Abstract

The aim of this article is to identify the effectiveness of a teacher education program based on student perceptions. In this aim, a longitudinal research project was carried out with a sample of 14,229 students at a Spanish university who evaluated their teachers (using a Likert-type scale) after they completed a teacher training program. The CEDA teacher evaluation scale (α = 0.968; ω = 0.968) was used to assess students’ perceptions of the instructor’s role as a facilitator of learning. Complementary qualitative information was also collected, which complemented the quantitative findings. The first conclusion is the positive impact of key variables of the teacher training program: the pedagogical model, educational innovation, and evaluation strategies. Secondly, the students’ perception was slightly better in relation to the pedagogical model, followed by evaluation strategies and finally educational innovation. Thirdly, although students generally rated the teaching of technical subjects more highly than the humanities, the perception of change linked to teacher training was positive for all subjects. Finally, there was a slight difference in students’ perceptions according to the academic course (second, third, or fourth). All of the above should be considered for future teacher training programs.

1. Introduction

Post-secondary teachers, as activators of student learning, are a fundamental element in achieving significant changes in the quality of higher education [1,2,3]. Excellent instructors make a difference; they can ‘guide learning through classroom interactions, monitor learning and provide feedback, attend to affective attributes and influence student outcomes’ [3]. Our research question is this: what are the key variables of a teacher training program considered from the student’s perception of the teaching–learning process?

Higher education institutions, as both drivers and scenarios of continuous change, need to update and adapt their teaching practices to meet new challenges [4]. However, despite much effort, investment and time, the results are not always positive. What elements should be included in a teaching–learning process (and in teacher training) to have a good impact on students’ perceptions of the quality of their education? What do instructors need to learn to help all students achieve their potential? [5,6]. There is no magic formula, but there are valuable experiences that can be shared, including that of the Universidad Francisco de Vitoria in Madrid, the results of which are presented in this article. This university implemented a teacher training program called “Educate to Transform” (in Spanish “Formar para Transformar”, hereafter FpT). The course design considered the connection and coherence of the content, the use of mentoring practices, and learning in professional communities, in line with expert recommendations [7]. The FpT training program was launched from June to September 2020.

The results of the program, measured by changes in post-secondary teachers’ attitudes towards innovation and practices, were positive, and the results have been published [8]. However, the impact of the program on students’ perceptions of the teaching–learning process has not yet been measured. The aim of this article is to fill this gap and provide guidelines for the development of future teacher training programs. The variables (which are elements of the teacher training program) we have analyzed in this study are as follows: the pedagogical model, educational innovation, and evaluation strategies.

The pedagogical model of FpT focuses on the importance of community and interpersonal encounter, the search for truth, goodness, and a synthesis of knowledge [9,10], in line with the thinking of many authors [11,12,13]. The pedagogical model of the UFV [10] has three steps: awaken, discover, and decide. This model has elements in common with the experiential learning model [14]. It is based on the dynamism of human action; it seeks to awaken desire and connect the learner with meaningful questions to reflect critically and make responsible decisions.

The second variable of FpT, educational innovation, deals with the development and use of teaching methods that facilitate the creation of meaningful learning experiences. In other words, the aim is to promote self-discovery through learning, a process of interpellation of students for their personal growth and fulfillment [15]. To achieve this innovation in the classroom, the FpT training program proposed a rethinking of the objectives or end goals of university courses and the pedagogical models best suited to achieving them. The FpT program offered instructors the opportunity (through asynchronous videos and texts, as well as synchronous online meetings) to consider and internalize different teaching methodologies and innovative teaching tools and techniques, such as project-based learning, learning service, problem-based learning, gamification, cooperative learning, simulations, etc.

The third variable of the FpT program is evaluation strategies. The rethinking and renewal of evaluation strategies is based on the premise that they are an integral part of the learning process itself, rather than the end or conclusion of the process [16]. As such, evaluation strategies not only provide students with feedback on their strengths and areas for improvement but also serve as a learning experience. The aim is for students to take responsibility for their own learning, making them aware of their ‘journey’ so far and the road ahead [10].

The FpT training program was delivered to instructors in an online format. Three synchronous online meeting points were established [8]:

- Introductory seminar: to explain the role of evaluation as part of the learning process, the importance of innovation in teaching practice through different methodologies, and the potential of the new virtual learning platform (CANVAS).

- Encounter session: to share in community the discoveries and skills acquired, as well as encourage links between different models and the path taken so far.

- Closing session: to summarize in community the skills acquired and to organize their application to the courses, including the redesign of courses, teaching guides, and virtual classrooms.

The main content of the course was delivered asynchronously online, with the help of mentors and tutorials to clarify doubts and encourage individual and group learning.

The general objective of the research is to identify the effectiveness of a teacher training program based on the student’s perception of teaching practice. The specific aims of the study to achieve this overall aim were (1) to identify any statistically significant differences in students’ perceptions of the three dependent variables of the teacher training program, the pedagogical model, the educational innovation and the evaluation strategies according to the academic year (2018–2019; 2019–2020; 2020–2021; 2021–2022; 2022–2023), the academic course (second, third, and fourth), and the type of subject (technical or humanistic) and the interaction between these variables, and (2) to know students’ opinion on the changes in teaching practice in terms of the pedagogical model, educational innovation, and the renewed evaluation strategies.

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Methodological Approach

The study used a quantitative ex post facto methodology by cohort [17]. The research was carried out after the first academic semester following the implementation of the FpT training program.

In addition, qualitative data were collected to confirm and gain a deeper insight into the results of the quantitative analysis [18].

2.2. Variables

The dependent variable of the study was the students’ perception of the teaching practice of UFV professors as facilitators of their learning process. Specifically, three aspects were evaluated: the pedagogical model, educational innovation, and the renewed evaluation strategies.

The study used the following independent variables: academic year, academic course, and type of subject.

The academic year 2018–2019, before the pandemic, was used as a reference. The implementation of the FpT training program took place at the end of the academic year 2019–2020, the year of the pandemic.

The academic courses included in the study were 2nd, 3rd, and 4th. All university degrees in Spain have four academic courses. The first academic course was not included in the study because there was no previous experience to compare with the teaching prior to the FpT program.

The last independent variable was the type of subject. Subjects were divided into humanistic and technical subjects. Humanistic subjects were those related to anthropology, ethics, or theology. Technical subjects were those specific to areas of science.

2.3. Participants

The target population of the study was UFV students of the academic years 2018–2019, 2019–2020, 2020–2021, 2021–2022 and 2022–2023, and an intentional sampling method was used. For the inferential study, the sample consisted of 14,229 students. By academic year, the sample was distributed as follows: 20.6% (n = 2933) in 2018–2019, 21.6% (n = 3070) in 2019–2020, 20.1% (n = 2855) in 2020–2021, 19.7% (n = 2804) in 2021–2022 and 18% (n = 2567) in 2022–2023. The inclusion criteria selected students in the second (42%), third (31.5%), and fourth (26.5%) academic course of their degree programs. The researchers selected degree programs with at least one humanistic subject in the academic course.

For the qualitative study, the sample consisted of 34 students, all of whom were student delegates or sub-delegates. All faculties of the university were represented in both parts of the study. Delegates and sub-delegates, due to their representative function, are particularly well positioned to identify meaningful changes in the teaching–learning process.

2.4. Instruments

The CEDA “Questionnaire on the Impact of Teaching Practice on Students” was used to collect information. This questionnaire has been used by the UFV for 25 years to measure students’ perceptions. The original version was first developed and validated by García Ramos [19] and has been slightly modified over the years to adapt to new teaching-learning circumstances. The information was provided by the UFV Department of Institutional Evaluation.

For this study, we decided to use 14 items from the scale (maximum score of 84) on the role of the instructors as facilitators of learning. The items could theoretically be grouped into three variables according to whether they assessed the pedagogical model (maximum score of 36 points), educational innovation (maximum score of 24) and evaluation strategies (maximum score of 24). The internal consistency of the questionnaire (Table 1) was excellent [20].

Table 1.

Internal consistency of the scale and variables.

In order to collect qualitative information, a series of open-ended questions were designed to elicit students’ opinions on the perceived changes in teaching practice since the 2020–2021 academic year. The open questions addressed the following areas: (a) the characteristics of the courses that most promoted integral education (corresponding to the ‘pedagogical model’ variable), (b) the perceived changes in the way instructors conducted classes (corresponding to the ‘educational innovation’ variable), and (c) the perceived changes in evaluations (corresponding to the ‘evaluation strategies’ variable).

2.5. Data Collection

To conduct the study, information was collected from two sources. The first was a questionnaire on students’ perceptions of teaching practice (CEDA) for the academic years 2018–2019, 2019–2020, 2020–2021, 2021–2022, and 2022–2023. These evaluations were accessible thanks to the help of the UFV Vice-Rectorate for Quality and Organisational Change. All students signed an informed consent form before participating in the study. The second was an online questionnaire with the open-ended questions mentioned above. It was administrated at the end of the 2020–2021 academic year.

2.6. Data Analysis

First, the internal consistency of the instrument was estimated by calculating Cronbach’s Alpha and McDonald’s Omega.

For the first objective of the study, randomized two-way ANOVA tests were used, as well as one-way repeated measures ANOVA. The sample effect size was also estimated [21].

For the second aim of the study, thematic discourse analysis was used to create semantic networks [18].

Quantitative analysis of the results was carried out using IBM SPSS v.26 and R Studio v.4.0.4. The qualitative analysis was carried out using the program Atlas.Ti. v.9.1.

3. Results

In terms of the results obtained, the inferential results are presented first, followed by the qualitative results. Furthermore, within each of the sections, the results are organized according to the dependent variables—pedagogical model, educational innovation, and evaluation strategies. Furthermore, in each of the sections, the results obtained are presented according to the academic year, the type of subject, and the academic course, as well as the interaction between them.

3.1. Results on Pedagogical Model

Table 2 below shows the means and standard deviations of the “Pedagogical model” score by academic year, academic course, and subject type.

Table 2.

Mean (standard deviation) of the main effects of the “Pedagogical model”.

Regarding the main effects found, a significant main effect was observed, with a moderate effect size, and an adequate observed power of the academic year (F (2, 14183) = 75.78; p < 0.001; η = 0.021; 1 − β = 1). The effect of subject type (F (1, 14183) = 226.14; p < 0.001; η = 0.016; 1 − β = 1) on the pedagogical model variable was also significant, moderate, and adequate. On the other hand, the effect of the academic course was not significant (p = 0.055).

In the information collected after the post hoc analyses, it was observed that there were significant differences between the academic years, except when comparing years 2019–2020 and 2021–2022 and 2020–2021 and 2022–2023. In these cases, the results are similar. Moreover, it was observed that technical subjects scored significantly higher in the pedagogical model variable than humanistic subjects.

As for the interaction effects, we first observed a significant interaction effect with a weak effect size and an adequate power of academic year and course (F (4, 14183) = 6.31; p < 0.001; η = 0.004; 1 − β = 1). Comparisons between the academic year and course (Table 3) revealed that (a) in the second course, significant differences were found in all comparisons except between academic years 2018–2019 and 2019–2020, academic years 2019–2020 and 2021–2022, and academic years 2020–2021 and 2022–2023. (b) In the third course, significant differences were only found between academic year 2018–2019 and all other academic years. The remaining differences were not significant. (c) In the fourth course, all differences were significant except for the comparison of academic year 2019–2020 with academic year 2021–2022 and academic year 2020–2021 with academic year 2021–2022.

Table 3.

Mean (standard deviation) of the interaction effect between the academic year and course of the “Pedagogical model”.

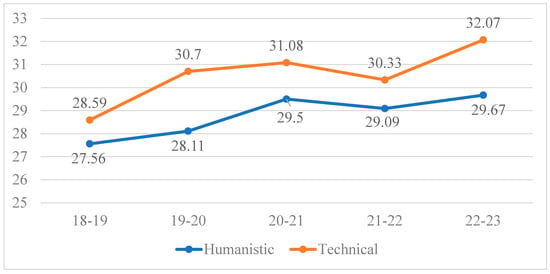

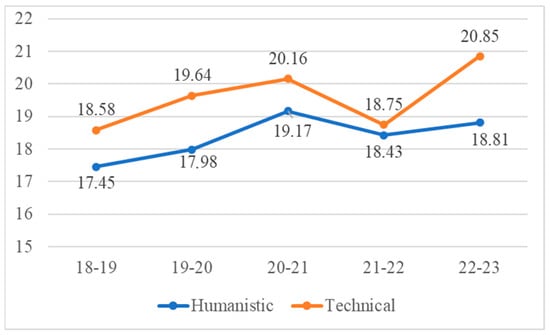

Secondly, a significant interaction effect was observed with a weak effect size and adequate power (F (2, 14182) = 9.15; p < 0.001; η= 0.003; 1 − β = 1) of academic year and subject type (Figure 1). All differences were found to be significant except for humanistic subjects when comparing years 2018–2019 and 2019–2020 and when comparing years 2020–2021 and 2022–2023 and except for technical subjects when comparing years 2019–2020 with years 2020–2021 and 2021–2022.

Figure 1.

Mean scores of the “Pedagogical model” by academic year and type of subject.

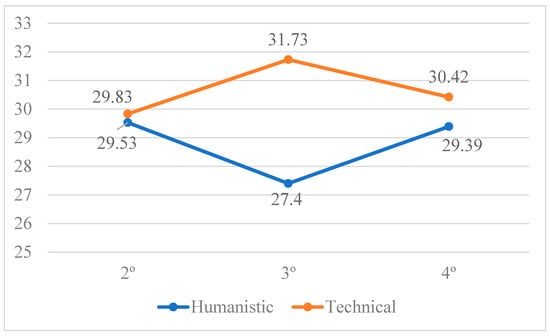

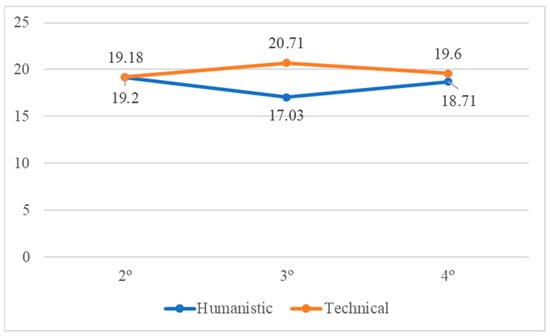

Thirdly, an interaction effect was observed between the academic course and subject type (F (2, 14183) =163.92; p < 0.001; η = 0.023; 1 − β = 1). In humanistic subjects, all pairwise comparisons were significant, except when comparing the second and fourth course. On the other hand, all pairwise comparisons were significant in technical subjects, with third-year students giving their instructors the highest scores on this variable (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Mean scores of the “Pedagogical model” by academic course and type of subject.

3.2. Results on Educational Innovation

Table 4 below shows the means and standard deviations of the “Educational Innovation” score by academic year, academic course, and subject type.

Table 4.

Mean (standard deviation) of the the main effects as concerns “Educational Innovation”.

Three significant main effects were found, with those corresponding to academic year (F (4, 14202) = 61.63; p < 0.001; η = 0.017; 1 − β = 1), academic course (F (2, 14202) = 5.830; p < 0.01; η = 0.001; 1 − β = 0.873), and subject type (F (1, 14202) = 273.202; p < 0.001; η = 0.019; 1 − β = 1). For the academic year, all comparisons were significant, except when comparing the academic year 2019–2020 with 2021–2022. Regarding the academic course, there were statistically significant differences when comparing the second and third course with the fourth course. Differences between the second and third course were not significant. Finally, higher mean scores were observed in technical subjects compared to humanistic ones.

Regarding the interaction effects, statistically significant differences were observed in the interaction effect between academic year and course (F (8, 14203) = 3.03; p < 0.01; η = 0.002; 1 − β = 0.963). Pairwise comparisons (Table 5) showed that all comparisons were significant except in the second course when comparing academic year 2018–2019 with 2019–2020 and academic year 2019–2020 with academic year 2021–2022 and 2020–2021. In addition, in the third course, the comparison of academic year 2019–2020 with 2020–2021 and 2021–2022, the comparison of 2020–2021 with 2021–2022 and 2022–2023, and the comparison of 2022–2023 with all other years except 2018–2019 were not significant.

Table 5.

Mean (standard deviation) in the interaction effect between academic year and course on “Educational Innovation”.

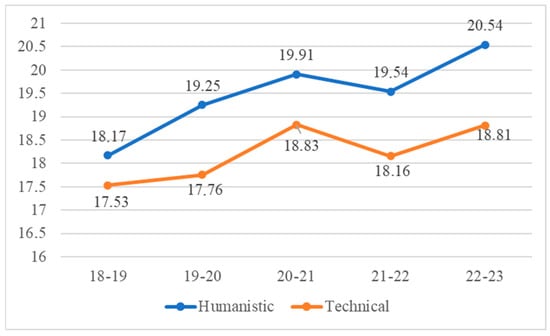

In the comparison between academic year and subject type, the effect was also significant (F (4, 14202) = 8.502; p < 0.001; η = 0.002; 1 − β = 0.999). Pairwise comparisons (Figure 3) showed that all comparisons were significant except in the humanistic subjects when comparing years 2019–2010 and 2019–2020 and years 2020–2021 and 2022–2023. In the technical subjects, the comparison between 2019–2020 and 2021–2022 was not significant.

Figure 3.

Mean scores of “Educational Innovation” by academic year and type of subject.

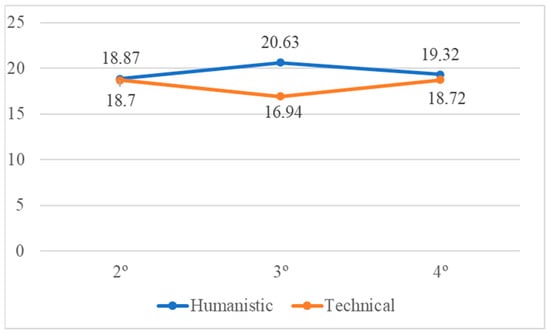

Finally, in the comparison between academic year and subject (F (2, 14202) = 222.723; p< 0.001; η = 0.030; 1 − β = 0.1). In the pairwise comparison (Figure 4), all the comparisons were significant, except for the comparison in the humanities subject when comparing the second and fourth course.

Figure 4.

Mean scores of “Educational Innovation” by academic course and type of subject.

3.3. Results on “Evaluation Strategies”

Table 6 below shows the means and standard deviations of the “Evaluation strategies” score by academic year, academic course, and subject type.

Table 6.

Mean (standard deviation) of the main effects of “Evaluation strategies”.

Three significant main effects were observed, with those corresponding to academic year (F (4, 14202) = 59.09; p < 0.001; η = 0.016; 1 − β =1), academic course (F (2, 14202) = 4.64; p < 0.05; η = 0.001; 1 − β = 0.784), and subject type (F (1, 14202) = 324,152; p < 0.001; η = 0.022; 1 − β = 1).

All the comparisons regarding academic year were significant, except when comparing the years 2019–2020 and 2021–2022 and the years 2020–2021 and 2022–2023. With respect to the academic course, significant differences were observed in all the comparisons made except when comparing the second and fourth course. Finally, it is in the technical subjects that the evaluation strategies score is most noticeable.

Regarding the interaction effects, a significant effect of year and course on “Evaluation strategies” was observed (F (1, 14202) = 5.540; p < 0.001; η = 0.003; 1 − β =1), as we can see in Table 7.

Table 7.

Mean (standard deviation) of the interaction effect between academic year and course as concerns “Evaluation Strategies”.

In the comparison between academic year and subject type, the effect was also significant (F (4, 14202) = 8.502; p < 0.001; η = 0.002; 1 − β = 0.999). Pairwise comparisons (Figure 5) showed that all comparisons were significant except for the humanities subjects when comparing years 2018–2019 and 2019–2020 and years 2020–2021 and 2021–2022 with 2022–2023, and in the case of technical subjects, when comparing years 2019–2020 and 2020–2021 and years 2020–2021 and 2021–2022.

Figure 5.

Mean scores of “Evaluation Strategies” by academic year and type of subject.

Finally, there was also a significant interaction effect between academic course and subject (F (8, 14202) =189.265; p < 0.001; η = 0.026; 1 − β = 0.999). All pairwise comparisons (Figure 6) were significant.

Figure 6.

Mean scores of “Evaluation Strategies” by academic course and type of subject.

3.4. Overall Results of the Teacher Training Program

Finally, the three variables assessed above (pedagogical model, educational innovation, and evaluation strategies) were compared to test whether the students’ perceptions were different. To perform this comparison, the variable scores were re-scaled to a 72-point scale (Table 8), as the number of items were different. The analysis showed that there were differences between the scores of the variables (F (2, 28236) =1198.376; p < 0.001; η2 = 0.078; 1 − β = 1). The pedagogical model showed the highest score, followed by evaluation strategies and (closely) educational innovation.

Table 8.

Original and scaled means (standard deviation) of the variables.

3.5. Qualitative Results

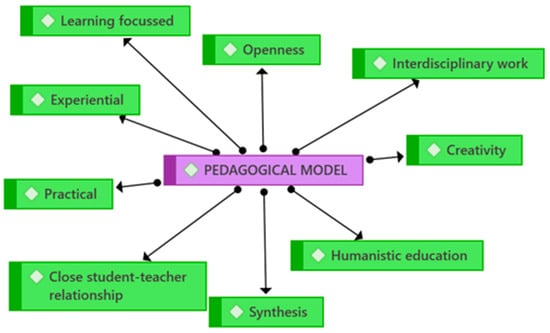

Regarding the “Pedagogical model”, students perceived that their instructors made an effort to improve their learning experience. In general, the students identified certain actions or practices of the instructors that reflected the pedagogical model of the UFV, which is oriented towards integral education (“To educate the student as a person, apart from technical knowledge”). This type of learning is understood by the students as experiential, practical, and human learning, aimed at stimulating their creativity and developing their capacity for synthesis (“They have space for debate and sharing; opinions are asked for and shared among everyone”). Furthermore, the qualitative results show the commitment of the instructors to build a closer relationship with the students, facilitating the work across the different courses (“Thanks to the technology that has been included, there is a faster relationship between the teacher and the student (even for tutorials via video calls), and, on the other hand, it promotes learning (when you have not been able to attend class for various reasons, the recordings allow you to replay the class over and over until you understand it, which is appreciated in terms of learning time). There are students who find the class challenging, and these recordings help them decide their own learning pace”). Figure 7 displays a semantic network of the discourse described above.

Figure 7.

Semantic network for the pedagogical model.

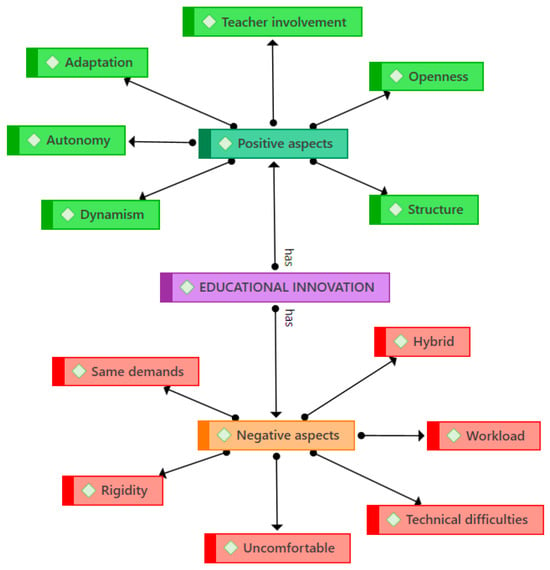

For “Educational innovation”, the students identified both positive and negative aspects of teaching practice of their instructors. The positive aspects included the involvement of instructors, and their capacity to adapt, their engagement and openness, and the good structure of the course content (“They are 100% engaged with the class both inside and outside the classroom.” The teachers were very attentive to any issues that each student might have, and they were always willing to help). Students also mentioned the dynamism in the classroom and the way instructors promoted students’ autonomy in the learning process (“More practical assignments. Presentations by company employees. Practical exams on applied theory. Volunteer/additional work beyond classroom readings.” They are dynamic, practical, and long enough to maintain the student’s attention). On the negative side, students noted that on many occasions instructors were rigid or inflexible and were sometimes unable to resolve difficulties in the use of classroom technology, resulting in lost class time (“He/she did not know how to use the technological tools of the classroom, and therefore, valuable time of the course would be lost”). In addition, students perceived that their instructors were uncomfortable with the hybrid format, indicating that this modality was not particularly conducive to their learning and that they felt overloaded with work (“The vast majority of teachers, if not all, felt very uncomfortable with hybrid or online classes”). Figure 8 presents a semantic network of the issues noted above for the variable “Educational innovation”.

Figure 8.

Semantic network for educational Innovation.

Finally, regarding the variable “Evaluation Strategies”, students indicated, as with “Educational Innovation”, both positive aspects and areas for improvement. Among the positive aspects, students noted that evaluations were practical, flexible, and technologically accessible online (“There is flexibility on the part of the teachers in that the exams are not all theoretical, but have adopted a more practical profile, as is the case with the projects; “The tests available after some topics are a very useful tool for studying.”). They also considered evaluations as a learning tool and the feedback they received from their instructors as an important part of their learning process (“When the teachers write comments explaining what I got wrong and how to improve for next time.”). In terms of negative aspects or areas for improvement, students commented that the adaptation of classroom content to the online environment (e.g., use of simulators) was not always optimal and that instructors’ demands were often excessive, leading to an overload of work and exams. Students also identified technical problems or bugs that reduced the effectiveness of the evaluation process (“When technological failures occur, many teachers do not take them into account and there is no such flexibility”). In some cases, students did not see any changes in the way evaluation was carried out, or they lacked effective feedback from their instructors (“In aspects not related to technology or the virtual classroom, I have not noticed any changes”)

Figure 9 shows a semantic network for ‘renewed evaluation strategies’ based on the above information.

Figure 9.

Semantic network for evaluation strategies.

4. Discussion and Conclusions

The aim of this research project was to identify the effectiveness of a teacher education program, based on student perceptions. A positive impact on all three variables (pedagogical model, educational innovation, and evaluation strategies) is observed in the three academic years after carrying out the program. It can be concluded that the teacher training program has a positive efficacy on students, so it is plausible to consider an adequate pedagogical model, a proposal for educational innovation and a renewal of evaluation strategies as key variables.

It is noticeable that the positive impact is greatest in the year immediately following the intervention, and it then decreases and increases again in the third year to a level slightly higher than in the year following the intervention. Overall, we can say that the program had a positive and stable effect over time. This finding confirms the importance of systematic teacher training programs for university professors to develop the pedagogical, methodological, assessment, and technological competences necessary to implement learning-centered educational models [22].

Secondly, the impact is similar for all three variables: pedagogical model, innovation, and evaluation. The pattern is similar in all academic years, with the pedagogical model being the best perceived variable, followed by evaluation and finally innovation.

Thirdly, although the training program has a positive impact and a similar trend on both technical and humanistic subjects, the difference in students’ perception in favor of teaching technical subjects is significant. These results are similar to those found in other universities [23,24]. One explanation for the students’ perception could be the difficulty of teaching humanistic subjects and the possible consideration that these subjects are less relevant to the daily realities of students’ lives. Similar results were found in other courses, such as statistics or data analysis. This is not to say that these subjects are less important in building character and developing critical thinking in students. It would be helpful to conduct further research into the causes and possible solutions to this poorer perception of teaching performance in humanistic subjects.

In addition, the results show a clear difference in the evaluation of technical and humanistic courses depending on the year of the students. Humanistic subjects were scored significantly lower by third-course students than by second- and fourth-course students. On the other hand, technical courses scored higher among students of the third course. This may be explained by the organization of the curricula. In the second and fourth courses, students are either establishing themselves in the university environment, taking mainly introductory courses in their disciplines, or oriented towards their future employment, finishing their studies and interested in their professionalization and the final stages of their studies (internships and/or final projects). These results are similar to those of the study by González [25], which found that first-year students are ‘disconcerted’ or ‘disoriented’ within the university environment, while final-year students experience similar feelings, but in the face of future employment prospects.

Finally, the effect is similar in all variables, but there is a slight difference in students’ perceptions depending on the course, which suggests that different strategies should be offered depending on the course; the pupils who perceive their instructors best are those in the fourth course (e.g., at the end of their studies). In any case, the differences are small. Differentiated teaching strategies should be designed according to the course.

The qualitative results are consistent and enrich the above explanation. Regarding the pedagogical model, students perceive and value positively the university’s pedagogical model based on interpersonal encounters, open reasoning, and experiential learning [26,27,28].

In addition, students emphasized the importance of establishing close relationships between students and instructors, as well as interdisciplinary work. Again, as above, students emphasized the importance of the student-teacher relationship and the importance of mentoring. Both are fundamental elements of the educational project pursued by the UFV. Interdisciplinary work can refer to the integration of knowledge, establishing a dialogue between the humanities, philosophy, and theology and specific fields of science. It is certainly the essential role of any university to seek the integration or synthesis of knowledge [29,30,31].

In terms of educational innovation, one of the aspects most valued by students was the involvement and engagement of instructors in adapting to the new way of teaching. The importance of instructors’ adaptation and involvement, as well as the greater autonomy of students as protagonists of their learning process, has been studied by several authors [32,33]. However, adaptation is a process. Instructors need time to consolidate new methodologies appropriate to a hybrid environment and to adjust content and workload according to new teaching practices [34]. This last aspect also has implications for evaluation strategies, especially for practical evaluation modalities [35]. Nevertheless, new forms of evaluation are seen as an opportunity for learning, especially when instructors provide meaningful feedback [36].

This work has a number of limitations that should be noted. Firstly, the research was carried out with students from a single university, which prevents the external validity of the study from being established. Future research should include students from other universities in its sample to provide a more complete picture of how higher education institutions are adapting their educational models and teaching practices to the needs of the new educational scenario. Another limitation identified may be related to multiple variables that affect the interpretation of the results, such as the teaching style, the years of teaching practice, and the variables connected to the students’ own learning process, including their commitment and motivation.

Despite its limitations, this study can be considered a useful exploratory study. The results of the teaching practice evaluation questionnaires provide very valuable information for faculty to improve the teaching–learning process. Instructors need to become interpreters of evidence and know the effectiveness and impact of their teaching; ‘when educators focus on defining, evaluating and understanding their impact, this leads to maximizing student learning and achievement’ [2]. In any case, it seems clear that it is important to design and implement appropriate continuing education programs for university teachers, as research suggests [37].

Future research could adopt an experimental design that includes a control group (students taught by newly hired instructors who have not yet participated in the program). This approach could provide stronger evidence of the program’s efficacy. Moreover, subsequent studies may expand the analysis by examining potential differences in students’ perceptions across subject areas and academic years. This could allow for the development of more tailored and effective training strategies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.L.G. and B.O.-D.; Methodology, B.O.-D. and J.R.B.; Software, B.O.-D. and J.R.B., J.L.G., B.O.-D. and J.R.B.; Formal analysis, B.O.-D. and J.R.B.; Investigation, J.L.G. and B.O.-D.; Data curation, J.R.B.; Writing—original draft, J.L.G. and B.O.-D.; Supervision, J.L.G.; Project administration, J.L.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable. The research uses the data that the Francisco de Vitoria University has obtained from students in the evaluation of teaching practice, with the free consent of the students. It does not involve any ethical conflict.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. The data was collected anonymously as part of the university’s teacher evaluation process.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Gonzalez-Sanmamed, M.; Estevez, I.; Souto, A.; Munoz, P.C. Ecologías digitales de aprendizaje y desarrollo profesional del docente universitario. Comun. Rev. Cient. Comun. Educ. 2020, 28, 9–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hattie, J. The applicability of visible learning to higher education. Scholarsh. Teach. Learn. Psychol. 2015, 1, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madinabeitia, A.; Lobato, C. ¿Puede el impacto de las estrategias de desarrollo docente de larga duración cambiar la cultura institucional y organizativa en educación superior? Educar 2015, 51, 127–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palacios-Núñez, M.; Toribio-López, A.; Deroncele-Acosta, A. Innovación educativa en el desarrollo de aprendizajes relevantes: Una revisión sistemática de literatura. Rev. Univ. Soc. 2021, 13, 134–145. [Google Scholar]

- Darling-Hammond, L.; Bransford, J. (Eds.) Preparing Teachers for a Changing World: What Teachers Should Learn and Be Able to Do; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Feiman-Nemser, S. Teacher learning: How do teachers learn to teach? In Handbook of Research on Teacher Education; Cochran-Smith, M., Feiman-Nemser, S., McIntyre, D.J., Demers, K.E., Eds.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2008; pp. 696–705. [Google Scholar]

- Darling-Hammond, L.; Hammerness, K.; Grossman, P.; Rust, F.; Shulman, L. The design of teacher education programs. In Preparing Teachers for a Changing World: What Teachers Should Learn and Be Able to Do; Darling-Hammond, L., Bransford, J., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2007; pp. 390–441. [Google Scholar]

- Martín-Sanz, N.; Vivas-Urías, M.D.; Nuere-Salgado, L.; Valle-Benítez, N.; Valbuena-Martínez, M.C. Educate to transform: An innovative experience for faculty training. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2023, 28, 1613–1635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agejas, J.A.; Antuñano, S. Universidad y Persona: Una Tradición Renovada; EUNSA: Pamplona, Spain, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Universidad Francisco de Vitoria. Formar para Transformar. El Proyecto Formativo de la Universidad Francisco de Vitoria; Editorial Universidad Francisco de Vitoria: Madrid, Spain, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Escobar, M.P.; Franco, Z.; Duque, J.A. La formación integral en la educación superior. Significado para los docentes como actores de la vida universitaria. Rev. Eleuthera 2010, 4, 69–89. [Google Scholar]

- Guerra, Y.; Mórtigo, A.M.; Berdugo Silva, N.C. Formación integral, importancia de formar pensando en todas las dimensiones del ser. Rev. Educ. Desarro. Soc. 2013, 8, 48–69. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Barrera, F. Formación integral: Compromiso de todo proceso educativo. Docencia Univ. 2009, 10, 123–135. [Google Scholar]

- Kolb, D.A. Experiential Learning: Experience as the Source of Learning and Development; FT Press: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Restrepo, B. Aprendizaje basado en problemas (ABP). Una innovación didáctica para la enseñanza universitaria. Educ. Educ. 2005, 8, 9–20. [Google Scholar]

- García Ramos, J.M. Fundamentos Pedagógicos de la Evaluación; Síntesis: Madrid, Spain, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- León, O.; Montero, I. Métodos de Investigación en Psicología y Educación. Las Tradiciones Cuantitativa y Cualitativa, 4th ed.; McGraw-Hill: Columbus, OH, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Jorrín Abellán, I.M.; Fontana Abad, M.; Rubia Avi, B. Investigar en Educación: Manual y Guía Práctica; Síntesis: Madrid, Spain, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- García Ramos, J.M. Valoración de la competencia docente del profesor universitario: Una aproximación empírica. Rev. Complut. Educ. 1997, 8, 81–108. [Google Scholar]

- Abad, F.; Olea, J.; Ponsoda, V.; García, C. Medición en Ciencia Sociales y de la Salud; Síntesis: Madrid, Spain, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- IBM. Eta Cuadrado: IBM. 2019. Available online: https://www.ibm.com/docs/en/SSLVMB_26.0.0/pdf/es/IBM_SPSS_Advanced_Statistics.pdf (accessed on 10 September 2023).

- Fernandez-March, A. Metodologías activas para la formación de competencias. Educatio Siglo XXI 2006, 24, 35–56. [Google Scholar]

- Carvajal, A.; García, J. Cómo perciben los estudiantes universitarios la enseñanza de la filosofía, según sus experiencias en la educación diversificada costarricense. Rev. Electrón. Actual. Investig. En Educ. 2004, 4, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, A. Percepciones de los estudiantes hacia la clase de Filosofía general en el campus central de la Universidad Nacional Autónoma de Honduras. Rev. Cienc. Tecnol. 2013, 12, 27–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, B. Formación integral: Un estudio de algunos logros y carencias. Ecos Acad. 2017, 3, 145–154. [Google Scholar]

- Agejas, J.A. La ruta del Encuentro. Una Propuesta de Formación Integral en la Universidad; Colecciones diálogo; Universidad Francisco de Vitoria: Madrid, Spain, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- González-Iglesias, S.; De la Calle, C. El acompañamiento educativo, una mirada amplia desde la antropología personalista. Sci. Fides 2021, 8, 181–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López Quintás, A. Inteligencia Creativa: El Descubrimiento Personal de los Valores; Biblioteca de Autores Cristianos: Madrid, Spain, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Lacalle, M. En Busca de la Unidad del Saber. Una Propuesta Para Renovar las Disciplinas Universitarias; Editorial UFV: Madrid, Spain, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez, S.; Castaño, R. Funciones de la Universidad en el siglo XXI: Humanística, básica e integral. Rev. Electrón. Interuniv. Form. Profr. 2016, 19, 191–199. [Google Scholar]

- Torres Ortiz, J.A.; Cifuentes Medina, E.; Plazas Díaz, C. El naufragio de las humanidades. Saber Cienc. Lib. 2017, 12, 196–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escribano, A. Aprendizaje cooperativo y autónomo en la enseñanza universitaria. Enseñ. Teach. Rev. Interuniv. Didáct. 1995, 13, 89–104. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez de Cabrera, L.B. El rol del docente en el aprendizaje autónomo: La perspectiva del estudiante y la relación con su rendimiento académico. Rev. Diálogos 2015, 7, 45–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, J. Future and changing roles of staff in distance education: A study to identify training and professional development needs. Distance Educ. 2018, 39, 37–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Peñalvo, F.J. Modelo de referencia para la enseñanza no presencial en universidades presenciales. Campus Virtuales 2020, 9, 41–56. [Google Scholar]

- Hattie, J.A.C.; Timperley, H. The power of feedback. Rev. Educ. Res. 2007, 77, 81–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caballero, K. La formacion del profesorado universitario y su influencia en el desarrollo de la actividad profesional. Rev. Docencia Univ. 2013, 11, 391–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).