Abstract

Sport psychology has generated an expansive body of literature on how psychological factors influence athletic performance, yet no review has systematically mapped this body of research. Guided by the PRISMA-ScR framework, this study charted published meta-analyses that investigated links between psychological constructs and sport performance. After conducting comprehensive searches, we identified 137 relevant papers, of which 73 met our inclusion criteria for athlete samples and performance outcomes. The included meta-analyses, published between 1988 and 2025, represented authors from at least 30 countries and covered more than 40 different constructs. Mental practice, confidence, achievement goals, anxiety, cohesion, mindfulness, and neurofeedback were the most frequently studied topics. Publication activity has accelerated rapidly since 2020, reflecting the maturation and diversification of evidence synthesis in sport psychology. Rather than aggregating effect sizes, this review maps methodological trends, recurring themes, and areas of limited coverage. The resulting catalog highlights where the evidence base is strongest, identifies emerging opportunities, and provides a foundation for future quantitative reviews to progress consensus development.

1. Introduction

Sport psychology has evolved into a globally recognized academic and applied discipline, with roots extending nearly 200 years. The beginning of sport psychology if we accept it as such with Carl Friedrich Koch’s 1830 publication [1], Calisthenics from the Viewpoint of Dietetics and Psychology [2]. Although the development of sport psychology has global roots [3], the field has been shaped primarily by Western scholarship [4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17]. Scholars have chronicled the evolution of the field and highlighted key figures, institutions, controversies, and trends over time. As such, the extent to which sport psychology constructs and findings apply across different cultural contexts remains in its infancy and requires more systematic exploration. Meta-analytic methods first entered the sport psychology literature in the 1980s, with landmark reviews by Feltz and Landers [18], Bond and Titus [19], and Mullen and Riordan [20]. To contextualize the scope of this review, we provide a brief review of meta-analyses entering the sport psychology literature and critically appraise our prior synthesis [21] to position the rationale for this scoping review.

1.1. The Rise of Meta-Analyses

The emergence of meta-analysis marked what seems to be a turning point for sport psychology as quantitative reviews offered a rigorous method for synthesizing findings across diverse studies and potentially signaling an expanding body of sport psychology literature. Although the statistical concept dates to Pearson’s [22] publication that is cited as foundational [23], it was not until 1983 that the first sport psychology-focused meta-analyses appeared, notably by Feltz and Landers [18] and by Bond and Titus [19]. A lesser-known contribution based on citations compared to the two 1983 meta-analyses, followed in 1988 by Mullen and Riordan [20], applying meta-analytic techniques to attribution theory. Also noteworthy is Meyers et al.’s [24] chapter titled Cognitive Behavioral Strategies in Athletic Performance Enhancement, which summarized 56 studies across 47 journals and remains a frequently cited resource. Whelan et al. [25] presented preliminary meta-analytic findings from this chapter at the American Psychological Association.

The buildup to published meta-analyses is, of course, grounded in single studies. Any one search is insufficient to capture the field’s scope. A Web of Science search using sport psychology as the keyword illustrates the scale of research growth: the first cataloged publication appeared in 1925 [26], followed by just 11 articles before 1970. That number grew to 288 in the 1970s, 880 in the 1980s, 1769 in the 1990s, 6939 in the 2000s, 14,561 in the 2010s, and 11,631 citations between 2020 and March 2025 alone. The volume reflects tremendous growth in the sport psychology published literature, particularly in western cultures. Feltz and Landers’ seminal meta-analysis on mental practice drew on 98 studies dating back to 1934. Bond and Titus conducted a cross-disciplinary meta-analysis on social facilitation, synthesizing 241 studies including Triplett’s [16] iconic work in cycling. Mullen and Riordan’s earliest citation was a Glyn C. Roberts conference presentation in 1975 [27]. These examples not only illustrate the historical reach of the sport psychology literature but also underscore the vital role meta-analysis plays in distilling insight from decades of findings.

Importantly, the rise of meta-analysis within sport psychology mirrors a broader scientific trend toward evidence synthesis and cumulative knowledge-building. Just as fields like medicine, education, and clinical psychology have relied on meta-analyses to inform best practice, sport psychology has adopted these methods to navigate its increasingly complex research base. This shift signals more than just methodological evolution. It reflects the growing credibility and relevance of sport psychology as both an academic discipline and an applied science. As will be detailed in the results, the post-2020 acceleration in meta-analytic publications speaks to global interest, rising methodological sophistication, and a commitment to generating practical, evidence-based guidance. In this way, meta-analysis is not just a tool for research consolidation, it is emblematic of the field’s maturity and its capacity to contribute meaningfully to both scientific discourse and societal outcomes in sport, health, and performance.

Building on the foundational studies described above, a systematic overview [21] summarized 30 sport psychology meta-analyses published between 1983 and 2021, spanning 16 psychological constructs. While the synthesis received constructive critique [28], it offered valuable insight: constructs hypothesized to enhance performance typically showed moderate effects, while those expected to impair performance demonstrated smaller, though statistically significant, associations. Since that review, the field has expanded rapidly, with a substantial number of new meta-analyses published across a broader range of psychological variables and performance outcomes, even by the same research group [29,30]. The volume and diversity of these newer reviews, particularly those emerging since 2020, have created both an opportunity and a need for a more comprehensive mapping of the evidence base [31].

A scoping review is therefore warranted to capture and organize this expanding body of research. The proliferation of meta-analyses examining constructs such as mindfulness, mental practice, emotional intelligence, confidence, and neurofeedback training has resulted in a complex and fragmented evidence landscape. While individual meta-analyses provide detailed quantitative insight into specific questions, the sheer number of overlapping and conceptually related syntheses now makes it difficult to discern the broader structure of knowledge in the field. A scoping review offers a systematic means of charting this terrain—identifying areas of concentration, redundancy, and inconsistency, while also highlighting underexplored topics. This broader synthesis provides a panoramic view of the evolution of sport psychology’s evidence base, supporting the development of more coherent theoretical frameworks and guiding future research priorities.

Further meta-analytic computation is not required at this stage. Many constructs have already been analyzed repeatedly, often drawing on similar primary studies, and additional aggregation would add little conceptual value. The strength of the current approach lies instead in synthesizing across existing quantitative reviews—collating and contextualizing their scope, methods, and findings to reveal patterns that are not visible within any single analysis. By mapping what has been studied, how it has been studied, and where evidence remains sparse, this scoping review provides an essential meta-level synthesis that integrates decades of quantitative research and identifies clear directions for future systematic reviews, empirical studies, and applied practice.

1.2. Purpose

The purpose of this review is to systematically map all published meta-analyses that examine psychological constructs in relation to sport performance. Extending our earlier synthesis of 30 meta-analyses [21], this study provides a substantially updated overview of the evidence base. Following the PRISMA-ScR framework [32], the review focuses on describing the breadth, methodological characteristics, and temporal trends of existing work rather than aggregating effect sizes or ranking constructs. By cataloging the scope of topics, research designs, and performance measures addressed across 73 meta-analyses, the review offers a resource to identify well-studied areas, highlight methodological gaps, and inform priorities for future quantitative synthesis and theory-driven investigation.

2. Materials and Methods

This review followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) guidelines [32], which are designed to map the scope and characteristics of research rather than statistically combine findings, as is done in traditional meta-analyses. This review was deliberately designed as a scoping review rather than a meta-analysis. In line with the PRISMA-ScR framework, the goal is to map and describe the breadth and characteristics of existing meta-analytic research in sport psychology, not to statistically aggregate or evaluate the quality of individual effect sizes. Because the purpose of a scoping review is to describe evidence coverage, we did not use quantitative synthesis, publication-bias testing, or heterogeneity statistics (e.g., I2); such analyses are outside the remit of PRISMA-ScR reviews. The completed PRISMA checklist is provided in Supplementary Table S1.

In terms of ethics, as this review synthesized previously published studies, it does not require new data collection or ethical approval. All included meta-analyses were based on primary studies that had already received ethical clearance from their respective institutional review boards. Rather than aggregating findings, the review uses a selective thematic summary of representative constructs to illustrate broader methodological trends while maintaining a comprehensive descriptive catalog of the literature.

The review was registered in PROSPERO (CRD420250653207).

2.1. Eligibility Criteria

The eligibility criteria for this review mirrored those used in Lochbaum et al. [21]. Meta-analyses were included if they were published in a peer-reviewed journal, examined a sport psychology construct, involved samples in which the majority of participants were described as athletes, and included meta-analytic data linking the psychological construct to sport performance. For the purposes of this review, athletes were defined as individuals formally engaged in organized sport or competitive training, from youth to elite levels. This operationalization distinguishes athletes from general exercisers or participants in non-competitive physical activity.

However, this review applied more stringent scrutiny to participant descriptions and the operationalization of sport performance outcomes. As a result, meta-analyses were excluded if they compared athletes to non-athletes as the primary focus, included when we could ascertain a number of included studies with participants described as children not engaged in youth sport, or assessed outcomes not directly tied to sport performance such as cognitive measures. Although the search was conducted in English, no formal English-language restriction was imposed.

2.2. Search Sources and Strategy

The lead author conducted the entire search and shared findings with the second author in email communications since June of 2023. The search process encompassed a number of iterations with most from published articles or databases. In summary, the origins started with a conference presentation [33] that led to Lochbaum and colleagues [21]. The search restarted with the lead author handsearching in June 2023, re-examining the 30 meta-analyses found in Lochbaum et al. [21], tapping into personal knowledge (i.e., lead author’s publications and notes from past work [34]), reading Holgado et al.’s [35] reference list. Then with a formal database search, the first author conducted searches in the first two weeks of March 2025 in EBSCOhost (APA PsychArticles, APA PsychInfo, ERIC, Medline, Psychology and Behavioral Science Collection, SPORTDiscus with Full Text), and WOS databases (Web of Science Core Collection 1900-present, Social Science Citation Index 1900-present, Emerging Sources Citation Index 2005-present, Medline). Since the formal search, Google Scholar alerts programed to find meta-analyses in sport psychology were reviewed while the manuscript was being written and revised.

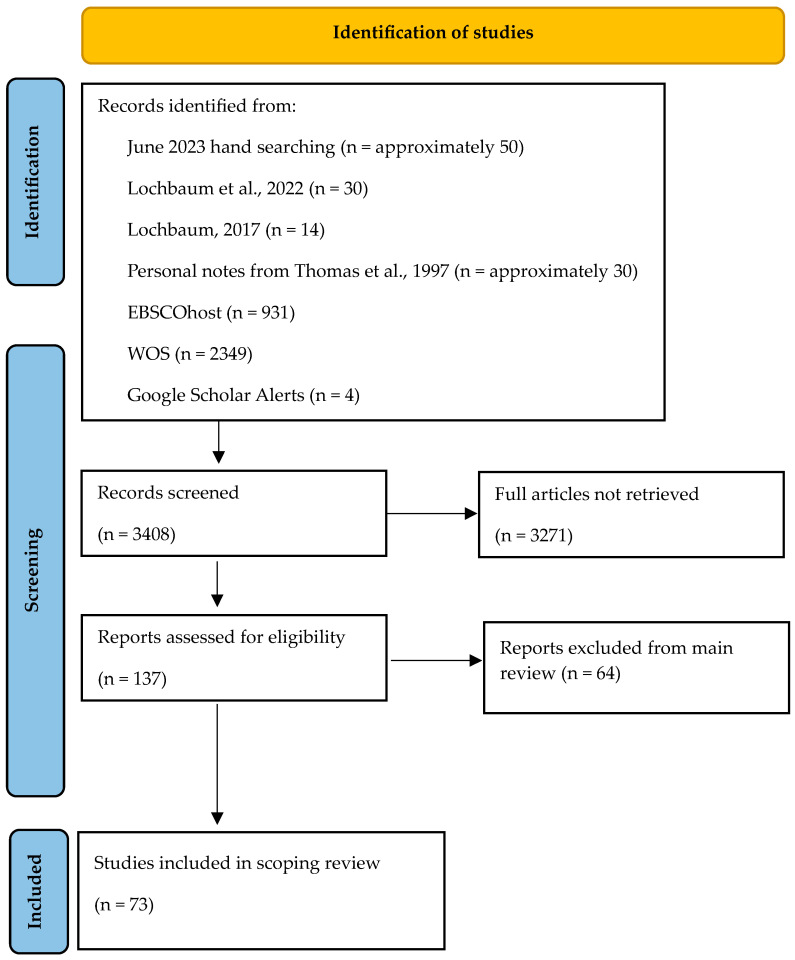

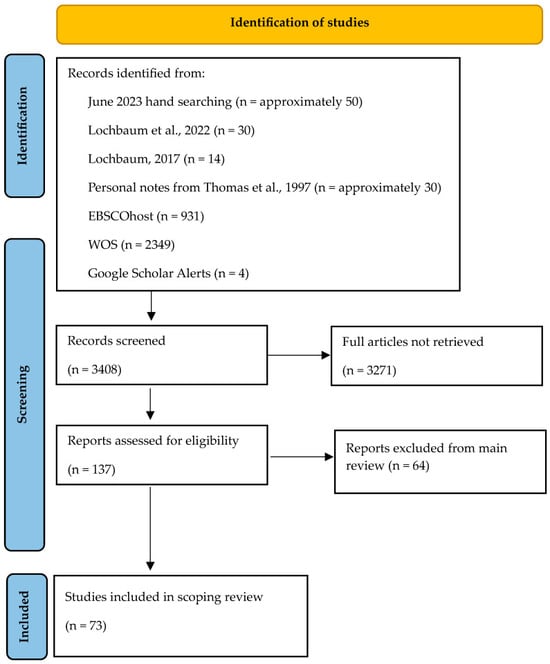

Within EBSCOhost (n = 931) and WOS (n = 2349), the following broad search was used with the goal of finding published sport psychology with performance data meta-analyses: (sport performance or competitive sport) AND (meta-analysis or meta analysis). Records were read from each search and notes compiled resulting in the 137 meta-analyses downloaded. Nearly all included meta-analyses were located in EBSCOhost and WOS in the March 2025 searches and within Lochbaum et al. [21]. Included articles found in Google Scholar alerts are also available now (searched to verify September 2025) in EBSCOhost and WOS. The search process is detailed in Figure 1. Details pertaining where each study was found are located in Table S2. The list of excluded meta-analyses is available from the lead author.

Figure 1.

Search process flow diagram [21,33,34].

2.3. Data Items Retrieved

The following information was extracted from each meta-analysis: search result(s) (i.e., where found), APA 7th edition reference (from https://www.crossref.org/, EBSCOhost, WOS, or https://scholar.google.com/, 15 March 2025), country of all authors, topic, summary effect size statistic, manuscript stated purpose, number of studies, number of participants if provided, description of the sample, description of sport performance measure(s), most succinct author stated results, and author stated conclusion. Most of the stated results and conclusions came directly from the abstracts. When performance was one of many outcomes, the results and conclusions were located in the results section, summary tables, and discussion section.

3. Results

3.1. Summary Characteristics

A wide variety of topics were meta-analyzed with some meta-analyses examining more than one topic. Based on the publication year, the majority were published in the last decade (n = 49) compared to past decades: 1980s (n = 1), 1990s (n = 3), 2000s (n = 5), and 2010s (n = 15). From the titles and data retrieving, at least 40 topics are found within the 73 meta-analyses. The interest in conducting and publishing appears global. The countries of attributed to authors came from the following continents and countries: Africa: South Africa; Asia: China, Israel, Japan, Korea (Republic of Korea), Malaysia, Taiwan, Turkey; Europe: Austria. Belgium, Czech Republic, France, Germany, Greece, Ireland, Italy, The Netherlands, Poland, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, UK; North America: Canada, Costa Rica, Grenada, USA; Oceania: Australia, New Zealand; and South America: Chile. Although this demonstrates wide international engagement, first author affiliations originated from Europe and North America were more evident, indicating that the evidence base remains weighted toward Western contexts.

The main sport psychology variables or topics are found in Table 1. Mental practice, achievement goals, anxiety, confidence, cohesion, mental fatigue, mindfulness, and POMS account for 32 the included meta-analyses. All of the included mental practice meta-analyses were published since 2020. Table 2 details the questions asked that is relationship between questions, effects of questions, and those reporting mean difference, ability to discriminate, influence of research questions and statistics were asked [20,29,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105,106]. A few meta-analyses analyzed more than one question with one providing data on many different constructs. Most of the study samples were a mix of athlete levels (see Appendix A). As with the mix of samples, measures of sport performance varied greatly from one meta-analysis to another. No one metric can account for the variety and specifics (see Appendix A).

Table 1.

Topics represented in the sport psychology and sport performance meta-analyses included in the main review.

Table 2.

Study reference, year published, main topic, and stated purpose for meta-analyses meeting all inclusion criteria (n = 73) listed in alphabetical order by topic.

3.2. Individual Study Data

Table 3, Table 4 and Table 5 provide summary data for the 73 meta-analyses that met all inclusion criteria. For readers unfamiliar with typical effect size metrics in sport psychology, most meta-analyses report either correlation coefficients or standardized mean differences, such as Cohen’s d or Hedges’ g. While the interpretive thresholds for these metrics have been debated particularly the arbitrary nature of benchmarks in psychological research [107], commonly accepted guidelines in the social sciences classify correlations of 0.10 as small, 0.30 as medium, and 0.50 as large. For standardized mean differences, values of 0.20, 0.50, and 0.80 are typically used to represent small, medium, and large effects, respectively.

Table 3.

Summary of ‘relationship between’ meta-analyses.

Table 4.

Summary of effects of meta-analyses.

Table 5.

Summary of meta-analyses with a variety of research questions not fitting into relationship between or effects of questions.

Table 3 summarizes the correlational findings and Table S3 contains more result specifics. Nearly all studies included 95% confidence intervals alongside the central effect size estimates. Of the reported findings, only one effect size, by Carron et al. [52], reached the conventional threshold for a large effect, though it was presented as a standard mean difference despite the analysis involving correlational data. Readers are strongly encouraged to consult the full meta-analyses for accurate interpretation, as many include bias-corrected estimates, true effect size calculations, and moderator analyses that offer deeper insight into the practical significance of findings. One recently published meta-analysis [95] addressed multiple psychological factors simultaneously. Ayranci and Aydin [95] provided an umbrella-style meta-analysis that included several psychological constructs such as motivation, confidence, self-efficacy, and emotional intelligence. We include this note here to acknowledge the overlap with other construct specific meta-analyses, though their broader scope and their search time frame 2014–2024 made the study difficult to classify as well as the initial reporting of the results using the correlation as the main metric but then reporting the single constructs (e.g., motivation, confidence) in Cohen’s d. Given the mean of the all the psychological constructs was reported in r, Ayranci and Aydin [95] is included in Table 3.

Table 4 summarizes findings from meta-analyses that examined the effects of interventions or psychological manipulations on sport performance outcomes with Table S4 containing more in-depth results. Compared to correlational studies, these reviews typically involved greater methodological complexity such as pre–post designs, active versus control comparisons, or intervention follow-ups which helps explain the wider range of observed effect sizes.

A few broad patterns emerge. Interventions such as biofeedback, mindfulness, process-goal setting, and psychological skills training often produced effects in the medium-to-large range, suggesting potential practical value for applied sport settings. In contrast, effects for constructs like ego-oriented goals, short-term breathing manipulations, and certain mental fatigue outcomes were negligible or inconsistent. These results highlight how both intervention design and the type of performance outcome measured could influence reported effectiveness.

Readers should note that these summaries cannot capture the full statistical detail. Many of the included reviews reported bias-corrected estimates, moderator analyses, or follow-up effects that provide richer context. Accordingly, we encourage readers to consult the original meta-analyses for deeper interpretation, particularly where intervention protocols or outcome definitions may affect applicability to specific sports or athlete populations.

Table 5 presents individual study details for 10 meta-analyses that addressed a range of research questions, including group differences, influence of variables, discriminative ability, and the magnitude of associations between sport psychology constructs and sport performance. Table S5 contains more detailed results. Of particular note, it was especially challenging to extract and condense the appropriate results for Weiß et al. [55], given the complexity of their analysis. Readers interested in those findings are encouraged to consult Table 5 of Weiß and colleagues’ original publication, which provides moderator analyses exploring the effects of different color types on performance outcomes.

As found in Table 5, although only ten meta-analyses are summarized, a few patterns emerge that highlight the diversity of research questions in sport psychology. Unlike the more commonly studied relationships (e.g., confidence–performance) or intervention effects (e.g., mental practice), these reviews explore constructs that do not fit neatly into those categories. Instead, they examine questions such as whether performance varies by goal orientation, emotional states, perceptual strategies, or attributional style. Further, the distribution of effect sizes is telling. Many findings fall into the “less than small” or “small” range, suggesting that certain popular constructs (e.g., performance-avoidance goals, mood states like anger and fatigue, or attributional explanations) may hold limited practical significance for predicting sport performance. By contrast, a handful of results rise to medium or large effects, notably in the case of the quiet eye literature, which consistently discriminates between successful and unsuccessful performances. Similarly, certain aspects of color and achievement goals show moderate associations, though these appear context dependent.

Overall, Table 5 underscores two points: first, that not all sport psychology constructs carry equal performance relevance, and second, that some areas (such as perceptual-attentional mechanisms like the quiet eye) demonstrate stronger and more consistent links with performance than many motivational or affective variables.

3.3. Interpretation and Potential Uses of the Results

Table 6, Table 7 and Table 8 focus on three frequently examined sport psychology topics: confidence, mental practice, and anxiety. Each has been the focus of multiple meta-analyses, enabling comparisons across time, methods, and inclusion criteria. For instance, self-confidence has been the focus of multiple meta-analyses. Four independent meta-analyses on confidence two published in 2003 [41,42] and two decades later [56,57] demonstrate striking consistency, despite differences in inclusion criteria and periods covered. As shown in Table 6, effect sizes range narrowly from 0.25 to 0.30. This stability suggests that while confidence is positively associated with performance, the effects are modest. As such, inflated claims that boosting confidence dramatically enhances sport performance should be treated with skepticism.

Table 6.

Confidence meta-analyses.

Table 7.

Mental practice meta-analyses.

Table 8.

Anxiety and performance meta-analyses.

In contrast to confidence, the literature on mental practice presents more variation in both scope and interpretation. In contrast to the consistency found in confidence studies, meta-analyses on mental practice show wider variability in design, performance outcomes included, and conclusions (Table 7). Some reviews are broad in scope [69], while others focus narrowly on tennis [73]. The effects range from small to large depending on the outcome and whether mental practice was combined with physical training. Collectively, these findings reinforce the importance of context and raise questions about how mental practice is implemented and evaluated across sport domains.

Anxiety-performance relationships have long been of considerable interest in competitive sport. As found in Table 8, the first two meta-analyses were published in the 1990s [39,40] and the subsequent two meta-analyses published in 2003 [41,42]. Three of the meta-analyses suggest a negligible or unreliable relationship with performance. An exception is Jokela and Hanin [40], whose findings support the IZOF model. For the 2003 meta-analyses, the data in Table 8 represent cognitive anxiety and for the Woodman and Hardy meta-analysis the data reported in the table are from their ‘assuming 0 for missing correlations’ results. It is interesting that the last year for studies included in the four meta-analyses making up our cumulative knowledge of anxiety and sport performance was in 1998. Is there a need for an updated anxiety and sport performance meta-analysis or are we as researchers and practitioners to eliminate anxiety measurement from our research? Any quick search of the sport psychology and anxiety literature since 1998 clearly shows as a field we continue to research competitive anxiety and sport performance. Why would this research continue unless researched within the IZOF framework?

Beyond overall effects, many meta-analyses attempt to explain variability in findings through moderator analyses. However, these efforts vary in theoretical justification, statistical power, and reporting transparency. Suffice to say that moderators are a contentious topic. In Table 9, we present selected examples, as there are hundreds found in the 71 meta-analyses, that illustrate both the potential value and common limitations of moderator analysis in sport psychology research. The first example [75] shows differences by the performance measure classification, objective or subjective, for the mental toughness and performance relationship. With nearly twice the average mean effect, expectations of the value of mental toughness with objective performance measures should be dampened. Toth and colleagues [72] demonstrated a moderate mental practice and performance relationship that could and would if accurate impact the expected or hoped mental practice benefits on performance. If one is hoping for distance or time improvements, those are at best small whereas performance categorized as “other” is medium in meaningfulness. The other two examples point to different categorical moderators, goal type and sex of sample. What we learn from Williamson and colleagues [63] is that there are vastly different effect size values across process, performance, and outcome goals. Last, sex of sample across decades of studies appears to moderate the confidence-performance relationship [42,56]. Though lacking theory or any explanation, this result seems worthy of future research or do practitioners simply tell female athletes their confidence does not matter to their performances?

Table 9.

Study, topic, main result, and moderated result for selected meta-analyses.

4. Discussion

The aim of this PRISMA-ScR review was to map the full range of meta-analyses examining psychological constructs in relation to sport performance. Seventy-three eligible reviews were identified, reflecting the rapid expansion and increasing methodological sophistication in Sport Psychology. Collectively, these reviews span more than 40 constructs, diverse athlete populations, and multiple performance outcomes.

Three broad patterns emerged. First is that the field has diversified dramatically since 2020, producing a wide range of theoretical perspectives, constructs, and analytic approaches. This heterogeneity is a defining feature of a maturing discipline: it reveals the multiple ways in which researchers have sought to understand psychology–performance relationship. Second, only a minority of meta-analyses have isolated specific athlete populations (e.g., elite performers) or focused exclusively on objective performance outcomes, meaning that practical applicability can vary across reviews. Third, the level of methodological detail reported across studies such as quality appraisal, bias assessment, and operational definitions of performance differs considerably, offering insight into how reporting conventions are evolving within the field. Rather than viewing these patterns as shortcomings, we interpret them as evidence of the field’s developmental breadth and as indicators of where conceptual and methodological alignment could yield greater cumulative understanding. The following section outlines realistic priorities for achieving such integration.

The scale of the reviewed meta-analytic literature is impressive but also daunting. What became apparent from our review efforts was not just the breadth of meta-analytic work, but also the fragmented nature of the evidence base. Most of the meta-analyses adopt broad inclusion criteria, use inconsistent terminology, and focus on a wide variety of sport performance measures. There is limited coherence across studies in terms of how they define target populations (e.g., recreational vs. elite athletes), how they conceptualize performance (e.g., objective measures like time or score versus subjective self-reports), and how rigorously they report methodological variables such as study quality or bias. This heterogeneity in reporting makes synthesis difficult and impedes the field’s ability to generate cumulative insights that inform practice or policy.

Despite the growth in the number of meta-analyses, relatively few are designed with a clear focus on athletes as a distinct population or on performance outcomes that are directly relevant to sport. Instead, many reviews aggregate across heterogeneous samples, contexts, and constructs. While some include moderator analyses that attempt to isolate athlete-level effects or differentiate between objective and subjective performance measures, these are inconsistently applied and often underpowered. Attempting to extract such information across all meta-analyses quickly became impractical. Moving forward, we see several avenues for progress:

- Population-Specific Meta-Analyses: Future reviews should aim to isolate athlete populations more carefully, ideally differentiating by competitive level, sport type, gender, age, or training history. Stratifying samples in this way would enhance the ecological validity of findings and better reflect the diversity within sport. Without such granularity, it becomes difficult to draw conclusions that are meaningfully applicable to specific athlete groups or contexts.

- Clearer Operational Definitions of Performance: Many reviews suffer from vague or inconsistent definitions of what constitutes ‘performance.’ Greater attention should be given to clarifying whether performance is measured through objective (e.g., competition results, biometric data) or subjective (e.g., coach ratings, self-report) means. Standardizing definitions and explicitly stating the measurement type would allow for more valid comparisons across studies and more direct translation into applied settings.

- More nuanced moderator-focused reviews: By ‘more nuanced’, we mean analyses that move beyond basic demographic splits (e.g., gender or age) to explore interaction effects between multiple contextual variables such as competition level, sport type, intervention duration, or delivery format. These nuanced moderator analyses could help determine which interventions work best, for whom, and under what circumstances and ultimately bring us closer to the goal of tailored, context-specific guidance for applied practice. Achieving this will require both more detailed primary study reporting and a meta-analytic culture that prioritizes thoughtful moderator planning over sheer volume of included studies.

- Thematic Synthesis: Beyond aggregating studies focused on single interventions, the field would benefit from reviews that integrate evidence around broader psychological constructs such as self-regulation, motivation, or emotion regulation. These thematic syntheses could reveal underlying mechanisms across interventions and promote a more theory-driven understanding of sport psychology’s contribution to performance and well-being.

- Improved Reporting Standards: The consistent use of evidence synthesis guidelines—such as PRISMA, AMSTAR, and GRADE—can help ensure transparency and reproducibility. In particular, reporting of moderators, risk of bias, and heterogeneity should become standard practice. Doing so would not only enhance interpretability and comparability across meta-analyses but also elevate the overall methodological rigor in the field.

- Societal Value and Employability: The volume of research in sport psychology could be better leveraged to demonstrate societal value and impact. Much of the evidence generated by meta-analyses—on performance, motivation, well-being, or behavior change—has relevance well beyond elite sport. Sport psychology graduates are equipped with analytical thinking, communication skills, and an understanding of human performance under pressure. These capabilities are valuable in sectors ranging from education and health to business and the military. Communicating the evidence base clearly, embedding findings into teaching curricula, and linking research to professional training and continuing professional development (CPD) can enhance both employability and the visibility of sport psychology as a discipline that serves broader societal needs.

4.1. De-Limitations and Limitations

Despite the comprehensive nature of this scoping review, several limitations should be acknowledged. Some reflect the boundaries intentionally set by design, whereas others became apparent during the review process. There were planned delimitations. The review followed PRISMA-ScR guidance, which prioritizes breadth of coverage over statistical synthesis. Accordingly, we did not perform a second-order meta-analysis, aggregate effect sizes, or conduct formal quality appraisal. These choices were deliberate to preserve inclusivity and transparency across a large and methodologically diverse evidence base. The search strategy, while extensive and multi-database (EBSCOhost, Web of Science, and Google Scholar alerts), was conducted in English, which may have introduced a language bias and excluded non-indexed sources. The inclusion criteria also focused specifically on meta-analyses that linked defined sport-psychology constructs to performance outcomes; therefore, studies examining related but indirect variables (e.g., cognitive or physiological markers) were not captured.

Concerning unplanned limitations, during synthesis it became clear that several features of the existing literature limited comparability in ways that were not fully evident at the outset. Many meta-analyses lacked consistent reporting of sample characteristics, effect-size metrics, or performance definitions, making it difficult to align data across studies even descriptively. In addition, a small number of eligible reviews had incomplete or ambiguous methodological information that could not be verified from the published record. Finally, the pace of new publications in 2024–2025 meant that several meta-analyses appeared during the writing phase, and although we incorporated as many as possible, the evidence base continues to evolve rapidly. Collectively, these limitations highlight both the strengths and constraints of scoping review methodology. They underscore the need for more standardized reporting and for dynamic, updateable databases to maintain currency as the field expands.

4.2. Immediate Next Steps

The volume of existing reviews is now sufficient to inform theory and practice; the greater challenge lies in integrating and coordinating what is already known. For this reason, we deliberately conducted a scoping review rather than another meta-analysis; we intentionally set out with the aim to map the extent and characteristics of existing evidence, expose overlaps and inconsistencies, and identify opportunities for more strategic synthesis. The results of this review highlight the need for greater coordination in how evidence is generated and shared across sport psychology. Two immediate actions could strengthen the field’s cumulative progress.

The first is to suggest establishing collaborative, open-access databases of primary studies would enhance transparency, reduce duplication, and enable large-scale moderator and bias analyses. Shared datasets would allow consistent tagging of variables such as intervention type, participant characteristics, and performance outcomes, improving comparability across future meta-analyses. Such infrastructure would also create valuable opportunities for early-career researchers to engage with high-quality data and contribute to cumulative, theory-driven science. Second, developing a Delphi-based consensus process involving journal editors, professional associations, and researchers from different regions and disciplines could help set priorities for future evidence synthesis. A structured Delphi study could identify under-researched topics, clarify reporting standards, and promote consistent definitions of performance and athlete populations. This collaborative process would ensure that future reviews address both established and emerging areas, supporting a more integrated and inclusive research agenda, e.g., refs. [108,109,110]. In short, the priority for future work is therefore not producing more meta-analyses, but improving how findings are connected, compared, and communicated. Coordinated use of shared databases, consensus frameworks, and consistent reporting standards will deliver greater progress than the continued proliferation of isolated reviews.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, this PRISMA-ScR scoping review mapped 73 meta-analyses examining psychological constructs in relation to sport performance, illustrating both the breadth and methodological diversity of the field. The rapid growth of meta-analytic research reflects the maturity and international scope of sport psychology, with contributions spanning multiple theoretical traditions, performance domains, and athlete populations. Rather than viewing this diversity as a limitation, it should be seen as evidence of a dynamic and expanding discipline that now stands ready for greater synthesis and coordination.

The next stage of progress lies not in producing more isolated meta-analyses, but in integrating and harmonizing the substantial body of evidence that already exists. Establishing shared reporting standards, open-access databases, and collaborative consensus processes, for example, Delphi initiatives would facilitate methodological consistency, reduce duplication, and enhance the cumulative value of future research. Professional and scientific organizations, including the International Society of Sport Psychology (ISSP), national sport psychology associations, and journal editorial boards, could play a leading role in supporting such Delphi-based collaborations. By endorsing structured consensus exercises, these bodies can help align definitions, prioritize research questions, and encourage sustainable, collective approaches to evidence synthesis. By focusing on conceptual alignment, transparency, and collaborative infrastructure, sport psychology can move from mapping diversity to building coherence, generating an evidence base that is both scientifically robust and practically applicable to performance and well-being across contexts.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/sports13120420/s1, Table S1: Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) Checklist; Table S2: Included articles search source results; Table S3: Study, topic, and results expressed as r [95% confidence interval]; Table S4: Study, topic, and results for effects of meta-analyses; Table S5: Study, topic, and results for all other meta-analyses.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.L. and A.M.L.; methodology, M.L.; formal analysis, M.L.; writing—original draft preparation, M.L. AND A.M.L.; writing—review and editing, M.L. and A.M.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All data are found within the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Included studies sample and sport performance measures.

Table A1.

Included studies sample and sport performance measures.

| Authors | Participants | Athletes | Measures |

|---|---|---|---|

| Allen et al. [102] | Athletes, club to elite | Mix | Real-world athletic outcomes |

| Ayranci & Aydin [95] | Athletes, elite to non-elite | Mix | Not stated but most likely mix of objective and subjective based on the single studies |

| Baker et al. [96] | Athletes, regional to elite | Mix | Variety of performance outcomes |

| Beedie et al. [90] | Athletes, non-elite to elite | Mix | Sport performance representing level of achievement and level of performance. |

| Brown & Fletcher [65] | Athletes, local, regional, national, or international | Mix | Variety of sport outcomes |

| Bühlmayer et al. [77] | Healthy sportive participants | Elite, recreational | Shooting and dart throwing |

| Carron et al. [52] | Athletes, youth to professional | Mix | Performance outcomes from interactive and coactive teams |

| Castaño et al. [53] | Athletes, reference suggest a mix | Mix | Vaguely described, win/loss ratio a stated example |

| Clemente et al. [66] | Athletes, youth, college, semi-professional | Mix | Tactical behavior in small-sided games |

| Craft et al. [41] | Athletes (predominantly) with college PE students | Mix | Variety of athletic performance outcomes |

| Deng et al. [73] | Athletes, novice to national level | Mix | Tennis serve and return measures |

| Filho et al. [47] | Experienced athletes and novices | Mix | Objective self-paced performance (e.g., golf putting, archery) |

| Filho et al. [51] | Athletes, recreational, interscholastic, collegiate, and professional | Mix | Objective and subjective sport measures |

| Habay et al. [68] | Athletes, university students to elite | Mix | Endurance performance measures including time trials and fitness tests |

| Harris et al. [62] | Athletes and gamers | Mix | Sport and computer gaming performance |

| Hatzigeorgiadis et al. [103] | Students, beginning athletes, experienced athletes | Mix | Variety of objective athletic measures |

| Hill et al. [87] | Athletes and some sport science students | Mix | Individual sport outcomes |

| Hsieh et al. [75] | Athletes, non-athletes, and recreational athletes | Mix | Subjective, objective athletic performance |

| Hunte et al. [99] | Athletes (recreational to trained for the motor results) | Mix | Objective sport performance measures (e.g., basketball freethrows) and one graded exercise test |

| Ivarsson et al. [38] | Athletes, adolescents | Youth, adolescents | Progression (e.g., higher level team), football statistics (e.g., goals, assists) |

| Jamieson [64] | Athletes, professionals from a variety of sports | Professional, collegiate | Game outcome |

| Jekauc et al. [57] | Athletes, youth to adult | Mix | Variety of objective, subjective performance measures |

| Jokela & Hanin [40] | Athletes, non-elite to elite | Mix | Criterion referenced, self-referenced, or subjectively rated sport performance |

| Kämpfe et al. [81] | Athletes, appears recreational and volunteer college students | Mix | Performance measures across a few sports and physical measures |

| Kim et al. [94] | Athletes, middle school to adults | Mix | Archery performance? |

| Kim et al. [88] | Athletes, variety of levels does not appear to include elite | Mix | Mix of objective measures, race time most frequent, only one non-sport (Yo-Yo test) |

| Kleine [39] | Athletes predominantly with general students in PE | Mix | Performance in many sports operationalized in multiple ways |

| Kopp & Jekauc [61] | Athletes, amateur to elite | Mix | Objective and subjective sport measures and physical parameters (e.g., maximal voluntary contraction) |

| Laborde et al. [48] | Athletes and active exercises | Mix | Objective sport specific and physical performance measures |

| Lebeau et al. [97] | Athletes, experts and non-experts | Mix | Self- and externally paced successful and unsuccessful sport performances |

| Lehrer et al. [46] | Athletes, difficult to find level | Mix, most likely | Athletic/artistic/performance |

| Li et al. [44] | Healthy > 18 years of age, low and high skill sprinters | Mix | Track sprinting |

| Li et al. [50] | Athletes, grades 4 to 12 | Youth, adolescent | Objective psychomotor and game performance |

| Lindsey et al. [70] | Healthy volunteers ranging from novices to trained athletes | Mix | Sport-specific motor skills |

| Liu et al. [69] | Athletes of all ages no health requirement | Mix | Objective and subjective sport performance and physical performance measures |

| Lochbaum & Gottardy [37] | Athletes and non-athletes | Mix | Variety of objective and subjective sport measures including the PACER |

| Lochbaum & Sisneros [29] | Athletes, youth to elite | Mix | Variety of objective, subjective performance measures |

| Lochbaum et al. 2022 [56] | Athletes, youth to elite | Mix | Variety of objective, subjective performance measures |

| Lochbaum et al. [91] | Athletes, youth to elite | Mix | Variety of objective, subjective performance measures |

| Lochbaum et al. [100] | Athletes, youth to elite | Mix | Variety of objective, subjective performance measures |

| Low et al. [93] | Athletes, novice to elite | Mix (police officers not included) | Mostly self-paced skills in several sport contexts |

| Makaruk et al. [43] | Athletes, skilled and recreationally trained jumpers or untrained volunteers | Mix | Jumping performance |

| Maudrich et al. [79] | Healthy with at least 2 years of sport participation | Mix | Sports performance domains from many sports |

| Moritz et al. [101] | Athletes, non-athletes, and “other” category | Mix | Subjective and objective sport performance |

| Garzón Mosquera & Vargas [74] | Athletes, including professionals | Mix | Objective measures (e.g., golf performance, netball shooting) |

| Mossman et al. [45] | Participants in a sport or exercise setting distinct from physical education settings | Mix | Performance and achievement measures |

| Mullen & Riordan [13] | Athletes, reference titles suggests youths to college | Mix | Attributions in reference to real sport task |

| Murdoch et al. [104] | Athletes (defined as an individual who is behaviorally engaged in sport) | Mix | Objective and subjective sport measures |

| Nicholls et al. [58] | Vast majority late adolescent or young adult sport performers | Mix | Objective and subjective sport measures |

| Olsson et al. [49] | Athletes, club to international in track and field or swimming | Mix | Objective competition performance compared to personal best |

| Peperkoorn et al. [54] | Athletes, elite from boxing, taekwondo, and wrestling | Elite | Objective outcome, won/lose |

| Ptáček et al. [78] | Athletes, vague in description | Mix, most likely | Objective (sport and physical (e.g., strength) and subjective performance measures |

| Reinebo et al. [95] | Athletes competing at a regional or university level or higher. | Mix | Subjective, objective athletic performance |

| Rowley et al. [89] | Athletes, all levels | Mix | Sport performance such as personal best, ranking, selection for team, winning/losing, or subjective assessment. |

| Rupprectht et al. [92] | Athletes, 70% subelite and elite | Mix | Variety of performance outcomes |

| Shyamali Kaushalya et al. [80] | Healthy adults including trained athletes | Mix | Time to exhaustion, endurance time trial, and sprint performance |

| Si et al. [76] | Athletes, college to elite | College, elite | Objective, darts and appears a subjective questionnaire |

| Silva et al. [59] | Athletes, youth teams (regional to elite) | Mix | Objective and subject volleyball decision-making measures |

| Simonsmeier [71] | Athletes, novice to professional | Mix | Sport specific outcomes |

| Sirnik et al. [98] | Athletes, beginners to elite | Mix | Quiet eye duration for made basketball free-throw and jumpshots |

| Skalski et al. [84] | Athletes, defined as national, international-level | Elite | Objective with judo, archery, shooting most common; appears to include other performance variables (e.g., attention) |

| Conejero Suárez et al. [60] | Athletes, youth to 1st division | Mix | Objective and subject volleyball decision-making measures |

| Sun et al. [67] | Athletes, recreational to elite | Mix | Sport-specific outcomes from 6 sports |

| Terry et al. [82] | Athletes and exercisers | Mix | Objective performance in sports and physical activities |

| Toth [72] | Expert performers to novices | Mix | Performance quantified according to distance (e.g., distance from the target), time (e.g., time to complete a task), or other (e.g., idiosyncratic scoring system). |

| Van Yperen et al. [36] | Participants in sport domain | Mix, most likely | Performance on particular exercises, ranking in tournaments, outcomes of competitions, and assessments by coaches or trainers |

| Weiß et al. [55] | Participants in an actual sport/exercise setting, judging pictures/videos/real-life actions depicting a sport/exercise setting, imagining to be in a sport/exercise setting, or in virtual competition. | Mix | Variety of sport performance measures |

| Williamson et al. [63] | Athletes and non-athletes | Mix | Performance in darts, golf, basketball, volleyball, swimming, bowling, football, running, tennis, table-tennis, boxing |

| Woodman & Hardy [42] | Athletes, youth to at least semi-professional based on reference list | Mix | Variety of sport performance measures |

| Xiang et al. [83] | Athletes, recreational to elite | Mix | Performance in self paced sports including dance |

| Yang et al. [88] | Athletes, youth to elite | Mix | Objective and subjective sport measures |

| Yu et al. [85] | Athletes, including elite, and some novices | Mix | Objective with majority being precision movements (e.g., archery, shooting, dart throwing, golf putting) |

| Zhu et al. [86] | Athletes, recreational to elite | Mix | Task-specific response accuracy, response time, or on-court transfer RA/performance RT |

References

- Koch, C.F. Die Gymnastik aus dem Gesichtspunkte der Diatetik und Psychologie [Callisthenics from the Viewpoint of Dietetics and Psychology]; Creutz: Magdeburg, Germany, 1830. [Google Scholar]

- Terry, P.C. Applied Sport Psychology. In IAAP Handbook of Applied Psychol; Wiley-Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 2011; pp. 386–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terry, P.C.; Bertollo, M.; Filho, E. Advancements in mental skills training: An introduction. In Advancements in Mental Skills Training; Bertollo, M., Filho, E., Terry, P.C., Eds.; Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group: Abingdon, UK, 2021; pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chroni, S.A.; Abrahamsen, F. History of Sport, Exercise, and Performance Psychology in Europe. In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Psychology; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Granito, V.J. History of Sport, Exercise, and Performance Psychology in North America. In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Psychology; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Krane, V.; Whaley, D. Quiet competence: Writing women into the history of U. S. sport and exercise psychology. Sport Psychol. 2010, 18, 349–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroll, W.; Lewis, G. America’s first sport psychologist. Quest 1970, 13, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landers, D.M. Sport psychology: The formative years, 1950–1980. Sport Psychol. 1995, 9, 406–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, D.L. Women’s place in the history of sport psychology. Sport Psychol. 1995, 9, 418–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, D.L.; Reifsteck, E.J. History of exercise psychology. In Encyclopedia of Sport and Exercise Psychology; Eklund, R.C., Tenenbaum, G., Eds.; SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2014; pp. 340–345. [Google Scholar]

- Tissié, P. Observations physiologiques concernant un record velocipédique. Arch. Physiol. Norm. Pathol. 1894, 4, 823–837. [Google Scholar]

- Tissié, P. Psychologie de l’entrainement intensif. La Rev. Sci. 1894, 31, 481–493. [Google Scholar]

- de Coubertin, P. La psychologie du sport. La Rev. Des Deux Mondes 1900, 70, 161–179. [Google Scholar]

- Rudik, P.A. Fifty Years of Psychology of Sport in the USSR [translated by Dr. David G. Nichols]. Sov. Psychol. 1968, 7, 58–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryba, T.V.; Stambulova, N.B.; Wrisberg, C.A. The Russian origins of sport psychology: A translation of an early work of AC Puni. J. Appl. Sport Psychol. 2005, 17, 157–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triplett, N. The Dynamogenic Factors in Pacemaking and Competition. Am. J. Psychol. 1898, 9, 507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stroebe, W. The Truth About Triplett (1898), But Nobody Seems to Care. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2012, 7, 54–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feltz, D.L.; Landers, D.M. The Effects of Mental Practice on Motor Skill Learning and Performance: A Meta-analysis. J. Sport Psychol. 1983, 5, 25–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bond, C.F.; Titus, L.J. Social facilitation: A meta-analysis of 241 studies. Psychol. Bull. 1983, 94, 265–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullen, B.; Riordan, C.A. Self—Serving Attributions for Performance in Naturalistic Settings: A Meta—Analytic Review. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 1988, 18, 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lochbaum, M.; Stoner, E.; Hefner, T.; Cooper, S.; Lane, A.M.; Terry, P.C. Sport psychology and performance meta-analyses: A systematic review of the literature. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0263408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson, K. Report on certain enteric fever inoculation statistics. BMJ 1904, 3, 1243–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shannon, H. A statistical note on Karl Pearson’s 1904 meta-analysis. J. R. Soc. Med. 2016, 109, 310–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyers, A.W.; Whelan, J.P.; Murphy, S.M. Cognitive behavioral strategies in athletic performance enhancement. Prog. Behav. Modif. 1996, 30, 137–164. [Google Scholar]

- Whelan, J.P.; Meyers, A.W.; Berman, J.S. Cognitive-behavioral interventions for athletic performance enhancement. In Sport Psychology Intervention Research: Reviews and Issues. Symposium Presented at the American Psychological Association; Greenspan, M., Ed.; American Psychological Association: New Orleans, LA, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Deutsch, H. Contribution to the Psychology of Sport. Int. Z. Psychoanal. 1925, 11, 222–226. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, G.C. Win-loss causal attributions of little league players. Mouvement 1975, 7, 315–322. [Google Scholar]

- Hill, A.P. Comparisons and conversions: A methodological note and caution for meta-analysis in sport and exercise psychology. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2023, 45, 293–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lochbaum, M.; Sisneros, C. Situational and Dispositional Achievement Goals and Measures of Sport Performance: A Systematic Review with a Meta-Analysis. Sports 2024, 12, 299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lochbaum, M.; Sisneros, C. A Systematic Review with a Meta-Analysis of the Motivational Climate and Hedonic Well-Being Constructs: The Importance of the Athlete Level. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2024, 14, 976–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lochbaum, M. Sport psychology and performance outcomes—Breath of topics, insights to practitioners, and future directions. In Proceedings of the Presentation at the 18th Conference of Baltic Sport Science Society, Expanding Horizons in Sport Science and Innovation, Vytautas Magnus University, Kaunas, Lithuania, 28–30 April 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Straus, S.E. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lochbaum, M. Understanding the meaningfulness and potential impact of sports psychology on performance. In Proceedings of the Book of 8th International Scientific Conference on Kinesiology, Opatija, Croatia, 10–14 May 2017; University of Zagreb, Faculty of Kinesiology: Zagreb, Croatia, 2017; pp. 486–489. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, J.R.; Lochbaum, M.R.; Landers, D.M.; He, C. Planning significant and meaningful research in exercise science: Estimating sample size. Res. Q. Exerc. Sport 1997, 68, 33–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holgado, D.; Sanabria, D.; Vadillo, M.A.; Román-Caballero, R. Zapping the brain to enhance sport performance? An umbrella review of the effect of transcranial direct current stimulation on physical performance. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2024, 164, 105821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Yperen, N.W.; Blaga, M.; Postmes, T. A Meta-Analysis of Self-Reported Achievement Goals and Nonself-Report Performance across Three Achievement Domains (Work, Sports, and Education). PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e93594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lochbaum, M.; Gottardy, J. A meta-analytic review of the approach-avoidance achievement goals and performance relationships in the sport psychology literature. J. Sport Health Sci. 2015, 4, 164–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivarsson, A.; Kilhage-Persson, A.; Martindale, R.; Priestley, D.; Huijgen, B.; Ardern, C.; McCall, A. Psychological factors and future performance of football players: A systematic review with meta-analysis. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2020, 23, 415–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kleine, D. Anxiety and sport performance: A meta-analysis. Anxiety Res. 1990, 2, 113–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jokela, M.; Hanin, Y.L. Does the individual zones of optimal functioning model discriminate between successful and less successful athletes? A meta-analysis. J. Sports Sci. 1999, 17, 873–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craft, L.L.; Magyar, M.; Becker, B.J. The Relationship between the Competitive State Anxiety Inventory-2 and sport performance: A meta-analysis. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2003, 25, 44–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodman, T.; Hardy, L. The relative impact of cognitive anxiety and self-confidence upon sport performance: A meta-analysis. J. Sports Sci. 2003, 21, 443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makaruk, H.; Starzak, M.; Marak Porter, J. Influence of Attentional Manipulation on Jumping Performance: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Hum. Kinet. 2020, 75, 65–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Zhang, L.; Yue, X.; Memmert, D.; Zhang, Y. Effect of Attentional Focus on Sprint Performance: A Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 6254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mossman, L.H.; Slemp, G.R.; Lewis, K.J.; Colla, R.H.; O’Halloran, P. Autonomy support in sport and exercise settings: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. Rev. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2022, 17, 540–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehrer, P.; Kaur, K.; Sharma, A.; Shah, K.; Huseby, R.; Bhavsar, J.; Sgobba, P.; Zhang, Y. Heart Rate Variability Biofeedback Improves Emotional and Physical Health and Performance: A Systematic Review and Meta Analysis. Appl. Psychophysiol. Biofeedback 2020, 45, 109–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filho, E.; Dobersek, U.; Husselman, T.-A. The role of neural efficiency, transient hypofrontality and neural proficiency in optimal performance in self-paced sports: A meta-analytic review. Exp. Brain Res. 2021, 239, 1381–1393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laborde, S.; Zammit, N.; Iskra, M.; Mosley, E.; Borges, U.; Allen, M.S.; Javelle, F. The influence of breathing techniques on physical sport performance: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. Rev. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2022, 17, 1222–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsson, L.F.; Glandorf, H.L.; Black, J.F.; Jeggo, R.E.K.; Stanford, J.R.; Drew, K.L.; Madigan, D.J. A multi-sample examination of the relationship between athlete burnout and sport performance. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2025, 76, 102747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Olson, H.O.; Tereschenko, I.; Wang, A.; McCleery, J. Impact of coach education on coaching effectiveness in youth sport: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Sports Sci. Coach. 2024, 20, 340–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filho, E.; Dobersek, U.; Gershgoren, L.; Becker, B.; Tenenbaum, G. The cohesion-performance relationship in sport: A 10-year retrospective meta-analysis. Sport Sci. Health 2014, 10, 165–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carron, A.V.; Colman, M.M.; Wheeler, J.; Stevens, D. Cohesion and Performance in Sport: A meta-analysis. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2002, 24, 168–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castaño, N.; Watts, T.; Tekleab, A.G. A reexamination of the cohesion–performance relationship meta-analyses: A comprehensive approach. Group Dyn. Theory Res. Pract. 2013, 17, 207–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peperkoorn, L.S.; Hill, R.A.; Barton, R.A.; Pollet, T.V. Meta-analysis of the red advantage in combat sports. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 30822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiß, J.; Mentzel, S.V.; Busch, L.; Krenn, B. The influence of colour in the context of sport: A meta-analysis. Int. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2022, 22, 177–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lochbaum, M.; Sherburn, M.; Sisneros, C.; Cooper, S.; Lane, A.M.; Terry, P.C. Revisiting the Self-Confidence and Sport Performance Relationship: A Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 6381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jekauc, D.; Fiedler, J.; Wunsch, K.; Mülberger, L.; Burkart, D.; Kilgus, A.; Fritsch, J. The effect of self-confidence on performance in sports: A meta-analysis and narrative review. Int. Rev. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2023, 18, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholls, A.R.; Taylor, N.J.; Carroll, S.; Perry, J.L. The Development of a New Sport-Specific Classification of Coping and a Meta-Analysis of the Relationship between Different Coping Strategies and Moderators on Sporting Outcomes. Front. Psychol. 2016, 7, 1674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, A.F.; Ramirez-Campillo, R.; Sarmento, H.; Afonso, J.; Clemente, F.M. Effects of training programs on decision-making in youth team sports players: A systematic review and meta-analysis. INPLASY—International Platform of Registered Systematic Review and Meta-analysis Protocols. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 6638672020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conejero Suárez, M.; Prado Serenini, A.L.; Fernández-Echeverría, C.; Collado-Mateo, D.; Moreno Arroyo, M.P. The Effect of Decision Training, from a Cognitive Perspective, on Decision-Making in Volleyball: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopp, A.; Jekauc, D. The Influence of Emotional Intelligence on Performance in Competitive Sports: A Meta-Analytical Investigation. Sports 2018, 6, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harris, D.J.; Allen, K.L.; Vine, S.J.; Wilson, M.R. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the relationship between flow states and performance. Int. Rev. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2021, 16, 693–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, O.; Swann, C.; Bennett, K.J.M.; Bird, M.D.; Goddard, S.G.; Schweickle, M.J.; Jackman, P.C. The performance and psychological effects of goal setting in sport: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. Rev. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2022, 17, 1050–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamieson, J.P. The Home Field Advantage in Athletics: A Meta—Analysis. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2010, 40, 1819–1848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, D.; Fletcher, D. Effects of Psychological and Psychosocial Interventions on Sport Performance: A Meta-Analysis. Sports Med. 2017, 47, 77–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clemente, F.M.; Ramirez-Campillo, R.; Castillo, D.; Raya-González, J.; Silva, A.F.; Afonso, J.; Sarmento, H.; Rosemann, T.; Knechtle, B. Effects of Mental Fatigue in Total Running Distance and Tactical Behavior During Small-Sided Games: A Systematic Review with a Meta-Analysis in Youth and Young Adult’s Soccer Players. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 656445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Geok Soh, K.; Mohammadi, A.; Toumi, Z. The counteractive effects of interventions addressing mental fatigue on sport-specific performance among athletes: A systematic review with a meta-analysis. J. Sports Sci. 2024, 42, 2279–2291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habay, J.; Uylenbroeck, R.; Van Droogenbroeck, R.; De Wachter, J.; Proost, M.; Tassignon, B.; De Pauw, K.; Meeusen, R.; Pattyn, N.; Van Cutsem, J.; et al. Interindividual Variability in Mental Fatigue-Related Impairments in Endurance Performance: A Systematic Review and Multiple Meta-regression. Sports Med. Open 2023, 9, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhao, S.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, X.; Liang, T.; Ning, Z. The Effects of imagery practice on athletes’ performance: A multilevel meta-analysis with systematic review. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindsay, R.S.; Larkin, P.; Kittel, A.; Spittle, M. Mental imagery training programs for developing sport-specific motor skills: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Phys. Educ. Sport Pedagog. 2023, 28, 444–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonsmeier, B.A.; Androniea, M.; Buecker, S.; Frank, C. The effects of imagery interventions in sports: A meta-analysis. Int. Rev. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2020, 14, 186–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toth, A.J.; McNeill, E.; Hayes, K.; Moran, A.P.; Campbell, M. Does mental practice still enhance performance? A 24 Year follow-up and meta-analytic replication and extension. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2020, 48, 101672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, N.; Soh, K.G.; Abdullah, B.B.; Huang, D. Does Motor Imagery Training Improve Service Performance in Tennis Players? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garzón Mosquera, J.C.; Araya Vargas, G.A. Metaanálisis: Efectos de técnicas de preparación mental basadas en imaginería—Hipnosis sobre flow y rendimiento deportivo. Pensar Mov. Rev. Cienc. Ejerc. Salud 2020, 18, e39287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, Y.C.; Lu, F.J.H.; Gill, D.L.; Hsu, Y.W.; Wong, T.L.; Kuan, G. Effects of mental toughness on athletic performance: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2023, 22, 1317–1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Si, X.W.; Yang, Z.K.; Feng, X. A meta-analysis of the intervention effect of mindfulness training on athletes’ performance. Front. Psychol. 2024, 15, 1375608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bühlmayer, L.; Birrer, D.; Röthlin, P.; Faude, O.; Donath, L. Effects of Mindfulness Practice on Performance-Relevant Parameters and Performance Outcomes in Sports: A Meta-Analytical Review. Sports Med. 2017, 47, 2309–2321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ptáček, M.; Lugo, R.G.; Steptoe, K.; Sütterlin, S. Effectiveness of the mindfulness–acceptance–commitment approach: A meta-analysis. Int. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2023, 22, 1229–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maudrich, T.; Ragert, P.; Perrey, S.; Kenville, R. Single-session anodal transcranial direct current stimulation to enhance sport-specific performance in athletes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Brain Stimul. 2022, 15, 1517–1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shyamali Kaushalya, F.; Romero—Arenas, S.; García—Ramos, A.; Colomer—Poveda, D.; Marquez, G. Acute effects of transcranial direct current stimulation on cycling and running performance. A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. J. Sport Sci. 2021, 22, 113–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kämpfe, J.; Sedlmeier, P.; Renkewitz, F. The impact of background music on adult listeners: A meta-analysis. Psychol. Music 2010, 39, 424–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terry, P.C.; Karageorghis, C.I.; Curran, M.L.; Martin, O.V.; Parsons-Smith, R.L. Effects of music in exercise and sport: A meta-analytic review. Psychol. Bull. 2020, 146, 91–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, M.-Q.; Hou, X.-H.; Liao, B.-G.; Liao, J.-W.; Hu, M. The effect of neurofeedback training for sport performance in athletes: A meta-analysis. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2018, 36, 114–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skalski, D.; Łosińska, K.; Prończuk, M.; Tyrała, F.; Trybek, G.; Cięszczyk, P.; Pietraszewski, P. Effects of real-time EEG neurofeedback training on cognitive, mental, and motor performance in elite athletes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Biomed. Hum. Kinet. 2025, 17, 249–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.-L.; Cheng, M.-Y.; An, X.; Chueh, T.-Y.; Wu, J.-H.; Wang, K.-P.; Hung, T.-M. The effect of EEG Neurofeedback training on sport performance: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2024, 35, e70055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, R.; Zheng, M.; Liu, S.; Guo, J.; Cao, C. Effects of Perceptual-Cognitive Training on Anticipation and Decision-Making Skills in Team Sports: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, A.P.; Mallinson-Howard, S.H.; Jowett, G.E. Multidimensional perfectionism in sport: A meta-analytical review. Sports Exerc. Perform. Psychol. 2018, 7, 235–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Madigan, D.J.; Hill, A.P. Multidimensional perfectionism and sport performance: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. Rev. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2025, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.-H.; Yang, H.J.; Choi, C.; Bum, C.-H. Relationship between Athletes’ Big Five Model of Personality and Athletic Performance: Meta-Analysis. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rowley, A.; Landers, D.M.; Kyllo, L.B. Does the iceberg profile discriminate between successful and less successful athletes? A meta-analysis. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 1995, 17, 185–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beedie, C.J.; Terry, P.C.; Lane, A.M. The Profile of Mood States and athletic performance: Two meta-analyses./Le Profil des etats d’humeur et la performance athletique: Deux meta analyses. J. Appl. Sport Psychol. 2000, 12, 49–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lochbaum, M.; Zanatta, T.; Kirschling, D.; May, E. The Profile of Moods States and Athletic Performance: A Meta-Analysis of Published Studies. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2021, 11, 50–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rupprecht, A.G.O.; Tran, U.S.; Gröpel, P. The effectiveness of pre-performance routines in sports: A meta-analysis. Int. Rev. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2021, 17, 39–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Low, W.R.; Sandercock, G.R.H.; Freeman, P.; Winter, M.E.; Butt, J.; Maynard, I. Pressure training for performance domains: A meta-analysis. Sport Exerc. Perform. Psychol. 2020, 10, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayranci, M.; Aydin, M.K. The complex interplay between psychological factors and sports performance: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0330862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.J.; Kang, H.W.; Park, S.M. The Effects of Psychological Skills Training for Archery Players in Korea: Research Synthesis Using Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reinebo, G.; Alfonsson, S.; Jansson-Fröjmark, M.; Rozental, A.; Lundgren, T. Effects of Psychological Interventions to Enhance Athletic Performance: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sports Med. 2023, 54, 347–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barker, J.B.; Slater, M.J.; Pugh, G.; Mellalieu, S.D.; McCarthy, P.J.; Jones, M.V.; Moran, A. The effectiveness of psychological skills training and behavioral interventions in sport using single-case designs: A meta regression analysis of the peer-reviewed studies. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2020, 51, 101746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebeau, J.-C.; Liu, S.; Sáenz-Moncaleano, C.; Sanduvete-Chaves, S.; Chacón-Moscoso, S.; Becker, B.J.; Tenenbaum, G. Quiet Eye and Performance in Sport: A Meta-Analysis. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2016, 38, 441–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirnik, M.; Erčulj, F.; Rošker, J. Research of visual attention in basketball shooting: A systematic review with meta-analysis. Int. J. Sports Sci. Coach. 2022, 17, 1195–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunte, R.; Cooper, S.B.; Taylor, I.M.; Nevill, M.E.; Boat, R. The mechanisms underpinning the effects of self-control exertion on subsequent physical performance: A meta-analysis. Int. Rev. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2021, 17, 370–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lochbaum, M.; Sisneros, C.; Cooper, S.; Terry, P.C. Pre-Event Self-Efficacy and Sports Performance: A Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis. Sports 2023, 11, 222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moritz, S.E.; Feltz, D.L.; Fahrbach, K.R. The relation of self-efficacy measures to sport performance: A meta-analytic review. Res. Q. Exerc. Sport 2000, 71, 280–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, M.S.; Robson, D.A.; Martin, L.J.; Laborde, S. Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Self-Serving Attribution Biases in the Competitive Context of Organized Sport. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2020, 46, 1027–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hatzigeorgiadis, A.; Zourbanos, N.; Galanis, E.; Theodorakis, Y. Self-talk and sports performance: A meta-analysis. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2011, 6, 348–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murdoch, E.M.; Lines, R.L.J.; Crane, M.F.; Ntoumanis, N.; Brade, C.; Quested, E.; Ayers, J.; Gucciardi, D.F. The effectiveness of stress regulation interventions with athletes: A systematic review and multilevel meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Int. Rev. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2021, 17, 145–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, M.B.; McCullagh, P.; Wilson, G.J. But what do the numbers really tell us?: Arbitrary metrics and effect size reporting in sport psychology research. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2007, 29, 664–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albertella, L.; Kirkham, R.; Adler, A.B.; Crampton, J.; Drummond, S.P.; Fogarty, G.J.; Yücel, M. Building a transdisciplinary expert consensus on the cognitive drivers of performance under pressure: An international multi-panel Delphi study. Front. Psychol. 2023, 13, 1017675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCleery, J.; Diamond, E.; Kelly, R.; Li, L.; Ackerman, K.E.; Adams, W.M.; Kraus, E. Centering the female athlete voice in a sports science research agenda: A modified Delphi survey with Team USA athletes. Br. J. Sports Med. 2024, 58, 1107–1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quartiroli, A.; Wagstaff, C.R.D. Practitioners in search of an identity: A Delphi study of sport psychology professional identity. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2024, 71, 102567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).