Plant Volatile Organic Compounds Attractive to Monolepta signata (Olivier)

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Insects

2.2. Chemicals

2.3. Preparation of Plant Volatile Mixtures

2.4. Determination of EAG Responses of M. signata to Mixtures of Plant Volatiles

2.5. Bioassay of Behavioral Response of M. signata to Mixtures of Plant Volatiles

2.6. Field Attraction

2.7. Data Analyses

3. Results

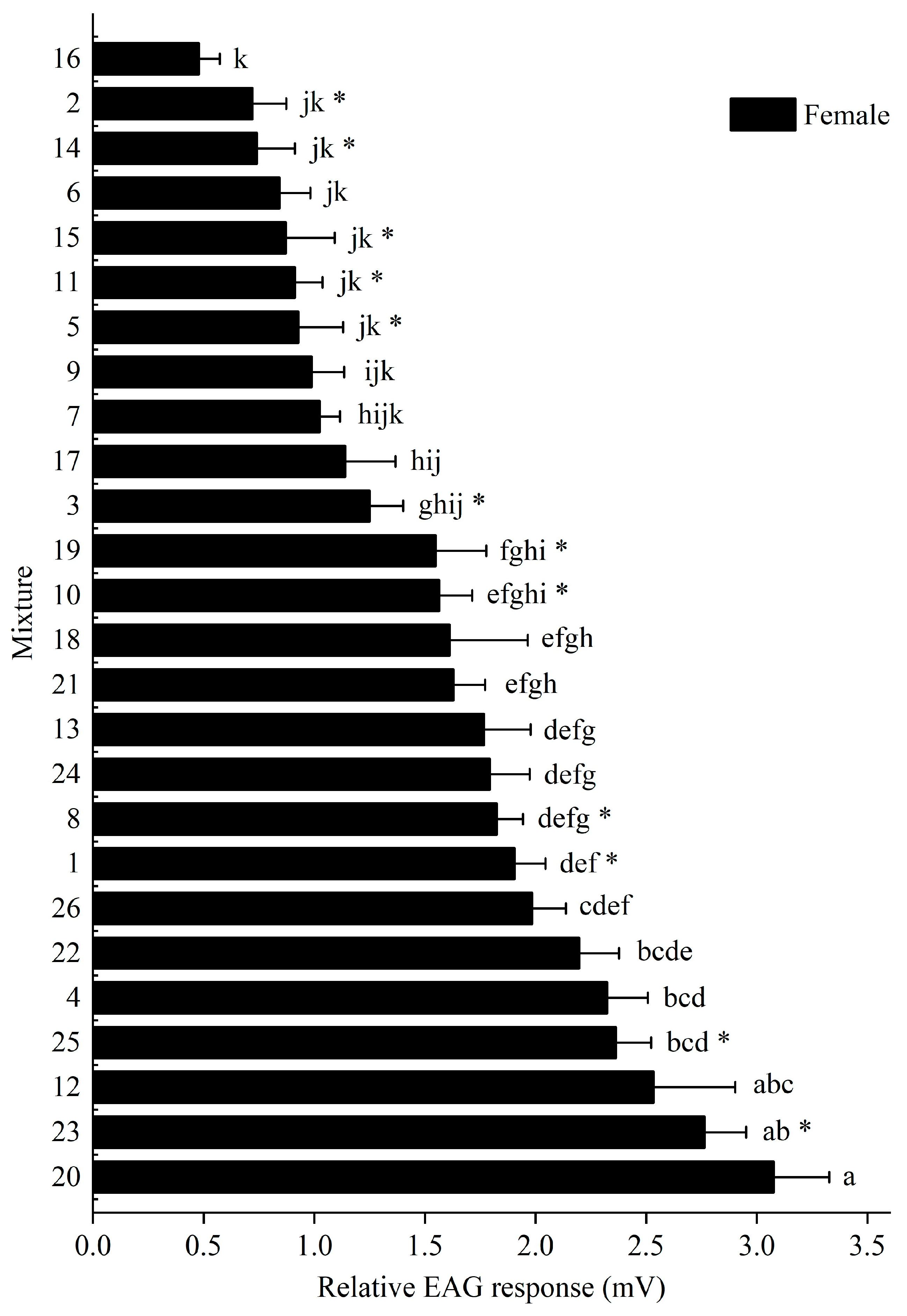

3.1. Electroantennogram Responses of M. signata to Plant Volatile Mixture

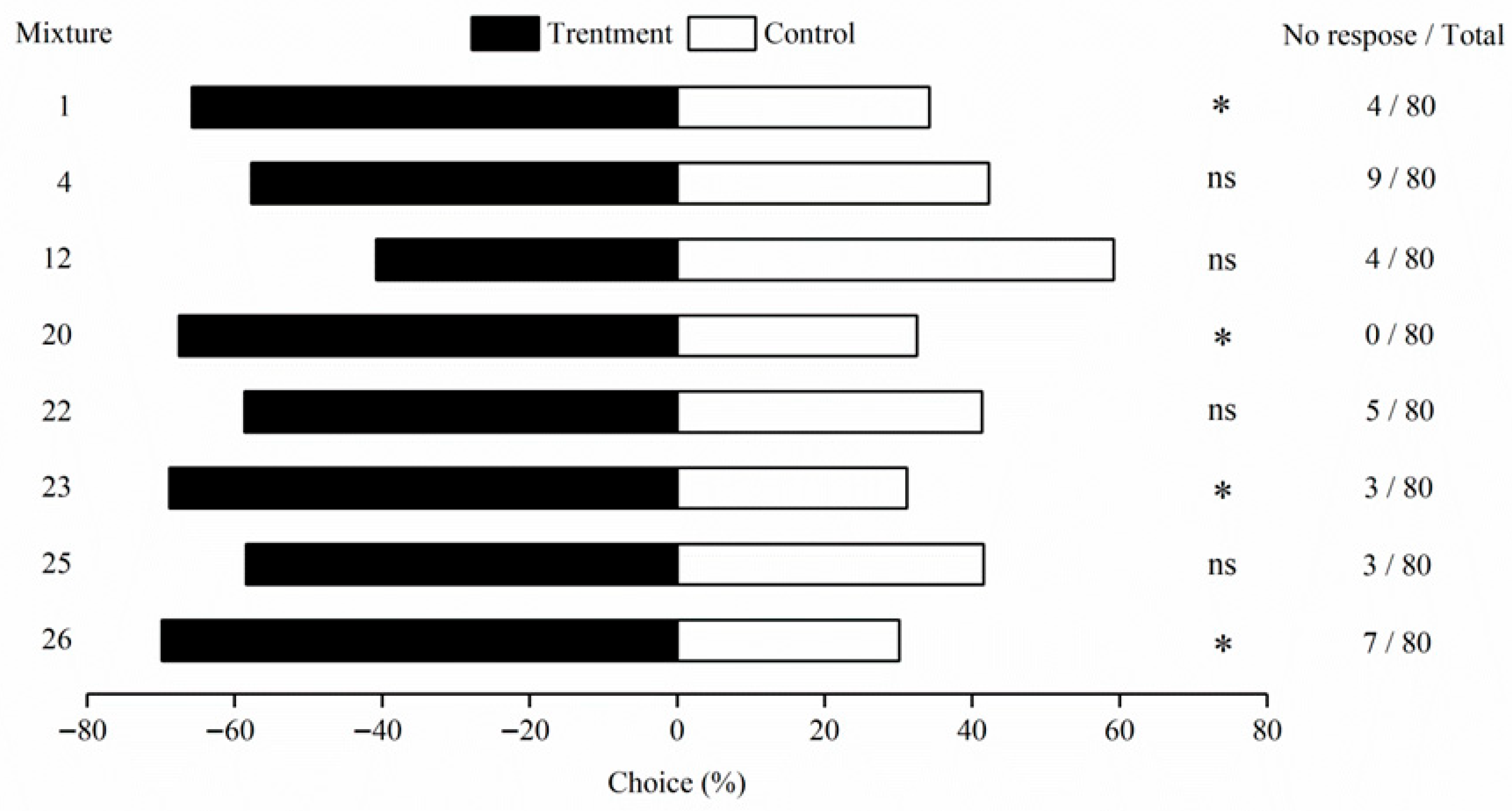

3.2. Behavioral Responses of M. signata to Mixtures of Plant Volatiles

3.3. Evaluation of the Field Level Trapping

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| EAG | Electroantennogram |

| SE | Standard error |

References

- Dudareva, N.; Negre, F.; Nagegowda, D.A. Plant Volatiles: Recent Advances and Future Perspectives. Crit. Rev. Plant Sci. 2006, 25, 417–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pichersky, E.; Noel, J.P.; Dudareva, N. Biosynthesis of plant volatiles: Nature’s diversity and ingenuity. Science 2006, 311, 808–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, D.M.; Himanen, S.J.; Nissinen, A.; Nerg, A.M.; Holopainen, J.K. Host location behavior of Cotesia plutellae Kurdjumov (Hymenoptera: Braconidae) in ambient and moderately elevated ozone infield conditions. Environ. Pollut. 2008, 156, 227–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knudsen, J.T.; Gershenzon, J. The chemistry diversity of floral scent. In Biology of Floral Scent; Dudareva, N., Pichersky, E., Eds.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2006; pp. 27–52. [Google Scholar]

- Lou, Y.; Cheng, J. Induced plant resistance to phytophagous insects. Acta Entomol. Sin. 1997, 40, 320–331. [Google Scholar]

- Bruce, T.J.A.; Wadhams, L.J.; Woodcock, C.M. Insect host location: A volatile situation. Trends Plant Sci. 2005, 10, 269–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turlings, T.C.J.; Erb, M. Tritrophic interactions mediated by herbivore-induced plant volatiles: Mechanisms, ecological relevance, and application potential. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2018, 1, 433–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branco, S.; Mateus, E.P.; Silva, M.; Mendes, D.; Rocha, S.M.; Mendel, Z.; Schütz, S.; Paiva, M.R. Electrophysiological and behavioural responses of the Eucalyptus weevil, Gonipterus platensis, to host plant volatiles. J. Pest Sci. 2019, 1, 221–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.L.; Li, X.W.; Xin, Z.J.; Han, J.J.; Ran, W.; Lei, S. Development of synthetic volatile attractant for male Ectropis obliqua moths. J. Integr. Agric. 2016, 7, 1532–1539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, X.M.; Bian, L.; Xu, X.X.; Luo, Z.X.; Li, Z.Q.; Chen, Z.M. Field background odour should be taken into account when formulating a pest attractant based on plant volatiles. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 41818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiu, C.L.; Pan, H.S.; Liu, B.; Luo, Z.X.; Williams, L.; Yang, Y.H.; Lu, Y.H. Perception of and behavioral responses to host plant volatiles for three Adelphocoris species. J. Chem. Ecol. 2019, 45, 779–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, P.Y.; Wang, S.Y.; Yang, X.K. Pyrophylloidea, Economic Insects of China, Volume 54 (II); Science Press: Beijing, China, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.H.; Shi, Y.X.; Song, L. The complete mitochondrial genome of an important agricultural pest Monolepta hieroglyphica (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae: Galerucinae). Mitochondrial DNA Part B 2020, 5, 1820–1821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Zhang, J.P.; Zhang, J.H.; Yu, F.H.; Li, G.W. Food preference of Monolepta hieroglyphica. J. Appl. Entomol. 2007, 44, 357–360. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.H.; Zhang, J.P.; Wang, P.L.; Li, Y. New Trends of Cotton Pests in Xinjiang and Their Control Countermeasures. China Cotton 2005, 32, 4–6. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, Y.H.; Zhang, J.P.; Chen, J.; Ouyang, D.H.; Li, G.W. Occurring Characteristic and Preventions and Control Strategy of Monolepta hieroglyphica(Motschulsky)-A New Pest of the Cotton Field in Xinjiang. Anhui Agric. Sci. Bull. 2007, 13, 120–121+230. [Google Scholar]

- LI, G.W.; Chen, X.L. Studies on biological characteristics and population dynamics of Monolepta hieroglyphica in cotton in Xinjiang. China Plant Prot. 2010, 30, 8–10. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, G.H.; Yi, W.; Li, Q.; Hu, H.Y. Research Progress of the Monolepta hieroglyphica (Motschulsky). China Plant Prot. 2016, 36, 19–26. [Google Scholar]

- Kogan, M. Integrated pest management: Historical perspectives and contemporary developments. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 1998, 43, 243–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.M.; Bai, P.H.; Zhang, J. Attraction of bruchid beetles Callosobruchus chinensis (L.) (Coleoptera: Bruchidae) to host plant volatiles. J. Integr. Agric. 2020, 19, 3035–3044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, W.J.; Meng, H.Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, G.; Zhi, M.T.; Li, G.W.; Chen, J. Identification of candidate chemosensory genes in the antennal transcriptome of Monolepta signata. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0301177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, J.Y.; He, W.J.; Li, H.Q.; Zhu, J.Y.; Li, X.G.; Tian, J.H.; Luo, M.D.; Chen, J. The Ultrastructure of Olfactory Sensilla Across the Antenna of Monolepta signata (Oliver). Insects 2025, 16, 573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallego, D.; Galián, J.; Diez, J.J.; Pajares, J.A. Kairomonal responses of Tomicus destruens (Col., Scolytidae) to host volatiles α-pinene and ethanol. J. Appl. Entomol. 2008, 132, 654–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiestl, F.P. The evolution of floral scent and insect chemical communication. Ecol. Lett. 2010, 13, 643–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Zhang, G.; Qiu, Y.; Luo, Z.; Cai, X.; Li, Z.; Bian, L.; Fu, N.; Zhou, L.; Magsi, F.H.; et al. Mixture of Synthetic Plant Volatiles Attracts More Stick Tea Thrips Dendrothrips minowai Priesner (Thysanoptera: Thripidae) and the Application as an Attractant in Tea Plantations. Plants 2024, 13, 1944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruce, T.J.A.; Pickett, J.A. Perception of plant volatile blends by herbivorous insects-finding the right mix. Phytochemistry 2011, 72, 1605–1611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karmakar, A.; Mitra, P.; Koner, A.; Das, S.; Barik, A. Fruit volatiles of creeping cucumber (Solena amplexicaulis) attract a generalist insect herbivore. J. Chem. Ecol. 2020, 46, 275–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, J.M.; Kundun, J.; Rowley, C.; Hall, D.; Douglas, P.; Pope, T.W. Electrophysiological and behavioral responses of adult vine weevil, Otiorhynchus sulcatus (Coleoptera: Curculionidae), to host plant odors. J. Chem. Ecol. 2019, 10, 858–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhikary, P.; Mukherjee, A.; Barik, A. Attraction of Callosobruchus maculatus (F.) (Coleoptera: Bruchidae) to four varieties of Lathyrus sativus L. seed volatiles. Bull. Entomol. Res. 2015, 105, 87–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhang, X.; Xiao, C. Behavioral responses of potato tuber moth (Phthorimaea operculella) to tobacco plant volatiles. J. Integr. Agric. 2020, 19, 325–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Chi, D.F.; Chen, H.Y.; Yu, J.; Li, X.C. EAG and Behavioral Responses of Monolepta hieroglyphica (Motschulsky) to Several Volatile Compounds. For. Res. 2013, 26, 488–493. [Google Scholar]

- Cuo, D.D.; Zhang, Z.H.; Chen, J.; Wang, S.S. Electrophysiological and behavioral responses of Monolepta hieroglyphica (Motschulsky) to 7 cotton and corn volatiles. Chin. Bull. Entomol. 2018, 55, 79–86. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z.H.; Chen, J.; Tang, S.Q.; Zhang, J.; Li, L. Olfactory Behavioral Response of the Monolepta hieroglyphica (Motschulsky) to volatiles of cotton and corn such as Dragosantol. Xinjiang Agric. Sci. 2018, 55, 285–292. [Google Scholar]

- Siderhurst, M.S.; Jang, E.B. Female-biased attraction of oriental fruit fly, Bactrocera dorsalis (Hendel), to a blend of host fruit volatiles from Terminalia catappa L. J. Chem. Ecol. 2006, 32, 2513–2524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, Y.; Zhou, C.; Chen, X.; Zheng, H. Foraging Behavior of the Dead Leaf Butterfly, Kallima inachus. J. Insect Sci. 2013, 13, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Derstine, N.T.; Meier, L.; Canlas, I.; Murman, K.; Cannon, S.; Carrillo, D.; Cooperband, M.F. Plant Volatiles Help Mediate Host Plant Selection and Attraction of the Spotted Lanternfly (Hemiptera: Fulgoridae): A Generalist with a Preferred Host. Environ. Entomol. 2020, 49, 1049–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, G.; Zhang, Y.N.; Gurr, G.M. Electroantennogram and behavioral responses of Cotesia plutellae to plant volatiles. Insect Sci. 2016, 23, 245–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cha, D.H.; Linn, C.E.; Teal, P.E.A.; Aijun, Z.; Roelofs, W.L.; Loeb, G.M. Eavesdropping on plant volatiles by a specialist moth: Significance of ratio and concentration. PLoS ONE 2011, 2, e17033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, J.W. Plant-insect Chemical Communication and Its Behavior Control. Physiol. Mol. Biol. Plants 2001, 27, 193–200. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, D.X.; Lu, F.P.; Mo, S.S.; Wang, A.P. The physiological activities of several plant volatiles on the antennae potential of adult Brontispa longissima (Gestro). Chinesa J. Trop. Crops 2006, 27, 66–69. [Google Scholar]

- Ning, T.; Fan, J.T.; Fang, Y.L.; Sun, J.H. Changes in contents of host volatile terpenes under different damaged states and electroantennogram response of Monochamus alternatus Hope to these volatiles. Acta Entomol. Sin. 2006, 49, 179–188. [Google Scholar]

- Dierks, A.; Fischer, K. Feeding responses and food preferences in the tropical, fruit-feeding butterfly, Bicyclus anynana. J. Insect Physiol. 2008, 54, 1363–1372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.T.; Su, Q.; Shi, L.L.; Chen, G.; Zeng, Y.; Shi, C.H.; Zhang, Y.J. Electrophysiological and behavioral responses of Bradysia odoriphaga (Diptera: Sciaridae) to volatiles from its Host Plant, Chinese Chives (Allium tuberosum Rottler ex Spreng). J. Econ. Entomol. 2019, 112, 1638–1644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.H.; Schlyter, F.; Chen, G.F.; Wang, Y.J. Electrophysiological and Behavioral Responses of Ips subelongatus to Semiochemicals from Its Hosts, Non-hosts, and Conspecifics in China. J. Chem. Ecol. 2007, 33, 391–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, R.; Zhang, P.J.; Zhang, N.Z. Electrophysiological and behavioral responses of male fall webworm moths (Hyphantria cunea) to Herbivory-induced mulberry (Morus alba) leaf volatiles. PLoS ONE 2018, 7, e49256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thöming, G.; Knudsen, G.K. Attraction of pea moth Cydia nigricana to pea flower volatiles. Phytochemistry 2014, 100, 66–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrivastava, G.; Rogers, M.; Wszelaki, A.; Panthee, D.R.; Chen, F. Plant volatiles-based insect pest management in organic farming. Crit. Rev. Plant Sci. 2010, 29, 123–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero, P.; Ibarra-Juárez, L.A.; Carrillo, D.; Guerrero-Analco, J.A.; Kendra, P.E.; Kiel-Martínez, A.L.; Guillén, L. Electroantennographic Responses of Wild and Laboratory-Reared Females of Xyleborus affinis Eichhoff and Xyleborus ferrugineus (Fabricius) (Coleoptera: Curculionidae: Scolytinae) to Ethanol and Bark Volatiles of Three Host-Plant Species. Insects 2022, 13, 655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, W.Z.; Yang, L.; Shen, X.W.; Yuan, Y.H.; Yuan, G.H.; Luo, M.H.; Guo, X.R. Prescription screening and field evaluation of broad spectrum attractants of scarab beetles from Ricinus communis. Chin. J. Eco-Agric. 2013, 21, 480–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Ju, Q.; Jin, Q.; Jiang, X.J.; Su, W.H.; Zhang, G.L.; Xie, M.H.; Qu, M.J. Field Trapping Efficacy of Different Lures and Traps on Holotrichia parallela (Coleoptera, Scarabaeidae, Melolonthinae). J. Peanut Sci. 2015, 44, 41–46. [Google Scholar]

- Honda, K.; Ômura, H.; Hayashi, N. Identification of floral volatiles from Ligustrum japonicum that stimulate flower-visiting by cabbage butterfly, Pieris rapae. J. Chem. Ecol. 1998, 24, 2167–2180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ômura, H.; Honda, K. Behavioral and electroantennographic responsiveness of adult butterflies of six nymphalid species to food-derived volatiles. Chemoecology 2009, 19, 227–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knudsen, G.K.; Bengtsson, M.; Kobro, S.; Jaastad, G.; Witzgall, P. Discrepancy in laboratory and field attraction of apple fruit moth Argyresthia conjugella to host plant volatiles. Physiol. Entomol. 2008, 33, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knudsen, G.K.; Tasin, M. Spotting the invaders: A monitoring system based on plant volatiles to forecast apple fruit moth attacks in apple orchards. Basic Appl. Ecol. 2015, 16, 354–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Kang, L. Roles of (Z)-3-hexenol in plant-insect interactions. Plant Signal. Behav. 2011, 6, 369–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinecke, A.; Ruther, J.; Tolasch, T. Alcoholism in cockchafers: Orientation of male Melolontha melolontha towards green leaf alcohols. Die Naturwissenschaften 2002, 89, 265–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruther, J. Male-biassed response of garden chafer, Phyllopertha horticola L., to leaf alcohol and attraction of both sexes to floral plant volatiles. Chemoecology 2004, 14, 187–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, G.V.P.; Guerrero, A. Interactions of insect pheromones and plant semiochemicals. Trends Plant Sci. 2004, 9, 253–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.G.; Jin, Y.J.; Luo, Y.Q.; Xu, Z.C.; Chen, H.J. Leaf Volatiles from Host Tree Acer negundo: Diurnal Rhythm and Behavior Responses of Anoplophora glabripennis to Volatiles in Field. Axiaa Bot. Sin. 2003, 45, 177–182. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.S.; Li, F.X.; Wen, D.H. Review of Research on Attractant from Plants to Monochamus alternatus Hope. J. Henan Agric. Sci. 2014, 43, 5–10. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Lu, Q. Research on the EAG and behavial responses of Asias halodendri to the plant Prunus armeniaca’ s volatiles. J. Environ. Entomol. 2016, 38, 384–392. [Google Scholar]

- Ze, S.X.; Zhao, N.; Wang, D.W.; Ji, M.; Yang, B. The efficacy of Trans-2-hexenal as an Attractant for adult Monochamus alternatus. For. Pest Dis. 2013, 32, 46. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, D.R.; Borden, J.H. β-Phellandrene: Kairomone for pine engraver, Ips pini(Say) (Coleoptera: Scolytidae). J. Chem. Ecol. 1990, 16, 2519–2531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Lu, Q.; Zhu, G.P.; LIi, M. Research on the EAG and behavioral responses of Chlorophorus diadema to eleven Vitis vinifera and Prunus armeniaca volatiles. Chin. J. Appl. Entomol. 2015, 52, 1113–1122. [Google Scholar]

- Qiu, H.; Zhao, D.; Fox, E.G.P.; Ling, S.; Qin, C.; Xu, J. Chemical Cues Used by the Weevil Curculio chinensis in Attacking the Host Oil Plant Camellia oleifera. Diversity 2022, 14, 951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Gao, W.; Chen, X.C.; Zhou, Y.T.; Cui, W.C. Electroantennogram response of Anoplophora glabripennis (Motsch.) to Acer negundo volatiles. For. Pest Dis. 2016, 35, 9–14. [Google Scholar]

| Compounds | CAS Number | Purity (%) | Producer |

|---|---|---|---|

| β-ocimene | 3779-61-1 | 98 | Toronto Research Chemicals (Vaughan, ON, Canada) |

| 1-heptene | 592-76-7 | 98 | Bejing Ouhe Technology Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China) |

| aromadendrene | 489-39-4 | 97 | Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA) |

| trans-2-hexen-1-al | 6728-26-3 | 98 | Bejing Ouhe Technology Co., Ltd. |

| α-farnesene | 502-61-4 | 98 | Toronto Research Chemicals |

| heptadecane | 629-78-7 | 98 | Bejing Ouhe Technology Co., Ltd. |

| trans-2-hexen-1-ol | 928-95-0 | 98 | Bejing Ouhe Technology Co., Ltd. |

| (Z)-3-hexen-1-ol (Leaf alcohol) | 928-96-1 | 98 | Bejing Ouhe Technology Co., Ltd. |

| α-phellandrene | 99-83-2 | 98 | Bejing Ouhe Technology Co., Ltd. |

| β-pinene | 127-91-3 | 98 | Bejing Ouhe Technology Co., Ltd. |

| α-caryophyllene | 6753-98-6 | 98 | Bejing Ouhe Technology Co., Ltd. |

| hexadecene | 629-73-2 | 98 | Bejing Ouhe Technology Co., Ltd. |

| nerolidol | 7212-44-4 | 98 | Bejing Ouhe Technology Co., Ltd. |

| 3-methylpentanal | 15877-57-3 | 98 | Toronto Research Chemicals |

| n-hexane | 110-54-3 | 97 | Tianjin Fuyu Fine Chemical Co., Ltd. (Tianjin, China) |

| paraffin liquid | 8042-47-5 | 99 | Tianjin Yongcheng Fine Chemical Co., Ltd. (Tianjin, China) |

| Mixture | Composition | Concentration (μL/mL) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | β-pinene + leaf alcohol | 10 + 10 |

| 2 | β-pinene + trans-2-hexen-1-al | 10 + 10 |

| 3 | β-pinene + aromadendrene | 10 + 10 |

| 4 | α-phellandrene + trans-2-hexen-1-ol | 10 + 10 |

| 5 | α-phellandrene + trans-2-hexen-1-al | 10 + 10 |

| 6 | α-phellandrene + leaf alcohol | 10 + 10 |

| 7 | α-phellandrene + α-farnesene | 10 + 1 |

| 8 | trans-2-hexen-1-al + leaf alcohol | 10 + 10 |

| 9 | trans-2-hexen-1-al + trans-2-hexen-1-ol | 10 + 10 |

| 10 | trans-2-hexen-1-al + aromadendrene | 10 + 10 |

| 11 | leaf alcohol + 1-heptene | 10 + 10 |

| 12 | leaf alcohol + α-farnesene | 10 + 1 |

| 13 | trans-2-hexen-1-ol + 1-heptene | 10 + 10 |

| 14 | trans-2-hexen-1-ol + nerolidol | 10 + 10 |

| 15 | 1-heptene + nerolidol | 10 + 10 |

| 16 | 1-heptene + α-farnesene | 10 + 1 |

| 17 | nerolidol + aromadendrene | 10 + 10 |

| 18 | aromadendrene + α-farnesene | 10 + 1 |

| 19 | β-pinene + α-phellandrene + trans-2-hexen-1-al | 10 + 10 + 10 |

| 20 | leaf alcohol + trans-2-hexen-1-ol +1-heptene | 10 + 10 + 10 |

| 21 | nerolidol + aromadendrene + α-farnesene | 10 + 10 + 1 |

| 22 | β-pinene + trans-2-hexen-1-al +leaf alcohol | 10 + 10 + 10 |

| 23 | α-phellandrene + trans-2-hexen-1-ol + 1-heptene | 10 + 10 + 10 |

| 24 | leaf alcohol + nerolidol + aromadendrene | 10 + 10 + 10 |

| 25 | trans-2-hexen-1-ol + nerolidol + aromadendrene | 10 + 10 + 10 |

| 26 | trans-2-hexen-1-al + 1-heptene + trans-2-hexen-1-ol | 10 + 10 + 10 |

| Combinations | Gender | χ2 | df | p | p (Bonferroni Corrected) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mixture 1 vs. CK | Female | 3.981 | 1 | 0.046 | 0.067 |

| Mixture 4 vs. CK | Female | 0.908 | 1 | 0.341 | 0.430 |

| Mixture 12 vs. CK | Female | 1.333 | 1 | 0.248 | 0.320 |

| Mixture 20 vs. CK | Female | 5.055 | 1 | 0.025 | 0.037 |

| Mixture 22 vs. CK | Female | 1.171 | 1 | 0.279 | 0.357 |

| Mixture 23 vs. CK | Female | 5.762 | 1 | 0.016 | 0.025 |

| Mixture 25 vs. CK | Female | 1.126 | 1 | 0.289 | 0.368 |

| Mixture 26 vs. CK | Female | 6.248 | 1 | 0.012 | 0.020 |

| Mixture 4 vs. CK | Male | 1.126 | 1 | 0.289 | 0.368 |

| Mixture 8 vs. CK | Male | 0.253 | 1 | 0.615 | 0.733 |

| Mixture 19 vs. CK | Male | 4.244 | 1 | 0.039 | 0.058 |

| Mixture 20 vs. CK | Male | 0.805 | 1 | 0.370 | 0.461 |

| Mixture 22 vs. CK | Male | 6.061 | 1 | 0.014 | 0.021 |

| Mixture 23 vs. CK | Male | 4.144 | 1 | 0.042 | 0.061 |

| Mixture 24 vs. CK | Male | 0.187 | 1 | 0.666 | 0.857 |

| Mixture 26 vs. CK | Male | 2.522 | 1 | 0.112 | 0.154 |

| Treatment | Date | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 14 July | 16 July | 18 July | 20 July | 22 July | 24 July | 26 July | |

| Mixture 1 | 1.7 ± 1.2 a | 2.7 ± 0.3 ab | 1.0 ±1.0 ab | 2.3 ± 0.3 a | 0.7 ± 0.7 a | 1.3 ± 0.9 ab | 1.0 ± 0.6 a |

| Mixture 19 | 2.0 ± 1.5 a | 3.7 ± 1.3 ab | 1.0 ± 0.0 ab | 3.3 ± 2.3 a | 0.7 ± 0.3 a | 0.7 ± 0.7 b | 0.3 ± 0.3 a |

| Mixture 20 | 1.7 ± 1.2 a | 2.7 ± 0.9 ab | 3.3 ± 1.7 a | 1.3 ± 0.3 a | 0.3 ± 0.3 a | 2.0 ± 0.6 ab | 1.3 ± 0.9 a |

| Mixture 22 | 1.7 ± 0.3 a | 5.0 ± 1.2 a | 1.3 ± 0.3 ab | 2.0 ± 0.6 a | 1.0 ± 0.6 a | 1.7 ± 0.7 ab | 1.0 ± 0.6 a |

| Mixture 23 | 4.0 ± 1.5 a | 4.3 ± 1.2 a | 2.3 ± 0.9 ab | 2.3 ± 0.7 a | 1.0 ± 0.6 a | 3.3 ± 0.9 a | 0.3 ± 0.3 a |

| Mixture 26 | 2.7 ± 0.7 a | 3.3 ± 0.7 ab | 3.0 ± 0.6 a | 2.0 ± 1.5 a | 1.3 ± 0.3 a | 1.0 ± 1.0 ab | 0.7 ± 0.7 a |

| CK | 0.7 ± 0.3 a | 1.0 ± 0.0 b | 0.0 ± 0.0 b | 0.7 ± 0.3 a | 0.3 ± 0.3 a | 0.7 ± 0.3 b | 0.3 ± 0.3 a |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, L.; Cao, J.; Cai, Z.; Chen, J. Plant Volatile Organic Compounds Attractive to Monolepta signata (Olivier). Insects 2025, 16, 1233. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects16121233

Li L, Cao J, Cai Z, Chen J. Plant Volatile Organic Compounds Attractive to Monolepta signata (Olivier). Insects. 2025; 16(12):1233. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects16121233

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Lun, Jiyu Cao, Zhiping Cai, and Jing Chen. 2025. "Plant Volatile Organic Compounds Attractive to Monolepta signata (Olivier)" Insects 16, no. 12: 1233. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects16121233

APA StyleLi, L., Cao, J., Cai, Z., & Chen, J. (2025). Plant Volatile Organic Compounds Attractive to Monolepta signata (Olivier). Insects, 16(12), 1233. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects16121233