Simple Summary

Lepidoptera (butterflies and moths) are among the most diverse yet most threatened groups of organisms in Europe. They play vital ecological roles as pollinators, decomposers, and an important food source for many species, and are often used as indicators in conservation assessments. In this study, we present the first comprehensive reassessment of the Lepidoptera fauna of Cyprus. Our analysis is supported by DNA barcode data covering approximately half of all recorded species. The discovery of more than 100 newly recorded species, over 100 currently unidentified taxa, and more than 10% misidentifications in the previous literature highlights major gaps in the existing faunal inventory. These findings underline the urgent need for comprehensive DNA barcode reference libraries and continued taxonomic revisions to ensure an accurate understanding of the island’s Lepidoptera diversity.

Abstract

This study presents the first comprehensive molecular analysis of the Lepidoptera fauna of Cyprus based on DNA barcoding. A total of 1859 DNA barcode sequences were generated, representing 701 Barcode Index Numbers (BINs) and thus putative species. Morphological examination enabled the assignment of 596 BINs to 580 Linnaean species. Based on this genetically validated species inventory—complemented by morphologically examined specimens and a critical review of the literature—a new checklist for the Lepidoptera of Cyprus is provided. In total, 1213 species are accepted as confirmed or considered likely based on published but unverified records. The checklist includes 57 genetically confirmed first records for Cyprus and 62 new records supported solely by morphology. Remarkably, 10 species are recorded as new to Europe: Alloclita deprinsi, Cochylimorpha diana, C. additana, Pammene avetianae, P. nannodes, Cydia alienana, Ephestia abnormalella, Hypsotropa paucipunctella, Dysauxes parvigutta, and Bryophilopsis roederi. In addition, 105 BINs could not be assigned to a species. Preliminary morphological assessment indicates that many of these represent cryptic taxa or belong to taxonomically unresolved species complexes. Furthermore, 35 morphology-based records could be identified at best to the genus level. The study also lists 158 previously published species that are now considered likely misidentifications and therefore excluded from the Cypriot fauna.

1. Introduction

Cyprus, with an area of 9251 km2, is the third-largest island in the Mediterranean, after Sardinia and Sicily. It is located in the eastern part of the Mediterranean basin, with a maximum east–west extent of 225 km and a north–south width of 90 km. Although the climate of Cyprus is influenced by its geographical position, it can generally be characterized as Mediterranean. Its main features are a short, mild, and rainy winter, and a long, hot summer [1].

The island is composed of four geological zones: (a) the Troodos Geotectonic Zone, (b) the Mamonia Geotectonic Zone, (c) the Kyrenia Geotectonic Zone, and (d) the Circum Troodos zone including the Mesaoria Plain. The 92-million-year-old ophiolitic rocks of the Troodos Zone, which represent a section of the oceanic crust and extend beneath the Mesaoria Plain, form the core of this geotectonic unit. These mountains reach heights of nearly 2000 m. The Mamonia Geotectonic Zone consists of allochthonous igneous rocks (serpentinites, pillow lavas), sedimentary rocks (sandstones, siltstones, mudstones), and, to a lesser extent, metamorphic rocks (recrystallised limestones, schists), ranging in age from 210 to 95 million years. The northernmost geomorphological unit of Cyprus is the Kyrenia Geotectonic Zone, characterised by a narrow, steep limestone mountain range reaching a maximum height of approximately 1000 m and extending from the Apostolos Andreas area in the east to the Kormakitis region in the west. Finally, the Circum Troodos zone, situated between the Troodos and Kyrenia mountains, is dominated by autochthonous sedimentary rocks of various origin. The Mesaoria Plain evolved mainly in the Quarternary and formed a land connection between the formerly separated mountain ranges [2].

The biogeography of Cyprus is shaped by its unique geographical position at the crossroads of Europe, Asia, and Africa. The island’s flora and fauna exhibit a pronounced Levantine character. At the same time, the strong European–Mediterranean influence and the island’s prolonged isolation have contributed significantly to the evolution of numerous endemic taxa. Consequently, Cyprus harbours one of the most diverse floras in the Mediterranean region relative to its size. A total of 1649 indigenous and 276 introduced taxa (species and subspecies) have been recorded to date [3]. Furthermore, both the flora and fauna of Cyprus are exceptionally rich in endemic species. Among plants, endemics account for approximately 7.4% of the native taxa. Several endemic vertebrates have also been recorded on the island, including the Cyprus Mouse (Mus cypriacus), the Cyprus Spiny Mouse (Acomys nesiotes), the Cyprus Warbler (Curruca melanothorax), the Cyprus Wheatear (Oenanthe cypriaca), and the Cyprus Scops Owl (Otus cyprius). Particularly noteworthy, however, is the remarkable number of endemic insect species found among the estimated 6000 insect taxa occurring on the island [4,5].

The island’s diverse topography and high species richness are reflected in the remarkable variety of its habitat types. The riparian vegetation of oriental plane and alder, the endemic cedar forest, the cypress forests, and the relic forests of Cyprus oak are local formations. The extensive pine forests, sclerophyllous evergreen vegetation, high and low maquis, as well as garigue and phrygana, constitute the dominant woody vegetation types. Herbaceous vegetation mainly consists of grasslands, vegetation of sand dunes and cliffs, and plants typical of temporary ponds. Finally, in the high-altitude areas, scree slopes and rocky habitats with a xeromontane character are found, where vegetation is only sparsely developed (Figure 1, Figure 2, Figure 3, Figure 4 and Figure 5).

Cyprus is politically divided into several zones: the northern part (approximately 36% of the island) is administered by the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus, while the southern part (approximately 58%) is governed by the Republic of Cyprus. In addition, there are two British Sovereign Base Areas (approximately 2.8%) and a United Nations buffer zone separating the northern and southern parts of the island. However, this complex political situation is disregarded here, and the island is considered as a whole.

The lepidopteran fauna of Cyprus attracted the attention of scientists early on. The first sampling dates back to the mid-19th century, but remained rudimentary in scope, with only 91 species with few additions during the following decades [6,7]. More comprehensive studies were not carried out until after the British occupation of the island and the accompanying increased interest of researchers from the British Empire [8,9,10]. As in the case of Crete and several regions of the Balkan Peninsula, Hans Rebel (1861–1940), an Austrian lepidopterist and long-serving director of the Natural History Museum in Vienna, was the first to provide an overview of the Lepidoptera fauna of Cyprus in 1916 [11]. His study listed a total of only 166 species, which he estimated to represent approximately one-eighth of the island’s actual fauna. In the first and so far only comprehensive account of the Cypriot Lepidoptera, published in 1939, the number of recorded species had already increased to 482 [12]. Further significant advances were made especially by Edward Parr Wiltshire (1910–2004) and Hans Georg Amsel (1905–1999) in the mid-20th century [13,14], whereas later decades yielded relatively fewer, more targeted contributions, such as species descriptions and studies on economically relevant species [15,16,17,18,19]. It was not until the 1980s that the lepidopteran fauna of Cyprus was again surveyed more systematically. Here it is primarily owing to the work of the Austrian lepidopterists Ernst Arenberger (1933–2020) and Josef Wimmer (1935–2016) that the remarkable diversity of microlepidoptera in Cyprus was investigated in depth and comprehensively documented for the first time [20,21,22,23]. In particular, Arenberger’s first comprehensive work in 1994 more than doubled the species number in these families, reaching a total of 461 species [20]. Further important faunistic additions to microlepidoptera were made by authors of this study through their own sampling [24,25,26]. Numerous faunistic and taxonomically relevant studies on macrolepidoptera were published, particularly toward the end of the 20th century [27,28,29,30,31,32,33]. A summary of the knowledge on most diverse families of larger moths and butterflies was provided by the German lepidopterists Fischer and Lewandowski [34,35,36], as well as in a comprehensive monograph on the butterflies of Cyprus by Manil [37]. However, since Rebel’s time, no comprehensive inventory of the total Lepidoptera fauna of Cyprus has been attempted. The now-defunct Fauna Europaea database, which is still fully accessible through the PESI platform and integrated into Lepiforum, provided a complete species list, but frequently lacked references and contained numerous errors [38,39]. An effort by the renowned Hungarian lepidopterist László Gozmány (1921–2006) to compile a comprehensive inventory of the Lepidoptera of Greece and Cyprus was discontinued after the first volume due to his death [40]. The issue of insufficient faunistic and taxonomic data therefore remains highly relevant. This situation is further exacerbated by the fact that the island’s fauna has so far been studied almost exclusively using classical, mostly morphological methods, which in many cases do not allow for reliable species delimitation. A more integrative approach incorporating molecular data has been applied only in a few exceptional cases [41,42,43,44,45,46].

Figure 1.

Eastern part of the Troodos Mountains (Adelfoi), characterized by extensive scree slopes (Photo E. Friedrich).

Figure 1.

Eastern part of the Troodos Mountains (Adelfoi), characterized by extensive scree slopes (Photo E. Friedrich).

Figure 2.

The formerly extensive pine and deciduous forests are today largely confined to the Troodos Mountains or, as shown here, to the Pentadaktylos Mountains (Photo P. Huemer).

Figure 2.

The formerly extensive pine and deciduous forests are today largely confined to the Troodos Mountains or, as shown here, to the Pentadaktylos Mountains (Photo P. Huemer).

Figure 3.

Wetland habitat near the Diarizos River, Nikokleia (Photo E. Friedrich).

Figure 3.

Wetland habitat near the Diarizos River, Nikokleia (Photo E. Friedrich).

Figure 4.

Salt marshes at Akrotiri, near Limassol (Photo E. Friedrich).

Figure 4.

Salt marshes at Akrotiri, near Limassol (Photo E. Friedrich).

Figure 5.

Well-preserved, unspoiled sand dunes are found particularly along the northern coast near Dipkarpaz (Photo P. Huemer).

Figure 5.

Well-preserved, unspoiled sand dunes are found particularly along the northern coast near Dipkarpaz (Photo P. Huemer).

To address these substantial deficiencies, a joint research project initiated by Near East University (ÖÖ) and the Tyrolean State Museums (PH) aimed, for the first time, to genetically document as many species as possible using DNA barcoding [26]. The inclusion of extensive recent collections by several colleagues, digital observation data, and the critical reassessment of earlier publications now makes it possible—despite remaining gaps and unresolved taxonomic problems—to compile, for the first time, a well-founded inventory of the island’s Lepidoptera fauna.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Field Surveys

Field surveys were primarily based on intensive fieldwork conducted by the authors PH, IB, and JJ in Cyprus. In north Cyprus, comprehensive sampling was carried out by PH with support from ÖÖ during five excursions between autumn 2023 and 2025, with the primary objective of obtaining genetic sequences for all accessible species, except for the Papilionoidea, which have already been extensively studied on the island (Figure 6 and Figure 7). In contrast, the Lepidoptera of the southern part of the island were surveyed over more than two decades by IB and JJ, supported by the sampling efforts of numerous other lepidopterists. These surveys were performed in an unsystematic manner, i.e., without a clearly defined sampling protocol. Furthermore, only a limited subset of species has been genetically analyzed to date, and several additional unpublished faunistic records are therefore provided in Table S1 as a reference for future studies. Nevertheless, the overarching goal was to achieve the most complete possible documentation of the local fauna, albeit without a specific emphasis on subsequent genetic analyses.

To ensure a representative inventory, the main habitats of Cyprus were sampled throughout all seasons. Lepidoptera-specific sampling methods were applied as required. Surveys of the particularly diverse nocturnal families were conducted primarily using various light sources and, less frequently, alternative methods such as bait traps or vegetation beating. Diurnal species and preimaginal stages were sampled through visual searches, netting, or pheromone traps.

Specimens were collected as needed, treated with acetic ether or comparable narcotizing agents, and, in most cases, immediately pinned, spread, and dried in the field (PH), or pinned and later softened and properly mounted by the other authors. Preimaginal stages were reared in the authors’ laboratories, and upon adult emergence, specimens were treated in the same manner.

Figure 6.

Recent surveys in Northern Cyprus focused primarily on the Pentadaktylos Mountains (Photo P. Huemer).

Figure 6.

Recent surveys in Northern Cyprus focused primarily on the Pentadaktylos Mountains (Photo P. Huemer).

Figure 7.

One of the main methods for sampling nocturnal moths was the use of various light sources (Photo P. Huemer).

Figure 7.

One of the main methods for sampling nocturnal moths was the use of various light sources (Photo P. Huemer).

2.2. DNA Barcoding

Tissue samples (dried legs) from 1349 specimens from the Tyrolean State Museum (TLMF) and provisionally identified to the morphospecies level were prepared according to standard protocols to obtain DNA barcode sequences of the mitochondrial COI gene (cytochrome c oxidase I). The material was processed at the Centre for Biodiversity Genomics (University of Guelph, Guelph, ON, Canada) using a standard high-throughput workflow [47]. The remaining 689 specimens, most of which were already publicly available in the Barcode of Life Data System (BOLD) [48], originated from several additional collections, primarily the Zoologische Staatssammlung München (ZSM; 154 specimens), the Finnish Museum of Natural History (FMNH, Helsinki; 87 specimens), the Zoological Museum of the University of Oulu (ZMUO; 87 specimens), and especially leafminers were sequenced at Naturalis Biodiversity Center, Leiden (RMNH, 35 specimens). Part of this material was processed within the framework of the Biodiversity Genomics Europe (BGE) project using the corresponding protocol as described in [49].

Details, including complete voucher information and specimen images, are available in the public dataset “Barcoding Lepidoptera of Cyprus” (https://dx.doi.org/10.5883/DS-LEPICYPR) within the Barcode of Life Data System (BOLD). With the exception of ten public sequences, all relevant data are included in this resource.

All sequences were assigned to Barcode Index Numbers (BINs), an algorithm-based approach to delineate operational taxonomic units that provide a good proxy for species—which were automatically calculated for records in BOLD that were compliant with the DNA barcode standard [50]. A few BINs included specimens belonging to more than one taxon because of BIN sharing, misidentifications, or contaminations. Identification was based on external morphology and, in critical cases, on genitalia morphology. In the case of BINs attributed to a single Linnean name, these were accepted as correct although misidentifications cannot be ruled out.

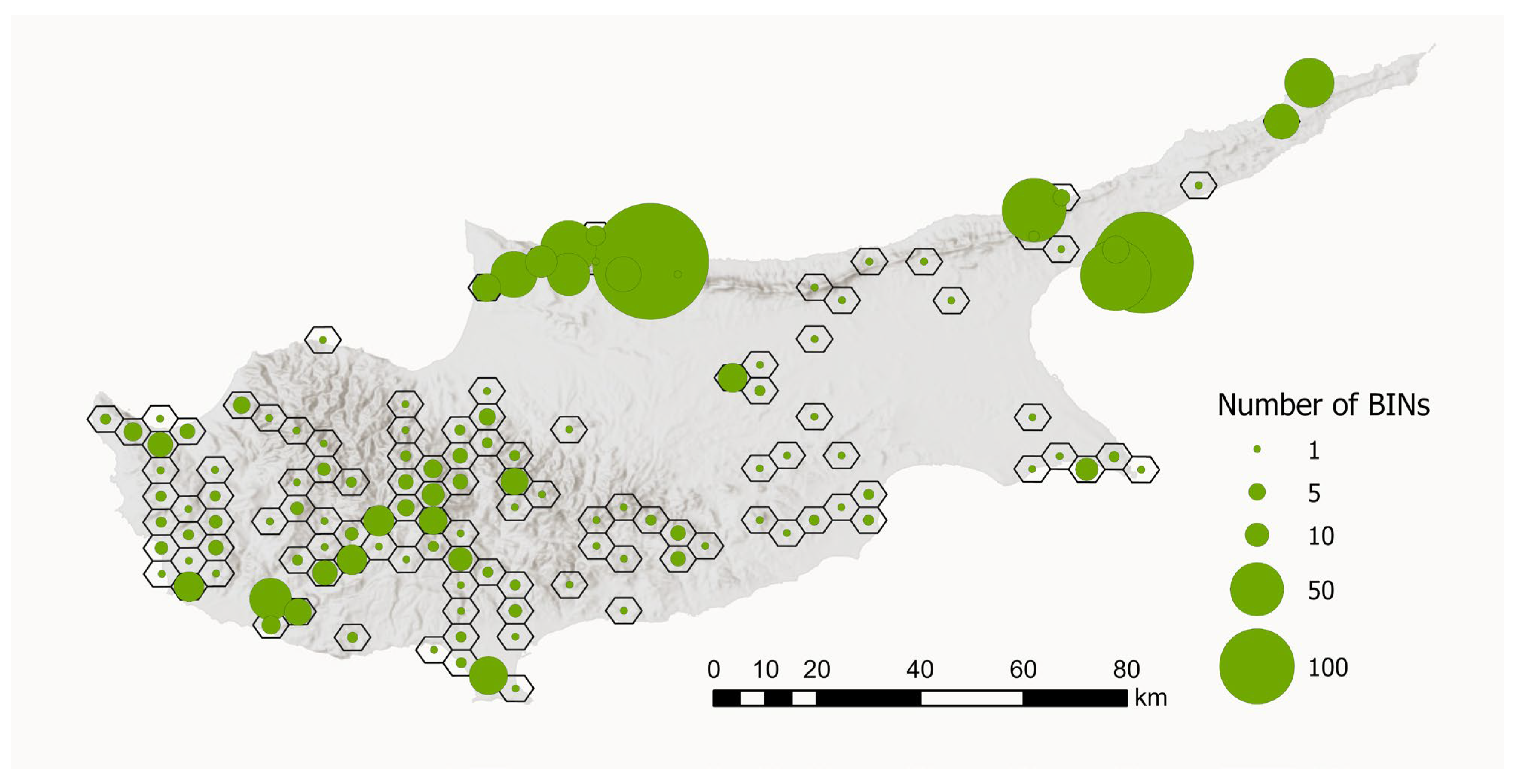

To visualise the geographical distribution of the BIN samples, we created a map showing the number of BINs per sampling site. To improve visualisation and account for sampling sites that were very close together, we aggregated sites within hexagons with a diameter of 5 km. This aggregation resulted in 130 hexagons. The number of unique BINs per 5 km hexagon ranged from 1 to 239 (see Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Number of BINs per sampling region in Cyprus. Sampling sites that were close together were aggregated within hexagons with a diameter of 5 km (n = 130). The size of the circles indicates the number of BINs. Map data source: ESRI, USGS, Statistical Service of Cyprus.

2.3. Checklist

The checklist of the Lepidoptera of Cyprus is primarily based on the national fauna database provided by Lepiforum, which already incorporates a large proportion of published species records. The taxonomic arrangement and nomenclature follow this online resource as well, except for a few disputed genera and subgenera of the Noctuidae. Synonyms and subspecies were deliberately excluded.

By critically reviewing additional literature and data sources not previously included in Lepiforum, several further species were added to the checklist. Moreover, a substantial number of species, confirmed morphologically and/or genetically from our own sampling, were recorded for the first time in Cyprus and incorporated into the faunal inventory. In addition, a large number of previously published species were sampled in this study and the corresponding detailed data are presented here. The checklist additionally includes information on BINs and the occurrence status of individual species in Cyprus. Furthermore, relevant bibliographic references are provided which, with the exception of the endemic taxa, are largely based on comprehensive summary works.

Taxa that can currently be identified only to the genus level based on genetic data and/or morphological analyses are not included in the main checklist. In addition, misidentifications resulting from various errors, as well as highly questionable species, were excluded from the island’s fauna.

3. Results

3.1. DNA Barcodes—General Overview

The analysis of tissue samples from 2042 specimens yielded 1859 DNA barcode sequences, representing approximately 50% of the Lepidoptera fauna of Cyprus. Full DNA barcodes (658 bp) without stop codons were recovered for 1455 specimens, while only 31 specimens had a sequence shorter than 500 bp. Finally, sequencing failed for 174 specimens. Sequences clustered into 701 BINs (Figure 8).

The historically divergent sampling strategies and the associated processing of specimens resulted in a pronounced bias in the dataset, with a clear predominance of both samples and BINs from north Cyprus (Figure 8). DNA barcodes are available for nearly all recorded species from this region, whereas data from the southern part of the island is fragmentary.

3.2. BINs Attributed to Linnaean Names

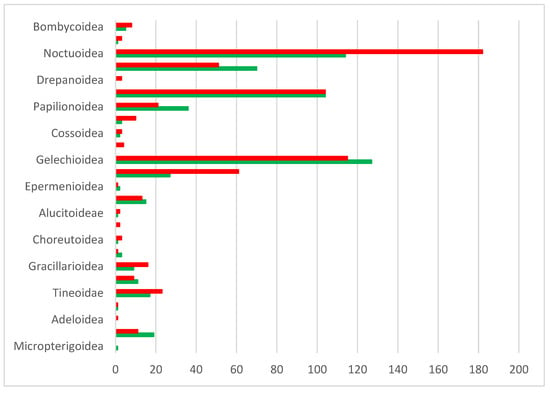

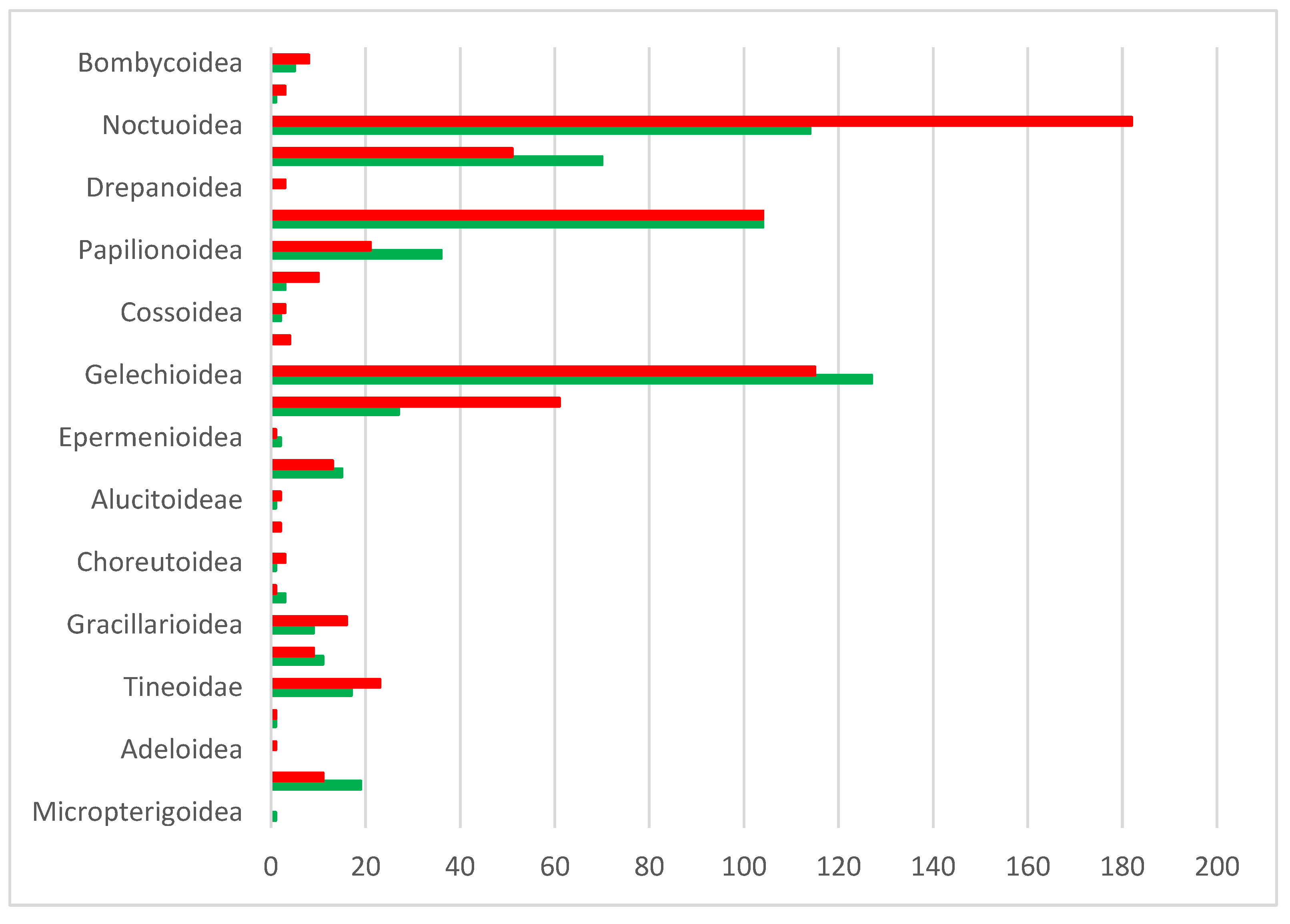

BOLD analytical tools assigned species-level identifications to 596 BINs, corresponding to 580 Linnean names (Table S1). Sequences for five additional species either lacked a BIN or had a BIN pending. The genetic coverage of the Linnaean species inventory based on BINs is approximately 48% overall but varies considerably among the major systematic groups (superfamilies). Eleven of 25 superfamilies have barcode coverage for more than half their component species, but two species-rich taxa (Noctuoidea, Tortricoidea) fail to meet this mark. A similar situation applies—despite a comparatively higher BIN coverage—to the diverse superfamilies Pyraloidea, Gelechioidea, and Geometroidea (see Figure 9).

Fourteen species were assigned to two BINs, including Ateliotum arenbergeri, Tecmerium perplexum, Cydia fagiglandana, Agdistis tamaricis, Stenoptilia aridus, Maniola cypricola, and Hipparchia syriaca, while Acalypris pistaciae and Symmoca salem were assigned to three BINs. Such cases may reflect deep intraspecific variability in the DNA barcode, as observed in Cydia fagiglandana and Tecmerium perplexum, species for which extensive genital morphological studies revealed no evidence of overlooked diversity. In other cases, introgression may explain strongly divergent genetic clusters. For example, one specimen of Hipparchia syriaca clustered with Hipparchia alcyone, a species not yet recorded anywhere in Southeastern Europe or the Near East. Genital morphology, however, unequivocally confirms the specimen as H. syriaca. It is also possible that cryptic diversity exists in some taxa with deep barcode divergence, but these taxa await investigation. In contrast, only four species in Cyprus— all belonging to the genus Agonopterix—share the same BIN.

A total of 109 species exhibit a unique BIN within the BOLD database, including two pairs of variable species (four species in total) represented by two or three BINs in Cyprus. In most cases, these endemic BIN members correspond to true island endemics. Other, more widely distributed species show only relatively minor divergence from their Linnaean counterparts—typically around 2%—despite being placed in different BINs are treated as one species when no clear morphological differences are apparent. Examples include Metzneria artificella, Scrobipalpa bigoti, Mirificarma eburnella, Pyralis kacheticalis, and Capperia celeusi. Finally, the group of endemic BINs also includes several highly divergent subspecies.

Many species cluster into multiple BINs across their European range, but the Cypriot fauna often exhibits clear affinities with extra-European clusters, primarily from the Near East or the Levantine region. Notable examples include Zeuzera pyrina, Scythris mus, Pararge aegeria, Amephana dalmatica, and Amphipyra micans. All these taxa require a comprehensive morphological analysis and comparisons with potentially relevant Linnaean species, ideally based on a study of the type material. While minor genetic divergences are temporarily attributed to the nominate species, strongly divergent clusters (>3%) are provisionally assigned to currently unidentified species (Table S2). An exception is Pachythelia villosella quadratica de Freina, 1983, which, with a genetic divergence of more than 5%, is likely to represent a distinct species but is still listed under the name of the nominotypical subspecies; and further three species of Nepticulidae that are highly variable in barcodes, but morphologically inseparable from other populations.

Figure 9.

Number of Linnaean species per superfamily in Cyprus (systematic order), with BIN coverage (green) and without BIN (red). BINs without a species assignment were excluded.

Figure 9.

Number of Linnaean species per superfamily in Cyprus (systematic order), with BIN coverage (green) and without BIN (red). BINs without a species assignment were excluded.

3.3. New Faunistic Records

3.3.1. New Records with Accompanying DNA Barcodes

In total, 57 Lepidoptera species belonging to 21 families were newly recorded for Cyprus through this study, based in part on their DNA barcodes (Table 1). These additions expand the known faunal inventory and provide a genetic reference for future taxonomic and biodiversity research. Detailed collection information and sequences are available in the dataset “Barcoding Lepidoptera of Cyprus” (https://dx.doi.org/10.5883/DS-LEPICYPR; see Table S3). For several of these species, additional unsequenced voucher material is preserved in the collections of TLMF, the Cyprus Herbarium and Natural History Museum, Nicosia (CHNHM), JJ, and IB. In some cases, photographic records are also available on online platforms.

Table 1.

A total of 57 species newly recorded for the fauna of Cyprus largely based on DNA barcodes.

The list includes five noteworthy new records for Europe, namely Alloclita deprinsi, Cochylimorpha additana, Cydia alienana, Ephestia abnormalella, and Hypsotropa paucipunctella.

3.3.2. New Records Based on Morphology

A total of 62 species representing 20 families were newly recorded from Cyprus through morphological examination. Most identifications were confirmed from voucher specimens based on both external morphology and genitalia dissections. In contrast, five species—Bifasciodes leucomelanella, Watsonalla uncinula, Bryophilopsis roederi, Xanthodes albago, and Aphomia sabella—were identified solely from live photographs posted on online forums, without voucher specimens. Fife species—Bryophilopsis roederi, Cochylimorpha diana, Pammene avetianae, Pammene nannodes, and Dysauxes parvigutta—constitute first records for Europe (Table 2; label data in Table S4).

Table 2.

A total of 62 new faunistic records from Cyprus, based solely on morphological evidence. Species identifications derived from online forums, based exclusively on photographs and lacking voucher specimens, are marked with an asterisk (*).

3.4. Unidentified Species—Potential Cryptic Diversity

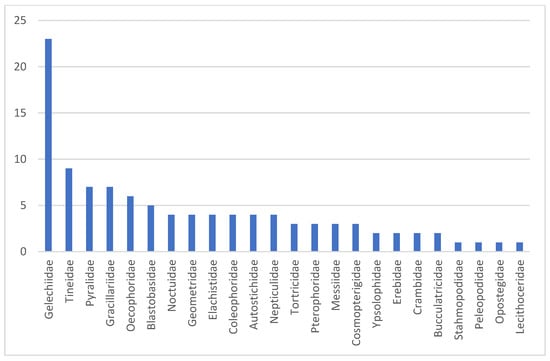

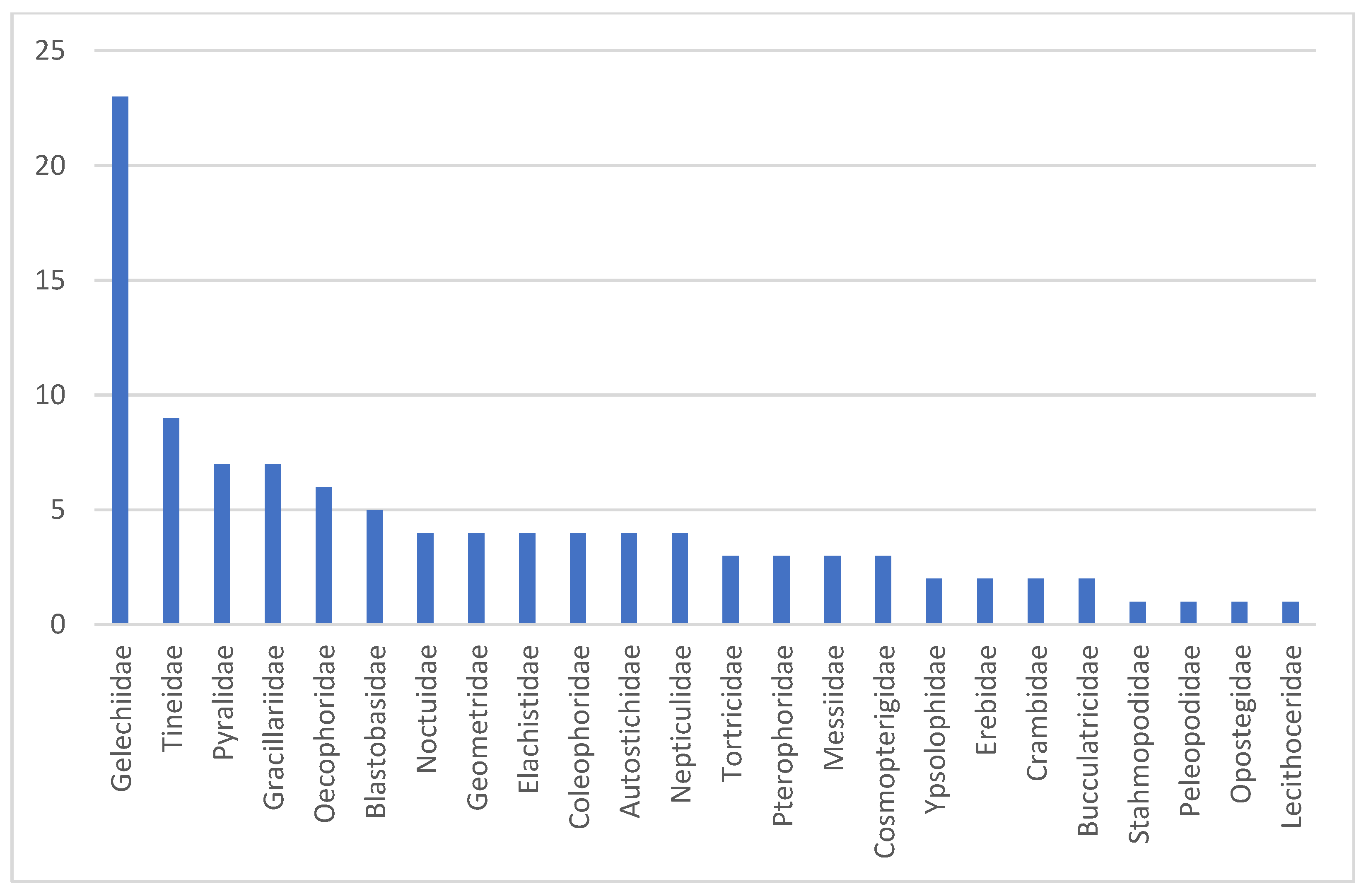

3.4.1. Unidentfied BINs

A total of 105 Barcode Index Numbers (BINs) could not be assigned to any Linnaean species, even after preliminary morphological analyses, due to the absence of reference sequences in BOLD. Of these, 68 BINs are currently known exclusively from Cyprus, while the remaining BINs were already on BOLD but not classified at the species level. While two tineid BINs could only be identified to the family level, the remaining BINs were assigned to a genus (Table S2). Images of the relevant species can be found at https://dx.doi.org/10.5883/DS-LEPICYPR.

The BINs that cannot be assigned to species level are distributed very unevenly across 24 families (Figure 10). The number of unidentified BINs is, by far, the highest in Gelechiidae, but also other microlepidopteran families (Tineidae, Pyralidae, Oecophoridae, Gracillariidae) include multiple unknowns (Figure 10). In some families, such as the Tineidae, the currently limited coverage in BOLD constrains species assignment, whereas this is far less the case in Gelechiidae, suggesting the presence of several undescribed species in Cyprus [51]. The genetic distances to the nearest neighbor in BOLD also vary greatly, ranging from only 1.12% to 11.24%. The particularly low divergences, however, refer to unnamed reference sequences in BOLD. For 60 BINs, the distance to the nearest neighbor exceeds 3%.

The unassigned BINs belong either to insufficiently revised species complexes or to taxa lacking adequate documentation, for instance due to missing illustrations or superficial original descriptions. Further integrative taxonomic studies—combining morphological, genetic, and ecological data—are essential to resolve these cases. The following examples illustrate the complexity and taxonomic challenges associated with some of these unassigned taxa.

Oegoconia sp. (Autostichidae)

The taxon identified as O. deauratella is represented in Cyprus by three endemic Barcode Index Numbers (BOLD:ADF0714, BOLD:AGP5600, and BOLD:AHC3739), which show very low intraspecific variation. In contrast, these BINs exhibit substantial genetic divergence (>5%) from O. deauratella sensu stricto [24]. This evidence suggests the presence of an undescribed, genetically variable species endemic to Cyprus.

Lecithocera sp. (Lecithoceridae)

Barton reported L. anatolica, originally described from Türkiye, as a new record for Cyprus [25]. His identification was based on a previously undescribed female of the species, which was determined using comparative material of both sexes from Israel [52]. However, the species assignment remains uncertain due to the absence of a direct comparison with the type material. Examination of the male genitalia of an independently collected specimen by JJ did not allow confident identification based on the schematic illustrations provided by Gozmány [53].

Isophrictis spp. (Gelechiidae)

The genus Isophrictis is in urgent need of taxonomic revision. The four BINs recorded from Cyprus exhibit only minor genetic divergence (<2%) from their nearest neighbours. However, with one exception, they cannot currently be assigned to a species with confidence. Two BINs (BOLD:AEI4278 and BOLD:AEI4279) are so far known exclusively from Cyprus. The latter is tentatively attributed to I. kefersteiniellus based on its low genetic divergence (1.24%) and phenotypic congruence with that species.

Figure 10.

Number of unassigned BINs per family.

Figure 10.

Number of unassigned BINs per family.

3.4.2. Morphology-Based Unidentified Species

A total of 35 taxa were classified solely on the basis of morphological characteristics but have not yet been identified to species level. Table S5 provides an overview of these taxa together with detailed information on the respective collection circumstances.

3.5. Critical Review of Doubtful or Incorrect Records from Cyprus

Over the long history of studies on the Lepidoptera of Cyprus, many species have been reported whose occurrence on the island is either highly questionable or can be excluded altogether for various reasons. As early as the mid-19th century, Rebel listed numerous doubtful records that have never been reconfirmed [11,12].

Most of these erroneous reports result from the following causes:

- (a)

- misidentifications of voucher specimens or, more recently, photographs;

- (b)

- changes in species concepts;

- (c)

- unresolved genetic divergences indicating overlooked cryptic diversity;

- (d)

- technical errors (e.g., incorrect data tables or specimen mislabelling).

Although examination of the original material was only possible in a few cases, we excluded the doubtful or clearly incorrect records (Table S6) from the checklist—even in the absence of a full revision of the largely inaccessible historical collections. Species records were critically evaluated, particularly when their known distribution or morphological similarity to other taxa made their presence in Cyprus implausible. Most of these species were listed in Fauna Europaea without citation of a primary source, and many of the erroneous records summarized here have already been addressed in previous publications. As a result of this critical assessment, 158 species were ultimately excluded from the faunal list (Table S6). The reasons for the exclusion of species without a current identity assignment (“?” in Table S6) can be found in detail in Lepiforum (Faunistics) and are not repeated here [39].

In addition, several photographic records from iNaturalist [54] were also problematic, particularly when secondarily incorporated—albeit with uncertainty tags—into Lepiforum. Ultimately, several purported new records, including Micropterix aruncella, Stemmatophora combustalis (confirmed, however, by material ex coll. Junnilainen), and Eilema caniola, were corrected on iNaturalist and no longer appear under the originally suggested names. However, since these were user-generated identification proposals rather than formal scientific publications, we have refrained from listing these temporary misidentifications in detail.

3.6. Revised and Updated Checklist

The revised checklist of the Lepidoptera of Cyprus now includes 1213 Linnaean species belonging to 65 families (Table S1). It includes about 1150 native species with established, self-sustaining populations. In contrast, at least 37 alien species are recorded, including 16 confirmed alien species and 21 cryptogenic species referring to taxa of uncertain origin [55,56,57], Table S1. Finally, at least 30 species are categorized as presumably non-resident migratory species, but temporary establishment may be possible for some of them. Conversely, for several native species, sporadic or even regular immigration seems likely. Together with the yet unidentified species, the lepidopteran fauna of Cyprus is likely to include well over 1300 species.

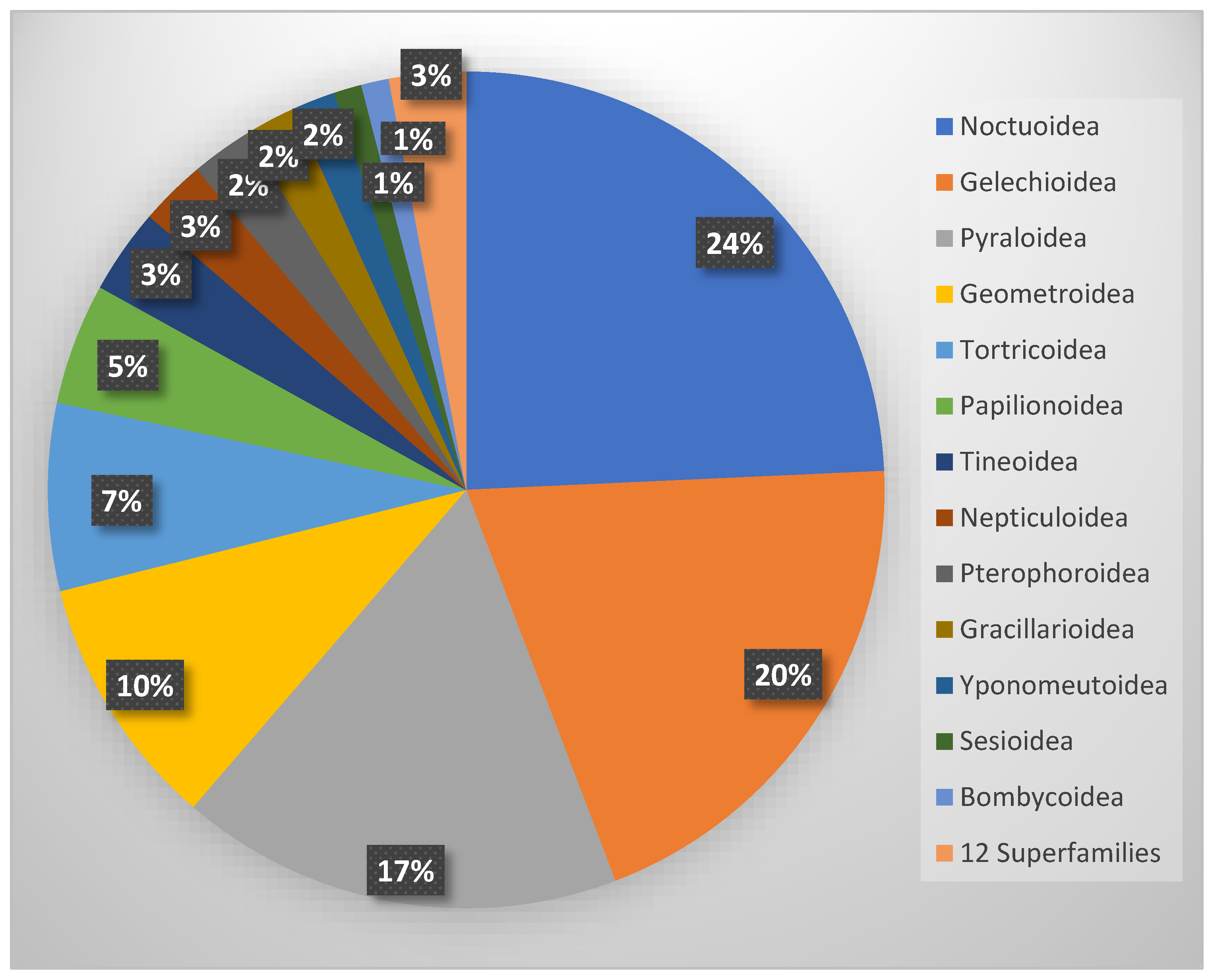

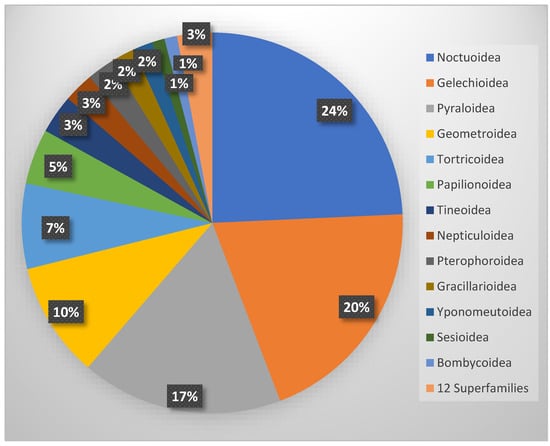

The systematic analysis of the faunal composition reveals a clear dominance of a few highly diverse superfamilies. Of the 25 superfamilies present, the Noctuoidea (295 spp.), Gelechioidea (242 spp.), Pyraloidea (208 spp.), and Geometroidea (119 spp.) are the most species-rich, each comprising more than 100 species, whereas 12 superfamilies are represented by five or fewer species (Figure 11).

Figure 11.

Proportion of superfamilies in the total Lepidoptera fauna of Cyprus.

3.7. Insular Endemism

Cyprus is currently thought to host 55 endemic species (Table S1), but some of them, especially those that are inconspicuous, may well also occur on the mainland, particularly in Turkey and the Levant countries. Conversely, island endemism appears highly probable for numerous phenotypically distinct species, especially butterflies and macro-moths (Macroheterocera) (Figure 12 and Figure 13). Notable examples include Glaucopsyche paphos, Hipparchia cypriensis, Orthostixis cinerea, Nychiodes aphrodite, Pseudoterpna rectistrigaria, Dichagyris endemica, Perigrapha wimmeri, Pseudenargia troodosi and Ammoconia aholai. Interestingly, most of the endemic Noctuoidea are active in autumn or winter and were therefore only discovered and described recently, most within the past 20–30 years.

Endemism is also highly likely for several more conspicuous micro-moth species, such as Micropterix cypriensis and Batia hilszczanskii (Figure 14). The same applies to species with trophic associations to recognized endemic plants, such as Phyllonorycter troodi, which is associated with Quercus alnifolia.

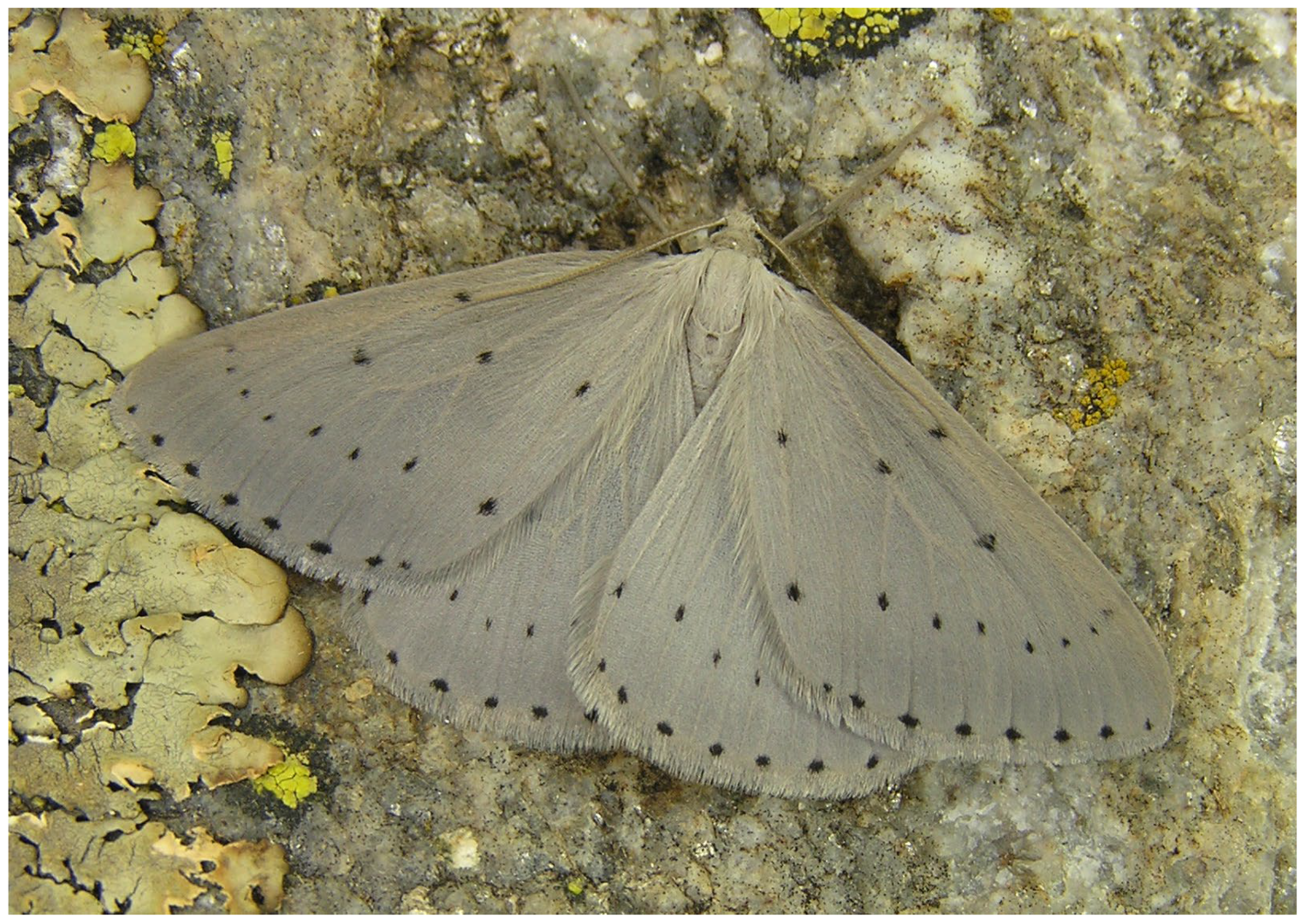

Figure 12.

The endemic Orthostixis cinerea, first described by Rebel in 1916 (Photo E. Friedrich).

Figure 12.

The endemic Orthostixis cinerea, first described by Rebel in 1916 (Photo E. Friedrich).

Figure 13.

Pseudenargia troodosi, one of the several island-endemic species emerging only in autumn (Photo E. Friedrich).

Figure 13.

Pseudenargia troodosi, one of the several island-endemic species emerging only in autumn (Photo E. Friedrich).

Figure 14.

Micropterix cypriensis is an unmistakable endemic species of Cyprus (Photo P. Huemer).

Figure 14.

Micropterix cypriensis is an unmistakable endemic species of Cyprus (Photo P. Huemer).

Genetic data are lacking for many of the numerous endemic subspecies described from Cyprus that may represent valid species. Preliminary molecular results, together with the observed divergences from the nominate subspecies, indicate the need for necessary taxonomic re-evaluations. Examples of such unresolved genetic distances include Synanthedon myopaeformis luctuosa (4.6%), Colotois pennaria paupera (2.94%), Autophila anaphanes cypriaca (1.8%), and Allophyes asiatica cypriaca (2.21%).

4. Discussion

Cyprus has been the subject of lepidopterological investigation and sampling for approximately 170 years, although with varying intensity. Despite this long research history, our study reveals a striking lack of comprehensive and up-to-date faunistic syntheses, as well as the absence of a critical re-evaluation of previously published records. Moreover, genetic analyses—particularly DNA barcoding—have never before been systematically applied to the island’s lepidopteran fauna.

As a result of our integrative approach, a considerable number of species had to be removed from the local faunal list due to insufficient or demonstrably incorrect documentation. At the same time, the revised checklist was substantially enriched by more than 100 newly confirmed Linnean species, verified through genetic and/or morphological evidence. Of these newly confirmed species, 10 also represent first records for Europe. Nevertheless, the current total of approximately 1200 species is likely a considerable underestimate of the actual lepidopteran diversity in Cyprus. More than 100 unidentified Barcode Index Numbers (BINs), along with several morphologically recorded but taxonomically unresolved taxa, point to substantial gaps that remain in the faunal inventory.

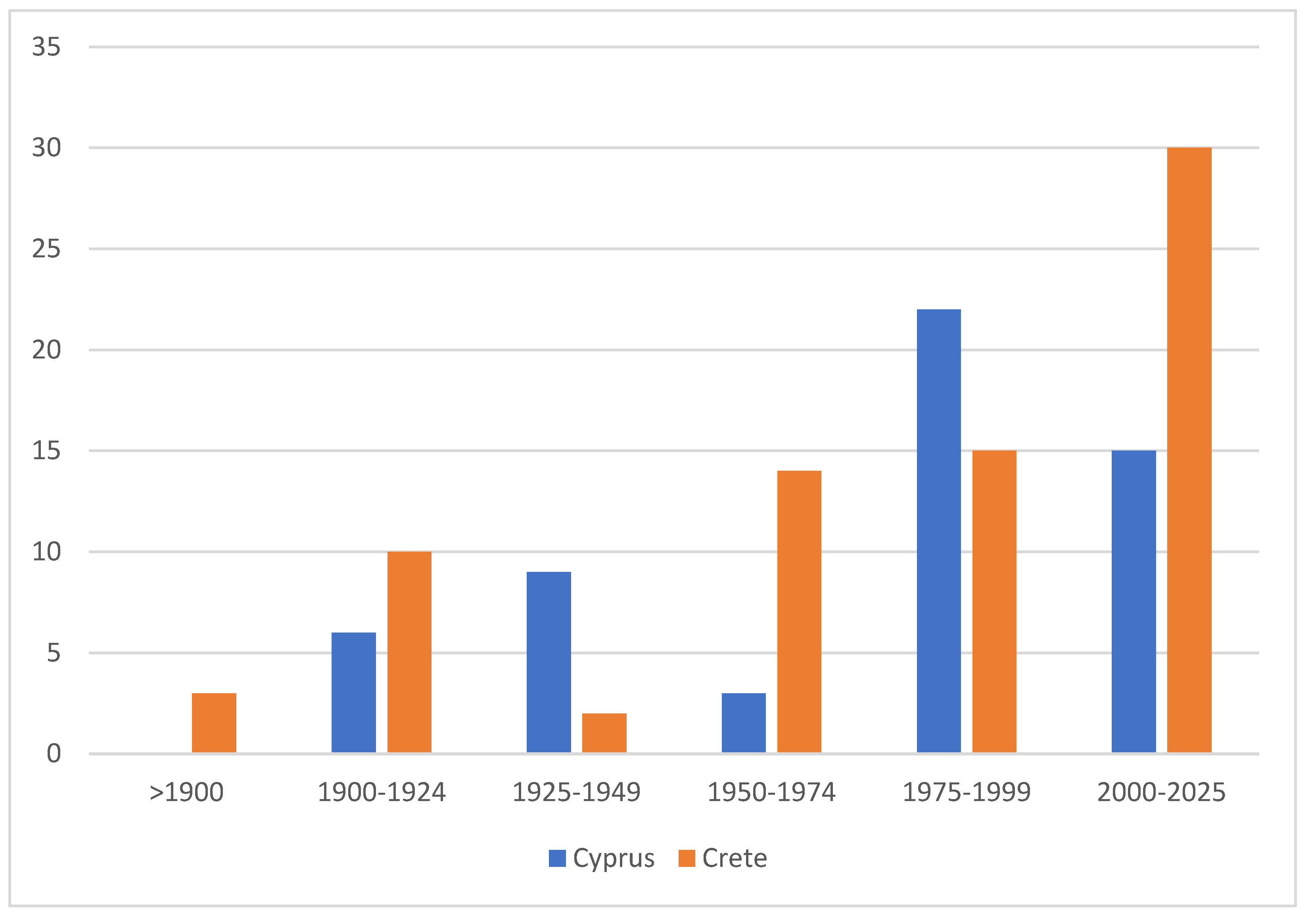

The genetic data generated in this study, currently covering about half of the known species, provides an essential tool for future taxonomic, phylogeographic, and biogeographical research. The resulting barcode library shows close correspondence with recently published data for Crete—a comparable island in terms of size, topographic diversity, and lepidopterological history [49]. While Crete hosts 1230 Linnaean species (of which 724 have been genetically sequenced), 125 species were confirmed there for the first time through DNA barcoding. In Cyprus, the corresponding figures are 1213 species, with 57 new records confirmed genetically and 62 based solely on morphology. Similarly, the number of taxa excluded from the Cypriot faunal list (158 spp.) is comparable to the 212 species removed from the Cretan checklist. Of particular note is the unexpectedly high number of currently unidentified sequence clusters on both islands—105 in Cyprus and 112 in Crete—underscoring the urgent need for further integrative taxonomic revision.

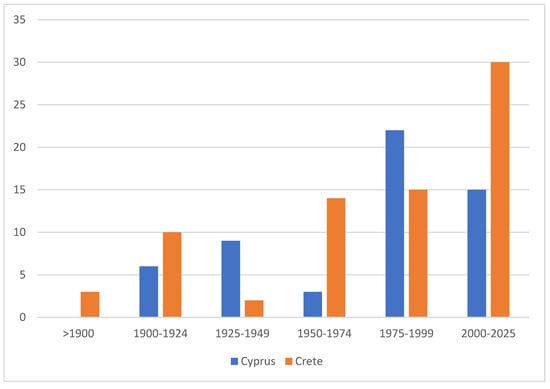

The degree of endemism is also relatively similar between the two islands, although Crete harbors a slightly higher number and proportion of endemic taxa, with 75 species currently recognized compared to 55 in Cyprus (Figure 15). The somewhat higher degree of endemism in Crete is presumably attributable to the island’s longer isolation, but, notably, not to the higher mountain ranges, which, based on currently available data, do not seem to harbor any distinct endemic species. The considerable proportion of endemic species is the result of the long-term isolation of both islands and clearly exceeds that of the mainland-proximate island of Sicily [58]. In contrast, the significance of endemism is even greater on remote islands such as Madeira, where 57 of the 331 recorded species—approximately 17% of the total fauna—are endemic [59].

Figure 15.

Number of endemic Lepidoptera species described in different time periods in Cyprus and Crete. Data indicate the cumulative number of species recognized as endemic during each period, highlighting the continuing rate of discovery in both faunas.

Notably, approximately two-thirds of the Cypriot endemics have been described since 1975, including 15 species that were added after 2000. Although the occurrence of some taxa outside Cyprus would not be unexpected, approximately 5% of the island’s Lepidoptera fauna can nonetheless be considered endemic. Remarkably, even in Rebel’s 1916 treatment, about 6% of the then-listed 166 Cypriot species were already identified as endemics—a proportion that has remained largely stable, despite the seven-fold increase in the number of known species since that time. While Cyprus appears somewhat less rich in endemic taxa than Crete, a precise comparison remains difficult due to numerous unresolved taxonomic issues and the still incomplete molecular coverage of both faunas. The somewhat higher degree of endemism in Crete is presumably attributable to the island’s longer isolation and its highly structured landscape with numerous canyon habitats, but notably not to its higher limestone-dominated mountain ranges, which, based on currently available data, do not appear to harbor any distinct endemic species.

Further discoveries of Cypriot endemics are particularly likely within the 71 unidentified genetic clusters currently known only from the island. However, even seemingly well-studied groups and taxa previously considered unambiguously identified may reveal additional diversity. A notable example is the recently described Episema amettai [60].

Ultimately, a more reliable assessment of the Lepidoptera of Cyprus will only be possible through further integrative studies combining genetic and morphological approaches encompassing the entire island fauna. Even in relatively well-documented families such as Noctuidae and Erebidae, a surprisingly large number of species complexes require taxonomic revision, despite the apparent availability of well-established identification literature, at least for the European fauna [61,62,63,64,65,66,67]. Accordingly, we plan to carry out further sequencing of as-yet unstudied species, along with comprehensive taxonomic revisions. We emphasize that achieving comprehensive genetic coverage for European and Western Palaearctic Lepidoptera represents a fundamental step toward closing the existing sequencing gaps and advancing our understanding of these taxa [68].

5. Conclusions

Genetically based species inventories are a crucial prerequisite for high-quality biodiversity assessments. However, such well-founded checklists remain the exception even in Europe and currently exist for Lepidoptera only in Finland [69]. In the Mediterranean region in particular, historically developed, purely morphology-based inventories often reach their limits due to insufficient taxonomic knowledge, resulting in frequent misclassifications in faunal lists [70].

With the increasing coverage of European species in the Barcode of Life Data Systems (BOLD), the establishment of robust regional inventories based on genetic reference sequences has become feasible as demonstrated for Crete [49] and now for Cyprus.

The still considerable number of genetically validated but unclassified taxa—especially endemic clusters—revealed here highlights persistent gaps in the European DNA barcode library. These gaps must be closed through targeted, integrative taxonomic studies to ultimately achieve complete and reliable faunistic inventories.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/insects17010004/s1: Table S1: Checklist of Lepidoptera from Cyprus; Table S2: Unidentified BINs; Table S3: New faunistic species records for Cyprus based on DNA barcodes; Table S4: New faunistic species records for Cyprus based solely on morphology; Table S5: Unidentified records based solely on morphology; Table S6: Incorrect or doubtful species records. References [71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105,106,107,108,109,110,111,112,113,114,115,116,117,118,119,120,121,122,123,124,125,126,127,128,129,130,131,132,133,134,135,136,137,138,139,140,141,142,143,144,145,146,147,148,149,150,151,152,153,154,155,156,157,158,159,160,161,162,163,164,165,166,167,168,169,170,171,172,173] are cited in the Supplementary Materials.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.H., Ö.Ö. and E.R.; methodology, P.H.; validation, P.H., Ö.Ö., E.R., I.B., J.J., A.H., E.J.v.N. and P.D.N.H.; formal analysis, P.H., Ö.Ö., E.R., I.B., J.J., A.H., E.J.v.N. and P.D.N.H.; investigation, P.H., Ö.Ö., E.R., I.B., J.J., A.H., E.J.v.N. and P.D.N.H.; resources, P.H. and P.D.N.H.; data curation, P.H., Ö.Ö., E.R., I.B., J.J., A.H., E.J.v.N. and P.D.N.H.; writing—original draft preparation, P.H.; writing—review and editing, P.H., Ö.Ö., E.R., I.B., J.J., A.H., E.J.v.N. and P.D.N.H.; funding acquisition, A.H. and P.D.N.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was partially funded by the Canada Foundation for Innovation, by Genome Canada through Ontario Genomics, by the Tri-Council’s New Frontiers in Research Fund, and Biodiversity Genomics Europe (Grant no. 101059492), which is funded by Horizon Europe under the Biodiversity, Circular Economy and Environment call (REA.B.3); co-funded by the Swiss State Secretariat for Education, Research and Innovation (SERI) under contract number 22.00173; and by UK Research and Innovation under the Department for Business, Energy, and Industrial Strategy’s Horizon Europe Guarantee Scheme.

Data Availability Statement

Detailed data to all 2042 specimens and 1859 COI-5P sequences are available in the dataset “Barcoding Lepidoptera of Cyprus” DS-LEPICYPR on BOLD (https://dx.doi.org/10.5883/DS-LEPICYPR), at https://www.boldsystems.org/ (accessed on 23 November 2025).

Acknowledgments

The authors are most grateful to the entire team at the Centre for Biodiversity Genomics (Guelph, Canada). For valuable assistance with materials, data, or technical support, we thank the following colleagues: Kai Berggren, Tim Green, Lauri Kaila, Ole Karsholt, Mikhail Kozlov, Carlos Lopez-Vaamonde, Toni Mayr, Marko Mutanen, Markus Rachinger, László Ronkay, Jukka Tabell, Leo Vähätalo, Jose Vicente Perez, and numerous unnamed experts who have contributed to the current state of knowledge over many years. Egbert Friedrich kindly allowed us to reproduce his excellent pictures. We are furthermore grateful to Johannes Rüdisser for the production of maps. Finally, we gratefully acknowledge the Minister of Agriculture, Rural Development and Environment, Nicosia, and the Department of Environmental Protection, Nicosia, for the research permits.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Gökçekuş, H.; Kassem, Y. (Eds.) Climate Change and Natural Resources: Environmental Management and Sustainable Development; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; Volume VIII, 455p. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cyprus Geological Survey; Ministry of Agriculture; Rural Development and Environment; Government of Cyprus. Geology of Cyprus. Available online: https://www.moa.gov.cy/moa/gsd/gsd.nsf/All/3ED655D39943ACEDC225839400340EBE/$file/GEOLOGY%20OF%20CYPRUS%20%20WEB.pdf?OpenElement (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- Hand, R.; Hadjikyriakou, G.N.; Christodoulou, C.S. (Eds.) (Continuously Updated): Flora of Cyprus—A Dynamic Checklist. Available online: http://www.flora-of-cyprus.eu/ (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- Sparrow, D.; John, E. An Introduction to the Wildlife of Cyprus, 1st ed.; Terra Cypria: Limassol, Cyprus, 2016; 897p. [Google Scholar]

- Özden, Ö.; Hodgson, D.J. Butterflies (Lepidoptera) highlight the ecological value of shrubland and grassland mosaics in Cypriot garrigue ecosystems. Eur. J. Entomol. 2011, 108, 431–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lederer, J. Beitrag zur Schmetterlingsfauna von Cypern, Beirut und einem Theile Kleinasiens (mit Abbild.). Verh. Zool.-Bot. Ver. Wien 1855, 5, 177–254. [Google Scholar]

- Staudinger, O. Lepidopterenfauna Kleinasiens. Horae Soc. Ent. Ross. 1879 – 1881, 14–16, 65–135, 159–435. [Google Scholar]

- Meyrick, E. Three new Microlepidoptera from Cyprus. Entomologist 1923, 56, 277–278. [Google Scholar]

- Meyrick, E. Exotic Microlepidoptera; Taylor and Francis: London, UK, 1923–1930; Volume 3, 640p. [Google Scholar]

- Hayward, K.J. Pyralidae and Microlepidoptera collected in Cyprus during 1920 and 1921. Entomol. Rec. J. Var. 1938, 50, 6–7, 28–30, 80–82, 90. [Google Scholar]

- Rebel, H. Über die Lepidopterenfauna Cyperns. Jahresber. Wien. Entomol. Ver. 1916, 26, 93–110. [Google Scholar]

- Rebel, H. Zur Lepidopterenfauna Cyperns. Mitt. Münch. Entomol. Ges. 1939, 29, 487–564. [Google Scholar]

- Wiltshire, E.P. Middle East Lepidoptera, IX: Two new forms or species and thirty-five new records from Cyprus. Entomol. Rec. J. Var. 1948, 60, 79–87. [Google Scholar]

- Amsel, H.G. Cyprische Kleinschmetterlinge. Z. Wien. Entomol. Ges. 1958, 43, 51–58, 69–75. [Google Scholar]

- Arenberger, E. Die palaearktischen Agdistis-Arten (Lepidoptera, Pterophoridae). Beitr. Naturk. Forsch. SW-Deutschl. 1977, 36, 185–226. [Google Scholar]

- Błeszyński, S. Microlepidoptera Palaearctica . In Crambinae; Georg Fromme & Co.: Wien, Austria, 1965; Volume 1, pp. I–XLVII, 1–553. [Google Scholar]

- Deschka, G. Neue Lithocolletiden von Zypern (Lepidoptera, Lithocolletidae). Entomol. Ber. 1974, 34, 174–179. [Google Scholar]

- Gerini, V. Contributo alla conoscenza dei principali insetti presenti sugli agrumi a Cipro. Riv. Agr. Subtrop. Trop. 1977, 71, 147–159. [Google Scholar]

- Georghiou, G.P. The Insects and Mites of Cyprus. With Emphasis on Species of Economic Importance to Agriculture, Forestry, Man, and Domestic Animals; Benaki Phytopathological Institute: Athens, Greece, 1977; pp. 1–347. [Google Scholar]

- Arenberger, E. Zusammenfassende Darstellung der Mikrolepidopterenfauna Zyperns. Ann. Mus. Goulandris 1994, 9, 253–336. [Google Scholar]

- Arenberger, E.; Wimmer, J. Erster Nachtrag zur Mikrolepidopterenfauna Zyperns. Nachr. Entomol. Ver. Apollo N. F. 1996, 17, 209–224. [Google Scholar]

- Arenberger, E.; Wimmer, J. 2. Nachtrag zur Mikrolepidopterenfauna Zyperns. Z. Arb. Österr. Entomol. 1999, 51, 41–46. [Google Scholar]

- Arenberger, E.; Wimmer, J. Dritter Nachtrag zur Microlepidopterenfauna Zyperns. Quadrifina 2003, 6, 43–54. [Google Scholar]

- Barton, I. A contribution to the microlepidopteran fauna of Cyprus. Entomol. Rec. J. Var. 2015, 127, 157–167. [Google Scholar]

- Barton, I. A second contribution to the Lepidopteran fauna of Cyprus, presenting new records for 48 taxa from 17 families. Entomol. Rec. J. Var. 2018, 130, 29–39. [Google Scholar]

- Huemer, P.; Özden, Ö. First attempts at DNA barcoding Lepidoptera in North Cyprus reveal unexpected complexities in taxonomic and faunistic issues. Diversity 2024, 16, 671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hausmann, A. Beitrag zur Geometridenfauna Zyperns. Z. ArbGem. Österr. Entomol 1994, 46, 91–98. [Google Scholar]

- Hausmann, A. Neue Geometriden-Funde aus Zypern und Gesamtübersicht über die Fauna. Mitt. Münchn. Entomol. Ges. 1995, 85, 79–111. [Google Scholar]

- Fibiger, M. A new Ammoconia species from Cyprus: A. aholai Fibiger, sp. n. (Lepidoptera, Noctuidae). Esperiana 1996, 4, 269–271. [Google Scholar]

- Fibiger, M. New noctuid moths from Cyprus with winter appearance (Lepidoptera, Noctuidae). Entomol. Medd. 1997, 65, 17–27. [Google Scholar]

- Ahola, M. Noctuoidea (Lepidoptera) from Cyprus with descriptions of larvae of some species. Entomol. Fenn. 1998, 9, 19–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fibiger, M.; Nilsson, D.; Svendsen, P. Contribution to the Noctuidae fauna of Cyprus, with descriptions of four new species, six new subspecies, and reports of 55 species not previously found on Cyprus (Lepidoptera, Noctuidae). Esperiana 1999, 7, 639–667. [Google Scholar]

- Can Doğanlar, F.; Arap, N. On the geometrid moths (Lepidoptera) of northern Cyprus, including three new records. Zool. Middle East 2005, 34, 79–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewandowski, S.; Fischer, H. Check-Liste der Noctuidae von Zypern (Lepidoptera, Noctuidae). Atalanta 2004, 35, 119–126. [Google Scholar]

- Lewandowski, S. Ergänzungen und Korrekturen zur Check-Liste der Noctuidae von Zypern. Atalanta 2006, 35, 229–230. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer, H.; Lewandowski, S. Aktualisierte Checkliste der Geometridenarten von Zypern inklusive der wichtigsten Literaturangaben zu dieser Familie (Lepidoptera, Geometridae). Atalanta 2010, 41, 265–269. [Google Scholar]

- Manil, L. Les Rhopalocères de Chypre (Lepidoptera: Papilionoidea Hesperioidea). Linneana Belg. 1990, 12, 313–391. [Google Scholar]

- Karsholt, O.; van Nieukerken, E.J. Lepidoptera, Moths. Fauna Europaea 2013, Version 2021.12. Available online: https://www.eu-nomen.eu/portal/ (accessed on 21 November 2025).

- Lepiforum: Website zur Bestimmung von Schmetterlingen (Lepidoptera) und Ihren Präimaginalstadien. Available online: https://lepiforum.org/wiki/page/Downloads (accessed on 25 October 2025).

- Gozmány, L. The Lepidoptera of Greece and Cyprus. Fauna Graecia IX; Hellenic Zoological Society: Athens, Greece, 2012; Volume 1, pp. 1–409. [Google Scholar]

- Dinca, V.; Dapporto, L.; Somervuo, P.; Vodă, R.; Cuvelier, S.; Gascoigne-Pees, M.; Huemer, P.; Mutanen, M.; Hebert, P.D.N.; Vila, R. High resolution DNA barcode library for European butterflies reveals continental patterns of mitochondrial genetic diversity. Commun. Biol. 2021, 4, 315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopez-Vaamonde, C.; Kirichenko, N.; Cama, A.; Doorenweerd, C.; Godfray, H.C.J.; Guiguet, A.; Gomboc, S.; Huemer, P.; Landry, J.-F.; Laštůvka, A.; et al. Evaluating DNA barcoding for species identification and discovery in European gracillariid moths. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2021, 9, 626752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basso, A.; Avtzis, D.; Burban, C.; Kerdelhué, C.; İpekdal, K.; Magnoux, E.; Rousselet, J.; Negrisolo, E.; Battisti, A. The pine processionary moth Thaumetopoea pityocampa (Notodontidae) species complex: A phylogeny-based revision. Arthropod Syst. Phylogeny 2023, 81, 1031–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabell, J.; Junnilainen, J.; Sihvonen, P. Eupithecia conquesta Tabell & Junnilainen, a new species from Cyprus (Lepidoptera, Geometridae, Larentiinae). Nota Lepidopt. 2024, 47, 11–18. [Google Scholar]

- Huemer, P.; Özden, Ö. Scrobipalpa chardonnayi sp. nov.: A new presumably endemic species from Cyprus (Lepidoptera, Gelechiidae). Zootaxa 2024, 5523, 437–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pühringer, F. Eine neue Art der Gattung Bembecia Hübner, [1819] (Lepidoptera: Sesiidae) aus Zypern. Z. ArbGem. Österr. Entomol. 2024, 76, 19–25. [Google Scholar]

- deWaard, J.R.; Ivanova, N.V.; Hajibabaei, M.; Hebert, P.D.N. Assembling DNA Barcodes: Analytical Protocols. In Methods in Molecular Biology: Environmental Genomics; Martin, C.C., Ed.; Humana Press Inc.: Totowa, NJ, USA, 2008; pp. 275–293. [Google Scholar]

- Ratnasingham, S.; Hebert, P.D.N. BOLD: The Barcode of Life Data System (http://www.barcodinglife.org). Mol. Ecol. Notes 2007, 7, 355–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huemer, P.; Berggren, K.; Aarvik, L.; Rennwald, E.; Hausmann, A.; Segerer, A.; Staffoni, G.; Aspaas, A.M.; Trichas, A.; Hebert, P.D.N. Extensive DNA Barcoding of Lepidoptera of Crete (Greece) Reveals Significant Taxonomic and Faunistic Gaps and Supports the First Comprehensive Checklist of the Island’s Fauna. Insects 2025, 16, 438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratnasingham, S.; Hebert, P.D.N. A DNA-based registry for all animal species: The Barcode Index Number (BIN) System. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e66213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huemer, P.; Karsholt, O.; Aarvik, L.; Berggren, K.; Bidzilya, O.; Junnilainen, J.; Landry, J.-F.; Mutanen, M.; Nupponen, K.; Segerer, A.; et al. DNA barcode library for European Gelechiidae (Lepidoptera) suggests greatly underestimated species diversity. ZooKeys 2020, 921, 141–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lvovsky, A.L.; Sinev, S.Y.; Kravchenko, V.D.; Müller, G.C. A contribution to the Israeli fauna of Microlepidoptera: Oecophoridae, Autostichidae, Depressariidae, Cryptolechiidae and Lecithoceridae with ecological and zoogeographical remarks (Lepidoptera: Gelechioidea). SHILAP Rev. Lepidopt 2016, 44, 97–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gozmány, L. Microlepidoptera Palaearctica . In Lecithoceridae; Georg Fromme & Co.: Wien, Austria, 1978; Volume 5, pp. I–XXVIII, 1–306. [Google Scholar]

- iNaturalist. Available online: https://www.inaturalist.org (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- Demetriou, J.; Radea, C.; Peyton, J.M.; Groom, Q.; Roques, A.; Rabitsch, W.; Seraphides, N.; Arianoutsou, M.; Roy, H.E.; Martinou, A.F. The Alien to Cyprus Entomofauna (ACE) database: A review of the current status of alien insects (Arthropoda, Insecta) including an updated species checklist, discussion on impacts and recommendations for informing management. NeoBiota 2023, 83, 11–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demetriou, J.; Aristophanous, M.; Koutsoukos, E.; John, E.; Roy, H.E.; Martinou, A.F.; Rota, J. A cosmopolitan invader—Choreutis sexfasciella (Lepidoptera, Choreutidae)—In Cyprus: First record, molecular characterization, and a reared parasitoid. Nota Lepidopt. 2025, 48, 15–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huemer, P.; Özden, Ö. Molecular identification of newly recorded Lepidoptera for Cyprus and Europe (Insecta: Lepidoptera). SHILAP Rev. Lepidopt 2024, 52, 691–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karsholt, O.; Razowksi, J. The Lepidoptera of Europe: A Distributional Checklist; Apollo Books: Stenstrup, Denmark, 1996; pp. 1–380. [Google Scholar]

- Aguiar, A.M.F.; Karsholt, O. Systematic Catalogue of the Entomofauna of the Madeira Archipelago amd Selvagens Islands; Museu Municipal do Funchal: Funchal, Portugal, 2006; Volume I, 140p. [Google Scholar]

- Ronkay, G.; Ronkay, L. A revision of the Episema korsakovi (Christoph, 1885) species complex (Noctuidae, Xyleninae, Episemini). Fibigeriana Suppl. 2025, 5, 187–206. [Google Scholar]

- Fibiger, M. (Ed.) Noctuidae Europaeae . In Noctuinae I; Entomological Press: Sorø, Denmark, 1990; Volume 1, pp. 1–208. [Google Scholar]

- Fibiger, M. (Ed.) Noctuidae Europaeae . In Noctuinae III; Entomological Press: Sorø, Denmark, 1997; Volume 3, pp. 1–418. [Google Scholar]

- Hacker, H.; Ronkay, L.; Hreblay, M. Noctuidae Europaeae . In Hadeninae I; Entomological Press: Sorø, Denmark, 2002; Volume 4, pp. 1–419. [Google Scholar]

- Zilli, A.; Ronkay, L.; Fibiger, M. Noctuidae Europaeae . In Apamaeini; Entomological Press: Sorø, Denmark, 2005; Volume 8, pp. 1–323. [Google Scholar]

- Fibiger, M.; Hacker, H. Noctuidae Europaeae . In Amphipyrinae–Xyleninae; Entomological Press: Sorø, Denmark, 2007; Volume 9, pp. 1–410. [Google Scholar]

- Goater, B.; Ronkay, L.; Fibiger, M. Noctuidae Europaeae . In Catocalinae & Plusiinae; Entomological Press: Sorø, Denmark, 2003; Volume 10, pp. 1–452. [Google Scholar]

- Witt, T.J.; Ronkay, L. (Eds.) Noctuidae Europaeae . In Lymantriinae and Arctiinae Including Phylogeny and Check List of the Quadrifid Noctuoidea of Europe; Entomological Press: Sorø, Denmark, 2011; Volume 13, pp. 1–448. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Cong, Q.; Shen, J.; Song, L.; Grishin, N.V. Descriptions of three hundred new species of Hesperiidae (Lepidoptera: Papilionoidea). Insecta Mundi 2025, 1148, 1–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roslin, T.; Somervuo, P.; Pentinsaari, M.; Hebert, P.D.N.; Agda, J.; Ahlroth, P.; Anttonen, P.; Aspi, J.; Blagoev, G.; Blanco, S.; et al. A molecular-based identification resource for the arthropods of Finland. Mol. Ecol. Res. 2021, 22, 803–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huemer, P.; Mutanen, M. An incomplete European barcode library has a strong impact on the identification success of Lepidoptera from Greece. Diversity 2022, 14, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heath, J. New species of Micropterix Hübner (Lepidoptera, Zeugloptera: Micropterigidae) from Greece and Cyprus. Nota Lepidopt. 1985, 8, 336–340. [Google Scholar]

- Gustafsson, B. New leaf-mining moths of the family Nepticulidae from Cyprus, Greece (Lepidoptera). Ent. Scand. 1981, 12, 453–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Nieukerken, E.J.; Doorenweerd, C.; Hoare, R.J.B.; Davis, D.R. Revised classification and catalogue of global Nepticulidae and Opostegidae (Lepidoptera, Nepticuloidea). ZooKeys 2016, 628, 65–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Nieukerken, E.J. Acalyptris Meyrick: Revision of the platani and staticis groups in Europe and the Mediterranean (Lepidoptera: Nepticulidae). Zootaxa 2007, 1436, 1–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Nieukerken, E.J.; Laštůvka, A.; Laštůvka, Z. Western Palaearctic Ectoedemia (Zimmermannia) Hering and Ectoedemia Busck s. str. (Lepidoptera: Nepticulidae): Five new species and new data on distribution, hostplants and recognition. ZooKeys 2010, 32, 1–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Nieukerken, E.J. A taxonomic revision of the Western Palaearctic species of the subgenera Zimmermannia Hering and Ectoedemia Busck s. str. (Lepidoptera, Nepticulidae), with notes on their phylogeny. Tijdschr. Entomol. 1985, 128, 1–164. [Google Scholar]

- Timossi, G.; Huemer, P. Adela paludicolella Zeller, and Adela orientella Staudinger, Lepidoptera, Adelidae: Two distinct species revealed by morphological analysis and DNA barcoding, 1850, 1870 sp. rev. Zootaxa 2025, 5621, 249–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaedike, R. Microlepidoptera of Europe . In Tineidae I (Dryadaulinae, Hapsiferinae, Euplocaminae, Scardiinae, Nemapogoninae and Meessiinae); Brill: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2015; Volume 7, pp. 1–308. [Google Scholar]

- Weidlich, M. Die Psychidenfauna der Republik Zypern (Lepidoptera: Psychidae). Beitr. Entomol. 2015, 65, 113–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weidlich, M. The bisexual Dahlica triquetrella (Hübner, 1813) and new records of Luffia lapidella (Goeze, 1783) in Slovenia (Lepidoptera: Psychidae). Acta Entomol. Slovenica 2013, 21, 163–168. [Google Scholar]

- Gaedike, R. Beitrag zur Kenntnis der ostmediterranen Nemapogoninae (Lepidoptera, Tineidae). Reichenbachia 1986, 24, 23–39. [Google Scholar]

- Gaedike, R.; Kullberg, J. A contribution to the Dryadaulidae and Tineidae of Lebanon, with two species new to science (Lepidoptera). Beitr. Entomol. 2016, 66, 154–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaedike, R. New and poorly known Lepidoptera from the West Palaearctic (Tineidae, Acrolepiidae, Douglasiidae, Epermeniidae). Nota Lepidopt 2007, 29, 159–176. [Google Scholar]

- Gaedike, R. Microlepidoptera of Europe . In Tineidae II (Myrmecozelinae, Perissomasticinae, Tineinae, Hieroxestinae, Teichobiinae, and Stathmopolitinae); Brill: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2019; Volume 9, pp. I–XXIII, 1–248. [Google Scholar]

- Moraiti, C.A.; Kadis, C.; Papayiannis, L.C.; Stavrinides, M.C. Insects and mites feeding on berries of Juniperus foetidissima Willd. on the Mediterranean island of Cyprus. Phytoparasitica 2019, 47, 71–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholz, A. Zwei neue, paläarktische Alucita-Arten (Lepidoptera Alucitidae). Alexanor 1997, 20, 51–58. [Google Scholar]

- Arenberger, E. Die Microlepidopteren Zyperns. 1. Teil: Pterophoridae. Faun. Abh. Mus. Tierk. Dresd. 1985, 12, 129–132. [Google Scholar]

- Arenberger, E. Ergänzungen zur Gattung Agdistis (Lepidoptera, Pterophoridae). Andrias 1983, 3, 51–54. [Google Scholar]

- Arenberger, E. Microlepidoptera Palaearctica . In Pterophoridae. Platyptiliinae: Platyptiliini: Stenoptilia; Goecke & Evers: Keltern, Germany, 2005; Volume 12, pp. 1–191. [Google Scholar]

- Arenberger, E. Zwei neue Mikrolepidopteren aus Zypern (Lepidoptera: Tortricidae, Pterophoridae). Stapfia 1998, 55, 305–311. [Google Scholar]

- Fazekas, I.; Edmunds, H. New records of Alucitidae and Pterophoridae species from Crete (Lepidoptera). Lepidopt. Hung. 2023, 19, 25–36. [Google Scholar]

- Gaedike, R. Two new species of the genus Epermenia Hübner, [1825] and some new distributional and taxonomic records (Lepidoptera: Epermeniidae). SHILAP Rev. Lepidopt. 2022, 50, 755–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nupponen, K.; Junnilainen, J.; Nupponen, T.; Olschwang, V. The cochylid fauna of the Southern Ural Mountains, with description of Cochylimorpha ignicolorana Junnilainen & K. Nupponen sp. n. (Lepidoptera: Tortricidae: Cochylini). Entomol. Fenn. 2001, 12, 94–107. [Google Scholar]

- Razowski, J. Microlepidoptera Palaearctica. In Tortricini; Braun: Melsungen, Germany, 1984; Volume 6, p. I–XV, 1–376. [Google Scholar]

- Larsen, K. Revision of the genus Ditula (Lepidoptera, Tortricidae) with description of a new species. Phegea 2015, 43, 2–5. [Google Scholar]

- Pröse, H. Bemerkungen zur Cydia succedana-Gruppe im Alpen- und Mediterranraum (Lepidoptera, Tortricidae). Stapfia 1988, 16, 257–271. [Google Scholar]

- Pröse, H.; Sutter, R. Cydia marathonana sp. nov., eine neue Art der succedana-Gruppe aus Griechenland und Bemerkungen über Cydia trogodana Pröse, 1988 (Lepidoptera: Tortricidae). Entomol. Z. 2003, 113, 168–169. [Google Scholar]

- Krambias, A. Integrated pest management of pome fruits in Cyprus. Arab. J. Plant Prot. 1998, 16, 49–51. [Google Scholar]

- Karisch, T.; Pinzari, M. Cydia molybdana (Constant, 1884)—A valid species (Lepidoptera: Tortricidae: Olethreutinae). Beitr. Entomol. 2010, 60, 463–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barton, I. On Pammene crataegophila Amsel, 1935 (Tortricidae) from Cyprus, with a description of the female genitalia. Entomol. Rec. J. Var. 2015, 127, 104–108. [Google Scholar]

- Gozmány, L.A. Three new Symmocid species from the Mediterranean Region (Lepidoptera, Symmocidae). Boll. Mus. Reg. Sci. Nat. Torino 2000, 17, 281–286. [Google Scholar]

- Gozmány, L.A. The family Symmocidae and the description of new taxa mainly from the Near East (Lepidoptera). Acta Zool. Acad. Sci. Hung. 1963, 9, 67–134. [Google Scholar]

- Gozmány, L.A. New Symmocid and Holcopogonid species from the Eastern Mediterranean (Lepidoptera; Symmocidae, Holcopogonidae). Entomofauna 1986, 7, 201–214. [Google Scholar]

- Hackman, W. On the insect fauna of Cyprus. Results of the expedition of 1939 by Harald Håkan and P. H. Lindberg. IX. Lepidoptera. Comment. Biol. 1952, 18, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Tokár, Z.; Jaworski, T. Batia hilszczanskii spec. nov. from Cyprus (Lepidoptera, Oecophoridae). Spixiana 2015, 38, 71–76. [Google Scholar]

- Buchner, P.; Corley, M.F.V. Microlepidoptera of Europe . In Depressariidae; Brill: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2024; Volume 10, pp. 1–624. [Google Scholar]

- Huemer, P. The supposedly unmistakable mistaken: Carcina ingridmariae sp. nov., a surprising example of overlooked diversity from Europe and the Near East (Lepidoptera, Peleopodidae). Alp. Entomol. 2025, 9, 51–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falck, P.; Karsholt, O. Gelechiidae of the Canary Islands (Spain). Part 1. Anacampsinae (Insecta: Lepidoptera). SHILAP Rev. Lepidopt. 2025, 53, 5–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bidzilya, O.; Karsholt, O.; Kravchenko, V.; Šumpich, J. An annotated checklist of Gelechiidae (Lepidoptera) of Israel with description of two new species. Zootaxa 2019, 4677, 1–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rebel, H. Zur Lepidopterenfauna Cyperns. V. Verh. Zool.-Bot. Ges. Wien 1928, 78, 29–34. [Google Scholar]

- Karsholt, O.; Rutten, T. The genus Bryotropha Heinemann in the Western Palaearctic (Lepidoptera: Gelechiidae). Tijdschr. Voor Entomol. 2005, 148, 77–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bidzilya, O.; Karsholt, O. A review of the Palearctic Ptycerata Ely, 1910 (= Caulastrocecis Chrétien, 1931, syn. nov.) based on morphology (Lepidoptera, Gelechiidae). Zootaxa 2021, 5026, 151–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huemer, P.; Karsholt, O. Microlepidoptera of Europe . In Gelechiidae II (Gelechiinae: Gnorimoschemini); Apollo Books: Stenstrup, Denmark, 2010; Volume 6, pp. 1–586. [Google Scholar]

- Huemer, P.; Karsholt, O. Microlepidoptera of Europe . In Gelechiidae I; Apollo Books: Stenstrup, Denmark, 1999; Volume 3, pp. 1–356. [Google Scholar]

- Koster, S.; Sinev, S.Y. Microlepidoptera of Europe . In Momphidae s. l; Apollo Books: Stenstrup, Denmark, 2003; Volume 5, pp. 1–387. [Google Scholar]

- Barton, I. A new species of metallic-green Coleophora (Hübner, 1822) (Lepidoptera: Coleophoridae) from Cyprus. Entomol. Rec. J. Var. 2016, 128, 167–171. [Google Scholar]

- Baldizzone, G. I Microlepidotteri di Cipro: III parte, Coleophoridae. Ann. Mus. Goulandris 1985, 7, 263–270. [Google Scholar]

- Kaila, L.; Junnilainen, J. Taxonomy and identification of Elachista cingillella (Herrich-Schäffer, 1855) and its close relatives (Lepidoptera: Elachistidae), with descriptions of two new species. Entomol. Fenn. 2002, 13, 167–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewandowski, S.; Makris, C. Dritter Beitrag zur Fauna der „Spinner und Schwärmer” Zyperns: Neue Erkenntnisse zur Gattung Ocneria Hübner, 1819 (Lepidoptera, Lymantriidae) und aktualisierte Daten zu anderen Familien. Nachr. Entomol. Ver. Apollo N. F. 2006, 27, 165–170. [Google Scholar]

- Yakovlev, R.; Lewandowski, S. Paropta paradoxus kathikas subspec. nov., a new subspecies of the genus Paropta from Cyprus (Lepidoptera, Cossidae). Atalanta 2007, 38, 217–219. [Google Scholar]

- Rebel, H. Bericht der Sektion für Lepidopterologie. Versammlung am 7. Jänner 1927. IV. Beitrag zur Lepidopterenfauna der Insel Cypern. Verh. Zool.-Bot. Ges. Wien 1927, 77, 58–63. [Google Scholar]

- Vassiliou, V.A.; Michael, C.; Kazantzis, E.; Meligronidou-Pantelidou, A. First report of the palm borer Paysandisia archon (Burmeister 1880) (Lepidoptera: Castniidae) in Cyprus. Phytoparasitica 2009, 37, 327–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofmann, P.; Rose, K. Zur Rhopaloceren-Fauna Zyperns (Lepidoptera). Nachr. Entomol. Ver. Apollo N. F. 1987, 7, 133–141. [Google Scholar]

- John, E.; Bağlar, H.; Başbay, O.; Salimeh, M. First appearance in Cyprus of Papilio demoleus Linnaeus, 1758 (Lepidoptera: Papilionidae), as it continues its predicted westward spread in the Palaearctic region. Entomol. Gaz. 2021, 72, 257–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tshikolovets, V.V. Butterflies of Europe & the Mediterranean Area; Tshikolovets Publications: Pardubice, Czech Republic, 2011; 544p. [Google Scholar]

- de Jong, R.; Coutsis, J.G. A re-appraisal of Gegenes Hübner, 1819 (Lepidoptera, Hesperiidae) based on male and female genitalia, with the description of a new genus, Afrogegenes . Tijdschr. Entomol. 2017, 160, 41–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, E.; Evans, S. A first record of eremic Pontia glauconome (Lepidoptera: Pieridae: Pierinae) in Cyprus: An example of unavoidable wind-borne displacement by a Saharan dust storm? Phegea 2025, 53, 86–92. [Google Scholar]

- John, E.; Hawkes, W.L.S.; Walker, E.J. A review of Mediterranean records of Catopsilia florella (Lepidoptera: Pieridae, Coliadinae), with notes on the spring 2019 arrival in Cyprus of this Afrotropical migrant. Phegea 2019, 47, 80–86. [Google Scholar]

- Chapman, T.A. An undescribed Lycaenid Butterfly from Cyprus, Glaucopsyche paphos, sp. n. (Lycaenidae). Trans. Entomol. Soc. Lond. 1920, 166, 166–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, E.; Houkes, J.; Salmela, T. Rediscovery of Issoria lathonia (Lepidoptera: Nymphalidae: Heliconiinae) in Cyprus. Phegea 2024, 52, 44–46. [Google Scholar]

- Benjamini, D. Hypolimnas misippus (Linnaeus, 1767) (Lepidoptera: Nymphalidae) in Cyprus and other records in the Eastern Mediterranean, an overlooked record and east Mediterranean butterfly migration corridors. Entomol. Gaz. 2021, 72, 243–252. [Google Scholar]

- Graves, P.P. Epinephele cypricola Sp. nov. Entomologist 1928, 61, 5–7. [Google Scholar]

- John, E.; Haines, D.H.; Haines, H.M. Chazara persephone (Hübner, 1803) (Lepidoptera: Nymphalidae, Satyrinae)—Has the species retained a secretive presence in Cyprus for one hundred years? Entomol. Gaz. 2011, 62, 79–82. [Google Scholar]

- Holik, O. Über die Gattung Satyrus L. Z. Wien Entomol. Ges. 1949, 34, 98–105. [Google Scholar]

- Slamka, F. Pyraloidea of Europe (Lepidoptera) . In Pyralinae, Galleriinae, Epipaschiinae, Cathariinae & Odontiinae; F. Slamka: Bratislava, Slovakia, 2006; Volume 1, pp. 1–138. [Google Scholar]

- Slamka, F. Pyraloidea of Europe (Lepidoptera) . In Phycitinae–Part 1; F. Slamka: Bratislava, Slovakia, 2019; Volume 4, pp. 1–432. [Google Scholar]

- Yepishin, J.; Bidzilya, O.; Budashkin, Y.; Zhakov, O.; Mushynskyi, V.; Novytskyi, S. New records of little known pyraloid moths (Lepidoptera: Pyraloidea) from Ukraine. Zootaxa 2020, 4808, 101–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roesler, R.U. Microlepidoptera Palaearctica . In Phycitinae; Georg Fromme & Co.: Wien, Austria, 1973; Volume 4, p. I–XVI, 1–752. [Google Scholar]

- Roesler, U. Chorologische Untersuchungen über den Homoeosoma-Ephestia-Komplex (Lepidoptera: Phycitinae) im paläarktischen Raum. Bonn. Zool. Beitr 1965, 16, 318–349. [Google Scholar]

- Amsel, H.G. Die Microlepidopteren der Brandt’schen Iran-Ausbeute. 4. Teil. Ark. Zool. 1953, 6, 255–326. [Google Scholar]

- Goater, B.; Nuss, M.; Speidel, W. Microlepidoptera of Europe . In Pyraloidea I (Crambidae: Acentropinae, Evergestinae, Heliothelinae, Schoenobiinae, Scopariinae); Apollo Books: Stenstrup, Denmark, 2005; Volume 4, pp. 1–304. [Google Scholar]

- Barton, I.; Rosewarne, K.; John, E. Chilo partellus (Swinhoe, 1885) (Lep.: Pyraloidea, Crambidae) a stem borer on Cyprus. Entomol. Rec. J. Var. 2013, 125, 181–185. [Google Scholar]

- Slamka, F. Pyraloidea of Europe (Lepidoptera) . In Crambinae & Schoenobiinae; F. Slamka: Bratislava, Slovakia, 2008; Volume 2, pp. 1–223. [Google Scholar]

- Slamka, F. Pyraloidea of Europe (Lepidoptera) . In Pyraustinae & Spilomelinae; F. Slamka: Bratislava, Slovakia, 2013; Volume 3, pp. 1–357. [Google Scholar]

- Skou, P.; Sihvonen, P. The Geometrid Moths of Europe. In Subfamily Ennominae I (Abraxini, Apeirini, Baptini, Caberini, Campaeini, Cassymini, Colotoini, Ennomini, Epionini, Gnophini (Part), Hypochrosini, Lithinini, Macariini, Prosopolophini, Theriini and 34 Species of Uncertain Tribus Association); Brill: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2015; Volume 5, 657p. [Google Scholar]

- Prout, L.B. New Palaearctic Geometridae. Novit. Zool. 1929, 35, 142–149. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer, H. Crocallis cypriaca sp. nov., eine neue Spannerart von der Insel Zypern (Lepidoptera: Geometridae, Ennominae). Entomol. Z 2003, 113, 372–374. [Google Scholar]

- Müller, B.; Erlacher, S.; Hausmann, A.; Rajaei, H.; Sihvonen, P.; Skou, P. The Geometrid Moths of Europe. In Subfamily Ennominae II (Boarmiini, Gnophini, Additions to Previous Volumes); Brill: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2019; Volume 6. [Google Scholar]

- Prout, L.B. Spannerartige Nachtfalter. In Die Gross-Schmetterlinge der Erde. Eine Systematische Bearbeitung der bis jetzt bekannten Gross-Schmetterlinge; Seitz, A., Ed.; Kernen: Stuttgart, Germany, 1904–1914; Volume 4 (I–V), pp. 1–479. [Google Scholar]

- Hausmann, A. The Geometrid Moths of Europe. In Sterrhinae; Apollo Books: Stenstrup, Denmark, 2004; Volume 2, pp. 1–600. [Google Scholar]

- Hausmann, A.; Viidalepp, J. The Geometrid Moths of Europe. In Larentiinae I; Apollo Books: Vester Skerninge, Denmark, 2012; Volume 3, pp. 1–743. [Google Scholar]

- Prout, L.B. Die Gross-Schmetterlinge der Erde. Eine Systematische Bearbeitung der bis jetzt bekannten Gross-Schmetterlinge; Seitz, A., Ed.; Kernen: Stuttgart, Germany, 1934–1954; Volume 4, Suppl. pp. 1–766. [Google Scholar]

- Hausmann, A.; Friedrich, E. An integrative taxonomic approach to resolving some difficult questions in the Larentiinae of the Mediterranean region (Lepidoptera, Geometridae). Mitt. Münchn. Entomol. Ges. 2011, 101, 73–97. [Google Scholar]

- Mironov, V. The Geometrid Moths of Europe. In Larentiinae II (Perizomini and Eupitheciini); Apollo Books: Stenstrup, Denmark, 2003; Volume 4, pp. 1–464. [Google Scholar]

- Bang-Haas, O. Ocnogyna cypriaca . Ent. Zeit. Int. Ent. Zeit. 1934, 48, 48. [Google Scholar]

- Koçak, A.Ö.; Kemal, M. A synonymous and distributional list of the species of the Lepidoptera of Turkey. CESA Mem. 2018, 8, 1–487. [Google Scholar]

- Macià, R.; Ylla, J.; Gastón, J.; Huertas, M.; Bau, J. The species of Eilema Hübner, [1819] sensu lato present in Europe and North Africa (Lepidoptera: Erebidae: Arctiinae: Lithosiini). Zootaxa 2022, 5191, 1–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fibiger, M.; Ronkay, L.; Yela, J.L.; Zilli, A. Noctuidae Europaeae . In Rivulinae, Boletobiinae, Hypenodinae, Araeopteroninae, Eublemminae, Herminiinae, Hypeninae, Phytometrinae, Euteliinae, and Micronoctuidae. Including Supplement to Volumes 1–11; Entomological Press: Sorø, Denmark, 2010; Volume 12, pp. 1–451. [Google Scholar]

- Boursin, C. Zwei neue Cryphia Hb. (Bryophila)-Arten aus dem vorderasiatisch-mediterranen Faunenkreis. (Beiträge zur Kenntnis der “Agrotidae-Trifinae” LV (55)). Z. Wien. Entomol. Ges. 1952, 37, 152–155. [Google Scholar]

- Top-Jensen, M.; Fritsch, D.; Kononenko, V. Noctuidae Europaeae Essential; Bugbook Publishing: Oestermarie, Denmark, 2023; 837p. [Google Scholar]

- Hacker, H. Revision of the genus Caradrina Ochsenheimer, 1816, with notes on other genera of the tribus Caradrini (Lepidoptera, Noctuidae). Esperiana 2004, 10, 7–690. [Google Scholar]

- Hacker, H. Ergänzungen zu „Die Noctuidae Vorderasiens” und neuere Forschungsergebnisse zur Fauna der Türkei II (Lepidoptera). Esperiana 1996, 4, 273–330. [Google Scholar]

- Benedek, B.; Tóth, B. Boursinia discordans (Boursin, 1940), a new Noctuidae species for the fauna of Cyprus (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae). Ann. Mus. Hist.-Nat. Hung. 2022, 114, 129–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hampson, G.F. Catalogue of the Lepidoptera Phalaenae in the British Museum; Taylor and Francis: London, UK, 1903; Volume 4, pp. i–xx, 1–689. [Google Scholar]

- Brandstetter, J. Beschreibung einer neuen Art der Gattung Agrotis Ochsenheimer, 1816 aus Zypern (Lepidoptera, Noctuidae). Atalanta 2010, 41, 285–288. [Google Scholar]

- Lödl, M. Noctua warreni sp. n., a new sibling species of Noctua comes Hübner, 1813 from Cyprus (Lepidoptera, Noctuidae). Nota Lepidopt. 1987, 10, 163–174. [Google Scholar]

- Danner, F.; Eitschberger, U.; Surholt, B. Die Schwärmer der westlichen Palaearktis. Bausteine zu einer Revision (Lepidoptera: Sphingidae). Herbipoliana. Buchr. Zur Lepidopterol. 1998, 4/1–4/2, 368–720. [Google Scholar]

- Aristophanous, M.; Pittaway, A.R.; Aristophanous, A. Rediscovery of Clarina syriaca (Lederer, 1855) (Lepidoptera, Sphingidae, Macroglossinae) in Cyprus after 70 years; with notes on its biology and early life history from the Levant. Nota Lepidopt. 2022, 45, 305–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregersen, K.; Karsholt, O. Taxonomic confusion around the Peach Twig Borer, Anarsia lineatella Zeller, 1839, with description of a new species (Lepidoptera, Gelechiidae). Nota Lepidopt. 2017, 40, 65–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berggren, K.; Aarvik, L. Callima icterinella (Mann, 1867) comb. nov. (Lepidoptera, Oecophoridae), a complex consisting of seven species. Nor. J. Entomol. 2024, 71, 95–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamczewski, S. On the systematics and origin of the generic group Oxyptilus Zeller (Lep., Alucitidae). Bull. Br. Mus. (Nat. Hist.) Entomol. 1951, 1, 303–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trematerra, P. Clepsis trifasciata sp. n. with notes on some Lepidoptera Tortricidae from Kirgizstan. J. Entomol. Acarol. Res. 2010, 42, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, E.; Wiemers, M.; Makris, C.; Russell, P. The Pontia daplidice (Linnaeus, 1758)/Pontia edusa (Fabricius, 1777) complex (Lepidoptera: Pieridae): Confirmation of the presence of Pontia daplidice in Cyprus, and of Cleome iberica DC. as a new host plant for this species in the Levant. Entomol. Gaz. 2013, 64, 69–78. [Google Scholar]