Simple Summary

Rice leaf folder, Cnaphalocrocis medinalis, is a devastating rice crop pest, and its evolving resistance to insecticides poses a substantial challenge to control efforts. The glucose–methanol–choline (GMC) oxidoreductase superfamily comprises important enzymes involved in various physiological processes in insects, but their specific roles in C. medinalis remain largely unknown. This study presents the first systematic identification of 54 GMC genes in this species, revealing an uneven chromosomal distribution of these genes, including a conserved tandem cluster of 12 genes. Expression profiling revealed most GMC genes to be transcriptionally active, and exposure to the insecticide spinetoram significantly altered the expression of several genes, with 20 upregulated and 8 downregulated. This suggests that specific GMC oxidoreductases may play key roles in the molecular response of C. medinalis to insecticide. Our findings provide valuable genetic resources and insights for exploring novel pest management strategies.

Abstract

The glucose–methanol–choline (GMC) oxidoreductase superfamily constitutes a crucial group of enzymes involved in diverse physiological processes in insects. However, a systematic investigation of this gene family in the rice leaf roller, Cnaphalocrocis medinalis—a major migratory rice pest—remains lacking. This study identified 54 CmGMC genes in C. medinalis. Genomic analysis revealed its uneven chromosomal distribution, with a conserved 12-gene tandem cluster on chromosome 23. Phylogenetic analysis classified the CmGMC genes into distinct clades, clarifying their evolutionary relationships with GMC homologs in other species. Furthermore, spatiotemporal expression profiling revealed expression of 36 CmGMC genes across all developmental stages and tissues examined, indicating the high transcriptional activity of GMC oxidoreductase genes in C. medinalis. To investigate their role in insecticide response, we examined changes in CmGMC expression following spinetoram treatment. At 48 h post treatment, 20 and 8 genes were significantly upregulated and downregulated, respectively, indicating that specific GMC oxidoreductases may play crucial roles in the molecular response of C. medinalis to spinetoram. This study provides a foundation for understanding the biological functions of GMC oxidoreductases in C. medinalis and reveals their response to the insecticide spinetoram.

1. Introduction

Redox reactions are crucial biochemical reactions in living organisms, with vital roles in sustaining biological processes such as metabolism [1] and respiration [2]. These processes also require catalysis by oxidoreductases. Based on analysis of sequences of glucose dehydrogenase from Drosophila melanogaster, choline dehydrogenase from Escherichia coli, glucose oxidase from Aspergillus niger, and methanol oxidase from Hansenula polymorpha, Cavener et al. designated enzymes featuring an N-terminal FAD-binding βαβ-fold domain composed of 30 amino acids as the glucose–methanol–choline (GMC) oxidoreductase superfamily [3]. Although the maximum sequence similarity among these enzymes is only 32%, and their diverse catalytic substrates range from various sugars and alcohols to cholesterol and choline, the overall reaction mechanisms of these oxidoreductases are still conserved [4,5,6].

The earliest functional studies of the GMC family primarily focused on lower organisms, such as Penicillium amagasakiense and Aspergillus niger [7]. More recently, an increasing number of GMC oxidoreductase genes have been identified in insects, the first being the glucose dehydrogenase gene in D. melanogaster [3]. More recently published research on GMC family gene functions has mainly focused on glucose oxidase, NinaG, and ecdysone oxidase, among family members. Glucose dehydrogenases participate in glucose metabolism, catalyzing the conversion of glucose to glucono-d-lactone [8]. They also play important roles in egg development in Aedes aegypti [9], reproduction in the brown planthopper (Laodelphax striatellus) [10] and Drosophila [11], lifespan in Anopheles stephensi [12] and Drosophila [13], and immunity in Manduca sexta [14,15]. Glucose oxidase has also been implicated in insect feeding [16,17] and insect–plant interactions [18,19]. The NinaG oxidoreductase gene (belong to GMC family) is required for the synthesis of visual pigments in insect visual systems [20,21,22]. Ecdysone regulates developmental transitions in insects, and ecdysone oxidase is a key enzyme that modulates ecdysone titers [23]. Ecdysone oxidase PxEO in the diamondback moth, Plutella xylostella, is associated with Resistance to the bacterially derived Bt Cry1Ac toxin [24]. Ecdysone oxidase in Drosophila is linked to cell death through autophagy [25] and the response to malnutrition [26]. Additionally, expression of ecdysone oxidase in silk moth (Bombyx mori) oocytes influences the egg hatch rate of their offspring [27].

With the continuous advancement of genome sequencing technology, the identification of GMC family members has become increasingly more comprehensive. Genomic analyses of D. melanogaster, A. gambiae, Apis mellifera, and Tribolium castaneum have revealed varying numbers of GMC oxidoreductase family members (15, 15, 18, and 23, respectively). Most of these genes are arrayed in tandem within the introns of the flotillin-2 gene. This tandem gene cluster exhibits high conservation across diverse insect taxa, suggesting critically important functions for GMC family genes in insects. In D. melanogaster GMC family, 12 GMC genes are located in the tandem gene cluster [28]. In the silkworm genome, 43 GMC oxidoreductase genes have been identified, most of which were the apparent product of an expansion of the GMCβ subfamily, which is largely associated with immune function [29]. Similarly, 33 GMC genes were identified in the genome of the monarch butterfly (Danaus plexippus), another lepidopteran. Phylogenetic analysis of the GMC family in the lepidopteran species M. sexta, Pieris rapae, Chloridea virescens, Spodoptera litura, and D. plexippus has also revealed expansions within the GMCβ subfamily [30].

The rice leaf folder, C. medinalis, is a major migratory lepidopteran pest of rice. Its larvae roll and feed on leaf tissue, reducing photosynthesis and thus causing rice yield losses [31]. As a consequence of the extensive application of chemical insecticides to control such pests, the evolution of resistance poses a major challenge to sustainable agriculture [32,33]. Between 2019 and 2022, C. medinalis developed low to moderate resistance to abamectin, emamectin benzoate, and spinetoram and high resistance to chlorantraniliprole, with resistance ratios reaching 64.9–113.7 [34]. Consequently, Bt transgenic insect-resistant rice has garnered substantial attention [35,36]. Simultaneously, detoxification enzyme genes, such as cytochrome P450 monooxygenases (P450s) [37,38], glutathione S-transferases (GSTs) [39,40], and carboxylesterases (COEs) [41], have become very active research subjects [42].

Spinetoram is a bio-insecticide derived from natural products, which primarily acts on the nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs) and γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) receptors in insects, disrupting nervous system function through stomach and contact toxicity [43,44]. It is highly effective against lepidopteran pests and has been widely used for both field control and laboratory studies of C. medinalis [45,46]. However, the molecular mechanisms by which C. medinalis responds to spinetoram stress through its metabolic enzyme systems remain unclear. Therefore, this insecticide was selected in this study to investigate the potential role of GMC family genes in the detoxification process. The publication of the C. medinalis transcriptome [47] and genome [48] has enabled the identification and analysis of gene families in this important crop pest [49,50,51]. Utilizing these genomic data, the present study identified 54 GMC oxidoreductase genes in C. medinalis through various methods of analysis, including conserved domain analysis, chromosomal localization, and phylogenetic analysis. Spatiotemporal expression profiles of the GMC oxidoreductase gene family were also constructed. To investigate the potential role of GMC family genes in detoxification, we measured their expression levels following spinetoram treatment, revealing that 15 GMC oxidoreductase genes were upregulated and 3 were downregulated, which suggests these genes may play important roles in the response to spinetoram observed in C. medinalis.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Acquisition

Genomic data, protein data, and GFF files for the following 14 insect species were downloaded from the Insectbase website (http://v2.insect-genome.com/Organism/192 (accessed on 8 December 2024)). C. medinalis, B. mori, Ostrinia furnacalis, Monomorium pharaonis, Acromyrmex charruanus, Tenebrio molitor, Anoplophora glabripennis, Gryllus bimaculatus, Locusta migratoria, Eucriotettix oculatus, Bemisia tabaci, Nilaparvata lugens, Apolygus lucorum, and Ceratitis capitata. Protein databases for four species (D. melanogaster, A. gambiae, A. mellifera, T. castaneum) and GMC sequences for six species (Homo sapiens, Caenorhabditis elegans, A. niger, Penicillium amagasakiense, A. oryzae, E. coli) were also downloaded from the previous research [28] (https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2148-7-75 (accessed on 11 December 2024)). The Hidden Markov Model (HMM) profile (Pfam ID PF00732) used for identifying the GMC oxidoreductase family was obtained from the Pfam database (http://pfam.xfam.org/ (accessed on 11 December 2024)).

2.2. Identification and Nomenclature of GMC Oxidoreductase Genes

The protein annotation file of C. medinalis was screened using the HMM profile of the GMC family (PF00372) with TBtools (TBtools-II, Toolbox for Biologists, v2.086, Guangzhou, China) [52] at an E-value cutoff of 1E-5. Known GMC gene family sequences from D. melanogaster were used as query sequences for BLAST (TBtools v2.086) homology search against the C. medinalis protein database. The resulting sequences obtained via both methods were combined and redundant sequences were removed. Further filtering was performed using the Pfam website (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/interpro/entry/pfam/#table (accessed on 10 December 2024)). Finally, the conserved domains of the putative gene family members were verified using the NCBI CDD Search online tool (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Structure/bwrpsb/bwrpsb.cgi (accessed on 25 December 2024)). Sequences lacking the conserved GMC domain were identified as false positives and manually removed using TBtools. Annotation was further curated using IGV-GSAman software (v0.9.53), after which the final number of GMC genes in C. medinalis was ultimately determined. The identified genes were named sequentially according to their positional order along the chromosomes, arranged from the shortest to the longest chromosome. GMC genes in other species were identified according to the same methodology.

2.3. Analysis of Basic Information and Physicochemical Properties of the C. medinalis GMC Gene Family

Positional information on all GMC genes was obtained from the C. medinalis genome annotation file. Basic information, including chromosomal location, gene transcription start and stop sites, length, and strand orientation, was extracted using the GXF Gene Position & Info Extract function in TBtools. A series of amino acid physicochemical properties for each gene, including the number of amino acids, molecular weight, isoelectric point (pI), instability index, aliphatic index, and grand average of hydropathicity (GRAVY), were determined from the nucleotide sequences using the Protein Parameter Calc program.

2.4. Chromosomal Localization, Motif, and Conserved Domain Analysis of the C. medinalis GMC Gene Family

The chromosomal positions of all GMC genes were obtained from the C. medinalis genome annotation file and visualized using the Gene Location Visualize from GTF/GFF tool in TBtools. Motif analysis of the C. medinalis GMC gene family was performed using the MEME web tool (https://meme-suite.org/meme/ (accessed on 5 March 2025)) in conjunction with TBtools for visualization. Conserved domains were identified using the NCBI CDD database and Pfam and visualized using TBtools.

2.5. Phylogenetic Analysis of the C. medinalis GMC Oxidoreductase Family

A total of 134 GMC amino acid sequences were subjected to phylogenetic analysis. This set included sequences from six outgroup species (H. sapiens, C. elegans, A. niger, P. amagasakiense, A. oryzae, E. coli) and four model non-lepidopteran insects (D. melanogaster, A. gambiae, A. mellifera, T. castaneum), along with the sequences from C. medinalis. All sequences were aligned using the CLUSTALW method implemented in MEGA12 (v12.1.1) [53]. A phylogenetic tree was constructed with MEGA12 as well as using the maximum likelihood method with the LG + G + I model, with 1000 bootstrap replicates [54,55,56,57]. The resulting tree was subsequently visualized using the ITOL web tool (https://itol.embl.de/ (accessed on 11 September 2025)).

2.6. Spatiotemporal Expression of CmGMC Oxidoreductase Family Genes

Approximately 200 eggs, 10 first-instar larvae, six second-instar larvae, three third-instar larvae, three fourth-instar larvae, three fifth-instar larvae, three prepupae, three pupae, three female adults, and three male adults were collected into 2 mL cryotubes. Third-instar larvae were dissected to collect specific samples of the head, epidermis, body fluid, sericterium, gut and Malpighian tubule into 2 mL cryotubes. All 48 samples were flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C until their later analysis. Each treatment included three biological replicates. RNA was extracted using the TRIzol method (TaKaRa, Dalian, China), and cDNA was synthesized following the instructions of the PrimeScript™ RT Reagent Kit with gDNA Eraser (Perfect Real Time) (TaKaRa). Primers for GMC family genes, designed from the C. medinalis genome sequence using Primer5 software (v5.0), and reference genes (β-actin and RPs 15 [47]) are listed in Table A1. PCR amplification was performed using Novozan 2× Rapid Taq Master Mix (Vazyme, Nanjing, China). Each 25 μL reaction contained 12.5 μL of Master Mix, 2 μL of cDNA template (100 ng/μL), 1 μL each of forward and reverse primer (10 μM), and 8.5 μL of sterilized water. Amplification was conducted with a thermal cycling (LTC-PCR-196; LABGIC, Puchong, Malaysai) according to the following program: 94 °C for 2 min; 30 cycles of 94 °C for 30 s, 60 °C for 30 s, 72 °C for 1 min; and a final extension at 72 °C for 10 min with the reaction held at 4 °C thereafter. After amplification, the PCR products were checked by agarose gel electrophoresis and imaged using a gel documentation system (QuickGel 6200, Monad, Wuhan, China).

2.7. Insecticide Treatment

A laboratory-reared population of C. medinalis (This population was donated by the laboratory of Professor Liu Xiangdong at Nanjing Agricultural University. It was collected in 2010 from rice fields in Nanjing, China, and has been maintained in the laboratory to date. The rearing conditions were carried out according to the method by Zhu et al. [58]) was treated with insecticide. Third-instar larvae were treated using the leaf-dipping method. Wheat leaves (15–20 cm long) were cut from plants and immersed in 0.06 mg/mL (LC25) and 0.12 mg/mL (LC50) (Table A2) solutions of spinetoram (Dow AgroSciences, Nantong, China) for 30 s and then air-dried. For the control (CK) treatment, wheat leaves were instead immersed in water. A total of 270 third-instar larvae were collected for treatment. Thirty larvae were placed on each insecticide-treated or control wheat leaf. Each treatment included three replicates. Larval survival rates were recorded at 2, 4, and 6 d post treatment. Survival was determined based on the ability of an individual larva to turn itself over when placed on its back with a small brush. Pupation rate and eclosion rate were also recorded.

2.8. Measurement of Relative Expression Levels of CmGMC Oxidoreductase Family Genes

Third-instar larvae were treated with spinetoram (Dow AgroSciences, Nantong, China) using the leaf-dipping method described above. One hundred and twenty third-instar larvae were collected; thirty larvae were placed on each insecticide-treated or control wheat leaf. Surviving larvae were collected into 2 mL grinding tubes at 3, 24, and 48 h post treatment, flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80 °C for later use. Each treatment included three biological replicates (tubes), with each tube containing three larvae. RNA extraction was performed using the RNAiso Plus kit (TaKaRa), and cDNA synthesis was conducted using the PrimeScript™ FAST RT reagent Kit with gDNA Eraser (TaKaRa) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The relative expression levels of GMC family genes were determined using the TB GREEN Premix Ex Taq Kit (TaKaRa) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) was performed using an Applied Biosystems by Thermo Fisher Scientific QuantStudio™ 1 Real-Time PCR Instrument (96-Well 0.2 mL Block; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Primers for GMC family genes are listed in Table A1. The relative expression levels were calculated using the 2(−ΔΔCt) method [59]. Each sample was run with three technical replicates.

2.9. Data Analysis

Data are presented as mean ± standard error (SE). Survival rate, pupation rate, eclosion rate, and gene expression data were analyzed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by Tukey’s test. Before ANOVA, the Shapiro–Wilk test and Levene’s test were used to confirm the normality of data distribution and the homogeneity of variances, respectively. Gene expression data that did not meet the normality assumption were square-root transformed. The significance level was set at α = 0.05 and α = 0.01. All statistical analyses were performed using DPS18.10 software [60].

3. Results

3.1. Identification of the GMC Gene Family in Cnaphalocrocis medinalis

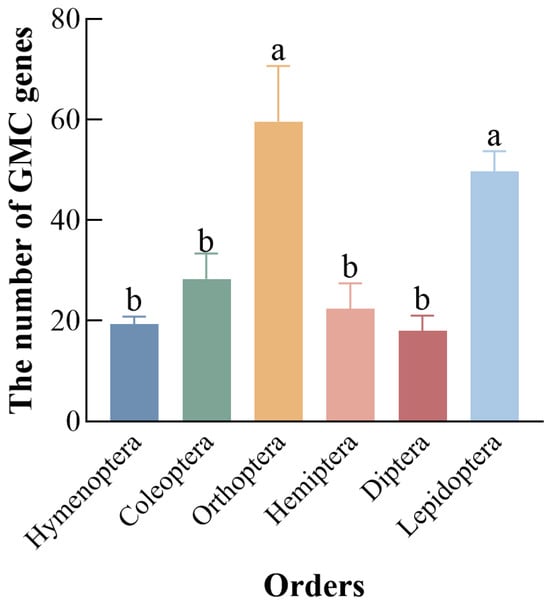

Screening using HMMs and local BLAST identified 50 GMC genes in the C. medinalis. The 50 initially identified GMC genes in C. medinalis were assigned names CmGMC1 to CmGMC50 based on their chromosomal locations and positions. Conserved domain analysis revealed that CmGMC13 lacked the characteristic GMC family conserved domain, indicating it does not actually belong to this family, despite its sequence similarity; consequently, it was excluded from subsequent analyses. Furthermore, we suspected potential mis-annotation related to over-splicing for CmGMC17 and CmGMC27, as they contained multiple conserved domains. Using transcriptome data for correction with IGV-GSAman (v0.9.53), CmGMC17 was split into four genes (CmGMC17-1, CmGMC17-2, CmGMC17-3, CmGMC17-4), and CmGMC27 was split into three genes (CmGMC27-1, CmGMC27-2, CmGMC27-3), resulting in complete C- and N-terminal subsequences for the split genes. Thus, the final number of GMC gene family members in C. medinalis was determined to be 54 (Table A3). Among hymenopterans, 18, 21, and 19 GMC genes were identified in A. mellifera, M. pharaonis, and A. charruanus, respectively. There are 23, 29, 33 GMC genes in T. castaneum, T. molitor, A. glabripennis separately among Coleoptera, while in Orthoptera, 49, 59, and 71 genes were identified in G. bimaculatus, L. migratoria, and E. oculatus, respectively. Additionally, in Hemiptera, 28, 21, and 28 genes were found in B. tabaci, N. lugens, and A. lucorum, respectively, while among dipterans, 21, 15, and 18 genes were identified in C. capitata, D. melanogaster, and A. gambiae, respectively. In the lepidopteran species B. mori and O. furnacalis, 49 and 46 GMC family genes were identified, respectively (Figure 1). A comparison of the number of GMC homologs among six common insect orders revealed their greater abundance in Orthoptera (60), Lepidoptera (49), and lower abundance in Coleoptera (28), Hymenoptera (19), Hemiptera (25), and Diptera (18).

Figure 1.

Number of GMC oxidoreductase genes across six insect orders. Different letters above bars indicate significant differences between groups according to Tukey’s test (p < 0.05). Data represent mean ± SE of n = 3.

3.2. Physicochemical Properties of the C. medinalis GMC Gene Family

Analyzing the physicochemical properties of proteins is crucial for understanding their functions and potential applications that take advantage of these functions, e.g., in pest control; the physicochemical properties of the C. medinalis GMC gene family were thus analyzed using TBtools. The results indicated that the amino acid sequence lengths of the 54 CmGMC proteins ranged from 124 (CmGMC40) to 1036 (CmGMC10), with molecular weights of 13,947.8 Da (CmGMC40) to 127,085.0 Da (CmGMC10) and isoelectric points (pI) of 4.62 (CmGMC14) to 9.67 (CmGMC33) (Table 1). Among homologs, 25 proteins had a pI greater than 7, classifying them as basic proteins, while the remaining 29 had a pI less than 7, classifying them as acidic proteins. The instability index values ranged from 10.0 (CmGMC44) to 50.3 (CmGMC39). Fourteen CmGMC proteins had an instability index value exceeding 40, indicating relatively poor stability, while the remaining 40 proteins had an instability index value less than 40, indicating their relatively stable structural properties. The aliphatic index overall ranged from 61.3 (CmGMC44) to 105.1 (CmGMC21), with 11 CmGMC proteins having an aliphatic index value greater than 90, indicating their high thermal stability. The grand average of hydropathicity (GRAVY) was less than 0 for all 54 CmGMC proteins, classifying all of them as hydrophilic proteins.

Table 1.

Analysis of physical and chemical properties of the GMC Genes of Cnaphalocrocis medinalis.

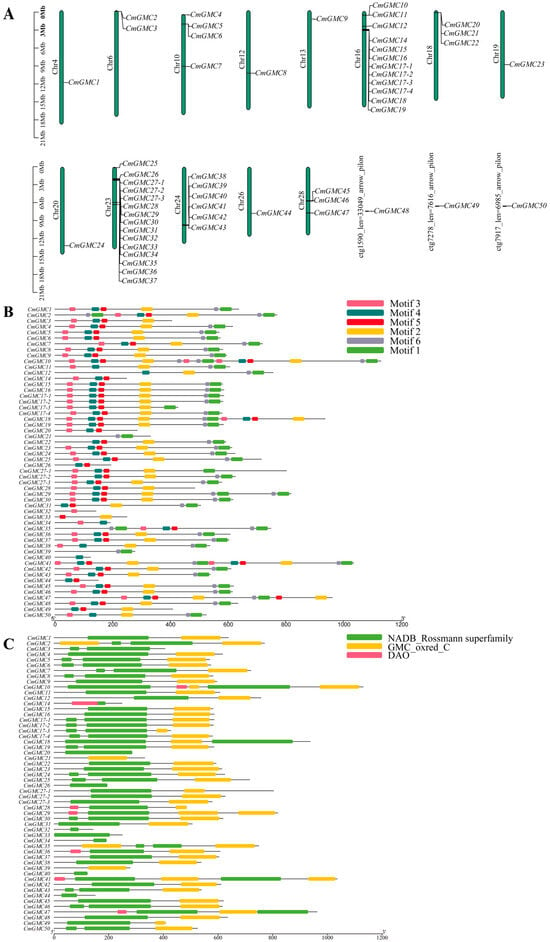

3.3. Chromosomal Localization, Motif, and Conserved Domain Analysis of GMC Genes in C. medinalis

The 54 CmGMC genes were unevenly distributed across 13 chromosomes and three unplaced scaffolds. Three genes (CmGMC48, CmGMC49, CmGMC50) were each located on different unplaced scaffolds, while the remaining genes were mapped to assembled chromosomes. Multiple genes were located on chromosomes 6, 10, 16, 18, 23, 24, and 28 (Figure 2A); with the exception of chromosome 28, the other six chromosomes contained gene clusters. Chromosome 16 contained two gene clusters, while the other aforementioned chromosomes contained only one cluster each. The gene cluster on chromosome 23 contained 12 genes (CmGMC26 to CmGMC35), representing the largest GMC gene cluster in the C. medinalis genome. Gene lengths ranged from 431 bp (CmGMC32) to 27,552 bp (CmGMC47) (Table A3). Four shorter genes (CmGMC32, CmGMC33, CmGMC39, CmGMC44) had lengths of less than 1 kb; such genes might encode small functional RNAs or short peptides or have important regulatory functions. Additionally, eight genes (CmGMC10, CmGMC25, CmGMC29, CmGMC36, CmGMC37, CmGMC41, CmGMC45, CmGMC47) were longer than 10 kb; these genes might be involved in complex functions, such as encoding large proteins that participate in various biological processes.

Figure 2.

Bioinformatics analysis of the GMC gene family of Cnaphalocrocis medinalis. (A) Chromosome localization analysis, (B) motif analysis, and (C) conserved domain analysis were conducted on 54 GMC oxidoreductase family genes of C. medinalis using TBtools. Conserved motif analysis of the GMC gene family proteins. The figure displays six conserved motifs, with boxes of different colors representing distinct motifs and their respective positions and lengths within the protein sequences. Conserved domain analysis of the GMC gene family proteins. The green boxes represent the NADB_Rossmann superfamily domain, the yellow boxes represent the GMC_oxred_C domain, and the red boxes represent the DAO domain. The lengths of the domains are depicted proportionally to their occurrence in the protein sequences.

Similar motifs often indicate similar functions. Motif analysis identified six potentially functional motif modules (Figure 2B). Thirty-three genes contained all six motifs. Only four genes (CmGMC21, CmGMC32, CmGMC33, CmGMC39) lacked motif 4. Furthermore, motifs 2 and 6 were always found together, suggesting these two motifs might function cooperatively or even belong to the same functional module.

The GMC gene family typically contains two main conserved domains: the NADB_Rossmann superfamily and the GMC_oxred_C domain (Figure 2C), each containing an active site. In C. medinalis, 43 genes contained both of these conserved domains. CmGMC21 and CmGMC39 contained only the GMC_oxred_C domain, which is located at the C-terminus of the enzyme and is primarily involved in binding flavin adenine dinucleotide (FAD) and the oxidation of substrates. Nine genes (CmGMC3, CmGMC14, CmGMC20, CmGMC26, CmGMC32, CmGMC33, CmGMC34, CmGMC40, and CmGMC44) contained only the NADB_Rossmann superfamily domain, which contains the Rossmann fold, a highly conserved structure that binds NAD+, suggesting these genes might primarily participate in reduction reactions.

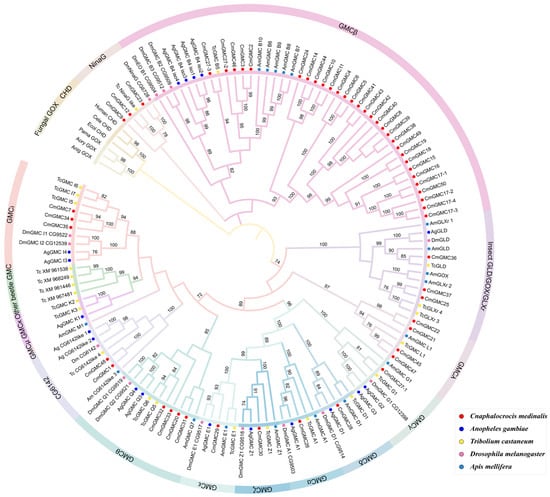

3.4. Phylogenetic Analysis of the C. medinalis GMC Oxidoreductase Family

A phylogenetic tree was constructed using GMC oxidoreductase genes from five species: C. medinalis, D. melanogaster, T. castaneum, A. gambiae, and A. mellifera. The tree comprised three major groups (Figure 3). The first group primarily consisted of genes from distantly related outgroups that included bacteria and mammals, indicating that insect GMC genes are very dissimilar from those in bacteria and fungi and thus may have an independent origin. The entire β subfamily and the NinaG subfamily formed the second group. The NinaG subfamily is the most closely related to the β subfamily among all 15 subfamilies; within the clustered genes in this group, three out of five genes were from C. medinalis, indicating the growth of this subfamily in Lepidoptera. Thirty of the 54 C. medinalis GMC genes were determined to be within the β subfamily. This group contained three smaller subgroups, one of which contained 24 C. medinalis genes, indicating that the expansion of the GMC family in C. medinalis primarily originated from the expansion of the β subfamily. The third group contained 13 subfamilies. Three of these subfamilies (GMCκ, Other beetle GMC, GMCμ) contained no C. medinalis GMC genes. The GMCκ subfamily contained two genes from T. castaneum and one from A. gambiae. The ‘Other beetle GMC’ subfamily consisted mainly of GMC genes from the coleopteran T. castaneum, and these two subfamilies were closely related phylogenetically, primarily comprising beetle GMC genes. This suggests that the functional differentiation of these two subfamilies might have occurred during the evolution of Coleoptera. The GMCμ subfamily was unique, containing only a single gene belonging to A. mellifera, suggesting this gene is functionally conserved within this lineage. The remaining ten subfamilies contained varying numbers of CmGMC genes (one to four each). The 12 genes from the conserved gene cluster (CmGMC26 to CmGMC35) were distributed across nine of these subfamilies (excluding CG6142), indicating that this gene cluster underwent multiple duplication events and diversified into multiple genes that were shaped and maintained by natural selection in the lineage leading to C. medinalis.

Figure 3.

Phylogenetic analysis of the GMC gene family. The phylogenetic tree was constructed using the maximum likelihood method in MEGA12 software (v12.1.1) with the LG + G + I model across 1000 bootstrap replicates; nodes with less than 70% bootstrap support are not shown. Solid circles of different colors represent different species, while the different subfamilies are indicated by color-coded branches and arcs surrounding the tree.

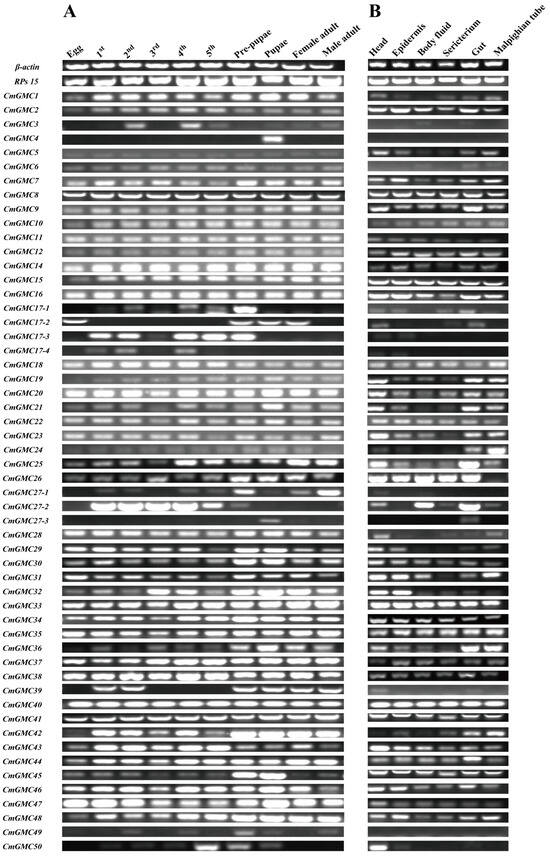

3.5. Spatiotemporal Expression Analysis of the GMC Gene Family

As indicated by phylogenetic analysis, the expansion of the GMCβ subfamily in C. medinalis led to the observed increase in GMC members. PCR detection of the 54 GMC genes indicated that most genes are indeed transcribed (Figure 4). Expression analysis of GMC genes across different developmental stages (egg, first through fifth instar larvae, prepupa, pupa, and male and female adults) and tissues (head, epidermis, body fluid, sericterium, gut, Malpighian tubule) of C. medinalis revealed that 38 CmGMC oxidoreductase genes were expressed across all stages and tissues, indicating high overall transcriptional activity of CmGMC genes in C. medinalis. CmGMC1 and CmGMC28 were expressed in all tissues except hemolymph, while CmGMC26 was expressed in all tissues except Malpighian tubules, suggesting these genes do not function in these respective tissues. CmGMC4 was expressed only in pupae, indicating this gene primarily has pupae-specific functions. CmGMC17-4 and CmGMC49 were not expressed in any of the six assayed tissues. In the temporal expression profile, only 43 genes were expressed in eggs, while 51 genes were expressed in fourth instar larvae (except CmGMC4, CmGMC39, and CmGMC27-3). In the spatial expression profile, the greatest number of expressed genes (49) was observed in the head (except CmGMC3, CmGMC4, CmGMC6, CmGMC17-4, and CmGMC49); while hemolymph showed the lowest (42).

Figure 4.

Spatiotemporal expression profiles of Cnaphalocrocis medinalis GMC genes. (A) Temporal expression profiles of CmGMC genes across different developmental stages; (B) Spatial expression profiles of CmGMC genes across different tissues.

3.6. Response of the C. medinalis GMC Family Genes to Spinetoram

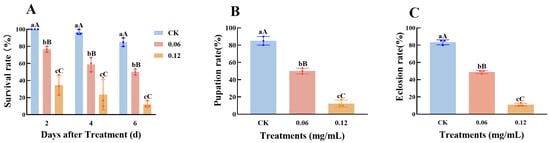

3.6.1. Biological Determination of Spinetoram on C. medinalis

Third-instar C. medinalis larvae were treated with spinetoram at concentrations of 0.06 and 0.12 mg/mL. Survival rates were significantly lower in the two spinetoram-treated groups compared to the control at 2 d post treatment (Figure 5A) and decreased further by 4 and 6 d post treatment. Survival rates were significantly higher in the 0.06 mg/mL treatment group compared to the 0.12 mg/mL group. Concurrently, pupation (Figure 5B) and eclosion rates (Figure 5C) in the treatment groups were also significantly lower than in the control group, with the eclosion rate being only 11% after 0.12 mg/mL treatment, indicating the strong toxicity of spinetoram against C. medinalis. The two different concentrations of spinetoram imposed distinctly different levels of stress on C. medinalis survival, with the 0.12 mg/mL dose inducing a significantly stronger toxic response than the 0.06 mg/mL dose. To more accurately assess the role of the GMC gene family in the response to spinetoram, we selected the 0.06 mg/mL concentration for subsequent gene expression analysis.

Figure 5.

Bioassay of third-instar Cnaphalocrocis medinalis larvae treated with spinetoram. (A) Survival rate of third-instar larvae following spinetoram treatment. (B) Pupation and (C) eclosion rates of C. medinalis after spinetoram treatment. Data represent mean ± SE of n = 3 biological replicates, with 30 larvae per replicate. Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences among time points according to Tukey’s test (p ≤ 0.05); Different capital letters indicate significant differences among time points according to Tukey’s test (p < 0.01).

3.6.2. The Relative Expression of CmGMC Against to Spinetoram in C. medinalis

As survival rates significantly decreased after spinetoram treatment, we measured the expression levels of all 54 CmGMC genes at 0, 3, 24, and 48 h post treatment (hpt) via qRT-PCR to identify genes that responded to spinetoram. Eight genes exhibited no significant difference in expression before and after treatment (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

The relative expression level of genes at different time points after insecticide treatment. Data represent mean ± SE of n = 3 biological replicates, with 3 larvae per replicate. Each data point represents the mean value calculated from two internal reference genes. Bars with same letter means “a” no significant difference among different time points according to Tukey’s test (p ≤ 0.05).

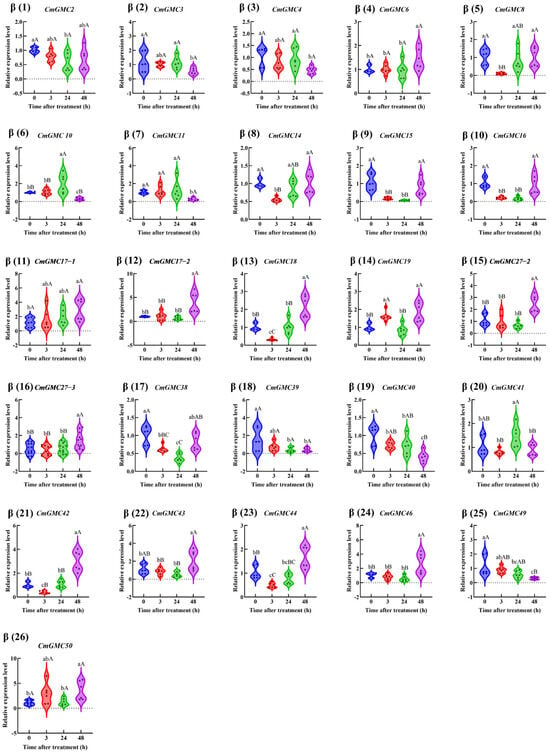

The remaining 46 genes were categorized according to their phylogenetic subfamilies. Within the β subfamily (Figure 7), the expression of ten genes (CmGMC8, CmGMC14, CmGMC15, CmGMC16, CmGMC18, CmGMC38, CmGMC40, CmGMC 42, CmGMC 44, CmGMC 49) was suppressed at 3 hpt. At 24 hpt, CmGMC10 and CmGMC41 expression increased significantly, CmGMC2, CmGMC15, CmGMC 16, CmGMC 38, CmGMC 39, CmGMC 40 expression decreased significantly. At 48 hpt, thirteen genes (CmGMC 6, CmGMC 17-1, CmGMC17-2, CmGMC18, CmGMC19, CmGMC27-2, CmGMC27-3, CmGMC42, CmGMC44, CmGMC46, CmGMC49, CmGMC 50) were actively transcribed, showing increased expression, while the expression levels of CmGMC 3, CmGMC4, CmGMC 10, CmGMC 11, CmGMC 39 and CmGMC40 decreased significantly. Thus, GMC gene expression was initially suppressed at 24 hpt after spinetoram treatment.

Figure 7.

The relative expression level of the GMCβ subfamily genes at different time points after insecticide treatment. Data represent mean ± SE of n = 3 biological replicates, with 3 larvae per replicate. Each data point represents the mean value calculated from two internal reference genes. Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences among time points according to Tukey’s test (p < 0.05). Different capital letters indicate significant differences among time points according to Tukey’s test(p < 0.01).

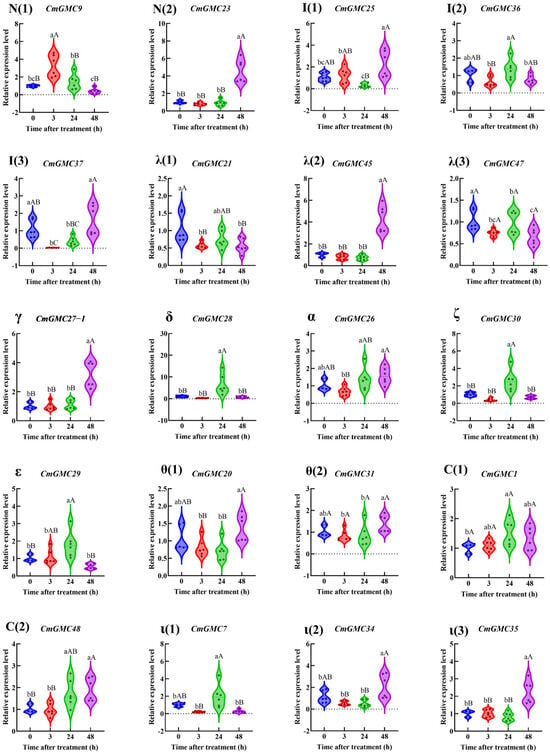

Within the remaining 11 subfamilies (Figure 8), a total of 20 genes showed altered expression. Among them, CmGMC9 exhibited increased expression at 3 hpt, while the expression levels of both CmGMC21, CmGMC37 and CmGMC47 decreased. At 24 hpt, the expression levels of CmGMC28, CmGMC29, CmGMC30, CmGMC1, CmGMC48 and CmGMC7 increased significantly. At 48 hpt, the expression levels of 7 genes (CmGMC23, CmGMC25, CmGMC45, CmGMC27-1, CmGMC48, CmGMC34 and CmGMC35) increased, suggesting that these 7 genes are primarily activated at 48 hpt when C. medinalis is affected by spinetoram toxicity, playing important roles after spinetoram enters the body.

Figure 8.

The relative expression level of GMC genes other than β subfamily genes at different time points after spinetoram treatment. Data represent mean ± SE of n = 3 biological replicates, with 3 larvae per replicate. Each data point represents the mean value calculated from two internal reference genes. Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences among time points according to Tukey’s test (p < 0.05). Different capital letters indicate significant differences among time points according to Tukey’s test (p < 0.01). Greek letters indicate the different subfamilies, with N (1–2) and I (1–3) denoting the NinaG and Insect GLD/GOX/GLXr subfamilies, respectively.

4. Discussion

The rice leaf folder, Cnaphalocrocis medinalis, is one of the three major pests that currently reduces rice production in Asia. However, as a consequence of the overuse of chemical control agents, pesticide resistance in this species has reached high levels in some regions. Notably, pesticide exposure often induces oxidative stress. To this end, we identified 54 GMC oxidoreductase family genes in the C. medinalis genome. As observed in other lepidopteran species, the GMCβ subfamily in C. medinalis showed dramatic expansion relative to other insects. By constructing spatiotemporal expression profiles of the GMC gene family, we found that most GMC genes are transcriptionally active, with 38 genes expressed across all developmental stages and tissues examined. Analysis of C. medinalis treated with a sublethal concentration of spinetoram (LC25, 0.06 mg/mL) revealed that 8 genes showed no change in expression, while at 48 hpt, 20 and 8 genes were upregulated and downregulated, respectively. These genes may play a key role in the defense of C. medinalis against spinetoram toxicity [29].

The variation in physicochemical properties may underlie their functional differentiation. Throughout evolution, the homologous copies of a single ancestral gene that originally arose through the processes of both gene duplication and speciation can become altered through base mutations, insertions, and deletions, leading to functional divergence and novel functions, thereby giving rise to gene families [61]. The occurrence of acidic and basic proteins within a gene family, resulting from duplication and divergence, is indicative of functional diversity. This phenomenon occurs in many gene families. For example, in the histone superfamily, core histones are primarily basic, whereas HMG proteins are acidic; they evolved from a single-copy ancestral protein into proteins with nearly opposite charges, related to their divergent functions [62,63]. The instability index was less than 40 for the majority of the C. medinalis GMC proteins, indicating good overall stability of these proteins in C. medinalis. This abundance of unstable proteins is relatively uncommon among insect gene families. For example, 17 out of 31 HSPs in Callosobruchus chinensis had an instability index less than 40 [64], and 10 out of 13 FMO proteins in Bursaphelenchus xylophilus had indices below 40 [65].

The GMC gene family is a large family primarily involved in redox reactions, which are among the most crucial reactions in biological organisms. The heterogeneity in motifs among family members underscores the functional diversity of this family [66]. An aliphatic index below 60 indicates a low proportion of aliphatic amino acids, high hydrophilicity, and relatively poor thermal stability; 60 to 90 is the common range for most natural proteins; an index greater than 90 indicates high hydrophobicity and high thermal stability [67]. The aliphatic indices of the C. medinalis GMC family genes ranged from 61.3 to 105.1, indicating their high thermal stability.

The number of GMC genes in C. medinalis is relatively high among species in which GMC genes have been identified [28]. This gene family was first discovered in bacteria, with subsequent discoveries in fungi and plants [5]. In recent years, GMC genes have been gradually identified in insects, particularly within Lepidoptera, where the GMC family shows substantial expansion relative to other insects. In the silkworm, B. mori, the GMC family comprises 43 genes as a consequence of the expansion of the β subfamily [9]. A total of 257 GMC genes have been identified across five lepidopteran species: S. litura, M. sexta, Pieris rapae, C. virescens, and D. plexippus [30]. In both D. melanogaster and B. mori, multiple GMC genes have been observed to be tandemly arrayed within the introns of the flotillin-2 gene [28,29]. We identified the Flotillin-2 gene on chromosome 23 using the HMM, but the C. medinalis gene cluster was not found to be located within this gene. Whether this is due to unique genes in C. medinalis or other underlying mechanisms remains to be explored. Phylogenetic analysis revealed that the C. medinalis genes are distributed among 12 different subfamilies, with the majority belonging to the β subfamily, which contains 30 genes. The 54 GMC genes in C. medinalis are unevenly distributed across 13 chromosomes and three unplaced scaffolds, with most genes forming gene clusters, indicating a history of tandem gene duplication events, primarily within the β subfamily.

Thus, the expansion of the GMC gene family was mostly associated with tandem duplication events. A similar phenomenon was observed in Parnassius glacialis, in which the NPC2 gene family underwent significant expansion through tandem duplication [68]. Furthermore, this phenomenon is widespread among other gene families; expansions in the odorant receptor (Or) and gustatory receptor (Gr) gene families in D. melanogaster [69], the UTP-glucose-1-phosphate uridylyltransferase (UGPase) gene family in Pseudoregma bambucicola [70], and the Tret gene family in B. mori [71] have primarily been driven by tandem gene duplication events. Similarly, detoxification enzyme gene families like P450s, GSTs, and UDP-glucuronosyltransferases underwent significant expansion in A. glabripennis, which is related to their ability to degrade complex defensive compounds in wood [72]. Pit vipers and pythons acquired the ability to detect infrared radiation, enabled by the expansion of a specific TRPA1 ion channel subfamily [73]. Similarly, we hypothesize that the expansion of the β subfamily in Lepidoptera may underlie its role in the adaptation of Lepidoptera to its environment. In insects, β subfamily genes are associated with development [30], stress resistance [74], and immunity [29], among other functions.

Determination of the spatiotemporal expression profile of GMC genes in C. medinalis revealed that most GMC genes are expressed across multiple stages and tissues, with consistently high transcriptional activity. This indicates that GMC genes likely play indispensable roles in C. medinalis. Similarly, gene families like ribosomal proteins and cytoskeletal proteins are widely expressed across all tissues in humans [75], as are members of the P450 gene family [76] and heat shock protein (HSP) family in insects [77]; they are involved in various crucial functions, such as growth, development, and stress resistance.

To further investigate the response of GMC genes in C. medinalis to insecticide, we measured the relative expression levels of these genes at 3, 24, and 48 h after spinetoram treatment. We found that the expression levels of multiple genes changed, with 20 GMC genes upregulated. This finding is consistent with observations in D. melanogaster [78], the brown planthopper (N. lugens) [79], and the whitefly (B. tabaci) [80], in which detoxification enzyme gene expression has been reported as upregulated under pesticide stress. These enzymes can rapidly degrade pesticides into non-toxic or less toxic substances and facilitate their excretion, thereby mitigating pesticide stress. This is also an important molecular mechanism of insecticide resistance in insects. The three main classes of detoxification enzyme gene families in insects are P450, GSTs, and CarEs [81]. P450s primarily introduce an oxygen atom into a substrate molecule, thereby increasing its water solubility and thus facilitating either the subsequent action of detoxification enzymes to process them or direct excretion [82]. The core function of GSTs is catalyzing the conjugation of glutathione with various electrophilic, hydrophobic toxic compounds, thus promoting their water solubility and subsequent excretion [83]. CarEs mainly act in two ways: firstly, hydrolases break down insecticides into non-toxic or less toxic acids and alcohols; secondly, CarE proteins preferentially bind to insecticide molecules, thus preventing them from reaching their target substrates [84]. Currently, there are no definitive published studies that conclusively identify specific GMC oxidoreductase genes responsible for insecticide detoxification. However, a previous study has shown that Jinggangmycin-induced reproductive inhibition in the small brown planthopper, L. striatellus, is mediated by GDH via synthesis metabolism of fatty acid pathways [10]. Gut regurgitant bacteria (Staphylococcus haemolyticus and Enterobacter) in the diamondback moth, P. xylostella, inhibit development of the moth by suppressing the expression of glucose oxidase [85]. Similarly, another study found that suppressing the expression of the 20-hydroxyecdysone (20E) degradation enzyme gene, glucose dehydrogenase (PxGLD), in the gut of P. xylostella can enhance the resistance of this insect species to Bt insecticidal proteins [86]. These genes all belong to the GMC oxidoreductase family, indicating the important roles of this family in insect defense against chemical agents. In C. medinalis, 15 GMC genes were upregulated and 3 GMC genes were downregulated in response to spinetoram treatment. Thus, spinetoram likely activates or suppresses the expression of these genes, thereby regulating the growth and development of C. medinalis under the stress induced by this chemical control agent.

5. Conclusions

We identified a total of 54 GMC oxidoreductase family genes in Cnaphalocrocis medinalis, most of which were determined to be transcriptionally active. Among this family, the β subfamily contains 30 genes. Treatment with a sublethal dose of spinetoram altered the expression of 26 genes. Whether the expansion of the GMCβ gene contributes to detoxification and resistance remains to be validated, and the underlying physiological, biochemical, and molecular mechanisms of their action require further investigation.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/insects16121272/s1.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.X., P.Q., Y.Z. and M.M.; methodology, C.X., H.L. and P.Q.; formal analysis, P.Q. and J.Z.; resources, X.Z., K.L. and M.M.; data curation, C.X., Y.Z. and P.Q.; writing—original draft preparation, C.X. and P.Q.; writing—review and editing, J.Z., C.X., K.L., D.Z. and M.M.; project administration, P.Q., Y.Z. and M.M.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2024YFD1400705), the Yuelushan Laboratory Breeding Program (YLS-2025-ZY04067), the Natural Science Foundation of Changsha City (kq2402145), and the Hunan Agricultural Science and Technology Innovation Project (2024CX101, 2024CX102).

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article and supporting file. The original data can be obtained by contacting the author via 13213502940@163.com.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our gratitude to Liu Xiangdong from Nanjing Agricultural University for providing the indoor source of Cnaphalocrocis medinalis.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| GMC | Glucose–Methanol–Choline |

| CmGMC | Glucose–Methanol–Choline of Cnaphalocrocis medinalis. |

| LC50 | Lethal Concentration 50 |

| hpt | hours post treatment |

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. Primers Used in the Study

The primers used in the article are all listed in Table A1. The primers were all designed in the Primer5 software.

Table A1.

Primers used in PCR and qRT-PCR.

Table A1.

Primers used in PCR and qRT-PCR.

| Gene | Forward Primer (5′→3′) | Reverse Primer (5′→3′) |

|---|---|---|

| β-actin | ATGGTCGGCATGGGACAG | GAGTTCATTGTAGAAGGTGT |

| RPs15 | ACGTACCCGCTTACAAACCC | TGACCAAGGTGAGCAACAGAG |

| CmGMC1 | GGAAGGGGCGGATACCTAGA | CCGTTCGGGTCTCTCCATTT |

| CmGMC2 | ATCGGTCTTCCATCCATTGAC | AAAAAACCACGAGCTGTGCTC |

| CmGMC3 | CAGGCCCCTCGTTTGACTTC | TAGGGTCGTCACCAGCTTCT |

| CmGMC4 | CAGGTGCCTTTGCGATTGTT | TTGCTTCCACTCGATCCACC |

| CmGMC5 | TATCGCCCCAATCTGCATG | TTTCCCGTTTGACAAAGCC |

| CmGMC6 | GAAGAATCCAACATTCTCCCCATTG | TATGTTGAACAGTCTTTGATCGTCG |

| CmGMC7 | GGAATCCCAGTCATTGCCGA | GGGCTCAAGTAAGCTGGCAT |

| CmGMC8 | TGCCAGTGCCATGCCTAAT | TGCGCCAGTGTCCTTTTTAA |

| CmGMC9 | TGCCAGTGCCATGCCTAAT | ATCAAAGTCCCGAGGGTTGC |

| CmGMC10 | GTCTGCCACTCGCAGTTTGT | GGGACTGCTAGAATGGGTGAT |

| CmGMC11 | GCTATCAATGGACGCGTTGG | GGTGGGCAGGCAAAGACATA |

| CmGMC12 | CTGGCATTTATTGGAGCCTCA | GCCCCCACTTTCACTATCTTG |

| CmGMC14 | CTTCATCGTTGTCGGAGCTG | CTATTGATTCCAAGGGTGGGT |

| CmGMC15 | GGTTGCAGATGGAATGCGTC | CTTTGTCGCCGTTGTGTGTT |

| CmGMC16 | TATGTGAGTACGTGTCGGATGG | GGTGTTACCGCTGGTGATGG |

| CmGMC17-1 | ACAACCACCTGCACATGACT | TCCCCAGTCATATCAGCCCA |

| CmGMC17-2 | TGCCTGGAACTACACCAACG | GCTCTTGTGACACCGACGTA |

| CmGMC17-3 | CGTTCGAGGAGACCCTTACG | GGATCTTCCAGCCTTTCGCT |

| CmGMC17-4 | ATGGCCTTCGTCAAGGTAGC | AGCTTGGACTGTGATGGTGT |

| CmGMC18 | AAACACCACCAACCCCCAT | CGACAAATCTTTAGCAAACGACAC |

| CmGMC19 | TTATGGAAGCCGTAGCTCGC | GGCATCTCCAATACTCCGCA |

| CmGMC20 | CGTCCCTACGAAAGACTACCG | CTCCCAACACCTTCCCAGAT |

| CmGMC21 | ATGAGCGATGTTGCTCCAGT | GGCGCACTAACGCTTTCATA |

| CmGMC22 | CTGAACGGAAACGATGGTTG | AAGGTCCCTGCGTGGAATG |

| CmGMC23 | TCGTATGTGTTCGCCGTTG | ATATCTCTTTTCCGCTTTCCCT |

| CmGMC24 | GATCGAGTCGGGGTTCCTT | CGCGCACACGCTTATAATAA |

| CmGMC25 | ATGCCCACAGTCGTTACTGG | ACTTCGGGACGGTTCTTCAC |

| CmGMC26 | TGCTGTTGGAAGCTGGTGG | CCTTGGGGCTCAGTCTTGTACT |

| CmGMC27-1 | ACAGCATGATGGAAGCGGAA | CAGCCCATTAGCTCGTTTGC |

| CmGMC27-2 | CAACGCAAGCGGTCATCAAA | TAGTAGGGTTCCCTCCAGCC |

| CmGMC27-3 | CTGGGCAGCTATTCGCAAAC | CCCGACCACGATGAAGTCAA |

| CmGMC28 | GGGGCTATAGGATCCCCACA | TGGAACACAAGCCCTCCAAT |

| CmGMC29 | GGCCAAGACACCGTATCACA | TCGCGCCGTTTATATCACGA |

| CmGMC30 | ACGGGCAGATCGTGAGAAA | GGACGCAACAATAAAGGCA |

| CmGMC31 | CCATTACAAGTACGATATACCACCA | ACTCTCAAACCCTTCACGCC |

| CmGMC32 | CAGAACACCGACCCCATCTC | TCGTACTCGGTGAGGAGGTT |

| CmGMC33 | CATGCTCCTTTCAGAACAACGA | AACGATACGCCTGACGGAAA |

| CmGMC34 | AAGGCCAGCTGTATTCCGTC | CAGAGGACCCCAACGTAACC |

| CmGMC35 | ATGGAAAACGAGCGTTGCT | CGATCCTATCCCAGTCTTGAGG |

| CmGMC36 | GCCCTACTTCCTCAAGTCCG | TAGCTCAAAGGCGGGTGGTA |

| CmGMC37 | AACTACCAACCCAAAGAGACAAAAG | CGACCATGAACCCAACAGGA |

| CmGMC38 | TATGCAGCCGTATTCAACTGG | AGCGAGCGAAGTCTTTAAGGTA |

| CmGMC39 | GCAAAAACCTCCACGACCAC | GGCACTGGGAATAGGTGAGG |

| CmGMC40 | ATCACGGGACTCCAGCTCA | TCCATCGTTTTCGGAGGTGA |

| CmGMC41 | CTGTGCTTCCAGGTCTGTTTCC | GCTGTCATTCCAGGCTTGTTC |

| CmGMC42 | CTGAAACCACTTATTGAACGC | AATCCAAACTCCAACACCTT |

| CmGMC43 | GTTGGAATCAGTGCTGCCT | TCCTTGAACGTTCTGTGCG |

| CmGMC44 | GCAGATAAATTAACGCACGCTT | TAACTCGTCTGCCTTTGTGC |

| CmGMC45 | GTATGGTGTTCACGGGCTCA | AAAACGAACGCCACTCCTCT |

| CmGMC46 | TGGCCACGTGGAAAAACATT | CCCCAACCAAGGTTACCGAG |

| CmGMC47 | GCAATTCCACAGTTACGGGC | TGCCAGGTTTGTATCCTTCGT |

| CmGMC48 | CATGGTGGAAGGAGTACGATTAG | GGAAAGGGCACTGTGTGGA |

| CmGMC49 | ATGGACTGGAACTACACGGC | CTGGTCGGTCTTGTGTCCTC |

| CmGMC50 | TACCGGTATCCTTTGCCAGC | AGGGTCACCACCAGCTTCTA |

Appendix A.2. The LC50 Value of Spinetoram Against Cnaphalocrocis medinalis

The median lethal concentration (LC50) at 48 h and its 95% confidence limits for C. medinalis were determined using probit regression analysis. All statistical analyses were performed with the DPS statistical software (v18.10). The LC50 of spinetoram against third-instar larvae of C. medinalis at 48 h was 0.109 mg/L (95% CL: 0.088—0.133 mg/L). The goodness-of-fit test for the model indicated no significant deviation between the data and the model (χ2 = 1.594, df = 3, p = 0.661).

Table A2.

The LC50 value of spinetoram against Cnaphalocrocis medinalis.

Table A2.

The LC50 value of spinetoram against Cnaphalocrocis medinalis.

| Pesticide | Y = a + bx | Slope ± SE | X2 (df) | R2 | LC50 (95%CL) (mg/mL) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| spinetoram | y = 1.78 + 1.84x | 1.78 ± 0.201 | 1.594 (3) | 0.987 | 0.109 (0.88–0.133) |

Note: y represents the probability unit, and x is the logarithm (log10) of the concentration.

Appendix A.3. Location of CmGMC in Cnaphalocrocis medinalis

The chromosomal positions, start sites, stop sites, lengths, and strand orientations of all GMC gene family members were extracted from the C. medinalis genome file using the “GXF Gene Position & Info Extract” tool in TBtools.

Table A3.

Location of CmGMC in Cnaphalocrocis medinalis.

Table A3.

Location of CmGMC in Cnaphalocrocis medinalis.

| Sequence ID | Chr | Start | End | Length | ±Chain |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CmGMC1 | Chr4 | 12,031,548 | 12,037,042 | 5494 | − |

| CmGMC2 | Chr6 | 153,967 | 158,617 | 4650 | − |

| CmGMC3 | Chr6 | 158,719 | 160,568 | 1849 | − |

| CmGMC4 | Chr10 | 55,831 | 58,252 | 2421 | + |

| CmGMC5 | Chr10 | 1,592,434 | 1,601,435 | 9001 | − |

| CmGMC6 | Chr10 | 1,601,490 | 1,605,747 | 4257 | − |

| CmGMC7 | Chr10 | 8,676,573 | 8,682,633 | 6060 | + |

| CmGMC8 | Chr12 | 10,471,975 | 10,474,609 | 2634 | − |

| CmGMC9 | Chr13 | 1,419,404 | 1,422,747 | 3343 | + |

| CmGMC10 | Chr16 | 632,936 | 643,480 | 10,544 | + |

| CmGMC11 | Chr16 | 645,155 | 647,221 | 2066 | − |

| CmGMC12 | Chr16 | 2,478,010 | 2,483,491 | 5481 | − |

| CmGMC14 | Chr16 | 2,993,030 | 2,997,453 | 4423 | + |

| CmGMC15 | Chr16 | 3,081,455 | 3,084,711 | 3256 | + |

| CmGMC16 | Chr16 | 3,093,006 | 3,097,729 | 4723 | − |

| CmGMC17−1 | Chr16 | 3,141,854 | 3,145,582 | 3728 | − |

| CmGMC17−2 | Chr16 | 3,147,393 | 3,149,605 | 2212 | − |

| CmGMC17−3 | Chr16 | 3,151,400 | 3,154,375 | 2975 | − |

| CmGMC17−4 | Chr16 | 3,155,559 | 3,158,119 | 2560 | − |

| CmGMC18 | Chr16 | 3,187,948 | 3,194,577 | 6629 | − |

| CmGMC19 | Chr16 | 3,201,984 | 3,208,334 | 6350 | + |

| CmGMC20 | Chr18 | 337,806 | 346,801 | 8995 | + |

| CmGMC21 | Chr18 | 346,848 | 347,911 | 1063 | + |

| CmGMC22 | Chr18 | 347,773 | 350,514 | 2741 | − |

| CmGMC23 | Chr19 | 9,029,185 | 9,036,379 | 7194 | + |

| CmGMC24 | Chr20 | 13,117,124 | 13,120,747 | 3623 | − |

| CmGMC25 | Chr23 | 169,852 | 183,234 | 13,382 | + |

| CmGMC26 | Chr23 | 2,013,736 | 2,017,128 | 3392 | + |

| CmGMC27−1 | Chr23 | 2,021,147 | 2,024,758 | 3611 | + |

| CmGMC27−2 | Chr23 | 2,027,013 | 2,030,765 | 3752 | + |

| CmGMC27−3 | Chr23 | 2,032,287 | 2,035,200 | 2913 | + |

| CmGMC28 | Chr23 | 2,057,813 | 2,063,102 | 5289 | + |

| CmGMC29 | Chr23 | 2,109,580 | 2,121,828 | 12,248 | + |

| CmGMC30 | Chr23 | 2,218,730 | 2,221,531 | 2801 | + |

| CmGMC31 | Chr23 | 2,246,861 | 2,251,496 | 4635 | + |

| CmGMC32 | Chr23 | 2,276,183 | 2,276,614 | 431 | + |

| CmGMC33 | Chr23 | 2,276,628 | 2,277,380 | 752 | + |

| CmGMC34 | Chr23 | 2,287,382 | 2,294,626 | 7244 | + |

| CmGMC35 | Chr23 | 2,296,315 | 2,304,712 | 8397 | + |

| CmGMC36 | Chr23 | 5,982,685 | 5,992,924 | 10,239 | − |

| CmGMC37 | Chr23 | 6,339,412 | 6,349,616 | 10,204 | + |

| CmGMC38 | Chr24 | 9,639,738 | 9,643,575 | 3837 | − |

| CmGMC39 | Chr24 | 9,654,959 | 9,655,795 | 836 | − |

| CmGMC40 | Chr24 | 9,656,209 | 9,657,796 | 1587 | − |

| CmGMC41 | Chr24 | 9,709,590 | 9,720,736 | 11,146 | − |

| CmGMC42 | Chr24 | 9,743,549 | 9,747,716 | 4167 | − |

| CmGMC43 | Chr24 | 9,750,697 | 9,753,458 | 2761 | + |

| CmGMC44 | Chr26 | 7,721,527 | 7,722,002 | 475 | + |

| CmGMC45 | Chr28 | 5,613,898 | 5,633,044 | 19,146 | − |

| CmGMC46 | Chr28 | 5,679,905 | 5,681,963 | 2058 | + |

| CmGMC47 | Chr28 | 7,652,152 | 7,679,704 | 27,552 | − |

| CmGMC48 | ctg1590 | 27,242 | 32,075 | 4833 | + |

| CmGMC49 | ctg7278 | 862 | 2515 | 1653 | + |

| CmGMC50 | ctg7917 | 15 | 4822 | 4807 | + |

References

- Yuan, B.; Doxsey, W.; Tok, O.; Kwon, Y.Y.; Liang, Y.S.; Inouye, K.E.; Hotamisligil, G.S.; Hui, S. An organism-level quantitative flux model of metabolism in mice. Cell Metab. 2025, 37, 1012–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clerch, L.B.; Massaro, D. Oxidation-resuction-sensitive binding of lung protrin to rat catalase messenger-RNA. J. Biol. Chem. 1992, 267, 2853–2855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavener, D.R. GMC oxidoreductases: A newly defned family of homologous proteins with diverse catalytic activities. J. Mol. Biol. 1992, 223, 811–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.Z.; Liu, L.Q.; Chen, D.J.; Wang, Y.Z.; Zhang, J.L.; Shao, L. Co-expression of the recombined alcohol dehydrogenase and glucose dehydrogenase and cross-linked enzyme aggregates stabilization. Bioresour. Technol. 2017, 224, 531–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sützl, L.; Foley, G.; Gillam, E.M.J.; Bodén, M.; Haltrich, D. The GMC superfamily of oxidoreductases revisited: Analysis and evolution of fungal GMC oxidoreductases. Biotechnol. Biofuels 2019, 12, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nouche, C.B.; Picard, L.; Cochet, C.; Paris, C.; Oger, P.; Turpault, M.P.; Uroz, S. Acidification-based mineral weathering mechanism involves a glucose/methanol/choline oxidoreductase in Caballeronia mineralivorans PML1(12). Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2024, 90, e0122124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiess, M.; Hecht, H.J.; Kalisz, H.M. Glucose oxidase from Penicillium amagasakiense—Primary structure and comparison with other glucose-methanol-choline (GMC) oxidoreductases. Eur. J. Biochem. 1998, 252, 90–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strecker, H.J.; Korkes, S. Glucose dehydrogenase. J. Biol. Chem. 1952, 192, 769–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vital, W.; Rezende, G.L.; Abreu, L.; Moraes, J.; Lemos, F.J.A.; Vaz, I.D.S., Jr.; Logullo, C. Germ band retraction as a landmark in glucose metabolism during Aedes aegypti embryogenesis. BMC Dev. Biol. 2010, 10, 10–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, J.; Wu, Y.; You, L.L.; Xu, B.; Ge, L.Q.; Yang, G.Q.; Wu, J.C. Jinggangmycin-suppressed reproduction in the small brown planthopper (SBPH), Laodelphax striatellus (Fallen), is mediated by glucose dehydrogenase (GDH). Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 2017, 139, 73–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iida, K.; Cavener, D.R. Glucose dehydrogenase is required for normal sperm storage and utilization in female Drosophila melanogaster. J. Exp. Biol. 2004, 207, 675–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohanty, S.S.; Singh, K.V.; Bansal, S.K. Changes in glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase activity in Indian desert malaria vector Anopheles stephensi during aging. Acta Trop. 2012, 123, 132–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Legan, S.K.; Rebrin, I.; Mockett, R.J.; Radyuk, S.N.; Klichko, V.I.; Sohal, R.S.; Orr, W.C. Overexpression of glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase extends the life span of Drosophila melanogaster. J. Biol. Chem. 2008, 283, 32492–32499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox Foster, D.L.; Stehr, J.E. Induction and localization of FAD-glucose dehydrogenase (GLD) during encapsulation of abiotic implants in Manduca sexta larvae. J. Insect Physiol. 1994, 40, 235–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovallo, N.; Cox-Foster, D.L. Alteration in FAD–glucose dehydrogenase activity and hemocyte behavior contribute to initial disruption of Manduca sexta immune response to Cotesia congregata parasitoids. J. Insect Physiol. 1999, 45, 1037–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takenaka, T.; Ito, H.; Yatsunami, K.; Echigo, T. Changes of glucose-oxidase activity and amount of gluconic acid formation in the Hypopharyngeal glands during the lifespan of honey bee workers (Apis mellifera L.). Agric. Biol. Chem. 1990, 54, 2133–2134. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Sherif, A.A.; Mazeed, A.M.; Ewis, M.; Nafea, E.; Hagag, E.E.; Kamel, A. Activity of salivary glands in secreting honey-elaborating enzymes in two subspecies of honeybee (Apis mellifera L.). Physiol. Entomol. 2017, 42, 397–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Q.B.; Hu, Y.H.; Kang, L.; Wang, C.Z. For: Archives of insect biochemistry and physiology characterization of glucose-induced glucose oxidase gene and protein expression in Helicoverpa armigera larvae. Arch. Insect Biochem. Physiol. 2012, 79, 104–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, A.C.; Lin, P.; Peiffer, M.; Felton, G. Caterpillar salivary glucose oxidase decreases green leaf volatile emission and increases terpene emission from maize. J. Chem. Ecol. 2023, 49, 518–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarfare, S.; Ahmad, S.T.; Joyce, M.V.; Boggess, B.; O’Tousa, J.E. The Drosophila ninaG oxidoreductase acts in visual pigment chromophore production. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 11895–11901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, S.T.; Joyce, M.V.; Boggess, B.; O’Tousa, J.E. The role of Drosophila ninaG oxidoreductase in visual pigment chromophore biogenesis. J. Biol. Chem. 2006, 281, 9205–9209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takeuchi, H.; Rigden, D.J.; Ebrahimi, B.; Turner, P.C.; Rees, H.H. Regulation of ecdysteroid signalling during Drosophila development: Identification, characterization and modelling of ecdysone oxidase, an enzyme involved in control of ligand concentration. Biochem. J. 2005, 389, 637–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weirich, G.F.; Thompson, M.J.; Svoboda, J.A. Ecdysone oxidase and 3-oxoecdysteroid reductases in Manduca sexta midgut: Kinetic parameters. Arch. Insect Biochem. Physiol. 1989, 12, 201–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, L.N.; Zhu, L.H.; Cheng, Z.Q.; Bai, Y.; Li, P.X.; Yang, H.C.; Tang, S.W.; Crickmore, N.; Zhou, X.G.; Zhang, Y.J. Characterization of an ecdysone oxidase from Plutella xylostella (L.) and its role in Bt Cry1Ac resistance. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2025, 73, 1193–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojha, S.; Tapadia, M.G. Transcriptome profiling identifies multistep regulation through E93, forkhead and ecdysone oxidase in survival of malpighian tubules during metamorphosis in Drosophila. Int. Dev. Biol. 2020, 64, 331–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavigliasso, F.; Savitsky, M.; Koval, A.; Erkosar, B.; Savary, L.; Gallart-Ayala, H.; Ivanisevic, J.; Katanaev, V.L.; Kawecki, T.J. Cis-regulatory polymorphism at fiz ecdysone oxidase contributes to polygenic evolutionary response to malnutrition in Drosophila. PLoS Genet. 2024, 20, e1011204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.F.; Zhang, Z.; Sun, W. Ecdysone oxidase and 3-dehydroecdysone-3β-reductase contribute to the synthesis of ecdysone during early embryonic development of the silkworm. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2018, 14, 1472–1482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iida, K.; Cox-Foster, D.; Yang, X.L.; Ko, W.Y.; Cavener, D.R. Expansion and evolution of insect GMC oxidoreductases. BMC Evol. Biol. 2007, 7, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; Shen, Y.H.; Yang, W.J.; Cao, Y.F.; Xiang, Z.X.; Zhang, Z. Expansion of the silkworm GMC oxidoreductase genes is associated with immunity. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2012, 42, 935–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, Y.H.; Silven, J.J.M.; Wybouw, N.; Fandino, R.A.; Dekker, H.L.; Vogel, H.; Wu, Y.-L.; De Koster, C.; Große-Wilde, E.; Haring, M.A.; et al. A salivary GMC oxidoreductase of Manduca sexta re-arranges the green leaf volatile profile of its host plant. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 3666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Padmavathi, C.H.; Katti, G.; Padmakumari, A.P.; Voleti, S.R.; Subba Rao, L.V. The effect of leaffolder Cnaphalocrocis medinalis (Guenee) [Lepidoptera: Pyralidae] injury on the plant physiology and yield loss in rice. J. Appl. Entomol. 2013, 137, 249–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.S.; Ren, X.B.; Su, J.Y. Insecticide susceptibility of Cnaphalocrocis medinalia (Lepidoptera: Pyralidae) in Chian. J. Econ. Entomol. 2011, 104, 653–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Liu, S.T.; Ling, Y.; Wang, L.; Ni, H.; Guo, D.; Dong, B.B.; Huang, Q.; Long, L.P.; Zhang, S.; et al. Insecticide resistance monitoring of Cnaphalocrocis medinalis (Lepidoptera: Pyralidae) and its mechanism to chlorantraniliprole. Pest Manag. Sci. 2023, 79, 3290–3299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.H.; Lee, S.Y.; Choi, J.Y.; Lee, S.H.; Fang, Y.; Ha, K.B.; Park, D.H.; Park, M.G.; Woo, R.M.; Kim, W.J.; et al. Laboratory evaluation of transgenic Bt rice resistance against rice leaf roller, Cnaphalocrocis medinalis. J. Asia-Pac. Entomol. 2017, 20, 221–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Li, L.K.; Liu, B.; Wang, L.; Parajulee, M.N.; Megha, N.; Chen, F.J. Effects of seed mixture sowing with transgenic Bt rice and its parental line on the population dynamics of target stemborers and leafrollers, and non-target planthoppers. Insect Sci. 2019, 26, 777–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.X.; Li, S.G.; Rao, X.J.; Liu, S. Molecular characterization of a NADPH-cytochrome P450 reductase gene from the rice leaffolder, Cnaphalocrocis medinalis (Lepidoptera: Pyralidae). Appl. Entomol. Zool. 2018, 53, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Li, C.; Yang, Z.F. Identification and Expression of Two Novel Cytochrome P450 Genes, CYP6CV1 and CYP9A38, in Cnaphalocrocis medinalis (Lepidoptera: Pyralidae). J. Insect Sci. 2015, 15, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, S.; Rao, X.J.; Li, M.Y.; Feng, M.F.; He, M.Z.; Li, S.G. Glutathione S-transferase genes in the rice leaffolder, Cnaphalocrocis medinalis (Lepidoptera: Pyralidae): Identification and expression profiles. Arch. Insect Biochem. Physiol. 2015, 90, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Subhagan, S.R.; Pathrose, B.; Chellappan, M.; Smitha, M.S.; Ranjith, M.T.; Nair, S.; Dhalin, D. Multiple detoxification enzymes mediate resistance to anticholinesterase insecticides in Cnaphalocrocis medinalis (Lepidoptera: Crambidae). Crop Prot. 2015, 195, 107261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.X.; Wang, W.L.; Li, M.Y.; Li, S.G.; Liu, S. Identification of putative carboxylesterase and aldehyde oxidase genes from the antennae of the rice leaffolder, Cnaphalocrocis medinalis (Lepidoptera: Pyralidae). J. Asia-Pac. Entomol. 2017, 20, 907–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.Z.; Wen, D.F.; Wang, W.L.; Geng, L.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, J.P. Identification of genes putatively involved in chitin metabolism and insecticide detoxification in the rice leaf folder (Cnaphalocrocis medinalis) larvae through transcriptomic analysis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2015, 16, 21873–21896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salgado, V.L.; Sparks, T.C.; Gilbert, L.I.; Gill, S.S. The spinosyns: Chemistry, biochemistry, mode of action, and resistance. In Insect Control: Biological and Synthetic Agents; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2010; pp. 207–243. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, J.G. Unraveling the mystery of spinosad resistance in insects. J. Pestic. Sci. 2008, 33, 221–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, P.; Lin, W.; Lin, Q.; Li, Z.; Hang, F.; Zhang, Z.; Lu, Y. Baseline susceptibility of Plutella xylostella (Lepidoptera: Plutellidae) to the novel insecticide spinetoram in China. J. Econ. Entomol. 2015, 108, 736–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lira, E.C.; Bolzan, A.; Nascimento, A.R.; Amaral, F.S.; Kanno, R.H.; Kaiser, I.S.; Omoto, C. resistance of Spodoptera frugiperda (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) to spinetoram: Inheritance and cross—Resistance to spinosad. Pest Manag. Sci. 2020, 76, 2674–2680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.K.; Ren, X.B.; Wang, Y.C.; Su, J. resistance in Cnaphalocrocis medinalis (Lepidoptera: Pyralidae) to new chemistry insecticides. J. Econ. Entomol. 2014, 107, 815–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quan, P.Q.; Li, M.Z.; Wang, G.R.; Gu, L.L.; Liu, X.D. Comparative transcriptome analysis of the rice leaf folder (Cnaphalocrocis medinalis) to heat acclimation. BMC Genom. 2020, 21, 450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.X.; Xu, H.X.; He, K.; Shi, Z.M.; Chen, X.; Ye, X.H.; Mei, Y.; Yang, Y.J.; Li, M.Z.; Gao, L.B.; et al. A chromosome-level genome assembly of rice leaffolder, Cnaphalocrocis medinalis. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 2021, 21, 561–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, J.R.; Yao, X.J.; Ni, Z.H.; Zhao, H.F.; Yang, Y.J.; Xu, H.X.; Lu, Z.X.; Zhu, P.Y. Identification of salivary proteins in the rice leaf folder Cnaphalocrocis medinalis by transcriptome and LC-MS/MS analyses. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2024, 174, 104–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, H.T.; Lu, J.Q.; Ji, K.; Wang, C.C.; Yao, Z.C.; Liu, F.; Li, Y. Comparative transcriptomic assessment of chemosensory genes in adult and larval olfactory organs of Cnaphalocrocis medinalis. Genes 2023, 14, 2165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, H.X.; Zhao, X.X.; Yang, Y.J.; Chen, X.; Mei, Y.; He, K.; Xu, L.; Ye, X.H.; Liu, Y.; Li, F.; et al. Chromosome-level genome assembly of an agricultural pest, the rice leaffolder Cnaphalocrocis exigua (Crambidae, Lepidoptera). Mol. Ecol. Resour. 2022, 22, 307–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Wu, Y.; Li, J.; Wang, X.; Zeng, Z.; Xu, J.; Liu, Y.; Feng, J.; Chen, H.; He, Y.; et al. TBtools-II: A “one for all, all for one” bioinformatics platform for biological big-data mining. Mol. Plant 2023, 16, 1733–1742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, S.; Stecher, G.; Suleski, M.; Sanderford, M.; Sharma, S.; Tamura, K. MEGA12: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis Version 12 for adaptive and green computing. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2024, 41, msae263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, S.Q.; Gascuel, O. An Improved general amino acid replacement matrix. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2008, 25, 1307–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nei, M.; Kumar, S. Molecular Evolution and Phylogenetics; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2000; pp. 147–164. [Google Scholar]

- Felsenstein, J. Confidence limits on phylogenies:An approach using the bootstrap. Evolution 1985, 39, 783–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saitou, N.; Nei, M. The neighbor-joining method: A new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol. Biol. Evol. 1987, 4, 406–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, A.X.; Qian, Q.; Liu, X.D.A. Method for rearing the rice leaf folder (Cnaphalocrocis medinalis) using wheat seedlings. Chin. J. Appl. Entomol. 2015, 52, 883–889. [Google Scholar]

- Livak, K.J.; Schmittgen, T.D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT method. Methods 2001, 25, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, Q.Y.; Zhang, C.X. Data Processing System (DPS) software with experimental design, statistical analysis and data mining developed for use in entomological research. Insect Sci. 2013, 20, 254–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orengo, C.A.; Thornton, J.M. Protein families and their evolution—A structural perspective. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2005, 74, 867–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, M.E.; Agresti, A. HMG proteins: Dynamic players in gene regulation and differentiation. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 2005, 15, 496–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asmamaw, M.D.; He, A.; Zhang, L.R.; Liu, H.M.; Gao, Y. Histone deacetylase complexes: Structure, regulation and function. Biochim. Biophys. Acta BBA-Rev. Cancer 2024, 1879, 189150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Yang, X.Y.; Zhang, C.R.; Zhang, C.; Zheng, H.X.; Zheng, X.H. Identification and expression analysis of heat shock protein superfamily genes in Callosobruchus chinensis. Sci. Agric. Sin. 2023, 56, 3814–3828. [Google Scholar]

- Hao, X.; Tan, R.; Chen, J.; Li, Y.; Cao, J.X.; Diao, J.; Deng, Z.; Zhang, P.; Ma, L. Analysis of structures and expression patterns of the flavin-containing monooxygenase family genes in Bursaphelenchus xylophilus. J. Zhejiang Univ. Agric. Life Sci. 2023, 49, 191–199. [Google Scholar]

- Thoris, K.; Marrero, M.C.; Fiers, M.; Lai, X.L.; Zahn, I.E. Uncoupling FRUITFULL’s functions through modification of a protein motif identified by co-ortholog analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2024, 52, 13290–13304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parthasarathy, S.; Murthy, M.R.N. Protein thermal stability: Insights from atomic displacement parameters (B values). Protein Eng. 2000, 13, 9–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Z.; Su, C.; Guo, X.; Zhao, Y.; Nie, R.; He, B.; Hao, J. Genome-wide identification, gene duplication, and expression pattern of NPC2 Gene Family in Parnassius glacialis. Genes 2025, 16, 249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robertson, H.M.; Warr, C.G.; Carlson, J.R. Molecular evolution of the insect chemoreceptor gene superfamily in Drosophila melanogaster. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 14537–14542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Liu, Q.; Lu, J.J.; Wu, L.Y.; Cheng, Z.T.; Qiao, G.X.; Huang, X.L. Genomic and transcriptomic analyses of a social hemipteran provide new insights into insect sociality. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 2024, 24, e14019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, T.; Hua, G.S.; Chen, C.J.; Shen, G.W.; Li, Z.Q.; Hua, X.T.; Lin, P.; Zhao, P.; Xia, Q.Y. Metabolic benefits conferred by duplication of the facilitated trehalose transporter in Lepidoptera. Insect Sci. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKenna, D.D.; Scully, E.D.; Pauchet, Y.; Hoover, K.; Kirsch, R.; Geib, S.M.; Mitchell, R.F.; Waterhouse, R.M.; Ahn, S.J.; Arsala, D.; et al. Genome of the Asian longhorned beetle (Anoplophora glabripennis), a globally significant invasive species, reveals key functional and evolutionary innovations at the beetle–plant interface. Genome Biol. 2016, 17, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gracheva, E.O.; Ingolia, N.T.; Kelly, Y.M.; Cordero-Morales, J.F.; Hollopeter, G.; Chesler, A.T.; Sánchez, E.E.; Perez, J.C.; Weissman, J.S.; Julius, D. Molecular basis of infrared detection by snakes. Nature 2010, 464, 1006–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quan, P.Q.; Li, J.R.; Liu, X.D. Glucose dehydrogenases-mediated acclimation of an important rice pest to global warming. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 10146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uhlén, M.; Fagerberg, L.; Hallström, B.M.; Lindskog, C.; Oksvold, P.; Mardinoglu, A.; Sivertsson, Å.; Kampf, C.; Sjöstedt, E.; Asplund, A.; et al. Tissue-based map of the human proteome. Science 2015, 347, 1260419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feyereisen, R. Insect P450 enzymes. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 1999, 44, 507–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zachepilo, T.G.; Pribyshina, A.K. Heat shock proteins in normal insect physiology. Integr. Physiol. 2022, 3, 221–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daborn, P.J.; Yen, J.L.; Bogwitz, M.R.; Goff, G.L.; Feil, E.; Jeffers, S.; Tijet, N.; Perry, T.; Heckel, D.; Batterham, P.; et al. A single P450 allele associated with insecticide resistance in Drosophila. Science 2002, 297, 2253–2256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, K.; Wang, Y.; Chen, X.; Zhang, Z.C.; Li, Y.; Li, W.R.; Zhou, Q. Characterization and functional analysis of a carboxylesterase gene associated with chlorpyrifos resistance in Nilaparvata lugens (Stål). Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part C Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2017, 203, 12–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.Z.; Kong, F.C.; Cui, R.K.; Zeng, X.N. Gene expression of detoxification enzymes in insecticide-resistant and insecticide-susceptible Bemisia tabaci strains after diafenthiuron exposure. J. Agric. Sci. 2016, 154, 742–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Després, L.; David, J.P.; Gallet, C. The evolutionary ecology of insect resistance to plant chemicals. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2007, 22, 298–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, N.N.; Li, M.; Gong, Y.H.; Liu, F.; Li, T. Cytochrome P450s–Their expression, regulation, and role in insecticide resistance. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 2015, 120, 77–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Kong, X.D.; Zhu-Salzman, K.; Qin, Q.M.; Cai, Q.N. The key glutathione S-transferase family genes involved in the detoxification of rice gramine in brown planthopper Nilaparvata lugens. Insects 2021, 12, 1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montella, I.R.; Schama, R.; Valle, D. The classification of esterases: An important gene family involved in insecticide resistance—A review. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz 2012, 107, 437–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiao, Q.X.; Feng, H.T.; Jiao, L.; Zaheer, U.; Zheng, C.Q.; Zhou, L.; Lin, G.F.; Xiang, X.J.; Liao, H.; Li, S.Y.; et al. Bacteria derived from diamondback moth, Plutella xylostella (L.) (Lepidoptera: Plutellidae), gut regurgitant negatively regulate glucose oxidase-mediated anti-defense against host plant. Insects 2024, 15, 1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, Z.J.; Zhu, L.H.; Cheng, Z.Q.; Dong, L.N.; Guo, L.; Bai, Y.; Wu, Q.J.; Wang, S.L.; Yang, X.; Xie, W.; et al. A midgut transcriptional regulatory loop favors an insect host to withstand a bacterial pathogen. Innovation 2024, 5, 100675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).