Tourism Gentrification and the Resignification of Cultural Heritage in Postmodern Urban Spaces in Latin America

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Postmodern Tourism

1.2. Hawley’s Theory of Socioeconomic Development

1.3. Tourism Space Evolution and Gentrification

1.4. Research Novelty and Contributions

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Socio-Economic Development

3.2. Identities

“On the other hand, if art and culture are your thing, this has to be your next home. The variety of events, museums, fairs, theatres, and other cultural proposals that this district constantly offers is incredible. Although not only that, because apart from finding a lot of history and tradition; Barranco also houses the best restaurants, cafes, and bars in the city. Entertainment here is assured.”[43]

Or the real estate company T&C that in the brochure for their “Aspiria” building comments the following: “Near the bohemian, artistic, and cultural heart of the district, this project proposes an immersion into the best that Barranco life offers us. (...) Ready to start breathing the experience of living in Barranco?”[44]

3.3. Tourism as an Evolution of Development and Identities

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- INEI. Censo Nacional 2017; Instituto Nacional de Estadística e Informática: Lima, Peru, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Tord, L.E. Barranco: Historia, Leyenda y Tradición; Universidad San Martin de Porres: Lima, Peru, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Time Out Editors. From Lisbon to Tokyo via Lagos: Arroios, Shimokitazawa and Onikan Top Time Out’s List of the World’s Coolest Neighbourhoods Right Now. Time Out 2019. Available online: https://www.timeout.com/about/latest-news/from-lisbon-to-tokyo-via-lagos-arroios-shimokitazawa-and-onikan-top-time-outs-list-of-the-worlds-coolest-neighbourhoods-right-now-091719 (accessed on 15 November 2024).

- Yahoo. Los 25 Barrios Más Hipsters del Mundo. Yahoo 2015. Available online: https://es-us.noticias.yahoo.com/fotos/los-25-barrios-más-hipsters-del-mundo-1418176327-slideshow/ (accessed on 15 November 2024).

- Santos, N. Barranco, el Barrio Más “indiespensable” de Lima. National Geographic 2019. Available online: https://viajes.nationalgeographic.com.es/a/visitar-barrio-barranco-lima_14802 (accessed on 15 November 2024).

- Casulá, C. Barranco, el Barrio Bohemio y Alternativo por Excelencia de Lima. El País 2022. Available online: https://elpais.com/elviajero/2022-10-04/barranco-el-barrio-bohemio-y-alternativo-por-excelencia-de-lima.html (accessed on 15 November 2024).

- MINCETUR. Movimiento Turístico en Lima; Ministerio de Comercio Exterior y Turismo: Lima, Peru, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Bauman, Z. Teoría Sociológica De La Posmodernidad. Espiral 1996, 5, 174–198. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, E. Principales tendencias en el turismo contemporáneo. Política Y Soc. 2005, 42, 11–24. Available online: https://revistas.ucm.es/index.php/POSO/article/view/POSO0505130011A (accessed on 15 November 2024).

- Bourdieu, P. Capital Cultural, Escuela Y Espacio Social; Siglo XXI: Mexico City, Mexico, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Percoco, J.I.; Vaschetto, M. La distinción en el extranjero: Los hipsters como post-turistas. Perspect. Rev. Cienc. Soc. 2020, 9, 379–400. [Google Scholar]

- Zepeda, H.E. Hipster o la lógica de la Cultura urbana bajo el Capitalismo. Estud. Sobre Las Cult. Contemp. 2017, 46, 111–134. [Google Scholar]

- Moscoso, F.V. Nuevas relaciones entre cultura, turismo y territorio en el contexto de la posmodernidad. PASOS. Rev. Tur. Y Patrim. Cult. 2021, 19, 845–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawley, A.H. Human Ecology: A Theory of Community Structure; Ronald Press Company: New York, NY, USA, 1950. [Google Scholar]

- Hawley, A.H. Human Ecology: A Theoretical Essay; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, N. La Nueva Frontera Urbana: Ciudad Revanchista y Gentrificación; Traficantes de sueños: Madrid, Spain, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Madrid, O.M. (Ed.) El Mercado Contra la Ciudad: Globalización, Gentrificación y Políticas Urbanas; Traficantes de sueños: Madrid, Spain, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Janoschka, M.; Sequera, J. Procesos de gentrificación y desplazamiento en América Latina, una perspectiva comparativista. In Desafíos Metropolitanos: Un Diálogo entre Europa y América Latina; Michelini, J.J., Ed.; Catarata: Madrid, Spain, 2014; pp. 82–104. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, F.; Wu, F.; Liu, Y.; Li, Z. The subjective wellbeing of migrants in Guangzhou, China: The impacts of the social and physical environment. Cities 2017, 60, 333–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartmann, M.; Jansson, A. Gentrification and the Right to the Geomedia City. Commun. Public 2024, 9, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gotham, K.F. Assessing and advancing research on tourism gentrification. Via Tour. Rev. 2018, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tussyadiah, I.P.; Fesenmaier, D.R. Mediating tourist experiences: Access to places via shared videos. Ann. Tour. Res. 2009, 36, 24–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamayo, A. Barranco: Historia, Cultura y Sentimiento de un Distrito; Argos: Lima, Peru, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Maurial MacKee, Á.; Estela Benavides, B.; Vidal Valladolid, M.A. Barranco Historia y Arquitectura: Idea Original del Arquitecto Juan Gunther Doering y Equipo de Investigación del IVUC; Universidad San Martín de Porres: Lima, Peru, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Del Busto Duthurburu, J.A. Historia y Leyenda del Viejo Barranco; Lumen: Lima, Peru, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigo Fernández, J.E. Barranco Eterno; Impresiones técnicas: Lima, Peru, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Vargas-Arana, G.; Utia-Shapiama, D. Universidades peruanas y su producción científica en el área de turismo. Comuni@Cción Rev. Investig. En Comun. Y Desarro. 2020, 11, 164–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spanish Language Academies Association. Diccionario de la Lengua Española. Available online: https://www.asale.org/damer/balneario (accessed on 15 November 2024).

- De La Cruz, L.D.; Rodríguez, I.R. Análisis de la Influencia de la Gentrificación en el Turismo Cultural en el Distrito de Barranco en Lima—Perú Durante el Periodo 2010–2017; Universidad de Lima: Lima, Peru, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- de Barranco, M. Propuesta de Plan de Concertado de Cultura; Municipalidad de Barranco: Lima, Peru, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Sequera, J.; Nofre, J. Touristification, transnational gentrification and urban change in Lisbon: The neighbourhood of Alfama. Urban Stud. 2020, 57, 3169–3189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iemura, T.; Jaramillo, J.; Sun, L.; Yamamoto, T. Population Decline and Urban Transformation by Tourism Gentrification in Kyoto City. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santa Cruz Celis, J.W. Territorios Fragmentados El Caso de la Costa Verde. Master’s Thesis, Universidad Católica de Perú, Lima, Peru, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Armas Asín, F. Una historia del turismo en el Perú. El Estado, los visitantes y los empresarios (1800–2000). Apunt. Rev. Cienc. Soc. 2020, 47, 220–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beingolea, M. Concejos Barranquinos; El Universo: Lima, Peru, 1921. [Google Scholar]

- Chávez Noriega, J. La Noche: El bar de Barranco que Sobrevivió a la Convulsionada Década del 90. El Comercio 2020. Available online: https://elcomercio.pe/somos/historias/la-noche-el-bar-de-barranco-que-sobrevivio-a-la-convulsionada-decada-del-90-pandemia-bares-coronavirus-noticia/ (accessed on 15 November 2024).

- Lescano-Méndez, G. Barranco: Más Teatro, Menos Violencia. Bachelor’s Thesis, Universidad de Piura, Piura, Peru, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Domínguez, I. Sociología del Modernismo; Melusina: Barcelona, Spain, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Brito Arrieche, E.A. Barranco Imaginado; Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú: Lima, Peru, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- García Herrera, C. Formación de la Cultura Turística en los Pobladores del Distrito de Barranco—Lima 2018. Master’s Thesis, Universidad César Vallejo, Lima, Peru, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Rivas García, A.I. Impacto Social del Turismo en el Distrito de Barranco bajo la Perspectiva del Residente. Bachelor’s Thesis, Universidad César Vallejo, Lima, Peru, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Venta de Departamentos en Barranco Concentra la Mayor Oferta de Viviendas. V&V Inmobiliaria 2018. Blog. Available online: https://vyv.pe/departamentos-en-barranco/venta-departamentos-barranco-concentra-la-mayor-oferta-viviendas/ (accessed on 15 November 2024).

- El Sol 170, tu Mejor Opción en Barranco. V&V Inmobiliaria 2021. Available online: https://vyv.pe/departamentos-en-barranco/barranco-el-sol-arte-y-cultura-departamentos/ (accessed on 15 November 2024).

- T&C. Folleto del edificio “Aspiria”; T&C Inmobiliaria: Lima, Peru, 2024; Available online: https://aspiriabarranco.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/ASPIRIA-brochure-digital.pdf (accessed on 15 November 2024).

- Schiaffino, J.A. Toribio Nitta, Jorge Odriozola y los Tablistas de Barranco Entre 1920 y 1940; Tipsal: Lima, Peru, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Bulnes Maella, G. La Ciudad de Los Molinos: Un siglo de tradición [1874–1974]; Editorial Monterrico: Lima, Peru, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Gauna, C.; De León, R.; Maria, R.; Dagostino, C. Las costas, regiones de desarrollo del turismo. PASOS. Rev. Tur. Y Patrim. Cult. 2020, 18, 703–706. [Google Scholar]

- Hinostroza, R. Mi Ciudad. La República, 24 October 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Lituma Siverio, F.H. Historia de las Calles de Barranco; Pakarina Editores: Lima, Peru, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Distrital, M. Plan de Desarrollo Concertado al 2021; Municipalidad de Barranco: Lima, Peru, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Nilsson, K.; Pérez-Blanco, E.S.; Castrechini, A.; Cole, T. Residents’ Perceptions of Tourism Gentrification in Traditional Industrial Areas Using Q Methodology. Sustainability 2023, 15, 15694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, Y.; Zhang, F.; Chen, L.; Liu, Y. Spatial and temporal evolution of tourism flows among 296 Chinese cities in the context of COVID-19: A study based on Baidu Index. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2024, 11, 262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, R.W. The concept of a tourist area cycle of evolution: Implications for management of resources. Can. Geogr. 1980, 24, 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertsatos, G.; Tsounis, N.; Tsitouras, A. Tourism Product Life-Cycle, Growth, and Environmental Sustainability. Sustainability 2024, 17, 1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Category | Source Type | Description | Time Period | Purpose/Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Sources | Historical Books | Documents specifically recording the district’s evolution | Various periods | Foundational historical documentation |

| Primary Sources | Digitized Archival Documentation | Barranco’s heritage materials housed in institutional repositories | Various periods | Official heritage records |

| Primary Sources | Pre-1990s Travel Guides | Contemporary perspectives on tourism appeal during different historical periods | Pre-1990s | Period-specific tourism insights |

| Primary Sources | Newspapers and Periodicals | Magazines and newspapers from National Library of Peru archive | 20th Century | First-hand contemporary accounts and journalistic perspectives |

| Secondary Sources | Novels | Literary works capturing the district’s cultural atmosphere across various epochs | Various epochs | Cultural and atmospheric context |

| Secondary Sources | Scholarly Works | Academic examination of Peru’s broader tourism history | Contemporary | National tourism contextualization |

| Criteria | Content | Dates | Relevant Element | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

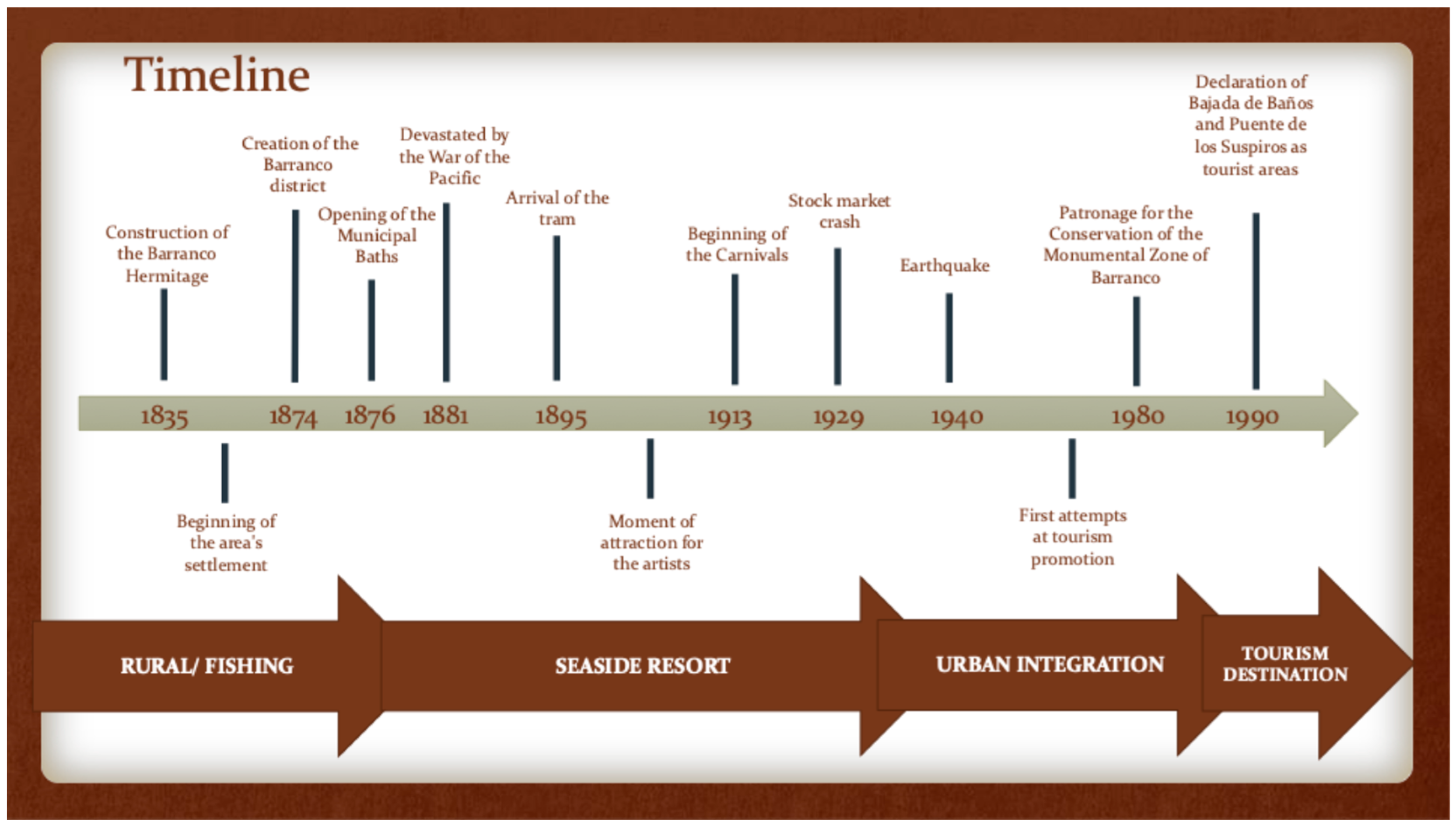

| Socio-economic Development | Fishing area, rural and vicinity to the hermitage | Until 1875 | Distant from Lima, with different Pacayares (rural estates) and fishing value until the creation of the hermitage with its settlement around it. The Lima-Chorrillos train in 1858 gave greater connection to the area with the capital. | [2,23,24] |

| District creation and first urbanization | From 1876 to early 1900 | It is given district status and different transportation means arrive, such as the train and the tram that made the Lima-Chorrillos connection. | [2,23,24] | |

| Settlement as a seaside resort district | 1900 to 1940 | The arrival of transportation means and the popularity of the Municipal Baths at the sea make Barranco considered one of the best seaside resorts, attracting upper class, upper-middle class, foreigners, and artists. | [2,23,24] | |

| Urbanization and fusion with the city | From 1940 to 1980 | The 1940 earthquake causes the district to gradually lose interest for the upper classes, with housing for middle and lower classes being built little by little, which eventually unites it with metropolitan Lima | [2,23,24] | |

| Differential district for leisure and tourist attractions | 1991 to present | Although it has been considered a monumental zone since 1973, it is not until 1990 that its eclectic and monumental architecture begins to be protected. This, together with its bohemian atmosphere, makes it increasingly seen as a tourist District. | [2,23,24] | |

| Identities | Mysticism | Until 1570 | Representation of Sulcovica through a rock on Barranco beach. | [25] |

| 19th century | Appearance of a light and an image. Creation of the Hermitage | [2,23] | ||

| Popular festivals | From 1913 to 1958 | The Barranco Carnival as the most socially horizontal in Lima | [23,24] | |

| The Sea | Until 1875 | Initial fishing zone | [2,23,25,26] | |

| From 1875 to 1960 | Seaside resort near Chorrillos (resort for authorities and upper class). Creation of the Municipal Baths. | [2,23,24,26] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Benedí-Artigas, J.; Sanagustín-Fons, V.; Moseñe-Fierro, J.A. Tourism Gentrification and the Resignification of Cultural Heritage in Postmodern Urban Spaces in Latin America. Societies 2025, 15, 184. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15070184

Benedí-Artigas J, Sanagustín-Fons V, Moseñe-Fierro JA. Tourism Gentrification and the Resignification of Cultural Heritage in Postmodern Urban Spaces in Latin America. Societies. 2025; 15(7):184. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15070184

Chicago/Turabian StyleBenedí-Artigas, Javier, Victoria Sanagustín-Fons, and J. Antonio Moseñe-Fierro. 2025. "Tourism Gentrification and the Resignification of Cultural Heritage in Postmodern Urban Spaces in Latin America" Societies 15, no. 7: 184. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15070184

APA StyleBenedí-Artigas, J., Sanagustín-Fons, V., & Moseñe-Fierro, J. A. (2025). Tourism Gentrification and the Resignification of Cultural Heritage in Postmodern Urban Spaces in Latin America. Societies, 15(7), 184. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15070184