Abstract

Early childhood education (ECE) fundamentally shapes children’s developmental trajectories, significantly influencing lifelong cognitive, socio-emotional, and physical outcomes. Despite considerable policy efforts aimed at enhancing educational equity across the United States, marked disparities persist between rural and urban contexts, reflecting deep-rooted structural inequalities rather than mere geographic differences. This integrative review systematically examines disparities in ECE access, quality, workforce conditions, infrastructural resources, and developmental outcomes, specifically comparing rural and urban settings. Utilizing Ecological Systems Theory, Capital Theory, and an Intersectional framework, the study identifies critical systemic determinants reinforcing rural educational inequities, exacerbated further by the recent COVID-19 pandemic. The findings reveal chronic underfunding, fragmented governance, workforce instability, infrastructural inadequacies, and intersectional disadvantages disproportionately impacting rural communities. Based on these insights, this study proposes targeted, evidence-based policy recommendations, emphasizing the necessity for increased federal funding, mandated rural representation in policymaking, workforce stabilization incentives, infrastructural enhancements, and robust community partnerships. This research calls for immediate, systemic policy responses to ensure equitable early educational foundations for all children across diverse geographic contexts by bridging a significant research gap through a comprehensive rural–urban comparative lens.

1. Introduction

ECE plays a foundational role in shaping children’s developmental trajectories, influencing cognitive abilities, social-emotional growth, physical health, and overall well-being [1,2]. Robust empirical evidence underscores the extensive individual and societal benefits derived from access to high-quality early education, including improved educational outcomes, reduced long-term disparities, and enhanced economic and social productivity [3,4,5]. Recognizing these critical advantages, policymakers across the United States have enacted significant investments and targeted programs aimed at expanding and improving ECE. Prominent initiatives include federal programs such as Head Start and state-funded Pre-Kindergarten schemes designed explicitly to narrow gaps and improve educational equity nationwide [2].

Despite such concerted policy efforts, considerable disparities persist, particularly between rural and urban communities across the United States, posing serious challenges to achieving equity in education and broader social outcomes [3]. Research consistently highlights multiple dimensions of these disparities, including differential access to educational resources, varying standards of childcare quality, divergent infrastructural capacities, and substantial gaps in the qualifications and retention rates of early childhood educators [3,4,6]. Such inequalities not only perpetuate academic achievement gaps but also influence long-term health and developmental outcomes, compounding the adverse effects experienced by rural populations [7,8,9].

Several studies have systematically documented rural communities’ unique challenges, particularly emphasizing geographic isolation, socioeconomic vulnerabilities, demographic decline, and infrastructural deficits as key factors exacerbating educational disparities [8]. Anderson and Mikesell [3] highlighted distinct rural disadvantages related to childcare availability, noting fewer qualified educators, limited educational resources, and infrastructure deficiencies, such as inadequate facilities and reduced technological capacities. Similarly, Maher et al. provided compelling evidence of inferior childcare quality indicators in rural contexts, including lower teacher–child ratios, diminished curricular offerings, and poorer teacher qualifications compared to urban environments [4].

These persistent rural disadvantages have significant repercussions for children’s developmental trajectories, particularly impacting readiness for formal schooling and long-term academic success [1]. Morrissey et al. [2] explicitly identified reduced school readiness and heightened educational remediation needs among rural children, directly attributable to limited access to quality early educational experiences. The implications of these findings extend beyond academic domains, intersecting broadly with physical and socio-emotional health outcomes. For instance, Johnson and Johnson [7] identified rural–urban disparities in childhood obesity prevalence, partially linked to poorer adherence to recommended physical activity guidelines and limited capacity of rural childcare providers to implement best practice standards for physical education [9].

Additionally, recent global challenges, notably the COVID-19 pandemic, have illuminated and intensified pre-existing rural–urban educational divides, especially through disparities in digital infrastructure and internet connectivity [10,11]. The rapid shift to remote education during the pandemic disproportionately impacted rural communities, where limited access to stable, high-speed internet significantly compromised educational continuity and exacerbated existing inequalities [12]. Zhao et al. [10] highlighted capital theory’s relevance to understanding digital outcome disparities, emphasizing how infrastructural inequalities in rural settings amplified educational inequities during periods of remote learning. Further, Eruchalu et al. [11] argued that digital disparities are fundamentally interconnected with socioeconomic vulnerabilities, suggesting compounded marginalization for rural populations during crises.

The complexity of these multifaceted disparities necessitates a comprehensive approach to understanding and addressing rural–urban gaps. Although previous research has significantly contributed to our understanding of rural–urban educational inequalities in primary and secondary education contexts, there remains a critical research gap specifically focused on ECE within the United States. Recent investigations into rural ECE disparities have typically isolated singular dimensions, such as childcare type, educator workforce well-being, or individual developmental outcomes, rather than examining these factors through integrative, multidimensional frameworks [4,6].

Moreover, comparative analyses of rural–urban educational gaps in international contexts primarily emphasize low- and middle-income countries, limiting the direct applicability of these findings to the complex socioeconomic landscape of the United States [1]. This limitation underscores the urgent need for research explicitly tailored to the American educational context, systematically linking rural–urban disparities in ECE access, quality, infrastructure, digital connectivity, educator characteristics, and developmental outcomes.

Addressing this critical knowledge gap, the present study aims to provide a comprehensive, detailed examination of the rural–urban divide within ECE across the United States. Specifically, this research seeks to achieve three interconnected objectives:

- To systematically analyze disparities in ECE access, resource allocation, and quality standards between rural and urban communities.

- Evaluate the direct implications of these disparities on children’s cognitive, socio-emotional, and physical development.

- Identify underlying systemic, infrastructural, and socioeconomic determinants contributing significantly to these inequalities.

By synthesizing these dimensions into a unified analytical framework, the study intends to provide a nuanced, policy-relevant contribution aimed explicitly at mitigating educational disparities from the earliest stages of child development and informing strategic investments and policy interventions that foster equity across rural and urban educational landscapes.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Historical Evolution and Structural Foundations of ECE in the United States

The development of ECE in the United States is deeply embedded in broader societal shifts related to industrialization, child welfare reform, and the democratization of education. As the 19th century progressed, concerns around child labor, immigrant assimilation, and female workforce participation drove the establishment of early care institutions aimed at nurturing young children outside the home. Kindergarten, introduced in the mid-to-late 1800s through Froebelian influence, laid the groundwork for structured early learning, emphasizing play-based pedagogies and moral development [13,14]. As educational reform movements gained traction in the 20th century, the field began adopting varied approaches—Montessori, Progressive, and Developmentally Appropriate Practices—each contributing distinctive philosophies and curricular frameworks that continue to influence ECE today [15,16].

A significant shift occurred during the mid-20th century with the expansion of federally funded programs. The landmark 1965 launch of Head Start under the Economic Opportunity Act institutionalized the idea that early intervention could combat poverty through comprehensive educational, health, and nutritional support. This initiative not only recognized the role of early education in long-term academic success but also highlighted the government’s responsibility in addressing systemic inequality from a young age [14,17]. Over time, additional state-level Pre-K initiatives were introduced, particularly in urban centers, reflecting the growing political will to institutionalize early learning within the public education system.

Despite these developments, the U.S. ECE system remains largely decentralized and market-driven, contrasting with more centralized systems in other industrialized nations. Witte and Trowbridge [18] highlighted this fragmentation, noting significant disparities in how ECE is funded, regulated, and delivered across states. The reliance on a mixed-delivery model involving public programs, private centers, and home-based care introduces inconsistencies in access and quality, particularly disadvantaging families in rural and under-resourced areas.

Moreover, the structure of professional development in ECE has evolved inconsistently, reflecting historical underinvestment in the early childhood workforce. While efforts have been made to formalize credentialing and improve training pipelines, disparities in teacher qualifications, compensation, and support persist [19]. Mickelson et al. [20] discussed how blended training programs aimed at integrating general and special education have shaped professional identity in early childhood teaching, yet their reach remains uneven across geographies.

A further layer of complexity is introduced by local governance models. Wilkinson et al. [21,22] documented how community-led partnerships and funding coalitions have emerged to fill service gaps in early childhood provision. These efforts have been particularly critical in rural and marginalized urban communities where traditional funding streams are insufficient. However, the scalability and long-term sustainability of such community-based models are often challenged by policy fragmentation and limited federal–state coordination.

The following Table 1 outlines key historical developments, policy shifts, and structural characteristics of ECE in the U.S., providing a concise reference for understanding how the system has evolved over time:

Table 1.

Key Historical and Structural Developments in ECE in the United States.

This historical overview reveals that while the United States has made significant strides in recognizing the importance of ECE, its evolution has been uneven, shaped by ideological, political, and economic factors. The fragmented nature of governance and funding continues to influence contemporary disparities, particularly between rural and urban regions—a divide that remains central to current policy discourse and empirical research.

2.2. Rural–Urban Disparities in Access, Quality, and Outcomes

A consistent theme in contemporary literature is the persistent and multifaceted divide in ECE outcomes between rural and urban settings. Morrissey et al. [2] provided an in-depth analysis of access disparities, revealing that rural families face significant geographic and logistical barriers to securing high-quality early care. These barriers are compounded by the limited availability of licensed centers, transportation constraints, and a scarcity of qualified professionals willing to serve in rural regions.

Access disparities are further intensified by socioeconomic and demographic variables. Research by Hall [23] and Beatty et al. [24] demonstrates how funding formulas and service delivery mechanisms disproportionately disadvantage rural localities. This is mirrored in health and public service domains, where urban centers receive a disproportionate share of development grants and health resources, thereby deepening structural inequalities [25,26].

The quality of care also reflects stark discrepancies. Maher et al. [4] reported significantly lower indicators of care quality in rural environments, including lower teacher qualifications, diminished instructional resources, and higher child–teacher ratios. Puma et al. [6] extended these findings to educator well-being, noting that rural early childhood professionals often contend with greater isolation, lower compensation, and limited access to professional development opportunities.

In terms of child outcomes, rural–urban gaps are evident across multiple domains of development. Johnson and Johnson [7] observed higher rates of childhood obesity in rural areas, linked in part to lower-quality physical activity programs and nutritional standards in early care settings. Similarly, Robinson [27] identified disparities in behavioral and developmental disorders, with rural children facing higher incidence rates and reduced access to early intervention services.

Importantly, the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated pre-existing inequalities. Scholars such as Zhao et al. [10] and Eruchalu et al. [11] underscored the profound impact of digital infrastructure disparities on rural children’s ability to engage in remote learning. The rural digital divide—defined by limited broadband access, inadequate devices, and low digital literacy—amplified educational disruption and widened learning gaps [12]. These structural disadvantages were embedded within broader systemic vulnerabilities that also included socioeconomic hardship, public health inequities, and infrastructural decay, all of which disproportionately affected rural communities during the pandemic [28,29].

Emerging research has also called attention to the need for intersectional analyses. Camacho and Henderson [30] highlighted how early childhood adversity is shaped by interlocking determinants such as race, poverty, and geography. Similarly, Saatcioglu and Corus [31] and Zahnd et al. [32] emphasized the compounded vulnerabilities experienced by minority groups in rural settings, noting significant disparities in access to healthcare, education, and economic opportunity. These findings underscore the necessity of applying intersectional frameworks when analyzing rural–urban divides in ECE.

The long-term implications of early disparities are well-documented. Longitudinal studies such as those by Reynolds et al. [33] and Goodman and Sianesi [34] provide compelling evidence linking ECE participation to improved educational attainment, reduced juvenile delinquency, and higher economic productivity. Davies et al. [35] further validated the predictive power of early development indicators for later academic achievement, reinforcing the urgency of equitable ECE provision.

While some international comparisons—such as Rao et al. [36]—shed light on rural–urban ECE disparities, their applicability to the U.S. context remains limited due to differing policy environments and developmental baselines. Ghosh [37] stressed the importance of U.S.-specific analyses that account for the unique sociopolitical and demographic fabric shaping American education systems.

Recent calls for more integrated research approaches are gaining momentum. Joshi et al. [38] emphasized the need for studies that bridge disciplinary silos and systematically assess access, quality, and outcomes in tandem. Watts et al. [39] similarly advocated for disaggregated analyses that reveal intra-population differences and contextualize impact heterogeneity within ECE programs. Together, these studies highlight both the progress and the persistent gaps in understanding and addressing the rural–urban divide in ECE.

3. Methodology

3.1. Research Design and Objectives

The present study employs an integrative literature review and comparative analytical design, complemented by policy-focused synthesis to systematically investigate disparities between rural and urban ECE settings across the United States. The rationale behind selecting an integrative review methodology lies in its suitability for synthesizing comprehensive insights from diverse sources and theoretical frameworks [40,41,42]. This method allows for a robust synthesis of findings regarding systemic issues affecting rural versus urban educational provision and associated developmental outcomes. This integrative review is explicitly guided by Whittemore and Knafl’s framework for integrative reviews [43], which permits inclusion and synthesis of empirical and theoretical works across methods.

The scope of this research explicitly targets the early childhood years, defined here as ages 0–5. Early childhood is critically formative, influencing cognitive abilities, socio-emotional development, and overall life trajectories more significantly compared to later educational stages [42,44]. By focusing on early childhood, this study addresses the profound implications of foundational disparities that persist into adulthood, magnifying inequalities across educational, health, and economic domains [33,34,35].

This investigation centers specifically on the United States context, addressing unique challenges rooted in American federalism, decentralized policy implementation, and region-specific socioeconomic and infrastructural dynamics [14,18,45]. Focusing on the rural–urban dichotomy within the U.S. provides valuable insights applicable to policy reforms and targeted interventions, distinct from international comparisons, which may not effectively capture domestic complexities [36,37]. We do not apply formal comparative-education matrices; rather, we synthesize disparities thematically across rural and urban contexts.

The primary objectives of this methodological framework include:

- Identifying and synthesizing disparities in access, infrastructure, quality standards, workforce conditions, and outcomes in rural versus urban ECE settings.

- Evaluating the socio-economic and infrastructural determinants that contribute significantly to rural–urban inequalities.

- Providing comprehensive policy recommendations aimed explicitly at addressing systemic inequities in ECE.

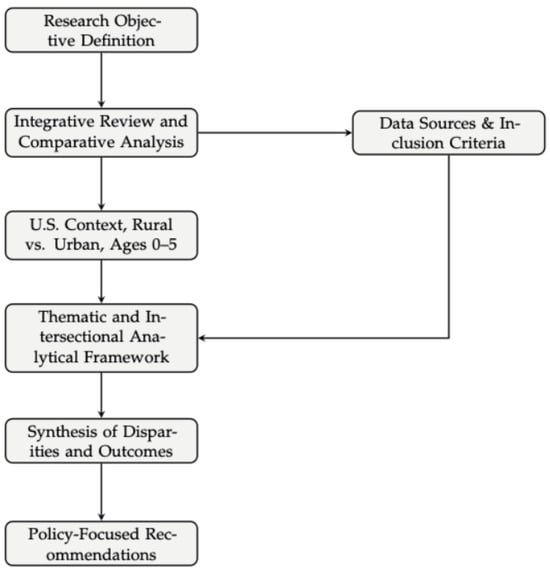

Figure 1 illustrates the detailed methodological framework and analytical logic underpinning the research design.

Figure 1.

Methodological Framework for Integrative Review and rural–urban contrastive synthesis of Rural and Urban ECE.

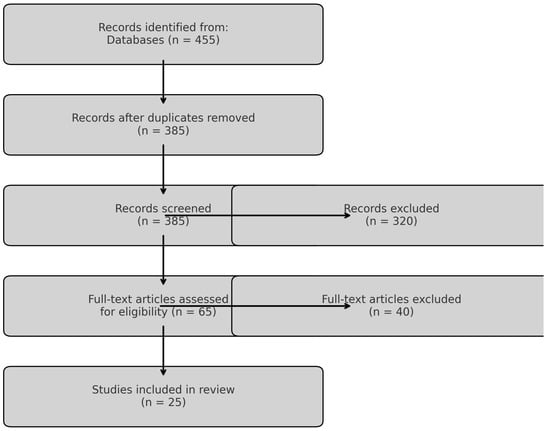

3.2. PRISMA Compliance

This integrative review was conducted in accordance with the PRISMA 2020 (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) guidelines [46]. A completed PRISMA 2020 checklist is provided in the Supplementary Materials. The article screening and selection process is visually represented using the PRISMA flow diagram (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

PRISMA 2020 flow diagram illustrating the study identification, screening, and inclusion process.

3.3. Search Strategy and Selection Process

We searched Google Scholar, ERIC, PubMed, and SpringerLink for 2000–2025 using: (“early childhood education” OR ECE) AND (rural OR urban) AND (“United States” OR USA). Language was restricted to English. Two reviewers screened titles/abstracts and full texts against pre-specified criteria; disagreements were resolved by discussion. A PRISMA 2020 flow diagram summarizes identification, screening, eligibility, and inclusion [46].

3.4. Data Sources and Inclusion Criteria

This research relies upon extensive, rigorously vetted data sources, including peer-reviewed journal articles, doctoral dissertations, federal and state education policy reports, and databases from reputable U.S. educational and governmental organizations. Specifically, peer-reviewed articles were primarily retrieved from comprehensive academic databases including Google Scholar, ERIC, PubMed, and SpringerLink, to ensure the inclusion of high-quality, evidence-based scholarly resources [47,48,49]. Rural and urban designations followed federal classifications (U.S. Census Bureau urbanized area/cluster) and, where available, NCES locale codes. We included only studies that reported outcomes by a clear rural–urban split using one of these schemes.

Federal datasets and authoritative policy documents from institutions such as the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES), the U.S. Census Bureau, Head Start programs, and state-level educational departments were integrated to enrich the empirical and policy-relevant depth of the study [23,24,25,26]. Moreover, grey literature, including policy briefs, education reform reports, and government-sponsored evaluations, was included selectively to capture practical implications and real-world policy applications.

To maintain a clear and consistent analytical scope, the following inclusion criteria were strictly applied:

- Publications and reports from 2000 to 2025 to reflect contemporary policy contexts and recent educational trends.

- Studies explicitly examining U.S.-based ECE settings with clear rural and urban comparative analyses.

- Resources focusing on children aged 0–5, explicitly addressing early developmental impacts and educational readiness outcomes.

Conversely, exclusion criteria were carefully established to maintain the analytical rigor and relevance of findings. Studies primarily focused on international contexts or exclusively addressing primary or secondary education were excluded to avoid conceptual ambiguity and ensure precise relevance

3.5. Analytical Framework

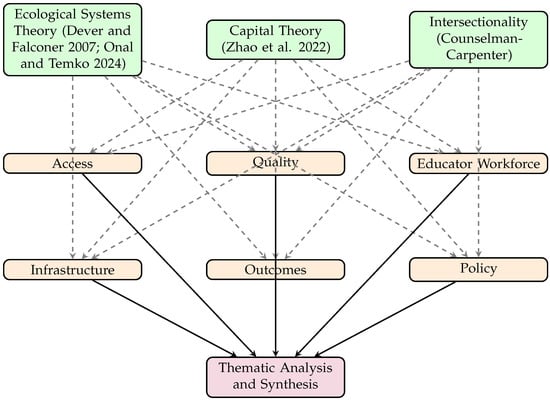

This study adopts a comprehensive analytical framework integrating Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Systems Theory, Capital Theory, and Intersectionality to holistically explore rural–urban disparities in ECE within the United States. “Developmental impacts and readiness outcomes” include cognitive (early literacy, numeracy), socio-emotional (self-regulation, prosocial behavior), physical/health (BMI, activity), and school-readiness indicators commonly used in ECE evaluations. These conceptual lenses collectively facilitate a nuanced understanding of the intricate, multilayered determinants influencing educational outcomes and systemic inequalities. We integrate Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Systems Theory [50] with Capital Theory in the sense of Bourdieu [51] and Intersectionality [52].

Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Systems Theory serves as the foundational lens for understanding the multidimensional nature of developmental influences within rural and urban settings. According to this theoretical perspective, child development is shaped by nested environmental contexts—microsystem, mesosystem, exosystem, macrosystem, and chronosystem—that interact dynamically to influence developmental trajectories [16,53]. Within the microsystem, immediate interactions in family and ECE settings influence developmental outcomes directly. The mesosystem captures interrelations between various microsystems, such as the collaboration between educators and families, significantly shaping children’s experiences. The exosystem encompasses indirect environmental influences, including regional funding mechanisms and policy decisions that profoundly impact educational resources. The macrosystem reflects broader societal values and cultural norms influencing educational prioritization and equity efforts, while the chronosystem accounts for the temporal dimensions of change, notably the COVID-19 pandemic’s significant implications for education delivery and equity [10,11].

Complementing the ecological perspective, Capital Theory further elucidates disparities observed in rural and urban ECE settings. This theory emphasizes differential access to various forms of capital—economic, social, cultural, and human—that collectively shape educational opportunities and outcomes [10,38]. For instance, rural areas typically experience limitations in economic capital due to reduced funding streams, impacting facility quality and educator compensation [23,24]. Cultural and social capital disparities manifest through limited exposure to enriched curricular experiences and professional networking opportunities for rural educators compared to their urban counterparts [20,22].

Intersectionality further enhances the analytical robustness of this study, capturing how intersecting social identities—including race, gender, socioeconomic status, and geographic location—jointly influence educational disparities [30,31,54]. Intersectional analysis acknowledges that inequities are neither uniform nor singular; rather, they emerge from the compounding and interactive effects of multiple social and systemic identities and structures. This is particularly evident in rural educational settings, where intersectionality exposes deeper layers of disadvantage experienced by minority, indigenous, and economically marginalized communities [32,55,56].

This integrative framework guides the categorization and synthesis of findings across six key comparative dimensions:

- Access: Availability, geographic proximity, enrollment capacity, and transportation infrastructure of ECE programs [2].

- Quality: Instructional standards, curriculum diversity, classroom resources, teacher-student ratios, and accreditation status [4,6].

- Educator Workforce: Professional development opportunities, compensation, credentialing, retention rates, and teacher well-being [19,49].

- Infrastructure: Physical and technological conditions, safety, sanitation, facility age, and digital connectivity [12,24].

- Outcomes: Cognitive, socio-emotional, health, and developmental benchmarks, including school readiness and longer-term educational trajectories [7,33,35].

- Policy: Effectiveness and comprehensiveness of local, state, and federal education policies and initiatives explicitly designed to mitigate rural–urban educational disparities [47,48].

The findings from the reviewed literature and data sources were systematically categorized using thematic analysis, an inductive qualitative approach that involved iterative coding and pattern identification to accurately capture emergent themes and systematic disparities. Data was organized into clearly delineated thematic clusters aligned with the comparative dimensions, ensuring analytical clarity and facilitating precise synthesis of rural–urban disparities and policy implications. We conducted thematic analysis following Braun and Clarke’s six phases [57]: (1) familiarization, (2) initial coding, (3) theme search, (4) theme review, (5) theme definition and naming, and (6) reporting. Two reviewers coded independently; discrepancies were resolved by discussion.

Figure 3 provides a detailed visual representation of the analytical framework, clearly illustrating the integration of theoretical perspectives and categorization logic underpinning this study.

Figure 3.

Integrated Analytical Framework: Ecological Systems Theory, Capital Theory, and Intersectionality Applied to Rural–Urban ECE Disparities [10,16,53,54].

This comprehensive analytical framework ensures rigorous, multidimensional analysis and robust interpretative capacity, allowing for a deeper understanding of rural–urban disparities and facilitating effective policy recommendations to address entrenched inequities in ECE.

3.6. Quality Appraisal

We appraised included studies with design-appropriate checklists (e.g., CASP for qualitative and observational designs; MMAT for mixed-methods). Appraisal outcomes informed narrative weighting but were not used to exclude studies that otherwise met inclusion criteria.

4. Results and Findings

4.1. Patterns and Trends Across ECE Dimensions

The integrative synthesis across multiple studies revealed clear patterns of persistent disparities and evolving trends characterizing rural and urban ECE in the United States. An analysis of the literature and secondary datasets indicates significant variations across multiple dimensions, as systematically summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Major Patterns and Trends in Rural and Urban ECE in the United States (2000–2025).

In the access dimension, consistent urban enrollment contrasts sharply with rural decline, exacerbated by infrastructure gaps and logistical barriers such as transportation, reflecting a persistent, widening rural–urban enrollment gap over the past two decades [2,59,60]. Notably, rural communities demonstrate surprising levels of community and familial engagement, actively supporting early education programs despite systemic access barriers [62,63].

The dimension of quality revealed significant divergences, with urban centers steadily improving curricular standards, accreditation, and instructional quality. Conversely, rural settings face chronic underfunding, negatively impacting curriculum diversity and educator qualifications, though paradoxically demonstrating notable professional dedication among educators [4,62,64].

In terms of workforce conditions, rural areas exhibit persistent instability driven by low compensation, insufficient professional development, and high attrition rates. Conversely, urban contexts consistently improve conditions, contributing to enhanced workforce stability [19,49,66]. However, notable resilience and professional commitment within rural educators emerges as a surprising trend, highlighting complex motivations beyond financial incentives alone [62].

Infrastructure disparities remain starkly evident, particularly regarding digital connectivity, which was critically tested and exposed during the COVID-19 pandemic. Urban centers rapidly enhanced digital infrastructure, whereas rural regions faced exacerbated inequalities, with limited connectivity significantly impairing educational continuity and amplifying existing disparities [10,11,12].

Child developmental outcomes continue to differ markedly. Rural populations face persistent disadvantages reflected in lower readiness scores and higher rates of obesity and developmental delays [7,33,35]. Despite these negative trends, rural communities actively pursue innovative, grassroots initiatives to improve health and developmental outcomes, underscoring local resilience [68].

Finally, in the dimension of policy and funding, urban areas benefit from consistent federal and state-level interventions, while rural ECE remains fragmented and under-resourced. Localized advocacy and community initiatives emerge strongly in rural contexts, highlighting community resilience and challenging perceptions of rural disengagement from education policy debates [22,45].

These comprehensive findings collectively underscore persistent systemic inequalities alongside remarkable local resilience and commitment, emphasizing the critical need for targeted policy interventions and robust infrastructural investments to bridge the rural–urban ECE divide effectively.

4.2. Intersectional and Systemic Challenges

Rural–urban disparities in ECE are significantly compounded by intersectional and systemic challenges related to gender, race, geography, and socioeconomic status. The intersectionality framework emphasizes how overlapping identities and societal positions shape unique experiences of disadvantage, highlighting that inequities are not uniformly distributed across rural populations [30,54,69].

Race and ethnicity emerge prominently as factors amplifying rural disparities. Minority populations, including Indigenous and immigrant communities, often experience compounded layers of disadvantage. Rural communities with high proportions of racial and ethnic minorities frequently confront intensified socio-economic hardships, systemic racism, limited cultural responsiveness in education, and constrained access to essential resources [32,55]. Such intersectional challenges have been linked to higher rates of developmental delays and academic underperformance among minority children in rural contexts, partly driven by culturally insensitive pedagogical practices and limited teacher diversity [27,30].

Gender intersects notably with geographical and racial inequalities within the rural educator workforce. Women, constituting a majority of ECE educators, particularly face lower wages, fewer career advancement opportunities, and pronounced professional isolation in rural settings. These gendered inequalities often intersect with racial and ethnic disparities, creating profound career stability challenges and significantly influencing educational quality and continuity [6,20,69].

Additionally, Indigenous populations living in rural areas face historical and contemporary marginalization reflected in educational funding inequities, curriculum misalignment with cultural values, and a lack of linguistic accommodations. Immigrant families also experience substantial hurdles accessing quality ECE services due to linguistic barriers, discrimination, legal insecurities, and lack of culturally competent resources [31,32,69].

Systemically, such intersecting disadvantages undermine equitable resource distribution and effective policy interventions. Thus, intersectionality critically enriches the understanding of systemic educational disparities, necessitating multi-layered interventions responsive to diverse identities, contexts, and community needs.

4.3. COVID-19’s Lasting Impact on Rural ECE

The COVID-19 pandemic significantly exacerbated pre-existing inequities within rural ECE, introducing unprecedented disruptions across multiple dimensions, including care delivery, educator retention, and remote learning capacities [70,71,72]. Rural communities, already constrained by infrastructural limitations, faced amplified challenges when transitioning to remote or hybrid learning modalities. Persistent broadband inadequacies, technological device shortages, and limited digital literacy substantially hindered educational continuity in rural regions, deepening existing learning gaps relative to urban counterparts [73,74,75].

Teacher attrition emerged as a critical concern, intensified by heightened professional stressors and insufficient institutional support during the pandemic. Studies consistently reported escalated physical, mental, and financial strain among rural educators, exacerbating longstanding workforce vulnerabilities, including low salaries, isolation, and limited professional development opportunities [72,76,77]. This crisis led to increased turnover, directly affecting instructional quality and educational stability in rural areas.

Additionally, young children in rural communities suffered substantial socio-emotional impacts due to pandemic-induced disruptions. Research highlighted increased incidences of behavioral and emotional distress among rural children, attributable to prolonged isolation, disrupted routines, and reduced socialization opportunities [78,79]. Early developmental assessments during and post-pandemic consistently indicated adverse developmental trajectories, disproportionately affecting disadvantaged rural populations [2,71,80].

Despite these profound challenges, evidence of resilience and adaptive strategies emerged across rural educational settings. Innovative, community-driven solutions, including localized internet access hubs, home-based learning kits, and enhanced parental engagement initiatives, demonstrated significant potential for mitigating pandemic-induced learning loss [77,81]. Moreover, rural educators frequently adapted creatively to resource constraints, utilizing informal communication channels and community networks to sustain child engagement and support families during critical disruption periods [70,73].

Table 3 synthesizes key impacts of COVID-19 on rural ECE alongside adaptive strategies and community responses, highlighting persistent inequities but also local innovations and resilience.

Table 3.

COVID-19 Pandemic Impacts and Adaptive Responses in Rural ECE.

Overall, COVID-19 served as a stark illustration of rural vulnerabilities, dramatically accentuating existing systemic and infrastructural weaknesses. Nonetheless, the adaptive resilience demonstrated by rural communities underscores significant potential for innovative, context-specific solutions and highlights the critical importance of tailored, equitable policy frameworks responsive to rural educational contexts and needs.

5. Discussion

5.1. Interpreting the Divide: Beyond Geography

The findings of this study underscore that the rural–urban divide in ECE within the United States transcends mere geographic distinctions, instead reflecting deeply entrenched structural inequities that systematically perpetuate educational disadvantage [2,82]. Structural disparities manifest through interrelated economic, infrastructural, cultural, and policy-driven mechanisms, collectively influencing differential educational opportunities and outcomes between rural and urban areas [4,83]. For instance, inadequate funding allocations and limited resource distribution consistently place rural communities at a disadvantage, perpetuating cycles of diminished access, inferior quality, and poorer developmental outcomes [23,84].

Federal initiatives, particularly Head Start, have made significant strides in addressing early educational inequalities by providing critical support for economically disadvantaged families nationwide. However, the effectiveness of such programs in rural areas has been notably constrained by systemic and logistical barriers, including inadequate infrastructure, insufficient staffing, and transportation challenges [83,84]. Morrissey et al. [2] highlight the persistent under-enrollment of rural children in Head Start programs, primarily due to geographic isolation, fragmented communication strategies, and culturally mismatched program designs. Hence, federal programs, while impactful in urban contexts, often inadequately address unique rural educational needs, indicating significant policy implementation gaps and unfulfilled potential in bridging rural–urban divides [6,85].

5.2. Policy Blind Spots and Implementation Gaps

A central finding of this review is that fragmented governance significantly exacerbates rural ECE disparities. Governance fragmentation, characterized by multiple layers of federal, state, and local authority with inconsistent coordination, creates persistent policy blind spots and implementation inconsistencies in rural communities [83,84]. This structural fragmentation not only undermines comprehensive funding allocation but also impedes coherent strategic planning specifically tailored to rural contexts, resulting in limited responsiveness to rural-specific needs and complexities [4,82].

Moreover, rural-specific ECE policy frameworks remain notably absent, further marginalizing rural populations within broader educational policy discourses. Studies consistently reveal that generalized policy solutions, predominantly crafted from urban-centric perspectives, fail to sufficiently address distinctive rural challenges, such as workforce shortages, infrastructure deficiencies, and socioeconomic vulnerabilities [86,87]. These persistent gaps highlight critical inadequacies within existing policy paradigms, necessitating targeted rural policy development to genuinely improve educational equity [88,89].

5.3. Toward a Multidimensional Model for Equity

Addressing the complexities inherent in rural–urban disparities requires the adoption of a multidimensional equity model integrating infrastructure, workforce stability, community-level partnerships, and culturally responsive education frameworks. Such a model recognizes educational equity as multi-layered and intersectional, demanding comprehensive responses across multiple domains simultaneously [54,69,87].

Infrastructural improvements, particularly digital connectivity and transportation networks, emerge as essential foundations within this multidimensional approach. Expanded broadband access, technology investments, and transportation enhancements are critical to ensuring equitable participation of rural communities in modern ECE systems, significantly facilitating access and continuity of quality education services [10,84]. Simultaneously, workforce stabilization strategies tailored explicitly for rural contexts—such as rural educator incentives, professional development opportunities, and support networks—are essential for mitigating rural workforce instability and attrition, directly enhancing education quality [6,82].

Additionally, strengthening community-level partnerships and local governance engagement remains vital for sustainable and responsive rural ECE solutions. Localized collaboration and participatory governance models can effectively address rural-specific needs, reflecting deeper community understanding, cultural relevance, and higher acceptability, ultimately fostering more resilient educational environments [22,86]. Successful community-driven initiatives observed during the COVID-19 pandemic underline the scalability potential of local adaptations, suggesting robust feasibility for broader policy integration [77,81].

Table 4 summarizes the core components and practical recommendations embedded within this multidimensional equity model, emphasizing integrated, targeted actions required to effectively bridge rural–urban divides in ECE.

Table 4.

Core Components and Recommendations of a Multidimensional Equity Model for Rural–Urban ECE.

Collectively, these recommendations articulate a cohesive, practical pathway toward equitable rural–urban educational landscapes, providing a clear policy roadmap that acknowledges and strategically addresses intersectional and systemic barriers influencing ECE outcomes in rural America. International evidence points to structurally similar access gaps. In Australia, more than nine million residents live in “childcare deserts,” highlighting geographic supply scarcities relevant to the arguments here [90].

6. Policy Recommendations

Based on the synthesis of findings and discussions of systemic rural–urban disparities, this study proposes practical, evidence-based policy recommendations designed to strategically address entrenched inequities in ECE across the United States. Each recommendation targets specific areas identified as critical for bridging the divide and ensuring long-term sustainability and equity.

6.1. Increase Federal Funding Allocations Specifically for Rural ECE

Significant evidence highlights chronic underfunding as a critical barrier to equitable rural educational provision. Increasing targeted federal funding specifically designated for rural ECE programs would significantly enhance the availability, quality, and sustainability of educational services in these communities [91,92,93]. Equitable allocation methods, such as those guided by poverty indices and educational need assessments, should underpin funding distributions to ensure resources effectively reach underserved rural populations [94,95].

6.2. Mandate Rural Representation in State Policy Consultations

Current educational policymaking disproportionately favors urban perspectives, neglecting rural-specific contexts and needs. Mandating rural representation in state-level policy consultations can significantly improve the responsiveness and effectiveness of educational policies by incorporating authentic rural voices and experiences [96,97]. Active rural participation in policy dialogues would ensure more culturally and contextually relevant educational strategies, reducing implementation gaps and enhancing policy acceptance within rural communities [84,98].

6.3. Develop Targeted Workforce Development and Teacher Retention Incentives

Addressing rural educator shortages and workforce instability requires specifically tailored incentives and retention strategies. Effective workforce policies may include rural-specific salary enhancements, professional development programs tailored to rural contexts, student loan forgiveness programs, housing allowances, and structured mentorship programs to foster career stability and professional satisfaction [82,99,100,101]. Empirical research underscores that well-designed incentives can significantly mitigate rural educator attrition, improve workforce quality, and positively impact educational outcomes [102,103,104,105,106].

6.4. Invest in Rural Digital and Physical Infrastructure for Early Education

Robust digital and physical infrastructure investments are imperative for equitable rural educational access, particularly post-COVID-19. Policymakers should prioritize rural broadband expansion, technological resources for remote learning, transportation improvements, and safe, upgraded educational facilities [107,108,109]. Strategic infrastructure investments ensure rural children can fully engage in contemporary educational experiences, significantly bridging the digital divide and enhancing overall educational resilience and equity [94,110].

6.5. Foster Public–Private-Community Partnerships to Sustain Rural Models

Sustaining rural ECE models effectively requires active public–private-community collaborations. These partnerships leverage combined resources, expertise, and community engagement, fostering sustainable solutions that accurately reflect local needs and contexts [22,86]. Policymakers should incentivize collaborative frameworks, providing fiscal and administrative support to partnerships that integrate local organizations, private stakeholders, and government agencies into unified, resilient educational networks [93,110].

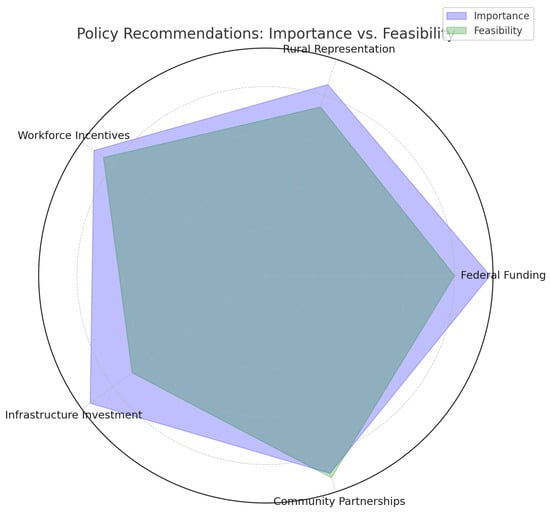

6.6. Visualization of Policy Recommendations

To enhance clarity and facilitate policy prioritization, Figure 4 visualizes the comparative importance and feasibility of each proposed recommendation. Importance reflects potential impact on reducing rural–urban disparities, whereas feasibility denotes ease of implementation considering current structural and fiscal constraints.

Figure 4.

Rural–urban contrastive synthesis of Policy Recommendations: Importance versus Feasibility.

This radar chart demonstrates that while each recommendation holds significant potential for positive impact, factors such as cost, infrastructural readiness, and administrative complexity affect their immediate feasibility. For instance, community partnerships appear both highly impactful and readily achievable, indicating a strategic starting point for rapid implementation and immediate gains in rural ECE equity.

Collectively, these evidence-informed policy recommendations articulate a clear strategic pathway for systematically addressing and ultimately bridging the persistent rural–urban divide in ECE within the United States.

7. Limitations

This synthesis relies on published English-language sources, which may bias coverage. Definitions of “rural” and “urban” vary across studies, introducing classification noise. The integrative design precludes meta-analytic effect estimation. Although we followed a structured thematic protocol, interpretive bias is possible.

8. Conclusions

This study critically investigated the complex and multidimensional disparities between rural and urban ECE settings within the United States, highlighting the intricate relationship between geographic location, systemic inequalities, and educational outcomes. The evidence reviewed underscores that the rural–urban divide is not merely geographic but deeply structural, reflecting persistent funding inequities, inadequate infrastructure, workforce instability, and insufficiently tailored policy frameworks. Consequently, addressing these profound disparities demands urgent national prioritization within educational equity and policy discourses.

The prioritization of rural ECE is imperative due to its foundational role in shaping developmental trajectories and long-term socioeconomic outcomes. The chronic underinvestment in rural early education disproportionately affects vulnerable populations, exacerbating generational cycles of disadvantage, reduced educational attainment, and diminished economic opportunities. By explicitly focusing on rural contexts, this research directly addresses a significant gap in existing scholarship, particularly the need for integrated analyses of intersectional factors such as race, ethnicity, gender, and socioeconomic status in rural educational settings. In doing so, the study contributes substantively to an enhanced understanding of the complexities underlying rural educational inequities, effectively laying groundwork for future research focused on intersectionality, rural resilience, and targeted policy interventions.

Finally, the findings presented here carry significant implications for policymakers, educational stakeholders, and community advocates, emphasizing the necessity for immediate systemic action. Effective strategies include targeted federal investment, mandated rural representation in policymaking, dedicated rural workforce incentives, strategic infrastructure improvements, and robust community partnership models. Addressing these dimensions comprehensively and concurrently will not only mitigate current disparities but also ensure sustainable, equitable educational opportunities for future rural generations. Therefore, it is imperative that policymakers and educational leaders urgently commit to substantive and transformative policy actions to realize genuine educational equity across rural and urban divides in ECE.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/soc15110307/s1.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Betancur, L.; Miller, P.; Votruba-Drzal, E. Urban-rural achievement gap in low-and middle-income countries: The role of early childhood education. Early Child. Res. Q. 2024, 66, 11–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrissey, T.W.; Allard, S.W.; Pelletier, E. Access to early care and education in rural communities: Implications for children’s school readiness. RSF Russell Sage Found. J. Soc. Sci. 2022, 8, 100–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, S.; Mikesell, M. Child care type, access, and quality in rural areas of the United States: A review. Early Child Dev. Care 2019, 189, 1812–1826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maher, E.J.; Frestedt, B.; Grace, C. Differences in child care quality in rural and non-rural areas. J. Res. Rural. Educ. Online 2008, 23, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Boutte, G.S. Urban schools: Challenges and possibilities for early childhood and elementary education. Urban Educ. 2012, 47, 515–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puma, J.; Pangalangan, J.; Farewell, C. The Well-Being of the Early Childhood Workforce: Rural and Urban Differences. Early Child. Educ. J. 2025, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson III, J.A.; Johnson, A.M. Urban-rural differences in childhood and adolescent obesity in the United States: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Child. Obes. 2015, 11, 233–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crouch, E.; Radcliff, E.; Probst, J.C.; Bennett, K.J.; McKinney, S.H. Rural-urban differences in adverse childhood experiences across a national sample of children. J. Rural. Health 2020, 36, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinkel, D.; Rech, J.P.; Guo, Y.; Bice, M.; Hulse, E.; Behrends, D.; Burger, C.; Dev, D. Examining differences in achievement of physical activity best practices between urban and rural child care facilities by age. Early Child. Educ. J. 2021, 50, 481–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Cao, C.; Li, Y.; Li, Y. Determinants of the digital outcome divide in E-learning between rural and urban students: Empirical evidence from the COVID-19 pandemic based on capital theory. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2022, 130, 107177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eruchalu, C.N.; Pichardo, M.S.; Bharadwaj, M.; Rodriguez, C.B.; Rodriguez, J.A.; Bergmark, R.W.; Bates, D.W.; Ortega, G. The expanding digital divide: Digital health access inequities during the COVID-19 pandemic in New York City. J. Urban Health 2021, 98, 183–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karamchand, G.K. Mesh Networking for Enhanced Connectivity in Rural and Urban Areas. J. Comput. Innov. 2024, 4. Available online: https://researchworkx.com/index.php/jci/article/view/72 (accessed on 21 October 2025).

- Lascarides, V.C.; Hinitz, B.F. History of Early Childhood Education; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hinitz, B.F.; Liebovich, B. History of Early Childhood Education in the United States; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Follari, L. Foundations and Best Practices in Early Childhood Education: History, Theories, and Approaches to Learning; Pearson Higher Education AU: Sydney, Australia, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Dever, M.T.; Falconer, R.C. Foundations and Change in Early Childhood Education; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Hinitz, B.S. Historical research in early childhood education. In Handbook of Research on the Education of Young Children; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2014; pp. 591–612. [Google Scholar]

- Witte, A.D.; Trowbridge, M. The structure of early care and education in the United States: Historical evolution and international comparisons. Tax Policy Econ. 2005, 19, 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez, R.E.; Kagan, S.L.; Fox, E.A. Professional development of the early childhood education teaching workforce in the United States: An overview. In The Professional Development of Early Years Educators; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2019; pp. 11–28. [Google Scholar]

- Mickelson, A.M.; Stayton, V.D.; Correa, V.I. The evolving identity of blended early childhood preparation: A retrospective history. J. Early Child. Teach. Educ. 2023, 44, 234–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, L.L.; Diaz, E.; Decker-Woodrow, L.; Baray, S. Community Approaches to Funding and Supports for High-Quality Early Care Experiences: A United States Example. In Recent Perspectives on Preschool Education and Care; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson, L.L.; Diaz, E.; Decker-Woodrow, L.; Baray, S. Community Approaches to Funding and Supports for High-Quality Early. In Recent Perspectives on Preschool Education and Care; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2024; p. 105. Available online: https://www.intechopen.com/chapters/87903 (accessed on 21 October 2025).

- Hall, J.L. The distribution of federal economic development grant funds: A consideration of need and the urban/rural divide. Econ. Dev. Q. 2010, 24, 311–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beatty, K.; Heffernan, M.; Hale, N.; Meit, M. Funding and service delivery in rural and urban local US health departments in 2010 and 2016. Am. J. Public Health 2020, 110, 1293–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.R.; Bakken, E.; Kindig, D.A.; Young, G.J. Hospital community benefit in the context of the larger public health system: A state-level analysis of hospital and governmental public health spending across the United States. J. Public Health Manag. Pract. 2016, 22, 164–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olshansky, R.B.; Johnson, L.A. The evolution of the federal role in supporting community recovery after US disasters. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 2014, 80, 293–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, L.R. Differences in health care, family, and community factors associated with mental, behavioral, and developmental disorders among children aged 2–8 years in rural and urban areas—United States, 2011–2012. MMWR Surveill. Summ. 2017, 66. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28301449/ (accessed on 21 October 2025). [CrossRef]

- Williams, L.A. A sobering examination of how the COVID-19 pandemic exacerbates the disparities of vulnerable populations. Equal. Divers. Incl. Int. J. 2021, 41, 19–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gauthier, G.R.; Smith, J.A.; García, C.; Garcia, M.A.; Thomas, P.A. Exacerbating inequalities: Social networks, racial/ethnic disparities, and the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States. J. Gerontol. Ser. B 2021, 76, e88–e92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camacho, S.; Henderson, S.C. The social determinants of adverse childhood experiences: An intersectional analysis of place, access to resources, and compounding effects. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 10670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saatcioglu, B.; Corus, C. Poverty and intersectionality: A multidimensional look into the lives of the impoverished. J. Macromarketing 2014, 34, 122–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahnd, W.E.; Murphy, C.; Knoll, M.; Benavidez, G.A.; Day, K.R.; Ranganathan, R.; Luke, P.; Zgodic, A.; Shi, K.; Merrell, M.A.; et al. The intersection of rural residence and minority race/ethnicity in cancer disparities in the United States. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, A.J.; Temple, J.A.; Robertson, D.L.; Mann, E.A. Long-term effects of an early childhood intervention on educational achievement and juvenile arrest: A 15-year follow-up of low-income children in public schools. Jama 2001, 285, 2339–2346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodman, A.; Sianesi, B. Early education and children’s outcomes: How long do the impacts last? Fisc. Stud. 2005, 26, 513–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, S.; Janus, M.; Duku, E.; Gaskin, A. Using the Early Development Instrument to examine cognitive and non-cognitive school readiness and elementary student achievement. Early Child. Res. Q. 2016, 35, 63–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, N.; Su, Y.; Gong, J. Persistent urban–rural disparities in early childhood development in China: The roles of maternal education, home learning environments, and early childhood education. Int. J. Early Child. 2022, 54, 445–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, S.S. Navigating educational inequities in the USA: A statistical analysis of socio-economic and cultural barriers faced by young adults in formal education. Stud. Educ. Adults 2024, 56, 158–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, P.; Halle, T.; Ha, Y.; Henly, J.R.; Nores, M.; Senehi, N. Advancing research on equitable access to early care and education in the United States. Early Child. Res. Q. 2025, 71, 145–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watts, T.W.; Jenkins, J.M.; Dodge, K.A.; Carr, R.C.; Sauval, M.; Bai, Y.; Escueta, M.; Duer, J.; Ladd, H.; Muschkin, C.; et al. Understanding heterogeneity in the impact of public preschool programs. Monogr. Soc. Res. Child Dev. 2023, 88, 7–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Acosta, Y.; Alsina, Á.; Pincheira, N. Computational thinking and repetition patterns in early childhood education: Longitudinal analysis of representation and justification. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2024, 29, 7633–7658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chesworth, E.; Hedges, H. Children’s interests and early childhood curriculum: A critical analysis of the relationship between research, policy, and practice. New Zealand Annu. Rev. Educ. 2024, 29, 5–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theodotou, E. If you give them the chance, they will thrive: Exploring literacy development through the arts in early childhood education. Early Years 2024, 45, 242–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whittemore, R.; Knafl, K. The integrative review: Updated methodology. J. Adv. Nurs. 2005, 52, 546–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Lin, T.J.; Glassman, M.; Ha, S.Y.; Wen, Z.; Nagpal, M.; Cash, T.N.; Kraatz, E. Linking knowledge justification with peers to the learning of social perspective taking. J. Moral Educ. 2024, 53, 321–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, C. Rurality in Public Administration: Conceptualization, Measurement, and Implications for Organizational Capacity and Networking Behavior. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Georgia, Athens, GA, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, K.; Raman, A.; Shan, F. Mapping e-learning policy in higher education: Global perspectives and emerging trends. Online J. Commun. Media Technol. 2025, 15, e202507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acton, F. Between Policy and Practice: A Qualitative Case Study Exploring the Enactment of Healthy Public Policy in Primary School Settings. Ph.D. Thesis, Anglia Ruskin Research Online (ARRO), Cambridge, UK, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Sellers, K.H. Retention Factors Influencing Early Childhood Education Teachers: A Qualitative Case Study of a Virginia Head Start Agency. Ph.D. Thesis, Trident University International, Chandler, AZ, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. The Ecology of Human Development; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu, P. The Forms of Capital. In Handbook of Theory and Research for the Sociology of Education; Richardson, J., Ed.; Greenwood, IN, USA, 1986; pp. 241–258. Available online: https://www.ucg.ac.me/skladiste/blog_9155/objava_66783/fajlovi/Bourdieu%20The%20Forms%20of%20Capital%20_1_.pdf (accessed on 21 October 2025).

- Crenshaw, K. Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex. Univ. Chic. Leg. Forum 1989, 139–167. Available online: https://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1052&context=uclf (accessed on 21 October 2025).

- Onal, S.; Temko, E. Examining the Role of Race, Gender, and Major in Engineering Major Selection Through Ecological Systems Theory Perspective. Int. J. Eng. Educ. 2024, 40, 678–701. [Google Scholar]

- Counselman-Carpenter, E. An Intersectional Approach to Human Behavior in the Social Environment. Available online: https://cognella-titles-sneakpreviews.s3.amazonaws.com/84469-1A-URT/84469-1A_SP.pdf (accessed on 21 October 2025).

- Nazari, S. The intersectional effects of race, gender, and religion on the economic integration of high-skilled immigrants: A literature review. J. Int. Migr. Integr. 2024, 25, 2213–2252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siller, H.; Aydin, N. Using an intersectional lens on vulnerability and resilience in minority and/or marginalized groups during the COVID-19 pandemic: A narrative review. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 894103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgess, K.; Chien, N.; Morrissey, T.; Swenson, K. Trends in the Use of Early Care and Education, 1995–2011: Descriptive Analysis of Child Care Arrangements from National Survey Data; Report from the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Plannng and Evaluation; US Department of Health and Human Services: Washington, DC, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Magnuson, K.; Waldfogel, J. Trends in income-related gaps in enrollment in early childhood education: 1968 to 2013. AERA Open 2016, 2, 2332858416648933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stephens, C.M.; Crosby, D.A.; Sattler, K.; Supple, A.J.; Scott-Little, C. Multidimensional patterns of early care and education access through a family centered lens. Early Child. Res. Q. 2025, 70, 133–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Rao, N.; Pearson, E. Inequality in access to early childhood care and education programs among 3-to 4-year-olds: Trends and variations across low-and middle-income countries. Early Child. Res. Q. 2024, 66, 234–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, D.; Keat, O.B.; Tarofder, A.K. Evolution and emerging themes in commitment research among early childhood educators: A bibliometric analysis. Development 2024, 8, 6241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlasov, J.; Hujala, E. Cross-cultural interpretations of changes in early childhood education in the USA, Russia, and Finland. Int. J. Early Years Educ. 2016, 24, 309–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çelik, M.; Yiğit, N.B. The global research trends on the early literacy in early childhood education. Mehmet Akif Ersoy Univ. Egit. Fak. Derg. 2024, 96–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klippen, M.I.F.; Moser, T.; Reikerås, E.; Guldbrandsen, A. A Review of Trends in Scandinavian Early Childhood Education and Care Research from 2006 to 2021. Educ. Sci. 2024, 14, 478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhang, L.; Lee, J.C.K.; Chen, J. A Systematic Review of Research Patterns and Trends in Early Childhood Education Teacher Well-Being from 1993 to 2023: A Trajectory Landscape. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cochran, M. International perspectives on early childhood education. Educ. Policy 2011, 25, 65–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Purkait, T.; Dev, D.A.; Srivastava, D.; Franzen-Castle, L.; Nitto, A.M.; Kenney, E.L. Are food and nutrition assistance programs fostering an equitable early care and education (ECE) food environment? A systematic review utilizing the RE-AIM framework. Early Child. Res. Q. 2025, 70, 30–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, S.H. Towards an Intersectional Politics for Early Childhood Education Workforce Reform. 2019. Available online: https://scholarworks.calstate.edu/downloads/k06989248 (accessed on 21 October 2025).

- Timmons, K.; Cooper, A.; Bozek, E.; Braund, H. The impacts of COVID-19 on early childhood education: Capturing the unique challenges associated with remote teaching and learning in K-2. Early Child. Educ. J. 2021, 49, 887–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hobbs, A.; Bernard, R. Impact of COVID-19 on Early Childhood Education and Care. Educ. J. Rev. 2021, 27. Available online: https://post.parliament.uk/impact-of-covid-19-on-early-childhood-education-care/ (accessed on 21 October 2025).

- Lewis, I.M. The Unprecedented Stressors of Early Childhood Educators During the COVID-19 Pandemic and Post-Pandemic Restoration: A Case Study. Doctor’s Thesis, Liberty University, Lynchburg, VA, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Ford, T.G.; Kwon, K.A.; Tsotsoros, J.D. Early childhood distance learning in the US during the COVID pandemic: Challenges and opportunities. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2021, 131, 106297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Montoya, E.; Austin, L.J.; Powell, A.; Muruvi, W. Early Care and Education Programs During COVID-19: Persistent Inequities and Emerging Challenges. 2022. Available online: https://escholarship.org/uc/item/5mm8m1x9 (accessed on 21 October 2025).

- Cascio, E.U. COVID-19, Early Care and Education, and Child Development. 2021. Available online: https://www.nber.org/sites/default/files/2021-10/cascio_seanWP_oct2021_revised.pdf (accessed on 21 October 2025).

- Swigonski, N.L.; James, B.; Wynns, W.; Casavan, K. Physical, mental, and financial stress impacts of COVID-19 on early childhood educators. Early Child. Educ. J. 2021, 49, 799–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, L.; Hodgen, E.; Meagher-Lundberg, P.; Wells, C. Impact of COVID-19 on the Early Childhood Education Sector in Aotearoa New Zealand: Challenges and Opportunities; Wilf Malcolm Institute of Educational Research (WMIER): Hamilton, New Zealand, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Watts, R.; Pattnaik, J. Perspectives of parents and teachers on the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on children’s socio-emotional well-being. Early Child. Educ. J. 2023, 51, 1541–1552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matters, I.W.E.C. Early Childhood Development: Impact and Implications of the COVID-19 Pandemic1. In The COVID-19 Generation Children and Youth in and After the Pandemic; p. 52. Available online: https://www.pass.va/content/dam/casinapioiv/pass/pdf-volumi/studia-selecta/studiaselecta09pass.pdf#page=53 (accessed on 21 October 2025).

- Mokibelo, E.B. Impact of COVID-19 on Early Childhood Education in Botswana. E. Afr. J. Educ. Stud. 2024, 7, 539–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruening, M.; Nadalet, C.; Ashok, N.; Suh, B.C.; Lee, R.E. Preschoolers’ parent and teacher/director perceptions of returning to early childcare education during the COVID-19 pandemic. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 2270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannaway, D.; Govender, P.; Marais, P.; Meier, C. Growing early childhood education teachers in rural areas. Afr. Educ. Rev. 2019, 16, 36–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paschall, K.; Halle, T.; Maxwell, K. Early Care and Education in Rural Communities. OPRE Research Brief 2020-62; Office of Planning, Research and Evaluation: Washington, DC, USA, 2020.

- Vilches, S.L.; Pighini, M.J.; Stewart, M.J.; Rossa-Roccor, V.; McDaniel, B. Preparing early childhood educators/interventionists: Scoping review insights into the characteristics of rural practice. Rural. Spec. Educ. Q. 2023, 42, 17–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okeke, C.; Thomas, A. Challenges in the Provision of Early Childhood Care and Education in Rural Areas In Gboko, Benue State, Nigeria. Webology 2024, 21. Available online: https://www.webology.org/data-cms/articles/20240116110928amWEBOLOGY%2021%20(1)%20-%203.pdf (accessed on 21 October 2025).

- Rey, R.; Manta, O. Rural-Urban Partnership, Challenges, and Opportunities in the Current Multi-Crisis Context. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Economic Scientific Research-Theoretical, Empirical and Practical Approaches; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2023; pp. 745–762. [Google Scholar]

- Rajendran, L.P.; Raúl, L.; Chen, M.; Andrade, J.C.G.; Akhtar, R.; Mngumi, L.E.; Chander, S.; Srinivas, S.; Roy, M.R. The ‘peri-urban turn’: A systems thinking approach for a paradigm shift in reconceptualising urban-rural futures in the global South. Habitat Int. 2024, 146, 103041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosa, W.E.; Ahmed, E.; Chaila, M.J.; Chansa, A.; Cordoba, M.A.; Dowla, R.; Gafer, N.; Khan, F.; Namisango, E.; Rodriguez, L.; et al. Can you hear us now? Equity in global advocacy for palliative care. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2022, 64, e217–e226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Homer, C.S.; Castro Lopes, S.; Nove, A.; Michel-Schuldt, M.; McConville, F.; Moyo, N.T.; Bokosi, M.; ten Hoope-Bender, P. Barriers to and strategies for addressing the availability, accessibility, acceptability and quality of the sexual, reproductive, maternal, newborn and adolescent health workforce: Addressing the post-2015 agenda. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2018, 18, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Institute, M. Childcare Deserts and Oases: How Accessible Is Childcare in Australia? 2022. Available online: https://www.vu.edu.au/mitchell-institute/early-learning/childcare-deserts-oases-how-accessible-is-childcare-in-australia (accessed on 21 October 2025).

- Davis, E.E.; Sojourner, A. Increasing Federal Investment in Children’s Early Care and Education to Raise Quality, Access, and Affordability; Hamilton Project: Washington, DC, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Hustedt, J.T.; Barnett, W.S. Financing early childhood education programs: State, federal, and local issues. Educ. Policy 2011, 25, 167–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schilder, D.; Dow, D.; Wagner, L.; Bose, S.; Isaacs, J.; Mefferd, E.; Norwitt, J. Accessing and Strategically Using Federal Funds for ECE Systems and Workforce Compensation; Urban Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Banghart, P.; Guerra, G.; Daily, S. Strategies to Guide the Equitable Allocation of COVID-19 Relief Funding for Early Care and Education; Child Trends: Rockville, MD, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Hollett, K.B.; Frankenberg, E. A critical analysis of racial disparities in ECE subsidy funding. Educ. Policy Anal. Arch. 2022, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickson, W.R. Involvement by Decree: Citizen Involvement in Education by Legislative Mandate; The Ohio State University: Columbus, OH, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Bown, K.; Sumsion, J. Generating visionary policy for early childhood education and care: Politicians’ and early childhood sector advocate/activists’ perspectives. Contemp. Issues Early Child. 2016, 17, 192–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engel, A.; Barnett, W.S.; Anders, Y.; Taguma, M. Early Childhood Education and Care Policy Review; OECD: Norway, 2015; Available online: https://www.scribd.com/document/822364803/Early-Childhood-Education-and-Care-Policy-Review-Norway (accessed on 21 October 2025).

- Garavuso, V. Reimagining teacher education to attract and retain the early childhood workforce: Addressing the needs of the “nontraditional” student. In Handbook of Early Childhood Teacher Education; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2015; pp. 181–194. [Google Scholar]

- Bridges, M.; Fuller, B.; Huang, D.S.; Hamre, B.K. Strengthening the early childhood workforce: How wage incentives may boost training and job stability. Early Educ. Dev. 2011, 22, 1009–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaack, D.D.; Donovan, C.V.; Adejumo, T.; Ortega, M. To stay or to leave: Factors shaping early childhood teachers’ turnover and retention decisions. J. Res. Child. Educ. 2022, 36, 327–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorpe, K.; Jansen, E.; Sullivan, V.; Irvine, S.; McDonald, P.; Early Years Workforce Study team Thorpe Karen Irvine Sue McDonald Paula Lunn Joanne Sumsion Jennifer Ferguson Angela Lincoln Mary Liley Kate Spall Pam. Identifying predictors of retention and professional wellbeing of the early childhood education workforce in a time of change. J. Educ. Chang. 2020, 21, 623–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryant, D.; Yazejian, N.; Jang, W.; Kuhn, L.; Hirschstein, M.; Hong, S.L.S.; Stein, A.; Bingham, G.; Carpenter, K.; Cobo-Lewis, A.; et al. Retention and turnover of teaching staff in a high-quality early childhood network. Early Child. Res. Q. 2023, 65, 159–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Totenhagen, C.J.; Hawkins, S.A.; Casper, D.M.; Bosch, L.A.; Hawkey, K.R.; Borden, L.M. Retaining early childhood education workers: A review of the empirical literature. J. Res. Child. Educ. 2016, 30, 585–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitebook, M. Building a Skilled Teacher Workforce; Center for the Study of Child Care Employment, University of California, Berkeley: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2014; Volume 21, p. 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Hur, E.H.; Ardeleanu, K.; Satchell, T.W.; Jeon, L. Why are they leaving? Understanding Associations between early childhood program policies and teacher turnover rates. In Proceedings of the Child & Youth Care Forum; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2023; Volume 52, pp. 417–440. [Google Scholar]

- Waluyo, E.; Handayani, S.S.D.; Diana, D. The Portrait of Rural Early Childhood Education (ECE) Quality in the Digital Era After One Village One ECE Policy Program. In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Early Childhood Education. Semarang Early Childhood Research and Education Talks (SECRET 2018), Bandung, Indonesia, 7 November 2018; Atlantis Press: Paris, France, 2018; pp. 231–235. [Google Scholar]

- Aina, A.Y.; Bipath, K. Availability and use of infrastructural resources in promoting quality early childhood care and education in registered early childhood development centres. S. Afr. J. Child. Educ. 2022, 12, 980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borisova, I.; Lin, H.C.; Hyson, M. Build to Last: A Framework in Support of Universal Quality Pre-Primary Education; UNICEF: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Duer, J.K.; Jenkins, J. Paying for preschool: Who blends funding in early childhood education? Educ. Policy 2023, 37, 1857–1885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).