Abstract

Electoral abstention has emerged as a critical challenge to democratic legitimacy, with rising rates observed globally. For example, in Portugal, the turnout declined from 91.5% in 1975 to 51.4% in 2022. This systematic review synthesizes multidisciplinary literature to identify key determinants of voter nonparticipation and their interactions, aiming to inform adaptive strategies to enhance civic engagement amid social, organizational, and technological changes. Following PRISMA guidelines, we searched five databases (Academic Search Complete, MEDLINE, Psychology and Behavioral Sciences Collection, PsycINFO, and Web of Science) from 2000 to August 2025 using terms such as “electoral abstention” and “non-voting.” Inclusion criteria prioritized quantitative empirical studies in peer-reviewed journals in English, Portuguese, Spanish, or French, yielding 23 high-quality studies (assessed via MMAT, with scores ≥ 60%) from 13 countries, predominantly the USA and France. Results reveal abstention as a multidimensional phenomenon driven by three interconnected categories: individual factors (e.g., health issues like smoking and mental health trajectories, institutional distrust); institutional factors (e.g., electoral reforms such as biometric registration reducing abstention by up to 50% in local contexts, but with mixed outcomes in voluntary voting systems); and contextual factors (e.g., economic inequalities and urbanization correlating with lower turnout, exacerbated by events like COVID-19). This review underscores the need for integrated public policies addressing these factors to boost participation, particularly among youth and marginalized groups. By framing abstention as an adaptive response to contemporary challenges, this work contributes to the political psychology and democratic reform literature, advocating interdisciplinary approaches to resilient electoral systems.

1. Introduction

Competitive elections are a fundamental feature of representative democracy. By linking citizens to decision-makers, elections enable voters to hold their representatives accountable [1]. However, electoral abstention rates have risen sharply worldwide, signaling a significant disengagement from the democratic process. This trend has profound implications for the legitimacy and functioning of democracies. Electoral participation and abstention are two sides of the same coin, reflecting citizens’ perceptions of and engagement with political systems [2]. Democratic stability relies on a balance between active citizen participation and the passivity of others. The issue is not ensuring universal participation but rather safeguarding the opportunity to engage [3]. Portugal offers a compelling case for studying electoral participation. Following exceptionally high voter turnout in its inaugural democratic elections—an achievement that surprised even seasoned scholars of democratization [4]—the subsequent decades saw a sharp decline in voter engagement [5]. As detailed on the [6], abstention rates in parliamentary elections rose from 8.5% in 1975 to 48.6% in 2022, marking an increase of 40.1 percentage points over 47 years. Additionally, only about 20% of respondents report abstaining, revealing a notable gap between self-reported and actual abstention rates [7]. Similarly, Norway and Portugal stand out for having high levels of abstention [8]. In the United Kingdom in 2005, only 37% of registered young people exercised their right to vote [9]. In Switzerland, the average voter turnout was only 32% in the 63 elections held over the last 25 years [10]. In the Republic of Ireland in 1996, according to the CENSUS, abstention reached 65.92% in the 1997 elections, reflecting a worrying lack of civic engagement [11]. As in Chile, voter abstention has become a significant problem in Spain. For example, in the municipal elections of May 2011, the abstention rate was 33.8%, as reported on the website of the Spanish Ministry of the Interior [12]. In the general elections in November of the same year, the abstention rate was 31.1%, despite a study by the Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas published in October indicating that 83.6% of those interviewed intended to vote [13]. However, the highest abstention rate is observed during the process of choosing representatives for the European Parliament. In the most recent elections held on 25 May 2014, 56.2% of eligible voters chose not to participate [14]. This leads us to the worrying conclusion that it is no longer the majority of the people who are speaking out, but the majority of the minority [10], a potential symptom of wider problems and a threat to the legitimacy of democracy [15]. These patterns of electoral disengagement highlight the urgency of understanding the factors that contribute to abstention across various democratic contexts. Such insights are crucial for fostering more active and informed citizen participation.

1.1. Investigations Already Carried out into the Causes of Electoral Abstention

Although most studies have focused on the analysis of voting behavior, to the detriment of abstention behavior, some work in this area has already been developed, with a view to characterizing the different types of abstention/abstentionism, e.g., [16,17]. Electoral Abstention has been linked to several factors, such as low social trust and less concern for health policies [11,18]. A significant and positive association has been identified between distrust in institutions and the propensity to abstain [19,20,21]. Individuals subject to greater economic disparities are less likely to participate in voting [22,23,24]. Other reasons include disappointment with the political system or a lack of clear candidate preference [14]. Abstentionism and null voting are considered (ineffective) forms of electoral participation, as indicated by [25]. When the political divide between left and right becomes less evident, the costs of understanding political debates increase, leading to greater electoral abstention [26]. The public declaration of the intention to vote or not has a concrete effect on voting behavior [10]. In addition, social belonging mitigates electoral abstention [27]. Abstention is interpreted as a significant change in attitude, marked by the context of political disaffection, serving as a punitive means or an expression of discontent with the political class [28]. It has also been observed that voters with a lower level of education or who are younger tend to participate less actively in the electoral process [29]. However, the results relating to gender have yielded a variety of conclusions: women tend to abstain from voting more often, e.g., [10,30], whereas there are no significant gender differences in electoral participation, e.g., [14]. However, the influence of age as a determining factor in electoral abstention is consistent across the available literature, with some authors claiming that this effect is more significant among young people under 30, e.g., [31,32,33]. Low electoral participation among young people is currently a central concern in many democratic countries [17]. These diverse elements provide a comprehensive view of the factors that influence electoral abstention and highlight the complexity underlying this phenomenon.

1.2. Electoral Abstention in Portugal

Social class and educational level are among the most frequently analyzed factors in empirical studies of electoral participation [5]. In Portugal, however, the results of these investigations reveal an intriguing and sometimes contradictory complexity. The existing literature suggests that, unlike other democracies, the relationship between the level of education and the propensity to vote is not clearly delineated [34,35]. As far as social class is concerned, ref. [30] highlights a significant increase in the electoral participation gap between the more affluent and less privileged social strata. Service workers are more likely to abstain, while managers and socio-cultural agents are substantially more inclined to actively participate in the electoral process. This socio-economic disparity in electoral participation raises pertinent questions about the fairness of exercising the right to vote. Contrary to some expectations, research conducted by [36,37] does not identify significant gender disparities in electoral participation in Portugal. Ref. [38] argues that contemporary Portuguese society is characterized by a “distance to power” syndrome, manifested in dissatisfaction with the electoral offer and limited identification with political parties. The trajectory of electoral participation in Portugal resembles, in many respects, that observed in third-wave democracies: founding elections marked by high participation have given way to a progressively alienated electorate. Against this backdrop, there is a pressing need for collaborative efforts between public, academic, and private actors to produce new data [5].

Research Objectives

A systematic review is a widely recognized method for synthesizing literature, offering a structured approach to analyze existing knowledge [39]. This study aims to systematically review the literature on electoral abstention, consolidate current findings, identify research gaps, and advance understanding of this complex phenomenon. By doing so, it seeks to inform future research and interventions aimed at enhancing democratic participation. This systematic review examines electoral abstention as a manifestation of adaptation to contemporary societal changes, including social inequalities, electoral system reforms, and technological innovations such as biometric registration. By highlighting how individuals and institutions respond to challenges such as economic disparities and pandemics (e.g., COVID-19), this work aligns with the Special Issue’s focus on social, organizational, and technological responses to emerging issues, offering insights into how to enhance democratic participation in times of flux.

2. Materials and Methods

This systematic review was conducted following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [40]. The protocol was registered in PROSPERO (ID: CRD42023434003) and is publicly available online [41].

2.1. Research Strategy and Study Identification

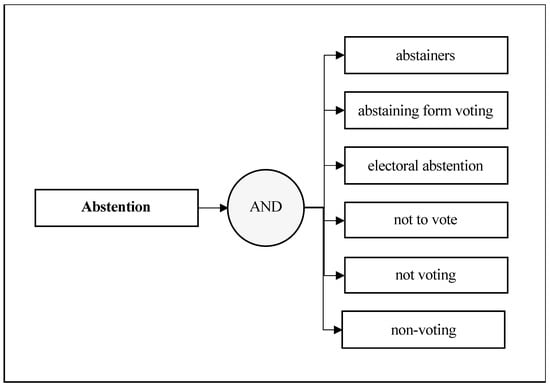

Before starting the systematic review, a panel of experts was formed to establish selection and rejection criteria and the variables to be analyzed. Using the iterative process of definition, clarification, and refinement proposed by [42], a protocol was drafted and published in PROSPERO under the ID CRD4202343400 [41]. The protocol is also publicly available at https://abstencao-eleitoral.webnode.pt/protocolo-prospero/ (accessed on 21 June 2023). This protocol details the search strategy, the electronic databases to be consulted, the start date of the work, the internet browser used, the search languages, the search method, the terms used, the time range, and the inclusion and rejection criteria. We adopted the PICO structure (Population, Intervention or exposure, Comparison intervention or exposure, Outcome), following the approach recommended for systematic reviews and meta-analyses, as exemplified by [43]. The search was carried out through the title (TI) using the central word “abstention”, combined individually with the logical operator “AND” and the following terms: “abstainers”, “abstaining from voting”, “electoral abstention”, “not to vote”, “not voting”, and “non-voting” (see Figure 1). This research is exploratory and descriptive.

Figure 1.

Keywords and combinations using the logical operator “AND”.

The keyword search was conducted using the Title (TI) criterion, covering the period from January 2000 to August 2025 (chronological parameter). The choice of such a broad time interval aims to cover as many articles as possible on the relatively recent topic of Electoral Abstention. We used the Brave web browser and Windows. Five electronic databases were used for the comprehensive search: Academic Search Complete (ASC), MedLine (ML), Psychology and Behavioral Sciences Collection (PBSC), PsycINFO (PINF), and Web of Science (WS). The diversity of these data sources aims to ensure a comprehensive and representative collection of articles on Electoral Abstention.

2.2. Eligibility Criteria/Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

The criteria for the inclusion of articles in this systematic review were as follows: (a) the studies should be based on original empirical research; (b) the publication should take place in peer-reviewed journals; (c) the articles should address research on electoral abstention and non-voting behavior; (d) quantitative empirical studies were prioritized. On the other hand, the following were excluded: (a) articles and theoretical studies; (b) opinion pieces; (c) studies published in book chapters; (d) articles in languages other than English, Portuguese, Spanish, or French (see Table 1). The rigorous application of these criteria resulted in the selection of 60 articles for analysis in the systematic review.

Table 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria were used to select participants.

2.3. Quality of Measurements

Quality assessment employs specialized tools that promote transparency and replicability in systematic literature reviews (SLRs), thereby ensuring the overall transparency of the review process. In the present work, the methodological quality of the included studies was assessed and documented using criteria from the MIXED METHODS APPRAISAL TOOL—MMAT [44]. The MMAT [44] was selected as the primary quality assessment tool due to its suitability for systematic reviews, enabling consistent and comparable application across the entire corpus of included studies. To apply MMAT, the researcher initially addressed two screening questions for each included study; if the response was “No” or “Can’t tell” to one or both questions, further methodological appraisal was considered neither feasible nor appropriate. Subsequently, the appropriate study category was selected, and the methods described in the study were critically analyzed. The MMAT encompasses five types of studies, with each type evaluated using five specific criteria, rated as “Yes” (1 point), “No” (0 points), or “Can’t tell” (0 points), resulting in an overall assessment score ranging from 0 to 5 points [44].

The MMAT does not define cut-off values, so the researchers characterized the studies. We used the same criteria as in other systematic reviews, such as [45], in which the final score was presented as a percentage: 0 = 0%, 1 = 20%, 2 = 40%, 3 = 60%, 4 = 80%, and 5 = 100%. The criteria for selecting the included studies were: (1) low-quality studies were those with a score below 50%; (2) medium-quality studies had a score between 50% and 80%; and (3) high-quality studies had a score equal to or greater than 80% [45].

Only six studies scored 60% and all the others scored 80%.

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection

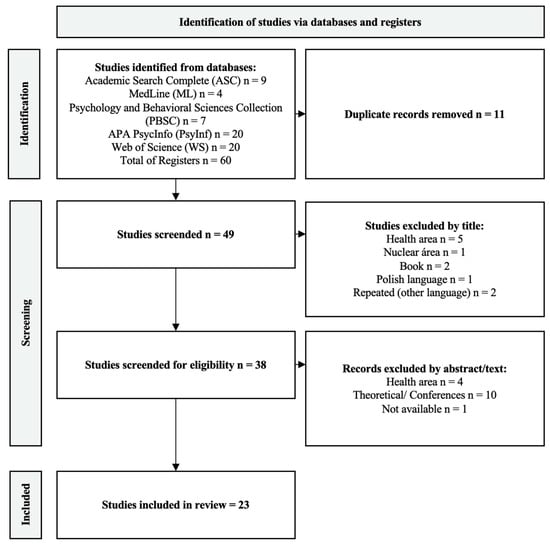

As shown in Figure 2, we identified 60 articles. The Academic Search Complete (ASC) database contributed nine articles, MedLine (ML) provided four articles, Psychology and Behavioral Sciences Collection (PBSC) identified 7, PsycINFO (PINF) presented 20 articles, and Web of Science (WS) provided 20 articles. However, we observed the duplication of 11 papers, resulting in the analysis of 49 articles. In an initial analysis of titles and abstracts, we excluded 11 articles. We then assessed the full texts of the remaining 38 articles. After this initial exploration, 15 studies were excluded because they did not meet the inclusion criteria, resulting in an analysis corpus of 23 studies in this systematic review (see Figure 2 for details).

Figure 2.

Flowchart of systematic review.

3.2. Data Extraction

We established a set of descriptive variables to characterize each of the 23 studies considered eligible for the review (see Table 2, Summary of Included Studies). These variables include information on the authors, year of publication, main objective, conclusions, sample size, language of publication, country of origin of the study, and quality assessment (see Appendix A—Table A1: Detailed Characteristics of Included Studies).

Table 2.

Summary of Included Studies.

Table 2.

Summary of Included Studies.

| Authors (Year) | Objective | Key Findings | Country |

|---|---|---|---|

| [8] | Effects of institutional incentives on abstention | Incentives affect privileged voters more; varied impact | Western Europe |

| [46] | Candidate strategies and voter alienation | Split votes motivate alienation; effect on turnout | USA |

| [47] | Psychological reasons for voting versus abstention | Personal relevance increases turnout; voter illusion explained | USA |

| [10] | University student voting interventions | Interventions increased the turnout of students | France |

| [23] | Economic inequality and voter turnout | Higher inequality correlates with lower turnout | USA |

| [48] | French electoral reform and the abstention rate | Reform reduced abstention locally, but with mixed results | France |

| [24] | Urbanization and differential abstention | Higher abstention in urbanized areas | Spain |

| [25] | Effectiveness of abstention and invalid votes | Abstention and null votes are ineffective; consider reforms | Mexico |

| [28] | Latent causes of abstention in European elections | Abstention linked to political disaffection | Spain |

| [19] | Institutional quality and political trust | Distrust is linked to higher abstention | Europe |

| [14] | Youth political participation and electoral abstention | Traditional voting down; unconventional participation up | Chile, Spain |

| [21] | Electoral abstention in the border municipality: institutional distrust | Distrust and government evaluation relate to higher abstention | Mexico |

| [26] | Ideology and political disengagement | Blurred ideologies increase abstention costs | France |

| [18] | Investigate smoking and political abstention; trust as mediator | Smokers are less likely to vote; trust mediates abstention | USA |

| [22] | Vote-buying impact | Vote buying reduces accountability; variable effects | Turkey |

| [49] | Impact of voluntary voting and automatic registration | Reform reduced turnout by 5% but decreased age bias by 39% | Chile |

| [46] | COVID-19 and the conservative vote increase | The pandemic increased conservative support; its electoral impact | France |

| [27] | Populism and social belonging | Belonging reduces abstention; mixed influence on populism | Europe |

| [50] | Biometric updating and local turnout changes | Update reduced abstention; increased education spending | Brazil |

| [51] | Geographic effects of the economic crisis on abstention | Economic shocks caused differentiated abstention spikes | Greece |

| [52] | Mental health trajectories and voting | Childhood mental health issues predict lower voting | UK |

| [53] | Effect of election frequency on abstention | Frequent elections increase the acceptability of abstention | Czechia, France, Poland, Slovakia |

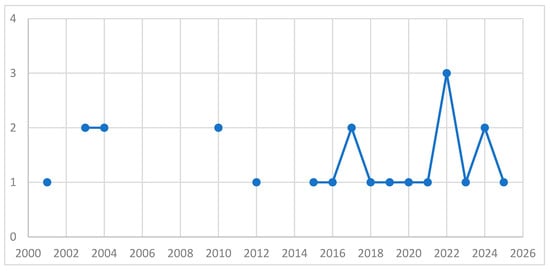

The majority of papers were published in the United States (n = 4) and France (n = 4) (see Table 3). Regarding language, despite the geographical diversity of publications, most articles were written in English (n = 15) (see Table 3). The earliest paper was published in 2001, and we observed an increase in publications from 2016 onwards, demonstrating the growing relevance of this topic (Figure 3).

Table 3.

Countries of the publications (n = 11).

Figure 3.

Publication per year: from 2000 to 2025.

Although the final corpus includes 23 studies from 13 countries, there is a geographical (4 studies from the US and 4 from France) and linguistic (18 in English) concentration, reflecting the limitations of the databases consulted (ASC, Medline, PBSC, PsycINFO, and Web of Science). This distribution, while capturing trends in Western democratic contexts, may limit generalization to underrepresented regions such as Asia or Africa [54]. However, the increase in publications since 2016 (Figure 3) indicates the growing relevance of the topic, with adequate synthesis to identify multidisciplinary patterns.

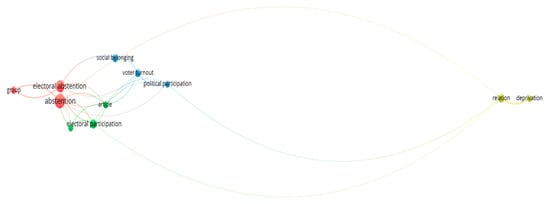

Figure 4 presents a neural network analysis developed to synthesize the content of the 23 studies reviewed. The network was constructed using topic modeling techniques, representing thematic clusters derived from the key terms and concepts identified in the studies. The edges indicate the strength of co-occurrence or thematic similarity, measured by similarity metrics. The visualization was performed using VOSviewer software v1.6.20. The interpretation focuses on identifying central themes (e.g., social belonging) and their interconnections, and on elucidating the multidimensional factors underlying electoral abstention.

Figure 4.

Neural network representation of the contents of the articles under analysis.

This systematic review illustrates the multifaceted nature of electoral abstention (Figure 4). The results are organized into three categories to clarify the relationships between the articles: individual, institutional, and contextual factors (Table 4).

Table 4.

Categorized Synthesis of Key Factors Influencing Electoral Abstention.

Table 4.

Categorized Synthesis of Key Factors Influencing Electoral Abstention.

| Category | Key Factors | Key Studies (Examples) | Key Relationships |

|---|---|---|---|

| Individual Factors | Health (e.g., smoking, impact of COVID-19); Trust (e.g., distrust of institutions) | [11,21,46] | Low confidence and health problems reduce voting likelihood, while personal attitudes such as political discontent can lead to abstention as a form of protest. |

| Institutional Factors | Electoral systems (e.g., voluntary voting, automatic registration, biometric updates) | [48,49,50] | Reforms such as biometric registration in Brazil reduce abstention in local elections, but effects vary; institutional mistrust amplifies abstention in systems perceived as ineffective. |

| Contextual Factors | Economic inequality; Urbanization | [22,23,24] | Economic inequalities and urbanization correlate with lower turnout, especially in areas with high income disparities, where abstention reflects social alienation. |

3.3. Individual Factors

Factors such as health and trust emerged as significant themes. Studies highlight associations between behaviors such as smoking and a lower likelihood of voting, due to low social trust or dissatisfaction with health services. The COVID-19 pandemic disrupted electoral behavior, leading to greater support for conservative parties. These patterns underscore the need for research on the intersection between public health and political participation through voting. Recent studies reinforce this perspective, with [52] demonstrating that children’s mental health impacts intergenerational patterns of abstention, and [53] identifying electoral fatigue as a mediating mechanism of individual disengagement in contexts of political instability.

3.4. Institutional Factors

Reforms in electoral systems impact voter turnout. Articles on automatic voter registration, voluntary voting, and technological updates (e.g., biometrics in Brazil) show mixed results. While some reforms reduce local voter abstention, others reveal inconsistent effects, highlighting the need for context-sensitive strategies. Additionally, ref. [51] analyzes how post-economic crisis institutional reforms in Greece exacerbate inequalities in voting accessibility.

3.5. Contextual Factors

Factors such as economic inequality and psychosocial dynamics play pivotal roles. Economic disparities, especially in states with high income inequality, and psychosocial variables such as sense of belonging and urbanization, shape abstention behavior, with urbanized areas exhibiting higher rates of differential abstention. For example, ref. [51] links the Greek economic crisis to increases in abstention among vulnerable populations.

4. Discussion

This systematic review sheds light on a wide array of factors associated with electoral abstention, illustrating the multifaceted nature of this phenomenon (Figure 4). The findings reveal intersections between health, incentives, trust in institutions, system reforms, and contextual factors, emphasizing the complexity of non-voting behavior and its broader implications. Health-related factors emerged as a significant theme, with studies highlighting associations between behaviors such as smoking and a lower likelihood of voting. These patterns may be partially attributed to diminished social trust or dissatisfaction with health services, as evidenced by the relationship between voting for left-wing parties and negative evaluations of healthcare. Additionally, the COVID-19 pandemic was identified as a contextual disruptor, with potential implications for voter behavior, including increased support for conservative parties. These findings underline the need for further research into the interplay between public health and political participation. Incentive-driven electoral participation was also explored, revealing that while incentives do not drastically alter abstention rates, they foster reciprocity and bolster turnout among disadvantaged voter groups that traditionally exhibit lower participation rates. This suggests that targeted policies could mitigate abstention among specific demographics, potentially narrowing participation gaps. Trust in democratic institutions surfaced as a critical determinant of voter engagement. A lack of institutional trust was consistently linked to higher abstention rates, with voters perceiving abstention or casting null votes as mechanisms to express dissatisfaction with government performance and party representation. However, the simultaneous rise in unconventional political activities, especially among youth, indicates a shift in engagement modalities. The work of Sola-Morales and Hernández-Santaolalla [14] underscores this transition, showing that young individuals, while disenchanted with traditional voting, remain civically active through alternative channels. Electoral system reforms and their impact on participation were another key area of inquiry. Articles addressing automatic voter registration, voluntary voting, and technological updates, such as biometric registration in Brazil, demonstrated mixed results. While some reforms reduced abstention in local elections, others revealed inconsistent effects, underscoring the need for context-sensitive electoral strategies. Finally, contextual factors like economic inequality and psychosocial dynamics also play pivotal roles—economic disparities, particularly in states with pronounced income inequality, correlated with reduced voter turnout. Moreover, psychosocial variables such as a sense of belonging and urbanization were found to shape abstention behavior, with urbanized areas exhibiting higher rates of differential abstention. These findings advocate for a multidisciplinary approach to understanding abstention, integrating economic, social, and political perspectives to account for its diverse drivers. Interestingly, the review noted a marked increase in scholarly attention to electoral abstention since 2016, highlighting its growing relevance in contemporary political discourse. This expanding body of literature underscores the urgency of addressing abstention through innovative research and policies that account for evolving patterns of political engagement, particularly among younger generations and students. In conclusion, this review demonstrates that electoral abstention is not a monolithic phenomenon but rather a complex interplay of individual, institutional, and contextual factors. The multifaceted drivers of abstention—spanning health, trust, and economic factors—call for an interdisciplinary lens that integrates sociology, psychology, political science, and technology studies. For instance, technological responses, such as biometric updates in Brazil, illustrate organizational adaptations to reduce abstention, while social responses, such as incentive programs, address inequalities in participation. This approach underscores the need for holistic strategies to foster civic engagement amid contemporary challenges. Future research must continue to explore these dynamics, with an emphasis on the changing landscape of political participation and its implications for democratic representation.

4.1. Practical Implications and Implementation

The results of this systematic review provide a concrete basis for implementing practical strategies to mitigate voter abstention, addressing the three main clusters of factors: individual, institutional, and contextual. These recommendations integrate empirical evidence from studies analyzed across 13 countries and promote multidisciplinary approaches to strengthen democratic participation, particularly in contexts such as Portugal, where abstention reached 48.6% in the 2022 legislative elections. The proposed interventions are based on cross-cutting patterns emerging from the studies analyzed, which highlight common barriers to electoral abstention, such as socioeconomic inequalities and mobility limitations observed in diverse contexts, including social support programs and urban inclusion initiatives in Brazil and Spain. The following recommendations are not exclusive to the countries used as examples (e.g., Portugal or Chile). Still, they are adaptable internationally, with contextual adjustments to maximize applicability in developing and/or consolidated democracies.

4.1.1. Interventions for Individual and Educational Factors

A key priority is to strengthen civic and political education in schools and universities by integrating compulsory modules on electoral behavior starting in secondary school (10th, 11th, and 12th grades), including practical activities such as mock elections and debates to address gaps in political literacy [55]. This approach combats youth disengagement and lack of knowledge, extending to elementary education to foster early political socialization and the intrinsic value of democratic participation [55]. Institutional trust can be enhanced by involving social action associations and other actors, such as health centers targeting vulnerable groups (e.g., smokers), by linking psychological well-being to the relevance of voting for the promotion of public health programs, and by aligning with [18] on smoking and social distrust. Such interventions, evaluated by pre- and post-implementation surveys, could measure increases in the propensity to vote among uncommitted youth and adults.

4.1.2. Reforms for Institutional Factors

Regarding institutional factors, such as electoral reforms, the adoption of technologies, such as electronic voting, can be adapted to European contexts through pilot tests in municipalities with high abstention rates, thereby eliminating logistical barriers such as transportation costs and bureaucracy. A detailed implementation pathway includes creating a national fund for electoral mobilization, combined with digital education for specific groups (e.g., individuals with reduced mobility, the elderly, and rural populations), to facilitate equitable access. Furthermore, the decoupling of legislative and presidential elections, suggested by [48] in the French context, could be tried in Portugal through legislation separating electoral calendars, supported by mobilization campaigns via SMS and government applications to mitigate the “electoral fatigue” identified by [53]. Key solutions include secure, transparent electronic voting systems inspired by the Estonian model; flexible options such as postal voting or extending the voting period to weekends (two or three days); and modernizing party communication through social media to attract younger generations.

4.1.3. Policies for Contextual Factors

As for contextual factors, such as economic inequalities and urbanization, integrated social inclusion policies should be prioritized to mitigate disparities that exacerbate abstention. In practical terms, the Portuguese government could expand the Social Integration Income to incorporate electoral incentives, such as transportation vouchers on election day in urban areas with high abstention rates, based on [24] in the Spanish context, with evaluation through longitudinal studies that measure correlations between reduced inequalities and increased turnout, aiming at an increase in participation among lower classes. These measures, monitored by indicators such as the Government Quality Index, would promote more equitable representation and reduce socioeconomic asymmetries in participation.

4.1.4. Multidisciplinary Collaboration and Evaluation

These strategies require collaboration between academics, governments, non-governmental organizations, and health institutions, with success metrics such as the Government Quality Index to track improvements in trust and participation. Continuous evaluation, through mixed panels and impact studies, would ensure the adaptability of interventions to local contexts, contributing to a more inclusive democracy.

4.2. Limitations and Prospects for Further Study

This systematic review is based on 23 studies selected from an initial pool of 60, which may seem limited for a global phenomenon such as electoral abstention. However, reviews in political science or social psychology often synthesize similar samples to achieve thematic saturation, especially when prioritizing high-quality empirical quantitative studies (see [54,56,57]). Nevertheless, we recognize limitations in generalization due to geographical concentration (4 studies from the US and four from France) and a linguistic bias (15 studies in English), which may underrepresent dynamics in non-Western or non-English-speaking contexts. However, we must emphasize that the “language of science” is English. The fact that 15 studies were written in English also stems from the condition that researchers publish in the most universal language possible to showcase their work. Cultural or institutional factors in emerging democracies, such as Latin America and Asia, may differ, affecting the global applicability of findings on institutional trust and electoral reforms. Future work should expand the range of research languages and include other regional databases to mitigate these biases and strengthen insights into social adaptations across diverse contexts.

Interestingly, electoral abstention has not been studied as volitional behavior so far. Electoral abstention can be considered a volitional behavior because many individuals deliberately choose not to vote based on their personal goals, beliefs, or expectations of the outcome. Using the model of goal-directed behavior (MGB; [58,59]) to study electoral abstention would be especially interesting because it would allow researchers to capture the complexity of voters’ motivations, intentions, and the interplay between emotional, cognitive, and habitual factors that shape abstention decisions. Instead of viewing abstention as a mere failure to vote, the MGB can frame it as a planned, intentional behavior influenced by personal goals, expected emotional outcomes, and perceived control, thereby revealing more nuanced patterns of non-voting and informing targeted interventions. Moreover, the MGB could capture the motivational dynamics underlying electoral abstention. Indeed, the MGB integrates attitudes, social norms, perceived behavioral control, and both desires and anticipated emotions to explain intention formation. Applying it to electoral abstention would highlight not just rational calculations but also emotional and social influences that push individuals to intentionally choose not to vote.

5. Conclusions

The present systematic review aimed to determine the key drivers of voters’ nonparticipation. Findings underscore that electoral abstention cannot be attributed to a single factor, but instead emerges from the interplay of different kinds of drivers, such as individual behaviors, institutional dynamics, and broader societal contexts. Intervention that targets only one type of driver will tend to produce limited or short-term effects. Moreover, there is a need to develop a behavioral decision-making process underlying electoral abstention and to identify its associated social psychological factors. Such a socio-psychological model should aim to explain and predict electoral abstention behavior. Globally, findings indicate that future interventions should combine multiple types of factors rather than being restricted to electoral administration alone.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.A. and J.-C.G.; methodology, N.A. and J.-C.G.; software, N.A.; validation, N.A. and J.-C.G.; formal analysis, N.A. and J.-C.G.; investigation, N.A. and J.-C.G.; resources, N.A. and J.-C.G.; data curation, N.A. and J.-C.G.; writing—original draft preparation, N.A. and J.-C.G.; writing—review and editing, N.A. and J.-C.G.; visualization, N.A. and J.-C.G.; supervision, J.-C.G.; project administration, N.A. and J.-C.G.; funding acquisition, J.-C.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by national funds through FCT—Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia—as part the project CUIP—Refª UID/06317/2023.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable. This study is a Systematic Review. The study was conducted accordance with protocol registered in PROSPERO (ID: CRD42023434003) and is publicly available online.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable. This study is a Systematic Review; therefore, informed consent was not required.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ASC | Academic Search Complete |

| COVID-19 | Coronavirus Disease 2019 |

| CUIP | University Research Center in Psychology |

| ESS | European Social Survey |

| ML | MedLine |

| PBSC | Psychology and Behavioral Sciences Collection |

| PINF | PsycINF |

| SEM | Structural Equation Model |

| USA | United States of America |

| WofS | Web of Science |

Appendix A

Table A1.

Detailed Characteristics of Included Studies.

Table A1.

Detailed Characteristics of Included Studies.

| Authors, Year | Title | Main Objective | Conclusions | Sample Size | Writing Language | Country | Qual. Ass | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 [18] | Zhou et al., 2021 | A cross-sectional national survey to explore the relationship between smoking and political abstention: Evidence of social mistrust as a mediator | To investigate the relationship between smoking and voter registration/voting, using the variable “trust” as a mediator, in the context of the 2012 presidential elections in the United States of America. | Smokers are less likely to register to vote; they are also less likely to engage in voting behavior. Low social trust partly explains this negative association. | n = 9757 | English | USA | 80% |

| 2 [8] | Perea & Cabral, 2003 | Individual characteristics, institutional incentives and electoral abstention in Western Europe. | To analyze the effect of four institutional variables: compulsory voting, voting facilities, levels of electoral representation, and the structure of the ballot paper on abstention rates. | Incentives do not necessarily produce a significant change in abstention rates; more favored voters are more sensitive than less favored voters to the context in general and to the presence of compulsory voting and the characteristics of the electoral system in particular. The effect of mandatory voting is more substantial among privileged voters, and the impact of this variable on the likelihood of abstention is greater among disadvantaged voters, simply because they vote less, leaving more “room” for them to increase their participation. | Various: for Portugal n = 858 | Portuguese | Various | 80% |

| 3 [21] | Ramírez, 2018 | Citizen political culture and electoral abstention in the border town of Tijuana | To identify whether electoral abstention in Tijuana has any particularities due to its border location and in relation to the length of residence of citizens, as well as the characteristics of its political culture. | Political culture and electoral attitudes clearly reveal nuances among native and immigrant voters based on how long they have lived in Tijuana. The main characteristics of the political culture of abstentionists are: (1) Abstentionists have an idea of voting as a form of expression and evaluation of the functioning of the political system; (2) Native abstentionists have an idea of democracy in more instrumental and utilitarian terms; (3) Immigrant voters who have lived in Tijuana for between one and five years are on the ideological right and participate in elections or are itinerant abstentionists; (4) There is a significant positive association between the variable “distrust in institutions” and abstention; (5) There is a positive association between the evaluation of government performance, the representativeness of political parties and abstention. | n = 300 | Spanish | Mexico | 80% |

| 4 [23] | Soft, 2010 | Does Economic Inequality Depress Electoral Participation? Testing the Schattschneider Hypothesis | To test Schattschneider’s premise: the high abstention rates and significant differences between the electoral participation rates of the richest and poorest citizens found in the United States are caused by high levels of economic inequality. | Citizens of states with greater economic inequality are less likely to vote (which lends empirical support to Schattschneider’s theory). The high abstention and significant differences in electoral participation rates between the richest and poorest citizens in the United States of America are caused by high levels of economic inequality. | 144 elections in the USA | English | USA | 80% |

| 5 [14] | Sola-Morales & Hernández-Santaolalla, | Voter Turnout and New Forms of Political Participation of Young People: A Comparative Analysis between Chile and Spain | To explore the relationship between electoral participation and new forms of participation among young Chileans and Spaniards, as well as their perception of politics and the forms of participation that seem most relevant to them. | While electoral participation is declining in Chile and Spain, other unconventional political activities—both offline and online—are on the rise. University students in Chile and Spain are disappointed with their countries’ democratic systems. While the majority of Chilean students said they did not vote. They were dissatisfied with the system and the political parties, because they didn’t think it would change anything; in Spain, a high percentage said they didn’t take part in the elections for reasons beyond their control or simply because they didn’t have a clear idea of who to vote for. | Two countries: total sample n = 928 university students. | English | Chile + Spain | 60% |

| 6 [25] | Noble, 2016 | Abstention and invalid voting in Mexico’s federal elections, 1991–2015 | To understand whether abstention and invalid votes can also be analyzed as a component of electoral participation (and not just seen as behaviors that undermine democracy). | Abstentionism and the null vote are ineffective forms of electoral participation, although they both serve as a tool of punishment. The author suggests that the new electoral reform should dismantle the electoral system designed by authoritarianism: incorporate the null vote into the distribution of public resources, reformulate polling stations, and eliminate electoral credentials. | 300 electoral districts—9 elections—from 1991 to 2015 | Spanish | Mexico | 80% |

| 7 [49] | Gonzalez & Cox, 2022 | Fewer but Younger: Changes in Turnout After Voluntary Voting and Automatic Registration in Chile | In 2012, Chile switched from voluntary and permanent registration to compulsory voting with automatic registration. To study how electoral rules influence voter turnout by analyzing variations in turnout in presidential elections before and after this reform. | Automatic registration and voluntary voting brought 7.1 per cent of the eligible, unregistered population to the polls; voluntary voting turned away 12 per cent of those previously registered. The explicit purposes of this reform were to increase participation and reduce age bias in voting. We estimate a reduction in turnout of almost 5% of the eligible population and a 39% reduction in voter age bias. The reform also reduced the age bias in voters and brought more women than men to the polls, while at the same time causing more men than women to stop voting. | 2012 National Census | English | Chile | 80% |

| 8 [50] | Coelho et al., 2023 | Fiscal impacts of electoral abstention: a study on the electorate biometric update in Brazil municipalities | The biometric updating of the Brazilian electorate offers an innovative opportunity to examine exogenous variations in abstention rates, enabling verification of their impact on public policies, especially local public spending. | Biometric updating of the electorate decreased abstention rates in Brazil’s local elections, thereby altering the composition of local public spending on education. The results indicated that, after the biometric update, the electorate decreased abstention rates in the 2012 elections by half compared to the 2008 elections. In addition to the increase in voter turnout, it also led to changes in local fiscal policy, with increased spending on education, an area in which the provision of public services is of great importance in Brazil. There is greater electoral participation among more educated voters than among less educated voters. | 4000 Brazilian municipalities. | English | Brazil | 80% |

| 9 [48] | Fauvelle-Aymar et al., 2010 | French Electoral Reform and the Abstention Rate | How the reforms influence the electoral behavior of the masses, i.e., voter turnout. | The reforms surrounding the 1962, 1981, 1988, and 2002 elections each systematically increased abstention in legislative contests. This low turnout can be seen as a reasonable response by voters to the “presidentialisation” of these National Assembly elections in France. To the extent that future legislative elections are de-linked from the presidential ones, voter turnout is expected to increase. The decline in socio-economic conditions is not the cause of the decline in political participation in France, nor is the loss of voter ideology, a drop in political interest, or voting fatigue (more sociological explanations); on the contrary, it seems to be a rational response by the electorate to the reduced relevance of a legislative vote. For many, the costs of voting no longer exceed the benefits (since the benefits are less than they were). This suggests that citizens are not experiencing a democratic “crisis” or “malaise”. Voter turnout in legislative elections would return to previous levels if the contests were decoupled from the presidential ones. This means that the legislative elections may no longer take place after the presidential ones and instead be placed on the electoral calendar well before the presidential contests. | n = 102 elections | English | France | 80% |

| 10 [24] | Trujillo et al., 2015 | Type of habitat and behaviour electoral: the contextual effects on differential abstention in Andalusia (2011–2012) | This article analyses differential abstention from a contextual perspective, seeking to identify the extent to which local characteristics can influence their inhabitants’ electoral decisions. | The results show that both the structural characteristics—population size and territorial articulation—and the socio-economic composition of municipalities contribute to understanding the complexity of the electoral decision, so that differential abstention increases with the degree of urbanization. | Andalusian abstention rate data 2011 and 2012 | Spain | Spain | 80% |

| 11 [26] | Facchini & Jaeck, 2019 | Ideology and rationality of non-voting | What is the theoretical impact of the erosion of party ties on voter abstention? | When the left-right political divide becomes less visible, the costs of understanding political debates increase, and voter turnout rises. This interpretation of abstention has three implications: (1) it shows that among the multiple reasons responsible for the “democratic crisis” in France, the weakening of the traditional notion of left and right is significant; (2) it highlights that voters’ level of education and the Downsian theory of program convergence affect electoral behavior and political entrepreneurship; (3) it explains that the relationship between abstention and the economic crisis is non-linear. | 18 elections | English | France | 60% |

| 12 [11] | Kelleher et al., 2001 | Indicators of deprivation, voting patterns, and health status at the area level in the Republic of Ireland | To determine the relationship between mortality patterns, indicators of deprivation, general lifestyle, and social attitudes towards abstention in the Republic of Ireland (a relationship previously demonstrated between voting patterns and mortality in the United Kingdom). | There is a significant positive relationship between voting left-wing and dissatisfaction with health (r = 0.51, p < 0.02) and smoking rates (r = 0.47, p = 0.03). Smoking patterns are also positively associated with abstention rates (r = 0.526, p = 0.12). The relationship between left-wing voting patterns and indicators of deprivation and lifestyle suggests that party voting patterns and affiliations can be a useful indicator of vertical social capital. However, its variability across countries suggests that the interrelationships between socio-cultural and economic factors and their consequent influence on health status are not straightforward. | 1,806,932 votes in the 1997 national elections (electoral participation of 65.92%) | English | Ireland | 80% |

| 13 [10] | Deschamps et al., 2004 | Engaging communication at the service of reducing electoral Abstention: an application in the university environment | To check the impact of a speech condemning abstention from voting, as well as publicly declaring whether or not they intend to vote, on actual voting behavior. | Significantly more students in the two groups that conducted the preparatory activities participated in the vote than those in the group that received only an anti-abstention speech. The results are encouraging and suggest the importance of not neglecting commitment theory when seeking behavioral effects. | n = 54 (3 groups) | French | France | 60% |

| 14 [46] | Adam-Troian et al., 2020 | Pathogen Threat Increases Electoral Success for Conservatives Parties: Results from a Natural Experiment with COVID-19 in France | The impact of COVID-19 on the results of an election: the 2020 French local elections. | The perceived threat of COVID-19 (pandemic volume indices), but not the actual threat (prevalence rates), before the election is positively associated with an increase in Conservative votes. These results highlight the relevance of evolutionary theory for understanding real life and political behavior and indicate that the current COVID-19 pandemic may have a substantial impact on electoral outcomes. | n = 96 | English | France | 80% |

| 15 [27] | Langenkamp & Bienstman, 2022 | Populism and Layers of Social Belonging: Support of Populist Parties in Europe | To investigate how the different aspects of social belonging, i.e., quality, quantity, and perception of one’s own social relations, relate to electoral abstention and populist voting on the left and right. | The results reveal that all measures of social belonging encourage turnout but exert inconsistent influence on populist voting, depending on the party’s ideological inclination. While social belonging plays a secondary role for left-wing populist support, strong social belonging reduces the likelihood of supporting right-wing populist parties. Events such as decreasing family size, declining participation in social organizations, the erosion of social networks, and widespread loneliness have led experts to warn of an emerging crisis of social belonging. While the consequences for health and well-being are well established, the findings suggest that these developments are also related to voter turnout and support for populist parties. Membership of formal groups plays a special role in this dynamic, as it appears to mobilize voters and reduce support for populist parties regardless of the underlying ideology. Perceived social marginalization, i.e., a lack of strong attachment to norms and social engagement, promotes political alienation and support for radical parties. | European Social Survey (ESS) 2012 to 2018. | English | Europe | 60% |

| 16 [28] | Martín et al., 2017 | Voter abstention in the 2014 European Parliament elections: a structural analysis of its components | To build a structural model (SEM) that describes and explains the specific effects of the attitudinal components, related to punishment or electoral experimentation, resulting from the political disaffection of Spaniards towards the May 2014 European Parliament elections. | The results of the research suggest that the main factor explaining abstention is a profound change in attitude, marked by the context of political disaffection. Abstention appears as a punitive element or as a manifestation of discontent with the political class. Related to political culture, party affiliation appears to be one of the most important factors in shaping these more skeptical attitudes, fundamentally party identification and sympathy. Non-identity voters and non-sympathizers are more critical and more prone to electoral demobilization. | 1800 telephone interviews | Spanish | Spain | 80% |

| 17 [47] | Acevedo & Krueger, 2004 | Two Egocentric Sources of the Decision to Vote: The Voter’s Illusion and the Belief in Personal Relevance | The decision to vote in a national election requires a choice between serving a social good and satisfying one’s own interests. In this sense, seen as a co-operative response to a social dilemma, voting seems irrational because it can have no discernible effect on the electoral outcome. | The results suggest that some people do not vote because they put their own interests aside, but because they expect their own behavior to matter. Two psychological processes contribute to this belief: voter delusion (the projection of one’s own choice between voting and abstaining onto supporters of the same party or candidate) and the belief in personal relevance (the belief that one’s own vote is important regardless of one’s foresight). The rationality of these two egocentric mechanisms depends on the normative framework invoked. | 110 (study 1) + 86 (study 2) university students | English | USA | 80% |

| 18 [60] | Adams & Merrill III, 2003 | Voter Turnout and Candidate Strategies in American Elections | Are voters influenced by factors such as education, race, and partisanship that are not directly linked to the candidates’ positions in the current campaign, and are voters prepared to abstain if no candidate is sufficiently attractive (abstention by alienation)? | The results suggest that candidates seeking votes are rewarded for presenting divergent policies that reflect voters’ biases in their favor, rather than for political reasons. If two candidates contest an election, they are more likely to motivate their electorates away from the center and towards their party’s ideology. | n = 1389 | English | USA | 60% |

| 19 [22] | Kaba, 2022 | Who buys vote-buying? How, how much, and at what cost? | The article provides a detailed analysis of a vote-buying program involving subsidized groceries following historically high food price inflation. Using variation in voters’ accessibility to supermarkets that adhered to the program, the causal effect of the program on electoral behavior was estimated. | The results indicate that all types of voters respond to distributive spending according to the reciprocity rule; however, they do so through different channels and to varying degrees. Importantly, the most important channel for opposition voters is the purchase of abstentions, while incumbent supporters respond with higher turnout. Even short-lived subsidy programs that do not provide meaningful solutions to economic hardship can reduce voters’ willingness to hold incumbents accountable for these economic hardships and can be decisive in electoral contests. | n = 782 | English | Turkey | 80% |

| 20 [29] | Vecchione & Schwartz, 2012 | Why People Do Not Vote: The Role of Personal Values | The hypothesis under study is that people who do not vote attribute less importance to the values that parties endorse (real value congruence) and perceive parties as endorsers (perceived value congruence). | In both studies, value congruence explained substantial variation in voter abstention beyond the effects of sociodemographic variables. The result of this study corroborates previous findings that not voting is more common among the poor and less educated, with education affecting voting more than maturity. We also replicate the result that middle-aged adults are more likely to vote than younger or older people. In addition to the well-known effects of sociodemographic variables, personal values have a substantial influence on political participation. This fits in with a social cognitive view of personality as a self-regulating system: people are more inclined to act when they perceive that the action is likely to produce results that they consider relevant to affirming, promoting, and protecting their important values. This study breaks new ground by demonstrating this argument in the realm of voting. Regardless of their socio-demographic characteristics, people are more likely to vote if it allows them to promote and affirm their values. On the other hand, people have less reason to vote or get involved in politics if they perceive that voting in the current political context will neither advance nor affirm their values. Such conditions distance citizens from politics. Our findings suggest that one reason Italians did not vote in the 2008 national elections was that they didn’t identify with the center-left (in terms of values), on the one hand, and perceived the center-right as distant from their values, on the other. In the 2008 elections, many former left-wing voters defected because the left-wing coalition failed to demonstrate that it would serve the left’s traditional priorities of universalism and benevolence. | 1782 (study 1) and 543 (study 2) | English | Italy | 80% |

| 21 [52] | Girard & Okolikj, 2024 | Trajectories of Mental Health Problems in Childhood and Adult Voting Behaviour: Evidence from the 1970s British Cohort Study | The study’s core objective is to examine whether distinct trajectories of conduct problems from ages 5 to 16 years predict reduced voting participation in adulthood, using data from the 1970 British Cohort Study | The paper argues that this link may stem from deficits in cognitive/non-cognitive skills, reduced civic duty, poorer social capital, and lower political targeting, and highlights childhood as a critical period for addressing mental health to prevent lifelong disengagement from democratic processes. | n = 15,554 | English | British | 60% |

| 22 [51] | Artelaris et al., 2024 | Electoral abstention in a time of economic crisis in Greece | The study’s core objective is to examine geographical variations in abstention rates using cartographic visualizations based on parliamentary election data from 2009 to 2019. It addresses an overlooked aspect of electoral studies by highlighting how economic shocks influenced voter disengagement, emphasizing spatial patterns and clustering at the local administrative unit (LAU) level across 325 municipalities. This includes comparing changes in abstention across key periods: pre-crisis to early crisis (2009–May 2012), within-crisis (May 2012–January 2015), and crisis to stabilization (January 2015–2019). | Unequal Geographical Impact: All 325 municipalities experienced rises in abstention rates, but these changes were highly differentiated spatially, with economic recession and austerity measures creating an uneven “geographical imprint” that affected regions differently; Lack of Recovery: Once abstention increased in a municipality, recovery was rare; over 90% saw no reversal during the crisis era (2009–January 2015), and only about 20% regained voters during stabilization (2015–2019); Timing of Increases: Most municipalities (around 65%) faced their largest abstention spikes in the first post-crisis election (May 2012), except for Attica, where 87% saw the biggest losses during stabilization; Spatial Patterns: Positive spatial autocorrelation was evident across all sub-periods, with stronger clustering in 2009–2012 and 2015–2019; hot spots of high abstention emerged in northwest and southern regions initially, shifting to Attica and Central Macedonia later. | 325 Local Administrative Units | English | Greece | 80% |

| 23 [53] | Kostelka, 2025 | Understanding Voter Fatigue: Election Frequency & Electoral Abstention Approval | Explore the causal mechanisms behind voter fatigue, hypothesizing that high election frequency increases the social acceptability of electoral abstention, thereby contributing to declining voter turnout in democracies | Results confirm that abstention acceptability rises proportionally with election frequency, affecting all social groups equally, including politically engaged individuals and those viewing voting as a duty | n = 12,221 | English | five countries (Czechia, France, Poland, Romania, Slovakia) | 80% |

References

- Przeworski, A. Why Bother with Elections? Polity Press: Cambridge, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Milbrath, L.W. Political Participation: How and Why Do People Get Involved in Politics? Rand McNally: Chicago, IL, USA, 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Reto, L.; Nunes, F. Para um modelo do estudo de abstenção eleitoral em Portugal: Um estudo exploratório. Análise Psicológica 1995, 13, 471–486. [Google Scholar]

- Linz, J.J.; Stepan, A. Problems of Democracy’s Transition and Consolidation: Southern Europe, South America, and Post-Communist Europe; Johns Hopkins University Press: Baltimore, MD, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Cancela, J. Participação Eleitoral. In O Essencial da Política Portuguesa; Fernandes, J., Magalhães, P., Pinto, A., Eds.; Tinta da China: Lisbon, Portugal, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- PORDATA. Taxa de Abstenção nas Eleições para a Assembleia da República: Total, Residentes em Portugal e Residentes no Estrangeiro. Available online: https://www.pordata.pt/db/portugal/ambiente+de+consulta/tabela (accessed on 6 May 2023).

- Martins, L. Como Perder Uma Eleição; ZIGURATE: Lisbon, Portugal, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Perea, E.A.; Cabral, R. Características individuais, incentivos institucionais e abstenção eleitoral na Europa ocidental. Análise Soc. 2003, 38, 339–360. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards, K. From Deficit to Disenfranchisement: Reframing Youth Electoral Participation. J. Youth Stud. 2007, 10, 539–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deschamps, J.C.; Joule, R.V.; Gumy, C. La communication engageante au service de la réduction de l’abstentionnisme électoral: Une application en milieu universitaire. Rev. Eur. Psychol. Appliquée 2005, 55, 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelleher, C.; Timoney, A.; Friel, S.; McKeown, D. Indicators of deprivation, voting patterns, and health status at area level in the Republic of Ireland. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2001, 56, 36–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministerio del Interior, Espanhã. Elecciones Municipales en Espanã 1979–2011. 2014. Available online: https://www.interior.gob.es/opencms/pdf/archivos-y-documentacion/documentacion-y-publicaciones/publicaciones-descargables/elecciones-y-partidos-politicos/Elecciones_municipales_en_Espana_1979-2011_126141495.pdf (accessed on 13 May 2025).

- Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas. Barómetro de Octubre 2011. Estudio nº 2920; CIS: Madrid, Spain, 2011; Available online: https://www.cis.es (accessed on 13 May 2025).

- Sola-Morales, S.; Hernández-Santaolalla, V. Voter Turnout and New Forms of Political Participation of Young People: A Comparative Analysis Between Chile and Spain. Rev. Lat. Comun. Soc. 2017, 72, 629–648. [Google Scholar]

- Lijphart, A. Unequal Participation: Democraticy’s Unresolved Dilemma. Am. Political Sci. Rev. 1997, 91, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correa, A.; Forero, D. Incentivos al abstencionismo electoral por apatia em ciudadanos bogotanos que nunca han votado. Suma Neg. 2014, 12, 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arias, A.V.; Arroyave, E.P.; Gómez, C.C.; Aubad, G.A. Abstencionismo: ¿por qué no votan los jóvenes universitarios? Rev. Virtual Univ. Católica Norte 2010, 31, 363–387. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, S.; Li, Y.; Levinson, A.H. A cross-sectional national survey to explore the relationship between smoking and political abstention: Evidence of social mistrust as a mediator. SSM Popul. Health 2021, 15, 100856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boräng, F.; Nistotskaya, M.; Xezonakis, G. The Quality of Government Determinants of Support for Democracy. J. Public Aff. 2017, 17, e1643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magalhães, P. Cidadãos e Política: Apoio Popular e Participação. In O Essencial da Política Portuguesa; Fernandes, J., Magalhães, P., Pinto, A., Eds.; Tinta da China: Lisbon, Portugal, 2023; pp. 368–387. [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez, A. Cultura política ciudadana y abstención electoral en el municipio fronterizo de Tijuana. Estud. Front. 2018, 19, e007. [Google Scholar]

- Kaba, M. Who buys vote-buying? How, how much, and at what cost? J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 2022, 193, 98–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soft, F. Does Economic Inequality Depress Electoral Participation? Testing the Schattschneider Hypothesis. Political Behav. 2010, 32, 285–301. [Google Scholar]

- Trujillo, J.M.; Ortega, C.; MontabesJ. Tipo de hábitat y comportamento electoral: Los efectos contextuales sobre la abstención diferencial en Andalucía (2011–2012). Rev. Española Cienc. Política 2015, 37, 31–61. [Google Scholar]

- Noble, V. Abstención y voto nulo en las elecciones federales en México, 1991–2015. Rev. Mex. Cienc. Políticas Soc. 2016, 230, 75–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Facchini, F.; Jaeck, L. Ideology and the rationality of non-voting. Ration. Soc. 2019, 31, 265–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langenkamp, A.; Bienstman, S. Populism and Layers of Social Belonging: Support of Populist Parties in Europe. Political Psychol. 2022, 43, 931–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín, Á.C.; Otero, J.M.; Gulías, E.J. La abstención electoral en las elecciones al Parlamento Europeo de 2014: Análisis estructural de sus componentes. Rev. Española Investig. Sociológicas 2024, 159, 31–50. [Google Scholar]

- Caprara, G.V.; Vecchione, M.; Schwartz, S.H. Why people do not vote: The role of personal values. Eur. Psychol. 2012, 17, 266–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cancela, J.; Magalhães, P.C. As Bases Sociais dos Partidos Portugueses. In 45 Anos de Democracia em Portugal, Coordenado por Rui Branco e Tiago Fernandes; Assembleia da República: Lisboa, Portugal, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Alconchel, G. Jóvenes, ciudadanía y participación política. Seguridad y Ciudadanía. Rev. Minist. Inter. 2011, 6, 191–217. Available online: https://www.interior.gob.es/opencms/pdf/archivos-y-documentacion/documentacion-y-publicaciones/publicaciones-descargables/publicaciones-periodicas/seguridad-y-ciudadania/Seguridad_y_Ciudadania_N_6_2011_Monografico-Participacion-politica-y-electoral.pdf (accessed on 6 May 2023).

- Cancela, J.; Vicente, M. Abstenção e Participação Eleitoral em Portugal: Diagnóstico e Hipóteses de Reforma; Portugal Talks: Cascais, Portugal, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- García, F.J.; Fernández, O.A. Crisis política y juventud en España: El declive del bipartidismo electoral. Soc. Mutam. Politica 2014, 5, 107–128. [Google Scholar]

- Freire, A. Valores, Temas e Voto em Portugal, 2005 e 2006: Analisando Velhas Questões com Nova Evidência. In As Eleições Legislativas e Presidenciais 2005–2006: Campanhas e Escolhas Eleitorais num Regime Semipresidencial, Coordenado por Marina Costa Lobo e Pedro C. Magalhães; Instituto de Ciências Sociais: Lisboa, Portugal, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Viegas, J.M.; Faria, S.A. Abstenção Eleitoral em Portugal: Uma Perpectiva Comparada. Eleições e Cultura Política; Imprensa de Ciências Sociais: Lisboa, Portugal, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Baum, M.; Espírito-Santo, A. Desigualdades de Género em Portugal: A Participação Política das Mulheres. In Portugal a Votos: As Eleições Legislativas de 2002, Coordenado por: André Freire, Marina Costa Lobo e Pedro C. Magalhães; Imprensa de Ciências Sociais: Lisboa, Portugal, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Córdova, A.; Rangel, G. Addressing the Gender GAP: The Effect of Compulsory Voting on Women’s Electoral Engagement. Comp. Political Stud. 2017, 50, 264–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabral, M.V. O Exercício da Cidadania Política em Perpectiva Histótica (Portugal e Brasil). Rev. Bras. Ciências Sociais 2003, 18, 31–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, R.W.; Brand, R.A.; Dunn, W.; Spindler, K.P. How to write a systematic review. Am. J. Sports Med. 2014, 42, 2761–2768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; Prisma Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, 123–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, N.; Giger, J.-C. Electoral Abstention: A Systematic Review. PROSPERO 2023 CRD42023434003. 2023. Available online: https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?ID=CRD42023434003 (accessed on 21 June 2023).

- Tranfield, D.; Denyer, D.; Smart, P. Towards a Methodology for Developing Evidence-Informed Management Knowledge by Means of Systematic Review. Br. J. Manag. 2003, 14, 207–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frandsen, T.F.; Nielsen, M.F.; Lindhardt, C.L.; Eriksen, M.B. Using the full PICO model as a search tool for systematic reviews 456 resulted in lower recall for some PICO elements. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2020, 127, 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Q.N.; Gonzalez-Reyes, A.; Pluye, P. Improving the usefulness of a tool for appraising the quality of qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods studies, the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT). J. Eval. Clin. Pract. 2018, 24, 459–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simão, A.; dos Santos, R.; Brás, M.; Nunes, C. Determinants of Psychological Adjustment of Institutionalized Adolescents: A Systematic Review. Child Youth Care Forum 2025, 54, 1483–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adam-Troian, J.; Bonetto, E.; Varet, F.; Arciszewski, T.; Guiller, T. Pathogen Threat Increases Electoral Success for Conservative Parties: Results from a Natural Experiment with COVID-19 in France. Evol. Behav. Sci. 2022, 17, 357–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acevedo, M.; Krueger, J.I. Two Egocentric Sources of the Decision to Vote: The Voter’s Illusion and the Belief in Personal Relevance. Political Psychol. 2004, 25, 115–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fauvelle-Aymar, C.; Lewis-Beck, M.S.; Nadeau, R. French Electoral Reform and the Abstention Rate. Parliam. Aff. 2010, 63, 45–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, L.; Gonzalez, R. Fewer but Younger: Changes in Turnout After Voluntary Voting and Automatic Registration in Chile. Political Behav. 2022, 44, 1911–1932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coelho, G.G.; Hott, H.A.; Sakurai, S.N. Fiscal impacts of electoral abstention: A study on the electorate biometric update in Brazilian municipalities. Local Gov. Stud. 2023, 49, 1074–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artelaris, P.; Katsinis, A.; Tsirbas, Y. Electoral abstention in a time of economic crisis in Greece. J. Maps 2024, 20, 2383240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girard, L.C.; Okolikj, M. Trajectories of Mental Health Problems in Childhood and Adult Voting Behaviour: Evidence from the 1970s British Cohort Study. Political Behav. 2024, 46, 885–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostelka, F. Understanding Voter Fatigue: Election Frequency & Electoral Abstention Approval. Br. J. Politi-Sci. 2025, 55, e85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dacombe, R. Systematic reviews in political science: What can the approach contribute to political research? Politi-Stud. Rev. 2017, 16, 148–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, N.; Giger, J.-C. Unraveling the Heterogeneity of Electoral Abstention: Profiles, Motivations, and Paths to a More Inclusive Democracy in Portugal. Soc. Sci. 2025, 14, 601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennink, M.; Kaiser, B.N. Sample sizes for saturation in qualitative research: A systematic review of empirical tests. Soc. Sci. Med. 2022, 292, 114523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randles, R. Guidelines for writing a systematic review. Nurse Educ. Today 2023, 125, 105803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perugini, M.; Bagozzi, R.P. The Distinction between Desires and Intentions. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 2004, 34, 69–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perugini, M.; Bagozzi, R.P. The Role of Desires and Anticipated Emotions in Goal-Directed Behaviours: Broadening and Deepening the Theory of Planned Behaviour. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 2001, 40, 79–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, J.; Merrill, S., III. Voter Turnout and Candidate Strategies in American Elections. J. Politics 2003, 65, 161–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).