Abstract

Existing research on the linear rolling guide has predominantly focused on performance under ideal conditions or isolated error types, while systematic studies concerning multi-error coupling mechanisms and their impact on internal contact parameters remain limited. To address this, a comprehensive static model based on Hertz contact theory is proposed that simultaneously incorporates ball diameter, raceway radius, and raceway curvature center distance errors. This model is validated using finite element analysis (FEA) in ABAQUS, and the numerical results verify the feasibility and effectiveness of the proposed analytical model. Analysis of single, combined, and random errors indicates that geometric errors significantly influence vertical stiffness, load distribution, and critical load-carrying capacity. For example, as the ball diameter error varies from −2.5 to 2.5 μm, the vertical stiffness increases by a factor of 3.8, while a representative negative error combination reduces the critical load by nearly 40%. Additionally, random error analysis reveals that larger manufacturing tolerance ranges lead to increased fluctuation in ball contact forces, raising performance uncertainty. These findings establish the proposed model as a theoretical foundation for the precision design and load-bearing assessment of linear rolling guides under static conditions.

1. Introduction

As core functional components providing load-bearing and motion guidance within transmission systems, linear rolling guides are extensively utilized in high-end equipment—such as high-precision computer numerical control (CNC) machine tools and aerospace systems—owing to their low friction, high precision, and robust load-carrying capacity [1]. However, in practical service conditions, manufacturing processes inevitably introduce geometric errors. These errors alter the initial contact state between the balls and raceways, thereby degrading mechanical performance, particularly load-carrying capacity and motion accuracy. Consequently, it is of vital importance to accurately characterize the internal mechanisms by which geometric errors influence load-bearing performance and to establish a static mechanical model capable of reflecting the coupling effects of multiple geometric errors. This is essential for enhancing the load-carrying capacity and overall service performance of linear rolling guides.

Foundational work by Shimizu [2] analyzed static stiffness without considering contact angle variations. Jeong et al. [3] later introduced a computationally efficient spring-based equivalent stiffness model, which showed strong experimental agreement. Subsequent studies refined these approaches; for instance, Dadalau et al. [4] highlighted difficulties in determining equivalent spring stiffness and proposed a more realistic component-oriented modeling approach. Further research leveraged Hertz contact theory and finite element methods. Sun et al. [5] investigated the influence of preload and static load on the static characteristics of a guide system using Hertz contact theory, though they considered only the normal stiffness of the guide. Ohta et al. [6] modeled the carriage and rail as flexible bodies. Zou et al. [7] streamlined the analytical process, and Tong et al. [8] and Cheng et al. [9] adopted sliced modeling techniques to reduce computational cost—though often at the expense of inter-slice interactions. Ma et al. [10] and Chen et al. [11] modeled the carriage deformation as a classical cantilever beam, thus avoiding iterative finite element computations. Research also extended to the influence of other parameters and complex loading conditions on the performance of linear rolling guides, with Shaw et al. [12] and Hung et al. [1] studying stiffness and stability under preload variation, and Olaru et al. [13] and Mahdi et al. [14] analyzing effects of load, lubricant viscosity, and speed on friction. Under complex loading conditions, Rahmani and Bleicher [15,16] experimentally evaluated multi-directional contact stiffness and geometric accuracy effects, whereas Yang et al. [17] developed a hybrid Hertz model for combined loads, and Ye et al. [18] further advanced this line of inquiry by formulating a five-degree-of-freedom model incorporating ball precision errors.

Recently, studies have increasingly incorporated geometric errors. Zhen et al. [19] examined the influence of random ball size deviations on contact stress, load distribution, and fatigue life in ball screw systems, offering valuable insights for error analysis in linear rolling guides. Wang et al. [20] analyzed how different arrangements of off-sized balls affect contact stress distribution and stiffness, revealing that random ball size deviations can actually improve the stiffness and service life of linear rolling guides. Yu et al. [21] investigated the influence of rail geometric profile errors on friction fluctuations. Majda et al. [22] focused on investigating how guideway geometric errors manifest as machine motion errors through experimental measurements and revealed the influence of structural deformation on error characteristics and the effectiveness of error compensation. Ni et al. [23] established error transfer functions to quantify the average effect of geometric errors. Yali et al. [24] treated uncertain geometric errors as equivalent to elastic deformation, thereby revealing how error distribution patterns influence system stiffness. Tong et al. [25] developed an integrated model that accounts for raceway shape and roughness errors, analyzing the nonlinear interaction between external loads, preload, and carriage displacement. Yi et al. [26] proposed a relational model based on Hertz contact theory, connecting raceway curvature center distance errors with static stiffness and friction. Liu et al. [27,28] modeled multiple geometric errors—such as raceway curvature center distance and installation error—as equivalent to ball interference, and derived corresponding static load distribution and stiffness models, while also investigating the impact of random ball size errors on the load distribution of linear rolling guides. These models were validated using a simplified cantilever beam representation of the carriage skirt and linear strain principles, although this equivalence method remains debatable.

Currently, research on the mechanical characteristics of linear rolling guides typically assumes an idealized uniform distribution of contact loads—neglecting the impact of geometric errors during manufacturing—or focuses on the effects of a single error type, leading to significant deviations between theoretical results and actual working conditions. Some studies simply equate geometric errors to equivalent ball interference (pre-compression), thereby overlooking the profound influence of errors on the internal contact parameters of the ball–raceway interface. In fact, multi-source geometric errors within the guide do not exist in isolation but collectively shape the static and dynamic characteristics through complex nonlinear coupling. However, existing research on modeling this error-driven force–deformation coupling mechanism remains incomplete. A systematic analytical framework for the concurrent mechanisms of multiple geometric errors and their impact on internal contact parameters is still lacking. Furthermore, the distribution characteristics of contact forces under random error combinations remain insufficiently elucidated and require deeper investigation. Therefore, investigating the multi-error coupling mechanism is of significant theoretical value for improving the service performance of the guide system and the entire machine tool.

To address the gaps in existing research on the static characteristics of linear rolling guides, this study proposes a comprehensive static model based on Hertz contact theory that simultaneously incorporates ball diameter, raceway radius, and raceway curvature center distance errors into a unified analytical framework. The model systematically quantifies the multi-error coupling mechanism and its impact on internal contact parameters and load distribution. The validity of the proposed model is confirmed using finite element analysis (FEA) in ABAQUS. Furthermore, the study investigates the variations in vertical stiffness, deformation, and contact force distribution under single errors, positive-negative error combinations, and random error distributions.

2. Static Characteristic Analysis of Linear Rolling Guide

2.1. Static Model Under Ideal Conditions

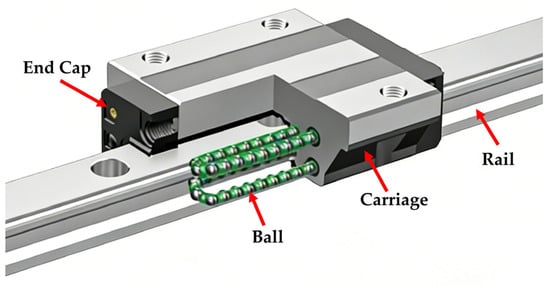

Figure 1 illustrates the typical structure of a linear rolling guide, which primarily consists of a carriage, a rail, and rolling elements. Additionally, the static model of the linear rolling guide is developed based on the following assumptions:

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of the linear rolling guide.

- (1)

- Contact deformations between the balls and the raceways (of both the carriage and the rail) are strictly within the elastic range;

- (2)

- The raceway curvature centers and the ball center are aligned on the same line;

- (3)

- Although dimensional errors exist in ball diameters, the balls are assumed to maintain a perfectly spherical shape.

The elastic deformation

of the ball and raceway under a normal load

is given by the Hertz contact formula:

where

is the Hertz contact coefficient,

is the coefficient related to the elliptic eccentricity

,

and

are the Poisson’s ratio of the two materials,

and

are their elastic moduli,

is the sum of curvatures,

is the ball diameter,

is the raceway radius,

is the principal curvature.

By using balls with a diameter slightly larger than the nominal diameter, an initial interference is established at the ball–raceway interface, thereby generating an internal preload even in the absence of an external load. Different preload levels correspond to specific magnitudes of initial interference, the values of which can be found in the manufacturer’s technical manual. This preload eliminates internal clearance and increases the guide’s stiffness. Assuming ideal manufacturing and installation, the preload is uniformly distributed. In the initial preloaded state, an initial center distance

and initial contact angle

exist between the ball and raceway. The initial curvature, center distance of the carriage and rail raceways can be expressed as follows:

where

and

represent the ratios of the curvature radius of the carriage and the rail to the ball radius, respectively, and

is the nominal ball diameter.

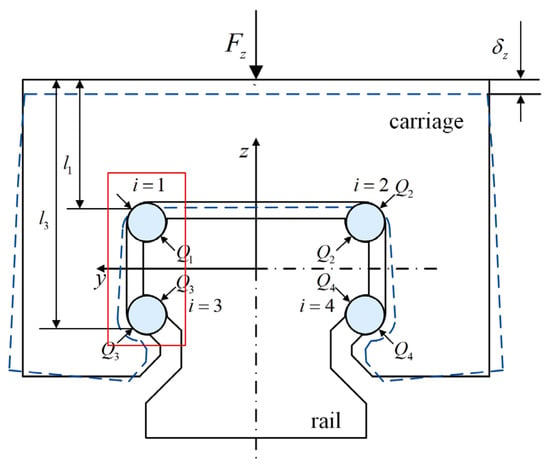

Figure 2 illustrates the cross-sectional deformation of the linear rolling guide under vertical loading and defines the global coordinate system required for the analytical model. The black solid lines represent the initial state before loading, while the blue dashed lines indicate the state after loading. The red box highlights the specific contact area, an enlarged view of which is presented in Figure 3a. When a vertical load

acts on the carriage, a relative displacement

occurs between the carriage and the rail along the load direction, accompanied by carriage skirt deformations

and

. This relative displacement alters the geometric relationship between the balls and raceways, resulting in changes to the raceway curvature center distance and the loaded contact angle under the vertical load, which consequently modifies the ball deformation.

Figure 2.

Cross-section of Linear Rolling Guide.

Figure 3.

Variation in Raceway Curvature Center Distance: (a) Position of ball’s center and raceway’s centers; (b) Without Error; (c) With Error.

Based on the geometry in Figure 3a,b, the curvature center distance between the j-th ball in the i row and the raceway after loading can be expressed as follows:

The contact angle of the j-th ball in the i row after loading can be expressed as

The carriage skirt deformations,

and

, can be expressed, respectively, by the following equations:

The Hertz contact deformation of the ball after loading can be expressed as

The relationship between the ball contact load and the contact deformation can be determined based on Hertz contact theory. Therefore, the total ball deformation

is given by the following equation:

When a vertical load is applied to the linear rolling guide, the balls and raceways elastically deform, generating contact forces. To maintain the equilibrium of the linear rolling guide system, the sum of the vertical components from all ball contact forces must balance the external vertical load

. The force balance condition in the vertical direction is

where

is the vertical force,

is the normal contact force of the j-th ball in the i row,

is the contact angle of the j-th ball in the i row, and n is the number of balls.

As the vertical load increases, the load distribution among the balls changes significantly. The contact force on the lower row of balls, which is opposite to the load direction, continuously decreases to zero. This load is referred to as the critical load. Under these conditions, the force equilibrium equation becomes

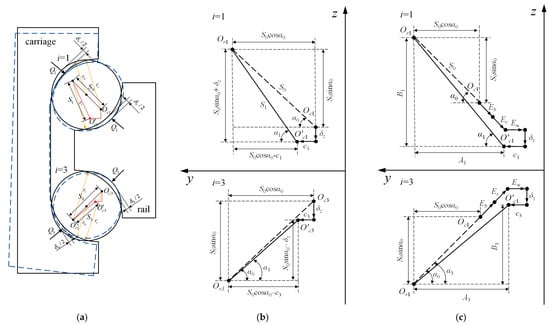

2.2. Static Model Considering Geometric Error

In practice, manufacturing and assembly inevitably introduce deviations in a linear rolling guide, such as in ball diameter, raceway radius, and raceway curvature center distance. These geometric errors alter the ball deformations and contact force distribution, ultimately affecting the guide’s mechanical characteristics. Figure 4 shows the influence of these errors on the raceway curvature center distance, where the raceway radius errors of the carriage and the rail are

and

, respectively, the ball diameter error is

, and the raceway curvature center distance errors of the carriage and rail raceways are

and

, respectively.

Figure 4.

Schematic Diagram of Errors: (a) Ball Diameter Error; (b) Raceway Radius Error; (c) Raceway Curvature Center Distance Error.

When accounting for errors, the actual deformation of a ball depends on both the external load and the initial geometric deviations. The raceway radius error is consolidated into parameter

, and the raceway curvature center distance errors are consolidated into parameter

. According to Figure 3c, the raceway curvature center distance for a guide under both comprehensive errors and an external load is given by the following geometric relationship:

The contact angle of the ball can be accordingly modified as follows:

Accordingly, the Hertz contact deformation of the ball after loading can be modified as follows:

Using the modified raceway curvature center distance and the ball deformation, the contact force on each ball is calculated with the Hertz contact formula. Similarly, the load on each ball is determined by solving the equilibrium equation:

Similarly, when the vertical load exceeds the critical load, the force equilibrium equation is

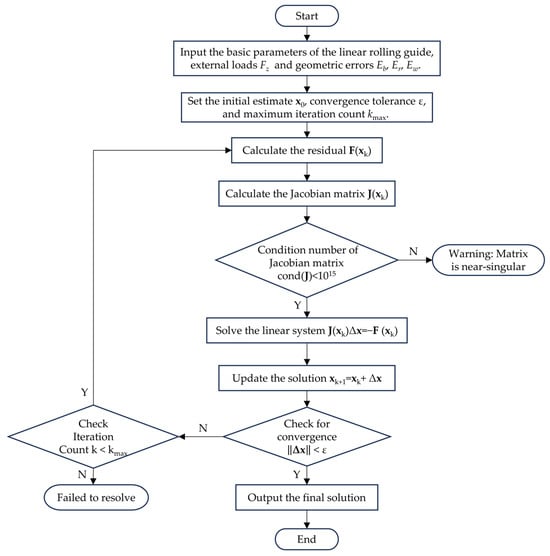

By combining Equation (5) and Equations (10)–(16), key parameters such as contact forces and deformations can be determined. The solution is obtained in MATLAB (R2024b) environment using a Newton–Raphson iterative algorithm. The detailed steps are illustrated in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Flow chart for numerical solution of an equation.

3. Finite Element Analysis

3.1. Materials and Methods

Taking the THK HSR-30R linear rolling guide as an example, this system features four rows of raceways and an initial contact angle of 45°. Within this assembly, the carriage, rail, end caps, and other components form a closed ball circulation path. By enabling balls to circulate within the rail raceways, the sliding friction between the carriage and the rail is converted into rolling friction, thereby achieving high-precision, low-resistance linear motion. To ensure consistency and comparability between analytical predictions and numerical results, the material properties and geometric parameters presented in this section serve as the unified input parameters for both theoretical modeling and the finite element analysis (FEA). As shown in Table 1, the balls, carriage, and rail are all made of GCr15 bearing steel. Its specific mechanical constants, such as the elastic modulus and Poisson’s ratio, are applied consistently across all calculations.

Table 1.

Parameters of the linear rolling guide used in numerical calculation.

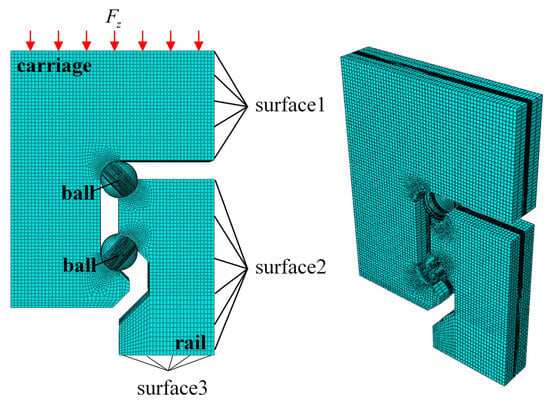

3.2. FEA Model Development and Simulation Procedures

To validate the theoretical model, a finite element analysis (FEA) model of the linear rolling guide was established in ABAQUS 2022 (Figure 6). Focusing on the static characteristics of the load-bearing zone, non-essential components such as end caps and internal seals were omitted to minimize computational expense. Furthermore, assuming uniform ball distribution within the raceway, structural symmetry and uniform load sharing among the 13 segments were leveraged to analyze only a symmetric half of a single segment. This approach streamlined the meshing process and significantly accelerated the solution.

Figure 6.

The finite element analysis (FEA) Model.

In practical operation, the rail is secured to the machine bed by bolts; therefore, as shown in Figure 6, a fixed boundary condition was assigned to the bottom surface of the rail (Surface 3). Symmetry constraints were applied to the symmetry planes of the carriage and rail (Surface 1 and Surface 2), and the vertical load was equivalent to a uniform pressure applied to the top surface of the carriage. The contact between the balls and raceways was defined using the “surface-to-surface contact” property. Tangential behavior was governed by the penalty method with a friction coefficient of 0.002, while normal behavior was modeled using “hard contact.” Preload was simulated via an interference fit between the balls and raceways. Within the “contact interference” option in ABAQUS, the initial interference was gradually removed during the first analysis step to establish a stable preloaded state. In this section, a medium preload level (12 μm) was adopted for both the analytical and FEA calculations. To balance computational accuracy and efficiency, the model primarily employed eight-node linear hexahedral reduced-integration elements (C3D8R), which exhibit superior performance in resisting shear locking when calculating contact pressure distributions. A small number of wedge elements (C3D6) were utilized in irregular transition regions. To verify mesh convergence, contact region mesh sizes of 0.1 mm, 0.05 mm, and 0.025 mm were tested. The results indicated that the fluctuation in maximum contact stress was less than 1.8% when the mesh was refined from 0.05 mm to 0.025 mm; thus, 0.05 mm was determined as the optimal mesh size.

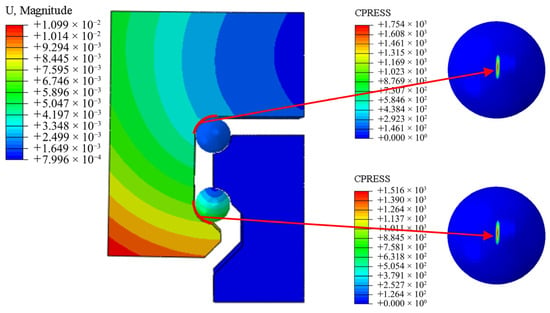

Figure 7 shows the resulting strain cloud diagram for the carriage and the contact stress cloud diagrams for the ball rows under a 1000 N vertical load. With an appropriate scaling factor, the carriage exhibits noticeable outward skirt deformation on both sides. The maximum contact stress is 1753 MPa for the upper ball row and 1516 MPa for the lower ball row, occurring at the center of the elliptical contact areas. The higher stress on the upper row confirms that it bears the primary load.

Figure 7.

Displacement contour of the carriage and contact stress on the ball rows.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Consistency Analysis Between the Ideal Model and Simulation

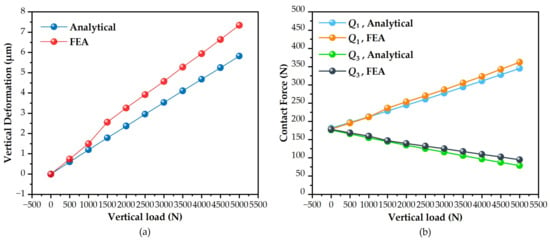

The accuracy of the theoretical model is validated by comparing its predictions for vertical deformation and ball contact forces with FEA results under a 12 μm preload, with vertical loads ranging from 0 to 5000 N. As illustrated in Figure 8, the FEA results are utilized only for this initial consistency check; all subsequent investigations in the following sections rely on the analytical model to explore the effects of various geometric errors.

Figure 8.

Comparison of Analytical and FEA Results: (a) Vertical Deformation; (b) Contact Load.

Figure 8a displays the vertical deformation as a function of the vertical load. The analytical and FEA results exhibit consistent variation trends across the entire load range. For instance, at 2000 N, the theoretical model predicts a deformation of 2.34 μm, while the FEA result is 3.26 μm. At the maximum load of 5000 N, the values are 5.82 μm and 7.35 μm, respectively. This discrepancy primarily arises from the analytical model’s simplification of the carriage’s complex cross-section as an equivalent cantilever beam and its omission of rail flexibility. In contrast, the FEA model accounts for the comprehensive multi-directional compliance of both the carriage and the rail, leading to slightly higher predicted deformation values. Although the FEA results are consistently slightly higher, the overall trend is well-captured. Previous studies [5,6] have similarly noted that analytical models often involve inherent discrepancies in stiffness prediction due to structural simplifications. However, given that the deviations remain within an acceptable engineering margin, the proposed model is deemed reasonable and reliable for subsequent analysis.

Figure 8b compares the normal contact forces of the upper and lower rows of steel balls. At 2000 N, the theoretical and FEA contact forces are 244.65 N and 253.59 N for the upper row, and 134.87 N and 139.26 N for the lower row. At 5000 N, the theoretical and FEA contact forces are 345.23 N and 362.13 N for the upper row, and 79 N and 94 N for the lower row. The results confirm that the upper row’s contact force increases with the vertical load, while the lower row’s force decreases. These results fully demonstrate the strong agreement between the analytical predictions and the FEA simulations.

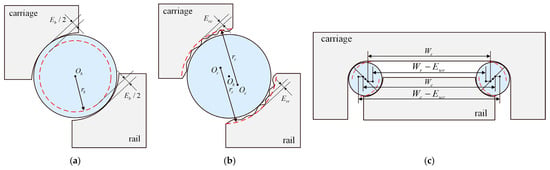

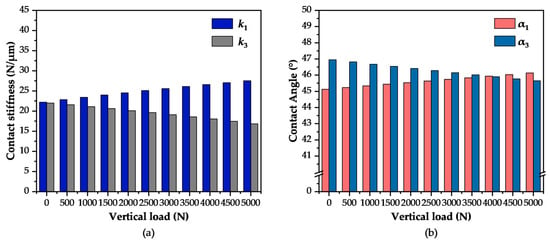

The internal parameter variations predicted by the theoretical model confirm its physical consistency. Figure 9a shows that as the load increases from 0 to 5000 N, the contact stiffness of the upper row of balls rises from 22.22 N/μm to 27.52 N/μm, while that of the lower row decreases from 22.00 N/μm to 16.84 N/μm. This trend is consistent with the principles of contact mechanics, where a higher contact force produces a stiffer contact zone, directly correlating with the force distribution shown in Figure 9b. The contact angles in Figure 9b also show physically reasonable changes: the upper row angle increases slightly from 45.12° to 46.13°, while the lower row angle decreases from 46.95° to 45.64°. These shifts reflect the geometric realignment of the balls and raceways under load.

Figure 9.

In the case of no error: (a) Contact Stiffness; (b) Contact Angle.

4.2. Influence of Single Geometric Error on Static Performance

This section examines the influence of individual geometric errors on the mechanical characteristics of a linear rolling guide by analyzing the independent variation of each error within a specified range under a 1000 N vertical load. According to the mechanical design manual [29], the manufacturing accuracy of balls is shown in Table 2. Furthermore, the variation ranges for the other two types of errors were consistently determined at the same order of magnitude based on the manual’s specifications to facilitate a standardized comparative analysis of their relative impacts on system performance.

Table 2.

Ball’s dimension error with different accuracy (unit μm).

4.2.1. Ball Diameter Error

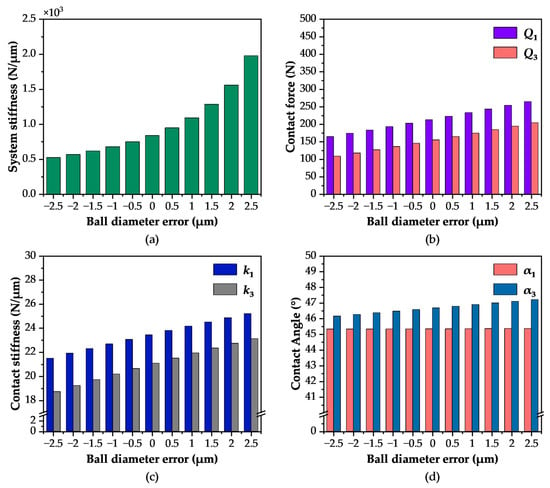

Ball diameter error significantly affects system stiffness. As shown in Figure 10a, the vertical system stiffness increases sharply from 524.08 N/μm to 1978.95 N/μm as the ball diameter error

varies from −2.5 μm to 2.5 μm. This substantial increase results from the greater initial interference between balls and raceways due to a positive error, which raises the internal preload. According to Hertzian contact theory, this heightened preload strengthens the contact stiffness, thereby increasing the overall system stiffness.

Figure 10.

Influence of Ball Diameter Error on Contact Characteristics: (a) Vertical Stiffness; (b) Contact Load; (c) Contact Stiffness; (d) Contact Angle.

Consistent with this mechanism, as shown in Figure 10b,c, the contact forces and contact stiffness of both ball rows increase synchronously with the error. At an error of 2.5 μm, the contact forces for the upper and lower rows rise to 264.69 N and 204.24 N, and their contact stiffness values increase to 25.88 N/μm and 23.02 N/μm, respectively. This occurs because an increase in ball diameter directly reduces the initial clearance between the ball and the raceway, resulting in a larger initial interference. Consequently, the Hertzian contact stiffness enters a non-linear growth regime, which explains why micron-scale manufacturing errors can trigger substantial fluctuations in internal forces. In contrast, the contact angles change minimally (Figure 10d). The upper row contact angle

remains stable at around 45°, and the lower row contact angle only slightly increases from 46.17° to 47.21°. This indicates that ball diameter error primarily influences the load-bearing state by altering the initial interference and contact deformation, not by significantly changing the geometric contact angle.

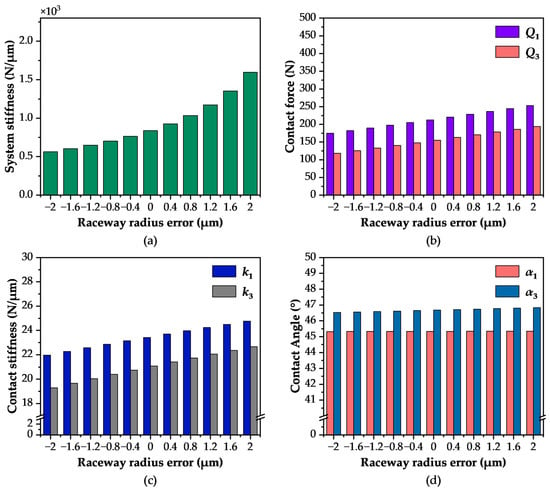

4.2.2. Raceway Radius Error

The raceway radius error influences system performance similarly to ball diameter error, but through a different pathway. The raceway radius error governs the initial preload by regulating the clearance between the ball and the raceway, as well as influencing the Hertzian contact characteristics. As shown in Figure 11a, the system stiffness increases non-linearly, rising from approximately 564.27 N/μm at

= −2 μm to about 1597.16 N/μm at

= 2 μm.

Figure 11.

Influence of Raceway Radius Error on Contact Characteristics: (a) Vertical Stiffness; (b) Contact Load; (c) Contact Stiffness; (d) Contact Angle.

The contact forces and stiffness for both ball rows increase synchronously with the error (Figure 11b,c), with the upper row consistently exhibiting higher magnitudes than the lower row. The contact angles, however, follow a different trend (Figure 11d). While the upper row angle remains largely stable around 45.3°, the lower row angle increases more noticeably from 46.53° to 46.83°.

The results indicate that excessive geometric errors significantly amplify contact forces, potentially shortening the guide’s life, whereas negative errors lead to inadequate vertical stiffness and reduced load capacity. These findings emphasize the necessity of controlling manufacturing tolerances within an optimal range to ensure both the performance and reliability of linear rolling guides.

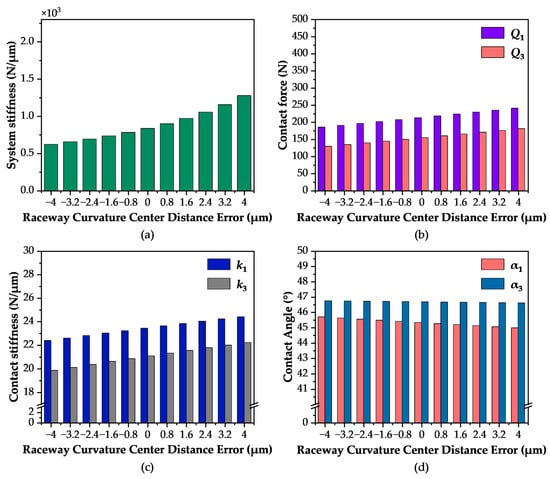

4.2.3. Raceway Curvature Center Distance Error

The raceway curvature center distance error governs stiffness variation by modulating the effective fit clearance and thus the preload. As shown in Figure 12a, a positive ω shifts the raceway curvature centerline closer to the ball center, reducing the effective clearance and increasing preload. Consequently, system stiffness rises sharply from 623.81 N/μm at

= −4 μm to 1279.96 N/μm at

= 4 μm.

Figure 12.

Influence of Raceway Curvature and Center Distance Error on Contact Characteristics: (a) Vertical Stiffness; (b) Contact Load; (c) Contact Stiffness; (d) Contact Angle.

Accordingly, the contact forces and stiffness for both ball rows increase synchronously with

(Figure 12b,c), with the upper row force consistently greater than that of the lower row. This error induces a unique variation pattern in the contact angles (Figure 12d): as

increases, the upper row angle decreases from 45.70° to 44.98°, whereas the lower row angle decreases only slightly from 46.75° to 46.61°. This difference arises because a positive error shifts the ball–raceway contact point, which reduces the contact angle. While this occurs, carriage deformation creates an opposing tendency for the lower row angle to increase. These two effects partially offset each other in the lower row, resulting in a much smaller net angle decrease compared to the upper row.

4.3. Analysis of Error Coupling Effects

4.3.1. Typical Error Combinations

The coupled effect of multiple geometric errors was evaluated using two representative combinations: a negative set

) to degrade performance, and a positive set

) to enhance it. These represent scenarios where errors either degrade performance or may induce compensatory effects.

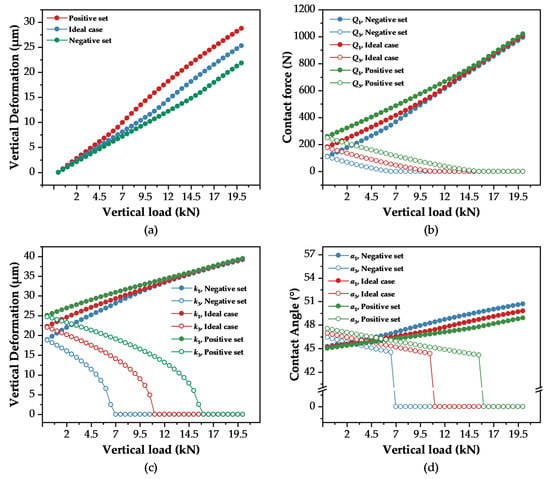

As shown in Figure 13a, at 20 kN, deformations for the negative error, error-free, and positive error conditions are 28.77 μm, 25.32 μm, and 21.85 μm, respectively, indicating that negative errors reduce system stiffness while positive errors enhance it. The critical load is lowest under negative errors (6.56 kN), followed by the error-free (10.84 kN) and positive-error (15.59 kN) conditions. Exceeding this critical load causes the lower ball row to unload, causing a sharp rise in vertical deformation and a drop in system stiffness. Thus, negative errors cause premature disengagement of the lower balls, reducing the guide’s load-bearing capacity. This is consistent with the trend of stiffness hysteresis in linear rolling guides experimentally measured by Krampert et al. [30].

Figure 13.

Influence of Typical Error Combinations on Contact Characteristics: (a) Vertical Deformation; (b) Contact Load; (c) Contact Stiffness; (d) Contact Angle.

As shown in Figure 13b, under negative errors, the contact forces are lower than in the error-free case, while positive errors lead to higher forces due to the corresponding reduction or increase in initial preload. After the critical load is reached, the lower-row contact force drops to zero, and the external load is fully carried by the upper row. Beyond this point, the influence of errors diminishes, and the upper-row force is governed primarily by the external load. The contact stiffness, closely linked to contact force through a nonlinear Hertzian relationship, mirrors the force trend as shown in Figure 13c. When Q3 drops to zero, k3 also decreases sharply to zero, confirming that error-induced contact loss directly reduces guide stiffness. Contact angle variation is shown in Figure 13d. After the critical load, α3 drops to zero due to disengagement, and α1 stabilizes with minimal subsequent change.

4.3.2. Random Error Combinations

In practice, geometric errors often coexist randomly in linear rolling guides. This section analyzes how random error combinations affect the fluctuation and distribution of ball contact forces.

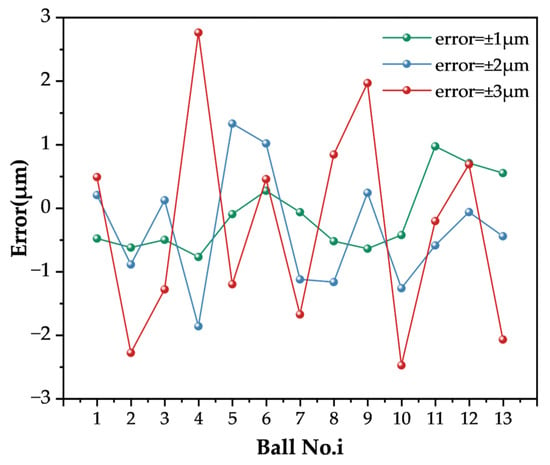

To investigate the influence of random errors on load distribution, raceway curvature center distance and radius errors were held constant, with only ball diameter varied randomly. Figure 14 displays three sets of random ball diameter error curves with different amplitudes, simulating manufacturing deviations. Ball errors were generated in MATLAB using the random function

,

, and

. This study assumes that balls in the upper and lower rows with the same serial number have identical errors.

Figure 14.

Ball error distribution.

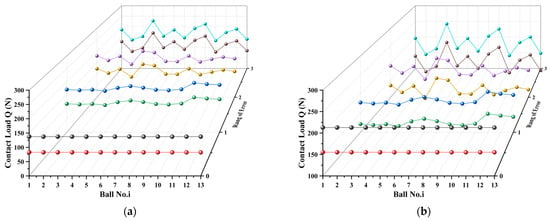

Figure 15a,b show the load distribution for both ball rows under a 1000 N vertical load with 8 μm and 12 μm preloads. For the upper row at 8 μm preload, the contact forces under ±1, ±2, and ±3 μm errors range within [250.44 N, 289.40 N], [228.76 N, 308.13 N], and [231.41 N, 313.22 N], respectively. At 12 μm preload, the corresponding ranges are [170.73 N, 205.64 N], [151.53 N, 222.58 N], and [153.87 N, 227.19 N]. These results indicate that ball diameter errors cause load fluctuations, while increased preload raises the initial contact forces, thereby increasing the overall ball contact loads.

Figure 15.

Influence of Different Preload Levels on Contact Load Fluctuation: (a) Preload 8 μm; (b) Preload 12 μm.

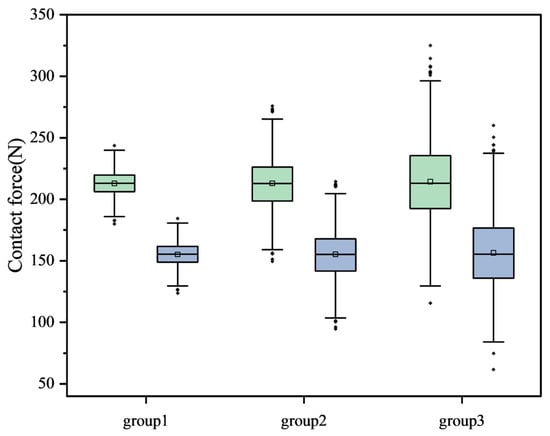

To evaluate the coupling effects of stochastic errors, the manufacturing errors of the raceway curvature center distance, raceway radius, and ball diameter are modeled as independent random variables following a normal distribution N (0,

). Based on the 3

manufacturing principles, design tolerances of ±1 μm, ±2 μm, and ±3 μm are converted into standard deviations of

= 0.333 μm,

= 0.667 μm,

= 1 μm, respectively, representing three precision levels (Groups 1–3). For each level, a Monte Carlo simulation with N = 1000 iterations is performed. In each iteration, the contact forces (Q1, Q3) are numerically solved using a Newton–Raphson algorithm.

Figure 16 shows the influence of random error ranges on contact force distribution. At the low error level (0.333 μm), the compact box and distinct median indicate concentrated contact forces and stable performance. As the error level increases to 1 μm, the box widens and whiskers lengthen, showing an expanded fluctuation range. The maximum contact forces for the upper row (Q1) under the three error levels are 243.69 N, 275.78 N, and 324.98 N, respectively. Such high forces may cause local stress concentration or premature failure in practice.

Figure 16.

Box Plots of Load Distribution under Different Error Levels.

As shown in Table 3, the coefficient of variation (CV) for Q1 increases from ~4.66% (low error) to ~14.43% (high error), a rise of 209.66%. For the lower row (Q3), the CV increases from ~6.07% to ~18.74%, a rise of 208.73%. This confirms that higher error levels substantially amplify contact force fluctuations and uncertainty, which aligns with the increased dispersion in the box plots. The P5–P95 range for Q1 widens from [195.72, 228.51] N to [165.18, 265.73] N, and for Q3 from [138.94, 170.07] N to [109.67, 205.06] N. These ranges define the potential contact force fluctuation with 90% confidence, providing a critical reference for engineering design and safety assessment.

Table 3.

Summary of Statistical Indicators.

5. Conclusions

This study developed a static model that comprehensively incorporates errors in ball diameter, raceway radius, and raceway curvature center distance. The model was used to systematically analyze the effects of individual, coupled, and random errors on system performance. The main conclusions are as follows:

- (1)

- In linear rolling guides, negative geometric errors in ball diameter, raceway radius, or curvature center distance reduce preload; this degradation significantly compromises vertical system stiffness, contact stiffness, and contact force, while also substantially lowering the critical load. This leads to premature disengagement and compromises the guide’s overall load-bearing capacity. Conversely, positive errors enhance stiffness and critical load by increasing preload, thus improving system stability; however, the resulting elevated contact forces may accelerate fatigue and impair precision, necessitating a careful balance in design and accuracy control.

- (2)

- Typical negative error combinations, which reduce preload, substantially lower the critical load for the lower ball row. This leads to premature disengagement and reduces the overall load-bearing capacity of the guide. Positive error combinations, in contrast, raise the critical load and enhance system stability under vertical loading.

- (3)

- Increasing the preload level can partially mitigate performance degradation caused by errors. A higher preload raises the overall contact force and system stiffness but does not suppress the load fluctuations from random errors. Therefore, precise control of geometric tolerances combined with an appropriate preload setting is essential for ensuring performance stability and service life of linear rolling guides.

It should be noted that this study focuses on the static mechanical characteristics of linear guides. In practical engineering applications, factors such as lubrication and damping also play significant roles in dynamic stability and long-term wear resistance. Future research could extend the current static model to incorporate these dynamic variables for a more comprehensive performance prediction.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.D. and W.L.; methodology, W.L.; software, C.H. and W.L.; validation, R.X. and Y.Y.; formal analysis, C.H.; investigation, Y.Y.; resources, C.H.; data curation, C.H.; writing—original draft preparation, W.L.; writing—review and editing, X.D.; visualization, W.Z.; supervision, X.D.; project administration, X.L.; funding acquisition, L.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The work was financially supported by the Key R&D Program of Jiangxi Province (20243BBG71013).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Hung, J.-P.; Lai, Y.-L.; Lin, C.-Y.; Lo, T.-L. Modeling the Machining Stability of a Vertical Milling Machine under the Influence of the Preloaded Linear Guide. Int. J. Mach. Tools Manuf. 2011, 51, 731–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimizu, S. Stiffness Analysis of Linear Motion Rolling Guide. J. Jpn. Soc. Precis. Eng. 1998, 64, 1573–1576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, J.; Kang, E.; Jeong, J. Equivalent Stiffness Modeling of Linear Motion Guideways for Stage Systems. Int. J. Precis. Eng. Manuf. 2014, 15, 1987–1993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dadalau, A.; Groh, K.; Reuß, M.; Verl, A. Modeling Linear Guide Systems with CoFEM: Equivalent Models for Rolling Contact. Prod. Eng. Res. Devel. 2012, 6, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; Kong, X.; Wang, B.; Li, X. Statics Modeling and Analysis of Linear Rolling Guideway Considering Rolling Balls Contact. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part C J. Mech. Eng. Sci. 2015, 229, 168–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohta, H.; Tanaka, K. Vertical Stiffnesses of Preloaded Linear Guideway Type Ball Bearings Incorporating the Flexibility of the Carriage and Rail. J. Tribol. 2010, 132, 11102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, H.T.; Wang, B.L. Investigation of the Contact Stiffness Variation of Linear Rolling Guides Due to the Effects of Friction and Wear during Operation. Tribol. Int. 2015, 92, 472–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, V.-C.; Khim, G.; Hong, S.-W.; Park, C.-H. Construction and Validation of a Theoretical Model of the Stiffness Matrix of a Linear Ball Guide with Consideration of Carriage Flexibility. Mech. Mach. Theory 2019, 140, 123–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, D.-J.; Xu, S.-H.; Kim, S.-J.; Zhang, S.-W. Analysis of Non-Uniform Load Distribution and Stiffness for a Preloaded Roller Linear Motion Guide. Mech. Mach. Theory 2021, 164, 104407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Li, C.; Wei, J. An Analytical Model of Static Stiffness for Linear Rolling Guideway Considering the Structural Deformations of Carriage. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part C J. Mech. Eng. Sci. 2022, 236, 370–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Huang, J.-B. Vertical Stiffness Model of Linear Motion Guide Considering Flexibility of Carriage. China Mech. Eng. 2011, 22, 1546. [Google Scholar]

- Shaw, D.; Su, W.L. Stiffness Analysis of Linear Guideways without Preload. J. Mech. 2013, 29, 281–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olaru, D.N.; Lorenz, P.; Rudy, D.; Prisacaru, G.; Antălucă, D. Friction in the Circular-Arc Grooves Linear Rolling Guidance System. Tribol. Schmier. 2004, 51, 8–12. [Google Scholar]

- Mahdi, R.; Stephan, K.; Friedrich, B. Experimental Investigations on Stick-Slip Phenomenon and Friction Characteristics of Linear Guides. Procedia Eng. 2015, 100, 1023–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmani, M.; Bleicher, F. Experimental and Analytical Investigations on Normal and Angular Stiffness of Linear Guides in Manufacturing Systems. Procedia CIRP 2016, 41, 795–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmani, M.; Bleicher, F. Experimental and Numerical Studies of the Influence of Geometric Deviations in the Performance of Machine Tools Linear Guides. Procedia CIRP 2016, 41, 818–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Wang, L.; Zhao, W. Hybrid Modeling and Analysis of Multidirectional Variable Stiffness of the Linear Rolling Guideway under Combined Loads. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part C J. Mech. Eng. Sci. 2020, 234, 2716–2727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, K.; Zhou, C.; Feng, H.; Wang, X. Research on Load Distribution of Rolling Guide under Specific 5D Loading Condition. Modul. Mach. Tool Autom. Manuf. Tech. 2021, 27–32+37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhen, N.; An, Q. Analysis of Stress and Fatigue Life of Ball Screw with Considering the Dimension Errors of Balls. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2018, 137, 68–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhang, G.; Fan, H.; Fan, Z.; Huang, Y. Effect of Off-Sized Balls on Contact Stiffness and Stress and Analysis of the Wear Prediction Model of Linear Rolling Guideways. Adv. Mech. Eng. 2021, 13, 16878140211034433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Zhang, P. Modeling and Analysis of Coulomb Friction for Linear Ball Guide. Modul. Mach. Tool Autom. Manuf. Tech. 2023, 12, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Majda, P. Modeling of Geometric Errors of Linear Guideway and Their Influence on Joint Kinematic Error in Machine Tools. Precis. Eng. 2012, 36, 369–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, Y.; Zhou, H.; Shao, C.; Li, J. Research on the Error Averaging Effect in A Rolling Guide Pair. Chin. J. Mech. Eng. 2019, 32, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yali, M.A.; Yangyang, L.I. Motion Error of Rolling Guide Based on Uncertainty of Geometric Error. J. Mech. Eng. 2019, 55, 11–18. [Google Scholar]

- Tong, V.-C.; Kwon, S.-W.; Hong, S.-W. Modeling of Moving Table with Linear Roller Guides Subjected to Geometric Errors In Guide Rails. Int. J. Precis. Eng. Manuf. 2020, 21, 1903–1919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, L.; Xudong, W.; Xiaoyi, W.; Jianwen, F.; Benzhe, F.; Yi, O.U.; Hutian, F. Relationship of Raceway Center Distance Errors and Load-Bearing Performance of Rolling Linear Guide Pairs. China Mech. Eng. 2021, 32, 2254. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, W.; Zhang, S.; Lin, J.; Jiang, S.; Chen, Z.; Zhu, H.; Wang, C.; Liu, W.; Cong, X. Investigation of Static Characteristics for Linear Rolling Guide with Considering Geometric Errors. Tribol. Int. 2023, 187, 108698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Zhang, S.; Lin, J.; Jiang, S.; Chen, Z. Effect of Combined Geometric Errors on Static Load Distribution and Deformations for Linear Rolling Guide. Tribol. Int. 2024, 191, 109079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, B.C. Mechanical Design Manual-Bearing, 5th ed.; China Machine Press: Beijing, China, 2014. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Krampert, D.; Ziegler, M.; Unsleber, S.; Reindl, L.; Rupitsch, S.J. On the Stiffness Hysteresis of Profiled Rail Guides. Tribol. Int. 2021, 160, 107019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.