Abstract

The living lab Enrekang, established in 2019 in South Sulawesi, Indonesia, was created to strengthen rural communication and support collaborative innovation across agriculture, livestock, environment, and extension services. Its flagship initiative, the Digital Farmer Field School (DFFS), was co-designed as a digital tool to improve farmers’ access to practical and locally adapted information. The early phase of collaboration generated strong momentum, culminating in a functional prototype tested with farmer groups by 2022. However, progress slowed soon after, revealing a gap between the initiative’s early promise and its subsequent stagnation. This qualitative case study, conducted between December 2024 and June 2025, draws on document reviews, focus group discussions, semi-structured interviews, and participant observations to analyze how the slowdown emerged and how it altered communication, coordination, and relational expectations among participating actors. Applying the governance-of-innovation lifecycle and a social capital lens, the study shows that political transitions, leadership turnover, staff rotation, and the absence of policy and budgetary anchoring disrupted coordination routines and reduced cross-sector interaction, even as motivation among farmers and frontline staff remained high. The case also highlights the novelty and complexity of the living lab approach, which introduced coordination demands and institutional unfamiliarity that local systems were not yet equipped to absorb. This study contributes to ongoing debates on collaborative innovation by illustrating the vulnerability of living labs when governance arrangements do not evolve alongside innovation milestones. Sustaining similar efforts requires formal anchoring, adaptive coordination, and mechanisms that protect collaboration across political and institutional transitions.

1. Introduction

Sustainable food systems are increasingly dependent on the capacity of rural communities and institutions to exchange knowledge, coordinate actions, and respond to emerging agricultural and environmental challenges. In many regions of the Global South, these capacities are constrained by fragmented institutional arrangements, limited communication channels, and uneven access to locally relevant information for the farmers [1,2] and other stakeholders involved. Collaborative approaches, such as living labs, have therefore gained prominence as promising means of strengthening cross-sector learning, supporting experimentation with new practices, as well as enhancing communication networks among diverse actors. Living labs are collaborative, user-centered spaces where diverse stakeholders work together to co-develop, test, and refine innovations in real-life settings [3,4]. Rather than functioning as fixed methodologies, they are better understood as collaborative approaches that emerge as flexible, adaptive arrangements that enable negotiation, iterative learning, and context-specific problem solving across institutions [5,6]. These characteristics make the living lab approach particularly relevant in Enrekang, where institutional fragmentation and limited communication channels hinder the coordinated support of farmers. Understanding how these collaborative approaches operate in practice is therefore essential for advancing communication strategies that support inclusive and adaptive food system networks, as emphasized in this Special Issue.

In Enrekang District, South Sulawesi, Indonesia, these challenges are particularly visible. Farmers often rely on informal sources of agricultural advice, whereas government institutions responsible for agriculture, livestock, the environment, and extension services operate largely within the sectoral boundaries. Recognizing these communication gaps, five local institutions and two universities initiated the living lab Enrekang in 2019 as an institutional platform to strengthen knowledge exchange and support coordinated actions. Within this collaborative environment, stakeholders jointly agreed to initiate the Digital Farmer Field School (DFFS) as an experimental initiative aimed at improving farmers’ access to practical, locally adapted information through a digital communication tool. As they embarked on this work, partners drew on their previous thematic and interdisciplinary experiences to recognize the importance of ensuring that the development process was transparent and grounded in mutual accountability. This shared understanding fostered a strong ethical sense of responsibility toward farmers, often expressed in the commitment that “we do not want to disappoint farmers” [7]. This shared value shaped the motivation to co-create a communication approach that genuinely responded to farmers’ needs and helped to establish a relational foundation for the work that followed.

Through iterative design cycles, partners developed early versions of the DFFS and, by late 2022, produced a testable prototype. The prototype sessions enabled farmers to explore the tool, provide structured feedback on usability, and articulate the types of information they hoped to access in future versions [8]. These interactions, along with observations from extension officers and institutional partners that the tool could complement existing communication practices, created broad expectations for further development. Farmers and field-level actors signalled readiness to continue, and the living lab was viewed as an important collaborative space for advancing the next phase.

However, these expectations did not match progress. After prototype testing, cross-sector meetings became infrequent, coordination weakened, and no clear pathway emerged for sharing responsibilities or continuing collaboration. The slowdown created uncertainty about how early commitments could be upheld, and raised questions about the institutional and relational processes that contributed to this loss of momentum. While the literature acknowledges that many living labs struggle to transition from early experimentation to more stable institutional practice—especially within decentralized and resource-constrained governance systems—[5,9,10] empirical studies offer limited insight into how it becomes difficult to sustain unfolds in practice or how it reshapes communication, interaction patterns, and relational expectations among actors. This lack of empirical understanding constitutes a critical gap, particularly in rural settings, where informal relationships underpin cooperation.

A central motivation for this study arises from both the ethical commitment expressed at the outset of collaboration and the broader risks faced by farming communities. The partners had promised to continue developing the DFFS in response to farmers’ needs, yet momentum stalled before this commitment could be realized. Simultaneously, growing environmental degradation in Enrekang poses an increasing threat to the sustainability of local food systems and the livelihoods of farmers who depend on them. Before considering how the initiative might be advanced, it was essential to understand why the living lab Enrekang was unable to maintain progress and fulfil the expectations that had been created among farmers. To address this concern, this study examines how the loss of momentum unfolded; how it reshaped communication, relationships, and expectations among farmers, extension officers, government agencies, and university partners; and what conditions are needed to sustain collaborative rural communication initiatives as they move from early experimentation toward more established institutional practices. Drawing on the governance lifecycle framework [11] and social capital perspectives [12], this study illuminates the institutional and relational dynamics that influence continuity, decline, and opportunities to revitalize collaborative work within the initiative.

Beyond contributing new empirical evidence, this study also offers a practical contribution. By unpacking how the loss of momentum develops and how it affects collaborative work, the findings provide a conceptual tool to support practitioners and institutional partners anticipate the governance vulnerabilities and relational risks that commonly arise in long-term multi-actor initiatives. In doing so, this paper supports both scholarly understanding and practical efforts to sustain collaboration in rural innovation settings.

2. Conceptual Framework

This study draws on two complementary conceptual perspectives—the governance lifecycle of collaborative innovation [11] and social capital theory [12,13,14]—to examine how structural and relational dynamics shape the evolution of multi-actor initiatives. The governance lifecycle framework provides insight into how coordination demands and governance arrangements change over time, while the social capital theory highlights how trust, shared norms, and interpersonal expectations influence the quality of collaboration. Together, these perspectives provide a coherent analytical foundation for examining how institutional conditions and relational processes interact in the development and stagnation of a living lab.

2.1. Governance of Innovation Lifecycle

The governance lifecycle framework distinguishes the adaptive processes through which collaborative initiatives evolve and offers a flexible lens for analyzing how coordination and governance arrangements shift as collaboration deepens [11]. It builds on broader insights from collaborative governance scholarship, which emphasize that multi-actor innovation unfolds within dynamic, non-linear environments shaped by shifting institutional expectations and evolving actor configurations [15].

The governance lifecycle conceptualizes collaboration as progressing through interrelated stages—activation, collectivity, institutionalization, stability, loss of momentum, or reorientation—while allowing for overlap, regression, or adaptation in response to contextual pressures. This adaptive orientation is consistent with views of innovation as an emergent process requiring continual alignment between structural arrangements and relational practices [13,16] and aligns well with living labs, which often operate under dynamic conditions, political transitions, and evolving actor constellations [17]

In this study, the governance lifecycle perspective was used to examine how the living lab Enrekang advanced during its early phases, what institutional conditions became necessary as collaboration matured, and why the initiative later entered a period of stagnation. This lens makes it possible to locate the decline in activity within a broader adaptive cycle of collaborative governance and identify governance-related challenges that hinder the transition from experimentation to more stable institutional arrangements.

2.2. Social Capital Theory

Social capital provides a relational lens for understanding how collaborative action is initiated, maintained, and disrupted within multi-actor innovation settings. Drawing on the conception of social capital as networks, trust, and shared norms that enable coordinated action [12], the approach is particularly relevant in rural contexts where informal relationships shape how knowledge is exchanged and how commitments are upheld. Conceptual work on innovation systems further emphasizes that collaboration depends on relational qualities—such as trust, reciprocity, and shared commitment—that allow actors to navigate uncertainty and adapt to evolving circumstances [13,16,18].

In this study, social capital is not used to classify network structures, but to illuminate how relational qualities—trust, mutual commitment, and expectations of follow-up—supported early collaboration in the living lab Enrekang and how these qualities shifted as coordination weakened. This perspective supports a search for understanding how an initiative built on strong ethical commitment encountered difficulties in sustaining momentum, and how shifting relational dynamics intertwined with governance challenges across its lifecycle.

2.3. Integrating Framework

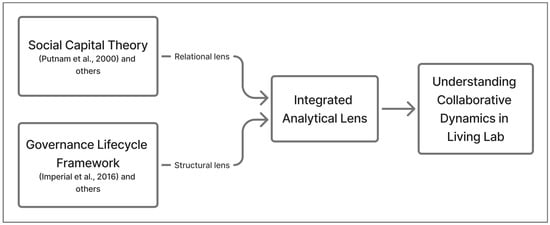

While the previous sections outlined the structural and relational perspectives used in this study, this subsection brings them together to show how they jointly inform the analytical approach. Integrating these perspectives makes it possible to examine not only the organizational processes shaping collaboration but also the relational dynamics that condition how actors engage with and sustain joint work. Figure 1 illustrates the integrated analytical framework used in this study, combining the governance-of-innovation lifecycle with a social capital perspective to examine collaborative dynamics in the living lab Enrekang.

Figure 1.

Integrated Framework for Understanding Collaborative Dynamics in the Living Lab Enrekang. Source: Authors’ Elaboration based on [11,12].

Figure 1 illustrates how the two perspectives jointly shape the analytical lens of the study. The governance lifecycle provides a structural view of how collaboration develops, stabilizes, or weakens as institutional conditions change, while social capital theory highlights how relational elements such as trust and shared expectations support or constrain joint work across actors. Together, these perspectives capture the interplay between institutional arrangements and relational processes, enabling a more comprehensive understanding of how collaborative dynamics unfolded in the living lab Enrekang.

Recent work on transdisciplinary collaboration highlights that multi-actor innovation evolves within socially complex environments, where coordination depends not only on formal structures but also on the relational and affective practices that sustain joint work. This reinforces the value of combining a governance lifecycle lens with relational social capital perspective, as it acknowledges that collaborative platforms—such as living labs—are adaptive and vulnerable when institutional routines and interpersonal expectations fall out of sync [19].

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Research Design

This study employed a qualitative case study design to explore how stagnation emerged within the living lab Enrekang and how this slowdown influenced communication, relationships, and expectations among participating actors. A case study approach was selected because it enables an in-depth examination of complex, context-dependent processes and is well-suited to understanding how collaborative initiatives unfold within real institutional environments [19]. The living lab Enrekang, established in 2019 in South Sulawesi, Indonesia, provides an appropriate setting for such inquiry, as it originated from cross-institutional collaboration to co-design and develop the DFFS and later experienced a period of reduced momentum. This design allowed the study to capture diverse perspectives from farmers, extension officers, DFFS design teams, university partners, and government actors directly involved or affected by the initiative.

3.2. Data Collection Methods

Data were collected between December 2024 and August 2025 using complementary qualitative methods. The study began with an initial document review that reconstructed the development of the living lab and the DFFS prior to the stagnation period. The materials reviewed included meeting minutes, workshop reports, design documents, and activity reports from 2018 to 2023. These documents provided historical context, clarified key events and decisions, and helped trace coordination patterns and institutional arrangements that were not fully captured through interviews alone.

Two focus group discussions were then conducted: one with a farmer group (10 participants, in person) and one with extension officers (six participants, online). These discussions explored the perceived relevance of the DFFS, participants’ continued interest in re-engaging, and expectations for future implementation. In addition, 16 semi-structured interviews were carried out with government officials, members of the DFFS design team, and extension officers to examine governance challenges, leadership transitions, coordination processes, institutional support, budgeting constraints, and proposed strategies for revitalizing the initiative. All sessions were conducted in Bahasa Indonesia, with detailed field notes taken during discussions and later expanded into full written accounts for analysis. The first and fourth authors were embedded in the initiative in facilitative and observational roles, enabling prolonged engagement and contextual understanding.

A second round of document review was conducted to complement and triangulate the qualitative data. Integrating document reviews with FGDs, interviews, and participant observations strengthened the triangulation process and provided a more comprehensive understanding of both the initiative’s early progress and the factors contributing to its slowdown. This multi-source approach aligns with qualitative case study standards and supports the credibility of the analysis. An overview of the data sources, stakeholder participation, and methods is provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Data Sources and Stakeholder Participation, Including Archival Materials.

3.3. Data Analysis

The data were analyzed using an iterative thematic analysis approach. The process began with repeated readings of the expanded field notes from interviews, FGDs, participant observations, and archival materials generated during document review. Initial descriptive codes were developed to capture recurring ideas related to collaboration, communication, coordination practices, leadership continuity, and the evolving dynamics of the living lab Enrekang.

In the subsequent analytic activity, these descriptive codes were grouped according to the key stages of governance of the innovation lifecycle: activation, collectivity, institutionalization, and stagnation. This grouping enabled the analysis to trace how the collaborative process shifted across different points in the development of the living laboratory. A parallel coding stream focuses on the relational elements associated with social capital, including trust, shared norms, expectations of follow-up, and cross-sector relationships. These relational codes highlight the interpersonal and normative conditions that emerged within each component of the innovation lifecycle.

To enhance analytical robustness, codes were compared across stakeholder groups (farmers, extension officers, government officials, and design team members) in order to distinguish shared patterns from group-specific interpretations. The quotations used in Section 4 (Results) were selected because they represented themes that appeared repeatedly across the dataset, rather than isolated viewpoints. Alternative interpretations were examined by cross-checking interviews and FGD insights with observational notes and archival materials, which helped refine and validate the thematic categories.

In the final round of analysis, structural codes (linked to lifecycle phases) and relational codes (linked to social capital) were integrated to develop overarching themes representing the interaction between governance dynamics and relational conditions. This analytical process enabled a nuanced examination of how stagnation emerged, how it related to shifts in communication and expectations among actors, and the relational and organizational conditions that may be required to sustain collaborative rural communication initiatives.

4. Results

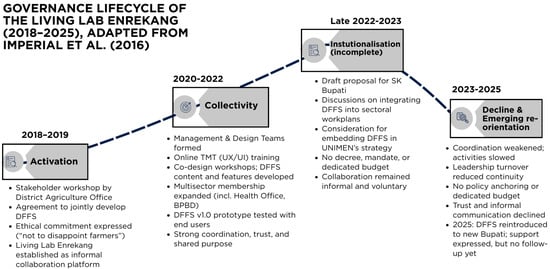

In line with Imperial’s governance-of-innovation framework, the results are organized around the key stages of the governance lifecycle—activation, collectivity, attempted institutionalization, and stagnation—to illustrate how the collaborative process within the living lab Enrekang evolved over time. Across each stage, both structural (governance) dynamics and relational (social capital) conditions were highlighted to demonstrate how collaboration develops and bottlenecks emerge. To provide an overview of these shifts, Figure 2 presents a timeline summarizing the major phases of Enrekang’s development from 2018 to 2025.

Figure 2.

Governance lifecycle Timeline of the Living Lab Enrekang (2018–2025). Adapted from [11]. Source: Authors’ elaboration.

4.1. Activation Stage (2018–2019): Building Initial Commitment

The activation stage began in 2018 when the Enrekang District Government invited Van Hall Larenstein (VHL) and Universitas Muhammadiyah Enrekang (UNIMEN) to share their experiences with Digital Farmer Field School (DFFS) development during a stakeholder coordination workshop organized by the District Agriculture Office (DAO). The workshop introduced staff from DAO and related institutions to innovative, interdisciplinary strategies for rural communication, exposing them in an interactive manner to the potential of the DFFS as a digital learning tool that could strengthen farmers’ access to timely and locally relevant knowledge for improving good agricultural practices and enhancing long-term resilience. These exchanges generated strong interest among participating agencies. Representatives from the District Agriculture Office (DAO), District Livestock and Fisheries Office (DLFO), and District Environment Office (DEO) recognized that further development of the DFFS would require coordinated contributions across multiple sectors.

As discussions continued, actors increasingly perceived the workshop as conducive to recognize and to articulate that fragmented, sector-bound practices were not sufficient to support coordinated rural communication efforts. In response, they opted to establish the living lab Enrekang in 2019 as an informal collaborative space to strengthen cross-sector interaction. Within this platform, institutions, universities, extension officers, and farmers were able to work more iteratively and responsively, which led to the joint initiation and co-design of the DFFS as a digital, multi-sector learning tool.

A pivotal feature of this early stage was the emergence of a shared ethical commitment, documented in design workshop notes and expressed through the commonly articulated principle, “We do not want to disappoint farmers.” This value became a relational anchor that shaped the expectations of follow-up, integrity, and responsiveness throughout the co-design process. The relational conditions were strong: cross-sector interaction occurred frequently; actors demonstrated a high willingness to share expertise and resources; and farmer groups, particularly those in the Baroko subdistrict, actively contributed to the initial assessment and viewed the living lab as an inclusive platform through which their agricultural information needs could be voiced and addressed. This collective ethic fostered a shared sense of responsibility toward farmers, reinforcing interpersonal trust and laying the social capital foundation that enabled early collaboration to advance smoothly into more structured joint work.

4.2. Collectivity Stage: Collaborative Design and Prototype Development

Building on the shared motivation and relational energy formed during the activation stage, the living lab Enrekang transitioned into a more structured phase of collaboration between 2020 and 2022. This collectivity phase marked a shift from exploratory discussions to routine co-design activities, strengthened coordination, and broader multi-sector involvement to support the development of DFFS.

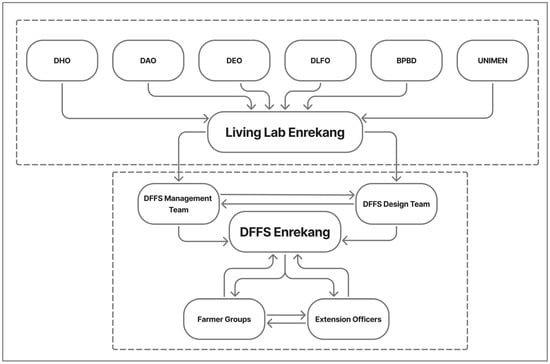

To organize this work, partner institutions established two operational groups: a Management Team, comprising institutional representatives responsible for strategic direction, and a Design Team, consisting of technical staff tasked with platform development, interface refinement, and engagement with farmers and extension officers. Although these arrangements were not formalized through policy or organizational mandates, they helped strengthen communication channels and establish more predictable working routines across institutions. The overall structures of these coordinating groups and their roles in the laboratory are shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Governance Structure of the Living Lab Enrekang and Its Relationship to the DFFS Initiative. Source: authors’ elaboration.

A central activity during this stage was the Tailor-Made Training (TMT) program on DFFS co-design, funded by Nuffic Neso and delivered by VHL in collaboration with UNIMEN. Conducted entirely online due to COVID-19 restrictions, the training focused on user experience (UX) and user interface (UI) design and provided experiential learning for the Design Team. While the online format limited opportunities for in-person facilitation, the pandemic highlighted the critical need for alternative rural communication channels when face-to-face activities are disrupted. This context reinforced the actors’ motivation to advance DFFS as a flexible and resilient learning tool.

During this period, living labs’ membership expanded in response to emerging farmers’ information needs. The District Health Office (DHO) joined to provide expertise on COVID-19 prevention and the health risks associated with intensive pesticide use, while the District Disaster Management Agency (BPBD) later joined as forest fires, flash floods, and landslides increasingly threatened agricultural livelihoods. These additional actors broadened the knowledge base available for co-design and strengthened the relevance of a multi-sector approach to developing rural learning innovations. Reflecting this trend, the BPBD staff described their participation as a response to escalating environmental risks affecting farming communities. As one official noted, “Our data show rising environmental risks—forest fires, flash floods, and landslides. We felt it was necessary to work with other sectors to increase community awareness, for example by promoting good farming practices to help prevent further environmental degradation.” (BPBD official, reflection documented in the DFFS back-office simulation report).

Co-design activities were intensive and closely intertwined with the training process. Through a series of workshops, online learning sessions, and field-based activities, participants jointly identified priority content areas, shaped core platform features, and refined interface elements to ensure usability for diverse farmer groups. These interactions foster predictable communication patterns, strengthen trust across institutions, and deepen mutual understanding of each actor’s role in supporting farmer learning.

These collaborative processes culminated in the development of functional DFFS v1.0 prototype. Prototype testing conducted in 2022 assessed navigational usability, relevance of content elements, and farmers’ expectations for future iterations. The testing also offered structured opportunities for farmers, particularly from the Baroko sub-district, to articulate the types of information that they considered most valuable for inclusion in the next version of the platform.

By the end of 2022, design routines were well established, multi-sector coordination was strong, and stakeholder expectations for continued progress were high. Farmers and extension officers expressed readiness to participate in further iterations, reinforcing the relational momentum built during this stage.

4.3. Institutionalization Stage (Late 2022–2023): Formalization Attempts Without Follow-Through

The transition from the collectivity stage to institutionalization required clearer mandates, formal coordination mechanisms, and stable resource arrangements to sustain momentum. In 2022, several proposals emerged that signalled the intention to move in this direction. Members of the Management Team suggested issuing a district-level decree (SK Bupati) to formalize the DFFS as a strategy for rural communication, provide legal standing for cross-sector engagement in the living lab, and enable the living lab and DFFS to be integrated into the district planning and budgeting processes. Extension officers also recommended that DFFS-related tasks be recognized within official performance indicators to reflect the changing nature of extension work.

Similarly, university partners explored the possibility of anchoring the initiative within UNIMEN’s strategic plan and research roadmap, which would provide an institutional home independent of political transitions. These ideas reflect a growing awareness among actors that sustained collaboration requires more than informal coordination or shared motivation.

However, these institutionalization efforts remained fragmented and did not move beyond informal agreements. No district decree was issued, formal integration into departmental work plans did not occur, and dedicated budget mechanisms were not established. Several Management Team members noted that the proposal for formal anchoring had progressed but was disrupted by administrative transitions. One member recalled:

“Discussions about drafting an SK Bupati began in early 2023, initially coordinated by the Regional Development Planning Agency (Bappeda). However, when the responsible official was reassigned, the process did not continue, and no subsequent unit took over the follow-up.”(DFFS Management Team, Interview 2025).

The absence of follow-up meant that the initiative continued to rely on informal arrangements, voluntary participation, and relational energy developed during the earlier phases. Consequently, the living laboratory entered the next stage without the institutional foundations needed to maintain continuity, making it highly vulnerable to leadership changes, staff turnover, and shifting priorities. This incomplete transition to institutionalization sets the conditions through which the stagnation phase emerges, as discussed in the next section.

4.4. Stagnation Stage (2023–2025): Declining Coordination and Momentum

Following the strong relational momentum built during the collectivity stage, collaboration entered a period of slowed activity, beginning in 2023. Although commitment to DFFS remained high among extension officers, farmer groups, and design team members, institutional follow-up activities did not progress. Coordination meetings became infrequent, communication across sectors weakened, and previously planned platform iterative sessions were left on hold. The absence of structured follow-up gradually undermined the shared expectation of continuity that had been cultivated in earlier phases.

Another factor shaping this slowdown was the novelty of both the DFFS concept and the living lab approach for institutional actors. DFFS introduced a form of real innovation that required new ways of working and thinking. Combining multi-sector knowledge, digital content development, and iterative user engagement, while institutional experience with rural communication platforms of this kind remained limited presented a serious challenge to staff involved. This unfamiliarity created uncertainty about how the initiative could be anchored within existing organizational structures. An early attempt to connect the DFFS with the national e-extension strategy illustrates this challenge. Although initial interest was signalled at the national level, the effort did not progress, reflecting the complexity of innovation and the absence of established pathways for integrating such platforms into formal extension systems.

The transition in political and institutional leadership is considered by many living lab and DFFS stakeholders to be a central factor contributing to the slowdown. The district head (Bupati) who had endorsed the living lab and provided strong political legitimacy completed his term in 2023. His successor, serving in an interim capacity, shifted attention toward administrative preparations for the upcoming elections. By early 2025, the newly elected Bupati had not yet been introduced to the living lab or the DFFS, as living lab members had not succeeded in bringing the initiative to his attention, contributing to continued uncertainty about future institutional support.

Changes in political and administrative leadership also occurred within the participating agencies. Several technical staff members who contributed to earlier co-design activities were reassigned to new roles, often without any formal induction for their replacements. As a result, practical knowledge of design decisions, coordination routines, and earlier agreements remained with individuals, rather than being transferred institutionally. This erosion of institutional memory weakened the initiative’s technical capacity and made it difficult to maintain continuity as the living laboratory attempted to move forward. This pattern was reflected in several accounts, including one that shared the following:

“Although I have been reassigned to a different post, I can only continue supporting the DFFS if my new supervisor approves my involvement. He has not been exposed to the initiative yet.”(Design Team Member, 2024)

Despite this willingness, personnel reassignment created a discontinuity in expertise and reduced the frequency of interdepartmental communication, two conditions that had previously supported collective action. Many staff members emphasized the need for formal policy anchoring to mitigate these vulnerabilities. As noted by a Management Team member,

“If the living lab had been formalised and had a legal basis, we could have continued even with leadership and staff changes. We proposed this before, but it was never realised, and eventually everything stalled.”(Management Team Member, 2024)

These governance challenges are compounded by resource-allocation constraints. With no dedicated budget line for DFFS and no district decree (SK Bupati) to legitimize its work, the participating agencies were unable to formally allocate funds or staff time. A government official clearly described the situation.

“Each department has its own budget, but none can be allocated to DFFS because it is not formally registered.”(District Official, 2024)

“Because DFFS is still in the experimentation stage, it is difficult for us to include it in the district budget. I propose that it be supported first through university research grants. When it is more established, then we can consider government funding”(District Official, 2025).

As these institutional uncertainties accumulated, the relational dynamics within the living lab network began to shift. The year 2024 coincided with an intensive national and local electoral cycle during which public agencies focused heavily on election administration and political transitions. This broader electoral climate, characterized by heightened political activity, shifting administrative priorities, and organizational repositioning, affected working relationships across institutions.

Field observations provide evidence that the 2024 election period subtly reshaped interpersonal relations among staff members. While political preference differences are a routine feature of democratic environments, during this period, they affected staff interactions in ways that reduced the comfort of coordination and diminished the frequency of informal exchanges. These shifts introduced a degree of interpersonal distance and hesitation, which in turn weakened the existing trust among partners. As captured in the field notes, this combination of reduced cohesiveness, strained trust, and lower informal communication contributed to the erosion of bonding social capital during stagnation.

Despite these challenges, farmers consistently voiced anticipation of the next DFFS iteration. Farmer groups indicated confidence that the newly elected leadership would eventually continue the initiative, as it aligned closely with farmers’ needs and district agricultural priorities.

“We believe the new government will continue DFFS because it is for the benefit of farmers.”(Farmer Group Representative, 2025).

Similarly, DFFS team members recognized the need to reintroduce the initiative to new leaders to ensure alignment with current development priorities.

“We need to explain DFFS again to the new administration so they understand how it supports their priorities.”(DFFS Design Team Member, 2025).

Together, these dynamics illustrate how the evolving conditions in Enrekang did not stem from a lack of motivation at the user or field level, but rather from a misalignment between relational expectations and institutional conditions. As the governance lifecycle framework suggests, early enthusiasm cannot transition to a stable practice without adequate leadership continuity, formal anchoring, or resource allocation. Concurrently, the relational foundations that sustained early collaboration—trust, shared norms, and cross-sector cohesion—were weakened by political transitions, staff rotations, and reduced cross-sector interactions. These combined factors produced a period of stagnation in which collective intentions remained strong but the enabling conditions for collaboration diminished. This sentiment was echoed across the Design Team, which expressed concern that stalled follow-ups risked undermining earlier commitments to farmers. As several team members explained,

“It would be regrettable if the DFFS initiative is not continued, because it has strong potential to reduce information gaps for farmers. The collaborative platform we created—where different actors could work and learn together—should not have to dissolve. We hope the next administration will be able to continue this work.”(Design Team Interviews, 2025).

These patterns of relational change are summarized in Table 2, which maps the evolution and erosion of core social capital dimensions across the three stages of the lifecycle of a living lab.

Table 2.

Changes in Relational Dimensions of Social Capital Across the Lifecycle of the Living Lab Enrekang. Source: Authors’ Elaboration.

Overall, the findings indicate that the trajectory of the living lab Enrekang arose from the interplay of multiple governance and relational factors, rather than any single cause. Early progress, supported by trust, shared commitment, and frequent interaction, could not compensate for the absence of formal anchoring, leadership continuity, induction mechanisms, and resource pathways as the initiative moved toward more institutionalized practice. As structural demands increased, coordination weakened, follow-up stalled, and uncertainty grew, despite sustained motivation among frontline actors.

This synthesis highlights that understanding living lab dynamics requires attention to the evolution of governance arrangements and relational conditions over time. The combined use of the governance lifecycle and social capital perspectives was central to understanding these developments, clarifying why early enthusiasm did not translate into institutional embedding. These patterns resonate with studies noting similar difficulties in living laboratories operating in decentralized or resource-constrained settings [5,6,9,20,21]. The following discussion builds on this insight by situating the Enrekang case within broader debates on collaborative innovation and examining the conditions required to sustain momentum beyond early design and experimentation.

5. Discussion

The findings provide a detailed view of how the living lab Enrekang evolved across its activation, collectivity, institutionalization, and stagnation phases, offering new empirical insights into processes that remain under-examined in living lab scholarship. While previous studies have noted that living labs often struggle to sustain momentum beyond early experimentation, they rarely document how stagnation unfolds in practice or how it reshapes communication, interaction patterns, and relational expectations—gaps that are particularly salient in rural contexts where informal relationships play a central role in sustaining cooperation [22,23]. By tracing the interplay between governance arrangements, political transitions, staff turnover, resource constraints, and shifting relational dynamics, this study shows that stagnation emerges not from a single failure but through a gradual misalignment between governance demands and the relational infrastructure that supported early collaboration [24]. These findings advance the understanding of how institutional and relational factors interact to shape stagnation, a dimension that is still undertheorized in the existing literature.

5.1. How Stagnation Unfolds Across the Innovation Lifecycle

This study addresses a key gap in living lab scholarship: the limited empirical insight into how slowdown unfolds and how it reshapes communication, interaction patterns, and relational expectations among actors [23], particularly in rural contexts where informal relationships are essential for sustaining cooperation. The results show that the loss of forward progress in the living lab Enrekang was not a sudden break but a gradual process shaped by the interplay between emerging governance demands and shifting relational conditions. These results extend living lab governance theory by offering empirical insight into how a loss of momentum emerges through the interaction of institutional and relational factors across innovation phases.

During activation and collectivity, informal governance, trust-based coordination, and strong relational commitment enabled swift collective action, iterative design, and multi-sector learning [25]. These dynamic mirror patterns have been observed in early innovation phases elsewhere, where flexible collaboration and relational energy support experimentation [11,22,26]. However, as the initiative moved into the institutionalization phase, the absence of a formal governance framework, such as a district decree, defined mandates, or integration into official planning, created a widening gap between project needs and institutional support. Comparative studies show that living labs frequently lose momentum when structural embedding does not evolve in parallel with the innovation milestones [27,28,29].

The Enrekang trajectory reinforces this pattern: while the platform advanced from ideation (2018–2019) through co-design (2020–2021) and prototype testing (2022), the lack of institutionalization resulted in a prolonged “trial” stage. As previous research has argued, effective living labs require governance arrangements that adapt over time, shifting from informality and experimentation to more formalized coordination, resource pathways, and political legitimacy [21,30]. Without this evolution, relational strengths alone cannot sustain the initiative once structural pressure increases.

Although farmers were engaged early in the scoping stage, particularly through user profiling and story development, prototype testing deepened their involvement by generating feedback regarding usability, navigation, and content relevance. While limited co-design was not a factor in stagnation in this case, the literature on living laboratories and participatory digital innovation emphasizes the importance of sustained user engagement across iterative cycles [31,32] to maintain alignment and strengthen adoption pathways [4,6,26,33,34].

Further insights concern the DFFS as a complex rural innovation. The DFFS introduced new competencies and routines that were not yet established within local extension systems, and the initial online training—focused primarily on design and content development—did not provide a sufficient foundation for systemic institutional embedding. Embedding the DFFS would have required positioning it not only as a digital interface but as a rural communication service that depends on institutional governance structures—an area that overlaps with, yet is distinct from, the living lab as the collaborative platform. Rural innovation studies note that organizations often struggle to advance novel initiatives when absorptive capacity is limited or when no procedural pathways exist for integrating experimental tools into formal systems [35,36,37]. The stalled attempt to link the DFFS with the national e-extension system reflects this broader structural issue: the issue lay not in lack of interest, but in the absence of institutional mechanisms capable of absorbing and supporting complex innovation. Thus, the DFFS introduced an additional layer of governance challenges that interacted with leadership transitions and resource gaps to shape stagnation.

5.2. Governance Vulnerabilities

The findings show that leadership transitions, both political and bureaucratic, are central drivers of stagnation. The departure of the district head, who championed the initiative, removed a key political advocate [38], while subsequent leaders were not adequately briefed. Within agencies, staff involved in co-design were reassigned, and no onboarding mechanisms existed for replacement, accelerating the loss of institutional memory. These patterns reflect the vulnerabilities identified in the governance of the innovation lifecycle framework, which describes the institutionalization phase as particularly fragile, without clear mandates and political embedding [11]. The international literature notes that leadership discontinuity in living labs often disrupts coordination routines [39], weakens co-creation processes, and contributes to declining engagement [33,40].

In Enrekang, early agreements relied heavily on personal commitment rather than institutional mandates, making them vulnerable to political transition. Research shows that interpersonal relationships cannot compensate for missing institutional anchors during political change [41]. Research on multi-actor rural innovation systems emphasizes that hybrid governance combining formal anchoring with flexible coordination is essential to buffer collaborative initiatives from political cycles [28,42]. Urban living lab studies also highlight that the continuous reaffirmation of agreements and resilient governance mechanisms helps mitigate leadership turnover risks [43,44]. The Enrekang case amplifies these points: without legal anchoring, formal roles, or onboarding, the initiative remained exposed to leadership change despite grassroots support [45].

5.3. Shifts in Stakeholder Engagement and Interaction Patterns During Stagnation

The stagnation phase altered not only governance structures, but also communication and interaction patterns that sustained the initiative. In the early phases, cross-sector coordination, shared ethical commitments, and predictable communication routines enabled the co-design and strengthened collective ownership. This aligns with earlier research showing that trust, shared vision, and relational density [23,24] are critical for the activation and collectivity of living laboratories [21,46].

These patterns changed as leadership shifts and staff rotation increased [38,45]. Coordination meetings became sporadic, informal communication weakened, and interaction across agencies diminished. The initiative’s purpose became increasingly fragmented, as perceived by some as a digital training tool rather than a collaborative governance platform. Such divergence mirrors the “paradoxical tension” described in earlier studies [47], where instability causes stakeholders to revert from innovation-as-process (collaboration) to innovation-as-product (technology) [17,30,47].

The Enrekang case demonstrates how stagnation reshapes relational expectations, an underexplored gap in the current literature. The shared norm of “not disappointing farmers” was still valued, but stakeholders felt increasingly unable to meet expectations for follow-up, responsiveness, and continuity. Research on rural innovation systems suggests that stakeholders remain engaged when facilitation roles are stable, strategic coordination persists, and communication channels are maintained actively [28,42]. These findings also resonate with evidence of “participation fatigue” and declining engagement when living labs remain in prolonged trial phases without concrete institutional signals or resource commitments [9,26]. Thus, the Enrekang case offers granular empirical insight into how stagnation alters social dynamics and reduces relational cohesion, enabling collaborative learning.

5.4. Resource Dependencies and the Limits of Informal Coordination

A recurring constraint was the inability to mobilize resources because the DFFS lacked legal status and was not integrated into district plans. Although the agencies were supportive, the regulations prevented the allocation of funds or staff time without policy recognition. This mirrors the finding that limited funding pathways hinder the progression of the prototype [28,43,48]. For multi-sector innovations, such as the DFFS, integration into sector budgets alone is insufficient, and dedicated coordination mechanisms are needed.

Studies in other living lab contexts show that successful resource mobilization typically occurs when innovation initiatives are framed strategically [39,41] to align with institutional mandates and development priorities, creating legitimacy for sustained investment [21,29]. The Enrekang case demonstrates the consequences of missing this alignment. Despite strong relational foundations, the absence of structural mechanisms rendered the initiative financially vulnerable and contributed to its stagnation.

Taken together, these insights illustrate that engaging with governance-of-innovation and social capital perspectives is more than a technical exercise; it enables a deeper understanding of how collaborative rural initiatives maintain ethical commitment, navigate uncertainty, and protect continuity as they evolve. Early interactions in Enrekang revealed a strong sense of responsibility toward farmers, underscoring that innovation decisions have real consequences for those most exposed to information gaps and environmental risks. Similarly, scholarship in rural innovation systems highlights that collaborative platforms require alignment between governance arrangements and relational conditions to sustain commitment over time [14,49,50]. The Enrekang case illustrates this dynamic: as institutional uncertainty increased and cross-sector interactions weakened, the absence of facilitation routines and clear governance roles made it difficult to maintain cohesion and follow-up. These patterns reinforce the argument that collaborative capacity is highly sensitive to both structural stability and relational continuity in multi-actor environments.

Finally, the Enrekang case shows that the development of the DFFS and the living lab became deeply intertwined, making the boundaries between innovation and the platform difficult to distinguish in practice. Because both processes unfolded simultaneously (co-design, coordination, and experimentation progressing in parallel), the advancement of one directly influenced the other. When the living lab’s coordination routines weakened, the DFFS also slowed, not because of shortcomings in the innovation itself, but because its organizational anchor lost stability. This pattern aligns with research showing that multi-actor innovation processes often evolve through overlapping institutional, technical, and relational dynamics, which are difficult to separate analytically [36,37]. Recognizing this interdependence offers an important lesson for rural innovation initiatives: experimental tools and collaborative platforms that support them must be strengthened to maintain learning, alignment, and continuity through institutional transitions.

6. Conclusions

This study examined how the governance arrangements of living lab Enrekang shaped the development and evolving conditions of the DFFS initiative. By analyzing the initiative across its key stages, the study addressed its core objective: understanding how stagnation emerged and how it reshaped communication, coordination, and relational expectations within a rural multi-actor collaboration. The results show that early progress was driven by strong trust, shared norms, and active cross-sector engagement. However, the absence of policy anchoring, leadership continuity, and stable resource mechanisms left the initiative vulnerable once more formal support became necessary. As leadership turnover, staff rotation, and shifting political priorities accumulated, interaction frequency declined, and cross-sector cohesion weakened, contributing to a gradual weakening of collaborative dynamics despite continued motivation among farmers and frontline actors.

Taken together, these findings underscore the interdependence of structural governance conditions and relational processes in long-term collaborative initiatives. Sustaining momentum requires more than early collective energy; it also demands deliberate efforts to institutionalize roles, secure resourcing pathways, and reinforce coordination routines, especially during administrative transitions. The analysis further highlights that the novelty and complexity of DFFS created additional challenges for institutions with limited absorptive capacity, illustrating how unfamiliar innovations can amplify governance vulnerabilities in rural settings.

A notable limitation of this study is the analytical difficulty in separating the development of the DFFS from the evolution of the living lab, as both progressed in parallel and were closely intertwined in practice. Future research could examine this interdependence more directly, to better understand how collaborative platforms and their experimental innovations co-evolve.

This study’s contributions are twofold. Empirically, it provides rare documentation of how a living lab and its experimental innovation can evolve in an overlapping manner, shaping each other’s trajectory in rural decentralized contexts. Theoretically, it advances the understanding of living lab dynamics by integrating the governance lifecycle perspective with the social capital theory to explain why early enthusiasm did not translate into sustained institutional practice. These insights offer a practical tool for anticipating governance vulnerabilities before they crystallize into prolonged stagnation, and a conceptual foundation for examining the durability of collaborative innovation platforms.

The experience of the living lab Enrekang ultimately illustrates a central paradox of collaborative rural innovation: shared purpose and early enthusiasm can mobilize actors and generate promising beginnings, yet without institutional anchoring and mechanisms that safeguard continuity, even the most compelling initiatives may struggle to progress beyond early experimentation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, all authors; methodology, N.L., D.S. and L.W.; investigation, N.L., L.W. and D.S.; software, N.L.; validation, D.S., L.W. and A.A.A.; formal analysis, N.L.; writing—original draft preparation, N.L.; writing—review and editing, all authors.; visualization, N.L.; supervision, D.S., L.W. and A.A.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study did not receive external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by Institutional Review Board of the Graduate School of Hasanuddin University (approval code: 08973/UN4.1.27.1/PT.01/2025, approval date: 20 August 2025).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to ethical restrictions and the need to protect the confidentiality of interview and focus group participants.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the farmer groups, extension officers, and local government staff in Enrekang District who generously shared their time, experiences, and insights during the study. Their participation and openness were essential to the development of this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| Bappeda | Indonesian Badan Perencanaan Pembangunan Daerah/Regional Development Planning Agency |

| BPBD | Indonesian Badan Penanggulangan Bencana Daerah/Regional Disaster Management Agency |

| Bupati | Indonesian term for Head of District |

| DFFS | Digital Farmer Field School |

| DAO | District Agriculture Office of Enrekang |

| DEO | District Environmental Office of Enrekang |

| DHO | District Health Office of Enrekang |

| DLFO | District Livestock and Fisheries Office of Enrekang |

| LLs | Living Labs |

| NUFFIC | Netherlands Organization for International Cooperation in Higher Education |

| NESO | Netherlands Education Support Office |

| SK | Surat Keputusan/Decree |

| TMT | Tailor-Made Training |

| UNIMEN | Universitas Muhammadiyah Enrekang/The University of Muhammadiyah Enrekang |

References

- Manyise, T.; Dentoni, D. Value chain partnerships and farmer entrepreneurship as balancing ecosystem services: Implications for agri-food systems resilience. Ecosyst. Serv. 2021, 49, 101279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Bruin, S.; Dengerink, J.; Van Vliet, J. Urbanisation as driver of food system transformation and opportunities for rural livelihoods. Food Secur. 2021, 13, 781–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuurman, D.; Baccarne, B.; De Marez, L.; Veeckman, C.; Ballon, P. Living Labs as open innovation systems for knowledge exchange: Solutions for sustainable innovation development. Int. J. Bus. Innov. Res. 2016, 10, 322–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronson, K.; Devkota, R.; Nguyen, V. Moving toward generalizability? A scoping review on measuring the impact of living labs. Sustainability 2021, 13, 502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berberi, A.; Beaudoin, C.; McPhee, C.; Guay, J.; Bronson, K.; Nguyen, V.M. Enablers, barriers, and future considerations for living lab effectiveness in environmental and agricultural sustainability transitions: A review of studies evaluating living labs. Local Environ. 2023, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cascone, G.; Scuderi, A.; Guarnaccia, P.; Timpanaro, G. Promoting innovations in agriculture: Living labs in the development of rural areas. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 443, 141247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lairing, N.; Witteveen, L.; Busa, Y.; Bagenda, A.; Bagenda, M.; Addi. Co-constructing principles for Digital Farmer Field School Enrekang Design in South Sulawesi—Indonesia. E3S Web Conf. 2021, 306, 03013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lairing, N. Developing Contemporary Rural Communication Services in Indonesia. Prototype Testing of Digital Farmer Field School (DFFS). In Proceedings of the IAMCR Conference, Lyon, France, 9–13 July 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Toffolini, Q.; Capitaine, M.; Hannachi, M.; Cerf, M. Implementing agricultural living labs that renew actors’ roles within existing innovation systems: A case study in France. J. Rural Stud. 2021, 88, 157–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habiyaremye, A. Knowledge exchange and innovation co-creation in living labs projects in South Africa. Innov. Dev. 2019, 10, 207–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imperial, M.T.; Johnston, E.; Pruett-Jones, M.; Leong, K.; Thomsen, J. Sustaining the useful life of network governance: Life cycles and developmental challenges. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2016, 14, 135–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putnam, R.D. Bowling alone: The collapse and revival of American community. In Proceedings of the 2000 ACM Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work, in CSCW ’00, Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2–6 December 2000; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2000; p. 357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leeuwis, C.; Aarts, N. Rethinking Communication in Innovation Processes: Creating Space for Change in Complex Systems. J. Agric. Educ. Ext. 2011, 17, 21–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klerkx, L. Digital and virtual spaces as sites of extension and advisory services research: Social media, gaming, and digitally integrated and augmented advice. J. Agric. Educ. Ext. 2021, 27, 277–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansell, C.; Gash, A. Collaborative governance in theory and practice. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 2008, 18, 543–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klerkx, L.; van Mierlo, B.; Leeuwis, C. Evolution of systems approaches to agricultural innovation: Concepts, analysis and interventions. In Farming Systems Research into the 21st Century: The New Dynamic; Darnhofer, I., Gibbon, D., Dedieu, B., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2012; pp. 457–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuurman, D.; Leminen, S. Living Labs Past Achievements, Current Developments, and Future Trajectories. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingram, J.; Maye, D. What Are the Implications of Digitalisation for Agricultural Knowledge? Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2020, 4, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñiz, E.M.; Ludwig, D.; El-Hani, C.N. Research as a Mangrove: Emancipatory Science and the Messy Reality of Transdisciplinarity. Int. Rev. Qual. Res. 2025, 18, 237–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceseracciu, C.; Branca, G.; Deriu, R.; Roggero, P.P. Using the right words or using the words right? Re-conceptualising living labs for systemic innovation in socio-ecological systems. J. Rural Stud. 2023, 104, 103154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McPhee, C.; Bancerz, M.; Mambrini-Doudet, M.; Chrétien, F.; Huyghe, C.; Gracia-Garza, J. The defining characteristics of agroecosystem living labs. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nesbitt, H.K.; Hamilton, M.; Ulibarri, N.; Williamson, M.A. Operationalizing the social capital of collaborative environmental governance with network metrics. Environ. Res. Lett. 2024, 19, 113003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calò, F.; Teasdale, S.; Roy, M.J.; Bellazzecca, E.; Mazzei, M. Exploring Collaborative Governance Processes Involving Nonprofits. Nonprofit Volunt. Sect. Q. 2023, 53, 54–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sienkiewicz-Małyjurek, K. Social Capital and Transformational Leadership in Building the Resilience of Local Governance Networks. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, M.K. How Do Bridging and Bonding Networks Emerge in Local Economic Development Collaboration? Int. J. Public Adm. 2022, 46, 889–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witteveen, L.; Fliervoet, J.; Roosmini, D.; van Eijk, P.; Lairing, N. Reflecting on four Living Labs in the Netherlands and Indonesia: A perspective on performance, public engagement and participation. J. Sci. Commun. 2023, 22, A01. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamache, G.; Anglade, J.; Feche, R.; Barataud, F.; Mignolet, C.; Coquil, X. Can living labs offer a pathway to support local agri-food sustainability transitions? Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2020, 37, 93–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molinari, M.; Vogel, J.A.; Rolando, D.; Lundqvist, P. Using living labs to tackle innovation bottlenecks: The KTH Live-In Lab case study. Appl. Energy 2023, 338, 120877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potters, J.; Collins, K.; Schoorlemmer, H.; Stræte, E.P.; Kilis, E.; Lane, A.; Leloup, H. Living Labs as an Approach to Strengthen Agricultural Knowledge and Innovation Systems. Eurochoices 2022, 21, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalinauskaite, I.; Brankaert, R.; Lu, Y.; Bekker, T.; Brombacher, A.; Vos, S. Facing societal challenges in living labs: Towards a conceptual framework to facilitate transdisciplinary collaborations. Sustainability 2021, 13, 614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinke, J.; Ortiz-Crespo, B.; van Etten, J.; Müller, A. Participatory design of digital innovation in agricultural research-for-development: Insights from practice. Agric. Syst. 2022, 195, 103313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, B.D.; Leonard, E.; Mitchell, M.C.; Easton, J.; Shariati, N.; Mortlock, M.Y.; Schaefer, M.; Lamb, D.W. Current status of and future opportunities for digital agriculture in Australia. Crop. Pasture Sci. 2022, 74, 524–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyström, A.G.; Leminen, S.; Westerlund, M.; Kortelainen, M. Actor roles and role patterns influencing innovation in living labs. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2014, 43, 483–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burch, K.A.; Legun, K. Overcoming Barriers to Including Agricultural Workers in the Co-Design of New AgTech: Lessons from a COVID-19-Present World. Cult. Agric. Food Environ. 2021, 43, 147–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadfield, P.; Sharp, D.; Pigeon, J.; Raven, R. Governing University Living Labs for sustainability transformations: Insights from 18 international case studies. Sustain. Sci. 2025, 20, 1753–1774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herth, A.; Verburg, R.; Blok, K. The Innovation Power of Living Labs to Enable Sustainability Transitions: Challenges and Opportunities of On-Campus Initiatives. Creat. Innov. Manag. 2024, 34, 427–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolmans, S.; Galen, W.V.; Walrave, B.; Ouden, E.; Valkenburg, R.; Romme, G. A Dynamic Perspective on Collaborative Innovation for Smart City Development: The role of uncertainty, governance, and institutional logics. Organ. Stud. 2023, 44, 1577–1601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Fan, D. Can agricultural digital transformation help farmers increase income? An empirical study based on thousands of farmers in Hubei Province. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2023, 26, 14405–14431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dijck, C.; Steen, T. Hidden pressure: The effects of politicians on projects of collaborative innovation. Int. Rev. Adm. Sci. 2022, 89, 996–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zambrano-Gutiérrez, J.C.; de Macedo, L.S.V.; Picavet, M.E.B.; de Oliveira, J.A.P. Individuals in Collaborative Governance for Environmental Management. Environ. Manag. 2023, 71, 565–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, E.B.; Wegner, D.; Möllering, G. Governance of Interorganizational Projects: A Process-Based Approach Applied to a Latin American–European Case. Proj. Manag. J. 2023, 54, 219–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fauth, J.; De Moortel, K.; Schuurman, D. Living labs as orchestrators in the regional innovation ecosystem: A conceptual framework. J. Responsible Innov. 2024, 11, 2414505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradley, S.; Mahmoud, I.H.; Arlati, A. Integrated Collaborative Governance Approaches towards Urban Transformation: Experiences from the CLEVER Cities Project. Sustainability 2022, 14, 15566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.T.; Marques, P. The promise of living labs to the Quadruple Helix stakeholders: Exploring the sources of (dis)satisfaction. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2022, 30, 1124–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devine, D.; Valgarðsson, V.O. Stability and change in political trust: Evidence and implications from six panel studies. Eur. J. Politi Res. 2023, 63, 478–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zavratnik, V.; Superina, A.; Duh, E.S. Living Labs for Rural Areas: Contextualization of Living Lab Frameworks, Concepts and Practices. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leminen, S.; Defillippi, R.; Westerlund, M. Paradoxical Tensions in Living Labs. 2015. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/278899570 (accessed on 23 October 2025).

- Mahmoud, I.H.; Morello, E.; Ludlow, D.; Salvia, G. Co-creation Pathways to Inform Shared Governance of Urban Living Labs in Practice: Lessons from Three European Projects. Front. Sustain. Cities 2021, 3, 690458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imperial, M.T. Life Cycle Dynamics and Developmental Processes in Collaborative Partnerships: Examples from Four Watersheds in the U.S. Environ. Manag. 2023, 71, 601–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulibarri, N.; Imperial, M.T.; Siddiki, S.; Henderson, H. Drivers and Dynamics of Collaborative Governance in Environmental Management. Environ. Manag. 2023, 71, 495–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.