Abstract

The realities of the COVID-19 pandemic and the decision to control it through a worldwide vaccination programme brought to the forefront the debates about people’s attitudes towards vaccines and vaccination in general, and people’s attitude towards COVID-19 vaccines and vaccination, in particular. This study focuses on trust in hospitals, as a predictor of Romanians’ hesitancy towards vaccination. The study utilizes a longitudinal approach, examining data from two distinct periods: 2019, before the COVID-19 pandemic; and 2021, during the COVID-19 pandemic. Our findings show that the COVID-19 pandemic has altered public attitudes towards vaccination and may also have compromised the link, considered implicit before the pandemic, between the level of trust in the medical system and favorable attitudes towards vaccination.

1. Theoretical Framework: Explaining Vaccine Hesitancy

In 2012, the concept of ‘vaccine hesitancy’ emerged as a recognized subfield within vaccine studies, following the establishment of a SAGE (Strategic Advisory Group of Experts) working group by the World Health Organization. This working group focused exclusively on defining vaccine hesitancy, determining its causes, and exploring strategies to reduce it. The research conducted by the SAGE working group led to the publication of a special edition of the journal Vaccine in 2015. One of the articles included in this special edition provided the definition of vaccine hesitancy as the behaviour of delaying acceptance or outright refusal of vaccination, despite the availability of vaccination services. It emphasized that vaccine hesitancy is a complex and context-specific phenomenon that varies across different time periods, locations, and vaccines. The article highlighted that factors such as complacency, convenience, and confidence play a significant role in influencing vaccine hesitancy [1].

Furthermore, the SAGE working group developed a Vaccine Hesitancy Determinants Matrix, which categorized determinants into three indicators: convenience, complacency, and confidence. This matrix was initially constructed based on a thorough literature review and subsequently refined through interviews with immunization managers from 13 countries [2]. The hesitancy determinants identified were contextual influence, individual and group influences and vaccine/vaccination—specific issues (see Table 1 below).

Table 1.

Vaccine Hesitancy Determinants Matrix.

The definition of ‘vaccine hesitancy’ and the Vaccine Hesitancy Determinants Matrix, developed by the World Health Organization’s SAGE working group dedicated to vaccine hesitancy, have become widely accepted as the scientific standards for analyzing and understanding vaccine hesitancy and we are adhering to them in this article. These frameworks are now used as reference points for European and global vaccination programs, as acknowledged by the European Commission in 2018 [3].

A recent meta-analysis of studies exploring vaccine hesitancy among parents has identified five distinct categories of hesitancy. These categories include: (1) risk conceptualization, (2) mistrust towards vaccine-related institutions, (3) alternative health beliefs, (4) philosophical views on parental responsibility, and (5) parents’ information levels about vaccination [4].

The first category, risk conceptualization, can be further divided into three subcategories: perceiving the risk of the vaccine, considering contextual risk factors, and evaluating the risk of the target disease.

The second category, mistrust, comprises three interconnected subcategories: mistrust towards institutions, questioning the integrity of healthcare professionals, and skepticism towards official vaccine information.

The third category, alternative health beliefs, encompasses three subcategories: beliefs about childhood immunity, beliefs about vaccine scheduling, and concerns about the perceived toxicity of vaccinations.

The fourth category, philosophical views, includes two subcategories: the burden of responsibility, and spiritual and religious beliefs.

The fifth category, parents’ information on vaccination, is characterized by three subcategories: lack of information, ambivalence in decision-making, and reliance on alternative sources of information [4].

This study provides valuable insights into the various factors contributing to vaccine hesitancy among parents, highlighting the need for tailored interventions and targeted communication strategies to address these concerns [4].

In a study conducted by Yunmi Chung, Jay Schamel, Allison Fisher, and Paula M. Frew [5], parents of children under 7 years old were surveyed online in 2012 and 2014, with a total of 5121 participants. The study revealed a typology consisting of four groups of vaccine hesitant parents: non-hesitant acceptors, hesitant acceptors, delayers, and refusers. The survey specifically assessed the vaccination decision regarding recommended non-influenza vaccines. According to the findings of their study, both family members and the internet were consistently identified as the second and third most frequently mentioned sources of information for non-hesitant acceptors and hesitant acceptors in both 2012 and 2014. Similarly, internet and family members were the second and third most cited sources for delayers in 2012. However, in 2014, family members and the internet emerged as the second and third most reported sources for delayers, while the internet and books were the second and third most reported sources for refusers. It is worth noting that, among parents who utilized the internet, a majority indicated their reliance on health information sites such as the CDC, AAP, and WebMD (76.6% [66.5–75.1%]). Additionally, search engines like Google and Yahoo! were also frequently used as a reliant source of information [5].

However, in the current literature on vaccination, especially in scientific reports from leading international organizations that were published before the COVID-19 pandemic, the focus was primarily on identifying different groups of people based on their perspectives on vaccines and vaccination. The goal was to find ways to convince people to get vaccinated. While this approach is understandable, there are three shortcomings that can be identified:

- (1)

- The main gap in this scientific literature is that it tends to treat all vaccines as a collective entity, without considering the specific type of vaccine or acknowledging the historical failures of certain vaccines that have been officially recognized.

- (2)

- Another gap is the non-specific and sometimes overly simplistic classification of people and their understanding of vaccines and vaccination. This approach overlooks the subjective and social realities of individuals, reducing them to their social-demographic profile and their decision to receive or not receive a vaccine.

- (3)

- The reasons and factors contributing to vaccine and vaccination hesitancy are often listed without a deep understanding of which populations hold which reasons and why. The focus is more on the reasons for non-vaccination rather than gaining insight into the specific factors influencing the opinion of different population groups.

In 2015, the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control published a report that aimed to outline the characteristics of hesitant populations, as well as the factors that enable or hinder vaccination, and successful interventions targeted at these populations [6]. This report drew conclusions from a comprehensive literature review of scientific articles published between 2004 and 2014, focusing on vaccines such as seasonal influenza, HPV, influenza A (H1N1), herpes zoster, and pertussis. The findings indicated that European populations exhibiting vaccine refusal or hesitancy included parents, mothers, religious communities, healthcare workers, immigrants, social media users, pregnant women, patients with chronic diseases, and the elderly [6]. The reasons for their hesitancy were categorized into three groups, as proposed by Larson et al. (2014) [7]: (1) contextual influences, (2) individual and social group influences, and (3) vaccine and vaccination-specific issues [6]. Contextual influences encompassed factors such as conspiracy theories, religious fatalism, myths about vaccines, and negative media exposure. Individual and social group influences referred to vaccine-related beliefs that arise from the social environment. Lastly, vaccine and vaccination-specific issues involved problems related to access, price, and insufficient testing [6].

Is vaccine refusal a different phenomenon than vaccine/vaccination hesitancy? The answer is very nuanced and depends primarily on the way we look at this phenomenon. From an attitudinal perspective and in terms of quantification, vaccine refusal represents the extreme end of the scale measuring trust in vaccines. It is important to note that, when studying trust in vaccines, we are examining not only individuals’ trust in their own vaccination but also the trust adults have in vaccinating their children [8]. Another important point is that vaccination refusal is a qualitatively different phenomenon, much more irrational and harder to combat than hesitancy. In fact, the difference between hesitancy and refusal to get vaccinated is rather poorly studied. Hesitancy is seen as encompassing more variable behaviours compared to the firm rejection of vaccines, a population often referred to in the literature as “anti-vaxxers”.

If we take the COVID-19 pandemic as a benchmark, in the case of Romania, we notice that, around the time of the vaccine’s appearance, the percentage of refusal (not hesitation) of the anti-COVID-19 vaccine was significantly higher than the percentage of refusal of traditional vaccinations. Of course, this can also be explained by the novelty of the vaccine, although the matter carries a small paradox—after the historic lockdown in 2020, it was expected that the public would become more favorable to vaccination than before the pandemic. The year 2021 revealed that hesitancy and especially anti-vaccinism (the opposition to vaccines and vaccination policies) were evident during the COVID-19 pandemic, with anti-vaccinism particularly gaining traction through specific narratives [9].

Based on an extensive review of the literature [10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42], we have developed a typology of theoretical approaches pertaining to the acceptance or refusal of vaccination. The causal models related to vaccination acceptance, hesitancy, or refusal can be summarized as follows:

- Models of primary differences: These models attribute variations in vaccination opinions to differences in how the vaccine and vaccination are perceived across different socio-demographic categories, such as age, education, sex, nationality, and religion [16,17,18].

- Communication models: This set of models emphasizes the importance of the communication channel through which information about the vaccine, virus, pandemic, and vaccination process is conveyed and shared. The source of information plays a significant role in shaping opinions [19,20]. In 2024, another umbrella review showed that, so far, studies on COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy have pinpointed information dissemination and misinformation as the main causes [22].

- Psychosociological models: These models focus on the explanatory power of psychosociological variables that are associated with acceptance or hesitancy towards vaccination [21].

- Models of distrust in scientific and medical knowledge: In these models, variations in acceptance, refusal, or hesitancy towards vaccination are primarily attributed to distrust in vaccines, medical distrust, and scientific illiteracy [10,11].

- Conspiracy models: These models posit that attitudinal variations towards vaccination are primarily influenced by a lack of trust in authorities, the propagation of conspiracy theories, and the belief in hidden intentions associated with the organization of the vaccination process by those in power [12,13,14,15].

Our results align with the findings of prior studies, which have presented substantial evidence linking trust and confidence in government to vaccine decision-making [23,24,25]. According to these studies, a lack of trust and confidence in government and authorities heightens the likelihood of vaccine hesitancy and refusal [24,26,27,28,29,35,36,37,38].

The problem is that, with the COVID-19 pandemic, there is an overlap between the discourse of political authorities and that of medical authorities. Vaccination was a priority on the agenda officially announced by representatives of state institutions, but also by representatives of the health system and of the medical world.

For the period before the COVID-19 pandemic studies showed, at least for Romania, an obvious link between trust in the medical system (and, in particular, trust in hospitals and doctors) and acceptance of vaccination [30]. The effects of the pandemic on this correlation are insufficiently studied and the results are much more nuanced and contextual than before the pandemic [29,31,32].

A recent study on COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in Romania identified the state’s crisis management as the main factor behind the country’s level of hesitancy towards COVID-19 vaccination. The study found that the state was unable to control three variables: fears of the COVID-19 vaccine, conspiracy theories regarding COVID-19, and trust in government’s management of COVID-19 [30]. Although trust was taken into consideration, the study refers only to three institutions: the national Parliament, the European Union, and the Directorate of Public Health [30]. This is where our study makes an interesting contribution, focusing on trust in hospitals as another key that might unlock a new and deeper understanding of the global vaccine hesitancy phenomenon.

2. Materials and Methods

In Romania, reporting of COVID-19 vaccination ceased in March 2022. The latest government announcement is dated 13 March 2022, and reported a total of 8,080,704 individuals vaccinated with a complete vaccination regimen (Dose I and Booster) (The Romanian Government, 2022), out of a total of 16,174,719 individuals aged 15 years and older (National Institute of Statistics, 2022). This means that, as of March 2022, the COVID-19 vaccination rate was only 49.96% among the entire eligible population.

With 2,912,705 confirmed cases of COVID-19 as of June 2022 and 65,714 deaths due to infection with the SARS-COV-2 virus (Authority for the digitization of Romania, 2022), it should be noted that, as of June 2022, the Romanian government has decided to no longer publish aggregated data on the epidemiological situation. Under these circumstances, it can be said that the national vaccination campaign in Romania has been a partial failure. The purpose of this study is to identify whether there is a touch of skepticism regarding vaccination in general within Romanian society that led to the population being hesitant to vaccinate against COVID-19, and especially if trust in hospitals has played a role in the public’s attitude towards vaccination.

This research is based on a comparative analysis of data collected through two nationally representative opinion surveys. The first survey was conducted from 21 January to 11 February 2019, on a sample of 2115 individuals. The sample was multi-stratified, probabilistic, and representative of the population of Romania, with a maximum allowable data error of ±2.1% at a 95% confidence level. The method used was an opinion survey based on a questionnaire sent by interviewers to the respondents’ homes. The questionnaires were administered in all counties of Romania and in the sectors of the Bucharest Municipality. The study was conducted by INSCOP Research, a private local institute for public opinion research, in collaboration with the Faculty of Sociology and Social Work at the University of Bucharest, commissioned by the National Society of Family Medicine in Romania and coordinated by Darie Cristea and Gabriel Jderu (both from the University of Bucharest) [33].

The second survey was conducted from 1 October to 10 October 2021, on a sample of 1002 individuals. The sample was multi-stratified, probabilistic, and representative of the population of Romania, with a maximum allowable data error of ±3.1% at a 95% confidence level. The method used was an opinion survey based on a questionnaire administered through telephone interviews (CATI). The questionnaires were administered in all counties of Romania and in the sectors of the capital city, Bucharest [34].

Both surveys (2019 and 2021) were standard sociological opinion polls and did not raise particular ethical issues. The respondents were informed that no personal data was collected and that their anonymity was guaranteed. Participation was voluntary, and all respondents provided informed consent before starting the survey. Data collection followed the ethical protocols established by the University of Bucharest and the Institute of Political Sciences and International Relations (within the Romanian Academy). The methodology of both surveys was approved by the ethics committee of the Faculty of Sociology and Social Work—University of Bucharest before data collection.

Using the two surveys mentioned above as a basis, we have analyzed a series of correlations between the following variables: trust in hospitals and attitude towards vaccination (2019) and, likewise, for the data from 2021. We have also correlated different sources of information regarding vaccination with the attitude towards vaccination for both surveys, and no significant correlations have emerged, or the resulting correlations have been very weak. Next, we will focus on the relationship between trust in hospitals in Romania and the attitude towards vaccination in the year prior to the COVID-19 pandemic (2019) and in the second year of the pandemic (2021) as some interesting elements have emerged in this regard, which are worth discussing.

3. Results

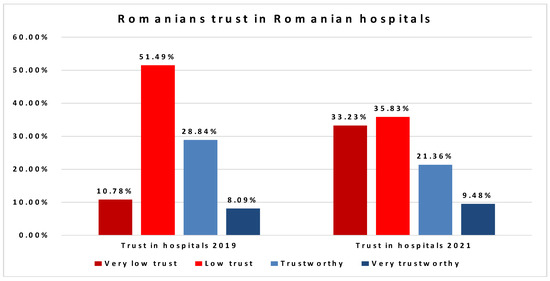

If we measure trust in hospitals on a four-point scale (very high, high, low, very low), we can observe that the average levels of trust/distrust have changed substantially (see Figure 1 below). While until 2019 the hospital environment in Romania was relatively stable, with all its flaws and resulting dissatisfaction, after a year-and-a-half of the pandemic, the situation had changed. Access to hospitals, even in their existing state, was restricted and subject to COVID-19 protocols, or in the early stages of the pandemic, hospitals became quarantine places for those infected with SARS-CoV-2, including asymptomatic individuals. Therefore, the idea of a hospital is starting to be associated, in this context, with that of authority, even politics, to a greater extent than before, when hospitals were only associated in the collective imagination with poor health conditions and concerned only individuals with health issues. In 2021, compared to 2019, the percentage of those with trust in hospitals decreased slightly, while the percentage of those with very low trust increased significantly (see Figure 1). Overall, the trust/distrust ratio did not change much (30–68% in 2021, compared to 36–61% in 2019).

Figure 1.

Romanians’ trust in hospitals in their country in 2019 vs. 2021.

In this phase, it is difficult to understand what lies behind this change in numbers. When correlating this variable with attitudes towards vaccination, things become clearer.

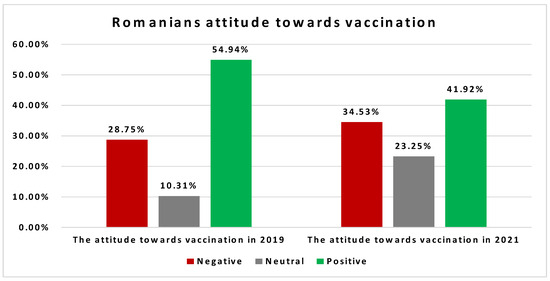

Before referring to this, it must be mentioned that in 2021 attitudes towards vaccination in Romania had changed significantly compared to 2019 (because of what happened during the COVID-19 pandemic, of course; note also that the first anti-COVID-19 vaccine started to be distributed globally in December 2020), (see Figure 2). Anti-COVID-19 vaccination has increased the number of hesitant individuals, increased negative attitudes towards vaccination, and decreased the percentage of favorability towards vaccination (see the graph below). This issue has been somewhat paradoxical. Before the pandemic, vaccines were a common, routine matter for children and entirely optional (the flu vaccine) for adults in Romania. The pandemic brought the vaccine as a necessity, but the way the vaccination programme and vaccination-related information were managed in Romania led to a decrease in the popularity of the idea of vaccination itself. In other words, before the pandemic, vaccination was not as questionable for the Romanian public as it became after the pandemic outbreak.

Figure 2.

Attitudes towards vaccination in 2019 and 2021.

Returning to the correlation between attitudes towards vaccination and trust in hospitals, our results show the following: for the data from 2019, trust in hospitals correlates with a positive attitude towards vaccination (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Correlation between trust in hospitals in 2019 and attitude towards vaccination in 2019.

In 2021, in the context where vaccination is primarily associated with the pandemic, there is no longer a significant statistical association between the two variables (see Table 3). What is the explanation for this? In a stable environment, trust in hospitals extends to trust in the vaccination routine. The shock of the pandemic disrupted and weakened trust in medical authorities, hospitals, and vaccination. This explanatory pattern also disappears.

Table 3.

Correlation between trust in hospitals in 2021 and attitude towards vaccination in 2021.

Furthermore, the fact that attitudes towards vaccination do not correlate with the source of information about vaccination (see Table 4) falls into the same realm of transformations: no type of media has a coherent message in this regard, and it is difficult to blame one type of media or another for the decline in trust in vaccination, considering that, at different stages of the pandemic, from authorities to media sources, there has not been a carefully structured message or strategy, but rather contradictory ones.

Table 4.

Correlation between attitudes towards vaccination in 2021 and sources of information about the vaccine in 2021.

Beyond the channels of information, whether we are talking about the press, social media, or government websites, attitudes towards vaccination are not statistically associated with sources of information such as the family doctor, friends, or family of the respondents. This shows us the failure of communication campaigns on this topic, as concerns regarding issues associated with COVID-19 vaccination have not been alleviated. In another representative national survey conducted in September 2021, it was found that among those who had not been vaccinated, 28% stated that they did not trust the vaccine, 14% believed they did not need it, 12% feared adverse effects, 11% declared having medical conditions incompatible with the vaccine, 9% claimed that the virus did not exist, and 6% refused vaccination on principle, without any specific reason (IRES, 2021).

The poor results of the vaccination campaign in Romania are not related to trust in hospitals or the media, but are based on distrust in the Romanian political system, as seen in Table 5 below. From Table 5, we can observe the existence of a statistically weak association between the population’s trust in the ruling elite and their attitude towards vaccination.

Table 5.

Correlation between attitude towards vaccination in 2021 and the population’s trust in the government, parliament, and president.

4. Discussion

In 2019, the World Health Organization (WHO) recognized vaccine hesitancy as a global health threat [38]. Vaccine hesitancy is, as such, not a new phenomenon; it has been observed with both newly approved childhood vaccines, and those that have been in use for a longer period of time [39,40].

Most of the literature on vaccine hesitancy published prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, with a few exceptions, has persistent shortcomings, which are also reflected in studies published in 2020 and 2021. Furthermore, these shortcomings are particularly pronounced in studies on COVID-19 vaccination [10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42]. Firstly, these studies often employ a generalized analysis of people’s attitudes towards vaccines and vaccination, thereby overlooking the ways in which individuals differentiate between various vaccine types. It is important to note that the term “vaccine” encompasses a wide range of specific vaccine types, such as those used for long-standing diseases like polio and measles, as well as vaccines for common cold-causing viruses or failed vaccines like the one for avian flu. Therefore, a more nuanced classification based on vaccine type would be expected, accompanied by an examination of people’s attitudes towards each specific type. Secondly, individuals are frequently categorized into two groups: those who choose to receive the vaccine, and those who do not. This results in a simplistic black-and-white classification that neglects the fundamental principle of constructing categories in scientific research. Categories should be specific, of similar size, and comprise individuals who share distinct characteristics and traits, rather than being solely based on a single general action.

Although some experts expected that, after a first year of pandemic full of practically unprecedented restrictions for several generations, the emergence of the anti-COVID-19 vaccine would be welcomed by the general public, things did not turn out that way. Moreover, the way attitudes towards vaccination were formed in 2021 and 2022 has, at least in the short term, affected the public’s trust, however little that was, in vaccines and routine vaccination. A good example illustrating the decline in vaccination rates for other types of vaccines as a consequence of COVID-19 pandemic is an analysis on DTP3 vaccination in Europe between 2012 and 2023. This analysis covers the periods before, during, and after the COVID-19 pandemic [39].

If we examine the relationship between trust in hospitals and attitudes towards vaccination before the pandemic, we can see a correlation in the case of Romania. Vaccination was most likely associated with something that the medical system does for citizens, and usually, when we refer to vaccination, the assumption is that we think more about childhood vaccines. Like in other countries around the world, the COVID-19 pandemic was received as a shock, and as it was prolonged, public solidarity with the measures imposed by authorities decreased. However, the emergence of the vaccine, available in Romania from the second year of the pandemic (2021), was not received as well as authorities expected and definitely not as well as in other countries (e.g., the UK). As seen in Graph 2, attitudes of refusal and hesitancy towards anti-COVID-19 vaccination have significantly increased compared to figures regarding vaccination in general from 2019.

Nevertheless, as we have demonstrated above, this development cannot be solely attributed to trust in the medical system [29,30]. Doctors have been at the forefront of the media and public communication during the pandemic in Romania, and the vaccination campaign has been led by a military doctor (the military is an institution with high trust in our country, in contrast to political institutions). The correlations studied above show that the public perceived this omnipresence of doctors not so much as a “dictatorship of medical competence,” but as a mix of communication coming from political institutions (compromised in trust) and medical representatives.

Practically, the previously very likely explanatory model, where trust in the medical system corresponds to trust in vaccination, is no longer as easily applicable after 2020, when the “purity” of these two variables becomes questionable. In other words, neither is the medical system the apolitical one we knew, nor is vaccination perceived as purely scientific/dependent on evidence-based medicine [35,39,40,41,42].

The COVID-19 pandemic has replaced the classic doctor/hospital-vaccination dyad with a much more complex referential. The political system, the health system, hospitals, and doctors, but also public communication, have found their place in this more complex referential that has somehow overturned the way we relate to vaccination [23,24,27,28,29].

At least in Romania’s case, vaccination was before the pandemic a problem that referred rather to the vaccination of children and was quasi-mandatory because it was not disputed by anyone and centered on those vaccinations necessary to include children in school communities. The most common vaccine for adults was the flu vaccine, obviously non-mandatory and, therefore, not problematic for most of the adult population (regularly, about 20% of the population is vaccinated against influenza in Romania, so not even people who agree with vaccination resort to this vaccine).

5. Conclusions

The pandemic brought to the forefront the vaccination of adults with new generation vaccines. Vaccination appeared as a necessity, as an emergency, and in some countries, as mandatory. The messaging of the political, administrative and medical authorities was mixed; the media initially supported the authorities’ efforts to manage the pandemic and later diversified their discourse. The hospitals no longer have the same image as before the pandemic.

The conclusions are simple: the pandemic has not only decreased trust in vaccination, the government and the medical system, but has also created a lack of predictability on this subject in the Romanian society. It is no longer sufficient to assess trust in doctors and the medical system in order to evaluate the population’s attitude towards vaccination, just as it is no longer sufficient to look at the subject’s source of information to “read” their attitude towards vaccination.

As mentioned above, Romania is generally a country with low trust in institutions. But before the pandemic, there was a positive correlation between trust in hospitals and the acceptance of vaccination. The management of the pandemic and the vaccination campaign have resulted in this correlation disappearing. Trust in hospitals has not decreased, but the positive attitude towards vaccination did, and more importantly, part of the public has detached vaccination from the image of the hospital, doctors or medical system. We observed that, during the COVID-19 pandemic, a series of changes occurred in the triad comprising medical and medically related information, trust in medical institutions, and vaccine hesitancy. Thus, the relationship between these three factors is not a simple linear one; there are numerous important contextual factors that most likely vary from society to society, depending on their cultural and historical context.

The issue of vaccination remains contentious and is characterized by a small paradox—although at the beginning of the pandemic it was expected that vaccination would be accepted by the public as the only solution to escaping pandemic restrictions, the pandemic has produced a resurgence in anti-vaccination discourses, probably due to the shift of discussions about vaccination from the medical imaginary to the political one.

For future research on the complex interdependencies between medical and medically related information, trust in medical institutions, and vaccine hesitancy, we consider that the urgency lies in improving the operationalization of concepts such as information, trust (in medical institutions) and skepticism through a series of studies with mixed research design. Regarding medical and medically related information, there is a need to study and understand the consumption of medical information and medically related information, answering questions such as the following: What is the information? What type of language is used in that information? Is there a typology of the information? How do people decode information? Concerning trust (in medical institutions), future studies should first analyze trust at the level of each institution that has a medical and/or health related function—starting with preventive medicine (social medicine), followed by primary medicine and family doctors, emergency medicine, hospitals, medical staff and treatment. As for skepticism towards science, particularly that focused on medical sciences, a starting point would be to first understand the public’s new conceptualisation of experts and answer questions such as the following: At what point in recent history did the public started to doubt the expert? Who took the place of the expert?

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, V.M., D.C., B.F., D.-G.I., A.A.R. and R.M.; methodology, V.M., D.C., B.F. and D.-G.I.; software, D.-G.I.; validation, V.M., D.C., B.F. and D.-G.I.; formal analysis, V.M., D.C., B.F., D.-G.I., A.A.R. and R.M.; investigation, V.M., D.C., B.F., D.-G.I., A.A.R. and R.M.; resources, V.M., D.C., B.F. and D.-G.I.; data curation, D.-G.I.; writing—original draft preparation, V.M., D.C., B.F., D.-G.I., A.A.R. and R.M.; writing—review and editing, V.M., D.C., B.F., D.-G.I., A.A.R. and R.M.; visualization, V.M., D.C., B.F. and D.-G.I.; supervision, V.M. and D.C.; project administration, V.M. and D.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the ethics committee of the Faculty of Sociology and Social Work—University of Bucharest (protocol code: no. 1/18.01.2019 and date of approval: 18 January 2019).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- MacDonald, N.E.; Eskola, J.; Liang, X.; Chaudhuri, M.; Dube, E.; Gellin, B.; Goldstein, S.; Larson, H.; Manzo, M.L.; Reingold, A.; et al. Vaccine hesitancy: Definition, scope and determinants. Vaccine 2015, 33, 4161–4164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dubé, E.; Gagnon, D.; Nickels, E.; Jeram, S.; Schuster, M. Mapping vaccine hesitancy—Country-specific characteristics of a global phenomenon. Vaccine 2014, 32, 6649–6654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Comission. Vaccination Programmes and Health Systems in the Europena Union. In Report of the Expert Panel on Effective Ways of Investing in Health; Publication Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Crescitelli, M.D.; Ghirotto, L.; Sisson, H.; Sarli, L.; Artioli, G.; Bassi, M.C.; Appicciutoli, G.; Hayter, M. A meta-synthesis study of the key elements involved in childhood vaccine hesitancy. Public Health 2020, 180, 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, Y.; Schamel, J.; Fisher, A.; Frew, P.M. Influences on Immunization Decision-Making among US Parents of Young Children. Matern. Child Health J. 2017, 21, 2178–2187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC). Rapid Literature Review on Motivating Hesitant Population Groups in Europe to Vaccinate; Technical Report; ECDC: Stockholm, Sweden, 2015.

- Larson, H.J.; Jarrett, C.; Eckersberger, E.; Smith, D.M.D.; Paterson, P. Understanding vaccine hesitancy around vaccines and vaccination from a global perspective: A systematic review of published literature, 2007–2012. Vaccine 2014, 32, 2150–2159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilkey, M.B.; Magnus, B.E.; Reiter, P.L.; McRee, A.-L.; Dempsey, A.F.; Brewer, N.T. The Vaccination Confidence Scale: A brief measure of parents’ vaccination beliefs. Vaccine 2014, 32, 6259–6265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cristea, D.; Petrescu, D.A.; Ghișoiu, C. Vaccine Refusal in Romania. An Estimation Based on Public Opinion Surveys. Proc. Rom. Acad. Ser. B Chem. Life Sci. Geosci. 2021, 23, 25–32. [Google Scholar]

- Goldenberg, M.J. Vaccines, values and science. CMAJ 2019, 191, E397–E398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boshra, M.S.; Hussein, R.R.S.; Mohsen, M.; Elberry, A.A.; Altyar, A.E.; Tammam, M.; Sarhan, R.M. A battle against COVID-19: Vaccine hesitancy and awareness with a comparative study between Sinopharm and AstraZeneca. Vaccines 2022, 10, 292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.K.; Ham, J.H.; Jang, D.H.; Lee, J.Y.; Jang, W.M. Political ideologies, government trust, and COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in South Korea: A cross-sectional survey. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 10655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savoia, E.; Su, M.; Piltch-Loeb, R.; Masterson, E.; Testa, M.A. COVID-19 vaccine early skepticism, misinformation and informational needs among essential workers in the USA. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 13244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wynen, J.; de Beeck, S.O.; Verhoest, K.; Glavina, M.; Six, F.; Van Damme, P.; Beutels, P.; Hendrickx, G.; Pepermans, K. Taking a COVID-19 vaccine or not? Do trust in government and trust in experts help us to understand vaccination intention? Adm. Soc. 2022, 54, 1875–1901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Luo, X.; Jia, H. Is it all a conspiracy? Conspiracy theories and people’s attitude to COVID-19 vaccination. Vaccines 2021, 9, 1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlShurman, B.A.; Khan, A.F.; Mac, C.; Majeed, M.; Butt, Z.A. What demographic, social, and contextual factors influence the intention to use COVID-19 vaccines: A scoping review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 9342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kosarkova, A.; Malinakova, K.; van Dijk, J.P.; Tavel, P. Vaccine refusal in the czech republic is associated with being spiritual but not religiously affiliated. Vaccines 2021, 9, 1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sallam, M.; Al-Sanafi, M.; Sallam, M. A global map of COVID-19 vaccine acceptance rates per country: An updated concise narrative review. J. Multidiscip. Healthc. 2022, 15, 21–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garett, R.; Young, S.D. Online misinformation and vaccine hesitancy. Transl. Behav. Med. 2021, 11, 2194–2199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baraybar-Fernández, A.; Arrufat-Martín, S.; Rubira-García, R. Public information, traditional media and social networks during the COVID-19 crisis in Spain. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cristea, D.; Ilie, D.-G.; Constantinescu, C.; Fîrțală, V. Vaccinating against COVID-19: The correlation between pro-vaccination attitudes and the belief that our peers want to get vaccinated. Vaccines 2021, 9, 1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahbeni, T.A.; Satapathy, P.; Itumalla, R.; Marzo, R.R.; Mugheed, K.A.; Khatib, M.N.; Gaidhane, S.; Zahiruddin, Q.S.; Rabaan, A.A.; Alrasheed, H.A.; et al. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy: Umbrella review of systematic reviews and meta-analysis. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2024, 10, e54769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.; Whetten, K.; Omer, S.; Pan, W.; Salmon, D. Hurdles to herd immunity: Distrust of government and vaccine refusal in the US, 2002–2003. Vaccine 2016, 34, 3972–3978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larson, H.J.; Clarke, R.M.; Jarrett, C.; Eckersberger, E.; Levine, Z.; Schulz, W.S.; Paterson, P. Measuring trust in vaccination: A systematic review. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2018, 14, 1599–1609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowak, S.A.; Gidengil, C.A.; Parker, A.M.; Matthews, L.J. Association among trust in health care providers, friends, and family, and vaccine hesitancy. Vaccine 2021, 39, 5737–5740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silver, D.; Kim, Y.; McNeill, E.; Piltch-Loeb, R.; Wang, V.; Abramson, D. Association between COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and trust in the medical profession and public health officials. Prev. Med. 2022, 164, 107311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casiday, R.; Cresswell, T.; Wilson, D.; Panter-Brick, C. A survey of UK parental attitudes to the MMR vaccine and trust in medical authority. Vaccine 2006, 24, 177–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trent, M.; Seale, H.; Chughtai, A.A.; Salmon, D.; MacIntyre, C.R. Trust in government, intention to vaccinate and COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy: A comparative survey of five large cities in the United States, United Kingdom, and Australia. Vaccine 2022, 40, 2498–2505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vasile, M.; Jderu, G.; Cristea, D. Trust in the Public Health System and Seasonal-Influenza Vaccination. Transylvanian Review of Administrative Sciences. 2024, pp. 113–129. Available online: https://rtsa.ro/tras/index.php/tras/article/view/772 (accessed on 17 March 2024). [CrossRef]

- Toró, T.; Székely, I.G.; Kiss, T.; Geambașu, R. Inherent Attitudes or Misplaced Policies? Explaining COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy in Romania. East Eur. Politics-Soc. Cult. 2024, 38, 1093–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Su, Z.; Chen, Z.; Cao, J.; Xu, F. Trust of healthcare workers in vaccines may enhance the public’s willingness to vaccinate. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2022, 18, 2158669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Williamson, L.D.; Tarfa, A. Examining the relationships between trust in providers and information, mistrust, and COVID-19 vaccine concerns, necessity, and intentions. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cristea, D.; Jderu, G.; Petrescu, D.A. Percepția vaccinării și comportamentele legate de vaccinare în România. In Raport și Recomandări; Inscop Research: București, Romania, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Dungaciu, D.; Cristea, D. Barometrul de Securitate a României, National Representative Sociological Survey; LARICS: Bucharest, Romania, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Marinthe, G.; Brown, G.; Cristea, M.; Kutlaca, M. Predicting vaccination hesitancy: The role of basic needs satisfaction and institutional trust. Vaccine 2024, 42, 3592–3600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Ten Threats to Global Health in 2019. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/spotlight/ten-threats-to-global-health-in-2019 (accessed on 29 April 2025).

- Fairhead, J.; Leach, M. Vaccine Anxieties: Global Science, Child Health and Society; Routledge: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Galagali, P.M.; Kinikar, A.A.; Kumar, V.S. Vaccine hesitancy: Obstacles and challenges. Curr. Pediatr. Rep. 2022, 10, 241–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vuolanto, P.; Almeida, A.N.; Anderson, A.; Auvinen, P.; Beja, A.; Bracke, P.; Cardano, M.; Ceuterick, M.; Correia, T.; De Vito, E.; et al. Trust matters: The addressing vaccine hesitancy in Europe study. Scand. J. Public Health 2024, 52, 379–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leblang, D.; Smith, M.D.; Wesselbaum, D. Trust in institutions affects vaccination campaign outcomes. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2024, 118, 720–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aguinaga-Ontoso, I.; Guillen-Aguinaga, S.; Guillen-Aguinaga, L.; Alas-Brun, R.; Guillen-Aguinaga, M.; Onambele, L.; Aguinaga-Ontoso, E.; Rayón-Valpuesta, E.; Guillen-Grima, F. The Impact of COVID-19 on DTP3 Vaccination Coverage in Europe (2012–2023). Vaccines 2024, 13, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luca, C.; Azoicăi, D.; Alexa, I.H.; Vâță, A.; Cucoș, N.; Pascariu, A.; Hunea, I. Cultural Perspectives on Vaccination—An Ethical Dilemma? J. Intercult. Manag. Ethics 2020, 3, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).