The present study represents the first attempts to systematically examine human–insect relationships in Romania and contributes to the limited body of literature on this topic internationally. The current study used a comprehensive theoretical model by integrating the TPB and VBN variables, together with additional constructs: knowledge about insects, naturalist identity, nature connectedness, perceived barriers, and perceived opportunities to evaluate the factors shaping individuals’ insect-friendly behaviors.

4.1. Knowledge, Attitudes, and Perceived Barriers in Insect Conservation

Findings show a strong link between knowledge and positive attitudes toward insects, consistent with prior research [

42,

79]. Accurate information appears crucial for shaping positive orientations, especially given the persistence of misconceptions that fuel fear and aversion. Demographic and affective factors also mattered: older participants and men reported more positive attitudes, while emotional connection with nature, naturalist identity, and frequent exposure to nature significantly enhanced conservation concern [

82,

83,

84].

The present findings diverge from the traditional knowledge–action gap described in the environmental psychology literature [

78,

109], which assumes that individuals possess the necessary knowledge but fail to act upon it. In contrast, the results of this study indicate a more fundamental knowledge deficit: respondents did not demonstrate a clear understanding of what specific actions are required to protect insects. While general awareness of the ecological importance of insects was moderate to high, knowledge of concrete, insect-friendly conservation practices was markedly low. Misconceptions, such as the belief that beekeeping can reverse insect decline or that only two bee species exist, were widespread, reflecting limited exposure to accurate information.

This pattern suggests that, in the Romanian context, insufficient knowledge and limited access to reliable information represent one of several barriers to the adoption of pro-conservation behaviors. While motivational and attitudinal factors play an important role, the lack of clear understanding regarding specific conservation actions appears to further hinder behavioral engagement. In contrast to countries with a long-standing tradition of environmental education and citizen science initiatives [

78,

110], Romania’s public involvement in biodiversity conservation remains in a formative stage. As a result, the general population may not yet have developed an adequate informational and experiential foundation to consistently translate positive attitudes into responsible actions toward insect protection.

These findings are also influenced by the age profile of the sample, which can be identified as a limitation, predominantly composed of young adults (18–24 years), a generation with limited formal exposure to entomological topics, typically restricted to two biology lessons in the sixth-grade curriculum. Prior research has shown that childhood experiences in nature are crucial for developing ecological awareness and empathy [

30]. Therefore, the relatively low knowledge levels observed among younger respondents may reflect both educational limitations and the broader phenomenon of “extinction of experience”, which describes the declining direct interaction with nature among modern youth populations [

33,

35]. Also, another identified limitation resides in the lack of information about the curricular content and the expertise (in terms of ecological education) of the teaching staff that delivered entomological topics to some of the respondents.

Perceived barriers further reinforced this lack of knowledge, time, and financial resources which were the most frequently reported obstacles, with informational barriers proving as limiting as logistical ones. Importantly, perceived barriers correlated negatively with self-reported conservation behaviors, consistent with prior findings that constraints, real or perceived, can suppress environmental action [

87,

94,

95,

111]. Addressing these barriers through accessible, evidence-based communication and practical guidance is thus critical for supporting broader engagement in insect conservation.

4.2. Integrating Theoretical Frameworks to Explain Insect Conservation Behavior

Behind such complex behaviors that comprise the protection and conservation of insects there is an entire hierarchical motivational architecture, with factors related to different registers of psychological functioning and not only, factors that have variable predictive values. To this end, the present study verified the predictive value of three explanatory models to identify the most effective vectors of educational influence—the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB), the Value–Belief–Norm (VBN) and an integrated framework that synthesizes both while adding additional variables: the level of accumulated knowledge, the nature connectedness, the naturalistic identity or the direct contextual variables: barriers and opportunities. The perspectives that the two basic models offer are complementary, The VBN framework captures the deep-seated moral and value-based foundations of ecological engagement; the TPB adds a rational–cognitive layer. While both the VBN and TPB models exhibited significant pathways when analyzed separately, the TPB predictors, attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control, lost statistical significance in the combined model. This contrasts with other environmental behaviors, such as water conservation behavior [

56], recycling [

57,

58], energy conservation [

61,

62,

86] or sustainable mobility choices [

112] where well-established social expectations and infrastructures reinforce the predictive power of subjective norms and perceived control.

However, when attitudes were modeled to influence behavior both directly and indirectly through intention, they became positive and statistically significant, improving the overall explanatory power of the model. This result aligns with theoretical extensions of the TPB, which suggest that under certain conditions, such as when behaviors are emotionally salient, familiar, or personally relevant, attitudes can directly predict behavior, bypassing the mediating role of intention [

48,

113]. In this case, attitudes toward insects likely function more as affective evaluations than as purely cognitive judgments, shaped by emotional reactions such as fear, empathy, or fascination. These emotions can either motivate protective behaviors or lead to avoidance and indifference [

28,

31]. Understanding this affective basis is crucial for designing educational and communication strategies that reshape public perceptions and foster positive engagement with insects.

In the collective imagination, insects, unlike other living species (e.g., plants), are often attributed a series of negative qualities [

23,

27,

28,

31], which creates a wide range of emotions and attitudes that cannot be captured by cognitive-rational mechanisms. It is therefore understandable that for protective intentions and behaviors towards insects, the VBN model which focuses on determinations related to emotional, attitudinal, and value registers has a greater predictive value. Making a comparison between the predictive value of moral norms, it is observed that for insects and their protection, internalized moral norms (VBN) (biospheric values, ecological worldview, moral responsibility and personal moral norms) are stronger than subjective norms (social pressure or expectations of others) analyzed by TPB.

In the Romanian context, this pattern may be further reinforced by the limited institutionalization of pro-environmental social norms. Currently, there is no strong social expectation or cultural framework that encourages individuals to take action for insect protection. Similar findings have been observed across cultural contexts, where the influence of social norms on pro-environmental behavior is highly dependent on cultural orientation and the degree of social norm internalization [

114]. As social norms often serve as key sources of information and behavioral guidance, defining what is appropriate or expected within a community [

115], their absence weakens the normative pressure to act.

In contrast, personal or moral norms, as conceptualized in the VBN framework, are activated when individuals: (a) become aware that their actions have consequences for the well-being of others (awareness of consequences) and (b) accept personal responsibility for those consequences (ascription of responsibility) [

16,

53]. When both conditions are met, moral norms become strong motivators of behavior, even in the absence of strong social expectations [

16]. This distinction may explain why, in domains such as recycling or plastic reduction, where societal expectations and visibility of environmental problems are high, individuals experience both social pressure and moral obligation to act [

81,

112]. Conversely, the decline of insects is a less visible and less publicly discussed issue, leading to weaker subjective norms and reliance primarily on internalized moral motivations.

Empirical studies on insect conservation psychology confirm that people’s engagement in insect-friendly actions depend not only on ecological knowledge but also on the development of a culture of personal and collective responsibility [

116]. In Romania, public perceptions of environmental issues remain fragmented, with awareness often unaccompanied by consistent behavioral norms or civic engagement [

117]. Moreover, insects are frequently perceived primarily through their utility to humans, rather than as intrinsic components of ecosystems. Despite their ecological importance, knowledge and public awareness about insect decline remain limited, and there is not yet a widespread cultural or normative framework that encourages insect-friendly behaviors [

116,

118]. Consequently, moral norms, rather than social expectations, played the dominant role in predicting responsible behavior in this study.

Beyond the core VBN–TPB integration, the inclusion of additional psychological and contextual variables, knowledge, connection with nature, naturalist identity, barriers, and opportunities, provided deeper insight into the mechanisms that shape responsible behavior toward insects. These results are in line with previous works [

75,

76,

78]. Knowledge emerged as a key determinant, positively influencing both attitudes and perceived behavioral control, as well as directly predicting behavior [

79,

80,

81]. This highlights the importance of educational and informational interventions, as awareness remains a prerequisite for activating moral and behavioral engagement. Feeling connected to nature and identifying with naturalist roles were associated with stronger biospheric values and more positive attitudes, a pattern similar to reports that tie emotion and identity to pro-environmental action [

32,

84,

85,

92,

93]. Situational factors such as barriers and opportunities also shaped engagement, barriers reduced behavioral control and action, while opportunities facilitated behavioral translation. Taken together, the final model highlights the dominant role of the VBN pathway, where connection with nature, biospheric values, worldviews, and moral norms jointly explain intention and behavior. At the same time, attitudinal and contextual influences (knowledge, opportunities, barriers) add complementary predictive power, ensuring that the model integrates both deep-seated normative motivations and situational enablers of pro-environmental action.

4.3. Practical and Educational Implications

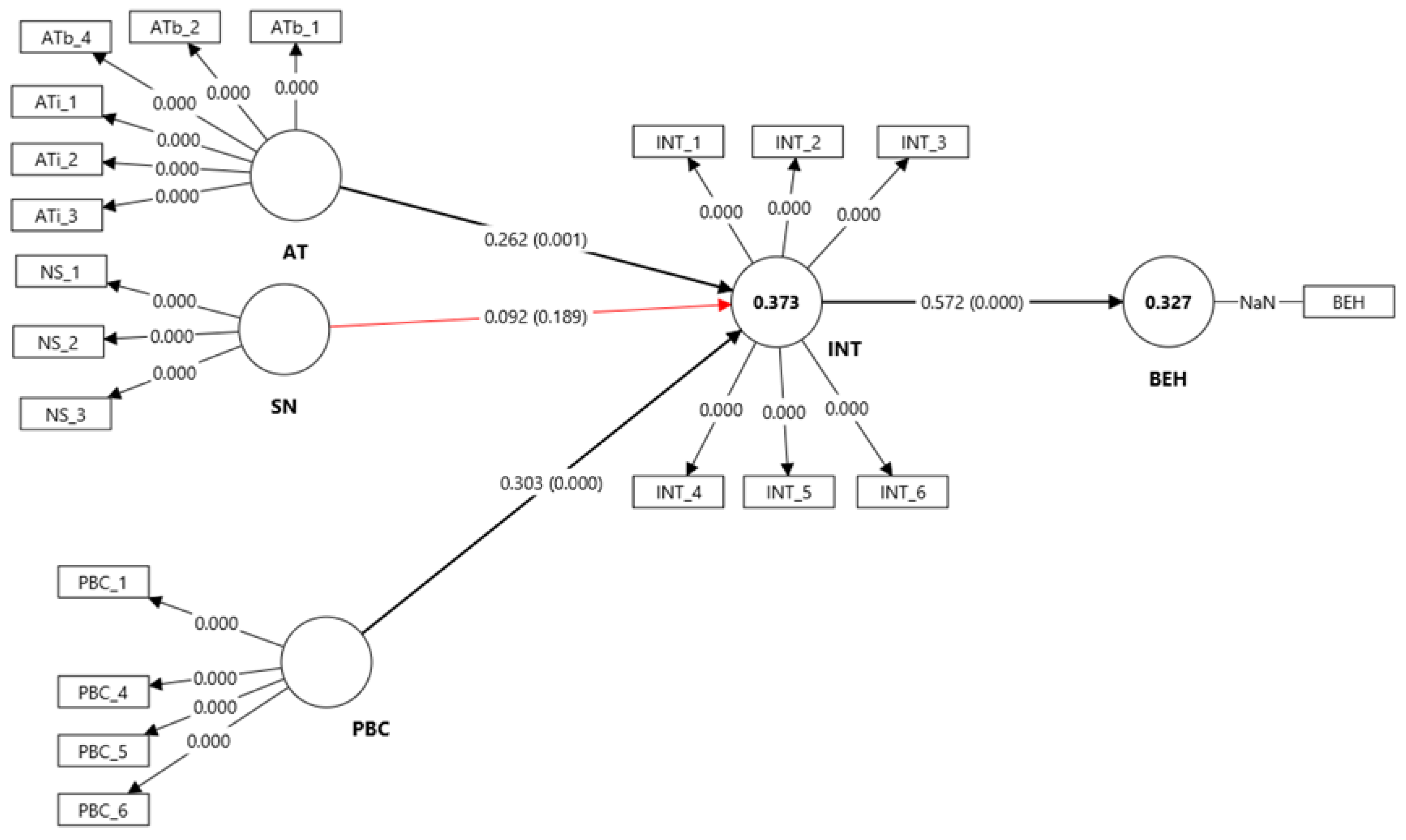

Translated into educational practice, the results illustrated in

Figure 7 identify not only the determinants of protective behaviors toward insects but also a hierarchy of educational interventions capable of strengthening them. The integrated TPB–VBN model suggests that effective conservation education should begin with affective and motivational activation before introducing cognitive or informational components. Moral and ethical engagement, empathy, and emotional connection with nature should precede knowledge acquisition in order to counteract the negative emotional perceptions often associated with insects.

4.3.1. Early Childhood Interventions and Role Modeling

Nature connectedness and naturalist identity are often established during early childhood through direct and sustained interaction with natural environments. Experiences in memorable outdoor settings help children develop emotional bonds, positive values, and a lifelong commitment to the environment [

32,

119]. Unstructured play in natural spaces enhances creativity, problem-solving, resilience, and emotional well-being [

120], while access to green areas encourages exploration and curiosity [

119]. Adult role models, parents, grandparents, and teachers, reinforce these experiences by modeling empathy, respect, and care for living organisms. Such formative encounters lay the foundation for enduring pro-environmental values and behaviors that persist into adulthood [

32].

4.3.2. Knowledge Integration and Cognitive Reinforcement

After affective and moral dimensions have been activated, educational programs should focus on reinforcing ecological literacy. Lessons on the ecological roles of insect pollination, decomposition, and ecosystem balance, can be integrated across disciplines such as biology, geography, and civic education. Inquiry-based and experiential methods, including mini-research projects or building insect habitats, help translate curiosity into understanding and sustained engagement.

4.3.3. Community Engagement and Opportunity Creation

At the community level, initiatives such as pollinator-friendly gardens, urban biodiversity zones, and intergenerational conservation projects provide accessible opportunities for participation and reduce perceived barriers to action. Collaborative programs involving schools, NGOs, and local authorities can help institutionalize pro-environmental norms and increase collective efficacy. Highlighting positive social models: teachers, gardeners, or citizens actively engaged in insect protection, can strengthen emerging social expectations in relation to an integrative ecological mindset.

4.3.4. Communication and Cultural Change

Promoting behavioral change toward insect conservation requires not only the dissemination of ecological knowledge but also the transformation of underlying cultural narratives and emotional associations. Insects have traditionally occupied ambivalent positions within human culture, symbolizing both fascination and fear. Across most cultures, positive and negative representations of insects coexist, often associated with specific species and the nature of human contact with them. Insects that play visible ecological or symbolic roles, such as bees or ladybugs, are typically linked to values like diligence, luck, or renewal, whereas those encountered in domestic or urban settings, such as flies, mosquitoes, or cockroaches, tend to evoke discomfort, disgust, or fear. These contrasting perceptions are reinforced through everyday experience, popular media, mythology, and folklore, shaping the ambivalent emotional landscape that characterizes human–insect relationships.

In the Romanian cultural context, ‘

useful insects’ such as bees and ants are often associated with virtues like diligence, solidarity, and natural order, whereas species perceived as harmful, mosquitoes, flies, or cockroaches, evoke feelings of repulsion and fear, being symbolically tied to dirt or disease [

121]. The persistence of these representations, transmitted across generations through proverbs, folktales, and traditional practices, contributes to ambivalent attitudes toward insects that combine appreciation with avoidance. Communication strategies should therefore aim to reframe these cultural meanings by emphasizing the ecological indispensability, aesthetic diversity, and cultural significance of insects.

Integrating scientific information with emotionally engaging storytelling can foster empathy and reshape collective perceptions. Art, media, and community-based initiatives, such as educational exhibitions, urban biodiversity festivals, or artistic projects celebrating pollinators, can make insects visible within public spaces and collective imagination. In Romania, where ecological education and insect conservation are still emerging fields, communication efforts may benefit from connecting ecological messages with culturally familiar and positive symbols, thereby fostering acceptance and identification.

Cultural perceptions also play an important role in shaping attitudes toward entomophagy. While the present study did not address edible insect consumption, it is important to acknowledge that cultural representations, whether of insects as food, symbols, or ecological partners, can influence public openness to sustainability-related behaviors. Positive cultural reframing could thus contribute not only to conservation-oriented attitudes but also to the gradual normalization of alternative, ecologically responsible practices, including edible insect acceptance, in contexts where such practices are novel.

4.3.5. Limitation of the Study

A key limitation of this study concerns the sociodemographic composition of the sample, which was not evenly distributed across gender and residential categories. Women were substantially overrepresented (73.7%), while men accounted for 26.3% of participants. Although the difference in attitudes toward insects between women (M = 4.60, SD = 1.40) and men (M = 4.99, SD = 1.25) was statistically significant (t(337) = −2.44, p = 0.016), the effect size was small (d = 0.29), indicating that both groups hold generally positive views of insects. However, because women, who expressed slightly less positive attitudes, were numerically dominant, the overall mean (M = 4.70, SD = 1.37) may slightly underestimate the general level of positivity that would be expected in a more gender-balanced sample.

The use of a convenience sampling method further contributed to a predominance of participants residing in urban areas. Prior research has shown that urban residents often exhibit less favorable attitudes toward insects than rural inhabitants [

122], potentially influencing the overall averages. In this study, however, no significant differences were observed between respondents from urban and rural settings. This lack of difference may be explained by the age structure of the sample, largely composed of young adults aged 18–24, for whom direct contact with nature has been increasingly replaced by digital interaction, a process described as the “extinction of experience.” In Romania, where internet access and digital infrastructure are highly developed nationwide, young people from both urban and rural areas are equally exposed to technology, which may mitigate traditional disparities in attitudes toward nature and insects.

While these sociodemographic imbalances limit the generalizability of the results to the entire Romanian population, they nonetheless provide a valuable foundation for understanding behavioral determinants of insect conservation. Moreover, they highlight key demographic segments that can serve as target groups for awareness campaigns and educational initiatives tailored to the Romanian socio-cultural context.