Abstract

Population ageing has become a major global demographic shift but perhaps less noticeable in the Global South. Zimbabwe, like many African countries, is experiencing and will continue to witness an increase in older age, hence questioning its readiness to handle such change. Ageing in Zimbabwe is currently occurring in the context of increasing poverty, political unrest, changing family structures, and weakening infrastructures. Despite this, Zimbabwe is committed to promoting change and betterment for its citizens through adherence to international agendas and national development strategies. However, the first step towards the realisation of an inclusive urban environment begins with a fair representation of the various actors and social groups. This review paper is aimed at examining the representation of Zimbabwe’s older people, a subject that has rarely been the focus of critical analysis, concentrating on the political discourse in urban development programmes. A sample of 45 international and national policy documents published post-2002, was carefully selected and inspected to determine the level of presence of older people using discourse analysis. The findings reveal that in the context of the efforts made towards a Zimbabwe that is inclusive of all citizens, the idea of older persons as subjects of rights and active participants has yet to truly gain sufficient currency. There is a dominance of a one-dimensional perspective across the majority of the publications, with older people constructed as “dependent”, “vulnerable” and “passive”, overseeing vital contributions to society. A realistic and more empowering representation of this social group, showing them as active caregivers rather than passive recipients is therefore a necessity if Zimbabwe is to fulfil its vision of inclusivity.

Keywords:

ageing; inclusivity; Zimbabwe; urban environments; discourse analysis; urban policy; Africa 1. Introduction

Previous studies concerning the urban physical environment and occupants’ health have provided credible evidence and a range of interventions that can lead to better living conditions contributing to residents’ well-being. Older persons, among the various age groups, are often the most vulnerable to the influence of the urban characteristics of their living environment. As people age, they experience losses in physical capabilities and social support thus affecting their interactions with the surrounding context [1,2]. The significance of the city and the quality of the urban environment for older people’s health has been gaining recognition in recent decades, nerveless most of the current scholarly contributions tend to address issues that are associated with demographic changes and ageing in developed nations. On the contrary, research into ageing and the implications of the changing demographics in Global South countries is fairly recent. It has only been in the past 20 years that an expanding, though limited, body of literature on older people in urban Africa, has emerged covering a range of topics across diverse regions [3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12]. Part of the current interest in Africa’s ageing population was initially triggered by the increasing volume of Non-Governmental Organisation (NGO) programmes and the advocacy for the well-being of older people living in urban areas led by the World Health Organisation’s (WHO) initiatives and other foundations. Across Africa and despite the specificity of the challenges facing each nation separately, there have been some common issues that initiated the need for change and subsequently have stimulated the discourse on the visibility, the rights, and the lives of older people. As a result, several international agendas have been put forward as part of regional development policies such as the African Union Policy Framework and Plan of Action on Ageing, addressing some of the region’s most pressing issues on ageing including rising urban poverty, informality, the effects of the HIV/AIDS pandemic, changing family support structures, complex migration flows, fiscal constraints, and inadequate social security schemes. However, despite this encouraging recognition, the representation of urban ageing in African, both in academic publications and policy discourse remains very low in comparison to the well-documented research and the overall awareness of the implications of ageing in cities in Global North countries [13,14,15,16,17,18,19]. This knowledge gap and the state of research on ageing in the region is concerning as Global South countries not only have the same demographic trends that characterise high-income countries, but they are also experiencing substantial population growth in urban areas [20,21].

Concerns over Africa’s changing age profile and the welfare of older persons have already been raised in studies by [3,4,6,9,10,11,12], and others who had examined Africa’s urban ageing in the context of health, poverty, and social change. The findings of these studies not only indicate a shift in the discourse on urban ageing, but also make a case for a detailed evaluation of the recognition and representation of the lives of older people in policy discourse. A ‘discourse’ is a term often used to refer to a specific ensemble of ideas, concepts, and categorizations that are produced, reproduced, and transformed in a particular set of practices and through which meaning is given to physical and social realities [22,23]). Discourses and policy documents generated by local and national government bodies are important artefacts as these organisations play a significant role in shaping or putting forward certain viewpoints and values of the lives of citizens. How people including senior citizens are represented through the written language encodes the ideas and assumptions that constitute the prevailing culture and ideologies surrounding their lives. Therefore, discourse analysis and artefacts evaluation are useful to identify the construction of a certain phenomenon or reality, such as urban ageing in a nation, how it is framed, and how the future representation is envisioned in society, in policy, and practice.

This paper contributes to research on African urban ageing through the examination of the representation of older people in the official policy discourse focusing on one of the continent’s most complex socio-economic and political urban contexts, the state of Zimbabwe. The paper examines the state of the representation of older people in Zimbabwe’s urban policy discourse and measures in place to address their demands. It brings together different bodies of knowledge on urban ageing, policy discourse, and inclusive urban development in the country. The emerging themes discussed in the paper are therefore critical to the debate on inclusivity [24] and the creation of inclusive urban environments, a concept that recognises the different needs, (cap)abilities, and requirements of people during their life course [25], thus advocates for the presence of diverse voices through processes of co-production and co-design.

The paper is structured in six sections; the introduction discusses the structure and background of the paper. It is proceeded by Section 2 which presents the landscape on urban ageing in Zimbabwe. Section 3 discusses the utilised methodology and textual examination of the documents. Section 4 discusses four thematic groups of discourse emerging from the analysis followed by the discussion of the findings in Section 5 and lastly, the Section 6 ends with concluding statements.

2. Urban Ageing in Zimbabwe

Zimbabwe’s urban areas, like many other cities in Africa, have been experiencing some drastic changes in the urban environment as a result of the increasing rate of urbanisation caused by complex rural-to-urban migration flows, socio-political tensions, and extreme strain on basic services. Over the years, significant parts of urban Zimbabwe has been progressively forced into urban poverty and informality as a consequence of the dire socio-economic climate and state-led evictions [26,27,28].The reality of this complex socio-political urban context has resulted in the establishment of a scholarly discourse investigating “why and what“ are the key factors at play in the current urban environment and “how” Zimbabwe’s urban areas can promote inclusivity and improvement of quality of life for urban Zimbabweans. This includes research into issues of urbanisation, politics, and planning [20,29,30], informality [20,31,32,33,34], inclusivity [35], rights and citizenship [36]. Parallel to these research efforts is the commitment in the policy discourse on promoting rhetoric of change and betterment for the citizens through adherence to international agendas and national development strategies. Such commitment to international development programmes could open up opportunities for the country to benefit from the abilities and contributions of older people within the community.

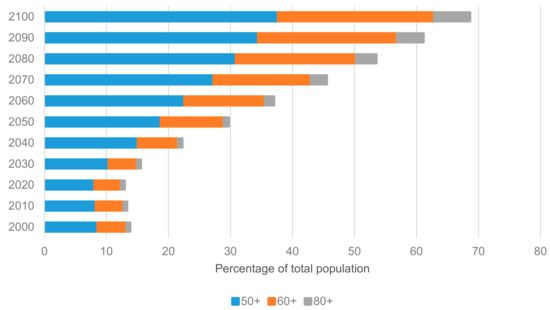

In the middle of the rising urban challenges facing the country, Zimbabwe is also experiencing an increase in the absolute numbers of older people residing in urban areas [37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46]. Figure 1 demonstrates how the percentage of the total population over the age of 50 is expected to quadruple, from 8.6 percent in 2000 to nearly 38 percent in 2100. The proportion of older people over the age of 60 years is also projected to increase more than 5 times, from 4.7 percent in 2000 to 25.2 percent in 2100 [47]. This demographic shift brings its own challenges to the state of Zimbabwe. With increasing age, numerous underlying physiological changes occur, and the risk of age-related losses and non-communicable diseases [37,38]. But the changes that constitute and influence ageing in urban Zimbabwe are far more complex and beyond these biological losses. The small corpus of Zimbabwean scholarly discourse evidences the social and economic implications of urban ageing. Publications from early post-colonial Zimbabwe were concerned with increasing housing demands for older people [39,40], demands for social care and institutionalisation [41,42], changes in intergenerational transfers [43,44] and changes in family support, structures and households [45,46] for older people in Zimbabwean cities and towns. A common finding from these researchers indicated that many older black people particularly migrants from neighbouring countries were found to be homeless, living in informal housing, and working in the informal sector such as working as street vendors. An environment that [48] describes as one of “marginalisation and increasing pauperisation”.

Figure 1.

Predicted change in the proportion of the Zimbabwean population in older age groups (Authors adapted from United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division (2015)).

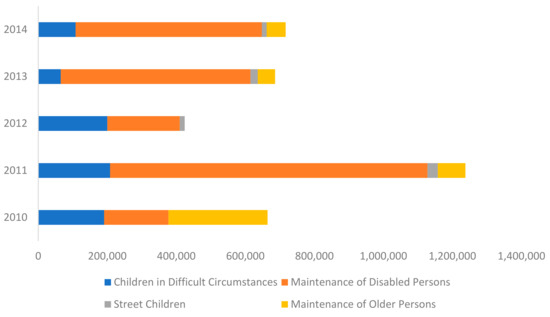

More recent studies on Zimbabwe’s urban ageing prove that the narrative of older people living in urban areas has not made any significant strides from the past. Most older people are still found to be working longer [49], living in poorer conditions with little care and support [50,51], and experiencing significant barriers in the urban space such as accessing healthcare and transportation [35]. There is increasing research on an older person’s health and well-being and the intersections with urban space. A cross-sectional survey by [52] on social support and institutionalisation in Bulawayo found most older people were at risk and experiencing poor mental health within care homes. Research by [53] on older people in an urban district in Harare, found that older people were excluded from certain activities in urban areas such as key information, education, and communication campaigns for HIV and AIDS because they are incorrectly regarded as sexually inactive and not susceptible to contracting sexually transmitted infections. Systematic evaluations of social security provisions in Zimbabwe over the past two decades describe consistent experiences of old age under persistent poverty and resource constraints [50,54,55]. The social assistance programs and maintenance of older persons in specific have been negatively impacted by the weak performance of the economy. It is a situation that has persisted for many years as shown in Figure 2 which illustrates the significantly low provision of maintenance of older persons when compared with other groups [56,57]. Contrary to the persistent narrative of marginalisation of Zimbabwe’s older urban citizens, are findings from studies indicating the valuable roles that older people, particularly older women play in urban communities such as through community building programmes [58,59], crucial caregivers and family contributors [55,60,61], sharing knowledge and building symbiotic relationships between older persons and their families [62].

Figure 2.

Social assistance programs from 2010 to 2014 (Authors adapted from (Government of Zimbabwe and The World Bank, 2016)).

Whereas these studies have provided valuable insights into urban ageing in Zimbabwe, to the authors’ knowledge, to date there has been no evaluation of the discourse that is created and used to shape the lived realities of older people and identify their needs.

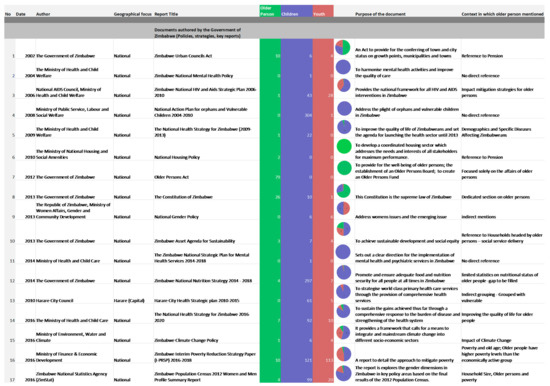

3. Methodology

To facilitate the investigation of the visibility of older people in Zimbabwe’s policy discourse, a collection of 45 documents produced for international and national urban development programmes specific to the region was selected. The documents were chosen following a systematic search for relevant publications and according to the selection criteria given in Table 1. The search identified literature published after 2002 justified by the first global acknowledgment to improve the lives of older people made by Zimbabwe at the Second World Assembly on Ageing in 2002 as well as in the African Union Policy Framework and Plan of Action on Ageing adopted in the same year. Therefore, the selected documents are intended to trace the change in the representation of older people in policy discourse from the first steps of international commitment in 2002 until present.

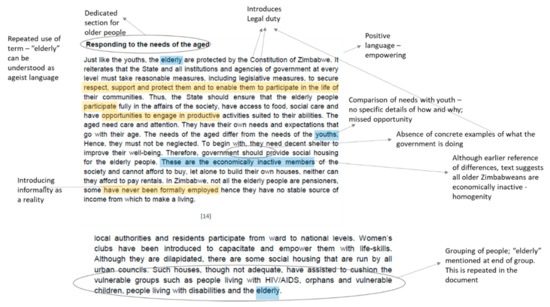

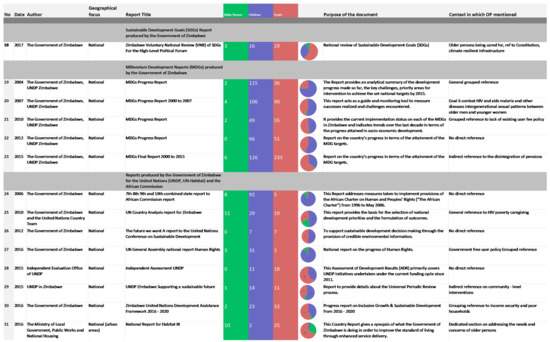

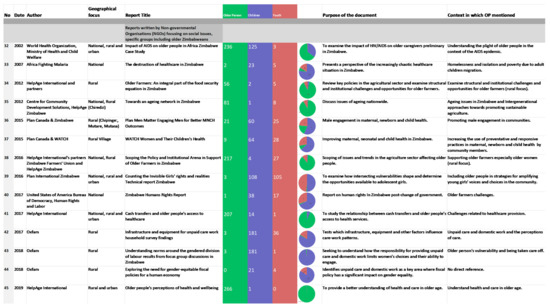

Table 1.

Inclusion criteria for reviewed literature.

The search engine Google was used to locate websites operated by the Government of Zimbabwe, ministerial bodies, and Non-Governmental Organisations involved in sustainable development and the promotion of inclusive communities. Targeted searches were conducted for documents through snowballing, identifying publications in reference lists, and expert recommendations. For ease of review, the publications were grouped into four main categories: first, policy documents and strategies produced by the Government of Zimbabwe and government departments (no = 17); second, a national review for Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and the progress reports produced by the Government for the Millennium Development Goals committed to at the Fifty-Fifth Sessions of the United Nations General Assembly in September 2010 (no = 6); third, periodic review reports and key documents reflecting national priorities and interventions authored by the Government for the United Nations and African Commission (no = 8) and, lastly, papers and research reports published by Non-Governmental Organisations working on the improvement of the lives of Zimbabwean citizens including reports focused solely on older persons (no = 14). NVivo 10, a well-known qualitative data analysis software tool, was used to help the systematic storing, retrieval, evaluation, and interpretation of the texts. A key aspect of the analysis was to examine the “form” and “texture”, the relations between the elements of the text as well as its characteristics including language and style. An example of these aspects of the analysis is presented in an Excerpt from the 2015 National Report for Habitat III in Figure 3. Further information on the content of this document is given in the discussion sub-sections. Figure 4, Figure 5 and Figure 6 give further details about the selected documents and the word frequency results.

Figure 3.

Example of textual analysis (language) in in the National Report for Habitat III (Republic of Zimbabwe, 2015) (N.B: This image shows two different coding colours, “blue” for negative terms and “gold” for positive terms).

Figure 4.

Word frequency and collocation of documents authored by the Government of Zimbabwe (policies, strategies, key reports).

Figure 5.

Word frequency and collocation of documents for international agenda.

Figure 6.

Word frequency and collocation of documents written by Non-Governmental Organisations (NGOs) focusing on social issues, specific groups including older Zimbabweans.

4. Findings

The key thematic discourses that emerged from the document(s) review are presented in the following section. The findings of the analysis are discussed under four sub-sections of discourse: invisibility (Section 4.1), vulnerabilities (Section 4.2), rights (Section 4.3), gender, care, and contribution (Section 4.4).

4.1. Discourses of Invisibility

There is a clear paucity of mention of older persons in the content of the analysed documents, suggesting that the sekuru (older man) or gogo (older woman) is not a priority age group in Zimbabwe. Across the majority of the documents published by the Government from 2002 to 2017 (Figure 4) the word “older people” was only mentioned about 150 times in comparison to other groups (977 times for “children” and 225 for “youth”). The only exception with a word frequency of 305 was the current national healthy ageing strategy, a document that was solely published to “promote healthy ageing and delay functional inability among older persons” (Figure 4, document no. 16). A similar trend on the paucity of mention of older persons was also found across all the documents produced for the international agenda (Figure 5) (word frequency = 52) and in over half of the documents written by Non-Governmental Organisations apart from those specifically written to target certain ageing issues (Figure 6, documents no. 32, 34, 35, 38, 41 and 45). Disappointingly, the document review also reveals an inconsistency in the policy definition of older people. Section 82 of the Zimbabwean Constitution (Figure 4, no. 7) describes an older person as a person who is above the age of 70 years, whilst the Old Persons’ Act (Figure 4, no. 6) defines an older person as “a citizen of Zimbabwe aged 65 years or above, who is ordinarily resident”. To add to the confusion, the United Nations and Africa Union guidelines refer to an older person as someone who is 60 years and above whereas research conducted by Non-Governmental Organisations in Zimbabwe (Figure 5) uses the age 50 and over to define older persons. Therefore, data collected using the official national definitions risk missing out on vulnerable older people.

Older persons are referred to indirectly in groupings such as “the disadvantaged”, “the poor”, and “the vulnerable” (example in Figure 3). While there was no evidence to suggest that older people have been included in any of them, no definition of who is/was encompassed by these terms was given either. An illustration of this style of writing is shown in Excerpt (1) below from the Zimbabwe National HIV and Aids Strategic Plan (Figure 4, no. 3), which discusses mitigation efforts for households. Older person headed households are not included in the plans for mitigation despite evidence-based research suggesting the existence of such structures as a result of the HIV/AIDS epidemic [63]. Another dimension of exclusion is displayed through the level of participation and consultation for the development of the documents. Aside from the reports solely focused on the issues of older people (Figure 6), the mention of older persons is minimal across the sample. In some cases, a list of groups and persons consulted in the production of the reports is included, however, in general, no explicit reference to older person groups is mentioned. An example of this lack of engagement with senior persons is evident in Excerpt (2) taken from the 2017 Zimbabwe Voluntary National Review of Sustainable Development Goals (Figure 5, no. 18). Surprisingly, some documents with a large focus on older persons such as the Social Security Policy only mentioned one person out of 84 representing older people. This lack of representation is despite consistent rhetoric within the document championing inclusive consultation (Excerpt 2). Several documents such as the National Healthy Ageing Strategy displayed a robust list of participating organizations during the strategy development process. Although noticeably organisations representing less visible older persons, such as older people living in informality and disabled older people, were not explicitly mentioned.

Mitigation programmes include programmes to support OVCs with a minimum package of services, and food aid, nutritional support and other assistance to vulnerable households and communities, including women-and child-headed households and those with chronically sick family members. (Excerpt 1, UNAIDS, 2006, pg 19 (emphasis added))

Social protection policies and programmes will be based on evidence gathered from research and consultations to ensure that the policies and programmes address the needs identified and target people who meet the eligibility criteria. To this end, the government will collaborate with academia, public and private research institutes and consultancy companies to gather the evidence. (Excerpt 2, The Government of Zimbabwe, 2017, pg 33).

In coming up with the position paper, (the) Government undertook a wide consultation process which entailed multi-stakeholder workshops, and several follow up meetings. The stakeholders included government departments, private sector, civil society, academia, people with disabilities, UN Agencies and other development partners. (Excerpt 3, The Government of Zimbabwe, 2017, pg 12).

The Habitat III report (2015) improves on the details of consultation by listing an attendance register for a country workshop. This register includes representatives from local city councils, Non-Governmental Organisations, and private companies, as well as organisations representing the youth such as the Young Voices Network. However, the workshop was not attended by any organisations representing older people such as HelpAge Zimbabwe. Interestingly, in this report, participation strategies were mentioned explicitly in the sections concerning youth and women, however there was no mention in the section dedicated to older persons. This is despite the evidence of statements such as the one below (Excerpt 4) made in the foreword by the Minister of Local Government, Public Works and National Housing. Other documents such as the MDG progress reports (Figure 5, no.19–23) mention the terms “all stakeholders” or “multi-stakeholder” in reference to consultation for the report without further elucidation as to who these stakeholders are and what they represent. A quote from the 2015 Habitat III report (Excerpt 5) below describes plainly the absence of a culture of participation and inclusion in developing urban development strategies.

This will be achieved through the active participation of all the critical stakeholders such as local authorities, financial institutions, private land developers, Community Based Organisations, investors (both local and international), civic society organisations employer and more critically, the end beneficiary. (Excerpt 4, The Government of Zimbabwe, 2019, pg 5 (emphasis added)).

Currently, there is a lack of platforms that promote the voices of the vulnerable and marginalised social groups to be heard. As a result, there is (a) manipulation of citizens by different powerful groups to enhance their own interests…Government and local authorities should be amenable to working with a diverse range of groups to promote participatory and inclusive approaches to urban development integrated with local economic development approaches for sustainability (Excerpt 5, The Ministry of Local Government, Public Works and National Housing, 2015, pg 19 (emphasis added)).

This absence of public voice may suggest that the majority group consisted of high-level government officials and scanty representation from members of civil society and Non-Governmental Organisations. On the contrary, the reports contain generic terms that appear to encompass all social groups of society, such as “users”, “consumers” and “households”. With older people left behind in consultation and participation, this removes any opportunity for them to contest negative identities related to ageing and ageing in poverty and informality.

4.2. Discourses of Vulnerability

In the reports authored by the Government for the United Nations (Figure 3) the language presents itself as standard, assuming that the reader will be familiar with the UN written approach. This standardised style of writing may exclude non-academic readers or readers with difficulty understanding UN jargon. The term “elderly” to represent older people is widely used in almost all the documents that mention older people. This is a term that can be viewed as ageist, presenting older people as being a homogeneous group always being viewed under the lens of vulnerability, as objects of pity and a burden [64]. A significant turn from the use of the term is shown in the 2016 Zimbabwe National Healthy Ageing Strategic Plan (Figure 4, no. 16), which only uses the term “older persons” to refer to Zimbabweans over the age of 65. Although this term is much more accepted, “older” is a nebulous term defined variously by researchers, services, and older people themselves. It is often used as an encompassing term even though the needs of a 55-year-old will be very different from those of an 85-year-old, and this is often not taken into consideration in urban policy discourse.

The document analysis suggests that older people, or at least sub-groups of them, are conceptualised as being “vulnerable” and living in vulnerable circumstances [47], for which without any support, their quality of life would be seriously compromised. Most documents acknowledged that the integral public services, such as affordable housing and accessible healthcare required to support older people in Zimbabwe, are often lacking or of poor quality and inadequately funded. Severe economic challenges have persistently exacerbated the already precarious situation for older people as shown in Excerpts 6 and 7 below from the Habitat III (2015) paper in the dedicated sections on older people (Figure 5) and in the Zimbabwe National Healthy Ageing Strategic Plan 2017–2020 (Figure 4).

In an ideal economy, the government should provide grants to senior citizens. But in Zimbabwe, it has been difficult to provide this social net to the senior citizens and they have been forced by the situation to fend for themselves. Given that their abilities are now compromised due to age, it is difficult for the old-aged people in Zimbabwe to make ends meet (Excerpt 6, The Ministry of Local Government, Public Works and National Housing, 2015, pg 15).

The hyper-inflationary environment experienced during the years 2000–2010 eroded the savings of older persons’ pensions and social security. Low access to health care and social security (pension, social grants and insurance) for older persons and unavailability of medicines for chronic non-communicable diseases at public health facilities in Zimbabwe increased health-related expenditure among older persons (Excerpt 7, Ministry of Health and Child Care and WHO, 2017, pg 13).

This challenging environment combined with the lack of support places a strain among various groups of the society including older people, consequently, pushing them into poverty and informality (Figure 7). The language used often paints a picture of older people as “vulnerable”, “poor” and “disadvantaged” or as those who are not able to compete on an equal basis for resources and opportunities. The 2016 Women and Men Profile Summary Report (Figure 4, no. 15) supports this image by discussing the evidence of poverty and vulnerability experienced by households headed by older persons based on the 2012 population census (Excerpt 8). This pattern of representation is found across most documents such as the Harare City Health Strategic plan 2010–2015 (no. 13), Zimbabwe Interim Poverty Reduction Strategy Paper (I-PRSP) 2016–2018 (no. 16), UN Country Analysis report for Zimbabwe (no. 24), and Zimbabwe United Nations Development Assistance Framework (no. 29). An added vulnerability is illustrated in the Excerpts below (9 and 10) which admittedly describe how older people without the family support structure and assistance from the state are being left behind.

Figure 7.

Older female resident in Gunhill informal settlement in urban Harare (left) and informal residents of Gunhill settlement (right) (Source: First Author, 2015).

Elderly-headed and female-headed households are larger and hence more vulnerable to poverty than other households. (Excerpt 8, Women and Men Profile Summary Report, 2016, pg 22)

Zimbabwe does not, at present, have a comprehensive social insurance scheme. Also, the vast majority of Zimbabweans are working in the informal economy and are largely not covered by social insurance. (Excerpt 9, National social protection policy framework for Zimbabwe and care, pg 13)

Traditionally, the extended family system was responsible for providing social support and care to its members. However, the processes of urbanization, industrialization, and globalization have gradually weakened the cohesiveness of the extended family system, thereby undermining its capacity to provide social support and care to its members. This void is increasingly being filled by the state and non-state actors, but they are constrained by lack of adequate resources to provide meaningful social support. (Excerpt 10, National social protection policy framework for Zimbabwe and care, pg 16)

4.3. Discourses of Rights

The New Constitution (2013) is the supreme law of Zimbabwe and the obligations imposed by it are binding on every person, natural or juristic, including the State and all executive, legislative and judicial institutions and agencies of government at every level, and must be fulfilled by them. The document contains a dedicated section for older persons. This serves as a positive recognition of older persons and the need to support and protect them. Positive and empowering words such as “enabling” and “participation” in the community are also used (see Excerpt 11).

1. The State and all institutions and agencies of government at every level must take reasonable measures, including legislative measures, to secure respect, support, and protection for elderly persons and to enable them to participate in the life of their communities.

2. The State and all institutions and agencies of government at every level must endeavour, within the limits of the resources available to them—a. to encourage elderly persons to participate fully in the affairs of society; b. to provide facilities, food and social care for elderly persons who are in need; c. to develop programmes to give elderly persons the opportunity to engage in productive activity suited to their abilities and consistent with their vocations and desires; and d. to foster social organisations aimed at improving the quality of life of elderly persons. (Excerpt 11, Republic of Zimbabwe, 2016, p. 22) (emphasis added).

A rights-based language is used to articulate the right to healthcare and financial assistance in a dedicated paragraph on the rights of older persons. The recognition of older people’s human rights in the New Constitution was perhaps fuelled by the Protocol on the Rights of Older Persons to the African Charter on Human and People’s Rights created in April 2012 [47]. This rights-based language is reflected in the Older Persons Act 2012 produced a year before the publication of the New Constitution. The Older Persons Act was created to provide for the well-being of older persons and the establishment of an Older Persons Board and Older Persons Fund. Positive affirmative language such as “equal opportunities”, “independent lives”, “improving well-being, and social and economic status” can be found in the Act. In tandem with the New Constitution, the National Gender Policy (Figure 4, no. 8) introduced in the same year (2013) recognises that men and women have a right to equal treatment, including the right to equal opportunities in political, economic, cultural and social spheres. It was the first policy to accord women the right to custody and guardianship and make void all laws, customs, cultural practices, and traditions that infringe on the rights of women and girls. There is no direct mention of older women. Despite the discourse of recognition of the rights of older people, the processes and structures suggested to support the actualisation of rights can be confusing, counterproductive, and ineffective. The quote below found in the state report for the 2006 African Commission (Figure 5, no. 24) suggests a process for ensuring the right to physical and mental health for older people but also admits that this process may not be fully functioning. Further confusion is regarding the misalignment of definitions between the Constitution and the Older Persons Act which may impact the rights of older Zimbabweans as discussed in Section 4.1.

Assessments are done by the District Social Welfare officers and these target children whose parents are not working, orphaned children, the elderly, and those affected by the HIV/AIDS pandemic. These are given free medical Treatment Orders to present to the Hospitals which receive the money from the Department of Social Welfare. The Department sometimes faces a challenge in updating payments due to financial constraints and the ever-increasing costs of medical treatment (Excerpt 12, The Government of Zimbabwe, 2006, Pg 56).

4.4. Discourses of Gender, Care and Contribution

Families irrespective of the nature of the welfare regimes they are embedded in are central to the debate about how societies will face the challenges of population ageing. In Zimbabwe, most older people live in intergenerational households, and therefore the challenges of an older person are as much a household issue as an individual one. This context is clearly expressed in Excerpt 14 from a HelpAge study on older people in Zimbabwe. Ageing is, therefore, occurring in a context where support from the family or the government cannot be relied upon. As a further result of the socio-economic and political changes in Zimbabwe, older people are found to be both in need of care but also giving care. This is particularly relevant for older women who are found to be the majority of caregivers within Zimbabwean households. Women make up not only most of the old in Zimbabwe but also the majority of the poor old. Excerpt (15) below from the Zimbabwe National Healthy Ageing Strategic Plan 2017–2020 reinforces this reality.

Gender is a significant factor in the perception of health status, with older women perceiving their health status to be poorer than older men, despite reporting higher levels of access and engagement with self-care (Excerpt 14, HelpAge International, 2019, pg 27)

Older female persons are often worst affected by poverty, economic challenges, and disease burden, mainly because they are not eligible for social security pension and medical aid contributions since they were generally never formally employed. (The) majority of women work in the informal sector as cross-border traders, vendors, smallholder farmers, and unpaid carers (Excerpt 15, Ministry of Health and Child Care and WHO, 2017, pg 13).

Despite the frequent mentions of women in the analysed documents, there is a larger emphasis on younger women. Evidence of this trend is traced in the reports focused primarily on women’s issues (Figure 4, Figure 5 and Figure 6, document no. 8, 15, 37, 39, and 44) sharing only a total of (n = 16) direct mentions of older women as opposite to (n = 163) direct mentions of younger women. Older women are rarely mentioned directly, and indirect referencing is buried in the general commentary. Some direct references are illustrated in Excerpts 16 to 19.

In addition, the turn of the millennium saw a phenomenal increase in outward migration…The poverty and vulnerability of the households that migrants leave behind are also exacerbated by the fact that it is generally the most productive members who engage in migration…The country has also carried an increasing number of orphans and other vulnerable children…the majority of these children are under the care of the elderly or in female-headed households (PASS II). (Excerpt 16, Government of Zimbabwe and United Nations Country Team, 2010, pg 28,46).

Furthermore, existing mitigation strategies have been too narrow, focusing on the survival of certain categories of individuals and communities such as orphans and child-headed households, while neglecting the needs of other vulnerable population groups…Impact mitigation should be extended to elderly caregivers. (Excerpt 17, Zimbabwe National HIV and Aids Strategic Plan, 2006, pg 21).

Older female persons are often worst affected by poverty, economic challenges and disease burden…the associated stress of caring for such children increased the risk of some non-communicable diseases among the older persons. Older women were disproportionally affected by this stress as they are more likely to be the primary caregivers. (Excerpt 18, Government of Zimbabwe, 2019, pg 5).

The Government has set up an Inter-Ministerial Committee on Rape and Sexual Violence to carry out thorough investigations into the causes of rape of minors and elderly women (Excerpt 19, United Nations Zimbabwe, 2016, pg 14).

5. Discussion: Discourses of Ambivalence

The findings of the discourse analysis discussed in the previous sections suggest that there is a need for a shift from ambivalence and towards deliberate consideration of the interests of older people in the urban development discourse. Much of this is evidenced by the silence in the texts examined. The documents demonstrate the efforts being undertaken towards sustainable development for over 17 years with the most recent policy report produced in 2019. Aside from the documents focused solely on older people, the discourse analysis indicates an inconsistency in the recognition of the needs and desires of older people over the two decades. Specifically, the findings suggest that there is an oscillation between representations. On one hand, older people are perceived as “vulnerable”, “deficient”, “in-need” and on the other hand, they are “embedded in the family”, “contributors”, “care-givers”, worthy of “rights”, and “active participators”. The policy discourse evidences a continual fluctuation and uncertainty between the different representations. This can be understood as “ambivalence”. Ambivalence is a discursive perspective that demonstrates that older people and their role in Zimbabwe’s urban society are not clearly defined. Consequently, this ambivalence reflects an absence of clear progression towards the recognition of older persons. Any visibility of older people in wider urban policies and documents in Zimbabwe remains under-represented along with other categories of “otherness” such as disabled people and homeless people. This finding aligns with global discourses of vulnerability which represent older people as an economic burden on society reinforcing their marginality [65] and endangering their levels of social and economic well-being. The lack of discussion of older people in the urban policy discourse could indicate that there is a consensus on the positioning of older people within the safety net of the family. Such assumptions reinforce the discourses of ambivalence by contrastingly framing older people as vulnerable and invisible but also suggesting that the family unit provides a supportive, participatory, and visible environment for them. It is also a counter perspective to the global scholarly arguments that frame older people as active urban citizens [14,15,66]. The findings highlight the key function of family and the economic status of the family of the older person in determining their care and support. The pivotal nature of the family unit in influencing older people’s economic and social well-being is reflected in the global discourse on ageing [67]. Additionally, there is a gendered form of ambivalence aligning with global trends [11,68,69,70,71]. The discourse on caregiving is largely targeted at the women within the family unit. They take on the caregiving responsibility for spouses, other family members, and peers while often needing care themselves [55]. Therefore, older women on a structural level are still expected to do the larger proportion of care work and in line with cultural norms are expected to find this work fulfilling and to not resist. The findings suggest that older women are still very much assumed to be spatially located in the home.

The narrative on older people is still largely limited to discourses from Government departments for social work and healthcare, lacking integration into wider areas of national policy. For example, documents that focus on urban planning and housing such as the national housing policy and local reports regarding sustainable development make no or little mention of older people. This is despite research evidencing the crucial need for including older people in policy discourse such as housing policies and plans [39,72]. Thus, indicating a lack of recognition and value of the person-environment relationship in the wider discourse. Although the local discourse in the strategic plans for Harare reflects a city that is aiming to cater for all its citizens, it crucially lacks articulation on how it endeavours to meet these diverse needs and abilities such as through transport and road infrastructure. Global initiatives such as the WHO Age-Friendly Cities framework [73,74] recognise that an older person’s functional ability begins to depreciate, such as mobility, and they become aware of the level of care opportunities in the home, neighbourhood, and city [75]. Therefore, the absence of discourse on the relationship between older people and the urban environment in Zimbabwe excludes the nation from a global discussion that is becoming increasingly relevant.

Contrastingly, Zimbabwe has shown an emergence of a discourse based on citizenship and rights [76,77] arguing for innovative ways of thinking of older Zimbabweans living in urban spaces. Key legislation such as the Constitution, the Older Persons Act, and Healthy Ageing Strategy demonstrate an active commitment to action that is rights-based and enabling. However, the evidence of ambivalence is shown in the exclusion of older persons in participating and developing policy. By enabling older persons’ right to the city and that of other urban citizens, the relatively high control of the narrative by the national government and state elites is challenged over decisions regarding the organisation and management of the city and its spaces. Therefore, the discourse on citizenship requires processes that foster transparency, accountability, and the democratisation of data for decision making as well as the allocation of opportunities and resources. More effort is needed to actively engage with older people and empower them to be agents of change. Indeed, this is a challenge that is reflected in many urban African centres where the benefits from the ability of cities to create an environment where all citizens can easily interact, be productive, be mobile and succeed, is still lacking [20,78,79,80].

Engaging with older people at a meaningful level requires a recognition of the heterogeneous nature of ageing. As mentioned in Section 4.1 and Section 4.2, there is significant inconsistency in the policy definition of older people with different age ranges cited in different documents. The use of different chronological definitions of older people presents challenges related to asserting the rights of older persons guaranteed in the legislative framework. The ambivalence of definition and identity as shown in the findings exposes the limitations of notions that older people’s social urban realities are singular and can only be included in the group of older people at a certain age. This perspective links to wider academic discourses that are challenging this homogenous representation through approaches such as the life course approach that emphasises a temporal and social representation of ageing. This approach recognises the diverse contexts which may change and influence an older person’s identity throughout their life [81]. Therefore, ageing does not become a matter of chronology but about restricted functionality and activity. Crucially, older people who endure a lifetime of poverty, malnutrition, and heavy labour may be chronologically young but “functionally” old at age 50 [82]. Instead, the discourse should address what interventions are needed to improve, restore, and maintain physical and mental functionality [83]. The health and healthcare needs of an older person are better related to proximity to death, rather than chronological age [84]. Chronological age, therefore, becomes a weak predictor of need. By considering the context of a person and their life course, strategies, and resources used for coping with ageing by individuals and communities can be established at a much earlier point in life. Furthermore, positioning the ageing discourse within a life course perspective illuminates critical linkages that can exist between the lives of older and younger generations. This highlights the potential for intergenerational strategies, an aspect that is inadequately recognised in the discourse. In recognising diversity in old age, opportunities open up for the reconsideration of the design of the urban space with special attention to issues such as physical accessibility, adequate and affordable healthcare services, transport infrastructure, and inclusive public spaces.

Who an older Zimbabwean is and what their daily lives look like as they age is not simply understood. Rather, what has emerged from the discourse analysis is that the notions of seniority are not fixed. To adequately cater for the needs of older people, their lived experiences must be viewed through the lens of inclusivity. However, the commitment to inclusivity by key actors in Zimbabwe’s national and local government needs to go beyond policy rhetoric and translate into inclusive practices that will foster the needs of older people on the ground. For inclusivity to be meaningful, a significant shift is needed, that will create new levels of dialogue requiring persons with power to make space for those without.

6. Conclusions

This study aimed to contribute an understanding of urban ageing in Zimbabwe by analysing the socio-political discourse. The authors have approached urban ageing as an evolving concept in policy discourse. Ageing is experiencing a global shift in recognition and is becoming a vehicle to discuss, interpret, and relate to the role of inclusive and healthy sustainable urban development. The concept of urban ageing in Zimbabwe requires a combination of knowledge that evolves from different discourses as discussed in Section 4. Currently, there seems to be an ambivalence in the representation of older people living in Zimbabwe’s urban spaces. The review of the policy discourse presented in the paper demonstrates an element of inconsistency in the representation of older people across the documents. Re-thinking the discourses/thoughts emerged from this review may therefore offer an initial basis for transforming the discursive order identified and create alternative representations of older people and policy options. A broader conceptualisation of ageing needs to be evident in the policies for older people such as the Older Persons Act and the national healthy ageing strategy. This will include a diversity of experiences and the enhancement of the level of care. Furthermore, the intersections of age and gender need to be better understood and addressed within the urban discourse. Revised versions of the national gender policy should sufficiently address older men and women and their differences in lived experiences. Furthermore, older people need to be visible as key stakeholders in urban policies such as housing and planning.

Zimbabwe has recently demonstrated a strong commitment to economic, environmental, and social sustainable development programmes through the obligations made towards international and regional legal instruments. As a nation, Zimbabwe continues to experience severe socio-cultural and economic challenges. Recent Government actions including restricting the internet access during the censorship shutdown in January 2019, the demolition of informal houses and the mass protests and arrests during the current global health crisis could be seen as a step backwards. This undermines the progress made to support the diverse and inclusive voice of Zimbabweans. Major positive strides have been made over the last twenty years in bringing to the forefront issues of gender equality and combating HIV/AIDS. Despite these emerging efforts, the attention given towards ageing-related issues including the feminisation of ageing and the contributory role of older people is still limited. The findings strengthen the case on why Zimbabwe’s policymakers, local authorities, civil society organisations, and urban practitioners should address older people and their needs as a priority. More data and knowledge about older people are needed to break away from stereotypes and cultural assumptions that disadvantage them. At a more local level, the ambivalence in the profiles of older people living in urban spaces encourages a closer look into older persons that may not be that visible in the discourse such as those living in informal settlements.

In terms of scope, the study is limited in its geographical focus on the urban context within Zimbabwe. Additionally, the selected timeframe of the documents reviewed may also have missed out more recent publications. However, the findings discussed in this paper are mainly based on the first stage of a wider study on “older people in urban Zimbabwe”. The second stage of this research will present the findings from interviews with policymakers and senior residents and will be shared with the academic community as part of future publications.

Author Contributions

Authors, B.C.N.M. and S.A.-M. contributed to all aspects of this research. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Yen, I.; Shim, J.; Martinez, A.; Barker, J. Older People and Social Connectedness: How Place and Activities Keep People Engaged. J. Aging Res. 2012, 2012, 139523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peace, S.; Wahl, H.-W.; Mollenkopf, H.; Oswald, F. Environment and Ageing. In Ageing in Society: European Perspectives in Gerontology, 3rd ed.; Bond, J., Peace, S., Dittmann-Kohli, F., Westerhoff, G.J., Eds.; SAGE publications Ltd.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Aboderin, I. Poverty and Old Age in Sub-Saharan Africa: Examining the Impacts of Gender with Particular Reference to Ghana. The International Handbook of Gender and Poverty Concepts, Research, Policy: ElgarOnline; Chant, S., Ed.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboderin, I. Understanding and Responding to Ageing, Health, Poverty and Social Change in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Strategic Framework and Plan for Research. 2005. Available online: http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.555.4371&rep=rep1&type=pdf (accessed on 1 December 2020).

- Aboderin, I. Understanding and Advancing the Health of Older Populations in sub-Saharan Africa: Policy Perspectives and Evidence Needs. Public Health Rev. 2010, 32, 357–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboderin, I. Development and Ageing Policy in Sub-Saharan Africa: Approaches for Research and Advocacy. Glob. Ageing Issues Action 2007, 4, 7–22. [Google Scholar]

- Aboderin, I.; Ferreira, M. Linking Ageing to Development Agendas in Sub-Saharan Africa: Challenges and Approaches. J. Popul. Ageing 2008, 1, 51–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aboderin, I.; Hoffman, J. Families, Intergenerational Bonds, and Aging in Sub-Saharan Africa. Canadian Journal on Aging 2015, 34, 282–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoffman, J.; Aboderin, I.; Keating, N. A Research Agenda on Families and Ageing in Africa; National Academies Press: Potchefstroom, South Africa, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Apt, N.A. Ageing and the Changing Role of the Family and the Community: An African Perspective. Int. Soc. Secur. Rev. 2002, 55, 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apt, N.A. Aging in Africa: Past Experiences and Strategic Directions. Ageing Int. 2011, 37, 93–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apt, N.A.; United Nations. Rapid Urbanization and Living Arrangements of Older Persons in Africa. 2001. Available online: http://www.un.org/esa/population/publications/bulletin42_43/bulletin42_43.htm (accessed on 1 December 2019).

- Buffel, T.; DeDonder, L.; Phillipson, C.; DeWitte, N.; Dury, S.; Verte, D. Place Attachment Among Older Adults Living in Four Communities in Flanders, Belgium. Hous. Stud. 2012, 29, 800–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buffel, T.; Phillipson, C.; Scharf, T. Ageing in urban environments: Developing ‘age-friendly’ cities. Sage J. Crit. Soc. Policy 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menec, V.H.; Means, R.; Keating, N.; Parkhurst, G.; Eales, J. Conceptualising Age-Friendly Communities. Can. J. Aging 2011, 30, 479–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finkelstein, R. Toward an Age-Friendly New York City: A Findings Report; New York Academy of Medicine: New York, NY, USA, 2008; p. 64. [Google Scholar]

- Fitzgerald, K.G.; Caro, F.G. International Perspectives on Age-Friendly Cities; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Plouffe, L.; Kalache, A. Towards Global Age-Friendly Cities: Determining Urban features that promote active aging. J. Hered. 2010, 87, 733–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steels, S. Key characteristics of age-friendly cities and communities: A review. Cities 2015, 47, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mbiba, B. On the Periphery: Missing Urbanisation in Zimbabwe. 2017. Available online: https://www.africaresearchinstitute.org/newsite/publications/periphery-missing-urbanisation-zimbabwe/ (accessed on 1 October 2019).

- Teguo, M.T.; Kuate-Tegueu, C.; Dartigues, J.-F.; Cesari, M. Frailty in sub-Saharan Africa. Lancet 2015, 385, 2151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fairclough, N. Language and power; Longman: London, UK, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Reed, M. The Limits of discourse analysis in organizational analysis. Organization 2000, 7, 524–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, R. Inclusive Design. 2014. Available online: http://cmap.upb.edu.co/rid=1153176144406_1235390754_1547/Inclusive%20Design.pdf (accessed on 1 May 2018).

- Kuh, D.; Karunananthan, S.; Bergman, H.; Cooper, R. A life-course approach to healthy ageing: Maintaining physical capability. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2014, 73, 237–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potts, D. ‘Restoring Order’? Operation Murambatsvina and the Urban Crisis in Zimbabwe. J. S. Afr. Stud. 2006, 32, 273–291. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/25065092 (accessed on 1 June 2020). [CrossRef]

- Chibisa, P.; Sigauke, C. Impact of operation murambatsvina (restore order) on flea markets in Mutare: Implications for achieving mdg 1 and sustainable urban livelihoods. J. Sustain. Dev. Afr. 2008, 10, 31–65. [Google Scholar]

- Tibaijuka, A. Report of the Fact-Finding Mission to Zimbabwe to assess the Scope and Impact of Operation Murambatsvina Zimbabwe. 2005. Available online: http://www.un.org/News/dh/infocus/zimbabwe/zimbabwe_rpt.pdf (accessed on 1 February 2019).

- Potts, D. We Have A Tiger by The Tail’: Continuities and Discontinuities in Zimbabwean City Planning and Politics. Critical African Studies 2011, 4, 15–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Potts, D. Whatever Happened to Africa’s Rapid Urbanisation? 2012. Available online: http://www.relooney.com/NS4053/00_NS4053_303.pdf (accessed on 1 April 2019).

- Chitekwe-Biti, B. Struggles for urban land by the Zimbabwe Homeless People’s Federation. Environ. Urban. 2009, 21, 347–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chitekwe-Biti, B.; Mudimu, P.; Nyama, G.M.; Jera, T. Developing an informal settlement upgrading protocol in Zimbabwe—the Epworth story. Environ. Urban. 2012, 24, 131–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamete, A. Neither friend nor enemy: Planning, ambivalence and the invalidation of urban informality in Zimbabwe. Urban Studies 2020, 57, 927–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogerson, C. Responding to Informality in Urban Africa: Street Trading in Harare, Zimbabwe. Urban Forum 2016, 27, 229–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ncube, C.; Ormerod, M.; Newton, R. Exploring Ageing, Gender and Co-producing Urban Space in the Global South. Int. J. Urban Plan. 2016, 16, 23–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muchadenyika, D.; Chakamba, M.K.; Mguni, P. Informality and Urban Citizenship — Housing struggles in Harare, Zimbabwe. In The Routledge Handbook on Informal Urbanization; Rocco, R., Ballegooijen, J.V., Eds.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organisation. World Report on Ageing and Health; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organisation. The Epidemiology and Impact of Dementia Current State and Future Trends; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Nyanguru, A.; Peil, M. Housing and the elderly in Zimbabwe. South. Afr. J. Gerontol. 1993, 2, 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muchena, O. The African Aged in Town: A Salisbury Study, Mimeo; Retrieved from Harare: School of Social Work, Unpublished work, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Nyanguru, A. Residential care for the destitute elderly: A comparative study of two institutions in Zimbabwe. J. Cross-Cult. Gerontol. 1987, 2, 345–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hampson, J. Elderly people and social welfare in Zimbabwe. Ageing Soc. 1985, 5, 39–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamchak, D.J.; Wilson, A.O.; Nyanguru, A.; Hampson, J. Elderly Support and Intergenerational Transfer in Zimbabwe: An Analysis by Gender, Marital Status, and Place of Residence. Gerontologist 1991, 31, 505–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mupedziswa, R. Community living for destitute older Zimbabweans: Institutional care with a human face. S. Afr. J. Gerontol. 1998, 7, 2631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Nyanguru, A.; Hampson, J.; Adamchak, D.; Wilson, A. Family support for the elderly in Zimbabwe. S. Afr. J. Gerontol. 1994, 3, 22–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Hampson, J. Old Age: A Study of Ageing in Zimbabwe; Mambo Press: Gweru, Zimbabwe, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Ageing in the Twenty-First Century: A Celebration and a Challenge; United Nations Population Fund : New York, NY, USA; HelpAge International: London, UK, 2012; Available online: http://www.unfpa.org/publications/ageing-twenty-first-century (accessed on 1 June 2020).

- Hampson, J. Marginalisation and Rural Elderly: A Shona Case Study. J. Soc. Dev. Afr. 1990, 52, 5–23. Available online: https://archive.lib.msu.edu/DMC/African%20Journals/pdfs/social%20development/vol5no2/jsda005002003.txt (accessed on 1 January 2019).

- Zimbabwe National Statistics Agency Zimbabwe Population Census; The Zimbabwe National Statistics Agency (ZIMSTAT): Harare, Zimbabwe, 2012.

- Dhemba, J.; Dhemba, B. Ageing and Care of Older Persons in Southern Africa: Lesotho and Zimbabwe Compared. Soc. Work Soc. Int. Online J. 2015, 13, 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Nhamo, G. A Study on the Role of Old Age Institutions in the Care of Elderly People in the Context Of hyperinflation: The Case of Mucheke, Masvingo, Zimbabwe. Master’s Thesis, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Durban, South Africa, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Dhlamini-Sibanda, S.I.; Dube-Mawerewere, V.; Nkhoma, G.; Haruzivishe, C.O. A Study to Examine the Relationship between Social Support and Perception of Being Institutionalized among the Elderly Aged 65 Years and Above Who Are in Institutions in Bulawayo Urban, Zimbabwe. Open J. Nurs. 2017, 7, 905–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Gutsa, I. Sexuality among the elderly in Dzivaresekwa district of Harare: The challenge of information, education and communication campaigns in support of an HIV/AIDS response. Afr. J. AIDS Res. 2011, 10, 95–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhemba, J. Social Protection for the Elderly in Zimbabwe: Issues, Challenges and Prospects. Afr. J. Soc. Work 2013, 3, 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Dhemba, J. Dynamics of poverty in old age: The case of older persons in Zimbabwe. Int. Soc. Work 2014, 57, 714–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Government of Zimbabwe. National Social Protection Policy Framework for Zimbabwe; Government of Zimbabwe: Harare, Zimbabwe, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Government of Zimbabwe and The World Bank. Zimbabwe Public Expenditure Review; Government of Zimbabwe and The World Bank: Harare, Zimbabwe, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Chitekwe-Biti, B. Brick by Brick Transforming Relations between Local Government and the Urban Poor in Zimbabwe; IIED: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Dialogue on Shelter Thinking the Unthinkable and Doing the Improbable in Zimbabwe; Dialogue on Shelter: Harare, Zimbabwe, 2009.

- Mhaka-Mutepfa, M. Sociodemographic Factors and Health-Related Characteristics That Influence the Quality of Life of Grandparent Caregivers in Zimbabwe. Gerontol. Geriatr. Med. 2018, 4, 2333721418756995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mhaka-Mutepfa, M.; Cumming, R.; Mpofu, E. Grandparents Fostering Orphans: Influences of Protective Factors on Their Health and Well-being. Health Care Women Int. 2014, 35, 1022–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mbulayi, S.P.; Kang’ethe, S. Social constructions of successful ageing: The case of Ruware Park in Marondera, Zimbabwe. Soc. Work 2019, 55, 329–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chazan, M. Seven ‘deadly’ assumptions: Unravelling the implications of HIV/AIDS among grandmothers in South Africa and beyond. Ageing Soc. 2008, 28, 935–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lloyd-Sherlock, P. Nussbaum, Capabilities and Older People. J. Int. Dev. 2002, 14, 1163–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palloni, A. Living Arrangements of Older Persons; United Nations Population Bulletin, United Nations Population Fund: New York, NY, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Walker, A. Active ageing: Realising its potential. Australas. J. Ageing 2015, 34, 2–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilroy, R. Changing Landscapes of Support in the Lives of Chinese Urban Elders: Voices from Wuhan Neighbourhoods. Environ. Plan. C Gov. Policy 2013, 31, 428–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrientos, A.; Gorman, M.; Heslop, A. Old Age Poverty in Developing Countries: Contributions and Dependence in Later Life. World Dev. 2003, 31, 555–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falu, A. Equal Cities for Men and Women. Tools for Action. Master’s Thesis, National University of Cordoba, Córdoba, Argentina, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Tacoli, C. Urbanization, Gender and Urban Poverty: Paid Work and Unpaid Carework in the City; United Nations Population Fund: New York, NY, USA, 2012; Available online: http://www.unfpa.org/resources/urbanization-gender-and-urban-poverty (accessed on 1 February 2019).

- Tacoli, C.; Satterthwaite, D. Gender and Urban Change. Environ. Urban. 2013, 25, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butcher, C. Low Income Housing in Zimbabwe: A Case Study of the Epworth Squatter Upgrading Programme; University of Zimbabwe, Department of Rural and Urban Planning (RUP): Mt. Pleasant, Harare, Zimbabwe, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organisation. Age-Friendly World Adding Life to Years. Available online: https://extranet.who.int/agefriendlyworld/ (accessed on 28 June 2020).

- Aboderin, I.; Kano, M.; Owii, H.A. Toward “Age-Friendly Slums”? Health Challenges of Older Slum Dwellers in Nairobi and the Applicability of the Age-Friendly City Approach. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, J.; Pype, K. Ageing in Sub-Saharan Africa Spaces and Practices of Care; The Policy Press: Bristol, UK, 2016; p. 224. [Google Scholar]

- Kessides, C. The Urban Transition in Sub-Saharan Africa: Challenges and Opportunities. Environ. Plan. C: Gov. Policy 2007, 25, 466–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butera, F.M.; Caputo, P.; Adhikari, R.S.; Facchini, A. Urban Development and Energy Access in Informal Settlements. A Review for Latin America and Africa. Procedia Eng. 2016, 161, 2093–2099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chitonge, H.; Mfune, O. The urban land question in Africa: The case of urban land conflicts in the City of Lusaka, 100 years after its founding. Habitat Int. 2015, 48, 209–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organisation. Active Ageing: A Policy Framework; World Health Organisation: Geneva, Switzerland, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- HelpAge International. Insights on Ageing: A Survey Report; HelpAge International (HAI): London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Stephens, C.; Breheny, M.; Mansvelt, J. Healthy ageing from the perspective of older people: A capability approach to resilience. Psychol. Health 2015, 30, 715–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ustun, B.; Jakob, R. Re-Defining ‘Health’; Bulletin of the World Health Organization; World Health Organisation: Geneva, Switzerland, 2005; Available online: http://www.who.int/bulletin/bulletin_board/83/ustun11051/en/ (accessed on 1 September 2019).

- Vlahov, D. Urban Health: Global Perspectives, 1st ed.; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2010; 500p. [Google Scholar]

- Leeson, G.W. Environment, Health and Ageing. In Environmental Gerontology in Europe and Latin America; Sánchez-González, D., Rodríguez-Rodríguez, V., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany; New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).