temperature, high pressure, corrosion, and impact) for a long time, posing severe challenges to their comprehensive performance in terms of “strength-plasticity-stability”. Traditional alloys (e.g., nickel-based superalloys, austenitic stainless steels) take single or dual elements as the matrix; the limitations in their composition design make it difficult to achieve synergistic optimization across multiple performance dimensions—high-strength alloys are often accompanied by plastic loss, while high-plasticity alloys cannot meet the load-bearing requirements.

In 2004, Yeh’s team [1] and Cantor’s team [2] broke through the traditional alloy design paradigm and proposed the concept of “High-Entropy Alloys”. By mixing five or more principal elements in equiatomic or near-equiatomic ratios, HEAs exhibit comprehensive performance far surpassing that of traditional alloys, relying on four core effects: the high-entropy effect (inhibiting the formation of a single phase), slow diffusion effect (reducing element segregation), lattice distortion effect (enhancing solid-solution strengthening), and cocktail effect (enabling performance customization). For instance, their room-temperature tensile strength can reach 1.5 GPa (with an elongation exceeding 20%), and the high-temperature oxidation resistance temperature exceeds 1000 °C [3,4,5,6]. Thus, HEAs have become a core research direction for next-generation high-performance structural materials.

The CoCrFeNi high-entropy alloy (HEA), also known as the Cantor alloy, is a typical face-centered cubic (FCC) structured HEA [7]. It exhibits excellent comprehensive properties due to its single solid-solution microstructure: its elongation at room temperature can reach over 50%, it maintains good toughness even in low-temperature environments, and the incorporation of Cr endows it with outstanding corrosion resistance under corrosive conditions such as marine and chemical engineering scenarios, making it a potential candidate material for applications including low-temperature seals and lightweight marine components [8,9,10,11]. Beyond its room-temperature performance, this alloy also demonstrates significant service potential in medium-to-high temperature environments: studies have shown that its wear rate remains stably below 4 × 10−4 mm3/Nm within the temperature range from room temperature to 800 °C [12], and a continuous and dense Cr2O3-Al2O3 composite oxide layer forms on its surface after high-temperature oxidation, which effectively inhibits the diffusion of oxygen into the matrix [13]; additionally, by regulating the grain size (refined to 50–100 nm), the alloy can achieve a balance between ballistic resistance and plasticity, exhibiting application value in the field of lightweight protection [14].

However, the yield strength of pure CoCrFeNi alloy is generally below 400 MPa, and it decreases rapidly with increasing temperature (the strength decreases by more than 30% at 600 °C), making it difficult to meet the high-strength requirements of applications such as aero-engine blades and high-temperature dies [15,16,17]. For this reason, introducing refractory elements (e.g., Ta, W, Nb, Mo, V, etc.) for compositional modification has become a key strategy to enhance the strength of this alloy system. Owing to their large atomic radii and high melting points, refractory elements not only induce significant lattice distortion through solid solution (e.g., the atomic radius of Ta is 1.46 Å, with a difference of over 15% from that of matrix elements such as Co and Cr) to increase the resistance to dislocation motion [18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26], but also form high-hardness second phases (e.g., Laves phase, intermetallic compounds) with matrix elements. Through the combined action of “solid solution strengthening + second-phase strengthening”, the overall strength of the alloy is improved. For instance, Huo et al. [18] found that after adding 0.5 mol of Ta to the CoCrFeNi alloy, the alloy transformed from a single FCC phase to a dual-phase structure of FCC + Laves phase, with the yield strength increased to 920 MPa, 1.3 times higher than that of the pure alloy; Jiang et al. [23], by introducing Ta, increased the high-temperature strength retention rate of the CoCrFeNiTax alloy at 600 °C to 85%, significantly improving its high-temperature service performance. However, most of the above studies adopt arc melting or induction melting processes. Due to the melting-point difference of over 1400 °C between Ta and elements such as Co and Fe, severe composition segregation (e.g., Ta-enriched regions and Ta-depleted regions) is prone to occur during the casting process, resulting in poor microstructural uniformity and making it difficult to accurately establish the “composition-microstructure-performance” relationship.

Compared with casting processes, powder metallurgy technologies (e.g., spark plasma sintering, vacuum hot-pressing) can achieve low-temperature rapid sintering in a vacuum/inert atmosphere through the “powder mixing-pressurization sintering” process. On the one hand, the large specific surface area of powder particles can promote uniform diffusion of elements, significantly inhibiting Ta segregation. On the other hand, grain growth is inhibited during the sintering process, enabling the formation of micron-scale fine-grained microstructures (usually with grain size < 10 μm) and further improving alloy performance through grain refinement strengthening [27,28]. Existing studies have shown that the relative density of Ta-containing HEAs prepared by powder metallurgy can reach more than 98%, and their microstructural uniformity is much better than that of cast samples [28]; thus, this technology is selected as the preferred process in this study.

Based on the above research status and requirements, this study prepares CoCrFeNiTax (x = 0, 0.5, 1.0, 1.5, 2.0 atom) HEAs using the vacuum hot-pressing sintering process, and systematically investigates the influence of Ta content on the microstructure and mechanical properties of the alloys. The research results can enrich the theoretical understanding of phase evolution and strengthening mechanisms of HEAs, provide an experimental basis for the preparation of refractory element-doped HEAs via powder metallurgy, and offer references for the design of high-performance structural materials in fields such as aerospace and energy equipment.

2. Experimental Materials and Methods

2.1. Alloy Preparation

In this study, CoCrFeNiTax HEAs were fabricated via the powder metallurgy process, which combines mechanical alloying and vacuum hot-pressing sintering. Raw metal powders of Co, Cr, Fe, Ni, and Ta with a purity higher than 99.9 wt.% and an average particle size smaller than 75 μm, provided by Beijing Guanjinli New Material Technology Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China), were used as starting materials. Mechanical alloying was performed using a DECO planetary horizontal ball mill (DECO-PBM-H-0.4L, Deke Instrument Equipment Co., Ltd., Changsha, China) to prepare HEA powders. 316L stainless steel ball milling jars and grinding balls were used. The grinding balls had diameters of 10 mm and 5 mm, with a mass ratio of 1:1 between the two sizes. During the ball milling process, the ball-to-powder ratio was set to 10:1, and the system was purged with high-purity argon gas for 5 min to isolate it from air. First, dry milling was conducted at a rotational speed of 300 rpm for 45 h; subsequently, 10 mL (about 10% of the powder) of anhydrous ethanol was added as a process control agent (PCA), followed by wet milling for another 5 h. After that, the mixed powders were placed in a vacuum drying oven and dried at 50 °C for 48 h. Following sieving, CoCrFeNiTax HEA powders with a particle size smaller than 75 μm were obtained.

Mechanically alloyed powders were sintered using a ZT-25-20YVHP vacuum hot-pressing furnace (Shanghai Chenhua Technology Co., Ltd, Shanghai, China). Before the experiment, the aforementioned alloy powders were loaded into a high-purity graphite mold that had been preheated to 50~60 °C and coated with cubic boron nitride (CBN). The CBN coating exhibits high chemical stability and can effectively isolate the direct contact between graphite and alloy powders, thereby reducing the carbon diffusion rate from the mold to the alloy during sintering. The graphite mold was placed into the furnace chamber, which was first evacuated to a vacuum degree of 5 × 10−2 Pa. Then, the furnace was heated at a heating rate of 15 °C·min−1, while an oil pressure of 50 MPa was applied simultaneously. When the furnace temperature reached 950 °C, this temperature was maintained for 2 h. Once the furnace temperature cooled down to 500 °C, the application of pressure was stopped; the cylindrical sintered samples (with dimensions of Φ12.5 mm × 6 mm) were taken out when the temperature further decreased to 150 °C. The samples were cut into disk-shaped specimens with a thickness of 3 mm via wire electrical discharge machining (WEDM) for XRD testing. To eliminate potential interference from surface carbon diffusion (from the graphite mold), the disks were sequentially ground with 1200#, 1500#, and 2000# SiC sandpapers, followed by fine polishing with 1 μm diamond polishing paste—this process removed a total of ~50–100 μm of surface material. Combined with the CBN coating isolation (Section 2.2) and short sintering duration (2 h at 950 °C), which weakens carbon diffusion, this surface removal ensures the XRD test region corresponds to the inner matrix without carbon contamination.

2.2. Density Measurement

After each HEA was polished and wax-sealed, the measured density (ρm) was tested using Archimedes’ principle. The measuring medium was absolute ethanol (99.7 wt.%), with a density (ρ0) of 0.79 g·cm−3. The measured density of each CoCrFeNiTax alloy can be calculated via Equation (1):

In Equation (1), m0 denotes the mass of a single alloy sample in air before wax-sealing; m1 represents the mass of the same wax-sealed sample in air; and m2 stands for the mass of the wax-sealed sample when immersed in absolute ethanol. All sample masses were measured using an electronic balance with an accuracy of 0.1 mg. The theoretical density (ρt) of each bulk HEA is computed using Equation (2):

In Equation (2), xi is the atomic percentage of the i-th constituent element in the alloy, and ρi is the density of that i-th constituent element. The relative density (D) of each bulk CoCrFeNiTax alloy sample is calculated through Equation (3):

2.3. Microstructure Characterization

The phase composition of the alloys was characterized using a Bruker-D8 Advance X-ray diffractometer (XRD) (Billerica, MA, USA) with Cu-Kα radiation (wavelength λ = 1.54056 Å). The XRD testing parameters were set as follows: tube voltage of 40 kV, tube current of 40 mA, scanning angle range (2θ) of 20°~90°, scanning speed of 5°/min, and step size of 0.02°. A Quanta 250 cold-field emission scanning electron microscope (SEM) (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) was employed to observe the microscopic morphology of the alloys, and the microarea composition was determined using the energy-dispersive spectrometer (EDS) attached to the SEM.

2.4. Mechanical Property Testing

The inner hardness (to reflect the intrinsic property of the material) was measured using an HVS-50 Vickers hardness tester (YIMA, Shenzhen, China), with an applied load of 98 N and a dwell time of 20 s. To avoid the influence of possible surface carburization, all test points were strictly selected in the central region of the specimen (at least 1 mm away from the surface, far exceeding the potential carbon diffusion depth). Each specimen was measured five times at different central positions, and the average value was taken as the final inner hardness. A MTS810 universal testing machine (MTS Systems Corporation, Eden Prairie, MN, USA) was used to evaluate the room-temperature compressive properties. Compression specimens (size: 3 mm × 4.5 mm) were machined from the middle region of the sintered cylindrical samples (rather than the surface layer) to eliminate potential surface carburization effects. During machining, an additional ~0.5 mm of surface material was removed to ensure the specimens were composed of the inner matrix. The loading rate was set to 2 × 10−4 s−1. All compressive tests were performed under a unified protocol: specimens were continuously loaded until obvious fracture occurred or the deformation reached 50% (whichever came first). The H4 alloy exhibited excellent ductility and did not fracture even when the deformation reached 50%, so the test was stopped at this point to avoid excessive sample damage; the Ta-containing alloys with higher Laves phase content fractured before reaching 50% deformation, and the test was terminated upon fracture. For each alloy, four specimens were tested, and the average value was used as the index of compressive mechanical properties.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Relative Density

The test results of the relative density of CoCrFeNiTax bulk HEAs after vacuum hot-pressing sintering are shown in Table 1. As shown in Table 1, the relative densities of the CoCrFeNiTax HEAs all reach over 96%, with the Ta0.5 alloy exhibiting the highest relative density of up to 97.9%. This result fully confirms that the vacuum hot-pressing sintering process adopted in this study can effectively promote the densification of alloy powders, successfully fabricating bulk CoCrFeNiTax HEAs with high relative density. It provides a reliable structural foundation for subsequent mechanical property testing and practical applications. As the Ta content further increases to 2.0 atom, the alloy’s relative density slightly decreases, with the Ta2.0 alloy having a relative density of 97.3%. This variation in relative density is presumed to be related to the evolution of the alloy’s phase structure. After the addition of Ta, the CoCrFeNi alloy transforms from a single FCC phase to a dual-phase structure consisting of FCC phase and Laves phase (see Section 3.2). With the increase in Ta content, the volume fraction of the Laves phase gradually increases. However, the atomic packing modes of the Laves phase and FCC phase differ, which may lead to a slight reduction in atomic diffusion efficiency and densification rate during the sintering process.

Table 1.

Relative density of CoCrFeNiTax bulk HEAs after hot-pressing sintering.

In this study, the relative densities of the CoCrFeNiTax alloys after vacuum hot-pressing sintering were all ≥96%. This result is highly consistent with the advantages of powder metallurgy processes in the densification of HEAs. Sun et al. [28] also achieved a relative density of ≥96% when preparing CoCrFeNiTa0.5 and CoCrFeNiTa1.0 coatings via mechanical alloying combined with hot-pressing sintering. Their study pointed out that the “low-temperature sintering + pressure application” characteristic of powder metallurgy can reduce pores by promoting diffusion welding between particles, which aligns with the mechanism of uniform diffusion between Ta and matrix elements at the 950 °C sintering temperature in this study. Additionally, Niu et al. [19] found in their research on CoCrFeNiWx HEAs that the powder metallurgy process can effectively inhibit the segregation of high-melting-point elements (such as W and Ta), and the reduction in segregation further lowers the probability of “composition-segregation-induced pores” forming during sintering. In this study, no obvious compositional segregation regions were observed via SEM (Section 3.3), which indirectly confirms the positive effect of this mechanism on densification. By contrast, in traditional casting processes (e.g., Jiang et al. [23] observed large fluctuations in the relative density of CoCrFeNiTax alloys prepared by casting due to Ta segregation), the vacuum hot-pressing process used in this study demonstrates better stability in ensuring high densification, laying a structural foundation for subsequent mechanical property tests.

3.2. Phase Structure Analysis

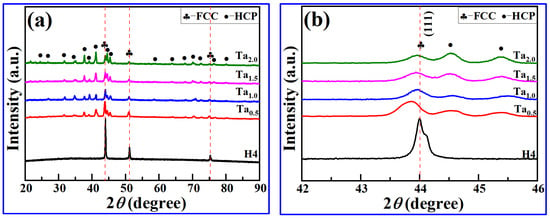

Figure 1 shows the XRD patterns of CoCrFeNiTax bulk HEAs. No characteristic peaks of carbides (e.g., Cr3C2, Fe3C) were detected in any XRD patterns, indicating that even if trace carbon diffused during sintering, it only existed in the solid solution in the surface layer and did not change the matrix phase composition. Combined with the CBN coating isolation and 50–100 μm surface removal, the phase composition characterized herein accurately reflects the intrinsic matrix structure of the alloys. As can be seen from Figure 1a, the Ta-free H4 alloy only exhibits characteristic diffraction peaks of the face-centered cubic (FCC) solid solution, indicating a single FCC phase structure, which is consistent with the report in Reference [7]. After adding the Ta element to the CoCrFeNi alloy, in addition to the diffraction peaks of the FCC phase, characteristic diffraction peaks of the Laves phase with a hexagonal close-packed (HCP) structure appear in the XRD patterns. With the increase in Ta content, the intensity of the Laves phase diffraction peaks gradually increases, while the intensity of the FCC phase diffraction peaks gradually decreases. This indicates that the addition of Ta element promotes the precipitation of the Laves phase, and the volume fraction of the Laves phase increases with the increase in Ta content.

Figure 1.

XRD patterns of CoCrFeNiTax bulk HEAs: (a) 20°–90°, (b) 42°–46°.

Two key phenomena can be further observed from the locally enlarged view in Figure 1b: First, the FCC phase of the H4 alloy shows an obvious (111) preferred orientation. With the increase in Ta content, the intensity of the (111) diffraction peak of the FCC phase decreases significantly, while the intensity of the Laves phase diffraction peak increases remarkably, which further confirms the regulatory effect of Ta content on phase composition and preferred orientation. Second, a secondary peak appears on the right side of the FCC diffraction peak near 2θ ≈ 44.2°. Combined with EDS composition analysis (see Section 3.3), this secondary peak corresponds to the Cr-rich FCC phase, indicating that the addition of Ta element may also lead to the local enrichment of Cr element in the FCC solid solution, forming an FCC phase with a slightly different composition.

To quantitatively analyze the effect of Ta content on the FCC phase structure, the lattice constant, crystal size, and relative volume fraction of the FCC phase were calculated using Equations (4)–(6) based on the XRD data, and the results are shown in Table 2.

where λ is the X-ray wavelength (1.54056 Å), θ is the diffraction angle, h, k, and l are the Miller indices, β and θ are the full width at half maximum (FWHM) of the measured spectrum and the diffraction angle corresponding to the peak position, respectively, K is set to 0.89, is the relative volume fraction (or relative content) of phase a in the bulk alloy, and Ii(FCC) and Ii(HCP) are the intensities of the i-th diffraction peaks of FCC phase and HCP phase in the XRD pattern, respectively.

Table 2.

Lattice constant, crystal size, and relative volume fraction of the FCC phase in CoCrFeNiTax bulk HEAs.

It can be seen from Table 2 that the H4 alloy has the smallest FCC phase lattice constant, approximately 0.2413 nm. After adding the Ta element, the lattice constant of the FCC phase increases significantly, and the lattice constants of the FCC phase in the four Ta-containing alloys range from 0.2480 nm to 0.2488 nm. This is because the atomic radius of Ta (1.46 Å) is much larger than that of Co (1.251 Å), Cr (1.249 Å), Fe (1.241 Å), and Ni (1.246 Å). When part of the Ta atoms are dissolved in the FCC lattice, lattice expansion and distortion are caused, thus increasing the lattice constant. It is worth noting that as the Ta content increases from 0.5 mol to 2.0 mol, the lattice constant of the FCC phase first decreases slightly and then increases slightly. This may be due to the fact that when the Ta content is relatively high, more Ta atoms precipitate from the FCC solid solution to form the Laves phase, which releases part of the lattice distortion energy, leading to a slight decrease in the lattice constant of the FCC phase. The slight increase in the lattice constant of the Ta2.0 alloy may be related to the enrichment of the Cr element in the FCC phase (the Cr-rich secondary peak in Figure 1b), and the difference in atomic radius between Cr atoms and matrix elements further affects the lattice size.

In terms of crystal size, the crystal size of the FCC phase in the H4 alloy is approximately 82.1 nm. After adding the Ta element, the crystal size of the FCC phase decreases significantly to 26.9–31.2 nm, and increases slightly with the increase in Ta content. The reason for this phenomenon is that the addition of the Ta element promotes the precipitation of the Laves phase, and the Laves phase particles can act as “barriers” for grain growth during the sintering process, inhibiting the excessive growth of FCC phase grains, thereby achieving grain refinement. With the increase in Ta content, the number of Laves phases increases, but the slight agglomeration of the Laves phase itself may weaken its inhibitory effect on the growth of FCC grains to a certain extent. Eventually, this manifests as a slight increase in the crystal size of the FCC phase, but the overall size remains at a fine-grain level of approximately 30 nm, which is conducive to improving the alloy strength through grain refinement strengthening.

In terms of relative phase volume fraction, the H4 alloy is 100% FCC phase. With the increase in Ta content, the relative volume fraction of the FCC phase decreases continuously from 79.4% (Ta0.5 alloy) to 11.6% (Ta2.0 alloy), and the relative volume fraction of the Laves phase increases from 20.6% to 88.4% accordingly. This fully confirms that Ta content is a key factor regulating the phase composition of CoCrFeNiTax alloys—the higher the Ta content, the more conducive to the formation and enrichment of the Laves phase, which is consistent with the Hume–Rothery rule: the atomic radius difference between Ta and elements such as Co and Ni is relatively large (>15%), and the mixing enthalpy between Ta and these elements is negative (making it easier to form intermetallic compounds), resulting in the limited solubility of Ta in the FCC solid solution. Excess Ta atoms will combine with matrix elements to form a stable Laves phase.

3.3. Microstructure

3.3.1. Evolution of SEM Micromorphology

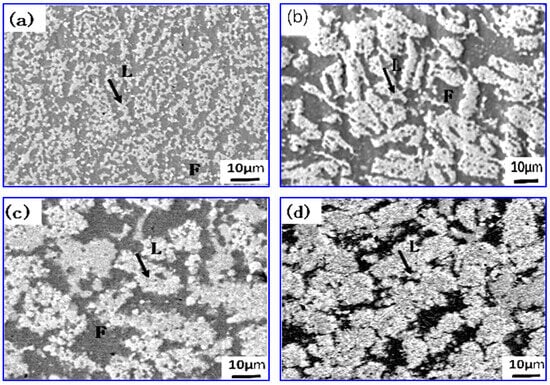

Figure 2 shows the secondary electron images of CoCrFeNiTax bulk HEAs. As can be seen from the figure, all Ta-containing alloys exhibit dual-phase microstructure characteristics, namely gray-black matrix regions (denoted as Region F) and light-white dispersed regions (denoted as Region L), and the Ta content exerts a significant regulatory effect on the morphology and volume fraction of the two phases: When x = 0.5, Region L is dispersedly distributed in the continuous Region F matrix in dot-like and short strip-like forms, with a relatively low volume fraction; when x = 1.0, the morphology of Region L transforms into a long, strip-like shape, grows along a specific direction, and penetrates part of Region F; Region F still maintains the characteristic of a continuous matrix, but its volume fraction is significantly lower than that of the Ta0.5 alloy; when x ≥ 1.5, Region L further transforms into a lamellar shape, and its volume fraction increases significantly, forming a microstructure morphology of “interwoven lamellar Region L + interspersed isolated Region F”; among them, Region L in the Ta2.0 alloy has become the dominant phase in the microstructure, while Region F only exhibits an isolated island-like distribution.

Figure 2.

SEM images of CoCrFeNiTax bulk HEAs: (a) Ta0.5, (b) Ta1.0, (c) Ta1.5, (d) Ta2.0.

In summary, with the increase in Ta content, the morphology of Region L (light-white) gradually evolves from “dot-like/short strip-like → long strip-like → lamellar”, and its volume fraction continues to increase; while Region F (gray-black phase) gradually shrinks from “continuous matrix → semi-continuous matrix → isolated island-like”. The morphology and distribution characteristics of the two phases directly reflect the driving effect of Ta content on the evolution of the alloy microstructure.

3.3.2. EDS and Mapping Composition Characterization

To clarify the chemical composition of Region F and Region L, SEM-EDS point scan analysis was conducted on each alloy, and the results are presented in Table 3. It can be seen from the data in the table that the main elements of Region F are Co, Cr, Fe, and Ni, with their atomic fractions close to the equiatomic ratio of the original CoCrFeNi alloy (each element accounts for approximately 22–27 at.%), and the Ta content is extremely low (only 1.51–2.48 at.%). This indicates that Region F is a CoCrFeNi-based solid-solution phase with a small amount of Ta dissolved in it. The core elements of Region L are Co and Ta, where the atomic fraction of Ta is significantly higher than that in Region F (25.52–31.63 at.%) and shows an increasing trend with the increase in total Ta content. In the L region of the Ta2.0 alloy, the total atomic fraction of Co, Cr, Fe, and Ni is 68.37%, and the atomic fraction of Ta is 31.63%. The atomic ratio of total transition metals to Ta is approximately 2.1:1, which is highly consistent with the ideal ratio (2:1) of the AB2-type topological structure of Laves phases. This result verifies the rationality of multicomponent substitution—mutual substitution of Co, Ni, Cr, and Fe (with atomic radii of 1.24–1.25 Å) at the B-sites does not change the core topological structure of the Laves phase. Instead, it only adapts to the “cocktail effect” of high-entropy alloys through compositional flexibility, which is consistent with the typical formation law of Laves phases in high-entropy alloys [18,28].

Table 3.

Results of SEM-EDS point scan analysis for CoCrFeNiTax bulk HEAs (at.%).

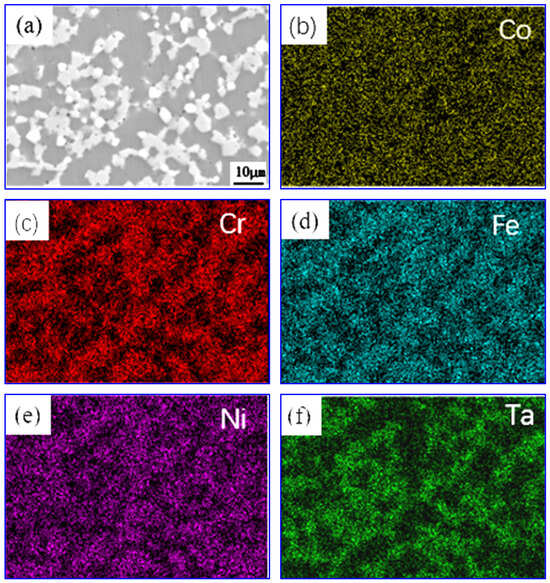

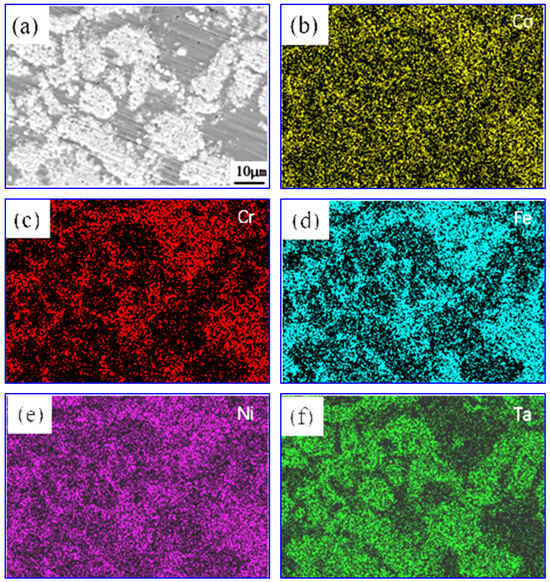

To further verify the uniformity of composition distribution and the correlation between phases, EDS mapping analysis was performed on Ta0.5 and Ta1.5 alloys (Figure 3 and Figure 4). The results show that Cr, Fe, and Ni exhibit a consistent distribution pattern: they are all highly enriched in the gray-black Region F and only present in trace amounts in Region L. Co is relatively uniformly distributed throughout the alloy and exists in both Region F and Region L, which is consistent with the characteristic that Co is a common element in both phases observed in the EDS point scan. Ta shows a strong regional selectivity, only enriched in the light-white Region L; as the total Ta content increases, the area of Ta enrichment regions (Region L) expands significantly, which is completely consistent with the evolution law of SEM morphology.

Figure 3.

EDS mapping results of CoCrFeNiTa0.5 bulk HEA: (a) SEM image, (b) Co, (c) Cr, (d) Fe, (e) Ni, (f) Ta.

Figure 4.

EDS mapping results of CoCrFeNiTa1.5 bulk HEA: (a) SEM image, (b) Co, (c) Cr, (d) Fe, (e) Ni, (f) Ta.

Based on the combination of XRD, EDS, and thermodynamic analyses, it can be clearly confirmed that Region F is an FCC solid-solution phase (CoCrFeNi-based, with a small amount of dissolved Ta), and Region L is a multicomponent solid-solution-type Laves phase with a hexagonal close-packed (HCP) structure. Compared with traditional binary Laves phases, this multicomponent solid-solution Laves phase takes Ta (with a large atomic radius) as the A-site component, and Co, Ni, Cr, Fe (with similar atomic radii) as B-site components (which form mixed B-sites through mutual solid-solution substitution). It follows the general AB2-type topological structure of Laves phases overall, rather than being strictly limited to binary stoichiometry. Moreover, the volume fraction of the Laves phase increases continuously with the increase in Ta content, and this phenomenon can be explained by the Hume–Rothery rule and the mixing enthalpy theory. First, the atomic radius of Ta is 1.46 Å, which is much larger than that of Co (1.251 Å), Cr (1.249 Å), Fe (1.241 Å), and Ni (1.246 Å) (the difference is >15%). According to the Hume–Rothery rule, when the atomic radius difference between the solute and the solvent exceeds 15%, the solubility of the solute in the solvent is extremely low. Therefore, the solubility of Ta in the CoCrFeNi-based FCC solid solution is limited, and the excess Ta atoms must precipitate in the form of a second phase. Second, the mixing enthalpy of Ta with Co and Ni is negative (ΔHmix (Ta-Co) = −10 kJ/mol, ΔHmix (Ta-Ni)= −20 kJ/mol) [29]. A negative mixing enthalpy indicates that there is a strong interatomic interaction between Ta and Co/Ni, making it easier to form stable intermetallic compounds. When the Ta content increases, the number of undissolved Ta atoms increases, and the driving force for combining with Co and Ni to form multicomponent solid-solution-type Laves phases is enhanced. This ultimately leads to a significant increase in the volume fraction of the Laves phase, forming a microstructural evolution law where “the FCC phase decreases gradually and the Laves phase becomes dominant gradually”.

3.3.3. Phase Composition and Evolution Mechanism

The compositional flexibility of the Laves phase in this study is not an isolated case but a common feature of high-entropy alloy systems. The Laves phase reported by Huo et al. [18] in CoCrFeNiTax high-entropy alloys has an atomic ratio of Co + Fe to Ta of 1.8:1, which deviates from the 2:1 ratio of binary Co2Ta, yet it was confirmed to be an MgZn2-type Laves phase through the combination of XRD and EDS. Similarly, the (Co, Ni, Cr)2Ta-type Laves phase discovered by Xu et al. [30] in CoCrNiTax medium-entropy alloys exhibits an atomic ratio of transition metals to Ta of 1.9:1, also showing a deviation from binary stoichiometry, but it was proven to possess a typical Laves phase strengthening effect. These studies are highly consistent with the compositional characteristics and characterization logic of this work, fully corroborating the reliability of identifying the multicomponent solid-solution-type Laves phase.

3.4. Mechanical Properties

3.4.1. Microhardness Analysis

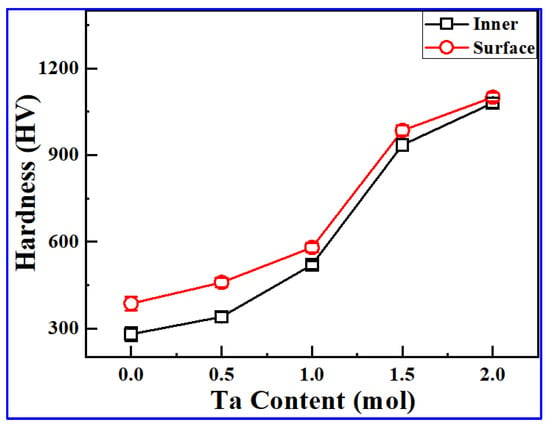

Figure 5 presents the test results of inner and surface microhardness of CoCrFeNiTax bulk HEAs. As shown in the figure, with the increase in Ta content, both the inner and surface hardness of the alloys show a significant increasing trend. In this study, the core conclusions of the alloy’s mechanical properties are all derived based on inner hardness data. The surface hardness is the apparent hardness affected by the carburized layer formed by carbon diffusion from the graphite mold during sintering, and is only used as an auxiliary characterization result. When the Ta content is 0.5 mol, the inner hardness reaches 340 HV and the surface hardness reaches 459 HV. When the Ta content increases to 1.0 mol, the inner and surface hardness rapidly increase to 520 HV and 580 HV, respectively. As the Ta content further increases to 1.5 mol, both hardness values jump to 985 HV and 935 HV. When the Ta content reaches 2.0 mol, the inner hardness (core performance index) reaches 1080 HV and the surface hardness is 1100 HV (affected by the carburized layer) which is about 3.9 times higher than that of the Ta-free H4 alloy (with a hardness of 280 HV).

Figure 5.

Surface and inner hardness of CoCrFeNiTax bulk HEAs.

It is worth noting that the surface hardness of all Ta-containing alloys is higher than the inner hardness. This phenomenon is closely related to the solid-solution strengthening effect of the carburized surface layer: during the sintering process, trace carbon elements from the graphite mold diffuse to the alloy surface and form a solid solution, resulting in a carbon-rich reinforced layer, thereby increasing the surface hardness. The continuous increase in the inner hardness of the alloy (which better reflects the intrinsic hardness of the material) is directly related to the evolution of the phase structure: with the increase in Ta content, the volume fraction of the hard Laves phase (with a hardness significantly higher than that of the FCC solid solution) increases from 20.6% to 88.4%, and its contribution to hardness gradually becomes dominant, ultimately promoting the continuous rise in inner hardness.

3.4.2. Room-Temperature Compressive Property Analysis

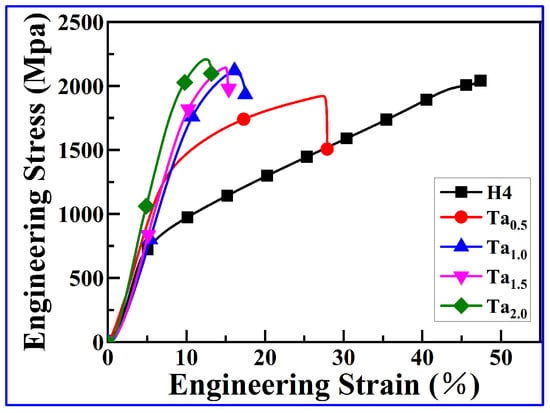

Figure 6 shows the room-temperature engineering stress–strain curves of CoCrFeNiTax bulk HEAs, and Table 4 lists the corresponding compressive mechanical property indices (σ0.2: 0.2% yield strength, σb: fracture strength, εf: fracture strain). As can be seen from Figure 6 and Table 4, Ta content has an extremely significant regulatory effect on the compressive properties of the alloys, generally showing a trend of “increasing strength and decreasing plasticity”, with specific performances as follows: The Ta-free H4 alloy (single FCC phase) exhibits typical plastic deformation characteristics, with a σ0.2 of approximately 760 MPa. It does not fracture even when compressed to 50% deformation, showing excellent plasticity but low strength, which is consistent with the characteristic of easy dislocation slip in the FCC phase. After adding the Ta element, the alloy strength increases rapidly while the plasticity decreases synchronously. The σ0.2 of the Ta0.5 alloy increases to 1350 MPa, the σb reaches 1870 MPa, and the εf is 28%, realizing the initial balance between strength and plasticity. With the continuous increase in Ta content, the strength keeps rising and the plasticity further decreases. The σ0.2 values of the Ta1.0 and Ta1.5 alloys increase to 1520 MPa and 1640 MPa, and the σb increase to 2080 MPa and 2160 MPa, respectively, while the εf decreases to 16% and 14%, respectively. When the Ta content reaches 2.0 mol, the alloy still maintains a relatively good strength–plasticity matching: the σ0.2 reaches 1750 MPa, the σb reaches 2280 MPa, and although the εf decreases to 12%, it still has a certain degree of plasticity compared with similar alloys with high Laves phase content, which can meet the application requirements of scenarios demanding high strength.

Figure 6.

Stress–strain curves of CoCrFeNiTax bulk HEAs.

Table 4.

Room-temperature mechanical properties of CoCrFeNiTax bulk HEAs.

3.4.3. Mechanical Property Strengthening Mechanism

The strength improvement of CoCrFeNiTax alloys mainly originates from the combined action of solid-solution strengthening and second-phase strengthening. Zhang et al. [31] prepared NiTiCrNbTax coatings by laser cladding and found that the increase in Ta content could promote the formation of BCC phase and the precipitation of Laves phase (Cr2Nb type). However, due to the excessively high proportion of BCC phase, the coating hardness decreased slightly (from 923 HV to 825 HV), indicating that the proportion of phase composition plays a key role in the strengthening effect. Tang et al. [27] prepared CoCrFeNiTa HEA (single Ta content) via mechanical alloying and spark plasma sintering (SPS), and obtained a dual-phase structure of FCC + Laves phase with a microhardness of ~1138 HV. Their study confirmed the high strengthening potential of Laves phase, but lacked a systematic investigation on the effect of Ta content variation, making it difficult to establish the quantitative relationship between composition and properties. Sun et al. [28] fabricated CoCrFeNiTax (x = 0.5, 1.0) HEA coatings on Q235 substrates by mechanical alloying and hot-pressing sintering, with a microhardness of 500–600 HV. Their work focused on the wear resistance of coatings, while the mechanical properties of bulk alloys (e.g., compressive strength and plasticity) were not characterized, limiting the understanding of bulk material application potential. Jiang et al. [23] prepared CoCrFeNiTax (x = 0–0.75) alloys using the casting method and observed that with the increase in Ta content, the alloy gradually transitioned from a single FCC phase to hypoeutectic, eutectic (FCC + Co2Ta-type Laves phase), and hypereutectic structures. Among them, the eutectic alloy (x = 0.4) exhibited a fracture strength of 2293 MPa and a plasticity of 22.6% due to its ultrafine lamellar structure, which further verified the contribution of Laves phase to strength. However, severe Ta segregation occurred in the cast alloys, resulting in uneven microstructure and large performance fluctuation.

In contrast, this study adopts vacuum hot-pressing sintering (a lower sintering temperature of 950 °C compared to SPS) and systematically adjusts Ta content (x = 0, 0.5, 1.0, 1.5, 2.0 mol). On one hand, the process inhibits Ta segregation and achieves a relative density of ≥96% (Table 1), ensuring uniform microstructure; on the other hand, it quantitatively reveals the evolution law of phase composition (FCC phase volume fraction from 100% to 11.6%, Laves phase from 0 to 88.4%; Table 2) and mechanical properties (inner hardness from 280 HV to 1080 HV, yield strength from 760 MPa to 1750 MPa; Table 4) with Ta content. The core finding that “solid solution strengthening (by Ta-induced lattice distortion) + second-phase strengthening (by Laves phase hindering dislocation motion)” synergistically improves strength not only supplements the phase evolution mechanism of Ta-containing HEAs, but also provides experimental basis for the preparation of bulk HEAs with balanced strength and plasticity.

In terms of solid-solution strengthening, the strengthening of CoCrFeNiTax alloys comes from the combined action of solid-solution strengthening and second-phase strengthening: the atomic radius of Ta (1.46 Å) is much larger than that of Co, Cr, Fe, and Ni (with an atomic radius difference > 15%). A small amount of Ta dissolved in the FCC phase increases the lattice constant of the FCC phase from 0.2413 nm to 0.2488 nm, forming a lattice distortion field that hinders the initiation and slip of dislocations, which is the basis for Ta-containing alloys to be stronger than the H4 alloy.

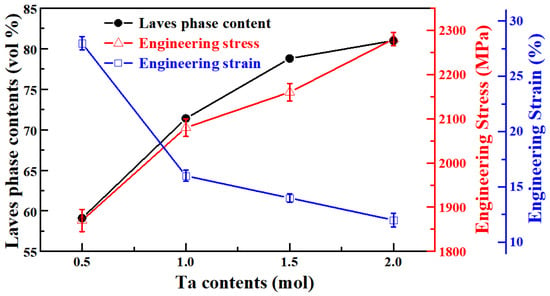

With the increase in Ta content, the undissolved Ta combines with Co and Ni to form an HCP-structured Laves phase dominated by Co-Ta. Its volume fraction increases from 20.6% to 88.4%, and its morphology evolves from dot-like/short strip-like to long strip-like and lamellar. It hinders the movement of dislocations through dislocation bypassing (consuming additional energy) and dislocation cutting (needing to cross the phase interface). Figure 7 further confirms the correlation between Laves phase content and mechanical properties: with the increase in Laves phase content, the engineering stress of the alloy increases linearly, while the engineering strain decreases significantly, which directly indicates that the second-phase strengthening effect of Laves phase is the core driving force for the improvement of strength.

Figure 7.

Relationship between engineering stress, strain, and Laves phase content of CoCrFeNiTax bulk HEAs.

Combined with the mechanical characteristics of the Ta2.0 alloy (fracture strength of 2280 MPa, plasticity of 12%) and its high compactness (relative density of 97.3%), it exhibits potential application value in room-temperature scenarios that require high load-bearing capacity while allowing for moderate plastic deformation. For instance, it can be used as room-temperature load-bearing structural components for spacecraft (e.g., satellite platform connectors), relying on its load-bearing capacity far exceeding that of traditional titanium alloys (room-temperature strength ≤ 1200 MPa) to resist launch impacts. It can also be applied as supporting components for room-temperature high-pressure hydrogen storage cylinders, where its high yield strength of 1750 MPa is suitable for adapting to the 35 MPa-grade working pressure; meanwhile, the basic corrosion resistance endowed by the Cr element in the alloy (22–27 at.% in the FCC phase, Table 3) can mitigate corrosion risks in hydrogen environments. In addition, its high-strength characteristic can also support lightweight protection designs (e.g., industrial impact-resistant guards), ensuring impact resistance while reducing the structural weight.

4. Conclusions

In this study, CoCrFeNiTax HEAs were successfully fabricated via vacuum hot-pressing sintering, with all alloys achieving a relative density ≥ 96%, effectively inhibiting Ta segregation. The Ta-free H4 alloy exhibited a single FCC phase. With increasing Ta content, the alloy transformed into an “FCC + hexagonal close-packed (HCP) Laves phase” dual-phase system. The volume fraction of the Laves phase increased from 20.6% (Ta0.5) to 88.4% (Ta2.0) (morphology evolving from dot-like/short strip-like to lamellar), while the FCC phase decreased from 79.4% (Ta0.5) to 11.6% (Ta2.0) (shrinking from a continuous matrix to isolated islands). Ta dissolution increased the FCC lattice constant from 0.2413 nm (H4) to 0.2488 nm (Ta2.0) and refined the FCC crystal size from 82.1 nm (H4) to ~30 nm (Ta-containing alloys). Ta content significantly regulated the alloy’s mechanical performance with a “strength/hardness increase, plasticity decrease” trend: inner hardness increased from 280 HV (H4) to 1080 HV (Ta2.0), yield strength from 760 MPa (H4) to 1750 MPa (Ta2.0), and maximum fracture strength reached 2280 MPa (Ta2.0); fracture strain decreased from >50% (H4, no fracture) to 12% (Ta2.0), maintaining a balanced strength–plasticity match. The strength improvement originated from the combined action of Ta-induced solid-solution strengthening and Laves phase second-phase strengthening.

Author Contributions

Methodology, B.R. and Y.Z.; Investigation, A.J., C.L., and J.Q.; Resources, J.L. and B.R.; Data curation, Y.Z., and J.L.; Writing—original draft preparation, B.R. and A.J.; Writing—review and editing, C.L. and J.Q.; Project administration, J.L. and Y.Z.; Funding acquisition, A.J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Postgraduate Education Reform and Quality Improvement Project of Henan Province, Grant No. YJS2025GZZ63.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in this article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Yeh, J.W.; Chen, S.K.; Lin, S.J.; Gan, J.Y.; Chin, T.S.; Shun, T.T.; Tsau, C.H.; Chang, S.Y. Nanostructured high entropy alloys with multiple principal elements: Novel alloy design concepts and outcomes. Adv. Eng. Mater. 2004, 6, 299–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantor, B.; Chang, I.T.H.; Knight, P. Microstructural development in equiatomic multicomponent alloys. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2004, 375–377, 213–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miracle, D.B.; Senkov, O.N. A critical review of high entropy alloys and related concepts. Acta Mater. 2017, 122, 448–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.F.; Xu, X.; Körmann, F.; Yin, W.; Zhang, X.; Gadelmeier, C.; Glatzel, U.; Grabowski, B.; Li, R.X.; Liu, G.; et al. Lattice distortions and non-sluggish diffusion in BCC refractory high entropy alloys. Acta Mater. 2025, 297, 121283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odabas, O.; Karaoglanli, A.C.; Ozgurluk, Y.; Binal, G. Evaluation of high-temperature oxidation resistance of AlCoCrFeNiZr high-entropy alloy (HEA) coating system at 1000 °C and 1100 °C. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2025, 512, 132439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otto, F.; Dlouhý, A.; Somsen, C.; Bei, H.; Eggeler, G.; George, E.P. The influences of temperature and microstructure on the tensile properties of a CoCrFeMnNi high-entropy alloy. Acta Mater. 2013, 61, 5743–5755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantor, B. Multicomponent high-entropy cantor alloys. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2021, 120, 100754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.X.; Li, H.; Xu, X.L. Formation of dual-phase structure and property enhancement mechanism in deep undercooling solidification of CoCrFeNi high-entropy alloy. J. Alloys Compd. 2025, 1040, 183659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.D.; Xie, D.; Li, D.Y.; Zhang, Y.; Gao, Y.F.; Liaw, P.K. Mechanical behavior of high-entropy alloys. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2021, 118, 100777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, R.B.; Arora, H.S.; Mukherjee, S.; Singh, S.; Singh, H.; Grewal, H.S. Exceptionally high cavitation erosion and corrosion resistance of a high entropy alloy. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2018, 41, 252–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, P.; Zhang, T.W.; Zhao, D.; Ma, S.G.; Li, Q.; Wang, T.; Wang, Z.H. Effects of stress states and strain rates on mechanical behavior and texture evolution of the CoCrFeNi high-entropy alloy: Experiment and simulation. J. Alloys Compd. 2021, 851, 156779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, Y.S.; Chen, J.; Tan, H.; Cheng, J.; Yang, J.; Liu, W.M. Vacuum tribological behaviors of CoCrFeNi high-entropy alloy at elevated temperatures. Wear 2020, 456–457, 203368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.X.; Taylor, M.A.; Perepezko, J.H.; Marks, L.D. Competition between thermodynamics, kinetics and growth mode in the early-stage oxidation of an equimolar CoCrFeNi alloy. Acta Mater. 2020, 196, 651–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.Q.; Li, D.Y. Dynamic response of high-entropy alloys to ballistic impact. Sci. Adv. 2022, 8, eabp9096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, L.; Wang, X.J.; Jia, F.C.; Zhao, X.C.; Huang, B.X.; Ma, J.; Wang, C.Z. Effect of Si element on phase transformation and mechanical properties for FeCoCrNiSix high-entropy alloys. Mater. Lett. 2021, 282, 128809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Wang, L.; Tang, Y.C.; Luo, L.; Luo, L.S.; Su, Y.Q.; Guo, J.J.; Fu, H.Z. Microstructure and mechanical properties of CoCrFeNiWx high-entropy alloys reinforced by μ phase particles. J. Alloys Compd. 2020, 843, 155997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Wang, S.; Jia, Y.; Zhang, W.; Chen, R.; Cao, B.; Yu, S.; Wei, J. Review on the tensile properties and strengthening mechanisms of additive manufactured CoCrFeNi-based high-entropy alloys. Metals 2024, 14, 437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, W.Y.; Zhou, H.; Fang, F.; Zhou, X.F.; Xie, Z.H.; Jiang, J.Q. Microstructure and properties of novel CoCrFeNiTax eutectic high-entropy alloys. J. Alloys Compd. 2018, 735, 897–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, Z.Z.; Xu, J.; Wang, T.; Wang, N.R.; Han, Z.H.; Wang, Y. Microstructure, mechanical properties and corrosion resistance of CoCrFeNiWx (x = 0, 0.2, 0.5) high-entropy alloys. Intermetallics 2019, 112, 106550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, F.; Wang, Z.J.; Cheng, P.; Wang, Q.; Li, J.J.; Dang, Y.Y.; Wang, J.C.; Liu, C.T. Designing eutectic high-entropy alloys of CoCrFeNiNbx. J. Alloys Compd. 2016, 656, 284–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, Z.Z.; Wang, Y.Z.; Geng, C.; Xu, J.; Wang, Y. Microstructural evolution, mechanical and corrosion behaviors of as-annealed CoCrFeNiMox (x = 0, 0.2, 0.5, 0.8, 1) high-entropy alloys. J. Alloys Compd. 2020, 820, 153273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, M.J.; Jiang, X.J.; Dong, M.Y.; Hu, M.L.; Yang, Y. Preparation and effect of vanadium addition on the mechanical properties of CoCrFeNiVx high-entropy alloy. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2023, 27, 7705–7712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Han, K.M.; Qiao, D.X.; Lu, Y.P.; Cao, Z.Q.; Li, T.J. Effects of Ta addition on the microstructures and mechanical properties of CoCrFeNi high-entropy alloy. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2018, 210, 43–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, X.; Ma, L.Y.; Li, T.; Song, J.J.; Du, Y.; Lin, P.Y.; Su, Y.F.; Zhang, Y.S.; Hu, L.T. Ta-alloying for the construction of fully eutectic structure to enhance the broad-temperature tribological performance of CoCrFeNi high-entropy alloy: A systematic study on compositional and structural evolutions. J. Alloys Compd. 2025, 1036, 181581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.L.; Shangguan, Z.X.; Ma, S.; Wang, Z.M. Effects of the Ta content on the microstructure and oxidation behavior of TiCrNbTax (x = 0, 0.5, 1.0) medium-entropy alloys. Mater. Lett. 2025, 400, 139174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ai, C.; Wang, G.X.; Liu, L.; Guo, M.; He, F.; Zhou, J.; Chen, Y.N.; Wang, Z.J.; Gan, B. Effect of Ta addition on solidification characteristics of CoCrFeNiTax eutectic high-entropy alloys. Intermetallics 2020, 120, 106769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, X.C.; Hou, Y.Y.; Wang, C.L.; Liu, Y.W.; Meng, Z.C.; Wang, Y.L.; Cheng, G.H.; Zhou, W.L.; La, P.Q. Microstructure and mechanical properties of CoCrFeNiTa high-entropy alloy prepared by mechanical alloying and spark plasma sintering. Mater. Charact. 2024, 210, 113826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q.T.; Han, Z.H.; Wan, D.; Zhou, X.Y.; Ma, W.S.; Wang, Y. Heterostructure-reinforced CoCrFeNiTax (x = 0.5 and 1) high-entropy alloy coatings fabricated by combining mechanical alloying and hot-pressing sintering. Adv. Powder Technol. 2025, 36, 104891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeuchi, A.; Inoue, A. Classification of bulk metallic glasses by atomic size difference, heat of mixing and period of constituent elements and its application to characterization of the main alloying element. Mater. Trans. 2005, 46, 2817–2829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Qu, S.Q.; Xu, X.J.; Zhao, C.L.; Ai, C.; Ru, Y.; Zhang, H.; Li, S.S.; Gong, S.K.; Guo, M.; et al. Effects of Ta addition on microstructure, compression and wear properties of CoCrNiTax medium-entropy alloys. Intermetallics 2025, 187, 109011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.R.; Cui, X.F.; Jin, G.; Ding, Q.L.; Zhang, D.; Wen, X.; Jiang, L.P.; Wan, S.M.; Tian, H.L. Microstructure evolution and properties of NiTiCrNbTax refractory high-entropy alloy coatings with variable Ta content. J. Alloys Compd. 2022, 891, 161756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).