Abstract

This study presents the theoretical depth of urban research by proposing a four-stage contextual conceptual guide for integrating historical and societal contextual factors within the nexus of time and space. Addressing a critical gap in urban research, it focuses on early career researchers (ECRs), who often struggle to systematically incorporate contextual dimensions into their academic writing, particularly in theoretical discussions. The first two stages establish a foundation through historical inquiry and thematic analysis. These two stages also reveal how context is conceptualized across disciplines and highlight its active role in shaping human knowledge. Stage one examines the role of context in academic writing by analyzing six influential 20th-century thinkers (1900–2000). Stage two maps contemporary perspectives through a directed content analysis of 14 scholars (2000–2024) and six pivotal scholars in the social sciences. The third stage identified four interconnected factors that shape contextual interpretations: key concepts, context components, contextual factors, and thinkers’ contributions. These factors explain how context functions as an active and integral force for understanding texts, historical events, and linguistic phenomena. This stage also highlights four broader contextual factors: historical and societal contextual factors, conditions driving urban transformations, influential social dynamics, and inherent challenges that emerge from critical scholars’ analysis. The final stage operationalizes these insights into five fundamental guidelines for embedding contextual factors into high-quality academic writing, particularly in urban research. This calls for theorists to develop practical guidance for integrating context and text into academic writing by enhancing the theoretical depth, analytical consistency, and interdisciplinary collaboration.

1. Introduction

Academic discourse in urban research is integrally multidisciplinary, drawing on insights from linguistics, psychology (psycholinguistics), sociology (sociolinguistics), anthropology, and cultural studies to examine urban dynamics critically [1,2]. At the heart of this discourse is the interplay between context (the socio-spatial, historical, and institutional conditions shaping urban phenomena) and text, representing how these phenomena are communicated through scholarly work, policies, and media [3,4]. The significance of context is widely acknowledged across disciplines, including philosophy [5,6], academic writing [7,8], linguistics [9,10], sociolinguistics, language philosophy [11], psycholinguistics, and critical discourse studies [12]. They also play an essential role in functional linguistics [13,14,15], publication practices [16,17], and historical linguistics [11,18]. Furthermore, research on information and communication technology for development (ICT4D) highlights how contextual influences shape the production and interpretation of academic texts [19].

Some researchers emphasize contextual influences in academic writing [1,5,6,9], while early career researchers (ECRs) might face a challenge in the more profound interpretation of the context of writing. This could affect how knowledge is framed and understood. In social sciences, context is central to human communication and knowledge construction [20]. Critical discourse studies have revealed how language reflects power structure and social dynamics [12,21,22]. Historical research has emphasized the importance of contextualization in developing critical discourse perspectives [23]. In addition, historical linguistics examines how cultural and social contexts influence linguistic change over time [11,24]. Drawing from critical discourse analysis [25], situated learning theory [26], and social constructivism, considering the context of text allows scholars to evaluate historical and societal factors in their work [27].

Urban research acknowledges the role of context in shaping knowledge [20,28]. However, systematic methods for integrating key contextual factors such as historical path dependencies, sociopolitical conflicts, and cultural shifts are often lacking. ECRs usually prioritize these dimensions in empirical fieldwork (e.g., mapping gentrification or analyzing policy timelines) but tend to sideline them in scholarly texts, treating context as a static descriptor rather than a dynamic force shaping research design and interpretation [29,30]. This decontextualized approach leads to biased interpretations, mainly when terms like “sustainability” or “visual vitality” are deployed as universal concepts, divorced from their historical policies (e.g., greenwashing agendas), cultural values (e.g., community aesthetics), or institutional hierarchies (e.g., corporate influence). This guide fosters contextually grounded texts with implications for interdisciplinary research by bridging theory and practice.

This study examines contextualism as a foundational theory in architecture, urban planning, and urban design [6,31,32,33,34]. This highlights a gap in the literature in which scholarship primarily focuses on design principles and policy frameworks. There is a lack of guidance studies on how ECRs integrate—or fail to integrate—contextual factors into their academic writing, particularly in theoretical discussions. This gap perpetuates a paradox. While urban disciplines prioritize context in practice, their academic discourse often reproduces decontextualized narratives, obscuring the historical and societal factors that animate urban phenomena. Addressing this oversight is essential for fostering contextually aware and critically engaged texts that bridge applications with textual reflexivity.

Contextual factors—elements within the urban environment that shape events, processes, or outcomes [35,36]—encompass historical, societal, and institutional dimensions such as social, cultural, or political conditions [37,38,39]. Their influence varies depending on situational specificity [40,41,42], underscoring the need for tailored analysis in urban research. Understanding contextual factors is crucial for analyzing how external conditions shape scientific explanations across disciplines and address contemporary societal challenges, as these factors inherently influence research outcomes and real-world applications. When adopting an urban paradigm, whether a theory, approach, or epistemological framework, scholars should first examine its original context and then trace its evolution across linguistic, spatial, and temporal contexts.

This study aimed to develop a four-stage contextual, conceptual guide to empower ECRs to address real-world urban issues with greater depth and contextual awareness. This process ensures that the application of the model to urban reality is methodologically sound and contextually relevant. Therefore, this study critically investigates how context shapes academic discourse. By adapting contextualist principles to address academic writing challenges, this guide empowered to engage more effectively with historical, cultural, linguistic, and social contexts in their scholarly work.

As such, this study established a historical inquiry guidance to integrate contextual analysis into academic writing. First, it examined two groups of scholars.

- Twenty scholars, including six foundational thinkers from 1900 to 2000 (Dilthey, Russell, Gadamer, Kuhn, Foucault, and Tosh) [38,43,44,45,46,47], and fourteen contemporary scholars from 2000 to 2024, have expanded the discourse on historical inquiry.

- Fourteen critical scholars were selected to contribute to discourse analysis, historical studies, and linguistics, offering insight into how context shapes knowledge production and interpretation.

This conceptual study utilized a sample of six influential social science publications from 2008 to 2023. This small sample was analyzed to explore the interplay between context and text. This guide provides ECRs with practical approaches to produce critical and contextually grounded research by examining how historical and societal factors influence academic discourse. This guide highlights how analyzing the context–text interplay can enhance the theoretical depth of urban research. In addition, this study addressed four key research questions:

- How is context conceptualized across different disciplines?

- How do foundational thinkers interpret the context–text interplay and how does it shape their writing?

- What factors influence the context–text interplay?

- What foundational guidelines embed contextual factors in academic urban research, and how do they contribute to high-quality academic writing?

This guide bridges the gap between historical inquiry and theoretical reflection through these questions, offering an original contribution with broad applicability. This provides guidelines to help ECRs integrate contextual factors into their writing skills. While rooted in urban research, the guide’s foundational principles are adaptable to other fields, encouraging more reflexive and nuanced academic writing practices in social sciences, humanities, and beyond. The originality of this study lies in reorienting contextualism from its traditional application to planning and design to enhance academic writing precision. This innovative approach seeks to connect theoretical foundations with practical advancements in knowledge, thereby offering a guide for reconciling abstract concepts with applied research outcomes. This study seeks to empower ECRs to tackle real-world problems with a deeper understanding of the contexts that shape them, fostering theoretically rigorous and practically relevant research.

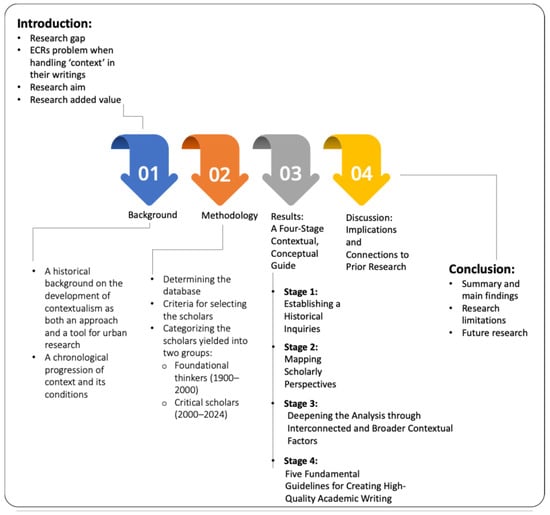

Following this introduction, the research unfolds in six sequential sections (Figure 1). The second section reviews the relevant literature, aiming to contextualize the study and trace the development of contextualism, focusing on its chronological evolution. The third section details the methodology, describing the processes of data collection and analysis to ensure methodological rigor and transparency. The fourth section presents key findings, directly addressing the research objectives through appropriate data analysis methods. The discussion in the fifth section summarizes the contributions and implications of the research findings. Finally, the conclusion offers recommendations and suggests potential avenues for future research. This structure guarantees logical flow, consistency, and coherence, providing a comprehensive and well-organized research process.

Figure 1.

The research structure.

2. Background: Context-Based Texts in Shaping the Contextualism Discourse

This study adopts “contextualism” to explore how various dimensions—such as the concept of the term, its origins, key scholars, and its evolution—shape its understanding. ECRs may sometimes use this term without fully considering its context, resulting in a superficial grasp of its meaning. This section outlines the historical development of contextualism as both an approach and a tool in urban research, tracing its chronological progression and the conditions that influenced its evolution. By framing “contextualism” as a key term in urban research, this paper emphasizes the importance of examining its origins and the circumstances that guided its development. Such an understanding is essential for ECRs to effectively address contemporary challenges in the field.

Rather than being a singular movement, contextualism is a recurring theme that underscores the evolving relationship between built environments and their historical, social, and cultural conditions [33,48]. Its influence extends throughout the history of architecture, urban planning, and urban design and manifests itself differently across periods and intellectual trends [49]. The historical background explores its origins, development, and key contextual factors [50,51].

Contextualism in urban design and architecture emphasizes the relationship between new developments and their surrounding built and natural environments, ensuring that design interventions respect historical, social, cultural, and environmental contexts rather than existing in isolation. Mathew Carmona [48] discusses contextualism as an essential dimension of urban design, highlighting its role in fostering continuity between past and present while allowing cities to evolve dynamically. Contextualism contrasts with modernist universalism, which often disregards local identity in favor of standardized architectural expressions. Kevin Lynch [36] also emphasizes the significance of contextual sensitivity in urban environments, arguing that legibility and sense of place are enhanced when new developments integrate with existing urban fabric. Similarly, Aldo Rossi [52] advocates for an understanding of the city as a collective memory, where historical layers and typologies should inform contemporary urban interventions. This perspective aligns with Jane Jacobs’ [35] critique of large-scale urban renewal projects that fail to acknowledge the fine-grained complexity of historical neighborhoods. By integrating these perspectives, contextualism emerges as a critical framework for ensuring that urban and architectural developments contribute meaningfully to the built environment while maintaining cultural and historical integrity.

Contextualism began to take shape before the 1950s as it emerged from the rejection of universalism [53,54]. While the term “contextualism” appeared later, the seeds of its concerns were visible in earlier architectural and urban theory. For example, the picturesque movement of the 18th century emphasized the integration of buildings with their natural surroundings, rejecting the rigid geometry of classical styles [55]. The Arts and Crafts movement of the late 19th and early 20th centuries similarly championed handcrafted buildings responsive to local materials and traditions, opposing mass production and standardized design [56]. These movements, while not explicitly “contextualist”, highlight the importance of site-specificity and local character. The early 20th century saw the rise in the City Beautiful Movement, which, although aimed for grand, monumental schemes, still considered the existing urban fabric and its historical context to some degree [57].

In the mid-20th century, contextualism emerged as a reaction to the rigid universalism of modernist urban planning and architecture. However, the modernist movement emphasizes universal principles of form and function, primarily in a disregarded context. For example, Le Corbusier’s [58] vision of a Radiant City proposed sweeping changes to existing urban forms, often without considering the unique characteristics of specific places. This rejection of historical context and local traditions would become a significant point of departure for later contextualist approaches. While modernist movements, such as the International Style, prioritized functional efficiency and abstract aesthetics, they often ignored local histories, cultural identities, and social dynamics [59]. In contrast, contextualism emphasizes harmony with existing physical, historical, and cultural landscapes [1].

Mies van der Rohe’s mature work, exemplified by projects such as the Barcelona Pavilion (1929) and the Farnsworth House (1951), reveals a nuanced engagement with context. As Mathew Aitchison [60] argues, Rohe’s approach to contextualism is not defined by direct references to historical or vernacular styles but rather by a precise orchestration of spatial composition, materiality, and proportion. His designs establish an internal logic that subtly harmonizes with their surroundings by integrating nature, light, and structural clarity. This approach aligns with what can be termed modernist contextualism or essentialist contextualism, a mode of responding to a context that prioritizes fundamental spatial and material principles over mimetic adaptation. Contrary to Rohe’s perception as detached from context, this interpretation underscores his deeply considered yet distinctly modernist approach to site specificity.

Between the 1950s and the 1960s, contextualism evolved into a comprehensive theory and approach to urban research. During this period, a movement among British architects in the 1950s embraced “new brutalism” theories, which addressed the relationship between urban design and the cultural identity of historic districts [61]. For example, the work of Allison and Peter Smithson [62] enhanced the social dimension of urban construction by introducing concepts such as the “warehouse” aesthetic, such as the Soho House, the Coventry Centre (1956), and the Park Hill project (1961) in Sheffield provided concrete examples of how contextualism could serve as a tool to protect urban heritage and develop environments that meet contemporary needs.

The 1960s and the 1970s saw a growing focus on the relationship between humans and their urban environments. Colin Rowe and Fred Koetter [63] introduced the concepts of the “Glued City” and city as a collage using terms such as “bricolage” and “collage” to describe how cities are assembled from disparate elements to form a contemporary unity. In the postmodern era, social criticism of contextualism further evolved as researchers reexamined the relationship between architecture and the city from a critical social perspective. The 1970s marked a qualitative shift in contextualism with the emergence of new ideas in architecture, urban planning, and urban design [53]. During this period, theorists and practitioners challenged modernist universalism by emphasizing local conditions, historical continuity, and cultural specificity. Scholars have explored new approaches to urban forms, moving from rigid figure–ground patterns to more adaptive and responsive field conditions [54].

The term “contextualism” was first introduced in the field of urban design by Thomas Schumacher [32], Stuart Cohen [6], and Grahame Shane [33]. They interpreted this theory as a means of reconciling the conditions of new urban development with experiences in traditional or historical cities. Contextualism has emerged to protect historic areas from radical change or destruction. In projects where an architect works in a new area, the absence of established parameters contrasts sharply with the challenges of working within a pre-existing urban fabric.

In works such as Learning from Las Vegas [64] and Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture [65], Venturi argued that a city is not merely a physical entity, but a living fabric woven from people’s experiences and interactions with their environment. This period also witnessed the influence of emerging theories—such as “new rationalism”—which focused on semantic and symbolic aspects of design and introduced a new critical dimension in evaluating the relationship between urban form and its environment. During this phase, contextualism was no longer viewed solely as a design tool but as an approach to understanding the “Genius Loci” (the spirit of place), as described by Norberg-Schulz [66]. He argues that the genius of a place is formed by the natural, historical, and cultural conditions that define its identity, thereby necessitating an analytical method that considers every part of the city as a part of an integrated whole.

The 1980s and beyond saw the development of contextualism, diversifying into different approaches and incorporating new theoretical influences. Social sciences and humanities scholars increasingly employ critical discourse analysis approaches to analyze how power dynamics and social inequality are embedded in urban environments. Critical discourse analysis approaches have increased awareness of how language and representation shape our understanding of context.

Postmodernism, with its rejection of grand narratives and focus on local conditions, also fueled the rise in contextual approaches. For example, Cornell [67] discusses how post-structuralist theory, a key component of postmodernism, emphasizes the textuality of human experiences and challenges overarching narratives, thereby encouraging more localized and context-specific analyses. In urban research, new urbanism, as a paradigm shift in architecture and urban design theory and movement, drew on traditional city planning principles for its designs, emphasized the creation of spaces, and facilitated social interaction [51]. Later, in his book Context in Architectural Composition, Venturi [34] recognized the importance of contextualism as a tool for rethinking urban design, contending that architecture is not just an assembly of forms, but an expression of collective memory and the emotional reservoir of society. According to Ellin [50] and Schumacher [31] in his article Contextualism: Urban Ideals + Deformations, contextualism should not be regarded as an independent entity with its own life but rather as a tool for analyzing the circumstances that influence urban design based on prevailing usage, culture, and economic conditions.

In this vein, we assume that properly situating historical developments within their contexts and understanding how they evolve add significant depth and originality to academic texts. However, a noticeable gap exists among ECRs, including among advanced-degree students. Many ECRs use urban paradigms (such as theories, movements, schools of thought, trends, and even specific terms) from a single, predominantly spatial perspective, often overlooking the critical interplay between the spatial and temporal dimensions.

In other words, ECRs should review “contextualism” texts from a cognitive perspective and connect their ideas to the broader conditions and circumstances in which their research is embedded. The paradigms were not fixed but were devised to address specific contexts. While most scholars consider the context when engaging with urban formation, they frequently miss this in their theoretical approaches to solving current challenges. This study addresses this gap by offering guidelines for writing texts that move beyond mere cognitive considerations to embrace the historical and societal dimensions.

3. Methodology

This concept paper develops a four-stage contextual, conceptual guide to help ECRs integrate context into their academic writings. Rather than focusing on stylistic approaches, this study emphasizes the influence of historical and societal contextual factors, including social, cultural, political, economic, environmental, technological, and legal elements across time and space, on shaping academic writing in urban research. To construct this guide, we conducted a systematic conceptual analysis drawing on diverse social sciences and humanities perspectives.

Below, we describe the methodological steps, including the selection of scholars, analytical techniques, and conceptual guidance development. We define context as the circumstances surrounding a text’s creation, including the author’s background, academic traditions, and broader socio-institutional structures. A search across multiple academic databases confirmed the prominence of this concept within research (Academia: #479,799 results; Google Scholar: #9860 results; ResearchGate: #100,000 results for “context and text”). Given the extensive literature, we refined our selection of sources based on the following criteria.

- (a)

- Author Contributions: Studies conceptualizing the relationship between context and text should be included to ensure a comprehensive yet manageable scope.

- (b)

- Application of Contextual Analysis: Studies that apply contextual analysis to academic writing practices.

- (c)

- Citation impact and disciplinary recognition: Works widely cited and recognized within their respective disciplines.

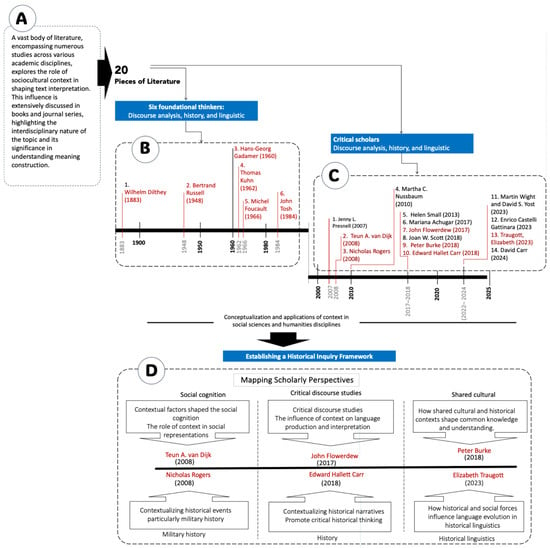

This process yielded a vast initial pool of sources (e.g., #9860 results in Google Scholar for “context and text”), which we narrowed down to 20 influential scholars categorized into two groups:

- Foundational thinkers (1900–2000): Scholars who shaped foundational context theories in knowledge production.

- Critical scholars (2000–2024): Researchers who emphasize evidence-based analysis of academic writing practices. A subset of six scholars was further examined using directed content analysis to trace shifts in methodological approaches.

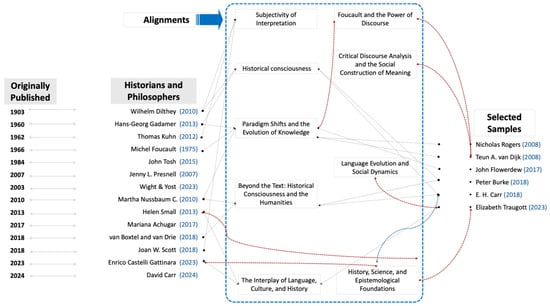

Figure 2 illustrates the sampling strategy, and Appendix A (Table A1) provides a detailed classification of the selected studies. These scholars and publications were selected based on their contributions in bridging the gap between context and text in social science and humanities research.

Figure 2.

Sampling choice: The outlined significance of each author’s work of literature. The scholars in red text were selected for deeper investigation. Letters from A to D represent the sequence of data analysis. Source: the authors based on group of literature [11,12,23,38,39,43,44,45,46,47,56,68,69,70,71].

By mapping these perspectives, this study established a historical inquiry guidance that situates contextual analysis within academic discourse writing. We began by examining six foundational thinkers whose work laid the groundwork for understanding the context of knowledge production: Wilhelm Dilthey [43], Bertrand Russell [44], Hans-Georg Gadamer [45], Thomas Kuhn [46], Michel Foucault [38] and John Tosh [47]. These scholars provided theoretical underpinnings for analyzing historical and societally contextual contexts.

Building on this foundation, we expanded our analysis to include more recent scholars who have furthered the discourse on historical inquiry. Fourteen critical scholars (2000–2024) were identified, including Presnell [68] van Dijk [69], Rogers [70], Nussbaum [71], Small [39] Achugar [72], Flowerdew [12], Scott [73], Burke [74], E. H. Carr [23], Wight and Yost [56], Gattinara [75], Traugott [11], and Carr [76]. These scholars have contributed significantly to understanding how historical context, societal influences, and intellectual context shape knowledge production.

The selection criteria included relevance to contemporary academic writing (2008–2024). The selection criterion was methodological innovation in the contextual analysis. The other criteria include significant theoretical and empirical contributions. This timeframe ensures that the study captures emerging challenges in academic writing, reflecting the growing importance of contextual analysis in interdisciplinary research.

Subsequently, we selected a sample of six influential social science publications: three books, two book chapters, and one peer-reviewed journal article published in English between 2008 and 2023. Our analysis involved investigating the context–text interplay through the work of six influential key thinkers, each of whom has significantly contributed to discourse analysis, history, linguistics, and contextual theory. The authors chose Teun A. van Dijk [69], Nicholas Rogers [70], John Flowerdew [12], E. H. Carr [23], Peter Burke [74], and Elizabeth Traugott [11] to represent critical voices in fields such as discourse analysis, historical studies, and linguistics.

The selected scholars played a central role in advancing the understanding of how context influences text, making their work foundational for this study. The selected authors are leading experts, whose research highlights the significance of contextual analysis, making their work central to this study. This approach addresses the current concerns regarding bridging the gap between text and context in academic writing. The chosen scholars have contributed significantly to advancing the understanding of the context–text relationships. Their research emphasizes the increasing importance of contextual analysis in academic writing, positioning their work as central to this investigation.

To examine the historical and societal contextual factors that shape academic writing, including cultural, political, economic, technological, and legal dimensions, we employed three qualitative research techniques:

- Thematic Analysis [77]: identifying recurring themes across the selected texts.

- Directed Qualitative Content Analysis [78,79]: examining explicit contextual references in academic writing.

- Methodological Synthesis: developing a structured conceptual guide for integrating context into academic texts.

These techniques allowed us to examine how historical and societal contextual factors, including cultural, political, economic, environmental, technological, and legal elements, shape academic writing across disciplines.

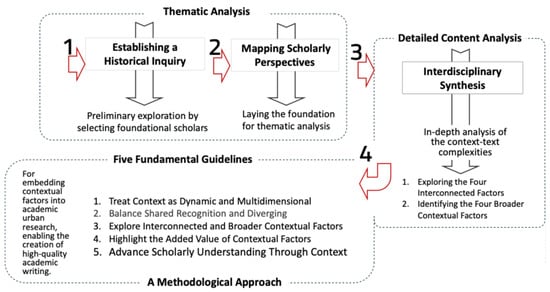

Based on our analysis, we developed a four-stage contextual conceptual guide to help researchers integrate contextual factors into their research process. This guide is particularly relevant for interdisciplinary research where the relationship between context and knowledge production is central, such as language development, educational reform, and urban research. The four stages are as follows:

- Establishing a Historical Inquiries: Situating research within its historical and intellectual traditions.

- Mapping Scholarly Perspectives: Identifying key contextual factors (e.g., social, cultural, political, economic, environmental, technological, and legal).

- Interdisciplinary Synthesis: Integrating insights from multiple disciplines by deeply analyzing interconnected and broader contextual factors.

- Five Fundamental Guidelines: Applying context-sensitive writing strategies across multiple disciplines in urban research (Figure 3).

Figure 3. A four-stage contextual, conceptual guide.

Figure 3. A four-stage contextual, conceptual guide.

4. Results: A Four-Stage Contextual, Conceptual Guide

This section synthesizes insights from 20 literature materials in the social sciences and humanities (for six foundational thinkers and fourteen critical scholars) to advance the understanding of the interplay between context and defined as the historical and societal contextual factors shaping knowledge and text, the written representation of that knowledge. This study examines the influence of context on the interpretation, dissemination, and reception of text in social science research. It aims to address a critical gap—the frequent disparity between empirical objectivity and textual reflection, particularly among ECRs. In the first stage, the findings examine, through historical inquiry, how evolving contexts—such as policy shifts, technological advancements, and cultural movements—have influenced academic writing practices.

In the second stage, a qualitative thematic analysis of six theoretical guidance reveals how scholars across disciplines conceptualize contexts. The third stage identified four interconnected and border contextual factors that influence interpretations to enhance our understanding of how context shapes discourse. The final stage proposes five fundamental guidelines to help researchers embed context into their writing. By bridging theoretical rigor with actionable strategies, this guide rarely empowers ECRs to produce nuanced, contextually grounded work that challenges decontextualized paradigms in urban research.

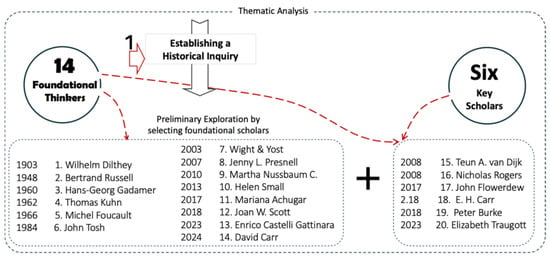

4.1. Stage 1: Establishing a Historical Inquiries

This stage opens by defining knowledge as a dynamic construct shaped by historical, cultural, and intellectual contexts and starts by integrating the key perspectives and effectively referencing foundational thinkers (e.g., Dilthey, Russell, Gadamer, Kuhn, Foucault, and Tosh) and then building on these ideas with contemporary scholars (e.g., Achugar, Scott, D. Carr, Gattinara, Wight and Yost, Traugott, and Small). Figure 4 illustrates the first stage of the thematic analysis, which involved establishing historical inquiries.

Figure 4.

Scholars included in the thematic analysis: 14 foundational thinkers and six key scholars. Source: the authors based on literature [11,12,23,38,39,43,44,45,46,47,56,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76].

This progression illustrates how the field has evolved and the intention to emphasize educational implications and tie the discussion to the importance of historical consciousness and context in shaping research and academic writing. Finally, it synthesizes insights and concludes by summarizing the key themes and indicating how these insights support improved literature reviews, concerning the supporting figures and tables.

This stage examined the work of two groups of scholars: 14 foundational thinkers (chronologically listed by the year of their publication) and six key scholars (chronologically listed by the year of their publication). The analysis explores critical variations in how context is conceptualized and applied across disciplines, tracing its evolution and impact across different fields.

4.1.1. Contemporary Applications and Educational Implications

Our findings reveal that knowledge is not a static collection of facts, but a dynamic construct shaped by historical and societal contexts. This perspective is evident across diverse fields, from hermeneutics and history to discourse analysis and linguistics. Key insights from our study include the significance of hermeneutics and historical consciousness, paradigm shifts and knowledge evolution, the influence of power dynamics on discourse, and broader educational and societal implications of contextual understanding. This is evident in the hermeneutical approaches of Dilthey [43] and Gadamer’s [45] focus on historical consciousness in Carr [23], Burke [74], and Kuhn’s [46] analysis of paradigm shifts. Scholars have demonstrated how context influences knowledge production and interpretation. Building on this foundation, van Dijk [69] and Flowerdew [12] extended these ideas to discourse analysis, exploring how social and cultural contexts affect knowledge construction. At the same time, Foucault [38] redefined power as embedded in discourse, arguing that language reflects and shapes social hierarchies.

4.1.2. Foundational Perspectives on Context and Knowledge

Contemporary thinkers advanced these concepts. For instance, Achugar [72] integrates these perspectives through critical discourse analysis, showing how power dynamics, ideologies, and social norms are encoded in language and applying historical theories to interpret urban effects. Scott [73] and Carr [76] examined indeterminacy in historical narratives through a psychoanalytic lens. Gattinara [75] connects architectural history to contemporary practice, and Wight and Yost [56] emphasize the critical use of sources and narrative structures in historical analysis. Traugott’s [11] work on language evolution within social hierarchies demonstrates the interconnectedness of language, culture, and social power, thus complementing Small’s [39] insight into social dynamics. The emphasis on historical consciousness and contextual understanding has significant educational implications, as highlighted by van Boxtel et al. [80] who emphasized the importance of the humanities in fostering critical thinking and civic engagement.

Our examination of the relationship between context and text among these scholars reveals a shared understanding: knowledge is not fixed but is constantly influenced by historical, cultural, and intellectual contexts. This dynamic perspective significantly affects historical research and discourse interpretation. By acknowledging the subjectivity of interpretation, the role of paradigm shifts, and the influence of power dynamics, this stage provides the foundation for integrating contextual understanding into academic writing.

These insights, synthesized in Figure 5 and Table 1, highlight key themes for improving the literature review (see Appendix B—Table A2 and Table A3—for detailed tables). These themes include subjectivity of interpretation, historical consciousness, paradigm shifts, power dynamics in discourse, and the broader role of humanities.

Figure 5.

The alignment between foundational thinkers and key scholars (2008–2024). Source: The authors based on literature [12,23,38,39,43,44,45,46,47,56,68,69,70,71,72,75,76].

Table 1.

Themes, aligned scholars, and relevance to the literature review section.

The findings of this subsection emphasize the importance of critically engaging with historical interpretations and acknowledging the factors influencing how we perceive and interpret the past. The following two stages build on these findings to provide practical strategies for integrating these insights into the literature.

4.2. Stage 2: Mapping Scholarly Perspectives

The second stage focused on mapping scholarly perspectives to identify themes and patterns across the six publications using qualitative thematic analysis. The findings demonstrate that context is a dynamic and multidimensional construct shaped by historical and societal factors. Notable critical scholars such as van Dijk [69], Rogers [70], Flowerdew [12], E. H. Carr [23], Burke [74], and Traugott [11] highlight critical variations in how context is conceptualized and applied across disciplines, providing.

These insights equip urban researchers to conduct more contextually aware academic writing, enhancing their academic contributions’ depth and relevance. This thematic analysis stage maps scholarly perspectives and explores context–text interplay in social science. Moving beyond individual scholars, it identifies broader themes and connections among scholarly viewpoints. This stage aimed to provide structured guidance for understanding context-based texts within the field of study. In this section, each scholar focuses on a specific perspective. Figure 6 highlights these scholars, and their insights linked to six major themes related to the interaction between text and context, valuable insights for future research.

Figure 6.

Six critical scholars and their insights. Source: The authors based on literature [11,12,69,70,74,76].

4.2.1. Contextualizing in Social Representations

Van Dijk’s [69] views on context-based texts provide a valuable perspective for understanding social representations. Our thematic analysis reveals how contextualizing these representations enhances research in linguistics, discourse analysis, and critical discourse analysis. This approach offers several key benefits. It provides a deeper understanding of the context itself. It increases awareness of power dynamics and societal influences. It offers fresh insights into how context shapes knowledge production and interpretation. It also expands opportunities for future research. This manuscript reinforces that context is not a static backdrop, but a dynamic construct influenced by historical and societal factors. This understanding has practical implications for urban researchers, highlighting the importance of recognizing the broader societal changes that shape their research environments. By treating context as a vital factor rather than a neutral background, researchers are encouraged to engage more deeply with factors influencing urban development and transformation.

Moreover, the findings emphasize that a discipline’s power dynamics and authoritative voices significantly shape valid knowledge. Urban researchers should remain aware of the dominant narratives that might overshadow alternative or marginalized perspectives. This insight advocates more inclusive approaches to contextual analysis, ensuring that multiple voices and perspectives are integrated into interpreting urban phenomena. Researchers can better account for political, economic, or social shifts that reshape urban spaces by understanding how societal transformations influence knowledge production. This understanding is particularly relevant for investigating cities undergoing rapid change, as they must consider how evolving contexts affect research interpretations and communities being studied. The evolving nature of the context presents new research opportunities, suggesting that researchers continuously update their understanding of urban phenomena by incorporating ongoing societal shifts into their analysis.

This recognition of the context as dynamic encourages future scholars to adopt more flexible and adaptive research methodologies that effectively capture the complexities of urban environments. These findings urge urban researchers to engage critically with the factors that shape their fields, particularly by integrating societal transformations into their analyses. This insight promotes comprehensive and critical understanding that empowers researchers to produce nuanced and impactful academic work.

4.2.2. Contextualizing Historical Events in Military History

According to a thematic analysis of Nicholas Rogers’ [81] views on context-based texts, the findings underscore that context is a dynamic force shaped by intricate societal factors, including the social, political, economic, and legal dimensions. Rogers’s [70] exploration of naval impressment in Georgian Britain exemplifies how understanding historical practices necessitates a nuanced examination of the interplay between these influences. Here, context informs not only the execution of impressment but also shapes societal reactions and opposition to such practices. These findings highlight the critical importance of societal influence in producing and interpreting historical knowledge accurately. In fields such as military history, where events may be scrutinized in isolation, neglecting the context can lead to an incomplete or skewed understanding. Therefore, a contextual approach to historical research is necessary.

These insights advocate critical engagement with contemporary political, social, and legal contexts that shape the interpretation of historical events. By understanding how these multidimensional factors interact, researchers can enrich their analysis of urban phenomena, thereby promoting the integration of broader societal dynamics into their work. This approach fosters deeper critical thinking and enhances the quality of academic contribution. By adopting this perspective, researchers can effectively contextualize their findings within the rich tapestry of societal influences, ultimately contributing to a more comprehensive understanding of urban research. This approach will facilitate a better understanding of historical dynamics and enable scholars to navigate the complexities of contemporary urban environments.

4.2.3. Context in Language Production and Interpretation

Building on a thematic analysis of John Flowerdew’s [12] insights into context-based texts, the findings reveal several critical benefits for ECRs regarding the role of context in discourse analyses. These benefits include a deeper understanding of how social, political, and ideological factors shape the discourse. They enhance awareness of power dynamics in discourse production and interpretation. They also improve their ability to critically analyze the implications of language in various contexts.

The study emphasizes that context is not merely a backdrop but an active force influencing the construction and reception of discourse. This understanding has significant practical implications for urban researchers, preparing them to examine the immediate and broader sociopolitical context in which urban discourse occurs. Recognizing the dynamic nature of context, researchers are encouraged to engage deeply with the societal influences that shape their research topics.

Additionally, the findings highlight how dominant narratives and power structures within discourse communities affect what is recognized as valid knowledge. For urban researchers, this insight stresses the necessity of being vigilant against marginalizing alternative perspectives, thus promoting more inclusive approaches to discourse analysis and fostering a sense of responsibility. Furthermore, understanding the complex interplay between context and language production allows researchers to account for the broader social implications of their findings. This understanding is particularly relevant for those examining urban issues influenced by public discourse, enabling a more nuanced interpretation of how language shapes urban experiences and policies.

4.2.4. Contextualizing Historical Narratives for Critical Thinking

Based on a thematic analysis of Carr’s [23] views on contextualizing historical narratives, the findings highlight numerous benefits for ECRs. These benefits include a deeper understanding of how societal and ideological contexts shape historical narratives, recognition of the evolving nature of historical interpretation, insights into the significance of temporal and social circumstances, opportunities for critically reassessing historical events, and enhanced potential for reflective analysis grounded in contemporary contexts. The findings emphasize that historical facts can only be fully understood by considering their contexts. This perspective has practical implications for urban researchers, highlighting the need to recognize how present-day societal and ideological shifts influence the interpretation of historical events. Rather than viewing history as a static record, this understanding encourages dynamic engagement with the factors that shape historical narratives.

The results show that historians’ contexts influence which facts are considered significant and how they are presented. This insight is valuable for urban research researchers, who must remain aware of the dominant narratives that may obscure alternative interpretations. This promotes more inclusive approaches to historical analysis, urging researchers to consider multiple perspectives in their evaluation of urban phenomena. The results confirm that this is a good choice for strong advocates of researchers to engage critically with the historical context shaping their work. By integrating these insights into their analyses, researchers can cultivate a more comprehensive and reflective understanding of the factors at play in urban development, ultimately fostering impactful academic contribution.

4.2.5. Impact of Cultural and Historical Contexts on Knowledge

Drawing from a thematic analysis of Peter Burke’s [74] insights into shared cultural factors, the findings emphasize the pivotal role of shared cultural and historical contexts in shaping collective knowledge. These contexts offer numerous benefits for ECRs of urban studies. These benefits include a deeper understanding of how cultural and historical contexts influence interpretations. They also involve recognizing the importance of situating events or texts within their contexts. Additionally, there are insights into the evolving nature of collective knowledge and opportunities for the critical analysis of historical phenomena. There is potential for interdisciplinary approaches that integrate cultural factors into urban research. This analysis found evidence that events and texts can only be fully comprehended within their appropriate temporal, social, cultural, and intellectual context. This perspective highlights the need for urban researchers to recognize how modern interpretations can alter the understanding of historical events. Researchers can enhance their analyses by avoiding anachronistic readings and engaging more deeply in the original contexts that shape these occurrences. This analysis found evidence that shifts in cultural and intellectual urban environments can significantly reshape our understanding of historical and artistic practices.

This insight is valuable for urban researchers, who should avoid interpretations that misrepresent the past. It advocates a contextual approach to historical analysis, urging researchers to consider multifaceted influences when interpreting urban development and transformation. Recognizing the evolving nature of context, this result sheds new light on how researchers can better account for how cultural shifts impact collective knowledge. This understanding is especially relevant for those investigating urban environments as it allows for a more comprehensive analysis of how historical practices inform contemporary issues. These findings encourage urban research scholars to engage critically with the cultural factors shaping their field, ultimately fostering a more reflective and nuanced approach to academic inquiry. Using this approach, researchers can cultivate a deeper appreciation of the complex interplay between culture and history in urban research, leading to more impactful and informed contributions to the discipline.

By adopting a contextualized approach to language analysis, ECRs can uncover the sociopolitical implications of urban discourse, contributing to more meaningful discussions within the field. The dynamic nature of context encourages scholars to remain flexible in their methodologies and to adapt their approaches as societal conditions evolve. This study advocates for critical engagement with the contextual factors influencing discourse, empowering ECRs to produce more informed and impactful contributions to urban research.

4.2.6. Influence of Social and Cultural Factors on Language Evolution

A thematic analysis of Traugott’s [11] insights into language evolution and contextual factors reveals how historical, social, and cultural influences shape linguistic change, offering numerous benefits to ECRs. These benefits include a deeper understanding of how context drives language evolution, recognition of the interconnectedness between societal structures and linguistic forms, new insights into the relationship between language and social change, expanded opportunities for interdisciplinary research, and enhanced potential for critical analysis of language within urban contexts.

The findings emphasize that context is not a passive backdrop in historical linguistics but an active force influencing linguistic change. This perspective highlights the importance of recognizing how shifts in cultural beliefs and societal structures shape language use and development. By considering these contextual factors, researchers can better understand how language reflects and responds to urban environments. Traugott’s [11] analysis illustrates, for instance, how changes in politeness strategies and the adoption of honorifics mirror broader social transformation. This insight underscores the need to approach language phenomena holistically as linguistic changes occur within specific environments and periods. This study warns against decontextualizing language, as doing so can lead to incomplete or misleading interpretations of the linguistic data. For future research, Traugott’s [11] findings should encourage researchers in language studies to explore the sociocultural contexts that underpin language evolution. This approach is essential for understanding the dynamic factors that shape linguistic development over time and can inform urban research by linking language use to broader social and cultural trends.

The insights from this analysis empower urban research scholars to critically engage with the contextual factors influencing language, fostering a more informed and reflective approach to academic inquiry. By incorporating these perspectives, researchers can enhance their understanding of how language functions in urban settings, leading to more nuanced and impactful contributions to this field.

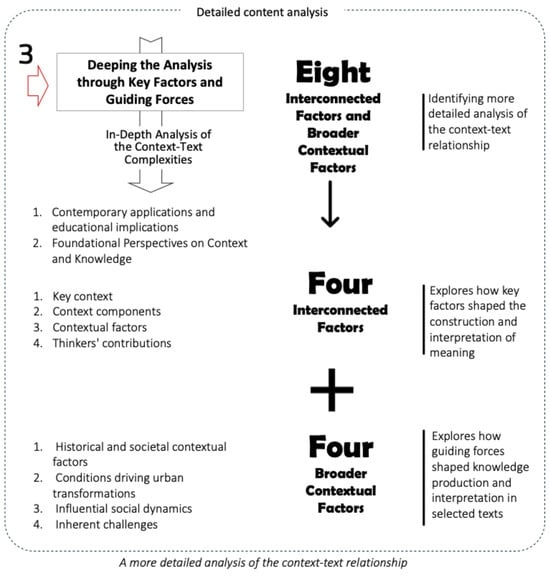

4.3. Stage 3: Deepening the Analysis Through Interconnected and Broader Contextual Factors

Building on the insights gleaned from Stage 1, we delved deeper into the context–text interplay using a two-step process, demonstrating that context is shaped by a diverse array of interconnected factors, including societal influences, power, and social dynamics. Across various theoretical approaches, context has emerged as a dynamic construction shaped by historical and societal contextual factors. These contextual elements influence the production of meaning and play critical roles in interpretation and application. Examining these factors across different scholars emphasizes the centrality of social, historical, and political environments in shaping understanding. This finding highlights the fluid context evolving in nature as it interacts with broader contextual factors.

Exploring the four interconnected factors—focusing on concepts, components of context, contextual factors, and thinkers’ contributions—provides comprehensive guidance for understanding how context functions in different disciplines. Each theme captures a distinct aspect of the context’s role in shaping interpretation and meaning-making and identifying broader contextual factors that define context–text interplay. These factors reveal the influence of historical and social contextual factors. In addition to influential power and social dynamics, urban development conditions constitute another key factor, with inherent challenges and limitations.

These studies stress the complexity of the context and highlight the multidimensional influences that govern its interpretation. The results of this analysis focus on two main issues, as illustrated in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Four interconnected factors and four border contextual factors.

4.3.1. Exploring the Four Interconnected Factors

Our extensive content analysis of six carefully selected literature samples yielded vital insights into the multidimensional and dynamic nature of the context. This study reveals that context is not a static backdrop but rather a dynamic construct that actively shapes interpretation, knowledge production, and the evolution of discourse. By mapping scholarly perspectives across diverse discourses, including hermeneutics, historical inquiry, discourse analysis, and linguistics, we identified four interconnected factors that elucidate how context functions as an integral force in understanding texts, historical events, and linguistic phenomena.

In our investigation, we first observed that context is conceptualized in various ways across the examined discourses. Despite these differences, scholars have reached a consensus that context plays a pivotal role in shaping interpretations. For instance, van Dijk [69] argues that context is a cognitive construction molded by societal norms and power structures. He contends that these cognitive contexts deeply influence discourse interpretation. This perspective is reinforced by Rogers [70] who posits that sociopolitical structures and their pressures significantly affect historical events. Both perspectives emphasize that context is central to constructing and understanding knowledge.

Flowerdew [12] further elaborates on these ideas by stating that context includes a variety of dimensions—social, political, historical, and ideological—that influence both the creation and interpretation of discourse. His work emphasizes that context should be viewed not as a single factor but as a collection of interconnected elements that shape how meaning is produced. Similarly, Carr [23] illustrates that the interplay between a historian’s contemporary context and historical events bridges the past to the present. Burke [74] reinforced this notion by suggesting that context represents an interaction between various components that evolve alongside shifting societal norms. Traugott [11] challenges traditional views by framing context as an active force in linguistic development, emphasizing that language co-evolves with its social and cultural environment.

These foundational insights underscore the diversity of component-shaping contexts. Van Dijk [69] identified cognitive constructs, such as knowledge schemas, social roles, and power relations, as central to understanding the context. These constructs, embedded within societal norms, critically influence discourse interpretations. Rogers [70] extends this understanding by emphasizing that sociopolitical structures, including political ideologies and broad societal transformations, are crucial for historical knowledge. Likewise, Flowerdew [12] focuses on power dynamics, noting that political authority and ideological control are significant elements that shape the production and reception of meaning within a sociopolitical landscape.

Our analysis further demonstrates that Carr [23] emphasizes the historian’s role in interpreting facts within a temporal, social, and ideological context. He underscores that socioeconomic conditions and evolving societal norms are central to historical interpretation. Burke [74] examined the interplay between temporal, social, cultural, and intellectual components, arguing that these elements collectively and dynamically influence historical and cultural interpretations. Traugott [11] added another dimension by discussing how the sociolinguistic environment and cultural practices drive linguistic change, highlighting the active role of these factors in shaping language over time.

These findings confirm that the contextual factors identified by theorists illustrate the complex influences that shape meaning and interpretation. Van Dijk [69] stresses that cognitive dimensions such as social status and power relations are fundamental to discourse interpretation. Rogers [70] draws attention to the sociopolitical structures that govern historical narratives, arguing that political ideologies and social hierarchies are the key determinants of how history is understood. Flowerdew [12] focuses on social relations and ideological control, asserting that these factors influence discourse in its broader sociopolitical context. Carr [23] also discusses how the interaction between historical and contemporary contexts, encompassing socioeconomic conditions and ideological discourse, shapes historical interpretation. Burke [74] emphasized that social norms, intellectual movements, and cultural context influence how historical and cultural phenomena are interpreted. Simultaneously, Traugott [11] highlighted the nature of linguistic change driven by the interplay between social hierarchies and cultural practices.

The convergence of these perspectives reveals that context is not only a multidimensional construct, but also one mutually influential with the various cognitive, sociopolitical, and linguistic factors at play. This dynamic interplay shapes meaning-making, interacting with cognitive context and ideological influences to determine the resulting interpretations and values attached to a text, event, or idea. The synthesis of cognitive, sociopolitical, ideological, and linguistic perspectives underscores the inherent complexity of context and its integral role across different fields of study.

An additional finding of our analysis is that the critical points raised by scholars from 2008 to 2023 underscore the complexities and challenges inherent in interpreting contexts. For example, van Dijk [69] points out that cognitive constructs, such as social status and power relations, are crucial for discourse interpretation and present significant challenges when researchers navigate the interplay between these cognitive context and broader sociopolitical influences. Rogers [70] reinforces this notion by examining how sociopolitical structures shape historical narratives, suggesting that political ideologies and social hierarchies often constrain interpretations. Flowerdew [12] deepens this argument by asserting that context is intricately intertwined with power dynamics, ideological control, and meaning-making processes. His work demonstrates that separating these influences from discourse is challenging yet essential for understanding how meaning is produced. Burke [74] warns against the risks of decontextualization, arguing that removing events from sociocultural settings leads to oversimplified interpretations that fail to capture the richness of historical and cultural phenomena. He emphasized that continuous reassessment of interpretations is necessary to fully appreciate the evolving nature of social norms and cultural practices. Similarly, Traugott [11] examined how the interplay between social hierarchies and linguistic communities drives language evolution, highlighting the importance of considering broader social and cultural influences when analyzing linguistic developments.

Overall, the results of our study demonstrate that the context is a dynamic and multifaceted factor shaped by historical and societal factors. This interplay is essential for determining how meaning is constructed and interpreted in various fields. Neglecting these influences can lead to oversimplified and inaccurate interpretations, weakening the scholarly analysis. As our literature examination shows, scholars consistently emphasize the challenges of capturing the context’s fluid and dynamic nature, especially when conducting literature reviews. Researchers must engage with multiple perspectives; critically examine the historical and social contexts of the studies they review and recognize how power dynamics and language influence knowledge construction. By adopting a more contextualized approach, scholars can effectively bridge the gap between context and text, fostering a more robust and nuanced understanding of the research landscape.

In short, our comprehensive analysis of these six literature samples confirms that context, far from mere background, is a vital and active element in the production and interpretation of knowledge. The convergence of insights from cognitive, sociopolitical, ideological, and linguistic perspectives highlights the inherent complexity of context and emphasizes its indispensable role in scholarly inquiry. This dynamic interplay shapes the meaning-making process and has significant implications for academic research, particularly in urban research, where historical and societal factors are continuously at work. By adopting a more nuanced and contextually grounded approach, researchers can enhance their analysis, produce more accurate interpretations, and ultimately contribute to a deeper and more precise understanding of urban phenomena. Our findings also advocate for a critical reexamination of how context is conceptualized and integrated into academic discourse—a reexamination that promises to transform scholarly practice across disciplines.

4.3.2. Identifying the Four Broader Contextual Factors

Our analysis emphasizes that a constellation of interrelated factors shapes the relationship between context and text, influencing how meaning is constructed and interpreted. From our examination of critical scholars, four broad contextual factors emerge to understand this interplay: historical and societal influences, urban developmental conditions, power and social dynamics, and the inherent challenges in capturing the context.

First, historical and societal contextual factors play a pivotal role in shaping the creation and interpretation of texts. Scholars, such as Carr [23], have shown that societal norms and historical consciousness directly affect the circulation and reception of knowledge. For example, how historical events are framed within specific cultural contexts can alter interpretations of past events. Similarly, Flowerdew [12] points out that sociopolitical tensions embedded within a society’s fabric are crucial in determining how texts are understood. These insights confirm that context is not merely a backdrop but an active force molding the intellectual landscape.

Second, conditions related to urban development constitute another key factor. Urban research and historical analysis have revealed that the physical and built environment and its transformative processes significantly influence societal practices. Rogers [70] illustrates this with an example of how the expansion of the British navy in Georgian Britain affected societal practices such as impressment, demonstrating that urban transformations have far-reaching implications. Moreover, as analyzed by Flowerdew [12], political speeches and public discourses often reflect responses to urban changes, highlighting how discourse can shape the built environment.

Third, the analysis identifies power and social dynamics as critical in construction. Van Dijk [69] emphasizes that cognitive constructs, such as social status and power relationships, play a central role in interpreting discourse. In this view, power is not only embedded in the content of texts but also in the structures that govern their production and dissemination. Flowerdew [12] further contended that political authority and ideological dominance are key elements that determine how knowledge is produced and received. These dynamics underscore the importance of interrogating whose voices are privileged in the scholarly narrative and how alternative or marginalized perspectives might be sidelined.

Fourth, our findings reveal the inherent challenges and limitations of interpreting contexts. Scholars, such as Burke [74], caution against the risks of decontextualization, arguing that stripping events from their sociocultural and historical settings can lead to oversimplified and even misleading interpretations. Traugott [11] adds that capturing the context’s fluid and evolving nature, especially in linguistic change, requires constant reassessment and methodological flexibility. These challenges remind us that the context is not fixed; instead, it is continually in flux, necessitating that researchers remain vigilant and adaptive in their analysis.

Historical and societal influences, urban developmental conditions, power and social dynamics, and inherent interpretative challenges demonstrate the complex interplay between social structures, historical realities, and intellectual context. This multidimensional view reinforces that meaning is constructed through various cognitive, social, and ideological factors. Neglecting these dimensions can lead to an incomplete or biased understanding of how knowledge is produced and communicated.

Our study confirms that context is an active, multifaceted construction across all six examined sources. The insights derived from this comprehensive analysis have practical implications for urban research. Researchers are urged to recognize that context dynamics—whether in historical narratives, urban transformations, or power-laden discourses—are essential for producing robust and nuanced interpretations. Scholars can bridge the gap between empirical observations and theoretical reflections, enriching academic discourse and practical understanding.

In short, identifying these four broader contextual factors illuminates the inherent complexity of the context and highlights the necessity of a more integrative and critically reflective approach to academic writing. By engaging with these factors, researchers are better equipped to capture the ever-evolving nature of knowledge production, ensuring their interpretations remain relevant, nuanced, and deeply grounded in the urban environment.

4.4. Stage 4: Five Fundamental Guidelines for Creating High-Quality Academic Writing

By showcasing examples from diverse academic fields, such as social sciences, discourse analysis, historical studies, and linguistics, the findings illuminate the power of this interdisciplinary approach in providing practical guidance. The insights presented in this study were designed to help ECRs craft contextually aware texts that make meaningful contributions to their academic writing. The discussion was structured around four stages, with two preliminary steps, five methodological steps, and five essential guidelines, to strengthen the literature review process.

To address the critical relationship between context and text, this subsection seeks to bridge the gap identified in the literature on academic writing, particularly in the literature reviews. By exploring the dynamic role of context, we aim to illuminate how it influences the construction and interpretation of knowledge. Our findings reveal six critical insights into the role of context, as represented by six influential scholars: van Dijk [69], Rogers [70], John Flowerdew [12], E. H. Carr [23], Burke [74], and Traugott [11]. Although these scholars have focused on different areas, they agree on the significance of context as a crucial and evolving factor that shapes knowledge and interpretation.

4.4.1. Treat Context as Dynamic and Multidimensional

High-quality academic writing should reflect the dynamism by situating research in historical, social, and cultural settings. An essential finding of this concept study is that five scholars across various disciplines agree on the dynamic role of the context in shaping knowledge production and interpretation. Two core insights emerged. First, context is not a static backdrop but a dynamic, evolving construction influenced by historical and societal contextual factors. Second, although all scholars acknowledge the importance of context, they differ in their specific areas of emphasis. For example, van Dijk [69] treats context as discipline-specific, focusing on how it operates within fields, whereas Rogers [70] highlights its interplay with historical events. Flowerdew [12] examines how ideological, social, and political dimensions shape discourse, whereas Carr [23] stresses historians’ responsibility to integrate temporal and ideological contexts. Burke [74] explored cultural and intellectual dimensions, while Traugott [11] underscored the social and cognitive factors that drive language evolution.

These diverse perspectives stress that context is an interpretative and active force influencing scholarly inquiry. Recent research by Nguyen Minh Tri [82] and Esposito [21] reinforces that discourse is inextricably linked to social and cultural surroundings. This view resonates with Flowerdew’s [12] critical discourse analysis. Moreover, Popa [83] demonstrates how historical narratives are co-shaped by historians and context, suggesting a more interactional meaning-making model. Despite methodological variations, the consensus is clear: the context is multidimensional, and rigorous consideration is vital for robust and nuanced academic analysis.

4.4.2. Balance Shared Recognition and Diverging Focus

An essential finding of this subsection reveals that, while these five scholars differ in their specific focus areas, they converge on the fundamental importance of the context. This shared recognition underscores a critical finding: context is not a static or peripheral element but a dynamic and integral component that profoundly shapes the interpretation of information. Context is an evolving construct that is influenced by historical and societal factors. However, despite this shared emphasis, the application of context varied significantly. This diversity of approaches, from disciplinary knowledge [69] to historical events [70] discourse [12], historical interpretation [23,74], and language evolution, stresses the multifaceted nature of context and its diverse applications across fields [11].

Context is not merely a backdrop but an active element that shapes and is shaped by the phenomena it surrounds [20]. Our analysis identified four essential determinants for building conceptual guidance: historical and societal contextual factors, surrounding conditions leading to urban transformations, influential power and social dynamics, and inherent challenges and constraints. These factors collectively contribute to a nuanced understanding of context, encompassing not only the historical and societal contextual factors influencing knowledge production but also how contextual factors [9]—such as urban prestige, identity, or morphology—shape or are reflected in urban design and the planning literature [84]. By acknowledging the specific context of previous studies, researchers can better understand the limitations, biases, and assumptions that may have influenced their findings [7,85].

Despite its significance, integrating context into literature reviews remains challenging. A common obstacle is the tendency to focus solely on the textual content of research articles, neglecting the broader circumstances influencing their creation. This narrow focus can lead to a superficial understanding of the literature, limiting researchers’ ability to evaluate and synthesize existing knowledge critically. Researchers should adopt a more nuanced and critical approach to bridge this gap by recognizing the inseparable link between the historical context and epistemology. As Gattinara [75] notes, the historicization of epistemology and post-embolization of the history of science underscores the evolving nature of knowledge. This finding enhances our understanding of the relationship between the context and text. Emphasizing context’s dynamic and multidimensional nature challenges the idea that context is merely a backdrop for understanding urban phenomena. Instead, context is an active and integral component that shapes knowledge production and interpretation.

4.4.3. Explore Interconnected and Broader Contextual Factors

Our analysis identified four broad contextual factors central to understanding how context shapes both the production and interpretation of knowledge. These factors—historical and societal influences, urban developmental conditions, power and social dynamics, and the inherent challenges of capturing context—are closely tied to the key themes of this study: a focus on core concepts, components of context, diverse contextual factors, and contributions of leading scholars.

The scholars examined in this study highlighted the inherent challenges of fully capturing the complexity of a context, mainly as it evolves in response to societal and environmental changes. By analyzing texts from the perspective of these interconnected factors, this study reveals the nuanced role of context in shaping scholarly work. This approach underscores the benefits of examining how societal factors, urban transformations, and power dynamics influence knowledge production and emphasizes the significant challenges of interpreting contexts across diverse fields. These challenges call for thorough considerations to address the complex nature of knowledge creation and interpretation.

Scholars acknowledge that context is not a static backdrop but a dynamic, evolving construct shaped by historical and societal contextual factors. Societal influences are pivotal in determining how disciplines such as history, linguistics, and urban research define and interpret contexts. Urban developmental conditions, power, and social dynamics affect how knowledge is produced and received. However, each scholar’s emphasis on context differs. Van Dijk [69] treats context as discipline-specific, whereas Rogers [70] highlights its role across historical periods. Flowerdew [12] explores how ideological, social, and political dimensions shape discourse. Carr [23] underscores the historian’s responsibility to incorporate temporal and ideological factors. Furthermore, Burke [74] examines cultural and intellectual dimensions. Traugott [11] focuses on the social and cognitive factors that drive language evolution.

Recent studies validated the importance of contextual analysis in knowledge production. Kaplan, Cromley, and Balsai [86] highlighted the critical role of contextual factors in educational research, emphasizing their impact on the implementation of evidence-based practices. Snyder [85] provides a comprehensive overview of how a literature review, as a research methodology, can illuminate the complexity of contextual factors and their influence on knowledge production. These studies not only reinforce the significance of this research but also demonstrate the alignment of recent findings with broader scholarly discourse, keeping readers engaged with the field’s current state.

According to our investigation, knowledge creation and interpretation should be multidimensional, and can be achieved by integrating historical, societal, urban, and power-related contextual factors. However, the insights gained from this multi-layered investigation provide a robust foundation for future research, ensuring that the evolving nature of the context remains a central focus in scholarly inquiry.

4.4.4. Highlight the Added Value of Contextual Factors

With its interdisciplinary approach, this study highlights the significant advantages of analyzing texts through four interconnected themes: concepts, components, contextual factors, and critical points. By exploring these elements, ECRs can achieve a more nuanced understanding of how texts are shaped by their intellectual and disciplinary contexts, thereby providing a conceptual guide for interpreting knowledge production. The concept of context, for instance, demonstrates that fundamental ideas within a text are not isolated, but are deeply influenced by historical and societal contextual factors.

Examining concepts within their broader disciplinary context allows researchers to observe how theoretical constructions evolve in response to shifting societal needs and intellectual trends. This approach underscores the fluidity of knowledge, offering critical insights into how specific ideas gain prominence while others recede. Understanding concepts in their broader context fosters a deeper comprehension of how internal theoretical developments and external pressures shape fields of study. Nussbaum [71] similarly argues that it is essential to have a broad and critical understanding of history and culture to sustain democratic societies. This claim aligns with Carr [23] and Burke’s [74] perspective. Nussbaum [71] emphasizes the role of the humanities in fostering societal understanding and critical engagement, which resonates with Burke’s [74] focus on the fluidity of the historical context and Carr’s [23] view of how historical knowledge is shaped by its broader environment.

However, components offer a granular view of the text by dissecting its structure, such as methods, arguments, and evidence, thereby illuminating how these elements function together to reflect contextual influences. The interplay between different components often reveals underlying assumptions about a text’s intended audience or methodological foundations. For instance, a close examination of the arguments and evidence within a text may reveal biases or gaps shaped by the sociopolitical environment in which the work was produced. This level of analysis enables critical evaluation of a text’s reliability and scope of knowledge, highlighting the value of deconstructing a text into its constituent parts. This perspective finds resonance in Dilthey’s [43] and Gadamer’s [45] hermeneutical approach, where the interpreter’s “horizon” profoundly shapes the meaning derived from the historical material.