Simple Summary

This study investigated the sublethal effects of tetraniliprole on the invasive tomato pest, Tuta absoluta. Although tetraniliprole caused high toxicity in third-instar larvae, sublethal (LC10) and low lethal (LC30) concentrations had complex effects across generations. The directly exposed generation (F0) experienced decreased development and reproduction. However, its offspring (F1 and F2) showed a dual response: the LC10 promoted faster development and increased population growth (hormetic-like effects), while the LC30 continued to cause negative effects. These changes were linked to altered expression of key genes involved in reproduction, development, and detoxification. The results highlight a significant risk of unintended population resurgence at sublethal concentrations and emphasize the importance of considering these transgenerational effects in resistance management strategies.

Abstract

The South American tomato pinworm, Tuta absoluta (Meyrick), is among the most destructive invasive pests of tomato globally. The diamide insecticide tetraniliprole is increasingly used for its management. This study examines the sublethal effects of tetraniliprole on T. absoluta larvae, with a focus on its transgenerational impacts. Bioassays demonstrated that tetraniliprole was highly toxic to third-instar T. absoluta larvae, with an LC50 of 0.029 mg/L. Sublethal (LC10) and low lethal concentrations (LC30) were used to investigate their impact on developmental, reproductive, and population parameters across two subsequent generations (F1 and F2). In the parental (F0) generation, exposure to tetraniliprole at both concentrations significantly prolonged larval and pupal durations and reduced adult longevity and fecundity. In both F1 and F2 generations, concentration-dependent effects were observed—LC10 accelerated development and enhanced fecundity and population growth, indicative of a hormetic response, whereas LC30 delayed development and suppressed reproduction and survival. Life table analyses revealed significant changes in the r, λ, and T, particularly under LC30. Additionally, the RT-qPCR analysis revealed the downregulation of development and reproduction-related genes (Vg, VgR, and JHBP) in the F0 generation following exposure to tetraniliprole (LC10 and LC30). In contrast, these genes were upregulated in the progeny generations (F1 and F2) at LC10. Furthermore, the overexpression of key detoxification genes, particularly CYP4M116 and CYP6AW1, persisted across all three generations. Taken together, these findings reveal a substantial risk of unintended population resurgence (hormesis effects) at sublethal concentrations, underscoring the importance of integrating transgenerational consequences into insecticide resistance management programs for sustainable control of this key insect pest.

1. Introduction

The South American tomato pinworm, Tuta absoluta (Meyrick) (Lepidoptera: Gelechiidae), is recognized as one of the most devastating insect pests of tomato crops [1,2]. Since its emergence in South America, T. absoluta has rapidly expanded its geographic range and now invades over 90 countries worldwide [2,3]. In addition to tomatoes, this invasive pest threatens other economically significant solanaceous crops such as potato, eggplant, pepper, and tobacco [4,5]. Its high reproductive capacity, cryptic larval behavior, and resistance to conventional insecticides contribute to its invasiveness and the extensive damage it causes to crops [6,7]. Infestations by T. absoluta result in substantial yield losses, reduced fruit quality, and increased pest management costs [2,8,9].

Although several eco-friendly approaches are available [10,11], chemical insecticides remain widely used against this pest due to their rapid results. Tetraniliprole, a third-generation anthranilic diamide insecticide, acts by targeting the ryanodine receptors in insects, disrupting calcium ion regulation and ultimately causing paralysis and death [12]. This mode of action is effective against a broad spectrum of insect pests, including Lepidoptera, Coleoptera, and Diptera, with the added advantage of minimal toxicity to non-target mammals [13,14,15]. However, insecticides are known to degrade over time following initial field application [16], potentially exposing arthropod populations to sublethal doses or concentrations [17]. Such exposures can induce a variety of physiological and behavioral changes, affecting insect survival, development, reproduction, and even resistance evolution [18,19,20,21]. Interestingly, sublethal doses or concentrations can sometimes paradoxically enhance certain biological traits, such as reproduction, a phenomenon known as hormesis [22,23].

Sublethal effects can also impact insect reproductive systems at the molecular level. For example, vitellogenin (Vg), the precursor of vitellin (Vn), and its receptor (VgR), which facilitates Vg transport into oocytes, play crucial roles in insect fecundity and are often disrupted under insecticidal stress [24,25]. These disruptions may affect both directly exposed individuals and their progeny, highlighting the need to assess both direct and transgenerational impacts of insecticides. Beyond reproductive genes, cytochrome P450 monooxygenases (CYPs) are central to insecticide detoxification and have long been implicated in resistance development. The upregulation of cytochrome P450 enzymes during resistance development in T. absoluta leads to decreased population growth rates since it creates substantial fitness costs, manifesting when insecticide pressure disappears. By investing metabolic resources in resistance mechanisms, insects suffer fitness costs that trigger reduced fecundity stress during development and growth, impairing total fitness [19,20,21].

Life table analyses offer a comprehensive framework to assess the cumulative effects of various stressors on insect populations, including survival, development, longevity, and reproductive potential [26,27]. Unlike traditional female-only life tables [28], the age-stage, two-sex life table approach incorporates both sexes and accounts for individual variability in developmental rates, thereby providing more accurate and holistic insights into population dynamics [27,29].

Given the widespread use of tetraniliprole and the growing concern about its sublethal impacts, it is essential to evaluate its effects not only on exposed individuals but also on their progeny. The current study investigates the sublethal and low-lethal effects of tetraniliprole on T. absoluta by assessing key biological traits across three generations (F0, F1, and F2) using an age-stage, two-sex life table approach. The findings from this study will enhance our understanding of tetraniliprole’s impact on population fitness and reproductive potential and offer valuable insights for the sustainable management of T. absoluta.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Insect

The initial colony of T. absoluta was established from larvae collected in tomato fields in Yuxi (24.3473° N, 102.5274° E), Yunnan Province, China, in June 2018. The population was subsequently maintained under laboratory conditions for several years without exposure to any insecticides to ensure a susceptible baseline strain. Rearing was conducted on pesticide-free tomato plants under controlled environmental conditions: 25 ± 1 °C, 60 ± 5% relative humidity, and a photoperiod of 16:8 h (light/dark).

2.2. Toxicity Bioassays

Adult T. absoluta were introduced onto fresh, pesticide-free tomato plants for a 12 h oviposition period. Following egg deposition, the infested plants were transferred to clean rearing cages to allow for hatching and larval development. This protocol ensured uniformity in larval age and developmental stage, with third-instar larvae subsequently selected for bioassay experiments. These larvae were designated as the parental (F0) generation. The toxicity of tetraniliprole against third-instar T. absoluta larvae was evaluated using the standardized leaf-dip bioassay method described [30], under the same controlled laboratory conditions. A technical grade (95% purity) formulation of tetraniliprole was used to prepare a stock solution in analytical-grade acetone, which was serially diluted in distilled water containing 0.05% Triton X-100 (Sangon Biotech Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China) to obtain seven concentrations (0.0078, 0.0156, 0.0312, 0.0625, 0.125, 0.25, and 0.5 mg/L). The control treatment consisted of distilled water containing 0.05% Triton X-100 alone. Fresh tomato leaves were individually immersed in each insecticide concentration for 15 s and then air-dried at room temperature for 1–2 h. To maintain leaf turgidity, the petioles were wrapped in moistened cotton wool. Upon air-drying, treated leaves were placed in Petri dishes (diameter 9 cm × height 1.5 cm) lined with filter paper. For each replication under both treatment and control, 20 third-instar larvae were carefully transferred onto the treated leaves. Each treatment was replicated three times. Larval mortality was recorded 48 h post-treatment. Larvae unresponsive to gentle probing with a fine brush were recorded as dead. The mortality data were used for subsequent toxicity analysis.

2.3. Sublethal Effects of Tetraniliprole on Life-History Traits of the F0 Generation

Uniform-aged third-instar T. absoluta larvae were used in life table studies and designated as the F0 generation. Sublethal and low lethal concentrations of tetraniliprole (LC10 and LC30) were applied to assess their effects on the life-history traits of directly exposed individuals. Tomato leaves were treated with the respective concentrations following the procedure outlined in the toxicological bioassay section. After 72 h of exposure, seventy surviving larvae from each treatment group (LC10, LC30, and control) were individually transferred to separate Petri dishes containing untreated, pesticide-free tomato leaves. Each larva was treated as a single replicate. Moistened cotton wool was used to wrap the petioles of the leaves to prevent wilting and maintain turgor, and leaves were replaced as needed throughout rearing. Larval development and survival were monitored daily. Upon pupation, each individual was transferred to a clean glass tube (1.5 cm diameter × 8 cm height), where pupal duration and survival until adult emergence were recorded. After emergence, one male and one female were paired in a larger glass tube (3 cm diameter × 20 cm height) containing fresh, untreated tomato leaves and a cotton ball soaked in a 10% honey solution as a food source. The leaves with deposited eggs were collected and replaced daily. Adult survival and female fecundity were recorded daily until the death of all individuals. All experimental procedures were conducted under the same controlled environmental conditions.

2.4. Transgenerational Effects of Tetraniliprole on Biological Parameters of Subsequent Generations (F1 and F2)

Transgenerational effects of sublethal and low lethal concentrations of tetraniliprole (LC10 and LC30, respectively) on F1 and F2 generations of T. absoluta were evaluated using the same experimental protocol used for the F0 generation. Eggs laid by F0 adults were individually transferred to clean Petri dishes containing untreated tomato leaves and maintained under the same controlled conditions. Each egg served as a single replicate. All subsequent developmental, survival, and reproductive parameters were recorded daily throughout the life cycle. For the F2 generation, eggs produced by the F1 adults were similarly transferred to untreated tomato leaves and reared using the same procedure. Data collection on developmental duration, survival rates, adult longevity, and fecundity followed the standardized protocol used for the previous generations.

2.5. Tetraniliprole-Induced Transgenerational Effects on Developmental and Resistance Genes

The mRNA expression levels of development (juvenile hormone binding protein), reproduction (Vg, VgR), and resistance genes (CYP15C1, CYP321C40, CYP339A1, CYP4M116, CYP4S55, CYP6AB327, CYP6AW1, CYP9A307v2) were investigated in response to sublethal and low lethal exposure to tetraniliprole. Total RNA was extracted from third-instar T. absoluta larvae at F0, F1, and F2 generations using the RNAsimple Total RNA kit (Tiangen Biotech (Beijing) Co., Ltd., Beijing, China) following the recommended protocol. The RNA quality and quantity were determined by the Bioanalyzer Agilent 2100 (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA). 1 μg of total RNA was used to synthesize the cDNA using the iScriptTM cDNA Synthesis Kit (Bio-Rad, Berkeley, CA, USA) according to the recommended instructions. RT-qPCR was conducted on a 10 μL total volume of a reaction consisting of 5 μL 2× Kappa SYBR Green I qPCR Mix, 0.2 μL forward and reverse primers (10 μM each), 1 μL of cDNA template, and the remaining volume was nuclease-free water using a CFX Connect TM Real-Time System (Bio-Rad, Berkeley, CA, USA). The thermocycling conditions of each qPCR consist of 95 °C for 45 s, followed by 40 cycles of 95 °C for 15 s, 50–65 °C for 15 s, and 70 °C for 30–60 s. Gene expressions were calculated using the 2−∆∆Ct method [31]. Elongation factor 1 alpha (EF1α) and ribosomal protein L28 (RPL28) were used as housekeeping genes to normalize the gene expressions. RT-qPCR experiments consist of three biological and three technical replicates. The primers used in the current study are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

The primers used for RT-qPCR and dsRNA synthesis.

2.6. Data and Life Table Analysis

Mortality data were analyzed using probit regression in PoloPlus software version 2.0 (LeOra Software Inc., Berkeley, CA, USA) to estimate the LC10, LC30, and LC50 values of tetraniliprole, along with their corresponding 95% confidence intervals [19]. Life-history data of T. absoluta were analyzed based on the age-stage, two-sex life table theory using the TWOSEX-MSChart program (Ver. 07.06.2024) [26,32], which enables comprehensive evaluation of developmental, survival, and reproductive parameters across variable life stages and sexes. Means, variances, and standard errors of the biological and demographic parameters were estimated using a bootstrap resampling procedure with 100,000 iterations [33,34,35]. Statistical differences among treatment groups (LC10, LC30, and control) and between generations (F0, F1, and F2) within each treatment group were determined using the paired bootstrap test at a significance level of p < 0.05. Survival rate, fecundity, life expectancy, and reproductive rate figures were made using SigmaPlot 12.0 (Systat Software Inc., San Jose, CA, USA).

2.7. Population Projection

The TIMING-MSChart program (Ver. 05.07.2024) [36] was used to analyze the population projection according to the standard method [37]. The simulation began with an initial population of 10 T. absoluta eggs for each of the control, LC10, and LC30 cohorts. Under the assumption of no biotic or abiotic suppression, the model projected population growth over 120 days for the F1 and F2 generations. The net reproductive rate (R0) confidence interval was generated from 100,000 bootstrap iterations, with its 2.5th and 97.5th percentiles (representing the 2500th and 97,500th sorted values) defining the lower and upper bounds. These percentiles allowed the simulation of population growth to account for all inherent variability and uncertainty [38]. The outcomes of the log-based projections were then visualized using ‘ggplot2’ package of R (Ver. 4.1.3 Vienna, Austria).

3. Results

3.1. Toxicity of Tetraniliprole to Tuta absoluta Larvae

The LC10, LC30, and LC50 of tetraniliprole against T. absoluta larvae were determined through probit regression analysis. The estimated values were 0.008 mg/L (LC10), 0.018 mg/L (LC30), and 0.029 mg/L (LC50), with corresponding 95% confidence intervals (Table 2). These concentrations, along with a control (acetone), were subsequently used to evaluate their effects on the life table parameters of T. absoluta across two consecutive generations (F1 and F2).

Table 2.

Toxicity of tetraniliprole against third-instar Tuta absoluta after 48 h exposure.

3.2. The Sublethal Effects of Tetraniliprole on the Development of the Parental Generation (F0)

The sublethal effects of tetraniliprole at LC10 and LC30 concentrations on the developmental biology of the parental generation (F0) of T. absoluta are summarized in Table 3. Exposure to both concentrations significantly extended the larval and pupal developmental durations compared to the control group. Specifically, larval development was prolonged by 2.00 and 3.11 days at LC10 and LC30, respectively, while pupal development increased by 0.91 and 1.53 days. In contrast, adult longevity was significantly reduced in both males and females treated with tetraniliprole, indicating an adverse effect on adult survival. Moreover, a significant reduction in female fecundity was observed, with egg production decreasing by 67.64 and 121.72 eggs/female at LC10 and LC30, respectively, compared to untreated controls. Additionally, reproductive timing was also disrupted. Both the oviposition period and the adult preoviposition period (APOP) were significantly shortened in treated individuals, further demonstrating the negative impact of tetraniliprole on reproductive capacity and temporal dynamics of T. absoluta.

Table 3.

Duration of various developmental stages and some reproductive parameters of parental generation (F0) of Tuta absoluta treated with LC10 and LC30 of tetraniliprole.

3.3. The Sublethal Effects of Tetraniliprole on the Development of the Subsequent Generations (F1 and F2)

The sublethal effects of tetraniliprole on the development and longevity of T. absoluta in the F1 and F2 generations are detailed in Table 4. At LC10, a significant reduction in the duration of egg, larval, and pupal stages was observed relative to the control, suggesting an acceleration of immature development. Conversely, LC30 exposure significantly prolonged all three developmental stages across both generations, indicating a dose-dependent developmental delay. When comparing generations, only the egg and larval developmental periods were significantly shorter in LC30-exposed individuals in the F2 generation compared to F1.

Table 4.

Duration of various developmental stages of two subsequent Tuta absoluta generations (F1 and F2), whose parents (F0) were treated with LC10 and LC30 of tetraniliprole.

Female longevity showed contrasting trends across concentrations and generations. In the F1 generation, LC10 exposure significantly increased female lifespan by 2.6 days, while LC30 exposure reduced it by 3.95 days. However, in the F2 generation, no statistically significant difference in female longevity was observed between the control and LC10 treatment groups, but LC30 reduced female lifespan from 23.80 ± 0.95 to 20.37 ± 0.77 days, confirming the persistent detrimental effects of higher sublethal doses. Male longevity increased significantly under LC10 in both generations, but was consistently and significantly reduced at LC30 exposure. Interestingly, male longevity was significantly higher in the F2 than in the F1 within the LC30 treatment group. No significant variation in total female longevity was detected between treatment groups or across generations. However, total male longevity was significantly reduced under both LC10 and LC30 exposures in the F1 generation, with no notable differences observed in the F2 generation.

3.4. The Transgenerational Sublethal Effects of Tetraniliprole on the Progeny Generations (F1 and F2) of Tuta absoluta

The sublethal effects of tetraniliprole on the life table parameters of T. absoluta in the F1 and F2 generations are presented in Table 5. No significant differences in the net reproductive rate (R0) were observed between the control and either of the sublethal treatments (LC10 or LC30), nor were intergenerational variations detected for this parameter, indicating a degree of reproductive stability under sublethal stress. However, both the intrinsic rate of increase (r) and the finite rate of increase (λ) exhibited concentration-dependent responses. Specifically, LC10 exposure significantly elevated both parameters across generations, suggesting a potential hormetic effect. In contrast, exposure to LC30 markedly suppressed both r and λ values in both generations. The mean generation time (T) was also notably affected by tetraniliprole. T was significantly shortened under LC10 (from 28.50 ± 0.32 to 26.63 ± 0.33 days in the F1 generation, and from 29.74 ± 0.33 to 27.00 ± 0.39 days in the F2), while LC30 increased T by 3.96 and 2.65 days in F1 and F2, respectively.

Table 5.

Reproduction and life table parameters of two subsequent (F1 and F2) generations of Tuta absoluta, whose parents (F0) were treated with LC10 and LC30 of tetraniliprole.

Fecundity responses were dose- and generation-dependent. LC10 significantly enhanced fecundity in both F1 and F2 generations, while LC30 significantly reduced fecundity in the F1 generation, with no significant difference in the F2. Notably, fecundity under LC30 improved by 14.76% in F2 compared to F1. Regarding the oviposition period, no significant difference was recorded in LC10-treated individuals in F1. However, in F2, oviposition was significantly extended (from 12.17 ± 0.52 to 14.83 ± 0.56 days). An opposite trend was observed for LC30-exposed insects, where oviposition was reduced relative to the control. Nonetheless, both LC10 and LC30 treatments resulted in a notable increase in oviposition period in the F2 generation compared to F1, highlighting a generational effect. The adult preoviposition period (APOP) was not considerably affected by LC10, but significantly extended under LC30 in both generations. A similar pattern was observed for the total preoviposition period (TPOP), which was significantly increased under LC30 but reduced under LC10.

3.5. Age-Stage Specific Survival Rate, Fecundity, and Life Expectancy of Tetraniliprole Exposed Tuta absoluta

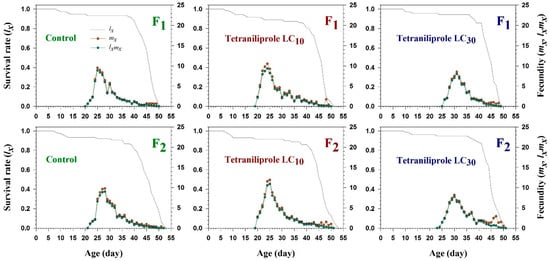

The age-specific survival rate (lx), age-specific fecundity (mx), and the age-specific maternity (lxmx) of T. absoluta in the F1 and F2 generations following tetraniliprole exposure are illustrated in Figure 1. The mx curves exhibited marked differences in fecundity across generations and treatment levels. At LC10, maximum fecundity (0.4–0.6 offspring/female/day) occurred around day 25 in both F1 and F2 generations. In contrast, at LC30, peak fecundity (0.2–0.4) was delayed until approximately day 30, indicating a concentration-dependent effect of tetraniliprole on reproductive timing and output. The trends observed in the maternity function (lxmx) mirrored those of mx, further highlighting the generational impact of sublethal exposure. However, no significant deviations in the age-specific survival rate (lx) were observed across treated and control groups in either generation.

Figure 1.

Age-specific survival rate (lx), age-specific fecundity (mx), and age-specific maternity (lxmx) of F1 and F2 generations of Tuta absoluta originating from F0 individuals exposed to tetraniliprole (LC10 and LC30).

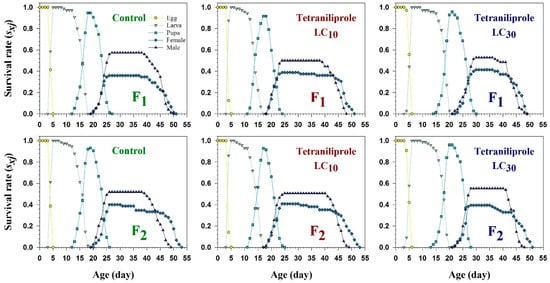

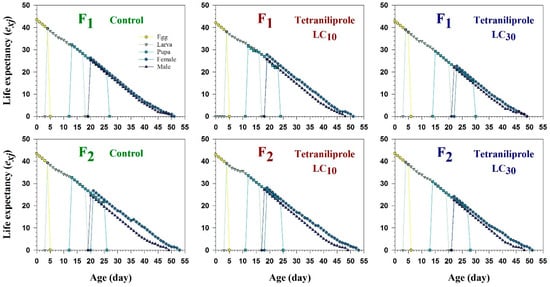

The age-stage-specific survival rate (sxj), representing the probability that an individual egg survives to age x and stage j, showed overlapping trends between treatments and control during immature stages (Figure 2). However, sxj was notably reduced in adult males and females of the F2 generation at both LC10 and LC30. Conversely, larval sxj values were increased under both concentrations, suggesting a stage-specific response to tetraniliprole exposure. The age-stage-specific life expectancy (exj), indicating the expected remaining lifespan of an individual at age x and stage j, also varied with treatment and generation (Figure 3). Female life expectancy under LC10 was 34 days in the F1, declining to 27 days at LC30. In F2, females lived an average of 35 days at LC10, while life expectancy decreased to 31 days at LC30. These values were slightly lower than the control groups, where life expectancies were 33 and 34 days for F1 and F2, respectively.

Figure 2.

Age-specific survival rate (sxj) of F1 and F2 generations of Tuta absoluta originating from F0 individuals exposed to tetraniliprole (LC10 and LC30).

Figure 3.

Age-specific life expectancy (exj) of F1 and F2 generations of Tuta absoluta originating from F0 individuals exposed to tetraniliprole (LC10 and LC30).

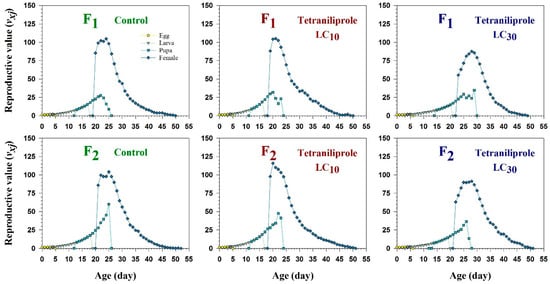

Age-stage-specific reproductive values (vxj), representing the future reproductive potential of individuals at each age and stage, were significantly reduced in LC30-treated females in both generations compared to controls and LC10 treatments (Figure 4). This reduction indicates a transgenerational suppression of reproductive capacity at higher sublethal concentrations.

Figure 4.

Age-specific reproductive rate (vxj) of F1 and F2 generations of Tuta absoluta originating from F0 individuals exposed to tetraniliprole (LC10 and LC30).

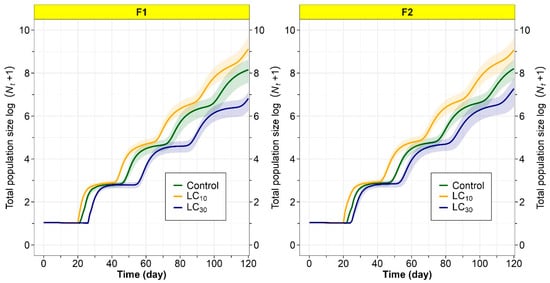

3.6. Population Projection

The population growth of T. absoluta over 120 days (F1 and F2 generations) for the tetraniliprole treatments (LC10, LC30) and the control group, including confidence intervals, is shown in Figure 5. Population sizes were greatest in the F1 and F2 generations after parental exposure to the LC10 dose of tetraniliprole, implying a hormetic effect that enhanced population growth. Conversely, population projections for the F1 and F2 generations following parental exposure to LC30 were lower than those of the control, suggesting a suppressive effect at this concentration (Figure 5). This study reveals the concentration-dependent influence of tetraniliprole on T. absoluta’s population dynamics across multiple generations.

Figure 5.

Total population size log (Nt + 1) of F1 and F2 generations Tuta absoluta originated from F0 individuals exposed to the LC10 and LC30 of tetraniliprole.

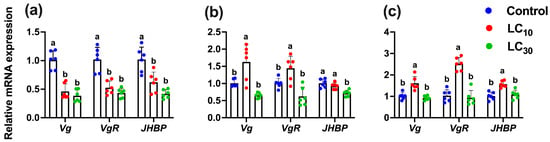

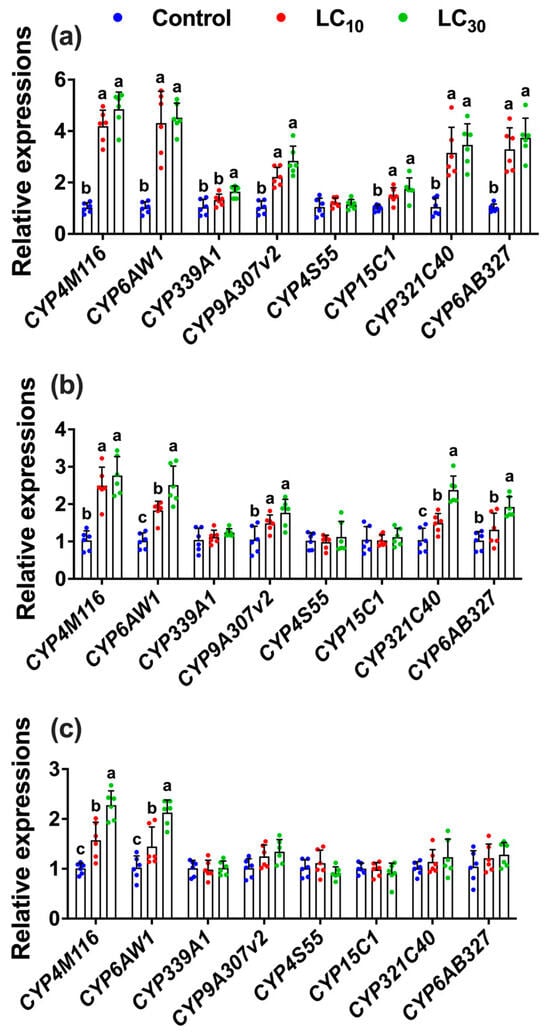

3.7. Transgenerational Effects of Tetraniliprole on Developmental and Resistance Genes

Following the exposure of the parental generation (F0) to sublethal and low-lethal concentrations of tetraniliprole, we analyzed its transgenerational effects on the relative mRNA expression levels of genes linked to development, reproduction, and resistance. These effects were examined in the directly exposed F0 generation as well as in the unexposed progeny generations (F1 and F2) of T. absoluta (Figure 6 and Figure 7). Results showed that the expression levels of Vg, VgR, and JHBP were significantly (Vg, F2,17 = 38.59, p < 0.001; VgR, F2,17 = 27.09, p < 0.001; JHBP, F2,17 = 19.94, p < 0.001) reduced in T. absoluta directly exposed to the LC10 (0.46-, 0.52-, and 0.62-fold) and LC30 (0.38-, 0.43-, and 0.41-fold) of tetraniliprole compared to the control (Figure 6a). In the F1 generation, the Vg and VgR were significantly upregulated by 1.62- and 1.44-fold at LC10 (Vg, F2,17 = 15.55, p < 0.001 and VgR, F2,17 = 14.02, p < 0.001), while no effects were noted for LC30 concentration (Figure 6b). In contrast, the expression level of JHBP was significantly downregulated by 0.71-fold at LC30 (JHBP, F2,17 = 13.02, p < 0.001), while no effects were observed at LC10 compared to the control. The expression levels of these genes were also upregulated by 1.60-, 2.51-, and 1.56-fold in the LC10-treated individuals (Vg, F2,17 = 18.92, p < 0.001; VgR, F2,17 = 49.51, p < 0.001; JHBP, F2,17 = 17.06, p < 0.001), while no effects were found at the LC30-treated group compared to control (Figure 6c).

Figure 6.

The relative mRNA expression level of development and reproduction-related genes (Vg, VgR, and JHBP) in the parental F0 (a) and the progeny F1 (b) and F2 (c) generations of Tuta absoluta after F0 treatment with the LC10 and LC30 of tetraniliprole. The expression level is expressed as the mean (±SE) of the three biological replicates. Letters above the bars represent significant differences at p < 0.05 level using one-way analysis of variance with Tukey’s post hoc test (IBM, SPSS Statistics, Armonk, NY, USA, version 29).

Figure 7.

Expressions of P450 genes in the parental F0 (a) and the progeny F1 (b) and F2 (c) generations of Tuta absoluta after F0 treatment to the LC10 and LC30 of tetraniliprole. The expression level is expressed as the mean (±SE) of the three biological replicates. Letters above the bars represent significant differences at p < 0.05 level using one-way analysis of variance with Tukey’s post hoc test (IBM, SPSS Statistics, Armonk, NY, USA, version 29).

Further, the expression levels of resistance-related cytochrome P450 genes such as CYP4M116 (F2,17 = 87.38, p < 0.001), CYP6AW1 (F2,17 = 23.13, p < 0.001), CYP321C40 (F2,17 = 17.48, p < 0.001), CYP6AB327 (F2,17 = 29.35, p < 0.001), CYP9A307v2 (F2,17 = 28.83, p < 0.001), and CYP15C1 (F2,17 = 8.57, p = 0.003) were all significantly upregulated with fold increases ranging from 1.64- to 4.85-fold in the directly exposed parental generation (F0) to the LC10 and LC30 of tetraniliprole, while CYP339A1 was upregulated only at LC30 as compared to control (Figure 7a). In the F1 generation, the expressions of CYP4M116 (F2,17 = 27.82, p < 0.001), CYP6AW1 (F2,17 = 27.57, p < 0.001), CYP321C40 (F2,17 = 27.62, p < 0.001), CYP6AB327 (F2,17 = 11.40, p < 0.001), and CYP9A307v2 (F2,17 = 7.65, p = 0.005) were upregulated with fold expressions ranging from 1.48 to 2.76 at the LC10 and LC30 of tetraniliprole as compared to control (Figure 7b). However, only two P450 genes, such as CYP4M116 (F2,17 = 32.63, p < 0.001) and CYP6AW1 (F2,17 = 20.63, p < 0.001), were upregulated in the F2 generation with expression ranges from 1.44- to 2.27-fold following parental exposure to the sublethal and low lethal concentrations of tetraniliprole as compared to control (Figure 7c). These results demonstrate that tetraniliprole upregulates resistance-related genes in T. absoluta, suggesting enhanced insecticide breakdown and a potential for resistance evolution following sublethal or low-lethal exposure.

4. Discussion

This study provides valuable insights into the lethal and sublethal effects of tetraniliprole on T. absoluta, a globally important pest of tomato crops. The estimated LC10, LC30, and LC50 values confirm the high toxicity of tetraniliprole to the larval stages of T. absoluta, consistent with its known mode of action as a ryanodine receptor modulator in arthropods [39]. These findings support the potential inclusion of tetraniliprole in integrated pest management (IPM) programs targeting T. absoluta.

Sublethal (LC10) and low lethal (LC30) exposures significantly impacted developmental and reproductive traits in both the directly exposed parental generation (F0) and their offspring (F1 and F2). In the F0 generation, longer larval and pupal stages under sublethal treatments suggest developmental delays caused by physiological stress, likely related to disrupted calcium balance via ryanodine receptor activation [40]. Additionally, earlier research reported that sublethal concentrations of various insecticides, including diamides, caused extended developmental periods in lepidopteran pests [41]. Furthermore, reduced adult lifespan and fecundity in F0 indicate a fitness cost among survivors, consistent with previous studies on arthropods (including Lepidopterans) exposed to diamides and other insecticides [17,18,42].

In subsequent generations, responses varied based on both concentration and generation. At LC10, a pattern of faster development and higher fecundity indicates a hormetic effect, where low-concentration stress can stimulate physiological processes [43,44]. Conversely, exposure to LC30 led to delayed development, decreased fecundity, shorter adult lifespan, and lower reproductive value (vxj), suggesting transgenerational stress effects or possible epigenetic regulation [45].

Life table parameters clearly reflected these effects. At LC10, both the intrinsic rate of increase (r) and the finite rate of increase (λ) were raised, while at LC30, these rates decreased significantly. These patterns are especially important for pest management, as they indicate that sublethal insecticide residues at low concentrations could unintentionally boost population growth, whereas higher sublethal levels may inhibit it [46]. The mean generation time (T) was shorter under LC10, encouraging faster generational turnover, but longer under LC30, which could slow population growth.

Age-stage-specific parameters further supported these findings. Delayed peaks in fecundity, reduced life expectancy (exj), and lower reproductive values (vxj) at LC30 highlight disrupted reproductive strategies [32]. Interestingly, increased oviposition periods and population sizes under LC10 in F1 suggest heightened reproductive effort in response to mild sublethal stress. Sex-specific effects were also prominent. LC30 exposure caused a decline in male longevity, potentially impairing mating success and sperm competition [47]. Conversely, increased male longevity at LC10 may indicate compensatory mechanisms or decreased mating effort under stress conditions. Overall, these results show that while tetraniliprole is very effective at lethal concentrations, its sublethal effects are complex and can either suppress or promote T. absoluta populations depending on the concentration and generation.

Vg and VgR genes act as key molecular indicators of female reproductive capacity in insects, often reflecting fecundity status under environmental and chemical stressors [48]. While many studies have reported a downregulation of these genes in response to insecticidal pressure, this is frequently seen as a sign of impaired reproduction or endocrine disruption [24,25]. Our study, however, shows a different pattern. Specifically, we observed a significant upregulation of Vg and VgR expression in insects exposed to the LC10 concentration of tetraniliprole, indicating a hormetic response. Hormesis, which is a stimulatory effect at low doses of an otherwise inhibitory agent, may be an adaptive strategy where the organism temporarily boosts reproductive output as a response to mild chemical stress. This reproductive boost was even more noticeable in the F2 generation at the LC30 level, where Vg and VgR expression exceeded the levels seen in both F0 and F1. These findings suggest a transgenerational acclimation effect, possibly driven by epigenetic changes or altered endocrine signaling pathways. In addition to reproductive genes, cytochrome P450 monooxygenases (CYPs) are central to insecticide detoxification and have long been linked to resistance development [30,49]. In our study, CYP4M116 expression was significantly upregulated in F0 after tetraniliprole exposure, reflecting a strong metabolic response in the first generation. However, a decrease in expression levels in F1 and F2, although still above control levels, may indicate feedback inhibition, reduced selection pressure, or physiological costs across generations. These patterns highlight the dynamic nature of gene-environment interactions that shape resistance phenotypes over time.

In contrast, CYP6AB327 and CYP6AW1 showed sustained upregulation across LC10 and LC30 treatments and generations, indicating a more consistent and potentially heritable metabolic resistance mechanism. The involvement of these genes aligns with their known roles in detoxifying various insecticides, including spinosad, diamides, and neonicotinoids [50,51]. However, the absence of significant expression in other P450 genes such as CYP4S55, CYP9A307v2, and CYP15C1 highlights that detoxification pathways are gene-specific and selective, likely influenced by the chemical structure of the insecticide, dosage, and exposure duration.

These findings agree with an increasing amount of evidence suggesting that resistance can develop from the activation of common detoxification genes due to the widespread use of chemical insecticides [1,50]. This overlap in metabolic pathways presents a significant risk to sustainable pest management, as it can weaken rotation strategies if cross-resistance genes are not accurately identified and monitored. Overall, our results lay the groundwork for understanding the complex transgenerational effects of tetraniliprole on T. absoluta and their impact on population management. Future research should investigate these dynamics under continuous exposure across multiple generations to better reflect field conditions. Such studies would help determine whether the observed hormetic response persists, diminishes, or increases over time, and how including generational mortality in population growth models might affect the long-term dynamics of pest populations under ongoing insecticide use.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, tetraniliprole shows dual concentration-dependent transgenerational effects on T. absoluta, causing hormesis at LC10 but suppression at LC30. These sublethal effects, driven by changes in gene expression, emphasize a significant risk of population resurgence and should be considered in resistance management strategies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.L., X.L., N.D. and F.U.; visualization, investigation, software, and validation: A.G., H.G., G.M. and F.U.; resources: X.L. and Y.L.; data curation and analysis: A.G., H.G. and F.U.; writing—reviewing and editing: Z.U., G.-P.-P.G., P.P.P., A.G., H.G., G.M., X.L. and F.U.; supervision and project administration: X.L. and Y.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the Zhejiang High-level Talents Special Support Program (2023R5249) and the Key R&D Program of Zhejiang (2024SSYS0105).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with a minor correction to the order of the existing affiliation information. This change does not affect the scientific content of the article.

References

- Wang, M.-H.; Ismoilov, K.; Liu, W.-X.; Bai, M.; Bai, X.-S.; Chen, B.; Chen, H.-L.; Chen, H.-S.; Dong, Y.-C.; Fang, K.; et al. Tuta absoluta management in China: Progress and prospects. Entomol. Gen. 2024, 44, 269–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desneux, N.; Wajnberg, E.; Wyckhuys, K.A.; Burgio, G.; Arpaia, S.; Narváez-Vasquez, C.A.; González-Cabrera, J.; Catalán, R.D.; Tabone, E.; Frandon, J. Biological invasion of European tomato crops by Tuta absoluta: Ecology, geographic expansion and prospects for biological control. J. Pest Sci. 2010, 83, 197–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biondi, A.; Guedes, R.N.C.; Wan, F.H.; Desneux, N. Ecology, worldwide spread, and management of the invasive South American tomato pinworm, Tuta absoluta: Past, present, and future. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2018, 63, 239–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, M.R.; Biondi, A.; Adiga, A.; Guedes, R.N.; Desneux, N. From the Western Palaearctic region to beyond: Tuta absoluta 10 years after invading Europe. J. Pest Sci. 2017, 90, 787–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, P.; Zhang, Y. Research toward enhancing integrated management of Tuta absoluta, an ongoing invasive threat in Afro-Eurasia. Entomol. Gen. 2024, 44, 263–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, M.R.; Béarez, P.; Amiens-Desneux, E.; Ponti, L.; Gutierrez, A.P.; Biondi, A.; Adiga, A.; Desneux, N. Thermal biology of Tuta absoluta: Demographic parameters and facultative diapause. J. Pest Sci. 2021, 94, 829–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponti, L.; Gutierrez, A.P.; de Campos, M.R.; Desneux, N.; Biondi, A.; Neteler, M. Biological invasion risk assessment of Tuta absoluta: Mechanistic versus correlative methods. Biol. Invasions 2021, 23, 3809–3829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desneux, N.; Luna, M.G.; Guillemaud, T.; Urbaneja, A. The invasive South American tomato pinworm, Tuta absoluta, continues to spread in Afro-Eurasia and beyond: The new threat to tomato world production. J. Pest Sci. 2011, 84, 403–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.-X.; Yang, M.; Arnó, J.; Kriticos, D.J.; Desneux, N.; Zalucki, M.P.; Lu, Z. Protected agriculture matters: Year-round persistence of Tuta absoluta in China where it should not. Entomol. Gen. 2024, 44, 279–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.-X.; Ma, R.-X.; Hu, J.; Chen, Y.-P.; Peng, C.; Li, D.-G.; Zhang, J.-T.; Shen, M.-L.; Gui, F.-R. Repellent and insecticidal effects of Rosmarinus officinalis and its volatiles on Tuta absoluta. Entomol. Gen. 2024, 44, 297–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, F.; Guru-Pirasanna-Pandi, G.; Murtaza, G.; Sarangi, S.; Gul, H.; Li, X.; Chavarín-Gómez, L.E.; Ramírez-Romero, R.; Guedes, R.N.C.; Desneux, N. Evolving strategies in agroecosystem pest control: Transitioning from chemical to green management. J. Pest Sci. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sparks, T.C.; Crossthwaite, A.J.; Nauen, R.; Banba, S.; Cordova, D.; Earley, F.; Ebbinghaus-Kintscher, U.; Fujioka, S.; Hirao, A.; Karmon, D.; et al. Insecticides, biologics and nematicides: Updates to IRAC’s mode of action classification-a tool for resistance management. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 2020, 167, 104587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Gao, B.; Qu, C.; Gong, J.; Li, W.; Luo, C.; Wang, R. Resistance monitoring for six insecticides in vegetable field-collected populations of Spodoptera litura from China. Horticulturae 2022, 8, 255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.; Jung, J.W.; Kang, D.H.; Kim, H.K.; Kim, G.H. Evaluation of the insecticidal toxicity of various pesticides for Atractomorpha lata (Orthoptera: Pyrgomorphidae) control. Entomol. Res. 2023, 53, 209–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakil, W.; Kavallieratos, N.G.; Naeem, A.; Gidari, D.L.S.; Boukouvala, M.C.; El-Shafie, H.A. Efficacy of the anthranilic diamide tetraniliprole against four coleopteran pests of stored grains. Crop Prot. 2025, 194, 107200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desneux, N.; Fauvergue, X.; Dechaume-Moncharmont, F.X.; Kerhoas, L.; Ballanger, Y.; Kaiser, L. Diaeretiella rapae limits Myzus persicae populations after applications of deltamethrin in oilseed rape. J. Econ. Entomol. 2005, 98, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Desneux, N.; Decourtye, A.; Delpuech, J.M. The sublethal effects of pesticides on beneficial arthropods. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2007, 52, 81–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guedes, R.N.C.; Berenbaum, M.R.; Biondi, A.; Desneux, N. The side effects of pesticides on non-target arthropods. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, F.; Güncan, A.; Gul, H.; Hafeez, M.; Zhou, S.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Huang, J.; Ghramh, H.A.; Guo, W.; et al. Spinosad-induced intergenerational sublethal effects on Tuta absoluta: Biological traits and related genes expressions. Entomol. Gen. 2024, 44, 395–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, F.; Güncan, A.; Abbas, A.; Gul, H.; Guedes, R.N.C.; Zhang, Z.; Huang, J.; Khan, K.A.; Ghramh, H.A.; Chavarín-Gómez, L.E.; et al. Sublethal effects of neonicotinoids on insect pests. Entomol. Gen. 2024, 44, 1145–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; He, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Dong, R.; Hu, S.; Yang, Z.; Guo, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Xie, W.; Wang, S. Sublethal effects of thiamethoxam on Encarsia formosa: Intergenerational impacts and insights from transcriptomic analysis. Entomol. Gen. 2025, 45, 275–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guedes, R.; Smagghe, G.; Stark, J.; Desneux, N. Pesticide-induced stress in arthropod pests for optimized integrated pest management programs. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2016, 61, 43–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutler, G.C.; Amichot, M.; Benelli, G.; Guedes, R.N.C.; Qu, Y.; Rix, R.R.; Ullah, F.; Desneux, N. Hormesis and insects: Effects and interactions in agroecosystems. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 825, 153899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.; Yang, X.B.; Yang, H.; Long, G.Y.; Jin, D.C. Effects of sublethal concentrations of insecticides on the fecundity of Sogatella furcifera (Hemiptera: Delphacidae) via the regulation of vitellogenin and its receptor. J. Insect Sci. 2020, 20, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zhu, J.; Wang, Q.; Ji, X.; Wang, W.; Huang, W.; Rui, C.; Cui, L. Hormesis effects of sulfoxaflor on Aphis gossypii feeding, growth, reproduction behaviour and the related mechanisms. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 872, 162240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, H.; Güncan, A.; Kavousi, A.; Gharakhani, G.; Atlihan, R.; Özgökçe, M.S.; Shirazi, J.; Amir-Maafi, M.; Maroufpoor, M.; Taghizadeh, R. TWOSEX-MSChart: The key tool for life table research and education. Entomol. Gen. 2022, 42, 845–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, H.; Kavousi, A.; Gharekhani, G.; Atlihan, R.; Salih-Özgökçe, M.; Güncan, A.; Gökçe, A.; Smith, C.L.; Benelli, G.; Guedes, R.N.C.; et al. Advances in theory, data analysis, and application of the age-stage, two-sex life table for demographic research, biological control, and pest management. Entomol. Gen. 2023, 43, 705–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birch, L. The intrinsic rate of natural increase of an insect population. J. Anim. Ecol. 1948, 17, 15–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, H. Life-table analysis incorporating both sexes and variable development rates among individuals. Environ. Entomol. 1988, 17, 26–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, F.; Guru-Pirasanna-Pandi, G.; Gul, H.; Panda, R.M.; Murtaza, G.; Zhang, Z.J.; Huang, J.; Li, X.; Desneux, N.; Lu, Y. Nanocarrier-mediated RNAi of CYP9E2 and CYB5R enhance susceptibility of invasive tomato pest, Tuta absoluta to cyantraniliprole. Front. Plant Sci. 2025, 16, 1573634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livak, K.J.; Schmittgen, T.D. Analysis of Relative Gene Expression Data Using Real-Time Quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT Method. Methods 2001, 25, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, H. TWOSEX-MSChart: A Computer Program for the Age–Stage, Two-Sex Life Table Analysis. Zenodo. 2024. Available online: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7484085 (accessed on 1 April 2024).

- Huang, Y.B.; Chi, H. Age-stage, two-sex life tables of Bactrocera cucurbitae (Coquillett)(Diptera: Tephritidae) with a discussion on the problem of applying female age-specific life tables to insect populations. Insect Sci. 2012, 19, 263–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akca, I.; Ayvaz, T.; Yazici, E.; Smith, C.L.; Chi, H. Demography and population projection of Aphis fabae (Hemiptera: Aphididae): With additional comments on life table research criteria. J. Econ. Entomol. 2015, 108, 1466–1478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polat Akköprü, E.; Atlıhan, R.; Okut, H.; Chi, H. Demographic assessment of plant cultivar resistance to insect pests: A case study of the dusky-veined walnut aphid (Hemiptera: Callaphididae) on five walnut cultivars. J. Econ. Entomol. 2015, 108, 378–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chi, H. TIMING-MSChart: A Computer Program for the Population Projection Based on Age–Stage, Two-Sex Life Table. Zenodo. 2024. Available online: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7482191 (accessed on 1 April 2024).

- Chi, H. Timing of control based on the stage structure of pest populations: A simulation approach. J. Econ. Entomol. 1990, 83, 1143–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.W.; Chi, H.; Smith, C.L. Linking demography and consumption of Henosepilachna vigintioctopunctata (Coleoptera: Coccinellidae) fed on Solanum photeinocarpum (Solanales: Solanaceae): With a new method to project the uncertainty of population growth and consumption. J. Econ. Entomol. 2017, 111, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahm, G.P.; Selby, T.P.; Freudenberger, J.H.; Stevenson, T.M.; Myers, B.J.; Seburyamo, G.; Smith, B.K.; Flexner, L.; Clark, C.E.; Cordova, D. Insecticidal anthranilic diamides: A new class of potent ryanodine receptor activators. Bioorganic Med. Chem. Lett. 2005, 15, 4898–4906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordova, D.; Benner, E.A.; Sacher, M.D.; Rauh, J.J.; Sopa, J.S.; Lahm, G.P.; Selby, T.P.; Stevenson, T.M.; Flexner, L.; Gutteridge, S.; et al. Anthranilic diamides: A new class of insecticides with a novel mode of action, ryanodine receptor activation. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 2006, 84, 196–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- França, S.M.; Breda, M.O.; Barbosa, D.R.; Araujo, A.M.; Guedes, C.A.; Shields, V.D.C. The sublethal effects of insecticides in insects. Biol. Control Pest Vector Insects 2017, 10, 66461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, W.; Yan, Y.; Ma, Y.; Jiang, X.; Deng, K.; Xie, D.; Cheng, Y.; Liu, N.; Zhang, L. Effects of chlorantraniliprole on reproductive and migration-related traits of Spodoptera frugiperda. Entomol. Gen. 2025, 45, 265–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutler, G.C. Insects, insecticides and hormesis: Evidence and considerations for study. Dose-Response 2013, 11, 154–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guedes, R.N.C.; Cutler, G.C. Insecticide-induced hormesis and arthropod pest management. Pest Manag. Sci. 2013, 70, 690–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Babu, S.R.; Dudwal, R. Field efficacy of tetraniliprole 200 SC, a new diamide insecticide molecule against common cutworm, Spodoptera litura in soybean. Indian J. Plant Prot. 2020, 45. [Google Scholar]

- Stark, J.D.; Banks, J.E. Population-level effects of pesticides and other toxicants on arthropods. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2003, 48, 505–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cloyd, R.A.; Bethke, J.A. Impact of neonicotinoid insecticides on natural enemies in greenhouse and interiorscape environments. Pest Manag. Sci. 2011, 67, 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, Q.; Xu, S.; Dong, Y.; Que, Y.; Quan, L.; Chen, B. Characterization of vitellogenin and vitellogenin receptor of Conopomorpha sinensis Bradley and their responses to sublethal concentrations of insecticide. Front. Physiol. 2018, 9, 1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Lu, M.; Han, G.; Du, Y.; Wang, J. Sublethal effects of chlorantraniliprole on development, reproduction and vitellogenin gene (CsVg) expression in the rice stem borer, Chilo suppressalis. Pest Manag. Sci. 2016, 72, 2280–2286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplanoglu, E.; Chapman, P.; Scott, I.M.; Donly, C. Overexpression of a cytochrome P450 and a UDP-glycosyltransferase is associated with imidacloprid resistance in the Colorado potato beetle, Leptinotarsa decemlineata. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 1762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stavrakaki, M.; Ilias, A.; Ioannidis, P.; Vontas, J.; Roditakis, E. Investigating mechanisms associated with emamectin benzoate resistance in the tomato borer Tuta absoluta. J. Pest Sci. 2022, 95, 1163–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).