1. Introduction

A tribosystem is defined as a system composed of interacting surfaces in relative motion, often incorporating an interfacial medium such as a lubricant to accommodate differences in surface velocities. The structure of a tribosystem can be categorized into three primary components: the ground body and counter body, characterized by their material and geometrical properties; the interfacial medium, which may include liquid lubricants, solid lubricants, abrasive particles, or wear debris; and the ambient environment, which influences the system through factors such as temperature, humidity, and gaseous interactions [

1,

2].

Tribological systems are inherently complex due to the wide range of interacting factors that govern friction and wear behaviors. Functional outputs such as the coefficient of friction (COF) and wear are not intrinsic material properties but emergent responses influenced by the structure of the tribological system, the properties of the interfacial medium, and the operating environment [

1,

3]. Friction is the resistance to relative motion between two contacting bodies and arises from a combination of adhesive interactions, plastic deformations, elastic responses, and ploughing effects occurring at microscopic contact points [

1,

4]. Similarly, wear is defined as the irreversible loss of material from interacting surfaces, manifesting through mechanisms like adhesion, abrasion, fatigue, and corrosion, often operating concurrently and influenced by varying system parameters [

1,

5].

The nonlinear and interdependent nature of these mechanisms makes it exceedingly difficult to establish direct mathematical relationships between friction and wear. As a result, tribology has traditionally relied on empirical methods and experimental tests to characterize these properties [

6]. While empirical models provide valuable insights, they often lack the ability to generalize across different systems or predict performance under varying conditions. The four-ball tester, a standard experimental setup in tribology, remains a crucial tool for evaluating lubricant performance and wear characteristics due to these challenges [

2].

Recent advancements in machine learning, particularly deep learning, offer promising avenues to address the inherent complexity of tribological systems [

7,

8,

9]. Deep learning algorithms excel at modeling non-linear relationships and capturing subtle interactions within large datasets, making them well-suited for predicting friction and wear behaviors [

10,

11]. By leveraging experimental data and processing algorithms, deep learning models can uncover patterns and dependencies that are difficult to identify through traditional empirical approaches.

Recent studies have demonstrated the growing impact of data-driven and deep-learning frameworks in tribology. Kolev et al. [

12] employed a convolutional neural network to predict the COF of chromium-coated

alloys, achieving excellent predictive accuracy (

) and identifying coating hardness as the dominant variable influencing the COF and wear resistance. Shabana et al. [

13] implemented Gaussian Process Regression and Support Vector Regression models to estimate the COF and wear in WC–Co coatings, reducing experimental uncertainty and revealing load-dependent friction stabilization. Hasan and colleagues applied ensemble learning and neural networks to aluminum-based composites to correlate material properties, heat treatment and test variables with tribological responses [

14,

15]. Similarly, Chen et al. [

16] developed a hybrid GA–BP neural network to predict friction in bolted joints, illustrating the potential of evolutionary optimization in tribological modeling.

These works collectively highlight the capability of machine-learning algorithms to capture complex tribological behavior. Nevertheless, most existing frameworks are restricted to single-material systems or specific contact conditions, which limits their generalizability. Few studies explicitly include nanoadditive characteristics in their model inputs, despite their crucial influence on frictional and wear mechanisms. Moreover, to the authors’ knowledge, no previous work has focused on developing data-driven models specifically for the four-ball tribological test, a standard platform widely used in lubricant research and development to benchmark performance.

This study introduces a deep learning-based approach to predict the COF and wear scar diameter (WSD) over time, trained using experimental data from four-ball tester experiments with various lubricant formulations. The model integrates key variables such as lubricant properties, additive characteristics, and operating conditions, providing a comprehensive framework for understanding and predicting tribological performance. Our findings highlight the potential of deep learning to advance predictive maintenance strategies and optimize lubricant design, ultimately contributing to improved efficiency and durability in mechanical systems.

The detailed tribological results (COF and WSD) for the lubricant–additive systems studied here have been reported previously [

17,

18]. The novelty of the present work lies in curating these validated results into a unified dataset and leveraging them for data-driven modeling and predictive deployment, establishing an inherently scalable framework applicable to diverse lubricant formulations.

2. Data Collection

2.1. Apparatus and Materials

Tribological experiments were conducted using a four-ball tester (Ducom FBT-3), a standardized apparatus widely employed for evaluating the frictional and wear properties of lubricants under controlled conditions [

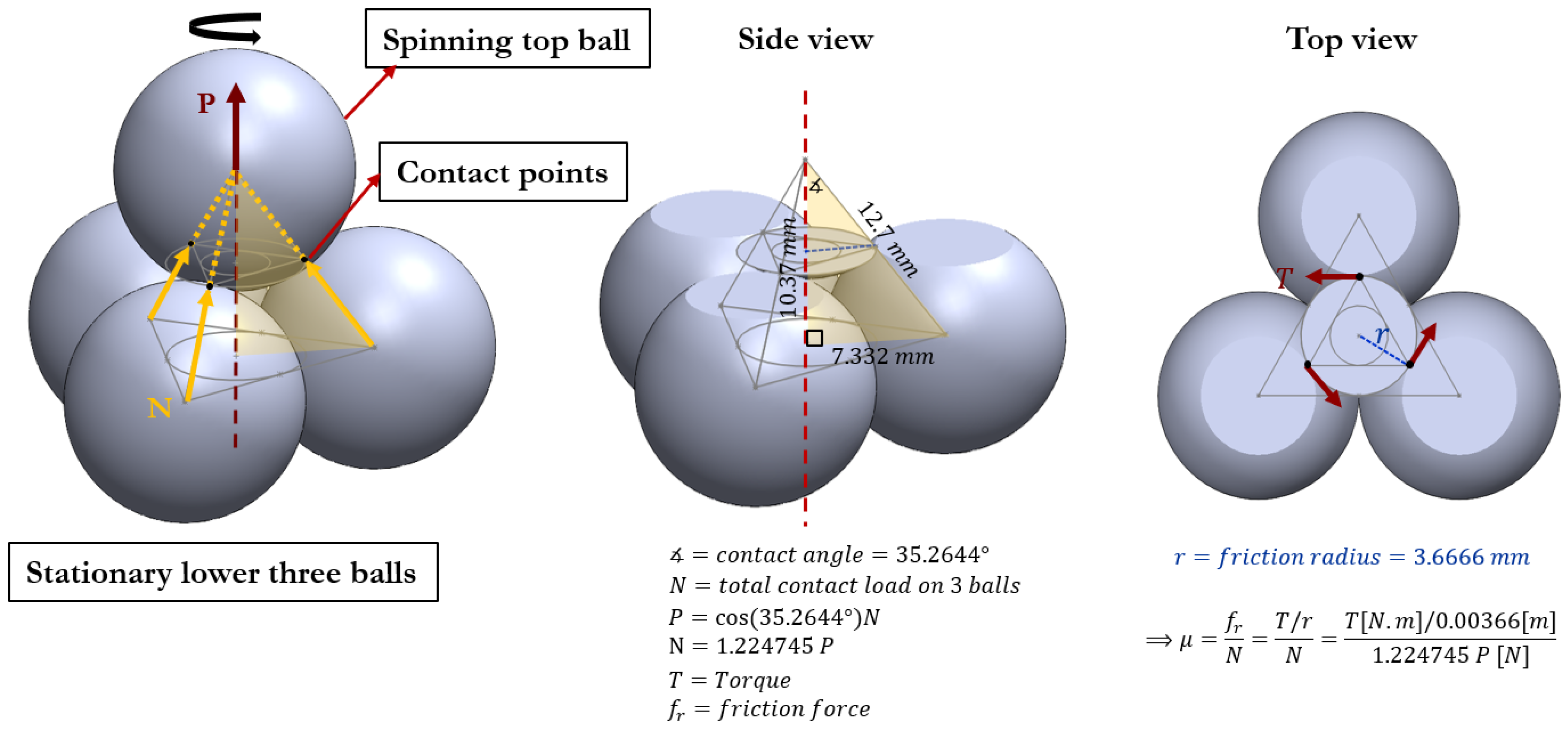

2]. In this configuration, three stationary balls are rigidly clamped in a triangular formation, while a fourth (upper) ball is pressed against them and rotated under a prescribed speed and load (See

Figure 1). This arrangement produces three Hertzian point contacts, generating localized stress concentrations representative of real-world tribological interactions in gears, bearings, and cam–follower systems.

All test balls were made of AISI 52100 chrome steel, with a diameter of 12.7 mm (Grade 25 EP), Rockwell C hardness of 64–66, and surface finish of μm. This material is specified by ASTM standards for its high hardness, wear resistance, and dimensional stability, ensuring consistent contact mechanics across experiments. Because the material, hardness, and surface finish were consistent across all tests, these parameters were held constant and excluded as input features in the subsequent machine learning models.

The balls and test assembly were cleaned before each run according to ASTM D4172, Standard Test Method for Wear Preventive Characteristics of Lubricating Fluid (Four-Ball Method) [

19]. The cleaning procedure involved sequential solvent cleaning and careful handling with lint-free wipes to eliminate anti-rust coatings, lubricant residues, and contaminants. The entire assembly was fully submerged in the lubricant during testing to guarantee continuous lubrication and maintain thermal stability throughout the duration of the experiment.

2.2. Coefficient of Friction Measurement

The coefficient of friction (COF) was determined following the ASTM D4172 protocol, which prescribes a constant rotational speed of 1200 rpm, an applied load of either 147 N (15 kgf) or 392 N (40 kgf), and a test temperature of

°C for 60 min [

19]. Frictional torque,

, was continuously recorded at 1 Hz by an integrated transducer. While ASTM D4172 defines the operating conditions, the conversion of torque to COF was performed using the geometric formulation provided in ASTM D5183 [

20]. The calculation procedure is summarized schematically in

Figure 2.

(1) Load decomposition. The four-ball contact geometry forms a regular tetrahedron, where the line of action of the normal force at each contact is inclined at

with respect to the vertical axis. Resolving the applied vertical load

P into the three contact normals gives:

where

is the normal load per contact. Thus,

with

the total normal load across the three contacts.

(2) Relation between torque and friction force. The tangential friction force,

, is related to the measured torque via the effective friction radius

:

(3) Definition of coefficient of friction. The COF is defined as the ratio of tangential to normal force:

Substituting Equations (

2) and (

3) into Equation (

4) yields the working expression:

(4) Calibration of friction radius. The effective friction radius,

, is instrument-specific and was determined experimentally following ASTM D5183 calibration guidelines. For the tester employed in this study,

Accordingly, the final working equation for the calculation of COF becomes:

2.3. Wear Measurement

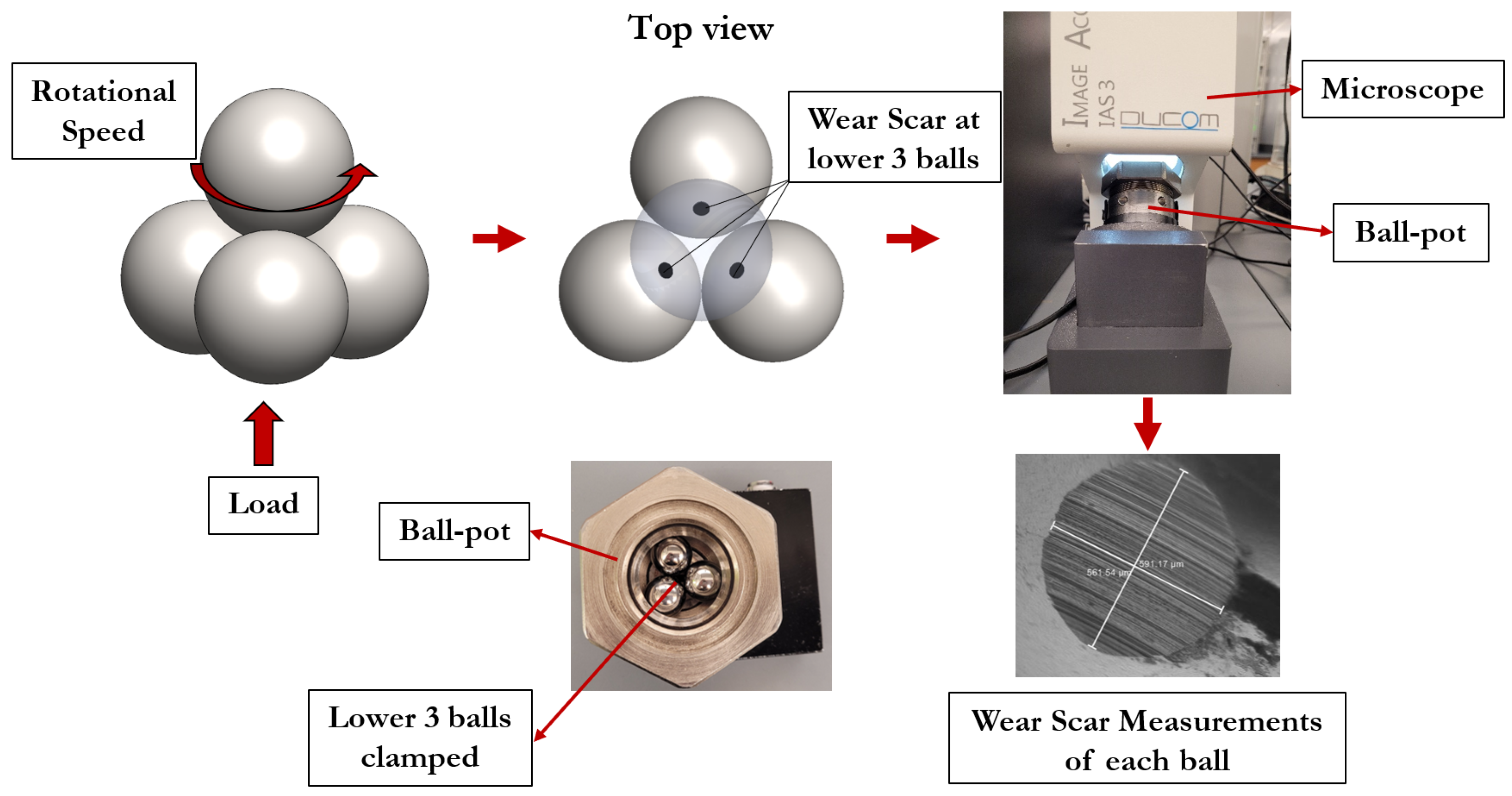

Wear evaluation was conducted in accordance with ASTM D4172, Standard Test Method for Wear Preventive Characteristics of Lubricating Fluid (Four-Ball Method) [

19]. Upon completion of each 60 min test, the three stationary lower balls were removed as a clamped assembly and examined using a calibrated optical microscope with a resolution of 0.01 µm. The overall procedure for wear assessment is illustrated schematically in

Figure 3.

(1) Scar formation. During operation, sliding contact at the three Hertzian points produces circular or slightly elliptical wear scars on the stationary balls. These scars serve as a direct measure of the lubricant’s wear-preventive performance.

(2) Measurement protocol. In accordance with ASTM D4172, two perpendicular scar diameters are measured for each ball: one along a radial axis from the center of the ball holder, and the second oriented at 90° to the first. For ball i, these diameters are denoted as and .

(3) Per-ball average. The average scar diameter for each ball is:

(4) Test-average WSD. The reported wear scar diameter (WSD) for the test is then calculated as the arithmetic mean of all three ball averages:

Equivalently, Equation (

8) may be expressed directly from the six raw measurements as:

(5) Precision and reproducibility. ASTM D4172 reports that the repeatability of this method is 0.12 mm and the reproducibility across laboratories is 0.28 mm, establishing confidence in the reliability of WSD values as a comparative metric for lubricant performance.

2.4. Lubricants

The study focused on critical lubricant properties known to influence tribological performance: viscosity, density, viscosity index (VI), and pressure-viscosity coefficient (PVC). These parameters play pivotal roles in film formation, load-bearing capacity, and the reduction of friction and wear under varying operating conditions.

Viscosity measurements were performed using an Ares G2 Rheometer in a parallel plate configuration, with temperature serving as the independent variable. All measurements were performed at temperatures corresponding to those used during tribological testing to ensure the relevance and accuracy of the data. Density, viscosity index, and pressure-viscosity coefficient values were sourced from established literature and standardized databases, providing comprehensive coverage across varying temperature ranges for each lubricant [

1]. A summary of the lubricant properties is presented in

Table 1.

2.5. Additives

To evaluate the impact of additives on tribological performance, various additives were incorporated into the base oils at different concentrations. These included hexagonal boron nitride (h-BN), silver (Ag), magnesium oxide (MgO), metallurgical coke–derived flash graphene (MCFG), and waste plastic–derived flash graphene (WPFG). Each additive contributes uniquely to friction and wear reduction through mechanisms such as surface film formation, load-bearing reinforcement, or interfacial shearing. The nomenclature of the graphene-based additives (MCFG and WPFG) reflects their respective sources: metallurgical coke and waste plastic precursors used in the flash graphene synthesis process.

The study specifically investigated the effects of additive concentration, particle size, and hardness on the coefficient of friction (COF) and wear scar diameter (WSD). Experimental results provide critical insights into the complex interactions between additives and base oils, as well as their collective influence on tribological performance. Additive properties are summarized in

Table 2, while the combinations of lubricants and additives are detailed in

Table 3.

2.6. Operating Conditions

The four-ball tester used in this study is equipped with high-precision sensors and advanced control systems, enabling precise control and real-time monitoring of operating parameters. Each test was conducted for a duration of one hour, with data captured at one-second intervals to generate high-resolution time-series datasets. This temporal resolution is critical for accurately capturing transient tribological behaviors.

Key parameters monitored during the tests included temperature, applied load, and rotational speed. All signals were recorded at a frequency of 1 Hz, ensuring consistent temporal resolution across the dataset. These parameters were maintained within strict tolerances to guarantee experimental repeatability, while torque was simultaneously captured at the same frequency to enable real-time calculation of the coefficient of friction (COF).

As explained in

Section 2.3, WSD was measured at the conclusion of each test. To construct a time-resolved WSD profile for training the machine learning model, a linear relationship between WSD and time was assumed. This assumption is justified because all experiments were conducted within the proper operational regime, prior to lubricant failure or seizure. Desai et al. [

21] demonstrated that in this regime—characterized by stable lubrication conditions—wear progresses in a steady, linear manner, particularly after the initial run-in phase and before severe wear mechanisms dominate. The non-linear wear behavior reported in their study arises only after the onset of seizure, which was not reached under the conditions employed used in this study. Accordingly, by remaining in the stable regime, it is reasonable to approximate WSD as increasing linearly with time. Based on this assumption, a continuous wear progression curve was extrapolated from the final WSD measurement, allowing the model to capture temporal wear trends in conjunction with frictional data.

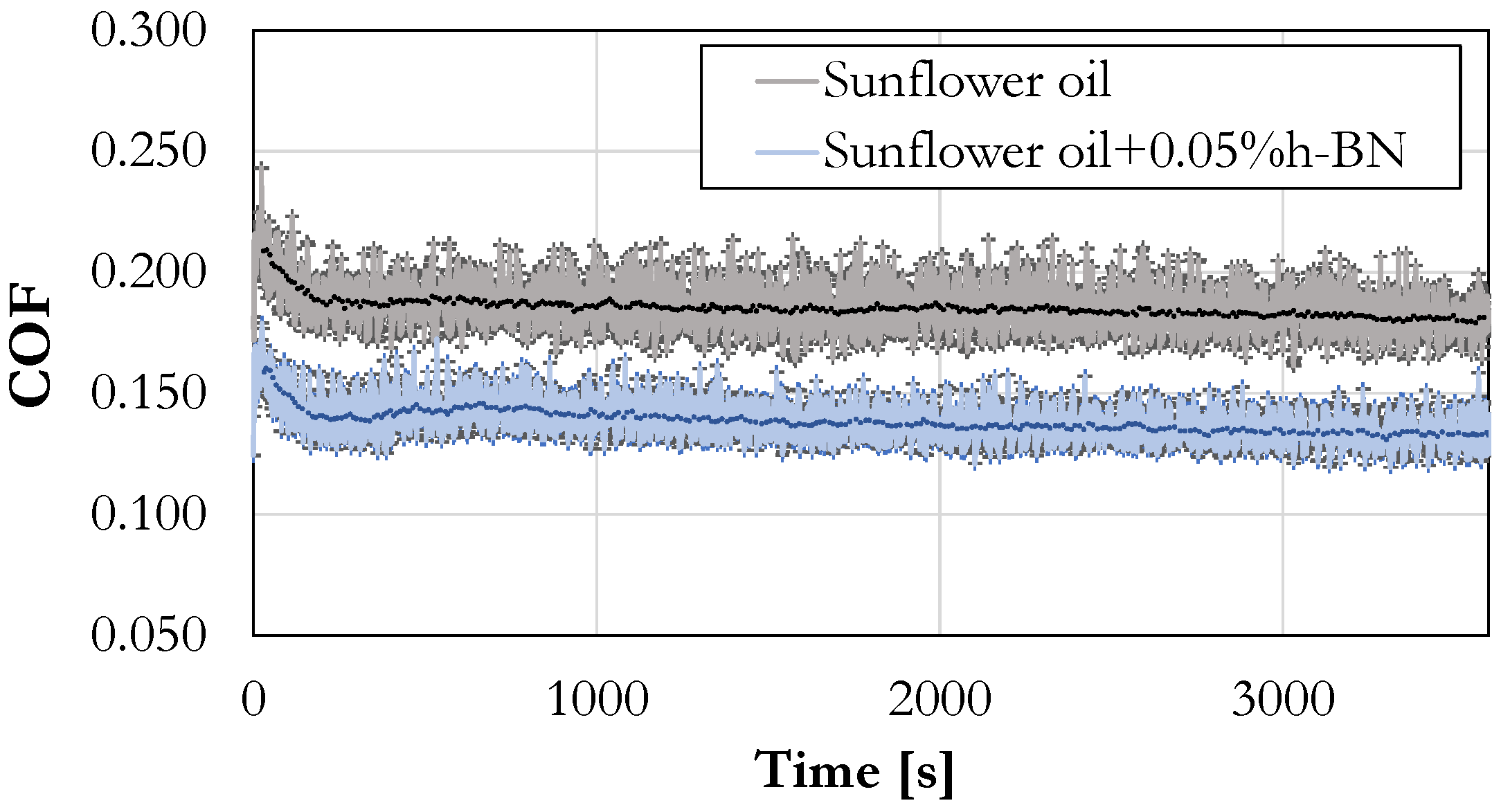

Figure 4 presents an example of the COF evolution over time for base sunflower oil and sunflower oil containing 0.05 wt% hexagonal boron nitride (h-BN) additive. This representative curve highlights the dynamic tribological behavior of these lubricant formulations under controlled conditions. The time-resolved datasets obtained from these experiments were essential for training and validating the machine learning model, enabling the identification of complex, non-linear interactions within the tribosystem.

3. Experimental Results

To illustrate the structure and resolution of the experimental dataset used in this study, we present representative examples of the temporal evolution of the coefficient of friction (COF) and wear scar diameter (WSD) under different lubrication conditions. These examples are not intended as a comprehensive tribological assessment, but rather to demonstrate the nature of the data collected and the fidelity of the time-resolved measurements that serve as the foundation for the machine learning framework developed in this work.

It is important to note that the plots shown here are derived from single experimental runs and are presented solely as illustrative examples of the raw temporal data collected. The comprehensive tribological analyses, including averaged values and statistical treatment across replicates, have been reported in detail elsewhere. Specifically, the behavior of h-BN, Ag, and MgO nanoparticles in vegetable oils is presented in Granja et al. [

17], while the performance of PAO6 and PAO9 containing metallurgic coke–derived flash graphene (MCFG) and waste plastic–derived flash graphene (WPFG) is described in Advincula et al. [

18]. In the present work, these validated experimental results are systematically curated and integrated to construct a unified, high-resolution dataset suitable for supervised learning. The contribution of this study, therefore, lies not in re-reporting experimental outcomes, but in developing a predictive, data-driven framework that leverages these results within a machine learning–based modeling and deployment pipeline.

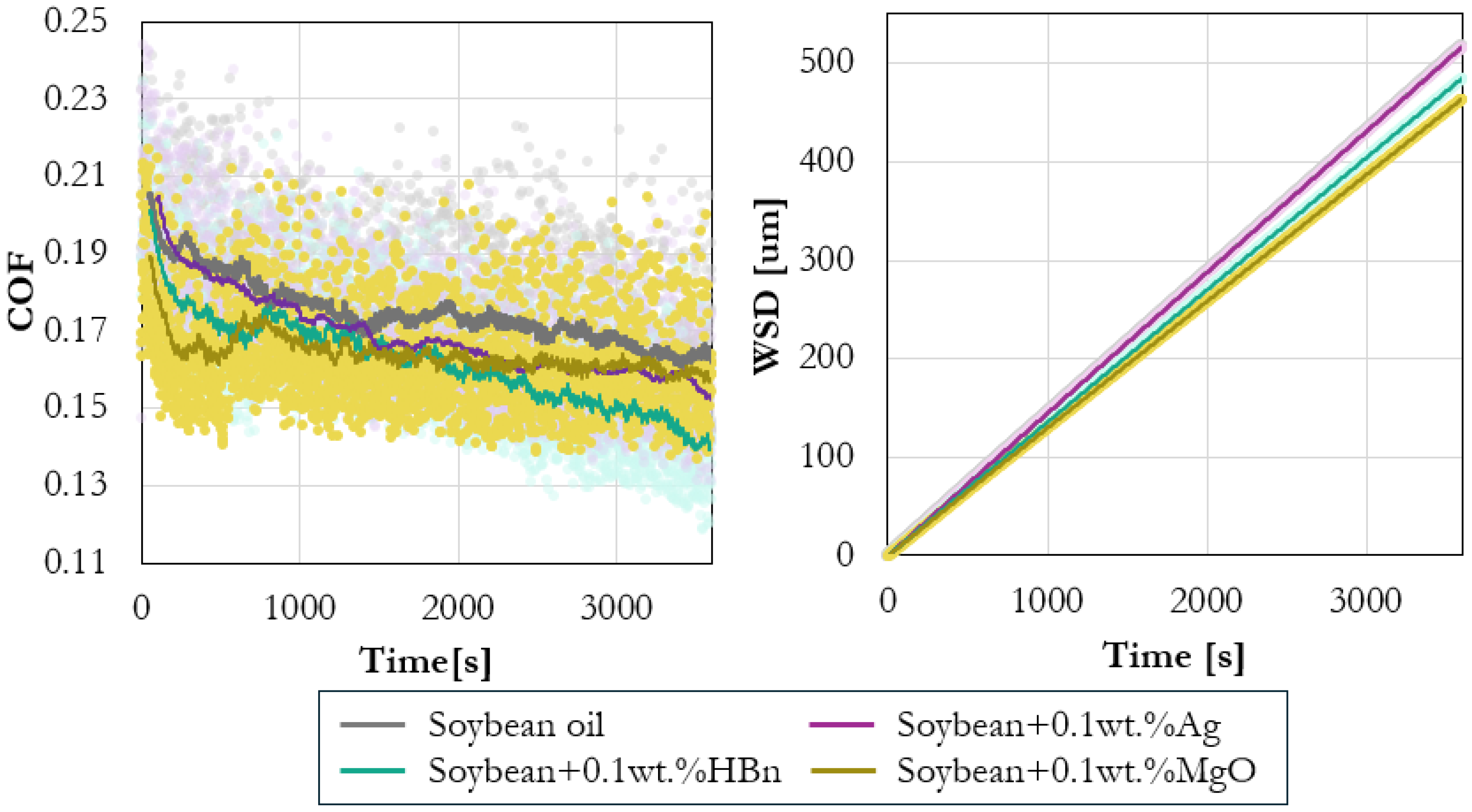

Figure 5 presents the evolution of the coefficient of friction (COF) and wear scar diameter (WSD) over time for four base lubricants: soybean oil, sunflower oil, PAO6, and PAO9. This example illustrates how the tribological response—both friction and wear—varies as a function of the selected base oil. As expected, the vegetable oils exhibit greater variability in friction compared to the synthetic PAOs, consistent with differences in viscosity–temperature behavior, polarity, and boundary lubrication properties [

22,

23].

To highlight the role of additives,

Figure 6 compares the tribological behavior of soybean oil containing 0.1 wt% of silver (Ag), hexagonal boron nitride (h-BN), or magnesium oxide (MgO) nanoparticles. While the effect is less pronounced than the differences observed between base oils, clear variations can still be seen in the evolution of COF and WSD depending on the additive employed. These differences are consistent with the distinct lubrication mechanisms typically associated with each additive—Ag as a surface-active modifier, h-BN as a lamellar solid lubricant, and MgO as an oxide-based stabilizer [

17,

24].

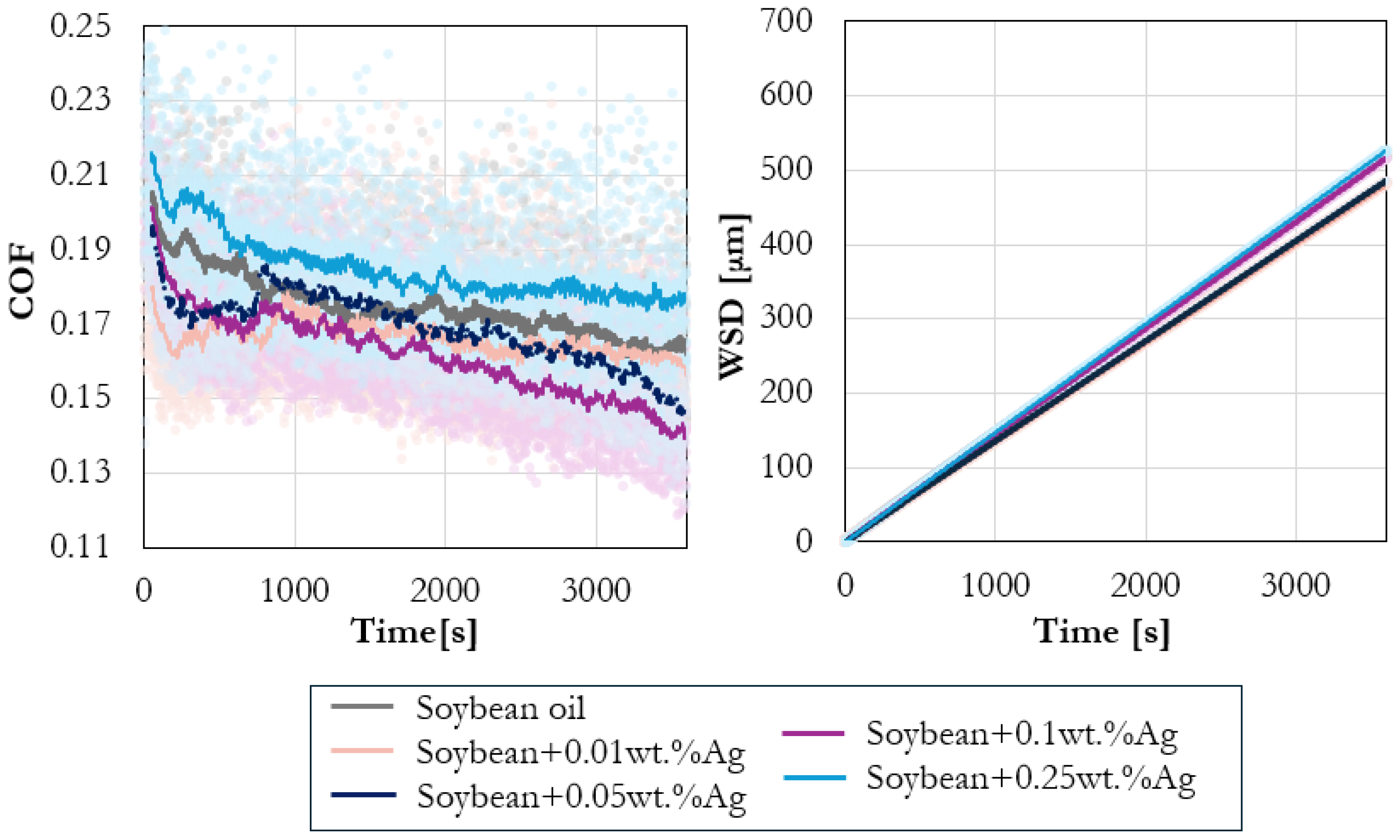

Finally,

Figure 7 illustrates the influence of additive concentration by showing the evolution of COF and WSD for soybean oil containing Ag nanoparticles at 0.01, 0.05, 0.10, and 0.25 wt%. This example highlights the concentration-dependent variability in nanoparticle additives: very low concentrations may provide insufficient surface coverage, whereas higher loadings can promote agglomeration or abrasive effects. As a result, the tribological response of both friction and wear does not vary monotonically with concentration [

25].

4. Data-Driven Modeling

4.1. Data Matrix

The dataset used for model development was derived directly from four-ball tribological experiments. A total of 36 distinct lubricant–additive formulations were evaluated, each tested in triplicate, resulting in 108 independent experiments. The COF and WSD were recorded as functions of time, concurrently with material properties and operating conditions, with all signals sampled at 1 Hz for 3600 s. In total, this procedure yielded individual training instances, forming a large-scale supervised learning dataset.

Each training instance is defined by a set of input features that describe operating conditions, lubricant properties, and additive characteristics, while the outputs correspond to the tribological responses (COF and WSD). A representative example of the input–output structure of a training instance is presented in

Table 4.

The dataset can be summarized as follows:

Total number of features (n): 13

Input features (d): 11

Output features (q): 2 (COF and WSD)

Training examples (m): 388,800

All raw experimental data were exported from the four-ball tester as individual csv files and subsequently merged into a unified dataset with a consistent column structure matching the defined input and output features. Empty or incomplete rows were removed prior to model training. To ensure balanced feature weighting and improve model convergence, all numerical variables were normalized using a MinMax scaling function to map their values to the [0, 1] range. This normalization enhanced numerical stability and allowed each feature to contribute comparably to the learning process.

For supervised regression, only the 11 input features are used to construct the data matrix. The two outputs serve as target variables for learning the nonlinear mapping from inputs to tribological responses.

The input data matrix

is defined as

where each column represents one training instance and each row corresponds to one input feature. Explicitly,

with

denoting the value of the

i-th feature for the

j-th training instance.

The corresponding output matrix

contains the two target variables:

Here, each column corresponds to the outputs of a single training instance. Together, Equations (

11) and (

12) define the supervised learning problem as learning a multi-output regression function

where

is the feature vector and

is the corresponding output. This formulation enables the neural network to capture nonlinear relationships between input features and tribological responses across the full experimental dataset.

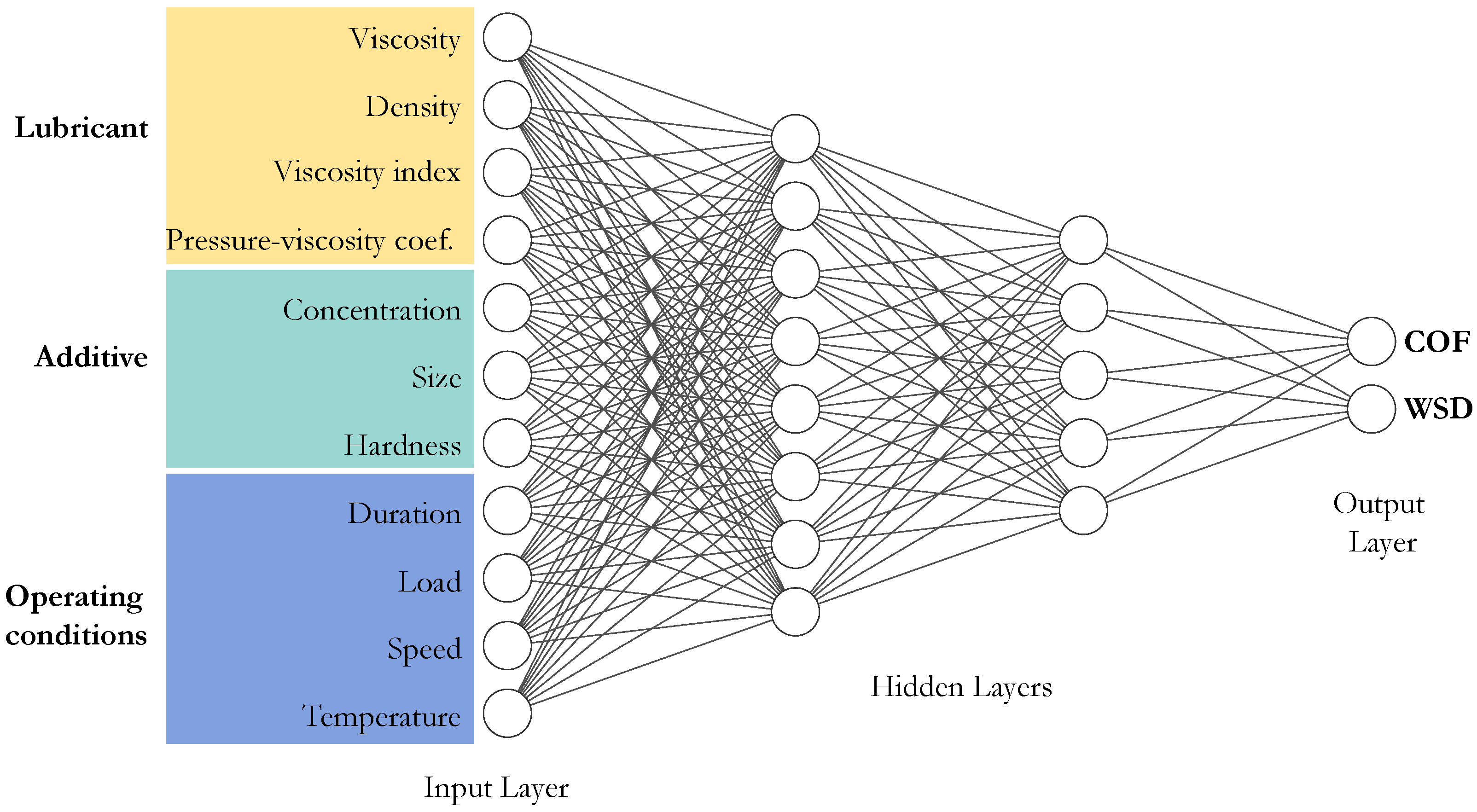

4.2. Neural Network Architecture

To model the tribological behavior of the system, a multilayer perceptron (MLP) neural network was implemented. The MLP is a type of feedforward artificial neural network composed of an input layer, one or more hidden layers, and an output layer. Each neuron in a layer is densely connected to every neuron in the subsequent layer. These connections carry weights that are iteratively updated during training to minimize the prediction error using a loss function. Non-linear activation functions are applied between layers, enabling the network to capture intricate patterns and non-linear relationships inherent in the tribological dataset.

In this study, the neural network processes experimental input variables—such as operating conditions, and the properties of lubricants and additives—to predict two key output quantities: the coefficient of friction (COF) and wear scar diameter (WSD). The architecture of the model, including the number of layers and neurons per layer, was selected on the basis of preliminary experiments and hyperparameter optimization to balance model complexity with generalization capability.

The complete structure of the neural network is depicted in

Figure 8, which illustrates the flow of information from the input layer through the hidden layers to the final output nodes. This architecture supports simultaneous regression of COF and WSD values, enabling joint learning of both outputs from shared tribological features.

Model performance is quantitatively evaluated using the coefficient of determination (R2) on both training and validation datasets. This metric assesses how well the predicted values align with the true values and serves as a measure of the model’s predictive accuracy and generalization capacity.

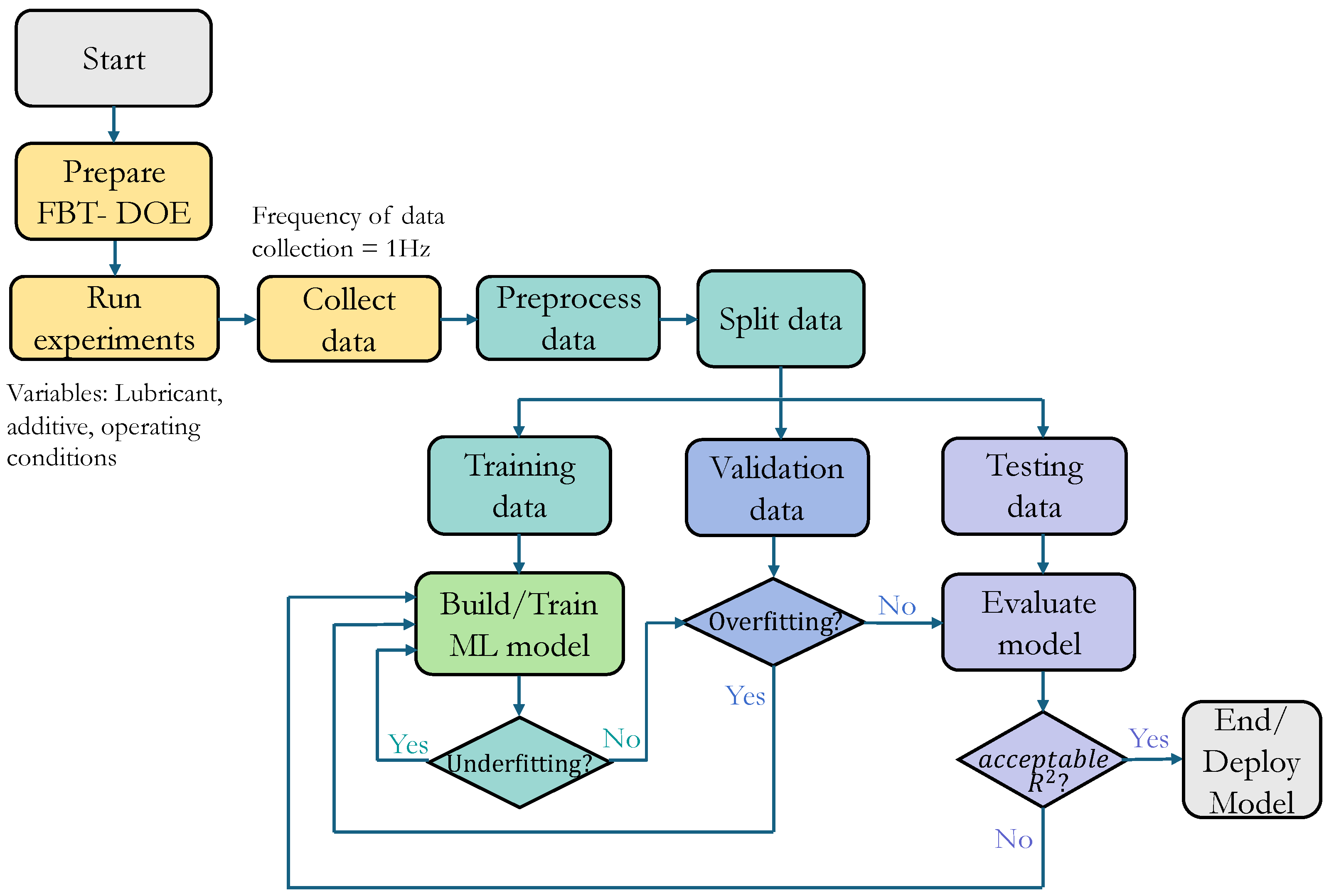

4.3. Model Training

The dataset is divided into three subsets: training, validation (development), and testing, using a 60-20-20 split ratio. The training set is used to optimize the model parameters and identify potential bias, which is typically associated with underfitting. Underfitting occurs when the model fails to capture underlying patterns in the data, often reflected by low performance on the training set. To address this, adjustments such as increasing network complexity or extending the training duration are implemented to improve the model’s learning capacity.

After addressing bias, the model is evaluated on the validation or development dataset to monitor its variance and generalization ability. High variance, indicative of overfitting, is identified when the model performs well on the training data but poorly on the validation data. To mitigate overfitting, techniques such as L2 regularization and data augmentation are applied. These strategies help prevent the model from memorizing training data and improve its robustness across unseen examples.

Once the model demonstrates stable and satisfactory performance on both training and validation sets, it is evaluated on the independent testing set. The coefficient of determination (R

2) is used as the primary performance metric. A threshold of 90% R

2 is established for model acceptance, based on an assumed Bayes error of 10%. This threshold accounts for the irreducible error inherent in experimental measurements, ensuring that the model’s predictions are within the bounds of experimental reproducibility and noise. An overview of the complete training workflow, including dataset partitioning, bias–variance evaluation, and model optimization steps, is illustrated in

Figure 9 for clarity.

The optimal MLP architecture consists of two hidden layers comprising 60 neurons in the first layer and 30 neurons in the second. The rectified linear unit (ReLU) activation function is employed to introduce non-linearity, enabling the network to model complex interactions among input features. To further enhance generalization, L2 regularization is applied with a penalty term (alpha) of 0.00001.

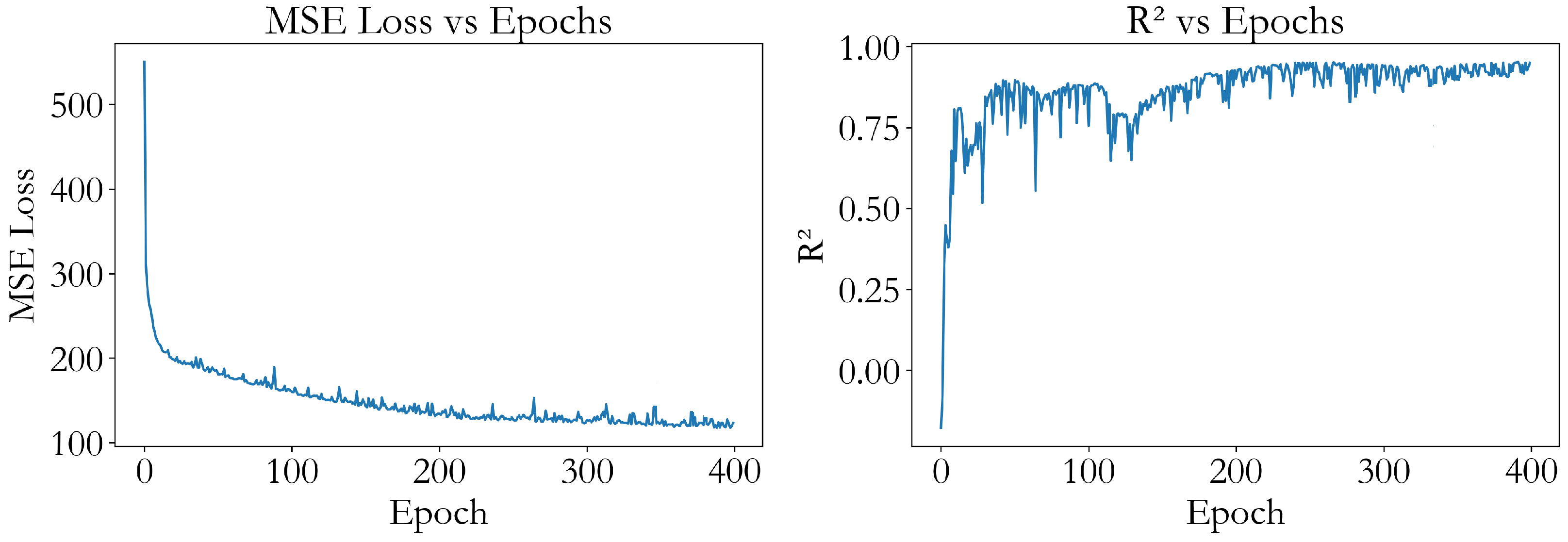

Model training was performed over a maximum of 400 iterations using a fixed initial learning rate. Adam optimization algorithm was selected for its ability to efficiently update weights and achieve rapid convergence. By integrating the strengths of both the Adaptive Gradient Algorithm (AdaGrad) and Root Mean Square Propagation (RMSProp), Adam is particularly well suited for handling sparse gradients and noisy datasets. The complete training process was completed in 18 min and 22 s.

To further illustrate the learning behavior of the network during optimization,

Figure 10 presents the evolution of the MSE loss and the corresponding R

2 coefficient across training epochs. The loss curve exhibits a steep initial decline during the first ∼40–60 epochs, indicating rapid improvement as the model begins capturing the dominant nonlinear relationships in the dataset. After this initial phase, the loss decreases more gradually and stabilizes, reflecting convergence toward a well-defined minimum without signs of divergence. Complementarily, the R

2 curve shows a monotonic increase over the same period, rising from negative values (indicating poor early predictions) to consistently high values (>0.85) as training progresses. This steady growth in predictive performance, coupled with the smooth reduction in loss, confirms that the optimization process was stable and effective, and that the model progressively refined its internal representation of the underlying tribological behavior. These training-epoch plots therefore demonstrate that the ANN achieved good convergence properties and did not exhibit either optimization instability or overfitting during training.

Collectively, the architectural design and training strategy enabled the MLP to learn the complex, nonlinear relationships inherent in the tribological dataset, resulting in robust and accurate predictions of both the coefficient of friction (COF) and wear scar diameter (WSD) across the range of experimental conditions.

5. Results and Discussion

The trained neural network demonstrated strong and consistent predictive performance across both outputs. For the coefficient of friction (COF), the model achieved an R2 of 0.8426 on the training set and 0.8425 on the testing set, together with very low errors (MAE ≈ 0.0167, RMSE ≈ 0.0215). For the wear scar diameter (WSD), the network obtained an excellent R2 of 0.9910 during training and 0.9903 on the testing set, with corresponding errors of MAE ≈ 7.44 µm and RMSE ≈ 15.84 µm. When evaluated across both outputs simultaneously, the model attained an overall coefficient of determination of , further confirming its ability to capture the dominant nonlinear relationships governing friction and wear. The close agreement between training and testing metrics, both at the individual-output level and in the aggregate, demonstrates that the framework generalized effectively without evidence of underfitting or overfitting. These results exceed the acceptance threshold derived from the estimated Bayes error and highlight the model’s capacity to reproduce tribological responses with good fidelity.

To rigorously assess the model’s predictive capability, it was evaluated on entirely unseen data: sunflower oil supplemented with 0.01 wt% silver (Ag) nanoparticles. Notably, no data related to this specific lubricant formulation were included in either the training or development datasets.

Figure 11 presents a comparison between the experimentally obtained COF and WSD curves over time and the model’s predictions. The strong agreement observed underscores the model’s robustness and its ability to generalize effectively to novel lubricant formulations, demonstrating its potential for broader applications in tribological performance prediction.

As a data-driven framework, the model performs most reliably within the parameter envelope represented in the training dataset. For instance, it can accurately predict the behavior of lubricants and additives whose viscosity, particle size, hardness, and density fall within the range of the studied systems. Nevertheless, the successful prediction of the Sunflower + Ag case confirms that the model captures physically meaningful patterns rather than memorized correlations, supporting its interpretability and generalization potential. Moreover, the model architecture is inherently scalable and can be retrained or fine-tuned as new data become available further enhancing its interpolation and extrapolation performance in future applications. This adaptability positions the framework as a foundation for developing intelligent, data-driven tools for tribological performance prediction and digital twin integration.

It is important to note that the present framework was developed using a simplified tribological system in which the chemical reactivity of additives and temperature-driven tribofilm formation were intentionally excluded. Additives such as zinc dialkyldithiophosphate (ZDDP), which are known to form protective tribofilms and substantially modify friction–wear behavior through surface chemistry, were not part of this study. This simplification enables the model to isolate and capture the physical contributions of base oils and solid nanoadditives—such as particle size, hardness, and density—to friction and wear responses under controlled mechanical conditions. While this approach bypasses the complex interactions associated with reactive additives, it establishes a clear and interpretable foundation upon which future data-driven frameworks can be expanded to incorporate fully tribochemical-dependent effects.

6. Conclusions

Artificial intelligence (AI), and more specifically machine learning (ML), holds significant promise for addressing the high-dimensional, nonlinear interactions that govern tribological systems. The prediction of friction and wear has traditionally relied on empirical approaches, as the underlying mechanisms are difficult to describe through fully deterministic mathematical models. The strong interdependence among operating conditions, lubricant properties, and tribological responses—such as the coefficient of friction (COF) and wear scar diameter (WSD)—necessitates data-driven methodologies capable of capturing complex nonlinear behavior.

In this study, a fully connected deep neural network was developed to predict the COF and WSD using experimental four-ball test data encompassing multiple base oils and nanoadditive chemistries. The trained model achieved an overall R2 of 91.6%, surpassing the acceptance threshold derived from the estimated Bayes error. When evaluated on an unseen lubricant–additive system (Sunflower oil with 0.01 wt% Ag), the model accurately reproduced the temporal evolution of both the COF and WSD, confirming its generalization capability and physical consistency. These results demonstrate the feasibility and robustness of deep learning as a predictive tool for tribological performance analysis and highlight its potential to complement and accelerate experimental workflows.

As a data-driven framework, the model performs most reliably within the experimental domain presented in the training dataset. Its predictive accuracy is therefore limited to lubricants, additives, and operating conditions with properties within the studied range. Nonetheless, the framework is inherently scalable: incorporating additional data from new lubricants, additive chemistries, or operating conditions would progressively expand its predictive domain. In particular, the addition of formulation-level descriptors and chemical composition information would enable the model to capture tribochemical interactions and additive-base oil synergies, thereby supporting a more complete representation of lubricant behavior.

This study demonstrates the successful development of a scalable, data-driven framework that explicitly integrates nanoadditive characteristics—such as particle size, density, and hardness—together with lubricant properties and operating parameters to predict tribological performance. To the authors’ knowledge, it represents the first implementation of a machine-learning model specifically designed for the four-ball tribological test, a well-known platform for benchmarking lubricant performance. By consolidating experimental datasets into a unified predictive framework, this work lays the foundation for developing data-driven tools for tribological performance prediction. This data-driven model also paves the way to generalized, multi-regime tribology frameworks that can guide new lubricant and tribosurface designs.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, V.G. and C.F.H.III; Methodology, V.G.; Software, V.G.; Validation, V.G.; Formal analysis, V.G.; Investigation, V.G.; Resources, C.F.H.III; Data curation, V.G.; Writing—original draft, V.G.; Writing—review & editing, V.G. and C.F.H.III; Visualization, V.G.; Supervision, C.F.H.III; Project administration, C.F.H.III; Funding acquisition, C.F.H.III. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Nomenclature

| t | Time [s] |

| Applied vertical load by the tester [N] |

| T | Temperature [°C] |

| Rotational speed [rpm] |

| PVC | Pressure–viscosity coefficient |

| VI | Viscosity Index |

| Dynamic viscosity of the lubricant [cSt] |

| Density of lubricant [kg/m3] |

| wt | Additive weight percentage [%] |

| Size | Additive nanoparticle size [nm] |

| HR | Hardness rating of the material |

| h-BN | Hexagonal boron nitride |

| Ag | Silver |

| MgO | Magnesium oxide |

| MCFG | Metallurgical coke–derived flash graphene |

| WPFG | Waste plastic–derived flash graphene |

| COF | Coefficient of Friction (dimensionless) |

| WSD | Wear Scar Diameter [µm] |

| Measured frictional torque [N·m] |

| Inclination angle of contact normal ( for four-ball geometry) |

| Normal load at a single ball–ball contact [N] |

| Total normal load across all three contacts [N] |

| Effective friction radius [m] |

| Total tangential friction force [N] |

| P | Applied vertical load (instrument input) [N] |

| Orthogonal scar diameters on the ball [μm] |

| Average scar diameter for the ball [μm] |

| WSD | Final average wear scar diameter over all three balls [μm] |

| n | Total number of features (13: 11 input + 2 output) |

| d | Number of input features (11) |

| q | Number of output features (2: COF and WSD) |

| m | Total number of training instances (388,800) |

| Raw data matrix, |

| Input feature matrix, |

| Output matrix with COF and WSD, |

| Value of the input feature in the training instance |

| Output vector (COF, WSD) for the instance |

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| ML | Machine Learning |

| NN | Neural Network |

| MLP | Multi-Layer Perceptron |

References

- Czichos, H. Tribology: A Systems Approach to the Science and Technology of Friction, LUBRICATION, and Wear; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2009; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Stachowiak, G.W.; Batchelor, A.W. Engineering Tribology; Butterworth-Heinemann: Woburn, MA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Bhushan, B. Introduction to Tribology; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Persson, B.N.J. Sliding Friction: Physical Principles and Applications; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Archard, J.F. Contact and rubbing of flat surfaces. J. Appl. Phys. 1953, 24, 981–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutchings, I.M.; Shipway, P. Tribology: Friction and Wear of Engineering Materials; Butterworth-Heinemann: Woburn, MA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Sose, A.T.; Joshi, S.Y.; Kunche, L.K.; Wang, F.; Deshmukh, S.A. A review of recent advances and applications of machine learning in tribology. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2023, 25, 4408–4443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marian, M.; Tremmel, S. Recent Advances in Machine Learning in Tribology. Lubricants 2021, 9, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, R.; Jaramillo, R.; Thomas, G.; Rayhan, T.; Hossain, N.; Kchaou, M.; Profito, F.J.; Rosenkranz, A. Artificial intelligence and machine learning in tribology: Selected case studies and overall potential. Adv. Eng. Mater. 2025, 2401944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paturi, U.M.R.; Palakurthy, S.T.; Reddy, N.S. The role of machine learning in tribology: A systematic review. Arch. Comput. Methods Eng. 2023, 30, 1345–1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenkranz, A.; Marian, M.; Profito, F.J.; Aragon, N.; Shah, R. The use of artificial intelligence in tribology—A perspective. Lubricants 2020, 9, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolev, M.; Petkov, V.; Petkov, V.; Dimitrova, R.; Uzun, S.; Krastev, B. Wear Characterization and Coefficient of Friction Prediction Using a Convolutional Neural Network Model for Chromium-Coated SnSb11Cu6 Alloy. Lubricants 2025, 13, 200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shabana, S.; Jatavallabhula, J.K.; Kumar, R.N.; Chinthalapudi, R.; Pappula, B. Towards Intelligent Tribology: Predicting Wear and Friction in WC–Co Coatings with Machine Learning. J. Bio- Tribo-Corros. 2025, 11, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, M.S.; Kordijazi, A.; Rohatgi, P.K.; Nosonovsky, M. Triboinformatic Modeling of Dry Friction and Wear of Aluminum Base Alloys Using Machine Learning Algorithms. Tribol. Int. 2021, 161, 107065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, M.S.; Kordijazi, A.; Rohatgi, P.K.; Nosonovsky, M. Triboinformatics Approach for Friction and Wear Prediction of Al–Graphite Composites Using Machine Learning Methods. J. Tribol. 2022, 144, 011701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Li, Y.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, C.; Zhao, Y.; Yan, X. Prediction Model for Bearing Surface Friction Coefficient in Bolted Joints Based on GA–BP Neural Network and Experimental Data. Tribol. Int. 2025, 201, 110217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granja, V.; Jogesh, K.; Taha-Tijerina, J.; Higgs, C.F., III. Tribological Properties of h-BN, Ag and MgO Nanostructures as Lubricant Additives in Vegetable Oils. Lubricants 2024, 12, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Advincula, P.A.; Granja, V.; Wyss, K.M.; Algozeeb, W.A.; Chen, W.; Beckham, J.L.; Luong, D.X.; Higgs, C.F., III; Tour, J.M. Waste plastic-and coke-derived flash graphene as lubricant additives. Carbon 2023, 203, 876–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM D4172-18; Standard Test Method for Wear Preventive Characteristics of Lubricating Fluid (Four-Ball Method). ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2018. [CrossRef]

- ASTM D5183-05(2016); Standard Test Method for Determination of the Coefficient of Friction of Lubricants Using the Four-Ball Wear Test Machine. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2016. [CrossRef]

- Desai, P.S.; Granja, V.; Higgs, C.F., III. Lifetime prediction using a tribology-aware, deep learning-based digital twin of ball bearing-like tribosystems in oil and gas. Processes 2021, 9, 922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burkhart, C.; Johansson, J.; Ukonsaari, J.; Prakash, B. Performance of lubricating oils for wind turbine gear boxes and bearings. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part J J. Eng. Tribol. 2018, 232, 62–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owuna, F.J. Stability of vegetable-based oils used in the formulation of ecofriendly lubricants: A review. Egypt. J. Pet. 2020, 29, 251–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulzar, M.; Masjuki, H.H.; Kalam, M.A.; Varman, M.; Zulkifli, N.W.M.; Mufti, R.A.; Zahid, R. Tribological performance of nanoparticles as lubricating oil additives. J. Nanopart. Res. 2016, 18, 223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Chauhan, P.; Mamatha, T.G. A review on tribological performance of lubricants with nanoparticle additives. Mater. Today Proc. 2020, 25, 586–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Four-ball tester used for data collection.

Figure 1.

Four-ball tester used for data collection.

Figure 2.

Schematic of the COF calculation for a four-ball tester, showing the tetrahedral contact geometry. Left: load application on the spinning upper ball and three stationary lower balls. Center: decomposition of the applied load into contact normals at an inclination angle of 35.2644°. Right: top view illustrating the effective friction radius mm, torque , and the relationship .

Figure 2.

Schematic of the COF calculation for a four-ball tester, showing the tetrahedral contact geometry. Left: load application on the spinning upper ball and three stationary lower balls. Center: decomposition of the applied load into contact normals at an inclination angle of 35.2644°. Right: top view illustrating the effective friction radius mm, torque , and the relationship .

Figure 3.

Workflow for wear measurement in the four-ball test. Left: applied load and rotational motion generate sliding contacts between the upper rotating ball and the three stationary balls. Middle, top: wear scars form on the stationary balls at the contact points (top view). Middle, bottom: Image of the actual experimental setup, showing the three lower balls clamped together in the ball pot (top view). Right, top: the clamped ball-pot is transferred directly to a microscope for optical inspection without disturbing the assembly. Right, bottom: two perpendicular diameters are measured for each scar, and the average wear scar diameter (WSD) is computed from the six measurements according to ASTM D4172.

Figure 3.

Workflow for wear measurement in the four-ball test. Left: applied load and rotational motion generate sliding contacts between the upper rotating ball and the three stationary balls. Middle, top: wear scars form on the stationary balls at the contact points (top view). Middle, bottom: Image of the actual experimental setup, showing the three lower balls clamped together in the ball pot (top view). Right, top: the clamped ball-pot is transferred directly to a microscope for optical inspection without disturbing the assembly. Right, bottom: two perpendicular diameters are measured for each scar, and the average wear scar diameter (WSD) is computed from the six measurements according to ASTM D4172.

Figure 4.

Evolution of the coefficient of friction over time for base sunflower oil and sunflower oil with 0.05 wt% h-BN additive, obtained from four-ball tester experiments.

Figure 4.

Evolution of the coefficient of friction over time for base sunflower oil and sunflower oil with 0.05 wt% h-BN additive, obtained from four-ball tester experiments.

Figure 5.

Representative evolution of coefficient of friction (COF) and wear scar diameter (WSD) over time for four base oils: soybean, sunflower, PAO6, and PAO9. Colored dots represent raw time-resolved experimental measurements from individual tests, while the solid lines correspond to moving-average trends used to highlight the underlying temporal behavior. The plots illustrate differences between vegetable-based and synthetic lubricants.

Figure 5.

Representative evolution of coefficient of friction (COF) and wear scar diameter (WSD) over time for four base oils: soybean, sunflower, PAO6, and PAO9. Colored dots represent raw time-resolved experimental measurements from individual tests, while the solid lines correspond to moving-average trends used to highlight the underlying temporal behavior. The plots illustrate differences between vegetable-based and synthetic lubricants.

Figure 6.

Representative evolution of COF and WSD in soybean oil with 0.1 wt% of different nanoparticle additives: silver (Ag), hexagonal boron nitride (h-BN), and magnesium oxide (MgO). Distinct additive chemistries lead to unique friction- and wear-reduction mechanisms. Dots and solid lines represent raw experimental data and corresponding moving-average trends, respectively.

Figure 6.

Representative evolution of COF and WSD in soybean oil with 0.1 wt% of different nanoparticle additives: silver (Ag), hexagonal boron nitride (h-BN), and magnesium oxide (MgO). Distinct additive chemistries lead to unique friction- and wear-reduction mechanisms. Dots and solid lines represent raw experimental data and corresponding moving-average trends, respectively.

Figure 7.

Representative evolution of COF and WSD in soybean oil containing silver nanoparticles (Ag) at different concentrations (0.01, 0.05, 0.10, and 0.25 wt%). Results highlight the non-monotonic dependence of tribological performance on additive loading. Dots show raw data; solid lines indicate moving-average trends.

Figure 7.

Representative evolution of COF and WSD in soybean oil containing silver nanoparticles (Ag) at different concentrations (0.01, 0.05, 0.10, and 0.25 wt%). Results highlight the non-monotonic dependence of tribological performance on additive loading. Dots show raw data; solid lines indicate moving-average trends.

Figure 8.

Neural Network Architecture for Predicting COF and WSD in Lubricated Four-Ball Tribo-Tests.

Figure 8.

Neural Network Architecture for Predicting COF and WSD in Lubricated Four-Ball Tribo-Tests.

Figure 9.

Workflow of the model training process, including data partitioning, model optimization, and evaluation stages.

Figure 9.

Workflow of the model training process, including data partitioning, model optimization, and evaluation stages.

Figure 10.

Evolution of the training loss (MSE) and coefficient of determination (R2) across training epochs, illustrating the convergence behavior of the neural network.

Figure 10.

Evolution of the training loss (MSE) and coefficient of determination (R2) across training epochs, illustrating the convergence behavior of the neural network.

Figure 11.

Comparison of experimental COF and WSD progression over time with model predictions for Sunflower oil with 0.01 wt% Ag.

Figure 11.

Comparison of experimental COF and WSD progression over time with model predictions for Sunflower oil with 0.01 wt% Ag.

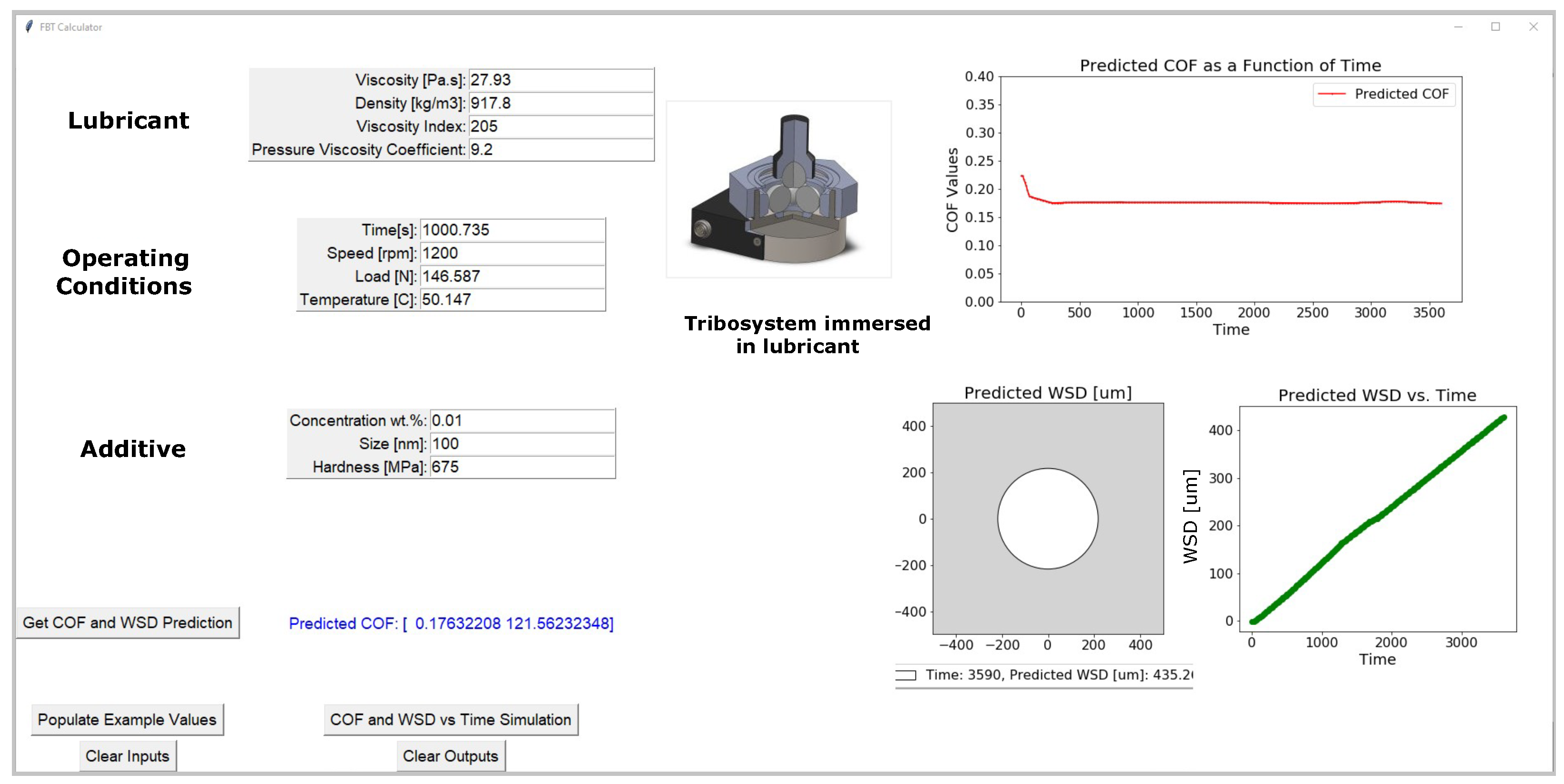

Figure 12.

Example of GUI output showing predicted COF and WSD evolution over time for user-specified inputs.

Figure 12.

Example of GUI output showing predicted COF and WSD evolution over time for user-specified inputs.

Table 1.

Thermophysical properties of base lubricants across various temperatures.

Table 1.

Thermophysical properties of base lubricants across various temperatures.

| Lubricant | 20 °C | 40 °C | 60 °C | 80 °C | VI | PVC |

|---|

| [cst] | [kg/m3] | [cst] | [kg/m3] | [cst] | [kg/m3] | [cst] | [kg/m3] | [-] | [GPa−1] |

|---|

| PAO6 | 26.3 | 823 | 11.2 | 805 | 5.1 | 788 | 2.6 | 771 | 137 | 0.476 |

| PAO9 | 73.1 | 849.3 | 29.8 | 823.8 | 13.4 | 795.1 | 7.19 | 762.8 | 149 | 0.0032 |

| Soybean | 85 | 920 | 45 | 900 | 25 | 870 | 15 | 840 | 60–90 | 0.5–1.5 |

| Sunflower | 65.6 | 920 | 29.5 | 896 | 14.2 | 871 | 8.04 | 844.6 | 90–100 | 1 |

Table 2.

Physical and mechanical properties of lubricant additives.

Table 2.

Physical and mechanical properties of lubricant additives.

| Additive | Size [nm] | HR [MPa] | [kg/m3] |

|---|

| h-BN | 300–400 | 660–3000 | 2100 |

| Ag | 100 | 250–1100 | 10,490 |

| MgO | 50 | 5000–7000 | 3600 |

| MCFG | 780.6 | 130,000 | 2267 |

| WPFG | 21.3 | 130,000 | 2267 |

Table 3.

Formulations of lubricant mixtures with corresponding additive concentrations.

Table 3.

Formulations of lubricant mixtures with corresponding additive concentrations.

| Base Lubricant | Additive | Concentration (wt%) |

|---|

| PAO6 | MCFG | 0.1, 0.2, 0.5 |

| WPFG | 0.1, 0.2, 0.5 |

| PAO9 | MCFG | 0.1, 0.2, 0.5 |

| WPFG | 0.1, 0.2, 0.5 |

| Sunflower | h-BN | 0.01, 0.05, 0.1, 0.25 |

| MgO | 0.01, 0.05, 0.1, 0.25 |

| Ag | 0.01, 0.05, 0.1, 0.25 |

| Soybean | h-BN | 0.01, 0.05, 0.1, 0.25 |

| MgO | 0.01, 0.05, 0.1, 0.25 |

| Ag | 0.01, 0.05, 0.1, 0.25 |

Table 4.

Representative training instance illustrating the structure of input features and output targets.

Table 4.

Representative training instance illustrating the structure of input features and output targets.

| t [s] | [N] | T [°C] | [rpm] | [cst] | PVC | VI | [kg/m3] | wt [%] | Size [nm] | HR | COF | WSD |

|---|

| 2000.3 | 139.0 | 50 | 1200 | 27.93 | 9.2 | 205 | 917.8 | 0.01 | 100 | 675 | 0.187 | 231.66 |

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |