Abstract

This conceptual article introduces an alternative perspective on the notion of the urban context for early-career researchers interested in developing academic writing through literary narratives. It brings together two distinct conceptualizations of context. The first is a philosophical approach rooted in interpretive traditions within the humanities and social sciences. The second is a spatial–societal approach commonly adopted in architecture, urban planning, and urban design. By bridging these perspectives, our article aims to enrich interdisciplinary discourse and support more nuanced understandings of urban environments in narrative-based research. The question posed by this conceptual article is given as follows: How can adopt a historical–philosophical contextual approach to literary narratives support the development of non-traditional narrative forms and offer a strategic foundation for early-career researchers? This study adopts a qualitative research approach to examine the role of context in knowledge production. A linear snowball sampling was employed to identify relevant sources, followed by qualitative content analysis to extract key insights. The outcomes integrate perspectives from historians, interpretive philosophers, and urban specialists. The findings provide practical strategies to support early-career researchers in developing historically informed, contextually grounded literary narratives, particularly within non-traditional academic formats.

1. Introduction

In interdisciplinary academic research, issues such as understanding the interrelationship between context, whether based on historical or societally oriented perspectives, and the process of knowledge production and promotion are fundamental [1,2,3,4]. Historical perspectives shed light on the shift in theoretical paradigms, allowing early-career researchers to identify the assumptions, constraints, and biases that shape contemporary discourse [5,6,7,8]. Founding thinkers, including historians and interpretive philosophers such as Dilthey [9,10], Kuhn [11], Tosh [12], and Grimm [13], have provided vital perspectives on interpreting historical contexts. These perspectives represent practical critical grounds that academic researchers can draw upon when writing a literature review section in academic studies. This challenge may reshape knowledge to fit the requirements of their research objectives and problems [14]. Hence, critical engagement with historical context can enhance the quality of theoretical knowledge that derives from contextual significance.

This philosophical orientation to the presence of context’s consequences on literary narratives is particularly significant in academic urban studies research. Specifically, the historical context has a profound impact on most specialists in architecture, urban planning, and urban design disciplines. Early theoretical ideas of urbanists such as Mumford [15] and Jacobs [16] focus on how historical contexts shaped urban areas and changed most societal structures. Similarly, scholars such as Kostof [17] and Shane [18] offer distinct perspectives on the spatial and socio-cultural changes in urban life. In this context, these and other scholars emphasize the impact of historical inquiry in addressing the complexities of interdisciplinary urban studies [19,20,21].

Despite growing recognition of the importance of historical context and contextualization for academic writing, disciplines like learning sciences [22,23], architecture, urban planning, and urban design [24] require practical strategies and guidance for preparing historically and contextually grounded literature reviews [25]. While general guidelines exist, they often fail to address the unique challenges of these fields, such as their inherently interdisciplinary nature, the rapid transformation of urban environments [26], and the difficulty of defining and quantifying urban phenomena [26]. The above methodological gap limits the ability of early-career researchers to construct authentic, high-quality literary narratives in the literature review section. This challenge makes it difficult to integrate interdisciplinary perspectives and to situate their arguments within broader intellectual traditions.

Understanding context-text interplay requires engaging with both historical perspectives and historical inquiry. Historical perspectives provide the interpretive lens through which scholars examine how texts were shaped by and responded to the conditions of their time [27,28]. Historical inquiry refers to the methodological process of reconstructing the past through the critical examination of sources [11,16,29,30]. This process enables an evidence-based understanding of how a text evolved over time and interacted with its historical context [12]. Applied in fields such as urban and social studies, this dual approach enables a nuanced reading of how meaning is produced over time, emphasizing both continuity and transformation. Building on these foundations, this article draws on the perspectives of philosophers, historians, and practitioners to examine how the relationship between context and text has evolved historically and across disciplines.

The purpose of this study was to demonstrate how to integrate historical perspectives and historical inquiry into the interplay between text and context. The aim is to investigate the relationship between context and text, as addressed in the social sciences literature, to improve the quality and depth of literature reviews in the field of urban research. This paper aims to provide practical strategies and guidance for conducting literature reviews, helping early-career researchers in urban research.

To fulfill the aims of this study, the manuscript poses the following main research question: In what ways can a historical–philosophical contextual approach to literary narratives both foster non-traditional forms of narration and provide a strategic framework for early-career researchers? This primary research question is addressed through the three following sub-questions:

- What is the historical significance of context in text production and interpretation, as explored by historians, philosophers, and urban specialists?

- How has the interplay between context and text in theoretical discourse evolved?

- What practical strategies and guidance can be provided to early-career researchers for developing contextually rich, non-traditional literary narratives?

Drawing on historical perspectives and historical inquiry, we employ a qualitative approach that integrates linear snowball sampling within a scoping literature review, directed qualitative content analysis, and historical inquiry methods to explore texts, theories, and ideas. By leveraging the interdisciplinary nature of social sciences, humanities, and urban studies, this research develops practical strategies and guidance to assist early-career researchers in crafting literature reviews that are contextually grounded, methodologically sound, and aligned with their research frameworks.

2. Methodology: Research Approach and Process

This conceptual article employed qualitative research to extract insights from historians, interpretive philosophers, and urban studies specialists. The goal was to provide practical strategies and guidance for early-career researchers in architecture, urban planning, and urban design. The methodology aligns with the findings by using serial sampling techniques to identify sources [31] and applying directed qualitative content analysis to extract insights [32]. The research approach and process are presented in detail in the two following subsections.

2.1. Research Approach

The research approach facilitated a strict evaluation of historical perspectives and their application across the social sciences, humanities, and urban studies. Practical strategies and guidelines concerning the primary purpose of this conceptual article were provided to guide early-career researchers through four steps effectively:

- Key foundational philosophy and historical works were analyzed to uncover the principles and methodologies underpinning historical inquiry. This first step provided theoretical introductory orientation to examine the context–text interplay.

- The study examined how these historical principles inform and enrich the disciplines of architecture, urban planning, and urban design. This practical application ensures that findings are directly relevant to early-career researchers navigating the challenges of interdisciplinary academic writing.

- The following were employed in the form of strategies to identify relevant sources and ensure a comprehensive scope:

- A linear snowball sampling method was employed to trace foundational works and subsequent texts through systematic reference chains [31]. While this technique inherently risks prioritizing well-cited works, bias was mitigated by diversifying initial sources and consulting experts in history, philosophy, and urban studies.

- The Google Scholar database was selected to determine the literature for this current review. The inclusion criteria prioritized sources from classical social sciences, humanities, and urban studies, with a particular emphasis on full-length books and edited volumes. These sources were selected to provide comprehensive and foundational insights. They also support an in-depth exploration of key theoretical and conceptual developments in the field.

- The exclusion criteria comprised peer-reviewed journal articles, book sections, grey literature, non-peer-reviewed publications, websites, and trade journals. These were excluded to maintain a focused scope on historically significant and widely acknowledged academic contributions, ensuring consistency in the depth and type of analysis. However, this exclusion may limit the representation of recent developments and diverse perspectives found in more contemporary or informal sources.

- A keyword strategy was used, merging terms such as “history,” “context,” “text,” “historical analysis,” “historical perspective,” and “historical inquiry” with field-specific terms “urban studies,” “architecture,” “urban planning,” and “urban design.” Boolean operators (e.g., “AND,” “OR,” and “NOT”) were used to refine search results.

- The directed qualitative content analysis was conducted to analyze the selected texts of seventeen scholars in two groups [32]:

- Foundational works explored the role of historical inquiry in shaping knowledge. Key figures included Wilhelm Dilthey [9], Bertrand Russell [33], Hans-Georg Gadamer [34], Thomas Kuhn [11], Michel Foucault [35], and John Tosh [12], among others. These works provided critical insights into the role of historical perspectives, contexts, and analysis in knowledge creation (Table S1 in File S1 of Supplementary Materials).

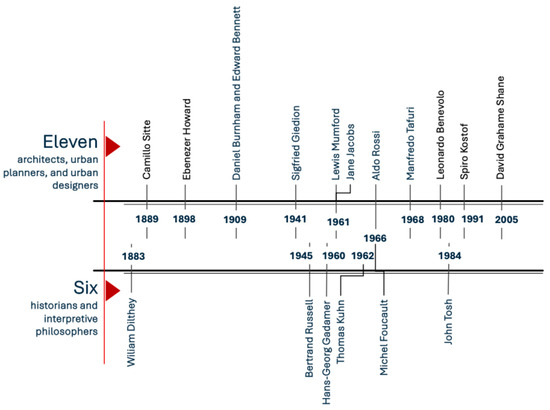

- The second focused on literature on urban specialists: historical perspectives on architecture, urban planning, and urban design were examined in through eleven key texts by scholars such as Camillo Sitte [36], Ebenezer Howard [37], Burnham and Bennett [38], Siegfried Giedion [29], Lewis Mumford [15], Jane Jacobs [16], Aldo Rossi [39], Manfredo Tafuri [30], Leonardo Benevolo [40], Spiro Kostof [17], and David Grahame Shane [18] (Table S2 in File S1 of Supplementary Materials). Figure 1 illustrates the seventeen scholars yielded from inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Figure 1. Seventeen key insights from historians, interpretive philosophers, and urban specialists. The dates indicate when each work was first published. Source: The authors from the history and philosophy literature [9,11,12,33,34,35] and architecture and urban design literature [15,16,17,29,30,34,36,37,38,39,40].

Figure 1. Seventeen key insights from historians, interpretive philosophers, and urban specialists. The dates indicate when each work was first published. Source: The authors from the history and philosophy literature [9,11,12,33,34,35] and architecture and urban design literature [15,16,17,29,30,34,36,37,38,39,40].

2.2. Research Process

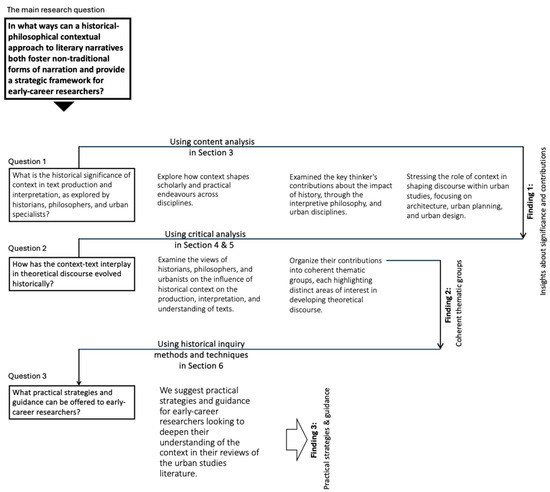

In this conceptual article, we adopted a rational approach to testing the hypothesis that traditional literary narratives and texts relevant to the problems of the status quo share a gap in that they do not follow an authentic context and lack relevance to addressing contemporary problems. Through the sequential process, we ensured consistency by aligning key terms, including the interplay between context and text, context–text production, interdisciplinary insights, and historical methodologies. By framing historical inquiry as an intellectual method and technique, we sought to enhance the quality and depth of literary narratives in urban studies. The results are achieved through four subsections in three separate, interconnected processes (Figure 2):

Figure 2.

Research questions: Four subsections in three separate, interconnected processes. Source: The authors.

- In Section 3, we answer the question: What is the historical significance of context in text production and interpretation, as explored by historians, philosophers, and urban specialists? Using content analysis, we examine how context influences scholarly and practical endeavors across various disciplines. Then, we discuss the key thinker’s contributions to the impact of history through interpretive philosophy and urban disciplines, emphasizing the role of context in shaping discourse within urban studies, with a focus on architecture, urban planning, and urban design.

- In Section 4 and Section 5, we answer the question, “How has the context–text interplay in theoretical discourse evolved historically?” Using critical analysis, we examine the views of historians, interpretive philosophers, and urbanists on the influence of historical context on the production, interpretation, and understanding of texts. We then organize their contributions into coherent thematic groups, each highlighting distinct areas of interest in the development of theoretical discourse.

- In Section 6, we employ historical inquiry methods and techniques, drawing on insights from prominent historians, philosophers, and urbanists, to answer the final question: What practical strategies and guidance can be offered to early-career researchers? Accordingly, to achieve our purpose, we suggest practical strategies and advice for early-career researchers looking to deepen their understanding of the context in their reviews of the urban studies literature).

3. The Historical Significance of Context in Text Production and Interpretation

This section presents the results of answering the question that examines the significance of historical context on the production, interpretation, and understanding of texts. Drawing on historical inquiry and analysis, the results shed light on how context shapes scholarly and practical efforts across the literary narrative of diverse literatures in multiple disciplines. This section includes two levels. The first presents contributions from six interpretive historians and interpretive philosophers, with a focus on the social sciences and humanities. The second presents contributions from eleven urbanists, concentrating on architecture, urban planning, and urban design.

3.1. Contributions of Six Historians and Interpretive Philosophers

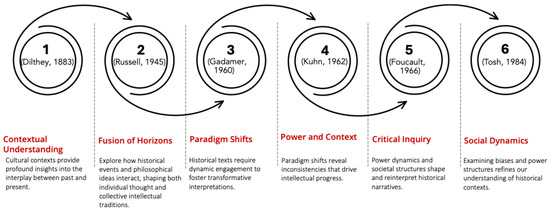

This subsection examines the contributions of six historians and interpretive philosophers, focusing on how various methodological approaches—such as hermeneutics, paradigm analysis, and critical historiography—illuminate the interplay between historical systems of meaning, power structures, and textual interpretation. These methodologies serve as crucial frameworks for understanding how texts are influenced by and respond to their historical contexts, as illustrated in Figure 3 (refer also to Table S3 in File S2 of Supplementary Materials).

Figure 3.

Contributions of six historians and interpretive philosophers. The dates indicate when each work was first published. Source: The authors based on literature [9,11,12,33,34,35].

- Introducing “hermeneutics” to analyze historical contexts to demonstrate how cultural contexts shape textual meaning [9].

- Engaging with inherent uncertainties while pinpointing pivotal moments within historical narratives [41,42].

- Developing a hermeneutic methodology used in arguing for interpreting texts within their historical traditions [34].

- Intellectual paradigm shifts are highlighted as reflections of historical context, offering a basis for re-evaluating knowledge systems [11].

- Developing archaeological methods to analyze knowledge systems, revealing how power dynamics influence textual meaning [35].

- Providing a comprehensive framework for critical historiography by challenging objective narratives and exposing biases in historical texts [12].

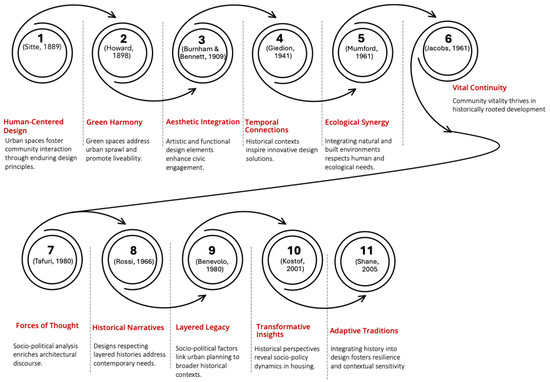

3.2. Contributions of Eleven Specialists in Architecture, Urban Planning, and Urban Design

The findings of these contributions highlight the critical role of historical inquiry, which shapes two types of analytical and critical historical thinking: theoretical perspectives and practical applications within these fields. This subsection explores the contributions of eleven specialists in architecture, urban planning, and urban design. These eleven specialists conceptualize the architectural and urban forms of the cities as “living historical texts” intricately linked to human experience and cultural memory. Figure 4 illustrates how historical moments, societal transformations, and cultural traditions have shaped their approaches, influencing both theoretical frameworks and practical methodologies (see Table S4 in File S2 of the Supplementary Materials).

Figure 4.

Eleven key insights from architecture, urban planning, and urban design. The dates indicate when each work was first published. Source: The authors based on the literature [15,16,17,18,29,30,36,37,38,39,40].

- Examining medieval and Baroque designs highlights the enduring significance of human-scale urban spaces and aesthetic considerations in promoting community interaction and livability in contemporary cities [36].

- Blending urban and rural elements while prioritizing green spaces offers a transformative approach to addressing urban sprawl and fostering healthier, more balanced living environments [37].

- Incorporating aesthetic principles, such as grand boulevards and expansive parks, into systematic urban planning enhances civic attention and enriches public life [38].

- Emphasizing the interplay of space, time, and architecture underscores the importance of engaging with historical contexts to inform modern design solutions [29].

- Integrating constructed and natural environments provides a development framework that respects ecological systems and human needs [15].

- Preserving historic neighborhoods and supporting organic urban development ensures community vitality, historical continuity, and a human-centered approach to city planning [16].

- Examining the societal factors that influence architectural theories enhances their relevance to modern practice and expands the dialogue within architecture [30].

- Promoting continuity in historical and architectural principles offers a counterpoint to fragmented modern urban approaches, encouraging designs that respect cities’ layered history while addressing contemporary challenges [39].

- Understanding the socio-economic, political, and cultural factors influencing city growth bridges architectural history with broader historical narratives, enriching urban studies [40].

- Drawing on historical insights shapes urban design practices responsive to evolving urban challenges, fostering historically informed and adaptive strategies [17].

- Adapting historical urban models to contemporary issues blends historical awareness with innovation, creating contextually sensitive urban environments [18].

4. Uncovering History: The Critical Role of Context and Perspective

Understanding the complexities of history requires research that is grounded in its historical context and enriched by interdisciplinary perspectives. This section highlights the importance of uncovering the contextual factors that shape events, moving beyond simplistic narratives to engage in a nuanced analysis of historical processes. By addressing common pitfalls—such as neglecting subtle historical dimensions, misinterpreting past events, or applying anachronistic frameworks—researchers can gain a deeper understanding of history’s relevance to contemporary challenges in urban studies and related fields. Critically analyzing diverse historical perspectives provides insights into the interplay between historical context and knowledge production, highlighting how these perspectives inform contemporary architectural practices, urban planning, and urban design. This approach emphasizes the significance of critical historical analysis, which investigates past events and situates them within broader intellectual traditions and shifting paradigms.

The following subsections examine the contributions of foundational thinkers in history, interpretive philosophy, and urban disciplines. These contributions highlight the roles of context, perspective, and interdisciplinary inquiry in shaping the discourse within urban studies, with a focus on architecture, urban planning, and urban design.

4.1. Insights from Historians and Interpretive Philosophers

This subsection highlights the significance and contributions of historians’ and interpretive philosophers’ findings in two systematic efforts. First, the findings of relevance emphasize the importance of understanding historical texts as products of their specific contexts, dynamically shaped by social, cultural, and political factors. Scholars such as Wilhelm Dilthey [9], Bertrand Russell [33], Hans-Georg Gadamer [34], Thomas Kuhn [11], Michel Foucault [35], and John Tosh [12] have significantly advanced our understanding of how historical analysis influences knowledge creation across the social sciences, humanities, and urban studies. Second, based on the findings from the examination of specific literary works, it is clear that their contributions offer an innovative perspective for critically engaging with contemporary knowledge and situating it within the broader context of intellectual traditions.

The results of this subsection begin with the assertion that history requires being understood by researchers as more than just a literary narrative that follows emerging circumstances and successive historical events. Instead, this understanding requires a complex engagement with what has passed. It also involves the cognitive tracing of the contexts that shape and determine those events. These contexts are influenced by the surrounding circumstances and by the varying perspectives of thinkers. Such perspectives differ according to the multiplicity of specializations. In addition, the results revealed the inevitability of following a dynamic interpretation of history, one that changes according to the basic assumptions, contradictions, and transformative ideas embedded in the historical narratives of each theorist, as dictated by their specialty.

Wilhelm Dilthey’s [9] hermeneutics introduced the concept of “historical reason”—the idea that historical and cultural contexts inherently shape human understanding and reason. Dilthey [9] argued that the human sciences should focus on interpreting human life through these frameworks, distinguishing them from the natural sciences, which seek universal, ahistorical laws. In this vein, in his book Introduction to the Human Sciences (first published in 1883), Dilthey [9] focuses on creating a theoretical and methodological foundation for the human sciences, which is distinct from the natural sciences, by emphasizing the role of understanding (Verstehen) in interpreting human experiences and expressions within their historical and cultural contexts.

Building on the contextual interpretation highlighted by Dilthey [9], Bertrand Russell [33] expands on these ideas by emphasizing the crucial importance of situating historical events within their unique contexts. His 1945 work, A History of Western Philosophy [42] is widely regarded as a foundational text in the history and philosophy of Western thought. In this book, Russell [33] illustrates how situating events in context can enhance our understanding of how knowledge is produced at both the individual and societal levels. His method invites deeper philosophical inquiry, calls attention to the uncertainty that inevitably surrounds historical narratives, and prompts readers to examine key turning points within those narratives.

Hans-Georg Gadamer, in his book Truth and Method [34], introduced the concept of the ‘fusion of horizons’ to describe the transformative potential of interactions between interpreters and historical contexts. This approach re-examines established narratives by bridging temporal and cultural divides, offering new perspectives that challenge and deepen traditional interpretations.

Thomas Kuhn’s book, The Structure of Scientific Revolutions [11], initially published in 1962, introduced the concept of paradigm shifts, which transformed the scholarly understanding of scientific progress. Kuhn’s analysis within the domains of the history and philosophy of science demonstrates that paradigm shifts in scientific thought occur when existing theoretical models fail to account for anomalous phenomena. Such epistemological crises lead to the creation of new conceptual frameworks, known as paradigms, which fundamentally alter the scientific community’s understanding of the real world.

Similarly, Michel Foucault’s The Order of Things [35], first published in 1966, investigates the historical epistemes that structure human knowledge across different periods. His analysis reveals how these systems of thought establish the foundational conditions that shape contemporary intellectual frameworks. Foucault argues that what is considered ‘knowledge’ in any given era is not fixed or universal but is defined by shifting epistemic conditions—what he calls ‘epistemes’—that govern how people understand the world. By critically analyzing these hidden contexts, Foucault highlights how power and discourse shape the production of knowledge and the organization of society. His work provides a valuable lens for rethinking established ideas and uncovering the often-overlooked forces that shape human thought and culture.

John Tosh’s book The Pursuit of History [12] was first published in 1984. It presents a compelling argument for the significance of critical historical inquiry. This contribution is especially evident when addressing challenging issues and understanding the role of power. Tosh [12] argues that, to understand how power, social structures, and historical events shape one another, we must combine solid historical research with a deep understanding of context. This approach enables the researcher to seek answers and gain a deeper understanding of the broader context.

Tosh [12] demonstrates that history is not merely about recounting what happened—it is about uncovering the deeper forces that shape how societies evolve and change. For those new to fields like urban studies or architecture, adopting this kind of thinking helps them look beyond the surface and explore how power, culture, and history continue to shape our world today.

4.2. Insights from Architects, Urban Planners, and Urban Designers

Understanding historical context is essential for developing insightful literature reviews in architecture, urban planning, and urban design research. This involves tracing expert perspectives and examining the historical forces that have shaped urban cities over time. This approach grounds contemporary research in a deeper awareness of past influences. This tracing is mainly concerned with understanding the historical underpinnings of intellectual paradigms, including the theories, trends, schools, and movements that have informed urban studies. It provides the theoretical basis for writing texts relevant to the considerations that shape academic urban research. Contemporary challenges and solutions are deeply rooted in history. They can be better understood by examining and uncovering the historical and societal contexts that preceded urban theory and practice. These contexts include social, economic, political, and technological dimensions.

Examining history in this way helps build more robust theoretical frameworks and provides valuable practical insights into urban planning research. Understanding these historical influences provides early-career researchers with a solid foundation, enabling them to create richer and more meaningful literature reviews. Insights from specialists such as architects, urban planners, and urban designers can be extracted from their professional work and integrated into contemporary research. These insights contribute to strengthening the resulting narratives. They are derived through the examination of the historical foundations of practice, linking theoretical knowledge with practical applications in the field.

The work of urban theorists such as Camillo Sitte [36], Ebenezer Howard [37], Daniel Burnham and Edward Bennett [38], and Lewis Mumford [15] emphasizes the role of historical analysis in urban planning. Sitte’s [36] insights into medieval and Baroque urban principles provide a valuable historical perspective. They help illuminate the evolution and context of urban planning concepts. Such insights highlight the continued relevance of these ideas in contemporary urban discourse. His critique of the rigid geometric layouts seen in modern cities was one of the first genuinely critical reflections on the benefits of organic urban development, which, he argued, fosters human interaction and participation. In addition, his understanding of the aesthetic and social significance of public spaces offers a strong perspective on modern urban planning strategies. Sitte’s [36] insights encourage city planners to focus on the urban environments that promote community interaction. His insights, drawn from his influential work City Planning According to Artistic Principles [36], first published in 1889, emphasize the essential role of historical city forms in contemporary urban design.

In Tomorrow: A Peaceful Path to Real Reform, Howard [37] proposed innovative solutions to urban dilemmas by integrating green spaces into city planning—his concept of garden cities and green belts desired to balance urban growth with environmental sustainability. Before World War II, the Garden City movement influenced urban planning products, especially in American cities and abroad, emphasizing the importance of preventing unchecked urban sprawl while fostering human and environmental well-being. Howard’s work exemplifies the power of historical thought in contemporary urbanism, highlighting the lasting impact of historical ideas on modern planning practices.

Similarly, the City Beautiful movement, as articulated by Burnham and Bennett in the Plan of Chicago [38], published in 1909, emphasizes the integration of aesthetics with functionality in urban design. The city combines beauty with functionality as a cohesive blend of grand boulevards, expansive parks, and efficient transportation systems. Their perspective remains widely influential in urban planning, emphasizing aesthetically pleasing and functional public spaces that contribute to the creation of beautiful cities and vibrant communities.

In his 1968 book The City in History, Lewis Mumford [15] emphasizes the intricate interplay between social, economic, and environmental forces. He presents a historical perspective on urban evolution and underlines the need for balance—harmonizing built environments with the natural world—Mumford’s perspective focuses on the analytical work on ancient Greek cities. Mumford’s insights into the comprehensive analyses of urban spaces throughout history have provided the theoretical insights used by scholars in their theoretical literature. His insights have often been turned into practical guidelines for urban planners. Although his vision for achieving a balance between the built and natural environments is inspiring in both theory and practical application, it must be viewed within the framework of urban planning practices on the ground and considering the requirements of each spatial and societal context.

Additionally, despite his focus on ancient Greek cities offering strong and newly learned lessons, his insights do not adapt to each urban circumstance. It may not fully reflect the variety of urban experiences across different cultures and eras. A well-rounded understanding of Mumford’s work should acknowledge its strengths and limitations. Early-career researchers, while drawing inspiration from Mumford’s emphasis on balance, should critically engage with these nuances to enhance the relevance and effectiveness of their research.

Urban theorists such as Giedion [29], Jacobs [16], Benevolo [40], Tafuri [30], and Shane [18] have made seminal contributions to the field. Their previous literature has emphasized the historical forces that influence cities’ development. Their work, though diverse in approach, underscores the importance of considering past contexts to inform contemporary urban planning and design practices. Most of their books published between 1940 and 2005 argue that planners and designers can better address contemporary challenges by studying past urban forms, cultural contexts, and societal changes. This article depends on historical inquiry to obtain insights from scholars’ works. Their works collectively highlight the importance of historical awareness in creating functional and meaningful cities, offering timeless insights into the relationship between the built environment and social evolution.

Giedion [29] explores the interplay between space, time, and architecture, offering valuable insights into how architecture and urban design reflect broader societal and technological shifts. In The Death and Life of Great American Cities, Jacobs [16] critiques mid-20th-century urban planning practices that disregarded historical contexts, advocating for planning that integrates community needs and values instead. Benevolo’s [40] groundbreaking book, The History of the City, published in 1980, encompasses a range of historical periods and geographical contexts, enabling him to discuss urban development from antiquity to the present. His work demonstrates the impact of historical context on urban growth through technological, economic, political, and cultural developments across these periods. Tafuri [30] did the same in his Theories and History of Architecture published in the same year. Notably, the latter expanded his study of history by highlighting the significance of architectural theory in shaping the interaction between societal changes and architectural practices. This coherence fostered a deeper engagement with history, enabling a more nuanced understanding of the forces that shaped urban environments.

Building on the same perspective that sees context as a key player in the history of cities, but with a different approach, Rossi [39] argues in his book The Architecture of the City that the city is made up of historical layers left over from time and that it is this succession of layers that provides an inspiring space for understanding why the city has been transformed into the shape it is today, and then building on that to see where those layers lead it to reveal its potential for the future.

Similarly, in The City Shaped: Urban Patterns and Meanings Through History, Kostof [17] explores how historical analysis can transform urban design. He examines how cities have evolved, demonstrating how past urban forms—shaped by diverse cultural, social, and technological contexts—can provide valuable insights into contemporary urban practice. By examining the layers of history embedded in the urban fabric, Kostof [17] prompts researchers to consider how historical patterns influence modern cities and inform their future development.

Regarding the significance of historical perspectives in housing studies, Keith Jacobs [8] highlights the impacts of past policies and social conditions that continue to impact today’s housing landscape. By examining these past influences, Jacobs [8] believes that we can gain a better understanding of the socio-political forces that have shaped housing practices over time. Jacobs’ [8] integration of historical methodologies offers profound insights into the socio-political dynamics that have shaped housing practices, enriching the field’s analytical depth and relevance.

The previous attempts that have similarly focused on historical perspectives with different approaches and according to multiple requirements, Shane [18] argues in his literature Recombinant Urbanism that historical precedents can inform the contemporary urban design to create more resilient and adaptable cities by successfully making historical urban models more adaptable to contemporary challenges. Hence, “reconstructive urbanism” addresses the interconnected relationships between city elements because it combines foundations drawn from history, theory, and practice. Therefore, it has provided valuable knowledge that has enabled researchers to understand how current and future designs can benefit from solutions from the past.

These diverse perspectives highlight the significance of historical inquiry and analysis in shaping theoretical and practical urban planning and design practices throughout history, albeit with limited examples. This review means that integrating historical investigation and analysis into urban research is essential. It enables urban planners and designers to write valuable literary narratives. These narratives are grounded in a thorough understanding of their historical context. Continuing to explore the evolution of the interaction between context and text in theoretical discourse, the following section synthesizes the contributions of various theorists. It reveals thematic clusters of distinct areas of interest within the development of historical and theoretical discourse. These clusters may offer a clearer and more cohesive understanding for developing strategies and practical guidelines for early-career researchers.

5. The Context–Text Interplay in Theoretical Discourse: A Historical Evolution

This finding challenges insights from 16 authors on uncovering history, highlighting the influence of historical inquiry and analysis on engaging with historical texts and contexts. It demonstrates how historians, interpretive philosophers, and subject-matter specialists contribute to a broader understanding of the historical inquiry framework. Their contributions are organized into eight thematic groups, each shedding light on distinct areas of interest within the evolution of theoretical discourse.

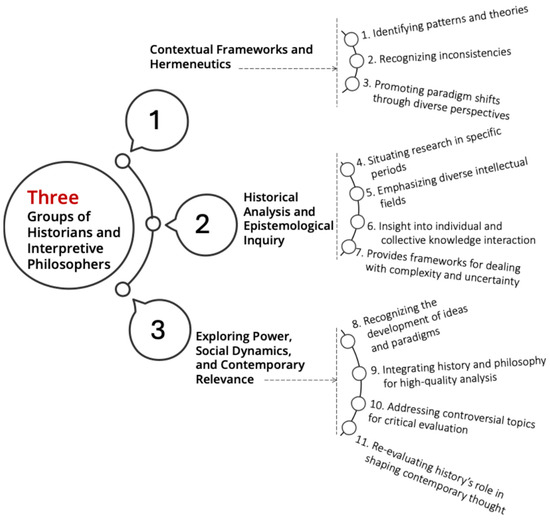

5.1. Three Groups of Historians and Interpretive Philosophers

Three distinct, complementary groups summarize the insights of six authors by classifying them into three distinct, complementary groups. These three groups of historians and interpretive philosophers have supported these scholars’ emphasis on the contextual approach. They have transformed insights into contextual frameworks and hermeneutics, as well as historical analysis and inquiry and epistemological inquiry. They also explore power, social dynamics, and contemporary relevance.

5.1.1. Group 1: Contextual Frameworks and Hermeneutics

The first integration group shows the critical role of historical inquiry concerning contextual frameworks and hermeneutics (Figure 5). Scholars such as Dilthey [9] and Gadamer [34] highlight the necessity of interpreting historical events within their broader contexts. According to the works of its theorists, this group aims to focus on writing literature that actively engages with historical texts and promotes transformative interpretations through the integration and diversity of perspectives.

Figure 5.

Three groups of historians and interpretive philosophers with key aspects and priorities. Source: The authors.

Dilthey [9] and Gadamer [34] emphasized the significance of the interplay between history and philosophy, as well as their shared connection to scientific inquiry. Building on the interpretation above, this group, about the concept of hermeneutics, identifies urban patterns and theories, recognizes inconsistencies, and prompts paradigm shifts. All these aspects are paramount for literary narratives in urban studies.

Moreover, in this group, alternative viewpoints are a prominent theme in the authors’ contributions. These were influenced by the need to deepen understandings of historical events, circumstances, and meanings to advance knowledge based on critical historical analysis. Building on the three pillars of this group, the significance of historical inquiry and analysis lies in identifying contradictions and gaps in these perspectives. This process leads to insightful discoveries that strengthen and enhance the narrative’s effectiveness. It also plays a crucial role in revealing new insights.

5.1.2. Group 2: Historical Analysis and Epistemological Inquiry

Building on the study of the past, the second group of historical analysis and epistemological inquiry attempts to develop an understanding of the present challenges, investigating the historical power and social dynamics of that interplay. It also examines how power and society have shaped our world, offering crucial insights into today’s challenges. This group builds Russell’s [33] ideas’ first and second key aspects, emphasizing the importance of situating historical research in specific periods and his call for comprehensive investigations through accepting diversity in intellectual fields.

The group’s focus on his thought alone underscores the crucial role of historical inquiry in analyzing power dynamics and social structures, as well as their contemporary relevance. Thus, the third and fourth key aspects, which focus solely on his thought, underscore the crucial role of historical inquiry in analyzing power dynamics and social structures, as well as their contemporary relevance. Historical inquiry is a tool for examining uncertainty and complexity, providing scholars with valuable frameworks for deeper inquiry. This group demonstrates two critical pieces of knowledge: individual and collective. Their interaction fosters intellectually rich discussions that drive essential breakthroughs in the rest of knowledge.

5.1.3. Group 3: Power, Social Dynamics, and Contemporary Relevance

Based on the historical perspectives of the three authors of this group, the results focus on the relations between power, social dynamics, and contemporary relevance. The authors in this group focused on the issue of hidden conflicts and contexts. This perspective highlights the extent to which his ideas contribute to understanding the effects of these interrelations on narratives from a historical perspective. The three authors in this group, Kuhn [11], Foucault [35], and Tosh [12], respectively, support an approach based on the importance of understanding context to enhance the interaction between past and present knowledge systems. The priority focuses on recognizing that the development of ideas and paradigms is the basis of any critical analysis in literature review. It is linked to acknowledging how paradigmatic shifts reveal contradictions and enrich scholarly inquiry. The second priority stresses the importance of integrating history and philosophy, as combining these fields ensures more thorough and high-quality analysis in literary research. The third priority of this group emphasizes the importance of being mindful when writing any literary narrative that addresses controversial topics, as they facilitate critical evaluations of historical events.

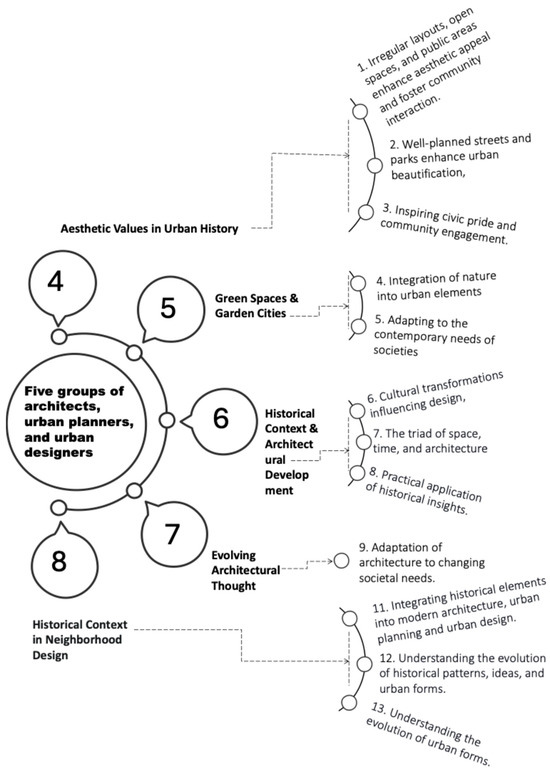

5.2. Five Groups of Architects, Urban Planners, and Urban Designers

This subsection contains an important finding in understanding the contributions of architects, urban planners, and urban designers to understand the historical context of urban development and architecture. The discussion is organized into five groups, highlighting how these professionals integrate historical analysis with innovative design principles. These five groups begin with organic development and aesthetic values, including green spaces and the Garden City movement, historical context and architectural development, architectural thought and the compact city, and neighborhood design and urban history. All findings contribute to a deeper understanding of historical inquiry in urban planning and architecture. It ends with the key aspects of each group.

5.2.1. Group 4: Valuing Organic Development and Aesthetic Values in Urban History

The first group includes the views and visions of planners such as Camillo Sitte [36], Daniel Burnham [38], and Edward H. Bennett [38], whose contributions were characterized by their reliance on historical, interpretive, and critical analysis. A central theme is the significance of aesthetic principles in creating artistic principles that are visually appealing and human-centered in city planning (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Five groups of architects, urban planners, and urban designers with key aspects. Source: The authors.

This group emphasizes two main aspects. The results show that the first key aspect highlights how irregular street layouts, open spaces, and public areas contribute not only to aesthetic appeal but also to fostering community interaction. The emphasis here is on how organic, less rigid planning approaches can enhance the character of urban spaces. The second aspect emphasizes the importance of well-planned urban streets and city parks. These elements address urban beautification. They can inspire civic pride and community engagement. By doing so, they make cities more livable and appealing.

5.2.2. Group 5: Integration of Green Spaces and the Garden City Movement

This group builds on the insights of Ebenezer Howard [37] and Lewis Mumford [15]. It explores historical inquiry that integrate green spaces according to their importance in shaping cities into urban planning principles by integrating natural environments and buildings. This group examines the impact of historical context on the quality of literary narratives in modern urban studies. This group highlights two key aspects: new ideas about urban belts, as exemplified by the concept of garden cities, and how to integrate them into essential urban elements. Secondly, this axis supports the first and adds to it the necessity of adapting paradigm shifts of city planning to be evolving societal needs.

5.2.3. Group 6: Historical Context and Architectural Development

The two insights of Sigfried Giedion [29] and Manfredo Tafuri [30] established the primary aspects of this group. It integrates historical inquiry and analysis into architectural thought and the interplay between architecture, cultural contexts, and societal transformations. This group highlights two key aspects: enriching theorizing by revealing how cultural transformations and historical contexts shape urban design practices and focusing on the triad of relationships between space, time, and architecture. Secondly, this highlights the practical application of historical insights, demonstrating that re-evaluating past urban planning and design practices yields effective contemporary strategies.

5.2.4. Group 7: Evolving Architectural Thought and Its Impact on the City

This group builds on Benevolo’s [40] work, which bases its analysis on historical development, emphasizing his fundamental insight into the importance of integrating social, economic, political, and cultural influences from a historical perspective. Tracing the synthesis of historical data over time helps identify relevant issues and themes in urban design, providing supporting insights for the future of planning and design. This group focuses on the practical value of historical inquiry in shaping urban and human-centered contexts. Benevolo’s [40] synthesis of historical data reveals ongoing themes and transformations in urban design, offering valuable insights for contemporary urban planning. The core aspect of this group can be summarized as follows: architectural thought evolves in response to societal and human-centered changes.

5.2.5. Group 8: Historical Context in Neighborhood Design and Urban History

This group builds on the insights of Aldo Rossi [39], Jane Jacobs [16], and Spiro Kostof [17]. It highlights the significance of historical context in shaping neighborhood design and urban development. It collectively advocates using historical insights to create meaningful, contextually grounded urban designs. Some scholars emphasize the importance of contextual frameworks in urban studies. This group highlights three key aspects: Analyzing and integrating historical elements into modern architecture and planning through urban history.

Secondly, this approach provides valuable insights into architecture, planning, and historical analysis in residential neighborhood design, highlighting the importance of historical context. Thirdly, the evolution of urban forms, as analyzed through historical study and the interplay between history, theory, and practice, supports an understanding of the design principles. Furthermore, this group refers to the historical examples’ role in shaping urban form and enhancing current and future urban planning and design.

6. Practical Strategies and Guidance for Early-Career Researchers

According to the brief review above, the key findings present ten practical strategies organized into two parts and nine guides divided into two groups. These resources are designed for early-career researchers aiming to enhance their contextual understanding in urban studies literature reviews. These ten strategies and nine guidelines draw on the perspectives and insights of prominent historians, interpretive philosophers, and urban specialists, highlighting the role of historical research in understanding the evolution of knowledge transformations and building historical investigative analysis grounded in the complex interaction between context and text.

6.1. Practical Strategies from Key Scholars of Historians and Interpretive Philosophers

Our results shed new light on five key strategies based on insights gained from tracing the perspectives of historians and interpretive philosophers across multiple disciplines in the social sciences and humanities. The strategies presented in this study provide a foundation for early-career researchers to develop a critical perspective that deeply engages with historical contexts and their relationship to literary texts. The historical perspective adopted by the current study enables researchers to gain valuable insights by understanding the nature of historical knowledge development from multiple perspectives, including, for example, the influence of power and authority, as well as the social and cultural effects of urbanization. Several points of convergence emerged from the works of prominent scholars, who emphasized the importance of dealing with historical events within their specific cultural and social contexts. This understanding and emphasis reinforce the idea that knowledge is constantly changing over time. The most relevant aspect of our study is identifying contradictions in historical narratives and how they can be used to formulate new theories for change, as some pioneers did. This insight includes determining the role of power in shaping knowledge and narratives, as highlighted by Foucault [35] and Tosh [12].

Additionally, Gadamer [34] and Foucault’s [35] insights highlight the significance of employing multiple transformative analyses throughout history. This significance arises from the instrumental role of such analyses in re-evaluating established narratives and interpretations, especially when examining their interrelationships and implications for contemporary social and cultural changes. They argue that this approach is crucial for maintaining relevance and up-to-date historical analysis.

Interpretive philosophers such as Dilthey [9] and Gadamer [34] have theorized about the social and cultural influences on ongoing urban change. Their theories have provided practical insights into the development of social, urban, and human structures. Dilthey’s [9] concept of the “lifeworld” emphasized the lived experiences of people in urban areas. Similarly, Gadamer [34] described how urban space formation, based on the city planning approach, influences the cultural development of metropolitan cities. In conclusion, this visionary framework highlights the importance of historical inquiry as a crucial tool for understanding the dynamic and interconnected nature of history.

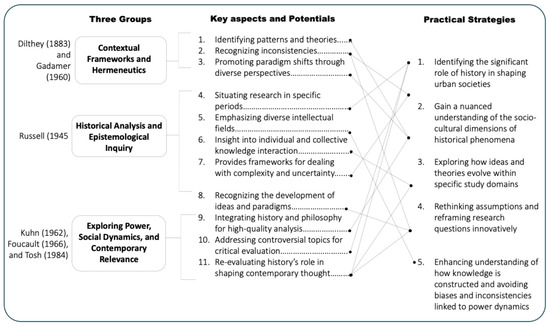

From the results of Section Five in this manuscript on historical evolution, which emphasizes the role of context–text interplay in theoretical discourse, we identified three groups of interest, focusing on 11 key aspects and priorities derived from the insights of various thinkers. These insights deepened our understanding of the complex interactions between the social, cultural, and political forces shaping historical events. As a result, five practical strategies emerged: tracing societal influences (social, cultural, and other factors), contextual and cultural interpretation, paradigmatic shifts in theoretical frameworks, transformative (critical) analysis, and examining the dynamics of power and authority in knowledge construction.

The 11 key aspects and potentials produced by the three groups of the context–text interplay in theoretical discourse contributed to the development of these five practical strategies (see also Table S5 in File S3 of the Supplementary Materials)

- Identifying the significant role of history in shaping urban societies [11,12,34,42].

- Gain a nuanced understanding of the socio-cultural dimensions of historical phenomena [9,34,42].

- Exploring how ideas and theories grow within specific study domains [9,11,12,34,35,42].

- Rethinking assumptions and reframing research questions innovatively [11,12,35,42].

- Enhancing understanding of how knowledge is constructed and avoiding biases and inconsistencies associated with power dynamics [9,11,34,35,42] (Figure 7).

Figure 7. Five practical strategies were derived from 11 key aspects across three context–text groups. The dates indicate when each work was first published. Source: The authors based on literature [9,10,12,33,34,35].

Figure 7. Five practical strategies were derived from 11 key aspects across three context–text groups. The dates indicate when each work was first published. Source: The authors based on literature [9,10,12,33,34,35].

6.2. Practical Strategies from Key Scholars of Specialists

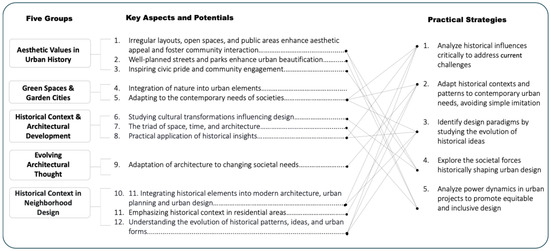

Urban scholars and practitioners emphasize that history serves as a backdrop to contemporary events and is undoubtedly a dynamic force shaping architecture, urban planning, and urban design products. In these strategies, historical inquiry and analysis techniques enable early-career researchers to challenge existing assumptions and create texts with literary narratives that provide a deeper understanding of historical development. As such, historical research becomes essential for architects, urban planners, and city designers, as it guides them in integrating historical and societal contexts into their work.

The theoretical and practical contributions of scholars such as Benevolo [40], Giedion [29], Howard [37], Jacobs [16], Kostof [17], Mumford [15], Rossi [39], Shane [18], Sitte [36], and Tafuri [30] add a fundamental dimension to the value of historical inquiry in terms of enhancing the understanding and application of practices within these fields more explicitly and expressively.

Six pivotal themes offer practical strategies from leading scholars: the role of history, historical phenomena, paradigm shifts and changes, transformative analysis, and the dynamics of power and authority. These themes illustrate how engaging with historical context can enhance both theoretical and practical perspectives in architecture, urban planning, and urban design. The extracted strategies are summarized in five practical strategies (Figure 8 and Table S6 in File S3 of the Supplementary Materials).

Figure 8.

Five practical strategies were derived from 11 key aspects across five context–text groups. The authors based their work on the literature [15,16,17,29,30,36,37,38,39,40,41,42].

- Analyze historical influences critically to address recent challenges [15,17,36,39].

- Adapt historical contexts and patterns to contemporary urban needs, avoiding simple imitation [16,17,18,29,40].

- Identify design paradigms by studying the evolution of historical ideas [15,16,18,40,41].

- Explore the societal forces historically shaping urban design [16,17,22,29,30,39,42].

- Analyze power dynamics in urban projects to promote equitable and inclusive design [15,16,17,29,30,39].

6.3. Final Practical Guidance for Writing with Historical Perspectives

The previous strategies represent a logical introduction that enables us to discover paradigmatic intellectual shifts and address power dynamics within urban discourse at the level of architecture, urban planning, and urban design. The following two subsections guide early-career researchers in critically engaging with historical contexts. This engagement can enhance their ability to present a literary narrative that extends beyond traditional narratives. Early-career researchers can demonstrate intellectual originality by tracing previous contexts and reflecting on contemporary realities. To maximize the value of the last eight groups, alongside the practical strategies for minimizing conceptual overlap and clarifying distinct contributions, the following insights can be organized more effectively. These insights may be restructured into two main categories of guidance. The first category focuses on broad historical analysis. The second category emphasizes the practical application of historical insights in the fields of urban planning and architecture.

6.3.1. Guidance 1: Historical Inquiry and Critical Analysis

The first category of these guidelines accentuates the understanding of history as a distinct and worthy discipline. Furthermore, researchers should acknowledge that history broadly influences the examination and production of knowledge, as well as the construction of literary narratives that align with contemporary reality. This category carefully examines the basis and importance of critically evaluating past knowledge. It requires tools and methods for examining how historical knowledge develops, what methods and ways enable us to understand it, and then the means of applying it. This approach is grounded in systematic analysis of foundational and contemporary literature. Relevant case studies are also examined to support theoretical development and empirical application. The current category guidelines encourage researchers to investigate the causes and contexts behind the emergence of key ideas. They also promote identifying contradictions or inconsistencies in the data. Additionally, they support tracing patterns of transformation over time. Particular attention should be paid to pivotal moments of change and the factors behind them. This category includes four key approaches to critical historical analysis in terms of adopting and maintaining considerations of the interaction between context and text:

- Treating history as a distinct discourse subject to critical analysis.

- Examining ancient texts by focusing on the perspectives of early pioneers: reading texts within the context.

- Examining ancient texts by examining the impact of power and social dynamics on the formation of literary narratives: reading texts through the interaction between individual and collective knowledge.

- Re-evaluating the quality of current literary narratives by relying on the results of critical analysis.

6.3.2. Guidance 2: Historical Context in Urban Studies and Architecture

This category enables researchers to study the historical evolution of academic discourse, extracting the lessons learned and principles compatible with current conditions. This category focuses on the interaction between theoretical frameworks that include urban paradigms across their historical contexts. All the above helps trace the development of urban academic discourse from the perspective of integrating historical principles into contemporary urban practices, considering the impact of this integration on the interpretation of past and current texts. This category includes the five following topics:

- Understanding historical contexts as dynamic forces that inspire contemporary architecture and urban planning.

- Learning from historical, intellectual developments to extract principles for creating urban contexts aligned with current conditions.

- Exploring the relationship between paradigms and historical contexts to understand the evolution of urban thought.

- Integrating historical principles into architecture, urban planning, and design highlights their importance in shaping and understanding built environments.

- Investigating the influence of social structures on living spaces and daily experiences.

Based on structuring historical inquiry and analysis, the five main topics above offer an innovative contribution to two distinct yet complementary focuses tailored to the needs of early-career researchers in urban studies and architecture:

- Promoting critical historical analysis to challenge entrenched narratives and power dynamics, fostering intellectual growth and innovation.

- Craft compelling recent narratives informed by historical perspectives, building on the power of historical context to deepen meaning and enhance literary narrative.

The nine guidelines finalized in the previous two categories help early-career researchers improve their writing of literary narratives by emphasizing historical and contextual knowledge. Concentrating on both theoretical foundations and practical applications, these guidelines enable scholars to critically analyze historical sources. These two categories recognize meaningful shifts in urban thought and apply the lessons learned from this analysis to current urban challenges. Ultimately, they enrich their research assistance and enhance their learning of writing literary narratives in academic research.

7. Conclusions

This article is based on the hypothesis that traditional literary narratives and texts written by some early-career researchers in literature reviews share a gap in that they do not follow an authentic context and lack relevance to addressing contemporary problems. Therefore, we directed our research toward historical investigation and analysis to identify the origins of the historical significance of context in the production and interpretation of texts. This conceptual article employs content analysis to extract results from the literature of pioneering historians and interpretive philosophers across various social science and humanities fields. We moved some of that to specialists in urban studies, focusing on pioneer and contemporary architects, city planners, and city designers. We obtained results related to their contributions from a multidisciplinary perspective.

By framing historical investigation and employing critical historical analysis as a method, this study aims to develop an approach that assists researchers. This approach attempts to improve the quality and depth of literary narratives in academic urban studies. Hence, we had to search for an entry point to study the interaction between context and text in the theoretical discourse of previous theorists and to first communicate their visions through a historical perspective of the development of these visions.

The integration of these visions resulted in eight coherent thematic groups that facilitated or paved the way for an integrated intellectual approach. Three are relevant to historians and interpretive philosophers: contextual frameworks and hermeneutics; historical analysis and epistemological inquiry; and power, social dynamics, and contemporary relevance. Five are relevant to specialists in urban studies: aesthetic values in urban history, green spaces, and garden cities; historical context and architectural development; evolving architectural thought; and historical context in neighborhood design.

Based on the contributions and insights of pioneers in observing the importance of the relationship between context and text in the production of knowledge and describing it in groups with key aspects and priorities for critical analysis from a historical perspective, we were able to reach practical strategies and guidelines that can help researchers who are at the beginning of their careers to achieve a literary narrative that follows historical contexts but is in harmony with contemporary conditions.

This study primarily references urban studies literature from Western sources, as these sources offer greater accessibility to peer-reviewed publications and comprehensive datasets in English. This focus may inadvertently limit the representation to urban theories and experiences from non-Western contexts. Future research should aim to include more diverse regional perspectives to ensure broader applicability and inclusivity in urban studies discourse. This study employed snowball sampling to identify key literature, leveraging its strength in uncovering influential works and tracing the development of thematic research. However, we acknowledge that this method may introduce sampling bias, as it tends to reinforce existing scholarly networks and dominant perspectives. As such, there is a risk of underrepresenting alternative or emerging viewpoints, particularly from non-Western or less-cited sources.

Future research on revisiting historical context in urban studies may extend the explanations by incorporating a wider range of voices from philosophy, history, and urban practice, while maintaining a rigorous approach to evaluating methodologies and evidence. Early-career researchers need to produce more context-sensitive analyses and interpretations by drawing on different disciplines and exploring a broader range of sources, including peer-reviewed articles. Deeper engagement with history is critical to understanding current urban challenges and shaping the future of the field.

Supplementary Materials

All data from the Supplementary Materials can be tracked through the Fairshare using the Figshare link: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.29236112.v5 (access date: 6 June 2025) File S1 outlines a comprehensive exploration of the historical background, featuring a curated collection of literature. It includes 17 books, listed in two tables (Tables S1 and S2) and Figures S1 and S2. File S2 shows the historical significance of context in text production, explored through Table S3, which examines the contributions of six historians and interpretive philosophers, and Table S4, which highlights the work of eleven specialists in architecture, urban planning, and urban design. File S3 includes the practical guidelines derived from the findings of key historians and interpretive philosophers in the social sciences and humanities (Table S5), as well as specialists in urban studies, architecture, urban planning, and urban design (Table S6).

Author Contributions

All authors collaborated on the conceptualization, methodology, writing—review, and editing of the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Cohen, S. Physical context/cultural context including it all. Oppositions 1974, 2, 1–39. [Google Scholar]

- Yücel, R.K.; Arabacıoğlu, F.P. “Context” knowledge in architecture: A systematic literature review. Megaron 2023, 18, 366–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Östling, J.; Sandmo, E.; Larsson, D.; Anna, H.; Hammar, N.; Nordberg, K.H. Circulation of Knowledge: Explorations in the History of Knowledge; Nordic Academic Press: Lund, Sweden, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Elshater, A.; Abusaada, H. From uniqueness to singularity through city prestige. Proc. Inst. Civ. Eng.-Urban Des. Plan. 2022, 175, 91–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nkomo, S.; Hoobler, J.M. A historical perspective on diversity ideologies in the United States: Reflections on human resource management research and practice. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2014, 24, 245–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouwenberg, S.; Singler, J.V. Creolization in Context: Historical and Typological Perspectives. Annu. Rev. Linguist. 2018, 4, 213–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carr, D. Experience and History: Phenomenological Perspectives on the Historical World; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs, K. Historical Perspectives and Methodologies: Their Relevance for Housing Studies? Hous. Theory Soc. 2001, 18, 127–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dilthey, W. Introduction to the Human Sciences; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Dilthey, W. Wilhelm Dilthey: Selected Works, Volume IV: Hermeneutics and the Study of History; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Kuhn, T.S. The Structure of Scientific Revolutions; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Tosh, J. The Pursuit of History: Aims, Methods and New Directions in the Study of Modern History; Routledge: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimm, S.R. Why Study History? On Its Epistemic Benefits and Its Relation to the Sciences. Philosophy 2017, 92, 399–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elshater, A.; Abusaada, H. People’s absence from public places: Academic research in the post-COVID-19 era. Urban Geogr. 2022, 43, 1268–1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mumford, L. The City in History: Its Origins, Its Transformations, and Its Prospects; Harcourt, Brace & World: San Diego, CA, USA, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs, J. The Death and Life of Great American Cities; Random House: New York, NY, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Kostof, S. The City Shaped: Urban Patterns and Meanings Through History; Bulfinch: Boston, MA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Shane, D. Recombinant Urbanism: Conceptual Modeling in Architecture, Urban Design and City Theory; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Elshater, A.; Abusaada, H.; Tarek, M.; Afifi, S. Designing the socio-spatial context urban infill, liveability, and conviviality. Built Environ. 2022, 48, 341–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abusaada, H.; Elshater, A. From Social Sciences to Urban Praxis: A Critical Synthesis of Historical–Contextual Inquiry and Analysis in Urban Studies. Societies 2025, 15, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elshater, A.; Abusaada, H. Applying Contextualism: From Urban Formation to Textual Representation. Societies 2025, 15, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motta-Roth, D. The Role of Context in Academic Text Production and Writing Pedagogy. In Genre in A Changing World; The WAC Clearinghouse; Parlor Press: Anderson, SC, USA, 2009; pp. 321–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sendur, K.A.; van Drie, J.; van Boxtel, C. Historical contextualization in students’ writing. J. Learn. Sci. 2021, 30, 797–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abusaada, H.; Elshater, A. Decoding Near Synonyms in Pedestrianization Research: A Numerical Analysis and Summative Approach. Urban Sci. 2024, 8, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abusaada, H.; Elshater, A. Editorial: Beyond superficial readings: Integrating authentic context in urban studies literature review for early-career researchers. Proc. Inst. Civ. Eng.-Urban Des. Plan 2024, 177, 91–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuff, D.; Loukaitou-Sideris, A.; Presner, T.; Zubiaurre, M.; Crisman, J.J. Urban Humanities: New Practices for Reimagining the City; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Lowenthal, D. The Past is A Foreign Country; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, A.B.; Heffernan, M.; Price, M.; Harvey, D.C.; DeLyser, D.; Lowenthal, D. The Past Is a Foreign Country—Revisited. AAG Rev. Books 2017, 5, 201–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giedion, S. Space, Time, and Architecture: The Growth of a New Tradition; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1954. [Google Scholar]

- Tafuri, M. Theories and History of Architecture; Granada: London, UK, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Parker, C.; Scott, S.; Geddes, A. Snowball Sampling; SAGE Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Kibiswa, N. Directed qualitative content analysis (DQlCA): A tool for conflict analysis. Qual. Rep. 2019, 24, 2059–2079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, B. The History of Western Philosophy; Routledge: London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Gadamer, H.-G. Truth and Method; Bloomsbury Publishing: London, UK, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Foucault, M. The Order of Things: An Archaeology of the Human Sciences; Éditions Gallimard: Paris, France, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Collins, C.C.; Collins, G.R. Camillo Sitte: The Birth of Modern City Planning; Dover Publications: New York, NY, USA, 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Howard, E. Tomorrow: A Peaceful Path to Real Reform; Swan Sonnenschein & Co., Ltd.: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Burnham, D.; Bennett, E. Plan of Chicago; Princeton Architectural Press: New York, NY, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Rossi, A. The Architecture of the City; The MIT Press: Cambridge, UK, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Benevolo, L. The History of the City; MIT Press: Cambridge, UK, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Keulen, S. Historical Analogies. J. Appl. Hist. 2023, 5, 111–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, B. Human Knowledge: Its Scope and Limits; Routledge: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).