Abstract

This paper investigates the impact of lubrication and thermal effects on the performance of single-metal seals in roller cone bits, and it establishes the geometric, material, and operating parameter models for the single-metal seal. Based on the theory of statistics, the Greenwood–Williamson (G–W) model is employed to predict the contact stress of micro-protrusions on the sealing pair surface. This study establishes a Thermal Elastohydrodynamic Lubrication (TEHL) coupling model for single-metal seals, which utilizes the deformation matrix method to characterize the microscopic deformation of the sealing interface. The central difference method is applied to solve the oil film thickness and temperature distribution in the axial and film thickness directions of the sealing surface. The results indicate that the sealing zone is predominantly under rough peak contact pressure, operating in a mixed-lubrication state. Oil film thickness negatively correlates with static contact pressure, and seal pressure and pre-compression displacement significantly influence lubrication performance. Experiments validate the numerical simulation results, with a mean relative error of less than 15%, confirming the model’s effectiveness. This study offers a theoretical basis for optimizing single-metal seal design, enhancing the reliability and lifespan of roller cone bits in harsh conditions.

1. Introduction

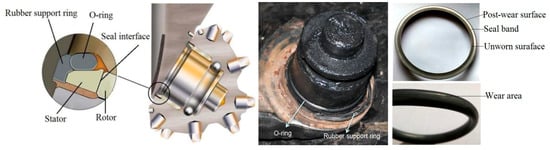

In the oil drilling industry, single-metal seals (SEMS) are widely utilized in roller cone bits due to their remarkable high-temperature tolerance, wear resistance, and ability to withstand vibrations. Roller cone bits, equipped with such SEMS, have a lifespan ranging from 150 to 200 h [1]. However, in the context of deep-well operations, these SEMS encounter complex conditions, including high temperatures, high pressures, and wear-inducing elements in drilling fluids that can compromise the seal’s effectiveness. As the well depth increases, formation pressure escalates, leading to dynamic changes in the contact state and oil film characteristics between the sealing surfaces of the SEMS. These changes can further affect the sealing effectiveness and stability of the seal. The lubrication performance of the SEMS, therefore, warrants a rigorous and comprehensive investigation. Compared to dynamic seals used in conventional industrial production, those applied in drilling tools are primarily designed for extreme conditions, which limits the amount of relevant research available. Hughes in the US produced the SEMS, and later developed the second-generation single-metal seals (SEMS2) [2]. Figure 1 shows the wear condition of seal components, which clearly demonstrates that only the outer seal surface is worn out. The wear of the O-ring is very serious due to the slippage between the O-ring and the stator. The rotating ring and stationary ring in the SEMS2 form a dynamic sealing surface, thereby preventing drilling fluid from invading the seal cavity of the drill bit. Downhole temperature, pressure, and deformation of the sealing ring exert a significant impact on the thermo-elastohydrodynamic lubrication (TEHL) performance of the dynamic sealing surface.

Figure 1.

The structure of the SEMS2 and the wear condition.

Xiong et al. [3] developed a steady-state numerical model for the SEMS, examining the variation patterns of key sealing parameters, such as film thickness, liquid film pressure, and leakage rate. Subsequently, Carre et al. [4] and Grimes et al. [5] conducted a comparative analysis of the structural features and performance differences between the SEMS and SEMS2 based on international drilling cases. Zhang et al. [6,7] combined simulation with experiments to determine the exact parameter values of rubber components used in SEMS2. Furthermore, more scholars have focused on the influence of sealing structure parameters and sealing surface pressure difference on the contact pressure of SEMS2, which provides a theoretical basis for the design of SEMS2 [8,9,10]. Zhang et al. [11] presented a new leakage rate calculation method and validated it against experimental results.

Most research on the oil film performance of metal seals has been concentrated in the field of traditional mechanical seals. Various studies have explored enhancing sealing performance through surface texturing [12,13]. However, this approach tends to increase the leakage rate of the seal. Yang et al. [14] comprehensively analyzed the TEHL performance of mechanical seals by considering the rough surface contact between sealing faces and the viscothermal effects. Salant et al. [15] and Blasbalg et al. [16] proposed a two-phase numerical model for mechanical seals that considers phase change and cavitation. This model predicts the transient response of two-phase seals to axial disturbances. To enhance the reliability of mechanical seals in rocket engines, a mathematical model for hydrodynamic-hydrostatic mechanical seals is proposed, considering the separation mechanism of fluid phase transition and mixed lubrication [17].

Therefore, combining the high-pressure working conditions of roller cone bits during drilling, this paper establishes a TEHL coupling model of SEMS2 under the influence of bilateral fluid pressure, discusses the temperature and pressure distribution of the oil film on the seal face, and finally verifies the numerical simulation through dynamic seal tests under the influence of bilateral fluid pressure. The organization of this paper is as follows: Section 2 introduce the mathematical model of the TEHL coupling problem and the process of calculation. Section 3 presents a numerical analysis of the seal contact pressure distribution and lubrication performance of metal seals using the rubber constitutive parameters. The results are subsequently validated in Section 4 through both numerical simulations and experimental investigations.

2. Mathematical Model

2.1. Geometric Model

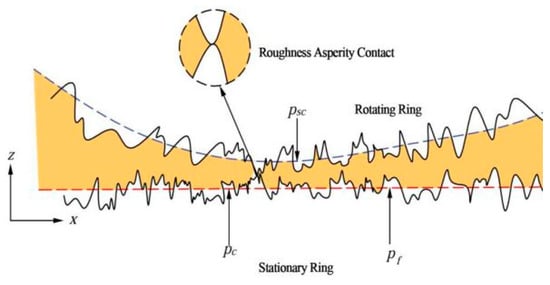

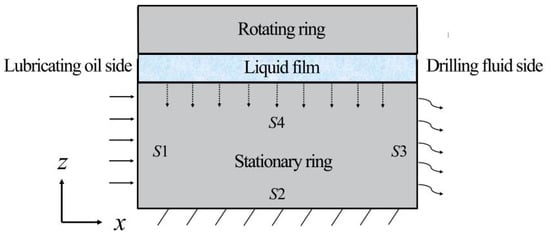

As shown in Figure 1, the rotating ring around the main shaft and the stationary ring form a dynamic sealing surface, which prevents the leakage of lubricating oil and the intrusion of drilling mud into the bearing area. The rubber O-ring and backup ring provide the axial force required for the sealing. The outer side of the single-metal seal is drilling fluid, and the inner side is lubricating oil. Through the pressure balance system, the pressure of the lubricating oil is slightly higher than that of the drilling fluid, thus ensuring that the drilling fluid does not enter the sealed cavity. The ambient pressure difference ΔP (pressure difference in the drilling fluid and lubricating oil) is maintained at approximately 0.3 to 0.7 MPa [18]. For this analysis, a pressure difference of 0.5 MPa is selected. When the SEMS2 works, the sealing area is in equilibrium under the action of three forces: the static contact pressure psc of the seal, the rough peak contact pressure pc, and the oil film pressure pf generated by the fluid dynamic pressure effect, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Microscopic schematic diagram of the main sealing area.

2.2. Fluid Reynolds Equation

Given that surface roughness can affect the dynamic behavior of the lubricating oil film in the sealing gap and considering that both the end face deformation and the flow field between the sealing end faces exhibit axisymmetric distribution, a laminar lubricating oil film model is employed. The fluid is treated as a Newtonian fluid, without considering fluid cavitation and its load effects, as well as ignoring the heat generated by stirring and the heat carried away by fluid leakage. The simplified Reynolds equation in the polar coordinate system is introduced to characterize the lubrication state on the dynamic sealing interface between the rotating ring and the stationary ring [19]. This equation considers the impact of roughness on oil film flow, enabling a more precise evaluation of the lubrication efficiency in the sealing area:

where r represents the length in the radial direction of the sealing ring, h is the nominal film thickness, and μ denotes the liquid film viscosity,

is the pressure flow factor. The effect of liquid film pressure on viscosity is neglected. Instead, the relationship below is used to characterize the influence of temperature changes on liquid film viscosity [3]:

where T0 is the ambient temperature, μ0 is the lubricant viscosity at ambient temperature, and n is the viscosity-temperature coefficient derived from experimental data.

Patir and Cheng established in references [20,21] that the pressure flow factor

depends on the ratio of oil film thickness h to the comprehensive root mean square roughness σ, as well as the roughness peak shape ratio γ. Assuming γ equals one [22,23], the pressure flow factor

can be expressed as follows:

2.3. Finite Element Analysis

2.3.1. Material Model

In the single-metal combination sealing ring, the materials of the metal moving ring and metal stationary ring are hard alloy steel YG8, whose Poisson’s ratio is 0.3, and elastic modulus is 7.1 × 105 MPa. The metal shaft diameter material is alloy steel 20CrNiMo with better wear resistance, and its elastic modulus is ES = 2.1 × 105 MPa, and the Siméon Denis Poisson ratio is 0.3. As a highly elastic polymer material exhibiting triple nonlinearity, incompressibility, and large deformation, fluororubber is employed as the primary constituent for both the O-ring and the rubber support ring. When conducting a multi-physics field coupling numerical simulation of the seal system, the following basic principles should be followed:

- Assume that the rubber material has an isotropic hyperelastic constitutive relationship and meets the condition of volume incompressibility.

- Ensure that the mechanical parameters of the material have thermodynamic stability, and do not consider the gradual decline of material properties during long-term service in the analysis.

- Do not consider the influence of stress relaxation and creep characteristics of rubber materials on the simulation results.

- Ignore the effect of medium temperature changes on the performance of the seal ring.

Rubber is a hyperelastic material with isotropic and incompressible properties, as shown in Table 1. The Mooney-Rivlin constitutive model is used to describe its mechanical properties, with the expression as follows [24]:

where C10 and C01 represent the M-R model parameters. The hardness of the O-ring is 75, with an elastic modulus of 8.74 MPa. The hardness of the rubber support ring is 80, with an elastic modulus of 10.98 MPa. Both have a Poisson’s ratio of 0.499. The values of C10 and C01 are shown in Table 1. I represents the Green–Lagrange strain invariant.

Table 1.

Parameters of rubber materials at different hardness levels.

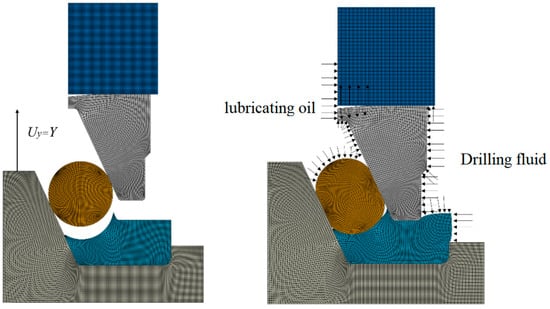

2.3.2. Material Model Simulation Analysis

To assess the performance of single-metal sealed hydrodynamic lubrication, it is necessary to analyze the numerical simulation of the seal and calculate the static contact pressure of the single-metal seal. The numerical simulation of the single-metal seal involves two steps. First, the rotor is fixed, and axial displacement is applied to the metal shaft to simulate the pre-compression of the sealing component. In this setup, the inner surfaces of both the single-metal sealing ring and O-ring experience lubricating oil pressure; conversely, drilling fluid pressure is exerted upon the outer side of the rubber support ring and fixed ring, as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Two load steps for single-metal seal analysis.

2.4. Microscopic Contact Analysis

According to the

theory, the sealing area enters a mixed lubrication state when the oil film thickness falls below three times the equivalent standard deviation of the sealing surfaces, with a certain number of rough peak micro-protrusions in contact. In this case, the contact pressure between these rough peaks cannot be ignored. This paper employs the G–W model based on statistical theory, if the height of the rough peaks on the seal ring surface follows a Gaussian distribution, to estimate the contact pressure pc between the rough peak micro-protrusions of the two contact surfaces in the sealing area [25]:

where η quantifies the micro-asperity distribution density, σ denotes the surface roughness parameter, R is the radius of annular micro-asperities, and the equivalent Young’s modulus E’ is expressed as follows. Considering that the rotating and stationary rings are made of homogeneous materials, the equivalent Young’s modulus E’ can be simplified:

where Es and vs represent the Young’s modulus and Poisson’s ratio of the stationary ring, respectively.

2.5. Microscopic Deformation

It is difficult for finite element analysis to accurately describe the variation law of the oil film on the sealing surface when rubber parts deform in a single-metal seal. This paper examines the flow–solid coupling between the seals and oil film. The deformation matrix method is utilized to account for the effect of the elastomer’s elastic deformation on the oil film thickness. In microscopic deformation analysis, the static oil film thickness, hs, is to determine the nodal film thickness [25]:

where hi is the oil film thickness at node i. The static oil film thickness hs is obtained by substituting the static contact pressure psc into the G–W equation. I represents the deformation matrix.

2.6. Thermal Analysis

During the operation of the sealing pair, heat is generated by the viscous shear of the lubricating oil and the shear friction between the seal rings. Temperature changes cause thermal expansion and deformation of sealing components, affecting lubrication and friction. In thermo-fluid–structure interaction problems, the energy equation is crucial for describing these couplings. The temperature field from the energy equation aids thermal—deformation analysis.

This study uses Stefani and Rebora’s transmembrane averaged energy equation [26]. The average temperature of the liquid film, T, is determined based on a quartic polynomial function distribution, as expressed below:

where a, b, c, d, and e are coefficients for calculating the temperature field distribution T of the oil film.

Considering fluid viscous dissipation, micro-protrusion contact shear friction, and heat transfer between the fluid and the rotating and stationary rings, the average energy equation for the oil film at the sealing interface can be expressed as follows:

where k denotes the thermal conductivity of the oil film, h represents the film thickness, and Tm is the mean oil film temperature, ρ and c stand for the density and specific heat capacity of the lubricant, respectively. um is the average oil film velocity,

denotes the average power dissipation density function. fc represents the friction coefficient, and Pc refers to the oil film pressure. Finally, qB and qJ represent the energy input into the rotating and stationary rings of the single-metal seal, respectively.

In the process of analytical analysis of the average energy equation, referring to and drawing on the theoretical framework constructed by researchers such as Harigaya [27] and Gu [28], this paper proposes a novel approach for establishing the thermal boundary conditions at the inlet and outlet boundaries of the lubricating film.

where q represents the flow rate of the lubricating oil, and the unit of its physical quantity is cm3·s−1. TD and TJ represent the surface temperatures of the stationary ring and the rotating ring, respectively.

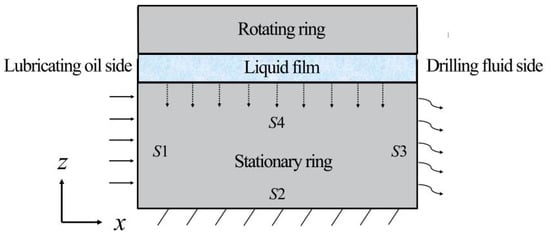

Thermal boundary conditions of the seal ring are shown in Figure 4, a portion of the heat generated by friction in the dynamic seal is transferred to the sealing ring via thermal conduction, resulting in a variation in the sealing ring temperature TS. Based on the actual conditions of this heat transfer model, reasonable simplifications are applied. The region S1 in contact with the lubricant is set as a constant temperature boundary; the lower boundary S2 represents the downhole ambient temperature T0; the right boundary S3 corresponds to the drilling fluid temperature; and the upper boundary S4 represents the oil film region on the sealing surface. The heat flux is denoted as qJ.

Figure 4.

Thermal boundary conditions of the seal ring.

The axial coordinate is defined as

. Furthermore, the coordinates corresponding to the direction of the oil film thickness and the seal ring thickness are designated as

and

, respectively. hp represents the thickness of the seal ring, and kp and kair represent the thermal conductivity coefficient of the seal ring and the thermal convection coefficient of the drilling fluid, respectively.

3. Calculation Process

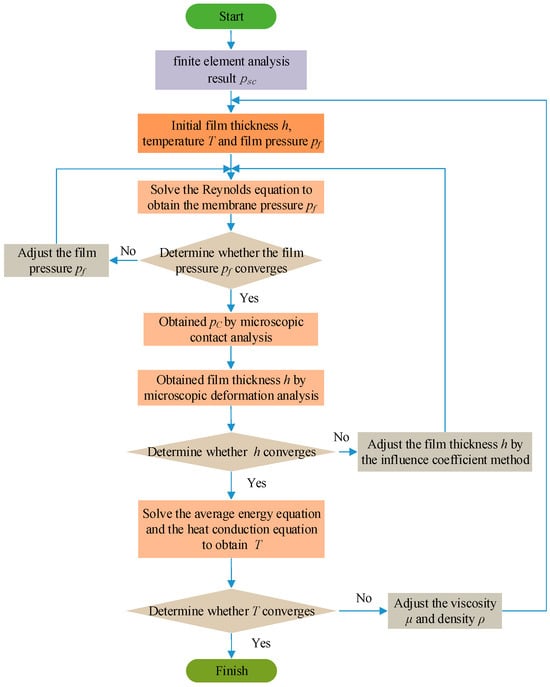

The mixed lubrication model of the single-metal combination seal ring constructed in this paper integrates multiple complex parts, such as finite element analysis, film Reynolds equations, microscopic contact analysis, and microscopic deformation. An iterative algorithm is used for numerical solution. When the film pressure and thickness achieve dynamic balance, the film characteristics of the sealing area are prospectively predicted. The calculation process is shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Numerical calculation process.

4. Results Analysis

4.1. Analysis of Sealing Force Under the Effect of Parameters

The single-metal sealing parameters, analyzed in this paper, are from the 8 1/2 MD517X roller cone bits, with their detailed parameters presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Physical parameters.

To balance sealing performance, contact pressure distribution, and wear risk, a pre-compression displacement of 2.1 mm is selected, as shown in Table 3. The displacement avoids one-sided wear while maintaining good lubrication performance and restricting structural damage due to excessive pre-compression that meets the actual working condition requirements.

Table 3.

Operating Parameters.

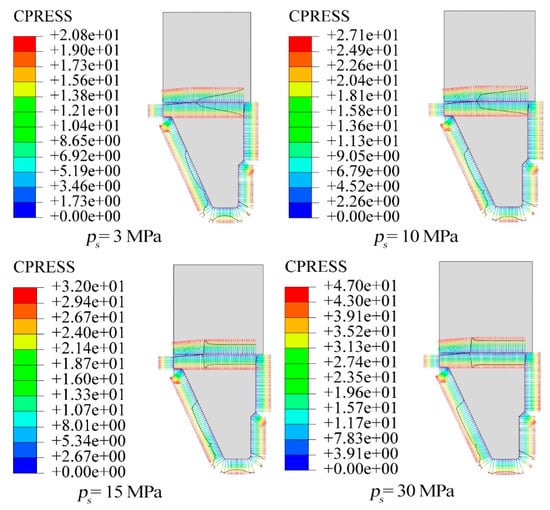

4.1.1. Sealing Pressure

Different sealing pressures affect the lubrication performance and state of the single-metal seal. The loading displacement of the single-metal seal is set to 2.1 mm, and four drilling fluid pressure conditions of 3 MPa, 10 MPa, 15 MPa, and 30 MPa are added. Figure 6 presents the results for the Von-Mises stress and contact pressure of the single-metal seal across different working conditions. It is observed that the contact pressure between the static and dynamic rings transitions through three sequential phases in response to the continuous increase in external drilling fluid pressure.

Figure 6.

Contact pressure of the sealing surface under different sealing pressures.

First, the contact force of the static and dynamic ring contact surface caused by the assembly preload still dominates at 3 MPa. At this time, the high contact pressure on the right side of the sealing surface can effectively prevent the external drilling fluid from intruding into the inside of the sealing surface and prevent particles in the drilling fluid from entering between the sealing surfaces, causing wear of the sealing surface. However, excessive one-sided contact pressure can easily cause one-sided wear of the static and dynamic rings during rotation, destroying the structural integrity of the sealing surface and thereby affecting the sealing performance and reliability of the sealing surface.

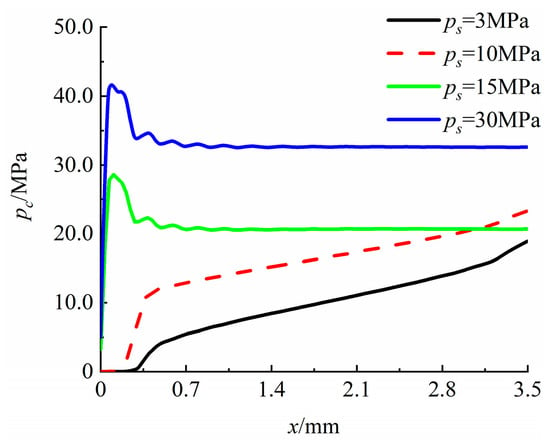

The variation of radial contact pressure on the sealing surface is shown in Figure 7. The contact pressure of the sealing surface is improved when the pressure is 10 MPa compared with that at 3 MPa. The contact pressure on the left side of the contact surface is smaller than that on the right side, the length of the sealing surface is further increased, and the contact pressure of the whole sealing surface tends to be average. When the pressure reaches

, a distinct concentration of the maximum pressure is observed at the left end of the contact surface. resulting in a rapid local pressure increase, whereas a more uniform contact pressure is maintained across the other areas. When the pressure increases to 30 MPa, the maximum contact pressure is located on the left side of the sealing surface. However, due to the increase in internal and external hydraulic pressures, the overall contact pressure of the sealing surface is higher than that at 15 MPa.

Figure 7.

Change of radial contact pressure on the sealing surface.

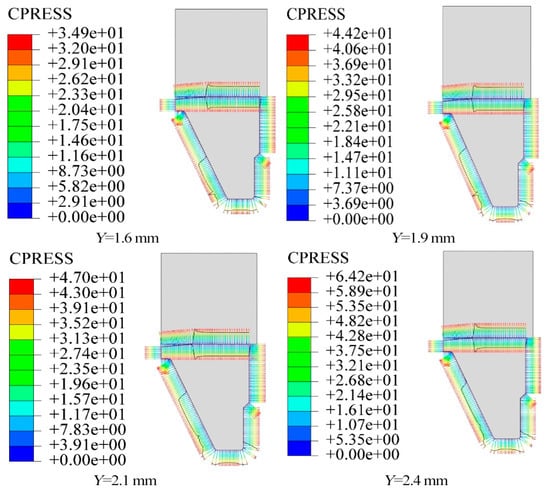

4.1.2. Pre-Compression Displacement

When single-metal seal rings are manufactured and installed, a certain amount of pre-compression is applied to make the components fit together and ensure the sealing performance of the single-metal seal. The influence of pre-compression amount under 30 MPa pressure on the performance of a single-metal seal is shown in Figure 8. The results indicate a positive correlation between the contact pressure on the main contact surface and the compression displacement, although the overall distribution profile stays consistent. Notably, the main sealing surface exhibits a maximum contact pressure of

when the pre-compression displacement is set to

. The maximum contact pressure is located at the left end of the main contact surface, at the connection point between the stationary ring opening and the sealing surface. When the pre-compression displacement is 1.6 mm, the pressure on the seal surface is only 34.9 MPa. If the pre-compression displacement is further reduced, the main sealing surface can be easily flushed open by the fluid, leading to direct failure of the sealing surface.

Figure 8.

Contact pressure of the main sealing surface under different pre-compression displacements.

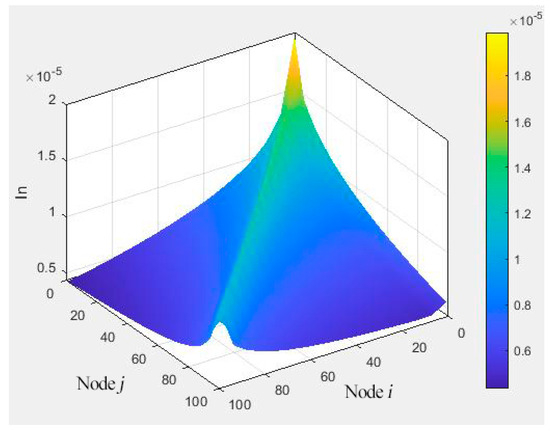

4.2. Deformation Matrix

The lubricating oil film thickness in the sealed region is extremely small, typically on the micron scale. Thus, it is challenging to accurately characterize the evolution law of the oil film thickness via finite element analysis. In accordance with the elastic deformation theory, the deformation within this region is assumed to be linearly proportional to the applied load, and the deformation matrix method is employed to calculate the displacement of a single node. The deformation matrix is illustrated in Figure 9.

Figure 9.

Deformation matrix.

4.3. Lubrication Performance of Single-Metal Seals

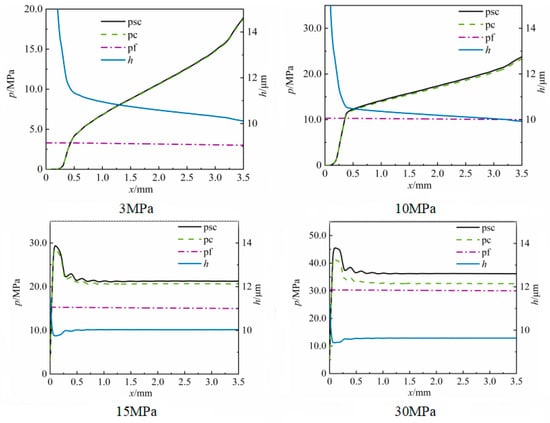

Figure 10 shows the distribution of static contact pressure psc, roughness peak contact pressure pc, fluid pressure pf, and oil film thickness h in the sealing area under four working conditions. It can be seen from the distribution that the roughness peak contact pressure in the sealing area is much higher than the oil film pressure; that is, the roughness peak contact pressure dominates in the contact pressure of the sealing area, and therefore, the friction force is greatly affected by the shear stress of the roughness peak contact.

Figure 10.

Oil film characteristics at design points.

From the observation of the oil film thickness distribution, it can be concluded that the oil film thickness is lower than three times the equivalent roughness of the two surfaces, thereby placing the sealing area in a mixed lubrication state, characterized by a negative correlation between the oil film thickness distribution and the static contact pressure. Under medium and low-pressure conditions, the roughness peak contact pressure pc and the static contact pressure psc, both increase and gradually rise, and finally experience a more rapid increase at the right end of the sealing area. The high-pressure distribution feature on the right side can effectively prevent the external drilling fluid from intruding into the single-metal seal surface.

Under high pressure, the roughness peak contact pressure pc and the static contact pressure psc show a trend of being high on the left side, then gradually fluctuating and decreasing, and finally gradually stabilizing at the right end. In terms of the distribution of fluid pressure pf, due to the existence of the single-metal lubricating oil replenishment system, the lubricating oil pressure is always kept 0.3 MPa higher than the external drilling fluid pressure, and the internal and external pressure difference is small, so the fluid pressure of the sealing surface shows a gentle downward trend from left to right.

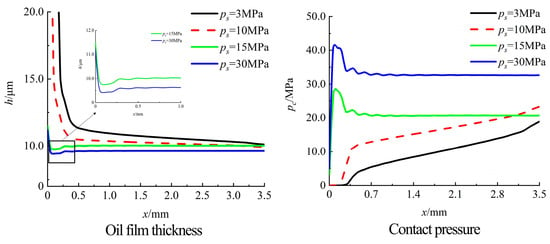

The response of the oil film thickness to varying drilling fluid environmental pressures is depicted in Figure 11. The O-ring and rubber support ring are subjected to the combined action of internal lubricating oil and external drilling fluid, resulting in significant deformation, which further compresses the stationary ring and makes the static and dynamic rings fit more closely. Therefore, overall, the oil film thickness decreases with the increase in drilling fluid pressure, which is conducive to reducing the leakage of lubricating oil.

Figure 11.

Distribution of oil film thickness and contact pressure under different sealing pressures.

Under medium and low-pressure conditions, since there is no contact pressure on the seal interface inside, the oil film thickness increases sharply. In the contact area, the oil film thickness decreases from left to right due to the increase in contact pressure, which is conducive to reducing the contact between lubricating oil and external drilling fluid and reducing leakage. Under high-pressure conditions, the oil film thickness decreases first and then slowly increases from left to right, with the minimum value appearing at the maximum contact pressure.

Moderately increasing the medium load can effectively suppress fluid leakage and optimize sealing performance. However, when its value exceeds the critical threshold, it causes nonlinear growth in friction power consumption, which may induce surface damage in the moving pair and failure of the sealing function. In the design of the sealing system, it is necessary to reasonably balance the sealing pressure to ensure effective prevention of leakage, reduce friction loss, and extend the service life of the sealing components.

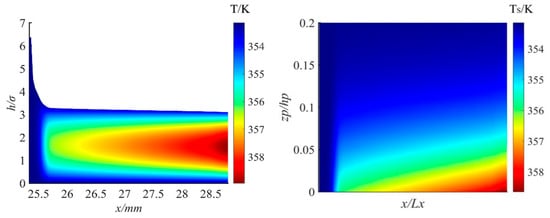

4.4. Thermal Effects on Sealing Performance

The temperature distribution characteristics of the oil film and seal ring in the sealing area are shown in Figure 12. When the rotational speed n is 200 r/min and the sealing pressure ps is 10 MPa. Figure 12 shows the temperature distribution of the stationary ring, wherein the thickness of the seal ring is defined as

, while the length of the contact area is designated as

, and in the coordinate scale, x/Lx represents the dimensionless axial length, and zp/hp represents the dimensionless length in the thickness zp direction of the seal ring.

Figure 12.

The temperature field of the oil film on the sealing interface and the seal ring.

Figure 12 (left) shows the temperature distribution of the oil film on the sealing surface, with temperatures higher on the outer side than on the inner side; the outer side can reach up to 358 K. Meanwhile, the contact pressure on the outer side of the sealing surface is greater than on the inner side, which is largely consistent with the temperature distribution, mainly because higher contact pressure increases frictional heating. Figure 12 (right) shows the temperature distribution of the sealing ring. In the mixed lubrication state, the roughness peak contact pressure in the sealing area becomes the main load-bearing mechanism. Heat accumulated at the minimum film thickness is primarily conducted to the seal ring, thereby inducing a non-uniform temperature rise on the sliding surface.

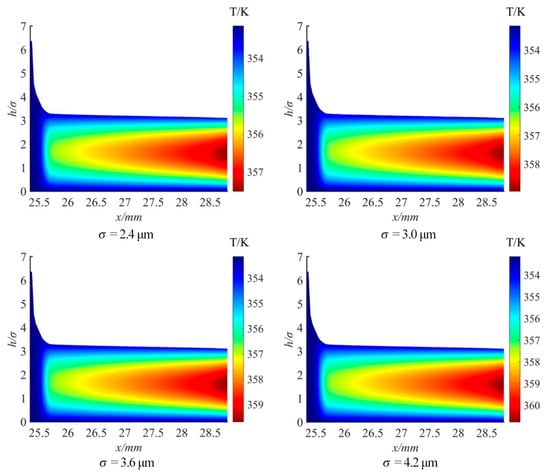

Figure 13 shows the variation in oil film temperature distribution with the roughness. As can be seen from the right-side ordinate of Figure 13, the magnitude of liquid film temperature rise is extremely small with the increase in surface roughness. When the surface roughness of the sealing interface increased from 2.4 to 4.2 μm, the oil film temperature rose by only 3 K. This is because an increase in roughness further increases friction, causing the temperature of the oil film on the sealing surface to gradually rise.

Figure 13.

Impact of different roughness conditions on the oil film temperature distribution.

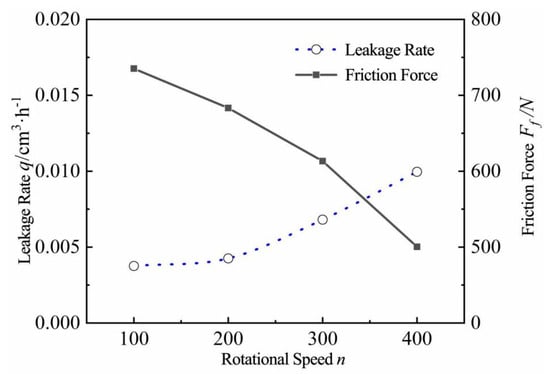

4.5. Sealing Performance Characteristics Under Varying Rotational Speeds

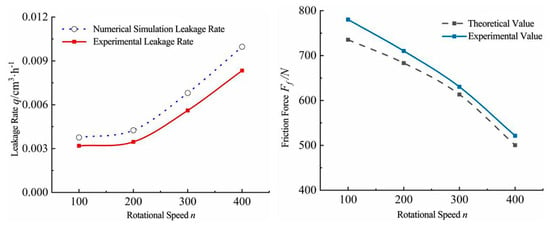

As shown in Figure 14, the leakage rate of the single-metal seal between the static and dynamic rings gradually increases with the increase in the rotational speed, and the increase becomes more pronounced at high rotational speeds. Conversely, the increase in rotational speed enhances the fluid dynamic pressure effect, which helps increase the film thickness and reduce the contact pressure. Consequently, this combined mechanism leads to a decrease in the friction force. Therefore, under low-pressure conditions, appropriately increasing the rotational speed of the drill bit can maintain a reasonable leakage rate while keeping the friction force within a smaller range, thereby reducing the risk of wear failure.

Figure 14.

Dynamic sealing performance under different rotational speeds at 10 MPa.

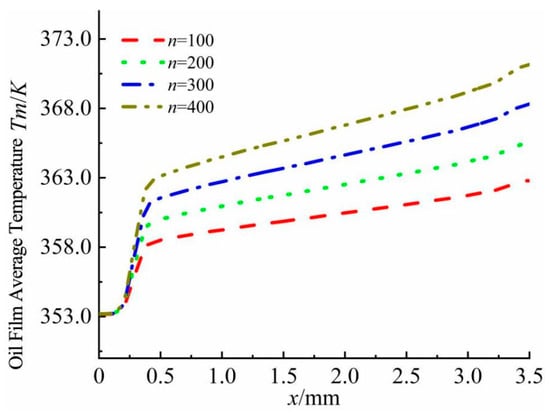

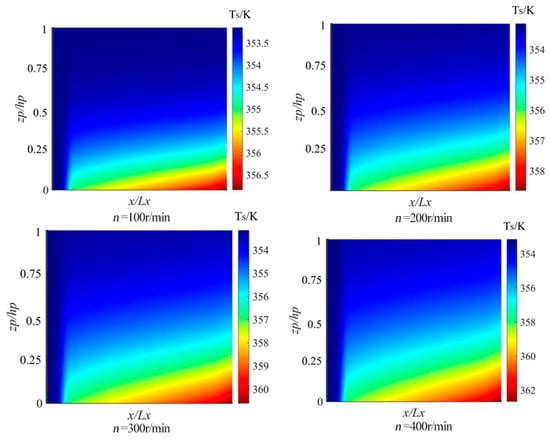

Figure 15 shows the oil film temperature distribution at different rotational speeds. The average temperature of the oil film shows a unique dynamic change pattern at different rotational speeds. Specifically, a substantial elevation in the average temperature of the oil film is induced by viscous shear, which results from the enhanced fluid dynamic pressure effect as the rotational speed gradually increases. This temperature rise leads to a decrease in film viscosity, weakening the fluid dynamic support, increasing the actual contact between roughness peaks on the sealing surface, and ultimately having a negative impact on lubrication performance, causing it to deteriorate.

Figure 15.

Oil film temperature distribution at different rotational speeds.

Figure 16 shows the close relationship between the temperature distribution of the seal ring and the rotational speed. Combined with the static contact pressure results presented in Figure 7, it can be observed that the maximum contact pressure occurs at the outer edge of the sealing interface. Consequently, the frictional heat generated at the outer edge is significantly higher than that at other positions on the sealing interface, which is also confirmed by the temperature distribution shown in Figure 16. When the speed reaches 400 r/min, the maximum temperature rise of the seal ring can reach 9 K. This temperature rise increases the temperature difference between the inner and outer diameters of the sealing surface, causing stress changes and increasing the possibility of wear failure.

Figure 16.

Influence of rotational speeds on the temperature distribution of the seal ring.

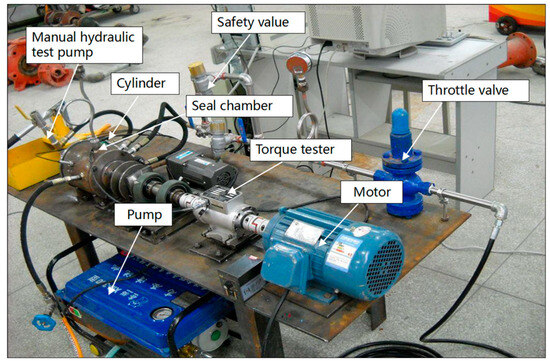

5. Experimental Verification

To verify the analysis results, a seal test rig shown in Figure 17 was set up to evaluate the performance of the single-metal seal ring with a radial thickness of 3.53 mm and a 50 mm rotating shaft. During the experiment, lubricating oil No. 20 was used, and a series of operations was carried out within the sealing pressure range of 0 MPa to 15 MPa. The pressure value was monitored in real-time with a precision pressure gauge, and the pressure changes in the chamber were controlled by a hand pump. The rotational speed of the rotating shaft was controlled by the motor, covering the entire range of 0 to 600 r/min. The other key material parameters in the experiment are detailed in Table 4 for reference.

Table 4.

Experimental parameters.

Figure 17.

Schematic of a seal tester.

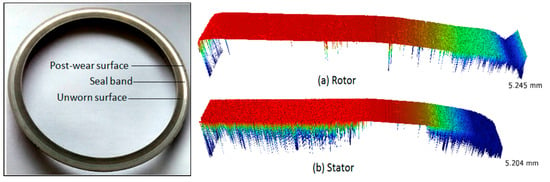

5.1. Contact Pressure Distribution Verification

The wear depth of the sealing face can be obtained by the Contour GT-K, as shown in Figure 18. When the drilling fluid pressure is relatively low, the external contact stress is greater than the internal contact stress, indicating that the outer surface is more prone to wear during the initial drilling process.

Figure 18.

Wear condition of the sealing face.

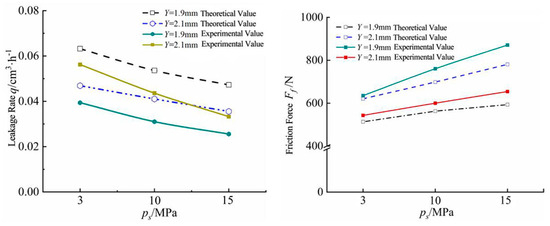

5.2. Seal Lubrication Performance Verification

Two key measurement tasks were carried out in the experimental stage of this study, namely, measuring friction torque and evaluating leakage rate. By setting different pre-compression displacements and speeds, the sealing performance of the toothed seal ring combination seal ring was studied. The experimental results were compared with the numerical simulation results to verify the accuracy of the numerical simulation method. The results are shown in Figure 19 and Figure 20.

Figure 19.

Comparison curves of leakage rate and friction force under different sealing pressures.

Figure 20.

Comparison curves of leakage rate and friction force at different speeds.

The above figures show that the average relative error between the calculation and experimental results is maintained within the 15% threshold, verifying the validity of the numerical model. The primary source of error between the experimental and theoretical results is mainly attributed to the fact that in the experiment, the single-metal seal is pressurized by fluid on both sides. The lubricant leakage was determined based on the product of the piston displacement (measured by a displacement sensor) and the piston diameter. Due to the unavoidable measurement errors associated with the sensor, this calculation method resulted in a certain discrepancy between the experimental data and the numerical simulation results.

The experimental results are consistent with the trend of the numerical analysis. As the preload displacement increases, the frictional resistance shows an increasing trend, while the fluid leakage decreases. In contrast to the preload displacement, the rotational speed exhibits opposite trends with respect to both the leakage rate and the frictional resistance.

6. Conclusions

This paper conducts a numerical simulation on the single-metal seal under the dual-sided action of drilling fluid and lubricating oil, using the pressure penetration method. Furthermore, a thermal elastohydrodynamic coupling analysis model for the single-metal seal is established, and the numerical simulation results are validated through experiments. Simulation results show that the oil film thickness of the single-metal sealing main sealing area is less than 3σ, which is in the mixed lubrication state, and the contact pressure of the rough peak bears most of the load. Increasing the rotational speed can increase the fluid dynamic pressure effect on the sealing surface and improve the lubrication characteristics, and the thickness of the liquid film increases accordingly. The film thickness at the maximum normal contact pressure is the smallest, and the friction heat due to the shear of the micro convex body is also the largest. This location, therefore, coincides with the maximum temperatures for both the oil film and the seal ring. Regarding the pressure distribution under medium and low-pressure conditions, the drilling fluid side exhibits the highest contact pressure, while under higher sealing pressure, the highest contact pressure is located at the lubricating oil side.

Furthermore, considering the influence of rubber stress relaxation on single-metal seal performance will further refine the calculation model for single-metal seals.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W.M.; software, Y.Z.; validation, W.M.; formal analysis, Y.Z.; investigation, Y.Z.; resources, W.M.; data curation, H.W.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.Z.; writing—review and editing, L.Y.; visualization, H.W.; supervision, H.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

If readers need the original dataset, please contact the author via email at “dream5568@126.com”.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors Weidong Meng, Haijuan Wang and Hai Ma were employed by the company SINOPEC Henan Oilfield Branch Company. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Ma, Y.; Yuan, Z.; Ni, Y.; Meng, X.; Peng, X. Performance prediction and multi-objective optimization of metal seals in roller cone bits. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2021, 208, 109316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denney, D. Slimhole technology maximizes middle east horizontal-drilling programs. J. Pet. Technol. 2005, 57, 58–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, S.; Salant, R.F. A numerical model of a rock bit bearing seal. Tribol. Trans. 2000, 43, 542–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carre, L.; McCoy, R.; Wilson, L.; Drilling, C.; Cockerham, J.; Grimes, B.; Anderson, M.; Pardo, N. Application of new generationlarge roller-cone bits reduces drilling costs in eastern Venezuela. In Proceedings of the SPE Latin American and Caribbean Petroleum Engineering, Buenos Aires, Argentina, 25–28 March 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Grimes, B.; Kirkpatrick, B. Step change in performance: Upgraded bit technology significantly improves drilling economics in GOM moto plications. In Proceedings of the SPE Annual Technical Conference and Exhibition, San Antonio, TX, USA, 24–27 September 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, B.; Chen, J.; Liu, Z.; Li, Q.; Xiong, H. Research on the finite Element Model of Single Metal Floating Seal. China Pet. Mach. 2011, 39, 1–3+18+92. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, B.; Chen, J.; Liu, Z. Improvement of the Single metal Floating Seal Structure of the Cone bit SEMS2. China Pet. Mach. 2010, 38, 47. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Liu, Z.; Meng, X.; Yang, P. Structural Optimization of Contact Rotating Ring Mechanical Seals. Lubr. Seal. 2016, 41, 77–81. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Y.; Huang, Z.; Tan, L.; Ma, Y.; Qiu, C.; Zhang, F.; Yuan, Y.; Sun, C.; Guo, L. Cone bit bearing seal failure analysis based on the finite element analysis. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2014, 45, 292–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Luo, Y. Container Design and Contact Research of Single Metal Seal. J. Mech. Des. Res. 2013, 29, 132–134+137. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Chang, X.; Fu, Y.; Wu, Q. Analysis and Experimental Research on Single Metal Seal Contact under Drilling Conditions. China Mech. Eng. 2018, 29, 262–266. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, J.; Chen, X.; Li, M.; Wang, T.; Shi, L. Effect of Surface Texture Bottom Configuration on the Performance of Liquid—Lubricated Mechanical Seals. J. Anhui Univ. Technol. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 2023, 40, 144–150. [Google Scholar]

- Ji, J. Research on Design and Manufacturing Mechanism of Surface Structure Morphology of Mechanical Seal Ring. Master’s Thesis, Jiangsu University, Zhenjiang, China, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, X.; Meng, X.; Peng, X.; Wang, Y. A TEHD lubrication analysis of surface textured mechanical seals. Tribology 2018, 38, 204–212. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Salant, R.F.; Blasbalg, D.A. Dynamic behavior of two-phase mechanical seals. Tribol. Trans. 1991, 34, 122–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blasbalg, D.A.; Salant, R.F. Numerical study of two-phase mechanical seal stability. Tribol. Trans. 1995, 38, 791–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Zhang, G.; Chen, Y.; Zhao, W.; Luo, X.; Li, Y. Separation mechanism and gas-liquid mixed lubrication model of cryogenic reusable mechanical seal. Results Eng. 2026, 29, 108783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, X.D.; Chang, X.P.; Wu, Q. Wear morphology analysis and structural optimization of cone bit bearing seals. Ind. Lubr. Tribol. 2018, 70, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, Y. Study on Thermo-fluid-solid Coupling of Single-metal Seal of Rock Bit and Multi-objective Optimization Design. Master’s Thesis, Zhejiang University of Technology, Hangzhou, China, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Patir, N.; Cheng, H.S. An Average Flow Model for Determining Effects of Three-Dimensional Roughness on Partial Hydrodynamic Lubrication. J. Tribol. Trans. ASME 1978, 100, 12–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patir, N.; Cheng, H.S. Application of Average Flow Model to Lubrication Between Rough Sliding Surfaces. J. Tribol. 1979, 101, 220–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B. Theory and Experimental Study of EHL Lubrication for Hydraulic Linear Reciprocating Seals. Ph.D. Thesis, Zhejiang University of Technology, Hangzhou, China, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, J. Numerical Simulation Study on Static and Dynamic Performance of Spindle Composite Sealing Structure at Different Temperatures. Master’s Thesis, Harbin Institute of Technology, Harbin, China, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Lou, J.; Zhu, S.; Tang, S. Inverse Calculation of Material Parameters in the M-R Model of Elastomer Finite Element. Noise Vib. Control 2012, 32, 29–33. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, M.; Xie, J. Finite element analysis of large deformation of rubber parts under compression. J. North. Jiao Tong Univ. 2001, 25, 76–79. [Google Scholar]

- Stefani, F.; Rebora, A. Steadily loaded journal bearings: Quasi-3D mass-energy-conserving analysis. Tribol. Int. 2009, 42, 448–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harigaya, Y.; Suzuki, M.; Takiguchi, M. Analysis of Oil Film Thickness on a Piston Ring of Diesel Engine: Effect of Oil Film Temperature. J. Eng. Gas Turbines Power 2003, 125, 596–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, C.X.; Meng, X.H.; Xie, Y.B.; Fan, J. A thermal mixed lubrication model to study the textured ring/liner conjunction. Tribol. Int. 2016, 101, 178–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.