Abstract

This study explored the impact of social conformity when participants encountered unanimous responses from bots to both objective and subjective questions. Seventy-two participants from Heidelberg University participated in a simulated “Quiz Show”, answering general knowledge and opinion-based questions on economic policy. Using a within-subject design, participants first responded independently, then saw answers from three bots modeled after Asch’s classic conformity studies, which were displayed with usernames and profile pictures generated by artificial intelligence. The results showed significant conformity for both objective and subjective questions, regardless of whether the bot responses aligned with or opposed the initial beliefs of the participants. Gender differences emerged, with women showing higher conformity rates, as well as conformity in objective and subjective contexts appeared to be driven by distinct personality traits.

Keywords:

social conformity; opinion dynamics; artificial group influence; peer influence; majority influence JEL Classification:

C91; D83; D84; Z13

1. Introduction

Social conformity has been widely studied in psychology since the classic experiments of Asch [1,2,3], which showed that individuals often align with a unanimous majority even when that majority is clearly and demonstrably wrong. Subsequent work has branched into multiple directions. Some studies closely replicate the original work [4], others replace human confederates with computerized agents [5], yet others present aggregate opinion statistics rather than individual judgments [6,7]. A common feature across many designs is some form of deception, typically by implying that participants observe real human opinions when those opinions are in fact artificially generated. A related research strand investigates conformity to explicitly nonhuman agents, using algorithms transparently. Replications have employed robots [8,9] or virtual reality [10], but findings remain mixed. There is also ongoing debate about how conformity differs between objective and subjective domains; most studies examine only one of the domains, making it difficult to assess their connection, and differences in task design further complicate comparisons of conformity rates.

Understanding conformity is an urgent matter in the current social and political environment. Social media platforms can amplify social influence at scale, affecting electoral outcomes, facilitating misinformation, and fostering polarization and extremism. Prior work shows that people conform in online settings [11], including to comments and expressed sentiments [12], and that such effects can be strengthened by perceived social presence [13]. Echo chambers, where like-minded signals reinforce each other, may further increase polarization [14]. A particularly salient concern is the prevalence of automated accounts that can be used to shape perceived consensus. Estimates vary, but bots are widely believed to constitute a non-trivial share of major platforms’ user bases [15,16,17]. This concern is likely to intensify as generative AI enables increasingly fluent and human-like communication with artificial agents.

Theoretically, conformity in the objective domain is commonly understood as reflecting both informational and normative influence [18]. Conformity may also be shaped by self-presentation motives and the desire to maintain a positive self-concept [6,19]. These mechanisms need not operate identically across objective and subjective judgments, where “being correct” and “being socially aligned” may carry different incentives and costs.

In this study, we investigate social conformity in both objective and subjective cases using a design inspired by Asch, with one crucial modification, we transparently use bots and avoid any form of deception. Participants observe three bots on a computer interface, represented by AI-generated profile pictures and nicknames. The objective condition uses a general-knowledge quiz, while the subjective condition elicits attitudes toward economic policy. Beyond estimating conformity in each domain, we test whether conformity differs when the bot majority either supports the participant’s baseline stance while pushing it in a more extreme direction or opposes the participant’s stance. We also examine whether and how individual differences (e.g., confidence, gender, and personality traits) might relate to conformity across domains.

This study provides three main takeaways. First, even under full transparency that the unanimous “group” consists of bots, participants conform at non-trivial rates, indicating that normative pressure and the pull of apparent consensus can override independent judgment in a bot-mediated setting. Second, conformity emerges in both domains but appears to be driven by partly different mechanisms, in objective questions, the unanimous bot responses can plausibly function as an informational cue under uncertainty, whereas in subjective policy judgments the influence is primarily normative, with confidence still predicting reduced susceptibility to majority pressure. Third, we find no clear asymmetry between conforming to supportive (although more extreme) versus opposing bot majorities, suggesting that unanimity may matter more than stance congruence in this setting. Taken together, these results imply that minimal humanization cues (faces and nicknames) can be sufficient to generate social presence and facilitate herding toward nonhuman agents, which is highly relevant for online environments where automated accounts are increasingly common.

2. Hypotheses

- 1.

- Objective Conformity Hypothesis:We hypothesize that participants will exhibit a significant degree of conformity to bot-provided answers in the objective domain, especially in cases where their self-rated proficiency on a given topic is low. This conformity will be driven primarily by informational influences, as participants may defer to a unanimous majority (three bots) perceived to have domain knowledge, even when clearly informed that the bots are not infallible.

- 2.

- Subjective Conformity Hypothesis:We hypothesize that subjective conformity will be lower than objective conformity, as conformity in the subjective domain is motivated solely by normative social influences rather than informational cues. Since the questions do not have objectively “correct” answers, we anticipate that rational participants will have little incentive to align with the bots’ responses. However, we expect some normative pressure to conform due to the “humanization” of the bots and social influence from perceived “peers.”

- 3.

- Self-Concept and Conformity Hypothesis:We hypothesize that participants’ desire to maintain a positive self-concept will influence conformity behavior. Specifically, participants are more likely to conform to bot answers that align with their pre-existing views (even if expressed more extremely) rather than completely opposing views. We anticipate that conformity to supporting opinions will be stronger than conformity to opposing opinions, as participants seek to avoid admitting inferiority to bots or compromising their self-perception.

- 4.

- Personality Traits and Conformity Hypothesis:We hypothesize that distinct personality traits will differentially predict conformity in objective and subjective domains. Conformity in the objective domain will likely correlate with traits linked to information-seeking and uncertainty avoidance. In contrast, subjective conformity will be associated with social conformity tendencies and social acceptance motives.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Participants

The English-language experiment was conducted in person in the Heidelberg University laboratory in the summer of 2022. We recruited participants from the university subject pool. To minimize demand effects, participants were informed only that they would take part in a study involving a “Quiz Show” and received no information about bots or conformity prior to the session. For detailed information regarding participant demographics and their responses, please refer to the data in the Supplementary Materials.

The sample consisted primarily of university students. The mean age was 22.99 years (SD = 3.446), and 47.22% of participants identified as female. In terms of political self-placement, 84.72% reported leaning left, 8.33% reported being politically neutral, and 6.94% reported leaning right.

Given the recruitment channel, most participants were enrolled in social-science programmes, predominantly economics. This motivated our choice of economic-policy items for the subjective condition as the target population is expected to possess basic domain knowledge and to hold relatively stable opinions on these topics.

3.2. Study Design

We created a simulated “Quiz Show” using oTree [20] and a two-treatment between-subject design, one where the bots “support” and one where the bots “oppose” the participant’s own political beliefs. Within these treatments, we used a within-subject design to elicit conformity.

The experimental procedure had the following stages:

- 1.

- Welcome and introduction to the experiment

- 2.

- Risk attitude measure [21]

- 3.

- Quiz questions without manipulation (Control)

- 4.

- Personality Questionnaire (Big Five) [22]

- 5.

- Self-reported proficiencies in the topics included among the Quiz questions

- 6.

- Instructions clearly stating that the Quiz will be played with bots

- 7.

- Quiz questions as in Control, but in a different order and with manipulation (Treatment)

- 8.

- Participants’ opinions on the bots

- 9.

- Trust Game involving the participants and one of the bots [23]

- 10.

- Demographics

- 11.

- Results with feedback showing participants their earnings

3.2.1. Control and Treatment Structure

In both the Control and Treatment phases, participants answered items one at a time by selecting one of five response options. To reinforce the Quiz Show framing and reduce demand effect, participants had 20 s per item in the Control phase and 10 s per item in the Treatment phase. No correctness feedback was provided between phases.

3.2.2. Objective Items

The objective component consisted of 23 general-knowledge questions. Participants’ earnings mainly depended on accuracy in the Treatment part of the experiment, while the Control part was presented to them as a practice round. Bot responses for objective items were pre-specified and did not depend on the participants. For 20 items, all three bots displayed the same answer, while for the remaining three items, bot responses were not unanimous to reduce predictability and distract from the manipulation.

3.2.3. Subjective Items and Stance Manipulation

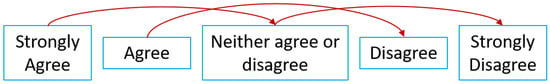

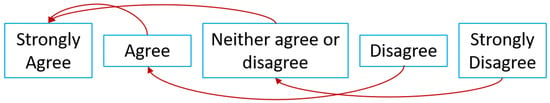

For the subjective component, we used six economic-policy items adapted from the 8values Survey [24]. Responses were given on a five-point Likert scale from “Strongly Agree” to “Strongly Disagree.” In the Treatment part, the bots’ answers were computed dynamically from each participant’s baseline response to the same item in the Control part. The manipulation consisted of a fixed two-step shift on the Likert scale. In the oppose condition, bots moved two scale points away from the participant’s baseline response toward the counter-position (e.g., Strongly Agree → Neither agree nor disagree; Agree → Disagree). In the neutral baseline case (Neither agree nor disagree), the direction of the shift was determined using the participant’s overall economic-policy leaning, so that the displayed bot majority consistently represented the counter-position. In the support condition, bots remained on the participant’s baseline side of the issue and shifted two scale points toward greater extremity (e.g., Agree → Strongly Agree; Disagree → Strongly Disagree). For all subjective items, the three bots always displayed the same response. Figure 1 and Figure 2 illustrate the resulting mappings.

Figure 1.

Bots’ oppose responses.

Figure 2.

Bot support responses.

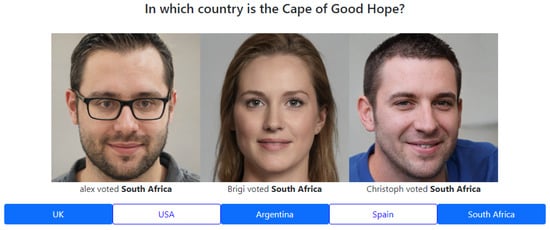

3.2.4. Bot Presentation and Humanization Cues

In the Treatment phase, participants responded after observing the three bots’ answers. Bots were explicitly labeled as bots in the instructions, but were presented with minimal humanization cues, such as AI-generated profile pictures [25] and nicknames. Participants also selected a profile picture and entered a nickname for themselves to standardize the interface and increase perceived social presence. In addition, bot responses were shown with a brief delay between agents to mimic response latency. This combination was intended to approximate how automated accounts are often presented in online environments (i.e., transparently or semi-transparently automated, yet visually and behaviorally similar to ordinary users).

Figure 3 and Figure 4 show example screens from the Treatment phase. Profile pictures and nicknames were held constant throughout the session. A countdown timer displayed the remaining time (10 s) for each item, and responses were recorded via button clicks.

Figure 3.

Objective Questions in the Treatment.

Figure 4.

Subjective Questions in the Treatment.

The above images were generated with https://this-person-does-not-exist.com/ (accessed on 14 October 2021).

3.2.5. Post-Experimental Measures

After the “Quiz Show”, we assessed how participants construed the bots (more as social partners or as machines). To avoid priming, we first asked participants to write a brief free-response description of the “others” in their group. We then implemented a Trust Game [23] between each participant and one of the bots to probe whether interaction with the bot was treated as a purely instrumental choice or as a social exchange.

3.3. Calculating Conformity Rates

For both objective questions and subjective statements, we constructed conformity rates as the extent to which a participant shifted towards (or away from) the bots’ opinions, relative to the maximum shift that was possible given that participant’s baseline responses. Because objective and subjective items differ in response structure and psychological meaning, we quantified conformity differently in the two domains.

3.3.1. Objective Conformity

Objective items were multiple-choice general-knowledge questions with verifiably correct answers (e.g., “In which country is the Cape of Good Hope?” → “South Africa”). Here, conformity is naturally captured as a discrete change: a participant conforms on an item if they switch from a non-bot option in the Control phase to the bots’ option in the Treatment phase. Items on which the participant already chose the bots’ option in the Control phase provide no opportunity to conform and are thus excluded.

We also tracked “anti-conformity” where a participant switched away from the bots’ option in the Treatment phase when they had matched it in the Control phase (i.e., a change that increases disagreement with the bots). We computed the objective conformity index () as the proportion of possible conforming switches minus the proportion of possible anti-conforming switches:

where is the number of conforming switches and is the number of items on which conformity was possible; analogously, is the number of anti-conforming switches and is the number of items on which anti-conformity was possible.

3.3.2. Subjective Conformity

Subjective items were economic-policy statements answered on a five-point Likert scale from “Strongly Agree” to “Strongly Disagree”. Unlike objective items, these responses are best interpreted as positions on an ordered scale rather than as discrete categories with a correct choice. Accordingly, we defined subjective conformity as directional movement on this scale toward the bots’ displayed position.

To quantify this consistently across items and participants, we constructed an individual-level policy score from the Control phase (denoted ) and an analogous score from the Treatment phase (). We also computed the bots’ implied score for that participant and condition () based on the deterministic mapping described in the design section. Subjective conformity () was then defined as the fraction of the participant’s maximum possible movement toward the bots:

This maps to no movement relative to baseline and to a full shift to the bots’ position. Values above 1 would correspond to “overshooting” the bots, and negative values (i.e., moving away from the bots) is considered anti-conformity. The sign of the denominator is determined by the participant-specific bot stance (support vs. oppose) and the direction of the bot shift, the absolute values ensures comparability across these cases.

3.3.3. Aggregation Level

We therefore treat conformity as an individual-level behavioural tendency across the full set of items rather than as an item-by-item binary outcome. While the objective and subjective indices are not directly identical in interpretation, both capture movement toward a unanimous bot majority relative to what was possible given baseline responses, allowing us to compare the relative strength of conformity across domains.

4. Results

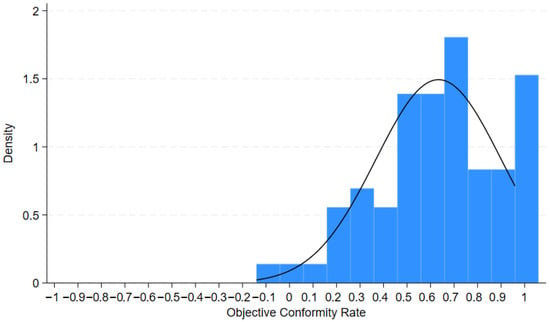

4.1. Objective Conformity

Objective conformity was measured using 23 general-knowledge questions presented twice. First in a baseline phase without social information (Control) and later in a manipulated phase in which participants observed the unanimous responses of three bots (Treatment).

As shown in Figure 5, participants exhibited substantial objective conformity. A Wilcoxon signed-rank test indicates that conformity rates were significantly greater than zero (). The mean objective conformity rate was 63.4% (SD = 0.267), which is higher than typical estimates reported in other works discussing social conformity [26]. We also find a gender difference where female participants conformed more than their male counterparts (Mann-Whitney U test, ). Consistent with an informational mechanism, participants who performed worse in the Control phase (fewer correct answers) showed higher conformity in the Treatment phase (), suggesting that uncertainty increases reliance on the unanimous bot majority. Finally, objective conformity did not differ between the support and oppose treatments, indicating that the stance manipulation in the subjective domain did not affect conformity regarding the objective items.

Figure 5.

Objective Conformity Rate.

To further probe the role of uncertainty, we elicited self-reported familiarity with several fields using a 0–100 slider scale (“How knowledgeable are you about …?”). Most objective items covered geography and history, while linguistics and politics served primarily as comparison domains. Table 1 relates these familiarity ratings to objective conformity. As expected, greater (self-reported) familiarity with quiz-relevant domains (history and geography) is associated with lower conformity. By contrast, familiarity with non-quiz domains does not show the same pattern; in particular, the positive association with politics is unexpected and may reflect unobserved individual differences (e.g., general confidence or response style) rather than task-specific knowledge.

Table 1.

Self-reported familiarity with topics.

4.2. Subjective Conformity

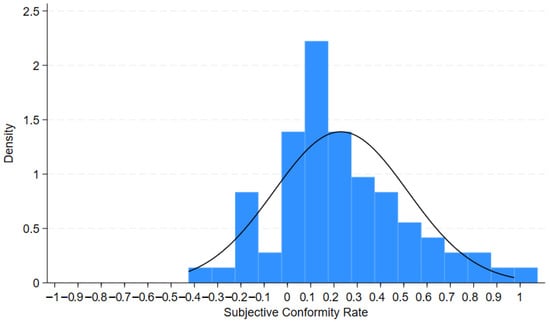

Subjective conformity was measured using six economic-policy statements adapted from the 8values survey [24]. Items were presented first without social information (Control) and then re-presented with the unanimous responses of three bots (Treatment).

Figure 6 shows that participants shifted their judgments in the direction of the bot majority. A Wilcoxon signed-rank test indicates that subjective conformity rates were significantly greater than zero (). The mean subjective conformity rate was 22.9% (SD = 0.287). We also observe a gender difference: female participants exhibited higher subjective conformity than male participants (Mann-Whitney U test, ).

Figure 6.

Subjective Conformity Rate.

Participants who answered fewer objective questions correctly in the Control phase showed higher subjective conformity (). By contrast, self-reported proficiency in the relevant topic domains did not significantly predict subjective conformity.

Finally, subjective and objective conformity were positively related (). However, we find no statistically significant difference in subjective conformity between the support and oppose treatments.

4.3. Factors Driving Conformity

Between the Control and Treatment phases, participants completed a short Big Five questionnaire [22]. Prior work relates Big Five traits to conformity [6], but typically does not distinguish between predictors of objective versus subjective conformity.

Table 2 reports OLS regressions of objective and subjective conformity on the Big Five traits, controlling for political self-placement. Objective conformity is positively associated with Conscientiousness (, ). For subjective conformity, Openness is positively associated with conformity (, ). Other traits show no statistically significant associations at conventional levels, but Neuroticism closely approaches it. The coefficient on political self-placement is negative in the subjective case, but does not reach conventional significance, and should therefore be interpreted cautiously given the sample’s political homogeneity.

Table 2.

Effect of Big Five traits on Conformity.

We also elicited the participants’ risk attitude [21] and found that the more risk-averse they are, the more likely they are to conform in the subjective case (p = 0.051).

4.4. Opinion on Bots

A central feature of our design is that the social-information source is transparently nonhuman. It is therefore important to assess whether participants understood and remembered the instruction that the “others” were bots and to probe whether the minimal humanization cues (profile pictures, nicknames, response latency) nonetheless elicited social perceptions that could support majority influence.

4.4.1. Open-Ended Descriptions

At the end of the experiment, participants answered an open-ended question about the “others” they had been playing with. We did not reiterate at this point that the others were bots, because our aim was to capture what was salient to participants when reflecting on the interaction. In these responses, the majority of participants (90.28%) did not explicitly refer to their partners as bots. Several participants expressed uncertainty about whether the others were bots, while others described the bots in overtly social terms (e.g., attributing personality traits, intelligence, or political positions). Some participants also responded as if addressing a group of peers (e.g., informal remarks about answers). Taken together, these qualitative patterns suggest that the bot identity label was often not foregrounded in participants’ spontaneous descriptions after the task, consistent with the idea that minimal humanization cues and an engaging interaction frame can encourage social interpretation even when nonhuman identity is clearly disclosed.

4.4.2. Trust Game Behavior

We also measured behavior toward a bot in a standard Trust Game [23]. Participants played as the trustor against one bot (Alex). Transfers were relatively high: 77.8% of participants sent five tokens or more, and 31.9% sent the maximum of ten tokens. Transfers did not differ significantly across treatments or by gender. Moreover, transfers were not significantly correlated with our risk-preference measure, suggesting that participants did not treat the Trust Game purely as a risky lottery. While trust behavior toward a bot can be motivated by multiple considerations (e.g., norms, expectations about reciprocity, or task framing), these results are consistent with the broader pattern that participants did not respond to the bots as purely artificial agents but like social actors.

5. Discussion

This study examined whether individuals conform to a unanimous majority when that majority is transparently composed of bots. The results extend classic conformity findings to a setting that is increasingly relevant, namely online environments in which automated accounts can appear as ordinary social actors through minimal humanization cues.

5.1. Generalizability and Design Limitations

A key limitation is that the sample consists of university students and is therefore not representative of the general population. If anything, this may bias our estimates downward. Social-science students are plausibly more familiar with experimental settings and more attentive to potential manipulation than the average user, and economics students in particular may hold relatively stable views on economic-policy topics. Nevertheless, substantial conformity emerged even in this comparatively “suspicious” population, which is consistent with the idea that bot-driven majority cues can exert influence even when their artificial origin is clearly disclosed.

Future research should test more heterogeneous samples, both demographically and politically, to examine how attitude strength and ideological diversity shape susceptibility to bot majorities. Methodologically, two extensions appear especially important. First, subjective judgments may require finer measurement: a five-point scale combined with a fixed two-step bot shift may compress variation and introduce ceiling effects near endpoints. Second, the present design uses deliberately simple agents and a restricted response format. Using contemporary large language models as interactive agents and allowing participants to respond in natural language could better approximate real-world bot encounters and clarify whether richer interaction strengthens or attenuates conformity.

5.2. Why Does Subjective Conformity Persist Under Transparent Bot Identity?

The presence of significant conformity in the subjective domain indicates that majority influence is not confined to tasks with verifiable correct answers. One interpretation is that, under unanimity, participants prioritize belonging to the group over being consistent with their original stances. A unanimous majority can amplify normative pressure (the discomfort of being the lone dissenter) and may shift the operative decision rule from “Is this consistent with my view?” to “Why am I the only one disagreeing?”. This account is in line with the observation that participants conformed despite being told explicitly that the others were bots, suggesting that minimal humanization cues (faces, names, and response latency) can be sufficient to generate social presence for normative influence to operate.

Participants were not in any way incentivised to conform in this case, nor should they have derived any informational aspect from the bots. It might be the case that participants may partially treat a unanimous bot majority as an informational cue even for subjective judgments (although to a much reduced extent compared to objective ones). Although policy attitudes are not objectively right or wrong, coordinated responses can plausibly be interpreted as reflecting a rule-based process, a dataset, or aggregated expertise. Even though participants have been explained the bots have the decision making capacities of average people. Such an interpretation would be most likely when participants feel uncertain or lack confidence in their answers, consistent with the association between objective under-performance and higher conformity in both the objective and subjective domains.

5.3. Interpreting the Support-Oppose Null Result

We do not find a statistically significant difference between conformity comparing supporting to opposing majorities. Importantly, this null result is unlikely to be driven by an ambiguous or weak manipulation at the level of the stimuli presented to participants. In the subjective domain, the bot majority position was generated deterministically from each participant’s own baseline response for every item, all three bots displayed the same response, shifted by a fixed magnitude of two points. In the support condition, the bots remained on the participant’s baseline side while moving toward greater extremity In the oppose condition, the bots moved two points toward the counter-position (with neutral baseline responses disambiguated using the participant’s overall policy leaning). Thus, each trial presented a clear three-against-one consensus that was systematically aligned either with an intensified version of the participant’s baseline stance or with its opposition.

Substantively, the absence of a support-oppose asymmetry may therefore reflect a setting in which unanimity dominates directional alignment. Once a three-against-one consensus is established, the social fact of unanimity may outweigh whether the majority is congruent or incongruent with baseline stance. At the same time, two features of the present study may hide support-oppose differences. First, political self-placement in our sample is heavily skewed to the left, which reduces effective ideological distance and can make some “opposing” responses appear as moderate deviations rather than clear counter-positions. Second, the coarse response scale combined with a fixed two-step shift may limit measurement resolution, particularly near endpoints where responses saturate. In combination, these factors can yield a strong majority signal while reducing power to detect directional effects.

Future work could address these issues by:

- 1.

- Recruiting ideologically heterogeneous samples and explicitly testing subgroup differences

- 2.

- Modeling ideological distance between baseline and bot position as a continuous predictor at the item level

- 3.

- Increasing response resolution (e.g., 7- or 9-point scales) or varying the magnitude of the bot shift

- 4.

- Adding a brief post-task manipulation check to directly measure perceived bot stance

5.4. Individual Differences: Personality and Risk Preferences

The personality results suggest that objective and subjective conformity may be supported by partly distinct individual-level mechanisms. The positive association between Conscientiousness and objective conformity is consistent with accounts emphasizing error aversion and performance motivation where conscientious individuals may experience higher disutility from being wrong and may therefore place greater weight on a unanimous majority signal when answering factual questions under uncertainty. This interpretation aligns with the informational-versus-normative framework because conformity in objective tasks can be rationalized as improving accuracy rather than merely reducing social friction.

By contrast, the positive association between Openness and subjective conformity is plausibly consistent with receptivity to alternative viewpoints and a greater willingness to revise attitudes in response to social information. In attitude domains without a verifiable “correct” answer, openness may facilitate engagement with counterarguments or extreme variants of one’s baseline position, increasing susceptibility to majority cues even when those cues originate from transparently artificial agents. Importantly, this pattern should not be read as “gullibility”, rather it may reflect a greater propensity to treat social information including bot provided signals as informative or worth considering.

The negative coefficient for political self-placement in the subjective model is directionally consistent with the idea that stronger ideological commitment reduces malleability, but given the pronounced left skew of the sample, this relationship should be interpreted cautiously. Finally, the weak association between risk aversion and subjective conformity may reflect avoidance of social or cognitive conflict. Risk-averse individuals may prefer the lower-friction option of aligning with an apparent consensus when outcomes feel uncertain or socially consequential. This interpretation remains tentative and would benefit from designs that separate reputational or social-risk concerns from purely instrumental uncertainty.

5.5. Social Engagement with Bots Under Disclosure

Post-experimental measures suggest that disclosure did not fully eliminate social engagement with the bots. In free responses, many participants described the bots using social language rather than foregrounding their nonhuman identity, and trust-game transfers to a bot were substantial. These measures cannot distinguish cleanly between inattention to instructions, forgetting over time, and deliberate “as-if” social responding despite awareness of artificial identity. Nevertheless, the pattern is consistent with the broader conclusion that minimal anthropomorphic cues can make bot identity less salient in practice, complementing the main conformity results and underscoring the relevance of bot-mediated consensus signals in online environments.

6. Conclusions

This study shows that a unanimous majority of bots can elicit substantial conformity even when participants are explicitly informed that the majority is made of artificial agents. Conformity emerged in both objective (general-knowledge) and subjective (economic-policy) judgments, and objective and subjective conformity were positively related, suggesting that susceptibility to majority influence generalizes across domains. We also find no statistically significant difference between supporting and opposing majorities in the subjective domain, consistent with the idea that unanimity and perceived consensus may dominate directional alignment in this setting.

Conformity varied systematically across individuals. Female participants conformed more than male participants in both domains. Moreover, correlational evidence suggests that objective and subjective conformity may be associated with different individual-difference profiles, specifically objective conformity is most strongly linked to Conscientiousness (and possibly Neuroticism), whereas subjective conformity is most strongly linked to Openness. In addition, lower performance on objective items and lower confidence are associated with higher conformity, consistent with a role for uncertainty in amplifying reliance on a unanimous majority signal.

Beyond these empirical patterns, the findings have a direct implication for online environments. Transparent disclosure that an account is a bot may not be sufficient to neutralize its social influence when minimal humanization cues (profile pictures, nicknames, and human-like response timing) are present. In settings where automated accounts can appear as a coherent, unanimous “crowd” repeated exposure to aligned bot output can manufacture perceived consensus and shift judgments even without sophisticated persuasion. Given that modern AI systems can generate fluent and context-sensitive interactions, the influence observed here with comparatively simple agents may underestimate real-world effects.

Taken together, these results suggest that effective responses should not rely on labeling alone. Mitigation likely requires limiting automated accounts’ ability to blend into ordinary social interaction and, in particular, restricting their contribution to consensus signals (e.g., prominence in comment threads, apparent unanimity, and aggregate indicators). This points toward strong need for stricter access controls (such as account verification, constraints on automated activity, and interface designs that reduce the visibility or impact of coordinated, unanimous blocs) when accessing online environments, alongside continued research using more diverse samples and richer interaction paradigms.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/soc16010038/s1, Data.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.O. and L.E.; methodology, T.O.; software, T.O.; validation, L.E.; formal analysis, T.O.; investigation, T.O.; resources, T.O.; data curation, T.O.; writing—original draft preparation, T.O.; writing—review and editing, L.E.; visualization, T.O.; supervision, L.E.; project administration, L.E.; funding acquisition, L.E. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the chair of Organizational Behavior at the Alfred-Weber-Institut at Universität Heidelberg.

Institutional Review Board Statement

During the data collection period ([May 2022] to [August 2022]), the Alfred Weber Institute at Heidelberg University did not maintain an internal ethics committee specifically for non-interventional behavioral economics experiments involving adult participants. However, our laboratory operated under a general ethics review committee, which concurrently handled ethical review and approval responsibilities, authorizing research projects meeting its standards. The research protocol received formal approval from the General Ethics Review Committee of the Alfred Weber Institute laboratory at Heidelberg University, confirming full compliance with all laboratory requirements. The approval date is 23 May 2022.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the Supplementary Materials. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Christiane Schwieren for providing access to the subject pool of Universität Heidelberg. During the preparation of this study, the author(s) used [25] for the purposes of generating avatars. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Asch, S.E. Effects of group pressure upon the modification and distortion of judgments. Groups Leadersh. Men 1951, 1951, 177–190. [Google Scholar]

- Asch, S.E. Opinions and social pressure. Sci. Am. 1955, 193, 31–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asch, S.E. Studies of independence and conformity: I. A minority of one against a unanimous majority. Psychol. Monogr. Gen. Appl. 1956, 70, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beran, T.; Drefs, M.; Kaba, A.; Al Baz, N.; Al Harbi, N. Conformity of responses among graduate students in an online environment. Internet High. Educ. 2015, 25, 63–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijenayake, S.; Van Berkel, N.; Kostakos, V.; Goncalves, J. Quantifying the effect of social presence on online social conformity. Proc. ACM Hum.-Comput. Interact. 2020, 4, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijenayake, S.; van Berkel, N.; Kostakos, V.; Goncalves, J. Impact of contextual and personal determinants on online social conformity. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2020, 108, 106302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Li, S.; Zhang, Y.; Zhai, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Feng, C. Different drives of herding: An exploratory study of motivations underlying social conformity. PsyCh J. 2022, 11, 247–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, X.; Chen, C.; Yam, K.C.; Cao, L.; Li, W.; Guan, J.; Zhao, P.; Dong, X.; Lin, Y. Adults still can’t resist: A social robot can induce normative conformity. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2022, 127, 107041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salomons, N.; Van Der Linden, M.; Strohkorb Sebo, S.; Scassellati, B. Humans conform to robots: Disambiguating trust, truth, and conformity. In Proceedings of the ACM/IEEE International Conference on Human-Robot Interaction (HRI 2018), Chicago, IL, USA, 5–8 March 2018; pp. 187–195. [Google Scholar]

- Kyrlitsias, C.; Michael-Grigoriou, D. Asch conformity experiment using immersive virtual reality. Comput. Animat. Virtual Worlds 2018, 29, e1804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukumaran, A.; Vezich, S.; McHugh, M.; Nass, C. Normative influences on thoughtful online participation. In Proceedings of the CHI ’11: Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 7–12 May 2011; pp. 3401–3410. [Google Scholar]

- Colliander, J. “This is fake news”: Investigating the role of conformity to other users’ views when commenting on and spreading disinformation in social media. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2019, 97, 202–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijenayake, S.; van Berkel, N.; Kostakos, V.; Goncalves, J. Quantifying determinants of social conformity in an online debating website. Int. J. Hum.-Comput. Stud. 2022, 158, 102743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quattrociocchi, W.; Scala, A.; Sunstein, C.R. Echo Chambers on Facebook. SSRN 2016, 2795110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elon Musk Commissioned This Bot Analysis in His Fight with Twitter. Now It Shows What He Could Face If He Takes over the Platform. Available online: https://edition.cnn.com/2022/10/10/tech/elon-musk-twitter-bot-analysis-cyabra/index.html (accessed on 3 March 2023).

- Does Facebook Really Know How Many Fake Accounts It Has? Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2019/01/30/technology/facebook-fake-accounts.html (accessed on 3 March 2023).

- Twitter Bots Appear to Be Be in Line with the Company’s Estimate of Below 5%—But You Wouldn’t Know It from How Much They Tweet, Researchers Say. Available online: https://www.businessinsider.com/twitter-bots-comprise-less-than-5-but-tweet-more-2022-9 (accessed on 3 March 2023).

- Toelch, U.; Dolan, R. Informational and Normative Influences in Conformity from a Neurocomputational Perspective. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2015, 19, 579–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cialdini, R.B.; Goldstein, N.J. Social influence: Compliance and conformity. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2004, 55, 591–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, D.L.; Schonger, M.; Wickens, C. oTree—An open-source platform for laboratory, online, and field experiments. J. Behav. Exp. Financ. 2016, 9, 88–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckel, C.C.; Grossman, P.J. Forecasting risk attitudes: An experimental study using actual and forecast gamble choices. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 2008, 68, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, F.R.; John, D.; Lüdtke, O.; Schupp, J.; Wagner, G.G. Short assessment of the Big Five: Robust across survey methods except telephone interviewing. Behav. Res. Methods 2011, 43, 548–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berg, J.; Dickhaut, J.; McCabe, K. Trust, reciprocity, and social history. Games Econ. Behav. 1995, 10, 122–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 8values Survey. Available online: https://8values.github.io/ (accessed on 14 October 2021).

- This Person Does Not Exist. Available online: https://thispersondoesnotexist.com/ (accessed on 14 October 2021).

- Bond, R. Group size and conformity. Group Process. Intergroup Relat. 2005, 8, 331–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.