Abstract

Skill shortages have become obvious in many European countries during the last few years, when specific sectors required more skilled personnel. In this article, we analyse the ongoing discussion regarding whether skill shortages can be addressed by hiring third-country nationals from abroad or reskilling or upskilling job seekers inside the country. The analysis is based on EMN studies, official documents, and other publicly available sources and focusses on Luxembourg as a case study. It describes the challenges faced by Luxembourg as a small but economically viable country and which pathways are used to attract skilled workers.

1. Introduction

Skill shortages are becoming a serious problem for the competitiveness of the European Union. The European economy is losing competitiveness as its workforce ages [1], and birth rates are declining in most EU countries [2]. Among European employers, 75% report difficulties in hiring skilled workers, a challenge that threatens not only economic growth but also progress in other policy priorities (e.g., increasing housing, meeting climate goals, keeping pace with innovative technologies and artificial intelligence) [1]. Another concern is that in some countries, the unemployment rate continues to increase, even as available jobs remain unoccupied. In the EU, 30.9% of third-country nationals born outside of the EU have a higher education degree, but a large percentage (34.9%) of them work in less skilled occupations that do not require tertiary education [3,4]. Working conditions (including factors such as wages, atypical schedules, and job strain) may also play a significant role in causing these shortages in certain sectors (e.g., health and long-term care).

As one of the founding members of the European Union, the case of Luxembourg is quite unique. It is the second smallest country in the EU (2586 km2) [5], has a very small population (681,973 inhabitants with a density of 263.7 inhabitants per km2) [6], and has the largest GDP per capita in the European Union (USD 146,820 in comparison to USD 46,800 for the EU overall) [7]. The country is a landlocked state bordered by Belgium, France, and Germany [6]. Even though, being small Luxembourg has a multilingual system—Luxembourgish (official language), French and German (administrative languages), and English (lingua franca)—that is unique within the European Union, as all these languages are used throughout the entire country and not in geographically distinct regions, unlike in other countries (e.g., Belgium).

Its original wealth began with the discovery of iron ore deposits in the 1840s, which allowed a transition from an agriculture-based economy to an industrial economy (construction of foundries and steel mills) [8], which later shifted to a tertiary economy based on banking and finance [9]. However, due to the small population and the lack of sufficient qualified workforce, the Luxembourgish economy has always depended on foreign workers [10]. The labour market workforce is composed mainly of foreigners (73.8%), including residents (130,631 representing 26.7%) and cross-border workers (230,098, representing 47%) coming from the three neighbouring countries (the so-called “Greater Region”), which is the largest cross-border region in Europe (excluding Switzerland). This composition of the Luxembourg labour market is completely different from the rest of EU Member States. Cross-border workers coming from the neighbouring countries are confronted with long commuting times and increasing travel costs that generally affect the work–life balance. Also, the profiles that Luxembourgish companies are looking for are scarce in the Greater Region (either because they cannot be found or because there is internal competition with the other countries for the same profiles), and this is one of the reasons why more third-country nationals-people born outside the European Union-are entering the labour market [11]. This situation has led Luxembourgish companies to change their perspectives and start looking for a workforce outside the Greater Region and the EU. Another factor that will be affecting the labour market is natality. Since 2015, even though the natural evolution of the Luxembourgish population has been positive, this is mainly due to foreign children born in the territory, as the natality balance of nationals is mostly negative (only in 2016, 2021, 2022, and 2024 was the natality balance slightly positive) [12]. According to these trends, migration appears as a policy solution to labour shortages. However, being a tertiary economy, foreign workers (either coming from abroad or already residing in the country) will be required to have a specific set of skills in order to access the labour market. This factor clearly reduces the number of foreign workers willing to apply to Luxembourg. In addition, the artificial intelligence strategy of the Luxembourg government targets specific sectors of the economy that are expected to undergo substantial transformation [13]. This will require significant upskilling and reskilling of the existing workforce in these sectors [14], thereby making access to the labour market more challenging for foreign workers. Indeed, several positions in banking, insurance, and capital markets may be at risk of displacement due to the increasing integration of AI technologies [14].

“Skill” is a fashionable term with an imprecise definition. The authors [15] reviewed and clustered four types of skills “as education”, “as occupational classification”, “as a function of income and occupation”, or “as on-the-job training and work experience”.

Dotsey [16] shows that the demand for medium and highly skilled workers in particular has increased in recent years and that competition among the most talented has intensified. At the same time, skill shortages and skill mismatch have become more obvious in several sectors. Skill mismatch is a matter of employability and the training required to fill open positions. Skill shortages and skill mismatch (realised vs. self-reported, overeducated vs. undereducated, and overskilled vs. underskilled) both exist on different scales (like country, firm, or individual), subject to cyclical and structural factors [17,18]. The literature on the shortage of highly skilled labour is extensive, addressing subjects like brain abuse [19]; labour market competition [20]; gender [21]; specific sectors like the tech industry [22], healthcare [16,23], and the culinary field [24]; and regional contexts, e.g., Canada [15,19,22], Japan [25,26], and Europe [20,27,28].

In the face of skill shortages and skill mismatch, migration is often seen as a potential solution or a means of quickly increasing the number of skilled workers. This would require that the incoming workforce is able to start working immediately; however, unrecognised qualifications, bureaucratic procedure, and language barriers often hamper the direct integration of skilled workers. The academic literature has examined skill shortages and skill mismatches, yet there is limited comparative information on this issue across EU Member States. For this reason, the Steering Board of the European Migration Network decided in 2024 to launch a study entitled “Fostering Sustainable Labour Market Integration of Migrants: Skills Matching Policies and Instruments”, which will be published in 2026.

This article presents an analysis of the ongoing discussion as to whether skill shortages can be addressed by hiring “third-country nationals” from abroad or reskilling/upskilling local job seekers (especially legally residing third-country nationals, beneficiaries of international protection, or asylum seekers). To concretise the issue, we focus on the case of Luxembourg as it has a unique position inside the European Union but can be seen as a laboratory due to its specificities. Finally, we investigate whether the artificial intelligence can help address these problems or if it will have a negative social impact.

2. Materials and Methods

This study comprises an analysis of all policy papers of the Luxembourg government and other national stakeholders, legal documents, statistics, the network work of the European Migration Network (EMN), and several EMN studies, mainly the Luxembourg national report of the EMN Studies “Labour Migration in times of labour shortages in Luxembourg (January 2021–June 2024) (January 2025)” and “Fostering Sustainable Labour Market Integration of Migrants: Skills Matching Policies and Instruments (October 2025)” as well as the EMN–OECD Inform entitled “New and innovative ways to attract foreign talents in the EU (March 2025)”. As there is no direct statistical data available it was decided to do a text-based analysis of the information available, and no new empirical data was produced. Nevertheless, the existing data was analysed combined with the discussions the authors are part of on European and national level.

3. The Case Study: “Luxembourg”

In a tertiary economy such as that of Luxembourg [29], skill requirements are indispensable. The government policy is to attract and retain talent [30]. As a result, third-country nationals can apply for skilled and highly skilled positions, reducing the number applying for low skilled positions.

3.1. Unemployment and Skill Shortages

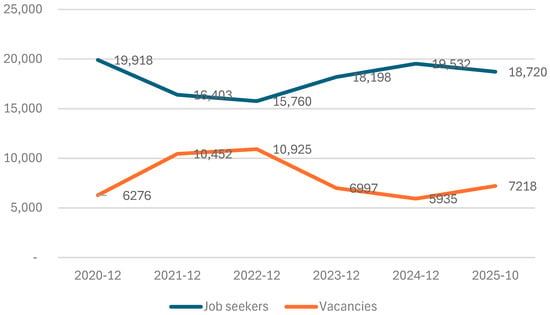

Employers across the European Union are complaining of labour shortages that risk affecting their productivity and competitiveness [1]. Nevertheless, the level of unemployment continues to increase, even though a significant number of positions remain vacant, demonstrating skill shortages. A more concrete example is the case of Luxembourg, in which the unemployment rate continues to increase (reaching 5.9% in October of 2025) despite job vacancies (7218 vacancies at the same period) [31]. This is a phenomenon that has been recurrent since several years as it is seen from the figure below.

It was determined that some of these vacancies (see Figure 1) in skilled positions are not filled by job-seeking individuals receiving unemployment benefits but by workers transitioning from one job to another (earning better wages and conditions) [4]. This situation creates a vicious circle, as the moving employees leave another position vacant. Most EU Member States are in a similar situation, as EU employers struggle to find candidates with suitable qualifications and skills to fill these vacancies [32]. Skills shortages are one of the most significant obstacles, especially for small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), in developing business activities [4], as large enterprises have the human and economic resources to fill these skill shortages.

Figure 1.

Number of Job seekers and vacancies (December 2020–October 2025). Source: ADEM, Chiffres-clés, Décembre 2020, 2021, 2022, 2023, 2024 & Octobre 2025.

3.2. Different Pathways Found in the Analysis

One solution to this problem is to take advantage of cross-border mobility and migration recruitment [4].

3.2.1. Recruiting EU and Cross-Border Workers vs. Foreign Workers

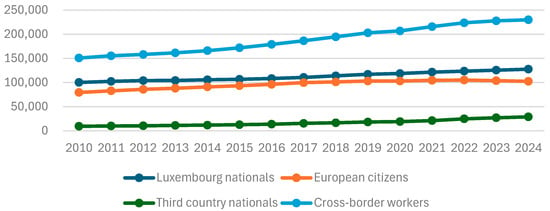

As mentioned above, Luxembourg has a very small population. Nevertheless, as a tertiary economy based on banking, finance, and services, it requires a skilled workforce to operate efficiently. This is the reason why the cross-border mobility of EU citizens has resulted in success for Luxembourg, which attained 229.919 individuals from 1995 to the fourth quarter of 2024, representing 46.9% of the total workforce [32], this growth has begun to stagnate due to (1) long commuting times, which have recently increased due to the temporary reintroduction of border controls by Belgium, France, and Germany [33], (2) wage increases implemented by neighbouring countries to maintain their native workforce, and (3) new fiscal agreements signed between the neighbouring countries and Luxembourg [34]. The number of EU citizens residing in Luxembourg also declined between 2022 and 2024 (see figure n° 2. On the contrary, the number of third-country nationals have increased by 202% in the last 15 years and by 16.1% since 2022 [32].

The stagnation of the pool of skilled cross-border workers (due either to the scarcity of certain profiles or to the policies implemented by neighbouring countries to retain them) has obliged Luxembourg employers to search for workers outside the European Union and, in some cases, even beyond Europe. This situation is, to a certain extent, reflected in the increase in the number of third-country nationals coming to work in Luxembourg in the last five years, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Luxembourg labour market, disaggregated by nationality and place of residence (2010–2024) [32]. Note: the numbers reflect the situation in the Q.4 of each year.

Nevertheless, the use of migration recruitment routes poses serious problems for Luxembourg employers (especially SMEs) for the following reasons: administrative barriers, recognition of qualifications and skills required, and language skills. These obstacles to accessing the labour market affect not only employers but also third-country nationals: the former need workers to start as soon as possible, while the latter often cannot afford to wait for a long period before obtaining remunerated employment.

Administrative Barriers

Through the EU Pact on Migration and Asylum, the European Commission promotes legal pathways via Talent Partnerships with certain third countries and the EU Talent Pool, which is an EU-wide platform to facilitate international recruitment in sectors with labour shortages in EU Member States [35]. However, in 2023, less than 10% of EU employers recruited candidates from outside of the EU [4].

Even though the requirements for highly qualified workers (European Blue Card) were simplified with the revamp of the Blue Card Directive [36], it did not solve the problem of skill shortages for SMEs as they cannot pay the minimum threshold salary required for a highly skilled worker (in the case of Luxembourg, this is EUR 63.408 per year [37]) [38].

In this situation, if an SME would like to hire a third-country national, it should follow the procedure established by the Immigration Law [39]. Before recruiting a salaried worker, the company must make a declaration of vacancy to the Luxembourg Employment Agency (ADEM). This declaration allows ADEM to check whether there is a suitable candidate available in the local or EU market [40]. If ADEM cannot offer a candidate within three weeks, the employer is allowed to sign a work contract with a third-country national [40]. Once the deadline has passed, the employer must request that ADEM issue a certificate granting the right to hire a third-country national. The employer must then sign a dated employment contract with the third-country national. This contract must state that it is “subject to the employee obtaining an authorization to stay for salaried worker/work permit” [41].

The Labour Market Test [40], as originally approved by the legislator in 2012, was considered a waste of time for companies wishing to hire a qualified employee whom ADEM could not provide, as employers had to wait one month to receive a decision, even though ADEM was often able to determine within approximately one week that no registered jobseeker was available for the required profile [42]. This procedure was recently simplified for vacancies in sectors with labour shortages [43]. To address these challenges, the government has introduced new mechanisms aimed at responding more effectively to structural labour shortages. In this context, it establishes a list of sectors experiencing significant recruitment difficulties, based on the following criteria: 1° the number of positions declared to ADEM during a calendar year for the same occupation; 2° the number of jobseekers registered with ADEM who have applied for a position in that occupation; and 3° the number of positions declared to ADEM for which the Agency was unable to identify any candidate matching the vacancy profile [44]. This classification allows policymakers to better identify occupations under strain and to adapt labour migration policies accordingly. The list (see Table 1) is drawn up annually by ADEM during the first quarter of the year following the calendar year to which it refers and is published in the Official Journal of the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg [44]. ADEM also uses the list of occupations in severe shortage to identify the skills employers need and to offer targeted training to jobseekers in those fields [45].

Table 1.

Occupations in severe shortage, 2022–2024.

In such a case, the application for the certificate can be submitted by the employer directly when declaring a job vacancy to ADEM or later, at any time during the validity period of the job offer. If the declared position corresponds to an occupation on the high-shortage list [44], the certificate is issued within five working days of the acknowledgment of receipt [46]. This simplification has proven to be quite efficient; ADEM reported that with this simplified system, the issuance of foreign labour certificates increased by 20% compared to the same period in the previous year [40,47]. Furthermore, the share of certificates issued for occupations in short supply is at around 75% of the total, demonstrating the considerable impact of this strategy on the hiring of third-country nationals [48].

Once the certificate has been issued and the contract with the employer has been signed, the employee must file the application with the General Department of Immigration (DGIM) or at the Luxembourg’s diplomatic or consular representation in the Member State, which represents Luxembourg’s interests in the country of origin. This application must contain details of the applicant’s identity and must be accompanied by (a) a copy of their passport; (b) their criminal record or an affidavit from their country of residence (not older than six months), (c) their curriculum vitae; (d) copies of their diplomas or qualifications; (e) a copy of the employment contract mentioned above; and (f) the certificate issued by ADEM [41]. If these documents are not drafted in German, French, or English, an official translation by a sworn translator is required [41].

The application will not be reviewed until it is considered complete by the case officer [41]. The Minister in charge of Immigration and Asylum must make the decision in a maximum of four months from when the application was submitted [39]. If there is no answer, the application is considered denied [39].

This procedure must be finished before the employee enters the territory. This is burdensome for the employer, as it is a long process, and the employer cannot wait four to six months to fill the position without a guarantee that the individual can be hired. This situation makes the recruitment of foreign workers unattractive for employers, especially in sectors where there are no labour shortages.

Another significant problem is that the employee must prove that they have appropriate accommodations in order to receive the residence permit [49]. The housing crisis in Luxembourg [30,50] presents an additional challenge, as it makes finding an adequate accommodation difficult. If the TCN does find accommodation, it can cost up to 50% of his/her salary [51]. On its own, this issue can dissuade TCNs from immigrating to Luxembourg.

For companies in Luxembourg, recruiting third-country nationals coming from their country of origin is a challenge due to the bureaucracy involved, the cost of recruiting, the duration of the procedure, and the lack of predictability regarding the result.

Recognition of Diplomas and Qualifications

Another challenge is the recognition of diplomas or qualifications [47]. The recognition of diplomas is a continuous challenge in Luxembourg, as professional qualifications obtained outside of the EU must be recognised as equivalent to the qualification required in Luxembourg to access (a) certain liberal professions (e.g., architects, landscape architect/landscape engineer, accountant, patent attorney, chartered accountant, surveyor, consulting engineer in the construction sector, and town and country planner) and professions in the commercial and craft sectors [52]; (b) healthcare professions (e.g., medical professions other than physician, including social worker, surgical assistant, medical laboratory assistant, radiologic technician, dietician, occupational therapist, nurse, anaesthetic and intensive care nurse, paediatric nurse, graduated nurse, psychiatric nurse, laboratory assistant, physiotherapist, speech therapist, orthoptist, osteopath, curative teacher, chiropodist, psychomotor therapist, and midwife); and (c) socio-educational professions.

The main issue is not the nationality of the applicant but the nationality of the diploma. Recognition is simplified for diplomas issued by signatories of the Paris Convention and the Lisbon Conventions [53]. If the diploma was issued in a third country that is not a signatory of these conventions, the situation becomes more complicated. Recognition of the equivalence of diplomas or professional qualifications is conducted on a case-by-case basis, as a license to practice requires recognition of the equivalence of professional qualifications in relation to equivalent diplomas in Luxembourg [54]. This evaluation is carried out by the Department for the Recognition of Diplomas. The situation is complex, as the applicant must prove that the qualification obtained in a third country is recognised by another Member State or provide proof of three years of professional experience in that Member State [54]. This issue is aggravated by differences in the education systems of the country of origin and Luxembourg [55]. According to a recent ADEM report [56], jobseekers with high-level diplomas who might meet job requirements may face employers who are unfamiliar with foreign schools or programs and, as a result, may not fully trust the value of the applicant’s qualifications. Additionally, experience and knowledge gained outside the EU are not always transferable to Luxembourg, particularly in fields such as accounting or the financial sector, where knowledge of local regulations and standards is crucial [47]. Also, regarding regulated professions, ADEM highlights that in sectors such as health and social care (e.g., educators, social workers), professions are generally regulated and require formal recognition of foreign diplomas, and certification of language proficiency [56].

Processing can take between two and six weeks, but this time can be extended to three months. If the application is rejected, the applicant can make an appeal, but the final decision can take up to several years.

In most cases, third-country nationals legally residing in Luxembourg, whether independently as migrants or as beneficiaries of international protection, find themselves in positions for which they are over-or underqualified, as the process of recognising qualifications and experience is so complicated [55].

These mismatches between the third-country national’s real qualifications and the employment they can obtain result in a less skilled occupation with lower pay [57] for the migrant, but they also affect the employer and the economy in general, as they impact state revenues, productivity, innovation, and economic growth [18]. The fact that a legally residing migrant that cannot access the labour market because their qualifications are not recognised can also affect unemployment [58].

Language Skills

Language skills represent another obstacle [47]. In Luxembourg, language proficiency is essential to accessing the labour market [55]: there are three official languages (Luxembourgish, French, and German) [59] and one lingua franca (English) [55,60]. The main issue in the use of language depends on the sector that the employee works in. Some regulated professions and economic sectors have high language requirements (e.g., the health, legal, and financial sectors) [55]. This situation has a considerable impact on access to the labour market for beneficiaries of international and temporary protection [55].

Working Conditions

The labour shortage may not result solely from a lack of candidates with the right skills; working conditions (e.g., childcare) may also have an impact. Working conditions can be a serious barrier to integrating migrants into the labour market, as these individuals lack support mechanisms. In some cases, this obliges foreigners to avoid entering the labour market or to leave it. As a result, some skill shortages remain unresolved [47]. This phenomenon is more evident in the case of women beneficiaries of international and temporary protection who cannot access adequate childcare [55].

Illiteracy

An additional challenge is the lack of literacy among certain groups of applicants and beneficiaries of international protection, which complicates their access to the labour market [55], even though there are different institutions that provide language integration courses (Department of Adult Education, SFA) [61] or literacy courses (National Institute of Languages, INLL) [55].

Artificial Intelligence

While Luxembourg has long relied on foreign and cross-border workers to address persistent labour shortages, emerging technological transformations—particularly the rapid development of artificial intelligence—introduce new dynamics that may alter labour market needs. Unlike previous technological transitions, AI is disrupting jobs at a pace not observed since the Industrial Revolution, and employers have already begun integrating it into their operational processes [62]. Several major corporations, such as Meta, have publicly announced substantial layoffs following the deployment of AI technologies. According to a report by the Pew Research Center, one third of American workers believe that AI will reduce their future job opportunities [63].

A broad range of occupations are considered at risk of automation by AI, including manufacturing (process optimisation, quality control, predictive maintenance); defence and military (intelligence gathering and combat operations); retail and commerce (marketing and fraud detection); transportation and logistics (autonomous vehicles); telemarketing (automated calling systems); data entry and analysis (data preparation and visualisation); financial analysis (analysis of financial statements, economic trends, and reporting); portfolio management (portfolio construction and risk management); real estate (market trend identification); taxation; travel; translation; and bookkeeping and accounting [64]. Other professional profiles—such as proofreaders, paralegals, and graphic designers—may also be affected [62]. A clear example of this phenomenon is that major consulting firms in the United States have begun freezing starting salaries for undergraduate and MBA graduates. The increased use of AI has boosted the productivity of the existing workforce, allowing companies to reduce costs. In addition, some firms have started to reduce their headcount, as AI decreases the need for traditional data analyst roles [65].

As many of these activities correspond to service sectors that play a central role in Luxembourg’s tertiary economy, the potential for job displacement is significant. This adds a further layer of complexity to the country’s labour market challenges, where shortages coexist with emerging technological disruptions. The risk is that, while Luxembourg continues to need highly skilled workers to fill persistent gaps, AI may simultaneously reduce demand for certain profiles, thereby reshaping the types of skills required and influencing future migration and workforce planning strategies.

Even though the influence of artificial intelligence on labour is in its infancy [66], the risk that automatisation and robotics replace low skilled and unskilled workers has been recognised in the literature [67]. While automation typically replaces workers performing routine tasks, AI can complement human labour, enhance job scope, and create new opportunities for skilled workers [68]. Both cases require ongoing skill development among workers [66]. Scholarly debate continues as to whether AI is complementary to or a substitution for the workforce. A recent study indicated that there is no solid evidence that AI is removing jobs [69]. Nevertheless, the implementation of AI means that entry into the labour market requires employees to have a higher set of skills [66]. While AI can boost productivity and job creation, it also aggravates social and economic disparities, particularly regarding employment and wages [66]. However, there are studies that indicate that in addition to low skilled workers, highly skilled workers are at risk as well, as AI is changing their sectors (e.g., finance, especially trading and bank customer service [70]) [71].

According to the European Commission, Luxembourg remains a strategic digital hub and a leader in digitalisation in Europe by making targeted investments in key digital technologies [72]. To help companies in this new digital context, especially with AI, the Luxembourg government has implemented several projects like Fit4 AI [73], which supports SMEs in identifying relevant uses of AI through feasibility studies and drafting tailored implementation roadmaps [73]. However, time will be required to properly measure the impact of AI on the labour workforce of companies and the need to recruit skilled and highly skilled migrants.

The impact that artificial intelligence in banking and finance can be significant. Several positions in banking, insurance, and capital markets may be at risk of displacement due to the increasing integration of AI technologies [73] as AI can enhances efficiency and accuracy while reducing costs [74]. AI automates routine tasks—such as data entry, transaction processing, and customer inquiries—reducing errors and improving efficiency. AI tools like chatbots provide round-the-clock support, allowing human staff to focus on more complex work. Additionally, AI enhances fraud detection and risk management by rapidly analysing large datasets, identifying suspicious patterns in real time, and helping financial institutions make proactive, informed decisions [74].

At minimum, the implementation of artificial intelligence requires applicants to have a specific skill set to enter this more sophisticated labour market. This situation not only complicates access to the labour market via the recruitment of third-country nationals in their country of origin but also requires a new strategy of reskilling and upskilling foreign individuals already working in Luxembourg.

4. Challenges to Reskilling and Upskilling the Competences of Third-Country Nationals

4.1. Disparities in Education Systems or Requirements for Specific Professions

The difficulty in recognising qualifications and experience because of disparities in education systems or professional requirements between an applicant’s country of origin and Luxembourg [55] require the third-country national to either take a job for which they are overqualified or undertake reskilling or upskilling. If the third-country national is registered as a job seeker with the National Employment Agency (ADEM), they can benefit from training offers through training partnership with the Chamber of Commerce (House of Training, which provides training in finance, commerce, industry, ICT, real estate, transport, hospitality, and logistics), the Chamber of Trades, and the Chamber of Employees (Luxembourg Lifelong learning center). These training courses help the candidate to better integrate into the labour market [75]. ADEM also offers training for certain sectors with high demand (e.g., data analysis) and courses that can help the job seeker integrate into the labour market (e.g., intensive English, French, German, and Luxembourgish courses for professional use, which are also provided by service providers [76] as part of the Citizen’s Pact for intercultural living together (Biergerpakt) [77]—“Boost your skills”, etc.) [78].

4.2. Lack of a Qualification Registrar and Continuous Learning Programs

Regarding regulated professions, some proposals suggest establishing higher vocational training (formation professionnelle supérieure) in Luxembourg, which would allow for the creation of a specific qualification registrar to align the qualifications of foreign workers with those of workers already working in the country. However, any system offering partial qualifications must also provide a means of obtaining full qualifications through continuous education [47]. To date, neither proposal has been implemented.

4.3. Discrimination in the Labour Market

Another important challenge is discrimination in the labour market. For third-country nationals, discrimination takes the form of (1) language-based exclusion—when language requirements are set disproportionately high—and (2) job interviews, the interviewer disregards the applicant’s professional background and qualifications and focuses on other factors unrelated to the skills required for the position [61]. This discrimination is more obvious for the beneficiaries of international protection [55].

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Luxembourg has relied on foreign labour since the late nineteenth century, initially with the emergence of the steel industry and subsequently through the expansion of the financial and services sectors, which transformed the country into a predominantly tertiary economy. However, as Luxembourg is a landlocked state, since 1995 this reliance has increasingly centred on cross-border workers from neighbouring countries within the Greater Region, thereby reducing the relevance of third-country nationals in addressing labour market shortages. This economic model distinguishes Luxembourg from other EU Member States.

In recent years, however, the perspective on recruiting third-country nationals has begun to shift. The supply of cross-border workers has shown signs of stagnation—due in part to long commuting times and rising travel costs—and certain skill profiles sought by Luxembourgish employers are insufficiently available within the Greater Region. As a result, the strategic importance of attracting third-country nationals to meet evolving labour market needs has become more apparent.

Most developed countries are experiencing a natality deficit that directly affects the labour market, especially with an ageing population that is reaching retirement age. Even though unemployment is increasing in most economies, like in Luxembourg, there are many job openings that cannot be filled [31,79]. Migration can ameliorate these labour shortages, a solution recognised by most countries. Nevertheless, migration is a very political issue, as some populist parties on the extreme right try to project a negative image of the subject [80].

Normally, large corporations and companies can use foreign labour to satisfy their labour needs. However, SMEs do not have the time or resources to access this workforce, as in most EU countries, the process of obtaining a residence permit is burdensome, long, and uncertain, as the application does not guarantee a positive decision by the administration. This means that SMEs are discouraged from hiring third-country nationals, as they need workers in the short term and cannot wait several months to hire staff.

Luxembourg is an example of this problem, as employers must first declare the open position to ADEM and then wait three weeks to see if there is a viable candidate in the local or European market to fulfil the position. After this, if there is no viable candidate, the employer will receive a certificate, and then a third-country national can apply for a salaried worker authorisation of stay. However, Immigration Law states that the administration has up to four months to decide. This means that the normal procedure will take up to five months. Even though the law was modified to exempt employers in sectors with labour shortages that are included in a predetermined list, which reduced the length of time from three weeks to five days, the deadline for the administration to make a decision remains unchanged.

Another significant barrier to recruiting third-country nationals in a tertiary economy such as Luxembourg concerns the recognition of qualifications and professional experience. This process is often burdensome, time-consuming, and marked by uncertain outcomes, particularly for regulated professions. In cases where the administrative decision is negative, available legal remedies tend to be lengthy, further delaying labour market access. Divergences between the education systems of third countries and that of Luxembourg compound these difficulties, as equivalence assessments become more complex and less predictable. Although similar challenges exist with respect to other EU Member States, the issue is particularly pronounced in Luxembourg, where even the recognition of a secondary education diploma requires applicants to demonstrate the completion of thirteen years of schooling—a criterion that is not standard in many other Member States. These structural factors directly contribute to skill mismatches in the Luxembourgish labour market.

Legally residing third-country nationals find themselves in a similar situation; because of the burdensome process of having their qualifications and professional experience recognised, they find themselves in positions for which they are overqualified. Some factors making it difficult to recognise qualifications are disparities between the educational systems and curricula of the third countries and Luxembourg (especially for regulated professions). As a result, some positions cannot be filled by third-country nationals with the appropriate qualifications as they are unrecognised, a situation aggravated by the complex language context of Luxembourg.

A possible solution is to simplify the recognition of qualifications and establish an effective system for validating professional experience, even though the recognition will be partial. It would be beneficial to establish an upskilling system to bring qualifications into alignment with Luxembourg standards and offer intensive language courses to better incorporate third-party nationals into the labour market, filling open positions.

These problems are more obvious for the beneficiaries of temporary and international protection. In the case of Ukrainian beneficiaries of temporary protection, the recognition of qualifications and linguistic issues remain significant barriers [81]. In addition to the issues mentioned above, illiteracy also affects some beneficiaries, who do not speak any of the official languages of Luxembourg and cannot read or write their own language. This makes it more difficult to integrate them into the labour market. Even though Luxembourg has some literacy programs available for these individuals, the time required to incorporate them into the labour market means that they cannot join the labour force in the short term.

There is also subtle discrimination from employers regarding third-country nationals (e.g., asking questions outside the scope for the position, exaggerated language requirements), which also affects access to the labour market.

Finally, artificial intelligence can become an additional obstacle for foreigners trying to access the labour market, as AI may make certain positions or tasks redundant. Although there is currently no evidence that this is happening, AI has begun to influence the recruitment of workers in economic sectors (only 60% of employers are planning to increase their headcount) [82], which will have a direct impact on the foreign labour workforce. Additionally, the introduction of AI into the economic sector will require reskilling so that migrants can use these new digital technologies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, A.S. and B.N.; investigation, A.S.; resources, A.S. and B.N.; writing—original draft preparation, A.S.; writing—review and editing, A.S. and B.N.; supervision, B.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created in this study.

Acknowledgments

The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ADEM | Luxembourg National Employment Agency |

| AI | Artificial intelligence |

| EMN | European Migration Network |

| EU | European Union |

| GDP | Gross Domestic Product |

| ICT | Information and communication technology |

| INLL | Luxembourgish National Institute of Languages |

| SFA | Department of Adult Education in Luxembourg |

| SME | Small- and medium-size enterprise |

| TCN | Third-country national |

References

- Hooper, K.; de Lange, T.; Slootjes, J. How Can Labour Migration Policies Help Tackle Europe’s Looming Skills Crisis? Migration Policy Institute Europe: Brussels, Belgium, 2025; p. 1. Available online: https://www.migrationpolicy.org/sites/default/files/publications/mpie-gs4s-europe-skills-2025_final.pdf (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- EUROSTAT. Total Fertility Rate. In 2023, There Were 3,67 Babies Born in the EU Which Represents a Decrease of 5.4% in Comparison with 2022 Being the Largest Drop since 1961. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/tps00199/default/table?lang=en&category=t_demo.t_demo_fer (accessed on 27 July 2025).

- Directorate-General for Employment. Social Affairs and Inclusion, ‘Quarterly Review of Employment and Social Developments in Europe (ESDE)—January 2025’, European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2025; p. 18. Available online: https://employment-social-affairs.ec.europa.eu/quarterly-review-employment-and-social-developments-europe-esde-january-2025_en (accessed on 27 July 2025).

- Weber, T.; Adăscăliței, D. Employment and Labour Markets: Company Practices to Tackle Labour Shortages; Eurofund: Madrid, Spain, 2024; Available online: https://www.eurofound.europa.eu/en/publications/2024/company-practices-tackle-labour-shortages (accessed on 27 July 2025).

- The Government of the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg. Luxembourg’s Territory, Luxembourg, 2025. Available online: https://luxembourg.public.lu/en/society-and-culture/territoire-et-climat/territoire.html (accessed on 27 November 2025).

- STATEC, Total Population, Luxembourgers and Foreigners of Usual Residence in Luxembourg by Sex, Luxembourg, 2025. Population and density on 31 December 2024. Available online: https://lustat.statec.lu/vis?fs[0]=Topics%2C1%7CPopulation%20and%20employment%23B%23%7CPopulation%20structure%23B1%23&pg=0&fc=Topics&lc=en&snb=9&df[ds]=ds-release&df[id]=DF_B1100&df[ag]=LU1&df[vs]=1.0&dq=.A&lom=LASTNOBSERVATIONS&lo=5&pd=2015%2C2024&to[TIME_PERIOD]=false (accessed on 27 November 2025).

- International Monetary Fund World Economic Outlook GDPper Capita Current Prices: U.S. Dollars Per Capita. Washington D.C. October 2025. Available online: https://www.imf.org/external/datamapper/NGDPDPC@WEO/OEMDC/ADVEC/WEOWORLD/LUX (accessed on 27 November 2025).

- Luxtoday. Why is Luxembourg so Rich: Steel, Taxes, Billionaires, Luxembourg. 30 October 2025. Available online: https://luxtoday.lu/en/knowledge/why-is-luxembourg-so-rich (accessed on 27 November 2025).

- Vivre Ensemble au Grand-Duché de Luxembourg. Why Luxembourg is One of the Wealthiest Countries in the World, Luxembourg, 2025. Available online: https://vivre-ensemble.lu/why-luxembourg-is-one-of-the-wealthiest-countries-in-the-world/ (accessed on 27 November 2025).

- Pauly Michel, Le Phénomène Migratoire, une Constante de L’histoire Luxembourgeoise, ASTI 30+, Luxembourg, 2010, p. 63. EMN Luxembourg, Satisfying Labour Demand through Migration, Luxembourg, 2011. pp. 29–32. Available online: https://orbilu.uni.lu/bitstream/10993/2267/1/EMN%20NCP%20LU_Labor_Study_Demand_2011_EN_.pdf (accessed on 27 November 2025).

- The foreign population is composed of 101.070 EU Citizens and 29.561 Third-Country Nationals, while the Cross-Border Workers Coming from France Amount to 127.101; from Germany 51.690 and from Belgium 51.296. Statec, Emploi Salarié Intérieur Par Lieu de Résidence, Luxembourg, Q2 2025. Available online: https://lustat.statec.lu/vis?fs[0]=Th%C3%A8mes%2C1%7CPopulation%20et%20emploi%23B%23%7CMarch%C3%A9%20du%20travail%23B5%23&pg=0&fc=Th%C3%A8mes&bp=true&snb=46&lc=fr&df[ds]=ds-release&df[id]=DSD_EMPLOI_SAL%40DF_B3002&df[ag]=LU1&df[vs]=1.0&dq=..Q....&lom=LASTNOBSERVATIONS&lo=5&pd=2015-Q1%2C2025-Q2&to[TIME_PERIOD]=false (accessed on 27 November 2025).

- Statec, Evolution naturelle de la population, Luxembourg, 2025. Available online: https://lustat.statec.lu/vis?pg=0&bp=true&snb=42&lc=fr&fs[0]=Th%C3%A8mes%2C1%7CPopulation%20et%20emploi%23B%23%7CMouvement%20de%20la%20population%23B3%23&fc=Th%C3%A8mes&df[ds]=ds-release&df[id]=DF_B2101&df[ag]=LU1&df[vs]=1.0&dq=A..&pd=2015%2C2024&to[TIME_PERIOD]=false (accessed on 27 November 2025).

- The High-Impact Sectors Are: Public Administration, Finance, Health, and Culture. The Government of Luxembourg, Luxembourg’s AI Strategy: Accelerating Digital Sovereignty 2030, May 2025. pp. 38–45. Available online: https://gouvernement.lu/dam-assets/images-documents/actualites/2025/05/16-strategies-ai-donnees-quantum/2024115332-ministere-etat-strategy-ai-en-bat-acc-ua.pdf (accessed on 27 November 2025).

- Citi GPS: Global Perspectives & Solutions, AI in Finance, Bot, Bank & Beyond, June 2024. pp. 22–23. Available online: https://www.citifirst.com.hk/home/upload/citi_research/rsch_pdf_30255539.pdf (accessed on 27 November 2025).

- Triandafyllidou, A.; Shirazi, H.; Engbersen, G. Migration Skill Corridors; European Union: Brussels, Belgium, 2024; Available online: https://link4skills.eu/index.php/2025/01/22/migration-skill-corridors/ (accessed on 18 July 2025).

- Dotsey, S. Foreign Healthcare Workers and Covid-19 in Europe: The Paradox of Unemployed Skilled Labour. Soc. Sci. 2023, 12, 211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunello, G.; Wruuck, P. Skill Shortages and Skill Mismatch: A Review of the Literature. Econ. Surv. 2021, 35, 1145–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGuiness, S.; Pouliakas, K.; Redmond, R. Skills mismatch: Concepts, measurements and policy approaches. J. Econ. Surv. 2018, 32, 985–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauder, H. “Brain abuse”, or the devaluation of immigrant labour in Canada. Antipode 2003, 35, 699–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGovern, P.; Thielemann, E.; Hammoud-Gallego, O. The return of the state: How European governments reglate labour market competition from migrant workers. Comp. Migr. Stud. 2025, 13, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kofman, E.; Raghuram, P. Gender and Global Labour Migrations: Incorporating Skilled Workers. Antipode 2006, 38, 282–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blit, J.; Skuterud, M.; Zhang, J. Can skilled immigration raise innovation? Evidence from Canadian Cities. J. Econ. Geogr. 2020, 20, 879–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calderón-Larrañaga, S.; González-De-La-Fuente, Á.; Espinosa-González, A.B.; Casado-Vicente, V.; Brito-Fernandes, Ó.; Klazinga, N. What can we learn from general practitioners who left Spain? A mixed methods international study. Hum. Resour. Health 2024, 22, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farrer, J. From cooks to chefs: Skilled migrants in a globalising culinary field. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 2021, 47, 2359–2375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu-Farrer; Karen, S. Who are the fittest? the question of skills in national employment systems in an age of global labour mobility. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 2021, 47, 2395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oishi, N. Skilled or unskilled? The reconfiguration of migration policies in Japan. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 2021, 47, 2252–2269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broschinski, S.; Heidenreich, M. Overeducation among EU and third-country immigrants in Europe: The role of institutions, policies, and culture. Eur. Soc. 2025, 27, 784–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCormack George, D. Recognition of professional qualifications of third country nationals in the European Union: A comment. Eur. Labour Law J. 2025, 16, 146–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Government of the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg, Portrait of the Luxembourg Economy, Luxembourg, 2025. Available online: https://luxembourg.public.lu/en/invest/competitiveness/portrait-luxembourg-economy.html#section-content (accessed on 27 November 2025).

- Government of Luxembourg. Accord de Coalition 2023–2028: “Lëtzebuerg fir d’Zukunft Stäerken”. 20 November 2023. Available online: https://gouvernement.lu/dam-assets/documents/dossier/formation-gouvernement-2023/accord-coalition.pdf (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- ADEM Le Taux de Chômage Ajusté Saisonnièrement Progresse à 6%, Malgré Une Baisse Des Inscriptions. Communique de Presse. 20 May 2025. Available online: https://adem.public.lu/dam-assets/fr/publications/adem/2025/cp-cc-2025-04/cp-cc-2025-04-fr.pdf (accessed on 27 November 2025).

- STATEC, Domestic payroll employment by place of residence. Available online: https://lustat.statec.lu/vis?lc=en&pg=0&fs[0]=Topics%2C1%7CPopulation%20and%20employment%23B%23%7CLabour%20market%23B5%23&fc=Topics&bp=true&snb=46&df[ds]=ds-release&df[id]=DSD_EMPLOI_SAL%40DF_B3002&df[ag]=LU1&df[vs]=1.0&dq=..Q....&lom=LASTNOBSERVATIONS&lo=5&pd=2015-Q1%2C2025-Q2&to[TIME_PERIOD]=false (accessed on 27 November 2025).

- European Commission. Temporary Reintroduction of Border Control. Available online: https://home-affairs.ec.europa.eu/policies/schengen/schengen-area/temporary-reintroduction-border-control_en#:~:text=The%20Schengen%20Borders%20Code%20%28SBC%29%20provides%20Member%20States,serious%20threat%20to%20public%20policy%20or%20internal%20security (accessed on 27 July 2025).

- Avenant Fiscal France-Luxembourg: Ce Qui Change Pour les Travailleurs Frontaliers. An Example Is the New Fiscal Conven-tion Between France and Luxembourg. 14 February 2025. Available online: https://ordreavocats-cussetvichy.fr/avenant-fiscal-france-Luxembourg-ce-qui-change-pour-les-travailleurs-frontaliers/ (accessed on 27 July 2025).

- European Commission. Pact on Migration and Asylum: Embedding Migration in International Partnerships. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/api/files/attachment/878139/Embedding%20migration%20in%20international%20partnerships.pdf (accessed on 27 July 2025).

- Directive (EU) 2021/1883 of the European Parliament of the Council of 20 October 2021 on the Conditions of Entry Residence of Third-Country Nationals for the Purpose of Highly Qualified Employment Repealing Council Directive, 2.0.0.9./.5.0./.E.C. This Directive Was Transposed by the Law of 4 June 2024. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/HTML/?uri=CELEX:32021L1883 (accessed on 27 July 2025).

- Ministerial Regulation of 6 March 2025 Establishing the Average Gross Annual Salary Under the Amended Grand-Ducal Regulation of 26 September 2008 Determining the Minimum Remuneration Level for a Highly Qualified Worker in Implementation of the Law of 29 August 2008 on the Free Movement of Persons and Immigration. Available online: https://legilux.public.lu/eli/etat/leg/rmin/2025/03/06/a90/jo (accessed on 27 July 2025).

- Guichet.lu. Salaried Work for Third Country Highly Qualified Workers (EU Blue Card). Available online: https://guichet.public.lu/en/citoyens/immigration/plus-3-mois/ressortissant-tiers/hautement-qualifie/salarie-hautement-qualifie.html (accessed on 27 July 2025).

- Article 42 of the Amended Law of 29 August 2008 on Free Movement of Persons and Immigration. Available online: https://legilux.public.lu/eli/etat/leg/loi/2008/08/29/n1/consolide/20241224#art_42 (accessed on 27 July 2025).

- Article, L. 622-4 of the Labour Code. Code de Travail, Version Consolidée au 28 June 2025. Available online: https://legilux.public.lu/eli/etat/leg/code/travail/20250628 (accessed on 27 November 2025).

- Guichet.lu. Conditions of Residence for Third-Country Salaried Workers in Luxembourg. Available online: https://guichet.public.lu/en/citoyens/immigration/plus-3-mois/ressortissant-tiers/salarie/salarie-pays-tiers.html (accessed on 27 July 2025).

- Parliamentary Document 8227/00 of 30 May 2023, Exposition of Motives, Luxembourgish Parliament, Luxembourg, 2023, p. 11. Available online: https://wdocs-pub.chd.lu/docs/Dossiers_parlementaires/8227/20250515_Dep%C3%B4t.pdf (accessed on 27 November 2025).

- Article 16 of the Law of 7 August 2023 amending: 1° the Labour Code; 2° the amended Law of 29 August 2008 on the Free Movement of Persons and Immigration; 3° the Amended Law of 18 December 2015 on the Reception of Applicants for International Protection and Temporary Protection. Available online: https://legilux.public.lu/eli/etat/leg/loi/2023/08/07/a556/jo (accessed on 27 November 2025).

- Article, L. 622-4 (5) of the Labour Code as Modified by Article 16 of the Law of 7 August 2023. Available online: https://legilux.public.lu/eli/etat/leg/code/travail/20240227#art_l_622-4 (accessed on 27 July 2025).

- Le Gouvernement Luxembourgeois, Publication D’une Nouvelle Liste des Métiers Très en Pénurie, Communiqué de Presse, Luxembourg, 31 Mars 2025. Available online: https://gouvernement.lu/fr/actualites/toutes_actualites/communiques/2025/03-mars/31-publication-liste-metiers.html (accessed on 27 November 2025).

- ADEM New List of Occupations in High Shortage. 31 March 2025. Available online: https://adem.public.lu/en/actualites/adem/2025/03/metiers-penurie.html (accessed on 27 July 2025).

- EMN Luxembourg. Labour Migration in Times of Labour Shortages in Luxembourg (January 2021–June 2024); EMN: Luxembourg, November 2024. [Google Scholar]

- American Chamber of Commerce (AMCHAM). Interview: Laurent Peusch; ADEM: Luxembourg. 18 September 2024. Available online: https://www.amcham.lu/newsletter/3-questions-about-the-spousal-work-permit/ (accessed on 27 July 2025).

- Article 43 (1) of the Amended Law of 29 August 2008 on Free Movement of Persons and Immigration. Available online: https://legilux.public.lu/eli/etat/leg/loi/2008/08/29/n1/consolide/20241224#art_43 (accessed on 27 July 2025).

- Hansen, Y. Interview with Claude Meisch: Luxembourg Has “Some Catching up to Do” on Affordable Housing. Luxembourg Times. 19 September 2024. Available online: https://gouvernement.lu/de/gouvernement/claude-meisch/actualites.gouvernement2024+en+actualites+toutes_actualites+interviews+2024+09-septembre+19-meisch-Luxembourg-times.html (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- Expat.com. Le Coût de la Vie au Luxembourg, Luxembourg, 2025. Available online: https://www.expat.com/fr/guide/europe/luxembourg/36220-le-cout-de-la-vie-au-luxembourg--budget-et-conseils-pour-s-y-installer.html (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- Law of 2 September 2011 Regulating the Access the Professions of Craftsman, Merchant, Industrialist, and Certain Liberal Professions. Available online: https://legilux.public.lu/eli/etat/leg/loi/2011/09/02/n1/jo (accessed on 27 November 2025).

- Council of Europe. Convention on the Recognition of Qualification Concerning Higher Education in the European Region (ETS No. 165); Council of Europe: Strasbourg, France, 2025. Available online: https://www.coe.int/en/web/conventions/-/council-of-europe-convention-on-the-recognition-of-qualifications-concerning-higher-education-in-the-european-region-ets-no-165-translations (accessed on 27 November 2025).

- Guichet.lu. Application for Recognition of Equivalence of Professional Qualifications. Available online: https://guichet.public.lu/en/citoyens/famille-education/enseignement-secondaire/jeune-recemment-arrive-pays/reconnaissance-etudes/reconnaissance-equivalence-diplome.html (accessed on 27 July 2025).

- European Migration Network. Luxembourg, Fostering Sustainable Labour Market Integration of Third Country Nationals: Skills Matching Policies and Instrument: Luxembourg National Report; European Migration Network: Brussels, Belgium, 2025; pp. 6–15. [Google Scholar]

- ADEM Zoom sur les Demandeurs D’emploi Avec Qualification Supérieure. 12 February 2024. Available online: https://adem.public.lu/dam-assets/fr/publications/adem/zoom-emploi/zoom-emploi-2023-01.pdf (accessed on 27 July 2025).

- Dalmonte, A.; Frattini, T.; Giorgini, S. The Overeducation of Immigrants in Europe. 18 October 2024. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4991626# (accessed on 27 July 2025).

- Infomigrants. Unrealized Potential: The Challenge of ‘Brain Waste’ Among Europe’s Skilled Migrants. Available online: https://www.infomigrants.net/en/post/59149/unrealized-potential-the-challenge-of-brain-waste-among-europes-skilled-migrants (accessed on 27 November 2025).

- Law of 24 February 1984 on Language Regime. Consolidated Version of 1st September 2020. Available online: https://legilux.public.lu/eli/etat/leg/loi/1984/02/24/n1/consolide/20200901 (accessed on 27 November 2025).

- Luxembourg Government. What Languages do People Speak in Luxembourg. English is the Lingua Franca Use Mainly by the European Institutions and the Banking, Business and Industrial Sectors. Available online: https://luxembourg.public.lu/en/society-and-culture/languages/languages-spoken-luxembourg.html (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- Ministry of National Education. Children and Youth, Linguistic Integration of Newly Arrived Adults. Available online: https://men.public.lu/en/systeme-educatif/formation-adultes/integration-nationalite/integration.html#:~:text=It%20is%20aimed%20at%20applicants%20and%20beneficiaries%20of,level%20courses%20for%20French%20as%20an%20integration%20language (accessed on 27 July 2025).

- Wells, Rachel, 11 Jobs AI Could Replace in 2025—And 15+ Jobs That are Safe. Forbes. 10 March 2025. Available online: https://www.forbes.com/sites/rachelwells/2025/03/10/11-jobs-ai-could-replace-in-2025-and-15-jobs-that-are-safe/ (accessed on 27 November 2025).

- Luona, L.; Kim, P. U.S. Workers Are More Worried Than Hopeful About Future AI Use in the Workplace, Pew Research Center. 25 February 2025. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/social-trends/2025/02/25/u-s-workers-are-more-worried-than-hopeful-about-future-ai-use-in-the-workplace/ (accessed on 27 November 2025).

- Automated Roles Are “Are Tasks that Machines or Software Programs Can Perform Without Human Intervention. They’re Typically Routine or Repetitive Actions that Require a High Degree of Accuracy. They May Include Simple Tasks, Such as Making Phone Calls, or Complex Processes, Such as Running Data Analysis or Processing Transactions. In Industrial Environments, Automated Duties are often Those that Humans Perceive as Undesirable.” Indeed, 3 Automated Jobs and Details of How AI Can Replace Them. Available online: https://uk.indeed.com/career-advice/finding-a-job/automated-jobs (accessed on 27 November 2025).

- Stephen, F.; Ellesheva, K. Top Consultancies Freeze Starting Salaries as AI Threatens ‘Pyramid’ Model, Financial Times. 1 December 2025. Available online: https://www.ft.com/content/2b15601b-8d02-4abe-a789-7862874042be (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Wang, K.-H.; Lu, W.-C. AI-induced job impact: Complementary or substitution? Empirical insights and sustainable technology considerations. Sustain. Technol. Entrep. 2025, 4, 100085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badiuzzaman, M.; Rafiquzzaman, M. Automation and robotics: A review of potential threat on unskilled and lower skilled labour unemployment in highly populated countries. Int. Bus. Manag. 2020, 14, 16–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Autor, D. Why Are There Still So Many Jobs? The History and Future of Workplace Automation. J. Econ. Perspect. 2015, 29, 3–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gimbel, M.; Kinder, M.; Kendall, J.; Lee, M. Evaluating the Impact of AI on the Labour Market: Current State of Affairs; The budget Lab; Yale University: New Haven, CT, USA, 2025. Available online: https://budgetlab.yale.edu/research/evaluating-impact-ai-labor-market-current-state-affairs (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Muhammad, T. How Artificial Intelligence Is Disrupting the Finance Industry, Sciences News Today. 25 April 2025. Available online: https://www.sciencenewstoday.org/how-artificial-intelligence-is-disrupting-the-finance-industry (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Guliyev, H. Artificial intelligence and unemployment in high-tech developed countries: New insights from dynamic panel data model. Res. Glob. 2023, 7, 100140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Luxembourg 2025 Digital Decade Country Report; Short County Report; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2025; p. 1. Available online: https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/node/13729/printable/pdf (accessed on 27 November 2025).

- Luxinnovation. Fit4 AI, Use Artificial Intelligence to Grow Your Business. Available online: https://luxinnovation.lu/digitalise-activities/digital-cyber-maturity/fit-4-ai (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- Synjoy, G. Transforming Finance with AI: Key Insights from Citi’s GPS Focus Report. 1 August 2024. Available online: https://www.apexon.com/blog/transforming-finance-with-ai-key-insights-from-citis-gps-focus-report/#:~:text=Citi%E2%80%99s%20latest%20GPS%20Focus%20Report%2C%20%E2%80%9CAI%20in%20Finance%3A,are%20the%20key%20takeaways%20from%20this%20insightful%20research (accessed on 27 November 2025).

- ADEM Training Partnerships. Available online: https://adem.public.lu/en/demandeurs-demploi/se-former/Formations-en-partenariat.html (accessed on 27 July 2025).

- Guichet. lu, Citizen’s Pact for Intercultural Living Together—‘Biergerpakt’. Available online: https://guichet.public.lu/de/citoyens/citoyennete/vivre-ensemble/pacte-citoyen.html (accessed on 27 November 2025).

- Article 5 (3) 3 of the Law of 23 August 2023 on Intercultural Living Together and Amending the Amended Law of 8 March 2017 on Luxembourg Nationality, Published in Memorial A545 of 25 August 2023. Available online: https://legilux.public.lu/eli/etat/leg/loi/2023/08/23/a545/jo (accessed on 27 July 2025).

- Luxembourg Government. Évolution du Chômage en Septembre 2025: Rentrée 2025: Davantage de Demandeurs D’emploi et Davantage de Déclarations D’offres D’emploi, Press Release. 20 October 2025. Available online: https://gouvernement.lu/fr/actualites/toutes_actualites/communiques/2025/10-octobre/20-adem-chomage1.html (accessed on 21 October 2025).

- European Commission. The Future of European Competitiveness Part B|In-Depth Analysis and Recommendations; European Commission: Luxembourg, 2024; p. 258. Available online: https://dorie.ec.europa.eu/en (accessed on 27 November 2025).

- Ammar, M.S.B. «Submersion Migratoire»: Quand La Politique Ébranle Les Valeurs Républicaines, Nouvel Observatoire. 3 February 2025. Available online: https://www.nouvelobs.com/politique/20250203.OBS99861/submersion-migratoire-quand-la-politique-ebranle-les-valeurs-republicaines.html (accessed on 21 October 2025).

- Adolfo, S.; Birte, N. Migration International au Luxembourg, Système D’observation Permanente des Migrations, OCDE. October 2024. Available online: https://orbilu.uni.lu/handle/10993/63644 (accessed on 21 October 2025).

- Paperjam, David Capocci (KPMG): “Despite AI, CEOs Plan to Recruit”: 11th Edition of KPMG CEO Outlook. 29 October 2025. Available online: https://en.paperjam.lu/article/david-capocci-kpmg-despite-ai-ceos-plan-to-recruit (accessed on 21 October 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).