Simple Summary

This review summarizes current knowledge of insect visual systems and how these visual abilities have become pivotal to everyday insect behaviors, such as flying, food or partner seeking, and predator avoidance. The diversity of the structures of the insect eye faces a fundamental trade-off: eyes must either be capable of high spatial acuity or highly sensitive to low light at night. We bring together knowledge from studies spanning the basic structure and genetics of the insect eye to brain image processing, highlighting the potential of this information for the design of new, smart, and sustainable methods of harmful insect control, such as highly selective light traps and visual deterrents.

Abstract

The ability of an animal to perceive its visual environment underpins many behaviors essential to survival, including navigation, foraging, predator avoidance, and recognition of conspecific individuals, making vision a critical element of both reproductive success and survival itself. In insects, eyes have evolved widely, shaped by different habitats and lifestyles, with striking examples such as the high-resolution diurnal vision of dragonflies, which enables rapid detection of prey and environmental features, in contrast with the highly sensitive nocturnal optical system of hawkmoths, which specializes in capturing even single photons. At the core of this diversity is a fundamental trade-off: at one extreme lies sensitivity, the ability to perceive visual stimuli, even under poor lighting conditions. At the other extreme, acuity, is the ability to resolve fine spatial details. This review seeks to synthesize current knowledge of insect visual systems, from their evolutionary origins to the developmental processes so far identified, from cellular organization to their role in behavior, to provide insights for designing novel, targeted, and sustainable vision-based technologies for the control of pest insects.

1. Comparative Anatomy of Insect Visual Organs

The visual system of insects is a very important field of study in biology, providing profound insights into the astonishing adaptability and evolutionary innovation of life. Crucially, the extensive differences in the structure and function of these eyes are studied precisely because vision is the primary sensory modality governing nearly all essential behaviors, including foraging, navigation, predator avoidance, and successful reproduction [1].

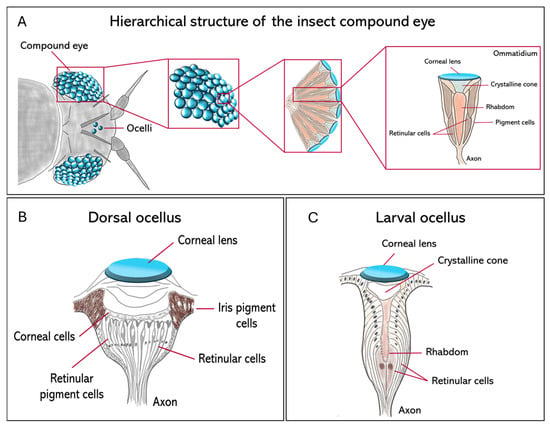

Insect visual systems differ widely in both structure and function, with over half a billion years of evolutionary change. They include three main types of eyes, compound eyes (Figure 1A), ocelli (Figure 1B), and larval stemmata (Figure 1C), each adapted to different ecological and developmental contexts.

Figure 1.

Comparative anatomy of the principal insect visual organs. Schematic diagrams show the structural organization of the compound eye, dorsal ocellus, and larval stemma in insects. (A) The hierarchical structure of the apposition compound eye. The arrangement of individual photoreceptive units (ommatidia) that forms the whole organ is represented. An ommatidium is made of a corneal lens and a crystalline cone, which focus light onto the rhabdom, which is formed by the microvilli of several retinular cells; (B) the adult dorsal ocellus, characterized by a single large corneal lens overlying a broad, continuous retina of retinular cells; (C) the larval stemma, a simple photoreceptive organ in holometabolous larvae, composed of a lens and a small number of retinular cells.

Compound eyes serve as primary vision tools in mature insects and are constituted by repeating units called ommatidia (Figure 1A). Their number and morphology vary significantly between species. For example, parasitoid wasps such as Trichogramma evanescens and Megaphragma mymaripenne (Hymenoptera, Trichogrammatidae) may have only a few dozen ommatidia [2,3], while dragonflies such as Anax junius (Odonata, Aeshnidae) reach around 30,000 per eye, providing them with exceptionally high spatial resolution and strong motion sensitivity [4,5]. In the case of blowflies like Calliphora vicina (Diptera, Calliphoridae), there are large, specialized frontal ommatidia to facilitate high-acuity tracking in aerial predation [6]. Three major compound eye designs have evolved across insects as solutions to solve the classical trade-off between sensitivity and acuity. Apposition eyes are typical for diurnal insects, such as honeybees, Apis mellifera (Hymenoptera, Apidae), and prioritize high acuity by optically isolating individual ommatidia; superposition eyes, characteristic of nocturnal moths, including Deilephila Elpenor (Lepidoptera, Sphingidae), maximize sensitivity at the expense of acuity by allowing multiple lenses to focus light onto shared photoreceptors; finally, neural superposition eyes, found in dipterans such as Musca domestica (Diptera, Muscidae), represent a powerful compromise: their sensitivity (the ability to detect light under low-light conditions) increases without a significant decline in acuity (the ability to distinguish fine spatial details) [6,7]. Despite functional variability, compound eyes commonly exhibit a conserved basic architecture: each ommatidium contains four cone cells and eight photoreceptors. Recently, the use of synchrotron X-ray microtomography has enabled the non-invasive 3D reconstruction, at very high resolution, of such internal structures in a variety of groups, including Coleoptera [8] and Lepidoptera [9], with implications for understanding their optical anatomies.

In addition to compound eyes, most insect species exhibit a pair, or a triad, of simple dorsal eyes called ocelli, which are ancient visual organs specialized for flight control rather than high-resolution image formation (Figure 1B). These light-sensitive organs are found in flies, grasshoppers, and mantids, among others, and are usually arranged in a three-lens configuration. They contain defocused optics and are very sensitive to extensive changes in illumination from the entire sky or horizon [10,11]. The primary function of the ocelli is to stabilize flight through rapid visual feedback, thereby maintaining the insect’s midair orientation. Neural recordings from ocellar pathways usually show a phasic response, meaning that they react to changes in light intensity (the amount of light emitted or reflected by a light source) rather than to the overall brightness (the subjective perception of light level as experienced by the visual system). This makes the ocelli well adapted to estimating the angular speed of the visible scene, with a significantly shorter latency than is feasible with compound eyes [12]. Compared to the slower image-forming input from compound eyes, the rate-dependent signal from the ocelli provides a far more rapid route to flight stabilization. This quick input is especially important during sudden orientation shifts, when the insect can carry out continuous high-speed corrections to stay upright and oppose rotational disturbances during flight [12,13]. This is particularly important for insects such as the honeybee, A. mellifera, which lacks the gyroscopic halteres that dipteran flies use for stability [13]. Even though the flight of honeybees is still possible in cases when their ocelli are occluded, the precision of flight and the ability to maintain a course stably are significantly reduced, thus underlining the role of ocelli in providing an immediate estimate of angular velocity necessary for robust flight control.

Larval visual organs, called stemmata, represent another example of evolutionary flexibility in insect vision (Figure 1C). Stemmata are simpler in structure than compound eyes but often retain homologous cell types, such as cone cells, pigment cells, and retinula cells [14], while retaining a high degree of evolutionary plasticity [15]. In Drosophila melanogaster (Diptera, Drosophilidae), the Bolwig organ is a rudimentary larval visual system that shares developmental gene expression with adult photoreceptors [11]. In Tribolium castaneum (Coleoptera, Tenebrionidae), the transcription factor glass is expressed in both the stemmatal and ommatidial photoreceptors, supporting their shared origin [16]. In the most highly miniaturized forms, such as first-instar larvae of Strepsiptera, ultrastructural reconstructions show functional but highly reduced eye structures [17].

As extensively reviewed by Gilbert [18], over evolutionary time, the stemmata have diversified in two principal directions: fusion and expansion. For instance, the stemmata of the sawfly, Perga affinis (Hymenoptera, Pergidae), represent a fusion of multiple ommatidia into a single-lens system that can accommodate hundreds of photoreceptors [19]. In contrast, in tiger beetle larvae, Cicindela chinensis (Coleoptera, Cicindelidae), the stemmata evolved through the dramatic enlargement of individual ommatidia, creating tiered arrays of thousands of photoreceptors behind a single, massive lens [20]. This kind of layered retina enables such larvae to scan their environments, thus creating a high-resolution image of their surroundings to find prey—a strategy fundamental to stemmata functional versatility [18]. This is also the case for swallowtail butterfly larvae, Papilio xuthus (Lepidoptera, Papilionidae), which exhibits a similar tiered arrangement of photoreceptors that cooperate in the formation of a basic image [20,21]. Interestingly, these optical modifications, especially the use of low F-numbers (which represent the proportion of the focal length with respect to the aperture diameter and, therefore, signify a wide opening capable of maximizing light collection), seem to be an adaptation for delivering maximum visual performance at sites of scant visibility, where photon supply is minimal [14].

The complexity of vision in larvae is highest in aquatic environments. In the diving beetle, Thermonectus marmoratus (Coleoptera, Dytiscidae), for example, bifocal lenses within the stemmata project onto two distinct retinas, enabling parallel processing of spatial and spectral information, including polarized light [22]. Indeed, recent fossil finds of Cretaceous lacewings are consistent with the proposition that refined binocular vision and the convergent evolution of complex simple eyes occurred very early on in the history of holometabolous insects [15]. A further increase in structural complexity is encountered in the larval visual system of Aedes aegypti (Diptera, Culicidae), which has five discrete stemmata on either side: dorsal anterior, dorsal posterior, central, ventral, and satellite. Each has fused rhabdoms formed by converging photoreceptors that differentially express two long-wavelength-sensitive rhodopsins: Aaop3, expressed in all five, and Aaop7, confined to the central and satellite units [23].

These examples collectively demonstrate the impressive evolutionary adaptability of basic visual components, from the high-resolution compound eyes of A. junius and C. vicina to the specialized larval stemmata of T. marmoratus and A. aegypti. These structural variations did not occur randomly but were shaped by ecological pressures and distinct developmental pathways. Overall, they stress the impressive adaptive potentials of insect eyes across life stages, habitats, and evolutionary lineages.

2. Evolutionary and Morphological Diversity of Insect Eyes

The evolution of the insect visual system is highly diverse and is influenced by evolutionary history, ecological context, and life stage. Although certain model groups of organisms, such as Drosophila and Apis, have contributed significantly towards understanding vision, it is important to appreciate that these organisms are only a limited representation of the insect world.

2.1. Evolutionary Origins and Optical Strategies

The compound eye is representative of the arthropod body plan and had its origins some 500 million years ago, during the Cambrian explosion [24,25]. Enough evidence from early fossil arthropods (such as trilobites and radiodonts) has already suggested that the ancestral visual organ was a modular structure that consisted of repeating optical units. This ancient design has largely diversified in different lineages over the course of evolution to satisfy ecological niches [26].

Although the basic underlying modular architecture is conserved, important variations have emerged in the optical mechanisms―e.g., apposition vs. superposition. In the ancestral anatomical apposition eye, as in the diurnal insect, optical isolation of each ommatidium by pigment cells ensures high resolution. Conversely, the superposition eye is an important innovation for nocturnal lineages: here, by moving the screening pigments away from the tip, many lenses may focus their light on a single rhabdom, strongly increasing photon capture at the expense of resolution [24].

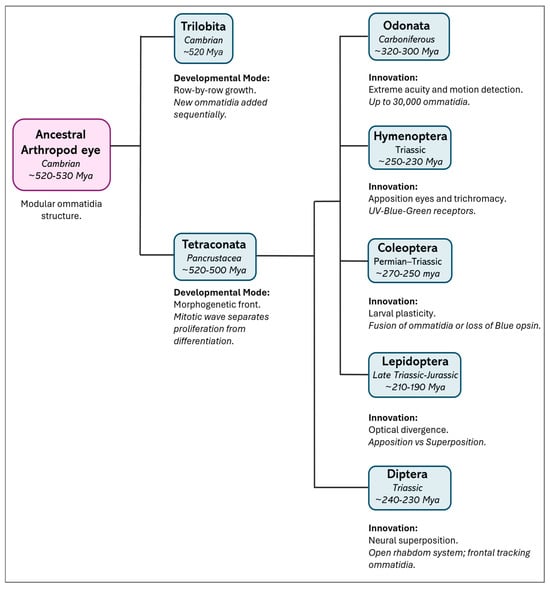

Comparative studies across arthropods reveal deeper evolutionary patterns in eye development. In particular, in all euarthropods, the mode of retinal growth diverges, although they have a proliferation zone at the edge of the developing eye field. In Trilobita (extinct marine arthropods), Xiphosura (marine chelicerates), and Diplopoda (terrestrial myriapods), eye formation occurs in a “row-by-row” fashion, with large ommatidia added sequentially and existing units continuing to enlarge after formation through intercalary growth [27,28,29]. In contrast, members of Tetraconata (Hexapoda + Crustacea) develop their eyes according to a “morphogenetic front” model. In this model, new ommatidia are generated from a mitotic zone and organized by a morphogenetic furrow that moves across the eye field, spatially and temporally separating proliferation from differentiation. This process has been thoroughly characterized in Drosophila and occurs in crustaceans such as Homarus americanus (Decapoda, Nephropidae) and Procambarus clarkii (Decapoda, Cambaridae), although the formation of pre-clusters is often less well defined in these species [29,30,31,32,33].

Interestingly, the centipede Scutigera (order Scutigeromorpha) shows a middle-type development, where its proliferation zone forms discrete proto-ommatidial clusters without a continuous morphogenetic front, suggesting a transitional developmental strategy between ancestral and derived states [29,34]. These developmental trajectories broadly parallel phylogenetic relationships and support the monophyly of Tetraconata, characterized by a fixed ommatidial blueprint and a spatially structured developmental process (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Evolutionary divergence and key innovations in the insect visual system. The schematic illustrates eye diversity from the common arthropod ancestor to existing insect orders. Divergence times (in italics) are approximate estimates based on phylogenomic data [35]. A major developmental split occurred between the extinct group Trilobita, in which eyes developed by adding new rows (“row-by-row” development) [27], and Tetraconata [29,34] (Crustacea + Hexapoda), where a layer of dividing cells (the “morphogenetic front”, driven by a mitotic wave) allowed for the development of a visual system called “neural superposition”—where signals from several neighboring units are combined to improve sensitivity. Hexapods further adapted their vision for different environments: “Apposition eyes,” found in Odonata (dragonflies and damselflies) and Hymenoptera (bees, wasps, ants), have separate units for each focus point, offering high resolution and color vision [4,36]. Coleoptera (beetles) [18,19] and Lepidoptera (butterflies and moths) [21] use simple eyes (strong stemmata) as larvae and, as adults, adjust vision for various light levels—moths develop “superposition eyes,” where multiple units gather light to see better in the dark. Diptera (flies) [37] use “neural superposition” to boost sensitivity while maintaining sharpness.

In particular, the visual systems of insects are very diversified due to ecological demands and lifestyles. This diversity is strongly supported by the evolution and functional differentiation of the opsin genes. The process of gene duplication enabled insects to extend their spectral capabilities from a UV/blue–green-sensitive ancestral receptor array to one that can tolerate red light or even specialized UV receptors for navigation [38]. Thus, the honeybee, A. mellifera, develops large, forward-facing compound eyes that harbor three types of photoreceptors sensitive to UV, blue, and green wavelengths. This is a trichromatic configuration that allows for accurate color vision and acceptable spectral discrimination, important for foraging in general and flower identification in particular [39]. At the other extreme, the red flour beetle, T. castaneum, adapted to living in dark and concealed habitats, has undergone significant visual reduction. Its compound eyes lack blue-sensitive photoreceptors because they lack the corresponding opsin gene and its processing machinery, resulting in a dichromatic system based on UV- and long-wavelength-sensitive opsins. Uniquely, Tribolium co-expresses two long-wavelength opsins across the retina; this may be a strategy to improve achromatic contrast sensitivity instead of color discrimination and is a likely adaptation to low-light conditions [40]. A contrast between the red flour beetle and the honeybee shows how distinct environmental demands shape vision, despite their similar genetic origins. During the day, the honeybee relies on precise navigation for pollination, forming compound eyes through placode-type tissue development alongside a regular pattern of ommatidia maturation [41]. In sharp contrast, T. castaneum, a cryptozoic pest beetle that thrives in the perpetual darkness of stored grain, exhibits altered developmental dynamics, consistent with its reduced visual ecology. Hence, both insects have lifestyles that have taken their visual capabilities in fundamentally opposite directions. Table 1 provides a comprehensive representation of this vision in key insects.

Table 1.

Overview of adaptive visual diversity across major insect orders.

2.2. Developmental Mechanisms: From Embryos to Adults

Although the output differs, the basic mechanism of eye development depends on a conserved genetic toolkit. In holometabolous insects such as Drosophila, compound eyes form post-embryonically from a specialized epithelial primordium, the eye–antennal imaginal disc. During larval development, a wave of differentiation (the morphogenetic furrow) moves across this epithelial primordium, organizing the recruitment, specification, and patterning of cells into the exact crystalline arrays of ommatidia [60].

The key regulatory gene at the top of the developmental hierarchy is Pax6 (the eyeless gene in Drosophila), which is conserved throughout the animal kingdom and is essential for forming the early eye structure. Below Pax6, a complex gene regulatory network (GRN) controls every subsequent step in development, from cell proliferation ahead of the furrow to terminal differentiation of photoreceptor neurons, and the expression of specific rhodopsin genes that define their spectral sensitivities, whose regulatory elements have become essential tools for transgenesis and gene function studies in insects [61]. Because these GRNs coordinate not only structural assembly but also evolutionary adaptation, even minor mutations can trigger significant changes in vision. However, these biological programs can be associated with different anatomical contexts. For example, while in Drosophila, eye organs develop from the inner imaginal discs; in other organisms such as T. castaneum or A. mellifera, eye organs develop from lateral placode-like epithelial tissues. Nevertheless, these biological programs entail similar differentiation programs, in that they both spread from the posterior to anterior in both contexts [6].

It should be noted that the conserved nature of this developmental toolkit does not imply rigidity. In fact, small evolutionary changes in the timing, spatial distribution, or level of gene expression within the GRN can generate the extensive morphological diversity observed among insect eyes. Such modifications may underline major structural and functional innovations, including differences between apposition and superposition optics [37], or the emergence of localized high-acuity regions such as foveas, small central retinal areas with the highest density of photoreceptors that allow for precise and detailed vision. In that respect, variation in developmental programs is directly linked to the evolution of eye designs suited to ecological roles.

The transformation from the larval to the adult visual system during metamorphosis is a significant developmental event in which the simple larval eyes (stemmata) are replaced by the much more complex compound eyes and ocelli of the adult, reflecting the shift to a very different way of life and visual ecology [62]. This developmental change is regulated by a highly sensitive hierarchy of genetic and molecular cues.

Reduction is most salient in the larval stage of holometabolous insects. While compound eyes usually appear in adults, larvae develop simplified organs called stemmata. In more basal holometabolous taxa, such as the Mecoptera order, stemmata still exhibit a modular organization like that of compound eyes. In more derived ones, such as Diptera, stemmata are further reduced to single structures, as in the case of the Bolwig organ in Drosophila, which stays photoreceptive despite its extreme morphological reduction [11,63].

The evolutionary development of stemmata illustrates how a conserved developmental toolkit can give rise to a diverse range of eye morphologies. Stemmata arise from embryonic visual primordia, homologous with those that produce compound eyes, and recruit similar cell types, including photoreceptors, cone cells, and pigment cells. In different species, these may form enlarged single-lens units or more complex, fused image-forming structures. For example, larvae of T. marmoratus develop complex camera-type eyes with tiered retinas and bifocal lenses, all derived from typical ommatidial cell populations. This case helps in illustrating how modifications in developmental timing and patterning can give rise to novel visual architectures suited to ecological pressures [14].

In addition to the elaboration of complex compound eyes, reduction and remodeling are standard features of insect visual development. Many such changes are ecological in nature, representing shifts to parasitic, subterranean, or larval lifestyles, in which full visual capacity no longer confers a selective advantage. One of the most dramatic examples occurs in the Strepsiptera order, in which the ancestral compound eye has been remodeled into independent image-forming “eyelets,” each acting as an individual single-lens unit, an apparent case of evolutionary reuse [52].

Taken together, these insect visual systems show how highly conserved genetic pathways can change multiple times in response to different environmental demands. In one lineage, these pathways yield complex, trichromatic eyes suited for flower recognition and navigation; in another, they underlie dramatic visual reductions and radical reorganization. Rather than static designs, insect eyes represent dynamic products of evolutionary tinkering, shaped and reshaped by lifestyle, environment, and selection.

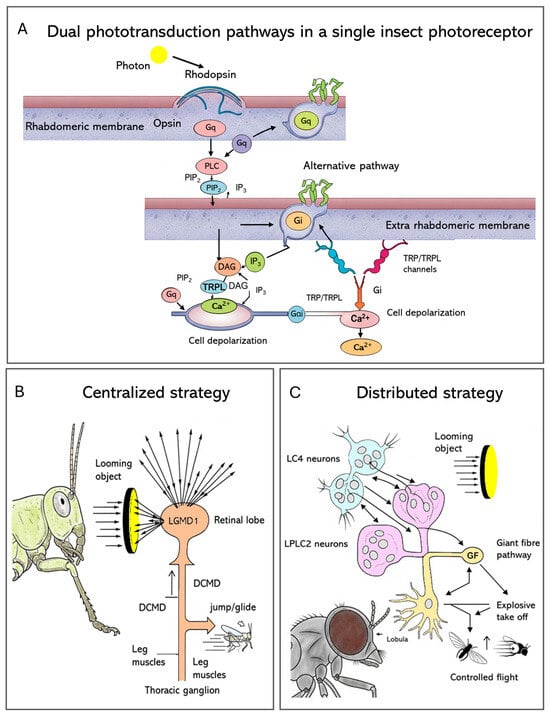

3. Molecular and Cellular Basis of Vision

Insect eyes begin with specialized light-sensitive cells (PRCs) in the retina, where phototransduction converts light into an electrical signal (Figure 3A). Light detection occurs within tiny structures called rhabdomeres: microvillar compartments filled with proteins known as opsins, which are linked to retinal molecules. When a photon hits, the retinal shifts shape, causing the attached opsin (typically a rhodopsin) to change form and switch on a Gq-type G heterotrimeric protein complex [64]. That activation leads to phospholipase C (PLC) being activated, breaking down PIP2 into two components: Diacylglycerol (DAG), along with Inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate (IP3). Second, messengers switch on TRP and TRPL ion channels, causing calcium entry plus membrane depolarization (Figure 3A). Because the q/PLC pathway acts quickly, it enables rapid vision processing, essential for actions such as flying [6,65].

Figure 3.

The molecular and neural basis of insect vision. (A) The canonical Gq/PLC or the alternative Gi/Opn3 phototransduction cascade is able to convert, within a photoreceptor, light into an electrical signal. (B) Locusts use a single Lobula Giant Movement Detector (LGMD1) neuron that gathers broad visual data and then activates the DCMD to drive fast escape reactions. (C) In Drosophila, two selective neuron groups (LC4 for angular velocity, LPLC2 for angular size) relay information to the Giant Fibre (GF) pathway, where combined input shapes appropriate getaway decisions.

Signal transmission, however, also requires a quick turn-off response for the light signal, which sets the temporal resolving power of vision [66]. After photon absorption, activated rhodopsin, also known as metarhodopsin, needs rapid deactivation to avoid chronic signaling [67]. The visual pigment requires rejuvenation via visual cycle renewal, plus light adaptation via screening pigment granule transport to rhabdomeres [68].

Variations in how insects detect light, colors, or movement—differing between species or within them—are influenced by changes in the evolutionary diversification and expression patterns of rhodopsin genes, helping in the understanding of sensory differences across insect groups [36].

Indeed, color vision comes from different opsins being active in specific PRCs, usually tuned to UV, blue, green, or longer wavelengths. For instance, the D. melanogaster eye, often used to study rhabdomeric light sensing, organizes its eight photoreceptors (R1–R8) into repeating units called ommatidia. Instead of sharing pigments, R1–R6 use Rh1 (~480 nm peak), helping detect movement. In contrast, central R7 and R8 carry separate opsin types that tell colors apart, especially differentiating between ultraviolet and green light (~330–520 nm) [69,70]. Even though these roles differ, every cell uses a nearly identical signaling path when catching light. Also, their response strength per photon stays consistent, so they work well over a broad range of light intensities [71]. The positioning and activity of these opsins adjust precisely to different insect environments, depending on species-specific needs [6].

The visual system of the bumblebee, Bombus impatiens (Hymenoptera, Apidae), illustrates the hierarchical processing of visual information, from photoreceptor signals relayed from the lamina through the medulla and lobula to the lateral protocerebrum [72]. The segregation is both functional and anatomical: distal lobula neurons detect movement and send outputs backward, while proximal lobula neurons process color. This organization results in a pattern where anterior protocerebral neurons are tuned to color, and posterior neurons are tuned to motion [72]. Recent findings reveal that phototransduction is more complex than previously believed. In A. aegypti, an opsin homologous to vertebrate Opn3 (called AeOpn3) was found in R7 cells, but it was localized not to the rhabdomere, as expected, but to the extra-rhabdomeric cytoplasm. Unlike classical visual opsins, AeOpn3 activates a Gi-type G protein and not the canonical Gq. That means that one photoreceptor may run two separate light detection systems at once: a fast Gq/PLC pathway for rapid, image-forming vision, while a slower Gi/Opn3 pathway handles tasks such as daily rhythm adjustment or prolonged light exposure [73]. These dual phototransduction mechanisms indicate a functional division within the same cell and enable parallel processing of visual information, with modulatory responses. Molecular and cellular signaling in photoreceptors provides the critical input to higher-order neural circuits that integrate visual information and drive rapid behavioral responses. There is further evidence for spatial and functional specialization in Anopheles stephensi, where MosOpn3 (a homolog of Opn3) is co-expressed with the short-wavelength-sensitive opsin Asop9 in dorsal and ventral R7 cells. This may suggest that two different G-protein-coupled pathways, Gq and Gi/Go, act in parallel within the same PRC and enhance spectral discrimination or modulate photoreceptor sensitivity depending on ambient light conditions [73].

Comparative studies of fireflies like Ellychnia corrusca and Lucidota atra (Coleoptera, Lampyridae) highlight how flexibly their light-sensing systems can evolve. While transcriptomic analyses still show limited opsin diversity, with UV- and long-wavelength-sensitive opsins dominating several downstream components of the cascade that have undergone adaptive diversification, genes such as inaD, trpl, arr2, Gq, and ninaC are under positive selection, especially in diurnal lineages such as Ellychnia and Lucidota. The scaffold protein inaD, central to assembling the rhabdomeric signaling complex, has duplicated in multiple species, possibly supporting region-specific expression or novel functions. These adaptations likely reflect selection for improved visual performance under high-light conditions [74].

The molecular-level tuning of the phototransduction apparatus in nocturnal species provides the direct physiological basis for remarkable nocturnal behaviors discussed later, such as hawkmoth color discrimination under starlight and the celestial navigation of single-photon-sensitive dung beetles. In Lepidoptera, the canonical phototransduction cascade is conserved but features lineage-specific modifications. The butterflies and moths share the Gq/PLC–TRP/TRPL cascade but also express unique opsins, such as UnRh and RGR-like opsins. UnRh, expressed in cone and pigment cells of Heliconius melpomene (Lepidoptera, Nymphalidae), shows a phylogenetic relation to squid retinochromes and may participate in the photoisomerization of retinal during rhodopsin regeneration. Furthermore, gene expression studies show that trp and trpl channels are upregulated in diurnal butterflies, consistent with high-light vision. In contrast, low trp expression in nocturnal moths, such as Manduca sexta (Lepidoptera, Sphingidae), suggests adaptation to dim light. Expression of other genes, including Calx and Nckx30C (involved in Ca2+ extrusion), further adjusts photoreceptor physiology to environmental light levels [65].

One of the most important tasks of any visual system is quickly detecting approaching objects to trigger escape, and insects have developed highly specialized neural circuits for this purpose. Comparing locusts and flies shows two different but equally effective evolutionary strategies for solving this problem.

In the locust, this function is mediated by the Lobula Giant Movement Detector (LGMD) (Figure 3B). A single, large interneuron, LGMD1, integrates visual information across the entire eye, making it extremely sensitive to the coherent expansion of a looming object. Its robust, reliable spiking response directly drives the Descending Contralateral Movement Detector (DCMD) neuron, which acts as a “command neuron” to trigger stereotyped escape behaviors like jumping or gliding [75]. This system employs a highly centralized architecture, with just a single neuron in charge of detecting threats and initiating escape. In contrast, Drosophila employs a more distributed, parallel approach for the same task (Figure 3C), with looming detection split between two groups of smaller neurons: Lobula Columnar (LC4—neurons that respond to the angular velocity of the moving object) and Lobula–Plate Lobula Columnar (LPLC2—neurons that encode its angular size). Their outputs are combined by the Giant Fiber (GF) escape pathway, resulting in computation that allows the fly to choose an appropriate escape response: launching into a quick, explosive takeoff when danger is close or beginning a more relaxed, deliberate flight when the threat seems less immediate [75].

This comparison between locusts and flies showcases how two different neural architectures, one centralized and the other distributed, come together to tackle the same basic survival challenge, highlighting functional specialization in the insect brain.

4. Physiological Mechanisms of Visual Processing

Insects have sophisticated visual systems that assist them in various activities—such as finding food, avoiding predators, moving, hunting, and maintaining daily rhythms. These functions are driven by specific brain pathways and tiny-level changes that interpret movement, color, distance, or light direction.

4.1. Adaptations for Sensitivity and Acuity

Visual features balance clarity with low-light sensitivity: diurnal insects enhance detail perception with closely packed eye units, quick signal conversion, and small viewing zones; nocturnal insects prefer detecting faint light through layered lenses, delayed cell responses, and signal integration in nerves. For example, elephant hawkmoths detect movement under starlight by combining spatial and temporal signals in a region of their optic lobe, allowing them to perceive motion even in star glow [76]. Although seeing color is not limited to daylight, hawkmoths and carpenter bees can discriminate colors in dim conditions thanks to three-receptor sight and amplified receptor output [77,78].

Some insects, like the night-active bee, Megalopta genalis (Hymenoptera, Halictidae) or the ant, Myrmecia pilosula (Hymenoptera, Formicidae), which initially have simple eye types, developed larger lenses and broader rhabdoms over time; this adaptation helps gather more light, showing how different species arrive at similar solutions for seeing in darkness. In terms of function, nocturnal insects’ light-detecting cells are built for maximum responsiveness and consistency. Instead of relying on speed, their receptors amplify signals more strongly—one photon produces a larger voltage spike, called a quantum bump, compared to day-living relatives. Moreover, these spikes last longer, which makes overlapping them easier and improves signal clarity during low-light conditions [79].

4.2. Color and Polarization Circuitry

Although sensitivity to light is necessary for survival when light levels are low, wavelength detection facilitates complex light interactions during the daytime. Color vision also varies across taxa; for example, fruit flies process color contrasts early on in a brain region called the medulla [80], and butterflies like P. xuthus detect four colors and use opposing signals in their first visual layer, the lamina [81]. Some species, like Graphium sarpedon (Lepidoptera, Papilionidae), possess up to 15 distinct photoreceptor types for fine spectral resolution [82].

These abilities are enhanced by physical modifications in their eyes—such as colored filters and uneven eye unit patterns—which improve color judgment during feeding or egg-laying.

In addition to chromatic cues, many insects exploit a visual modality invisible to humans: polarized light. Polarization vision functions through special cells at the top edge of the eye, along with separate pathways in the brain’s medulla: the dorsal rim area (DRA). The DRA is a unique part of its compound eye, showing how body features can enable precise navigation. Within the DRA, light-detecting cells are arranged in a fan-like pattern, with tiny structures oriented at right angles; this configuration detects the direction of polarized light with high sensitivity. Polarization vision is processed by these specialized DRA ommatidia and separate medulla circuits, creating a distinct pathway from other visual inputs.

4.3. Motion Detection and Neuromodulation

Among visual modalities, motion detection is among the most thoroughly characterized. Foundational models by Hassenstein and Reichardt (1956) [83] inform our understanding of optic flow processing in D. melanogaster, where Lobula Plate Tangential Cells (LPTCs) encode direction-selective signals for flight stabilization [84,85].

In hoverflies, Eristalis tenax (Diptera, Syrphidae), descending neurons that spot tiny moving objects work separately from those sensing broad visual motion—this split helps manage flight [86]. Instead of relying on movement clues, mantises see depth using both eyes together, thanks to special nerve cells in their optic lobe that judge how far away prey is by image differences [87].

On a more detailed scale, recent studies have revealed that muscles moving the retina to stabilize gaze in Drosophila [88] and a conserved system of photoreceptor microsaccades that enable hyperacute 3D vision beyond the limits predicted by static morphology [88].

Moreover, processing and interpretation of visual cues are under dynamic neuromodulatory control. Neuromodulators like octopamine and serotonin further reconfigure the sensitivity of the visual system to align visual processing with the animal’s internal state and behavioral context [89]. This is also triggered by locomotion, as evidenced, for instance, by increased visual sensitivity during flight in Drosophila [88]. At the molecular level, the expression of specific ion channels—such as TRP, TRPL, voltage-gated sodium channels, and fast potassium channels—ensures the rapid signal transduction and propagation required for behaviorally relevant visual tasks [90,91].

5. Visually Guided Behaviors in Ecological Contexts

Flying insects heavily depend on visual cues for navigation, avoiding obstacles, foraging, and homing. The visual information obtained in flight is further processed by highly specialized circuits that underpin basic behaviors such as phototaxis and optomotor responses, as well as higher-order cognitive skills, including spatial memory, landmark recognition, and path integration.

5.1. Navigation and Homing

Celestial signals are crucial for insects to find direction. The desert ant, Cataglyphis fortis (Hymenoptera, Formicidae), is able to detect polarized light from the sky using the DRA, showing how body features can enable precise navigation. Similarly, desert ants such as Veromessor pergandei (Hymenoptera, Formicidae) respond to sky polarization not only while searching alone but also when moving along chemical paths, showing that these sky-related systems work even in socially guided contexts [92]. This strategy is not unique to ants: nocturnal and diurnal dung beetles, such as Scarabaeus lamarcki (Coleoptera, Scarabaeidae), use polarized light along with sky brightness changes to move straight, changing course by tracking sunlight, moonlight, or how light scatters across the sky, depending on environmental conditions [93,94]. Some species can even use the Milky Way as a navigational reference [95]. These behaviors highlight the adaptability of polarization vision in diverse ecological scenarios, especially when integrated with social cues [92].

These navigational systems operate within a hierarchical framework: path integration provides rough position, whereas scene recognition helps pinpoint exact spots [96]. Many insect species practice path integration, combining celestial compass cues with an odometer based on optic flow or stride count, to continuously update the home vector [97,98].

5.2. Flight Control and Predation

In addition to compass navigation, vision is essential for immediate motor control. A common denominator for many taxa is the analysis of the pattern of visual motion produced by self-motion, also known as optic flow, which conveys essential information for flight control, landing, and odometry [99].

During flight, they compare motion across both eyes, which helps them stay centered when moving through tight spaces. Meanwhile, how fast images grow on their retina controls stopping behavior before obstacles or during landings [100,101,102]. To improve perception, insects use active vision strategies, such as saccadic flight patterns that distinguish rotational from translational optic flow, allowing for more accurate distance estimation during intersaccadic intervals [103].

This core relationship between structure and function is well illustrated in the divergent seeking strategy of predatory insects. Dragonflies, for instance, utilize their high-acuity dorsal foveas to track and intercept prey with extreme precision [104]. In cluttered environments, the bumblebee, Bombus terrestris (Hymenoptera, Apidae), deploys computational flexibility by switching from an averaging strategy to a maximum pooling of optic flow, thus responding to the most imminent threats [105].

Finally, visual cues play a pivotal role in social interactions, such as mate preference in Heliconius melpomene and H. timareta (Lepidoptera, Nymphalidae), where visual attraction can be modulated by genetic and social factors [106,107,108].

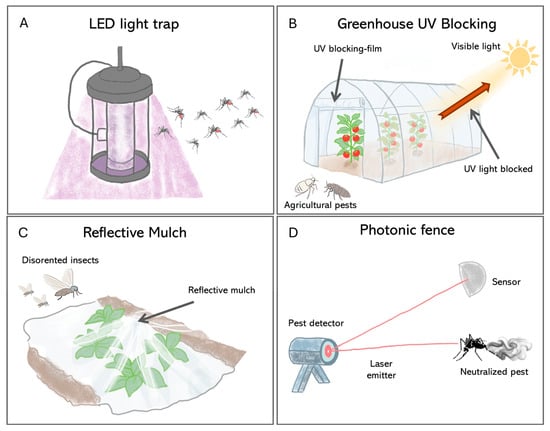

6. The Application of Light-Based Technologies in Pest Management

The principles of insect visual ecology currently offer a robust and sustainable pathway for the management of pests and vectors. Leveraging innate responses to light has enabled the development of a range of effective control strategies, evolving from broad approaches to specific, technologically advanced solutions [109].

This is best illustrated using light traps, which have evolved from broad-spectrum UV and incandescent devices to energy-efficient LED systems. Because insects perceive colors differently from humans, especially responding to UV, blue, or green ranges [110], traditional incandescent bulbs are suboptimal. Modern LEDs, however, can be tailored to emit specific wavelengths that match the known visual sensitivities of target insects like mosquitoes and phlebotomine sand flies, a targeted approach that has been shown to increase capture rates by up to 50% (Figure 4A) [111,112,113].

Figure 4.

Pest control strategies based on the manipulation of light. (A) This method uses LED lights tuned to specific wavelengths—drawing in bugs that move toward light and then trapping them. (B) In greenhouses, special films block UV rays but let visible light pass—this disrupts how pests like Bemisia tabaci (Hemiptera, Aleyrodidae) locate hosts without harming plant growth. (C) Reflective mulch modifies the light environment around crops; upwardly reflected sunlight confuses airborne insects so they avoid settling on crops. (D) The photonic fence represents an active control system that uses sensors to detect insects and a laser pulse to neutralize it in real-time.

More recently, advanced LED technology has further refined this approach by showing that while unmodulated UV light drastically enhances trapping for pests such as the Coconut Rhinoceros Beetle, Oryctes rhinoceros (Coleoptera, Scarabaeidae), and the Asian Citrus Psyllid, Diaphorina citri (Hemiptera, Psyllidae), specific visible wavelengths can have divergent effects—attracting psyllids via blue, yellow, and amber colors while suppressing beetle captures, thus enabling highly species-specific control strategies [114].

Beyond utilizing light as an attractant, light can also be used to suppress behavior. For instance, nocturnal pests can be inhibited by yellow or green light, which disrupts essential behaviors such as feeding and oviposition, while other wavelengths of light can act as repellents, effectively deterring insects from entering protected areas.

Indeed, beyond active light sources, passive optical interventions that modify the ambient visual environment are also effective. For example, UV-blocking plastic films can make greenhouses less visible to pests like whiteflies and thrips by disrupting their orientation and host-finding behaviors (Figure 4B), thus reducing infestation [115,116,117]. Similarly, reflective mulches interfere with the dorsal light response that many flying insects depend on for flight stabilization, thereby decreasing crop colonization rates (Figure 4C).

A different use applies computer-based visual systems to bypass human sensory limits that once restricted the development of logical tools [118,119]. By modeling the specific photoreceptor responses of a target insect, it is possible to engineer optimized visual lures. This approach has been used to design superior-colored traps for tse-tse fly (Glossina fuscipes; Diptera, Glossinidae) and Western flower thrip (Frankliniella occidentalis; Thysanoptera, Thripidae) control [120,121]. The future of this approach lies in the further development of such models to incorporate other key aspects of insect vision, such as their perception of polarized light from trap surfaces and how their characteristically low spatial acuity affects the detection of trap shapes from a distance [118,122].

The frontier in this field is the development of intelligent optical systems that integrate real-time surveillance with lethal intervention. A key example is the “Photonic Fence” (Figure 4D). This robotic approach utilizes machine vision to recognize and track flying insect vectors and a retina-safe laser to neutralize them mid-flight [123,124]. Field trials have shown that this method can selectively eliminate target pests such as A. aegypti and Diaphorina citri (Hemiptera, Psyllidae) with more than 97% efficacy while leaving non-target insects unharmed [124]. Since its mode of action is thermal damage, it precludes resistance evolution common with chemical insecticides [125]. These kinds of technologies allow for the creation of a nonchemical zone for vector interception and provide high-resolution surveillance data, a new paradigm for the protection of public health and agriculture [126].

Taken together, these innovations give an excellent example of progress, from broad light-based methods to precise, vision-guided technologies of targeted, greener pest control practices.

While our understanding of insect vision has grown enormously, from the kinetics of phototransduction to the circuits for motion detection, conveying such knowledge into effective pest control remains a formidable challenge. Although significant progress has been made in computational modeling and LED technology, a substantial amount of related research continues to employ overly simplified spectral sensitivity profiles. Current modeling approaches frequently overlook critical intra-specific variations, such as sexual dimorphism in Aedes spp. [127], as well as the synergistic interactions between visual, olfactory, and polarization cues. Moreover, there are few long-term field efficacy studies. Research primarily focuses on model organisms, such as Drosophila and Apis [128], while overlooking medically important vectors. Finally, trap design often overlooks the physiological limits of the insect compound eye. Its poor spatial resolution (1–2° vs. 0.01° in humans) makes it hard for insects to resolve shapes and distances [129], a fact that current predictive models ignore.

The use of visual technology in the control of pests presents its own set of challenges, including the development of resistance to the laser technology used in the Photonic Fence, scalability costs for subsistence farming in developing nations, and the impact on non-target pollinators [124]. However, the prospects are promising. The synergy between “vision-based” genetic modification for sterile insect carriers and LED drones could help lower chemical insecticide consumption by 50–70% by 2030. Alongside Machine Intelligence for live surveillance, this “visual–sterile insect technique” offers a sustainable model for dengue and malaria control in the face of the increasing threat in the EU.

To overcome these limitations in future studies, there is an imperative need to pursue key critical priorities: (1) the development of multi-modal fusion objects (visuo-olfactory) by AI to create “smart” traps that can respond to environmental stimuli [129,130]; (2) conducting genomic and CRISPR studies on larval opsins to identify specific targets [131], such as RNAi silencing of Aaop3 in mosquitoes; (3) Confirmation of results in various species by connectomics, mapping key disease vectors; and (4) developing eco-specific 3D models accounting for intricate details such as crepuscular phototaxis and retinal micromovements to predict behavior accurately [129].

7. Conclusions

The insect compound eye is a striking example of evolutionary adaptation and morphological diversity, shaped by the unique ecological and behavioral demands of each species. Its role in mediating vital behaviors such as navigation, mate finding, and predator-prey interactions attests to its evolutionary importance. The major architectural types we described (apposition, optical superposition, and neural superposition eyes) represent distinct optical strategies for handling environmental challenges, such as obtaining high diurnal acuity or increasing nocturnal sensitivity and motion detection. This functional sophistication is not only about structural diversity across species but also about neural organization within a single insect. In fact, insects use visual information in a modular way, assigning specialized regions of the visual system and brain circuits to specific tasks.

Historically, efforts to utilize insect vision in practical applications, such as pest management, have been limited by human-centric biases, especially in designing traps and lures based on human color preferences. More recently, advances in computational modeling have overcome these limitations by simulating visual stimuli from the insect’s viewpoint, guided by species-specific photoreceptor sensitivities. This approach has led to the rational design of highly effective visual traps for pests such as Glossina spp. [132] and F. occidentalis [133], confirming that insect visual preferences diverge considerably from human intuition [120].

Beyond applied entomology, the study of insect vision greatly improves our understanding of the core principles that control neural circuit design. It is not surprising that many key organizational features—such as the parallel processing pathways for different visual types, hierarchical synaptic refinement across brain regions, and the modular tiling of the visual field—are conserved across various phyla in a way similar to vertebrate visual systems. These striking parallels suggest that evolutionary pressures have independently converged upon the most optimal strategies for processing visual information. Thus, the insect eye is more than just a model for ecological adaptation; it is a robust system for uncovering general principles in neurobiology. Easy to access, amenable to experimental manipulation, and evolutionarily diverse, it provides a unique tool for understanding the rules that govern the development and function of complex neural circuits—lessons that are ultimately crucial to also understanding the architecture of the human brain. Nevertheless, several significant challenges and opportunities remain. Future models of vision will need to incorporate additional aspects of insect visual perception, such as sensitivity to polarized light and the effects of low spatial resolution on shape detection at ecologically relevant distances. These factors must be incorporated into the next generation of species-specific, vision-based control technologies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.V. and M.S.; writing—original draft preparation, M.V.; writing—review and editing, M.V., M.S., P.D.L., F.L., G.V., A.C., S.M.M., S.A. and G.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the EU within the NextGeneration EU-MUR PNRR Extended Partnership initiative on Emerging Infectious Diseases (Project no. PE00000007, INF-ACT) (MS).

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used Claude AI, Gemini 3 Pro, and the Grammarly free for written English proofreading. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| GRN | Gene Regulatory Network |

| PLC | Phospholipase C |

| PIP2 | Phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate |

| DAG | Diacylglycerol |

| IP3 | Inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate |

| TRP | Transient Receptor Potential (ion channel) |

| TRPL | TRP-like (ion channel) |

| PRC | Photoreceptor cell |

| DRA | Dorsal rim area |

| LGMD | Lobula Giant Movement Detector |

| DCMD | Descending Contralateral Movement Detector |

| LC4 | Lobula Columnar (neuron) |

| LPLC2 | Lobula–Plate Lobula Columnar (neuron) |

| GF | Giant Fiber (escape pathway) |

| LPTC | Lobula Plate Tangential Cell |

References

- Tomsic, D.; Theobald, J. Insect Neurobiology: An Eye to Forward Motion. Curr. Biol. 2017, 27, R1156–R1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, S.; Muller, C.H.G.; Meyer-Rochow, V.B. How Small Can Small Be: The Compound Eye of the Parasitoid Wasp Trichogramma evanescens (Westwood, 1833) (Hymenoptera, Hexapoda), an Insect of 0.3- to 0.4-Mm Total Body Size. Vis. Neurosci. 2011, 28, 295–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polilov, A.A. Anatomy of Adult Megaphragma (Hymenoptera: Trichogrammatidae), One of the Smallest Insects, and New Insight into Insect Miniaturization. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0175566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warrant, E.; Kelber, A.; Kristensen, N.P. Eyes and Vision. In Band 4: Arthropoda, 2 Hälfte: Insecta, Lepidoptera, Moths and Butterflies, Teilband/Part 36, Vol 2: Morphology, Physiology, and Development; DE GRUYTER: Berlin, Germany, 2003; pp. 325–360. [Google Scholar]

- Olberg, R.M.; Seaman, R.C.; Coats, M.I.; Henry, A.F. Eye Movements and Target Fixation during Dragonfly Prey-Interception Flights. J. Comp. Physiol. A 2007, 193, 685–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kittelmann, M.; McGregor, A.P. Looking across the Gap: Understanding the Evolution of Eyes and Vision among Insects. BioEssays 2024, 46, e2300240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buschbeck, E.K.; Friedrich, M. Evolution of Insect Eyes: Tales of Ancient Heritage, Deconstruction, Reconstruction, Remodeling, and Recycling. Evol. Educ. Outreach 2008, 1, 448–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giglio, A.; Vommaro, M.L.; Agostino, R.G.; Lo, L.K.; Donato, S. Exploring Compound Eyes in Adults of Four Coleopteran Species Using Synchrotron X-Ray Phase-Contrast Microtomography (SR-PhC Micro-CT). Life 2022, 12, 741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paukner, D.; Wildenberg, G.A.; Badalamente, G.S.; Littlewood, P.B.; Kronforst, M.R.; Palmer, S.E.; Kasthuri, N. Synchrotron-source Micro-x-ray Computed Tomography for Examining Butterfly Eyes. Ecol. Evol. 2024, 14, e11137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulus, H.F. Die Feinstruktur Der Stirnaugen Einiger Collembolen (Insecta, Entognatha) und Ihre Bedeutung für Die Stammesgeschichte Der Insekten. J. Zool. Syst. Evol. Res. 1972, 10, 81–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedrich, M. Ancient Mechanisms of Visual Sense Organ Development Based on Comparison of the Gene Networks Controlling Larval Eye, Ocellus, and Compound Eye Specification in Drosophila. Arthropod Struct. Dev. 2006, 35, 357–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Kleef, J.; Berry, R.; Stange, G. Directional Selectivity in the Simple Eye of an Insect. J. Neurosci. 2008, 28, 2845–2855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuller, S.B.; Karpelson, M.; Censi, A.; Ma, K.Y.; Wood, R.J. Controlling Free Flight of a Robotic Fly Using an Onboard Vision Sensor Inspired by Insect Ocelli. J. R. Soc. Interface 2014, 11, 20140281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buschbeck, E.K. Escaping Compound Eye Ancestry: The Evolution of Single-Chamber Eyes in Holometabolous Larvae. J. Exp. Biol. 2014, 217, 2818–2824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beutel, R.G.; Goczał, J.; Pohl, H. Evolutionary Adaptations in Larvae of Holometabola. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2025, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Friedrich, M. The Tribolium Homologue of Glass and the Evolution of Insect Larval Eyes. Dev. Biol. 2004, 269, 36–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, S.; Laue, M.; Müller, C.H.G.; Meinertzhagen, I.A.; Pohl, H. Ultrastructural 3D Reconstruction of the Smallest Known Insect Photoreceptors: The Stemmata of a First Instar Larva of Strepsiptera (Hexapoda). Arthropod Struct. Dev. 2021, 62, 101055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, C. Form and Function of Stemmata in Larvae of Holometabolous Insects. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 1994, 39, 323–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer-Rochow, V.B. Structure and Function of the Larval Eye of the Sawfly, Perga. J. Insect Physiol. 1974, 20, 1565–1591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toh, Y.; Mizutani, A. Neural Organization of the Lamina Neuropil of the Larva of the Tiger Beetle (Cicindela chinensis). Cell Tissue Res. 1994, 278, 135–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ichikawa, T.; Tateda, H. Distribution of Color Receptors in the Larval Eyes of Four Species of Lepidoptera. J. Comp. Physiol. A 1982, 149, 317–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stowasser, A.; Rapaport, A.; Layne, J.E.; Morgan, R.C.; Buschbeck, E.K. Biological Bifocal Lenses with Image Separation. Curr. Biol. 2010, 20, 1482–1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, M.; Kimler, K.J.; Leming, M.T.; Hu, X.; Whaley, M.A.; O’Tousa, J.E. Expression and Light-Triggered Movement of Rhodopsins in the Larval Visual System of Mosquitoes. J. Exp. Biol. 2015, 218, 1386–1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsson, D.-E.; Kelber, A. A Functional Analysis of Compound Eye Evolution. Arthropod Struct. Dev. 2007, 36, 373–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strausfeld, N.J.; Ma, X.; Edgecombe, G.D.; Fortey, R.A.; Land, M.F.; Liu, Y.; Cong, P.; Hou, X. Arthropod Eyes: The Early Cambrian Fossil Record and Divergent Evolution of Visual Systems. Arthropod Struct. Dev. 2016, 45, 152–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paterson, J.R.; Edgecombe, G.D.; García-Bellido, D.C. Disparate Compound Eyes of Cambrian Radiodonts Reveal Their Developmental Growth Mode and Diverse Visual Ecology. Sci. Adv. 2020, 6, eabc6721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clarkson, E.N.K.; Levi-Setti, R. Trilobite Eyes and the Optics of Des Cartes and Huygens. Nature 1975, 254, 663–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- French, A.S. The Linear Dynamic Properties of Phototransduction in the Fly Compound Eye. J. Physiol. 1980, 308, 385–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harzsch, S.; Hafner, G. Evolution of Eye Development in Arthropods: Phylogenetic Aspects. Arthropod Struct. Dev. 2006, 35, 319–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ready, D.F.; Hanson, T.E.; Benzer, S. Development of the Drosophila Retina, a Neurocrystalline Lattice. Dev. Biol. 1976, 53, 217–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolff, T.; Ready, D.F. The Beginning of Pattern Formation in the Drosophila Compound Eye: The Morphogenetic Furrow and the Second Mitotic Wave. Development 1991, 113, 841–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedrich, M.; Rambold, I.; Melzer, R.R. The Early Stages of Ommatidial Development in the Flour Beetle Tribolium castaneum (Coleoptera; Tenebrionidae). Dev. Genes Evol. 1996, 206, 136–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafner, G.S.; Tokarski, T.R. Morphogenesis and Pattern Formation in the Retina of the Crayfish Procambarus clarkii. Cell Tissue Res. 1998, 293, 535–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, C.H.G.; Rosenberg, J.; Richter, S.; Meyer-Rochow, V.B. The Compound Eye of Scutigera coleoptrata (Linnaeus, 1758) (Chilopoda: Notostigmophora): An Ultrastructural Reinvestigation That Adds Support to the Mandibulata Concept. Zoomorphology 2003, 122, 191–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misof, B.; Liu, S.; Meusemann, K.; Peters, R.S.; Donath, A.; Mayer, C.; Frandsen, P.B.; Ware, J.; Flouri, T.; Beutel, R.G.; et al. Phylogenomics Resolves the Timing and Pattern of Insect Evolution. Science 2014, 346, 763–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wernet, M.F.; Perry, M.W.; Desplan, C. The Evolutionary Diversity of Insect Retinal Mosaics: Common Design Principles and Emerging Molecular Logic. Trends Genet. 2015, 31, 316–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agi, E.; Langen, M.; Altschuler, S.J.; Wu, L.F.; Zimmermann, T.; Hiesinger, P.R. The Evolution and Development of Neural Superposition. J. Neurogenet. 2014, 28, 216–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feuda, R.; Marlétaz, F.; Bentley, M.A.; Holland, P.W.H. Conservation, Duplication, and Divergence of Five Opsin Genes in Insect Evolution. Genome Biol. Evol. 2016, 8, 579–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Backhaus, W. The Bezold-Brücke Effect in the Color Vision System of the Honeybee. Vis. Res. 1992, 32, 1425–1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackowska, M.; Bao, R.; Liu, Z.; McDonald, E.C.; Cook, T.A.; Friedrich, M. Genomic and Gene Regulatory Signatures of Cryptozoic Adaptation: Loss of Blue Sensitive Photoreceptors through Expansion of Long Wavelength-Opsin Expression in the Red Flour Beetle Tribolium castaneum. Front. Zool. 2007, 4, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivasan, M.V. Honeybees as a Model for the Study of Visually Guided Flight, Navigation, and Biologically Inspired Robotics. Physiol. Rev. 2011, 91, 413–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Land, M.F.; Nilsson, D.-E. Animal Eyes; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Sherk, T.E. Development of the Compound Eyes of Dragonflies (Odonata). III. Adult Compound Eyes. J. Exper-Imental Zool. 1978, 203, 61–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Homberg, U. Sky Compass Orientation in Desert Locusts—Evidence from Field and Laboratory Studies. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 2015, 9, 346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labhart, T. How Polarization-Sensitive Interneurones of Crickets Perform at Low Degrees of Polarization. J. Exp. Biol. 1996, 199, 1467–1475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwind, R. Polarization Vision in Water Insects and Insects Living on a Moist Substrate. J. Comp. Physiol. A 1991, 169, 531–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warrant, E.; Nilsson, D.-E. Invertebrate Vision; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Rossel, S. Binocular Stereopsis in an Insect. Nature 1983, 302, 821–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prete, F.R. The Praying Mantids; Johns Hopkins University Press: Baltimore, MD, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Meyers, R.A. Encyclopedia of Molecular Cell Biology and Molecular Medicine; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, Germany, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Weckstrom, M.; Jarvilehto, M.; Heimonen, K. Spike-like Potentials in the Axons of Nonspiking Photoreceptors. J. Neurophysiol. 1993, 69, 293–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buschbeck, E.K.; Ehmer, B.; Hoy, R.R. The Unusual Visual System of the Strepsiptera: External Eye and Neuropils. J. Comp. Physiol. A 2003, 189, 617–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maksimovic, S.; Layne, J.E.; Buschbeck, E.K. Behavioral Evidence for Within-Eyelet Resolution in Twisted-Winged Insects (Strepsiptera). J. Exp. Biol. 2007, 210, 2819–2828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Backhaus, W. Color Opponent Coding in the Visual System of the Honeybee. Vision Res. 1991, 31, 1381–1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakakuwa, M.; Kurasawa, M.; Giurfa, M.; Arikawa, K. Spectral Heterogeneity of Honeybee Ommatidia. Naturwissenschaften 2005, 92, 464–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warrant, E. Vision in the Dimmest Habitats on Earth. J. Comp. Physiol. A 2004, 190, 765–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arikawa, K.; Mizuno, S.; Kinoshita, M.; Stavenga, D.G. Coexpression of Two Visual Pigments in a Photoreceptor Causes an Abnormally Broad Spectral Sensitivity in the Eye of the Butterfly Papilio Xuthus. J. Neurosci. 2003, 23, 4527–4532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardie, R.C. The Photoreceptor Array of the Dipteran Retina. Trends Neurosci. 1986, 9, 419–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bate, M.; Martinez Arias, A. The Development of Drosophila Melanogaster; Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press: Woodbury, NY, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Warren, J.; Kumar, J.P. Patterning of the Drosophila Retina by the Morphogenetic Furrow. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2023, 11, 1151348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvemini, M.; Mauro, U.; Velaeti, S.; Polito, C.; Saccone, G. A New Minos Vector for Eye-specific Expression of White+ Marker in Ceratitis capitata and in Distantly Related Dipteran Species. Insect Mol. Biol. 2006, 15, 341–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Truman, J.W.; Riddiford, L.M. The Evolution of Insect Metamorphosis: A Developmental and Endocrine View. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2019, 374, 20190070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melzer, R.R.; Paulus, H.F. Evolutionswege Zum Larvalauge Der Insekten -Die Stemmata Der Höheren Dipteren Und Ihre Abwandlung Zum Bolwig-Organ. J. Zool. Syst. Evol. Res. 2009, 27, 200–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, W.; Wan, D.; Yu, X.; Cao, J.; Guo, P.; Li, H.; Han, J. Protein Gq Modulates Termination of Phototransduction and Prevents Retinal Degeneration. J. Biol. Chem. 2012, 287, 13911–13918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macias-Muñoz, A.; Murad, R.; Mortazavi, A. Molecular Evolution and Expression of Opsin Genes in Hydra vulgaris. BMC Genom. 2019, 20, 992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardie, R.C.; Juusola, M. Phototransduction in Drosophila. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2015, 34, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiselev, A.; Subramaniam, S. Activation and Regeneration of Rhodopsin in the Insect Visual Cycle. Science 1994, 266, 1369–1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stavenga, D.G. Insect Retinal Pigments: Spectral Characteristics and Physiological Functions. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 1995, 15, 231–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardie, R.C.; Postma, M. Phototransduction in Microvillar Photoreceptors of Drosophila and Other Invertebrates. In The Senses: A Comprehensive Reference; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2008; Volume 1, pp. 77–130. [Google Scholar]

- Katz, B. Drosophila Photoreceptors and Signaling Mechanisms. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2009, 3, 564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yau, K.-W.; Hardie, R.C. Phototransduction Motifs and Variations. Cell 2009, 139, 246–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulk, A.C.; Phillips-Portillo, J.; Dacks, A.M.; Fellous, J.-M.; Gronenberg, W. The Processing of Color, Motion, and Stimulus Timing Are Anatomically Segregated in the Bumblebee Brain. J. Neurosci. 2008, 28, 6319–6332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koyanagi, M.; Shen, B.; Nagata, T.; Sun, L.; Wada, S.; Kamimura, S.; Kage-Nakadai, E.; Terakita, A. High-Performance Optical Control of GPCR Signaling by Bistable Animal Opsins MosOpn3 and LamPP in a Molecular Property–Dependent Manner. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2022, 119, e2204341119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, G.J.; Lower, S.E.; Suvorov, A.; Bybee, S.M. Molecular Evolution of Phototransduction Pathway Genes in Nocturnal and Diurnal Fireflies (Coleoptera: Lampyridae). Insects 2021, 12, 561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rind, F.C. Recent Advances in Insect Vision in a 3D World: Looming Stimuli and Escape Behaviour. Curr. Opin. Insect Sci. 2024, 63, 101180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warrant, E.J. The Remarkable Visual Capacities of Nocturnal Insects: Vision at the Limits with Small Eyes and Tiny Brains. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2017, 372, 20160063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelber, A.; Balkenius, A.; Warrant, E.J. Scotopic Colour Vision in Nocturnal Hawkmoths. Nature 2002, 419, 922–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warrant, E.; Dacke, M. Vision and Visual Navigation in Nocturnal Insects. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2011, 56, 239–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honkanen, A.; Immonen, E.-V.; Salmela, I.; Heimonen, K.; Weckström, M. Insect Photoreceptor Adaptations to Night Vision. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2017, 372, 20160077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnaitmann, C.; Pagni, M.; Meyer, P.B.; Steinhoff, L.; Oberhauser, V.; Reiff, D.F. Horizontal-Cell like Dm9 Neurons in Drosophila Modulate Photoreceptor Output to Supply Multiple Functions in Early Visual Processing. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2024, 17, 1347540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.-J.; Belušič, G.; Arikawa, K. Chromatic Information Processing in the First Optic Ganglion of the Butterfly Papilio xuthus. J. Comp. Physiol. A 2020, 206, 199–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Kooi, C.J.; Stavenga, D.G.; Arikawa, K.; Belušič, G.; Kelber, A. Evolution of Insect Color Vision: From Spectral Sensitivity to Visual Ecology. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2021, 66, 435–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hassenstein, B.; Reichardt, W. Systemtheoretische Analyse Der Zeit-, Reihenfolgen- Und Vorzeichenauswertung Bei Der Bewegungsperzeption des Rüsselkäfers Chlorophanus. Z. Naturforschung B 1956, 11, 513–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borst, A. Neural Circuits for Motion Vision in the Fly. Cold Spring Harb. Symp. Quant. Biol. 2014, 79, 131–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borst, A.; Drews, M.; Meier, M. The Neural Network behind the Eyes of a Fly. Curr. Opin. Physiol. 2020, 16, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholas, S.; Leibbrandt, R.; Nordström, K. Visual Motion Sensitivity in Descending Neurons in the Hoverfly. J. Comp. Physiol. A 2020, 206, 149–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosner, R.; Tarawneh, G.; Lukyanova, V.; Read, J.C.A. Binocular Responsiveness of Projection Neurons of the Praying Mantis Optic Lobe in the Frontal Visual Field. J. Comp. Physiol. A 2020, 206, 165–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenk, L.M.; Avritzer, S.C.; Weisman, J.L.; Nair, A.; Randt, L.D.; Mohren, T.L.; Siwanowicz, I.; Maimon, G. Muscles That Move the Retina Augment Compound Eye Vision in Drosophila. Nature 2022, 612, 116–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, K.Y.; Frye, M.A. Neuromodulation of Insect Motion Vision. J. Comp. Physiol. A 2020, 206, 125–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gür, B.; Sporar, K.; Lopez-Behling, A.; Silies, M. Distinct Expression of Potassium Channels Regulates Visual Response Properties of Lamina Neurons in Drosophila melanogaster. J. Comp. Physiol. A 2020, 206, 273–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Foquet, B.; Dewell, R.B.; Song, H.; Dierick, H.A.; Gabbiani, F. Molecular Characterization and Distribution of the Voltage-Gated Sodium Channel, Para, in the Brain of the Grasshopper and Vinegar Fly. J. Comp. Physiol. A 2020, 206, 289–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freas, C.A.; Plowes, N.J.R.; Spetch, M.L. Not Just Going with the Flow: Foraging Ants Attend to Polarised Light Even While on the Pheromone Trail. J. Comp. Physiol. A 2019, 205, 755–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dacke, M.; Nordström, P.; Scholtz, C.H. Twilight Orientation to Polarised Light in the Crepuscular Dung Beetle Scarabaeus zambesianus. J. Exp. Biol. 2003, 206, 1535–1543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- el Jundi, B.; Smolka, J.; Baird, E.; Byrne, M.J.; Dacke, M. Diurnal Dung Beetles Use the Intensity Gradient and the Polarization Pattern of the Sky for Orientation. J. Exp. Biol. 2014, 217, 2422–2429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dacke, M.; Baird, E.; Byrne, M.; Scholtz, C.H.; Warrant, E.J. Dung Beetles Use the Milky Way for Orientation. Curr. Biol. 2013, 23, 298–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freas, C.A.; Spetch, M.L. Varieties of Visual Navigation in Insects. Anim. Cogn. 2023, 26, 319–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeil, J.; Narendra, A.; Stürzl, W. Looking and Homing: How Displaced Ants Decide Where to Go. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2014, 369, 20130034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeil, J.; Fleischmann, P.N. The Learning Walks of Ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Myrmecol. News 2019, 29, 93–110. [Google Scholar]

- Egelhaaf, M. Optic Flow Based Spatial Vision in Insects. J. Comp. Physiol. A 2023, 209, 541–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tammero, L.F.; Dickinson, M.H. Collision-Avoidance and Landing Responses Are Mediated by Separate Pathways in the Fruit Fly, Drosophila melanogaster. J. Exp. Biol. 2002, 205, 2785–2798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kern, R.; Boeddeker, N.; Dittmar, L.; Egelhaaf, M. Blowfly Flight Characteristics Are Shaped by Environmental Features and Controlled by Optic Flow Information. J. Exp. Biol. 2012, 215, 2501–2514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivasan, M.V.; Zhang, S.; Altwein, M.; Tautz, J. Honeybee Navigation: Nature and Calibration of the “Odometer”. Science 2000, 287, 851–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Hateren, J.H.; Schilstra, C. Blowfly Flight and Optic Flow: II. Head Movements during Flight. J. Exp. Biol. 1999, 202, 1491–1500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Supple, J.A.; Pinto-Benito, D.; Khoo, C.; Wardill, T.J.; Fabian, S.T.; Liu, M.; Pusdekar, S.; Galeano, D.; Pan, J.; Jiang, S.; et al. Binocular Encoding in the Damselfly Pre-Motor Target Tracking System. Curr. Biol. 2020, 30, 645–656.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lecoeur, J.; Dacke, M.; Floreano, D.; Baird, E. The Role of Optic Flow Pooling in Insect Flight Control in Cluttered Environments. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 7707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsushita, A.; Stewart, F.; Ilić, M.; Chen, P.-J.; Wakita, D.; Miyazaki, N.; Murata, K.; Kinoshita, M.; Belušič, G.; Arikawa, K. Connectome of the Lamina Reveals the Circuit for Early Color Processing in the Visual Pathway of a Butterfly. Curr. Biol. 2022, 32, 2291–2299.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chua, N.J.; Makarova, A.A.; Gunn, P.; Villani, S.; Cohen, B.; Thasin, M.; Wu, J.; Shefter, D.; Pang, S.; Xu, C.S.; et al. A Complete Reconstruction of the Early Visual System of an Adult Insect. Curr. Biol. 2023, 33, 4611–4623.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, M.; Hausmann, A.E.; Alcami, P.; Moest, M.; Roussou, R.; Van Belleghem, S.M.; Wright, D.S.; Kuo, C.-Y.; Lozano-Urrego, D.; Maulana, A.; et al. Adaptive Introgression of a Visual Preference Gene. Science 2024, 383, 1368–1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, R.; Kumawat, M.; Vishvendra; Kumawat, R.; Kumar, R. Advancements in Insect Phototaxis and Its Implications for Pest Management: A Comprehensive Review. Uttar Pradesh J. Zool. 2024, 45, 70–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briscoe, A.D.; Chittka, L. The Evolution of Color Vision in Insects. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2001, 46, 471–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilton, D.P.; Fay, R.W. Air Flow Direction and Velocity in Light Trap Design. Entomol. Exp. Appl. 1972, 15, 377–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglas, A.; Burkett, J.F.B. Laboratory Evaluation of Colored Light as an Attractant for Female Aedes aegypti, Aedes albopictus, Anopheles quadrimaculatus, and Culex nigripalpus. Fla. Entomol. 2005, 88, 383–389. [Google Scholar]

- Mellor, H.E.; Hamilton, J.G.C. Navigation of Lutzomyia longipalpis (Diptera: Psychodidae) under Dusk or Starlight Conditions. Bull. Entomol. Res. 2003, 93, 315–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paryavi, M.; Weiser, K.; Melzer, M.; Crook, D.; Ramadugu, C.; Jenkins, D.M. Programmable LED Array for Evaluating Artificial Light Sources to Improve Insect Trapping. Insects 2025, 16, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, H.S.; Robb, K.L. Effects of Ultraviolet-Absorbing Greenhouse Plastic Films on Flight Behavior of Bemisia argentifolii (Homoptera: Aleyrodidae) and Frankliniella occidentalis (Thysanoptera: Thripidae). J. Econ. Entomol. 1999, 92, 557–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antignus, Y.; Nestel, D.; Cohen, S.; Lapidot, M. Ultraviolet-Deficient Greenhouse Environment Affects Whitefly Attraction and Flight-Behavior. Environ. Entomol. 2001, 30, 394–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.; Poehling, H.-M. Uv-Blocking Plastic Films and Nets Influence Vectors and Virus Transmission on Greenhouse Tomatoes in the Humid Tropics. Environ. Entomol. 2006, 35, 1069–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caves, E.M.; Brandley, N.C.; Johnsen, S. Visual Acuity and the Evolution of Signals. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2018, 33, 358–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santer, R.D.; Allen, W.L. Optimising the Colour of Traps Requires an Insect’s Eye View. Pest Manag. Sci. 2024, 80, 931–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santer, R.D.; Okal, M.N.; Esterhuizen, J.; Torr, S.J. Evaluation of Improved Coloured Targets to Control Riverine Tsetse in East Africa: A Bayesian Approach. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2021, 15, e0009463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dearden, A.E.; Wood, M.J.; Frend, H.O.; Butt, T.M.; Allen, W.L. Visual Modelling Can Optimise the Appearance and Capture Efficiency of Sticky Traps Used to Manage Insect Pests. J. Pest Sci. 2024, 97, 469–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meglič, A.; Ilić, M.; Pirih, P.; Škorjanc, A.; Wehling, M.F.; Kreft, M.; Belušič, G. Horsefly Object-Directed Polarotaxis Is Mediated by a Stochastically Distributed Ommatidial Subtype in the Ventral Retina. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 21843–21853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keller, M.D.; Norton, B.J.; Farrar, D.J.; Rutschman, P.; Marvit, M.; Makagon, A. Optical Tracking and Laser-Induced Mortality of Insects during Flight. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 14795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patt, J.M.; Makagon, A.; Norton, B.; Marvit, M.; Rutschman, P.; Neligeorge, M.; Salesin, J. An Optical System to Detect, Surveil, and Kill Flying Insect Vectors of Human and Crop Pathogens. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 8174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, N. Insecticide Resistance in Mosquitoes: Impact, Mechanisms, and Research Directions. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2015, 60, 537–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benelli, G.; Beier, J.C. Current Vector Control Challenges in the Fight against Malaria. Acta Trop. 2017, 174, 91–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blake, A.J.; Riffell, J.A. Spectral Preferences of Mosquitos Are Altered by Odors. J. Exp. Biol. 2025, 228, 250318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preti, M.; Verheggen, F.; Angeli, S. Insect Pest Monitoring with Camera-Equipped Traps: Strengths and Limitations. J. Pest Sci. 2021, 94, 203–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]