Abstract

This article synthesizes the impact of parental financial socialization on an individual’s financial behavior. To better understand the role of parental financial socialization, 219 peer-reviewed articles from the Scopus database were analysed. A combination of bibliometric and thematic analysis was used, resulting in four major themes: (1) Mechanisms of parental and family financial socialization, (2) Financial outcomes from family financial socialization, (3) Psychological Mediators of Socialization Effects, and (4) Socio-Cultural and Institutional Contexts as Moderators. Findings of this study reveal that parental modeling, communication, psychology, socio-cultural, and institutional context are key mechanisms in the development of financial norms and competencies. The study also confirms the relevance of the Social Learning Theory, Family Systems Theory, Theory of Planned Behavior, Financial Capability Theory, and Life Course Perspective Theory. The contributions of this study include the development of a multi-level model that identifies family, psychological, and institutional determinants of financial behavior and proposes areas for future research in different cross-cultural contexts. From a practical perspective, this study highlights the importance of integrating the factors mentioned above into policy interventions by regulators and all stakeholders.

1. Introduction

Financial behavior has become an increasingly important domain of research as societies face rising levels of personal debt [1,2,3] and growing financial complexity [4,5], widening inequality [6], and the rapid digitalization of financial services [7]. Globally, young individuals have to make difficult financial decisions on matters related to borrowing, financing of student loans, management of credit cards, buy now pay later (BNPL) schemes, parents’ medical expenses, purchase of assets, investments, financial freedom, and retirement. However, studies show that most individuals have limited knowledge on the fundamentals of finances [8,9], do not make wise financial choices [10,11,12], and take loans and expose themselves to long-term debt that could potentially harm them financially [2], consequently contributing towards persistent financial strain and/or insecurity [13]. These encounters tend to be much more prevalent in the emerging adult stage of life as the individual goes through the transition of moving away from their parents’ financial guidance and support to managing their own finances and trying to achieve financial independence.

In recent years, researchers have begun to investigate financial socialization—the path through which individuals acquire financial knowledge and how the socialization process molds one’s attitude towards financial behavior and money management. Parental involvement in this financial socialization process is the most significant factor influencing one’s financial perspectives, attitudes, and behaviors [14,15,16]. This includes modeling, instructing, setting standards/rules, and communicating with their children about finances. By doing these things, parents teach their children at a very young age how to manage their finances, understand the importance of perpetual and diversified investments for long-term financial sustainability, basic knowledge about interest rates and compounding effects, the danger of scams and get-rich-quick (ponzi) schemes, and planning for major expenses such as purchase of assets and children’s education and finally retirement planning. These practices and knowledge will ultimately ensure that these adults take informed decisions at every stage of life, eventually contributing towards financial freedom and well-being as an adult. Research shows how parental behavior influences a child’s financial literacy, saving, spending, taking risks, using credit cards, and the overall ability to achieve long-term financial successfully [17,18,19,20]. While this body of research has reached consensus regarding the influence of parental modelling and teaching on financial literacy, there are also many variables (socioeconomic status, family structure, cultural beliefs, parenting style, and psychological characteristics) that impact the financial trajectory of a person or family unit.

In reality, there remains a widespread phenomenon of inadequate financial literacy, poor financial planning, management, and decision-making, which contributes to increased personal debt, and mental stress. The extant literature documents that one of the most important factors affecting financial behaviors is the way children learn about money before attending formal schooling, i.e., the family environment. While there is extensive literature acknowledging the significant role that parents play in socializing their children in financial matters, the mechanisms by which this parental influence can lead to the development of an individual’s financial capability and behavior have not been well developed theoretically or practically. This consequently leaves a major gap between theory and practice. Therefore, additional research is needed to understand the mechanics of how parents’ financial socialization interacts with structural context (i.e., institutional financial education programs, policies and socio-economic factors) and affects the development of individual financial capability and financial behaviors across the life span. Presently, the financial behavior frameworks are not comprehensive in nature, often based solely on one theoretical framework (for example, Social Learning Theory, or Theory of Reasoned Action and Planned Behavior), and do not take into consideration the multiple levels of interaction between family systems, psychological processes, behavioral mechanisms, and institutional environments. As a result of this lack of a comprehensive explanatory model, policymakers, educators and financial institutions are unable to develop effective intervention programs to change the underlying causes of poor financial behavior. More importantly, it limits researchers’ ability to understand the dynamic, intergenerational, and socio-cultural aspects of the development of financial behavior. Thus, there is a clear need for the development of a financial behavior model that includes psychological mediators, behavioral mechanisms, and institutional moderators and is supported by a systematic and critical synthesis of the extensive body of research evidence.

To close these gaps, this research takes a methodical, bibliometric and content analytic approach to scientifically compile the existing research on parental socialization and financial behavior into a single consolidated and coherent structure, providing a visual representation of the intellectual framework, identifying the major themes represented within the literature, and creating a unified theory-guided framework of empirical findings. The findings of the current research will provide multiple significant contributions. First, through this synthesis of large and diverse collection of literature (n = 219 studies), this study provides a more systematic and comprehensive form of theoretical justification compared to traditional literature review. Second, the proposed model is based on multiple levels of analysis that are grounded in five existing theories: Social Learning Theory; Family Systems Theory; the Capability Approach; the Theory of Planned Behavior; and Behavioral Economics. The combined use of these theoretical perspectives allows for an expanded view of financial behavior compared to narrow cognitive and behavioral explanations of individual finance behavior. Third, the results of this research can support policy-makers, educators and financial services providers in developing effective strategies to support the financial well-being of individuals and families. The results highlight how parents continue to influence the financial socialization of their children; therefore, focus should be placed on developing family-based financial education programs that can support and improve the financial well-being of families rather than focusing solely on improving the financial well-being of individual family members. Finally, by identifying the limitations of Western-centric research and calling for culturally grounded models, the study opens the door for future investigations that better reflect the diversity of financial norms and socialization practices worldwide. The call for culturally relevant financial behavior models will allow future studies to explore how different cultures develop and encourage their financial norms, thus providing researchers with a starting point for developing culturally specific financial behaviors.

Overall, this study establishes that parental influence on a child’s financial behavior and capability is central, but is currently underdeveloped, and identifies the gaps within current theories, methods, and contexts for exploring parental influence on a child’s financial capabilities. It provides a basis for researchers to develop a comprehensive, multidisciplinary framework to connect parental influence on financial capability with behavioral mechanisms and long-term financial well-being. This approach provides a more comprehensive and culturally relevant means to understand and improve financial behavior outcomes throughout one’s lifetime. The study is organized as follows. Section 2 outlines the methodology used in the study, while Section 3 presents a descriptive analysis, a bibliometric assessment, a content evaluation, and suggestions for future research. Section 4 presents the conclusion.

2. Materials and Methods

The study employs an integrated methodological approach combining bibliometrics and thematic content analysis to systematically synthesize literature concerning the relationship between parental socialization and financial behaviors. The bibliometric method provides quantitative measures of publication structures (e.g., trends, key contributors, leading journals and countries) while thematic content analysis provides a qualitative basis for identifying conceptual patterns within the research literature. These methods, taken together, will ultimately provide complete coverage of both breadth and depth in the development of knowledge relating to parental financial socialization and its relationship to financial behavior, financial capability and the development of research across the disciplines over time.

For the purposes of this study, the research workflow is based on an organized process; within the Scopus database, the literature related to parental financial socialization, financial behavior of parents and the financial behavior of their children is analyzed. The Scopus database is considered appropriate for this type of bibliometric analysis because it offers access to numerous academic journals across multiple disciplines, rigorous standards of journal curation, uniform peer review, and stable citation indexing, all of which contribute to the reliability and comparability of bibliometric datasets [21,22,23]. The methodology for this search includes the use of a structured Boolean search with filters by subject area to ensure that the retrieved records are conceptually accurate and related to their relevant disciplines, and that the format of the records allows for easy replication of the searches by future researchers. The methodology also includes the use of Scopus’ advanced search capabilities for accurately retrieving and replicating records related to parental socialization and family socialization of children around money-related matters. The structured Boolean search strategy to identify the relevant publication records consisted of a search query consisting of the following: TITLE-ABS-KEY (“parental” OR “parents” OR “parental socialization” or “family socialization” AND “financial behavior” OR “financial efficacy” OR “financial knowledge” OR “financial well-being”) AND (LIMIT-TO (SUBJAREA, “ECON”) OR LIMIT-TO (SUBJAREA, “SOCI”) OR LIMIT-TO (SUBJAREA, “PSYC”) OR LIMIT-TO (SUBJAREA, “BUSI”) OR LIMIT-TO (SUBJAREA, “ARTS”)).

Research to develop the systematic review was conducted according to the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses) framework. All records that were retrieved were exported into Microsoft Excel, and duplicate records were removed. The titles and abstracts of the remaining records were screened against the pre-established criteria for inclusion and exclusion. Inclusion criteria were studies published in peer-reviewed journals, written in English, and investigate parental/family influences on financial behaviors, financial literacy, financial capability, and related psychological constructs. Studies that focused on macro-financial issues only, such as corporate finance, health, education (non-financial), and child development unrelated to financial outcomes, were excluded from eligibility. Following this initial screening process, a total of 219 studies remained eligible to be analyzed in depth, as they satisfied both the conceptual and methodological criteria of the review. The final dataset contained a complete bibliographic record for each article, including the title, abstract, keywords, author(s), institutional affiliations, country, and citation counts.

Subsequently, the dataset will be used for both performance and scientific analysis. The bibliometric analysis uses the Biblioshiny R package (5.2.1) and examines various performance indicators, including publication trends, prominent authors, sources, and countries. The bibliometric analysis will produce a visual representation of the intellectual structure, revealing the dominant areas of research and how they are developing over time [24,25]. The thematic analysis follows Braun and Clarke’s 6 phase approach [26]. First, the researchers will read the abstracts and conclusions of the studies. The researchers will create initial codes based on similar concepts emerging in studies on parental practices, financial education, family processes, psychological mediators, and behavioral outcomes. The researchers will cluster these initial codes and create overarching themes. Themes will also be revised to create a coherent relationship between the themes and the bibliometric network structures. This methodology yields a thorough, systematic and dependable analysis of parental financial socialization and financial behavior research.

3. Findings

3.1. Publication Trend

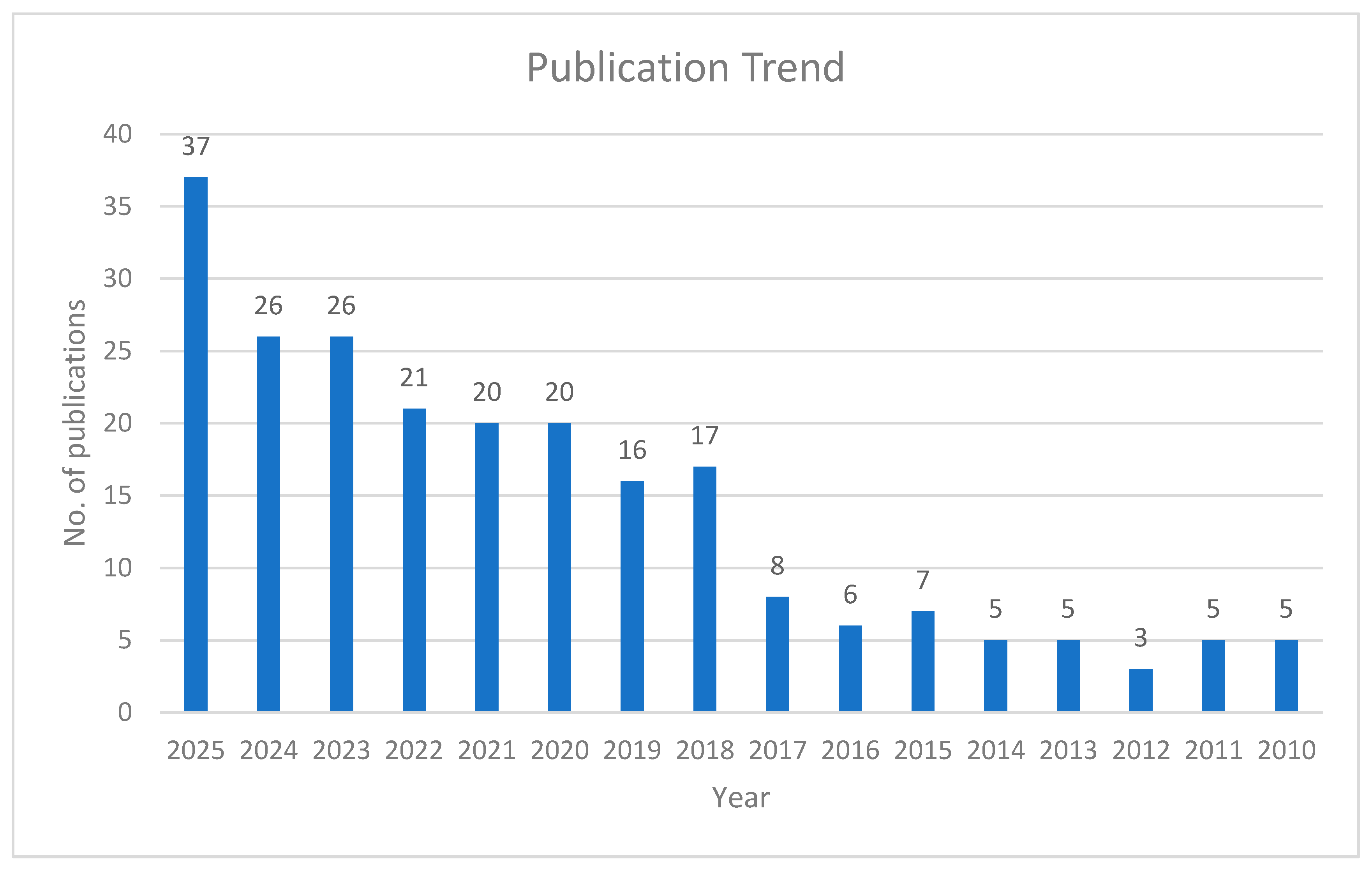

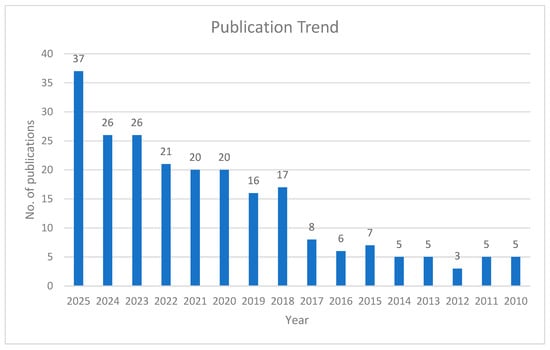

Figure 1 shows the publication trend on research related to parental socialization and financial behavior. A rise in research related to this domain is evident, as demonstrated by the growth of research from a minimal output of 3 publications in 2012 to a peak of 37 publications in 2025. The increasing number of studies coincides with post-COVID scholarly awareness of the role of parental and family socialization in creating financially capable individuals. Rising household debt, financial instability among young adults, and the increasing complexity, volatility, and vulnerability of financial products due to digitization have played a pivotal role in the surge in research within this domain. Additionally, digital financial platforms (e.g., Wise, Apple Pay, and GrabPay) have shifted responsibility from physical institutions to consumers, i.e., buyers need to be aware and accountable for their actions and consequences. These situations have created a need for parental intervention to expose young adults to financial coping strategies and educate them about them. There is a growing consensus among policymakers, educators, and researchers that the complexity of today’s financial systems means financial literacy programs alone will not fill the gap created by behaviors resulting from being unprepared for financial management. Thus, renewed research interest in the way parents’ financial socialization (modeling, communication, and joint financial activities) predicts the financial behaviors of their children has emerged. Studies conducted internationally (OECD/PISA assessments) have also revealed disparities in the financial capability of youth in various countries, prompting research into cross-country disparities on financial capability. Collectively, these drivers have elevated parental socialization from a peripheral topic to a central focus in financial capability research, explaining the strong upward trend in publications and reinforcing the relevance of the present study.

Figure 1.

Publication trends of parental socialization and financial behavior. Source: Scopus database.

3.2. Prominent Source and Publishers

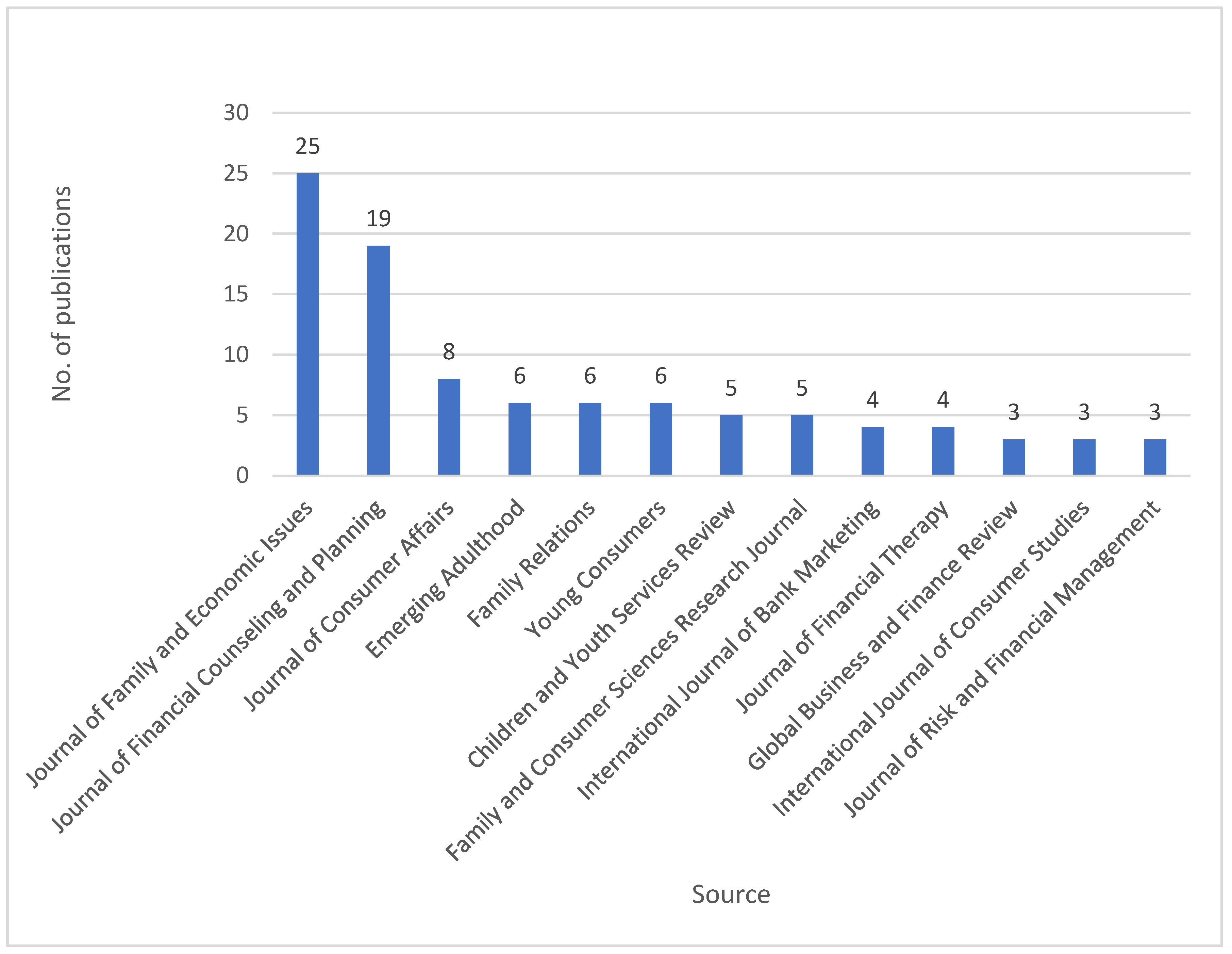

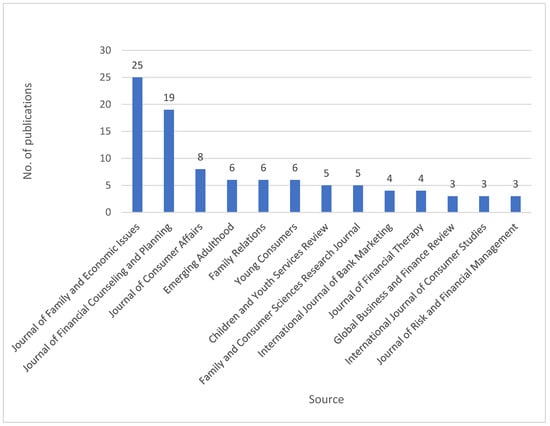

Publication of articles (Figure 2) related to parental financial socialization, financial capability and financial behaviors in established academic journals and publishers is a testimony on the importance and relevance of the current scholarly discussion. Parental financial socialization is one of the dimensions of financial literacy which has significantly increased in the peer-reviewed publication landscape. In this regard, the Journal of Family and Economic Issues leads in terms of total number of articles published (25), which is consistent with this journal’s historical focus on promoting family economic well-being and intergenerational financial processes. Next is the Journal of Financial Counselling and Planning (19), which emphasizes the importance of applied financial behaviors and financial education/counseling within the context of parental influence and capability formation. Other established journals publishing articles pertaining to parental financial socialization are the Journal of Consumer Affairs, Emerging Adulthood, Family Relations, and Young Consumers, suggesting that there is much interest from multiple disciplines examining this area of study. Publication in these journals also indicates that parental financial socialization has moved beyond being considered an emerging area of scholarly work to established scholarship within the realm of family finance. It illustrates the emergence of recognition by researchers that early-stage family learning about finances plays a critical role in determining a person’s financial future success. The above sources/journals are published by established publishers such as Springer, Wiley, SAGE, Emerald, Elsevier, and MDPI, further underscoring the importance and the impact of parental financial socialization on financial related matters, in an environment beleaguered by economic uncertainty, and complicated financial systems.

Figure 2.

Prominent journals publishing research on parental socialization and financial behavior. Source: Scopus database.

3.3. Prominent Authors in Parental Financial Socialization Research

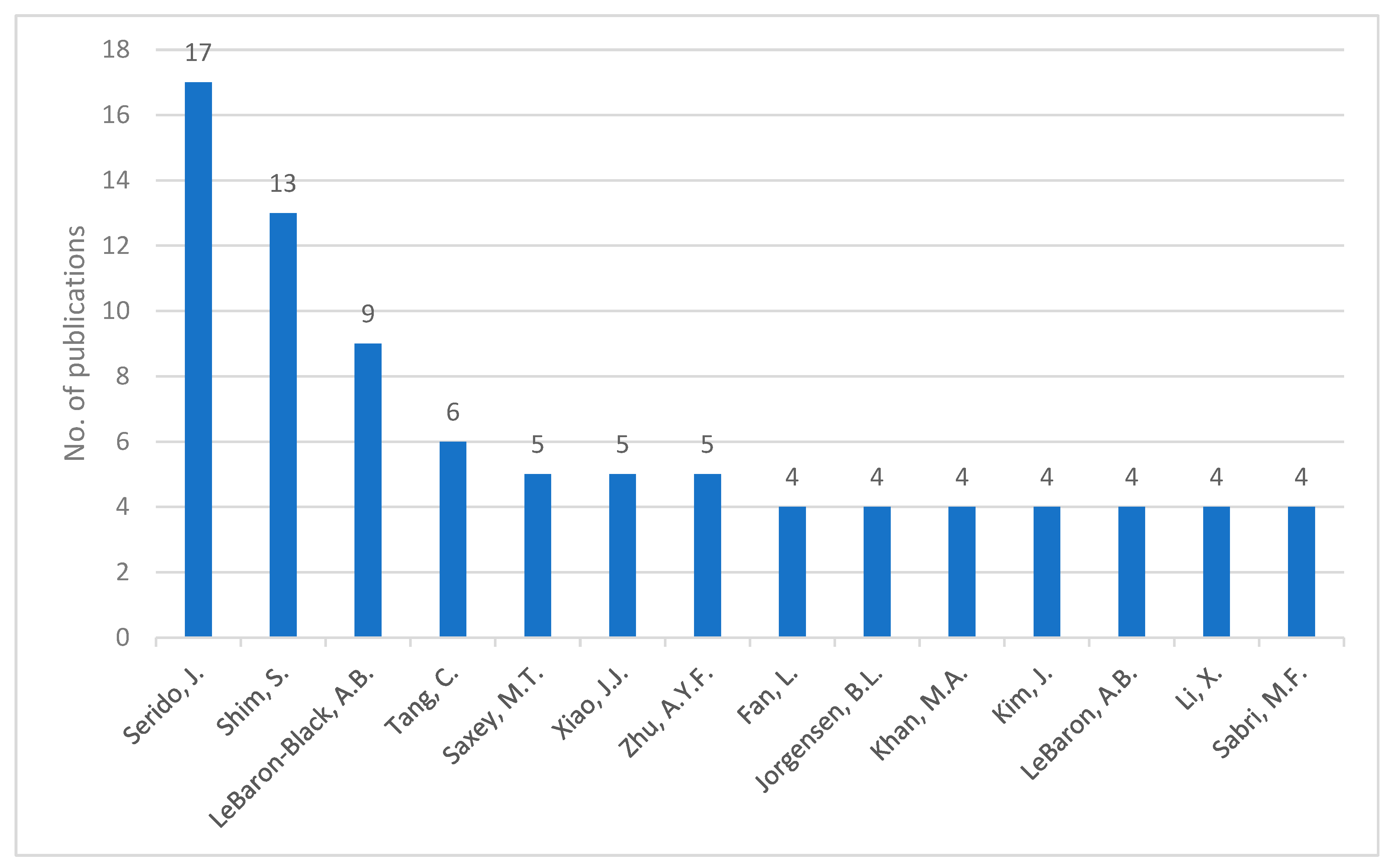

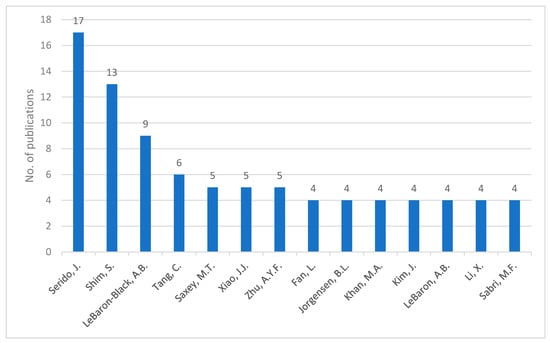

The leading researchers in parental financial socialization (Figure 3) are Joyce Serido, Soyeon Shim, and Ashley B. LeBaron-Black, who are noted pioneers in this domain of research. Joycce Serido (University of Minnesota) has published numerous articles and book chapters on the impact of family financial experiences on the financial well-being, saving and credit behaviors of emerging adults. Soyeon Shim (formerly with several universities including the University of Arizona) has developed models linking how parents influence their children’s financial attitudes and behavior, which has formed the basis for subsequent research on financial socialization and financial attitudes of college students. Ashley B. LeBaron-Black (Brigham Young University) conducts research on intergenerational financial processes, family financial communication, and financial socialization across socioeconomic categories. In addition to these three well-known researchers, several other active researchers in this area include C. Tang and M.T. Saxey, whose work consistently sits at the intersection of behavioral finance and financial decision-making among youth. J.J. Xiao (University of Rhode Island) has extensively contributed to the area of consumer finance, developed financial behavior models, and has designed frameworks to measure financial well-being. A.Y.F. Zhu, L. Fan, B.L. Jorgensen, M.A. Khan, J. Kim, and M.F. Sabri have also contributed to the area of financial literacy education for adolescents, the use of credit, and culturally based financial socialization. Collectively, these authors represent a multidisciplinary network spanning from family science, consumer economics, behavioral finance, and youth development. Their affiliations with reputable universities underscore the growing academic significance and global recognition of research on parental financial socialization.

Figure 3.

Prominent authors on parental socialization and financial behavior publications. Source: Scopus database.

3.4. Regional Analysis on Parental Financial Socialization Research

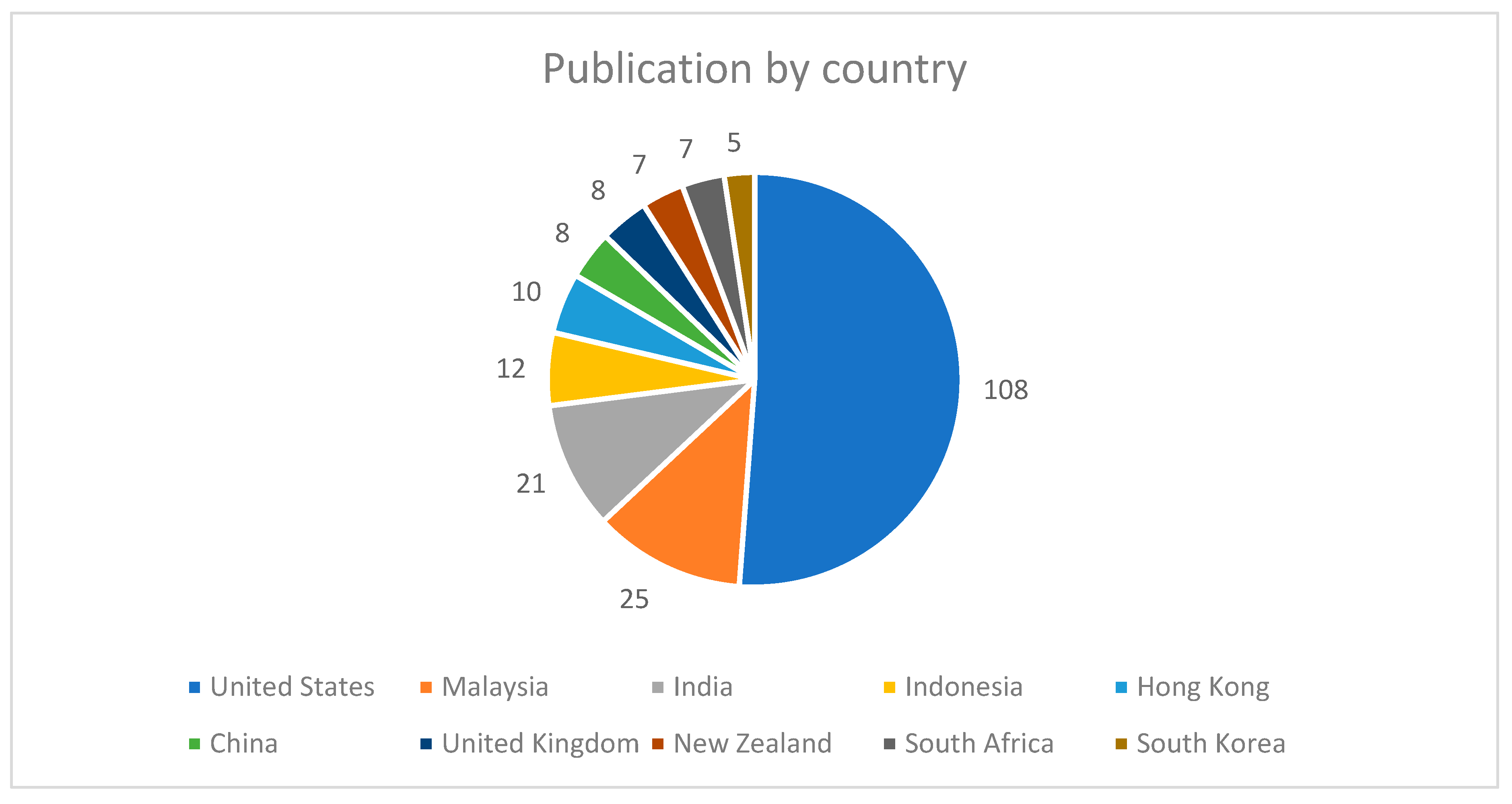

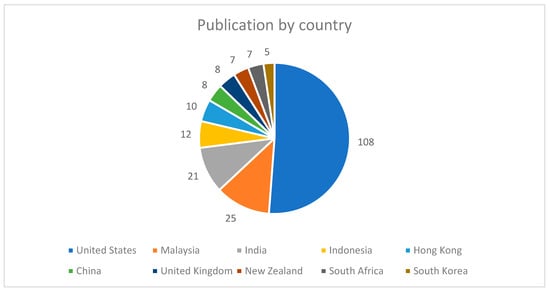

The publication distribution (Figure 4) shows a striking geographical concentration, with the United States producing 108 articles, far surpassing those of any other country. Malaysia follows distantly with 25 publications, while India (21), China (12), Hong Kong (10), Indonesia (8), South Africa (8), and South Korea (7) contribute moderately. Other regions, including the United Kingdom and New Zealand, show minimal output with only five publications each.

Figure 4.

Country contribution on the publication output on parental socialization and financial behavior. Source: Scopus database.

This dominance reflects a heavily US-centric research publication on parental financial socialization. This could be attributable to the long-standing academic interest in parental financial socialization, financial literacy, and household finance in the U.S., supported by established research infrastructures, national surveys, extensive household datasets, sustained interest in family and consumer finance by established researchers, and strong funding for behavioral and family finance research. Research in this domain also appears to be relatively prominent in Asian countries (China, India, Malaysia, Hong Kong, Indonesia, South Africa, and South Korea), mainly because parents and families play a key role in shaping young adults’ financial outcomes. In contrast, moderate contributions from the United Kingdom and New Zealand could reflect effective formal financial education, institutional support, and effective and established welfare systems rather than parental financial socialization being the critical factor affecting the financial behavior or well-being of young adults.

Nevertheless, given that family financial norms, parental roles, and cultural attitudes toward money vary widely across societies, the lack of global representation restricts the generalizability of existing theories. There is a need for more regionally diverse and culturally grounded studies to capture alternative socialization patterns, informal financial practices, and culturally specific determinants of financial capability. Broadening geographical coverage will enhance theoretical robustness and support more inclusive policy recommendations.

3.5. Thematic Analysis

An examination of the top-cited studies in the field reveals a coherent but multi-layered body of knowledge on how parental and family financial socialization shapes young people’s financial outcomes. Rather than a single homogeneous stream, these highly influential works cluster around four interrelated themes: (1) mechanisms of parental financial socialization; (2) financial outcomes across the life course; (3) psychological mediators of socialization effects; and (4) contextual moderators such as culture, socioeconomic status, gender and institutional structures. Together, these themes provide the empirical and conceptual foundations for developing an integrated model of parental financial socialization and behavior.

- Theme 1: Mechanisms of Parental Financial Socialization

Theme 1 discusses “Parent and Family Socialization of Children about Money”. Multiple complementary theoretical perspectives explain how financial information (knowledge, attitudes, behavior) is shared from one generation to the next. Social Learning Theory [27] describes how parents model their own financial behaviors and how their children learn to behave similarly. Children’s ability to learn financial behaviors from their parents is based on a four-stage process: (1) Attention (observing their parents’ financial behavior), (2) Retention (Recalling what they have witnessed), (3) Reproduction (Acquiring the same skills) and (4) Motivation (getting support to continue with the same pattern). Reference [17] provided the first major empirical research on parental influence on financial attitudes and behavior through their study of a four-level financial socialization model used by first-year college students. The authors determined that parents, work, and high school financial education combinedly have a strong influence on the financial learning, attitudes, and behavior of the students. Their findings explicitly describe parental socialization as a combination of modeling, communication, and opportunities for financial practice. Similarly, the authors of [18] found that the influence parents have on their children is important when developing their financial attitudes and that parents also impact their children’s behaviors.

Through the lens of Family Systems Theory, one can understand better the interactive processes of financial communication and climate as they shape the overall context of the family’s financial environment. In other words, the family does not simply pass down an established or predetermined view or belief regarding how to manage money. In fact, economic factors are created in the ongoing emotional dynamics and interactions between family members. Additionally, the financial climate within the family is created via their conversations with one another (e.g., through explicit teaching), as well as by implicit factors such as the emotional context of a conversation surrounding money, the degree of conflict or harmony surrounding money between parents, and the stress levels of parents. The experiences of [28] with college students demonstrate that the ways in which parents teach and model financial behavior affect how students use credit cards, their overall debt level, and their approach to budgeting. Reference [29] demonstrates that there is a strong correlation between parental financial knowledge and adolescent financial literacy. This supports the idea that intergenerational learning is a product of the familial environment, particularly through informal or everyday conversations about money.

A Life-Course Perspective allows us to observe how children’s experiences with money provided by their parents (allowances, savings accounts, joint money decisions) offer uniquely timed interventions that accumulate throughout the development process of childhood, adolescence and emerging adulthood. Children’s initial experiences with money create the first foundational ‘scripts’ or mental frameworks that will be continued through the various stages of their life, with each stage building upon the previous stage’s learning. Reference [19] combined 10 years of research and developed three paths of family financial socialization by a parent to his/her child (through parental modeling, parent–child discussions of money and experiential learning) in an intentionally/unintentionally manner and within the context of the overall family climate. Distinct from purposeful and unintentional financial socialization, ref. [30] argues that purposeful and intentional financial socialization occur through the direct involvement of students in earning an income and through intentionally teaching students financial concepts. Unintentional financial socialization occurs through observing parents engaging in daily financial behaviors (financial management) and being distressed about money. However, in distinct ways, both forms of socialization have an impact on financial knowledge and behavior. The combination of purposeful and intentional financial socialization creates the strongest effect on children’s financial knowledge and attitudes, their sense of self-efficacy, and ultimately, their financial behaviors. Research repeatedly supports the notion that students gain more knowledge and develop positive attitudes about money when they are intentionally taught financial concepts along with observing their parents modelling desirable financial behaviors.

As a whole, the extant literature within this theme and their corresponding theory have demonstrated that the financialization of children by their parents is not one specific activity, but rather consists of many different activities that work together to develop the internal representation of money in children. The combination of the Social Learning Theory, the Family Systems Theory and the Life-Course Perspective, as well as the Family Financial Education Theory, allows for a full understanding of why and how these methods develop long-term financial competence, Attitudes and Behaviors that continue into adulthood.

- Theme 2: Financial Outcomes Across the Life Course

The second theme examines the financial socialization outcomes concerning financial literacy, financial behaviors, financial independence and wealth accumulation over time. Theories of Financial Capability, Theory of planned behavior [31], and Principles of Behavioral Economics explain how the financial socialization process affects measurable financial behavior across different developmental stages of the individual. The Theory of Planned Behavior states that the intentions of individuals shape their behavior. This is influenced by their attitudes, their beliefs regarding the subject (subjective norms vs. the parenting process), and their ability to carry out that behavior. Due to these components of the theory, the influence of parents on children is both direct and indirect, as it occurs through the development of normative values about financial behavior.

Financial Capability Theory is more than simply possessing financial literacy; it also includes being capable of acting on this knowledge and having the opportunity to carry out actions based on it. This interaction of individual capabilities (knowledge, skill, and confidence) with environmental factors (access to financial services, other sources of institutional support, and economic wealth) has an effect on financial behaviors and outcomes. Behavioral Economics can provide further insight into how parental socializing can influence our decision-making processes by means of biases, heuristics, time-preferences and self-control mechanisms. These processes ultimately determine whether individuals will create optimal financial decisions despite the fact that they have a sufficient amount of financial knowledge.

Numerous articles have quantified the impacts of family processes on financial behavior through a set of theoretical constructs. Research presented in [32] focused on risky credit card behaviors, establishing that parental norms and socioeconomic status significantly predict young adult credit card behaviors within an expanded Theory of Planned Behavior framework. Their findings indicate that parental messages regarding credit create an individual’s subjective norm concerning the appropriate and responsible use of credit cards. This in turn, influences an individual’s intent to be responsible in their use of a credit card, and that these norms are as powerful, or even more powerful, than formal financial education. These findings illustrate that earlier socialization establishes behavioral norms, as well as risk thresholds, that continue to exist as individuals transition to emerging adulthood. Reference [33] adopted a developmental framework and demonstrated that the positive change in how a young adult perceives parental socialization leads to an increase in positive financial attitudes, financial efficacy and perceived control, which ultimately contribute to healthier financial behavior over time. Importantly, longitudinal analysis demonstrates that the ongoing positive impacts of parental socialization on young adults’ financial behaviors continue to develop as they attain financial independence. This indicates that parents’ early childhood socialization cultivates adaptive behaviors that assist young adults in coping with new financial behaviors and various financial situations as they challenge their financial independence.

Beyond immediate behavioral outcomes of compliance, the result of parental financial socialization is a broader capability, indicating multidimensional outcomes of financial well-being. Reference [34] emphasized three aspects that were significantly related to young adults’ perception of their financial independence; economic resources (e.g., income, assets), psychological capabilities (e.g., self-efficacy regarding finances, problem solving) and family-related influences (e.g., level of parental income and availability of financial assistance). Their research indicated that having a parent provide financial assistance may reduce the perception of independence. Therefore, they demonstrated how over-supporting a child financially affects how this type of parenting creates a challenge for parents to provide support to their children while encouraging independence. This study shows that to effectively parent, optimal socialization occurs when the knowledge gained from the socialization process is accompanied by the gradual transfer of financial responsibility as children grow. Therefore, the term financial independence not only describes the competencies developed through financial socialization but also reflects the psychological preparedness necessary to manage finances independently.

Reference [35] connects sibship size and lower levels of wealth as an adult through reduced parental resources, education, and transfers, suggesting that financial socialization and family structure serve as early roots of wealth inequality. The study suggests that family resource allocation patterns created during childhood have cascading consequences over decades that ultimately shape an individual’s total wealth accumulation and affect the intergenerational transfer of economic privilege or disadvantage. It highlights how the parental financial socialization process occurs within an environment of limited resources. Larger families will be required to split their time, invest in educating their children and financially support them in a way that is less concentrated than a family with fewer children. This leads to a decrease in the degree of intensity of the financial socialization for each child. Lastly, the findings link micro-level family processes to macro-level patterns of economic stratification, demonstrating how parental financial socialization is both a means of social reproduction and a potential source for intervention to address reduced inequality.

Even when studies focus primarily on knowledge, outcomes are central and are interpreted through the capability framework. For example, the teen–parent study presented in [29] and the European multi-country university literacy study [36,37] on Malaysian students all document generally modest levels of financial literacy but also show that early family financial experiences—such as discussing finances with parents—are strongly associated with higher literacy. However, these studies collectively reveal the persistent knowledge–behavior gap: increased financial literacy alone does not automatically translate into improved financial behaviors without corresponding development of confidence, self-efficacy, and opportunity structures. This gap reflects the distinction between financial knowledge (cognitive understanding), financial capability (knowledge plus skills plus access), and financial behavior (actual observable actions). Parental socialization influences all three levels, but its effects on capability and behavior may be more powerful and enduring than its effects on knowledge alone, because socialization shapes motivational and volitional factors—such as financial self-concept, perceived control, and future orientation—that determine whether knowledge is activated in real-world financial decisions.

Parenting also affects how children develop self-control, time preferences, and the ability to resist immediate biases that hinder optimal financial decision-making according to behavioral economics. Parents who model delayed gratification consistently save money despite the pressures of immediate consumption and explicitly discuss the trade-offs between their current and future needs, assisting children in forming internalized time-consistent preferences and develop the executive function skills that support long-term financial planning. In contrast, parents who display an inclination to make impulsive purchases and have difficulty delaying gratification tend to pass these behavioral traits on to their children. This can create intergenerational cycles of under-saving, overwhelming amounts of debt, and vulnerability to financial crisis.

Collectively, the literature indicates that the primary means by which parents socialize their children financially acts as an antecedent to many financial aspects throughout an individual’s lifetime, from short-term budget management to long-term wealth accumulation. Furthermore, these financial outcomes demonstrate not only what children have learned about finances, but also how their family experiences create their financial identity, financial capability, self-regulatory ability, and access to financial opportunities across their lifespan. The theoretical integration of the Planned Behavioral Theory, Capability Theory, and Behavioral Economics demonstrate that optimal outcomes occur when alignment exists across cognitive (knowledge), affective (attitude/motivation), behavioral (skills/habits), and structural (resources/opportunity) dimensions. Each of these dimensions is dramatically influenced by parents through their financial socialization processes. This three-dimensional outcome framework illustrates why most interventions that focus exclusively on providing financial literacy education result in few or no behavioral changes. In fact, they focus on only one of several complex developmental components through which parental influence affects financial behaviors over multiple developmental stages.

- Theme 3: Psychological Mediators of Socialization Effects

While Theme 1 identified the mechanisms and Theme 2 documented outcomes achieved, Theme 3 addresses the psychological processes through which parental influence is internalized and expressed in financial decision-making. Several top-cited studies explicitly model attitudes, self-efficacy, self-control, and perceived control as mediating constructs, drawing on Social Cognitive Theory, Theory of Planned Behavior, and Money Script Theory.

Financial attitudes are evaluative judgments that serve as a bridge between parental socialization and financial practice across several domains. Saving is associated with the perception that saving money is both important and possible, depending on what parents model and the message that parents send about financial safety and security. Attitudes about borrowing (debt) and credit are related to the perceived acceptability of borrowing. Children whose parents exhibit careful borrowing behavior develop conservative borrowing attitudes, and therefore, have lower credit card uses on average. Attitudes regarding consumption and materialism are associated with the perceived link between possessions and happiness; therefore, children of parents who value intrinsic values will likely exhibit less materialistic attitudes than children of parents who do not place a high value on intrinsic values and who practice sustainable spending habits. Finally, attitudes about planning their finances and risk will determine long-term behaviors (e.g., retirement planning, risky investments). Reference [18] demonstrated that parental influence impacts behavior through attitudes toward money. Parents teach children how to view money, and subsequently, children develop behaviors based on the beliefs associated with those attitudes. Reference [33] observed that having positive perceptions of the socialization processes of parents are significantly associated with progressively improving financial behaviors, as demonstrated by perceived controllability and perceived financial efficacy reflecting the most powerful predictors of improved financial behaviors among children. Furthermore, the longitudinal studies identified that changes in child attitudes are associated with changes in behavior, thus demonstrating that attitude serves as an intermediary connection between the learning process and eventual action.

The belief that one can successfully complete financial tasks, or financial self-efficacy, has been shown to be a significant mediator of human behavior. Based on Social Cognitive Theory, self-efficacies were developed via mastery experiences, observational experiences (observing parents), verbally persuading (encouragement) through messages from parents, and through their ability to control their emotions. Therefore, parents provide an all-encompassing position of financial self-efficacy for their children that allows them to feel confident in making sound financial decisions. Reference [38] clearly refers to the “knowledge-behavior disconnect” and provides a developmental model that demonstrates that knowledge, attitude, and perceived self-efficacy influence financial behaviors. In other words, knowledge is not predictive enough by itself to determine behavior. In addition, individuals with high knowledge but low self-efficacy frequently do not effectively apply their knowledge while individuals with moderate knowledge but high self-efficacy are more likely to engage in positive financial behaviors. Lastly, individuals who have high self-efficacy are also more likely to continue to engage in financial behaviors even after experiencing setbacks.

The degree of perceived behavioral control includes an individual’s belief regarding both their ability to perform financial activities easily, as well as whether the results of those actions can be controlled by either themselves or others (i.e., an internal/external locus of control). The ability to control one’s finances through proactive measures—such as planning ahead, placing money in safe accounts, and investing—contains strong links to perceptions of an internal locus of control. The way in which a parent socially combines the experiences their child has will determine how they perceive their own locus of control, based on whether their parent has focused on success due to their efforts and planning (internal), or through external sources (i.e., luck) or people (external), ultimately resulting in the development of learned helplessness.

Self-Control, the ability to resist short-term temptations and prioritize long-term goals, serves both as a mediator and a moderator. Self-control develops via parental modeling of delay of gratification, providing structured opportunities for savings, and teaching children techniques for regulating their impulses. Children who observe their parents making choices for the sake of long-term financial security rather than immediate consumption learn to internalize strategies for self-regulation. Self-control mediates the socialization–outcome connection and also moderates it. Individuals with high levels of self-control are able to apply the financial knowledge and positive attitudes acquired through socialization because, when tempted, they translate their intentions into action. Self-control is associated with both “hot” emotional processes through which individuals resist short-term temptations and “cold” cognitive processes where individuals plan and monitor their actions.

For individuals who have low levels of self-control, converting the financial knowledge gained through socialization into actual behavior is tougher and less consistent, resulting in variations among those who have received the same parental socialization. Executive function skills, such as working memory, cognitive flexibility, and inhibitory control, represent the neuropsychological underpinnings of financial self-control. Parents can aid the development of financial self-control through the use of cognitively stimulating financial activities and implementing predictable and structured routines. Executive function skills enable individuals to pursue multiple goals, adjust strategies, and suppress impulsive behaviors.

Money Scripts are unconscious and learned beliefs about money developed as children that can act as deeper psychological mediators that explain persistent behaviors. Four distinct Money Scripts can be identified: Money Avoidance (i.e., belief that Money is Evil), Money Worship (i.e., belief that Money equals Happiness), Money Status (i.e., self-worth equals net worth), and Money Vigilance (i.e., money should be saved). The creation of Money Scripts occurs through the education and experience of parents, and these scripts create cognitive-affective pathways that determine how we interpret financial situations. For example, someone who has Money Avoidance Scripts will often sabotage their financial success regardless of the quality of player’s education regarding finances. In comparison, someone with Money Worship Scripts will render themselves financially successful due to compulsive income generation regardless of how thoughtfully and balanced they were raised. The emotional messages provided by the parent often will overpower any knowledge stated verbally.

Time Perspective, which is a measure of how someone regards and prioritizes the past, present, and future when it comes to their behaviors, is another important area of discussion. According to [39], Time Perspective and the outcome of saving provide a substantial influence on the ways that individuals act with regard to savings and investment over an extended time frame. Children whose parents encourage them to think about their long-term financial goals and how their present behavior will affect their ability to accomplish these long-term goals will develop a “future” foundation for socialization and saving. The rewards of saving money are typically derived from the positive feelings that come from having security, pride, and progress, which is often an important part of developing the parents’ “socialization-saving” connection.

In conclusion, these studies indicate that psychological variables play a vital role in influencing how parents socialize their children regarding money, in addition to providing them with financial knowledge. For example, psychological variables influence how individuals feel about money, self-efficacy, control beliefs, ability to delay gratification, views on money, and their time horizons, which together influence how they behave with respect to money. The relationship between psychological variables and money-related behavior provides insight into the knowledge-behavior gap; the manner in which individuals differ in the way they respond to their parents’ socialization regarding money; and the persistence or decay of their behavioral response over time. Moreover, the interplay of these psychological variables creates an integrated system: Positive attitudes create motivation for self-efficacy, thereby increasing perceived control and creating an upward spiral. Conversely, strong self-control creates the ability to act on positive attitudes, while viewing the future enhances the motivational power of long-term goals. Therefore, to promote healthy financial development, it is necessary to address every psychological variable that affects how individuals think about and relate to money by developing adaptive thoughts, emotions, and behaviors associated with financial well-being.

- Theme 4: Socio-Cultural and Institutional Contexts as Moderators

The fourth theme addresses the idea that financial socialization processes and effects occur within larger systems of diverse factors such as culture, socio-economic status, gender, education systems, and government policy. These factors provide no consistent impact across all outcomes, but rather modify how parents socialize their children, and how much the resulting socialization translates into capabilities and behaviors. Therefore, understanding how cultural, economic, educational and institutional differences impact these moderating mechanisms can help explain why children from similarly situated families receiving the same types of parental financial practices produce disparate outcomes.

First, the relationship between parental socialization and financial outcomes is influenced differently by cultural factors through a set of various intertwined mechanisms rooted in the cultural values, norms, and overall social structure. For example, two contrasting cultural orientations, individualistic versus collectivistic, create a different meaning and purpose for financial behavior. In cultures that categorize individuals as independent (i.e., predominantly Western culture), those individuals tend to seek tangible evidence of independence through obtaining their financial status. This is evidenced in the emphasis placed by parents on supporting a child’s autonomy, encouraging personal responsibility, and supporting independent goal planning concerning the acquisition of wealth. The process by which parents provide financial guidance is through teaching the ability to be independent and achieving successful financial outcomes, whether by managing their finances independently or building up personal assets. Additionally, the relationship between socialization and materialism across cultures (i.e., comparing U.S. and Hong Kong youth) demonstrates that high levels of parental financial socialization may act to decrease materialism and unhealthy behaviors in one cultural context, while exhibiting the opposite effect in other cultures, particularly when the sacrifice made by parents to support their child’s financial goals is emphasized.

In collectivist cultures, which are prevalent in Asia, Africa and Latin America, there is a high degree of financial behavior interwoven with familial and intergenerational obligations. In this sense, it is crucial to note that parents do not raise their children to be financially independent individuals; rather, they raise them to assume responsibility for the needs of their family, care for their aging parents, contribute to their extended family and maintain their family’s honor. Therefore, parents teach their children about saving for purposes of being responsible, but the outcome of these teachings will differ considerably based on context. In individualistic contexts, individuals save for purposes of personal security and consumption. However, in collectivist contexts, individuals save for the purposes of fulfilling their filial and family obligations. Parental financial sacrifices also serve as very strong socialization mechanisms in the collectivistic cultures. These financial sacrifices of parents, which prioritize their children’s education over their personal consumption, are particularly significant in the context of socialization, as they instill in children two values: delayed gratification and sense of responsibility. Children who have observed parental sacrifice will develop an intrinsically strong motivation to be financially responsible, not simply for the sake of their own personal competence, but also as a moral obligation to honor their parents’ investment in them.

Second, cultural norms about discussing money moderate how parental communication translates into outcomes. In those cultures where money is viewed as a taboo subject, as is found in many Asian cultures, parents are likely to provide less direct and explicit types of financial education, relying instead on their own examples as role models. In those situations, more children will be required to use their observational learning pathways to determine the underlying principles of finance and as such, will result in more variability in the financial outcomes for children. Conversely, cultures that have more open financial communication have a greater capacity to share financial knowledge and values through family discussions. Reference [37] discovered that cultural norms, national financial systems and ethnic background all contributed to the level of financial literacy and the intensity of family investments in developing financial literacy. Therefore, the same degree of family investment will yield different financial literacy knowledge outcomes depending on the cultural communication norms of that particular culture.

Third, cultural beliefs regarding proper financial interaction between parents and their children influence the effects of parental financial assistance. In a Western context, the provision of continuing financial assistance is frequently associated with feelings of failure to achieve independence and lack of self-efficacy, as illustrated by research conducted by [34]. In contrast, in collectivistic cultural contexts, adult children receiving financial assistance from parents is considered to be typical behavior that demonstrates family connection and support rather than dependence. Thus, the same behavior of parents in terms of providing financially continues to influence the relationship between parental socialization and child outcomes very differently in individualism versus collectivism.

Parental socialization is determined by the opportunities and resources available in both structural and institutional forms. The socio-economic status (SES) of the family also moderates the effects of socialization on the child through a number of pathways. Families with a higher SES have greater access to financial resources that allow them to provide experiential learning opportunities to their children (bank accounts, investment accounts, and supervised spending), a greater opportunity to access financial services and institutions, and the ability to provide a buffer for their children’s financial mistakes. Thus, this builds an environment for learning that is more forgiving than the environment in which children are raised by lower SES parents. The financial behaviors demonstrated to children by parents in high SES contexts include sophisticated financial behaviors (e.g., investing, tax planning, estate management), which result in the development of complex financial competencies. Families of low SES often model financial behaviors that display strong values and behaviors associated with prudent money management. However, the financial resources available to these families are limited, which restricts the opportunity for children to experience financial learning through experience and the likelihood that children will experience stress associated with their finances, which may impact their ability to have self-efficacy and perceived control.

The findings presented in [35] regarding how the size of a sibling group and the level of wealth inequality impact socialization processes suggest that family composition and resource dilution influence the effectiveness of socialization. The larger the sibling group, the greater the financial resources, time, and educational investments divided among the children. As a result, each child receives a lower intensity of socialization compared to children from smaller sibling groups, and the amount of resources available for experiential learning is further decreased. Therefore, the accumulation of wealth during adulthood is reduced. Thus, the findings indicate that the process of parental socialization is undertaken within resource limitations that affect the effectiveness of socialization no matter what the intentions or level of knowledge of a parent.

Educational systems and policies create institutional environments that can augment or act as substitutes for parental socialization. Reference [40] presents an evaluation of high-school financial education in Brazil, displaying that education based on a curriculum significantly increases financial knowledge and, to some extent, influences behavior. However, these positive effects will vary according to the level of implementation intensity and local conditions. Most importantly, formal financial education appears to be more effective when it is used in conjunction with parental socialization. The strongest outcomes were found when the messages equally reinforced both from school and home. In countries where formal financial education systems are weak, parental socialization plays a significant role in developing financial capabilities. This results in a relatively high level of inequality, as it depends upon the resources possessed by the family and the knowledge possessed by the family. Conversely, where comprehensive institutional supports exist, parents are assisted in partially compensating for their limited level of socialization, and thus, the strength of the relationship between the family and the child’s outcomes can be moderated.

The relationship between parents’ desire to socialize financial behavior and the outcome of this socialization is also influenced by the regulatory environment. The Credit Card Act provides insight into this relationship through the way risky behavior associated with credit cards is regulated within a regulatory framework that both constrains and directs young adults’ behavior in regard to financial practice [32]. Ref. [36] provides insights into how regulatory environments across multiple countries affect parents’ ability to translate their socialization of financial behaviors into the capability to save or the perception of financial security. For example, individuals’ planning behaviors with regard to retirement, savings and creating a financial plan in the future do not affect financial well-being when social insurance and retirement savings exist. This weakens the relationship between socializing children with a view towards financial security with financial security itself. Conversely, when individuals have limited access to social insurance and retirement savings, parents must educate their children to save and plan for financial security, thereby strengthening the relationship.

Taken together, these studies make clear that financial socialization is not a universal, context-free process. Instead, its forms and consequences are contingent upon cultural values that define the purpose and meaning of financial behaviors, economic structures that provide resources and opportunities for learning, institutional frameworks that complement or substitute for family influence, and intersecting social identities (including gender and ethnicity) that shape expectations and opportunities. Understanding these moderating contexts is essential for developing culturally appropriate interventions, explaining heterogeneous research findings across populations, and recognizing that effective parental financial socialization practices in one context may require adaptation in others.

In conclusion, prominent studies in this field collectively support a multi-level, integrated view of financial socialization. They show that (a) parents and families shape financial development through multiple, often overlapping socialization mechanisms; (b) these processes are strongly linked to a wide range of financial outcomes; (c) psychological constructs mediate much of this influence; and (d) cultural, socioeconomic and institutional contexts moderate both processes and outcomes. This thematic synthesis provides a strong conceptual foundation for the present study’s conceptual model, which positions parental financial socialization as a key driver of financial capability and behavior, operating through psychological pathways and within specific socio-institutional environments. Table 1 shows a summary of mapping prominent articles across four themes.

Table 1.

Mapping the Top Most Cited Articles Across the Four Core Themes.

3.6. Themes, Theoretical Mapping, and Future Research Directions

Table 2 shows the four overarching themes identified in the review, maps each theme to its underlying theoretical foundations, and outlines targeted future research directions that address current gaps, extend existing frameworks, and advance a more integrated, multi-level understanding of financial socialization and behavior.

Table 2.

Themes, Theoretical Mapping, and Future Research Directions.

4. Conclusions

The purpose of this study is to systematically examine the evolution, intellectual foundations, and thematic patterns of research on parental financial socialization and financial behavior. Although financial literacy and financial behavior have been widely studied across economics, psychology, family studies, and consumer behavior, the field remains conceptually fragmented, with limited integration across parental, individual, and institutional levels. This study sought to address these gaps by conducting a comprehensive mixed-method review that synthesizes six decades of scholarship (1963–2025), integrating both bibliometric science mapping and qualitative thematic analysis.

The methodological approach consisted of four key steps, the first of which was the execution of a structured search query in the Scopus database to identify all available published research related to the topics of parental socialization, financial capability, and financial behavior and ultimately resulted in the final dataset of 219 peer-reviewed studies that met the criteria. All identified studies were evaluated using PRISMA’s guidelines and methods and analyzed via bibliometric analysis (i.e., counting and categorizing citations/references). Second, a qualitative thematic analysis based on Braun and Clarke’s methods was conducted on all identified abstracts and findings to discover underlying conceptual meanings. Initial codes were developed based on recurring concepts. These codes were then grouped into higher-order themes related to parental practices and processes, behavioral outcomes, psychological mediators, socio-cultural, institutional context and education. By utilizing a mixed approach, both methodological rigor and conceptual depth were attained.

In the research landscape, there are four themes that characterize the research landscape collectively; they are: (1) Mechanisms of parental and family financial socialization, (2) Financial outcomes from family financial socialization, (3) Psychological Mediators of Socialization Effects, and (4) Socio-Cultural and Institutional Contexts as Moderators. The first theme shows that the earliest and most powerful influence on financial identity is the parental modeling, communication, experiential learning and overall Financial Socialization Climate within the family. In line with Social Learning Theory, Family Financial Socialization Theory, and Family Systems Theory, it shows that children internalize financial norms and expectations through observing and interacting with their parents in their daily lives and developing their cognitive and emotional responses to financial information. Instead of being a one-time event, socializing and financial identity formation occur continuously throughout development based on the relational and emotional climates of families and their parental roles. The second theme indicates that financial behavior is not something that is automatic, nor is it only dependent on having knowledge about financial information. Financial capability and long-term outcomes result from the interaction of family socialization (early socialization), motivation, structure, and opportunities. This aligns with the Theory of Planned Behavior, Financial Capability Theory, and Behavioral Economics. It is consistently shown that literacy improvements—either developed at home or at school—are not sufficient to create changes in actual financial behaviors without corresponding changes to self-efficacy, behavioral control, and opportunity structures.

The third theme reflects a strong association between financial decision making and the influence of psychological mediators. Psychological factors such as money scripts, financial anxiety, locus of control, materialism and time perspective, etc., determine if a person’s early socialization into their family will lead to healthy vs. unhealthy financial behaviors. This theme also contains the social-cognitive, and socio-emotional framework as discussed above. The fourth theme points out that evidence from the US, Asia, and cross-cultural studies have also shown that the same parental behaviors can lead to very different results based on cultural expectations, and socio-economic pressures. Educational programs, institutional structures, and policy interventions can support and complement financial capability through school-based education, national curriculum reform, fintech innovation, and regulatory policy. However, evidence indicates that school-based education programs, national curriculum reform, fintech innovations, and regulatory policy can only enhance financial capability when they complement the family context within which the family is socializing with money and when the child is psychologically ready. This is consistent with institutional theory, capability approach, and policy feedback theory which show that structural interventions are most effective when they collaborate with rather than supplant family socialization.

These themes have significant theoretical contributions. The persistent gap between parental financial socialization and observed financial behavior indicates that financial knowledge gathered through family socialization does not automatically translate into action, highlighting the mediating role of psychological factors and institutional contexts. Financial socialization is best conceptualized as an integrated multi-level system that reflects the parents (family), individual (psychological), and contextual/structural (institutional) influences placed upon the individual, rather than treating these influences as independent of one another.

The results of this research can be utilized by all stakeholders to further enhance the role of parents and family as critical socialization agents in influencing the financial behavior of individuals. Policymakers should develop programs that focus on educating parents as well as children about managing money and finances. Policymakers should also be aware that parents influence their children’s behavior through several means, including modeling, communication, and actual experience in managing money. Policies should create an environment where families can have more influence on the financial behavior of their children rather than replacing the family influence. Financial educators should focus more on providing experiential opportunities to create capabilities in parents and children, including developing self-efficacy, attitudes toward money, and controlling spending. Financial educators can provide parents with guidance on when it is appropriate to talk to their children about money and how to provide their children with opportunities to experience different types of financial experiences. Financial institutions should offer family-oriented products and services to aid parents and children in learning about finances together. Furthermore, they should also develop product and service offerings that take into account the family context and cultural background of the family.

Employers should develop financial wellness programs that support families, including providing educational workshops and matched savings programs that allow parents to model positive financial behaviors. Employers should also support the culturally diverse ways in which families manage their finances. As for parents, the daily financial activities—including conversations, the visibility of money management, parental reactions to financial stress, and how they help their children gain experience with managing finances—play an impactful role in shaping the long-term development of their child’s financial competency. Parents also need to match their verbal and non-verbal communication to their children. From an academic perspective, researchers are encouraged to employ longitudinal studies that reflect the full experience of financial socialization in real-world environments, take cultural differences into account, examining how financial technology affects the financial socialization experience, and develop outcomes that address the emotional factors surrounding financial literacy and behavior. Collectively, these activities could turn the financial socialization process from an unconscious, unstructured experience into a conscious, intentional way for parents to provide their children with the tools required to be financially independent in their adult lives.

Overall, the review highlights the critical role of parental financial socialization as a foundational element that influences financial behavior throughout one’s lifetime. The combination of bibliometric mapping and thematic integration provides a coherent framework for understanding how families, individuals, and institutions create financial well-being over time. Additionally, it helps in the identification of several critical gaps requiring scholarly attention and in the design of a roadmap for future theory development and multiple future research opportunities. It also calls for the creation of a new generation of studies that take into account all aspects of the life course within a culturally relevant context and utilize a holistic, integrated approach to investigate how individuals behave in an increasingly complex financial environment. In that context, scholars should further emphasize real-life long-term financial behaviors, specifically in terms of the digital financial environment as opposed to self-reported surveys, as this could capture the real-life impact of parental and family socialization on the financial behaviors and well-being. The conclusion of this study is not merely descriptive but calls for a new generation of multi-level research that connects families, psychology, and public systems in a coherent, predictive model of financial behavior.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.S.; methodology, S.S.; formal analysis, S.S., K.K. and I.I.; data curation, S.S.; writing—original, S.S., K.K. and I.I.; writing—review, S.S., K.K. and I.I. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available upon request.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Prince Sultan University for the financial support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Chong, K.F.; Sabri, M.F.; Magli, A.S.; Abd Rahim, H.; Mokhtar, N.; Othman, M.A. The effects of financial literacy, self-efficacy and self-coping on financial behavior of emerging adults. J. Asian Financ. Econ. Bus. 2021, 8, 905–915. [Google Scholar]

- Hira, T.K. Promoting sustainable financial behavior: Implications for education and research. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2012, 36, 502–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, B.; Maury, R.V. Indicators of personal financial debt using a multi-disciplinary behavioral model. J. Econ. Psychol. 2006, 27, 543–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingale, K.K.; Paluri, R.A. Financial literacy and financial behavior: A bibliometric analysis. Rev. Behav. Financ. 2022, 14, 130–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyal, K.; Kumar, S. Financial literacy: A systematic review and bibliometric analysis. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2021, 45, 80–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lusardi, A.; Michaud, P.C.; Mitchell, O.S. Optimal financial knowledge and wealth inequality. J. Polit. Econ. 2017, 125, 431–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koskelainen, T.; Kalmi, P.; Scornavacca, E.; Vartiainen, T. Financial literacy in the digital age—A research agenda. J. Consum. Aff. 2023, 57, 507–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lusardi, A.; Messy, F.A. The importance of financial literacy and its impact on financial wellbeing. J. Financ. Lit. Wellbeing 2023, 1, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Bassa Scheresberg, C. Financial literacy and financial behavior among young adults: Evidence and implications. Numeracy 2013, 6, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fong, J.H.; Koh, B.S.; Mitchell, O.S.; Rohwedder, S. Financial Literacy and Suboptimal Financial Decisions at Older Ages. 2019. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3476319 (accessed on 7 September 2025).

- Hirvonen, J. Financial Behavior and Well-Being of Young Adults: Effects of Self-Control and Optimism. Master’ Thesis, University of Jyväskylä, Jyväskylä, Finland, 2018. Available online: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Financial-behavior-and-well-being-of-young-adults-%3A-Hirvonen/5a41960c9d889bd3db8cda90755a66530940c489 (accessed on 7 September 2025).

- Capuano, A.; Ramsay, I. What Causes Suboptimal Financial Behavior? An Exploration of Financial Literacy, Social Influences and Behavioral Economics. U of Melbourne Legal Studies Research Paper. 2011. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1793502 (accessed on 7 September 2025).

- Senarathna, G.H.N.; Anuradha, P.A.N.S. Impact of Financial Literacy and Financial Distress on Financial Wellness Among Public University Students in Sri Lanka. 2023. Available online: https://discovery.researcher.life/article/financial-literacy-and-financial-distress-on-financial-wellness-among-public-university-students-in-sri-lanka/fbe79aa5ac373eb298a7888e1bf264e1 (accessed on 7 September 2025).

- Fan, L.; Lim, H.; Lee, J.M. Young adults’ financial advice-seeking behavior: The roles of parental financial socialization. Fam. Relat. 2022, 71, 1226–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gudmunson, C.G.; Ray, S.K.; Xiao, J.J. Financial socialization. In Handbook of Consumer Finance Research; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 61–72. [Google Scholar]

- Van Campenhout, G. Revaluing the role of parents as financial socialization agents in youth financial literacy programs. J. Consum. Aff. 2015, 49, 186–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shim, S.; Barber, B.L.; Card, N.A.; Xiao, J.J.; Serido, J. Financial socialization of first-year college students: The roles of parents, work, and education. J. Youth Adolesc. 2010, 39, 1457–1470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorgensen, B.L.; Savla, J. Financial literacy of young adults: The importance of parental socialization. Fam. Relat. 2010, 59, 465–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeBaron-Black, A.B.; Kelley, H. Financial socialization: A decade in review. J. Fam. Econ. Issues 2021, 42, 560–575. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.; LaTaillade, J.; Kim, H. Family processes and adolescents’ financial behaviors. J. Fam. Econ. Issues 2011, 32, 668–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mongeon, P.; Paul-Hus, A. The journal coverage of Web of Science and Scopus: A comparative analysis. Scientometrics 2016, 106, 213–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Testa, J. The Thomson Reuters journal selection process. Transnatl. Corp. Rev. 2009, 1, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundarasen, S.; Kumar, R.; Tanaraj, K.; Ali Alsmady, A.; Rajagopalan, U. From board diversity to disclosure: A comprehensive review on board dynamics and ESG reporting. Res. Glob. 2024, 9, 100259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ejaz, H.; Zeeshan, H.M.; Ahmad, F.; Bukhari, S.N.A.; Anwar, N.; Alanazi, A.; Sadiq, A.; Junaid, K.; Atif, M.; Abosalif, K.O.A.; et al. Bibliometric analysis of publications on the omicron variant from 2020 to 2022 in the Scopus database using R and VOSviewer. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 12407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari, Y.; Arwab, M.; Subhan, M.; Alam, M.S.; Hashmi, N.I.; Hisam, M.W.; Zameer, M.N. Modeling socio-economic consequences of COVID-19: An evidence from bibliometric analysis. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 10, 941187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Social Learning Theory; Prentice Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Norvilitis, J.M.; MacLean, M.G. The role of parents in college students’ financial behaviors and attitudes. J. Econ. Psychol. 2010, 31, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danes, S.M.; Haberman, H. Teen financial knowledge, self-efficacy, and behavior: A gendered view. J. Financ. Couns. Plan. 2007, 18, 48–60. [Google Scholar]

- Deenanath, V.; Danes, S.M.; Jang, J. Purposive and unintentional family financial socialization, subjective financial knowledge, and financial behavior of high school students. J. Financ. Couns. Plan. 2019, 30, 83–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J.J.; Tang, C.; Serido, J.; Shim, S. Antecedents and consequences of risky credit behavior among college students: A conceptual model. J. Financ. Couns. Plan. 2011, 22, 15–29. [Google Scholar]

- Shim, S.; Xiao, J.J.; Barber, B.L.; Lyons, A. Pathways to healthy financial development: A socialization approach. J. Appl. Dev. Psychol. 2015, 38, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Y.; Ma, C.; Ding, R. Financial independence of young adults: The role of parental socioeconomic status and family financial socialization. Child. Youth Serv Rev. 2014, 42, 20–27. [Google Scholar]

- Keister, L.A. Sharing the wealth: The effect of siblings on adults’ wealth ownership. J. Popul. Econ. 2003, 16, 421–444. [Google Scholar]

- Lusardi, A.; Mitchell, O.S.; Samek, A. Financial literacy and financial education in universities: A cross-country comparison. J. Econ. Educ. 2018, 49, 264–278. [Google Scholar]

- Sabri, M.F.; MacDonald, M. Savings behavior and financial problems among college students: The role of financial literacy in Malaysia. Cross-Cult. Commun. 2010, 6, 103–110. [Google Scholar]

- Serido, J.; Shim, S.; Tang, C.; Card, N.A. Financial behavior of emerging adults: A family financial socialization approach. J. Fam. Econ. Issues 2017, 38, 298–312. [Google Scholar]

- Peetz, J.; Buehler, R. The Ant and the Grasshopper revisited: The role of time perspective in saving behavior. J. Econ. Psychol. 2012, 33, 118–124. [Google Scholar]

- Bruhn, M.; de Souza Leão, L.; Legovini, A. The impact of high school financial education: Experimental evidence from Brazil. Am. Econ. J. Appl. Econ. 2016, 8, 256–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]