Abstract

This study investigates the influence of ore particle shape on the wear behavior of ball mill liners using the Rocky-DEM software. A simulation model of a laboratory-scale ball mill was established to analyze the wear patterns of liners under three different ore particle shapes: polyhedron, ellipsoid, and sphere. The results indicate that while the overall motion patterns of the charge showed minor differences across particle shapes, significant variations were observed in flowability, with the polyhedral system exhibiting the lowest fluidity. Particle shape had a negligible impact on translational velocity but a substantial effect on rotational velocity. Regarding liner wear, the polyhedral system generated significantly higher wear compared to the spherical and ellipsoidal systems. The polyhedral system also exhibited the highest shear stress, identifying shear stress as the core factor dominating liner wear. The wear-time curves for individual liners in both radial and axial directions displayed a stepwise increase, suggesting that wear is primarily concentrated in the toe region.

1. Introduction

As the core equipment in mineral grinding processes, the efficiency of ball mills directly influences the quality of beneficiation products and production cost, playing an irreplaceable role in mineral processing flowsheets [1,2,3,4]. However, ball mills face critical technical challenges, including high energy consumption—accounting for over 50% of total plant power usage [5,6]—and severe liner wear. Liners are the primary consumable components, with annual consumption reaching approximately 4 × 106 tons and associated maintenance costs constituting about 6% of total grinding operational expenditures [7]. Previous research has primarily focused on optimizing liner materials [8,9], mill cylinder and liner structural parameters [10,11], and operational parameters such as mill speed [12,13,14] and filling level [15,16,17,18]. In contrast, the dynamic influence of ore particle shape on wear of ball mill liner remains underexplored.

The discrete element method (DEM) has become a key tool for studying liner wear due to its advantages in analyzing internal granular dynamics [19,20,21]. Currently, DEM simulations have predominantly focused on spherical particles [22,23]. However, both experimental and numerical studies on non-spherical particles indicate that particle shape exerts a significant influence on their dynamic properties [24]. Under hypergravity conditions, the introduction of non-spherical particles can significantly alter the dynamic angle of repose of a particle bed and the average particle velocity, thereby affecting mixing efficiency [25]. Accurate description of particle shape and in-depth investigation of its influence on flow, mixing, and segregation are of considerable importance for revealing the dynamic characteristics of granular systems [26,27,28]. Compared to spherical particles, the primary challenges in DEM simulations for non-spherical particles lie in two aspects: contact detection between non-spherical particles is more complex, and the corresponding collision contact algorithms must be adjusted as particle morphology varies; furthermore, achieving high precision in resolving the forces between non-spherical particles remains difficult, which to some extent limits the advancement of DEM for non-spherical particles. Currently, methods for describing the shape of non-spherical particles mainly include the multi-sphere model, the super-ellipsoid model, and the polyhedral model, among others [29,30,31,32,33,34].

However, traditional DEM often simplifies particles as spheres, which fails to accurately capture the complex shapes of real ore particles, leading to discrepancies in wear predictions [35,36,37]. To address this limitation, researchers have introduced non-spherical particle models [38,39]. Notably, Rocky-DEM 2022 R2 software supports complex particle shapes, providing a robust platform for such investigations.

This study employs Rocky-DEM software to establish a ball mill model and investigates the effects of three distinct ore particle shapes (polyhedron, ellipsoid, and sphere) on charge load behavior and liner wear characteristics. The research aims to reveal the mechanisms through which particle shape influences liner wear, providing a theoretical foundation for optimizing liner design and enhancing grinding efficiency. The discrete element simulation analysis in this paper is primarily based on a Φ520 mm × 260 mm laboratory-scale ball mill and does not consider factors such as the fracture of ore and steel balls. It constitutes an exploratory analytical study, offering insights for actual operational conditions.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Geometric Model

The Rocky DEM (Rocky-Discrete Element Method) is a discrete element software package developed by ESSS (Engineering Simulation and Scientific Software Ltd.) based in Florianópolis, Brazil. As a general-purpose simulation tool grounded in the discrete element method, Rocky DEM is designed to model the motion, breakage, and wear behavior of solid particles. It has been widely adopted across various industries, including mining equipment, construction machinery, chemical processing, metallurgy, food production, and pharmaceuticals [40]. The software offers several notable advantages: it enables the rapid and convenient creation of highly complex particle systems and geometries; it accurately simulates particle dynamics; it allows for the integration of variable physical properties, such as moisture content and dryness; it features a unique and robust particle breakage modeling algorithm; it supports both one-way and two-way fluid–structure interaction simulations through seamless integration with ANSYS Fluent 2024; and it incorporates advanced parallel computing technologies that support both CPU and GPU acceleration.

In the DEM simulations, the interparticle contact forces during collisions include material–material, material–steel ball, and liner–material interactions. The calculation of collisions between materials as well as between steel balls and materials is predominantly governed by the selected contact force model. In this study, the normal contact force is modeled using a hysteretic linear spring model, the tangential contact force is described by a linear spring–Coulomb limit model, and the particle friction moment is represented by a linear spring–rolling limit model.

This study uses a Φ520 mm × 260 mm laboratory-scale ball mill as the prototype. The interior of the ball mill cylinder features twelve uniformly distributed trapezoidal liners, with cross-sectional dimensions of 20 mm (upper base), 33 mm (lower base), and 20 mm (height). The mill has an effective volume of 5.37 × 10−2 m3 and a critical speed of 58.80 r/min. The geometrical model of the Φ520 mm × 260 mm laboratory-scale ball mill is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Geometrical model of cylinder.

2.2. Particle Model

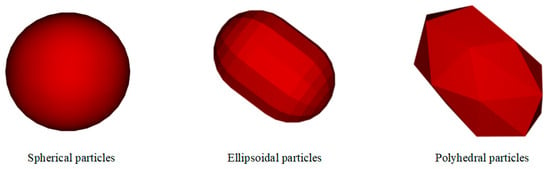

The DEM simulation is a widely used approach for analyzing the kinematics of grinding media in ball mills. In studying the motion of charge, researchers often simplify material particles as spheres or approximate their actual shapes. To investigate the influence of ore particle shape on the charge motion behavior and the liner wear behavior, this study uses iron ore particles as the raw material and selects three particle shapes—sphere, ellipsoid, and polyhedron—for geometric modeling. Among these, the spherical particles have a vertical aspect ratio of 1, the ellipsoidal particles have a vertical aspect ratio of 1.5, and the polyhedral particles also have a vertical aspect ratio of 1.5. The geometric parameters of the polyhedral particles are listed in Table 1, and the geometric models of the three ore particle shapes are shown in Figure 2.

Table 1.

Geometric parameters of polyhedral particles.

Figure 2.

Geometric models of the three particle shapes.

2.3. Wear Model

The wear model adopted in the Rocky DEM software used in this study is based on the Archard wear law [41], and the calculation formula is as follows:

where V represents the total volume of material loss in cubic meters (m3); F denotes the vertical force acting on the contact surface in newtons (N); s indicates the total relative sliding distance between the two surfaces in meters (m); H stands for the material hardness; and k is the dimensionless wear coefficient.

2.4. DEM Simulation Parameters

The DEM simulation parameters and the ball mill model in this study are based on Yin’s paper [42], utilizing steel balls as the grinding media and iron ore as the material particles. The DEM simulation parameters are listed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Parameters of DEM simulation.

2.5. DEM Simulation

The numerical softening factor in the DEM simulation model employed in this study is set to 0.1. The experimental operating parameters are identical for the three ore particle shapes with different geometries. The mill cylinder begins rotating at the 1st second, reaches a steady operating state by the 4th second, and the liner wear calculation commences at the 7th second. The simulation proceeds until the 15th second, at which point data on grinding media velocity and liner wear are analyzed. The DEM simulation schemes for the three ore particle shapes with different geometries are detailed in Table 3.

Table 3.

DEM simulation scheme.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Analysis of Charge Load Behavior

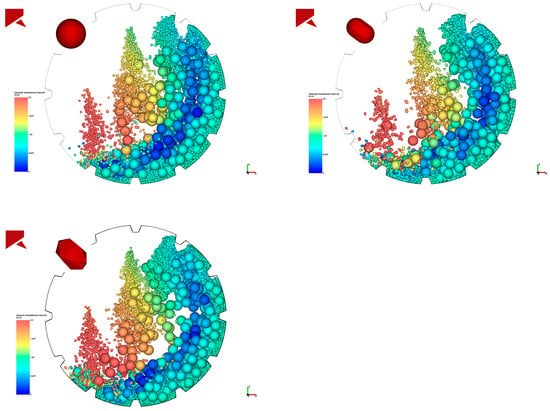

Figure 3 shows the distribution of grinding media motion under conditions involving particles of different shapes. Under the three different particle shape conditions, the differences in the distribution of grinding media motion are relatively small. To investigate the distinctions in their media motion, two characteristic parameters—shoulder angle and toe angle—are introduced for analysis, as illustrated in Figure 4.

Figure 3.

Distribution of charge motion under different particle shape conditions.

By conducting numerical analysis on the motion characteristic parameters of the charge group, and analyzing their motion characteristics, it is helpful to optimize the ball milling parameters. The definitions of the shoulder angle and toe angle are as follows [42]:

Shoulder Angle: The shoulder angle refers to the angle at which the medium group is lifted and about to fall off the surface of the cylinder.

Toe Angle: The toe angle refers to the angle at which the medium in the discharge area slides along the surface of the medium group and reaches the highest point on the bottom surface of the cylinder.

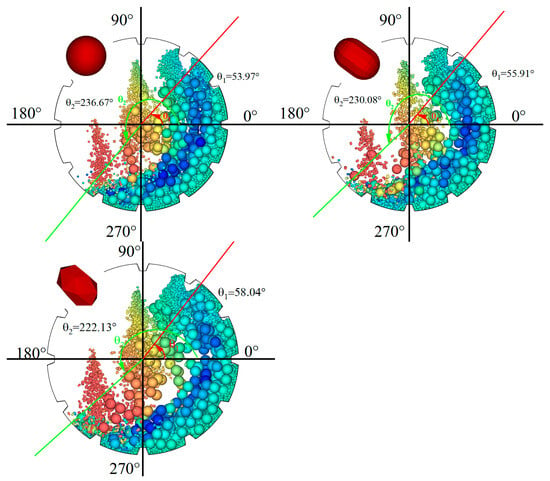

As shown in Figure 4, it is the distribution diagram of the shoulder angle and toe angle corresponding to different ore particle shapes at the radial cross-section at 15 s. In the figure, θ1 represents the shoulder angle and θ2 represents the toe angle. It can be seen from the figure that the shape of the ore particles has a significant impact on the size of the shoulder angle and toe angle. The overall trend is that the smoother the particle shape, the larger the shoulder angle and toe angle. The shoulder angle reflects the height of the particle when the medium group is lifted to the highest point, that is, the level of gravitational potential energy obtained by the particle. From the picture, the shoulder angle of the polyhedron system is 58.04°, and that of the spherical system is 53.97°; the toe angle of the polyhedron system is 222.13°, while that of the spherical system is 236.67°, and the difference is significant. Therefore, it can be inferred that the degree of wear on the liner by different ore systems also varies significantly. Although the height difference at the highest point position of each system is small, there are obvious differences in the particle accumulation in the shoulder angle and toe angle regions, especially in the toe angle region, where the particle accumulation in the polyhedron system is more significant. In addition, the energy obtained by different ore systems in the cylinder is relatively small, indicating that the shape of the ore has a relatively limited impact on the shoulder angle.

Figure 4.

The comparative distribution map of shoulder angles and toe angles for different ore particle shapes.

3.2. Analysis of Ore Particle Velocity

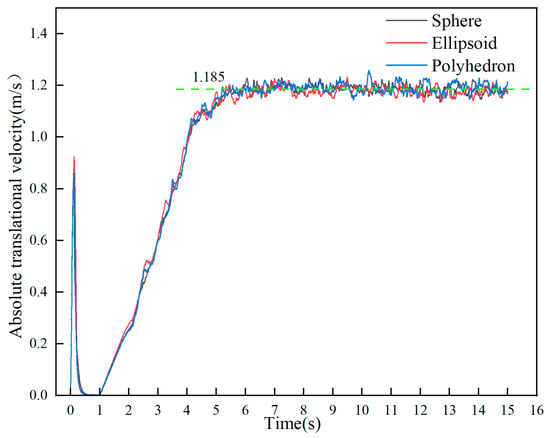

To investigate the influence of ore particle shape on their absolute translational velocity (hereinafter referred to as translational velocity) and absolute rotational velocity (hereinafter referred to as rotational velocity), the changing trends of translational velocity and rotational velocity of total particles in different ore systems were analyzed. As shown in Figure 5, there are significant differences in translational velocity and rotational velocity among particles in different ore systems. Starting from 0 s, the particles are in a filling state at the initial stage, and then fall onto the inner wall of the cylinder under the action of gravity. Currently, the translational velocity and rotational velocity show rapid increases and decreases, respectively. At 1 s, the overall velocity of the system begins to rise, mainly due to the acceleration of the cylinder’s rotation. The translational velocity significantly increases from 1 s to 4 s, then the growth rate slows down, and around 6 s, the overall ore system enters a stable falling state. The translational velocities of the three different-shaped ore particles tend to be consistent, stabilizing at approximately 1.185 m/s.

Figure 5.

The variation in the absolute translational velocity and rotational velocity for different ore particle shapes.

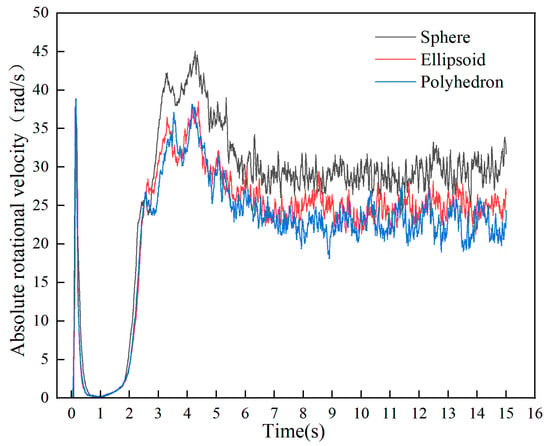

Regarding the rotational velocity, around 3 s, the rotational velocities of the three ore systems are relatively close; however, from 3 s to 5 s, the rotational velocity of the spherical system is significantly higher than that of the ellipsoidal and polyhedral systems, reaching up to approximately 45 rad/s, while the latter two do not exceed 40 rad/s at their peaks. From 5 s to 7 s, the rotational velocities of all three ore systems show a downward trend [31]. Subsequently, the spherical system stabilizes at approximately 30 rad/s with fluctuations, the ellipsoidal system stabilizes at approximately 26 rad/s with fluctuations, and the polyhedral system stabilizes at approximately 23 rad/s with fluctuations, and its fluctuation amplitude is relatively larger. In conclusion, there are relatively small differences among different ore systems in terms of translational velocity, but significant differences in rotational velocity. Particularly, the polyhedral particles have the lowest rotational velocity and the strongest fluctuation, indicating that particle shape has a more significant impact on rotational motion.

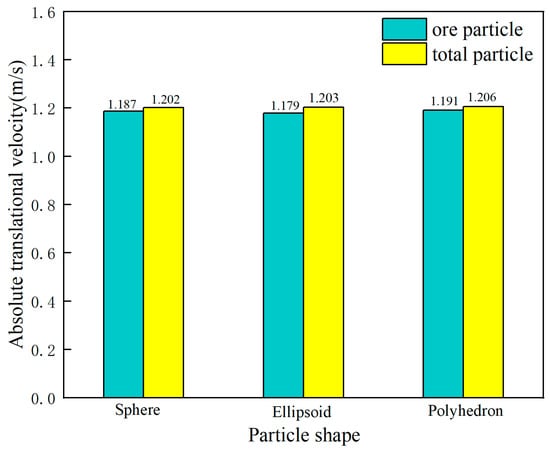

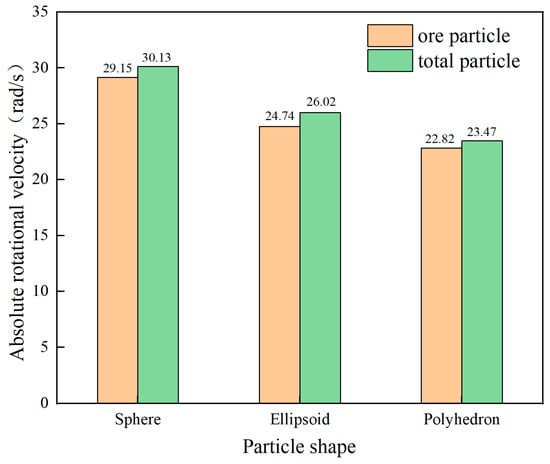

From the above analysis, it can be seen that when the cylinder operates for 7 s, the particle system has entered a stable motion state. Therefore, all subsequent studies are based on this stable stage. Figure 6 shows the average data of the translational and rotational velocity of the overall particles and different ore particles during the period of 7 s to 15 s. Data analysis indicates that the translational velocity of all ore systems is stably around 1.18 m/s. Among them, the translational velocity of the ore particles and total particles in the polyhedron system are 1.23 m/s and 1.19 m/s, respectively, showing a slight advantage; while the translational velocity of the ore particles in the ellipsoid system is the lowest (1.15 m/s). In terms of rotational velocity, there are significant differences among different ore systems: the spherical system leads with a rotational velocity of 29.15 rad/s, while the ellipsoid (24.74 rad/s) and polyhedron (22.82 rad/s) systems are reduced by 17.3% and 27.8% respectively, and the fluctuation range of the rotational velocity in the polyhedron system is about 35% higher than that in other systems. This phenomenon verifies the significant regulatory effect of the shape of ore particles on the rotational dynamic characteristics.

Figure 6.

Comparison of absolute translational velocity and rotational velocity for different ore particle shapes.

3.3. Analysis of Liner Wear

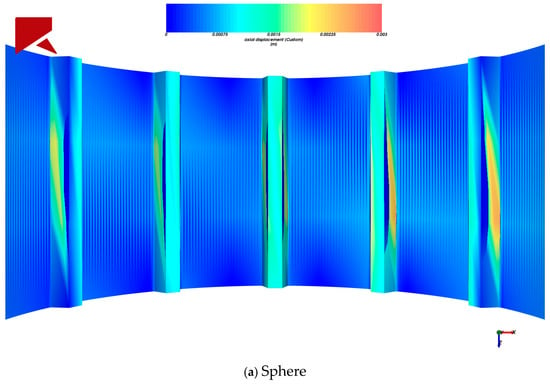

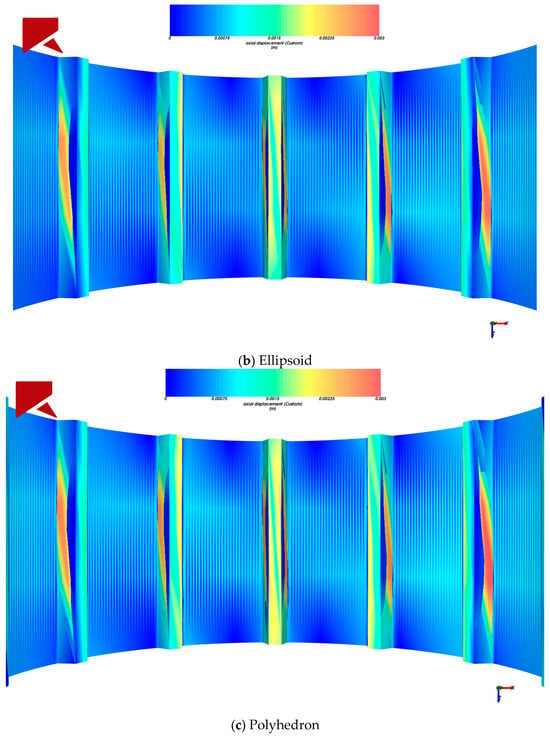

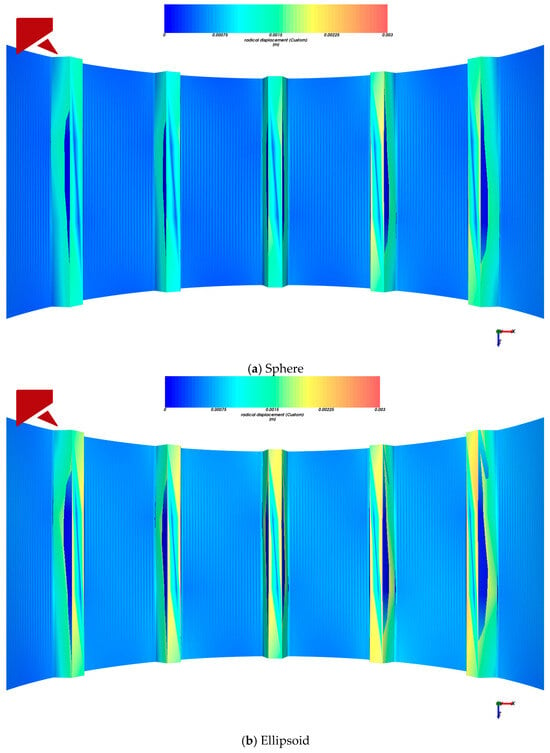

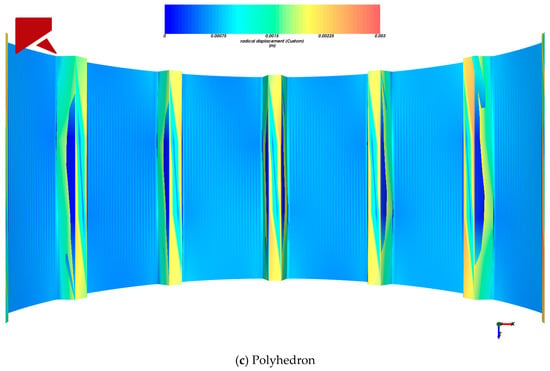

The liner is a critical component of the ball mill, serving to protect the cylinder and lift the charge to enhance motion. The wear evolution process of the liner exhibits a strong coupling relationship with grinding media dynamics, significantly influencing alterations in the trajectory of the mill load and improvements in breakage efficiency. Based on the Archard wear model, the liner wear calculation was initiated at 7 s and terminated at 15 s. To investigate the influence of material particle shape on the liner wear mechanism, this study analyzed wear characteristics from two perspectives: overall liner wear and individual liner wear, establishing the relationship between different material particle shapes and the resulting stress distribution on the liner surface. The wear morphology of the liner is shown in Figure 7 and Figure 8.

Figure 7.

The axial wear morphology of the liner.

Figure 8.

The radial wear morphology of the liner.

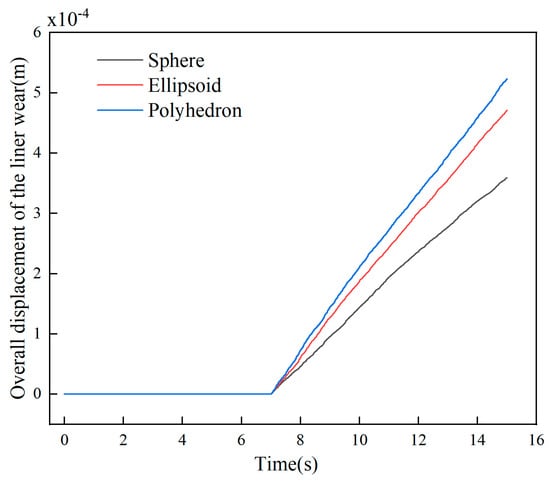

Figure 9 illustrates the relationship between the overall liner wear displacement (wear depth, the following are all expressed in terms of displacement) and time evolution. It is evident that the polyhedral particle system exhibited the maximum wear displacement at 7 s, reaching a cumulative wear depth of 5.23 × 10−4 m by 15 s. This represents an increase of 11.1% and 45.7% compared to the ellipsoidal system (4.71 × 10−4 m) and spherical system (3.59 × 10−4 m), respectively. Notably, this phenomenon showed no positive correlation with the translational or rotational velocities of the particle systems. It is hypothesized that the underlying mechanism stems from the intermittent point contacts induced by the sharp edges of polyhedral particles. These discontinuous impacts generate greater cumulative deformation per unit time compared to the sustained surface contact characteristic of spherical particles. The modulation effect of geometric morphology differences on the energy transfer path during collisions serves as the dominant factor.

Figure 9.

Overall displacement of the liner wear.

The calculation formula for the wear and displacement of the liner is:

Among them, D(overall) represents the total wear displacement, while D(x), D(y), and D(z) respectively denote the wear depth of the liner in the three directions.

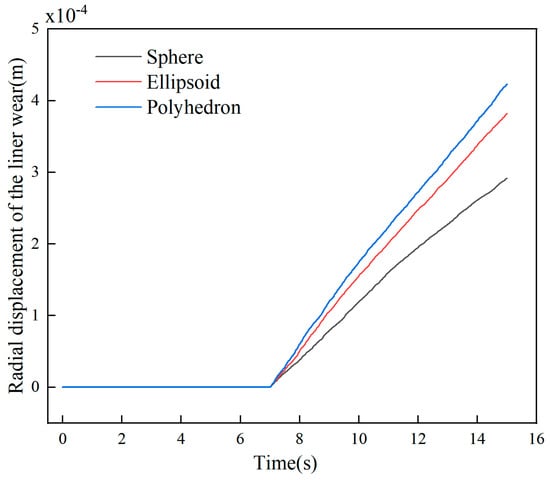

To further analyze the axial and radial wear displacement of the liner, the variations in the overall wear displacement along both the axial and radial directions were investigated separately, as shown in Figure 10. The results reveal that the cumulative wear depth for the spherical system was 2.14 × 10−4 m axially and 1.89 × 10−4 m radially. This corresponds to reductions of 27.3% and 21.8%, respectively, compared to the ellipsoidal system, and more substantial reductions of 45.1% and 39.7% compared to the polyhedral system. And it can be known that, compared with axial wear, the radial wear is greater.

Figure 10.

Axial and radial wear displacement of liner.

The calculation formulas for axial wear displacement and radial wear displacement are as follows:

Among them, D(radial) represents axial wear displacement, and D(axial) represents radial wear displacement. while D(x), D(y), and D(z) respectively denote the wear depth of the liner in the three directions.

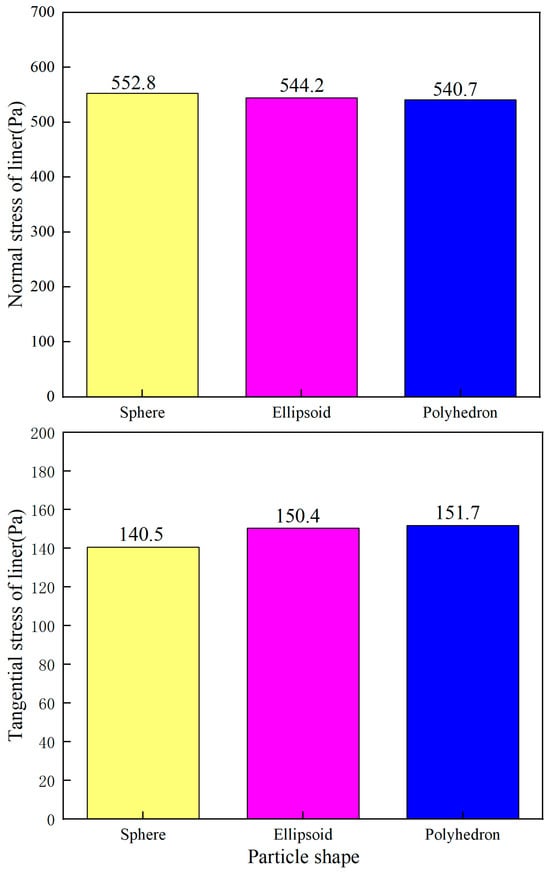

To investigate the variation in liner stress, the average normal and tangential stresses on the liner under stable operating conditions (7–15 s) were analyzed based on the discrete element contact mechanics model, as presented in Figure 11. The analysis revealed that the spherical particle system exhibited an average normal stress of 552.8 Pa, representing a 2.24% increase over the polyhedral system (540.7 Pa). Conversely, the polyhedral system displayed a higher average tangential stress of 151.7 Pa, which was 7.96% greater than that of the spherical system. Therefore, compared to normal stress, tangential stress (shear stress) is the main cause of the wear of the liner. The relationship with the rotational velocity is negatively correlated. Among them, the rotational velocity of the spherical ore particles is the highest, but the shear stress generated on the liner is the lowest. The elevated tangential stress associated with the polyhedral system results in more severe liner wear, consistent with the wear displacement analysis presented earlier.

Figure 11.

The variation of liner stress for different ore particle shapes.

To quantitatively characterize the wear behavior of an individual liner, a specific liner region measuring 0.1 mm × 0.03 mm × 0.26 mm was selected for analysis. This region was used to investigate the evolution of wear and its spatial distribution on the single liner surface, as depicted in Figure 12.

Figure 12.

Individual liner selection area.

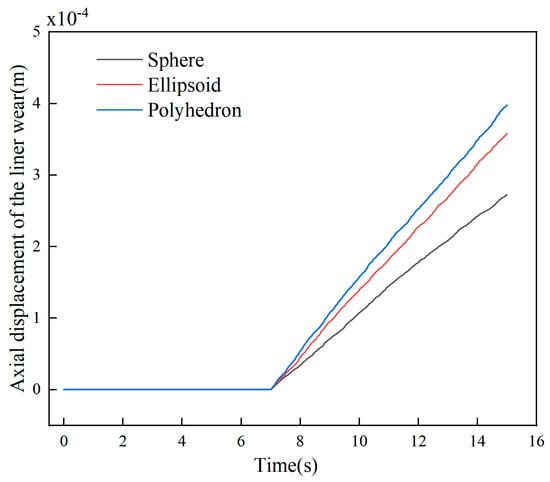

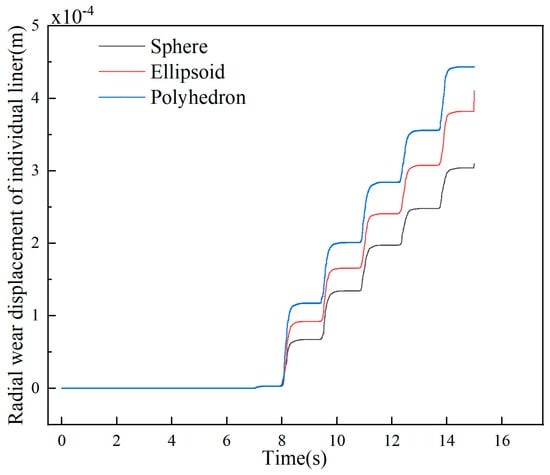

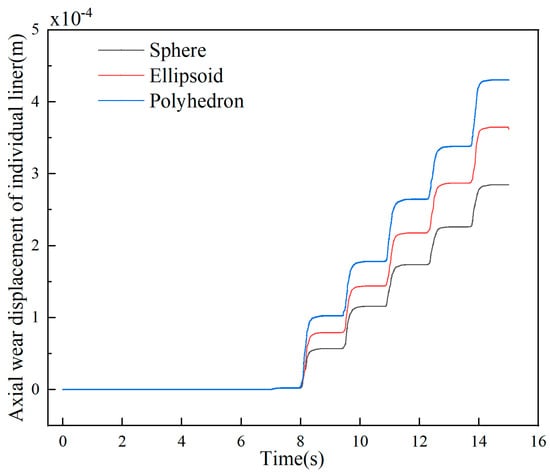

Figure 13 presents the variation curves of radial and axial wear displacement versus time for the individual liner. The results demonstrate a stepwise increase in wear displacement commencing at 8 s, indicating that the primary wear zone is concentrated in the toe region. This concentration is attributed predominantly to the impact and shear forces exerted on the liner by the cascading ore particles. Furthermore, the degree of liner wear exhibited an inverse correlation with normal stress and a positive correlation with tangential stress, confirming that tangential stress is the primary governing mechanical factor in liner wear behavior.

Figure 13.

Axial and radial wear displacement for individual liner.

4. Conclusions

This study systematically investigated the impact of ore particle shape on ball mill liner wear using Rocky-DEM simulations. The primary conclusions are as follows:

- (1)

- Particle shape significantly influences the flowability of the mill charge. Polyhedral particles, due to their complex geometry, result in the poorest flowability, whereas spherical particles facilitate the best flow.

- (2)

- While particle shape has a negligible effect on the translational velocity of the charge, it substantially affects rotational velocity. Polyhedral particles exhibit markedly lower rotational speeds.

- (3)

- Liner wear is profoundly affected by particle shape. The wear caused by polyhedral particles is 2.71 times and 1.98 times greater than that caused by spherical and ellipsoidal particles, respectively.

- (4)

- Shear stress is identified as the core factor dominating liner wear. The polyhedral particle system generates the highest shear stress, which directly corresponds to its most severe wear outcome.

- (5)

- The wear on individual liners increases in a stepwise manner along both radial and axial directions, with the majority of wear concentrated in the toe region of the charge motion.

Author Contributions

Methodology, Z.Y.; Investigation, Z.Y.; Writing—original draft, X.P.; Writing—review & editing, X.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Anhui Province’s In-Province Visiting and Research Program for Young Backbone Teachers [grant number JNFX2024063], the Key Research and Development Program Projects in Anhui Province [grant number 2023t070200], the Excellent Academic Technology Backbone Project of Suzhou University [grant number 2024XJGG08], and the Anhui Province Higher Education Quality Project [grant number 2023sdxx088].

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank Yin conceived and designed the schemes; Pan performed the experiments and analyzed the data.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Mishra, B.K.; Rajamani, R.K. The discrete element method for the simulation of ball mills. Appl. Math. Model. 1992, 16, 598–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenkranz, S.; Breitung-Faes, S.; Kwade, A. Experimental investigations and modelling of the ball motion in planetary ball mills. Powder Technol. 2011, 212, 224–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Z.; Peng, Y.; Zhu, Z.; Ma, C.; Yu, Z.; Wu, G. Effect of mill speed and slurry filling on the charge dynamics by an instrumented ball. Adv. Powder Technol. 2019, 30, 1611–1616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Yin, Y.; Li, C.; Xu, M.; Li, R.; Chen, Q. Preparation and properties of lead-free FeS/Cu-Bi composites by flake powder metallurgy via shift-speed ball milling. Adv. Powder Technol. 2022, 33, 103545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleary, P.W. Predicting charge motion, power draw, segregation and wear in ball mills using discrete element methods. Miner. Eng. 1998, 11, 1061–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleary, P.W. Recent advances in DEM modelling of tumbling mills. Miner. Eng. 2001, 14, 1295–1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, C.; Zhao, Y.; Song, T.; Zhao, Y. Investigation of the effect of filling level on the wear and vibration of a SAG mill by DEM. Particuology 2022, 63, 24–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Zhao, D.; Wang, Q.; Qiang, Y.; Qi, J. Effects of impact energy on the wear resistance and work hardening mechanism of medium manganese austenitic steel. Friction 2017, 5, 447–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Yu, L.; Wei, M.A.; Chen, R.F.; Ma, B. Application of Metal Magnetic Liners in a Grate Type Ball Mill. Min. Res. Dev. 2022, 42, 50–53. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, B.; Kim, D.M.; Olav, S.; Michael, M. Expandable Liner Hanger Milling: North Sea Case Histories. In Proceedings of the SPE/IADC Drilling Conference, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 5–7 March 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djordjevic, N.; Shi, F.N.; Morrison, R. Determination of lifter design, speed and filling effects in AG mills by 3D DEM. Miner. Eng. 2004, 17, 1135–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Z.; Peng, Y.; Zhu, Z.; Yu, Z.; Li, T. Impact load behavior between different charge and lifter in a laboratory-scale mill. Materials 2017, 10, 882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleary, P. Modelling comminution devices using DEM. Int. J. Numer. Anal. Methods Geomech. 2001, 25, 83–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleary, P.W.; Owen, P. Development of models relating charge shape and power draw to SAG mill operating parameters and their use in devising mill operating strategies to account for liner wear. Miner. Eng. 2018, 117, 42–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaya, Y.; Kobya, V.; Mardani, A.; Mardani, N.; Beytekin, H.E. Effect of grinding conditions on clinker grinding efficiency: Ball size, mill rotation speed, and feed rate. Buildings 2024, 14, 2356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleary, P.W.; Morrison, R.D. Understanding fine ore breakage in a laboratory scale ball mill using DEM. Miner. Eng. 2011, 24, 352–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delaney, G.W.; Cleary, P.W.; Morrison, R.D.; Cummins, S.; Loveday, B. Predicting breakage and the evolution of rock size and shape distributions in Ag and SAG mills using DEM. Miner. Eng. 2013, 50, 132–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Z.; Peng, Y.; Li, T.; Zhu, Z.; Yu, Z.; Wu, G. Effect of the operating parameter and grinding media on the wear properties of lifter in ball mills. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part J J. Eng. Tribol. 2020, 234, 1061–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleary, P.W. Charge behaviour and power consumption in ball mills: Sensitivity to mill operating conditions, liner geometry and charge composition. Int. J. Miner. Process. 2001, 63, 79–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y. Numerical Simulation Study on the Influence of Grinding Media and Loading Quantity on the Operating Characteristics of Ball Mill. Master’s Thesis, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou, China, 2020. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Ma, H.Q.; Zhao, Y.Z. DEM Simulation Study on the Influence of Grinding Medium Shape on the Characteristics of Ball Mill. Min. Mach. 2020, 48, 38–45. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavarez, F.A.; Plesha, M.E. Discrete element method for modelling solid and particulate materials. Int. J. Numer. Methods Eng. 2007, 70, 379–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Third, J.R.; Scott, D.M.; Scott, S.A.; Müller, C.R. Effect of periodic boundary conditions on granular motion in horizontal rotating cylinders modelled using the DEM. Granul. Matter 2011, 13, 75–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Lu, G.; Third, J.R.; Muller, C.R. Discrete element models for non-spherical particle systems: From theoretical developments to applications. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2015, 127, 425–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wachs, A.; Girolami, L.; Vinay, G.; Ferrer, G. Grains3D, a flexible DEM approach for particles of arbitrary convex shape—Part I: Numerical model and validations. Powder Technol. 2012, 224, 374–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasouli, M.; Dubé, O.; Bertrand, F.; Chaouki, J. Investigating the dynamics of cylindrical particles in a rotating drum using multiple radioactive particle tracking. AIChE J. 2016, 62, 2622–2634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, Y.; Hunt, M.; Huang, J.; Liao, C.-C. Experimental investigation into segregation behavior of spherical/non-spherical granular mixtures in a thin rotating drum. Phys. Fluids 2024, 36, 023342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Jin, B.; Zhong, W. Experimental investigation on mixing and segregation behavior of biomass particle in fluidized bed. Chem. Eng. Process. Process Intensif. 2009, 48, 745–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, H.; Jin, B.; Zhong, W.; Wang, X.; Ren, B.; Zhang, Y.; Xiao, R. Discrete element method modeling of non-spherical granular flow in rectangular hopper. Chem. Eng. Process. Process Intensif. 2010, 49, 151–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabiscol, R.; Finke, J.H.; Kwade, A. Calibration and interpretation of DEM parameters for simulations of cylindrical tablets with multi-sphere approach. Powder Technol. 2018, 327, 232–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Shen, Y. Super-quadric CFD-DEM simulation of chip-like particles flow in a fluidized bed. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2022, 251, 117431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Ma, H.; Fan, T.; Liu, M.; Zhao, Y. DEM investigation of the conveyor belt sorting system for coated fuel particles with a large feeding rate. Powder Technol. 2022, 399, 117160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Ma, H.; Zhao, Y. CFD-DEM simulation of fluidization of polyhedral particles in a fluidized bed. Energies 2021, 14, 4939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govender, N.; Wilke, D.N.; Kok, S.; Els, R. Development of a convex polyhedral discrete element simulation framework for NVIDIA Kepler based GPUs. J. Comput. Appl. Math. 2014, 270, 386–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Luo, K.; Zhao, Y.; Fan, J.; Cen, K. Influence of particle shape on liner wear in tumbling mills: A DEM study. Powder Technol. 2019, 350, 26–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L. Research on Particle-Scale Wear Model Based on Tangential Impact Energy and Its Application. Ph.D. Thesis, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou, China, 2019. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbaspour-Fard, M.H. Theoretical validation of a multi-sphere, discrete element model suitable for biomaterials handling simulation. Biosyst. Eng. 2004, 88, 153–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.S. Discrete Element Simulation Analysis of Influencing Factors of Grinding Performance of Ball Mill. Master’s Thesis, Wuhan University, Wuhan, China, 2019. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Z.X.; Ma, D.M.; Li, T.Q. Effect of Grinding Media Grading on Liner Wear and Load Behavior in a Ball Mill by Using Rocky DEM. Lubricants 2024, 12, 340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, C.; Ma, H.; Song, T.; Zhao, Y. DEM investigation of SAG mill with spherical grinding media and non-spherical ore based on polyhedron-sphere contact model. Powder Technol. 2021, 386, 154–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archard, J.F. Contact and rubbing of flat surfaces. J. Appl. Phys. 1953, 24, 981–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Z.X. Research on the Crushing and Particle Size Distribution Behavior of Iron Ore Particles by Ball Mill. Ph.D. Thesis, China University of Mining and Technology, Xuzhou, China, 2020. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.