Simple Summary

This study analyzed the relationship between the suitable habitats of Bactrocera minax (Enderlein) (Diptera: Tephritidae) and Bactrocera tsuneonis (Miyake) (Diptera: Tephritidae) in China, and various environmental factors using the MaxEnt ecological niche model. By incorporating citrus plant coverage as a key environmental variable, the model achieved higher accuracy and improved predictive performance compared to previous studies. At present, B. minax and B. tsuneonis are primarily distributed in southern Chinese provinces, where citrus cultivation is widespread. The spatial distribution of citrus plants plays a pivotal role in shaping the geographical range of these fruit flies. Across all climate scenarios, B. tsuneonis exhibits a consistent trend of habitat contraction. Higher greenhouse gas emission scenarios appear to contribute to a reduction in B. minax and B. tsuneonis, potentially aiding in pest control. Nevertheless, regions engaged in citrus production—particularly eastern Sichuan—should implement enhanced management measures to prevent the invasion and spread of B. minax and B. tsuneonis. These findings provide valuable scientific insights for forecasting species distributions and developing targeted management and control strategies. The results support the sustainable and resilient development of China’s citrus industry.

Abstract

The Bactrocera minax (Enderlein) (Diptera: Tephritidae) and Bactrocera tsuneonis (Miyake) (Diptera: Tephritidae) are the only members of the subgenus of the Tetradacus of Bactrocera. They share nearly identical morphological characteristics and occupy highly overlapping ecological niches, specifically harming citrus crops and causing substantial damage to citrus production in China. To determine the suitable habitat of the two pests and how the citrus coverage affects this distribution. This study employed the Maximum Entropy model (MaxEnt) to predict the potential geographic distributions (PGDs) of B. minax and B. tsuneonis under current and future climate scenarios, using species occurrence data and key environmental variables. The result indicate that the MaxEnt model performed well, with an area under the curve value (AUC) of 0.969. The citrus distribution index, precipitation of driest month (BIO 14), min temperature of coldest month (BIO 6), and elevation were identified as the primary environmental factors affecting their PGDs. The PGDs for these pests are mainly concentrated in southern China, where citrus is extensively cultivated. Guizhou and Hunan identified as the most significant high-suitability habitat. The projected distribution of B. minax and B. tsuneonis show minimal changes under the future climate conditions estimated by the MaxENT model. However, under global warming scenarios, their PGDs are projected to gradually shrink, although eastern Sichuan remains at high risk of invasion by B. tsuneonis. Prevention, quarantine, and control measures for B. tsuneonis require continued attention. The findings of this study offer a more robust theoretical basis for the targeted monitoring and control of B. minax and B. tsuneonis in China.

1. Introduction

Tephritidae is one of the largest families of Diptera, comprising more than 4000 fruit fly species, among which approximately 350 are considered economically important pests [1]. The Tetradacus is the subgenus of Bactrocera (family Tephritidae), widely distributed across tropical and subtropical regions of East Asia [2,3]. Bactrocera minax and Bactrocera tsuneonis are the only two species classified under Tetradacus.

B. minax, commonly known as the ‘citrus maggot fly’ in China, is a devastating pest of citrus fruits [4]. The larvae feed on orange segments and seeds, leading to internal decay of citrus fruits [5]. B. tsuneonis is a univoltine tephritid pest [6,7], that infests citrus species including sweet orange, grapefruit, lemon, and other citrus fruit trees [8]. As an important quarantine pest both internationally and domestically, it is officially listed in the List of Imported Phytosanitary Pests of the People’s Republic of China and China’s National List of Agricultural Plant Quarantine Pests (2024) [9,10].

The two pests share almost identical morphological characteristics and occupy highly overlapping ecological niches. B. tsuneonis can be distinguished from B. minax by its 1–2 pairs of anterior supra-alar seta on the mesonotum (absent in B. minax) and a female ovipositor about half the abdominal length (as long as the abdomen in B. minax) [4,11]. In addition, the two pests can be accurately identified through DNA barcoding [12,13]. They have similar damage symptoms. Infested immature fruits undergo premature yellowing, followed by rotting or loss of edible value [14], severely threatening the profitability of citrus cultivation in China. They are primarily distributed in Yunnan, Sichuan, Guizhou, Hunan, and Guangdong. Both pests primarily rely on short-distance flight or medium-range wind-assisted dispersal. Research indicates that B. minax can spread up to 1500 m when aided by favorable wind [15]. However, long-distance dispersal is primarily achieved through the transportation of seedlings and fruits.

Citrus reticulata as the primary host of B. minax and B. tsuneonis, represents one of the world’s most widely cultivated and economically important crop groups [16]. Since the beginning of this century, both the planting area and production of citrus in China have increased steadily. However, significant challenges remain in citrus pest prevention and control [17], particularly following the 2008 fruit maggot outbreak in Guangyuan, Sichuan, which caused more than losses exceeding 20 billion yuan and severely impacted the industry’s reputation [18,19]. Therefore, accurate species identification and precise monitoring are crucial for effective pest management. Modeling the potential distribution of suitable habitats of B. minax and B. tsuneonis forms the foundation for safeguarding the citrus industry in China.

The Maximum Entropy model (MaxEnt), which integrates machine learning with the principle of maximum entropy, is widely recognized as one of the most robust tools for predicting species’ potential distributions. It is characterized by high prediction accuracy and standardized input formats, and is extensively used in fields such as biogeography, invasion biology, conservation biology, and studies on the impacts of global climate change on species distributions [20]. For example, Fu et al. predicted that B. minax potential suitable habitats may shift toward the lower–middle Yangtze River Basin under future climates [21]. Similarly, Mao employed the MaxEnt model to predict that, under future climate change scenarios, B. tsuneonis is likely to expand its potential suitable range into northern and western China [22].

However, citrus distribution has not previously been incorporated into distribution models of B. minax and B. tsuneonis, and a systematic comparison of the suitable habitats of B. minax and B. tsuneonis remains lacking. Building on previous research, this study employs the MaxEnt model, integrating citrus plant coverage as a key environmental variable alongside geographic occurrence data and climate data from different periods to simulate the PGDs of B. minax and B. tsuneonis species in China. It examines current patterns of suitable habitat distribution and projects future shifts in PGDs under various climate change scenarios, offering both empirical data and a theoretical foundation for safeguarding the citrus industry.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Occurrence Record of B. minax and B. tsuneonis

The distribution data for B. minax and B. tsuneonis were obtained from online databases and field surveys. Relevant occurrence records of B. minax and B. tsuneonis were downloaded from the Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF Occurrence Download: https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.5ugbmt, accessed on 7 November 2024) [23], the Centre for Agriculture and Biosciences International (CABI, http://www.cabi.org, accessed on 23 April 2025), and the National Animal Specimen Resource Center (http://museum.ioz.ac.cn/specimens.aspx?str=Arthropoda&type=1, accessed on 23 April 2025). Field sampling was conducted in Yunnan, Guizhou, Sichuan, Chongqing, Hunan, Guangxi, and Hubei provinces. After removing duplicate entries and records lacking precise geographic information, a total of 91 valid occurrence points for B. minax and 43 for B. tsuneonis were retained.

2.2. Environment Variables Related to B. minax and B. tsuneonis

A total of 24 environmental variables were incorporated into the modeling process, including elevation, slope, aspect, 19 bioclimatic variables, the Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI), and a citrus distribution index. Ultimately, five bioclimatic variables (BIO2, BIO3, BIO4, BIO6, and BIO14), three topographic variables (elevation, slope, and aspect), and one host-related variable (citrus cover index) were selected for model construction. To ensure comparability of model outputs across different climate scenarios, elevation, slope, aspect, and citrus cover were assumed to remain constant over time.

2.3. Climatic Data

Contemporary (1970–2000) climate data were obtained from the WorldClim database (https://www.worldclim.org/, accessed on 23 April 2025), including 19 bioclimatic variables (BIO1–BIO19) related to temperature and precipitation, with a spatial resolution of 2.5 arc-minutes [24].

Future climatic projections were obtained from the BCC-CSM2-MR model, developed by the Beijing Climate Center, which is part of the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project Phase 6 (CMIP6). Four Shared Socioeconomic Pathway (SSP) scenarios were used to model potential future distributions for the period 2041–2080: SSP1–2.6 (low forcing), SSP2–4.5 (moderate forcing), SSP3–7.0 (moderate to high forcing), SSP5–8.5 (high forcing).

2.4. Topographic Data

Vegetation data, Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) values, were obtained from the Distributed Active Archive Center for Biogeochemical Dynamics (DAAC, https://daac.ornl.gov/, accessed on 23 April 2025, Oka Ridge, TN, USA). The multi-year average NDVI was calculated using the maximum value composite method.

Given that B. minax and B. tsuneonis are oligophagous pests mainly infesting citrus, occurrence data for citrus plants were also downloaded from GBIF (GBIF Occurrence Download: https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.8w2g5u, accessed on 29 March 2025) [25]. Following the methods of Zhao and Crego, 10,000 background (pseudo-absence) points were randomly generated across China [26,27,28]. Kriging interpolation was applied to create a citrus distribution raster [29], which was included as a key environmental variable.

2.5. Distribution Model Construction and Accuracy Evaluation

All environmental variables were processed and defined using ArcGIS 10.8. The geographic coordinate system was set to CGCS_WGS_1984, and the projected coordinate system was set to GCS Krasovsky 1940–Albers. Environmental data within China were extracted in bulk, resampled to a spatial resolution of 8 km × 8 km, and subsequently converted to ASCII format for use in MaxEnt modeling.

During the modeling process, 75% of the B. minax and B. tsuneonis occurrence data were randomly selected as training dataset, while the remaining 25% were used as test dataset. The maximum number of iterations was set to 10,000, the number of replicates was set to 10, and all other parameters were kept at their default settings [30].

To minimize multicollinearity among environmental variables and prevent overfitting in the MaxEnt model, ENMTools 3.4.4 [31] was employed to preprocess environmental variables and species occurrence data. Correlation analysis was conducted in R to address potential multicollinearity among the 19 bioclimatic variables, as high multicollinearity can lead to overfitting and reduced predictive accuracy [32,33]. When the Pearson correlation coefficient between two variables exceeded 0.8, the variable with the higher contribution rate to the distribution of B. minax and B. tsuneonis were preferentially retained [34,35].

2.6. Division of the PGDs and Calculation of Centroids

The classification of climate suitability refers to the classification criteria outlined for assessment likelihood in the 6th Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) [36]. Regions were then classified based on species richness from highest to lowest, using the spatial analyst tools in ArcGIS 10.8 and applying the natural breaks (Jenks) method [37]. The PGDs of B. minax and B. tsuneonis under current and future climate conditions were categorized based on probability values: unsuitable habitat (0–0.1), low-suitability habitat (0.1–0.3), moderate-suitability habitat (0.3–0.5) and high-suitability habitat (0.5–1). The areas of each PGD at different periods were calculated by using the spatial statistical function of ArcGIS. Additionally, the centroid coordinates of the PGDs were computed using R 4.3.1 software. Changes in centroid positions across scenarios were analyzed to predict the spatiotemporal distribution trends of B. minax and B. tsuneonis [38].

3. Results

3.1. Current Distribution of B. minax and B. tsuneonis

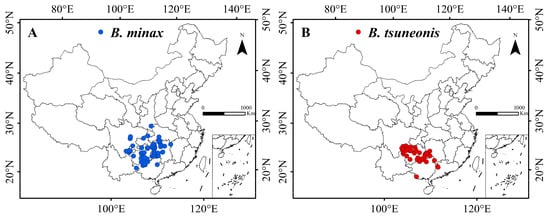

The occurrence of B. minax is densely concentrated in Guizhou and Hunan provinces, with sparser distributions observed in Hubei, Sichuan, Yunnan, Guangxi, Guangdong, Chongqing, and Shanxi (Figure 1A). In contrast, B. tsuneonis exhibits a denser but more geographically restricted distribution compared to B. minax (Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

Occurrence of B. minax (A) and B. tsuneonis (B).

3.2. Model Prediction Result Verification

The AUC value of MaxEnt model is 0.969, which reaches an excellent level, indicating that the MaxEnt model can well predict the distribution of suitable habitat of B. minax and B. tsuneonis in China.

3.3. Evaluation of Important Environment Variables

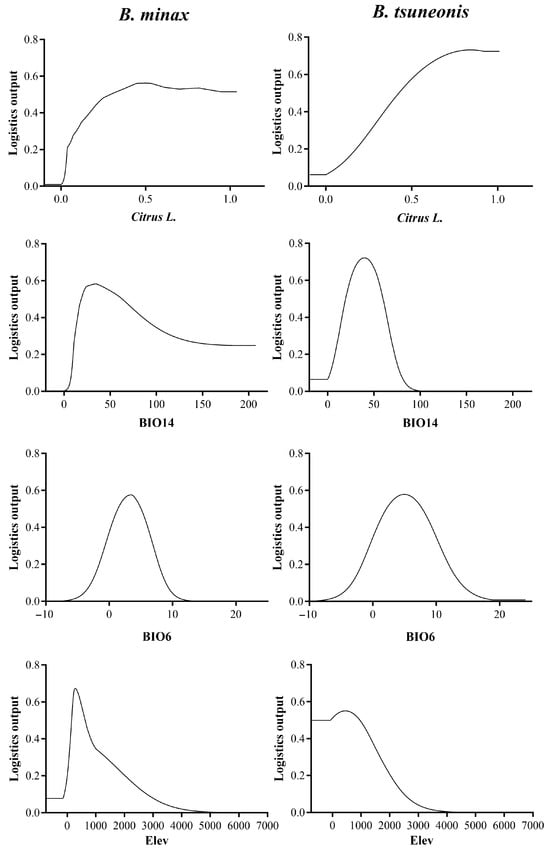

The Citrus distribution index, BIO 14, BIO 6, and elevation contributed 39.9%, 14.3%, 9.2%, and 8%, respectively, with a cumulative contribution of 71.4% (Table 1). B. minax was found to favor areas where the citrus distribution index is ≥0.28, the precipitation during the driest month ranges from 18 to 63 mm, the mean temperature of the coldest month is between 1.4 °C and 5 °C, and elevation ranges from approximately 150 to 625 m. In contrast, B. tsuneonis favors habitats where the citrus distribution index is ≥0.45, the precipitation during the driest month ranges from 19 to 60 mm, the mean temperature of the coldest month is between 2 °C and 7 °C, and elevation ranges from approximately 240 to 970 m (Figure 1 and Figure 2).

Table 1.

Selection of environmental variables and the contribution ratio.

Figure 2.

Response curve of major environmental variables of B. minax and B. tsuneonis. Citrus L.: response curve of citrus distribution index; BIO14: response curve of precipitation of driest month; BIO6: response curve of min temperature of coldest month; Elev: response curve of elevation.

3.4. PGDs of B. minax and B. tsuneonis in China

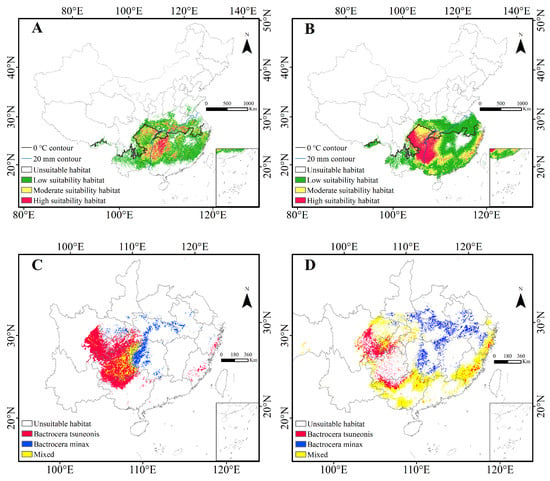

The PGDs of both pests are predominantly confined to southern China, primarily south of the 0 °C isotherm for the coldest month, with small patches of low-suitability habitat identified in southern Tibet. No suitable habitats were detected in the Poyang Lake Basin or Hainan. Currently, the suitable habitat of B. minax is primarily concentrated in southern China, particularly in the middle and lower Yangtze River regions, the Yunnan-Guizhou Plateau, and the southeastern hills, with smaller scattered patches in Guangdong and Guangxi (Figure 3A). The suitable habitat of B. tsuneonis is broader in extent, covering large areas along the lower Yangtze River, Guangdong, and Guangxi (Figure 3B). High-suitability habitats for both species are primarily distributed from the eastern Yunnan-Guizhou Plateau and the upper Yuan River basin, extending in two distinct directions: for B. minax, eastward along the plateau and the upper Yuan River, following the 20 mm precipitation contour for the driest month along the lower Yangtze; for B. tsuneonis, westward into Guizhou, Chongqing, and eastern Sichuan, with additional scattered pockets along the eastern coastal regions.

Figure 3.

Current potential distribution of B. minax and B. tsuneonis in China. (A): Distribution of contemporary suitable habitat of B. minax; (B): Distribution of contemporary suitable habitat of B. tsuneonis; (C): Crossing analysis of high-suitability habits of B. minax and B. tsuneonis; (D): Crossing analysis of low-suitability habits of B. minax and B. tsuneonis.

Nationally, the total suitable habitat for Bactrocera minax is estimated at approximately 1,360,000 km2, representing about 14% of China’s land area. This includes 989,000 km2 of low-suitability habitat, 394,000 km2 of moderate-suitability habitat, and 148,000 km2 of high-suitability habitat. B. tsuneonis exhibits a broader distribution, with suitable habitat covering approximately 1,870,000 km2 (around 19% of China), comprising 1,095,000 km2 of low-suitability habitat, 452,000 km2 of moderate suitability, and 330,000 km2 of high suitability. These findings indicate that B. minax and B. tsuneonis have a broad ecological amplitude, with B. tsuneonis occupying a significantly larger potential range than B. minax. Comparison of high- and low-suitability areas reveals that zones of high-suitability overlap at the Hunan–Guizhou border, after which the distributions diverge—extending eastward for B. minax and westward for B. tsuneonis (Figure 3C). Their low-suitability habitats form a distinct ‘C’-shaped belt encompassing eastern, southern, and western China, eventually merging into moderate and high-suitability zones in eastern Sichuan and southern Chongqing (Figure 3D). Additionally, isolated pockets of suitable habitat for both species were identified in Medog County, Nyingchi, Tibet.

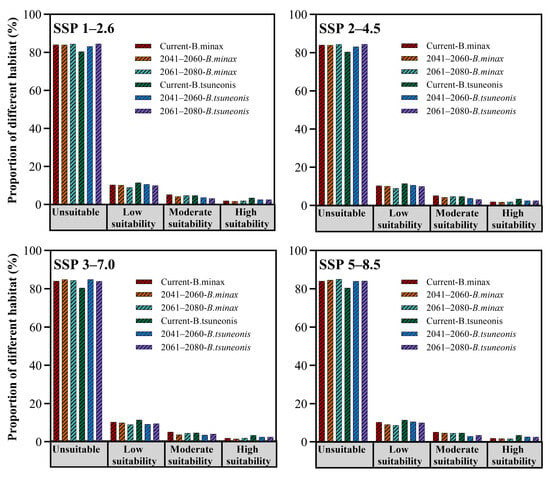

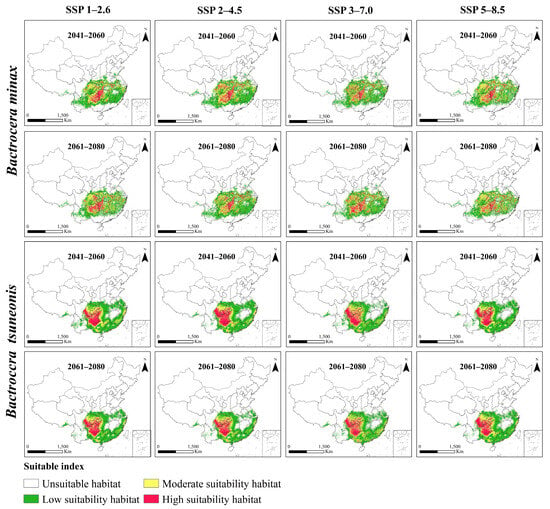

3.5. PGDs of B. minax and B. tsuneonis Under Future Climate Scenarios

Under four future climate scenarios (SSP1–2.6, SSP2–4.5, SSP3–7.0, and SSP5–8.5), both B. minax and B. tsuneonis exhibit overall declines in climatic suitability (Figure 4). Under the SSP1–2.6 scenario, the total suitable habitat for B. minax expands slightly, with high-suitability areas increasing by approximately 27% during 2061–2080, particularly in eastern Guizhou, western Hunan, southern Hubei, western Anhui, and central Sichuan. In contrast, B. tsuneonis shows a contraction in suitable habitat, with moderate-suitability areas decreasing by 34% by 2061–2080, mainly in southern Chongqing, Guizhou, and western Hunan. Under the SSP2–4.5 scenario, B. minax initially exhibits a modest increase in total suitable habitat from 2041 to 2060, followed by a subsequent decline. Meanwhile, B. tsuneonis experiences continuous habitat contraction across low-, moderate-, and high-suitability classes, progressively retreating toward a core distribution zone centered in Guizhou. In the SSP3–7.0 scenario, both species undergo reductions in total suitable habitat during 2041–2060, followed by a partial rebound in 2061–2080, primarily attributable to shifts in moderate-suitability zones. However, B. tsuneonis experiences a substantial net reduction during 2041–2060, driven by losses in both low- and high-suitability habitats. Similarly, under the high-emission SSP5–8.5 scenario, B. tsuneonis continues to lose suitable habitat as both low- and high-suitability areas shrink. In contrast, B. minax shows a slight increase in habitat suitability during 2041–2060, mainly due to the expansion of low-suitability areas, followed by a notable decline by 2061–2080 (Figure 5).

Figure 4.

Proportion of different habitats of B. minax and B. tsuneonis for current and future climate conditions.

Figure 5.

Habitats of B. minax and B. tsuneonis in China under different shared socioeconomic pathways (SSP).

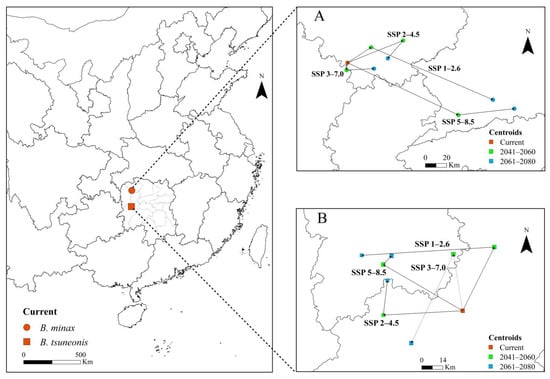

3.6. Centroid Shift in B. minax and B. tsuneonis Under Future Climate Change

The projected shifts in the geographic centroids of suitable habitats for B. minax and B. tsuneonis under various climate change pathways are depicted in Figure 6. Under current climatic conditions, the centroid for B. minax is currently situated in southwestern Zhangjiajie City, Hunan Province. Under the SSP1–2.6 pathway, it initially shifts northeastward and then southeastward, ultimately stabilizing in Changde City, Hunan Province. Under the SSP2–4.5 pathway, the centroid first moves northeastward before shifting southwestward. In the SSP3–7.0 pathway, it initially shifts southward before trending eastward. Under the SSP5–8.5 high-emission pathway, the centroid gradually shifts eastward and ultimately stabilizes in Changde City (Figure 6A). For B. tsuneonis, the current centroid is located in Huaihua City, Hunan Province. Under the SSP1–2.6 pathway, the centroid initially shifts northeastward and then westward, ultimately stabilizing in the Xiangxi Tujia and Miao Autonomous Prefecture. Under both the SSP2–4.5 and SSP3–7.0 pathways, the centroid first shifts westward and subsequently trends northward. Under SSP5–8.5, the centroid exhibits a northwestward shift followed by a northeastward movement, eventually stabilizing in the Xiangxi Tujia and Miao Autonomous Prefecture (Figure 6B).

Figure 6.

Changes in the centroid shifts in (A) B. minax and (B) B. tsuneonis in China under four shared socioeconomic pathways (SSP).

4. Discussions

B. minax and B. tsuneonis are oligophagous pests that exclusively infest citrus species [39]. This study evaluates the effects of abiotic factors—including climate, topography, and vegetation cover—on their distribution. It further compares the suitable habitat ranges of both species, analyzes changes under various climate scenarios, and tracks spatial shifts in their distribution centroids. Results indicate that both species predominantly occupy regions south of the 0 °C isotherm during the coldest month. This contrasts with previous studies, which identified suitable habitats in non-citrus-growing areas such as Poyang Lake [22,26], and conversely, classified actual infestation areas such as Guangxi and Guangdong as unsuitable areas [21]. These discrepancies highlight substantial deviations from observed distributions. Moreover, this study identifies low-suitability habitats for both species in Medog County, Nyingchi City, Tibet. Situated on the eastern slopes of the Himalayas, Medog experiences a subtropical humid climate with mild winters, abundant summer rainfall, and an annual average temperature of 18–22 °C—conditions favorable for citrus cultivation [40]. By incorporating a rasterized map of citrus distribution in China (Figure S1) as a key environmental variable in the model, the study enhances the predictive accuracy of the distribution of these pests. It is crucial to implement targeted monitoring and control strategies for these fruit fly species in agricultural practice with particular attention to B. tsuneonis, to mitigate their impact on citrus production.

The distribution index of citrus plants is the primary environmental determinant influencing the suitable habitat distribution of B. minax and B. tsuneonis. Insects rely on specific hosts for survival and reproduction, and their distribution ranges are largely determined by host plant availability. Similar patterns have been observed, including the strong correlation between the distribution of Agromyzidae and host plant presence in Ningxia [41]. Both B. minax and B. tsuneonis are oligophagous pests dependent on citrus as their host, resulting in a distribution pattern closely aligned with citrus cultivation areas. Given that citrus is widely planted across southern China, B. minax and B. tsuneonis are consequently more prevalent in these regions. However, in certain citrus-growing areas such as Hainan, Beijing, and southern Yunnan, B. minax and B. tsuneonis were not predicted to find suitable habitats. These regions, therefore, require enhanced quarantine measures to prevent potential invasions.

Precipitation and temperature are key environmental factors influencing the occurrence of B. minax and B. tsuneonis. Precipitation affects pupal ground development (PGDs) indirectly by altering soil moisture. Zhang found that soil moisture at a depth of 12 cm favored the eclosion of B. minax, whereas conditions at 25 cm were unfavorable [42]. Subsequent studies by Lv suggested that moderate winter rainfall, corresponding to soil water content of 10–15%, supports the overwintering and eclosion of B. minax pupae [43], whereas excessively dry or wet conditions adversely affect eclosion rates and timing [44]. The minimum temperature of the coldest month (BIO 6) emerged as the third most influential factor for the distribution of B. minax and B. tsuneonis. Overwintering temperatures play a critical role, as they affect insect emergence in the following year [33]. Zhuo demonstrated that overwintering eggs of Apolygus lucorum (Hemiptera: Miridae) exit diapause completely after 65 days of exposure to 2 °C, with hatching rates positively correlated with the duration of cold treatment [45]. Similarly, Zhou found that low temperatures delay the development of B. minax diapause pupae, thereby ensuring synchronized emergence with food availability and improving survival rates [46]. In China, elevated temperatures may shorten the pupal diapause, potentially causing early emergence, food scarcity, and increased mortality. Luo and Chen identified temperature as the key ecological factor regulating B. minax pupal development [11]. A subsequent study estimated the developmental threshold temperature at 10.57 °C [47].

Topographic factors, particularly elevation, also indirectly influence PGDs. In China, B. minax and B. tsuneonis predominantly inhabit hilly regions at elevations ranging from 150 to 900 m [48]. High-altitude regions restrict their development due to low temperatures, while lowland plains often host smaller populations, likely due to intensive agricultural practices and the presence of natural enemies. In contrast, complex mountainous terrain provides sheltered microhabitats, including forests and weedy patches, which support adult survival.

Under future climate scenarios, projections from multiple models indicate an overall reduction in suitable habitat for B. minax and B. tsuneonis. Notably, under the SSP2–4.5 scenario, the suitable habitat for B. minax is projected to expand during the 2040–2060 period. This projected expansion underscores the importance of proactive monitoring and preventive measures in regions where habitat suitability is anticipated to rise. In contrast, projections for B. tsuneonis across all four Shared Socioeconomic Pathways (SSPs) suggest a gradual decline across high, moderate, and marginal suitability classes. Given its designation as a major quarantine pest in both domestic and international contexts, increased surveillance is essential throughout production and distribution processes. In eastern Sichuan, a particularly sharp transition is observed, as highly suitable habitat for B. tsuneonis shifts westward into a narrow zone of low suitability in the absence of an intermediate zone of moderate suitability. This abrupt transition could elevate the risk of localized invasion, consistent with the findings of Zhao [49]. Interestingly, under the high-emission SSP5–8.5 scenario, the contraction of moderate and high-suitability habitat is less pronounced than in other scenarios, suggesting that the impact of emission levels on the distribution of B. minax and B. tsuneonis may be relatively limited.

Changes in the citrus distribution index and the bioclimatic variable BIO14 under climate change play a critical role in shaping the potential geographic distributions (PGDs) of B. minax and B. tsuneonis. However, the citrus distribution index is projected to remain relatively stable over time. As a result, BIO14 emerges as the dominant factor driving shifts in the distributional centroids of these species. To elucidate the relationship between habitat suitability changes and BIO14, we mapped the 20 mm precipitation isoline for BIO14 under both current and future climate scenarios (Figure S2). Across all four climate scenarios, this isoline exhibits only minor spatial variation. Consequently, the geographic centroids of B. minax and B. tsuneonis exhibit minimal displacement. This relative stability is largely attributable to the stable distribution of citrus cultivation zones, which are closely associated with the presence of B. minax and B. tsuneonis and play a defining role in their geographic range. Therefore, enhanced orchard management strategies in China’s citrus-producing regions are essential to prevent the establishment and spread of B. minax and B. tsuneonis populations.

This study analyzed the relationship between the suitable habitats of B. minax and B. tsuneonis in China and various environmental factors using the MaxEnt ecological niche model. By incorporating citrus plant coverage as a key environmental variable, the model achieved higher accuracy and improved predictive performance compared to previous studies. These findings provide valuable scientific insights for forecasting species distributions and developing targeted management and control strategies. At present, B. minax and B. tsuneonis are primarily distributed in southern Chinese provinces, where citrus cultivation is widespread. The spatial distribution of citrus plants plays a pivotal role in shaping the geographical range of these fruit flies. Across all climate scenarios, B. tsuneonis exhibits a consistent trend of habitat contraction. Higher greenhouse gas emission scenarios appear to contribute to a reduction in B. minax and B. tsuneonis suitability, potentially aiding in pest control. Nevertheless, regions engaged in citrus production—particularly eastern Sichuan—should implement enhanced management measures to prevent the invasion and spread of B. minax and B. tsuneonis. However, this study does not incorporate the potential effects of adaptive evolutionary processes, nor does it account for human-mediated dispersal mechanisms, such as long-distance jump dispersal via seedling or plant material transport. The omission of these processes constitutes a significant source of uncertainty in the predictive outcomes and should be considered a priority for refinement in future research, thereby supporting the citrus industry’s sustainable and resilient development in China.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/insects16121277/s1, Figure S1: Image of Citrus L. index in China; Figure S2: 20 mm contour of BIO14 under four shared socioeconomic pathways (SSP).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.W.; Methodology, Y.W.; Software, Y.W. and Z.W.; Validation, Y.W.; Formal analysis, C.L. and Z.W.; Investigation, Y.W., C.L. and Z.Y.; Resources, C.L., Z.Y. and Z.W.; Data curation, Y.W.; Writing—original draft, Y.W.; Writing—review & editing, Y.W., C.L. and Z.W.; Visualization, Y.W.; Supervision, C.L., Z.Y. and Z.W.; Project administration, C.L.; Funding acquisition, C.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Key R&D Program of China (Grant No. 2024YFC2607600).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Materials. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the reviewers and the editor for their valuable comments and suggestions, all of which greatly helped us in improving this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- White, I.M.; Wang, X.J. Taxonomic notes on some dacine (Diptera: Tephritidae) fruit flies associated with citrus, olives, and cucurbits. Bull. Entomol. Res. 1992, 82, 275–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, F.M.; Li, D.S.; Zhang, B.X. Major citrus diseases and insect pests of citrus in China. Chin. J. Biol. Control 2007, S1, 87–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Houdt, J.K.; Breman, F.C.; Virgilio, M.; DEMeyer, M. Recovering full DNA barcodes from natural history collections of Tephritid fruit flies (Tephritidae, Diptera) using mini barcodes. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 2010, 10, 459–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.X.; Xie, Y.Z. On the taxonomic name and species characteristics of Dacus dorlisa. Acta Entomol. Sin. 1955, 1, 123–126. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, L.; Zhou, Q.; Song, A.Q.; You, K.X. Adult oviposition and larval feeding preference for different citrus varieties in Bactrocera minax (Diptera: Tephritidae). Acta Entomol. Sin. 2014, 57, 1037–1044. [Google Scholar]

- Mochizuki, M.T.; Arai, T.; Mishiro, K.; Okazaki, Y.; Higashiura, Y. Control of the Japanese orange fly, Bactrocera tsuneonis (Diptera: Tephritidae), through several preharvest management practices: Establishment of a phytosanitary measure for citrus fruits for export. Appl. Entomol. Zool. 2024, 59, 317–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiraki, T. A Systematic Study of Trypetidae in the Japanese Empire; Memoirs of the Faculty of Science and Agriculture; Taihoku Imperial University: Taipei, Taiwan, 1933; Volume 8, pp. 1–509. [Google Scholar]

- Gong, X.Z.; Chen, W.H.; Bai, Z.L.; Gan, X.J.; Niao, Y.M. Effects of attractants on the trapping of Bactrocera (Tetradacus) tsuneonis (Miyake). Plant Quar. 2008, 22, 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Catalogue of Quarantine Pests for Imopont Plants to the People’s Republic of China 2007. Available online: https://view.officeapps.live.com/op/view.aspx?src=https%3A%2F%2Fassets.ippc.int%2Fstatic%2Fmedia%2Ffiles%2Freportingobligation%2F2025%2F01%2F07%2FCATALOGUE_OF_QUARANTINE_PESTS_FOR_IMPORT_PLANTS_TO_THE_PEOPLES_REPUBLIC_OF_CHINA_updated_20241128.doc&wdOrigin=BROWSELINK (accessed on 25 November 2025).

- List of National Quarantine Pests of Agricultural Plants 2024. Available online: https://www.moa.gov.cn/govpublic/ZZYGLS/202409/t20240903_6461714.htm (accessed on 25 November 2025).

- Luo, L.Y.; Chen, C.F. Biological characteristics of Dacus dorsalis pupae (Oriental Fruit Fly) on citrus. China Citrus 1987, 4, 9–10. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, W.Z.; Su, Y.; Zeng, L.Y.; Zhang, Y.; Ullah, F.; Wang, X.L.; Li, X.N.; Feng, X.D.; Li, Z.H. LAMP assay as a rapid identification Technique of Chinese citrus fly and Japanese orange fly (Diptera: Tephritidae). J. Econ. Entomol. 2023, 116, 956–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, L.Y.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, W.Z.; Zeng, Y.Y.; Jiang, F.; Qin, Y.J.; Zhang, J.F.; Jiang, Z.C.; Hu, W.Z.; Guo, D.J.; et al. New Species-Specific Primers for Molecular Diagnosis of Bactrocera minax and Bactrocera tsuneonis (Diptera: Tephritidae) in China Based on DNA Barcodes. Insects 2019, 10, 447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Chambi, C.; Li, Z.; Huang, C.; Ma, Y.; Li, C.; Tian, X.; Sangija, F.; Ntambo, M.S.; Kankonda, O.M.; et al. Influence of supplemental protein on the life expectancy and reproduction of the Chinese citrus fruit fly, Bactrocera minax (Enderlein) (Tetradacus minax) (Diptera: Tephritidae). J. Insect Sci. 2018, 18, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.S.; Zhao, C.D.; Li, H.X.; Lou, H.Z.; Liu, Q.R.; Kang, W.; Hu, J.G.; Zhang, H.Q.; Chu, J.M.; Xia, D.R.; et al. Effectiveness of the sterile tnsect Technique in controlling the oriental fruit fly (Bactrocera dorsalis). J. Nucl. Agric. Sci. 1990, 3, 135–138. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.Y.; Liang, S.S.; Liang, X.M.; Wang, X.J.; Bai, X.C.; Chen, Y.L.; Wu, K.J.; Liu, X.M.; Dong, Z.H.; Tan, Q.; et al. The carbon footprint and ecological costs of citrus production in China are going down. J. Clean. Prod. 2025, 496, 145124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Fan, H.; Li, Y.; Zhang, T.F.; Liu, Y.H. Trehalose-6-phosphate phosphatases are involved in the trehalose synthesis and metamorphosis in Bactrocera minax. Insect Sci. 2022, 29, 1643–1658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, H.; Liu, S.; Zheng, L.; Zhong, J. Research on Navel Orange Safety Production Information Management System. In Computer and Computing Technologies in Agriculture V. CCTA 2011; Li, D., Chen, Y., Eds.; IFIP Advances in Information and Communication Technology; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012; Volume 368, pp. 97–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, H.; Meng, X.; Liu, S. The Study on Navel Orange Traceability Chain. In Computer and Computing Technologies in Agriculture IV. CCTA 2010; Li, D., Liu, Y., Chen, Y., Eds.; IFIP Advances in Information and Communication Technology; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; Volume 346, pp. 179–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merow, C.; Silander, J. A comparison of Maxlike and Maxent for modelling species distributions. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2014, 5, 215–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, C.; Wang, X.; Huang, T.T.; Wang, R.L. Future habitat changes of Bactrocera minax Enderlein along the Yangtze River Basin using the optimal MaxEnt model. PeerJ 2023, 11, e16459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, J.X.; Meng, F.H.; Song, Y.Z.; Li, D.L.; Ji, Q.G.; Hong, Y.C.; Lin, J.; Cai, P.O. Forecasting the expansion of Bactrocera tsuneonis (Miyake) (Diptera: Tephritidae) in China using the MaxEnt model. Insects 2024, 15, 417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GBIF Occurrence Download. Available online: https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.5ugbmt (accessed on 7 November 2024). [CrossRef]

- Molloy, S.W.; Davis, R.A.; Van Etten, E.J.B. Species distribution modelling using bioclimatic variables to determine the impacts of a changing climate on the western ringtail possum (Pseudocheirus occidentals; Pseudocheiridae). Environ. Conserv. 2014, 41, 176–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GBIF Occurrence Download. Available online: https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.8w2g5u (accessed on 29 March 2025). [CrossRef]

- Barbet-Massin, M.; Jiguet, F.; Albert, C.H.; Thuiller, W. Selecting pseudo-absences for species distribution models: How, where and how many? Methods Ecol. Evol. 2012, 3, 327–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crego, R.D.; Stabach, J.A.; Connette, G. Implementation of species distribution models in Google Earth Engine. Divers. Distrib. 2022, 28, 904–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.Y.; Xiao, N.W.; Shen, M.; Li, J.S. Comparison between optimized MaxEnt and random forest modeling in predicting potential distribution: A case study with Quasipaa boulengeri in China. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 842, 156867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.Y.; Wang, Z.G.; Sun, J.; Xi, S.X.; Wei, X.; Huang, Q.W.; Zhou, C.Z. Surrogate model of solved poisson Kriging method for radiation field reconstruction. Nuclear. Technol. 2025, 211, 332–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malakar, A.; Pradhan, M.; Garai, S.; Sinha, A. Azadirachta indica A. Juss evinced robust resilience to changing climate under shared socioeconomic pathway scenarios in Eastern India. Clim. Change 2025, 178, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warren, D.L.; Matzke, N.J.; Cardillo, M.; Baumgarther, J. ENMTools 1.0: An R package for comparative ecological biogeography. Ecography 2021, 44, 504–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, M.H. Confronting multicollinearity in ecological multiple regression. Ecology 2003, 84, 2809–2815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, M.; Tang, Q.Z.; Huang, D.J. Analysis of Climate Resources in the head area of the Three Gorges Reservoir and its impact on local water resources. Yangtze River 2024, 55, 63–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, H.; Das, N.; Pal, S.; Pal, S.C.; Mandal, S. Predicting the potential habitat suitability of mangrove bioindicator species- Telescopium telescopium (Linnaeus, 1758) through MaxEnt modelling. Reg. Stud. Mar. Sci. 2025, 83, 104073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swets, J.A. Measuring the accuracy of diagnostic systems. Science 1988, 240, 1285–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emmerling, J.; Kormek, U.; Zuber, S. Multidimensional welfare indices and the IPCC 6th Assessment Report scenarios. Ecol. Econ. 2024, 220, 108182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Qin, D.H.; Liu, H.B. Introduction to treatment of uncertainties for IPCC fifth assessment report. Adv. Clim. Change Res. 2012, 8, 150. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, Q.L.; Xu, X.T.; Mao, K.S.; Wang, M.C. Shifts in plant distributions in response to climate warming in a biodiversity hotspot, the Hengduan Mountains. J. Biogeogr. 2018, 45, 1334–1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, P.H.; Wang, Y.H.; Akami, M.; Niu, C.Y. Identification of olfactory genes and functional analysis of BminCSP and BminOBP21 in Bactrocera minax. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0222193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.R.; Zhao, T.N.; Liu, L.H. Adjustment and prospect of the agricultural and livestock configuration in Linzhi Region, Tibet. Res. Soil Water Conserv. 2023, 10, 199–202. [Google Scholar]

- Huo, B.W.; Yuan, S.W.; Ye, F.Y.; Du, S.J.; Wan, W.J.; Guo, J.Y.; Wan, F.H.; Zhou, H.X.; Liu, W.X. Survey of the species and damages of agromyzid Leaf miners and their natural enemy parasitoids in Ningxia Region. J. Trop. Biol. 2025, 16, 327–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.Y. Studies on Biology, Behavior and Control of Bactrocera minax. Master’s Thesis, Huazhong Agricultural University, Wuhan, China, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Lv, Z.Z.; Zhao, Y.C. Emergence, mating, and oviposition behavior of Bactrocera minax in the Three Gorges Valley region. Chin. Bull. Entomol. 2007, 44, 277–279. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.F. Research on Biological Characters and the Integrated Control Technique of Bactrocera (Tetradacus) minax (Enderlein). Master’s Thesis, Hunan Agricultural University, Guangzhou, China, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Zhuo, D.G.; Li, Z.H.; Men, X.Y.; Yu, Y.; Zhang, A.S.; Li, L.L.; Zhang, S.C. Effects of low temperature and photoperiod on diapause termination and developmental duration of the overwintering egg of Apolygus lucorum Meyer-Dür (Hemiptera: Miridae). Acta Entomol. Sin. 2011, 54, 136–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.X.; Xia, Z.Z.; Yuan, J.J.; Wang, Z.L.; Li, C.R. Effect of temperature on the energy metabolism and related enzyme activity of the Chinese citrus fruit fly, Bactrocera minax (Enderlein), during diapause. Chin. J. Appl. Entomol. 2019, 56, 454–462. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.T.; Dong, Y.C.; Li, K.Z.; Ni, S.B.; Niu, C.Y. Overview of the use of the sterile insect technique to control the Chinese citrus fruit fly. Chin. J. Appl. Entomol. 2013, 50, 848–852. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, J.R.; Yan, W.B.; Ran, F.; Zhang, Y.F. Sensitivity of different attractants to fruit fly and occurrence law of fruit fly. Plant Health Med. 2012, 25, 12–13. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Y.T. Risk analysis of Bactrocera tsuneonis invasion in Sichuan. China Plant Prot. 2021, 41, 76–78+100. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).