Abstract

In socio-economically disadvantaged communities, the challenges faced by children with special needs are often overshadowed by more visible issues such as poverty, family instability, and substance abuse. Children, especially those with special needs, are particularly vulnerable in these settings as they are disproportionately impacted by intersecting adversities, including neglect, exploitation, and limited access to education and healthcare. These adversities create a vicious cycle, where disability exacerbates financial hardship, and in turn, economic deprivation negatively impacts early childhood development, further entrenching disability. Conventional models, which require physical presence and focus primarily on diagnosis and treatment within clinical settings, often fail to address the broader social, environmental, and contextual complexities of disability. We propose an Information Technology-based Exit Pathway as an innovative, scalable solution to disrupt this cycle. Anchored in the five pillars of the Community-Based Rehabilitation (CBR) matrix of Health, Education, Livelihood, Social, and Empowerment, the model envisions a multi-level digital platform that facilitates coordinated support across individual, familial, educational, community, regional, and national levels. By improving access to services, fostering inclusive networks, and enabling early intervention, the proposed approach aims to promote equity, social inclusion, and sustainable development for children with special needs in marginalized communities.

1. Introduction

“Neurodivergent” refers to individuals whose neurocognitive functioning or neurodevelopmental patterns differ from societal norms, without necessarily indicating the presence of a clinical disorder. In contrast, a neurodevelopmental disorder (NDD) specifically refers to conditions where neurocognitive functions significantly deviate from age-expected norm, resulting in notable functional impairments [1]. Common NDDs include intellectual disability, autism spectrum disorder (ASD), attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), communication disorders, specific learning disorders, and motor disorders [2,3].

The estimated prevalence of NDDs among children and adolescents aged 0–18 varies by context. Globally, an estimated 52.9 million children under the age of five (95% uncertainty interval: 48.7–57.3), or 8.4% of that age group, were living with developmental disabilities, with highest prevalence recorded in south Asia (9.7%), in 2016. Of these, 95% were from low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), underscoring a major disparity in global child health [4]. There is limited information on the prevalence of NDDs in LMICs. For instance, in Sri Lanka (a lower-middle-income country), the prevalence of ASD was reported in 2009 as 10.7 per 1000 [5], which is comparable to the 2008 figure of 11.3 per 1000 in the United States [6]. However, the prevalence of other NDDs in Sri Lanka remains unknown to date. NDDs are associated with a wide range of negative outcomes, including increased experiences of anxiety and depression, impaired social functioning, reduced quality of life, and diminished earning potential, particularly within inclusive educational settings [7]. However, evidence suggest that early diagnosis and intervention can significantly enhance the quality of life by minimizing the risk of academic failure, school dropout, and more serious problems in later life [8].

NDDs such as ASD and ADHD often present significant challenges in mainstream educational environments, especially in the context of inclusive education. While inclusive education seeks to integrate students with NDDs into regular classrooms, success depends heavily on appropriate support systems. Most children and adolescents with NDDs struggle to regulate their emotions and manage stress highlighting the need for increased awareness and understanding among parents, educators, and other peers [9]. Despite this need, reports have consistently identified severe shortage of resources, training, and support for teachers tasked with implementing inclusive practice. For instance, in the sub-Saharan African and Asia-Pacific regions with a majority of its countries classified under LMICs, several barriers to implementing inclusive education for pupils with developmental disabilities have been identified. These include unclear policies, limited teacher training, and a lack of support for educators. At the same time, notable opportunities exist, such as teachers’ commitment to inclusion, collaboration among educators, and the involvement of non-governmental organizations (NGOs). These challenges and opportunities are present across national and community contexts, as well as at the school, classroom, and individual teacher levels [10,11,12].

Sri Lanka, an Asian country falling under LMICs, has made significant progress towards disability-inclusive education through several key policy milestones. Firstly, Sri Lanka is a signatory to both the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC) and Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD), having ratified the former in 1991 [13,14]. The Protection of Rights of Persons with Disabilities Act (No. 28 of 1996) [15] and the Compulsory Education Ordinance in 1997 helped establish the legal basis for educational access and inclusion. Subsequent policies, such as the National Policy on Disability (2003), National Policy on Inclusive Education and the launch of the Framework of Action for Inclusive Education (2009), CRPD (2016), Education Sector Development Plan (2018–2025), and Inclusive Education Plan (2019–2030) have further reinforced Sri Lanka’s commitment to accessible and equitable education system for individuals with disabilities [14,15]. Complementary national programs, including the National Strategic Plan for Child Health [16] and Adolescent and Youth Health [17], as well as National Maternal and Child Health Policy of Sri Lanka (Extraordinary Gazette No. 1760/32 of 2012), play a crucial role in guiding initiatives for children with special needs [18].

Despite these efforts, recent reports of disability-inclusive education practices in Sri Lanka reveal that implementation remains inadequate. Gaps in infrastructure, training, and service delivery have resulted in continued discrimination against individuals with disabilities [14]. These shortcomings are often rooted in a persistent reliance on charitable and medical models in addressing disability, rather than rights-based and inclusive approaches. The medical model conceptualizes disability as an individual health condition or impairment requiring diagnosis, treatment, or cure, framing persons with disabilities primarily as patients. In contrast, the charity model views disability as a personal tragedy, positioning individuals as passive recipients of pity and care rather than as rights holders entitled to full participation in society [12].

This concept paper draws upon insights and observations gathered by members of the Global Research in Autism and Neurodiversity Consortium (GRAND Consortium), particularly during outreach activities conducted in socioeconomically disadvantaged regions of Sri Lanka.

2. Reflections from On-the-Ground Interactions

This study employed a retrospective, reflective qualitative approach to examine the hardships faced by children in socioeconomically disadvantaged communities, including both neurotypical and neurodivergent learners. The reflections were informed by prior, informal interactions with school principals, teachers, preschool educators, religious sisters, Grama Niladharies (village officers), development officers, parents, and caregivers during outreach activities previously conducted in disadvantaged regions of Sri Lanka. These activities included health campaigns, community meetings, workshops, networking events, and social media exchanges.

During a meeting of the GRAND Consortium, members drew upon these past observations and experiences to highlight the multifaceted challenges encountered by the target population. Detailed notes were taken to document the verbal exchanges at the meeting. A thematic analysis was subsequently undertaken, guided by Braun and Clarke’s six-phase approach [19]; (1) familiarisation with the data, (2) generation of initial codes, (3) searching for themes, (4) reviewing themes, (5) defining and naming themes, and (6) producing the report. This analytical process enabled a systematic interpretation of the shared reflections and observations.

Accounts of the GRAND Consortium participants, who were engaged in outreach activities in socioeconomically disadvantaged communities, were often shaped by broader socioeconomic hardships such as poverty, low parental education, limited access to healthcare, community-level neglect, inadequate nutrition, social stigma, hazardous living conditions, substance abuse, prostitution, and sexual exploitation. These pressing issues frequently overshadowed the needs of children with special educational needs. In such environments, neurotypical children often sought emotional support from teachers and peers rather than family members due to parental disengagement and household instability. Many children living in such communities bore adult-like responsibilities, including caregiving and household chores, which significantly limited their academic engagement and opportunities for recreation. Neurodivergent learners faced even greater challenges, compounded by undiagnosed or untreated conditions, limited awareness, and a lack of inclusive education practices. Teachers were generally untrained to support these children, leading to classroom segregation and social withdrawal. The absence of support services, such as counseling or shadow teachers, further marginalised these students, leaving their developmental and educational needs largely unmet. Furthermore, lack of awareness among teachers, parents, and caregivers often resulted in children with special needs not receiving specialized care, such as timely referral to child and adolescent mental health services, individualized education plans (IEPs), early intervention programs, or appropriate therapeutic support including speech, occupational, and behavioral therapies (GRAND Consortium, Personal communication, 2 August 2024).

Aforementioned observations can be organized into five key thematic areas: (1) Awareness and Identification Gaps, reflecting low community understanding of neurodevelopmental conditions; (2) Parental Engagement and Support Needs, highlighting emotional stress and lack of resources among caregivers; (3) Educational Barriers, including untrained educators and segregation practices; (4) Community Stigma and Safety Concerns, driven by fears of negative external influences; (5) Desire for Accessible Tools, expressing community interest in user-friendly technologies for early identification and support.

3. Interplay of Socio-Economic Disadvantage and Children with Special Needs

Lack of access to essential social and health services has been identified as a violation of the rights of persons with disability [20]. However, children with special needs in socio-economically disadvantaged communities often face delayed diagnosis, limited access to services, and poor long-term outcomes due to limited parental awareness, cultural beliefs, and inadequate formal and informal support systems [21,22]. Disability and economic deprivation are interconnected in a vicious cycle, where disability can lead to financial hardship, and economic deprivation increases the risk of impairment [23]. Neurodivergent children in socio-economically challenged communities often face heightened struggles where systemic inequalities and social hardships amplify the difficulties associated with their conditions as they are disproportionately affected by these intersecting adversities such as child abuse and neglect. To break this cycle, it is essential that the interconnected nature of these socioeconomic factors is identified and addressed through the implementation of holistic solutions. Formal education plays a crucial role in breaking this pattern by providing opportunities for economic stability and social inclusion [24]. Situational analysis in countries in the Arab World, Ethiopia and Iran have shared their insights on planning and development of services to address these unmet needs of children with special needs, particularly in low-resource settings [25,26,27].

4. Breaking the Cycle Through Digital Application-Based Exit Pathway

Digital solutions with the potential to break the cycle of socioeconomic disadvantage and disability include assistive technologies (AT) as well as complementary interventions such as caregiver support, teacher capacity building, school management systems, and community-level linkages. At the individual and family level, mobile mHealth screening apps (localised ATEC/M-CHAT tools) enable early identification and referral; mood-tracking and self-care apps (icon/emoji inputs with trend visualisations) reveal emotional patterns and prompt conversations; speech-generation/augmentative and alternative communication (AAC) solutions (tablet apps to low-tech devices) enable functional communication; video-modelling libraries provide short, culturally relevant demonstrations for home practice; and on-demand training modules let caregivers learn interventions at their own pace. At school, teacher dashboards and e-coaching support lesson adaptation and real-time professional development, while adaptive, child-centred apps, interactive e-books and educational games personalise learning and boost engagement; simple classroom response systems increase participation and on-task behaviour. Clinically, teletherapy/telerehabilitation platforms expand access to speech, behavioural and occupational therapies; wearable sensors and remote monitoring supply passive data (activity, sleep, events) to tailor care; and digital patient-reported outcomes (PROs) inform individual treatment and service planning. For coordination and navigation, searchable, map-based referral directories and case-management platforms (URN-linked multi-stakeholder records) streamline access and continuity of care, while moderated peer networks reduce isolation and share practical strategies. At the policy level, anonymised, aggregated dashboards provide evidence on screening coverage and service gaps, and privacy-preserving artificial intelligence (AI) engines can prioritise high-need cases and personalise referrals. Low-bandwidth/offline-first designs (SMS/IVR and cached content) ensure reach in rural or connectivity-limited settings. Advanced hardware (eye-gaze systems, dedicated AAC devices) and robotics extend support for higher-need children under professional supervision. Across domains, five implementation principles are essential: localisation (language and cultural adaptation); accessibility (low-literacy modes, voice prompts, offline features); privacy and ethics (URN, RBAC, encryption, opt-in data sharing); capacity building (training, tech support, ongoing coaching); and sustainability (affordable devices, open standards and interoperability with public services).

For instance, “Thrive by Five” app developed in partnership with the Minderoo Foundation and led by the University of Sydney’s Brain and Mind Centre, serves as a globally implemented model for culturally tailored, evidence-based early childhood development support. Its international launch took place in March 2022, with Indonesia being the first country to implement the full version of the app. Over the course of this three-year project, the app will be rolled out in 30 countries. Unlike many parenting apps, Thrive by Five uniquely integrates scientific insights with cultural and anthropological analyses of each country’s context. Through features like “Activity Pop Up,” it offers practical, play-based activities grounded in developmental science, encouraging participation from parents, siblings, grandparents, and trusted community members to foster collective parenting practices [28]. A protocol for a prospective mixed-methods, multi-site study evaluating the Thrive by Five app has been published, though findings are yet to be reported [29].

A growing body of research supports the use of ATs, ranging from simple applications to specialised robotic systems, as effective tools for enhancing learning, communication, and social engagement in young children with special needs. AT, encompassing tools, devices, and digital that enhance learning and communication has a great potential to play a vital role in realising the rights affirmed by the United Nations CRPD [30], by fostering inclusive education systems through targeted interventions, local support networks, and equity-focused policy frameworks.

4.1. Access and Registration

A secure and inclusive digital platform begins with robust user registration and access control. Registration of a child by a parent or legal guardian, with a unique reference number (URN) would ensure that each child’s record is uniquely identifiable, preventing duplication or mix-ups. It also facilitates secure and efficient linking of data across multiple services or agencies. Additionally, a URN allows easy tracking of a child’s progress and history over time. Importantly, using a URN instead of personal details helps protect privacy when sharing or aggregating data. Security measures such as encryption and identity verification protect sensitive information. To accommodate underserved or rural areas, the application should be developed to function in low-bandwidth internet connections with offline functionality, allowing users to continue accessing essential features even without continuous internet connectivity. Application should be freely accessible to all the users ensuring the access to in low-resource settings.

4.2. Multi-Stakeholder Profile and Personalisation Engine

To support a child’s development across education and healthcare, a centralized digital profile is proposed, enabling parents, caregivers, teachers, and health professionals to contribute relevant updates over time. Furthermore, institution based- dashboards could be included to support multi-tenants use such as educational institutions (Schools), therapy centers and NGOs. This would allow the relevant institute to oversee their multiple child profiles while respecting ethics and data protection policies. A URN would make this possible by securely linking records across systems, ensuring accurate identification, preventing duplication, and protecting privacy. This application could be further improved by incorporating a Role-Based Access Control (RBAC) system where each user group experiences a customized dashboard tailored to their functions and needs in the application and action rights to protect the data integrity and user privacy. Several studies identified significant improvement of user engagement on personalized, app-based neurodevelopmental and behavioral mHealth applications [31,32]. Furthermore, a machine learning engine could be embedded to improve user interactions by analyzing the user inputs over time to generate early alerts as required by the users. Continuous feedback loops by the users (parents, educational institutes, educators and NGOs) could be incorporated to improve the service quality of the application.

4.3. Communication and Coordination

This concept also envisions real-time communication tools to facilitate collaboration among families, professionals, and community workers. Messaging features may include text, voice recordings, and video calls, while group messaging could enable multi-party discussions for care planning. Automated reminders and a built-in calendar may support appointment management and task scheduling, reducing missed follow-ups and improving continuity of care.

4.4. Screening, Monitoring

The app may feature embedded screening tools and developmental monitoring functions, allowing users to track milestones and detect potential concerns early. Structured checklists, visual aids, and user-friendly input formats could support non-specialists in conducting basic assessments. A progress dashboard might summarize input data, offering caregivers and professionals a visual overview of developmental trends and intervention outcomes.

4.5. Mood Tracking and Self-Care

Mood tracking and self-care functions within the family portal support monitoring of both parental well-being and the emotional states of the child. At predefined intervals or following events such as therapy sessions or school transitions, the child, or a caregiver on the child’s behalf, selects from a set of intuitive icons or emojis (e.g., happy, sad, anxious, frustrated) and may provide a brief textual or audio description. Each entry is time stamped and aggregated into trend charts on the parental dashboard, enabling the identification of patterns and potential triggers, such as increased anxiety prior to homework or periods of elevated positive affect. These visual summaries facilitate recognition of emotional trends, guide supportive communication, and allow sharing of anonymised mood data with educators or therapists to coordinate emotion regulation strategies across home and school contexts.

4.6. Audio-Visuals and Gamification

In socioeconomically deprived communities, where literacy levels may be low and digital literacy limited, audio-based technologies such as audio prompts, voice messages, and text-to-speech can significantly enhance accessibility. These features allow parents of children with special needs to interact with the app through spoken guidance and auditory responses, reducing reliance on reading skills. By offering instructions, updates, and alerts in local languages, such technologies help ensure that critical information is understood, empowering caregivers to engage meaningfully in their child’s developmental journey regardless of their educational background. Speech generation tools, including both high-tech (iPad-based) and low-tech options, have demonstrated to improve communication outcomes and engagement in children with ASD and other developmental disabilities [33].

Additionally, including interactive visual content such as videos, infographics, and scenario-based learning modules could make the user interaction more efficient. Video modelling functions could enhance social interaction, emotion regulation, and academic behaviours, as demonstrated by previous studies [34,35,36]. Gamification techniques such as progress bars or interactive goal settings could also be incorporated to motivate the users in achieving the set objectives of the proposed application.

4.7. Education, Awareness and Advocacy

Educational resources are envisioned as a core part of the app, supporting caregivers and frontline workers with accessible, culturally appropriate content. The platform may offer videos, illustrated guides, and short modules organized by user type and topic. A central resource library could provide printable tools such as home activity sheets and caregiver handbooks, promoting knowledge sharing and practical skill development. Community-based initiatives can be strengthened using mobile applications or IT-based solutions that deliver event alerts of awareness campaigns, educational videos, and culturally relevant content to reduce stigma around neurodivergence. Additionally, storytelling features might enable users to share lived experiences, contributing to awareness campaigns and destigmatization efforts.

4.8. Service Linkage and Referrals

Mobile applications can help families and professionals track available diagnostic, healthcare, and educational services across regions, making it easier to locate and access nearby support. They can include searchable directories of regional centers, multidisciplinary teams, and community-based initiatives, with real-time updates on service availability, wait times, and eligibility criteria. In addition, these platforms can function as coordination tools for professionals and social workers, enabling collaborative planning and monitoring of interventions, particularly in underserved areas. By integrating alerts and a map-based interface, the apps can inform users about relevant health, education, and social support services, as well as upcoming events, based on their location and specific needs. Ultimately, such systems aim to reduce barriers to service access through a streamlined digital referral and navigation process.

4.9. Data Analytics and Policy Dashboards

The concept includes features for aggregating anonymized data to inform advocacy and service planning. Dashboards could present trends related to screening outcomes, service utilization, or unmet needs. These insights may support policymakers, NGOs, and researchers in designing more effective interventions. At the regional, national and international levels, the application could anonymise and aggregate data to generate insights for policymakers. Interactive graphical user interfaces (GUIs) would visualize indicators such as the number of children registered by region, types of neurodivergence medically diagnosed, and disparities in service needs versus those received. This evidence base would enable governments and other stakeholders to identify gaps in services, allocate resources effectively, and develop evidence-based inclusive policies. Such platforms could be integrated with existing public services, such as schools, clinics, NGOs, and government agencies, creating an ecosystem of care. Caseworkers and community health volunteers could also use the application to maintain continuity and coordination in service delivery. A secure opt-in international data-sharing feature would allow anonymized data to contribute to global research, funding efforts, and the development of cross-border best practices, while adhering strictly to ethical and data protection standards.

4.10. Scalability and Lifespan Transition Support

Furthermore, the application could be designed with future scalability in mind, supporting the neurodivergent youth as they transition into adulthood by addressing needs related to vocational training, employment accommodations, and workplace inclusion. This modular, user-centric architecture ensures that each child’s profile can be continually refined and enriched, facilitating timely, tailored support and fostering greater inclusion across educational and community settings. In doing so, the platform would not only support early development but also promote long-term, person-centered care and inclusion across the individual’s lifespan.

4.11. Linking Themes Identified to App Features

Table 1 illustrates how the key themes identified through our on-the-ground qualitative analysis directly inform the design of specific modules within the proposed digital application. For example, the persistent Awareness and Identification Gaps theme could be addressed by embedding validated screening instruments, educational videos, illustrated guides, and short modules with voice-guided prompts in local languages. The Parental Engagement and Support theme could be operationalised via a Family Empowerment Portal, which offers peer-to-peer networks and mental-health resources to bolster caregivers’ confidence and competence. To overcome Educational Barriers, the Teacher Dashboard integrates a video-modelling library, equipping educators with ready-to-use interventions and progress-tracking tools. Recognising Community Stigma and Safety concerns, the Secure URN Login and Push-Alert system provides a trusted channel for caregivers to receive timely check-in notifications, thereby enhancing both privacy and security. Finally, the Desire for Accessible Tools is satisfied by a multimodal interface—featuring visual cues, intuitive icons, and offline capability—so that users of all literacy levels and connectivity contexts can interact seamlessly with the platform. In this way, each application module is purpose-built to respond to the field-derived themes, ensuring that technological features are directly anchored in user-centred needs.

Table 1.

Mapping emergent field themes to corresponding digital application modules and the intended outcomes.

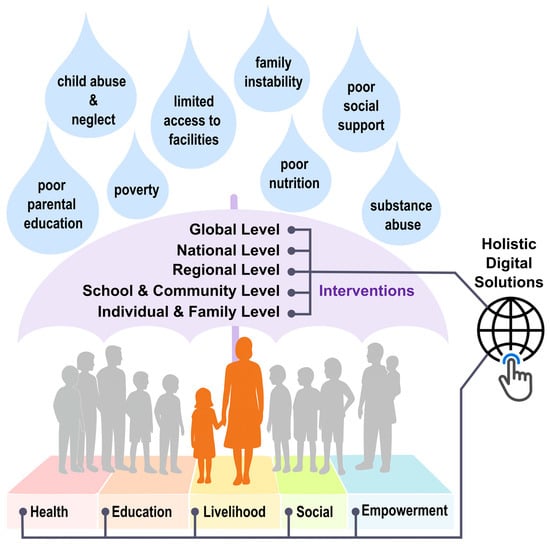

5. Aligning Digital Applications to the Community-Based Rehabilitation Matrix

Community-Based Rehabilitation (CBR) introduced by the World Health Organization (WHO) provides an effective exit from the vicious cycle of disability and financial hardship, especially in socioeconomically deprived communities [37]. By relying on family support, community volunteers, and primary health services, CBR avoids the high costs of hospital stays, long-distance travel, and the loss of income from work that often come with institutional rehabilitation. It reduces the financial burden on families, improves accessibility, and fosters community participation, creating sustainable local support systems. By integrating Health, Education, Livelihood, Social inclusion, and Empowerment, CBR could break the cycle of poverty and disability. Therefore, the conceptual framework of the proposed digital solution is grounded in the CBR Matrix (as illustrated in Figure 1). Aligning digital applications with the CBR matrix ensures that interventions address the multidimensional needs of children with special needs and their families. By mapping digital tools to the five key components of the matrix, health, education, livelihood, social, and empowerment, developers can design more inclusive and contextually relevant solutions.

Figure 1.

An integrated, holistic, IT-based approach to addressing challenges faced by children with special needs in socio-economically disadvantaged communities. This conceptual framework illustrates the use of digital solutions across multiple levels (individual, family, regional, national, and international). By structuring the application’s features around the five core components of the community-based rehabilitation (CBR) matrix (health, education, livelihood, social, and empowerment), it ensures that the intervention is holistic and community oriented.

5.1. Health

Digital health applications, such as embedded screening tools, teletherapy platforms, video demonstrations of therapeutic interventions, and symptom trackers, play a crucial role in delivering timely interventions to children with special needs. In countries with limited resources including Sri Lanka, national screening programs for neurodivergent children remain absent. This often results in late diagnosis, inadequate support, and lifelong consequences for both children and their families. Given the strain that national-level screening programmes can on health systems, decentralised digital applications offer a more inclusive and adaptive alternative. Importantly, these solutions identify and respond to each child’s needs, diagnosed or not, making them equally relevant for children with formal medical diagnoses and those with observable developmental or educational challenges without a clearly defined disorder. Embedded screening tools and questionnaires, adapted from validated instruments such as Autism Treatment Evaluation Checklist (ATEC) [38], and modified checklist for Autism in toddlers, revised with follow-up (M-CHAT-R/F) [39] could be culturally and linguistically tailored for diverse settings. To accommodate low-literacy settings, the interface could offer local-language versions incorporating voice prompts and intuitive visual cues.

At the individual level, early, personalized interventions such as behavioral, speech, and cognitive-behavioral therapies are essential for improving developmental outcomes. A push-notification system, enhanced by an AI-based recommendation engine, could alert users to upcoming clinic visits, therapy sessions, or community support events, filtering notifications for relevance to improve both uptake and user satisfaction.

A Sri Lankan study has demonstrated that parents can be effectively trained to deliver home-based interventions as full-time therapists, offering valuable guidance for the management of young children with autism [40]. One effective digital solution would be video demonstrations, which teach parents techniques for home-based implementation and reduce the need for repeated in-person sessions. Another is teletherapy platforms, which allow families to participate in sessions remotely and keep real-time communication with therapists. Together, these approaches save time, promote consistent skill reinforcement, enhance parental engagement, and ensure continuity of care.

Digital health interventions have been used to deliver non-pharmacological interventions, parent training, and mental health care for caregivers and children with ASD [31,32,41,42], and ADHD [43]. A study conducted in patients with a type of lysosomal storage disease has identified mobile Patient Reported Outcomes delivered via smartphones and wearable technologies as methods to capture remote, real-time insight into disease burden. This method has not only shown an excellent compliance rate but also generated a rich multidimensional dataset, therefore seem to be a potential strategy that can be adopted in managing children with special needs [44].

Higher levels of depression, burnout, stress, and anxiety indicate that parents of children with NDDs require substantial emotional, psychological, and practical support [45,46]. Family-based support programs, counseling, and group-based psychoeducation programs can also help alleviate the stresses that come with managing neurodivergence, while fostering a sense of empowerment for parents and caregivers [47].

5.2. Education

Schools support neurodivergent learners through inclusive education frameworks, integration of special education programs, targeted teacher training, and the implementation of IEPs. Peer education initiatives further promote social inclusion and reduce stigma. The development of IEPs can be facilitated by IT-based solutions such as school management systems with digital IEP management platforms, data-tracking tools, and collaborative online portals. These technologies allow educators and parents to share updates, monitor progress in real time, and make informed adjustments to goals and strategies, ensuring a more personalized and effective educational experience for the child. In a pilot trial, educators and parents used a mobile application for 8–10 weeks to supervise children’s learning, record patterns, and generate individual progress profiles. Most participants (90%) preferred drag-and-drop or touch-based interactions over conventional classroom methods. Over 84% of children, previously reluctant to use pencil and paper, developed prerequisite writing skills such as scribbling, tracing, joining dots, and copying. Additionally, 25% began reciprocating classroom greetings to teachers and peers. Performance metrics from each activity provided a basis for identifying learning patterns and revising IEPs [48]. Among the digital solutions investigated are tablet-based speech-generating devices for children with impaired communication skills [49], mobile applications designed to support children with graphical dyscalculia in improving numerical proficiency and number-writing skills [50], educational software and computer games [43].

5.3. Livelihood

Vocational training and microlearning apps could empower young individuals with special needs by enhancing job-related skills and improving employability. These platforms could offer flexible, accessible courses that cater to diverse abilities and learning paces. By linking training with job matching services, digital livelihood solutions contribute to economic independence and social inclusion for marginalized families.

5.4. Social Inclusion

Social interactive networking applications and family communication portals foster community engagement and peer support for children with special needs and their families. Promoting self-advocacy and autonomy will also play a crucial role in helping children feel more confident and capable in their interactions with others. Technology-based tools such as interactive applications and digital storytelling platforms can guide children in expressing their preferences, making choices, and practicing communication skills in a safe, structured, and engaging environment.

5.5. Empowerment

Digital advocacy and rights information platforms provide individuals and families with important knowledge to support self-advocacy and encourage community mobilization. Community mobilization means bringing people together to recognize common challenges and work jointly to solve them. These tools help raise awareness, build local leadership, increase participation, and promote cooperation with authorities to improve services and inclusion for children with disabilities. Families would benefit from an integrated empowerment portal offering resources such as educational materials, peer support networks, and automated appointment or milestone reminders.

5.6. Case Simulation: Connected Care Pathway for Autism

“X” is the second child in his family. During a routine family visit, his mother expressed concerns to the Public Health Midwife (PHM) about her son’s poor eye contact, speech delay, and tendency to walk on tiptoe. The PHM guided her to install an application developed by the Family Health Bureau that included self-administered screening tools.

After completing the assessment, the scores were concerning. The mother was advised to book an appointment with the nearest community pediatrician through the app. At the clinic, the pediatrician diagnosed the child with ASD. The child was registered in the app, and a Personal Identification Number (PIN) was sent to the mother’s email to enable secure access to his profile.

The diagnosis was notified to the Family Health Bureau, and both the PHM and the Medical Officer of Health (MOH) were informed. A personalized management plan was created. The pediatrician also prescribed several educational videos available in the app for the mother to watch, covering topics such as understanding ASD, home-based communication strategies, and behavioral support.

A multidisciplinary team (MDT) meeting was arranged via teleclinic. The MDT recommended speech and language therapy, occupational therapy, and counseling sessions for the mother, who was experiencing depression.

The PHM visited the child’s preschool, educated the teacher about ASD, and registered her on a web-based platform for teachers. This allowed the teacher to continuously document the child’s developmental progress and share updates directly with the community pediatrician. With support from the health ministry’s educational app, the teacher developed an IEP tailored to the child’s needs.

Through the app, the parents also received notifications about upcoming TV and radio programs on ASD, as well as workshops for parents conducted by various organizations. In line with public health coordination protocols, any organization planning a workshop within a community was required to inform the respective MOH office beforehand. This ensured the MOH could verify the program’s relevance, prevent duplication of services, and encourage wider community participation.

6. Potential Hurdles in Implementation and Recommendations

While digital and AI-driven solutions offer great promise, their integration into existing systems is met with substantial challenges. Key concerns include data privacy, ethical accountability, algorithmic bias, and the risk of widening existing inequities. The use of AI may also threaten human autonomy and introduce issues of transparency and trust, especially in vulnerable populations.

Practical barriers such as limited infrastructure (e.g., internet access, devices, servers), inadequate funding, and lack of training for educators and caregivers further complicate deployment. Institutional resistance and low digital literacy among stakeholders can delay or derail adoption. Ensuring sustainability, in terms of system maintenance, community engagement, and long-term scalability, is another critical concern.

To mitigate these challenges, we propose: (i) the development of a robust ethical framework; (ii) interdisciplinary collaboration across education, technology, and policy; and (iii) investment in training and capacity building. Additionally, establishing institutional policies and quality assurance protocols will support responsible implementation.

Addressing digital equity is critical to ensure inclusive access in under-resourced settings. This requires region-specific research to inform frameworks that reflect local cultural and educational contexts. Effective implementation also depends on collaboration with in-country partners and subject matter experts in early childhood development, education, medicine, psychology, and anthropology, ensuring that digital solutions are both technically appropriate and culturally relevant. Such interdisciplinary engagement strengthens the feasibility, sustainability, and impact of interventions for children with special needs [25,28].

For instance, one study highlighted that home visits were likely to reduce formality and enable the inclusion of fathers’ perspectives on ASD, as they were more often present at home than in clinic settings within this cultural context [25]. Diagnostic tools and digital tools need to be culturally adapted to ensure accurate assessment and interpretation of symptoms within the context of local beliefs, behaviors, and communication norms. Such attempts have been made in Sri Lanka [51] and Indonesia [29].

6.1. National-Level Interventions

National-level interventions are essential in ensuring systemic changes that can benefit neurodivergent children across the country. When government and non-governmental sectors work together a stochastic network of care can be created to guarantee equal access to education, health, and social services for children with special needs, regardless of their socio-economic background.

The collaborative efforts of national organizations in Sri Lanka illustrate how diverse sectors can work in synergy to develop effective frameworks that support individuals in need. Disability-inclusive education is a key focus shared by several ministries, including the Ministry of Education, Ministry of Health, Ministry of Social Welfare, Ministry of Women and Child Affairs, and the Ministry of Rural Development, Social Security and Community Empowerment. A notable example of this multisectoral collaboration is the establishment of the Ayati National Center for Children with Disabilities at the Faculty of Medicine, University of Kelaniya in Ragama. Clinical services are delivered through a partnership between the Faculty of Medicine and the Ministry of Health, while the center’s operations, including administration and maintenance, are supported by the Ayati Trust, a charitable organization in Sri Lanka. In addition to government initiatives, professional bodies such as the Sri Lanka Association for Child Development hold considerable potential to further strengthen the progress of disability-inclusive education across the country.

According to the National Guidelines and Minimum Standards for Child Development Centers in Sri Lanka, children with special needs should be placed in centers equipped to provide specialized care [52]. However, in practice, children enrolled in inclusive educational settings often do not receive the necessary support or tailored interventions, which hinders their learning progress and contributes to academic challenges.

To bridge the gap in access to information among socioeconomically deprived communities with low literacy levels, a technology-based solution such as a mobile application with voice-guided navigation, map integration, and icon-based interfaces can be developed. Such mobile application can display available disability-related services, including clinics, therapy centers, educational support units, and government offices, on a user-friendly map, with the option to filter by service type or distance. To overcome literacy barriers, the application should include audio instructions and local language support, allowing users to tap icons to hear service descriptions, operating hours, and contact information. A toolkit has been introduced to overcome culture-, technology-, language-related barriers to mHealth co-design in LMICs [53].

National education policies should actively adopt e-learning modules as a strategic tool to integrate neurodiversity into teacher training programs. Additionally, government funding for research into IT-based interventions can support the development of innovative solutions that address the needs of these children. For instance, several countries have developed good examples of national-level intervention programs. In the United Kingdom, the National Autistic Society (https://www.autism.org.uk/, accessed on 23 June 2025) has introduced e-learning modules covering different aspects. ASPECT- Autism Spectrum Australia (https://www.aspect.org.au/, accessed on 23 June 2025) has developed innovative remote support services for these identified places in addition to their well-established educational services and early intervention services.

6.2. Global-Level: International Collaboration for Neurodivergence

On a global scale, collaboration between countries and international organizations can help share best practices, research, and policies aimed at improving the lives of neurodivergent children. Conduction of global awareness campaigns that reach the wider community, can reduce stigma and promote greater understanding of neurodivergence, fostering a more inclusive world. International partnerships can also address disparities by focusing on low-resource settings, ensuring that neurodivergent children in these regions receive the support they need. Global organizations play an important role in advocating for universal access to education, healthcare, and social support systems, working to ensure that no child is left behind due to socio-economic disadvantage. By fostering cross-border collaborations, countries can learn from each other’s successes and challenges, creating a unified approach to supporting neurodivergent children worldwide.

International bodies involved in advancing disability-inclusive education and child development include a range of organizations working across advocacy, policy, capacity-building, and service delivery. Key players such as UNICEF, WHO, UNESCO, and the Global Partnership for Education focus on promoting inclusive education, healthcare, and the rights of neurodivergent and marginalized children globally [30,54,55]. Regional organizations like the Asia-Pacific Development Center on Disability (https://www.apcdfoundation.org/, accessed on 23 June 2025) enhance local capacity through training and collaboration. Collectively, these international and multinational organizations play a vital role in fostering equity and inclusion for children with diverse needs worldwide. These organizations and groups come together as a support web of service delivery that targets multiple facets of childhood neurodivergence. Together they strive to make sure that the socioeconomic status in each society should not be a hindrance to acquiring basic services and facilities.

The UNCRC emphasizes the right of children with disabilities to receive special care and appropriate assistance based on available resources, ensuring access to education, healthcare, rehabilitation, and other essential services to promote their full social integration and individual development, with support provided free of charge whenever possible [56]. The United Nations CRPD is an international human rights treaty that aims to promote, protect, and ensure the full and equal enjoyment of all human rights and fundamental freedoms by persons with disabilities, while fostering respect for their inherent dignity. It clarifies how rights apply to persons with disabilities, identifies necessary adaptations for effective exercise of these rights, and highlights areas where rights have been violated, emphasizing the need for reinforced protection [57]. Countries should ratify and implement the CRPD, update the laws to comply with the CRPD, promote awareness, ensure accessibility, allocate resources to health as well as the social sectors, protect against discrimination, foster international cooperation, and involve persons with disabilities in decision-making to uphold their rights and dignity, States Parties to the Convention are required to allocate resources toward enhancing the social determinants of health, including housing, employment opportunities, and social integration, while addressing societal stigma. Simultaneously, investment in the healthcare sector should prioritize mental health promotion, early diagnostic and therapeutic interventions, and the implementation of recovery-oriented, community-based mental health services [20].

International bodies such as the WHO, UN, and allied agencies can play a pivotal role in supporting holistic digital interventions for neurodivergent children in socioeconomically disadvantaged communities. They can provide policy and technical guidance by developing global standards and frameworks for digital health solutions, ensuring they are safe, effective, and culturally adaptable. These organizations can also mobilize funding through mechanisms such as the World Bank, UNDP, and the Global Partnership for Education, supporting infrastructure development and the integration of digital platforms into health and education systems. Capacity building initiatives, including training modules and tele-mentoring for health professionals, educators, and caregivers, can be implemented at scale. Furthermore, WHO and related entities can support monitoring and evaluation through the establishment of global observatories and cross-national research collaborations, enhancing evidence-based practices and responsible data use. Finally, international organizations can lead global advocacy efforts to reduce stigma, promote inclusion, and raise awareness about the potential of digital technologies to improve outcomes for neurodivergent individuals—aligning all these initiatives with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG), particularly SDG 3 (health), SDG 4 (education), and SDG 10 (reducing inequalities).

7. Conclusions

In conclusion, addressing the overshadowed challenges of neurodivergent children in socio-economically disadvantaged communities demands a holistic approach that combines awareness, resources, and inclusive policies. Digital applications offer a promising, sustainable, and cost-effective solution to the pressing challenge of supporting neurodivergent children, particularly in socio-economically disadvantaged communities. By structuring the platform around the five CBR domains, health, education, livelihood, social, and empowerment, the application would ensure a holistic and community-anchored intervention. Aligning the applications with the CBR matrix not only strengthens its theoretical foundation but also enhances its sustainability, and relevance across diverse socio-economic settings.

By leveraging technology to register and monitor children’s needs across various life stages, and enabling input from parents, educators, and health professionals, the strategy fosters a truly collaborative, child-centered approach. Its adaptability to local contexts, use of validated tools in accessible formats, and potential to integrate with existing services make it both versatile and scalable. Importantly, it reduces dependency on centralized screening programs, empowers families, and strengthens early intervention and long-term support systems. As such, this innovation holds significant potential to bridge the current gaps in care and inclusion, promoting equity and dignity for all children, regardless of their neurodevelopmental profile or social background.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.-L.R.I.; methodology, N.-L.R.I. and N.H.; data curation, N.H.; writing—original draft preparation, N.-L.R.I., N.H. and H.-A.C.H.; writing—review and editing, N.-L.R.I., N.H., U.D.S., A.K., S.M. and S.-A.M.H.K.; visualization, N.-L.R.I. and U.D.S.; supervision, N.-L.R.I.; project administration, N.-L.R.I.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge M. Dulce Estêvão from Universidade do Algarve-Escola Superior de Saúde, Faro, Portugal, for the moderation and insightful feedback. The authors used OpenAI’s ChatGPT (GPT-5, 2025) to generate human shadows for the illustration.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ADHD | Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder |

| AI | Artificial intelligence |

| ASD | Autism spectrum disorder |

| AT | Assistive technology |

| ATEC | Autism treatment evaluation checklist |

| CBR | Community-Based Rehabilitation |

| CRPD | Convention on the rights of persons with disabilities |

| GRAND | Global research in autism and neurodiversity |

| IEP | Individualized education plan |

| IT | Information technology |

| LMICs | Low- and middle-income countries |

| M-CHAT-R/F | Modified checklist for Autism in toddlers, revised with follow-up |

| MDT | multidisciplinary team |

| MOH | Medical officer of health |

| NDD | Neurodevelopmental disorder |

| NGO | Non-governmental organisation |

| PHM | Public health midwife |

| PIN | Personal identification number |

| PRO | Patient-reported outcome |

| RBAC | Role-based access control |

| SDG | Sustainable Development Goals |

| UN | United nations |

| UNCRC | United nations convention on the rights of the child |

| UNESCO | United nations educational, scientific and cultural organization |

| UNICEF | United nations international children’s emergency fund |

| URN | Unique reference number |

| WHO | World health organization |

References

- Shah, P.J.; Boilson, M.; Rutherford, M.; Prior, S.; Johnston, L.; Maciver, D.; Forsyth, K. Neurodevelopmental disorders and neurodiversity: Definition of terms from Scotland’s National Autism Implementation Team. Br. J. Psychiatry 2022, 221, 577–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris-Rosendahl, D.J.; Crocq, M.-A. Neurodevelopmental disorders—The history and future of a diagnostic concept. Dialogues Clin. Neurosci. 2020, 22, 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francés, L.; Ruiz, A.; Soler, C.V.; Francés, J.; Caules, J.; Hervás, A.; Carretero, C.; Cardona, B.; Quezada, E.; Fernández, A.; et al. Prevalence, comorbidities, and profiles of neurodevelopmental disorders according to the DSM-5-TR in children aged 6 years old in a European region. Front. Psychiatry 2023, 14, 1260747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olusanya, B.O.; Davis, A.C.; Wertlieb, D.; Boo, N.-Y.; Nair, M.K.C.; Halpern, R.; Kuper, H.; Breinbauer, C.; De Vries, P.J.; Gladstone, M.; et al. Developmental disabilities among children younger than 5 years in 195 countries and territories, 1990–2016: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet Glob. Health 2018, 6, e1100–e1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perera, H.; Wijewardena, K.; Aluthwelage, R. Screening of 18–24-month-old children for autism in a semi-urban community in Sri Lanka. J. Trop. Pediatr. 2009, 55, 402–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network Surveillance Year 2008 Principal Investigators; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Prevalence of autism spectrum disorders--Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network, 14 sites, United States, 2008. MMWR Surveill. Summ. 2012, 61, 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Landgren, V.; Svensson, L.; Törnhage, C.J.; Theodosious, M.; Gillberg, C.; Johnson, M.; Knez, R.; Landgren, M. Neurodevelopmental problems, general health and academic achievements in a school-based cohort of 11-year-old Swedish children. Acta Paediatr. 2024, 113, 506–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cloet, E.; Jansen, A.; Leys, M. Organizational perspectives and diagnostic evaluations for children with neurodevelopmental disorders. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2022, 64, 88–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berglund Melendez, A.; Malmsten, M.; Einberg, E.-L.; Clausson, E.K.; Garmy, P. Supporting students with neurodevelopment disorders in school health care—School nurses’ experiences. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Genovesi, E.; Jakobsson, C.; Nugent, L.; Hanlon, C.; Hoekstra, R.A. Stakeholder experiences, attitudes and perspectives on inclusive education for children with developmental disabilities in sub-Saharan Africa: A systematic review of qualitative studies. Autism 2022, 26, 1606–1625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, S.K.; Jeffries, D.; Chakraborty, A.; Carslake, T.; Lietz, P.; Rahayu, B.; Armstrong, D.; Kaushik, A.; Sundarsagar, K. Teacher professional development for disability inclusion in low- and middle-income Asia-Pacific countries: An evidence and gap map. Campbell Syst. Rev. 2022, 18, e1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimes, P.J.; dela Cruz, A. Mapping of Disability-Inclusive Education Practices in South Asia; United Nations Children’s Fund Regional Office for South Asia: Kathmandu, Nepal, 2021; Available online: https://www.unicef.org/rosa/media/16976/file/Regional%20Report.pdf (accessed on 21 February 2025).

- Department of Probation and Child Care Services. United Nation’s Convention on the Rights of the Child-UNCRC; Department of Probation and Child Care Services, Ministry of Women and Child Affairs: Battaramulla, Sri Lanka. Available online: https://www.probation.gov.lk/sProgram1_e.php?id=32 (accessed on 20 February 2025).

- Grimes, P.J.; dela Cruz, A. Disability-Inclusive Education Practices in Sri Lanka; United Nations Children’s Fund Regional Office for South Asia: Kathmandu, Nepal, 2021; Available online: https://www.unicef.org/rosa/media/17016/file/Country%20Profile%20-%20Sri%20Lanka.pdf (accessed on 21 February 2025).

- Protection of the Rights of Persons with Disabilities Act, Act, No. 28 of 1996. Available online: https://www.un.org/development/desa/disabilities/wp-content/uploads/sites/15/2019/12/Sri-Lanka_1996-Protection-of-the-Rights-of-Persons-with-Disabilities-Act-No.-28.pdf (accessed on 21 February 2025).

- Family Health Bureau. National Strategy Plan Child Health 2018–2025; Family Health Bureau, Ministry of Health: Colombo, Sri Lanka, 2016. Available online: https://fhb.health.gov.lk/strategic-plan/ (accessed on 20 February 2025).

- Family Health Bureau. National Strategic Plan for Adolescent and Youth Health 2018–2015; Family Health Bureau, Ministry of Health: Colombo, Sri Lanka, 2016. Available online: https://fhb.health.gov.lk/strategic-plan/ (accessed on 20 February 2025).

- Ministry of Health. National Maternal and Child Health Policy of Sri Lanka; The Gazette of the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka (Extraordinary), No. 1760/32; Ministry of Health: Colombo, Sri Lanka, 2012. Available online: https://documents.gov.lk/view/extra-gazettes/2012/5/1760-32_E.pdf (accessed on 20 February 2025).

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, N.; Sartorius, N. Impact of the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities on Mental Health Care: Way Forward. In Mental Health and Human Rights: The Challenges of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities to Mental Health Care; Gill, N., Sartorius, N., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 179–187. [Google Scholar]

- Zuckerman, K.E.; Chavez, A.E.; Regalado Murillo, C.; Lindly, O.J.; Reeder, J.A. Disparities in Familiarity With Developmental Disabilities Among Low-Income Parents. Acad. Pediatr. 2018, 18, 944–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porterfield, S.L.; McBride, T.D. The effect of poverty and caregiver education on perceived need and access to health services among children with special health care needs. Am. J. Public Health 2007, 97, 323–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sherratt, S. Ameliorating poverty-related communication and swallowing disabilities: Sustainable Development Goal 1. Int. J. Speech Lang. Pathol. 2023, 25, 32–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singal, N. Disability, poverty and education: Implications for policies and practices. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2011, 15, 1047–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samadi, S.A.; McConkey, R. Autism in Developing Countries: Lessons from Iran. Autism Res. Treat. 2011, 2011, 145359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taha, G.R.A.; Hussein, H. Autism Spectrum Disorders in Developing Countries: Lessons from the Arab World. In Comprehensive Guide to Autism; Patel, V.B., Preedy, V.R., Martin, C.R., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 2509–2531. [Google Scholar]

- Tekola, B.; Baheretibeb, Y.; Roth, I.; Tilahun, D.; Fekadu, A.; Hanlon, C.; Hoekstra, R.A. Challenges and opportunities to improve autism services in low-income countries: Lessons from a situational analysis in Ethiopia. Glob. Ment. Health 2016, 3, e21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crouse, J.J.; LaMonica, H.M.; Song, Y.J.C.; Boulton, K.A.; Rohleder, C.; DeMayo, M.M.; Wilson, C.E.; Loblay, V.; Hindmarsh, G.; Stratigos, T.; et al. Designing an App for Parents and Caregivers to Promote Cognitive and Socioemotional Development and Well-being Among Children Aged 0 to 5 Years in Diverse Cultural Settings: Scientific Framework. JMIR Pediatr. Parent. 2023, 6, e38921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- LaMonica, H.M.; Song, Y.J.C.; Loblay, V.; Ekambareshwar, M.; Naderbagi, A.; Zahed, I.U.M.; Troy, J.; Hickie, I.B. Promoting social, emotional, and cognitive development in early childhood: A protocol for early valuation of a culturally adapted digital tool for supporting optimal childrearing practices. Digit. Health 2024, 10, 20552076241242559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, E.M.; Huff, S.; Wescott, H.; Daniel, R.; Ebuenyi, I.D.; O’Donnell, J.; Maalim, M.; Zhang, W.; Khasnabis, C.; MacLachlan, M. Assistive technologies are central to the realization of the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. Disabil. Rehabil. Assist. Technol. 2024, 19, 486–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, B.L.; Nair, R.; Duggal, M.S.; Aishworiya, R.; Tong, H.J. Development of oral health resources and a mobile app for caregivers and autistic children through consensus building. Autism 2024, 28, 959–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lamash, L.; Gal, E.; Yaar, E.; Bedell, G. SPAN Website for Remote Intervention with Autistic Adolescents and Young Adults: Feasibility and Usability. Children 2023, 10, 1514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chazin, K.T.; Barton, E.E.; Ledford, J.R.; Pokorski, E.A. Implementation and Intervention Practices to Facilitate Communication Skills for a Child With Complex Communication Needs. J. Early Interv. 2018, 40, 138–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapin, S.E.; McNaughton, D.; Light, J.; McCoy, A.; Caron, J.; Lee, D.L. The effects of AAC video visual scene display technology on the communicative turns of preschoolers with autism spectrum disorder. Assist. Technol. 2022, 34, 577–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurnaz, E. Effectiveness of Video Self-Modeling in Teaching Unplugged Coding Skills to Children with Autism Spectrum Disorders. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kouo, J.L. The Effectiveness of a Packaged Intervention Including Point-of-View Video Modeling in Teaching Social Initiation Skills to Children with Autism Spectrum Disorders. Focus Autism Other Dev. Disabl. 2019, 34, 141–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raha, S.S.; Yip, S.; Ho, C.; Olayinka, O.; Peláez-Ballestas, I.; Rame-Montiel, A.K.; MacIsaac, R.; Henderson, R.; Kovacs Burns, K.; Bakal, J.; et al. Novel Application of the World Health Organization Community-Based Rehabilitation Matrix to Understand Services’ Contributions to Community Participation for Persons With Traumatic Spinal Cord Injury: A Mixed-Methods Study. Am. J. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2023, 102, 815–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahapatra, S.; Khokhlovich, E.; Martinez, S.; Kannel, B.; Edelson, S.M.; Vyshedskiy, A. Longitudinal Epidemiological Study of Autism Subgroups Using Autism Treatment Evaluation Checklist (ATEC) Score. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2020, 50, 1497–1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robins, D.L.; Casagrande, K.; Barton, M.; Chen, C.M.; Dumont-Mathieu, T.; Fein, D. Validation of the modified checklist for Autism in toddlers, revised with follow-up (M-CHAT-R/F). Pediatrics 2014, 133, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perera, H.; Jeewandara, K.C.; Seneviratne, S.; Guruge, C. Outcome of Home-Based Early Intervention for Autism in Sri Lanka: Follow-Up of a Cohort and Comparison with a Nonintervention Group. Biomed. Res. Int. 2016, 2016, 3284087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, S.J.; Hwang, J.; Hill, H.S.; Kervin, R.; Birtwell, K.B.; Torous, J.; McDougle, C.J.; Kim, J.W. Mobile device applications and treatment of autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis of effectiveness. Arch. Dis. Child. 2020, 105, 458–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philippe, T.J.; Sikder, N.; Jackson, A.; Koblanski, M.E.; Liow, E.; Pilarinos, A.; Vasarhelyi, K. Digital Health Interventions for Delivery of Mental Health Care: Systematic and Comprehensive Meta-Review. JMIR Ment. Health 2022, 9, e35159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gabarron, E.; Denecke, K.; Lopez-Campos, G. Evaluating the evidence: A systematic review of reviews of the effectiveness and safety of digital interventions for ADHD. BMC Psychiatry 2025, 25, 414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davies, E.H.; Johnston, J.; Toro, C.; Tifft, C.J. A feasibility study of mHealth and wearable technology in late onset GM2 gangliosidosis (Tay-Sachs and Sandhoff Disease). Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2020, 15, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kütük, M.Ö.; Tufan, A.E.; Kılıçaslan, F.; Güler, G.; Çelik, F.; Altıntaş, E.; Gökçen, C.; Karadağ, M.; Yektaş, Ç.; Mutluer, T.; et al. High Depression Symptoms and Burnout Levels Among Parents of Children with Autism Spectrum Disorders: A Multi-Center, Cross-Sectional, Case–Control Study. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2021, 51, 4086–4099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, K.K.S.; Leung, D.C.K. Linking Child Autism to Parental Depression and Anxiety: The Mediating Roles of Enacted and Felt Stigma. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2021, 51, 527–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ağırkan, M.; Koç, M.; Avcı, Ö.H. How effective are group-based psychoeducation programs for parents of children with ASD in Turkey? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2023, 139, 104554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazumdar, A.; Banerjee, M.; Chatterjee, B.; Saha, S.; Gupta, G.S. Mobile application based early educational intervention for children with autism-a pilot trial. Disabil. Rehabil. Assist. Technol. 2023, 18, 819–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gevarter, C.; Horan, K.; Sigafoos, J. Teaching Preschoolers With Autism to Use Different Speech-Generating Device Display Formats During Play: Intervention and Secondary Factors. Lang. Speech Hear. Serv. Sch. 2020, 51, 821–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rupasinghe, G.; Abeyweera, R.; Pushpananda, R.; Weerasinghe, R. A Mobile-Based Alphabet Learning Game To Intervene Dyslexia Among Children. In Proceedings of the 2020 20th International Conference on Advances in ICT for Emerging Regions (ICTer), Colombo, Sri Lanka, 4–7 November 2020; pp. 290–291. [Google Scholar]

- Perera, H.; Jeewandara, K.C.; Seneviratne, S.; Guruge, C. Culturally adapted pictorial screening tool for autism spectrum disorder: A new approach. World J. Clin. Pediatr. 2017, 6, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Child Protection Authority. National Guidelines and Minimum Standards for Child Development Centres in Sri Lanka; National Child Protection Authority: Kotte, Sri Lanka, 2019. Available online: https://childprotection.gov.lk/images/news/national-guidelines--minimum-standards-for-CDC-in-SL-e.pdf (accessed on 20 February 2025).

- Poulsen, A.; Hickie, I.B.; Alam, M.; Crouse, J.J.; Ekambareshwar, M.; Loblay, V.; Song, Y.J.C.; LaMonica, H.M. Overcoming barriers to mHealth co-design in low- and middle-income countries: A research toolkit. Inf. Technol. Dev. 2024, 30, 542–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ydo, Y. Inclusive education: Global priority, collective responsibility. Prospects 2020, 49, 97–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albright, A.; Bundy, D.A.P. The Global Partnership for Education: Forging a stronger partnership between health and education sectors to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals. Lancet Child Adolesc. Health 2018, 2, 473–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- General Assembly of the United Nations. Convention on the Rights of the Child; Treaty Series; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 1989; Volume 1577, pp. 44–61. Available online: https://treaties.un.org/doc/Publication/UNTS/Volume%201577/v1577.pdf (accessed on 20 February 2025).

- Hendriks, A. UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. Eur. J. Health Law 2007, 14, 273–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).