Abstract

Lubricant condition analysis is a valuable diagnostic tool for assessing engine performance and ensuring the reliable operation of diesel engines. While traditional diagnostic techniques—such as Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR)—are constrained by slow response times, high costs, and the need for specialized personnel. In contrast, dielectric spectroscopy, impedance analysis, and soft computing offer real-time, non-destructive, and cost-effective alternatives. This review examines recent advances in integrating these techniques to predict lubricant properties, evaluate wear conditions, and optimize maintenance scheduling. In particular, dielectric and impedance spectroscopies offer insights into electrical properties linked to oil degradation, such as changes in viscosity and the presence of wear particles. When combined with soft computing algorithms, these methods enhance data analysis, reduce reliance on expert interpretation, and improve predictive accuracy. The review also addresses challenges—including complex data interpretation, limited sample sizes, and the necessity for robust models to manage variability in real-world operations. Future research directions emphasize miniaturization, expanding the range of detectable contaminants, and incorporating multi-modal artificial intelligence to further bolster system robustness. Collectively, these innovations signal a shift from reactive to predictive maintenance strategies, with the potential to reduce costs, minimize downtime, and enhance overall engine reliability. This comprehensive review provides valuable insights for researchers, engineers, and maintenance professionals dedicated to advancing diesel engine lubricant monitoring.

1. Introduction

In diesel engines, monitoring oil condition is essential for ensuring the longevity, efficiency, and reliability of internal combustion systems. Lubricants play a critical role in reducing friction, managing heat, and preventing wear [1,2,3]. However, the degradation of oil—driven by factors such as fuel type, operating conditions, and additive interactions—can lead to reduced fuel efficiency, increased emissions, and accelerated wear [4,5,6,7,8]. Traditional analysis methods, including Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR), are widely used to evaluate oil condition by detecting contaminants and measuring key properties such as viscosity and total base number (TBN), a measure of oil’s ability to neutralize acidic byproducts [9,10]. Despite their effectiveness, these techniques require specialized expertise, considerable time, and significant financial resources, limiting their practicality in many applications [11,12,13].

Advanced techniques such as impedance spectroscopy, dielectric analysis, and soft computing have emerged as promising solutions to the limitations of traditional oil analysis methods. Dielectric spectroscopy measures a lubricant’s electrical permittivity (ability to store energy in an electric field) and dielectric loss (energy dissipation), which correlate with degradation. Impedance analysis evaluates resistance to alternating current, reflecting conductivity changes due to contaminants. Soft computing (e.g., neural networks) applies AI to interpret complex data patterns, enabling predictive maintenance. Specifically, impedance [14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23] and dielectric [24,25,26] spectroscopy offer non-destructive, cost-effective, and highly precise means to assess the electrical properties of lubricants, which closely reflect their physical and chemical states. Soft computing approaches—including genetic algorithms, artificial neural networks (ANNs), and support vector machines (SVMs) [27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34]—leverage artificial intelligence and machine learning to interpret complex datasets, thereby reducing reliance on expert input and enhancing the accuracy of oil property predictions. Moreover, the integration of soft computing with impedance and dielectric techniques has demonstrated strong correlations between electrical characteristics and oil contaminants [13,35,36,37,38,39,40]. In this review, we critically examine these studies [13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40].

Transitioning from reactive to proactive, condition-based maintenance has underscored the critical importance of real-time, continuous monitoring of lubricant condition [41]. In situ measurements, which facilitate early detection of potential issues, combined with electrical techniques such as impedance and dielectric spectroscopy, can significantly reduce downtime and costly repairs [42,43]. Moreover, advances in multi-sensor data fusion and smart sensor systems have enabled real-time assessment of lubricant quality, estimation of remaining oil life, and a reduction in environmental impact [44,45,46]. Given that machine breakdowns can lead to serious safety hazards and substantial financial losses [47,48,49,50], these innovations are particularly valuable in sectors such as energy production, automotive, and aerospace. Despite these advancements, challenges remain in fully harnessing the potential of impedance, dielectric, and soft computing approaches for engine oil condition monitoring. Further research is warranted to address issues such as complex data interpretation, the development of robust models for limited datasets, and the integration of these techniques into existing maintenance platforms [51]. Moreover, since the relationships between specific lubricant components and their electrical properties may not exhibit straightforward linear behavior, more sophisticated models will be required to accurately predict oil condition [52].

This review examines the combined application of impedance spectroscopy, dielectric analysis, and soft computing in engine oil condition monitoring. We assess the practical utility of these techniques in forecasting lubricant properties, detecting wear conditions, and optimizing maintenance schedules by critically evaluating recent research and advancements. The article also addresses the challenges and future directions in this field, underscoring the potential of these methods to transform oil monitoring and contribute to the development of more reliable and efficient mechanical systems. Through this investigation, we aim to provide researchers, engineers, and maintenance professionals with valuable insights that pave the way for further advancements in lubricant condition monitoring.

2. Review Process

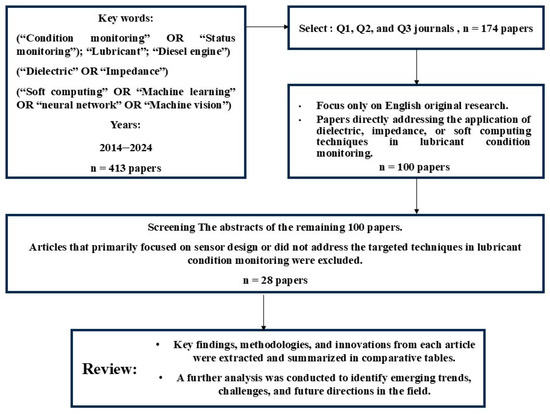

A systematic research strategy was implemented to ensure a thorough examination of the most relevant literature (see Figure 1). The methodology comprised the following steps:

Figure 1.

A flowchart of the selection procedure for our review.

- A.

- Keyword Search and Initial Screening

- A literature search was performed using the following keywords:

- -

- (“Condition monitoring” OR “Status monitoring”); “Lubricant”; “Diesel engine”

- -

- (“Dielectric” OR “Impedance”)

- -

- (“Soft computing” OR “Machine learning” OR “neural network” OR “Machine vision”)

- To capture current developments, the search was limited to publications from 2014 to 2024.

- Restricting the results to Q1, Q2, and Q3 journals yielded an initial pool of 413 articles, from which 174 were retained.

- B.

- Exclusion Criteria

- Review articles and non-English publications were excluded to focus exclusively on original research studies.

- Articles not directly addressing the application of dielectric, impedance, or soft computing techniques in lubricant condition monitoring were also removed.

- After applying these criteria, approximately 100 articles remained for further analysis.

- C.

- Abstract Review and Final Selection

- The abstracts of the remaining 100 articles were carefully reviewed to assess their relevance to the study’s objectives.

- Articles that primarily focused on sensor design or did not address the targeted techniques in lubricant condition monitoring were excluded.

- This process resulted in the final selection of 28 articles that fit precisely within the study framework and offered valuable insights into the application of these technologies in diesel engine lubricant monitoring.

- D.

- Data Extraction and Analysis

- The 28 selected articles (see Table 1) were categorized based on their focus on dielectric, impedance, or soft computing.

- Key findings, methodologies, and innovations from each article were extracted and summarized in comparative tables.

- A further analysis was conducted to identify emerging trends, challenges, and future directions in the field.

- E.

- Synthesis and Review

- A comprehensive synthesis of the extracted data has yielded an extensive overview of recent advancements in dielectric, impedance, and soft computing techniques for lubricant condition monitoring.

- The analysis highlights the potential of these methods to facilitate real-time, predictive maintenance, while also examining current limitations and opportunities for future research.

The systematic review of 28 studies (see Table 1) provides a foundation for evaluating the efficacy of impedance spectroscopy, dielectric analysis, and soft computing in lubricant monitoring, as detailed in the following sections. This review is intended to serve as a valuable resource for technicians, engineers, and maintenance professionals seeking to enhance engine reliability and performance through advanced monitoring technologies.

Table 1.

Classification of articles studied in this research.

Table 1.

Classification of articles studied in this research.

| No. | Main Idea | Journal | Quartiles | Publish Year | Ref. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dielectric | Impedance | Soft Computing | |||||

| 1 | * | * | Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical | Q1 | 2014 | [36] | |

| 2 | * | International Journal of Electrochemical Science | Q3 | 2015 | [15] | ||

| 3 | * | Tribology International | Q1 | 2017 | [27] | ||

| 4 | * | Tribology international | Q1 | 2018 | [24] | ||

| 5 | * | * | Measurement | Q1 | 2019 | [13] | |

| 6 | * | IET Science, Measurement & Technology | Q2 | 2019 | [14] | ||

| 7 | * | Environmental Science and Pollution Research | Q1 | 2020 | [25] | ||

| 8 | * | Ocean Engineering | Q1 | 2020 | [16] | ||

| 9 | * | IEEE Transactions on Industrial Electronics | Q1 | 2020 | [17] | ||

| 10 | * | IEEE Sensors Journal | Q1 | 2021 | [18] | ||

| 11 | * | Micromachines | Q2 | 2021 | [19] | ||

| 12 | * | Tribology International | Q1 | 2021 | [28] | ||

| 13 | * | Mechanics & Industry | Q3 | 2021 | [29] | ||

| 14 | * | Materials | Q2 | 2022 | [26] | ||

| 15 | * | * | Sensors and Actuators A: Physical | Q1 | 2022 | [37] | |

| 16 | * | Energies | Q1 | 2022 | [20] | ||

| 17 | * | IEEE Transactions on Instrumentation and Measurement | Q1 | 2022 | [21] | ||

| 18 | * | Neural Computing and Applications | Q1 | 2022 | [30] | ||

| 19 | * | Expert Systems with Applications | Q1 | 2022 | [31] | ||

| 20 | * | * | Sensors | Q1 | 2023 | [35] | |

| 21 | * | * | Lubricants | Q2 | 2023 | [38] | |

| 22 | * | IEEE Sensors Journal | Q1 | 2023 | [22] | ||

| 23 | * | Wear | Q1 | 2023 | [32] | ||

| 24 | * | ACS Omega | Q2 | 2023 | [33] | ||

| 25 | * | * | Lubricants | Q2 | 2024 | [39] | |

| 26 | * | Sensors and Actuators A: Physical | Q1 | 2024 | [23] | ||

| 27 | * | SAE International Journal of Fuels and Lubricants | Q3 | 2024 | [34] | ||

| 28 | * | * | IEEE Sensors Journal | Q1 | 2024 | [40] | |

*: Identifies the main idea of each article.

3. Diesel Engine Lubricant Condition Monitoring: Impedance Spectroscopy Applications

The reviewed studies (see Table 2 and Table 3) advance electrical sensing methodologies for lubricant and oil condition monitoring, each addressing distinct aspects through impedance, inductance, and capacitance techniques. For instance, one investigation [15] demonstrates that impedance spectroscopy is a robust tool for evaluating vegetable oils (e.g., sesame and almond) compared to mineral oils in tribological tests, revealing that almond oil exhibits superior lubricity and that impedance measurements can effectively differentiate oil types and degradation states. In a complementary study [14], the precision of impedance spectroscopy in detecting ultralow water content (less than 0.05% vol) in mineral oil is showcased by proposing an in situ system with linear calibration, albeit with limitations imposed by electrode geometry. Equivalent circuit modeling represents the oil’s electrical behavior using resistors (resistance to current), capacitors (energy storage), and inductors (magnetic field interactions). For instance, degraded oil with water contamination may show lower impedance, modeled as a reduced resistance in the circuit [14].

Table 2.

Overview of impedance-based approaches for lubricant condition monitoring.

Table 3.

Methodological overview of impedance-based techniques for lubricant condition monitoring.

Wear debris are microscopic metal particles (e.g., iron, copper) shed from engine components. Their concentration and size in oil indicate mechanical wear severity. Regarding wear debris detection, several investigations [16,17,19,23] introduce innovative sensor designs. A double-wire solenoid coil sensor, as reported in one study [16], detects sub-100 μm particles via inductance-resistance signals; another study [17] employs a square-channel sensor to enhance throughput, while yet another investigation [19] utilizes silicon steel strips in a dual-channel configuration for real-time, multi-parameter detection. Signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) is a measure of signal strength relative to background noise. High SNR ensures reliable data, critical for detecting subtle changes in oil condition. Additionally, one research work [23] describes a Wheatstone bridge with temperature compensation, although its application is limited to ferrous particles. Theoretical contributions include an elliptical model for material-agnostic sizing of non-ferrous particles presented in one study [18] and an eddy current-based impedance model validated experimentally in another investigation [21], though the latter is challenged by the irregular shapes of debris. Eddy currents are circular electric currents induced in conductive materials (e.g., metal debris) by a changing magnetic field. These currents alter the sensor’s impedance, enabling detection and sizing of wear particles.

Moreover, one study [20] optimizes resonance circuits through capacitance tuning, achieving dual sensitivity for both ferrous and non-ferrous particles, albeit requiring separate systems. Another investigation [22] explores an inductive–capacitive dual detection method for mixed particles, but its performance is hindered by low capacitive accuracy. Collectively, these studies highlight trends toward multi-parameter sensing, enhanced environmental robustness (e.g., temperature compensation as observed in [23]), and sensor miniaturization, while also addressing challenges such as debris shape variability, standardization requirements, and interference mitigation.

This work highlights significant advancements in using electrical impedance and inductive sensing for oil condition monitoring, particularly for detecting wear debris and assessing oil degradation. However, several gaps and challenges remain. A primary challenge across studies is the detection of very small wear particles, especially non-ferromagnetic ones. While some research demonstrates the detection of iron particles as small as 20 μm and copper particles as small as 60 μm [16], and even 25 μm iron and 85 μm copper [17], further improvements in sensitivity are needed, particularly for non-ferrous particles. The irregular shape of actual wear debris also poses a challenge, as current models often assume spherical particles, which can affect the accuracy of size and material estimation [18,21]. Signal noise interference is another significant hurdle, as it can mask the detection of small debris, necessitating the development of robust filtering and signal processing techniques [17]. Furthermore, temperature variations significantly impact sensor performance [21], and while some studies propose temperature compensation methods [23], ensuring reliable detection across a wide range of operating temperatures remains crucial. The complexity of fabricating highly sensitive sensors, often requiring external circuits or magnetic materials, presents another practical challenge [16]. For impedance spectroscopy, a limitation is that a single spectrum can correspond to multiple electrical circuits, although this is less of an issue when testing the same substance with a single variable [14]. For multi-parameter detection methods, the need for sufficient standard data for comparison is a challenge for accurate differentiation [22]. Developing in situ, cost-effective, and fast impedance-based systems for specific applications like diesel engine oil monitoring is a future direction [14]. Future directions emphasize the development of hybrid algorithms (e.g., incorporating image recognition as suggested in [22]), improved shielding strategies [16], and broader applicability in harsh environments (e.g., marine systems as noted in [21]). Ultimately, the goal is to transition these promising laboratory techniques to practical, real-world applications for machinery health monitoring and hydraulic equipment, requiring further validation in actual oil samples [20]. Together, these advancements pave the way for real-time, predictive maintenance in industrial and automotive applications. While impedance spectroscopy appeared in detecting contaminants like water and wear debris, dielectric spectroscopy offers distinct advantages in tracking chemical degradation, as explored in the following (Section 4).

4. Diesel Engine Lubricant Condition Monitoring: Dielectric Spectroscopy Applications

Table 4 and Table 5 summarize studies that explore innovative sensor technologies for oil condition monitoring, each employing distinct methodologies and applications. One investigation [24] focuses on terahertz time-domain spectroscopy (THz-TDS) to detect gasoline contamination in engine oil. Terahertz time-domain spectroscopy (THz-TDS) uses terahertz radiation (0.1–10 THz) to probe molecular interactions in oil. This study revealed statistically significant trends (p < 0.0001) in both the refractive index and absorption coefficient, with absorption at 0.5 THz achieving high predictive accuracy (R2 = 0.93–0.998). However, its applicability is limited to SAE 5W-20 oil and contamination levels of 12% or lower. To better understand the information in the tables, root mean square error (RMSE) is a statistical metric quantifying prediction accuracy. The proximity of this criterion to zero is more desirable. Another study [25] introduces a cost-effective capacitive sensor fabricated from recycled aluminum to assess engine oil degradation via permittivity measurements, which were validated against FT-IR spectroscopy. This sensor demonstrated a strong linear correlation (R2 > 0.98) between permittivity and simulated mileage, establishing a critical threshold (ε = 2.73) for oil lifespan. In addition, a separate investigation [26] evaluated a tuning fork sensor for hydraulic oil in machinery. This sensor effectively tracked changes in the dielectric constant and viscosity over a 12-month period, accurately detecting contamination events and correlating well with laboratory analyses (error < 5%). Nonetheless, its exclusion of diesel engine oils limits its broader applicability.

Table 4.

Overview of dielectric-based approaches for oil condition monitoring.

Table 5.

Methodology details: articles focus on dielectric.

A systematic review of these studies (Table 4 and Table 5) highlights the feasibility of dielectric and spectroscopic techniques for oil quality assessment, offering a balance between cost-effectiveness [25], measurement precision [24], and real-time applicability in field conditions [26]. Notable advancements include the integration of recycled materials for sustainable sensor development [25], enhanced discrimination of multiple contaminants through spectroscopic analysis [24], and multi-parameter sensing capabilities for comprehensive oil monitoring [26]. However, ref. [24] achieves high accuracy (R2 = 0.93–0.998) in controlled lab conditions; its applicability is restricted to fresh oils and narrow contamination ranges (0–12%), neglecting real-world factors like oxidation and multi-contaminant interactions. Similarly, ref. [25] demonstrates cost-effective permittivity measurements but relies on simulated degradation, overlooking thermal oxidation effects and requiring field validation for engine integration. Study [26], though effective for hydraulic oils, lacks diesel-specific correlations (e.g., soot, acid formation) and standardized metrics (TBN, FT-IR). Future research should focus on sensor miniaturization, expanding contaminant detection capabilities, and bridging the gap between laboratory-grade precision and the robustness required for industrial applications. It is clear that lubricant monitoring (whether impedance-based, dielectric-based, or other methods) involves complex datasets that require advanced analytical tools. Some of these studies are reported in Section 5.

5. Condition Monitoring of Diesel Engine Lubricant: Soft Computing Applications

The systematic review of soft computing applications in diesel engine oil condition monitoring (see Table 6 and Table 7) highlights the increasing adoption of advanced computational techniques for predictive maintenance and operational optimization. Studies such as [27,31,34] utilize artificial neural networks (MLP, RBF, LSTM) and hybrid models (e.g., LSTM-SVDD, ANFIS) to analyze oil degradation patterns based on datasets obtained from spectral analysis (AES, FTIR), sensor arrays, and real-time monitoring systems. These models effectively predict key indicators, including oil lifespan, wear particle concentrations (Fe, Cr, Na), and viscosity fluctuations, achieving classification accuracies of up to 99% in distinguishing engine health states (normal, caution, critical). Artificial neural networks (ANNs) are computational models inspired by biological neurons, trained to recognize patterns in data. Long short-term memory (LSTM) is a recurrent neural network (RNN) variant effective for analyzing time-series data (e.g., tracking oil degradation trends). Support vector machines (SVMs) are supervised learning models that classify data by finding optimal hyperplanes (e.g., distinguishing healthy vs. degraded oil states). Adaptive neuro-fuzzy inference system (ANFIS) is a hybrid model combining fuzzy logic (handling vague data, e.g., “high” vs. “low” contamination) and neural networks (learning complex patterns). ANFIS improves classification accuracy in noisy environments.

Table 6.

Key contributions of soft computing in engine health monitoring.

Table 7.

Methodological overview of soft computing approaches for oil condition monitoring.

Key advancements in this domain include the identification of cost-efficient diagnostic markers, such as sodium and soot levels, and the integration of fuzzy logic for managing data uncertainties, as demonstrated in [29,32]. Advancements, including real-time capacitive sensors [28] and adaptive algorithms such as the RBF model [33], indicate promising developments in dynamic maintenance scheduling.

The integration of soft computing techniques, such as neural networks and machine learning algorithms, has shown significant potential in advancing diesel engine lubricant condition monitoring. However, several challenges must be addressed to fully leverage these technologies. Key gaps include data uncertainty due to variability in oil samples and limitations in laboratory instrumentation [27]. Sensor noise and the need for optimal sensor design remain critical challenges, as highlighted in studies utilizing capacitive sensor arrays [28]. Future research will focus on enhancing model resilience through multimodal artificial intelligence approaches, incorporating temperature compensation mechanisms, and expanding datasets to improve predictive accuracy. Collectively, these studies underscore the transformative role of soft computing in shifting maintenance strategies from reactive to predictive paradigms, thereby offering substantial cost reductions and improved reliability for industrial applications. The standalone strengths of soft computing, impedance, and dielectric techniques are further amplified when integrated, as demonstrated in hybrid approaches (Section 6).

6. Condition Monitoring of Diesel Engine Lubricant: Multiple Simultaneous Applications

In this section, dielectric/impedance sensors collect real-time electrical data (e.g., permittivity, conductivity). Machine learning models (e.g., ANNs) then process these data to predict oil lifespan, detect contaminants, or classify engine health. A recent study [35] investigated the potential of integrating dielectric and impedance-based parameters to assess the quality of fresh synthetic engine oils, focusing specifically on 5W30-grade oils from various brands. By analyzing electrical properties such as capacitance, impedance magnitude, and quality factor over a frequency range of 100 Hz to 1.2 MHz, the study identified capacitance as a robust, frequency-independent diagnostic marker—with a low variability (6% coefficient of variation)—making it suitable for broad-range applications. Additionally, impedance magnitude and quality factor emerged as critical indicators within specific frequency bands (4000 Hz–0.01 MHz and 2000 Hz–0.01 MHz, respectively), reflecting their sensitivity to changes in oil composition and additive interactions.

The dielectric behavior of the oils, measured under controlled conditions using precision LCR techniques, demonstrated superior selectivity compared to conventional TAN/TBN analyses, which are limited by their dependence on polar degradation byproducts. Moreover, statistical clustering and regression analyses further validated the discriminative power of these electrical parameters, underscoring their potential for real-time sensor development in automotive applications. Despite these promising results, the study also highlighted significant challenges, such as the need to validate findings in degraded oils and to establish explicit correlations between electrical signatures and chemical degradation markers. Future research should address these gaps to facilitate the translation of dielectric and impedance diagnostics into practical, algorithm-driven sensor technologies for dynamic engine environments [35].

Table 8 and Table 9 illustrate the concurrent application of dielectric or impedance measurements integrated with soft computing tools. The reviewed articles emphasize a growing trend toward combining these electrical measurement techniques with advanced computational methods for real-time oil condition monitoring across diverse industrial applications. For example, studies [36,40] employ impedance spectroscopy to correlate oil conductivity with oxidation levels [36] or to classify cross-contaminants such as water and fuel in aviation oil [40], achieving high accuracy (up to 99.8%) with machine learning classifiers like 1-NN and SVM. In parallel, dielectric properties—including permittivity (ε′, ε″) and loss tangent (tan δ)—are extensively investigated in studies [13,37,38,39], where they are linked to contaminant concentrations (e.g., Fe, Pb, Cu) in lubricants. These investigations utilize artificial neural networks (ANNs), radial basis function (RBF) models, and support vector machines (SVMs) to decode the complex relationships between dielectric responses and oil degradation, with RBF models demonstrating superior performance (RMSE < 0.01, R2 > 0.99). Innovations such as temperature-compensated interdigital capacitive sensor arrays [37] and thick-film potentiometric sensors [36] address challenges including thermal drift and cross-sensitivity, while soft computing techniques enable multi-property prediction (e.g., water, soot, base levels) and fault diagnosis.

Table 8.

Overview of combined dielectric/impedance and soft computing approaches for oil condition monitoring.

Table 9.

Overview of combined dielectric/impedance and soft computing methodologies.

Finally, based on the studies presented in Table 8 and Table 9, despite advancements, key limitations persist, including temperature sensitivity [36,37], limited generalizability across oil types [35], and small sample sizes [39]. Future research should prioritize field validation of sensors in degraded oils [35], integration of fuzzy logic to handle measurement uncertainties [39], and development of hybrid models (e.g., RNNs) for temporal analysis [40]. Disposable sensor technologies could enhance industrial adoption, while collaborative efforts to expand datasets [39] and optimize hyperparameters [38] will strengthen predictive accuracy. Collectively, these innovations underscore the transition toward AI-driven, multi-modal systems capable of real-time diagnostics, reducing downtime, and advancing predictive maintenance paradigms. These approaches offer scalable solutions for industries ranging from aviation to heavy machinery, although further field validation and sensor integration remain critical for broader industrial adoption.

7. Conclusions and Outlook

Recent advancements in impedance, dielectric, and soft computing techniques have significantly enhanced the capability to monitor lubricant conditions in diesel engines, enabling a shift from reactive to predictive maintenance strategies. Our comprehensive review of 28 studies highlights a range of innovative approaches—including thick-film potentiometric sensors, impedance spectroscopy, and machine learning models—that demonstrate strong correlations between oil properties, wear debris, and engine health indicators. These findings underscore the potential of data-driven sensor designs to detect oil degradation early, thereby enabling timely maintenance interventions.

The application of soft computing methods, such as artificial neural networks and support vector machines, has proven effective in accurately forecasting lubricant properties and classifying engine health states based on key markers. However, challenges remain, including the inherent complexity of oil chemistry, the need for further validation under diverse operating conditions, and the difficulty of standardizing sensors and data interpretation protocols for seamless integration into current maintenance practices. On this basis, future research should prioritize the following three key directions:

- Enhanced Sensor Design: Miniaturized, cost-effective sensors with improved shielding and multi-modal detection capabilities (e.g., inductive–capacitive hybrids) are needed to address sensitivity and environmental robustness. Integrating image recognition or advanced signal processing could mitigate challenges posed by irregular debris shapes and noise.

- AI-Driven Multi-Modal Systems: Combining impedance, dielectric, and spectroscopic data with adaptive AI models (e.g., fuzzy logic, recurrent neural networks) will improve predictive accuracy and handle measurement uncertainties. Collaborative efforts to expand datasets and optimize hyperparameters are essential for generalizable solutions.

- Field Validation and Standardization: Translating laboratory success to industrial applications requires rigorous validation in real-world environments, particularly for degraded oils and multi-contaminant scenarios. Establishing standardized metrics for electrical properties and degradation thresholds will bridge the gap between research and practical implementation.

These improvements are expected to reduce operational costs by extending oil change intervals and minimizing unscheduled downtime, while also promoting environmentally friendly practices through improved lubricant management. As these technologies continue to evolve, they will play a critical role in advancing predictive maintenance and enhancing overall engine performance in automotive, marine, and aerospace sectors. The transition to predictive maintenance paradigms promises not only economic benefits but also environmental sustainability through optimized lubricant management.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.-R.P.; methodology, A.R. and M.-R.P.; software, A.R. and M.-R.P.; validation, A.R. and M.H.A.-F.; formal analysis, A.R.; investigation, M.-R.P.; resources, M.-R.P.; data curation, A.R.; writing—original draft preparation, M.-R.P.; writing—review and editing, A.R. and M.H.A.-F.; visualization, M.-R.P.; supervision, A.R.; project administration, A.R. and M.H.A.-F.; funding acquisition, A.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

We express our deepest gratitude to Ferdowsi University of Mashhad for supporting our project (Grant number 59252). Their generous assistance was vital for the feasibility of our research. Finally, we extend our sincere gratitude to all contributors and colleagues who shared their expertise and insights. Your valuable input was instrumental in achieving our research goals.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors claim that there is no conflict of interest.

References

- Di Battista, D.; Fatigati, F.; Di Bartolomeo, M.; Vittorini, D.; Cipollone, R. Thermal management opportunity on lubricant oil to reduce fuel consumption and emissions of a light-duty diesel engine. E3S Web Conf. 2021, 312, 07023. [Google Scholar]

- Siraskar, G.; Wakchaure, V.; Jahagirdar, R.; Tiwari, H. Cottonseed trimethylolpropane (TMP) ester as lubricant and performance characteristics for diesel engine. Int. J. Eng. Adv. Technol. 2020, 9, 761–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tornehed, P.; Olofsson, U. Lubricant ash particles in diesel engine exhaust. Literature review and modelling study. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part D J. Automob. Eng. 2011, 225, 1055–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalid, Z.; Ali, M. Modification and comprehensive review on vegetable oil as green lubricants (bio-lubricants). Int. J. Res. Publ. 2020, 61, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Will, F.; Boretti, A. A new method to warm up lubricating oil to improve the fuel efficiency during cold start. SAE Int. J. Engines 2011, 4, 175–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zare, A.; Bodisco, T.A.; Jafari, M.; Verma, P.; Yang, L.; Babaie, M.; Rahman, M.; Banks, A.; Ristovski, Z.D.; Brown, R.J. Cold-start NOx emissions: Diesel and waste lubricating oil as a fuel additive. Fuel 2021, 286, 119430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iswantoro, A.; Cahyono, B.; Ruyan, C. The effect of using biodiesel B50 from palm oil on lubricant oil degradation and wear on diesel engine components. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2023, 1166, 012015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamil, M.K.; Akhtar, M.; Farooq, M.; Abbas, M.M.; Saad; Khuzaima, M.; Ahmad, K.; Kalam, M.A.; Abdelrahman, A. Analysis of the impact of propanol-gasoline blends on lubricant oil degradation and spark-ignition engine characteristics. Energies 2022, 15, 5757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolak, A.; Molenda, J.; Fijorek, K.; Łankiewicz, B. Prediction of the total base number (TBN) of engine oil by means of FTIR spectroscopy. Energies 2022, 15, 2809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sejkorová, M. Application of FTIR spectrometry using multivariate analysis for prediction fuel in engine oil. Acta Univ. Agric. Silvic. Mendel. Brun. 2017, 65, 933–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duchowski, J.K.; Mannebach, H. A novel approach to predictive maintenance: A portable, multi-component MEMS sensor for on-line monitoring of fluid condition in hydraulic and lubricating systems. Tribol. Trans. 2006, 49, 545–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allgood, G.O.; Van Hoy, B.W.; Ayers, C.W. Detection of Gear Wear on the 757/767 Internal Drive Generator Using Higher Order Spectral Analysis and Wavelets; Oak Ridge National Laboratory (ORNL): Oak Ridge, TN, USA, 1997.

- Altıntaş, O.; Aksoy, M.; Ünal, E.; Akgöl, O.; Karaaslan, M. Artificial neural network approach for locomotive maintenance by monitoring dielectric properties of engine lubricant. Measurement 2019, 145, 678–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macioszek, Ł.; Włodarczak, S.; Rybski, R. Mineral oil moisture measurement with the use of impedance spectroscopy. IET Sci. Meas. Technol. 2019, 13, 1158–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado, E.; Aperador, W.; Hernández, A. Impedance spectroscopy as a tool for the diagnosis of the state of vegetable oils used as lubricants. Int. J. Electrochem. Sci. 2015, 10, 8190–8199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Shi, H.; Zhang, H.; Li, G.; Shen, Y.; Zeng, N. High-sensitivity distinguishing and detection method for wear debris in oil of marine machinery. Ocean Eng. 2020, 215, 107452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, H.; Zhang, H.; Ma, L.; Rogers, F.; Zhao, X.; Zeng, L. An impedance debris sensor based on a high-gradient magnetic field for high sensitivity and high throughput. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2020, 68, 5376–5384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Wang, F.; Zhao, M.; Wang, B.; Yang, C. A method for measurement of nonferrous particles sizes in lubricant oil independent of materials using inductive sensor. IEEE Sens. J. 2021, 21, 17723–17731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Shi, H.; Li, W.; Ma, L.; Zhao, X.; Xu, Z.; Wang, C.; Xie, Y.; Zhang, Y. A novel impedance micro-sensor for metal debris monitoring of hydraulic oil. Micromachines 2021, 12, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Wu, S.; Raihan, M.K.; Zhu, D.; Yu, K.; Wang, F.; Pan, X. The optimization of parallel resonance circuit for wear debris detection by adjusting Capacitance. Energies 2022, 15, 7318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Ma, L.; Shi, H.; Xie, Y.; Wang, C. A method for estimating the composition and size of wear debris in lubricating oil based on the joint observation of inductance and resistance signals: Theoretical modeling and experimental verification. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2022, 71, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Wang, S.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, H.; Shi, H. Dual Inductive–Capacitive Detection Cell: A Promising Tool for Distinguishing Mixed Metal Particles. IEEE Sens. J. 2023, 23, 21163–21171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, C.; Wang, S.; Zheng, Y.; Wang, C.; Xie, Y.; Zhang, H. Oil wear debris sensor with temperature compensation. Sens. Actuators A Phys. 2024, 376, 115595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdul-Munaim, A.M.; Aller, M.M.; Preu, S.; Watson, D.G. Discriminating gasoline fuel contamination in engine oil by terahertz time-domain spectroscopy. Tribol. Int. 2018, 119, 123–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heredia-Cancino, J.; Carrillo-Torres, R.; Munguía-Aguilar, H.; Álvarez-Ramos, M. An innovative method to reduce oil waste using a sensor made of recycled material to evaluate engine oil life in automotive workshops. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 28104–28112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, H.-G.; Kim, J.-K.; Na, S.-J.; Kim, M.-S.; Hong, S.-H. Application of condition monitoring for hydraulic oil using tuning fork sensor: A study case on hydraulic system of earth moving machinery. Materials 2022, 15, 7657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gajewski, J.; Vališ, D. The determination of combustion engine condition and reliability using oil analysis by MLP and RBF neural networks. Tribol. Int. 2017, 115, 557–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, D.; Urban, A.; Zhu, X.; Zhe, J. Oil property sensing array based on a general regression neural network. Tribol. Int. 2021, 164, 107221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.; Lu, Y.; Luo, H.; Li, J.; Hou, Y.; Zhang, Y. Wear assessment model for cylinder liner of internal combustion engine under fuzzy uncertainty. Mech. Ind. 2021, 22, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pourramezan, M.-R.; Rohani, A.; Keramat Siavash, N.; Zarein, M. Evaluation of lubricant condition and engine health based on soft computing methods. Neural Comput. Appl. 2022, 34, 5465–5477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahimi, M.; Pourramezan, M.-R.; Rohani, A. Modeling and classifying the in-operando effects of wear and metal contaminations of lubricating oil on diesel engine: A machine learning approach. Expert Syst. Appl. 2022, 203, 117494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Gao, H.; Yang, K.; Zhou, F.; Shi, X. Abnormal identification of oil monitoring based on LSTM and SVDD. Wear 2023, 526, 204793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pourramezan, M.-R.; Rohani, A.; Abbaspour-Fard, M.H. Comparative Analysis of Soft Computing Models for Predicting Viscosity in Diesel Engine Lubricants: An Alternative Approach to Condition Monitoring. ACS Omega 2023, 9, 1398–1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pourramezan, M.-R.; Rohani, A. Improved Monitoring and Classification of Engine Oil Condition through Two Machine Learning Techniques. SAE Int. J. Fuels Lubr. 2024, 18, 107–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolak, A.; Żywica, R.; Molenda, J.; Banach, J.K. Electrical parameters as diagnostics of fresh engine oil condition—Correlation with test voltage frequency. Sensors 2023, 23, 3981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soleimani, M.; Sophocleous, M.; Wang, L.; Atkinson, J.; Hosier, I.L.; Vaughan, A.S.; Taylor, R.I.; Wood, R.J. Base oil oxidation detection using novel chemical sensors and impedance spectroscopy measurements. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2014, 199, 247–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urban, A.; Zhe, J. A microsensor array for diesel engine lubricant monitoring using deep learning with stochastic global optimization. Sens. Actuators A Phys. 2022, 343, 113671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pourramezan, M.-R.; Rohani, A.; Abbaspour-Fard, M.H. Unlocking the Potential of Soft Computing for Predicting Lubricant Elemental Spectroscopy. Lubricants 2023, 11, 382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pourramezan, M.-R.; Rohani, A.; Abbaspour-Fard, M.H. Machine Learning-Based Predictions of Metal and Non-Metal Elements in Engine Oil Using Electrical Properties. Lubricants 2024, 12, 411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Pascali, C.; Bellisario, D.; Signore, M.A.; Sciurti, E.; Radogna, A.V.; Francioso, L. A Rapid Classification of Cross-Contaminations in Aviation Oil Using Impedance-Driven Supervised Machine Learning. IEEE Sens. J. 2024, 24, 38209–38221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazakis, I.; Raptodimos, Y.; Varelas, T. Predicting ship machinery system condition through analytical reliability tools and artificial neural networks. Ocean Eng. 2018, 152, 404–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craft, J.W. Development of Interdigitated Electrode Sensors for Monitoring the Dielectric Properties of Lubricant Oils. Master’s Thesis, Auburn University, Auburn, Alabama, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Raadnui, S.; Kleesuwan, S. Low-cost condition monitoring sensor for used oil analysis. Wear 2005, 259, 1502–1506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Yan, E. Application of Information Fusion Technology in Lubricating Oil Quality Monitoring. In Proceedings of the 2022 4th International Conference on Robotics, Intelligent Control and Artificial Intelligence, Dongguan, China, 16–18 December 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Schmitigal, J.; Moyer, S. Evaluation of Sensors for On-Board Diesel Oil Condition Monitoring of US Army Ground Equipment; 0148-7191; SAE Technical Paper; SAE: Warrendale, PA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Tanwar, M.; Raghavan, N. Lubricating oil remaining useful life prediction using multi-output Gaussian process regression. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 128897–128907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molęda, M.; Małysiak-Mrozek, B.; Ding, W.; Sunderam, V.; Mrozek, D. From corrective to predictive maintenance—A review of maintenance approaches for the power industry. Sensors 2023, 23, 5970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vališ, D.; Gajewski, J.; Žák, L. Potential for using the ANN-FIS meta-model approach to assess levels of particulate contamination in oil used in mechanical systems. Tribol. Int. 2019, 135, 324–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upadhyay, R. Microscopic technique to determine various wear modes of used engine oil. J. Microsc. Ultrastruct. 2013, 1, 111–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, R.; Gao, R.X. Complexity as a measure for machine health evaluation. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2004, 53, 1327–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bongfa, B.; Syahrullail, S.; Hamid, M.A.; Samin, P.; Atuci, B.; Ajibili, H. Maximizing the life of lubricating oils for resources and environmental sustainability through quality monitoring in service. Indian J. Sci. Technol. 2016, 9, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, W.; Chen, J.; Zhang, C. Friction of metal-matrix self-lubricating composites: Relationships among lubricant content, lubricating film coverage, and friction coefficient. Friction 2020, 8, 517–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).