Abstract

The evolution of sustainability reporting has led to an increased emphasis on environmental disclosures, often at the expense of social and governance dimensions. While frameworks such as the International Sustainability Standards Board’s (ISSB) IFRS S2 standard offer important advances in climate-related transparency, they insufficiently address the broader social aspects of corporate sustainability performance. In response to this gap, this study investigates the interoperability of social disclosures across three major frameworks: ISSB S2, the European Sustainability Reporting Standards (ESRS), and the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) standards. Using a structured interoperability index, we systematically map and score the degree of thematic and structural alignment between these standards, focusing specifically on social disclosure topics. The analysis reveals moderate interoperability between ESRS and GRI social disclosures, but far lower alignment between ISSB S2 and either ESRS or GRI, confirming the ongoing underrepresentation of the social pillar within the ISSB framework. Connectivity ratios remain below 6% across all matrices, underscoring persistent fragmentation in global ESG reporting standards. These findings highlight the need for regulatory bodies and standard setters to advance harmonization efforts that equally prioritize environmental, social, and governance dimensions. By foregrounding the interoperability gaps in social disclosures, this study contributes to the academic debate on ESG convergence and informs policy discussions on developing multidimensional, stakeholder-responsive reporting architectures.

1. Introduction

In recent years, Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) reporting has evolved from a broad-spectrum framework encompassing diverse sustainability aspects to a more climate-centric focus. This evolution reflects the escalating urgency of climate change and the corresponding regulatory and investor emphasis on environmental disclosures [1]. However, this shift has inadvertently marginalized the social and governance pillars, leading to an imbalance in comprehensive sustainability reporting [2]. This thematic reorientation has been catalyzed in part by the introduction of the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD) and later, the establishment of the International Sustainability Standards Board (ISSB) by the IFRS Foundation. The ISSB’s flagship IFRS S2 standard, focusing on climate-related disclosures, underscores the prioritization of environmental risks and opportunities, aligning with the growing demand for decision-useful climate data [3]. Yet while IFRS S2 brings valuable harmonization for climate disclosure, it has been criticized for its limited attention to social and governance issues. These are often relegated to the periphery, despite their essential role in a company’s sustainability profile.

Despite extensive developments in ESG reporting, there remains a clear research gap concerning the interoperability of social disclosures. This paper addresses this gap by systematically comparing ISSB S2, ESRS, and GRI frameworks, and contributes by developing a structured interoperability index focused on the social pillar.

These observations raise the central research question: How interoperable are the social disclosure requirements of ISSB S2, ESRS, and GRI, and to what extent can a structured interoperability index provide a replicable way of assessing their alignment? The contribution of this paper lies in developing and applying such an interoperability index, which differs from existing crosswalks by combining thematic, structural, and granularity-based scoring. This allows us to quantify comparability systematically, rather than providing only descriptive correspondences.

In contrast, older frameworks such as the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) and newer instruments like the European Sustainability Reporting Standards (ESRS) have sought to maintain a more balanced structure. GRI’s standards span the 100–400 series and include extensive modules on labor practices, community impact, and human rights [4]. Meanwhile, the ESRS—developed under the EU’s Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD)—enforces a double materiality perspective that mandates companies to report both financial and impact materiality across a full suite of standards, including four specifically dedicated to social disclosures: Own Workforce (S1), Workers in the Value Chain (S2), Affected Communities (S3), and Consumers and End-Users (S4) [5]. Notably, the ESG Omnibus Simplification Package introduced by the European Commission aims to streamline ESG disclosures while maintaining transparency obligations. However, early critiques suggest that this drive for simplification could lead to the dilution or aggregation of complex disclosures—especially those related to social equity, labor conditions, and community engagement—ultimately weakening the materiality and auditability of the “S” in ESG [6]. This is particularly alarming considering findings, who emphasize that social issues, although less quantifiable than environmental ones, are equally material in sectors like manufacturing, energy, and consumer services.

This concern is validated by the ESG Omnibus Study, a global meta-review that tracked over 300 ESG-related regulatory instruments across jurisdictions. The study found that over 65% of mandatory disclosure requirements were climate-related, whereas only 18% were social in nature, highlighting a systemic underrepresentation of the S-pillar [1]. Despite growing interest in social metrics—such as diversity, equity, inclusion, and labor rights—standard setting bodies have yet to provide unified guidance on their implementation, leading to inconsistent reporting and reduced comparability [7,8].

These developments present a challenge to the original spirit of ESG, which emphasized the interdependence of environmental, social, and governance factors in corporate performance and risk management [9]. While environmental degradation often dominates public discourse, social resilience—ranging from workforce well-being to community adaptation—plays an equally pivotal role in long-term value creation. In the absence of detailed and interoperable social disclosure standards, stakeholders risk misinterpreting corporate sustainability strategies as climate strategies alone [10].

This paper responds to this growing imbalance by examining the interoperability—or lack thereof—between ISSB S2, ESRS, and GRI standards, with a particular focus on the social pillar. Using a structured pairing methodology, documented in a newly developed interoperability index, the study investigates how well these frameworks align on key social topics and where critical gaps remain. By identifying asymmetries in language, scope, and granularity, we aim to inform future efforts in standard harmonization and corporate reporting strategy.

Structure of the Study

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows:

- Literature Review: Provides an overview of academic and policy literature related to ESG reporting, highlighting differences in disclosure quality and framework interoperability.

- Methodology: Describes the interoperability pairing approach, based on standard-level mapping between ISSB S2, ESRS, and GRI social standards, using a structured index.

- Results: Presents findings on the thematic and technical alignment across the frameworks, with a focus on underrepresented or non-existent social disclosure topics in ISSB S2.

- Discussion: Interprets the results in the context of regulatory evolution, stakeholder needs, and ESG convergence, and discusses implications for global companies and policy harmonization.

- Conclusion and Recommendations: Summarizes key insights and offers short-term, low-cost enhancements to current mapping methodologies to improve the utility of the interoperability index.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Evolution and Divergence of ESG Reporting Frameworks

The development of ESG reporting frameworks over the past three decades reflects a progressive shift in corporate transparency demands. The Global Reporting Initiative (GRI), founded in 1997, was among the first to formalize sustainability disclosures beyond financial reporting. GRI’s multi-stakeholder approach emphasized broad materiality, encouraging companies to report not only on financially relevant topics but also on social and environmental impacts that stakeholders deemed significant [7,11]. Its comprehensive structure, spanning economic, environmental, and social dimensions, positioned it as the dominant voluntary standard throughout the early 2000s, with the GRI 400-series specifically targeting social issues such as labor rights, diversity, and community engagement [4]. In contrast, the more recent establishment of the International Sustainability Standards Board (ISSB) in 2021 under the IFRS Foundation marked a different philosophical turn. The ISSB’s mandate was primarily investor-focused, emphasizing financial materiality through disclosures that affect enterprise value. The release of the IFRS S1 and S2 standards codified this approach, concentrating heavily on climate-related risks and governance structures. Although the ISSB acknowledges sustainability broadly, its operationalization remains climate-centric, often relegating social and governance elements to secondary considerations [1,2].

Simultaneously, the European Union launched the European Sustainability Reporting Standards (ESRS) through the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD) initiative. The ESRS represents a deliberate convergence of financial and impact materiality perspectives, enshrining the principle of double materiality at the regulatory level [5]. Unlike ISSB, ESRS explicitly mandates companies to disclose not only financially material risks but also their societal and environmental impacts. Within the ESRS architecture, a distinct focus is maintained on social matters through dedicated standards such as ESRS S1 (Own Workforce), S2 (Workers in the Value Chain), S3 (Affected Communities), and S4 (Consumers and End-Users). This divergence in materiality concepts—financial materiality at ISSB versus double materiality at ESRS, and broader stakeholder materiality at GRI—creates significant challenges for interoperability. As Manes-Rossi, Nicolò, and Aversano [9] argue, frameworks rooted in different philosophical objectives will naturally yield misaligned disclosure architectures, complicating attempts at global standard harmonization.

2.2. Fragmentation and the Problem of Social Disclosure

While environmental disclosure has benefited from the galvanizing force of initiatives like the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD) and the EU Taxonomy, social disclosure remains comparatively fragmented. Studies by Frankel et al. [2] and Boiral [7] reveal that only a small fraction of regulatory ESG mandates globally require detailed reporting on social indicators. This imbalance is problematic, as social factors—ranging from human rights practices to workforce diversity and community relations—are increasingly recognized as critical to corporate resilience and stakeholder trust [10]. Yet despite growing recognition, standard setters have historically provided less structured and less enforceable guidance on social topics compared to environmental matters. The ISSB standards reflect this trend. Although some social dimensions are acknowledged indirectly within the risk management sections of IFRS S2, there is little dedicated guidance on topics such as labor conditions, diversity metrics, or community impact beyond what is tied directly to climate transition risk [3]. By contrast, GRI’s 400-series contains detailed protocols for social responsibility, offering granular indicators on labor practices (GRI 401), occupational health and safety (GRI 403), and indigenous rights (GRI 411), among others. ESRS attempts to bridge this gap by elevating social topics into standalone standards (ESRS S1–S4), but its integration with ISSB frameworks remains incomplete, as seen in current crosswalk mappings [5].

The literature thus portrays a dual gap: first, a coverage gap where social issues are underrepresented; second, a comparability gap where even frameworks that do address social issues do so using divergent metrics and terminologies [8].

2.3. Efforts Toward Interoperability

Recognizing these challenges, several efforts have been made to harmonize sustainability standards globally. The IFRS Foundation and the European Financial Reporting Advisory Group (EFRAG) signed a cooperation agreement in 2023, culminating in the “Interoperability Guidance” released in early 2024 [12]. This guidance outlines correspondences between IFRS S1/S2 and ESRS standards, particularly emphasizing climate-related disclosures but also laying a methodological groundwork for broader interoperability assessments. The guidance introduces the concepts of “common disclosures,” “incremental disclosures,” and “additional ESRS disclosures,” helping clarify where full, partial, or no alignment exists between frameworks. However, critics such as Christensen et al. [1] warn that without a deeper reconciliation of materiality principles, formal interoperability may only mask deeper conceptual divergences. Calabrese et al. [11] similarly caution that technical mappings alone cannot bridge philosophical differences in stakeholder orientation.

Parallel to regulatory efforts, voluntary organizations have also promoted cross-framework dialogue. The GRI has actively engaged with both the ISSB and EFRAG to advocate for the preservation of impact materiality and human rights disclosures within future global baselines. As [8] note, the credibility of ESG disclosures depends not only on technical interoperability but also on ensuring that critical issues—particularly in the social sphere—are not diluted in the pursuit of simplicity or convergence.

Beyond GRI and ESRS, other frameworks are highly relevant to this debate. The Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB) provides industry-specific disclosure requirements, while the general disclosure layer of IFRS S1 establishes a baseline for governance and risk management information that interacts with social topics. Existing cross-framework mapping initiatives, such as the IFRS–EFRAG Interoperability Guidance (2024) and GRI–ISSB dialogues, also point to growing regulatory interest in alignment. Finally, the concept of double materiality—central to ESRS—underscores the distinction between financial materiality and impact materiality, which complicates interoperability assessments and requires explicit treatment in comparative studies.

2.4. Academic Contributions on ESG Standard Convergence

A growing body of academic research addresses the systemic tensions underlying ESG standard convergence. Studies such as Aljanadi & Alazzani [10] explore how corporate disclosure practices differ across sectors even under harmonized frameworks, suggesting that standardization does not guarantee comparable or complete reporting outcomes. Boiral [7] critiques early GRI reports as simulacra—formalistic disclosures that imitate transparency without necessarily providing substantive accountability—raising questions about whether new standards like ISSB will replicate similar shortcomings. Furthermore, Ref. [13] emphasize that even when frameworks appear interoperable at the disclosure level, the underlying assumptions about risk, impact, and materiality often diverge sharply. Their research on ESG topic modeling across GRI and ESRS standards finds significant thematic inconsistencies, particularly regarding social resilience topics.

Together, these studies suggest that convergence efforts must address not only disclosure templates but also underlying conceptual frameworks if true global harmonization is to be achieved.

2.5. Positioning the Present Study

Building on this extensive literature, the present study adopts an empirical approach to evaluate the interoperability between ISSB S2, ESRS, and GRI standards, with a specific focus on social disclosure topics. By constructing a structured interoperability index and applying it to social-related standards, this research assesses not merely the existence of mappings but the depth and thematic consistency of disclosures. In doing so, it responds to the scholarly calls for greater transparency about standard alignment gaps [11] and offers practical insights into where future harmonization efforts might most urgently focus.

In particular, the study acknowledges the limitations of current interoperability initiatives that concentrate disproportionately on climate topics, aiming instead to foreground the often-overlooked social dimension of sustainability disclosure. In this regard, it contributes to a growing strand of critical ESG scholarship that emphasizes the necessity of multidimensional, stakeholder-responsive reporting frameworks in a complex and evolving global environment [2,10].

Recent contributions further underscore this need. Frazer (2025) provides a global analysis of ESG disclosure trends, highlighting ongoing fragmentation [14], while the Harvard Law School Forum (2025) compares significant sustainability-related reporting requirements [15], reinforcing the urgency of harmonization. These recent perspectives strengthen the positioning of the present study.

3. Methodology

3.1. Research Objective and Design

This study evaluates the interoperability of leading ESG social disclosure standards by systematically mapping and scoring disclosure alignment between the International Sustainability Standards Board (ISSB) S2, the European Sustainability Reporting Standards (ESRS), and the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI). The specific focus on the social pillar reflects a growing recognition in the literature of the disproportionate emphasis on environmental disclosures in global ESG policy and practice [1,2]. While substantial alignment exists for climate-related disclosures, social reporting remains fragmented, with inconsistencies in language, scope, and granularity [7,8].

The study employs a comparative mapping methodology, grounded in qualitative content analysis and informed by previous approaches to indicator alignment such as SDG–GRI mappings [11] and legal comparative CSR frameworks [9]. This research further integrates the EFRAG-ISSB Interoperability Guidance (2024) [12], which provides a formal foundation for determining common, incremental, and unique disclosure items across regulatory regimes.

3.2. Data Sources and Standard Scope

The comparison covers the following standards:

- ISSB S2: Climate-related disclosure standard under IFRS, with select coverage of social topics where they intersect with climate resilience.

- ESRS S1–S4: European social standards under the CSRD, covering Own Workforce (S1), Workers in the Value Chain (S2), Affected Communities (S3), and Consumers and End-Users (S4).

- GRI 200–400 series: Voluntary international reporting framework emphasizing economic, labor, human rights, and community impact disclosures.

Only social-related disclosures were extracted, following the materiality filter established in ESRS and GRI guidelines. Climate and governance disclosures were excluded to narrow the scope, with the exception of social-climate interfaces (e.g., worker transition risks).

3.3. Interoperability Index Design

The central tool used in this research is a custom-developed Interoperability Index, implemented in a structured Excel matrix. This tool operationalizes interoperability assessment by comparing disclosure items across frameworks and scoring their degree of alignment. It draws methodological inspiration from Calabrese et al. [11], who developed a framework to map GRI standards to UN SDGs, and from regulatory mapping matrices such as those produced by EFRAG and the IFRS Foundation.

For clarity, in this study, a Topic refers to a general sustainability theme (e.g., labor rights or community engagement); a Disclosure Requirement refers to the specific clause of a framework mandating reporting (e.g., ESRS S1.13, IFRS S2.14); and a Metric refers to the quantitative or qualitative indicator used to assess performance (e.g., percentage of workforce turnover). Matching decisions were made by assessing whether equivalence could be identified at the level of policy statement, disclosure indicator, or quantitative outcome.

Each entry in the index includes the following:

- Disclosure item references from each framework (e.g., ESRS S1.13, GRI 202-1, ISSB S2.14);

- A short description of the topic;

- Thematic alignment category (e.g., labor conditions, diversity, stakeholder engagement).

Interoperability score:

- o 2 = Full Match: Identical in topic, granularity, and metric type;

- o 1 = Partial Match: Thematically similar but different in scope or format;

- o 0 = No Match: No discernible equivalent disclosure.

This three-point scale is consistent with the gradations recommended by Refs. [8,10] to assess ESG disclosure comparability.

The connectivity ratio was calculated as the number of matched disclosure pairs divided by the total number of possible pairs, expressed as a percentage. Each disclosure level (theme, sub-theme, metric) was treated equally, and no weighting was applied in this version of the index. The scoring system therefore allows for transparent replication: for example, the ESRS–GRI matrix contained 961 possible disclosure pairings, of which 51 were matched, producing a connectivity score of 5.31%.

3.4. Pairing Procedure and Mapping Criteria

A multi-stage pairing methodology was adopted:

- Disclosure Item Extraction: Official documents were reviewed to extract social disclosure requirements from each standard, using keyword filters and taxonomy structures.

- Thematic Categorization: Disclosures were grouped into social subdomains: workforce, human rights, labor conditions, affected communities, consumer protection.

- Matching Process: Pairings were identified using three matching dimensions

- Topical Alignment: Whether the disclosure covers the same sustainability issue,

- Disclosure Format: Narrative (qualitative) or metric-based (quantitative),

- Granularity & Scope: Process vs. outcome focus, data disaggregation, stakeholder specificity.

- Expert Validation: Crosswalks were validated by domain experts using official mappings (EFRAG-GRI Cross-reference, EFRAG-ISSB guidance) and conceptual interpretation.

This process reflects techniques used in Calabrese et al. [11] and Manes-Rossi et al. [9], and is consistent with recommendations in the 2024 Interoperability Guidance, which explicitly defines structural alignment across ESRS and IFRS S1/S2 standards [12].

3.5. Analytical Tools

To visualize interoperability patterns and inform policy interpretation, we applied several analytical techniques:

- Heatmaps: Illustrate scoring intensity between frameworks for each sub-theme;

- Radar Charts: Compare theme-level disclosure coverage (e.g., GRI vs. ISSB on labor rights);

- Gap Tables: Highlight ESRS or GRI items with no corresponding ISSB disclosure, especially around stakeholder engagement and value chain labor rights.

These tools support a semi-quantitative interpretation of what is fundamentally qualitative alignment work. Their usage follows visualization best practices in sustainability reporting convergence studies [11].

3.6. Regulatory Interoperability Framework

This study benefits from formal regulatory alignment initiatives between the IFRS Foundation and EFRAG, particularly the “ESRS–ISSB Interoperability Guidance” [12]. Key methodological supports include the following:

- Shared definition of financial materiality between ESRS 1 and IFRS S1;

- Recognition of ESRS as a reference source under IFRS S1 paragraph C2(b);

- Inclusion of crosswalk tables mapping disclosures in ESRS E1 and ISSB S2, and clarifying incremental disclosures [12].

Although the guidance is climate-focused, it establishes a formal precedent and methodological template for broader cross-standard interoperability evaluations. Its acknowledgment of “incremental” and “additional” disclosures mirrors our partial match logic, while its mapping approach validates the Excel-based matrix model used herein.

This methodology is subject to limitations:

- Subjectivity: Scoring and thematic classification depend on expert judgment and interpretation.

- Scope Constraint: Non-social disclosures are excluded, even where intersectional (e.g., green jobs, energy poverty).

- Temporal Relevance: Standards evolve; mappings based on 2023/2024 versions may soon be outdated.

Nevertheless, the transparent, replicable structure adopted here enables both academic reuse and policy translation.

4. Results

It should be noted that ISSB S2 is primarily climate-focused, while ESRS and GRI encompass a broad range of social topics. This asymmetry partly explains the relatively low interoperability scores and should be considered when interpreting the results.

To assess the social interoperability of the ISSB and ESRS frameworks, this study uses the GRI 400-series as a normative reference for social disclosures. This approach allows for targeted analysis of how comprehensively these newer standards address long-standing social accountability expectations, even if their native scopes include broader environmental and governance domains. This asymmetrical lens is intentional: it reflects GRI’s role as a mature, stakeholder-oriented framework for the social dimension of ESG reporting.

4.1. ESRS–GRI Interoperability

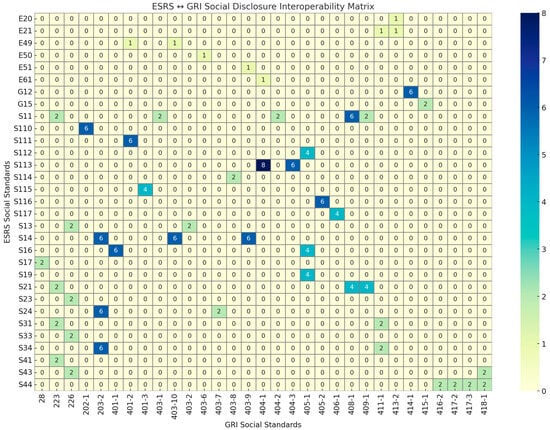

The following heatmap on Figure 1., introduces the results of interoperability between ESRS and GRI. After the figure, a detailed analysis of results will follow.

Figure 1.

ESRS and GRI Interoperability Matrix.

This heatmap presents the frequency of interoperability between the European Sustainability Reporting Standards (ESRS) and the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) across a broad spectrum of disclosure topics, not limited to the social domain. The ESRS standards include both general (e.g., ESRS 2.22, 2.26) and thematic requirements (such as environmental and social standards), while the GRI columns focus predominantly on social and economic indicators. The matrix reveals strong alignment for disclosures that address employment practices, economic inclusion, and stakeholder impacts, particularly where ESRS general disclosures (e.g., ESRS 2.x series) are mapped against GRI items like 202-1 and 203-2. The consistent presence of mapped pairs suggests that ESRS integrates foundational elements of legacy GRI guidance, especially in operational, workforce, and impact-reporting areas. However, several GRI standards show limited alignment with specific ESRS entries, highlighting areas where either disclosure format, scope, or topic orientation diverges. Overall, the matrix indicates a broad structural compatibility between the ESRS and GRI standards, though the depth and nature of alignment vary significantly by topic area. The connectivity ratio, based on the calculation method clarified in the methodology section, was 5.31% across these two standards.

4.2. ESRS–ISSB Social Disclosure Interoperability

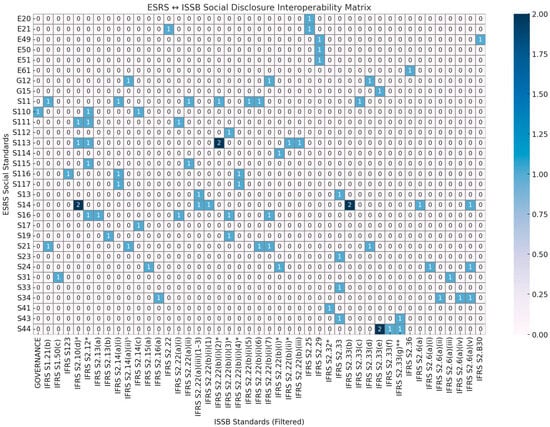

Figure 2 illustrates interoperability patterns between ESRS and ISSB disclosures, with emphasis on their thematic overlaps and divergences.

Figure 2.

ESRS and IFRS S2 Interoperability Matrix Labels and asterisk annotations are verbatim from the ESRS and ISSB Interoperability Guidance to ensure exact matching.

The second heatmap illustrates the mapping intensity between ESRS disclosures and those found in the ISSB’s IFRS S1 and S2 standards. Unlike the GRI comparison, this visualization spans a diverse set of ESRS requirements, including environmental (e.g., ESRS E1) and general disclosures (ESRS 2.x), as well as selected social elements. The filtered ISSB columns include climate and risk disclosures from IFRS S2, along with selected governance-oriented clauses from IFRS S1. While several ESRS entries demonstrate linkages to ISSB disclosures—particularly those in the ESRS 2.x and E1.x series—these are largely clustered around climate risk governance, emissions strategy, and organizational processes. The pattern underscores that interoperability is concentrated primarily in environmental and governance aspects, with less coverage of social impact areas. These findings reaffirm the position that ISSB’s current framework offers strong technical foundations for climate-related reporting but exhibits lower conceptual overlap with the broader sustainability mandates embedded within the ESRS regime. The connectivity ratio in case of these two standards was the highest amongst the three, but still considerably low, 5.59%.

4.3. GRI–ISSB Social Disclosure Interoperability

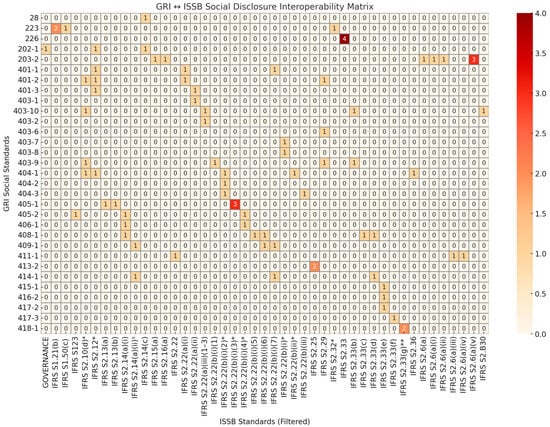

The third comparison presents GRI–ISSB interoperability, offering insights into the alignment and gaps between these frameworks.

Figure 3 displays the interoperability between GRI indicators and ISSB standards, after trimming to include only relevant ISSB disclosure categories. This matrix captures a narrow but crucial view of how the principles-based, voluntary GRI guidance aligns with the structured, investor-focused ISSB requirements. The results show sparse but strategically relevant overlaps, particularly in areas touching on economic performance and high-level stakeholder concerns. Some of the matched disclosures—such as GRI 202-1 and 203-2—intersect with general risk and climate transition considerations within ISSB’s IFRS S2. However, the majority of GRI social indicators (particularly those related to labor rights, equity, and community engagement) remain unmatched, underscoring the ISSB’s narrow thematic scope relative to the breadth of GRI’s stakeholder-oriented framework. The heatmap thus supports the interpretation of GRI as an essential complementary standard, particularly where firms must comply with regulatory ISSB frameworks but also wish to maintain high-quality stakeholder reporting in line with multi-dimensional sustainability values. The connectivity ratio mapped in Figure 3 presents the weakest connection between standards examined in this study, with a calculated connectivity ratio of 5.16%.

Figure 3.

GRI and IFRS-S2 Interoperability Matrix Labels and asterisk annotations are verbatim from the ESRS and ISSB Interoperability Guidance to ensure exact matching.

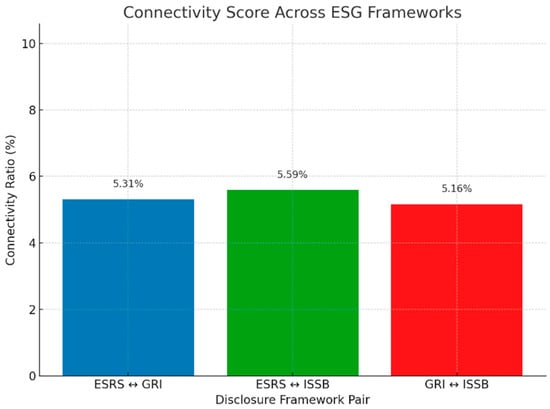

4.4. Connectivity of Disclosure Standards Across Frameworks

To quantify the interoperability between ESG disclosure frameworks, a connectivity analysis was conducted for each matrix (ESRS–GRI, ESRS–ISSB, and GRI–ISSB), presented on Figure 4. Connectivity was defined as the proportion of actual matched disclosures—those cells in the matrix with one or more linkages—to the total number of potential pairings between disclosure elements. This scoring methodology follows an established approach in sustainability convergence research, where partial or full semantic alignments between reporting standards are evaluated using matrix-based mapping tools [8,11].

Figure 4.

Connectivity Score across ESG frameworks.

The ESRS–GRI matrix yielded a total of 961 possible disclosure pairings, derived from 31 ESRS codes and 31 GRI social indicators. Of these, 51 pairs were matched, resulting in a connectivity score of 5.31%. This suggests moderate interoperability and reflects ESRS’s partial adoption of legacy GRI content, especially in employment, labor, and stakeholder disclosure topics. The result also confirms prior findings that GRI serves as a conceptual backbone for multi-stakeholder-oriented disclosure, even as ESRS introduces more detailed regulatory structuring [9].

In the case of ESRS–ISSB, the total matrix included 1395 possible disclosure connections, formed from 31 ESRS codes and 45 filtered ISSB elements. The analysis identified 78 matched entries, yielding a connectivity score of 5.59%. Although slightly higher than that of ESRS–GRI, this figure must be interpreted with caution. The ISSB’s climate-centric scope—particularly through IFRS S2—means that many of the alignments concern high-level governance or procedural elements rather than substantive social content. This pattern supports critiques in the recent literature that ISSB’s current standards underrepresent the social dimension of ESG [1,2], and that its relevance to double materiality regimes remains limited.

Finally, the GRI–ISSB matrix presented the lowest level of interoperability, with 72 matched pairs out of 1395 potential combinations. This equates to a connectivity score of 5.16%, underscoring the thematic divergence between GRI’s stakeholder-focused disclosure model and the ISSB’s investor-driven reporting objectives. As Boiral [7] notes, the richness of GRI reporting—especially in areas such as community rights, labor ethics, and equity—has historically lacked a counterpart in financial materiality frameworks, a gap that remains largely unaddressed by ISSB’s current standards.

Overall, the connectivity analysis reinforces a fundamental insight: while there is some structural convergence across the frameworks, particularly in general and climate governance domains, the social disclosure pillar remains fragmented and inconsistently mapped across global standards. These findings support recent calls in sustainability accounting literature for harmonized but multidimensional frameworks that combine stakeholder and investor perspectives [8,10].

5. Discussion

The findings of this study underscore the persistent fragmentation in global ESG disclosure frameworks, particularly in relation to the social pillar. While previous scholarship has noted the divergence in materiality perspectives between ISSB, ESRS, and GRI [1,9], this study quantifies those misalignments and reveals a more granular view of their thematic structure. The heatmaps and connectivity ratios illustrate that although GRI and ESRS share a relatively stronger conceptual foundation—with 5.31% of possible disclosure pairings showing thematic alignment—even this level of connectivity signals only modest interoperability. The ESRS–ISSB and GRI–ISSB matrices reveal even greater disjunction, with connectivity scores of 5.59% and 5.16%, respectively, confirming that the social content embedded within ISSB S2 is largely indirect, climate-adjacent, or procedural in nature.

These results have implications for both regulatory development and academic theory. From a regulatory perspective, the observed gaps challenge the sufficiency of ISSB S2 as a comprehensive standard for social disclosures. While ISSB has made commendable strides in defining global baselines for climate-related reporting, its limited engagement with the “S” in ESG raises concerns about neglecting issues such as workforce rights, community engagement, and social equity—domains that GRI and ESRS treat as core pillars. This imbalance threatens to create asymmetric reporting burdens and may foster incomplete representations of sustainability performance, especially in jurisdictions that prioritize stakeholder accountability and double materiality [12]. Furthermore, the study’s structured mapping process highlights a methodological issue in ESG convergence efforts. Existing regulatory crosswalks—such as those provided by EFRAG and the IFRS Foundation—focus predominantly on environmental alignment, leaving the architecture for social interoperability underdeveloped. The partial match categories in our index, which accounted for the majority of observed linkages, often represent vague overlaps in theme rather than clear matches in metric, scope, or format. This supports Dupuy & Garibal.’s [8] assertion that technical interoperability is not equivalent to substantive comparability.

On a theoretical level, the study reinforces calls in critical ESG literature to address the “illusory coherence” of convergence. As Boiral [7] argues, formal disclosure frameworks can simulate accountability without materially improving transparency unless they embed meaningful metrics and stakeholder engagement mechanisms. The limited presence of full matches between ISSB and the other frameworks reflects this risk: harmonization at the structural level may conceal deeper conceptual gaps in what each framework considers material, measurable, and reportable. In light of these findings, a clear need emerges for greater international coordination—not only among regulatory bodies but also among technical experts, social scientists, and civil society stakeholders—to ensure that ESG convergence efforts move beyond environmental baselining and reflect a multidimensional, stakeholder-responsive vision of sustainability reporting.

6. Conclusion and Recommendations

This study has several key limitations. First, governance disclosures were excluded, which narrows the scope of interoperability assessment. Second, the scoring process relies partly on expert judgment, introducing an element of subjectivity. Third, the mappings are based on the 2023/2024 versions of ISSB, ESRS, and GRI, which are subject to revision. These limitations should be considered when interpreting the results and suggesting directions for future research.

The current work examined the interoperability of social disclosure topics across three major ESG reporting frameworks: the International Sustainability Standards Board’s (ISSB) IFRS S2 standard, the European Sustainability Reporting Standards (ESRS), and the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI). By constructing and applying a structured interoperability index, we assessed the thematic and technical alignment between the standards, with particular emphasis on labor, equity, and community-related disclosures.

The results indicate that while some foundational convergence exists—most notably between GRI and ESRS—true interoperability remains limited. All three framework pairings produced connectivity scores below 6%, underscoring the conceptual and procedural gaps that still separate investor-oriented, climate-focused frameworks like ISSB from stakeholder-driven standards such as GRI and ESRS. These findings reinforce earlier critiques in the literature that social topics remain underdeveloped in global ESG regulatory design, and that alignment mechanisms often privilege environmental metrics while sidelining the social dimension of sustainability. Based on these insights, several recommendations can be made. First, ISSB should consider developing dedicated social standards or expanding the scope of IFRS S2 and S1 to include more robust, stand-alone social indicators. Second, future versions of regulatory crosswalks should incorporate structured mappings for social and governance topics, not just environmental disclosures. Third, policy makers and reporting organizations should be cautious in adopting streamlined frameworks without evaluating whether they adequately capture the full spectrum of materiality—particularly from the perspective of employees, communities, and other non-investor stakeholders.

Lastly, future research should continue to evaluate ESG interoperability not only across standards but also across industries, geographies, and organizational sizes. Only through such comparative, interdisciplinary approaches can the ESG reporting ecosystem advance toward true global coherence—where transparency, accountability, and sustainability are not only standardized but also equitably distributed across all dimensions of ESG.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.M. and B.L.; Methodology, B.L.; Writing—original draft, P.M.; Writing—review & editing, P.M., B.L. and Á.T.; Visualization, P.M.; Supervision, P.M. and Á.T.; Funding acquisition, P.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The research was supported by the EKÖP-24-3-I-SZE-83 University Research Fellowship Program of the Ministry for Culture and Innovation, funded by the National Research, Development and Innovation Fund.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available in [EFRAG & IFRS Foundation] at [https://www.ifrs.org/news-and-events/news/2024/05/ifrs-foundation-and-efrag-publish-interoperability-guidance/]. These data were derived from the following resources available in the public domain: [https://www.ifrs.org/news-and-events/news/2024/05/ifrs-foundation-and-efrag-publish-interoperability-guidance/ (accessed on 13 March 2025)].

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Christensen, H.B.; Hail, L.; Leuz, C. Mandatory CSR and sustainability reporting: Economic analysis and literature review. Rev. Account. Stud. 2021, 26, 1176–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frankel, R.; Kothari, S.P.; Raghunandan, A. The economics of ESG disclosure regulation. Rev. Account. Stud. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IFRS Foundation. IFRS Sustainability Disclosure Standards (IFRS S1 and S2). 2023. Available online: https://www.ifrs.org/sustainability/standards (accessed on 11 March 2025).

- Global Reporting Initiative. GRI Standards; (GRI—Standards—Global Reporting Initiative). 2023. Available online: https://www.globalreporting.org/standards (accessed on 11 March 2025).

- EFRAG. European Sustainability Reporting Standards. 2023. Available online: https://www.efrag.org (accessed on 11 March 2025).

- PwC. The ESG Omnibus: Streamlining Sustainability Reporting in the EU; (The ESG Omnibus—PwC). 2024. Available online: https://www.pwc.nl/en/topics/sustainability/esg/sustainability-regulations/the-esg-omnibus.html (accessed on 12 March 2025).

- Boiral, O. Sustainability reports as simulacra? A counter-account of A and A+ GRI reports. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2013, 26, 1036–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dupuy, P.; Garibal, J.-C. Cross-dispersion bias-adjusted ESG rankings. J. Asset Manag. 2022, 23, 631–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manes-Rossi, F.; Nicolò, G.; Aversano, N. Corporate social responsibility disclosure: A comparative analysis in different legal systems. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2018, 25, 595–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aljanadi, Y.; Alazzani, A. Sustainability reporting indicators used by oil and gas companies in GCC countries: IPIECA guidance approach. Front. Environ. Sci. 2023, 11, 1069152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calabrese, A.; Costa, R.; Levialdi, N.; Menichini, T. A methodological framework to assess how the GRI sustainability reporting standards contribute to the UN SDGs. Sustain. Dev. 2020, 28, 1523–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EFRAG & IFRS Foundation. Interoperability Guidance: Aligning IFRS Sustainability Disclosure Standards and ESRS; (IFRS Foundation and EFRAG publish interoperability guidance). 2024. Available online: https://www.ifrs.org/news-and-events/news/2024/05/ifrs-foundation-and-efrag-publish-interoperability-guidance/ (accessed on 11 March 2025).

- Molnár, P.; Suta, A.; Lukács, B.; Tóth, Á. Linking sustainability reporting and energy use through global reporting initiative standards and sustainable development goals. Clean Technol. Environ. Policy 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frazer, M. A Global Analysis of ESG Disclosure Trends. Alternative Investment Management Association. 2025. Available online: https://www.aima.org/article/a-global-analysis-of-esg-disclosure-trends.html (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Harvard Law School Forum on Corporate Governance. Comparison of Significant Sustainability-Related Reporting Requirements. 2025. Available online: https://corpgov.law.harvard.edu/2025/06/19/comparison-of-significant-sustainability-related-reporting-requirements/ (accessed on 1 September 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).